Abstract

The aim of this study was to analyze urban sensory gardens containing aromatic herbs in terms of the plants used in them. The analysis considered the impact of climate change, particularly of higher temperatures, which may affect the character of contemporary urban gardens. The study was planned primarily in the context of the gardens’ therapeutic significance to their users. An important part of the work was to analyze how particular aromatic plants are perceived and received by the inhabitants, using the example of one of Poland's largest cities, Kraków, to assess whether they can have an impact on the inhabitants’ positive memories and thus improve their well-being. Initially, the plant composition of gardens located in Poland that feature aromatic herbs was analyzed. This was followed by a survey and an analysis of therapeutic gardens using the Trojanowska method as modified by Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz et al. The plant composition analysis of sensory gardens featuring herbs demonstrated that vulnerable plants in the Central European climate are being introduced to urban sensory gardens. In terms of major aromatic plants, it was found that almost every respondent reported the existence of scents that had some form of essential significance associated with personal memories. Considering the important sensory impact of water elements in therapeutic gardens, as well as problems related to the acquisition of drinking water or water used in agriculture or horticulture, the paper also addresses this topic. It was found that the city dwellers who filled in the questionnaire strongly preferred the introduction of more ecological solutions in the gardens related to water use—to collect and use rainwater, e.g., for watering, instead of piped water.

1. Introduction

1.1. Sensory Gardens with Herbs as Therapeutic Places in the Urban Tissue

Publicly accessible sensory gardens are a part of urban public greenery [1]. Similarly other well-designed green areas in cities, they can act primarily as restorative gardens if they guide the user to achieving an internal bodily balance (homeostasis) [2], which results in an improvement in one’s emotional and physical fitness, even if by merely reducing stress. A sensory garden is a special type of garden, listed among therapeutic gardens, and as such has significant use in therapy [3]. Such gardens should be designed so that humans are able to experience them from up close [4]. Although the primary function of a sensory garden is to affect its users’ senses, it is defined in various ways in the literature, with listings of commonly used definitions provided by Husein [5], Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz et al. [6], Wajchman-Świtalska et al. [7]. To us, the sense of a publicly accessible urban sensory garden is expressed most precisely in the definition of the British Sensory Trust, which states that a garden is: “a self-contained area that concentrates a wide range of sensory experiences […], such an area, if designed well, provides a valuable resource for a wide range of uses, from education to recreation” [8]. In an urban setting, sensory gardens can be established for various types of users and are thus intended for different forms of activity [6].

Sensory gardens should be designed with special care so that they can fulfil their assigned therapeutic tasks [3,4,9,10]. Plants are a crucial component of these gardens, with aromatic herbs being particularly of value [3]. Herbs are defined as “any plant with leaves, seeds or flowers used for flavoring, food, medicine, fragrance production, etc.” [11]. In ages past, herbs also held spiritual significance—they had a religious, ritual, or symbolic value [12]. This highlights their important and wide ranging effects on people. Many herbs that appeared in Central and Eastern Europe by the Middle Ages and arrived through convents and monastic gardens, were originally prevalent in warmer areas of Europe and Asia [12,13,14]. They made their way from monastic gardens to lay ones, and to the collective conscious as part of medicinal preparations, seasoning for meals, or in various types of ceremonies, which contributed to their widespread recognition [12]. Accounting for the origins of many such plants, it was not always possible to cultivate them in the soil in the climate of Poland. However, the currently observed climate change could visibly alter the appearance and extend the significance of gardens that feature herbs.

At present, herbs are desirable element of contemporary gardens and play a crucial role in selected therapeutic programs [3]. This is due to the influence of the scent of aromatic herbs on the sense of smell that does not limit itself to the flowers of such plants, as it also includes their vegetative elements, which extends their application scope. A study by Zajadacz et al. [15] noted that scents play a greater role in the spatial orientation of blind people in sensory gardens than they do outside of them. Arslan et al. [16] also discussed the general matters of the application of aromatic herbs in therapeutic gardens. Aromas, including herbal ones, are also crucial for another reason, as the key significance of scents in stimulating memory-dependent bodily functions was observed, allowing us to “transfer the past into the present” [17,18] and to build certain new relations based on previous experiences. This is used in practice in, among other places, sensory gardens near special education facilities—in children’s therapy, where a familiar plant scent, especially one associated with home and family, contributes to better performance in spatial orientation tasks and building self-confidence and autonomy [4].

1.2. Climate Change, Greenery, and Human Health

Global climate change results in local phenomena that affect specific regions and countries [19]. Rising temperatures affect people who live in cities in an especially negative way, with high summer temperatures having a profoundly negative impact. This problem is further compounded by the so-called urban heat island effect that occurs in urbanized areas [20]. Heat waves, describing long periods of elevated temperature, are another compounding effect of climate change, and were found to have a particularly detrimental effect on human health and wellbeing, especially in seniors [21,22]. Such phenomena have been observed in Kraków, one of Poland’s largest cities, among others [23].

The presence of urban greenery can alleviate the negative consequences of high temperatures, for instance by plant transpiration or through the visibly lower heat accumulation of plant-occupied surfaces in comparison to paved surfaces or open areas [24,25]. A green environment can also positively affect the health and wellbeing of urban residents, even via its passive observation [26]. Numerous studies found that humans desire contact with nature and display a preference for a green setting instead of a typically urbanized one when choosing a place to regenerate after mental exhaustion. Being present in a greenery-rich environment was found to facilitate psychological renewal [27,28]. As opposed to stress and the rapid pace of urban life, a garden offers a slow rhythm and an absence of disruptiveness via its changing plants, which is noted by its users, and brings calmness and peace [29]. Studies performed in Great Britain found that, in a big-city setting, visiting urban green areas led to different types of wellbeing benefits than strolling outside the city. It was found that it reduces anxiety [30]. The positive impact of green spaces on various health-related human problems was investigated in numerous studies, which were collected and briefly discussed by Chiabai et al. [31]. Papers that describe its impact on the mental wellbeing of adults were summarized by Houlden et al. [32]. Urban greenery positively affects the residents of urban areas and can remediate the negative consequences of climate change, yet it is also impacted by such consequences. Positive phenomena in this respect include an extension of the vegetation period both in Poland and other European countries [33], which contributes to gardens appearing attractive for longer periods, and in the case of therapeutic gardens, extends the season during which they can affect their users. In the light of climate change, a simulated temperature increase of 1 °C relative to the final three decades of the twentieth century was performed and showed a significant decrease in the temperate cool region’s reach, and an increase in the area of the temperate warm region, along with the appearance of a warm region [19], which can contribute to changes in the composition of species introduced into green areas in individual territories, and can lead to the spread of thermophilic flora, especially in cities [34,35]. The estimated temperature increase is expected to lead to an increased water deficit [21], which is a climate-change consequence that negatively affects plants and gardens.

1.3. Goal of the Study

The purpose of the survey study among the residents of a large city was to investigate the way respondents perceived the smells of various herbs and to reach deeper to determine whether specific herbs had positive memory-dependent significance to respondents. The practical applications of the answers to these questions may aid in better understanding the restorative and therapeutic impact of sensory gardens featuring herbs on city residents. Therefore, the study also featured an analysis of the therapeutic potential of existing Polish gardens with sensory features which primarily targeted the sense of smell. The outcome of this analysis was to indicate how their therapeutic scope can be extended. Problems associated with climate change were also investigated. Our work also takes into account the problems associated with climate change, particularly that of rising temperatures in cities, which may affect existing urban gardens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Sites

The study investigated six publicly accessible urban gardens located in Poland (Table 1). The gardens were selected due to aromatic herbs being their major component, in addition to being intentionally designed as fragrant gardens. The selected gardens were relatively well-known domestically, as they had either already appeared in studies on therapeutic gardens, were featured in garden trails, or were located in areas frequently visited by people from various areas of Poland and abroad. Some of the gardens directly referenced the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, periods when the sense of smell was held in high regard. All of the analyzed gardens were contemporary, although some of them were located in areas previously occupied by historical gardens.

Table 1.

Overview of the gardens under study.

Publicly accessible gardens are defined as gardens that are accessible to all visitors and can be visited either during specific hours or are always open. The following urban gardens with sensory features and located in Poland were selected for the study:

- Frombork: Herbal garden near a historical medieval hospital building belonging to the Holy Spirit Hospital—currently a museum;

- Kamień Śląski: The S. Kneipp herbal garden—near a Kneipp Institute therapeutic facility [10];

- Kraków: The herbal garden of the Czapski Pavilion—a museum;

- Sandomierz: The Garden of Marcin of Urzędów—a garden referencing a medicinal Renaissance garden [36];

- Kraków: Zapachowo fragrance garden and sensory path at the S. Lem Science Garden [7,37];

- Solec Zdrój: Educational Path—Aromatherapeutic Avenue—a fragrant garden built by the Solec Zdrój Municipality.

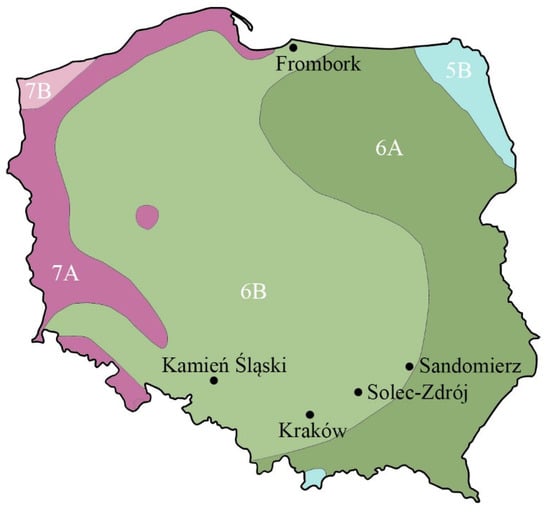

Poland is in Central Europe, in a temperate climate zone. Poland is noted to have a transitional climate influenced by Western Europe’s marine climate and Eastern Europe’s continental climate. Additionally, due to the influx of a diverse range of air masses, the Polish climate is characterized by a degree of variance. Poland’s territory can be divided into subregions that differ in temperature, the course of the seasons and amount of rainfall that occurs [19,38]. Temperatures, especially temperature extremes, and particularly those in winter, have a significant impact on the plant types cultivated in gardens. Therefore, so-called frost-resistance zones are delineated, with three such zones in Poland, which are taken into consideration during species-composition formulation for gardens. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

This illustration shows a map of Poland with the location of the herb gardens analyzed in this work. Colors and numbers with letters: 5B, 6A, 6B, 7A, 7B indicate frost zones of plants in Poland.

2.2. Methods

At the start of the study, the selected plant material present in the gardens was analyzed, with a focus on species that provide olfactory stimulation. This was achieved using the available species lists and with surveys performed in all the gardens. A list of aromatic herbs used in the gardens was compiled. In addition, the species that were listed in the literature as struggling to survive winters in the Polish climate or unable to survive them while planted in the soil were enumerated. The frequency of using temperature-sensitive plants in the sensory gardens under study was investigated, as well as the ways the most vulnerable plants are able to survive winter in urban conditions in the current Polish climate.

A survey study was used to investigate how the individual herb fragrances present in such gardens were perceived by the residents of a large city—Kraków. The survey sample consisted of 73 people. The sample group was small and therefore cannot be considered representative, but in our opinion it is sufficient for the preliminary study described. In future research, the target group of respondents will be expanded.

Seeing as sensory gardens are often dedicated to specific groups of city-dwelling users [6] with distinctive needs, the respondents were divided into the following three age groups: group A—young people between 18 and 29 years of age, typically students or engaging in first-time employment; group B—people between 30 and 59 years of age, either employed or active in their respective families, group C—seniors aged 60 and above. The respondents were asked six questions, with three concerning aromatic herbs and the remaining three concerning water in herbal gardens. Those aromatic herbs that appeared the most often in Polish gardens with sensory features associated with the sense of smell as well as species sensitive to low temperatures were selected for this study. Concerning water in herbal gardens, the questions in the survey asked whether respondents found it to be significant in herbal gardens, its significance in those gardens and whether the respondents found where said water was sourced from to be significant.

In the first stage, an analysis of the gardens’ therapeutic potential was performed using the Trojanowska method [39,40], as adapted to gardens with sensory features by Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz et al. [6]. The method is based on an assessment of the gardens’ attributes, whereby an attribute is understood as “a feature of space or the presence of features” [39]. In this method, as the number of attributes increases, so does an area’s therapeutic potential. It is a method that has, upon suitable adaptation, been successfully used to analyze therapeutic areas of various sizes, such as sensory gardens [4], parks [39,40] and large areas such as a seacoast fragment with natural and cultural value [41].

The attributes were grouped into design stages as follows: (1) functional program, (2) functional–spatial structure, (3) the design of internal spaces and architectural form, (4) placemaking, (5) accounting for sustainability requirements [39]. The last group of attributes, namely sustainability requirements, is essential for two reasons. First, it brings to mind the problems that appear in green areas, including in response to climate change, and the proper management of natural resources by humans. The second crucial aspect concerns the associated properties of a sensory garden that determine its perception by users.

3. Results

3.1. Aromatic Herbs in the Gardens with Sensory Features

Table 2 shows the species used in the gardens under study and how often they appeared. The listing includes plants from warmer areas of the world, which are vulnerable during winter, and thus are interesting from a climate-change standpoint. Furthermore, two species of aromatic herbs that appeared less often in these areas while being well-known in Poland were of note (Levisticum officinale W.D.J. Koch and Melissa officinalis L.). The nine species identified were later featured in the survey intended for later stages of the study.

Table 2.

Presence of aromatic herbs in the gardens under study. The plants typically used in these gardens, as well as more vulnerable plants originating from warmer areas of the world. V is a stamp which should be read as “yes”, in this case a confirmation that the plant is in the assigned garden.

True lavender appeared in all the gardens, in addition to Salvia officinalis L. or other species of salvia. Both Nepeta × Faasenii Bergmans ex Stearn and Origanum vulgare L. were not as prevalent, but still common, as they were present in five cases. Mint, Mentha x piperita L., was also used relatively frequently, but mostly peppermint, in addition to Hyssopus officinalis L., which was noted in four of the six analyzed gardens. Melissa officinalis L., lemon balm, as well as a number of herbs used as dried seasoning in cooking, were rarer, present in only a half of the gardens, which is why they were not included in the survey. Our study showed that other aromatic herbs were only present in gardens in singular cases, and as such cannot be said to be popular as plants used in publicly accessible urban herbal and fragrant gardens.

The group of aromatic herbs that were previously considered not to winter in the soil or only partially winter this way includes as many as four species found in the gardens under study. Interestingly, plants from the following three genera: Lavandula, Salvia and Hyssopus, are very popular in these gardens and were found in either all or nearly all the gardens. Even rosemary, Rosmarinus officinalis, which is highly sensitive to low temperatures and was seen as a plant that does not winter in Poland, was present in two gardens. Therefore, it can be stated that sensitive plants were boldly introduced into contemporary urban gardens.

3.2. Kraków’s Residents’ Associations with the Smell of Herbs

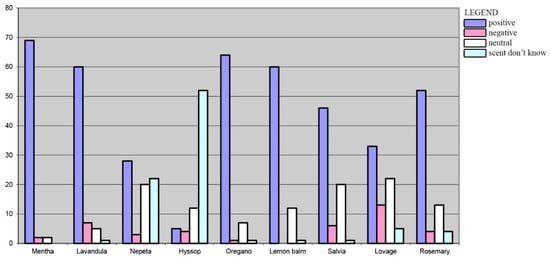

The results of the survey performed as a part of this study showed that the vast majority of aromatic herbs and their smells were positively perceived by the respondents—residents of Kraków (Figure 2). Although, the smell of catnip Nepeta sp. and lovage Levisticum sp. were indicated as liked by a smaller group. A number of respondents identified the smell of lovage Levisticum sp. as one they did not like, with a similar sentiment expressed for lavender Lavandula sp. and salvia Salvia sp. An altogether different result in comparison to the previous herbs was returned for the smell of hyssop Hyssopus sp., with the majority of respondents reporting this smell to be either completely unknown to them or that it was neither pleasant nor unpleasant. This can mean that although it is a generally well-known plant, as a plant mentioned in the Bible, it was not known to the respondents from direct experience, due to its infrequent use in private or public gardens in Poland.

Figure 2.

Results showing the perception of the smell of each herb as reported by respondents.

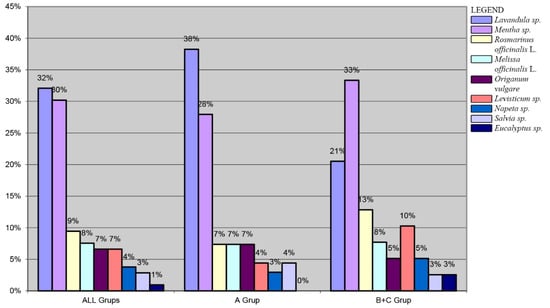

Almost all of the respondents reported having a favorite aromatic plant, whose smell they saw as particularly pleasant and bringing to mind positive associations. The most important plants to which the respondents ascribed such significance were herbs such as lavender Lavandula sp. and mint Mentha sp. (Figure 3). There was a slight difference according to the respondents’ age. Among young persons between 18 and 29 years of age, the highest number of respondents pointed to lavender Lavandula sp., followed by mint Mentha sp., which was in turn followed by lemon balm Melissa sp., oregano Origanum sp., and rosemary Rosmarinus sp., which were picked much less often. Among older persons, aged 30 and above, the greatest number of respondents listed their most liked and positively associated herbs as mint Mentha sp., followed by lavender Lavandula sp., rosemary Rosmarinus sp., and lovage Levisticum sp., respectively.

Figure 3.

Results presenting associations with a smell that held particular significance to respondents divided into two age groups—young people up to 29 years of age (group A) and aged 30 and above (groups B and C).

The respondents reported that the smells in question brought clearly positive associations, primarily linked with home and family, often simultaneously with childhood and youth, the vacation season, as well as memories of exceptional travels, mostly during summer (Table 3). In every age group, positively perceived smells carried at least one of the above meanings. However, a difference in the percentage shares in their ascription to each meaning was observed. In the group with the youngest respondents (group A), the greatest significance was found for associating the smell of one’s favorite herbs with home and family (70%), the middle-aged group saw smells associated with home, travel, and summer as equally important, while seniors reported positive associations mostly with home and family (60%).

Table 3.

Specific associations with past events listed by respondents as tied with preferred aromatic herbs.

In terms of the specific significances that respondents ascribed to the smell of individual herbs (Table 4), most respondents across all age groups reported that it was the smell that was the most important, yet a large group of respondents tied it with the addition of a given herb to a specific beverage or meal. The significance of the application of a given herb as a home remedy and the association of its smell with a preparation intended to aid in minor health disorders was reported to be smaller, yet still substantial.

Table 4.

The significance of favorite herbs and their smell.

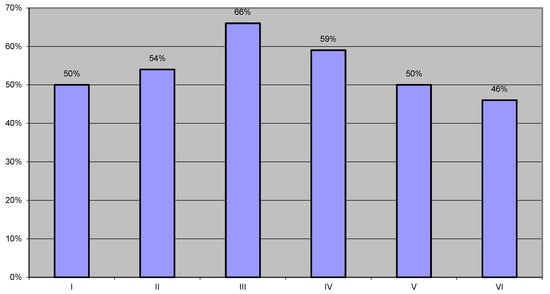

3.3. Therapeutic Potential of Gardens Featuring Aromatic Herbs

The results of the analysis of the therapeutic potential of the gardens under study are presented in Table 5 and Table 6 and are graphically illustrated in Figure 4. Most gardens with aromatic herbs were rated to have a potential of around 50%, with the range being 46–59%. Only one garden, near the J. Czapski pavilion, was found to have a slightly higher therapeutic potential of 66%.

Table 5.

Analysis of the therapeutic properties of herbal gardens with sensory features, part 1—functional program.

Table 6.

Analysis of the therapeutic properties of herbal gardens with sensory features, part 2—other attributes.

Figure 4.

Overall results of the therapeutic potential analysis of the gardens under study.

3.4. Water in Sensory Gardens Featuring Herbs

Due to global warming and the existence of the urban heat island effect, along with the occurrence of various associated problems concerning urban greenery and their impact on human health and wellbeing, we investigated the role of water in city gardens. This is why the survey performed as part of this study included questions on whether water and its sound can have a positive impact on the perception of gardens that include herbs and the significance it could have. Most respondents reported that it can have a positive impact to humans and city-dwelling animals—see Table 7.

Table 7.

Problems associated with water in sensory gardens—survey responses.

In the light of the problems caused by water deficits and those of cities, the respondents were asked whether they found the source of water used in a garden to be significant. The majority of the respondents replied that they found it significant and that they believed that rainwater and stormwater should be the main source of water used in gardens.

4. Discussion

In gardens with sensory features, especially those that feature aromatic herbs, the impact of climate change, and especially global warming, has already become somewhat noticeable. Plants that were rarely seen in urban spaces in the twentieth century due to their possible freezing in the Polish climate [42] are currently more often encountered in cities. One such case is true lavender Lavandula angustifolia Mill., which in Poland was first introduced into private gardens, and in recent years it has increasingly been planted in public gardens, near parking lots and on church grounds. It was observed that this species was present in all of the herbal gardens investigated in this study. Rosemary Rosmarinus officinalis L. is another such example. It was seen as a pot plant in the Polish climate, originally present on the edges of the Mediterranean Sea, and is typically cultivated in European countries with mild winters [43]. This species has only recently been introduced in Polish public spaces, on a much smaller scale than lavender, as it is a more sensitive species. Rosemary was introduced into the garden near the J. Czapski Museum, which has sensory garden features. In Kraków’s city center, the urban heat island effect has been observed, while along the area’s edges, temperatures are not always higher than in the surrounding rural areas. This depends on a range of factors [23]. The aforementioned area near the Museum is located in the heart of the city, where temperatures are the highest. In terms of aromatic plants, high temperatures make the fragrances produced by them more intense. The area is also shielded from cross-ventilation by buildings, while from the north it is fenced by an insolated garden wall that is warmed by the sun. These are factors that contribute to the presence of favorable conditions for sensitive plants, including in winter. Rosemary is able to survive winter in such a setting without cold protection, which was observed for several consecutive years. As an evergreen plant, it greatly enlivens garden spaces with its vivid green color. Shanahan et al. argued that the visual features of a green environment and the biophysical parameters of greenery, stemming from the features of plant structure and physiological activity, both play a part in affecting human health [25].

Expanding the set of plants used in sensory gardens to include species that were previously seen as vulnerable, and which are familiar to and liked by city residents can enhance health benefits. A study by Bengtsson and Grahn [9] demonstrated that a significant role in rehabilitation and convalescence is played by high species diversity in therapeutic gardens, especially during the later stages of the process. These observations can also be applied to city parks, which is why apart from plants introduced by people, it is important to note factors that can contribute to the diversity of domestic species in park cover [44,45]. Many domestic plants or aromatic herbs are attractive to insects and observing animals in therapeutic gardens enhances the scope of sensory stimuli [46] and supports therapy [47]. A study by Cooper Marcus et al. [48] also showed just how important the inclusion of animals is in improving wellbeing. It presented how observing wildlife, including insects and birds, was identified as a major activity among hospital gardens.

The findings indicate that most city residents can be said to positively perceive the smells of various herbs. In addition, regardless of age, many residents expressed that they preferred herbal smells and reported that such smells elicited personal and highly positive associations. In our study, the respondents’ favorite aromas were typically associated with the home, childhood, as well as the vacation season, representing a time of rest and relaxation. Winterbottom and Wagenfeld argued that bringing to mind pleasant past experiences can be significant to people who have had to leave their place of residence for various reasons such as illness, homelessness, as well as for people who find themselves in a completely alien environment [3]. The period of childhood, linked with nature or specific plants, remains strongly embedded in a person’s memory, as observed by Lohr et al., who observed that childhood experiences can impact one’s attitude towards wildlife and gardening in adulthood [49]. Other researchers also pointed to the significance of memories tied with garden settings, as memories of previously encountered gardens were observed in the elderly [17]. The results of our survey clearly showed that aromas can also bring to mind summertime relaxation and pleasant memories of vacation trips. The application of plants such as lavender or rosemary in Central European climate conditions, despite previously not being recommended, can stimulate these distinct memories, especially of travel to warmer areas of Europe.

Smells that bring to mind positive associations, when accounting for clearly pleasant memories, can improve the mood and sense of wellbeing of those who experience them. In our survey, a significant percentage of respondents, who were big-city residents, associated smells with good memories, which means that it can be argued that sensory gardens that stimulate the sense of smell of residents of big cities can improve the quality of life for individuals in a city and their overall wellbeing. Winterbottom and Wagenfeld [3] observed that the smell of lavender Lavandula sp., rose Rosa sp. and salvia Salvia sp. improved mood and eased stress, while the smell of mint Mentha sp. and citruses were perceived as invigorating or overwhelming. Lavender and mint were often identified in our study as a respondent’s preferred plant, which brought to mind highly positive associations. However, salvia, despite reactions to its smell being reported as either positive or indifferent, was identified as personally significant or bringing to mind special memories by very few respondents. These results are important indicators for designers of therapeutic sensory gardens intended for construction in urban settings.

Based on the survey’s results, we also noted that a significant portion of the respondents tied their favorite smells with beverages and food overall. This may indicate that adding such herbs to meals served in cafes operating alongside sensory gardens can enhance and extend the positive effect that appears as a result of a good memory and can thus result in greater therapeutic benefits and an elevated sense of wellbeing. Trojanowska argued that access to food and drink should be an attribute of a park with therapeutic features [39]. There are cases of Polish sensory gardens that feature a coffee shop, such as the garden near the J. Czapski Museum in Kraków.

Our analysis of Polish herbal gardens with sensory features using the Trojanowska method [39,40] as adapted by Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz et al. [6] demonstrated that such gardens have a medium therapeutic potential. It also revealed their limitations. One major problem in cities may be the existence of poor-quality greenspaces, which is a factor that contributes to human health, as it was observed that in urbanized areas such greenery, despite being present, may not impart as many health benefits as good-quality greenspace [50]. The higher adaptability of such gardens to disabled persons (attribute 1: D-5) is also notable, as sensory gardens can be visited by this demographic. The potential personalization of space (attribute 4: A-1) was also found to be overlooked and may prevent visitors from forming a deeper connection with a garden.

In the herbal gardens under analysis, the absence of water features was a major problem (attributes 3: A-3 and 5: A-2). Panel paintings depicted medieval European gardens as equipped with fountains, including in settings with aromatic plants [51]. Water is a significant element in therapeutic gardens and its application, particularly when it is in motion, greatly enhances their therapeutic potential [3,48]. Water is an excellent tool of expanding sensory stimuli, especially auditory, visual, and tactile ones [3]. Most respondents were of the opinion that in a garden with aromatic plants, sounds associated with water, e.g., produced by a small fountain, would be perceived positively. They also noted the positive impact of water on a garden’s microclimate, e.g., by humidifying the air and lowering temperature. In our opinion, this highlights the existence of a need for flowing water among city residents and shows that water can positively affect people during periods of high temperature that occur in cities during summer.

The growing water deficit linked to climate change and progressively increasing global warming and water evaporation leads to the problem of supplying plants with water in agriculture and horticulture, and it is not limited to Poland [21]. It also concerns urban sensory gardens, wherein the urban heat island effect further escalates the situation [23,52]. Our survey revealed that the majority of the surveyed residents of a big city, in this case Kraków, found the source of water used to irrigate gardens to be a significant issue. Most respondents expressed the opinion that harvesting stormwater and rainwater for this purpose would be preferable to the use of grid-sourced water. This may indicate that city residents have an awareness of contemporary water-accessibility problems, the significance of water overall and pro-environmental solutions in this regard.

Author Contributions

Methodology, I.K.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.-M.; writing—review and editing, Ł.M. and K.P.; visualization, Ł.M. and K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers and editor for their accurate comments and assistance in improving the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harasimowicz, A. Green spaces as a part of the city structure. Ekon. Sr. 2018, 2, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, J.M. Hype, Hyperbole, and Health: Therapeutic site design. In Urban Lifestyles: Spaces, Places People; Benson, J.F., Rowe, M.H., Eds.; Brookfield A. A. Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Winterbottom, D.; Wagenfeld, A. Therapeutic Gardens: Design for Healing Spaces; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, H. Sensory Garden in Special Schools: The issues, design and use. J. Des. Built Environ. 2009, 5, 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, H. Affordances of Sensory Garden towards Learning and Self Development of Special Schooled Children. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2012, 4, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz, I.; Moszkowicz, Ł.; Porada, K. Evolution of the Concept of Sensory Gardens in the Generally Accessible Space of a Large City: Analysis of Multiple Cases from Kraków (Poland) Using the Therapeutic Space Attribute Rating Method. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajchman-Świtalska, S.; Zajadacz, A.; Lubarska, A. Recreation and Therapy in Urban Forests—The Potential Use of Sensory Garden Solutions. Forests 2021, 12, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensory Trust. Available online: Sensorytrust.org.uk/information/factsheets/sensory-garden-1.html (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Bengtsson, A.; Grahn, P. Outdoor environments in healthcare settings: A quality evaluation tool for use in designing healthcare gardens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska-Kłęk, L. ABC Zielonej Opieki. In Seria „Biblioteka Nestora”, t. VIII.; Dolnośląski Ośrodek Polityki Społecznej: Wrocław, Poland, 2016; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, D. Europe’s Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Their Use, Trade and Conservation; TRAFFIC International: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rostafiński, J. Wpływ przeżyć chłopięcych Mickiewicza na obrazy ostatnich dwu ksiąg Pana Tadeusza oraz o święceniu ziół na Matkę Boską Zielną. Pol. Akad. Umiejętności. Rozpr. Wydziału Filoz. 1922, 61, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hodor, K. Cloister gardens and their role in shaping the urban tissue of Cracow/Ogrody klasztorne i ich rola w kształtowaniu tkanki urbanistycznej miasta Krakowa. Czas. Tech. 2012, z. 6-A, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Majdecki, L. Historia Ogrodów; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN SA: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zajadacz, A.; Lubarska, A. Sensory gardens as places for outdoor recreation adapted to the needs of people with visual impairments. Studia Perieget. 2020, 2, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Kalaylioglu, Z.; Ekren, E. Use of medicinal and aromatic plants in therapeutic gardens. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2018, 52, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.L.; Masser, B.M.; Pachana, N.A. Positive aging benefits of home and community gardening activities: Older adults report enhanced self-esteem, productive endeavours, social engagement and exercise. SAGE Open Med. 2020, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Tilburg, W.A.P.; Sedikides, C.; Wildschut, T.; Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M. How nostalgia infuses life with meaning; From social connectedness to self-continuity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A. Weryfikacja rolniczo-klimatyczna regionalizacji Polski w świetle współczesnych zmian klimatu. Acta Agrophysica 2009, 13, 803–812. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, M.P.; Best, M.J. Climate change in cities due to global warming and urban effects. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L09705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwed, M.; Karg, G.; Pińskwar, I.; Radziejewski, M.; Graczyk, D.; Kędziora, A.; Kundzewicz, Z.W. Climate change and its effect on agriculture, water resources and human health sectors in Poland. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci 2010, 10, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagiełło, P.; Jefimow, M.K.; Strużewska, J. Zmiana narażenia na wysoką temperaturę w Polsce w horyzoncie do 2100 roku na podstawie projekcji klimatycznych EURO-CORDEX. In Współczesne Problemy Klimatu Polski; Chojnacka-Ożga, L., Lorenc, H., Eds.; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej, Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2019; pp. 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bokwa, A.; Hajto, M.; Walawender, J.P.; Szymanowski, M. Influence of diversified relief on the urban heat island in the city of Kraków, Poland. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2015, 122, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winbourne, J.B.; Jones, T.S.M.; Garvey, S.M.; Harrison, J.L.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Templer, P.H.; Hutyra, L.R. Tree transpirations and urban temperatures: Current understanding, implications, future research directions. BioScience 2020, 70, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Lin, B.B.; Dean, J.; Barber, E.; Fuller, R.A. Health Benefits from nature experiences depend on dose. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Health benefits for gardens in hospitals. In Proceedings of the Plants for People International Exhibition Floriade, Haarlemmermeer, The Netherlands, 6 April–20 October 2002. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, A.; Hartig, T.; Staats, H. Preference for Nature in Urbanized Societies: Stress, restoration, and the pursuit of sustainability, J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of Interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 1, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adevi, A.A.; Mårtensson, F. Stress rehabilitation through garden therapy: The garden as a place in the recovery from stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldwell, D.F.; Evans, K.L. Visits to urban green-space and the countryside associate with different components of mental well-being and are better predictors than perceived or actual local urbanisation intensity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 175, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabai, A.; Quiroga, S.; Martinez-Juarez, P.; Higginns, S.; Taylor, T. The nexus between climate change, ecosystem services and human health; towards a concepyual framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houlden, V.; Scott, W.; de Albuquerque, J.; Javris, S.; Rees, K. The relationship between greenspace and the mental wellbeing of adulds: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kępińska-Kasprzak, M.; Struzik, P. Reakcja roślin dziko rosnących na obserwowane ocieplenie klimatu. In Współczesne Problemy Klimatu Polski; Chojnacka-Ożga, L., Lorenc, H., Eds.; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej, Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2019; pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz, I.; Moszkowicz, Ł. Selected problems of Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle presence in urban spaces: The case of the city centre of Kraków. In Proceedings of the Plants Urban Areas Landscape International Scientific Conference, Nitra, Slovakia, 14–15 May 2014; pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudnik-Wojcikowska, B. The effect of temperature on the spatial diversity of urban flora. Phytocoen. Suppl. Cartogr. Geobot. 1998, 10, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Suchecka, A.; Giergiel, T. Otwarcie Sandomierskiego Ogrodu Marcina z Urzędowa. Wiadomości. Bot. 2015, 59, 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Zajadacz, A.; Lubarska, A. Ogrody Sensoryczne Jako Uniwersalne Miejsca Rekreacji Dostosowane Do Potrzeb Osób Niewidomych W Kontekście Relacji Człowiek-Środowisko; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Medwecka-Kornaś, A. Czynniki naturalne, wpływające na rozmieszczenie geograficzne roślin w Polsce. In Szata Roślinna Polski; Szafer, W., Zarzycki, K., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1972; pp. 35–94. [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowska, M. Parki i Ogrody Terapeutyczne; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowska, M. The Universal Pattern of Design for Therapeutic Parks. Methods of Use. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2018, 9, 1410–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowska, M. Therapeutic qualities and sustainable approach to heritage of the city. The coastal strip in Gdańsk, Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneta, W.; Dolatowski, J. Dendrologia; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2011; p. 544. [Google Scholar]

- Muza SA. Wielka Encyklopedia Przyrody. Rośliny Kwiatowe; Muza SA: Warszawa, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moszkowicz, Ł.; Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz, I. Impact of the public parks location in the city on the richness and diversity of herbaceous vascular plants on the example of Krakow Southern Poland. In Proceedings of the Plants Urban Areas Landscape International Scientific Conference, Nitra, Slovakia, 7–8 November 2019; pp. 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Moszkowicz, Ł.; Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz, I.; Porada, K. Relationship between Parameters of Public Parks and Their Surroundings and the Richness, Diversity and Species Composition of Vascular Herbaceous Plants on the Example of Krakow in Central Europe. Landsc. Online 2021, 94, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz, I.; Moszkowicz, Ł.; Porada, K. Znaczenie miejskich ogrodów sensorycznych o cechach przyjaznych organizmom rodzimym, na przykładzie dwóch przypadków z terenu dużych miast europejskich: Krakowa i Londynu. In Integracja Sztuki i Techniki w Architekturze i Urbanistyce; Wydawnictwa Uczelniane Uniwersytetu Technologiczno-Przyrodniczego: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2020; pp. 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Nowacki, J.; Bunalski, M.; Sienkiewicz, P. Fauna jako istotny element hortiterapii. In Hortiterapia Jako Element Wspomagający Leczenie Tradycyjne; Krzymińska, A., Ed.; Rhytmos: Poznań, Poland, 2012; pp. 117–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Marcus, C.; Barnes, M. Gardens in Healthcare Facilities: Uses, Therapeutic Benefits, and Design Recommendations; The Center for Health Design, Inc.: Concord, CA, USA, 1995; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Lohr, V.I.; Pearson-Mims, C.H. Children’s active and passive interactions with plants influence their attitudes and actions toward trees and gardening as adults. Hort Technol. 2015, 15, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Greenspace, urbanity and health: Relationships in England. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulesza, P. Plants in 15th-Century Netherlandish Painting: A Botanical Analysis of Selected Paintings; Wydawnictwo KUL: Lublin, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbarczyk, E.; Kalbarczyk, R. Typology of climate change adaptation measure in Polish cites up to 2030. Land 2020, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).