Abstract

Cultural landscapes encompass a diversity of manifestations of the interaction between humankind and the natural environment occurring in both space and time. In some instances where the human occupation of a specific area or region encompass a continuous and extended timeframe, successive cultural layers yield contrasting and disparate landscapes and heritage values. This “layering” of past cultural landscapes often leads to conflicting modern-day land, cultural resource management, and heritage value issues. A case study is presented from the Hanford Site in south-central Washington state, USA, where the natural landscape comprises prehistoric Native American, historic ethnographic, and historic period non-Indian evidence from over 10,000 years of occupation and use that clearly separate into several culturally and chronologically defined and overlapping cultural landscapes, which can be visualized as layered entities occurring on the same physical space.

1. Introduction

In 1992, the UNESCO World Heritage Convention internationally codified the term “cultural landscape” as embracing a diversity of manifestations of the interaction between humankind and its natural environment, further defining the concept as those places where human interaction with natural systems has, over a long time, formed a distinctive landscape. Three categories of cultural landscapes were established, including clearly defined landscapes, organically evolved landscapes, and associative cultural landscapes. The organically evolved landscape has two sub-categories: the relict landscape and the continuing landscape [1]. These categories and the various criteria employed to place cultural landscapes into one or another category were largely advanced to support the designation of such landscapes as “World Heritage Sites”. The UNESCO categories are further defined as:

- Designed cultural landscapes, often gardens or parks that are the work of a single designer or period, and that have clear aesthetic intent are sometimes) associated with religious or other monumental buildings.

- Evolved cultural landscapes, which are the result of a gradual adaptation of a community to an environment, often through many generations, and that may be continuing (if still active) or relict (if no longer inhabited or active).

- Associative cultural landscapes, which have powerful religious, artistic or cultural associations and which may have little material culture evidence.

In the United States, the U.S. National Park Service defines a cultural landscape as “a geographic area, including both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife or domestic animals therein, associated with a historic event, activity, or person or exhibiting other cultural or aesthetic values”. The National Park Service further differentiates cultural landscapes into four categories [2]:

- Historic designed landscapes—a landscape that was consciously designed or laid out by a landscape architect, expert gardener, architect, engineer, or horticulturist according to design principles, or an amateur gardener working in a recognized style or tradition.

- Historic vernacular landscapes—a landscape that evolved through use by the people whose activities or occupancy shaped it.

- Historic sites—a landscape significant for its association with a historic event, activity or person.

- Ethnographic landscapes—a landscape containing a variety of natural and cultural resources that associated people define as heritage resources.

Following National Park Service guidelines, proper identification of a cultural landscape includes documentation, analysis, and may involve evaluation of historical, architectural, archeological, ethnographic, horticultural, landscape architectural, engineering, and ecological data. Such studies are interdisciplinary in nature. Cultural landscapes can be nominated to and listed in the National Register of Historic Places, either as historic properties or historic districts, when their significant cultural values have been documented and evaluated within appropriate thematic contexts, and physical investigation determines that they retain sufficient integrity.

In many situations, one or more of these National Park Service-defined cultural landscapes may occur together, intersecting in spaciotemporal patterns. These “multilayered cultural landscapes” are the products of the reciprocal interaction between the natural environment, people and culture, accompanied by a continual historical development process. Such is the case at the expansive Hanford Site in Washington state, USA, where several successive yet markedly diverse cultural landscapes are apparent, all superimposed on the same physical setting.

When dealing with multilayered cultural landscapes, particularly those with an extensive time depth accompanied by successive eras of differential human occupation and patterns of use, it is oftentimes difficult to imagine and demarcate the complexities of sequential, uninterrupted, and sometimes overlapping cultural landscapes. The primary goal here is to offer a graphic template for separating and defining, both chronologically and culturally, distinct cultural eras occurring on the same terrain, first by separating the layers into definable eras and cultural contexts and then by offering a visual depiction of the intermingling of each layer’s historic properties in a given locale. This essay concisely defines a cultural landscape framework for the Hanford Site, suggesting that the place is best viewed conceptually as a spatial cultural landscape mosaic; one that shows a multifaceted “layering” of temporally distinct and unique cultural patterns. In some instances, it is further possible to both differentiate and evaluate the effects of the in situ, sequential transitioning from one cultural landscape layer to another.

2. Background

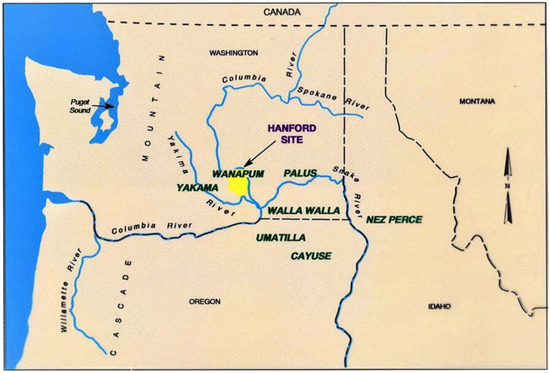

The Hanford Site is situated in south-central Washington state, encompassing an area of nearly 600 square miles (1544 square kilometers) (Figure 1). The site is owned by the federal government, administered by the U.S. Department of Energy, Richland Operations Office. The tract lies in the Pasco Basin of the southern Columbia Plateau, immediately north of the confluence of the Columbia River with the Snake, Walla Walla, and Yakima rivers. The origin of the Hanford Site began in 1943 when the area was selected by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Manhattan District as the location for the nation’s first full-sized plutonium production reactors. Today, after several decades of participation in the defense nuclear materials production programs the Hanford Site has entered an era of remediation and environmental restoration, along with emphasis on nonmilitary applications of nuclear energy.

Figure 1.

The Hanford Site (yellow) is situated in south-central Washington state. The general locations of historic American Indian Tribes with cultural ties to the Site are indicated in dark green lettering. Of these, the Wanapum, a non-federally recognized group, have the most direct geographical and cultural connections with the Hanford Site environs, both in earlier times and today.

The physical landscape that encompasses the Hanford Site is the byproduct of a complex geologic record of late Pleistocene catastrophic flooding and provides a backdrop for a cultural landscape setting that includes the rich, enduring legacy of native peoples, traces of early Euroamerican settlement, and abundant manifestations of the industrial developments associated with the more recent Manhattan Project and Cold War era. Public access to the Hanford Site was greatly restricted since acquisition of the land by the U.S. Government in the early 1940s. This closure, along with the fact that the last free-flowing stretch of the Columbia River, designated as the “Hanford Reach” passes through the Site, has meant that the natural and cultural resources of the Hanford Site have been largely protected from major impacts common to other areas along the Columbia River corridor, such as dams and reservoir pools, extensive urban and agricultural development, and recreational activities.

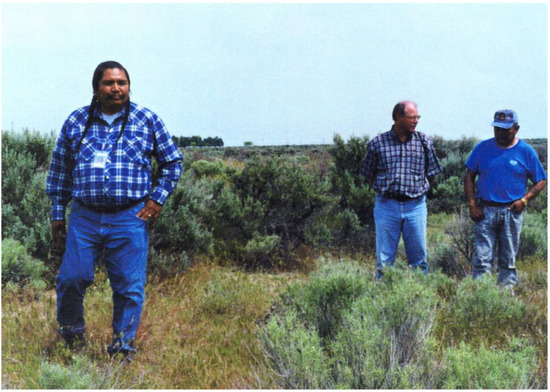

The recent shift in primary mission at the Hanford Site has created a complex suite of issues that call for meaningful decisions on the future of this fragile semiarid landscape that has enjoyed a relatively secure and protected status since 1943. Critical for cultural resource management in this set of essential decisions are those issues related to questions concerning topics such as proper cleanup scenarios, potential future uses of the lands [3], much of which simply served as historically untouched buffer zones for the nuclear production facilities, and continued protection of the Hanford Reach of the Columbia River [4]. Potential players in the long-term scenario regarding the future of the Hanford Site landscape include a multitude of federal, state, and local governmental agencies, several Indian tribes, many private entities, and members of the general public. Significant issues being worked at this time include topics such as not only who but what level of federal, state, local, or even private control will be exerted on which portions of the site, and what types of actual land use and associated impacts will be allowed throughout the area. In the case of American Indian tribes, consultation—a formal, two-way, government-to-government dialogue between official representatives of tribes and federal agencies—is required to discuss federal proposals before the agency makes decisions on those proposals involving potential effects for tribally significant resources and places from cleanup activities, including plans for future land ownership and use (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The author (center) engaging in field consultation with Wanapum Elders, August 2008. The man at the right, who has since passed, had the dual distinction at the time of being the last living Wanapum person who was actually born within the Hanford Site boundaries and the last full-blooded member of the tribe (Source: Nickens).

3. Methodology

Information and data supporting this study accrued between 1987, when the U.S. Department of Energy, Richland Operations Office, initiated a formal cultural and historic resources program at the Hanford Site, and 1999. The 1989 completion of the “Hanford Cultural Resources Management Plan” formalized a sitewide effort to identify, document, evaluate, and protect all cultural resources within the Hanford boundaries, including prehistoric, historic, and traditional use areas and sacred and religious places that are culturally significant for the region’s indigenous tribes [5]. A principal goal of this program, in addition to meeting the requirements of applicable federal and state historic preservation laws and regulations, involved consultation with tribes, other descendant groups, and interested parties through government-to-government interactions when necessary and, if needed, technical-level consultation, including onsite, when appropriate.

In the early 1990s, the Department established the “Hanford Tribal Program” to interact with potentially affected American Indian tribes, including three federally recognized tribes affected by Hanford operations, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, and the Nez Perce Tribe. Those tribes were found to be “affected” through application under the U.S. Nuclear Waste Policy Act (1982) based on the potential affects to treaty rights and resources. In addition, the Wanapum people, who still live near Hanford at Priest Rapids, are a non-federally recognized tribe who have strong cultural ties to the site and have consulted with DOE since its formation in the 1940s. Regular tribal issues meetings between Hanford cultural resource managers and these four tribes began in 1993, leading to an immediate active tribal cultural resources involvement in the current and long-term stewardship of the Hanford Site.

Members of the present-day tribes identified above have a special relationship to the lands within the Hanford Site boundaries because their ancestors resided there for several millennia before the non-Indian occupation. Some of the Native Americans who formerly occupied and interacted with the physical landscape and natural resources there believe that they were created on this landscape, and that the Creator gave them special responsibility to protect and oversee the land and its resources. This is especially true for the Wanapum, who believe this landscape to be their ancestral homelands. Although many individual places and resources of critical heritage value can be identified on this terrain, the tribes view the entire landscape in its totality to be of high significance.

The initial stages of implementation of a large-scale identification, recording, and evaluation of historic properties effort, accompanied by consultation and direct involvement of tribes and other interested parties, yielded a considerable database for an extensive history of land use on the Hanford landscape. This endeavor in turn led to identification of series of successive cultural landscapes occurring across the physical space [6]. Included in this inventory were over 1200 prehistoric and historic era archaeological sites, about 525 Manhattan Project & Cold War Era Buildings, and seventeen archaeological and/or cultural districts.

4. Cultural Landscapes at the Hanford Site

The cultural landscape approach recognizes the interconnectedness of physical places, natural resources occurring there, and the cultural meanings assigned by inhabitants to those heritage resources. Landforms and natural resources of the Hanford Site hold several cultural meanings for each of several diverse groups of people or individuals. For Hanford’s cultural landscapes to be delineated as fully as possible, the definitions must be built upon information gained through place- and resource-specific studies designed to capture cultural meanings as they are perceived and understood by the viewer or viewers. As outlined below, a sequential cultural landscape scenario is offered that encompasses the totality of spatial and temporal dimensions for the Hanford Site.

4.1. Native American Cultural Landscape

While in reality it represents a continuum, Native American occupation and associated activities on the Hanford landscape can be broken into two periods for analytical examination. The first is the prehistoric, or archaeological setting, which runs from about 10,000 years ago to the first regional contact by the Lewis and Clarke Expedition in 1805. The next ethnographic or contact period extends on from 1805 to early 1943, when the few remaining members of the Wanapum Tribe were informed by the U.S. Government that they would no longer be able to continue to use this part of their traditional homelands as they were accustomed to in former times.

4.1.1. Prehistoric Period of the Hanford Site and Associated Portion of the Columbia River, Circa 10,000 B.P–A.D. 1805

Past archaeological investigations on lands contained in the Hanford Site have resulted in the recording of nearly 500 prehistoric archaeological sites, although the actual percentage of the Site that has been systematically surveyed is limited. The site density is expectedly much higher along the Columbia River corridor where several National Register of Historic Places Districts have been designated. Commonly occurring archaeological site types include habitation or village sites, animal, plant, and fish procurement localities, sites showing natural resource processing activities, features and places believed to be associated with religious, burial, and ceremonial activities, and trails.

4.1.2. Ethnographic/Contact Period of the Hanford Site (Lewis and Clark 1805–Hanford Engineer Works 1943)

The principal aboriginal group occupying and using the lands included in the present-day Hanford Site was Wanapum Tribe that formerly lived along the Columbia River from above Priest Rapids down to the mouth of the Snake River in what is now the U.S. state of Washington. The name “Wanapum” is from the Sahaptin language word wánapam, meaning “river people”, from wána, “river”, and -pam, “people”. While other regional tribes visited this section of the river valley for social intercourse, trading—particularly for dried salmon—and similar activities, it was widely recognized that the village places and fisheries belonged to the Wanapum in both pre- and post-contact times.

The initial contact between the Wanapum and Euroamerican explorers was documented in some detail, including observations on Wanapum culture, customs, and vocabulary. On 16 October 1805, the legendary Corps of Discovery Expedition, led jointly by Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark, finally reached the Columbia River at a point near the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers, just southeast of the Hanford Site [7]. Not far upstream was a large Wanapum encampment (Lewis and Clark called them “Sokulks”) of several hundred people who were in the area for the autumn salmon run.

The first evening, some 200 Wanapum men under the leadership of a man named Cutssahnem, entered the American’s camp, beating drums and singing. After the obligatory smoke and speeches, the expedition ended the festivities by purchasing eight fat dogs, some dried salmon, and twenty pounds of dried horsemeat. The following morning, while Cutssahnem and several of his principal men traded additional dogs and vocabulary phrases with Lewis, Clark took two men in a small canoe for a short reconnaissance up the Columbia, encountering mat-lodge fishing villages and drying scaffolds along the banks. At one cluster of lodges, Clark stopped for a closer look. In one house he found a busy crowd of men, women, and children. Seemingly unafraid of their uninvited guest, the Wanapam politely offered Clark a sitting mat and some boiled salmon “on a platter of rushes neetly made”. As Clark enjoyed his meal and the good company, he took careful note of his hosts’ clothing, manners, and physical characteristics.

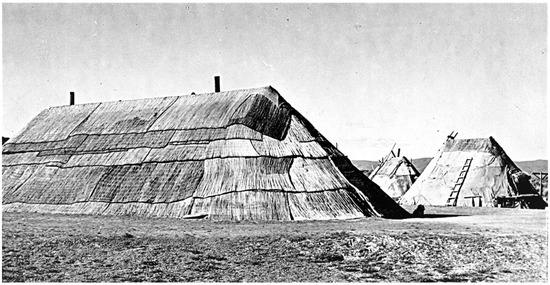

The ensuing historic Native American presence on the Hanford landscape reflects continuous intensive use of the much of the geography since 1805. As noted, native people were using areas and natural resources within the Hanford Site right up to the 1943 taking of the land by the federal government, overlapping and co-existing with white settlers for the previous 40–50 years (Figure 3). At the time of the initial contact, estimates of the Wanapum population at the time were as high as 3000. By 1943, the tribe’s number had dwindled precipitously, basically four extended families numbering between 25 and 30 individuals, primarily due to the effects of introduced diseases throughout the nineteenth century. Although Indian people were until recently mostly prevented from entering and using traditional sites and resources within the Site, associated heritage values have always remained significant among members of the Wanapum Tribe and for other regional tribes.

Figure 3.

The Wanapum winter village (called P’na) at Priest Rapids situated just outside the west edge of the Hanford Site, as photographed in 1930. The religious long house structure at the left and the smaller winter lodges were constructed of woven and sown rectangular tule reed mats overlying a wooden framework. By this time, the addition of canvas to the exterior of the living houses added extra protection from the harsh winter elements (Source: Relander Collection, Yakima Valley Library, WA).

Owing to the extraordinary time depth of continuous American Indian presence on the Hanford landscape, innumerable places of cultural and religious significance are known to be present. As accrued from Wanapum Elders over the years, and from those of other regional tribes, a broad array of such places and traditional values are widely distributed across the entire landscape, including many places with multiple levels of meaning (Figure 4). Some of the more significant of these include:

- Mountains and upland areas

- Springs (some hot and evil smelling)

- Former camp sites and villages

- Fisheries and fishing camps, primarily for fall chinook salmon

- Islands

- Trails, pathways, and passes

- Places that were uninhabitable

- Plant gathering areas and hunting grounds

- Cemeteries

- Driftwood collecting places along the river, critical for wintertime in a generally treeless terrain

- Traditional holy lands, including:

- ○

- Places associated with legends and myths

- ○

- Places of religious activities (e.g., Washat dance sites and first salmon or first foods ceremonial sites)

- ○

- Vision quest places

- ○

- Other ritual or ceremonial locations

- Mineral procurement places

- Rock paintings and pecked designs

- Dwelling places of the spirits

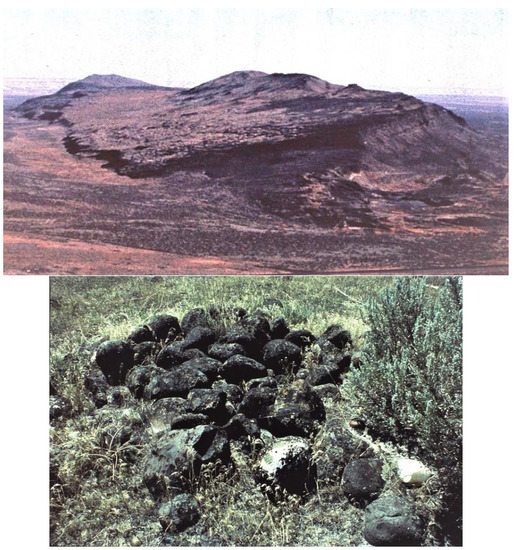

Figure 4.

Located in the central part of the Hanford Site, Nooksiah (otter), today called Gable Mountain (top), plays an important part in the regional origin myth. Located within easy walking distances of former Wanapum villages along the river, this upland was also a principal place for spirit or vision quests. These places where Wanapum youth gained guardian spirit powers in order to gain strength for a successful life are frequently marked by stone cairns (bottom) [8] (Sources: U.S. Department of Energy).

Figure 4.

Located in the central part of the Hanford Site, Nooksiah (otter), today called Gable Mountain (top), plays an important part in the regional origin myth. Located within easy walking distances of former Wanapum villages along the river, this upland was also a principal place for spirit or vision quests. These places where Wanapum youth gained guardian spirit powers in order to gain strength for a successful life are frequently marked by stone cairns (bottom) [8] (Sources: U.S. Department of Energy).

4.2. The Euroamerican Settlement of the Hanford Site (Lewis and Clark 1805–Hanford Engineer Works 1943) Cultural Landscape

Following intermittent and generally brief probing intrusions into the Hanford area by explorers and miners after 1805, non-native settlement of the area began to gain a foothold in the 1880s, first by cattle ventures and then followed by more intensive homesteading and town building efforts, primarily adjacent to the banks of the Columbia River (Figure 5). In the early 1900’s, land speculators began constructing large-scale, privately funded irrigation canals to supply water to thousands of acres in the towns of White Bluffs, Hanford, Fruitvale, and Richland [9,10]. As of 1943, there were some 2300 non-Indian people living in the towns and unincorporated agricultural lands along this part of the Columbia River valley; nearly all of whom would soon be forcefully displaced by the federal government. The town of Richland fell just outside the southern boundary of the government’s newly designated reserve and was not affected. Residents were given anywhere from 30 days to 90 days’ notice to vacate their homes. Due to secrecy, the government vaguely explained to residents that the land was needed for a new military wartime project.

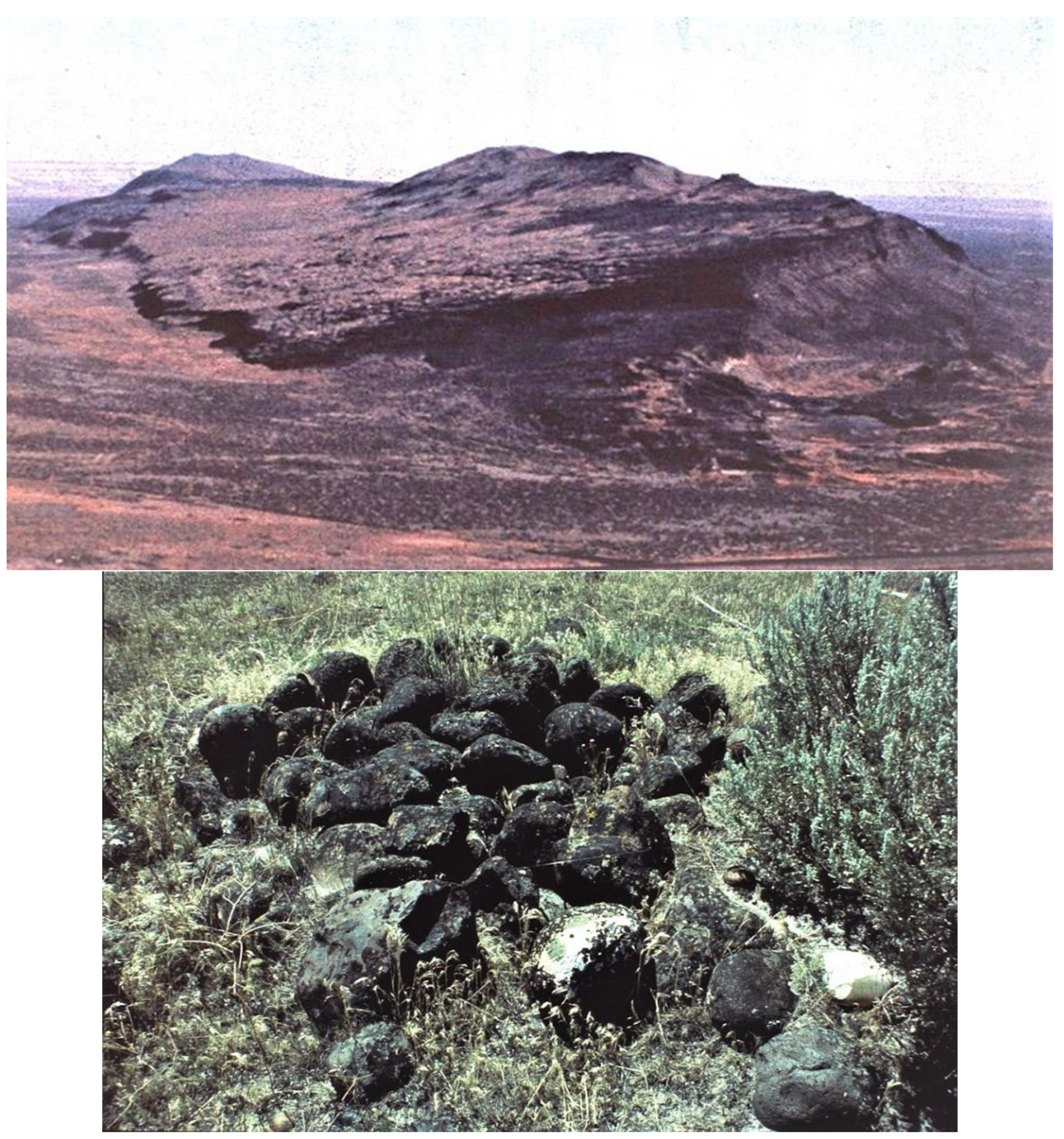

Figure 5.

Early settler’s homestead on land that would later become the Hanford Site (Source: U.S. Department of Energy).

Although somewhat changed by post-1943 construction and other land-altering actions, particularly the razing of nearly all standing historic architecture, considerable evidence of the historic pre-nuclear period is still present on the Hanford landscape as historic archaeological sites. In addition to former homestead and ranch locations and townsites, other major site types include traces of orchards and fields, transportation routes, and irrigation systems.

The Wanapum, along with other regional tribes who on certain occasions visited places along the Columbia, continued various forms of social intercourse and barter with the homesteaders, especially in the fall months when the Wanapum were temporarily encamped at their usual fishing place (Figure 6 and Figure 7) near the prominent White Bluffs. Settler neighbors oversaw the safety of camp and fishing gear stashed in storage areas hollowed out in the riverbanks while the Wanapum were away for the most part of the year, even offering storage of the Wanapum fishing canoes in their yards for additional security. With the late summer and early autumn field and orchard harvests coinciding with the Wanapum fishing time, considerable trade was realized back and forth for foodstuffs of a different nature [11].

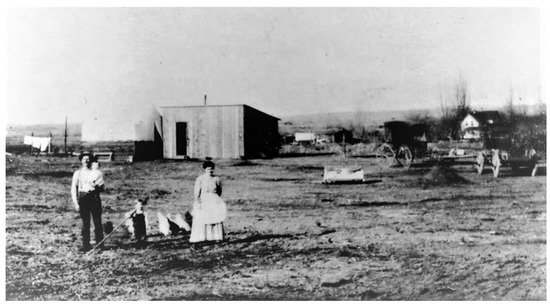

Figure 6.

This pre-1943 image depicts the transition and overlap between the Contact Period Native American and Euroamerican Settlement cultural contexts prior to establishment of the government’s Hanford Site. A Wanapum fall chinook salmon fishing camp (Wy-yow-na) on the fluvial gravel deposit bar along the Columbia River’s edge is apparent in the foreground while a settler’s homestead is evident above the bank face. The White Bluffs (Tacht) are visible across the river at the right center of the image. Prior to 1943, this camp and adjacent fishery were used annually by the Wanapum to catch and prepare salmon foodstuffs for the upcoming winter months that were, at that time, spent in the winter village at Priest Rapids, some twenty miles upriver. (Source: U.S. Department of Energy).

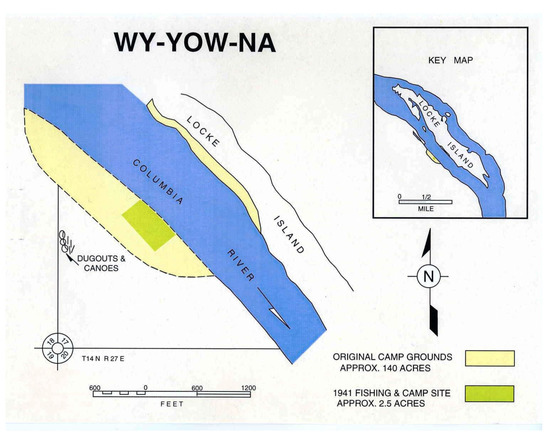

Figure 7.

The Wanapum usual and accustomed encampment and fishery at White Bluffs, as mapped in 1941 [12]. The reduction in size of the fishing and camp site from earlier times is correlated with the decline of the Wanapum population numbers.

4.3. The Manhattan Project and Cold War Eras—Plutonium Production at the Hanford Site, 1943–1990, Cultural Landscape

The Manhattan Project and Cold War Era is comprised predominantly of industrial buildings and structures associated with plutonium production, military operations, research and development, waste management, and environmental monitoring activities that took place beginning with the establishment of the Hanford Site (Hanford Engineer Works) from 1943 to the end of the Cold War in 1990. (Figure 8) [13]. Historic properties associated with this period are distributed throughout the Site according to a unique historical site layout plan and can be categorized into the following groupings:

- Plutonium production facilities

- Military defense facilities

- Utility and maintenance facilities

- Administration, Site security, health and safety facilities

- Non-defense facilities

- Communication and transportation networks

- Environmental monitoring facilities

- Waste treatment and fresh materials treatment facilities

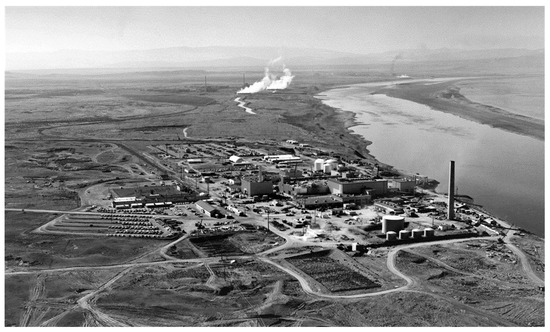

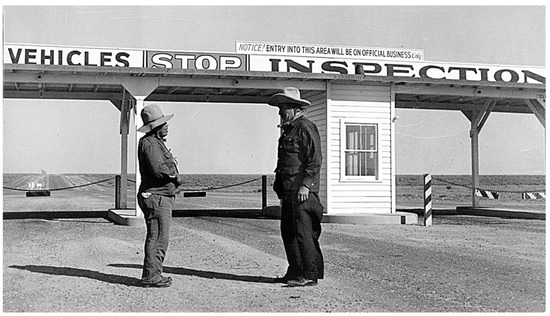

Figure 8.

Nuclear reactors line the riverside sector at the Hanford Site along the Columbia River in January 1960 (Source: U.S. Department of Energy).

Figure 8.

Nuclear reactors line the riverside sector at the Hanford Site along the Columbia River in January 1960 (Source: U.S. Department of Energy).

4.4. Modern-Day Hanford, 1990–Present

The modern-day Hanford Site is focused on decommissioning, demolition, and environmental cleanup efforts; a cultural landscape setting is not defined for this timeframe.

5. Wanapum Displacement

Through the first several decades of the twentieth century, Wanapum people lived at their village at the lower end of Priest Rapids, as their numbers continuing to decline. They peacefully co-existed with the small population of white ranchers and farmers who lived in the area. Horses were grazed on the steep hills to the west. Salmon were still caught at the traditional fishing grounds at Priest Rapids, White Bluffs (on the soon to be designated Hanford Site), and at the Horn, or Wanawish, located on the Yakima River, ten miles above its mouth and just outside the Hanford Site boundary. Some of the Wanapum traveled to the north to Soap Lake, Washington vicinity in the spring to visit friends and gather roots such as solkulk and bitterroots. Wanapum families also traveled to various nearby locations to seek seasonal wage labor, including the Yakima Valley where in the spring white farmers hired them to train hops vines.

With the 1943 taking of the land by the government, the Wanapum lost the freedom to access to their traditional fishing areas and other areas and resources of historic and customary use. The also lost the ability to protect several cemeteries that were found on some islands and ridges. Access to the Site was at first restricted and regulated by passes and guard escorts; then revoked altogether as security for the Hanford Site became more of a concern when the country entered into the Cold War era in the early 1950s (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

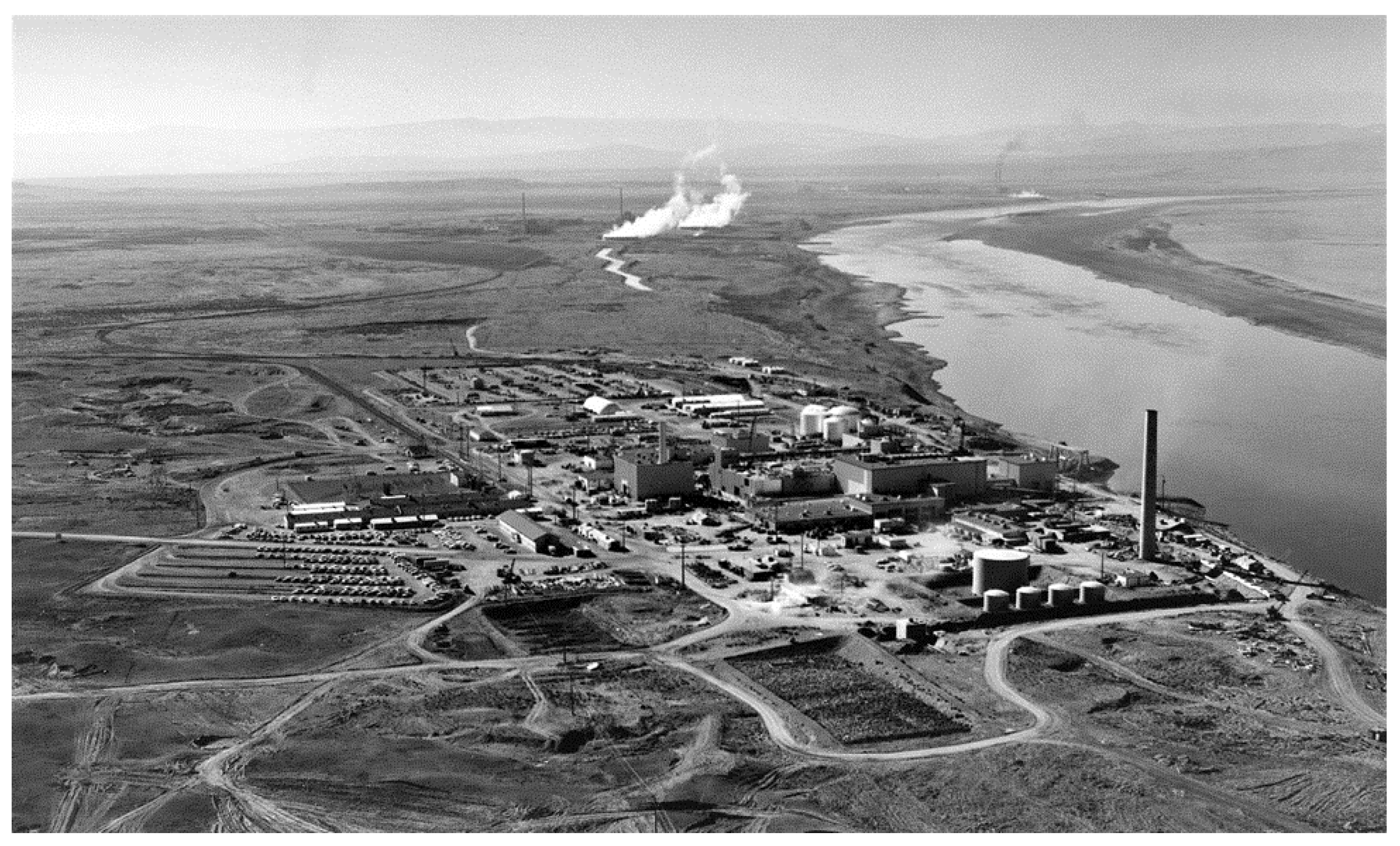

Figure 9.

Although they received no compensation for the land or the loss of access to natural resources, the Wanapum were initially given visitation rights that allowed them to camp, hunt or fish in the Hanford area. Wanapum Chief Johnny Buck met with Colonel Franklin Matthias to negotiate his tribe’s rights, Matthias telling Buck that he would “arrange to take your people up to the White Bluffs Island every morning by truck to do your fishing. We will bring you back by night or in some cases maybe you can stay there overnight”. Issues with this arrangement soon arose. Buck sent a letter to Matthias to “detailing the Manhattan District’s failures” in the winter of 1943. The result was a meeting at the Wanapum Spring Festival on 2 April 1944. In an agreement with Buck, Colonel Matthias arranged for a series of passes to be issued to the tribe [14]. (Source: Relander Collection, Yakima Valley Library, WA).

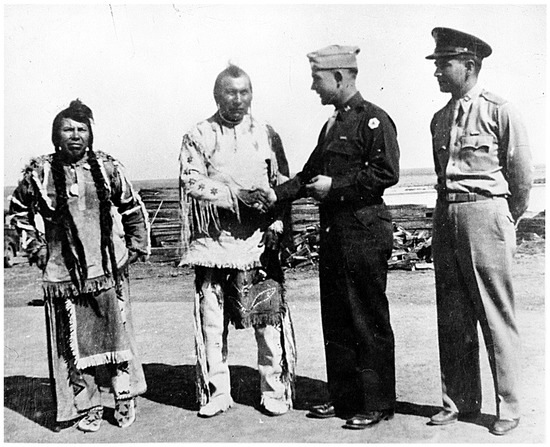

Figure 10.

This photograph, taken on 7 April 1951 at the barrier to the Hanford Site by Yakima, Washington, journalist Click Relander, appeared in an 11 April 1951, Yakima Daily Republic headline story on the Wanapum and their desire to maintain their former homelands along the Columbia River, including much of the Hanford Site. The two Wanapum men are religious leader Johnny Buck (Puck Hyah Toot), (1878–1956) (right) and Johnny Tomanawash (To Mala Wash) (left), who that day had taken Relander and two others on a tour of Wanapum cemeteries in the vicinity of Priest Rapids. While the photographic view embodies the plight of the Wanapum desiring to be able to return to their former lands, the taking of the photo actually had a more practical objective. In 1943, the Corps of Engineers Manhattan District had given the Wanapum a letter granting them access to the northwestern part of the Site to camp, fish, and collect firewood. According to Mr. Relander’s notes from the trip, Mr. Buck indicated that security guards had recently given the Indians trouble concerning the access, and the Wanapum “wanted a picture taken and sent to the guards so they would know who they were dealing with” [15] (Source: Relander Collection, Yakima Valley Library, WA).

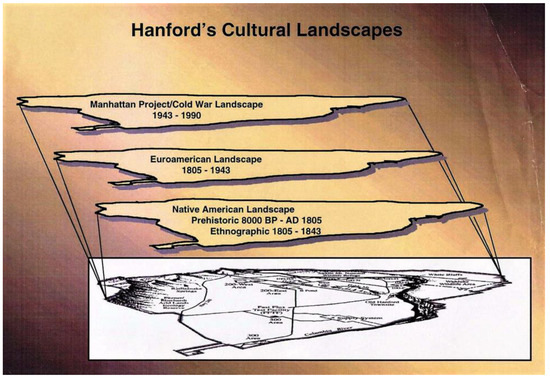

6. A Template for Visualizing the Successive Hanford Cultural Landscapes

Oftentimes, achieving a straightforward technique for graphically conveying cultural landscapes, particularly when dealing with layered ones, is challenging. Here, we created two graphic depictions to reflect: firstly, the layered cultural landscape conceptual framework for the Hanford landscape; and secondly, a visual technique for identifying resources, both readily evident and more intangible at specific locales within the overall physical setting.

The Hanford Site adapts well to a conceptual framework of “cultural layers” that “blanket” the physical landscape—each layer with a dominant cultural theme, each layer blending with the others at the chronological and spatial boundaries, all comprising nearly a complete record of past and present activities and events (Figure 11). As such, Hanford offers an exceptional opportunity to investigate the challenge of managing and protecting multiple, overlapping cultural landscapes. Here, the open, spacious landscape, industrial architecture, and buried archaeological record hold the material cultural of all of Hanford’s earlier occupants, including Native peoples, Euroamerican settlers, military personnel, the massive Manhattan Project undertaking, and the later Hanford work force engaged in the production of plutonium [16].

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of the chronological layering of cultural landscapes at the Hanford Site.

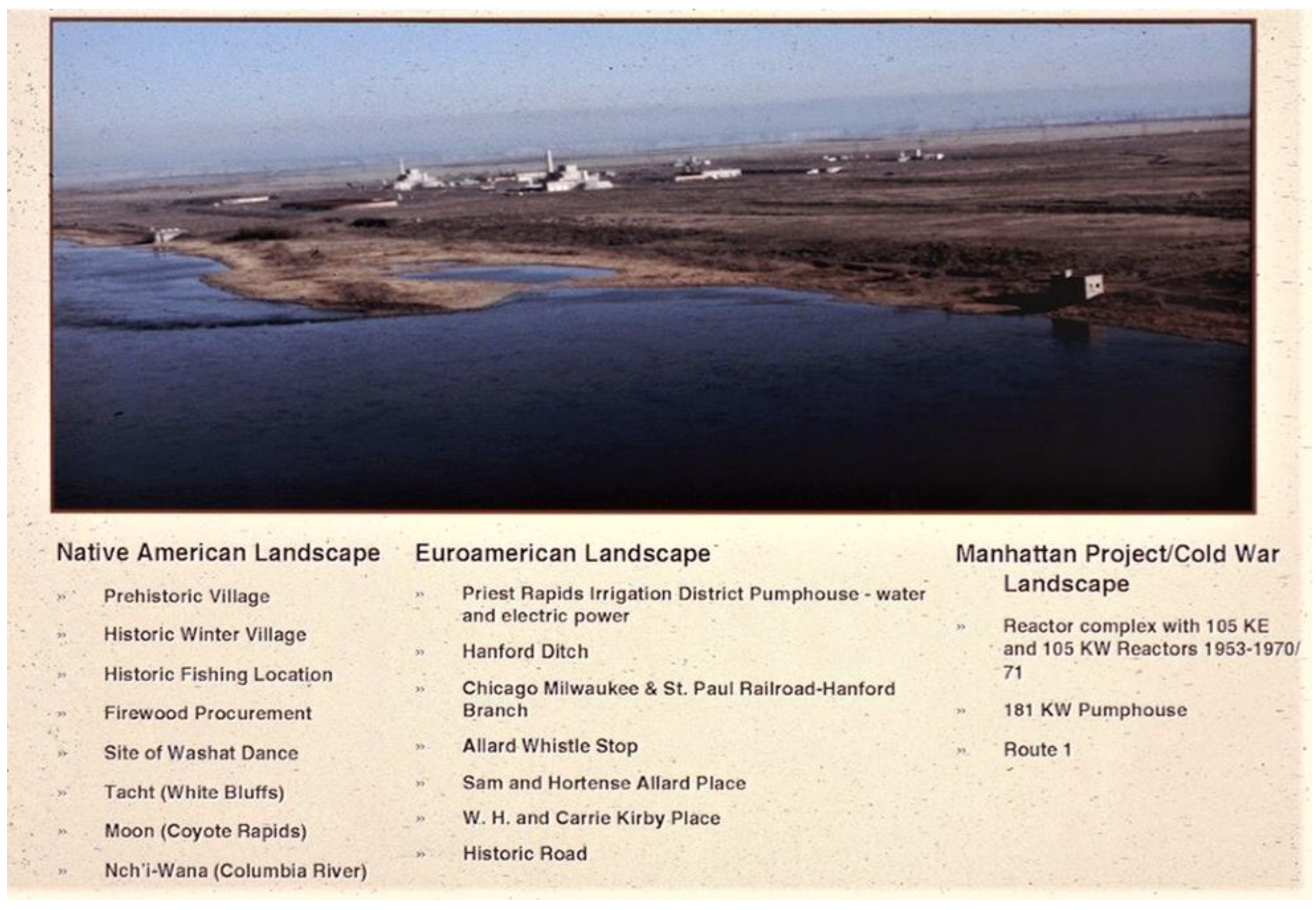

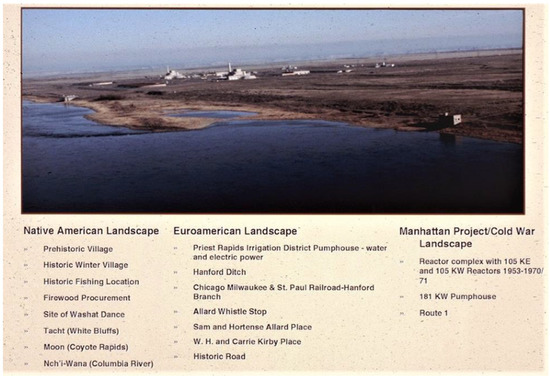

The overlapping nature of these temporally distinct cultural landscape layers is revealed differentially throughout the Hanford Site—with several kinds of endeavors reflected for each layer of the overall prehistoric and historic cultural landscape continuum. Figure 12 illustrates an example from the Coyote Rapids area on the Columbia River where numerous places associated with past cultural behavioral activities can be recognized, although some would not be plainly discernible on the ground were it not for either documentary or ethnographic confirmation. The intermingled mosaic of human activities at this locale includes prehistoric and historic Native American properties, Euroamerican settlement era sites, and post-1943 Hanford era plutonium production facilities and appurtenant features (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

At this locale along the Columbia River, numerous places of historical cultural significance—some easily perceptible and others intangible—are arranged on a discrete physical setting, including ones associated with the Native American, Euroamerican Settlement, and the Manhattan/Cold War cultural landscapes. Intermixed on the same landscape, the challenge here is to protect and manage the resources in accordance with applicable federal laws and regulations, as well as adhere to the wishes of concerned but diverse interested parties in the treatment of these places.

There are two culturally related circumstances that further highlight the heritage significance of this place that are not readily apparent in the aerial view displayed in Figure 12. First, practically the entire cultural sequence for the Hanford Site is represented here, with two recorded archaeological sites in the near vicinity dating to perhaps 9000 years ago. Secondly, and of elevated significance for the Wanapum and other regional tribes, is that the opposite bank of the river at Coyote Rapids (Moon, or Water Swirl Place) is where the mid-19th century Wanapum religious prophet and dreamer, Smohalla (c. 1820–1895), held the first Washat dance ceremony that has become central to the originally revitalization driven Washani or Seven Drums religion. At that spot, a recent (one or two centuries) group of pit houses, with associated long house and sweat lodge, has been identified which probably is the place of the first dance.

Owing to Smohalla’s personal abilities, the religion spread to many neighboring tribes and is today still practiced in some form by members of the Colville, New Perce, Umatilla, Wanapum, Warm Springs, and Yakama Tribes. Of added importance, Smohalla gained his vision that ultimately led to the development of the Washani religion on a high ridge of nearby Rattlesnake Mountain (Laliik), which also lies on the Hanford Site and is a place of high reverence for the region’s tribes. Similar to the situation at nearby Gable Mountain, Rattlesnake Ridge was also a place for conducting vision quests, both for the Wanapum and the Yakama Tribe to the west.

7. Discussion

The multilayered cultural landscapes recognized for the Hanford Site present some interesting relationships and yet some contrasting characteristics with both the UNESCO and National Park Service categories. Each of the Hanford cultural landscapes contain properties and places that easily fit into the USNPS “historic site”, including many sites that have been found either potentially eligible for or listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The Hanford Native American cultural landscape has similarities with the international “organically evolved” and “associative” categories and to the USNPS ethnographic category, although none of the criteria for these categories neatly conform the Hanford cultural setting where a cultural continuum of about 10,000 years is apparent, with no distinguishable break in cultural continuity; as the Indian people repeatedly express, they have been an integral part of the land since “time immemorial”. Memories and imaginations of the Hanford landscape are linked to place names, myths, rituals, and traditions. Even though having been prevented since 1943 from occupying and using the resources as in earlier times, the powerful cultural and sacred attachment to the land remains undiminished by descendant tribal members, both individually and collectively.

There are similar feelings from the non-Indian descendant community of the Euroamerican Settlement cultural landscape, which is equal to the UNESCO “organically evolved” landscape and the USNPS “historic vernacular landscape”. The physical end of this historic era also culminated with the 1943 governmental taking of the land and wholesale demolition of town and rural standing architecture. Nonetheless, there remains today a strong collective memory among this descendant group of the past townspeople, farmers, orchardists, and ranchers, together with a genuine attachment to the former historic landscape of their ancestors.

A categorization of the Manhattan Project and Cold War Eras cultural landscape is difficult to directly align with any of the UNESCO or USNPS landscape categories. This landscape shares some parallels with the UNESCO “designed cultural landscape” and the corresponding USNPS “historic designed landscape”, even though these categories are typically reserved solely for garden and parkland landscapes constructed for aesthetic reasons that were consciously designed or laid out by a landscape architect, expert gardener, architect, engineer, or horticulturist according to specified design principles. The plutonium production facilities, along with numerous appurtenant features and largescale buffer zones with native vegetation, were clearly laid out and constructed by expert engineers and architects according to an intricate and highly specific design pattern, though markedly not with aesthetic principles in mind. This historic landscape at the Hanford Site, viewed in it is entirety, probably best associates with the USNPS “historic site” category, being a cultural landscape that is significant for its association with a historic event and/or activity.

The historic significance of the Manhattan Project and Cold War Eras cultural landscape at the national level is reflected by looking at just one of the reactor complexes constructed for production of plutonium—the B Reactor, the first large-scale nuclear reactor ever built. This complex was shut down in September 1968, after which several historic preservation designations were made, including being declared a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark (1976), a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark (1994), and a National Historic Landmark (2008), Since 2015, the site is an integral component of the nationwide Manhattan Project National Historical Park, administered jointly by the U.S. National Park Service and U.S. Department of Energy.

Cultural landscapes in certain settings where both a vast time depth and complex intermingling of historic sites, places, and heritage values on a single natural landscape can be difficult to conceptualize for land and resource management considerations. By separating and defining the sequential cultural patterns into layers of cultural landscapes, it becomes possible to not only differentiate between the chronological cultural expressions and the associated vestiges but to develop creative management approaches for both recognizing and providing proper treatment and protection for physical sites as well as more intangible heritage values that might be identified through interparty consultations. This approach is especially critical for a landscape as extensive as the Hanford Site, one where the inherent complexities of recent, ongoing, and future land use is at the forefront of management issues. The concept of cultural landscape preservation further integrates easily with other site-wide planning efforts, including future land use planning. Finally, cultural landscapes such as those at Hanford are inherently dynamic; changing conditions, resulting from both cultural and natural forces, necessitate adaptive management.

To properly identify, protect, and manage the individual prehistoric and historic resources at the Hanford Site, including the identified cultural landscapes, the U.S. Department of Energy formulated a suite of both short-term and long-term goals designed to effect proper stewardship of the heritage resources on the lands it currently administers [17]. Short-term objectives include: (1) Maintaining compliance with extant federal and state laws, U.S. Executive Orders, and other agency policies; (2) maintain ongoing consultation process with tribes, other descendant groups, and interested parties; (3) continue to identify archaeological and other Native American traditional places within the ethnographic, early settler, and Manhattan Project/Cold War cultural landscapes; (4) identify, design and implement proactive and effective protective actions for endangered cultural resources; and (5) maintain the integrity of material culture collections and associated records. Longer term goals that consider the changing cleanup mission include being successful stewards of the Hanford cultural and historic resources and then to undertake transfer of stewardship responsibilities to other entities as the Hanford mission eventually reduces the extent of the land under governmental control.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Research supporting this effort was originally funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Richland Operations Office, Richland, WA, while the author was a Senior Research Scientist and manager of the Hanford Cultural Resources Laboratory, Battelle Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA, 1994–2003. The author further acknowledges the contributions of Mona K. Wright, along with other cultural resources staff at the time, toward identifying and characterizing the Hanford cultural landscapes framework.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Mitchell, N.; Rössler, M.; Tricaud, P.-M. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A Handbook for Conservation and Management; World Heritage Papers 26; UNESCO, World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, C.A. Protecting Cultural Landscapes: Planning, Treatment and Management of Historic Landscapes. In Preservation Briefs; No. 36; U.S. Department of the Interior: Washington, DC, USA; National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Final Hanford Comprehensive Land Use Plan Environmental Impact Statement, Hanford Site, Richland, Washington; DOE/EIS-0222; U.S. Department of Energy: Richland, WA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of the Interior. Hanford Reach of the Columbia River: Final Comprehensive River Conservation Study and Environmental Impact Statement; National Park Service, Pacific Northwest Regional Office: Seattle, WA, USA, 1994; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters, J.C. (Ed.) Hanford Cultural Resources Management Plan; PNL-6942, UC 600; Battelle Memorial Institute: Columbus, OH, USA; Pacific Northwest Laboratory: Richland, WA, USA, 1989. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/5742524 (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- U.S. Department of Energy. National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form—Historic, Archaeological and Traditional Cultural Properties of the Hanford Site, Washington; DOE/RL-97-02; U.S. Department of Energy: Richland, WA, USA, 1997. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/348853 (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Ronda, J.P. Lewis & Clark Among the Indians; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, W.W.; Olsen, R.L. Further Documentation of Stone Piling During the Plateau Vision Quest. Am. Anthropol. 1954, 56, 441–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.B. Tales of Richland, White Bluffs, and Hanford, 1805–1943, Before the Atomic Reserve; Ye Galleon Press: Fairfield, WA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, R.; Franklin, R. (Eds.) Nowhere to Remember: Hanford, White Bluffs, and Richland to 1943; Washington State University Press: Pullman, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- White Bluffs-Hanford Pioneers Association. Family Histories from Hanford and White Bluffs, Washington; White Bluffs and Hanford History Association and Hanford Science Center: Richland, WA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Swindell, E.G., Jr. Report on Source, Nature, and Extent of the Fishing, Hunting and Miscellaneous Related Rights of Certain Tribes in Washington and Oregon Together with Affidavits Showing Locations of a Number of Usual and Accustomed Fishing Grounds and Stations; U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, Division of Forestry and Grazing: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy. History of the Plutonium Production Facilities at the Hanford Site Historic District, 1943–1990; DOE/RL-97-1047; U.S. Department of Energy: Richland, WA, USA, 2002. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/807939 (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Johnson, A.L. Wanapum Dispossession and Perseverance in the Mid-Columbia in the Atomic Age. Master’s Thesis, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nickens, P.R. Native American Involvement at the Hanford Site: 1943 to the Present. In Tribal Cultural Resource Studies at the Hanford Site, South-Central Washington, Proceedings of the Hanford Technical Exchange Program; Nickens, P.R., Ed.; PNNL-12032; Pacific Northwest National Laboratory: Richland, WA, USA, 1998; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nickens, P.R.; Wright, M.K. Management and Protection of Archaeological and Other Cultural Sites on the Hanford Landscape. Archaeol. Wash. 1999, 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Hanford Cultural Resources Management Plan; revised and expanded; DOE RL-98-10; U.S. Department of Energy: Richland, WA, USA, 2003. Available online: https://www.hanford.gov/files.cfm/han_cult_res_mngmt_plan_full_doc.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).