Abstract

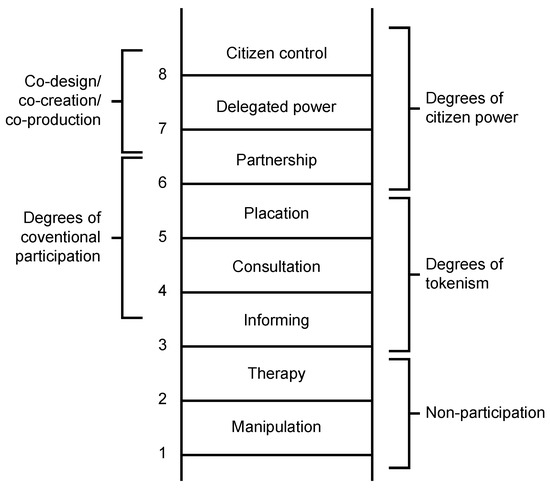

The outdated and discredited notion of a binary urban–rural divide remains stubbornly widely used. However, it both sets up and reflects oppositional politics and processes between the two supposedly mutually exclusive categories of space and place, which hamper urban–rural partnerships. Empirical reality on the ground is far more complex. Just as more appropriate conceptualisations and approaches have evolved, so new research methods and tools have been developed to overcome the different institutional barriers and stakeholder priorities in the face of contemporary real-world complexities and the urgency of tackling the ‘wicked’ challenges of sustainability, which also underpin the New Leipzig Charter. The focus here is on co-production and related methods, which can be considered as representing the top-most rungs of Arnstein’s (1969) Ladder of Participation. The relevance and application of these methods are exemplified from the work of Mistra Urban Futures in relation to transcending conventional European urban–rural divisions and forming partnerships, with due attention to problems and limitations. Such methods have considerable potential, including for addressing unequal power relations, but are time-consuming and require careful adaptation to each situation.

1. Introduction

Urban–rural partnerships of diverse kinds are increasingly important and urgent to help address today’s profound global challenges, many of which are transboundary in nature. This requires an appropriate vision as well as tools capable of overcoming the obstacles to effective governance and management posed by the often outdated and inadequate conceptualisations, approaches, policies and methods on which most practitioners and academics still rely. This paper analyses these issues in turn, drawing on global literature and experience to explain their relevance to implementation of the New Leipzig Charter, adopted in late 2020, in the European context.

Since the 1990s, more appropriate conceptualisations of urban–rural relationships than the simplistic and discredited traditional urban–rural dichotomy have centred on a spectrum or continuum of conditions across space. This may vary in gradient rather than being isotropic—i.e., having an even gradient—between places that everyone would unequivocally characterize as urban at one extreme and as rural at the other. The notion of a peri-urban transition or interface zone within that continuum is now widely accepted and is being applied in many parts of the world [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

In contexts of rapid urbanisation and urban growth, peri-urbanisation usually means a process of transition whereby a previously rural area beyond a city progressively acquires a mix of land uses and functions conventionally associated with both rural and urban areas. The process is dynamic, with the proportion of urban activities increasing, and often ends in such a zone becoming physically and visually urban, even if its legal and institutional status remains unchanged. Meanwhile, the urban fringe or edge moves further out into previously rural land. Depending on wider politico-economic conditions, however, the process may stall, so that the mixture of land uses becomes a more enduring feature. Even in the relatively stable urban areas of Europe, North America and Japan, abrupt urban edges or fringes are relatively rare nowadays, and longstanding peri-urban transition zones more accurately describe the mix of land uses now found there [5,6,10,11,12].

The precise legal/administrative situations vary by region and country, but large cities almost invariably comprise multiple local governments (or authorities), such as municipalities or districts. Those established in or for urban areas are defined as urban, while those established in previously rural or peri-urban areas but now absorbed into a city have often not evolved to match their current situations. Hence the constituent local government units in a city—and even more in a larger functional city region—commonly possess substantially different sets of powers, responsibilities, capabilities and revenue sources. This underlines the importance of having a strategic metropolitan or city regional governance structure to co-ordinate and ensure a coherent and effective operation in relation to transboundary infrastructure, services and policies among the constituent local authorities (e.g., [13]). Similar issues arise regarding the division of powers, responsibilities and resources between national, regional and local authorities to ensure effective multi-level (or multi-/cross-scale) governance.

Official governance structures and processes are generally rigid and unable to keep pace with changing situations and needs. This is particularly true nowadays, with a growing number of important and often intractable or ‘wicked’ transboundary challenges because they are so difficult to tackle effectively. Key examples include sustainability (including biodiversity) and climate/environmental change; the unprecedented mobility of people, goods, services and finance; and global health epi- and pandemics—such as avian influenza, Ebola, dengue fever and currently COVID-19. When these become linked, they are especially challenging. One particularly relevant challenge arising from the foregoing relates to the establishment and development of urban–rural partnerships to address these transboundary issues in the context of unequal powers, resources and capacity among the many organisations, stakeholder groups and different categories of local government.

The European Union context: The URP2020 conference in Leipzig in November 2020 highlighted the importance of urban–rural partnerships to meet current sustainability and other ‘wicked’ problems within the European Union (EU). The New Leipzig Charter (EU 2020), which was launched at the same time, seeks to provide a way forward to meet such urban sustainability challenges within a changing Europe characterised by diverse and dynamic urban–rural conditions, within which some areas are urbanising rapidly, while others are stable, ‘mature’ or even declining. The recent experience of the city of Leipzig itself exemplifies what effective and coherent action can achieve in terms of regeneration in the wake of industrial obsolescence and political change by bringing diverse stakeholders together to discover that, despite antagonisms and even conflicting priorities, there is much to be gained by co-operating and co-creating [14,15].

The tools required to achieve such progress and to embrace different stakeholders, regardless of what kind of local government unit they live within, are very different from the conventional planning tools associated with technocratic, modernist and generally top–down planning and management. Despite local variations, existing formats of public consultations about proposed (re-)development schemes illustrate the point well. These are widely felt to be inadequate, often merely serving to confirm or validate limited choices among a small set of alternatives pre-determined by professional planning officials and/or elected representatives. Residents and users—and, importantly, different sub-groups and minorities among them defined in different ways—are rarely asked about their aspirations and priorities for the future of their neighbourhoods or other parts of the city. Hence public participation rates are generally low, and the exercises are perceived as having little relevance or even as being patronising.

To transcend this kind of impasse and give meaning to the transformative and participatory spirit, as well as letter, of the New Leipzig Charter [16], it is essential to refresh and update existing partnerships and to forge new single- and multi-purpose alliances, including those addressing urban–rural relations. This necessity is emphasized in all elements of the 2015–2016 global sustainability agenda, including the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction; 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (of which the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are the key monitoring and evaluation toolkit); COP 21 Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; and the New Urban Agenda (NUA). Underpinning all these is the principle of inclusivity and of ‘leaving no one behind’. The SDGs and NUA will be returned to below.

The New Leipzig Charter; The transformative power of cities for the common good [16] has been updated from the original 2007 version [17]—which focused on measures to promote ‘the sustainable European city’—to ensure consistency with these recent global agendas and newer perspectives and approaches, including urban transformation. To this end, it explicitly recognizes the importance of responsive and interdependent multi-level governance that integrates individual neighbourhoods with local authorities and functional city regions, which embody urban–rural dynamics and relations:

In parts this covers a metropolitan area or a combination of other territorial entities. In order to adapt urban policies to people’s daily lives,

… towns and cities need to cooperate and coordinate their policies and instruments with their surrounding suburban and rural areas on policies for housing, commercial areas, mobility, services, green and blue infrastructure, material flows, local and regional food systems and energy supply, among others[16] (p. 3; my emphasis added).

Here, then, is explicit recognition of both vertical and horizontal functional and governance interdependencies, and the complexity of collaboration and co-ordination in practice across very different kinds of politico-administrative jurisdictions. The Charter goes on to explain the vision of urban transformation as comprising the social, ecological and economic dimensions of sustainable development—also termed the just, green and productive dimensions [16] (pp. 3–5).

The Charter’s explicitly normative vision of future European cities is wholly consistent with contemporary perspectives on integrated and holistic sustainable urban transformations, which embrace social justice and equity/redistribution issues alongside environmental and economic productive sustainability (e.g., [18,19]). All these concepts and requirements are very challenging, even once they have crossed the thresholds of political acceptability and legitimacy by being incorporated into such high-level strategic documents and commitments.

One additional challenge is that SDG11, on sustainable cities and communities, is naturally geared to urban conditions. While, like Agenda 2030 as a whole, it does recognise the integral nature of functional relations and interdependencies beyond a city’s limits, how the Goal’s targets and indicators will be measured in peri-urban and rural localities within a functional city region that fall within non-urban local government jurisdictions, still requires research and experimentation. Europe is ideally placed to undertake such experimentation, which will also help to progress implementation of the Leipzig Charter. The NUA also explicitly recognises that cities form integral components of sustainable regions and countries [20]. Indeed, its three transformative commitments—namely, social inclusion and ending poverty; inclusive urban prosperity and opportunities for all; and environmentally sustainable and resilient urban development—apply equally well at this scale and to the urban–rural partnerships that are in focus here. Moreover, because the NUA lacks specific means of implementation, monitoring and evaluation of its own—a role to be fulfilled by the SDGs—no additional challenges in the context of urban–rural partnerships arise from the NUA.

The rest of this paper sets out and assesses the very different toolkit required to tackle these challenges. The next section explains the limitations of conventional methods in greater detail, while the third section delves into co-creation, co-design and co-production methods, providing relevant examples from the experience of Mistra Urban Futures (2010–2019), the international centre on urban sustainability headquartered in Gothenburg, Sweden [21]. Section 4 assesses the potential of such methods, including various challenges and limitations, while the concluding section pulls together the various threads and underlines the importance of using sustainable methods to achieve sustainability.

2. Rising to the Challenge: The Need for an Appropriate Conceptual Approach

If conventional urban planning and management tools are already inadequate and lacking in credibility, they are certainly not up to the job of implementing such bold visions and bringing about substantially different, more sustainable, integrated and equitable urban, peri-urban and rural places. Diverse groups of inhabitants and economic actors need to be involved through substantively increased active participation at all stages from conceptualization to implementation. To this end, ‘deep’ (as opposed to superficially) participatory methods and especially co-productive or co-creative tools are particularly appropriate. These correspond to the top-most rungs (Nos. 6 to 8) of a slightly modified version of Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation [22] (Figure 1), which identifies the full spectrum from ‘manipulation’ at the bottom to ‘citizen control’ at the top. These are categorised in different ways on the basis of direct research experience, as indicated by the labels to the left and right of the ladder.

Figure 1.

Author’s modified version of Arnstein’s (1969) Ladder of Participation (Adapted from [22]).

The challenge should not be underestimated because, as Tony Bebbington [23] (p. 281) put it,

… theorising participatory development [and hence, by extension, even more so co-production] necessarily requires an engagement with practices that pose awkward questions about attitudes and behaviours… unexpected outcomes, and normative commitments. Meanwhile, practising participation necessarily requires engagement with theories that pose difficult questions and challenges, that force the practitioner never to lose sight of the wider picture….

Acknowledging the shortcomings of the conventional tools and methods is important as the rationale for developing a fundamentally different toolkit. Existing processes and methods have an overwhelming short- or medium-term timeline of generally not more than five years. This reflects the institutionalisation of linked electoral, planning and budget cycles in most societies, which often triggers rapid changes when political control shifts at elections. These planning and budget cycles are also usually fundamentally sectoral in nature, being aggregated to produce an overall plan or budget, rather than being undertaken on an integrated basis. However, such approaches, and the associated gaps, intersectoral and policy disjunctures and volatility, are particularly unsuited to the far longer integrated strategic planning time horizons of perhaps 20–30 years required to tackle the wicked societal challenges such as economic restructuring, climate change and urban or territorial sustainability.

Such institutional timelines and cycles will be extremely hard to alter, if only because of the inertia and interests vested in long-established political and bureaucratic processes and procedures. A different way of working across sectoral and political party lines is therefore essential if the challenges are to be met, so that the foundations laid during one cycle and are not then ripped out or ignored in subsequent cycles but instead are built upon. This requires important elements of consensus or alliance building that are often unfamiliar in relation to how most current systems operate. A different, co-creative approach has the potential to overcome this immediate problem, as I argue in the next section.

The value of participatory research and service design/delivery has long been recognised and numerous approaches and methods have been developed since at least the 1980s, perhaps most prominently in relation to rural but also some urban development interventions in poor countries. They have also been adapted to diverse rural and urban contexts worldwide, although explicitly urban–rural participatory engagement has been rare. These approaches differ in the depth and extent of citizen or beneficiary participation, with the most sustainable interventions usually being those where participation has been sufficient to generate a sense of buy-in or ‘ownership’. This was/is not a specific school of thought but a diverse movement, inspired by figures including Robert Chambers [24,25,26] and the late Manfred Max-Neef, the Chilean economist, who advocated human-scale development [27,28]. Such approaches therefore became de rigeur and were required by many funding and donor agencies. However, ‘quick and dirty’ versions of slow and deeply participatory methods were often deployed in the interests of rapid delivery to meet donors’ budget or planning cycle deadlines. This devalued and discredited such approaches, leading to accusations that a ‘tyranny of participation’ had arisen and spawning efforts to chart new paths to more substantive transformatory approaches [29,30] based on co-creation/-production, to which the paper now turns.

3. Methods and Materials: Transdisciplinary Co-Creation, Co-Design and Co-Production

Alongside such participatory initiatives arose what are now termed methods of co-creation, co-design and co-production, which are fundamentally different approaches from conventional methods. They seek to establish a level playing field for all participants, regardless of which stakeholder group they belong to and what level of professional or lay expertise they possess. As such, these approaches share a normative philosophical position with poststructuralist theories and methods, namely, that all forms of knowledge and experience have value and can contribute to solving the problem(s) at hand. Hence these approaches aim to decentre (usually western) expert knowledge in favour of multiple, plural (including indigenous and lay) and particularly hybrid forms of knowledge that combine elements of different knowledges into new forms.

Working with such diverse forms of knowledge held by different stakeholder groups makes such approaches, by definition, also transdisciplinary. This distinguishes them from inter- or multi-disciplinary engagements, which bring together different academic or professional disciplines. Transdisciplinarity also has diverse roots, ranging from ‘alternative’ and heterodox economics and development, e.g., [31], to joint service planning and delivery with local authorities, and is now an increasingly important movement in relation to research and policy [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. As with other participatory methods, they have to date usually been applied in either urban or rural settings, but conceptually they are well suited to spanning urban–rural relations, as I will explore further below.

Linked to their profoundly different epistemologies of knowledge—i.e., assumptions and starting points—compared to conventional methods, transdisciplinary co-creation, co-design and co-production methods (henceforth collectively referred to here as co-production for simplicity) do not produce blueprints or templates for replication. Instead, each situation and research team is regarded as distinctive and requires a bespoke process to be undertaken by the participants to work out their common ground, priorities and the methods appropriate to the problem at hand.

There is a wide range of methods, developed and adapted to diverse situations but all sharing these key features [33,35,38,42,43,44,45]. This provides the substantive active engagement required for buy-in and shared ownership of the process and outcomes, which increases substantially the prospects for successful implementation and sustainability of the results. Conversely, this certainly adds considerably to the time requirements and uncertainties of the process. It may also create difficulties in maintaining active engagement and participation by all team members, especially for those for whom participation raises direct opportunity costs and trade-offs. The tools to help maintain involvement and momentum are discussed below.

Accordingly, such methods are held to be appropriate and to provide new opportunities for tackling complex and intractable ‘wicked’ societal challenges. Their transformatory potential in this regard appears promising on the basis of experiences to date in diverse contexts worldwide, straddling both the global North and South [33,35,39,41,42,43,44,46,47,48,49,50]. However, building up a broader evidence base—including on urban–rural partnerships—is urgent. Although there is no specific limit to the number of participants and stakeholders in a project team, the complexity of the process does increase with team size. Another key advantage of such approaches is that they can serve as effective tools for addressing transboundary service delivery and research issues within a city region or across the urban–rural spectrum because they are appropriate to building teams that straddle administrative, political or other jurisdictional boundaries. The essential prerequisite is that the respective communities, local authorities and other organisations, institutions and key individuals are willing to commit to such a process; but, careful consideration by the initiators of whom to include in the initial discussions on the basis of relevance and inclusivity is important [35,43].

For the chances of success in co-productive research projects to be maximised, it is therefore important that no single or subset of participating organisations ‘owns’ or is perceived to own the process and its outcomes. Experience shows that if that happens, other parties may lose momentum or interest, jeopardising the rationale and potential outcomes. This can be avoided by hammering out ground rules at the outset, including agreement regarding shared ownership of the intellectual property produced by all participating bodies, regardless of size, effective power or resources contributed to the process. That said, local authorities have sometimes led successful co-production exercises to improve the relevance and appropriateness of their service delivery [42,51], while there are examples of top–down co-creation experiments led by local authorities [52].

It is also important to acknowledge that both subtle and overt power relations do exist and must be mediated to ensure that all voices are heard and are not silenced or drowned out by vocal participants or representatives of more powerful bodies. Furthermore, most, if not all, participants are likely to be unfamiliar with the co-production approach and having to negotiate and collaborate with people from diverse organisations, including some that are likely to be in structural opposition to their own. Hence recognising that most participants will be outside their normal comfort zones and making efforts to put them at ease through the initial stages is important.

For these reasons, it is often advantageous to utilise an external—ideally professional—facilitator. This is one of the building blocks or forms of ‘supporting infrastructure’ found valuable in safeguarding and supporting transdisciplinary co-production processes [38,43,53,54]. Devoting adequate time and effort in the inception stages of transdisciplinary co-production projects to establish the ground rules with which everyone is comfortable is essential to build confidence and mutual trust as the basis for developing later momentum. Key issues in this regard include agreeing to share ownership of the intellectual property to be created, and identifying and understanding the often-conflicting rationalities of different professions and stakeholders [43,55,56].

An example of conflicting rationalities would be the diverse ways in which different professions and other urban and non-urban actors perceive the same problem of river flooding in urban areas, as has become an increasingly dramatic climate change challenge in many European (and other) countries:

- An urban planner might see the heart of the problem as being inappropriate construction within a floodplain without remedial and diversionary measures.

- By contrast, a hydraulic engineer would focus on the inadequacy of embankments, stormwater drainage capacity and the presence of old bridges or other structures that impede river flow or trap logs and other material carried downstream by the flood.

- A biogeographer or urban ecologist would focus on the inadequacy of blue and green infrastructure and permeable surfaces in the city to increase rainfall penetration into the soil and reduce run-off.

- A disaster risk reduction or emergency response professional would focus on the adequacy of early warning systems, rescue and evacuation protocols and stocks of emergency food and relief supplies.

- On the other hand, neighbourhood residents’ associations would be concerned with some or all of these issues as they affect their particular community rather than having a strategic focus on the city as a whole.

- Farmers and forestry officials up- and downstream of the urban area would focus on flood mitigation and remediation affecting their lands, livelihoods and resources.

- Hotel and leisure industry operators up- and downstream of the urban area would be concerned primarily with flood mitigation and the security of road/rail infrastructure to provide access to their facilities, and hence their investments and livelihoods.

- A regional official will be concerned with the upstream causes and downstream consequences of both the existing flooding and remedial action taken to address it.

Another and more durable form of facilitation or ‘active intermediation’ can be provided by a ‘boundary’ or boundary-crossing’ organisation that is separate from the respective stakeholders, and the offices of which provide a more neutral or ‘safe’ space in which team members can engage. Experience shows that being in their normal work environments, literally embedded within the day-to-day workplace pressures and power relations, can be inhibiting to thinking and engaging ‘outside the box’. Hence, having such a resource organisation, which can also provide direct facilitation, served Mistra Urban Futures and various other transdisciplinary co-production teams well [33], [39] (pp. 6–10), [43] (pp. 31–47) and [54].

Diverse Examples of Appropriate Co-Production Methods

As explained above, it is important to develop or adapt methods to suit the particular situation. To assist readers in understanding the range of possibilities, Table 1 contains a selection of different types of methods utilised by at least one Europe-based team within the Mistra Urban Futures international research centre on urban sustainability. These are a combination of single-city and comparative cross-city methods, as explained briefly in the following text. All share the objective of bringing together and building a shared understanding of the common goal and ethos among a diverse transdisciplinary group in order to produce integrated knowledge [43] (Chapter 4). A priori, especially given the need for adaptation to particular local circumstances in any event, there is no reason to expect that they would not be appropriate to urban–rural or regional contexts. Accordingly, their respective key features are explained as encouragement for readers to experiment and build up relevant experience in practice.

Table 1.

Selection of co-production methods utilised by Mistra Urban Futures.

Symmetrical leadership and participation worked well in relation to some projects among a set of local and regional government bodies, national research agencies and universities in Gothenburg, Sweden, where the principal differences were between academic and various professional knowledges, in both cases spanning different disciplines and sectors. Without minimising the differences that existed, it was felt that the group was relatively symmetrical in terms of these knowledges and their epistemologies. Hence the joint leadership by a senior university researcher and senior city practitioner from the municipality worked effectively, starting with intensive ground-breaking and familiarization activities and continuing throughout the project. Rotating chairmanship, regular meetings and ongoing feedback activities served the project well in building mutual respect and enabling production of appropriate deliverables [43] (pp. 101–103). This method could therefore be utilised effectively in the context of urban–rural partnerships where professionals of comparable expertise levels and experience are involved from across diverse organisations and institutions, provided that the respective institutional contexts are adequately explored during the early stages.

Iterative design thinking was used successfully by the group of stakeholder institutions working to develop a joint formulation of the problem and then a solution in the forms of a funding application and later a work plan to establish a node of Mistra Urban Futures in Stockholm, Sweden. This challenge-led approach originates from the field of design and has been developed to address practical problems through a 5-stage process, starting with the specific, then generalising, before reverting again to the specific in a sequence resembling a ‘double diamond’ [43] (pp. 103–105). Like the previous method, this works well in a situation of relatively symmetrical power relations and some shared understandings. Perhaps, therefore, the opportunities to deploy it in urban–rural partnership contexts may again be greatest among professionals from different stakeholder groups or organisations, where comparable levels of expertise and experience might exist. Beyond that, it probably has more limited relevance.

Study circles and co-writing is another method used successfully in Gothenburg that brought together academics, the local authority and other public sector officials and was also jointly chaired by an academic and civil servant. The objective was to address the social dimensions of sustainability in the city, a particularly urgent challenge in the context of the increasing segregation, inequalities of income and health and falling political participation. Three substantial workshops with the interested participants helped to frame the project around understanding the underlying drivers and conflicting goals of the problems identified. Theoretical and practical experience were contributed by the respective participants en route to defining key questions and then three sub-projects to address them. Working groups comprising both academic researchers and civil servants iterated ideas and co-wrote eight mental shifts or changes in outlook required to address the challenges. Gaining an understanding of the working environment and conditions of other stakeholders was also an important ingredient [43] (pp. 106–111). This last point highlights that the method should be able to work effectively in different contexts, including urban–rural partnerships, though some of the elements might require more time in view of the wider diversity of contexts and working environments.

As indicated above, and discussed further in the next section, many co-production methods are very time consuming and hence difficult to implement in contexts where time and staff capacity are often key constraints. Mistra Urban Futures’ Sheffield–Manchester team has experimented with methods to address this through academic researchers working with local government officials and some civil society members. One pertinent example utilised three carefully organised and structured complementary international study visits within a year to the international Mistra Urban Futures conference in Cape Town, to an international participatory democracy conference in Barcelona, and to their municipal counterparts in Gothenburg. Active co-productive learning was pursued during and after each visit through organised meetings and reflection in groups, individually and by means of interviews, to use the insights gained from other contexts to improve their understanding of the situations, constraints and other possibilities in their own city. The main foci were citizen involvement in decision-making and deep reflection on policy and practice in their own context. These led in turn to discussions about what the prerequisites would be for implementing alternatives that were deemed desirable and possible. This was dubbed ‘learning from the outside in’ to co-produce practicable conclusions and tools. It built on longstanding co-productive relations and the associated trust between the academic researchers and local authority gatekeepers but, even so, the former needed to be active intermediaries in promoting shared learning within the local authority organization [43] (pp. 129–134) [56]. This method could easily be adapted to help establish or deepen urban–rural partnerships by including participants from different urban, peri-urban and rural jurisdictions/local authorities, or working in different localities for a utility firm or other agency, just as this team comprised participants from different boroughs within Greater Manchester.

In another experiment by the Sheffield–Manchester team, the well-known model of a citizens’ jury, in which a random, diverse group of local residents hears presentations by a set of experts and deliberate on recommendations, which are then disseminated to the wider public and key stakeholders, designed to shift official practice, was turned inside out for the purpose of improving the care at home of elderly relatives. This was designed to coincide with an official review of such care and intended to mobilise the experience of diverse healthcare professionals with the existing model as a way of co-producing alternative visions. Hence, healthcare professionals from different fields and levels of seniority were recruited to deliberate as a jury through six sessions on testimony from home care givers and service users in a context removed from their normal work environments and with the assistance of two facilitators. It proved successful, demonstrating the value of such co-productive processes within professional organisations and bodies. The process and its recommendations were both taken up by the senior officials responsible for healthcare [43] (pp. 150–154). Such an inverted jury process could readily be established, comprising professionals located within different jurisdictions within an urban region or other context to combine urban–rural relations and facilitate partnership formation.

My final example is a comparative project across seven cities on four continents—including three in Europe (Gothenburg and Malmö in Sweden, and Sheffield in the UK)—in which Mistra Urban Futures worked. It was designed to understand and facilitate engagement with and uptake of the targets and indicators of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 and the New Urban Agenda (NUA). Given the global nature of this agenda, the project was designed by the Centre’s Secretariat but with the essential flexibility to enable local co-productive implementation according to the circumstances and level of buy-in and interest within each municipality to work with an academic researcher. In Cape Town, the researcher was embedded within the municipality as part of a longstanding collaborative arrangement, while the researcher in Malmö held joint appointments in the university and municipality. There was considerable variation across the cities in terms of the level of municipal engagement, relating to both local factors (such as use of existing indicator sets felt to be comparably appropriate or appreciation of the value of the SDGs in governance for sustainability as well as just in monitoring) or having a well-placed ‘champion’, and national considerations, such as awaiting national guidance on local authority reporting. This underlined the importance of a multi-level governance perspective [57], which is highly pertinent to the issue of urban–rural partnerships (see below). The researchers were able to add research capacity, to provide in-depth assessments of how various municipal policies could be mapped onto the SDGs, and to provide comparative insights from the other cities. Establishment of a peer-to-peer learning network among the city teams, which met face to face annually and online, also proved particularly valuable for information sharing and enhancing their understanding about the different approaches to the same problems being adopted in the various cities [43] (pp. 122–128), [58,59,60,61] (See Supplementary). This is an excellent example of an approach eminently suitable for use with both individual and groups of rural as well as urban local/regional governments and other organisations. In the regional or even national sectoral contexts, these would span the urban, peri-urban and rural categories of government and community institutions, as required in terms of meaningful urban–rural partnerships.

4. Discussion and Limitations

In the context of this Special Issue from the URP2020 conference [62] and implementation of the New Leipzig Charter, one notable benefit of transdisciplinary co-production methods is their flexibility to different contexts and situations, provided that appropriate adaptations are made. Hence, although the examples above were developed for urban applications, such methods are equally amenable to use across jurisdictions of different types and with any number of stakeholder groups within urban, peri-urban and rural contexts, or combinations of these. They could be used to bring together stakeholders in one sector/industry or from several to promote integrated thought, research and action.

The brief summaries in the previous section are intended merely to illustrate some of the relevant methods of transdisciplinary co-production that have been utilised in different contexts to address specific sustainability challenges that are not amenable to conventional methods and solutions. In each case, a process of discussion and reflection led to the identification of several potential methods that might appropriate and hence enable progress in that context by breaking down barriers, forging shared understandings and providing opportunities to learn and formulate suitable ways forward jointly. Final decisions followed detailed discussion of the pros and cons of each in relation to the particular situation and what level of adaptation would be required to make them useful and acceptable. Sometimes short trials were also used in making the final choice. These are important steps to follow since “[c]ontext is everything and it is therefore essential to start by reading and reflecting on the contextual information and guidelines provided regarding what the authors see as key factors or attributes that make the methods successful where they were developed” [43] (p. 167).

Provision of training at the outset is also crucial so that participants understand and can gain sufficient appreciation of the tools not to become frustrated and distracted from the purpose. This is most effectively done by a facilitator or boundary-crossing/active intermediary organization. Applying such a method in the context of research is itself experimental and a learning process—which adds novelty and originality as well as enhancing a sense of bridge building among participants from different organisations and stakeholder groups and developing that crucial sense of joint ownership of both the process and outcomes. Including regular time for reflection and modification if necessary is an important part of any implementation process.

Inevitably, however, such methods will not suit all situations or participants. This underlines the importance of adequate initial thought and discussion. It is also important to acknowledge several challenges and limitations in relation to these methods, which may be encountered individually or jointly.

First, as already explained, the essence of transdisciplinary co-production approaches is inclusivity and appropriateness. This militates against the use of blueprints or templates to formalise, regularise or speed up projects but requires that each initiative or project should be individualised to reflect the particular context and circumstances. This puts a premium on effective leadership and facilitation (see the sixth limitation below).

Second, and following directly from this, the start-up and ongoing transaction costs are higher than with conventional projects and methods where greater replicability is possible. Some of the inception challenges regarding whom to include, the need to negotiate and understand conflicting rationalities, the priorities and relative power of the respective stakeholders, hammering out a joint methodology, and of maintaining active participation and engagement by all participants have already been explained.

Third, it follows logically that such processes make project timelines and the eventual outcomes more uncertain and difficult to predict accurately. This applies even when due care and attention are applied during the start-up phase, and means that some stakeholders will not wish to embark on such a process. Adjustments to expectations and budget, project and reporting cycle deadlines will need to be negotiated—which will not be equally easy or even feasible for all stakeholders.

One way that Mistra Urban Futures addressed this problem was to operate by means of formal multi-stakeholder agreements (memoranda of understanding or agreement, contracts and the like, depending on the situation), which provided assurance of institutional moral, political and resource support to the individual participants. These took time to negotiate and update or renew for successive programme funding phases but did then facilitate and speed up project-specific formalities and the design of co-production processes under their aegis [39], ([43] Chapter 4). Having brought numerous projects to remarkably successful conclusion in recent years, both within Mistra Urban Futures and other programmes [33,35], illustrates how far we have come in the few years since Voorberg et al. [44] highlighted the lack of attention in the co-production literature to outcomes.

Fourth, a key challenge underpinning the previous limitations is the imperative of overcoming short-termism and self-interest by participating individuals and their respective organisations. Bureaucratic practices and procedures, such as the duration of budget and planning cycles, are often long established and are widely embedded in regulations and legislation, including those that govern the respective powers, responsibilities and financial resourcing of the respective central, regional and local government authorities. They are therefore commensurately difficult to revise. The same applies to current electoral cycles at all levels of government. If commitments to effecting substantive and transformative change to achieve sustainability are therefore to have real meaning, elected representatives will need pressure from their electorates to forge cross-party agreements on certain fundamental commitments in this regard that can be embedded as being ‘above party politics’ in order to serve as building blocks for sustainability across successive electoral cycles. Achieving this may well be easier in systems with proportional representation and/or traditions of coalition governance than in adversarial, first-past-the-post systems.

Fifth, the collaborative relations required among participating stakeholders and measures already mentioned to ensure and maintain active participation can lead to frustration among key professional officials in local authorities or other public bodies and agencies who feel that their training and expertise are undervalued relative to all the other voices and perspectives having to be accommodated. They sometimes also feel that the duration of co-production is an unnecessary luxury and/or that the outcomes and outputs may be sub-optimal in terms of their professional training and judgements. Some initial training, as for all participants, in relation to key parameters of the approach and how to manage expectations is often very helpful, while an element of choice as to which professional officers join a project also provides flexibility for those well disposed towards the approach to volunteer or agree to serve.

Sixth, as already identified above, the duration and challenges of co-production processes put a premium on facilitation and leadership to retain interest and participation by all team members. Identifying, understanding and accommodating the various voices, disciplines and competing rationalities during the inception phase as the basis for working forwards is crucial, along with ongoing facilitation and active intermediation [43] (pp. 31–47), [54,55,56]—what one might call the ‘zen of relationship maintenance’.

Finally, a corollary of the distinctiveness of each situation and project, along with the importance of building and maintaining interpersonal trust to underpin effective working relations, is that co-production approaches are unlikely to be scalable. They work best in the context of relatively small teams, where face-to-face and trustful relationships can develop and then be built upon. Experience shows that even when a member leaves the team due to being assigned a new role or leaving the organisation, the replacement may not fit in immediately and will have to work hard to ‘catch up’, forge effective interpersonal working relationships and build trust [39,43].

5. Conclusions

Pulling together the threads of this paper requires a few concluding observations. First, urban–rural partnerships, as elaborated in the URP2020 conference [62] and the New Leipzig Charter [16], exemplify the context of current sustainability challenges in that they involve many and diverse, unequal stakeholder groups and organisations and also straddle numerous politico-administrative boundaries. As such there are often no, or only inadequate, mechanisms and processes for seeking to address such transboundary issues, the number, scale and scope of which have been increasing lately and which constitute classic ‘wicked societal problems’.

Second, another common reason for the intractability of urban regional sustainability problems is that many existing political institutions and processes operate along traditional lines and have lost credibility among at least some residents because they are perceived as being too bureaucratic, top-down and unrepresentative, often defending vested interests rather than being forward-looking. Most urban planning processes fit this picture because they are expert-led and do not engage residents or the wider public adequately. Even when public consultations are held, these tend to have limited scope, merely offering residents a choice among a few alternative schemes proposed by the planners as meeting mainly technical criteria. Alternative suggestions are not invited and there is no possibility to reject them all as not meeting local needs or priorities. Low voter turnouts in many local and regional elections reflect their perceptions of reduced relevance and powerlessness.

Third, such situations perpetuate the familiar ‘we versus them’ situations of frustration and low perceived relevance. Yet, the importance of finding a way forward in relation to the wicked problems implies the need for very different approaches that can break through these barriers and be truly inclusive of diverse forms of knowledge, ‘ways of knowing’, perceptions and priorities [33,35,39,41,43,44,47].

The diverse body of transdisciplinary co-production approaches—and the positive outcomes—explored in this paper provide a potentially valuable way through this impasse precisely because they are designed to bring together representatives of different community groups and other stakeholders and organisations to explore ways to solve mutual problems by building shared understandings and mutual respect on the basis that all forms and sources of knowledge have potential value. Planners and other technical specialists are one such group, not the only source of expertise. As such, these ‘deep participatory’ approaches constitute a very different epistemology and methodology from conventional procedures and toolkits. The mental shifts required by all parties to accept this and learn to work together to co-design better public services, more appropriate built environments or to find novel solutions to intractable societal problems are considerable. Moreover, and this is my fourth observation, transdisciplinary co-production methods are no magic or silver bullet, capable of solving all the problems straightforwardly. The mere fact of getting—and hopefully keeping—the various interested parties in a room to discuss, negotiate and work together does not mean that implicit or overt interpersonal or institutional power relations simply evaporate. They need to be managed collectively, perhaps steered by an external facilitator and/or boundary-crossing organisation. Even if everyone accepts intellectually that this is necessary and appropriate, ensuring that vocal or forceful individuals learn not to dominate and to ensure that all voices are heard and taken seriously does take time and effort. This is just one of the prerequisites for achieving effective active engagement and joint ownership of both the process and outcomes.

Fifth and a related point is that these methods work on the basis of negotiated and mutually acceptable processes and outcomes. This usually implies seeking consensus, which also takes time but can still prove elusive. It is therefore important that the initial team-building and procedure-defining phase includes discussion and agreement on a mechanism for breaking a deadlock if full consensus is unachievable. This could be a certain proportion of majority vote or a sequential process to agree successive stages of activity or recommendations until a stumbling block is reached, as a way of emphasising agreement over difference.

Finally, the very advantageous character of transdisciplinary co-production projects that requires tailoring to individual circumstances rather than having an off-the-shelf toolkit, also represents their Achilles Heel because of the time and effort required to achieve this and then to run the process to completion. This potential deterrent makes these approaches unsuited to all situations and sets of stakeholders. However, they do provide a fundamentally different way to approach intractable problems by creating a more level playing field, particularly if well facilitated by a skilled professional or a boundary-crossing organisation to create a more neutral space for thinking outside of the box and researching and negotiating away from the respective stakeholders’ normal work environments. How far they do provide game-changing transformative potential to break through the constraints of existing institutional practices and procedures, thus enabling them to tackle long-term societal challenges, requires further research in diverse settings. This recognises the experimental nature of transdisciplinary co-production, and the challenges involved. In the words of Fokdal et al. [33] (pp. 18–19):

[o]ften processes are messy, complex, difficult and time consuming, and there is a large risk of failure. The kind of knowledge produced through these processes, however, is what we need in order to be able to localize the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda (NUA) ….

Supplementary Materials

This paper has no direct Supplementary Materials beyond the various publications cited in the text. Those produced by Mistra Urban Futures are published open access at the URLs indicated; these and unpublished reports are available at www.mistraurbanfutures.org.

Funding

The writing of this paper received no funding. The research by Mistra Urban Futures on which the paper draws was funded by several grants from Mistra, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research; Sida, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency; and the Gothenburg Consortium of organisations (no grant numbers).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the studies reported here.

Data Availability Statement

This paper does not draw on any new primary data; see Supplementary Materials for information on the underlying source reports and publications.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to the organizers of the URP2020 conference, Sigrun Kabisch and Stephan Bartke, who are also the guest co-editors of this Special Issue, for the kind invitation to deliver the closing plenary lecture. They also made the eventual online event accessible and enjoyable. Co-productive research by former colleagues within Mistra Urban Futures and the generosity of the core funders mentioned above is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bartels, L.E.; Bruns, A.; Simon, D. Towards Situated Analyses of Uneven Peri Urbanization: An (Urban) Political Ecology Perspective. Antipode 2020, 52, 1237–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, C.; Wang, M.; Song, Y. Vulnerability and livelihood restoration of landless households after land acquisition: Evidence from peri-urban China. Habitat Int. 2018, 79, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, D.T.; Ziliak, J.P. The rural–urban interface: New patterns of spatial interdependence and inequality in America. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2017, 672, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.S. Peri-urbanism in globalizing China: A study of new urbanism in Dongguan. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2006, 47, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Urban environments: Issues on the peri-urban fringe. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008, 33, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Peri-urbanization. In Palgrave Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Futures; Brears, R., Ed.; SpringerNature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; chap. 192–1; p. 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; Adam-Bradford, A. Hybrid planning in the peri-urban interface: Applying archaeology and contemporary dynamics for more sustainable, resilient cities. In Balanced Urban Development: Options and Strategies for Liveable Cities; Maheshwari, B., Singh, V.P., Thoradeniya, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Frankfurt, Germany; London, UK, 2016; pp. 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simon, D.; McGregor, D.; Nsiah-Gyabaah, K. The changing urban–rural interface of African cities: Definitional issues and an application to Kumasi, Ghana. Environ. Urban. 2004, 16, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; McGregor, D.; Thompson, D. Contemporary perspectives on the peri-urban zones of cities in developing countries. In The Peri-Urban Interface: Approaches to Sustainable Natural and Human Resource Use; McGregor, D., Simon, D., Thompson, D., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2006; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, A. Periurbanization as the institutionalization of place: The case of Japan. Cities 2016, 53, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, B. “Perfectly positioned”: The blurring of urban, suburban, and rural boundaries in a southern community. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2017, 672, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qviström, M. Searching for an open future: Planning history as a means of peri-urban landscape analysis. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 1549–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, RUAF Foundation. A Vision for City Region. Food Systems; Building Sustainable and Resilient City Regions; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4789e.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Kabisch, N. Transformation of urban brownfields through co-creation: The multi-functional Lene-Voigt Park in Leipzig as a case in point. Urban Transform. 2019, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadt Leipzig ‘Leipzig and the Leipzig Charter—On the Way to a Sustainable City’. 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SbifTeLR4jc&feature=emb_logo (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- European Union. The New Leipzig Charter. The Transformative Power of Cities for the Common Good; EU2020.de. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/newsroom/news/2020/12/12-08-2020-new-leipzig-charter-the-transformative-power-of-cities-for-the-common-good (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- European Union. Leipzig Charta Zur Nachhaltigen Europäischen Stadt; Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit (BMUB): Berlin, Germany, 2007; Available online: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Download_PDF/Nationale_Stadtentwicklung/leipzig_charta_de_bf.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Elmqvist, T.; Bai, X.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Griffith, C.; Maddox, D.; McPhearson, T.; Parnell, S.; Romero-Lankao, P.; Simon, D.; Watkins, M. (Eds.) Urban Planet; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Available online: http://www.cambridge.org/9781107196933 (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Simon, D. (Ed.) Rethinking Sustainable Cities; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda; Habitat III. UN: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2019/05/nua-english.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Mistra Urban Futures. Available online: www.mistraturbanfutures.org (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bebbington, A. Theorizing participation and institutional change: Ethnography and political economy. In Participation: From Tyranny to Transformation? Exploring New Approaches to Participation in Development; Hickey, S., Mohan, G., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2004; pp. 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Rural Development: Putting the Last First; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Whose Reality Counts? Putting the First Last; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Can. We Know Better? Reflections for Development; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, M.A.; Elizalde Hevia, A.; Hopenhayn, M. Human scale development: An option for the future. Dev. Dialogue 1989, 1, 5–80. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, M.A.; Elizalde, A.; Hopenhayn, M. Human Scale Development: Conception, Application and Further Reflections; Apex Books: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, B.; Kothari, U. (Eds.) Participation: The New Tyranny; Zed Books: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, S.; Mohan, G. (Eds.) Participation: From Tyranny to Transformation? Exploring New Approaches to Participation in Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, M.A. Foundations of transdisciplinarity. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 53, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bransden, T.; Honingh, M. Distinguishing different types of co-production: A conceptual analysis based on the classical definitions. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokdal, J.; Bina, O.; Chiles, P.; Ojamäe, L.; Paadam, K. Enabling City: Inter—And Transdisciplinary Encounters; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, S.; Pohl, C.; Hering, J.G. Methods and procedures of transdisciplinary knowledge integration: Empirical insights from four thematic synthesis procedures. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, C.; Carpenter, J. (Eds.) Co-Creation in Theory and Practice; Exploring Creativity in the Global North and South; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, C. What is progress in transdisciplinary research? Futures 2011, 43, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polk, M. Transdisciplinary co-production: Designing and testing a transdisciplinary research framework for societal problem solving. Futures 2015, 65, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; Palmer, H.; Smit, W.; Riise, J.; Valencia, S. The challenges of transdisciplinary co-production: From unilocal to comparative research. Environ. Urban. 2018, 30, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simon, D.; Palmer, H.; Riise, J. (Eds.) Comparative Urban. Research from Theory to Practice: Co-Production for Sustainability; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020; Available online: www.oapen.org/search?identifier=1007874 (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Simon, D.; Palmer, H.; Riise, J. (Eds.) Assessment: Learning between theory and practice. In Comparative Urban Research from Theory to Practice: Co-Production for Sustainability; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020; pp. 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Klein, J.; Grossenbacher-Mansuy, W.; Häberli, R.; Bill, A.; Scholz, R.W.; Welti, M. (Eds.) Transdisciplinarity: Joint Problem Solving among Science, Technology, and Society—An Effective Way for Managing Complexity; Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel, Switzerland, 2001; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Durose, C.; Richardson, L. Designing Public Policy for Co-Production: Theory, Practice and Change; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hemström, K.; Simon, D.; Palmer, H.; Perry, B.; Polk, M. Transdisciplinary Knowledge Co-Production. A Guide for Sustainable Cities; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 2021; Available online: practicalactionpublishing.com/book/2544/transdisciplinary-knowledge-co-production-for-sustainable-cities (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolf, G.; Mahaffey, N. Designing difference: Co-production of spaces of potentiality. Urban Plan. 2016, 1, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenk, N.; Meehan, K. Climate change and transdisciplinary science: Problematizing the integration imperative. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 54, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mauser, W.; Klepper, G.; Rice, M.; Schmalzbauer, B.S.; Hackmann, H.; Leemans, R.; Moore, H. Transdisciplinary global change research: The co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pohl, C.; Thompson Klein, J.; Hoffman, S.; Mitchell, C.; Fam, D. Conceptualising transdisciplinary integration as a multidimensional process. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 118, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.; Truffer, B.; Hirsch Hadorn, G. Addressing wicked problems through transdisciplinary research. In The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, 2nd ed.; Frodeman, R., Klein, J.T., Pacheco, R.C.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Tengo, M.; Hill, R.; Malmer, P.; Raymond, C.M.; Spierenburg, M.; Danielsen, F.; Elmqvist, T.; Folke, C. Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond-lessons learned for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Moore, M. Institutionalised co-production: Unorthodox public service delivery in challenging environments. J. Dev. Stud. 2004, 40, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruvot, S. A top-down experiment in co-creation in Greater Paris. In Co-Creation in Theory and Practice; Exploring Creativity in the Global North and South; Horvath, C., Carpenter, J., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020; pp. 137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, A.; Schäfer, M.; Bergmann, M.; Jahn, T.; Marg, O.; Nagy, E.; Ransiek, A.-C.; Theiler, L. Societal effects of transdisciplinary sustainability research—How can they be strengthened during the research process? Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 101, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, H.; Polk, M.; Simon, D.; Hansson, S. Evaluative and enabling infrastructures: Supporting the ability of urban co-production processes to contribute to societal change. Urban Transform. 2020, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, W.; Simon, D.; Durakovic, E.; Dymitrow, M.; Haysom, G.; Hemström, K.; Riise, J. The challenge of conflicting rationalities about urban development: Experiences from Mistra Urban Futures’ transdisciplinary urban research. Trialog 2021, 137, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, V. Conflicting rationalities: Implications for planning theory and ethics. Plan. Theory Pract. 2003, 4, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.; Russell, B. Participatory cities from the ‘outside in’: The value of comparative learning. In Comparative Urban Research from Theory to Practice: Co-Production for Sustainability; Simon, D., Palmer, H., Riise, J., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020; pp. 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Croese, S.; Oloko, M.; Simon, D.; Valencia, S.C. Bringing the global to the local: The challenges of multi-level governance for global policy implementation in Africa. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, S.; Simon, D.; Arfvidsson, H. The double function of SDG indicators: Governance for sustainable urban development. Area Dev. Policy 2019, 4, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valencia, S.; Simon, D.; Croese, S.; Nordqvist, J.; Oloko, M.; Sharma, T.; Taylor Buck, N.; Versace, I. Adapting the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda to the City Level: Initial reflections from a comparative research project. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2019, 11, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valencia, S.C.; Simon, D.; Croese, S.; Diprose, K.; Nordqvist, J.; Oloko, M.; Sharma, T.; Versace, I. Internationally initiated projects with local co-production: Urban Sustainable Development Goal project. In Comparative Urban Research from Theory to Practice: Co-Production for Sustainability; Simon, D., Palmer, H., Riise, J., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020; p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- URP2020 Conference. Available online: www.urp2020.eu (accessed on 18 August 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).