Abstract

Hail is regarded as one of the richest cities in Saudi Arabia in terms of heritage sites. The city center, where the Barzan marketplace is located, is regarded as critical to the city’s cultural tourism. The purpose of this study is to understand the traditional Barzan market rehabilitation project within the city center and its role in preserving Hail’s urban identity. According to the study, the rehabilitation of the city center presents an opportunity for urban development to boost tourism and connect various historic landmarks in a variety of ways, including the development of pedestrian routes. The study also presents and discusses several complexities and challenges that must be considered when implementing such an urban development. A multi-approach methodology is employed to investigate several urban factors and involved actors, including a social online survey and semi-structured interviews, as well as empirical data to support the study objectives. The study’s findings indicate that there is an issue with the urban solution implemented in the Barzan market on multiple levels, the most important of which is the ‘miso’ level of the city center, where several potential landmarks are neglected and isolated from the Barzan marketplace. A solution is proposed to create multiple urban spaces that can be used by the Hail community as a whole, not just those involved in the market. This would necessitate a different approach to space design, as well as changes in how the Barzan market is managed and maintained.

Keywords:

cultural tourism; city center; urbanism; heritage; Barzan; Saudi Arabia; Hail City; pedestrian; historic landmark; thermal comfort 1. Introduction

There has been a revival of interest in urban tourism since the early 1980s [1,2], resulting in a significant increase in this type of travel. Several interrelated factors have played a role in this process, including the need to breathe new life into and rehabilitate town and city centers, the need for a broader range of cultural pursuits [3,4], consumers’ interest in heritage and urban development, as well as their search for things to do and places to spend money in these areas. The introduction of the single market, as well as the overall rise in mobility, have all contributed to the growth of urban tourism.

The desire of visitors for a wider range of activities and leisure pursuits is leading to an expansion of what is now available [5]. Tourism is gaining favor among policymakers, who are increasingly interested in promoting it as an important component of economic growth that generates income and job opportunities. While tourism does not contribute significantly to the city’s economy, it does provide recreational and well-being opportunities for all residents. It is a growing activity that helps to improve and market the city’s image as a desirable place to live and visit [6]. Tourism also creates jobs and money while expanding the range of available social services. It caters to a wide range of tourists, including those on vacation, as well as day trips and business trips to the city. To establish a tourism industry, a competitive supply that can meet tourists’ expectations is combined with a beneficial contribution to the development of towns and cities, as well as the well-being of their people.

The relationship between a historic site and the community is influenced by the site’s physical location. Many historic structures are located in and around city centers, where people interact with their environment and practice their lives. According to Norwegian research, every krona invested in asset restoration and maintenance returns ten krona to society, and each heritage-related job creates 26.7 related jobs [7]. According to comparable research conducted in Spain, the ratio of total cultural tourist consumption to effort in heritage conservation is 26, which is a good indicator of the return on investment generated by cultural assets [8].

Additionally, it is a sector that readily produces jobs; the cost of generating a job in the mainstream business environment (tourism is a business) is projected to be eight to one that of creating a position in tourism [9]. As a result, tourism has established itself as a significant economic activity, generating revenue and jobs in most cities. Cultural tourism, according to ICOMOS, may support the protection and preservation of historic sites, encourage commercial activity, and promote the upkeep of municipal amenities [10]. Furthermore, tourism may assist in raising awareness about heritage protection and preservation by reigniting people’s interest in their culture, boost the city’s image, and foster a stronger feeling of identity and well-being within the community [11].

It is for these reasons that, rather than focusing solely on one of these issues, most international cities’ urban redevelopment efforts seek to address both economic growth and urban development issues concurrently [12]. Among the ways cities accomplish this is by providing unforgettable and unique experiences for tourists, as well as by making every effort to meet residents’ legitimate expectations for environmentally conscious, harmonious economic and social growth.

There is a consensus in Saudi Arabia that urban development is one of the most important economic tools. As a result, a new program called ‘Downtown’ was announced to improve the quality of city center urban life in twelve Saudi cities, including Hail [13]. Moreover, Hail has remarkable cultural heritage sites and various tourist destinations, which promote the city as one of the most diverse cultural tourism destinations in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [14]. However, this study frames its statement problem as a tool with cultural and social risks, implying that urbanization cannot be treated solely as an economic commodity while ignoring its cultural and social impact. We believe that thinking about the existing urban fabric and its cultural and social components is one of the conditions for successful urbanization development and that any new development should enhance and support the existing fabric rather than challenge it. As a result, careful handling of the hidden aspects of urbanization and accounting for them in the economic balance should form the conceptual foundation of any new urban project. This study proposes sustainable urban development as a tool for promoting cultural tourism in historic city centers and, thus, as a driving force in the city of Hail’s uplifting urban development.

In the case of Barzan, the historic market could serve as a starting point for such a program in Hail. As a result, the purpose of this research is to gain a better understanding of the traditional Barzan market rehabilitation project within a broader framework, namely the city center, and the desired function of this center in preserving Hail’s urban identity. This study will shed light on the relationship between the marketplace and other historical sites in the city center, as well as attempt to comprehend: (1) the market potential of Barzan, (2) the anticipated effects of the rehabilitation process on cultural tourism in the city, (3) the dynamics of Hail’s city center urban development, and (4) the possibility of Barzan becoming a cultural tourism attraction.

2. Literature Review

This section aims to review a variety of historic site issues that bring cultural tourism and urban regeneration to cities in order to promote city centers. This section’s final remarks aim to highlight a theoretical framework in which cultural tourism is seen as a driving force for urban regeneration in city centers. It is also an attempt to develop a conceptual framework and promote a methodological framework for investigating the potential of cultural tourism and urban regeneration to revitalize city centers around the world.

The review is divided into three sections: cultural and heritage tourism, heritage-led regeneration, and cultural tourism as a catalyst for urban renewal in city centers.

2.1. Cultural and Heritage Tourism in the Context of Sustainability

According to Boniface and Fowler (1993), tourism is rapidly becoming the world’s largest industry. However, heritage is the backbone of that industry, and in many cases, the two concepts become inseparable [15]. Historic monuments serve as evidence of past civilizations or historic events, which are becoming increasingly important in cultural tourism. The monuments in the space serve as historical reminders. The increase in prominence of heritage conservation groups and renewed interest in cultural assets is what motivates the growing number of people involved in cultural associations, international organizations, and investors interested in heritage [16].

Urban cultural tourism is a global phenomenon that has piqued the interest of academics in fields such as tourism management, urbanism, and anthropology. Cultural tourism, according to Harvey (1989) [17], Urry (1990) [18], and Richards (1996) [19], emerged during the transition from modernity to postmodernity, signaling the end of the separation between culture, economics, and tourism, as well as influencing the conflict between globalization and local identity. The city becomes the breeding ground for all of these phenomena, and it is no longer just a place to live and work; it is also a place for recreation and entertainment. In this context, the city transforms into a consumption hub focused on entertainment and tourism. The urban environment is a product that can be purchased by both investors and individual customers [20]. According to this paradigm, any location has the potential to become a tourist destination.

Cultural and heritage tourism are important phenomena, and there is growing interest and demand for cultural tourism issues, development, and management that emphasize the relationship between historic sites and tourism [21,22,23,24]. Furthermore, cultural tourism represents the connection between tourism and heritage management [24,25,26,27]. Furthermore, historic towns and centers can be viewed and encapsulated as tourist destinations and a significant dimension to both authorities and local communities, bringing economic benefits to both [3]. Similarly, Ashworth and Tunbridge (2001) defined historic cities as tourist–historic cities, where tourism as an economic factor plays an important role in the economic production process of historic places. As a result, the uses of tourist–historic sites, users of tourist–historic sites, heritage planning and management, and marketing are all important aspects of the historic sites and tourism nexus [28].

Cultural heritage, according to McKercher and Du Cros (2002) [24], encompasses many aspects, including how tourism works, marketing, assessment, interpretation, and branding of heritage assets. When destinations are historically significant, tourism and travel visits gain significance [29]. Tourism and visitor experiences are important factors driving the high demand for heritage sites. Understanding tourists’ and visitors’ experiences in heritage sites improves understanding of the heritage tourism dimension of these sites [30]. In heritage sites, visitor experience is becoming a modern market consumption, inextricably linked to the development process [29]. Tourist behavior and visitation patterns are important components of heritage tourism, and they play an important role in more effectively managing heritage sites [31].

The debate over conservation, tourism, and sustainability is heating up. Various initiatives have sparked discussion about the opportunities and constraints surrounding historic towns, tourism, and sustainable approaches [28,32,33,34]. Cultural tourism generates significant economic revenue; however, if a sustainable approach is not taken, it may result in congestion, a decrease in quality of life, and a loss of local identity [35]. The relationship between tourism and concepts of culture or heritage is tense. To avoid the negative impact of tourism, it is necessary to harness heritage management and effectively implement sustainable measures. Collaboration among different stakeholders is achieved, and conflict is avoided, as long as tourism goals are compatible with the heritage management agenda [24]. Sustainable tourism emphasizes a number of issues, including local community and economic benefits [36].

2.2. Culture-Led Urban Regeneration

Several studies have been conducted that incorporate heritage into the urban regeneration agenda and strategy (e.g., see [37,38,39,40,41,42]). Urban tourism is a process that highlights many opportunities and constraints associated with the management and development of urban destinations [43]. Furthermore, urban regeneration is becoming a current issue in cultural tourism, and the two concepts are interconnected [44]. Furthermore, cultural tourism is important for the development of cities. According to Smith (2009), a more interactive approach involving different types of activities, people, location, interpretation, and technologies encourages creative cultural tourism [45].

Heritage management and planning necessitate a compromise between three major aspects: conservation, tourism, and sustainable development. According to Nasser (2003), the relationship between tourism and heritage sites is important in managing and planning historic environments; however, planning for sustainability that considers the local community and cultural goals is essential [46]. However, urbanization may have an impact on the city’s historic districts. To compete with the process of urbanization, the cultural heritage values of a city’s historic sites that are under urban pressure is subject to be rethought and reevaluated [47].

2.3. Promoting Cultural Tourism in the City Centre: An Opportunity for Urban Regeneration

Historic urban quarters and centers can benefit from urban design and urban regeneration. Through cultural dimensions, these approaches promote the sense of place and identity of urban quarters and city centers [48]. Tiesdell et al. (1996) argue that urban quarters are an important part of a city’s image and identity. However, addressing issues of obsolescence, resources, and opportunities, as well as managing the physical, social, and economic aspects of urban revitalization, are crucial [48]. Furthermore, tourism and culture can play an important role in revitalizing and regenerating urban areas. On the one hand, the destination, image, and place-making of urban centers are critical elements in promoting city centers. Management, economic, and tourism strategies, on the other hand, are critical tools for revitalizing city centers. Equally important is to utilize investment as a valuable tool to promote economic, social, and cultural aspects of historic sites in a sustainable manner [49].

In particular, tourist destination image (TDI) has gained attention on multiple urban and tourism levels [50,51]. Several studies addressed the concept of destination image and its scientific discussion [50,52,53,54]. It is a significant concept because it creates a tentative representation in the mind of potential visitors [55], which can be in the form of beliefs, ideas, and impressions [56]. Destination image can be viewed from two perspectives: projected images, which are agents that provide available ideas for tourists, and perceived images, which are a more subjective idea formed by tourists [6,57,58]. The formation of a destination image relies on three folds of agents: destination promoters, transmitted between individuals, and emanating from autonomous sources [59,60]. Cultural heritage in urban areas, on the other hand, plays an important role in development of a tourist destination. A positive cultural heritage image is crucial in attracting tourists and creating a thriving destination [61]. According to Federico Lenzerini (2011), intangible cultural heritage, ICH, has the inherent ability to modify and shape its own characteristics in parallel with the cultural evolution of the communities involved and is thus capable of representing their living heritage at any time [62]. Therefore, elements of tangible and intangible cultural heritage in the city strengthen the attractiveness of its destination image [63].

Spirou (2011) places tourism within the context of the urban process. The economic aspect of tourism is an important part of the physical development of cities. However, negative social and environmental consequences are unavoidable. Although urban tourism incorporates economic, social, and environmental change processes that lead to city development, management and sustainable measures are equally important. Downtown revitalization with a tourism agenda is changing the face of downtowns and city centers [1].

The changing process of urban heritage areas is avoidable, and city development necessitates the inclusion of tourism and heritage management in the urban change agenda and strategy. Adaptation and alignment with the changing role of cities’ urban development are required for cultural tourism and urban heritage management. However, sustainable tools and approaches to urban development are required [64]. To balance the needs of these aspects and the needs of local communities in the management process, historic centers require urban regeneration actions that include tourism, economic benefits, and sustainability [65].

This section integrates cultural tourism and urban regeneration into a framework that uses historic sites as catalysts for urban revitalization. The findings support a theoretical framework for understanding and investigating cultural tourism and urban regeneration phenomena. Furthermore, the theoretical framework of the study suggests a methodological application in the following section to study and comprehend the relationship between cultural tourism and urban regeneration in the context of city centers.

3. Research Design and Methodology

The methodological decisions of the researchers have been made to elucidate how Hail residents utilize the Barzan marketplace. The chosen research design is the case study method, with the objective of investigating four primary categories: (1) the market rehabilitation process, (2) social actors, (3) economic actors, and (4) administrative actors. A single case study provides in-depth understanding of issues targeted in this study [66] and useful tools to investigate a process or a system in a specific time and place [67]. The purpose is to comprehend how the Barzan rehabilitation influenced the values and meanings of the marketplace, as well as to make recommendations for improved planning and design based on the input of market users in Hail.

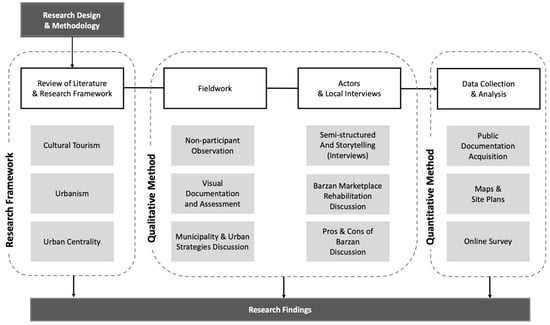

It is widely accepted in urban studies to combine logical argument with observation, and research is not reduced to numbers due to the complexities of urban settings [68]. Using the literature on urban design and planning, this investigation analyzed the built environment of a particular marketplace in Barzan [69]. Several researchers [70] came to the same conclusion. Researchers focused on two variables for this study. The first step was to analyze the current market space design and determine how it can be enhanced through better rehabilitation planning and design. To ascertain if the market areas were accommodating to the public, observational and survey-based research was used to determine the study objectives. This study used a mixed-methods approach, which incorporated ethnographic techniques as well as visual and spatial techniques, all of which added to the depth of the data collected, validity, and reliability of the findings through the process of triangulations [71] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The research design and mixed method chart. Source: Authors.

Additionally, an inductive method is necessary for the systematic, objective-driven procedure required for analyzing the data for the two factors [72]. Therefore, this study employed methodological approaches that explore Barzan as an integration of form, fabric, and cultural practice and used narrative strategies to elicit the market’s complexity. Recognizing the cultural context in which research methods are conducted and adapting to the specific constraints, expectations, and opportunities of the study site and its participants is crucial.

3.1. Storytelling Method

The purpose of this research is to examine the ways in which cultural norms, economic standing, religious beliefs, and racial and ethnic practices shape individual perspectives on market value [73]. According to a study by Mager and Matthey (2015) [74], these criteria were widely used to assess the quality of urban areas because of their weight in determining place forms [75]. Helpful knowledge mobilization techniques include: (1) sharing a wide range of concrete data; (2) connecting disparate knowledge communities in society; and (3) facilitating dialogue across varying degrees of informational similarity and detail among participants [76]. Thus, the study made use of simplifying tools, such as keywords, examples, metaphors, objects, and discourses, to meet the varying requirements and demographic profiles of the market’s knowledge consumers.

3.2. Observation

Overton and Diermen (2003) argue that observations are crucial because they allow “subjective assessments of what is actually occurring [77]”. People’s actions and reactions to their surroundings can be observed, and behavioral patterns can shed light on what motivates those actions and reactions [78]. The researchers went to Barzan to make a mental map, take notes on the behavior of shoppers, take photographs, and observe the market at different times of day to catch different occurrences.

3.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews with a wide range of actors about the Barzan market development process were conducted. The interviews were semi-structured and covered major topics, such as Barzan history, significance, rehabilitation efforts, urban development projects, economic aspects, and social benefits. More questions were asked regarding the usability of the current market, the challenges that the market still faces, and future expectations of Barzan.

For this study, interviews were conducted to acquire insights regarding social and economic aspects. For social concerns, a set of exploratory questions presented to learn about people’s perspectives, opinions, knowledge, experiences, or values on the study objectives included: (1) How would you describe your experience traveling to the place? (2) Is the marketplace well maintained? (3) What is the most frequent reasoning for a place visit? (4) What are future features you would like the marketplace to include? Additionally, further discussion regarding walkability, obstacles, infrastructure related to the marketplace and surrounding context is discussed. For economic concerns, a set of inquiries regarding the marketplace rehabilitation and the effect on place economy is discussed, including: (1) Did the new development encourage place visitation? (2) Did the development aid the shopkeepers? (3) Was there any ongoing discussion between the administration and the shopkeepers during the development process? (4) What are the challenges facing the marketplace from a shopkeeper perspective?

3.4. Survey

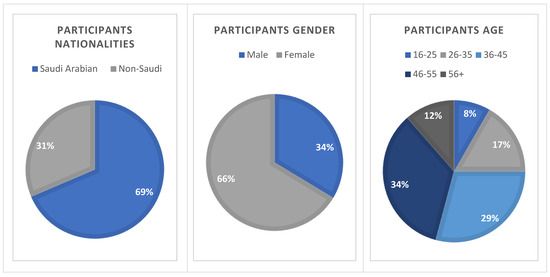

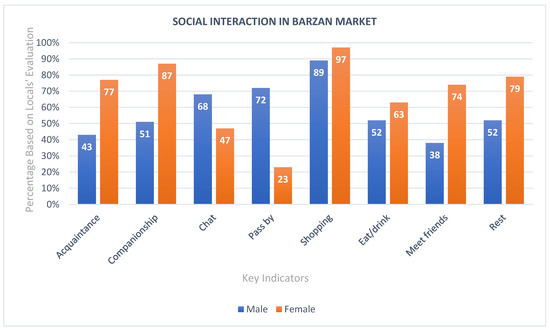

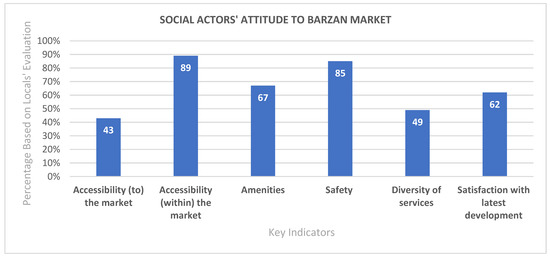

The study used an online survey between 1 October to 8 October 2022 to collect feedback from social actors about Barzan. To support the study objective, two themes were used that targeted the local community using keywords. First, several observation key notes were collected during fieldwork visits; therefore, to support the study observation findings, a survey of the level of social interaction in the Barzan market was conducted. Second, the social attitude toward market rehabilitation and activities was conducted to examine the varying degrees of community market satisfaction (Figure 2). Both themes are intended to better understand how the local community perceives and uses the market under various conditions to: (1) examine how users “use the marketplace” and why they visit on a regular basis, using eight indicators (acquaintance, companionship, chat, pass by, shopping, eat/drink, meet friends, and rest) (2) and elucidate user “attitude” toward the place using five indicators (accessibility to market, accessibility within market, amenities, safety, services diversity, and development satisfaction).

Figure 2.

Sampling size and demographic.

3.5. The City of Hail

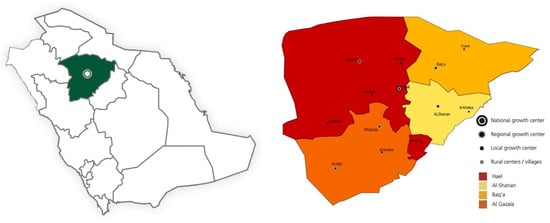

Hail is a city in the Hail Province of Saudi Arabia. The city is located near the Aja Mountains and the Nefud Al-Kebir (Great Sand Dune Desert). These impassable mountains, combined with the equally infamous desert, have kept Hail safe from foreign invasion for centuries. Samra Mountain offers an excellent view of the city. To greet visitors, the legendary Hatim al-Tai would light a fire on top of Samra mountain, where today, it is illuminated by artificial lights and a gas-powered fire, which transforms the mountain into a spectacular sight at night (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hail region location and administrative boundaries.

Hail City has a hot desert climate with an average temperature of 25.5 °C. The coolest months are December and January, with average temperatures of 15 °C, while the hottest month is July, with an average temperature of 35.5 °C. In any given year, the city receives very little rain. Even so, Hail City’s economy is primarily based on agriculture, with water for irrigation coming from deep wells drawing water from the abundant Saq Aquifer. The city is well-known for producing dates, cereal grains, and a variety of fruit. The agricultural sector employs a sizable portion of the city’s workforce. A number of factories and manufacturing plants can also be found in Hail City. A large number of people in the city are employed by these industries. The Hail Region has a population of 670,000 people, according to the 2010 census [79]. It is home to 2.18 percent of the Kingdom’s total population, and 19.5 percent of those who live there are not Saudi. Thus, the governorate of Hail is home to 69.2 percent of the region’s population.

3.6. Historical Brief

Hail is an oasis city with numerous water wells, and the city has long served as a stopover for ancient caravan trade routes and pilgrims. Hail’s people are known for their generosity, and the city is home to the legendary poet and king Hatem al-Tai. Hail City is strategically located at the crossroads of ancient trade routes. It is also a major agricultural center, with numerous farms and gardens. The city’s history dates back to pre-Islamic times. Because of its historical and cultural significance, Hail City is a popular tourist destination.

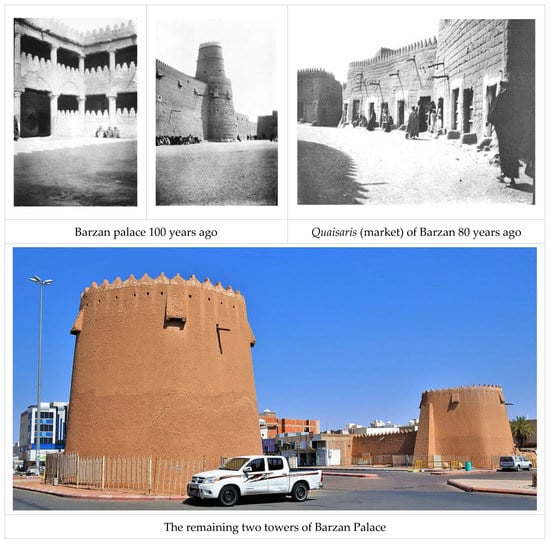

Hail City is well-known for its three large castles, as well as being known for its fertile farmland and, specifically, as a major producer of dates. The city later became an important center for Islamic education. The A’arif Fort is a 200-year-old mud castle. It is located on a hill with a view of the city. It is one of the most popular places to visit in the city and has a beautiful view. The Barzan Palace was a massive structure that spanned over 300,000 square meters. Its construction began in 1808 and was completed during the reign of Talal ibn Abdullah, the second Rashidi emir. It was built on three levels and included reception rooms, gardens, kitchens, and rooms for the Royal Family and diplomatic guests. The third most important fort is the Qishlah Fortress. It is located in the heart of Hail City. It was built in 1750 and was once home to the Hail emirs. The fortress is rectangular and surrounded by high walls. There are four courtyards, as well as a mosque, a prison, and a jail.

3.7. Barzan Market between Past and Present

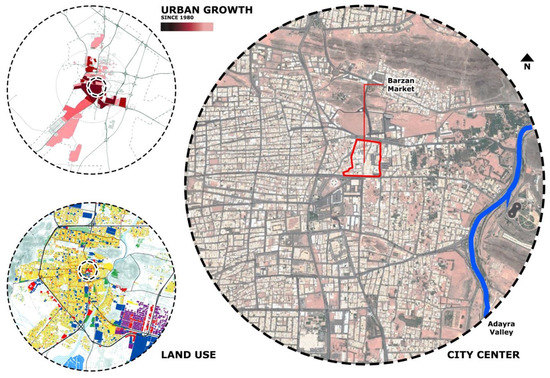

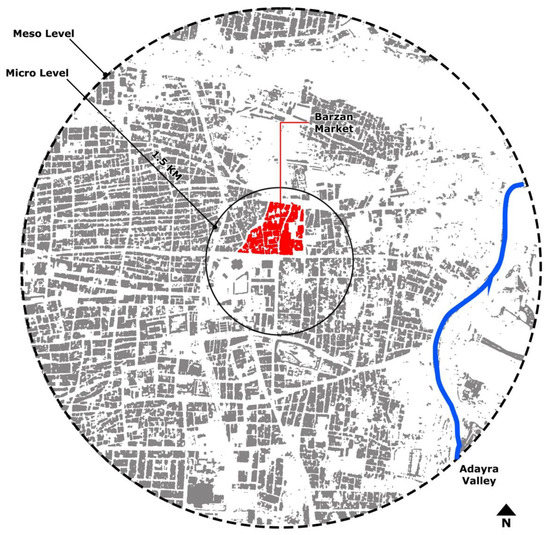

Barzan Market is one of the best places to buy a variety of goods. The market is a great place for a shopping spree, with a large selection of clothing, fragrances, handicrafts, spices, dried fruits, and footwear. It is a convenient shopping venue due to its placement in the heart of the city. Barzan Market is a one-stop shop for all traditional needs, which led the market to being one of the most prominent marketplaces in the region. It is the region’s economic center and the destination of many merchants. As Barzan Market is centrally located in Hail’s historic district, it is one of the city’s most popular tourist attractions (Figure 4). The ease of access to this location, combined with its symbolic significance, results in it being overcrowded for the majority of the year.

Figure 4.

Hail city profile and the location of Barzan Market. Source: Authors.

Because of its proximity to the historic Barzan Palace, the Barzan market site carries a special symbolism. Because it was the tallest building at the time, the market earned the name ‘Barzan’, meaning ‘eminent.’ The Barzan Palace is located adjacent to the Barzan Grand Mosque. The palace was built in 1808 by Prince Muhammad bin Abdul Mohsin Al-Ali. Hail’s Barzan Palace stands 70 feet tall, covers 300,000 square meters, and is three stories in height (Figure 5). The palace was demolished, and some structures, such as the Barzan Towers, remain cut off from their surroundings to this day. These two towers, along with the wall ruins, are among Hail’s earliest historical sites. In the historic Barzan district, they are also important witnesses to previous civilizations.

Figure 5.

Historical images of Hail City. Source: [80] and Authors.

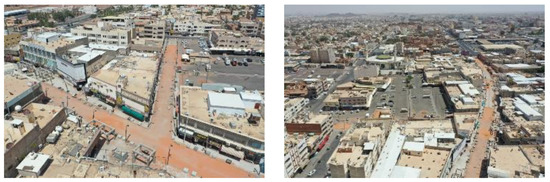

In terms of the Barzan market today, it sits on a 148,082 m2 of land and contains around 384 shops (129 on the main street, 107 on the east side, and 148 on the west side). The market is clearly suffering from a lack of spatial and urban organization, as it is in the condition of a space just before the start of an urban rehabilitation project. The lack of basic services for people who use these spaces, such as shoppers, shop owners, neighborhood residents, and even people who cross into the central area, demonstrates this. And perhaps the thing that stands out the most to someone who frequents this market is that there are not enough places to sit and eat, as well as a general lack of public spaces, places with shade, and bodies of water. According to what we can see and hear in this center, there appears to be a lot of visual and noise pollution, and people who use it can tell it is unsafe because cars and people walk together (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Barzan marketplace main street before development. Source: Authors.

4. Barzan Market Rehabilitation Project

The rehabilitation of the Barzan traditional market was the result of the city needing to redevelop its main tourist attraction, as the place attracted more than three hundred thousand visits on a yearly basis. However, several issues were holding back the market from being a pleasant place to visit, such as accessibility and automobiles using pedestrian pathway areas, which created a negative and unpleasant experience according to users. Therefore, Hail Municipality, in late 2019, took action and redeveloped the market to be solely for pedestrian use, with the intention of increasing the number of visits and creating a more pleasant and enjoyable space (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Barzan marketplace main street under development. Source: Authors.

We contend that renovating and redeveloping Barzan Market is a critical development and symbolic component of the city’s redevelopment and growth. Because the rejuvenation of the market space will attract new businesses and tourists on a regular basis, this project will have a significant economic impact on the city. It is also expected to create new jobs, which will help to increase the city’s population. The redevelopment of Barzan Market is a significant step for Hail City that will undoubtedly benefit the city’s future in terms of cultural tourism.

The goal of the Barzan market rehabilitation project is to improve and beautify its visual perspective, which will benefit the social and economic life of the city center and Hail City in general. The market’s rehabilitation includes the enhancement of facilities, services, and infrastructure. The market beneficiaries are shopkeepers and customers, with the goal of providing them a more enjoyable shopping experience. The administrative goal was to improve the market environment in order to attract new businesses, resulting in an increase in economic activity in the area. With a value of around twelve million Saudi Riyal, the project is considered one of the most significant developments undertaken by the Hail government in recent years, as well as requiring serious policy changes to convert the market area into a pedestrian area, closing and paving the streets with granite, and creating high-class venues for sessions.

As a result, the project includes paving six hundred meters of market avenue with granite material, developing some areas within the three-kilometer radius of the market, redeveloping two entrance gates north and south to define the Barzan marketplace boundaries, and investing in kiosks and public facilities. The rehabilitation of Barzan Market is considered 95% complete, and Hail Municipality promises that, once fully completed, the market will be a safer, more attractive, and more vibrant place, contributing to the area’s economic development. More importantly, a future plan is being considered to connect Barzan with new city center development.

4.1. Examining the Barzan Traditional Market

Examining a map of the market shows the footprints of buildings and the absence of any pattern of void spaces in the urban form. It is possible to observe how the main development of Barzan Market was specifically oriented to create clearer pedestrian pathways. This was made apparent during fieldwork when the main street that connects the north and south entrances transformed into the main pedestrian pathway. This transformation of usage boosted visitation traffic to this area of the market, and shopkeepers asserted that visitation to their shops is noticeably higher (Figure 8) (An interview with eleven shopkeepers regarding visitation activities on 29 September 2022).

Figure 8.

Barzan Market location within Hail City. Source: Authors.

Different types of solid formation in the Barzan traditional market and the absence of significant void spaces (open public spaces) confirm the presence of a dominant holistic urban form, which includes the main traditional market structure and nearby archaeological monumental public buildings. The open spaces, however, are mostly pedestrian pathways and small open spaces near the mosque. The blocks and buildings have a regular pattern, and interior spaces form irregular pathways. One issue observed in the market is that most pathways do not lead to significant areas within the market, which questions the logic behind the market’s urban formation. This finding came true when interviewing a number of shopkeepers who asserted the significant issue of low traffic visitation to certain areas within the market. They argue that, even though their shops are in a main or secondary pathway, the traffic is low due to the pathway leading, in most cases, to either a parking lot or an insignificant place, which discourages visits to their shops, as other areas have more activities (Figure 9) (An interview with eight shopkeepers regarding their perspective on their shop placement and activities on 30 September 2022).

Figure 9.

Spatial analysis of Barzan Market. Source: Authors.

Even though we believe that in any marketplace all shops are not weighted equally, and certain areas will certainty have more traffic than others, the recent rehabilitation of Barzan traditional market did not take this notion into consideration. However, the development has emphasized certain areas more significantly than others, as well as producing more pathways that lead to insignificant areas within the market. In this regard, we contend that the development was superficial and did not try to solve the main issue that actors (shopkeepers) face, which in the long run may jeopardize the longevity of the market.

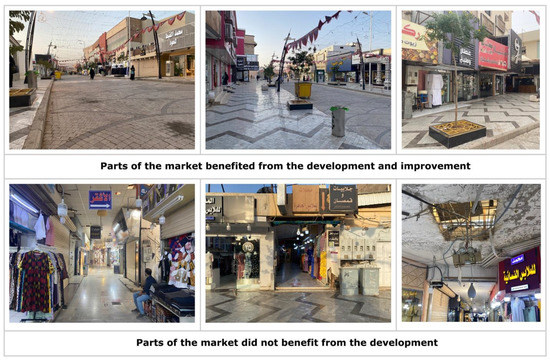

As a result, the rehabilitation of the market only focused on exterior representation by paving the streets, adding new furniture, and adding a few facilities, which we believe is acceptable, to a certain degree. However, such a significant project should give more attention to the market’s main issues, such as the lack of organization among shop categories, undefined place characteristics, as well as older and inner areas being neglected during the development process, which is believed to negatively affect the overall market experience of visitors. More importantly, the rehabilitation of the market did not try to create open spaces nor invest in connectivity opportunities with nearby attractions.

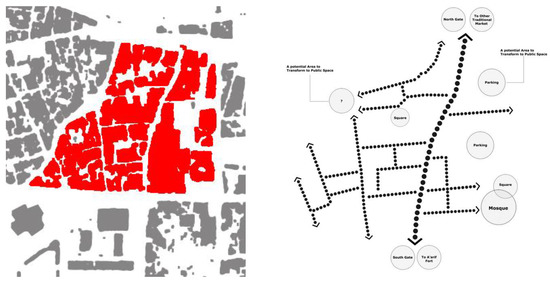

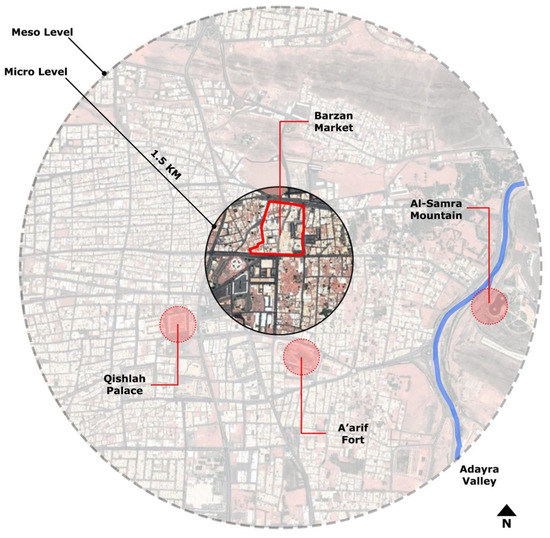

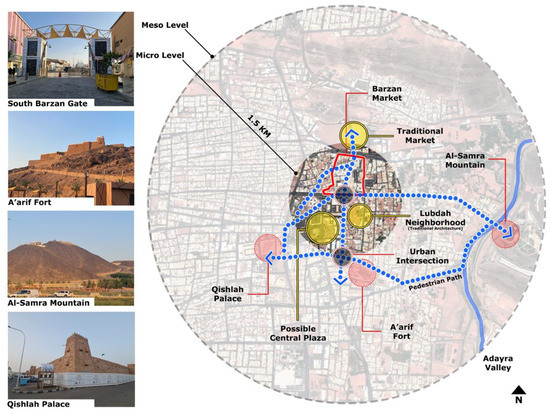

As the Barzan market rehabilitation and development project is part of the future city center area development, it requires more attention to urban and architectural details to enhance the overall experience of the place. For example, one of the other development projects that has been implemented in the city center is the development of A’arif Fort on the south side of Barzan. The fort is a heritage landmark and has significant cultural and historical value. In addition, Qishlah Palace on the west side is considered a significant heritage landmark and is also under rehabilitation (Figure 10). Even though Barzan is in close proximity to other nearby heritage landmarks that could help enhance the concept of cultural tourism, the Hail administration has not yet provided any future plans for how it could possibly make use of these places and develop a cultural experience by linking several areas in the city center. As a result, the development of the city center should be an ongoing process that is essential for the continued growth of the city. Therefore, this study is to provide key insights for future cultural tourism initiatives for the city center, as we contend that it may help the Hail administration to boost tourism and city growth in the long run.

Figure 10.

Micro and meso levels of the city center showing other significant historical landmarks. Source: Authors.

4.2. Social Actors

‘Place’ embodies cultural elements from which people draw references to construct their sense of ‘self.’ Place is also used by the authorities to manipulate personal identity and culture [81]. Therefore, to ensure the success of any project, social actors should participate and play multiple roles in order to produce goods and services through interactions with other actors in various contexts [82]. During interviews with several Barzan Market users, for example, they stated that they prefer the traditional marketplace to other commercial sites (e.g., markets, shopping malls, etc.) because it provides spatial harmony, social hierarchy, and social interaction that no other place can provide (An interview with four males and two females regarding the main attraction of visiting Barzan market on 2 October 2022). Such an insight highlights Lamb and Kling’s argument that Barzan not only provides a shopping experience, but it is also more of a social experience (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Social participation in Barzan main street. Source: Authors.

A survey participant who lives near Barzan, in the city center, mentioned the changes that he noticed in the Barzan area, saying that some of the shopkeepers he used to buy from closed their stalls because they could not fulfil the newly required standards of the place. The loss of specific shopkeepers affected the participant’s visitation frequency for the newly developed marketplace. This demonstrates the power of social relationships in the marketplace, where some shopkeepers themselves highlighted that Barzan Market is not only a place for earning their livelihood, but it is also a place where they experience companionship with their neighbors who live near the market, which is an important aspect of their quality of life; it impacts their ability to thrive (An interview with one visitor and three shopkeepers regarding social relationship on 2 October 2022). As a result, any development should prioritize sustainable urban strategies that benefit not only the place itself, and its pure commercial aspects, but also seek to benefit the nearby residents and users as they are the first-place contributors.

To assess Barzan Market, an online survey with two main objectives was deployed: (1) to examine how users use the marketplace, and why they visit on a regular basis using eight indicators (2) and making use of five indicators to elucidate user attitude toward the place. In the first objective, the survey results showed that the shopping experience is the biggest attraction of the place, which is reasonable, as Barzan is a marketplace for traditional goods (Figure 12). However, the market’s role in facilitating acquaintance and companionship was an interesting observation, as Barzan seems to be a suitable place for female social interaction. On the contrary, male users use the place to either pass by or have quick social chats. The difference in usage of the place between male and female (with children) users was evident during fieldwork observation, as females were more invested in the place and use of the market as a social hub.

Figure 12.

Social interaction assessment.

Similar findings were reached by Apichoke Lekagul (2002) when he examined the traditional marketplace in Bangkok, where he asserted that most of the participants cite the close relationships with the sellers, the freedom of the place for social experience, and the unique traditional identity the market offers are why the participants assert that they “want to be there” [83]. This is true in Barzan Market, as well as that users not only visit the market for shopping purposes, but also believe that it is a place that embodies a unique place identity and social experience.

Using five key indicators, the second online survey was conducted to examine users’ attitude towards Barzan Market. The goal was to understand how users perceive and appreciate certain aspects of the place (Figure 13). The main issue was transportation and accessibility, where users argue that difficulty reaching the market (e.g., condensed urban area, limited parking, etc.) is one of the main factors that causes them to not frequently visit the place. On the contrary, the same users asserted that once they are within the marketplace, pathways and accessibility areas are clear and comfortable for pedestrians (An interview with two males and one female regarding transportation and accessibility to Barzan Market on 2 October 2022). However, as some of these pathways do not lead to significant spaces, users are discouraged from visiting certain areas within the marketplace.

Figure 13.

Social attitude assessment.

Another aspect that needs attention, as it has been overlooked, is the amenities and diversity of services that the marketplace provides. Currently, the place lacks activities that can attract users from different social groups and suffers from a lack of void spaces that can encourage users to settle and spend time in the market. Providing or enhancing these two aspects may cause the market’s economy to thrive, as social actors tend to invest more if the place provides the necessary quality of space, facilitates a comfortable social experience, and hosts sufficient entertainment activities.

Therefore, even though the Barzan traditional market went through a recent rehabilitation in 2019, the survey results show that there are still opportunities for improvement. Users state that they highly appreciate the new additions, especially the intentional transformation of the main street to a pedestrian pathway. However, they believe that some key issues of the market still have not been addressed, such as enhancing the inner areas (shaded shops) of the market, as well as the safety of these areas. In addition, there remains a lack of organization among different shop types, where several shopkeepers discussed the issue of food places situated near their clothing shops negatively affecting the experience the consumers due to strong aromas from the food shops (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Overlapping of food places and architectural elements with the shop’s storefronts. Source: Authors.

Barzan Market is considered a significant place for the inhabitants of Hail. However, if users are to survive and thrive in the traditional market, Hail City should indeed provide them with security, resilience, and adaptability. This necessitates public policies that provide a stable and secure environment for shopkeepers and customers. Thus, if the recent social changes in Hail are to be successfully managed, Hail administrators will need to implement a new and broad range of policies that are adaptable to change as needed.

4.3. Economic Actors

Accessibility is an essential component of any city’s infrastructure, connecting people and businesses, while also promoting economic growth. To stimulate the market’s economic growth, Hail’s administration should invest in better infrastructure. This includes building new roads, upgrading existing ones, and investing in new technology, such as intelligent traffic management systems, to smooth traffic flow and avoid congestion in the area. Users argued that one of the main issues confronting Barzan Market is its accessibility; thus, developing the market alone is ineffective, and the city’s administration should focus on the city center as a whole and especially at the ‘meso level.’

During an interview with three shopkeepers located along the main pedestrian pathway, they stated and agreed with each other that they appreciate any type of market development; however, they stated that the new development shifted traffic flow to the two northeast parking lots. Most customers now go to the parking lot and just shop stores near the parking lot, leaving others on the main pedestrian street and further away from the parking lots to suffer from low visitation (An interview with three male shopkeepers regarding accessibility within Barzan Market on 2 October 2022). This insight returns to the market’s accessibility issue, where in the case of these shopkeepers (around thirty-four shops), the development is considered negative because it became more difficult for consumers to reach their stores on a regular basis, especially during the afternoon and summer season due to high temperatures.

As a result, in a city such as Hail, where the summer temperature averages 35.5 °C, paving only the street for pedestrians and failing to provide the necessary thermal comfort factors reduces consumer visitation during the afternoon, jeopardizing the economic benefit of shopkeepers. This is true because, during several fieldwork visits, the number of users using the main pathway in the afternoon (around 11 a.m. to 3 p.m.) is nearly non-existent. In addition, several shopkeepers on the main street stated that, while they would like to be open all day, it is not economically feasible for them to open in the afternoon due to low traffic in this area. Thus, the market is only half-open at this time of day, with the inner and shaded areas near the northeast parking lot fully open, but the main street, which is supposed to be the market’s main attraction, is mostly closed (Figure 15). It is worth noting that, in Saudi Arabia, citizens rely heavily on cars to move from one place to another. It will undoubtedly take time for citizens to accept the concept of converting the Barzan main axes to a walkable paved street. This may explain why pedestrian traffic is low at times of day, as walking is not feasible or comfortable at certain times of day (e.g., mid-afternoon). As a result, Hail administration must provide certain space qualities to encourage walkability if such a development is to succeed.

Figure 15.

Barzan marketplace main street during mid-afternoon. Source: Authors.

Aside from the several issues that hinder the economic growth of the market, which we contend are beyond the market level, improving thermal comfort conditions in the market is an important first step toward increasing the place’s usability throughout the day. Because excessive heat disrupts the shopping process, consumers become uncomfortable and are less likely to complete their shopping experience or, in extreme cases, do not repeat the experience. Installing air conditioning in inner and shaded areas, evaporative cooling systems, providing a variety of shaded areas through structural elements and landscape, using fans or other mechanical means of circulation, and selecting appropriate materials are all ways to improve thermal comfort conditions in a market. Such actions will create a more comfortable environment for the customers and help to boost the market’s economic activity, even if only a few of these steps are taken.

Grouping similar functions together is one of the most important aspects of market design and may help in cases such as Barzan. Customers expect to find clothing stores near other clothing stores and restaurants near other restaurants. This grouping helps shoppers find what they need, creates a natural flow within the market, and may group the market into different category zones. For example, during an interview, a shopkeeper claimed that the construction of public toilets near his store obscured his storefront linkage with the main street and reduced the shopping experience in his store area. As a result, we can say that during the market’s development, some key aspects were overlooked by the redevelopers, resulting in individual and collective negative economic impact for shopkeepers in the marketplace.

4.4. Administrative Actors

In line with the Kingdom’s 2030 Vision, the Ministry of Tourism is working to activate and develop the tourism sector in order to contribute to the economy and improve the quality of life in Saudi cities. A national program is also deployed to improve the quality of life and attract investment in the tourism sector, including a number of initiatives and projects that aim to improve infrastructure and provide services that meet the needs of tourists across all Saudi regions. Hail as a city is part of this program and is considered one of the Saudi cities that has high cultural tourism potential. As a result, Barzan’s rehabilitation, which was implemented in late 2019, contributes to this governmental and ministry vision.

Several initiatives relate to and, as a result, expedited the Barzan redevelopment project. We could say that the Saudi Quality of Life Program is one of the main initiatives that Hail municipality intended to implement in the marketplace to improve the quality of life of users and shopkeepers through various urban developments and activities [84]. Even though certain place qualities of Barzan have improved, the question remains as to what Barzan offers to the city center, especially since there are several historic landmarks nearby. This is a question that has yet to be investigated by the municipality of Hail to determine the possibilities.

What has been examined so far in this study indicates that the Hail administration is only invested at the ‘micro level’ of buildings or places, whereas the Barzan marketplace, if it is to thrive, needs to be developed at the “meso level”, and opportunities must be found to link it with several historic landmarks nearby. We contend that if this is implemented, not only will Barzan benefit from such a development, but the whole city center will thrive and be a cultural destination. What has been developed so far suggests that the Hail administration is aiming to fulfil certain benchmarks within the governmental initiatives, without paying careful attention to certain issues and opportunities identified and elaborated upon in this study.

5. Findings and Discussion

This study revealed and discussed several insights at various building and urban levels in Barzan. Major challenges confront the project and must be addressed, including local government leadership, consistent funding, active support from stakeholders, and partnership and collaboration among Barzan stakeholders. To be able to boost the economy, improve the quality of life in the city, and become a tourist attraction, Hail administration should make use of the existing heritage. Because the city has received government support for cultural tourism, we argue that highlighting historical tourist monuments to promote the city’s cultural tourism will be much more cost-effective and marketing effective. This can be accomplished by promoting and protecting historic landmarks and traditional neighborhoods within the city center, as well as by encouraging the growth of art, tradition, and cultural scenes. This cannot be achieved unless the city provides the right environment and conditions for investors to participate.

We believe that, with some creativity, we can contribute to reinventing tourism at this traditional cultural destination. Therefore, the study categorizes its findings into two main levels of discussion: the micro and meso urban levels, in order to discuss the Barzan marketplace, and the city center urban level possibilities.

5.1. Micro Level (Barzan Market)

The process of urban improvement in Barzan Market, despite the significant level of effort and investment, focused on the main street axes and neglected other, secondary axes that we contend lead to other important parts of the market. This led to unbalanced development in relation to the different parts of the marketplace by creating a state of centralization of the shopping process and movement along the main axes. Based on the study’s finding that the main axis failed to boost the market’s economy, as in mid-afternoon users usually do not pass by this area, which led stores closing at this time of day. As a result, market activity is decreased, and economic value is jeopardized due to the stores either being closed half the day or having less costumer traffic. It is essential for any urban intervention to recognize the opportunity for improvement and development in all sectors of the market in order to cultivate economic activity across the entire market.

The majority of the improvements focused on paving floors, building gates, and installing lighting. Based on the study findings and examination, we can conclude that it was a superficial development that did not seek to resolve the marketplace’s main issues. For example, the lack of attention paid to improving shopfronts was a missed opportunity, as there was the possibility of unifying the main axes and giving Barzan the heritage character it requires, which could serve to confirm and promote the architectural identity of the city and market. Additionally, the sagging of electrical wires in the inner areas of the market causes visual distortion, as well as in certain areas the old roofs have started falling off; they have reached the end of their lifespan and need to be replaced (Figure 16). All these elements have not been included in the rehabilitation process and they continue to weaken the market experience.

Figure 16.

The different degrees of Barzan development and improvement. Source: Authors.

5.2. Meso Level (City Center)

At this urban level, several issues related to Barzan Market manifest themselves, and poor linkages with the marketplace can be observed among a number of heritage monuments of the city, such as Al-Samra Mountain, Qishlah Palace, and A’arif Fort. Therefore, this study argues that any urban intervention that seeks to develop Barzan Market must not be looked at solely from the perspective of the market, but must take into account the market’s impact on a larger scale, which begins at the ‘meso level’ of the city center. This is because of the historic significance of this part of the city, as well as the unique nature of its commercial center, which is considered one of the most essential components of the city’s cultural and social identity.

There is no doubt that the Hail administration is productive and has undertaken several initiatives to enhance and develop several sites within the city center. However, the main issue observed is that the urban rehabilitation of these projects that take place at the city center ‘meso level’ are still carried out separately. There have not yet, it seems, been any attempts to realize ‘synergies’ across the multiple cultural attractions. No scheme has yet provided for a potential cultural tourism path among the several city center commercial areas and among the several nearby historical landmarks. Thus, in order to boost the economy of Barzan Market and its shopkeepers and other nearby sites, it is necessary to develop a comprehensive vision that links the city’s main tourist attractions with each other. This can be achieved by creating urban axes, tourist paths (‘walking tours’), and transforming unnecessary roads into public spaces for pedestrians, as well as retrofitting certain areas (Figure 17). By doing so, the city can create and provide sustainable and enjoyable experiences for both locals and visitors. More importantly, it may establish opportunities for private and public stakeholders to invest in the place.

Figure 17.

Meso level of the city center showing the potentiality of linking other significant historical landmarks with Barzan Market. Source: Authors.

This finding connects to Kevin Lynch’s seminal work in (1960), when many researchers and urban planners became interested in the tangible elements of the city capable of structuring its users’ mental representations of a “destination image” [85]. In the case of the Barzan market, legibility of places can be critical, where Lynch’s “paths,” “nods,” and “landmarks” typologies may contribute to understanding the various elements structuring perception for guiding the development of the physical city to achieve a more pleasant, readable, and symbolic form, by connecting several locations within the Hail City meso level. It is one of the missing trends of the comprehensive development of the Hail city center.

This would allow for a greater sense of inclusivity within the market space and would make it more accessible to a wider range of people. As a result of the lack of comprehensive development, it is difficult to carry out any kind of urban intervention on the historic Barzan market without first taking into consideration the significant role that the market plays in the historic center of Hail City. We contend that it is unreasonable that Barzan Market and its revitalization is not seen as a significant contribution to the revitalization of cultural tourism in the city of Hail.

Barzan Market is characterized by its central location within Hail City and its fair accessibility from various parts of the city. One of the challenges that comes with urban centralization is that it can lead to increased pressure on infrastructure and services. Therefore, supporting urban centralization in the Barzan market must be accompanied by a comprehensive view of the state of urban centralization at the level of the city and the region. To provide a good distribution of multi-centers and services and avoid increasing pressure on the city center as visits increase, the Hail administration should focus on providing heritage and cultural services, as well as more pedestrian options in the city center to distribute pressure among several sites.

6. Recommendations

The findings of this study suggest that heritage sites in city centers are encapsulated through an urban development strategy to promote cultural tourism. Tangible and intangible cultural heritage aspects play crucial roles in creating a positive tourist destination image which enhances heritage destination attractiveness, identity, marketing, and perception. The following measures and aspects are recommended to be the backbone of sustainable urban management:

- A new introduction of economic driving forces, such as activities, uses that promote employment, local community contribution, participation, and production, and cultural–tourism activities are necessary for a functional site; however, heritage values, cultural identity, and a sense of place should be preserved;

- Economic benefits and local community needs should be balanced;

- A partnership between the local community and policymakers is necessary to maintain a healthy socioeconomic characteristic in the area;

- Political, institutional, and developers’ actors are key players that should be managed in line with and adhere to heritage requirements;

- Intervention and rehabilitation strategies are key factors in preserving culture and revitalizing uses. For example, preserving heritage assets, protecting urban typology, rehabilitating historic architecture, and enhancing public spaces and connectivity between different public areas, uses, and destinations;

- Improving city center’s functions, amenities, and infrastructure;

- Improving the environmental condition of the place;

- Tourism management is an integral part of the urban development management process.

7. Conclusions

Cultural tourism in historic cities is undeniably a significant source of economic activity and revitalization, as well as a means of preserving cultural heritage values. In terms of preserving and promoting cultural heritage, cultural tourism can be both a tool and an end goal. The rehabilitation of Barzan Market is an example that showcases the complexity of developing an urban project. As this study presented, the project interacts and deals with different actors that have different interests in the place. As the market is located in a densely populated area in Hail, its rehabilitation become crucial to improving the quality of life of Hail residents. However, the process is not straightforward, as it required the coordination of many different actors, including the government, the private sector, NGOs, and international organizations. The multiplicity of players and influencers in any urban project remains one of the factors that increases the complexity of this type of project. However, despite the difficulties, it is essential to continue working on improving the urban environment, taking into account the needs of all actors.

This study highlights three fundamental issues observed through dealing with the study topic:

Theoretical contribution: cultural heritage tourism has the potential to be a powerful tool for urban regeneration. When implemented correctly, it can help to boost the economy, create jobs, and protect the environment. However, it is important to approach cultural heritage tourism with caution and respect for the local culture. Innovative cultural tourism can engage visitors through the use of a variety of tools, media, and techniques. The findings of this research lend support to a theoretical framework for comprehending and researching cultural tourism and urban regeneration phenomena. By taking advantage of the opportunities offered by cultural heritage tourism, cities can breathe new life into historic urban districts. This study offered an integrative framework to understand cultural, social, economic, and tourism aspects, understanding cultural tourism activities in urban centers through the process of urban regeneration.

Managerial implications: many cities attract tourists by emphasizing history and culture. Since the city has government support for cultural tourism, we think highlighting historical tourist monuments will be more cost-effective and marketing-effective. This can be achieved by promoting and protecting city center historic landmarks and neighborhoods and encouraging art, tradition, and culture. We can attract international tourists who want to learn about new cultures and visit heritage sites by highlighting the city’s history and culture. The study found that studying cultural tourism’s effects on multiple levels is crucial. The urban micro level can improve the market for store owners and shoppers by investing in all areas. The miso level will enhance the city’s public space. People can gather and interact in this new public space. The miso level will also connect the historic center to pedestrians. This pedestrian link will improve traffic flow between the city’s sides.

Limitations and future research: while many cities are focusing on revitalizing their downtown areas in order to attract more businesses and residents, some studies have found that this can lead to urban gentrification. Studies on the impact of downtown revitalization projects on urban gentrification are limited, but future studies may help to shed light on this complex issue.

Future studies could focus on providing more empirical evidence regarding the effects of such a development on urban structure, as well as investigating the interrelationships and potential mediating effects of the various factors at the macro level of the city. As we contend, this may enable the creation of urban “multi-centrality” locations within the city.

Although we have utilized many of the theoretical resources and assessment tools currently available, future research may also use other sources, such as user-generated content (UGC) to understand tourism destination image and visitor perception, despite its limitations. It can enhance a destination’s image when used with other data sources. UGC can still reveal how visitors view tourism destination image components, where it can enhance a destination’s image when combined with other data sources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.N.; Data curation, M.M.A. and K.E.; Formal analysis, E.N. and G.A.A.; Funding acquisition, E.N.; Investigation, E.N., M.M.A. and M.H.H.A.; Methodology, E.N., M.M.A. and M.A.B.; Project administration, E.N.; Resources, M.M.A., G.A.A. and M.H.H.A.; Software, M.M.A. and M.A.B.; Supervision, E.N.; Validation, E.N., M.M.A. and M.A.B.; Visualization, M.M.A. and K.E.; Writing—original draft, E.N. and M.M.A.; Writing—review and editing, M.A.B. and G.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Scientific Research Deanship at the University of Hail– Saudi Arabia] project number [RD-21091].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by [Scientific Research Deanship at the University of Hail—Saudi Arabia] project number [RD-21091]. We also appreciate Hail Municipality’s contribution of market data and essential information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Spirou, C. Urban Tourism and Urban Change: Cities in a Global Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, C.M.; Rogerson, J.M. Historical Urban Tourism. Urbani Izziv 2019, 30, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbasli, A. Tourists in Historic Towns: Urban Conservation and Heritage Management; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tunbridge, J. The Tourist Historic City: Retrospect and Prospect of Managing the Heritage City; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Leask, A. Progress in visitor attraction research: Towards more effective management. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Rawding, L. Tourism marketing images of industrial cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowitz, E.; Ibenholt, K. Economic impacts of cultural heritage–Research and perspectives. J. Cult. Herit. 2009, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. Global Report on City Tourism—Cities 2012 Project in AM Reports; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2012.

- Williams, R.J. The Anxious City: British Urbanism in the Late 20th Century; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, D.B.; Castillo, L.A.; Salomao, E.M.A. Tourist use of historic cities: Review of international agreements and literature. Int. J. Humanit. Stud. 2014, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Toselli, C. Algunas Reflexiones Sobre el Turismo Cultural. 2006. Available online: https://www.pasosonline.org/Publicados/4206/PS040206.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Roberts, P. The Evolution, Definition and Purpose of Urban Regeneration. In Urban Regeneration: A Handbook; Sage Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Press, S.N. HRH Crown Prince Unveils Saudi Downtown Company, Which Aims to Develop Downtowns in Saudi Arabia. 2022. Available online: https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2389363 (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Ibrahim, A.O.; Baqawy, G.A.; Mohamed, M.A.S. Tourism Attraction Sites: Boasting the Booming Tourism of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2021, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, P.; Boniface, P. Heritage and Tourism in “The Global Village” (Heritage); Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Cultural Attractions and European Tourism; Cabi: Wallingford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Condition of Postmodernity; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies; Urry, J., Ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Richards, G.B. Cultural Tourism in Europe; Cab International: Wallingford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Meethan, K. Consuming (in) the Civilized City. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, C. Cultural heritage and tourism evolution. Hist. Environ. 1990, 7, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage Tourism; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage Tourism in the 21st Century: Valued Traditions and New Perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2006, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, S. Heritage management for heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 1989, 10, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, P. Managing Quality Cultural Tourism (Heritage); Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Managing heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 682–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Ashworth, G. Heritage tourism—Current resource for conflict. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Olsen, D.H. Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Tourism and the personal heritage experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. The core of heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccossis, H.; Nijkamp, P. Sustainable Tourism Development; Avebury Aldershot: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nijkamp, P.; Coccossis, H. Planning for Our Cultural Heritage; Avebury: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Coccossis, H. Sustainable Development and Tourism: Opportunities and Threats to Cultural Heritage from Tourism. In Cultural tourism and Sustainable Local Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, L.F.; Nijkamp, P. Cultural Tourism and Sustainable Local Development; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, E. Native Tours: The Anthropology of Travel and Tourism; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Said, S.; Zainal, S.S.; Thomas, M.G.; Goodey, B. Sustaining old historic cities through heritage-led regeneration. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 179, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Fouseki, K.; Nicolau, M. Urban heritage dynamics in ‘heritage-led regeneration’: Towards a sustainable lifestyles approach. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2018, 9, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogruyol, K.; Aziz, Z.; Arayici, Y. Eye of sustainable planning: A conceptual heritage-led urban regeneration planning framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alverti, E.; Fouseki, K. Urban ‘Regeneration’in Historic Places: The Case of King’s Cross Central, London. In Heritage and Sustainable Urban Transformations; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamid, M.M.; El Hakeh, A.H.; Elfakharany, M.M. Heritage-led urban regeneration: The case of “El-Shalalat District”, Alexandria. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Faouri, B.F.; Sibley, M. Heritage-led urban regeneration in the context of WH listing: Lessons and opportunities for the newly inscribed city of As-Salt in Jordan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J. Urban Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski, J.; Benson, A.; Arnold, D. Contemporary Issues in Cultural Heritage Tourism: Introduction. In Contemporary Issues in Cultural Tourism Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.K. Issues in Cultural Tourism Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser, N. Planning for urban heritage places: Reconciling conservation, tourism, and sustainable development. J. Plan. Lit. 2003, 17, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtany, A.; Aravindakshan, S. Urbanization in Saudi Arabia and sustainability challenges of cities and heritage sites: Heuristical insights. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Revitalising Historic Urban Quarters; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D.; Petetskaya, K. Heritage-led urban rehabilitation: Evaluation methods and an application in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. City Cult. Soc. 2021, 26, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.B. The meaning and measurement of destination image. J. Tour. Stud. 1991, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Marine-Roig, E. Destination image analytics through traveller-generated content. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.S. The role of destination image in tourism: A review and discussion. Tour. Rev. 1990, 45, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. Destination image analysis—A review of 142 papers from 1973 to 2000. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Ali, F.; Kim, W.G. Reexamination of the role of destination image in tourism: An updated literature review. E-Rev. Tour. Res. 2015, 12, 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Fakeye, P.C.; Crompton, J.L. Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. J. Travel Res. 1991, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manheim, J.B.; Albritton, R.B. Changing national images: International public relations and media agenda setting. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1983, 78, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, K.E. The Image: Knowledge in Life and Society; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MO, USA, 1956; Volume 47. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B. Measuring the gap between projected and perceived destination images of Catalonia using compositional analysis. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubert, M.; Warcholik, W.; Żemła, M. The influence of elements of cultural heritage on the image of destinations, using four Polish cities as an example. Land 2021, 10, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzerini, F. Intangible cultural heritage: The living culture of peoples. Eur. J. Int. Law 2011, 22, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W. Braveheart-ed Ned Kelly: Historic films, heritage tourism and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, R.P.R. Management of Historic Centres; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2001; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K.; Pafka, E. The science of urban design? Urban Des. Int. 2016, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carp, F.M.; Carp, A. A complementary/congruence model of well-being or mental health for the community elderly. In Elderly People and the Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; pp. 279–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana, E.; Lovegreen, L.; Kahana, B.; Kahana, M. Person, environment, and person-environment fit as influences on residential satisfaction of elders. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 434–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucks-Ahidiana, Z.; Bierbaum, A.H. Qualitative spaces: Integrating spatial analysis for a mixed methods approach. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2015, 14, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, G.E.; Clayton, P. Qualitative Research for the Information Professional: A Practical Handbook; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mager, C.; Matthey, L. Tales of the City. Storytelling as a contemporary tool of urban planning and design. Artic.-J. Urban Res. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, T.; Haxhija, S. Storytelling of and for Planning-Urban Planning through Participatory Narrative-Building. In Proceedings of the 56th ISOCARP World Planning Congress, Virtual, 8 November 2020–4 February 2021. [Google Scholar]