Abstract

Since the 1990s, the EU has promoted urban integrated programmes in vulnerable urban areas, combining top-down and bottom-up approaches to select the target areas. The bottom-up approach refers to selecting disadvantaged areas by municipalities, and the top-down approach deals with the eligibility criteria established by programmes. However, the level of compliance with these criteria among the areas selected is not usually evaluated. This study proposes a research strategy and analyses the URBAN and URBANA Initiatives in Spain (1994–2013). The objective is to evaluate the adequacy of selected areas through a methodology (effect size analysis) that assesses the level of vulnerability of urban areas defined in each city according to the criteria specified by the calls for proposals of the different urban regeneration programmes. According to the existing literature on the subject, a good selection of territorial targets is a fundamental element in the success of area-based interventions. The principal findings are that selected areas meet eligibility criteria, especially as regards urban fabric and unemployment. This article’s main contribution is to show that effect size analysis is an easy method to evaluate target selection in area-based policies from a methodological perspective. Together with centred measures of eligibility criteria (indicators), this methodological approach allows for comparisons between and within programmes and can be helpful to both practitioners or policy analysis scholars.

1. Introduction

Area-based intervention is a strategy commonly used to address socio-spatial inequalities in cities. These interventions could have different objectives but focus on improving urban areas with high socio-spatial vulnerability levels [1,2]. Area-based programmes help address distressed urban spaces that need special attention to promote their development and reduce socio-spatial inequalities. However, some analyses raise concerns about the success of these programmes [3,4]. Among other factors (the strategy, actors’ involvement, etc.), their success depends on the appropriate selection of territorial targets, which should be disadvantaged urban areas according to the criteria established by policies promoting such initiatives [5,6,7]. Specifically, good targeting offers the potential to maximise cost savings, with multiplier, interaction, focus, and neighbourhood threshold effects, which can significantly enhance the impact of public investment [8]. Target selection varies between programmes according to two classic approaches or their combination: top-down approach (authorities in charge of programmes select the targets), bottom-approach (local selection of target), or a combination of them (local selection within the framework of standard programme guidelines). However, few studies have assessed target selection criteria in such place-oriented policies [9] and the approach applied.

Since the 1990s, the European Union (EU) has promoted these programmes, and studies have evaluated their implementation and results. However, there is little comparative evidence on the adequacy of urban areas chosen as territorial targets and the approach used to select them. This paper analyses this issue in two programmes promoted by the EU in Spain: the URBAN Initiative between 1994 and 2006, and the URBANA Initiative from 2007 to 2013, which adopted a similar strategy to promote integrated urban development in disadvantaged urban areas. Therefore, this article aims to evaluate the selection of target areas for these initiatives in Spain by proposing a specific methodology.

The first section presents the main features of this type of programme in the EU, the importance of the approach they applied to design local projects, and their potential implications for selecting territorial targets. The second section describes the scope and eligibility criteria for selecting territorial targets established in the URBAN and URBANA Initiatives’ framework. The third section presents the methodology proposed to measure these criteria and assess the targets’ compliance level. The main results and their discussion are shown in the fourth section. The conclusions section summarises the main results and their implications regarding the design of integrated urban development initiatives.

2. Integrated Urban Development in the EU: The Meso-Level Strategy for Local Project Design and Target Selection in a Multi-Level Policy

The development of policies for disadvantaged urban areas has been commonly used in most western countries since the 1960s, including policies focused on specific objectives and policy sectors and integrated programmes that seek to address the multidimensionality of urban problems by establishing a more comprehensive agenda [10,11]. Nevertheless, there is a debate in the specific literature about the potential effects and benefits of area-based initiatives on tackling urban deprivation [8,12,13,14,15]. The purpose of these policies is to act on the spatial localisation of hardship and the effects these concentrations have on the inhabitants, the so-called neighbourhood effect [6,16]. Some researchers have argued that neighbourhood effects are relatively small in Europe [17] and do not justify a purely area-based approach. Instead, it would be necessary to integrate these interventions with people-based policies [18,19]. In this regard, Atkinson argues that area-based initiatives need to be supported by more comprehensive policies on the economy, employment, and social protection [20].

These interventions are launched to respond to the existence and extension of vulnerable neighbourhoods across cities. Specifically, these policies sustain that these areas eventually require special attention by public authorities because they accumulate more urban problems than other neighbourhoods in the same city. They will not generate factors facilitating their development without targeted public initiatives [2,21,22,23]. This policy strategy implies that, at least partially, the success of these initiatives depends on an appropriate selection of territorial targets as disadvantaged neighbourhoods [5,6,8].

The EU has addressed initiatives aimed at dealing with such urban areas since the 1990s. Together with other sectoral programmes, these initiatives generate an urban dimension to European policies based on integrated strategies to promote urban development, as shown by the current ‘Urban Agenda for the EU’ [24,25,26]). Specifically, from 1994 to 2006, the URBAN Initiative gave rise to the so-called European’ URBAN Acquis’ and laid the foundations for integrated urban development policies in the EU [27]. In addition to its comprehensive agenda, including actions in different policy sectors (physical space, economic development, environment, governance, or social inclusion), and the active involvement of local socioeconomic agents, the main trait of these initiatives is the bottom-up approach applied in the design and implementation of local projects within the framework of top-down guidelines established by programmes as an example of multi-level urban policies. Local authorities should specify in their projects the goals and implementation preferences provided by the general policy frame set by the EU and adaptations made by each State Member to a specific urban area selected as a territorial target by local authorities [28,29]. This is a common trait of the place-based orientation of EU cohesion policy in order to accomplish local objectives in the framework of European policies [30,31,32]. Therefore, this ‘meso-level approach’ seeks to combine top-down and bottom-up approaches to design and implement local projects [33]. Local authorities design a project, including selecting a specific vulnerable urban area, particular objectives according to the problems existing in this area, and the policy actions to accomplish them.

As in other territorial development initiatives, this bottom-up approach is justified by the closeness of local authorities to their urban reality. Proximity enables them to choose an appropriate urban area and designing a development strategy specifically adapted to the selected area with the participation of local socioeconomic agents. From a top-down perspective, national authorities in charge of programmes should guarantee the quality of proposals made by municipalities and their compliance with programme guidelines, including the targets’ level of compliance with eligibility criteria [34,35].

Despite the advantages of this bottom-up approach in local project design, this strategy may cause biases in selecting urban areas and other aspects included in programme policy frames, potentially leading to deficits in their implementation, as experienced with other initiatives of EU Cohesion Policy [36,37]. Differences between cities could promote the selection of territorial targets which may not meet the programme guidelines. Cities could have specific problems and needs and socio-spatial structures, promoting different targets within a programme. Target delimitation implies both technical and political processes due to different criteria about neighbourhood definition by stakeholders participating in projects design [38]. Local authorities could also understand programme objectives and guidelines differently, including eligibility criteria to select appropriate urban areas, a common situation in programmes with ambiguous or broad objectives [39,40,41]. According to the ex-post evaluation of the URBAN Initiative, the understanding of programme guidelines was one of the potential elements hindering its implementation and success [34].

Furthermore, other criteria could be incorporated through negotiation or lobbying by local authorities, as well as the approval of local projects in areas not sufficiently disadvantaged to win political support by supra-municipal authorities in subsequent applications of the same programme [42,43,44,45]. Specifically, subsequent applications of the same programme could give rise to the selection of less disadvantaged urban areas than in previous applications because the most disadvantaged ones have already been selected, affecting the programme’s success [7]. This difference between selected territorial targets in consecutive programmes applications has been seen in EU programmes and the Urban Empowerment Zones Program in the United States [46].

However, consecutive applications of a programme could promote learning processes among local authorities about project design. Interactions between municipalities and authorities in charge of programmes might lead to clarifications that facilitate the adaptation of local projects to programme guidelines [47,48]. The ex-post evaluation of the URBAN Initiative indicates that communication between different agencies involved in project management has not significantly affected their design and implementation [34]. However, the EU has launched initiatives to promote learning processes among local authorities. For instance, the URBACT programme, launched in 2003, has produced tools and promoted cooperative projects among cities about designing and implementing integrated urban development strategies. Some studies show that cities’ involvement in EU programmes has promoted the ‘Europeanization’ of their policies as they are progressively adapted to the framework and practices provided by these programmes [49,50,51,52]. Moreover, policy learning has been one of the primary outcomes or added-values of EU Cohesion Policy programmes [53].

However, despite the importance of targeting in project design, their level of compliance with the eligibility criteria established by the URBAN Initiative has been not analysed. Assessments of this programme focus on administrative aspects and their implementation, and to some extent, on the capacity to improve socio-spatial inequalities in the targeted areas. The URBAN Initiative evaluation reports indicate that urban areas were chosen according to statistical analysis or qualitative evidence. However, selected areas are presented as neighbourhood types (historical, peripheral, underdeveloped industrial centres) or by reporting some indicators about them compared with the EU average, but not within their municipalities [34,35,54]. Therefore, do the selected urban areas meet the eligibility criteria established by the URBAN Initiative beyond these general descriptions? Have the appropriate territorial targets been selected according to programme guidelines?

In the forthcoming sections, we will propose a research strategy to analyse this issue and answer this question about this specific EU Initiative and the URBANA Initiative developed within the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) in Spain during the period 2007–2013. Both programmes apply the meso-level method to design local projects. Therefore, the selection of disadvantaged urban areas as targets is made from below, through a bottom-up process that should adapt target selection to the guidelines provides by EU policy frames and its adaptation to Spain. According to the above literature review, within a programme, this meso-level method could promote an appropriate selection due to the closeness of local authorities to their urban realities; could promote an inappropriate target selection due to misunderstandings of guidelines designed by supra-municipal authorities or could promote an improper target selection due to opportunistic behaviours among actors involved in projects design and their selection. Subsequent programme applications could enable a better target selection (due to learning processes in policy design among local authorities), could erode targeting processes because the most disadvantaged urban areas have already been selected in previous applications, or could promote opportunist behaviours by supra-municipal authorities (to gain political support among those local authorities that were not chosen in previous applications) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluating target selection in multi-level urban policies: the ‘goodness’ and ‘limits’ of the meso-level strategy.

3. Territorial Targets for Integrated Urban Development in Spain: URBAN (1994–2006) and URBANA Initiatives (2007–2013)

The EU URBAN Initiative was adopted by 39 cities in Spain: 29 between 1994 and 1999 and 10 between 2000 and 2006. Subsequently, co-funded by the ERDF, the Spanish government promoted the URBANA Initiative (2007–2013) in 43 cities applying the same approach as the URBAN programme [55]. Besides, since 2007, the Urban Initiative Network (Red de Iniciativas Urbanas), promoted by the Spanish government, has offered a forum to share experiences and encourage learning processes about integrated urban development strategies among different actors involved in this policy (local government officials, municipal staff, and researchers).

Despite some differences in specific policy actions adopted by both programmes, the URBANA Initiative has followed the same bottom-up approach adopted by the URBAN Initiative regarding the design and implementation of local projects [56]. Within the scope of competitive calls, local governments propose a project to be developed in a specific urban area. This proposal is evaluated by the national authority in charge of the programme. Each local authority selects the territorial target as a disadvantaged urban area in the municipality. However, as in other aspects, such as objectives, policy actions to implement, and management mechanisms, the meso-level approach means that the choice of territorial targets should meet each programme’s specific guidelines [57,58]. In particular, within the EU, as regards the URBAN program, only in three countries were local projects selected by national authorities without competition among municipalities, a process close to a top-down approach (URBAN I: Sweden; URBAN II: Greece, Austria, and Sweden). Three countries used a competitive ‘open call’ (Spain, Portugal, and Finland). The other countries used a ‘restricted call’ among pre-selected municipalities. In Spain, the URBANA programme applied the same meso-level method (bottom-up design in the framework of top-down guidelines) through an open call among municipalities.

As part of their guidelines, URBAN and URBANA programmes described their territorial target through a general definition, but they also established specific eligibility criteria, urban problems, or vulnerability risks those urban areas should display to be selected. The first period of the URBAN Initiative (1993–2000) defined territorial targets as disadvantaged areas that presented “socioeconomic indicators significantly worse than the city’s average or urban agglomeration. These would include unemployment levels, education attainment, crime rate, standard of housing, the percentage of social-welfare benefit recipients, the socio-ethnic mix, environmental decay, deteriorating public transport and poor local facilities, etc.”. Specifically, target areas should be “urban neighbourhoods geographically identifiable; either an existing administrative unit such as a borough, a commune, or even smaller entities within a densely populated area, with a minimum size of the population, with a high level of unemployment, with a decayed urban fabric, bad housing conditions and lack of social amenities” [57]. The second URBAN period (2000–2006) indicated that it would continue developing an inclusive approach ‘to address the high and increasing number of social, environmental, and economic problems in urban agglomerations’ targeting “distressed urban neighbourhoods” [59]. The URBANA Initiative indicated that eligible areas had to be urban spaces in recession, disadvantaged urban areas that need to be redeveloped because of economic and social difficulties [58,60].

These top-down guidelines and the bottom-up approach to local project design means that authorities choose suitable areas according to eligibility criteria and their city’s socio-spatial context (or urban agglomeration). Therefore, selected urban areas should show a higher socio-spatial vulnerability than the average in their cities. Specifically, programmes establish eligibility criteria as urban problems that should exist in selected urban areas. These should be specified in the diagnosis of the selected urban area included in the project design. According to the central dimensions of the European integrated urban development framework, urban problems included in each programme as eligibility criteria are shown in Table 1. Although URBAN II and URBANA include more specific criteria regarding social exclusion processes, there is a standard set of criteria regarding unemployment, economic activity, and urban environment. Problems regarding physical space (the urban fabric) and environmental sustainability are included together with environmental conditions. However, there is a trend to emphasise environmental issues in URBAN II and URBANA, showing the change to the current framework on sustainable urban development in the European Union. Governance is not included because this dimension is not among the eligibility criteria to select urban areas as a target (Table 2).

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria in URBAN and URBANA initiatives.

Finally, programmes also include other criteria about the demographic dimension of cities and selected urban areas. The first URBAN period considered municipalities with at least 100,000 inhabitants. The population size of the eligible areas was not specified, although they should be densely populated. The second call did not indicate municipalities’ size; however, selected areas should have at least 20,000 inhabitants (in some exceptions, more than 10,000 inhabitants). The URBANA Initiative included municipalities with at least 50,000 inhabitants (or provincial capitals) but did not provide criteria about the population or geographical size of eligible areas. Participant municipalities in the URBAN programme could also participate in the URBANA programme. Therefore, the cases analysed do not allow checking one of the general hypotheses proposed previously (H22, Table 1).

4. Data and Methods

Two main approaches have been applied to evaluate the appropriateness of territorial targets selected in other area-based programmes. Firstly, an ex-ante selection of urban areas among those with the highest level of vulnerability is based on a national composite index of socio-spatial vulnerability [61,62]. This method was also used in some countries participating in the URBAN Initiative, using the programme’s eligibility criteria to select or pre-select cities before launching a competitive call among them [34,37]. Secondly, ex-post comparisons between the chosen and non-chosen urban areas of the country or region where the programme is applied to show if selected urban areas better fulfil the established eligibility criteria than non-selected areas [9,46,63].

Due to Spain’s open call method, the URBAN and URBANA Initiatives were not applied simultaneously in all Spanish cities. The selected targets are vulnerable urban areas in cities participating in the initiatives but not necessarily the most vulnerable urban areas in Spain. Accordingly, the targets’ compliance with the criteria established by the programmes will be evaluated by comparing the chosen urban areas with non-chosen areas of participating cities. Therefore, the analyses will show whether the targets of selected projects meet the eligibility criteria established by the programmes.

This section presents the research design and methods used to address this question. The analysis focused on cities with at least 100,000 inhabitants and provincial capitals, representing a total of 84 projects in all 67 cities participating in the URBAN and URBANA Initiatives between 1994 and 2013, given that some cities participated in both programmes.

4.1. Geographical Delimitation of Urban Areas in Participating Cities

In each participating city, the selected urban area has been delimitated as a group of census tracts according to the description included in the documentation of local projects compiled by the national authority in charge of programmes. According to two main criteria, the other census tracts in each city have been clustered using GIS software in urban areas. Firstly, non-chosen areas have a similar population size to that of the selected urban areas (their average equals 17,104 residents, SD = 6268). Secondly, census tracts included in delimitated urban areas should show a similar level of socio-spatial vulnerability according to a socio-spatial vulnerability indicator for all the census tracts of Spanish cities with at least 100,000 inhabitants in 1991 and 2001. This composite indicator includes four indexes: the unemployment rate, the percentage of unskilled workers, the percentage of residents without elementary education certificates, and the percentage of houses in poor conditions. The composite indicator is computed as the average of these indexes, ranging from 0 to 100. This index has been validated by applying confirmatory factor analysis [64]. ANOVA analyses have been performed in each city to validate the internal homogeneity of urban areas delimitated. In most cities, this test shows better results than other existing aggregations of census tracts, such as the district level included in the Spanish Census or areas delimitated in the framework of the URBAN AUDIT project by the Spanish Statistical Institute (INE) and EUROSTAT. 722 areas were delimited in cities participating in the URBAN Initiative (35 of these were targeted in URBAN I and II), and 623 urban areas in cities participating in the URBANA Initiative (43 of them targeted by Urbana). Geographical delimitation of urban areas and basic socioeconomic information can be found in [65].

4.2. Eligibility Criteria: Indicators

Indicators to measure eligibility criteria have been computed using data from the Spanish Census in 1991 and 2001, along with data about business establishment provided by a specialised company for the same years. The Spanish Census does not include data for all problems (eligibility criteria), and specifically, does not provide information on environmental problems (waste, energy, pollution, etc.). Seven indicators to measure problems included as eligibility criteria within the dimensions of physical space, economic development, and social inclusion were defined (Table 3).

Table 3.

Indicators of eligibility criteria.

Physical space problems were measured by analysing housing conditions (percentage of houses in poor conditions). This indicator is commonly used to measure urban vulnerability [66]. In addition to the unemployment rate, four indicators have been designed to measure eligibility criteria for social exclusion. Population ageing (percentage aged ≥ 65 years), illiteracy rate (percentage of the population aged ≥ 16 without formal education), and the percentage of immigrants from countries other than the EU and North America as a proxy of immigrant and minority groups with social integration needs.

Due to the absence of income data at the Census tract level to measure poverty, a socioeconomic status indicator has been computed as a proxy of the income level of residents. This indicator, previously used to analyse socio-spatial inequalities in cities, analyses the weight of five occupational groups on the total working population in each urban area, from unskilled workers to managers [67,68]. In detail, this indicator considers the weighting of five occupational groups as the percentage of the total working population in the urban area. This indicator is analysed as an interval variable, computing its weighted average. Then, the indicator is transformed into a 0–100 scale to facilitate its interpretation. Therefore, the indicator varies from 0 (if all working population are unskilled workers) and 100 (if all working population are managers). Economic activity was measured according to the number of companies (establishment with economic activity) per thousand inhabitants (this indicator was inverted to assess the presence of a low level of economic activity).

In addition to these indicators, the socio-spatial vulnerability indicator will also be analysed to assess compliance with the broad definition of targets as vulnerable urban areas. As mentioned before, this indicator combines three of the common eligibility criteria (housing in poor conditions, unemployment rate, and illiteracy rate) and is a proxy for the socioeconomic status of residents (percentage of unskilled workers) [64]. Therefore, it provides information about levels of socio-spatial vulnerability based on core indicators measuring eligibility criteria.

Accordingly, as with project design, indicators have been measured before the start of each programme: 1991 Census data for the first period of the URBAN Initiative, and 2001 Census data for the second period of the URBAN Initiative and the URBANA Initiative. Due to the bottom-up perspective of local project design and programme guidelines, urban areas should be selected as vulnerable spaces in their cities. Therefore, indicators have been centred on the average of municipalities in which each urban area is located and the corresponding year to reproduce the rationale used by local authorities to select their territorial targets.

4.3. Eligibility Criteria Compliance: Differences between Selected and Non-Selected Urban Areas

Effect sizes for each indicator have been calculated to measure compliance with eligibility criteria. In addition to statistical significance, effect size provides standardised differences between selected and non-selected areas regardless of the scale used to measure each indicator, allowing for comparisons between indicators and between programmes [69,70]. Effect size values higher than 0.5 indicate moderate differences between selected and non-selected areas, large for values from 0.8. Specifically, these values mean that around 70% (value equal to 0.5) and 80% (value equal to 0.8) of chosen areas have higher values than the average of the non-chosen areas [71]. Therefore, these values will be interpreted as a moderate and high target compliance level with eligibility criteria. Graphs will be used to present effect sizes for each indicator and their confidence intervals. Due to the difference in the number of cases between groups, Hedges’ g index is used to measure effect sizes instead of the classic Cohen’s d [72,73]. Indeed, effect sizes are measured as g = (mean selected areas-mean unselected areas)/(pooled standard deviation). Hedges’ g values and their interval confidences have been included in Appendix A. Descriptive values for each indicator and classic t-test measures have also been included in Appendix A. T-tests provide differences between selected and non-selected areas in the metrics used for each indicator. Effect size provides the magnitude of these differences in a similar metric (as standardised differences).

5. Results and Discussion

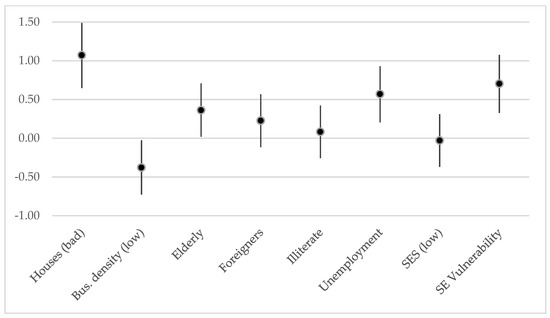

Standardised differences between the selected and unselected areas in the URBAN Initiative are shown in Figure 1. Except for the density of economic activity (g = −0.379) and the residents’ socioeconomic status (g = −0.029), effect sizes indicate that chosen areas have higher values in indicators measuring eligibility criteria than non-chosen areas. In the former, the percentage of the elderly (g = 0.362), foreigners with social inclusion needs (g = 0.227), and people without formal education (g = 0.083) are higher. However, compliance levels are only moderate or high for two indicators: unemployment rate (g = 0.571) and housing conditions (g = 1.073). The analyses also show that chosen areas are more disadvantaged urban spaces than non-chosen areas according to the socio-spatial vulnerability indicator (g = 0.705).

Figure 1.

URBAN Initiative: differences between chosen and non-chosen areas. Effect sizes: Hedges’ g (95% confidence interval).

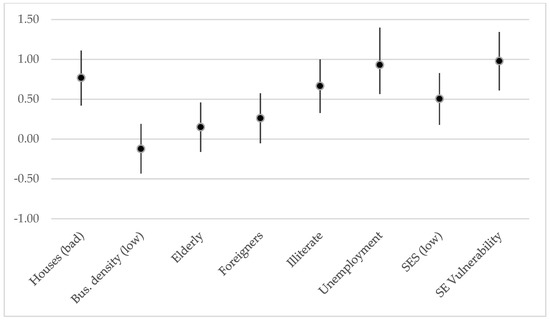

Selected and unselected areas in the URBANA Initiative frame are practically similar according to their economic activity level, older people, and foreigners with social needs (g values less than 0.3). Compliance levels are moderate for residents’ socio-economic status (g = 0.505), the percentage of people without a formal education (g = 0.666), housing conditions (g = 0.768), and higher unemployment (g = 0.930). Furthermore, the socio-spatial vulnerability index also shows high compliance with eligibility criteria (g = 0.979) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

URBANA Programme: Differences between chosen and non-chosen areas. Effect sizes: Hedges’ g (95% confidence interval).

Two of the three common eligibility criteria show moderate and high compliance levels in both programmes: housing conditions and unemployment rate (Table 3). Labour inclusion is a central objective of the EU Cohesion Policy and is strongly correlated with other social exclusion processes and poverty, being a crucial problem in Spain and a central goal of these initiatives [28]. The unemployment rate was crucial to differentiate between provinces (NUTS3) that received funding and those that did not, under the ERDF Objective 2 programmes between 1994 and 1999 [46]. URBAN ex-post evaluations also indicate that the unemployment rate is higher in selected areas than the EU average [34,35]. Therefore, the analyses confirm this trait when comparing these areas with their city context, as the programme guidelines establish, as well as target selection appropriateness according to housing conditions and their socio-spatial disadvantage in their cities (socio-spatial vulnerability index).

Nevertheless, in both programmes, especially in URBAN projects, non-chosen areas have a higher level of economic activity than chosen areas, another common eligibility criterion linked to the EU Cohesion Policy’s primary objectives (Table 3). Many of the selected urban areas are in historic districts (in some cases, encompassing the entire historic district). They may have a high concentration of businesses and economic activity due to their central location in cities. However, suburbanisation processes during previous programme periods in Spain have led to an increase in social vulnerability in these areas, the mobility of the middle-class to the new suburban spaces, ageing processes, and the decay of the urban environment [74,75]. Therefore, the physical rehabilitation of historic districts in Spanish cities was a crucial issue in that period [76]. In this sense, 18 of the selected urban areas (31%) were classified as “historic city centres” in the URBAN Initiative in Spain. In the URBANA Initiative, 14 projects (33%) were developed in historic parts of the city.

However, this could also indicate that some local authorities select these urban areas considering their location advantage among all deprived neighbourhoods in cities. Central location, some business density, and heritage resources that will be improved could facilitate their recovery as an ‘attractive place’, promoting revitalisation and impacting the city’s economic development more than peripheral deprived neighbourhoods. Place attractiveness is a growing concern in urban policies across Europe in the general transition from cities as productive spaces to places for consumption [28,77]. Intervention strategies of analysed programmes stress contextual interventions on the neighbourhood over actions focused on specific groups of residents. This strategy is implemented more in central neighbourhoods than in peripheral ones [78,79]. Therefore, the meso-level method shape opportunities for local authorities to adopt adaptive strategies as regards target selection. To accommodate different types of vulnerable urban areas to the general guidelines provided from above according to their strategy for urban development and their knowledge of their municipalities, as the meso-level method propose (H11, in Table 1). Selected targets meet these guidelines, but it also means the same programme is applied in different territorial contexts that could promote heterogeneous effects within the programme according to their differences, as other analyses show [80,81].

Differences between the programmes show that compliance levels are higher in the URBANA than in the URBAN Initiative for both common and non-common eligibility criteria, except for older people and housing conditions (Table 4). In this latter case, lower compliance could indicate an increasing emphasis on sustainability [54]. Therefore, analyses do not suggest that the sequential application of URBAN and URBANA initiatives leads to a lower degree of compliance among territorial targets, as indicated by other programmes [40,41,42]. Nevertheless, as mentioned before, municipalities participating in the URBAN programme could also participate in the URBANA programme. Therefore, the number of disadvantaged urban areas to be selected is not reduced from the first to the second programme (H22, Table 1). In this case, results may indicate learning processes among authorities involved in target selection (H21, Table 1). Other analyses concerning the implementation of URBAN and URBANA projects show they have promoted the European framework’s learning process on integrating urban development [82,83,84]. Spanish cities have actively participated in URBACT activities (28 Spanish cities are current members of networks promoted by this EU programme). Local authorities highlight the learning opportunities encouraged by their participation [85]. Moreover, continuity between the initiatives analysed from 1993 to 2013 using a similar strategy and guidelines to promote integrated urban development may also favour the learning process among local authorities involved in the design of local projects, including the compliance of targets with eligibility criteria shown in this research.

Table 4.

Eligibility criteria compliance: differences between chosen and non-chosen areas. Effect sizes for each programme and differences between them (Hedges’ g).

6. Conclusions

The main reason for area-based initiatives is to focus on territorial targets with a higher level of socio-spatial vulnerability. Therefore, their success depends, together with other factors, on the correct selection of their targets during project design. This place-based approach has been progressively included in the EU Cohesion Policy, developing a framework to promote integrated urban development initiatives based on the meso-level approach combining top-down and bottom-up approaches to design local projects. Does this approach enable an appropriate selection of territorial targets?

The analyses performed here about these kinds of initiatives developed in Spain from 1993 to 2013 show that chosen areas were disadvantaged urban spaces in the context of their respective cities as the programme required. These urban areas have a higher level of socio-spatial vulnerability than unselected areas, especially regarding housing conditions, as an indicator of deterioration of urban spaces, and unemployment rate, as an indicator of social exclusion, a central objective of the EU Cohesion Policy. However, compliance levels are lower regarding other specific eligibility criteria related to social exclusion, especially regarding the economic activity indicator, standard eligibility criteria in URBAN and URBANA initiatives, and the EU Cohesion Policy’s central objective.

These results suggest that the approach has introduced the possibility of applying adaptive strategies for local authorities to select targets that combine socio-spatial vulnerability (urban fabric decay and unemployment) with a higher density of economic activity due to their central location in cities (historic districts). The multi-level character of programmes analysed and the meso-level approach allow different targets to be accommodated in the programme guidelines that could respond to local actors’ strategies, defining deprived urban areas and selecting among them as other studies have shown [38]. Therefore, although this approach does not promote an inadequate selection of their territorial targets, it introduces opportunities to develop adaptive strategies regarding target selection. This strategy raises a degree of heterogeneity in programmes that could promote project implementation differences and, therefore, affect the programmes’ success [5].

The analyses also show that compliance levels were not reduced over time. This result suggests that the continuity of the integrated strategy between URBAN and URBANA Initiatives (including the criteria to select their targets) might have promoted learning processes among agents involved in the design of local projects and their selection. Therefore, together with other aspects affecting project success (the strategy and its implementation), the authorities involved in such initiatives in Spain might have improved an element of project design that could aid their success: the appropriate territorial target.

Nevertheless, the research has limitations that should be indicated. First, our analyses do not provide information to show that selected areas present the highest vulnerability levels in each city (or Spain as a whole) but suggest that these urban areas met the programmes’ criteria compared with other unselected areas in participating cities. The article’s objective was to assess the appropriateness of the targeting process. Neither programmes indicate that one of its goals is to target the most vulnerable urban areas in Spain, as programmes in other countries do [5,38,44]. Therefore, other vulnerable areas could exist in each city, as the results regarding economic density suggest, or in cities that have not participated in the programmes analysed.

Second, information about unselected projects does not exist, and a better assessment of target selection could be performed, including these projects in our analyses. This comparison could provide better information about the target selection made by all participants in the multi-level framework established by the open-call and the meso-level approach applied in Spain: urban area selection in each municipality and local project selection at the national level. The analysis only shows that the selected projects meet the programme requirements as regards target eligibility criteria. The non-selected projects could provide information to explore the possibility of poor project design better, guidelines misunderstanding (local project unselected by national authorities due to an unappropriated selection of target by local authorities), or the existence of opportunist behaviours (unselected project even if their target areas were more disadvantaged than local projects selected). Nevertheless, target selection is only an aspect of project design evaluated by authorities in charge of programmes.

Third, the study could also be improved by including other indicators. Data limitations at the infra-municipal level in Spain prevented the evaluation of some urban issues included in the current policy frames of integrated and sustainable urban development promoted by the EU (and worldwide) within the framework of the New Urban Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals, such as environmental sustainability [26]. These limitations cannot be overcome with the available information to evaluate previous initiatives such as the URBAN and URBANA programmes.

This paper has proposed using effect size as an easy method to evaluate target selection in such policies from a methodological perspective. Together with centred measures of eligibility criteria (indicators), this methodological approach allows for comparisons between and within programmes. From a practitioner point of view, this approach could show the appropriateness of the selected area in local project design. National authorities in charge of programmes could evaluate the appropriateness of the urban areas proposed as targets by local authorities. Moreover, this approach could provide more transparent information about local project selection as regards local authorities.

More comparative research between different programmes could help analyse and establish benchmarks for eligibility criteria and a better definition for selecting them in future research. For instance, results show that the unemployment rate and housing conditions and the composite indexes of socio-spatial vulnerability distinguish between selected and non-selected areas very well. Therefore, these indicators could help evaluate target selection for other programmes and evaluate improvement in this task between different and consecutive programmes regarding this crucial aspect in place-based policies.

This article analyses the appropriateness of the targeting process in two programmes as an exemplar of the meso-level method (a top-down process in the framework of supra-municipal guidelines). Further studies should be carried out to compare the appropriateness of this approach with programmes representing other approaches. As mentioned before, other European countries applied a more top-down approach in target selection, even in the frame of the URBAN programme. Other studies could analyse the influence of target selection as a central task in project design on local project implementation and their success, and therefore, area-based programmes as a whole. An unappropriated selection could erode programme success due to the inclusion of non-disadvantaged urban areas [5,6,8]. However, the aforementioned adaptive strategy could promote heterogeneous effects due to improving the same programme in different territorial contexts that meet programme guidelines but start from different opportunities to achieve their proposed goals.

Since 2007, state members could define their own urban strategy within the framework of EU Cohesion Policy, as well as the type and scale of territorial targets, from neighbourhoods to functional urban areas (the EU proxy to metropolitan areas). Therefore, different methods have been applied to design and select local projects and their targets, allowing comparative analyses between them in the same policy frame and their general guidelines (EU Cohesion Policy) in order to analyse their appropriateness of target selection and their influence on the success of urban initiatives promoted in each country. This also means that the opportunity to study the role of inter-municipal relationships and cooperation in project design and territorial target selection in those initiatives focused on functional urban areas and their influence on projects and programme success [86,87].

Author Contributions

M.F.-G. contributed to the conceptualisation, methodology, curation, validation and analysis of the data, writing, revision and editing of the manuscript; C.J.N. contributed to the conceptualisation, methodology, validation and analysis of the data, writing and review of the draft manuscript and revision of the manuscript; I.G.-R. contributed to the analysis, use of software and data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was developed within the framework of the URBAN-IMPACTS project financed by the MINECO-Spanish Government and the ERDF-European Union (Grant No. CSO-2015-70048-R) and the Jean Monnet Chair in European Urban Policies (EUrPol), supported by the European Commission (Ref. Project: 612051-EPP-1-2019-1-ESEPPJMO-CHAIR).

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística through a specific agreement. This agreement limit data sharing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude for access to the documentation of local projects provided by the Spanish national authority in charge of the evaluated program: Dirección General de Fondos Comunitarios, Ministerio de Hacienda, Spanish Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The European Commission’s support of this publication through the Jean Monnet Chain in European Urban Policies (Ref. Project: 612051- EPP-1-2019-1-ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR) does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors. The Commission cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Appendix A

Comparing chosen and non-chosen urban areas: t-test and effect sizes:

Table A1.

URBAN.

Table A1.

URBAN.

| Chosen Area | Non-Chosen Area | Effect Size: Hedges’ g | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Diff. | t | Estimate | [95% Conf. Interval] | |||

| Housing (poor) | 9.280 | 13.477 | −0.469 | 8.800 | 9.749 | 6.202 | *** | 1.073 | 0.648 | 1.489 |

| Bus. density (low) | −5.849 | 20.352 | 0.296 | 15.949 | −6.145 | −2.192 | * | −0.379 | −0.727 | −0.027 |

| Elderly | 1.477 | 4.099 | −0.075 | 4.278 | 1.551 | 2.097 | * | 0.362 | 0.019 | 0.709 |

| Foreigners | 0.478 | 1.586 | −0.024 | 2.230 | 0.502 | 1.314 | 0.227 | −0.117 | 0.568 | |

| Illiterate | 0.504 | 6.078 | −0.025 | 6.415 | 0.529 | 0.478 | 0.083 | −0.258 | 0.422 | |

| Unemployment | 1.810 | 3.281 | −0.092 | 3.331 | 1.901 | 3.297 | ** | 0.571 | 0.205 | 0.929 |

| SES (low) | −0.294 | 10.514 | 0.015 | 10.327 | −0.309 | −0.172 | −0.029 | −0.369 | 0.309 | |

| SE Vulnerability | 2.975 | 4.375 | −0.150 | 4.437 | 3.126 | 4.069 | *** | 0.705 | 0.326 | 1.075 |

N: Chosen areas: 35; Non-chosen areas = 692 (df = 725). Value 0 is the average of cities. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Table A2.

URBANA.

Table A2.

URBANA.

| Chosen Area | Non-Chosen Area | Effect Size: Hedges’ g | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Diff. | t | Estimate | [95% Conf. Interval] | |||

| Housing (poor) | 6.264 | 9.458 | −0.4644 | 8.703 | 6.728 | 4.862 | *** | 0.768 | 0.419 | 1.111 |

| Bus. density (low) | −2.184 | 20.535 | 0.1617 | 19.014 | −2.343 | −0.775 | −0.123 | −0.433 | 0.189 | |

| Elderly | 0.605 | 3.560 | −0.0448 | 4.394 | 0.650 | 0.946 | 0.149 | −0.162 | 0.459 | |

| Foreigners | 0.606 | 1.616 | −0.0449 | 2.531 | 0.651 | 1.661 | 0.262 | −0.052 | 0.574 | |

| Illiterate | 3.644 | 5.965 | −0.2701 | 5.865 | 3.914 | 4.217 | *** | 0.666 | 0.326 | 0.999 |

| Unemployment | 2.692 | 3.825 | −0.1996 | 3.043 | 2.891 | 5.898 | *** | 0.930 | 0.564 | 1.398 |

| SES (low) | 4.477 | 8.239 | −0.3319 | 9.597 | 4.809 | 3.199 | ** | 0.505 | 0.178 | 0.827 |

| SE Vulnerability | 3.929 | 4.696 | −0.2913 | 4.273 | 4.221 | 6.207 | *** | 0.979 | 0.609 | 1.343 |

N: Chosen areas: 43; Non-chosen areas = 580 (df = 621). Value 0 is the average of cities. ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

References

- d’Albergo, E. Urban Issues in Nation-State Agendas: A Comparison in Western Europe. Urban Res. Pract. 2010, 3, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gent, W.P.C.; Musterd, S.; Ostendorf, W. Disentangling Neighbourhood Problems: Area-Based Interventions in Western European Cities. Urban Res. Pract. 2009, 2, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, T.J. Who Benefits from State and Local Economic Development Policies? WE Upjohn Institute for Employment Research: Kalamazoo, MI, USA; ISBN 0-88099-113-5.

- Lawless, P. Can Area-Based Regeneration Programmes Ever Work? Evidence from England’s New Deal for Communities Programme. Policy Stud. 2012, 33, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiels, C.; Baker, D.; Barrow, S. How Accurately Does Regeneration Target Local Need? Targeting Deprived Communities in the UK. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2013, 26, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, A. Learning from the Past? A Review of Approaches to Spatial Targeting in Urban Policy. Plan. Theory Pract. 2011, 12, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; Fisher, P. The Failures of Economic Development Incentives. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2004, 70, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D.E. Strategic, Geographic Targeting of Housing and Community Development Resources. Urban Aff. Rev. 2008, 43, 629–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, R.T. Siting It Right: Do States Target Economic Distress When Designating Enterprise Zones? Econ. Dev. Q. 2004, 18, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmon, N. Neighborhood Regeneration: The State of the Art. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1997, 17, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.; Sykes, H. Urban Regeneration: A Handbook; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2000; ISBN 0761967168. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, M.D.; Rickman, D.S.; Olfert, M.R.; Tan, Y. When Spatial Equilibrium Fails: Is Place-Based Policy Second Best? Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 1303–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Boyne, G.; Ashworth, R. Towards a Geography of People Poverty and Place Poverty. Policy Politics 2001, 29, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.H. People, Places, and Policy: A Politically Relevant Framework for Efforts to Reduce Concentrated Poverty. Policy Stud. J. 2004, 32, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turok, I. Property-Led Urban Regeneration: Panacea or Placebo? Environ. Plan. A 1992, 24, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J. Addressing Europe’s Urban Challenges: Lessons from the EU URBAN Community Initiative. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 2145–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, R.; Musterd, S. Area-Based Policies: A Critical Appraisal. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, R.M. Poverty, Policy, and Place: How Poverty and Policies to Alleviate Poverty Are Shaped by Local Characteristics. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2005, 28, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A.T. Putting People Back into Place-Based Public Policies. J. Urban Aff. 2015, 37, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R. Combating Social Exclusion in Europe: The New Urban Policy Challenge. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 1037–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, M.B.; van beckhoven, E. The Integrated Approach in Neighbourhood Renewal: More than Just a Philosophy? Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2010, 101, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.T.; van Kempen, R. New Trends in Urban Policies in Europe: Evidence from the Netherlands and Denmark. Cities 2003, 20, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.; Carmichael, L. Neighbourhood as a New Focus for Action in the Urban Policies of West European States. In Disadvantaged by Where You Live; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2007; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R.; Lane, C. EU Urban Policy, European Urban Policies and the Neighbourhood: An Overview of Concepts, Programmes and Strategies. In Proceedings of the International Conference Vital Cities, European Urban Research Association, Glasgow, UK, 12 September 2007; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R. The Urban Dimension in Cohesion Policy: Past Developments and Future Prospects. In Proceedings of the a RSA Workshop on The New Cycle of the Cohesion Policy, Brussels, Belgium, 24 March 2014; Volume 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament. The Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Region. In The Urban Dimension of EU Policies—Key Features of an EU Urban Agenda; European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Guidance for Member States on Integrated Sustainable Urban Development; EU Regional and Urban Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, C.J.; Rodríguez-García, M.J. Urban Policies as Multi-Level Policy Mixes. The Comparative Urban Portfolio Analysis to Study the Strategies of Integral Urban Development Initiatives. Cities 2020, 102, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Yáñez, C.J. The Effectiveness of Integral Urban Strategies: Policy Theory and Target Scale. The European URBAN I Initiative and Employment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Territorial Agenda 2020 Put in Practice—Enhancing the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Cohesion Policy by a Place-Based Approach; Synthesis Report; Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Volume 1, ISBN 9789279480515. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, C. The Post-2013 Reform of EU Cohesion Policy and the Place-Based Narrative. J. Eur. Public Policy 2013, 20, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Koontz, T.M. Multi-Level Governance, Policy Implementation and Participation: The EU’s Mandated Participatory Planning Approach to Implementing Environmental Policy. J. Eur. Public Policy 2014, 21, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Reconciling Top-down and Bottom-up Development Policies. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GHK. Ex-Post Evaluation Urban Community Initiative; GHK: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- ECOTEC. Ex-Post Evaluation of Cohesion Policy Programmes 2000–2006. The URBAN Community Initiative. Final Report Prepared for the European Commission; ECOTEC Research and Consulting: Birmingham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blom-Hansen, J. Principals, Agents, and the Implementation of EU Cohesion Policy. J. Eur. Public Policy 2005, 12, 624–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rynck, S.; McAleavey, P. The Cohesion Deficit in Structural Fund Policy. J. Eur. Public Policy 2001, 8, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegan, R.; Mitchell, A. “It’s not community round here, it’s neighbourhood”: Neighbourhood change and cohesion in urban regeneration policies. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2167–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.H. Goal Ambiguity in US Federal Agencies. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2005, 15, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matland, R.E. Synthesising the Implementation Literature: The Ambiguity-Conflict Model of Policy Implementation. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1995, 5, 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, J.L.; Wildavsky, A. Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland; Or, Why It’s Amazing That Federal Programs Work at All, This Being a Saga of the Economic Development Administration as Told by Two Sympathetic Observers Who Seek to Build Morals; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984; Volume 708, ISBN 0520053311. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, J.S. Updating urban policy. In Confronting Poverty: Prescriptions for Change; Sheldon, H., Danziger, G., Sandefur, D., Weinberg, D.H., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 226–252. [Google Scholar]

- Talanker, A.; Davis, K.; LeRoy, G. Straying from Good Intentions: How States Are Weakening Enterprise Zone and Tax Increment Financing Programs; Good Jobs First: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Turok, I.; Hopkins, N. Competition and Area Selection in Scotland’s New Urban Policy. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 2021–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahariadis, N. The Political Economy of State Subsidies in Europe. Policy Stud. J. 2002, 30, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, R.T.; Bondonio, D. Losing Focus: A Comparative Evaluation of Spatially Targeted Economic Revitalization Programmes in the US and the EU. Reg. Stud. 2004, 38, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, E.R. The Pressman-Wildavsky Paradox: Four Addenda or Why Models Based on Probability Theory Can Predict Implementation Success and Suggest Useful Tactical Advice for Implementers. J. Public Policy 1982, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.J. Mandate Design and Implementation: Enhancing Implementation Efforts and Shaping Regulatory Styles. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 1993, 12, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukes, T. The URBAN Programme and the European Urban Policy Discourse: Successful Instruments to Europeanize the Urban Level? GeoJournal 2008, 72, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hamedinger, A.; Wolffhardt, A. The Europeanization of Cities: Policies, Urban Change and Surban Network; Techne Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; ISBN 978-90-8594-027-2. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. Europeanization at the Urban Level: Local Actors, Institutions and the Dynamics of Multi-Level Interaction. J. Eur. Public Policy 2005, 12, 668–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, I. How the EU Regional Policy Can Shape Urban Change in Southern Europe: Learning from Different Planning Processes in Palermo. Urban Res. Pract. 2019, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairate, A. The ‘Added Value’ of European Union Cohesion Policy. Reg. Stud. 2006, 40, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Programming of the Structural Funds 2000–2006: An Initial Assessment of the Urban Initiative; European Communities Luxemburg: Luxemburg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- de Gregorio Hurtado, S. Is EU Urban Policy Transforming Urban Regeneration in Spain? Answers from an Analysis of the Iniciativa Urbana (2007–2013). Cities 2017, 60, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.J.; Rodríguez-García, M.J.; Gómez, I. La Agenda Del Desarrollo Urbano Integral En España (1994–2013). Anduli 2018, 17, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication to the Member States Laying down Guidelines for Operational Programmes Which Member States Are Invited to Establish in the Framework of a Community Initiative Concerning Urban Areas (Urban); European Communities: Luxemburg, 1994; pp. 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Administraciones Públicas. Resolución de 7 de Noviembre de 2007, de La Secretaría De Estado de Cooperación Territorial Por La Que Se Aprueban Las Bases Reguladoras de La Convocatoria 2007 de Ayudas Del Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional Para Cofinanciar Proyectos de Desarrollo; Secretaria de Estado de Cooperación Territorial: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the MSs of 28 April 2000, Laying down Guidelines for a Community Initiative Concerning Economic and Social Regeneration of Cities and of Neighbourhoods in Crisis in Order to Promote Sustainable Urban Development; European Communities: Luxemburg, 2000; pp. 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda. Iniciativa Urbana (Urban). Orientaciones Para La Elaboración de Propuestas; Direccion General de Fondos Comunitarios: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Greig, A.; El-Haram, M.; Horner, M. Using Deprivation Indices in Regeneration: Does the Response Match the Diagnosis? Cities 2010, 27, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, D.; Barnes, H.; Noble, M.; Davies, J.; Garratt, E.; Dibben, C. The English Indices of Deprivation 2010; Department for Communities and Local Government: London, UK, 2011.

- Beekmans, J.; Ploegmakers, H.; Martens, K.; van der Krabben, E. Countering Decline of Industrial Sites: Do Local Economic Development Policies Target the Neediest Places? Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 3027–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-García, M.; Navarro Yáñez, C.J.; Zapata Moya, Á.R.; Mora, C.M. The Analysis of Urban Inequality Proposal and Validation of a Synthetic Index in Spain (1991–2001) [El Análisis de La Desigualdad Urbana Propuesta y Validación de Un Índice de Nivel Socioeconómico En Áreas Urbanas Españolas (1991–2001)1]. Empiria 2018, 39, 49–77. [Google Scholar]

- Catalogue—Urban Impacts. Available online: https://www.upo.es/investiga/urbanimpacts/en/catalogue/#/ (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Burchell, R.W.; Listokin, G.S.; Hughes, J.W.; Stephen, C.C. Measuring urban distress: A summary of the major urban hardship indices and resource allocation systems. In Cities under Stress: The Fiscal Crises of Urban America; Burchell, R.W., Listokin, D., Eds.; Rutgers University, Center for Urban Policy Research: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 159–229. ISBN 0882850644. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, C.J.; Mateos, C.; Rodríguez, M.J. Cultural Scenes, the Creative Class and Development in Spanish Municipalities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2014, 21, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Yáñez, C.J. Do ‘Creative Cities’ Have a Dark Side? Cultural Scenes and Socioeconomic Status in Barcelona and Madrid (1991–2001). Cities 2013, 35, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect Size Estimates: Current Use, Calculations, and Interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakens, D.; Bakker, M. Calculating and Reporting Effect Sizes to Facilitate Cumulative Science: A Practical Primer for t-Tests and ANOVAs. Article 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. The Effect Size Index: D. In Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; Volume 2, pp. 284–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, L.V. Distribution Theory for Glass’s Estimator of Effect Size and Related Estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 1981, 6, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V.; Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 0080570658. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Salinas, V. Los Centros Históricos En La Evolución de La Ciudad Europea Desde Los Años Setenta. Ería: Rev. Cuatrimest. Geogr. 1994, 34, 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.M.; Lois-González, R.C. The Historic Centre in Spanish Industrial and Post-Industrial Cities. Open Urban. Stud. J. 2010, 3, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio del Val, J. Rehabilitación Urbana En España (1989–2010). Barreras Actuales y Sugerencias Para Su Eliminación. Inf. Constr. 2011, 63, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.N. Research in Urban Policy. In The City as an Entertainment Machine; Nichols Clark, T., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2003; Volume 9, ISBN 0739124226. [Google Scholar]

- Servillo, L.; Atkinson, R.; Russo, A.P. Territorial Attractiveness in EU Urban and Spatial Policy: A Critical Review and Future Research Agenda. Eur. Urban. Reg. Stud. 2012, 19, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.J. Políticas de Regeneración Urbana En España En El Marco de Las Iniciativas de La Unión Europe. Pap. Regió Metrop. Barc. Territ. Estratègies Planejament 2020, 63, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, C.J.; Echaves García, A.; Guerrero Panal, G.; Mateos Mora, C.; Rodríguez García, M.J.; Moya Alfonso, R.; Zapata Moya, Á.R. Mejorar La Ciudad Transformando Sus Barrios. In Regeneración Urbana En Andalucía (1990–2015); Centro de Sociología y Políticas Locales, Universidad Pablo de Olavide: Seville, Spain, 2016; ISBN 978-84-608-8550-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Garcia, M. Urban Regeneration Policies Promoted by the EU in Spain. A Comparative Analysis on the “Offer Model” of URBAN and Urbana Initiatives in Diverse Contexts. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Seville, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- de Gregorio Hurtado, S. La Iniciativa Comunitaria URBAN Como Factor de Transformación de La Práctica de La Regeneración Urbana: Aproximación al Caso Español. Ciudad. Territorio. Estud. Territ. 2014, XLVI 180, 253–275. [Google Scholar]

- de Gregorio Hurtado, S. Understanding the Influence of EU Urban Policy in Spanish Cities: The Case of Málaga. Urban. Res. Pract. 2019, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Yáñez, C.J.; Rodríguez-García, M.J.; Guerrero-Mayo, M.J. Evaluating the Quality of Urban Development Plans Promoted by the European Union: The URBAN and URBANA Initiatives in Spain (1994–2013). Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 149, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbact. URBACT III Programme Implementation Evaluation; URBACT Joint Secretariat: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rus, P.; Nared, J.; Bojnec, Š. Forms, Areas, and Spatial Characteristics of Intermunicipal Cooperation in the Ljubljana Urban Region. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2018, 58, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmankiewicz, M.; Campbell, A. From Single-Use Community Facilities Support to Integrated Sustainable Development: The Aims of Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Poland, 1990–2018. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).