Using Land to Promote Refugee Self-Reliance in Uganda

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Defining Displaced Persons

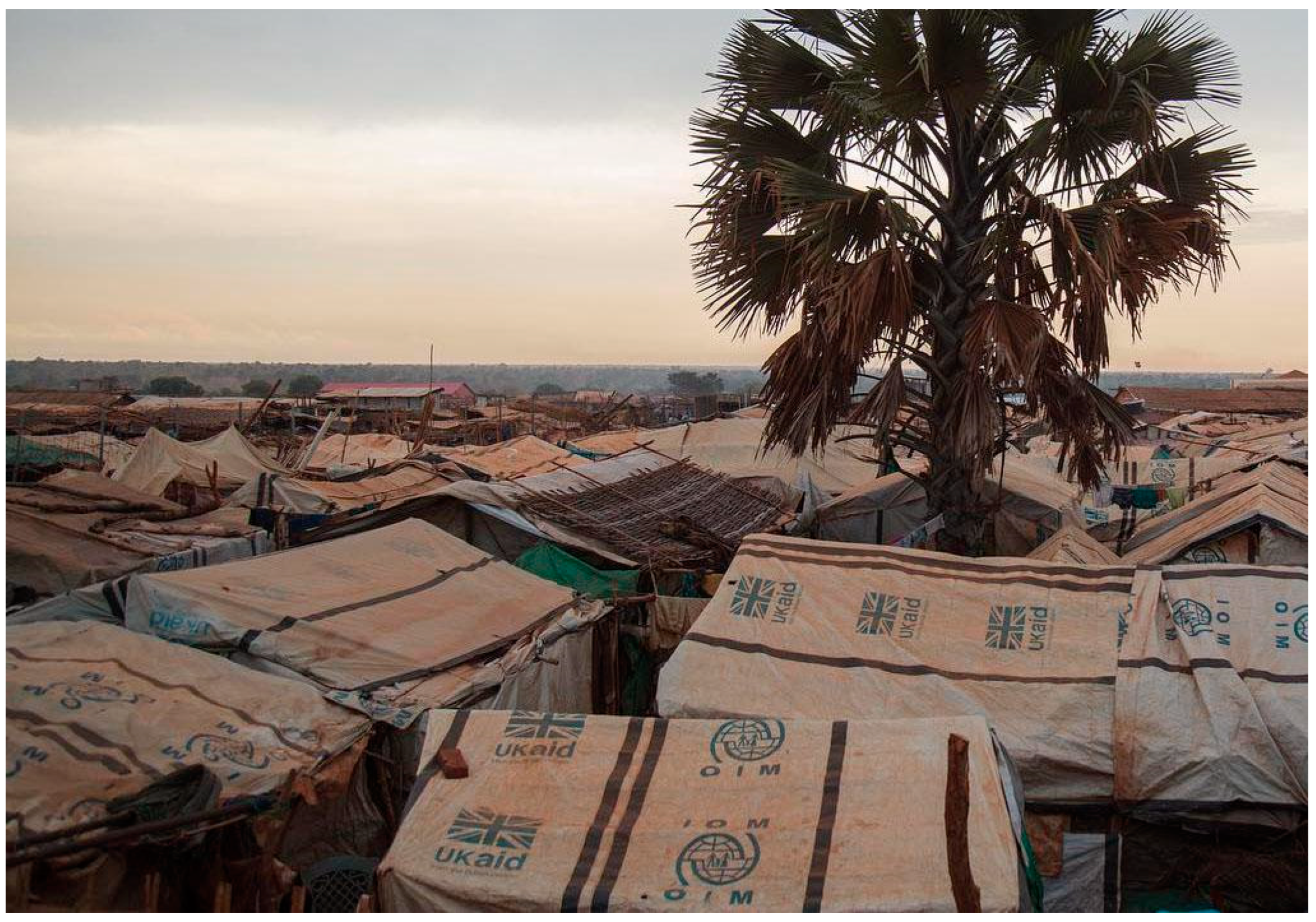

2.2. Refugee Camps

2.3. Integrated Settlements and Self-Relance

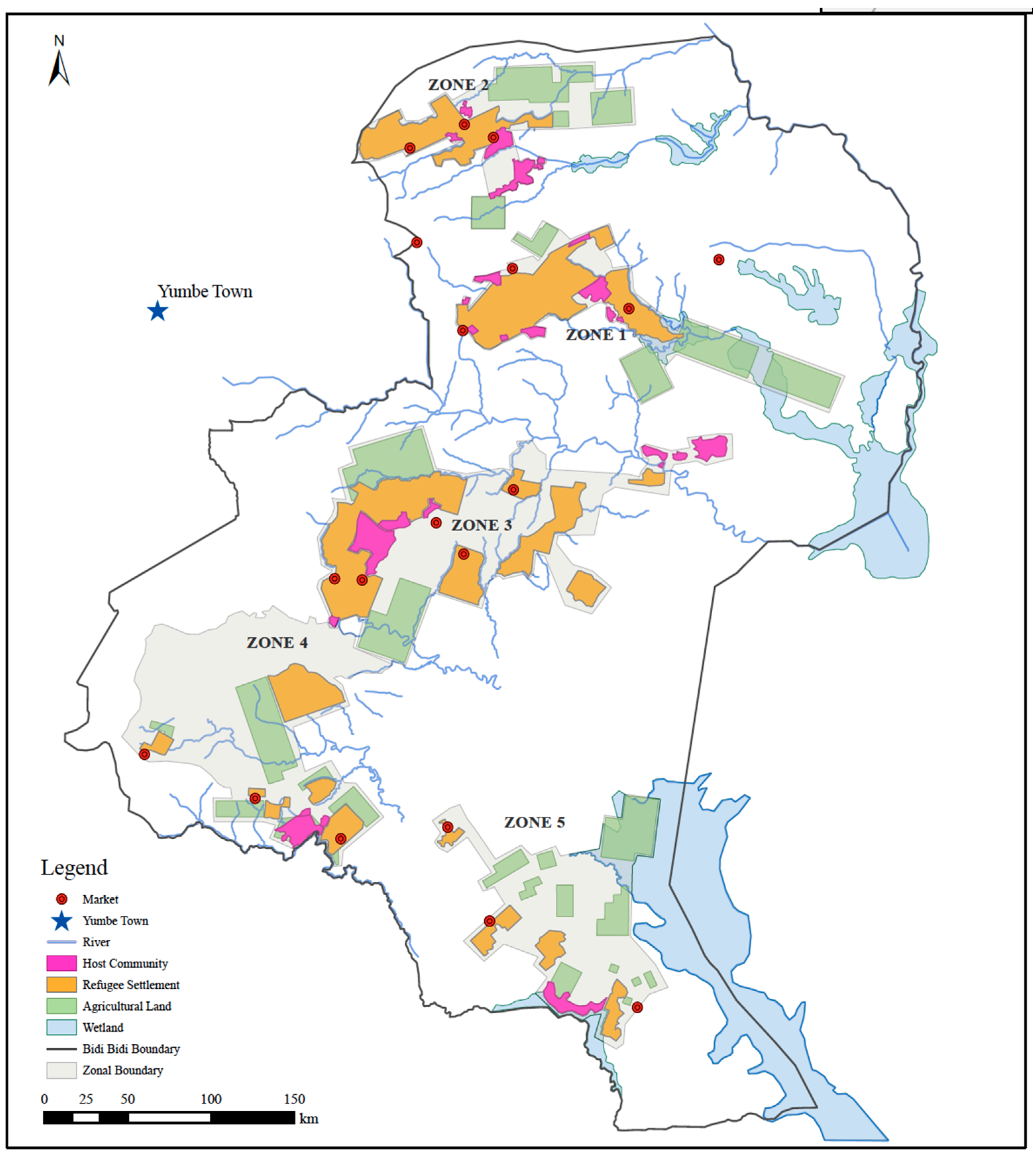

2.4. Context

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Establishment of Bidi Bidi

“The land belongs to the people. It is not government land. And when the refugees came, the people willingly gave their land, freely without any money—because of the plight of the Sudanese refugees. When the refugees will go back to their country this land falls back to the landlords who gave it… [the local people benefit by getting access to] education, health, and then there are also other social services. Like they are giving water drilled, boreholes...They [the residents of the host community] get cheap food from the refugees, they buy. They can even exchange animals because communities have animals and the refugees can give them food [in exchange]. [The residents of the host community get] services like road construction, maintenance of the road and so on.”

“We (OPM) started demarcating that area and we produced, I think, over 2000 plots within one or two days. And then the refugees came... we spotted them along the road. And the UNHCR bulldozer started creating the roads inside, because it was a thicket. And besides that, there were streams. There were no bridges or culverts to pass on. And then, there were rocky areas but people had to be put on the land because the next day another 4000 people would come to the reception center…. So that’s how we started it. And then later on, of course, the site planner (UNHCR) kept on drawing his plan but the movements of people were so great that within 4 months Bidi Bidi was already full with over 200,000 persons…we made 40 kilometers of roads inside there and … in the host community where the roads would pass. And then the rest of the infrastructure was just put there later on, the schools, health centers…”

“…we have an emergency situation so most infrastructure put in is temporary. We need to put facilities that can accommodate people for the meantime. … from now onwards investments we need to do when in regards to infrastructure we need to put in permanent structures that can outlive the situation we are in in case the registration of refugees ends infrastructure needs to benefit the local community, as far as infrastructure development goes.”

“One key recommendation should have been administration whereby you want to start NGO, camp, IDP camp, one thing you should ensure is such area, should have physical development, structured plan.”

“The minister of disaster came out clearly and said we need to get areas where we can relocate people, and how do we relocate these people? You need to plan those areas. Meaning there is some bit of disaster management plan, but whatever we do in Uganda here has been in a piecemeal way. We have not been having something comprehensive. We just come and do something in a piecemeal way, to arrest a situation. And when this situation is done, we tend to forget, and not until we also succumb to a similar situation…But I think, what has happened with Bidi Bidi has taught all of us, has given us a lesson and we’re now looking at handling issues in a comprehensive way.”

“As a physical planner, the physical development plan is very key because it is going to streamline all the other small activities going to take place there. It will lay out the infrastructure plan … to be very clear.”

“Actually, it has beaten the town because of the beautiful structures which they have put [in]... the already existing roads, eh, should be well maintained. If they get the funds to allow they can even tarmac the roads…And then if we have proper physical planning, that... can involve the local government in planning and so on, the settlement can become a model city in the future.”

4.2. Current Conditions

“The settlements are really sprawling out… People while initially may have been allocated these orthogonal [plots], rather generous in terms of size, but people are actually more densely … clustered around trading center hubs. And they would leave for …agriculture, they separated entirely, and they’d farm different parts of the landscape. So...what I’m trying to say is that people [are] not really sticking to the expected grid… the tendency was to have the thriving more urban center, the residential and trading and markets, etc. And then to have buffers between these hubs, you actually [have more] agricultural land…It wasn’t planned. But that has been the tendencies, so people would be allocated these parts, but then they would actually not build on them. They would use those parts purely for agriculture. And then they would build next to neighbors and friends and extended relatives, families who’d already crossed circles”.

4.3. Deforestation

5. Discussion

5.1. Plot Allocation and Reality of Self-Reliance

5.2. The Need for Integration

5.3. Protecting the Environment from Irreparable Damage

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1. | This can be a challenging and complex process, but in countries such as Uganda that experience largescale influxes of displaced persons they receive refugee status on a prima facie basis. This means the state recognizes refugee status due to “basis of the readily apparent, objective circumstances in the country of origin giving rise to exodus” [17]. |

| 2. | |

| 3. | The first author established social and professional networks working with SCA and other organizations on the border of South Sudan and Uganda for four years. |

| 4. | Although the first author interacted (e.g., lived and ate) with refugees, time constraints prevented acquiring approval from IRB and OPM to formally record and interview refugees. Although we incorporated participant observation, we acknowledged the limitations of not formally intervieing the refugees themselves. We are actively persuing permission to conduct such interviews. |

| 5. | Although formal interviews were in English, there were times in which Arabic (Juba) was used in interactions with refugees. |

| 6. | Based on many conversations with residents, resentment was not expressed toward refugees as they understood their plight. However, some of their resentment was directed toward the office of the prime minister for lack of adequate “compensation” for their land. |

| 7. | While most refugees in Bidi Bidi are South Sudanese, they do not share a single, homogenous culture. While some of the refugees come from urban areas such as Juba, the majority come from rural areas and are either agriculturalists or pastoralists and self-identify as farmers [53]. Even though many refugees were farmers, conflicts have arisen between “agriculturalists” and “pastoralists”. |

| 8. | Recent assessment conducted by UNHCR estimated that on average 3.5 kg of fuelwood was used per person per day in Bidi Bidi [55]. |

| 9. | To demonstrate the importance of deforestation being experienced within and outside of Bidi Bidi, World Refugee Day on 20 June 2018 was held under the theme of “Take a step #withrefugees protect the environment”. Numerous local, national (including the Ugandan vice president), international and refugee leaders publicly discussed the pressing use of deforestation in Bidi Bidi. This was followed with a symbolic joint activity of planting 10,000 trees by both host and refugee community members (the first author took part in public discussion and activity). |

References

- UNHCR. Global Trends-Forced Displacement in 2019-UNHCR. 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- UNHCR. Refugee Statistics. 2018. Available online: https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/statistics/ (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- UNHCR. Protracted Refugee Situations. 10 June 2004. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/40c982172.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Unruh, J.D. Refugee resettlement on the Horn of Africa. The integration of host and refugee land use patterns. Land Use Policy 1993, 10, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Performance Snapshot, Uganda Refugee Response Plan (RRP) 2019–2020. 2020. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/76226 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- World Bank Group. An Assessment of Uganda’s Progressive Approach to Refugee Management. An Assessment of Uganda’s Progressive Approach to Refugee Management; World Bank: Washington DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jansen, B.J. “Digging aid”: The camp as an option in east and the horn of Africa. J. Refug. Stud. 2016, 29, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A. Parameters for camps and settlements. FMO Thematic Guide. 2002. Available online: https://www.alnap.org/system/files/content/resource/files/main/fmo021.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Alexander, B.; Paul, C. Refuge: Transforming A Broken Refugee System; Allen Lane; An Imprint of Penguin Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, A.; Chaara, I.; Omata, N.; Sterck, O. Refugee Economies in Uganda: What Difference Does the Self-Reliance Model Make? RSC: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hovil, L.; Uganda’s Refugee Policies: The History, the Politics, the Way Forward. International Refugee Rights Initiative. 2018. Available online: http://www.refworld.org/cgi- (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Tuepker, A.; Chi, C. Evaluating integrated healthcare for refugees and hosts in an African context. Health Econ. Policy Law 2009, 4, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, T. Between a camp and a hard place: Rights, livelihood and experiences of the local settlement system for long-term refugees in Uganda. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2006, 44, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werker, E. Refugee camp economics. J. Refug. Stud. 2007, 20, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S. New Issues in Refugee Research: The “Refugee Aid and Development” Approach in Uganda: Empowerment and Self-Reliance of Refugees in Practice. UNHCR Working Paper Series, no. 131. Geneva: UNHCR. 2006. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/4538eb172.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Dryden-Peterson, S.; Hovil, L. A Remaining Hope for Durable Solutions: Local Integration of Refugees and Their Hosts in the Case of Uganda. Refug. Can. J. Refug. 2004, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Prima Facie Status and Refugee Protection. New Issues in Refugee Research. 2002. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/3db9636c4.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Dodman, D.; Satterthwaite, D. Institutional capacity, climate change adaptation and the urban poor. IDS Bull. 2008, 39, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smit, W.; Parnell, S. Urban sustainability and human health: An African perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdlik, A. Ill-health and poverty: A literature review on health in informal settlements. Environ. Urban. 2011, 23, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Shelter, Alternatives to Camps. 2020. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/shelter.html?query=how+many+live+in+camp+setting (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- UNHCR. What Is a Refugee Camp? Definition and Statistics: USA for UNHCR. 2020. Available online: https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/camps/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- McConnachie, K. Camps of Containment: A Genealogy of the Refugee Camp. Humanit. Int. J. Hum. Rights Humanit. Dev. 2016, 7, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Owens, P. Reclaiming “bare life”? Against Agamben on refugees. Int. Relat. 2009, 23, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibreab, G. Spatially Segregated Settlement Sites. Refuge 2007, 24, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. What Is a Refugee Camp? Explorations of the Limits and Effects of the Camp. J. Refug. Stud. 2015, 29, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivius, E. Sites of repression and resistance: Political space in refugee camps in Thailand. Crit. Asian Stud. 2017, 49, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, T. Bureaucratizing The Good Samaritan: The Limitations Of Humanitarian Relief Operations; Routledge: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Autesserre, S. Peaceland: Conflict Resolution and the Everyday Politics of International Intervention; Cambridge University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–329. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S. Politics of Innocence: Hutu Identity, Conflict and Camp Life; Berghahn Series; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Malkki, L. Purity and Exile: Violence, Memory, and National Cosmology among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jahre, M.; Kembro, J.; Adjahossou, A.; Altay, N. Approaches to the design of refugee camps: An empirical study in Kenya, Ethiopia, Greece, and Turkey. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain. Manag. 2018, 8, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNHCR. Emergency Handbook, Camp Planning Standards (Planned Settlements). 2020. Available online: https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/45581/camp-planning-standards-planned-settlements (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Norwegian Refugee Council/Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (NRC/IDMC). Camp Management Toolkit, May 2008. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/526f6cde4.html (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Betts, A.; Bloom, L.; Kaplan, J.D.; Omata, N. Refugee Economies: Forced Displacement and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Garcia, J.; Walker, S.; Bartlett, A.; Onder, H.; Sanghi, A. Do refugee camps help or hurt hosts? The case of Kakuma, Kenya. 2018. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 130, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, Ö.; Loschmann, C.; Fransen, S.; Siegel, M. Is the Education of Local Children Influenced by Living near a Refugee Camp? Evidence from Host Communities in Rwanda. Int. Migr. 2019, 57, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylora, J.E.; Filipski, M.J.; Alloush, M.; Gupta, A.; Valdes, R.I.R.; Gonzalez-Estrada, E. Economic impact of refugees. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Washington, DC, USA, 20 June 2016; Volume 113, pp. 7449–7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobsen, K. Can refugees benefit the state? Refugee resources and African statebuilding. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2002, 40, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komakech, H.; Atuyambe, L.; Orach, C.G. Integration of health services, access and utilization by refugees and host populations in West Nile districts, Uganda. Confl. Health 2019, 13, 2017–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. Environmental conflict between refugee and host communities. J. Peace Res. 2005, 42, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, B.E. Refugees in western Tanzania: The distribution of burdens and benefits among local hosts. J. Refug. Stud. 2002, 15, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNHCR. Concept Note: Transitional Solutions Initiative (TSI), UNDP and UNHCR in Collaboration with the World Bank. 2010. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/partners/partners/4e27e2f06/concept-note-transitional-solutions-initiative-tsi-undp-unhcr-collaboration.html (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- UNHCR. Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework: The Uganda Model. 2018. Available online: https://globalcompactrefugees.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/Case%20study-%20comprehensive%20refugee%20response%20model%20in%20Uganda%282018%29.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Harrell-Bond, B.E. Imposing Aid: Emergency Assistance to Refugees; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Handbook for Self-Reliance: Book 1—Why Self-Reliance? 2006. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/44bf3e252.html (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Hunter, M. The Failure of Self-Reliance in Refugee Settlements. POLIS J. 2009, 2, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Draft Energy and Environment Mission Report to Yumbe and Adjumani Settlments. 2006. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/64187#:~:text=Yumbe%20receives%20an%20average%20total,less%20than%2060%20mm%2Fmonth (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- National Population and Housing Census 2014. National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles, Yumbe. 2017. Available online: https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/2014CensusProfiles/YUMBE.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Tavory, I.; Timmermans, S. Abductive Analysis: Theorizing Qualitative Research; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Bringing the New York Declaration to Life Applying the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF), 18 September 2018. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/593e5ce27.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Vogelsang, A. ‘Local Communities’ Receptiveness to Host Refugees: A Case Study of Adjumani District in Times of a South Sudanese Refugee Emergency’, 2017. Thesis, Utrecht University Repository. Available online: https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/353562 (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- UNDP. Understanding Land Dynamics and Livelihood in Refugee Hosting Districts of Northern Uganda (Rep.). 2018. Available online: https://www.africa.undp.org/content/rba/en/home/library/reports/understanding-land-dynamics-and-livelihoods-in-refugee-hosting-d.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Marshall, A. Refugee Camps Struggle as Uganda Water Crisis Intensifies. International Relations Society at NYU. 2019. Available online: https://www.irinsider.org/subsaharan-africa-1/2019/2/28/refugee-camps-struggle-as-uganda-water-crisis-intensifies (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Gianvenuti, A.; Ortman, A.; Kintu, E.; Dannunzio, R. Rapid Woodfuel Assessment: 2017 Baseline for the Bidibidi Settlement, Uganda; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/525ba72a-b9eb-44a2-9326-f559be6ae2f9/ (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Logie, C.H.; Okumu, M.; Latif, M.; Musoke, D.K.; Odong Lukone, S.; Mwima, S.; Kyambadde, P. Exploring resource scarcity and contextual influences on wellbeing among young refugees in Bidi Bidi refugee settlement, Uganda: Findings from a qualitative study. Confl. Health 2021, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosrenaud, E.; Okia, C.A.; Adam-Bradford, A.; Trenchard, L. Agroforestry: Challenges and opportunities in rhino camp and imvepi refugee settlements of arua district, northern uganda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ReDSS. Are Integrated Services a Step towards Integration? A Case Study of Uganda. 2018. Available online: https://regionaldss.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ReDSS-Uganda-Report-FINAL-2019.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Rowley, E.A.; Burnham, G.M.; Drabe, R.M. Protracted refugee situations: Parallel health systems and planning for the integration of services. J. Refug. Stud. 2006, 19, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tete, S.Y.A. “Any place could be home”: Embedding refugees’ voices into displacement resolution and state refugee policy. Geoforum 2012, 43, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell-Bond, B. Can humanitarian work with refugees be humane? Hum. Rights Q. 2002, 24, 51–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Guidance Note-Safe Access to Firewood and Alternative Energy in Humanitarian Settings. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/emergencies/resources/documents/resources-detail/en/c/198366/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berke, T.; Larsen, L. Using Land to Promote Refugee Self-Reliance in Uganda. Land 2022, 11, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030410

Berke T, Larsen L. Using Land to Promote Refugee Self-Reliance in Uganda. Land. 2022; 11(3):410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030410

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerke, Timothy, and Larissa Larsen. 2022. "Using Land to Promote Refugee Self-Reliance in Uganda" Land 11, no. 3: 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030410

APA StyleBerke, T., & Larsen, L. (2022). Using Land to Promote Refugee Self-Reliance in Uganda. Land, 11(3), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030410