5.1. Do Eco-Based Strategies Address Social Resilience?

Proposed future resilient landscapes envisioned and described in the RbD plans are conceived of as visible and public spaces. Ecosystem processes that might otherwise only be accessible to environmental scientists become public space, are incorporated into the performance of urban landscapes, and are made visible in order to mitigate weather extremes, while creating a place of identity. All of the RbD proposals discuss explicitly the need to involve people from impacted communities in the restoration processes at hand. Social benefits are not only addressed by layering recreational activities, such as walking and biking trails, on top of restored watersheds and coastal landscapes, but these critical landscapes also become sources of knowledge and opportunities for education for those directly impacted by their restoration.

Most notably, the People’s Plan team working in North Richmond foregrounds the transfer of knowledge from soft/green infrastructure restoration projects to other projects and processes that would empower people and promote social resilience. Towards that end, the People’s Plan proposal emphasized the need to not only involve community members in restoring degraded landscapes but to provide ongoing technical expertise and education opportunities in order to strengthen within the community their ability to collectively interpret and solve future climate-related challenges, such as flooding or storm surges. Here, ecological and social resilience build on each other.

Another form that socio-ecological resilience takes in the proposals is through recommendations to establish various social institutions, groups, and networks that can have an ongoing and direct relationship to the neighborhood’s changing ecology. The Estuary Commons proposal, for example, suggests that a Joint Powers Authority be established across different cities connected through a concern over shared climate change impacts. Such an authority would manage adaptation projects on a collective regional, rather than individual city, basis. Unlock Alameda Creek proposes that multiple agencies be involved in ongoing engagement with key stakeholders, including landowners and operators, for the short and long-term planning of the regional baylands. In addition to enhancing the connectivity of environmental systems and the ecological functions across jurisdictions, the Grand Bayway proposal also emphasizes that plan implementations should foreground the regional workforce.

The design strategies that the plans offer, in other words, highlight the need for multi-jurisdictional and cross-scalar collaborations and partnerships that address urban and environmental processes as mutually constituted. Urbanization is not simply meant to be supported by environmental processes; implied in the proposals is the recognition that eco-based design strategies must frame urban processes as inseparable from ecological ones. It is not surprising, then, to see that many of the plans emphasize affordable housing units, investment in schools, and requirement for local hiring practices amid eco-based proposals for stormwater, air, reservoirs, and soft infrastructures for rising sea levels. This is similar to recent findings on Climate Action Plans, where researchers highlight a correlation between references to equity and the inclusion of more systemic policy proposals that involve housing, coupled with green infrastructure [

43].

The RbD plans that highlight equity, and that emphasize historic and systemic disinvestment in communities, there is also a more comprehensive approach to the proposed strategies. This mix of strategies involves affordable housing, investment in infrastructure upgrades, resilient ecosystems and landscapes that can absorb climate risk, and a framework for supporting existing and creating new social groups and networks to interface with governance processes and agencies.

Social resilience, or the capacity of populations to respond to and recover from a crisis, is not officially defined in any of the design proposals. Instead, its definition is implied through design ideas on how to strengthen social ties. All the plans address social resilience in different ways that range from recommendations to create resilience hubs (i.e., Our Home), building existing community-based organizational capacity (i.e., Estuary Commons), and managing the future of vacant parcels through community land trusts (i.e., Elevate San Rafael). The plans as a whole do not, however, offer concrete proposals that are based on an on-the-ground assessment of existing social networks and community groups or organizations. This is the case even for those design teams who worked with local community members directly throughout the design process. The plans also lack a concrete framework that comprise social resilience attributes, such as existing knowledge and skills, people-place connections, community infrastructure, a diverse economy, and engaged governance [

44].

A design process can serve as a tool through which to promote collaborative networking relationships that can survive the publication of the resilience plans, if such relationships and networks are identified and incorporated into the design process. The People’s Plan proposal, for example, worked exclusively with community-based organizations and community members to generate a process and methodology for equitable and sustainable community development that focused on using the community’s assets to build local solutions to local challenges. The Our Home team, also particularly successful in building social resilience, created a Citizen’s Advisory Board that is comprised of community members, institutional actors, and environmental experts and advocates, which continued to meet well after the end of the competition. The majority of the proposals, however, aimed to support the community in generating design ideas but it is not clear whether these collaborations continued beyond the publication of the final design reports. As one team member noted, given the few months the teams had to prepare design proposals that would address historic and ongoing systemic environmental and social inequalities, “we simply didn’t have enough time to work with organizations and community members to build the kind and depth of understanding needed to do the kind of work we were trying to do” (Anonymous, personal communication, 17 August 2020).

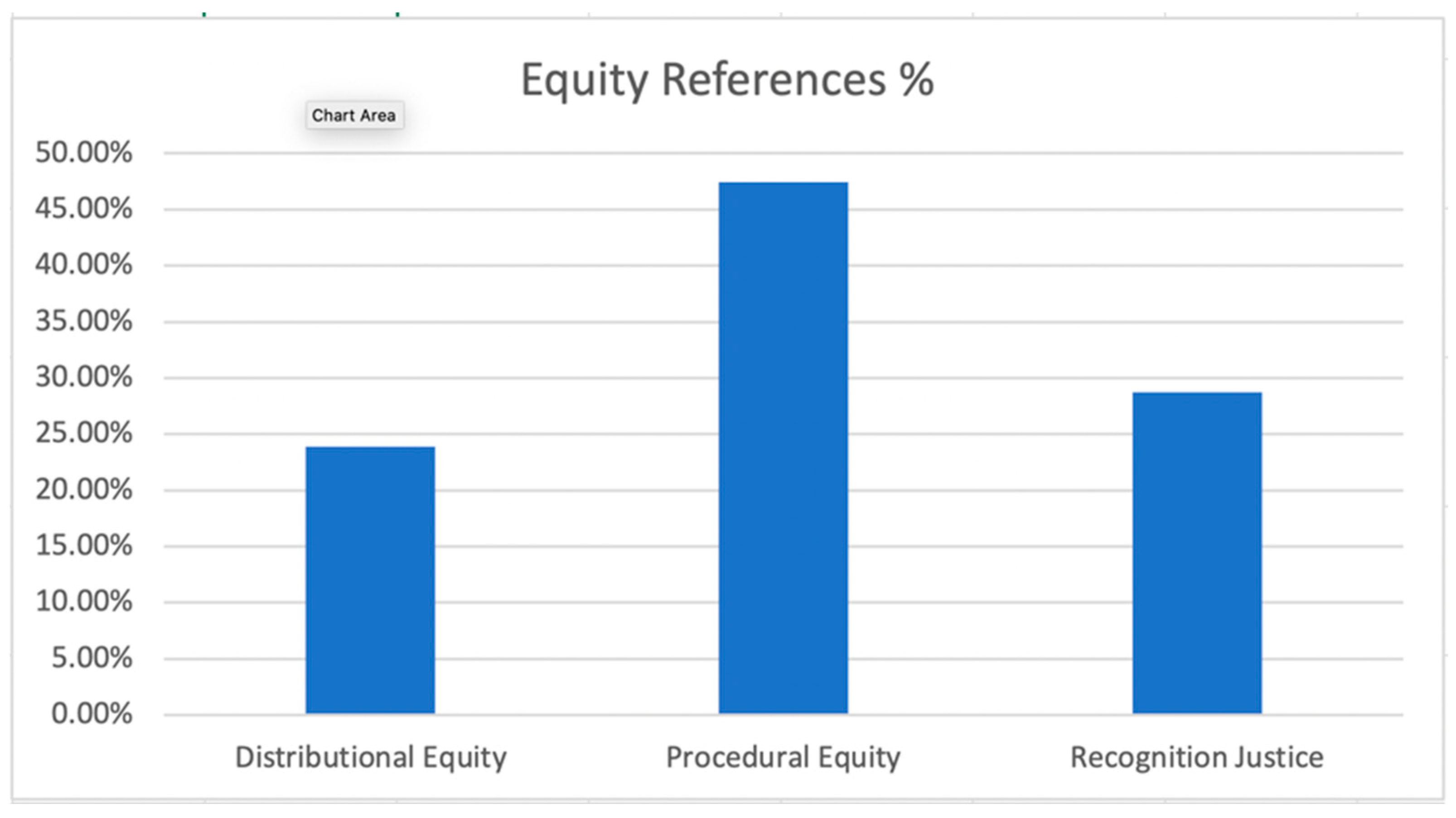

5.2. Does Equity Matter in Resilience Design?

Beyond a reference count on equity, of particular importance in this study is the impact that equity has on specific resilience strategies proposed. Does a plan that came about, for example, through an involved public outreach process that relies heavily on procedural equity lens contain strategies that differ from the plans that recognized historic injustices in the communities in which they are working in, through the lens of recognition justice? While the relationship between the equity framework emphasized in the plans and the resulting resilience strategies is complex, in part because the resilience strategies cannot be neatly categorized and vary substantially from plan to plan, there are two notable plan exceptions where the relationship between recognition justice and a more comprehensive and community-based approach to resilience design strategies is clearer.

Access to employment opportunities and careers, along with access to financial capital and wealth-building opportunities, are given rare attention in the plans. Though jobs are referenced, such references are in light of employment opportunities that are far enough away to prove a mobility burden for residents. An exception is the Islais Hyper-Creek plan in which equity was specifically framed as a function of access to affordable housing and to economic opportunities. Specifically, the plan calls for migrating to ‘clean’ technologies and energy sources that can be coupled with youth education programs, building a long-term local workforce that can participate actively in a green transition economy.

The Our Home proposal is another exception worth highlighting here in that it pays substantial attention on how to create opportunities for North Richmond residents to access financial capital, and provides concrete steps that build on the work of community-based organizations in this neighborhood on how to achieve such access. These steps, which include generating shared homeownership opportunities and offering policies for local hiring practices, also aim to mitigate existing vulnerabilities faced by residents, from increased asthma rates to poverty. Access to homeownership, for example, is presented not only as an affordability issue but also as a means for wealth-building, while shared bicycles can reduce carbon emissions while allowing for greater mobility.

Many strategies in the plans seem to address equity in a narrow sense, insofar as they avoid discussions on how the proposal may lead to further inequalities if not managed properly. For example, all but two of the plans include affordable housing as a fundamental part of an equitable climate-resilient future, and a number of plans even offer concrete steps on how to build affordable housing and open space. Those strategies include active and ongoing engagement with community members on how to best address underutilized land, building community land trusts, and advocacy and training at various institutional scales and agencies. Despite the emphasis on affordable housing, though, only one-third of the plans acknowledge gentrification and displacement as issues that need to be addressed alongside proposals for affordable housing, open space, new infrastructures, and habitat and watershed restorations.

5.2.1. The Design of Engagement

Though each of the plans references equity and community engagement as necessary parts of the process for achieving an equitable resilience future, it is unclear what impact that engagement had on co-creating a framework for generating and assessing resilience design strategies. The disproportionate burden and impact of climate risks is not a matter of individual choice, so to overcome exposure to risk would require a shift in not only voice but in the power to enact resilient and climate just futures that communities envision.

Yet, according to several individuals interviewed for this research, each from different teams, teams were told not to interface with community representatives or organizations during the initial phase of the competition, and were driven to different neighborhoods around the Bay Area on buses. Because of this lack of transparency and communication, residents were confused and upset, particularly when seeing a large number of white people touring and taking notes in communities of color around the Bay Area (Anonymous, personal communication, 7 August 2020). In the second phase of the competition, once teams chose a specific geographic area to work in, team members were encouraged to make connections with residents and organizations working in the communities chosen for their proposals. However, the competition organizers did not facilitate those relationships, nor did they reach out to any of the communities before the competition launch to solicit interest or feedback, or to foster connections with residents and community organizations (Anonymous, personal communication, 24 July 2020).

The implication is that equity concerns are minimized insofar as procedural justice does not guide the design process. Procedural justice has long been established as a fundamental component of working towards more equitable outcomes insofar as its focus on representation and recognition aims to overcome unequal power in decision-making processes [

45,

46] It is also especially critical for climate change responses in that it enables people, especially those who are marginalized and vulnerable to climate risks, to collectively generate and enact decisions over how they and their communities can adapt [

47].

This effort involves a capabilities approach, drawing out and emphasizing existing knowledge, capacities, and experiences of the communities engaged in local climate adaptation as a foundation for responding to climate risks [

48]. Four interviewees in this study, each of whom belonged to a different team, reinforced the need for working with communities to draw out networks, connections, and capabilities. Each agreed this was not enabled by the RbD process, in part because they were not given enough time to engage with the communities before the final design product was to be delivered, and in part because they were not given funds to pay team members and community members for the time needed to engage with community members. When asked about funding, three teams explained that their contribution to the project exceeded what their allotted funding allowed, but that the community members remained unpaid entirely, and one team gave all of the full funds they received by the Rockefeller Foundation to participate in the competition to the community representatives they worked with.

One team member from one of the teams involved questioned the lack of attention the RbD process gave to the infrastructure needed for social resilience:

“everyone talks about ecology and economy, but what did RbD do to strengthen the social dimensions of communities and organizations, to understand what their goals are and who they speak for, and to ensure that the competition resulted in a community-organizing model that could last beyond the RbD process, a community that has power?”

(Anonymous, personal communication, 21 July 2020)

Echoing this loss of opportunity in designing an enduring social resilience proposal, one team member acknowledged two years after the competition had ended that “that project sort of ended and we’re busy working on other things, and it’s been difficult to stay involved and engaged and in touch in a way that I was hoping could be helpful with those communities, to follow their leads and help them get where they want to go” (Conger, K., from Roundtable Discussions webinar, 29 January 2020).

5.2.2. Equity beyond Access

Beyond questions of access to affordable housing and open space, whether these proposals design a process that shifts the power of decision-making to include community members in a way that can persist into the future is unclear at best. However, there are the beginnings of such aspirations in some of the plans. The Our Home group worked with local residents and community-based organizations to create a Citizens Advisory Board, mentioned earlier in this article, to become the leading entity driving the RbD effort, as well as the North Richmond Living Levee group, a working group responsible for addressing wastewater and shoreline management. According to an interview with one of the team architects, throughout the process the team members, in partnership with these newly formed organizations and existing ones, worked on funding mechanisms that could resist gentrification. A member of a prominent community-based organization explained in an interview that they continue to work with the Our Home design team members, collaborating on future financing opportunities for implementing the visions outlined in the plan.

The Estuary Commons team also worked extensively to build relationship with community-based organizations, residents, and agencies to implement adaptation strategies. Their work highlighted community-led investments as pathways for socioeconomic equity, acknowledging the responsibility of designers to shift the conversation surrounding equitable design to incorporate longer-term implementation strategies that could help shift power relations on behalf of vulnerable populations. In an interview with the team’s members, it became clear that “everyone understood that the issues of finance and governance need to lead—we can find solutions to the landscape problems but we won’t be able to do any of that unless we address underlying structures.” One of the drawbacks of the RbD process that they, and two other teams, described was that the process of pairing the design group with the community they designed for did not allow for a co-creative process to take place. In part this had to do, all teams interviewed agreed, with the time restriction given to the designers and in part with the lack of funding for community members to participate in the design process. This sense of urgency is paradoxical given the long-term nature of the climate-related problems taken on by these design visions, but can also prove useful insofar as some of the short-term strategies in the plans can be implemented with relatively fewer obstacles in the near future, and can then jumpstart associated proposals that require more time and resources.

The People’s Plan team also framed equity as an issue beyond access to housing and open space. Members of the team described how their work centered on strengthening community advocacy through ecoliteracy, which they define as an understanding of how ecological functions are integrated and connected to each other, thereby offering additional economic and material benefits (The People’s Plan, 14). Their efforts were founded on a mutual long-term vision that the team and community came up with, which involved enabling community members to take ownership of implementing their version of a climate-just future driven by self-determination. Promoting advocacy took the form of system thinking and building capacity training, while ecoliteracy was driven by permaculture tenets: ethical boundaries, integrated functions, pattern to details, small and slow solutions, and diversity and redundancy. The team members and community stakeholders took on permaculture as a model for these efforts. In the plan they describe permaculture as a design system based on Indigenous practices incorporating ecosystem knowledge and human needs, and emphasize the need to build capacity in this community by addressing defining characteristics of permaculture design. Namely, a care of people and the earth, limits to consumption, integrated eco-based strategies with multiple benefits, efficient design and implementation strategies, small and slow solutions, and diversity and redundancy (The People’s Plan, 14).

The People’s Plan proposal does not involve design in the traditional architectural or urban design sense of formulating a vision for a specific place or region. Instead, the plan calls for reconceiving design itself. It proposes a framework that can be adapted to the specific aspirations of a community that has been denied access to general or specific planning as a result of structural discrimination and oppression:

“… an unconventional approach—a social design process to build community capacity and ecoliteracy to address the challenges of coastal adaptation and resilience planning, especially in vulnerable communities that have experienced generations of marginalization and exclusion”

(The People’s Plan, 3)

The public determined their own vision, risk assessments, strategies, and timeline for addressing coastal adaptation and flooding issues. The People’s Plan puts forth the Community Partnership Process meant to identify local leadership, promote education, and build social capacity through a series of six steps: listen and asset map, assess and strategize, propose–discuss–feedback, establish a plan with phasing, implement aspects of the plan, and review and recalibrate. According to an interview with one of the leading members of the team, the RbD organizers resisted this proposal, questioning repeatedly who the designers on the team were and where the design was. The team explained to the competition organizers that The People’s Plan was a process that the community of Marin City owned, and that after the competition would close the organizers would need to continue funding and supporting this effort. Such an effort did not ultimately materialize. Though the plan makes clear that the steps for building capacity involve giving participants the tools they need for designing their own solutions, for developing their own planning strategies, and for interacting with more ease with external organizations and government institutions, Marin City remained a pilot study.

Equity is referenced in each of the plans either directly, through statements that foreground its importance in conceiving of climate just and resilient futures, or indirectly, through strategies proposed that promote equitable access to housing and amenities. However, despite the fact that inequalities in these communities are a result of ongoing and structural discrimination, only one-third of the plans acknowledge structural racism or discrimination as a fundamental aspect of the resulting social and environmental injustices faced by the communities in which the proposals take place. One team member, part of a team whose proposal identified racial segregation as a fundamental factor in lingering environmental and social injustices pervaiding their selected neighborhood, explained in an interview that the team kept returning to the question of whether resilience design continues to ask communities of color to keep enduring these inequalities (Anonymous, personal communication, 24 July 2020).

Both The People’s Plan and the Our Home plans took on racism and discrimination directly and used the resilience proposals to highlight the importance of self-determination as an act of resistance. These two plans expanded how design could empower community members by transferring knowledge and skills to their publics so they could develop their own strategies to address short and long-term climate change impacts in their communities. Conversely, beyond highlighting access to new resilient landscapes, the plans that did not take on issues of racism and discrimination directly did not capitalize on the power of design to lay the foundation for uplifting vulnerable communities in ways that allow for ongoing and persistent self-determination.