Do Value Orientations and Beliefs Play a Positive Role in Shaping Personal Norms for Urban Green Space Conservation?

Abstract

1. Introduction

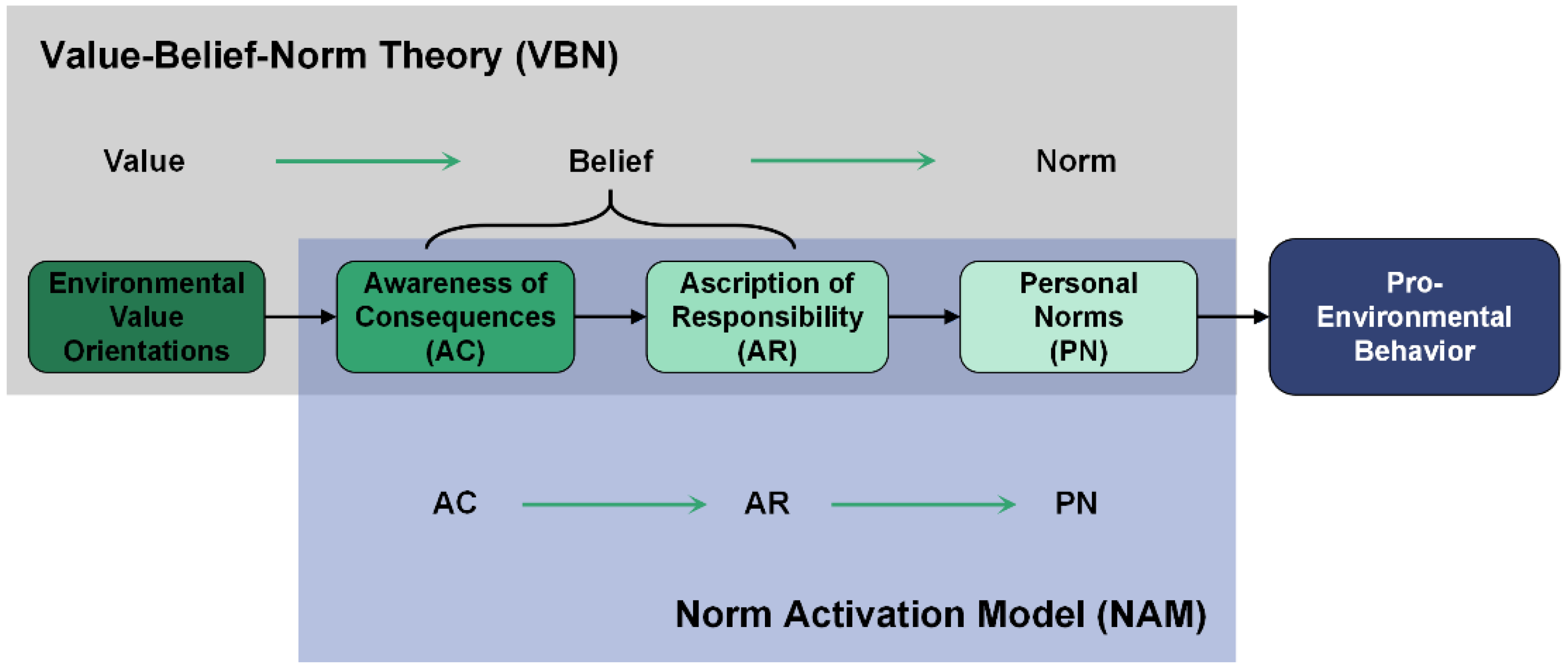

2. Theoretical Background

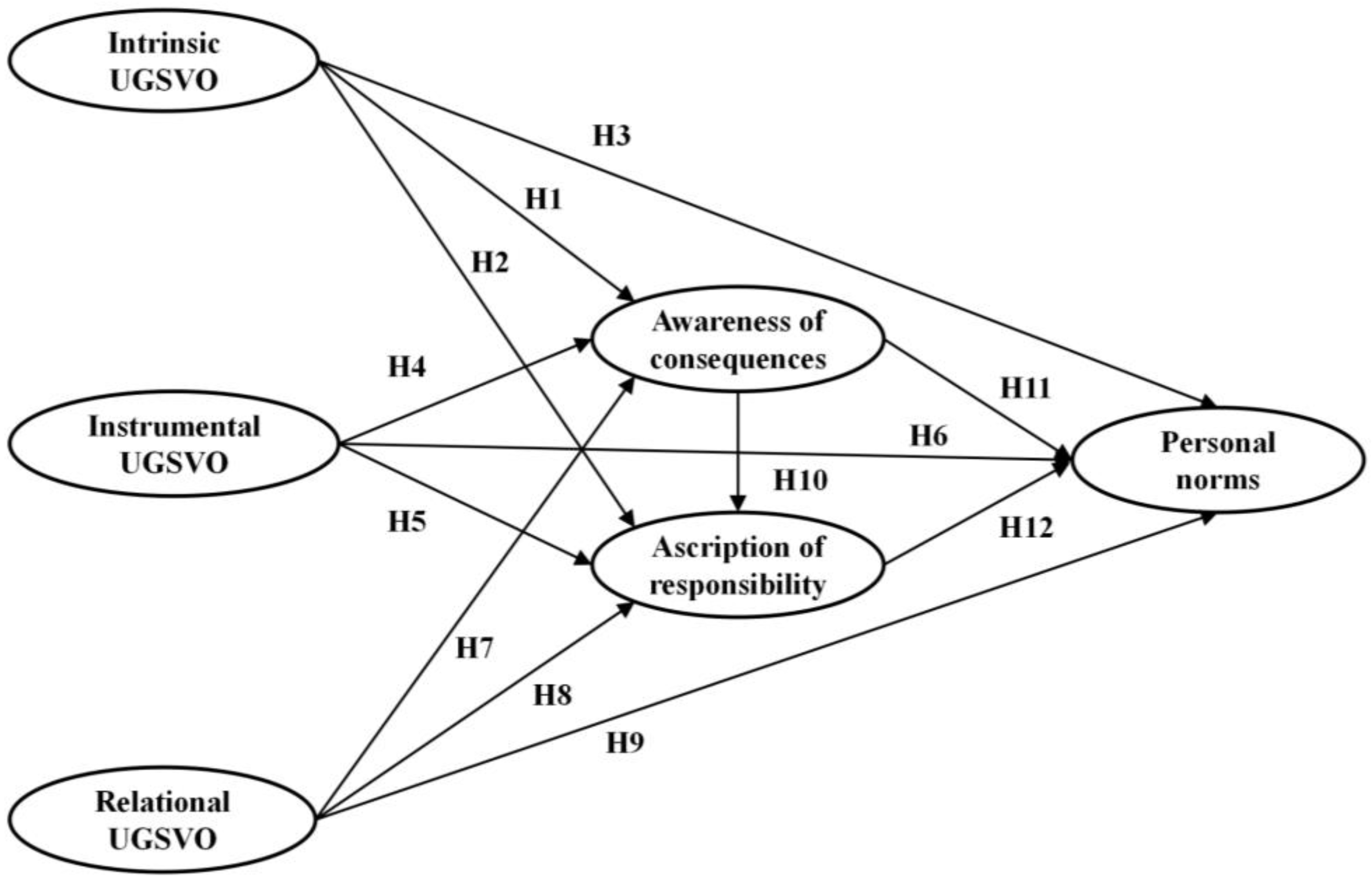

- Intrinsic UGSVO has a significant positive effect on awareness of consequences (H1), ascription of responsibility (H2), personal norms (H3);

- Instrumental UGSVO has a significant positive effect on awareness of consequences (H4), ascription of responsibility (H5), personal norms (H6);

- Relational UGSVO has a significant positive effect on awareness of consequences (H7), ascription of responsibility (H8), personal norms (H9);

- Awareness of consequences has a significant positive effect on ascription of responsibility (H10), personal norms (H11);

- Ascription of responsibility has a significant positive effect on personal norms (H12).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Survey Implementation and Sample Description

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

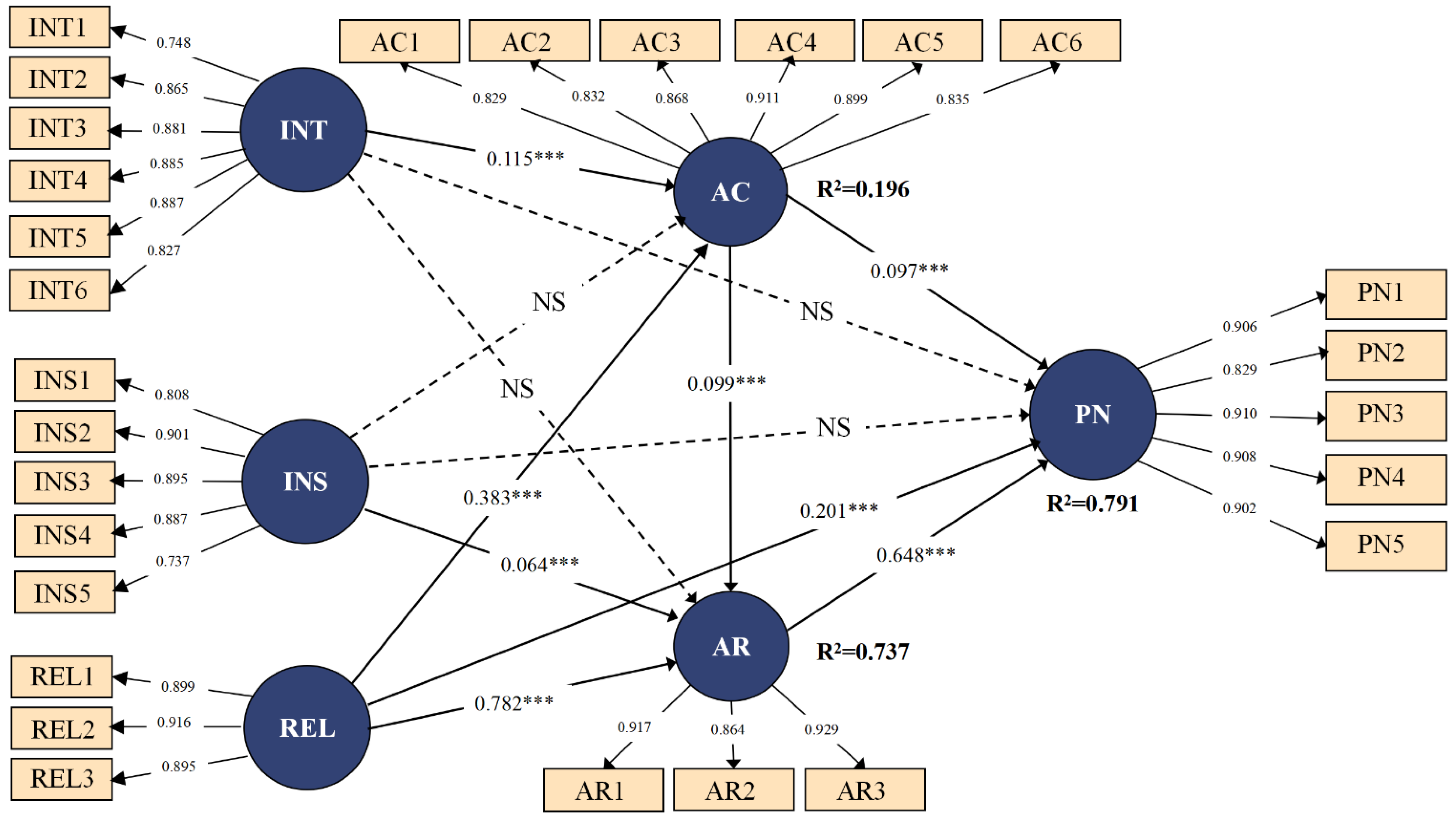

4.1. Evaluation of the Measurement Models

4.2. Evaluation of Structural Models: Measures of Fit

4.3. Research Hypothesis Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schneider, P.; Walz, A.; Albert, C.; Lipp, T. Ecosystem-based adaptation in cities: Use of formal and informal planning instruments. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, P.; Casanelles-Abella, J.; Luz, A.C.; Kubicka, A.M.; Branquinho, C.; Laanisto, L.; Neuenkamp, L.; Alós Ortí, M.; Obrist, M.K.; Deguines, N.; et al. Research agenda on biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services in European cities. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2021, 53, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, A.; Watkiss, P. Climate change impacts and adaptation in cities: A review of the literature. Clim. Chang. 2011, 104, 13–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.F.; Marengo, J.A.; Martins Coelho, J.O.; Scofield, G.B.; de Oliveira Silva, C.C.; Prieto, C.C. The role of nature-based solutions in disaster risk reduction: The decision maker’s perspectives on urban resilience in São Paulo state. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 39, 101219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen Zari, M.; Blaschke, P.M.; Jackson, B.; Komugabe-Dixson, A.; Livesey, C.; Loubser, D.I.; Martinez-Almoyna Gual, C.; Maxwell, D.; Rastandeh, A.; Renwick, J.; et al. Devising urban ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) projects with developing nations: A case study of Port Vila, Vanuatu. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 184, 105037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthers, S.; Laschewski, G.; Matzarakis, A. The Summers 2003 and 2015 in South-West Germany: Heat Waves and Heat-Related Mortality in the Context of Climate Change. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.; Günnemann, S.; Disse, M. Spatiotemporal analysis of heavy rain-induced flood occurrences in Germany using a novel event database approach. J. Hydrol. 2021, 595, 125985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Zheng, D.; Li, S. Perceptions of ecosystem services, disservices and willingness-to-pay for urban green space conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 110140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sun, S.; Liu, W.; Garcia, E.H.; He, L.; Cai, Q.; Xu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J. The cooling and energy saving effect of landscape design parameters of urban park in summer: A case of Beijing, China. Energy Build. 2017, 149, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, S.; Sun, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Lao, Z.; Guo, G.; Smith, K.; Cui, Y.; Liu, W.; et al. Evaluation of Energy Saving Potential of an Urban Green Space and its Water Bodies. Energy Build. 2019, 188–189, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaggio, M. The value of public urban green spaces: Measuring the effects of proximity to and size of urban green spaces on housing market values in San José, Costa Rica. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Kim, K.-H. Attitudes of Citizens towards Urban Parks and Green Spaces for Urban Sustainability: The Case of Gyeongsan City, Republic of Korea. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8240–8254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, P.J.; Jensen, R.R. The effect of urban leaf area on summertime urban surface kinetic temperatures: A Terre Haute case study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, K.R.; Wells, M.J.; Kershaw, T. Utilising green and bluespace to mitigate urban heat island intensity. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Wagner, J.E.; Nowak, D.J.; De la Maza, C.L.; Rodriguez, M.; Crane, D.E. Analyzing the cost effectiveness of Santiago, Chile’s policy of using urban forests to improve air quality. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 86, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, P.; Vieira, J.; Rocha, B.; Branquinho, C.; Pinho, P. Modeling the provision of air-quality regulation ecosystem service provided by urban green spaces using lichens as ecological indicators. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 665, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, T.K.; Zhe Han, S.S.; Lechner, A.M. Urban green space and well-being in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 36, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhao, S. Valuing urban green spaces in mitigating climate change: A city-wide estimate of aboveground carbon stored in urban green spaces of China’s Capital. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2019, 25, 1717–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngulani, T.; Shackleton, C.M. Use of public urban green spaces for spiritual services in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnan, S.E.; Jorgensen, A.; Tsuchiya, A.; Goyder, L.; Woods, H.B. PHP58 Towards Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Urban Green Space: A Mapping Review. Value Health 2011, 14, A343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Benton, J.S.; Cotterill, S.; Anderson, J.; Macintyre, V.G.; Gittins, M.; Dennis, M.; Lindley, S.J.; French, D.P. Impact of a low-cost urban green space intervention on wellbeing behaviours in older adults: A natural experimental study. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, N.; Tian, J.; Chen, L. Uncovering the willingness-to-pay for urban green space conservation: A survey of the capital area in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, S. Values at sea, value of the sea: Mapping issues and divides. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2007, 46, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abass, K.; Appiah, D.O.; Afriyie, K. Does green space matter? Public knowledge and attitude towards urban greenery in Ghana. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q. Encouraging the use of urban green space: The mediating role of attitude, perceived usefulness and perceived behavioural control. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Schio, N.; Phillips, A.; Fransen, K.; Wolff, M.; Haase, D.; Ostoić, S.K.; Živojinović, I.; Vuletić, D.; Derks, J.; Davies, C.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of and attitudes towards urban forests and green spaces: Exploring the instigators of change in Belgium. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.A.; Shaw, S.; Ross, H.; Witt, K.; Pinner, B. The study of human values in understanding and managing social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetas, E.R.; Yasué, M. A systematic review of motivational values and conservation success in and around protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansong, M.; Røskaft, E. Determinants of attitudes of primary stakeholders towards forest conservation management: A case study of Subri Forest Reserve, Ghana. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2011, 7, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Thøgersen, J. Values and Pro-Environmental Behaviour. In Environmental Psychology; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ihemezie, E.J.; Nawrath, M.; Strauß, L.; Stringer, L.C.; Dallimer, M. The influence of human values on attitudes and behaviours towards forest conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 292, 112857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ives, C.D.; Kendal, D. The role of social values in the management of ecological systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Mean or green: Which values can promote stable pro-environmental behavior? Conserv. Lett. 2009, 2, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monical, A.; Jerryj, V.; Alistair, J.B. Value orientations and beliefs contribute to the formation of a marine conservation personal norm. J. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 55, 125806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. A normative decision-making model of altruism. In Altruism and Helping Behavior; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, J.P.; Sorrentino, R.M. Altruism and Helping Behavior: An Historical Perspective. In Altruism and Helping Behavior. Social, Personality, and Developmental Perspectives; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sugandini, D.; Rahatmawati, I.; Arundati, R. Environmental Attitude on the Adoption Decision Mangrove Conservation: An Empirical Study on Communities in Special Region of Yogyakarta, Indonesia; Social Science Electronic Publishing: Hong Kong, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa Karki, S.; Hubacek, K. Developing a conceptual framework for the attitude–intention–behaviour links driving illegal resource extraction in Bardia National Park, Nepal. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 117, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Fitzgerald, A.; Shwom, R. Environmental Values. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 335–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism11This work was supported by NSF Grant SOC 72-05417. I am indebted to L. Berkowitz, R. Dienstbier, H. Schuman, R. Simmons, and R. Tessler for their thoughtful comments on an early draft of this chapter. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, H.; Davis, S.M. Matching corporate culture and business strategy. Organ. Dyn. 1981, 10, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, J.; Carraresi, L.; Bröring, S. Do pro-environmental values, beliefs and norms drive farmers’ interest in novel practices fostering the Bioeconomy? J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Molinario, E.; Scopelliti, M.; Bonnes, M.; Bonaiuto, F.; Cicero, L.; Admiraal, J.; Beringer, A.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; de Groot, W.; et al. The extended Value-Belief-Norm theory predicts committed action for nature and biodiversity in Europe. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 81, 106338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynveen, C.J.; Wynveen, B.J.; Sutton, S.G. Applying the Value-Belief-Norm Theory to Marine Contexts: Implications for Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behavior. Coast. Manag. 2015, 43, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Balvanera, P.; Benessaiah, K.; Chapman, M.; Díaz, S.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Gould, R.; Hannahs, N.; Jax, K.; Klain, S.; et al. Opinion: Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klain, S.C.; Olmsted, P.; Chan, K.M.A.; Satterfield, T. Relational values resonate broadly and differently than intrinsic or instrumental values, or the New Ecological Paradigm. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallis, H.; Lubchenco, J. Working together: A call for inclusive conservation. Nature 2014, 515, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Díaz, S.; Pataki, G.; Roth, E.; Stenseke, M.; Watson, R.T.; Başak Dessane, E.; Islar, M.; Kelemen, E.; et al. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: The IPBES approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz-Vietta, N.V.M. What can forest values tell us about human well-being? Insights from two biosphere reserves in Madagascar. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.G. Ethical pluralism, pragmatism, and sustainability in conservation practice. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Pascual, U. A typology of elementary forms of human-nature relations: A contribution to the valuation debate. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 35, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Roth, R.; Klain, S.C.; Chan, K.; Christie, P.; Clark, D.A.; Cullman, G.; Curran, D.; Durbin, T.J.; Epstein, G.; et al. Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 205, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.; Haider, L.J.; Masterson, V.; Enqvist, J.P.; Svedin, U.; Tengö, M. Stewardship, care and relational values. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 35, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucetich, J.A.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Nelson, M.P. Evaluating whether nature’s intrinsic value is an axiom of or anathema to conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ives, C.D.; Oke, C.; Hehir, A.; Gordon, A.; Wang, Y.; Bekessy, S.A. Capturing residents’ values for urban green space: Mapping, analysis and guidance for practice. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 161, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diluiso, F.; Guastella, G.; Pareglio, S. Changes in urban green spaces’ value perception: A meta-analytic benefit transfer function for European cities. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory McPherson, E. Accounting for benefits and costs of urban greenspace. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1992, 22, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoulia, I.; Santamouris, M.; Dimoudi, A. Monitoring the effect of urban green areas on the heat island in Athens. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 156, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, S.; Ohta, T. Seasonal variations in the cooling effect of urban green areas on surrounding urban areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdie, D.R. Reassessing the Value of High Response Rates to Mail Surveys. Mark. Res. 1989, 1, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Karpudewan, M. The relationships between values, belief, personal norms, and climate conserving behaviors of Malaysian primary school students. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.F.; Cepeda, G.; Roldán, J.L.; Ringle, C.M. European management research using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sarkar, A.; Qian, L. Evaluations of the Roles of Organizational Support, Organizational Norms and Organizational Learning for Adopting Environmentally Friendly Technologies: A Case of Kiwifruit Farmers’ Cooperatives of Meixian, China. Land 2021, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, C.; Hackl, P.; Westlund, A.H. Robustness of partial least-squares method for estimating latent variable quality structures. J. Appl. Stat. 1999, 26, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle Christian, M.; Sven, W.; Jan-Michael, B. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH: Bönningstedt, Germany, 25. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leguina, A. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.X.; Lai, F. Using partial least squares in operations management research: A practical guideline and summary of past research. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; van Oppen, C. Using PLS Path Modeling for Assessing Hierarchical Construct Models: Guidelines and Empirical Illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.; Duckitt, J. The Environmental Attitudes Inventory: A valid and reliable measure to assess the structure of environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior: How to Measure Egoistic, Altruistic, and Biospheric Value Orientations. Environ. Behav. 2007, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batavia, C.; Nelson, M.P. For goodness sake! What is intrinsic value and why should we care? Biol. Conserv. 2017, 209, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickenbach, O.; Reyes-García, V.; Moser, G.; García, C. What Explains Wildlife Value Orientations? A Study among Central African Forest Dwellers. Hum. Ecol. 2017, 45, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Notaro, S.; Campbell, D. Including Value Orientations in Choice Models to Estimate Benefits of Wildlife Management Policies. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 151, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Items | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic UGSVO (INT) | INT1 | Providing space for wildlife/biogenetic conservation |

| INT2 | Carbon sequestration and oxygen release to regulate microclimate | |

| INT3 | Purifies air, water, and soil | |

| INT4 | Conserve soil and water | |

| INT5 | Alleviating the urban heat island effect | |

| INT6 | Maintaining urban ecosystem stability | |

| Instrumental UGSVO (INS) | INS1 | In UGS, people can exercise, reduce disease, and save medical costs |

| INS2 | In UGS, people can get aesthetic enjoyment and keep a happy mind | |

| INS3 | In UGS, people can reduce work and life stress and relieve anxiety | |

| INS4 | In UGS, people can have the opportunity to become closer to nature and improve their knowledge of biodiversity | |

| INS5 | UGS beautifies the living environment | |

| Relational UGSVO—Care (REL) | REL1 | I am concerned about the current status of UGS |

| REL2 | I care about the future development and changes of UGS | |

| REL3 | I am concerned about how I feel in UGS | |

| Awareness of Consequences (AC) | AC1 | The health of UGS is at risk |

| AC2 | Rapid urbanization will reduce UGS | |

| AC3 | The destruction of UGS will upset the balance of urban ecosystems | |

| AC4 | The destruction of UGS will reduce air quality | |

| AC5 | The destruction of UGS will cause problems for member of society | |

| AC6 | Urban areas will face a serious ecological crisis in the future | |

| Ascription of Responsibility (AR) | AR1 | It is my responsibility to conserve UGS |

| AR2 | Even if I don’t usually go to UGS, I feel I have a responsibility to conserve them | |

| AR3 | Every person in the social group should be responsible for the conservation of UGS | |

| Personal Norm (PN) | PN1 | I think I should actively participate in the conservation of UGS |

| PN2 | Even without government support, I think I should be actively involved in the conservation of UGS | |

| PN3 | Even if it costs more money and time, I want to do what is good for UGS | |

| PN4 | I feel guilty when I do nothing for UGS conservation | |

| PN5 | I think I should support the government to introduce policies and projects to conserve UGS |

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 770 | 46.9% |

| Female | 871 | 53.1% | |

| Age | ≤17 | 77 | 4.7% |

| 18–29 | 415 | 25.3% | |

| 30–39 | 490 | 29.9% | |

| 40–49 | 248 | 15.1% | |

| 50–59 | 199 | 12.1% | |

| ≥60 | 212 | 12.9% | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 660 | 40.2% |

| Married | 981 | 59.8% | |

| Education level | Primary school and below | 55 | 3.4% |

| Junior high school | 248 | 15.1% | |

| High school | 498 | 30.3% | |

| Undergraduate | 601 | 36.6% | |

| Master’s degree or above | 239 | 14.6% | |

| Health condition | Very bad | 8 | 0.5% |

| Relatively poor | 52 | 3.2% | |

| Commonly | 504 | 30.7% | |

| Better | 765 | 46.6% | |

| Very nice | 312 | 19.0% |

| Indicator | Factor Loading | VIF | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic UGSVO | 0.923 | 0.940 | 0.723 | ||

| INT1 | 0.748 | 2.004 | |||

| INT2 | 0.865 | 3.458 | |||

| INT3 | 0.881 | 3.558 | |||

| INT4 | 0.885 | 3.200 | |||

| INT5 | 0.887 | 3.449 | |||

| INT6 | 0.827 | 2.436 | |||

| Instrumental UGSVO | 0.901 | 0.927 | 0.719 | ||

| INS1 | 0.808 | 2.161 | |||

| INS2 | 0.901 | 3.297 | |||

| INS3 | 0.895 | 3.268 | |||

| INS4 | 0.887 | 2.894 | |||

| INS5 | 0.737 | 1.712 | |||

| Relational UGSVO—Care | 0.887 | 0.930 | 0.816 | ||

| REL1 | 0.899 | 2.539 | |||

| REL2 | 0.916 | 2.807 | |||

| REL3 | 0.895 | 2.404 | |||

| Awareness of Consequences | 0.931 | 0.946 | 0.745 | ||

| AC1 | 0.829 | 2.462 | |||

| AC2 | 0.832 | 2.486 | |||

| AC3 | 0.868 | 2.892 | |||

| AC4 | 0.911 | 4.506 | |||

| AC5 | 0.899 | 4.428 | |||

| AC6 | 0.835 | 2.769 | |||

| Ascription of Responsibility | 0.888 | 0.930 | 0.817 | ||

| AR1 | 0.917 | 2.992 | |||

| AR2 | 0.864 | 2.102 | |||

| AR3 | 0.929 | 3.272 | |||

| Personal Norm | 0.935 | 0.951 | 0.795 | ||

| PN1 | 0.906 | 3.501 | |||

| PN2 | 0.829 | 2.311 | |||

| PN3 | 0.910 | 3.721 | |||

| PN4 | 0.908 | 4.398 | |||

| PN5 | 0.902 | 4.327 |

| INT | INS | REL | AC | AR | PN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT | 0.850 | |||||

| INS | 0.451 | 0.848 | ||||

| REL | 0.258 | 0.311 | 0.903 | |||

| AC | 0.231 | 0.208 | 0.424 | 0.863 | ||

| AR | 0.277 | 0.338 | 0.850 | 0.449 | 0.904 | |

| PN | 0.289 | 0.331 | 0.806 | 0.483 | 0.876 | 0.892 |

| Communality | R² | Q2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| INT | 0.723 | ||

| INS | 0.719 | ||

| REL | 0.816 | ||

| AC | 0.745 | 0.196 | 0.162 |

| AR | 0.817 | 0.737 | 0.592 |

| PN | 0.795 | 0.791 | 0.530 |

| Goodness of Fit (GoF) | 0.642 | ||

| Hypothesis | Path | β | t Value | p | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | INT→AC | 0.115 | 4.339 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | INT→AR | 0.023 | 1.470 | 0.142 | Unsupported |

| H3 | INT→PN | 0.028 | 1.802 | 0.072 | Unsupported |

| H4 | INS→AC | 0.037 | 1.325 | 0.185 | Unsupported |

| H5 | INS→AR | 0.064 | 4.328 | *** | Supported |

| H6 | INS→PN | 0.017 | 1.157 | 0.247 | Unsupported |

| H7 | REL→AC | 0.383 | 12.728 | *** | Supported |

| H8 | REL→AR | 0.782 | 42.727 | *** | Supported |

| H9 | REL→PN | 0.201 | 6.025 | *** | Supported |

| H10 | AC→AR | 0.099 | 5.726 | *** | Supported |

| H11 | AC→PN | 0.097 | 5.540 | *** | Supported |

| H12 | AR→PN | 0.648 | 19.182 | *** | Supported |

| Path | β | t Value | p | Bias-Corrected and Accelerated Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.50% | 97.50% | ||||

| Specific Indirect Effects | |||||

| AC→AR→PN | 0.064 | 5.34 | *** | 0.042 | 0.088 |

| INS→AC→AR | 0.004 | 1.259 | 0.208 | −0.002 | 0.01 |

| INS→AC→AR→PN | 0.002 | 1.249 | 0.212 | −0.001 | 0.006 |

| INS→AC→PN | 0.004 | 1.244 | 0.213 | −0.002 | 0.010 |

| INS→AR→PN | 0.042 | 4.161 | *** | 0.023 | 0.062 |

| INT→AC→AR | 0.011 | 3.432 | ** | 0.006 | 0.019 |

| INT→AC→AR→PN | 0.007 | 3.284 | ** | 0.004 | 0.012 |

| INT→AC→PN | 0.011 | 3.529 | *** | 0.006 | 0.018 |

| INT→AR→PN | 0.015 | 1.46 | 0.144 | −0.005 | 0.035 |

| REL→AC→AR | 0.038 | 4.727 | *** | 0.024 | 0.055 |

| REL→AC→AR→PN | 0.024 | 4.514 | *** | 0.015 | 0.036 |

| REL→AC→PN | 0.037 | 4.805 | *** | 0.023 | 0.052 |

| REL→AR→PN | 0.507 | 17.731 | *** | 0.450 | 0.562 |

| Total Effects | |||||

| AC→AR | 0.099 | 5.726 | *** | 0.066 | 0.135 |

| AC→PN | 0.161 | 7.714 | *** | 0.121 | 0.203 |

| AR→PN | 0.648 | 19.182 | *** | 0.581 | 0.711 |

| INS→AC | 0.037 | 1.325 | 0.185 | −0.016 | 0.091 |

| INS→AR | 0.068 | 4.553 | *** | 0.039 | 0.098 |

| INS→PN | 0.064 | 3.522 | *** | 0.029 | 0.101 |

| INT→AC | 0.115 | 4.339 | *** | 0.065 | 0.17 |

| INT→AR | 0.034 | 2.227 | * | 0.003 | 0.065 |

| INT→PN | 0.061 | 3.133 | ** | 0.023 | 0.100 |

| REL→AC | 0.383 | 12.728 | *** | 0.324 | 0.444 |

| REL→AR | 0.820 | 55.241 | *** | 0.790 | 0.848 |

| REL→PN | 0.770 | 41.12 | *** | 0.732 | 0.806 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, K.; Ren, J.; Cui, C.; Hou, Y.; Wen, Y. Do Value Orientations and Beliefs Play a Positive Role in Shaping Personal Norms for Urban Green Space Conservation? Land 2022, 11, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020262

Su K, Ren J, Cui C, Hou Y, Wen Y. Do Value Orientations and Beliefs Play a Positive Role in Shaping Personal Norms for Urban Green Space Conservation? Land. 2022; 11(2):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020262

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Kaiwen, Jie Ren, Chuyun Cui, Yilei Hou, and Yali Wen. 2022. "Do Value Orientations and Beliefs Play a Positive Role in Shaping Personal Norms for Urban Green Space Conservation?" Land 11, no. 2: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020262

APA StyleSu, K., Ren, J., Cui, C., Hou, Y., & Wen, Y. (2022). Do Value Orientations and Beliefs Play a Positive Role in Shaping Personal Norms for Urban Green Space Conservation? Land, 11(2), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020262