No Stakeholder Is an Island: Human Barriers and Enablers in Participatory Environmental Modelling

Abstract

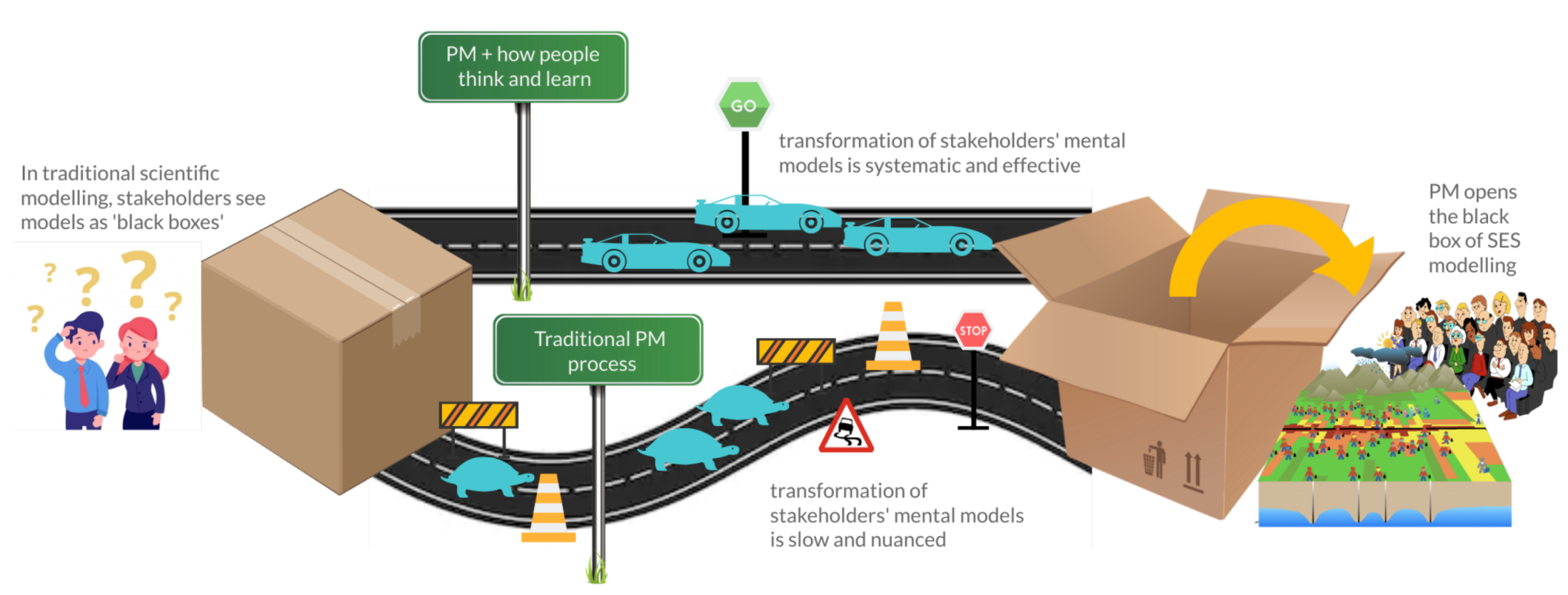

:1. Introduction: Tackling Wicked Problems of SES with Participatory Modelling

2. Human Behaviour: The Achilles Heel of Participatory Modelling

- How can we measure learning, both of stakeholders and the wider community to which they belong?

- How can we identify, categorize, and address issues of communication through participatory modelling?

- How can the PM process actively understand, accommodate, and counter differing biases, beliefs, and values among stakeholders?

- What drives motivation and engagement in a PM process? What role does trust play and how can facilitators create conditions for its success?

- Furthermore, how do we ultimately scale participation in a PM process to ultimately impact the broader system and society at large?

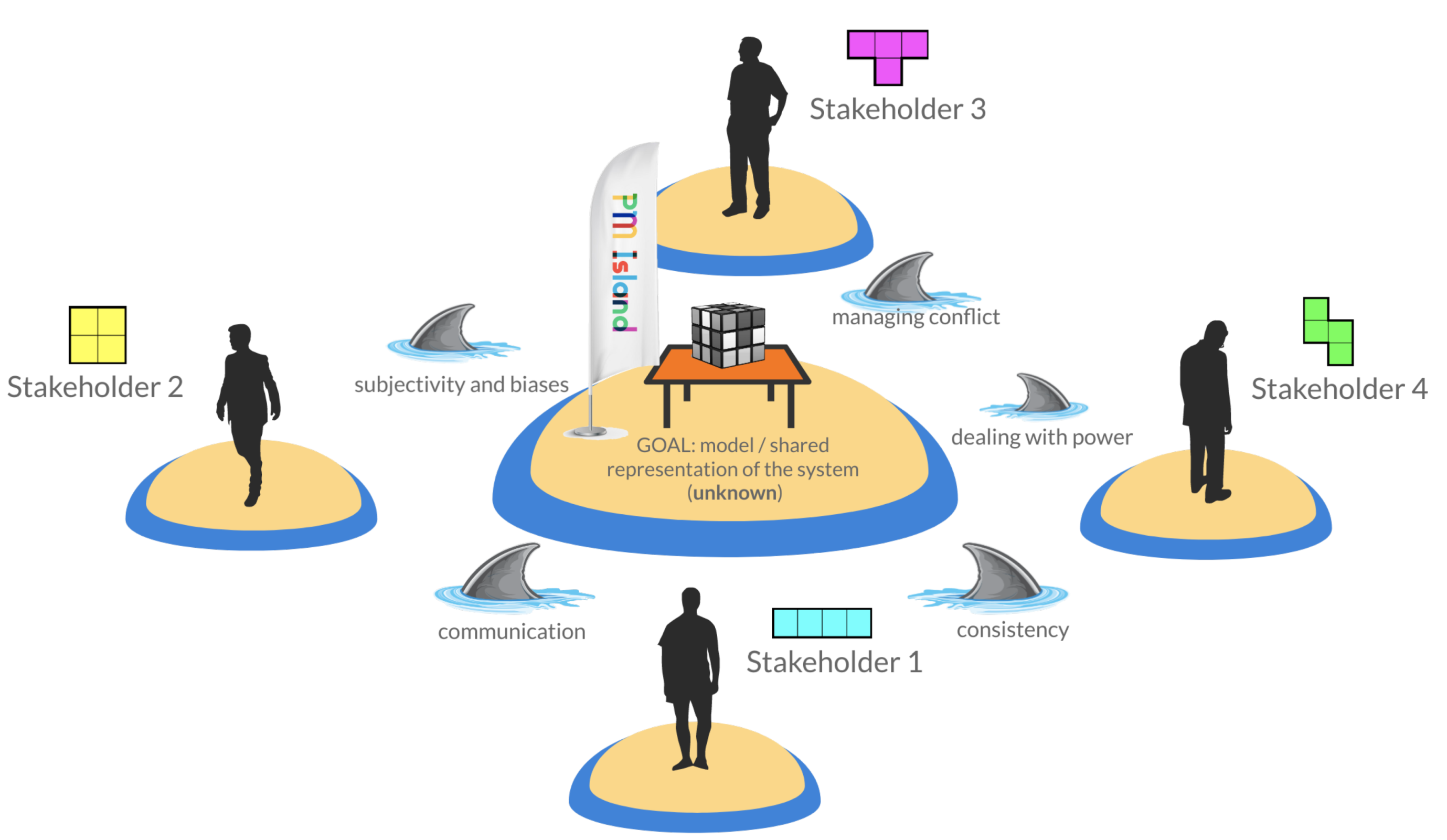

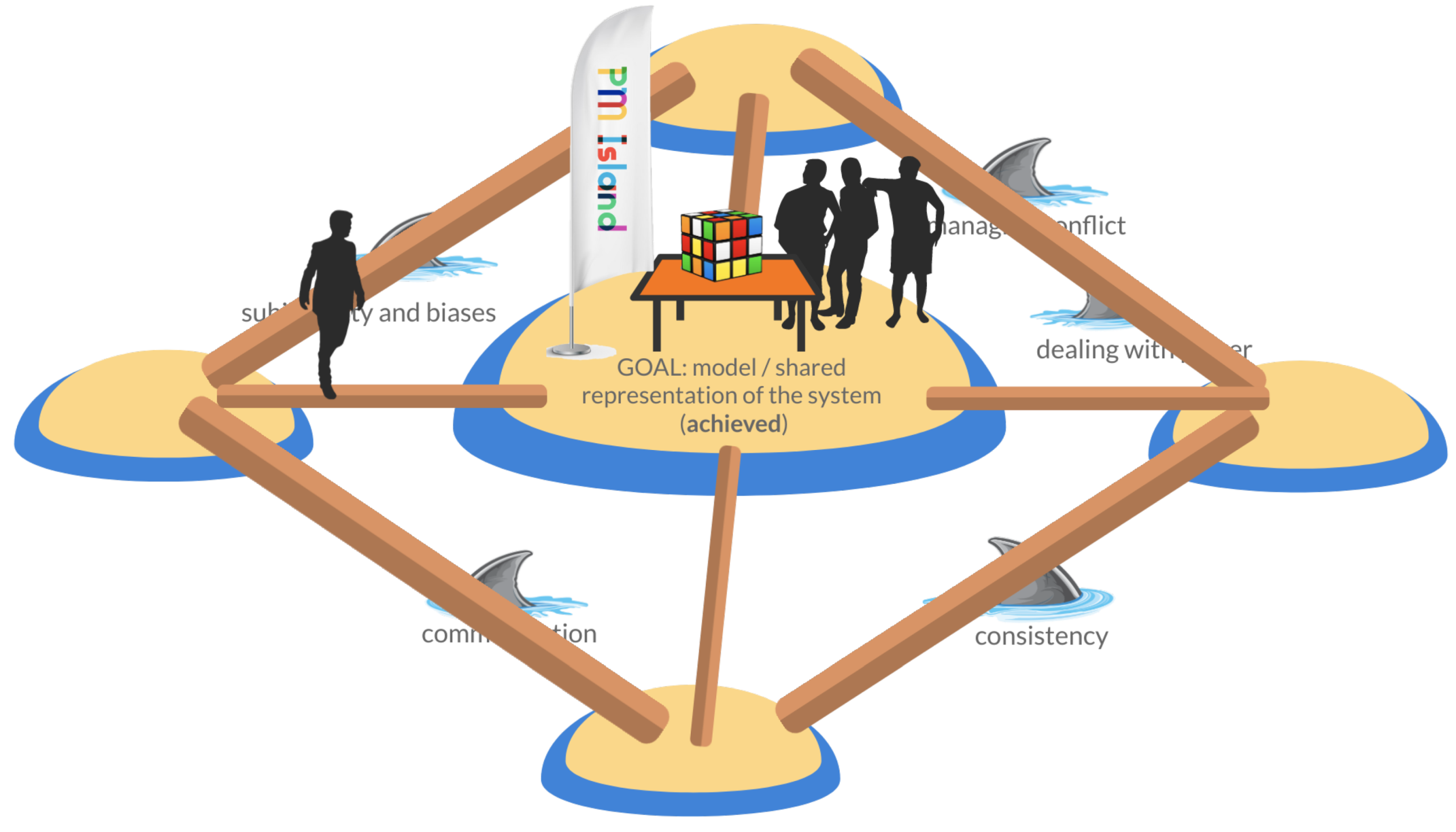

3. Human Barriers in Participatory Environmental Modelling

- Subjectivity and biases;

- Managing conflict;

- Dealing with power;

- Communicating effectively;

- Being consistent.

3.1. Subjectivity and Biases

3.1.1. The Barrier

3.1.2. Some Solutions

3.2. Managing Conflict

3.2.1. The Barrier

“A simple truth occurs when a “proponent of some view—let us call the view p—who endeavors to convince their audience to also adopt p on the basis of the claim that p is simply and obviously true. As it would be mad to reject a simple and obvious truth, the proponent uses their firm assertion that p is a simple truth as a winning argument for p... an appeal to the Simple Truth is a way of outing those who may see themselves as part of the group, but in fact are outliers. It thus sends a strong signal to those in the audience that they must accept p, or else be regarded as an outsider, or worse yet, a poser. This is why Simple Truth is often accompanied by a kind of brow-beating; the speaker affirms p as a Simple Truth, and then pauses to survey the audience for any signs of defection” [82].

3.2.2. Some Solutions

- “You should attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, “Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way”;

- You should list any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement);

- You should mention anything you have learned from your target;

- Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism” [96].

3.3. Dealing with Power

3.3.1. The Barrier

3.3.2. Some Solutions

- Do my experience and skill suggest certain methods? Are those methods best suited for this situation? Have other methods been considered?

- What is my personality or cognitive style comfortable with?

- What is the history here? What methods have worked or not worked?

- What and who am I committed to in this situation?

- What resources do I have at my disposal?

- Do I need to learn more before entering this situation?

- What is the purpose of the system? What should be the purpose?

- Who benefits from the system right now? Who should benefit?

- What is the measure of success in the system right now? What should it be?

- Who controls the success of the system? Should that change?

- Where is there space for stakeholders to reconcile different perspectives on the system and situation at hand?

3.4. Communicating Effectively

3.4.1. The Barrier

3.4.2. Some Solutions

3.5. Being Consistent

3.5.1. The Barrier

3.5.2. Some Solutions

3.6. The Importance of Transdisciplinary Insights

4. Going Forward

- Experimental research should seek to ’test’ the efficiency and effectiveness of the solutions we presented above, both in their ability to impact stakeholder learning and in assessing the trade-offs in the time, resources, and expertise needed to successfully implement them. The challenge of assessing such impacts should not be understated, as isolating variables in social science, particularly with smaller sample sizes common in PM efforts, is difficult. However, starting from results from other fields, as done herein, and implementing their experimental methods (the work of Cialdini and colleagues is a great example) is one area that should be explored further [63,66,150].

- Collaborative efforts with experts from multiple disciplines should continue and expand in pursuit of transdisciplinary solutions to promote stakeholder learning and SES change. While bringing experts and researchers from various disciplines does not guarantee success (and often creates its own headaches), the potential for truly innovative and discipline-spanning solutions is immense. Combining expertise and knowledge from psychology, neuroscience, education, action researchers, negotiation, behavioural economics, and other fields creates the possibility for solutions to emerge that are so much greater than the sum of its parts.

- Stakeholder values, beliefs, and biases shape their worldview and therefore their actions. Cognitive biases tell all of us something about the world is `true’ when reality may say differently. Acknowledging the role that these cognitive biases play and more explicitly incorporating strategies to bring awareness to them and limit their impact can and should be an accepted part of PM facilitation and practice. Research that focuses on addressing a specific bias, say confirmation bias, and exploring how that can be qualitatively and quantitatively limited is a promising area for the future.

- Various authors have called for recording the results of participatory modelling exercises as a way to both learn from past experiences and improve the practice going forward [48,83,135,136]. Work by [151,152] also provided promising developments in PM, investigating the PM process as a series of decision pathways that are influenced by the people involved in the process. Together, the authors advocate for a reflective approach to documentation and decision making and the need to consider alternative pathways during the modelling process to reach the best outcomes. The authors also note the influence of the “human factors” on extending beyond PM to management actions, and propose practices such as reflection, de-biasing, red team, and the necessity of documentation as part of diagramming decision pathways of PM that can complement the building of the model [151,152]. Regardless of whether it is a 4P Framework, Records of Engagement, the Protocol of Canberra, or a new format, the PM community should seek to move towards the increasing standardization of documentation of the process, as has been done with agent-based modelling and the ODD framework [48,83,135,136,153]. Total consensus is unlikely, but there is still value in moving towards a more widely used evaluation framework. There are outstanding questions about the format, understandably, but we hope that the outstanding issues we presented thus far demonstrate the importance of considering the ‘people’ at the centre of the process and the necessity for deliberate and proactive planning on the ‘how’ of their learning as a result.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ives, C.D.; Kendal, D. The role of social values in the management of ecological systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social—Ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.G. The Ways of Wickedness: Analyzing Messiness with Messy Tools. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2012, 25, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.N. Working with wicked problems in socio-ecological systems: Awareness, acceptance, and adaptation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 110, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What is social learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, M.I.; Mochon, D.; Ariely, D. The IKEA effect: When labor leads to love. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System; Technical report; Sustainability Institute: Hartland, VT, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Learning to Think Like an Adult: Core Concepts of Transformation Theory. In Learning as Transformation. Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; Mezirow, J., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, M.; Brown, V.A.; Dyball, R. Social Learning in Environmental Management: Towards a Sustainable Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, S.A. Complex Adaptive Systems: Exploring the known, the unknown, and the unknowable. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 2002, 40, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, M.T.H. Three Types of Conceptual Change: Belief Revision, Mental Model Transformation, and Categorical Shift. In Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change; Vosniadou, S., Ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Henly-Shepard, S.; Gray, S.A.; Cox, L.J. The use of participatory modeling to promote social learning and facilitate community disaster planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 45, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.A.; Ross, H.; Lynam, T.; Perez, P.; Leitch, A. Mental Models: An Interdisciplinary Synthesis of Theory and Methods. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, C.J.; Holling, C.S. Large-scale management experiments and learning by doing. Ecology 1990, 71, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.; Gray, S.; Zellner, M.; Glynn, P.D.; Voinov, A.; Hedelin, B.; Sterling, E.J.; Leong, K.; Olabisi, L.S.; Hubacek, K.; et al. Twelve Questions for the Participatory Modeling Community. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bruggen, A.; Nikolic, I.; Kwakkel, J. Modeling with stakeholders for transformative change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siebenhüner, B.; Rodela, R.; Ecker, F. Social learning research in ecological economics: A survey. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 55, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodela, R. Social learning, natural resource management, and participatory activities: A reflection on construct development and testing. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2014, 69, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rist, S.; Chidambaranathan, M.; Escobar, C.; Wiesmann, U.; Zimmermann, A. Moving from sustainable management to sustainable governance of natural resources: The role of social learning processes in rural India, Bolivia and Mali. J. Rural. Stud. 2007, 23, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundill, G.; Cumming, G.S.; Biggs, D.; Fabricius, C. Soft Systems Thinking and Social Learning for Adaptive Management. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 26, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, E.J. Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems; Wiley: Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Belt, M.; Schiele, H.; Forgie, V. Integrated freshwater solutions—A New Zealand application of mediated modeling. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2013, 49, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.J. Collaborating Across Boundaries: Theoretical, Empirical, and Simulated Explorations. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Black, L.J.; Ran, W.; Andersen, D.L.; Jarman, H.; Richardson, G.P.; Andersen, D.F. Modeling and Simulation as Boundary Objects to Facilitate Interdisciplinary Research. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2019, 36, 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.A.; Stillman, R.A.; Goss-Custard, J.D. Co-creation of individual-based models by practitioners and modellers to inform environmental decision-making. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voinov, A.; Bousquet, F. Modelling with stakeholders. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 1268–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, T.; Jong, W.D.; Sheil, D.; Kusumanto, T.; Evans, K. Review of tools for incorporating community knowledge, preferences, and values into decision making in natural resources management. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuéllar-Padilla, M.; Calle-Collado, Á. Can we find solutions with people? Participatory action research with small organic producers in Andalusia. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddis, E.J.B.; Voinov, A. Participatory Modeling. In Ecological Models; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 2651–2655. [Google Scholar]

- Voinov, A.; Gaddis, E. Values in Participatory Modeling: Theory and Practice. In Environmental Modeling with Stakeholders: Theory, Methods, and Applications; Section 3; Gray, S., Paolisso, M., Jordan, R., Gray, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Renger, M.; Kolfschoten, G.L.; Vreede, G.J.D. Challenges in collaborative modelling: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Simul. Process Model. 2008, 4, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R. Stakeholder analysis and conflict management. In Cultivating Peace: Conflict and Collaboration in Natural Resource Management; Buckles, D., Ed.; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999; pp. 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Public Service Commission (APS). Tackling Wicked Problems: A Public Policy Perspective; Technical report; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Falconi, S.M.; Palmer, R.N. An interdisciplinary framework for participatory modeling design and evaluation-What makes models effective participatory decision tools? Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 1625–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, G.; Blöschl, G.; Loucks, D.P. Evaluating participation in water resource management: A review. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voinov, A.; Kolagani, N.; McCall, M.K.; Glynn, P.D.; Kragt, M.E.; Ostermann, F.O.; Pierce, S.A.; Ramu, P. Modelling with stakeholders - Next generation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 77, 196–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askins, K. `That’s just what I do’: Placing emotion in academic activism. Emot. Space Soc. 2009, 2, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Metcalf, S.S.; Wheeler, E.; BenDor, T.K.; Lubinski, K.S.; Hannon, B.M. Sharing the floodplain: Mediated modeling for environmental management. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huvila, I.; Anderson, T.D.; Jansen, E.H.; McKenzie, P.; Westbrook, L.; Worrall, A. Boundary objects in information science research: An approach for explicating connections between collections, cultures and communities. Proc. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinov, A.; Jenni, K.; Gray, S.; Kolagani, N.; Glynn, P.D.; Bommel, P.; Prell, C.; Zellner, M.; Paolisso, M.; Jordan, R.; et al. Tools and methods in participatory modeling: Selecting the right tool for the job. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 109, 232–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmitt Olabisi, L.; Adebiyi, J.; Traoré, P.S.; Kakwera, M.N. Do participatory scenario exercises promote systems thinking and build consensus? Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2016, 4, 000113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, M.L. Embracing complexity and uncertainty: The potential of agent-based modeling for environmental planning and policy. Plan. Theory Pract. 2008, 9, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMere, K.; Mäntyniemi, S.; Vanhatalo, J.; Haapasaari, P. Making the most of mental models: Advancing the methodology for mental model elicitation and documentation with expert stakeholders. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 124, 104589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.D.; Croke, B.F.; Guariso, G.; Guillaume, J.H.; Hamilton, S.H.; Jakeman, A.J.; Marsili-Libelli, S.; Newham, L.T.; Norton, J.P.; Perrin, C.; et al. Characterising performance of environmental models. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 40, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent, R.M.; Voinov, A.; Maxwell, T.; Cuddy, S.M.; Rahman, J.M.; Seaton, S.; Vertessy, R.A.; Braddock, R.D. Comparing modelling frameworks: A workshop approach. Environ. Model. Softw. 2006, 21, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Voinov, A.; Paolisso, M.; Jordan, R.; Bendor, T.; Bommel, P.; Glynn, P.; Hedelin, B.; Hubacek, K.; Introne, J.; et al. Purpose, processes, partnerships, and products: Four Ps to advance participatory socio-environmental modeling. Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamalainen, R.P. Behavioural issues in environmental modelling—The missing perspective. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 73, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, M.L.; Lyons, L.; Hoch, C.J.; Weizeorick, J.; Kunda, C.; Milz, D.C. Modeling, Learning, and Planning Together: An Application of Participatory Agent-based Modeling to Environmental Planning. J. Urban Reg. Inf. Syst. Assoc. 2012, 24, 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Radinsky, J.; Milz, D.; Zellner, M.; Pudlock, K.; Witek, C.; Hoch, C.; Lyons, L. How planners and stakeholders learn with visualization tools: Using learning sciences methods to examine planning processes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1296–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.A.; Jakeman, A.J.; Barreteau, O.; Borsuk, M.E.; ElSawah, S.; Hamilton, S.H.; Henriksen, H.J.; Kuikka, S.; Maier, H.R.; Rizzoli, A.E.; et al. Selecting among five common modelling approaches for integrated environmental assessment and management. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 47, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazonas, I.T.; Kawa, N.C.; Zanetti, V.; Linke, I.; Sinisgalli, P.A. Using Rich Pictures to Model the `Good Life’ in Indigenous Communities of the Tumucumaque Complex in Brazilian Amazonia. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, M.; Du Toit, D.; Pollard, S. ARDI: A co-construction method for participatory modelling in natural resources management. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Squires, H.; Renn, O. Can Participatory Modelling Support Social Learning in Marine Fisheries? Reflections from the Invest in Fish South West Project. Environ. Policy Gov. 2011, 21, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, M. Forms of Participatory Modelling and its Potential for Widespread Adoption in the Water Sector. Environ. Policy Gov. 2011, 21, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisette, J.T.; Cravens, A.E.; Miller, B.W.; Talbert, M.; Talbert, C.; Jarnevich, C.; Fink, M.; Decker, K.; Odell, E.A. Crossing Boundaries in a Collaborative Modeling Workspace. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2017, 30, 1158–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, B.E. Energy transition dynamics: Does participatory modelling contribute to alignment among differing future world views? Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2019, 36, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow, 1st ed.; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.S.B.T.; Stanovich, K.E. Dual-Process Theories of Higher Cognition: Advancing the Debate. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, P.D.; Voinov, A.A.; Shapiro, C.D.; White, P.A. From data to decisions: Processing information, biases, and beliefs for improved management of natural resources and environments. Earth’s Future 2017, 6, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R. The Focus Theory of Normative Conduct. Handb. Theor. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 24, 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.H. From cashews to nudges: The evolution of behavioral economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 2018, 108, 1265–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ariely, D.; Wertenbroch, K. Procrastination, Deadline, and Performance: Self-Control by Precommitment. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenrick, D.T.E.; Goldstein, N.J.E.; Braver, S.L.E. Six Degrees of Social Influence: Science, Application, and the Psychology of Robert Cialdini; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinov, A.; Perez, P.; Castilla-Rho, J.C.; Kenny, D.C. Integrated ecological economic modeling: What is it good for? In Sustainable Wellbeing Futures; Costanza, R., Erickson, J.D., Farley, J., Kubiszewski, I., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 316–341. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.A.; Shaw, S.; Ross, H.; Witt, K.; Pinner, B. The study of human values in understanding and managing social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ducrot, R.; van Paassen, A.; Barban, V.; Daré, W.; Gramaglia, C. Learning integrative negotiation to manage complex environmental issues: Example of a gaming approach in the peri-urban catchment of São Paulo, Brazil. Reg. Environ. Change 2015, 15, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. Normative, Gain and Hedonic Goal Frames Guiding Environmental Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cialdini, R. Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corning, A.; Schuman, H. Commemoration matters: The anniversaries of 9/11 and Woodstock. Public Opin. Q. 2013, 77, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, C.D. Not all news is the same: Protests, presidents, and the mass public agenda. Public Opin. Q. 2012, 76, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilovich, T.; Griffin, D.; Kahneman, D. Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment; Cambridge university press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ozesmi, U.; Ozesmi, S. A Participatory Approach to Ecosystem Conservation: Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Stakeholder Group Analysis in Uluabat Lake, Turkey. Environ. Manag. 2003, 31, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Belt, M. Mediated Modeling: A System Dynamics Approach to Environmental Consensus Building; Island press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ. Identity Read. 1979, 56, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Roloff, K.S. Overcoming barriers to collaboration: Psychological safety and learning in diverse teams. In Team Effectiveness in Complex Organizations: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives and Approaches; The Organizational Frontiers Series; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- Janis, I. Groupthink. In A First Look at Communication Theory; Griffin, E., Ed.; McGrawHill: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Smith, D.M. Too Hot to Handle? How to Manage Relationship Conflict. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 49, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aikin, S.F.; Talisse, R.B. Why We Argue (And How We Should): A Guide to Political Disagreement in an Age of Unreason, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.; Shapiro, C.D.; Voinov, A. Records of engagement and decision tracking for adaptive management and policy development. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society (ISTAS), Washington, DC, USA, 13–14 November 2018; pp. 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Borowski, I.; Hare, M. Exploring the Gap Between Water Managers and Researchers: Difficulties of Model-Based Tools to Support Practical Water Management. Water Resour. Manag. 2007, 21, 1049–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, E.J.; Zellner, M.; Jenni, K.E.; Leong, K.; Glynn, P.D.; BenDor, T.K.; Bommel, P.; Hubacek, K.; Jetter, A.J.; Jordan, R.; et al. Try, try again: Lessons learned from success and failure in participatory modeling. Elementa 2019, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnaud, C.; Van Paassen, A. Equity, power games, and legitimacy: Dilemmas of participatory natural resource management. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damer, T.E. Attacking Faulty Reasoning: A Practical Guide to Fallacy-Free Arguments, 6th ed.; Wadsworth Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beers, P.J.; Mierlo, B.; Hoes, A.C. Toward an Integrative Perspective on Social Learning in System Innovation Initiatives. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ernst, A. Research techniques and methodologies to assess social learning in participatory environmental governance. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2019, 23, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Lei, Z. Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewis, M. The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, K.K.; Fisher, K.T.; Dickson, M.E.; Thrush, S.F.; Le Heron, R. Improving ecosystem service frameworks to address wicked problems. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, D.R.; Hearn, M.T.; Uhleman, M.R.; Ivey, A.E. (Eds.) Essential Interviewing: A Programmed Approach to Effective Communication, 7th ed.; Thomson-Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchi, G.M.; Van Hasselt, V.B.; Romano, S.J. Crisis (hostage) negotiation: Current strategies and issues in high-risk conflict resolution. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2005, 10, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, D.C. Intuition Pumps and other Tools for Thinking, 1st ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harinck, F.; De Dreu, C.K.W. Negotiating interests or values and reaching integrative agreements: The importance of time pressure and temporary impasses. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsing, A.L. Becoming a tribal elder, and other green development fantasies. In Transforming the Indonesian Uplands: Marginality, Power and Production; Routledge: London, UK, 1999; pp. 159–202. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of practice: Learning as a social system. Syst. Think. 1998, 9, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prell, C.; Reed, M.; Racin, L.; Hubacek, K. Competing structure, competing views: The role of formal and informal social structures in shaping stakeholder perceptions. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Kraker, J.; Kroeze, C.; Kirschner, P. Computer models as social learning tools in participatory integrated assessment. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2011, 9, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allen, W.; Fenemor, A.; Kilvington, M.; Harmsworth, G.; Young, R.; Deans, N.; Horn, C.; Phillips, C.; Montes de Oca, O.; Ataria, J.; et al. Building collaboration and learning in integrated catchment management: The importance of social process and multiple engagement approaches. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2011, 45, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Günther, D.; Pahl-Wostl, C. Synapses in the network: Learning in governance networks in the context of environmental management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, M.; Cenek, M.; Powell, J.; Trammell, E.J. Mapping the stakeholders: Using social network analysis to increase the legitimacy and transparency of participatory scenario planning. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 31, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimble, R.; Wellard, K. Stakeholder methodologies in natural resource management: A review of principles, contexts, experiences and opportunities. Agric. Syst. 1997, 55, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingers, J. Variety is the spice of life: Combining soft and hard OR/MS methods. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2000, 7, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.; Holwell, S. Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A Practical Guide; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenko, M. Red Team: How to Succeed by Thinking Like the Enemy, 1st ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Red Teaming Handbook; Technical Report vs. 7.0; University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies (UFMCS): Fort Leavenworth, KS, USA, 2015.

- Craig, S. Reflections from a red team leader. Mil. Rev. 2007, 87, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Barnaud, C.; Van Paassen, A.; Trébuil, G.; Promburom, T. Power relations and participatory water management: Lessons from a companion modelling experiment in northern Thailand. In Proceedings of the International Forum on Water and Food, CPWF Challenge Programme of the CGIAR, Vientiane, Laos, 12–17 November 2006; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, V.A.; Harris, J.A.; Russell, J.Y. Tackling Wicked Problems through the Transdisciplinary Imagination; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs, W.N. Taking flight: Dialogue, collective thinking, and organizational learning. Organ. Dyn. 1993, 22, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H. From Homo Economicus to Homo Sapiens. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bransford, J. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fazey, I.; Fazey, J.A.; Fischer, J.; Sherren, K.; Warren, J.; Noss, R.F.; Dovers, S.R. Adaptive capacity and learning to learn as leverage for social—Ecological resilience. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 5, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J. Climate change governance: History, future, and triple-loop learning? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2016, 7, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosey, P.; Visser, M.; Saunders, M.N. The origins and conceptualizations of `triple-loop’ learning: A critical review. Manag. Learn. 2012, 43, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, R.; Elder, L. The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools, 8th ed.; Thinker’s guide library, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J. Learning in a changing world and changing in al learning world: Reflexively fumbling towards sustainability. S. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 24, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K. Frontiers in Group Dynamics: II. Channels of Group Life; Social Planning and Action Research. Hum. Relations 1947, 1, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. Mind, Brain, and Education Science: A Comprehensive Guide to the New Brain-Based Teaching; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Charteris, J.; Smardon, D. Second look—Second think: A fresh look at video to support dialogic feedback in peer coaching. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2013, 39, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey Berger, J.; Atkins, P.W. Mapping complexity of mind: Using the subject-object interview in coaching. Coach. Int. J. Theory, Res. Pract. 2009, 2, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, K.M.; Harrald, J.R. Organizational learning under fire: Theory and practice. Am. Behav. Sci. 1997, 40, 310–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brookfield, S.D. Developing Critical Thinkers: Challenging Adults to Explore Alternative Ways of Thinking and Acting; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Massy, C. Call of the Reed Warbler. A New Agriculture, A New Earth; University of Queensland Press: St. Lucia, QLD, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Empowerment, coercive persuasion and organizational learning: Do they connect? Learn. Organ. 1999, 6, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvini, G.; van Paassen, A.; Ligtenberg, A.; Carrero, G.C.; Bregt, A.K. A role-playing game as a tool to facilitate social learning and collective action towards Climate Smart Agriculture: Lessons learned from Apuí, Brazil. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 63, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, J.M.; Kok, K.; Beers, P.J.; Van Lammeren, R.; Janssen, R. Combining analytic and experiential communication in participatory scenario development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boud, D.; Cressey, P.; Docherty, P. Productive Reflection at Work: Learning for Changing Organizations; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Capelo, C.; Dias, J.F. A feedback learning and mental models perspective on strategic decision making. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2009, 57, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerill, K.; Glynn, P.; Chabay, I.; Farooque, M.; Hämäläinen, R.P.; Miyamoto, B.; McKay, P. Records of engagement and decision making for environmental and socio-ecological challenges. EURO J. Decis. Process. 2019, 7, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.A.; Perez, P.; Measham, T.G.; Kelly, G.J.; D’Aquino, P.; Daniell, K.A.; Dray, A.; Ferrand, N. Evaluating participatory modeling: Developing a framework for cross-case analysis. Environ. Manag. 2009, 44, 1180–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moallemi, E.A.; Zare, F.; Reed, P.M.; Elsawah, S.; Ryan, M.J.; Bryan, B.A. Structuring and evaluating decision support processes to enhance the robustness of complex human—Natural systems. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 123, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smajgl, A.; Ward, J. Evaluating participatory research: Framework, methods and implementation results. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 157, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triste, L.; Vandenabeele, J.; van Winsen, F.; Debruyne, L.; Lauwers, L.; Marchand, F. Exploring participation in a sustainable farming initiative with self-determination theory. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2018, 16, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Przybylski, A.K.; Ryan, R.M. The index of autonomous functioning: Development of a scale of human autonomy. J. Res. Personal. 2012, 46, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.A. The Psychology of Personal Constructs. Volume 1: A Theory of Personality; W.W. Norton and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Burr, V.; King, N.; Butt, T. Personal construct psychology methods for qualitative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2014, 17, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, M.; McKenzie, H. The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2006, 45, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Drawing Valid Meaning from Qualitative Data: Toward a Shared Craft. Educ. Res. 1984, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.J. Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, A.; Andersson, L.; Alkan-Olsson, J.; Arheimer, B. How participatory can participatory modeling be? Degrees of influence of stakeholder and expert perspectives in six dimensions of participatory modeling. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanovich, K.E. Why humans are (sometimes) less rational than other animals: Cognitive complexity and the axioms of rational choice. Think. Reason. 2013, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B. Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 12, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zare, F.; Guillaume, J.H.A.; Jakeman, A.J.; Torabi, O. Reflective communication to improve problem-solving pathways: Key issues illustrated for an integrated environmental modelling case study. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 126, 104645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moallemi, E.A.; Elsawah, S.; Ryan, M.J. Strengthening ‘good’ modelling practices in robust decision support: A reporting guideline for combining multiple model-based methods. Math. Comput. Simul. 2020, 175, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, V.; Berger, U.; DeAngelis, D.L.; Polhill, J.G.; Giske, J.; Railsback, S.F. The ODD protocol: A review and first update. Ecol. Model. 2010, 221, 2760–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Barrier | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Subjectivity and bias | |

| Managing conflict | |

| Dealing with power |

|

| Communication | |

| Consistency |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenny, D.C.; Castilla-Rho, J. No Stakeholder Is an Island: Human Barriers and Enablers in Participatory Environmental Modelling. Land 2022, 11, 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030340

Kenny DC, Castilla-Rho J. No Stakeholder Is an Island: Human Barriers and Enablers in Participatory Environmental Modelling. Land. 2022; 11(3):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030340

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenny, Daniel C., and Juan Castilla-Rho. 2022. "No Stakeholder Is an Island: Human Barriers and Enablers in Participatory Environmental Modelling" Land 11, no. 3: 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030340

APA StyleKenny, D. C., & Castilla-Rho, J. (2022). No Stakeholder Is an Island: Human Barriers and Enablers in Participatory Environmental Modelling. Land, 11(3), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030340