Abstract

This article draws on long-term ethnographic fieldwork to examine some recent livelihood transformations that have taken place in the Turkana region of northern Kenya. In doing so, it discusses some of the ways in which uncertainty and variability have been managed in Turkana to date and considers what this means in relation to a future that promises continued radical economic and ecological change. Discussing a selection of examples, we argue that understandings of contemporary transformative processes are enhanced through attention to the ways in which various forms of knowledge have been constituted and implemented over the long term. We suggest that ongoing transformations within livelihood practices, inter-livelihood relationships and corresponding patterns of mobility might best be understood as manifestations of a long-standing capacity for successfully managing the very uncertainty that characterises daily life.

1. Introduction

This article explores some of the ways in which pastoralist communities in the Turkana region of northern Kenya have negotiated environmental unpredictability over recent decades. Turkana is well known for being hot, arid and ecologically unstable, and the broader region has seen recurring, harsh droughts throughout the last century and beyond [1,2,3,4,5]. Correspondingly, Turkana pastoralism has been characterised as highly dynamic and adaptive, comprising intense mobility and livelihood flexibility in line with a radically transforming array of daily resources and pressures. The Turkana region, which is roughly 68,000 km2, comprises low-lying arid and semi-arid plains, broken sporadically by greener hill ranges (see Figure 1). Precipitation is both low and extremely variable, but after substantial periods of rainfall, various annual grasses emerge that are crucial for those maintaining cattle. Otherwise, livestock browse mixed shrubs, acacia trees and, increasingly, the invasive species Prosopis juliflora, introduced to mitigate desertification by the World Bank in the early 1980s [6,7]. More varied woodlands are found on the banks of major rivers; these are often used as a refuge for small mixed herds of goats and sheep during dry months. During times of extreme scarcity, those who have incurred catastrophic livestock losses are known to seek temporary respite in non-livestock-oriented subsistence procurement strategies, including fishing and cultivation. Whilst longstanding, and indisputably critical to the workings of the regional livestock-oriented economy, these historically subsidiary livelihoods have, over the past few decades, come to be envisaged by many as worthy pursuits in their own rights [8]. Correspondingly, the region has seen a substantial uptick in secondary and further education and associated growth in numbers of small businesses, professionals and those engaged in wage labour.

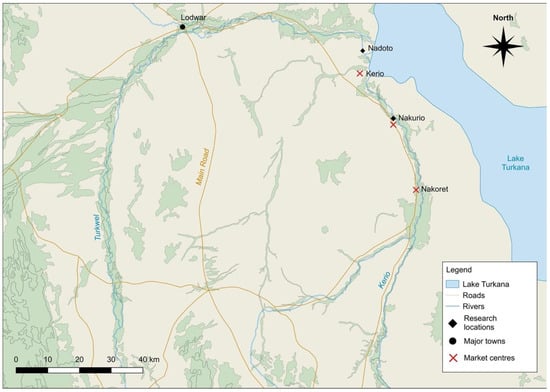

Figure 1.

Topographic map of northern Kenya showing the rough distribution of forest and rangeland. Turkana County is located in the area to the west of Lake Turkana.

In recent years, many of those pursuing pastoralist livelihoods in Turkana claim to have experienced a significant breakdown in previous rainfall patterns and general seasonality. In most cases, this is described as comprising a far less pronounced division between wet seasons (akiporo) and dry seasons (akamu). This disintegration has had a direct impact on the ‘boom and bust cycle’ characteristic of the regional economy (and livestock-based economies more generally) [4] (p. 37), which has historically involved rapid livestock reproduction during times of abundance (and by extension, copious quantities of milk) and the preparation and storage of various foods for consumption during dry months when fresh milk is unavailable. Experiences of similar ecological transformations have been documented across multiple pastoralist contexts not only in northern Kenya i.e., [9,10,11,12] but also sub-Saharan Africa more broadly, where the effects of climate change are impacting livestock-oriented livelihoods in a variety of complex ways [13,14,15,16,17]. In Turkana, as in many other contexts, these environmental changes have unravelled alongside transformations on a comparably radical scale within local infrastructures, an associated trend of economic growth and diversification and substantial population increase [18].

Taking all of this into account, questions arise as to what strategies and responses have been implemented over the recent past in the pursuit of prosperity and success, and how these articulate or clash with the Turkana pastoral economy’s historical dynamics. We address these questions by setting out ideas and cases developed over the course of long-term interdisciplinary research spanning roughly eight years. Our discussion is oriented around a series of key examples, drawn from interviews, group discussion sessions and participant observation undertaken in multiple locations across southern Turkana. Understanding how people have coped with radical economic and ecological transformation is, of course, important in its own right. However, our ambition in doing so is also to consider two more general interrelated themes: the future of Turkana pastoralism amidst the turbulence of the 21st century and the constitution of pastoralist knowledge and expertise in the region over long-term patterns of change.

In exploring these two themes, we aim to contribute to more general discussions of the dynamics of pastoral economies and institutions amidst uncertain ecological and environmental conditions. The examples we discuss in this article constitute a historically situated case study that in many ways echoes recent arguments for understanding uncertainty as an attribute that is productively engaged with by pastoralist societies, and that should be worked with (not against) by the development sector broadly conceptualised i.e., [19,20]. Considering the question of economic and ecological unpredictability over the course of long-term change, we also seek to contribute to an already rich scholarship of institutional and livelihood change in northern Kenya’s pastoralist societies, which we discuss in the following section. Drawing on evidence collected in the field, we argue that various recent ecological and economic uncertainties and a generally heightened resource variability have been incorporated into local livelihood strategies in a manner that does not necessarily divert drastically from previous historical patterns of periodic radical livelihood reconfiguration. Highlighting some of the instances in which Turkana pastoralism has continued to be reconditioned and reimagined in line with a changing horizon of possibilities, we suggest that ongoing transformations within livelihood practices, inter-livelihood relationships and corresponding patterns of mobility might best be understood as manifestations of a long-standing capacity for successfully managing the very uncertainty that characterises daily life.

2. Pastoralism and Uncertainty in Northern Kenya

In June 2020, while the globe grappled with the radical reshaping of everyday life that the coronavirus had come to demand, certain communities in Turkana were witnessing the rise of a very different celestial force. It was the tail end of an unusually abundant and unusually long rainy season. Herds of livestock were numerous, their coats shining. As the rains trailed off and the prospect of scarcity once more emerged, the instructions of a revered emuron (diviner/seer, plural ngimurok) began to proliferate. He told his listeners that if they wanted the rain to return, they would need to milk their camels with wooden elepit containers again (rather than the plastic jugs and other vessels that are becoming increasingly common). Moreover, when doing so, women would need to return once more to wearing the abwo and the adwel—animal hide aprons once ubiquitous but now far less frequently worn.

The individual dispensing this advice, we came to learn through numerous friends, acquaintances and interviewees, was claiming to have been possessed by a historical figure well known throughout southern Turkana, a man named Lokorijem. Over a hundred years ago, Lokorijem was a key counsellor to the war leader Ebei, who led Turkana’s fighting force in their protracted resistance to colonial subjugation [5,21,22,23]. He was, like other ngimurok, able to see beyond the bounds of the average human by means of his dreams. He could communicate with God, bringing down terrible curses on his enemies and wonderous blessings—such as rain—on his friends and followers. One evening, as we discussed Lokorijem’s apparent return in our camp in the hills behind Moru Sipo, Turkana South, specks of rain began to flicker down into our cups of tea. ‘This must be Lokorijem’s rain,’ someone remarked, predictably.

Despite our frivolity on that night, to us the rise of the newly returned Lokorijem, and his promise of rain, were far from superficial concerns. They got us thinking once again about the question of long-term ecological transformation, unpredictability in weather patterns and the manners in which communities in southern Turkana are dealing with these pressing concerns as compared with previous generations. We explained in our introduction that much has been written about ecological unpredictability in Kenya’s northern drylands. The fact that pastoralist societies there respond dynamically (rather than passively) to radical shifts in environmental conditions seems now to be unquestioned e.g., [4,24,25,26]. Where once the overriding presumption in academic investigations was of stasis, fragility and ecological equilibrium i.e., [27,28,29], most now agree that pastoralism in arid and semi-arid lands comprises as much uncertainty as the environmental conditions that encompass it. It is through this uncertainty—the fundamentally ‘nonequilibrial’ or ‘disequilibrial’ nature of the socio-ecological system in its entirety—that it has persisted for so long, weathering unpredictability by means of extreme variability in livelihood strategies and shifting resource dependencies. This regional view articulates closely with a more general understanding, evident in diverse case studies from across the social sciences, of contemporary pastoralist societies across Africa and the wider world as comprising fundamentally open and unfixed qualities i.e., [30,31,32,33,34,35].

In more recent years, discussions of pastoralism and ecological change in northern Kenya have moved on from the equilibrium/disequilibrium debate to be framed instead in relation to the term ‘resilience’. This is part of a trend in which East African pastoralism more generally has come to be conceptualised as resilient in the face of massive and far-reaching environmental degradation and various other socio-economic and political pressures e.g., [9,11,36,37,38]. The characterisation of resilience deployed in such instances (there are numerous different ways in which the term has come to be used since its initial emergence in the sphere of ecology) is often oriented around specific coping mechanisms, but has also come to be used in association with broader livelihoods and longstanding institutions as they operate in uncertain contexts, particularly in reports and publications produced by such organisations as the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) see also [39,40,41,42].

Presenting evidence from the Wodaabe in Niger, Krätli and Schareika [19] have critiqued the enduring propensity (even after the emergence of disequilibrium thinking) for conceptualising dryland pastoralism as merely a strategy for coping with sub-optimal ecological conditions. They have argued instead that it is best characterised as ‘an agricultural production system that exploits asymmetric distribution rather than stability and uniformity in the environment’ [19] (p. 615). In doing so, they have emphasised dryland pastoralism’s capacity to harness and exploit heterogeneous nutritional distribution—that is, that it functions as a system specifically geared toward production by means of uncertainty. The forms of knowledge and expertise they explore in their Wodaabe case study range from signs of livestock health palpable in the qualities of milk to the articulation of migration cycles with the spatially variable vegetative cycle of grass. Krätli et al. [43] also address some of the prominent methodological overhangs of now-outdated equilibrium-based understandings of pastoralism, which continue to obstruct dryland development (we return to these below). Elsewhere, Krätli [20] has further underlined the importance of understanding variability in herders’ environments as a valuable resource in itself, and the need for development policy to work with prevailing climatic uncertainty rather than attempting to control it or manage it by means of uniformity and stability.

More recently, this conceptual development beyond the equilibrium/disequilibrium debate has led to a proliferation of works exploring the relationship between resilience and uncertainty, particularly from the PASTRES research programme. Maru [44], for example, has examined the changing, conceptually fluid nature of mobility, critiquing the stubborn antinomy between ‘settled’ and ‘mobile’. Meanwhile, Scoones’ [45] survey of different approaches to, and ways of thinking about, uncertainty underlines the potential value that insight from pastoralist societies may bring to a wide array of different forms of uncertainty, impacting diverse sectors and socio-economic contexts. He suggests that one of the most important emerging questions is ‘What can we learn from alternative cultures of uncertainty that construct the world in different ways, through different histories, social imaginaries, traditions of thinking and everyday practices?’ [45] (p. 10). More recently, Scoones [46] has also underlined some of the problematic ways in which sustainability is conceptualised (particularly in relation to recent climate-change-related media), and the importance of appreciating inherent ecological instability where it exists and engaging seriously with how pastoralists ‘see, manage and value the world’ [46] (p. 116) rather than seeking new forms of reliability and uniformity.

Without seeking to lump diverse many-branched bodies of literature and research into one pile, it would seem reasonable to suggest that a common ground of interpretation is palpable. The prevailing picture is one of profound amorphousness and instability, engendering a tenacity that allows African pastoralist systems to endure and often prosper over the long-term in environmentally tough and unpredictable situations. It is significant, and yet rarely pointed out, that this impression bears a clear correlation to the long-term view that has arisen from archaeological research on the continent. Excavations and analyses spanning a wide array of time periods and locations attest to a heterogeneity in African pastoralist systems and forms of adaptation that seems to defy unequivocal classification entirely [47,48,49,50,51]. Recently, analyses of this rich historical record have underpinned investigations into land-cover change in East Africa over the longue durée, which have sought to elucidate the formative role that pastoralist settlements have played in shaping local eco-dynamics [52,53,54]. It has also been deployed to critically assess the perpetually looming fear of ‘overgrazing’ and to emphasise the general sustainability and importance (in terms of ecosystem biodiversity) of pastoralist systems of production [55].

To us, prevailing conceptualisations of how pastoralists negotiate uncertainty emphasise the value of discussion around two themes in particular. The first pertains to the very knowledge that facilitates various communities’ management of environmental change, recurring catastrophe and general unpredictability on diverse spatial and temporal scales. As we noted above, explorations of the complexities of pastoralist knowledge systems have recently underpinned critical contributions to the broader understanding of how pastoralism operates in variable and unpredictable environments i.e., [19]. We would suggest that there is great value in contributing further to such discussions, with new evidence and case studies, and particularly in seeking to examine patterns of knowledge production and implementation over the course of transformations that take place over the long term. It should not be overlooked that in some instances, despite the abovementioned extensive evidence and discussion to the contrary, pastoralist knowledge can still come across (perhaps accidentally) as inflexible and ageless e.g., [56,57]. Even if rarely portrayed as such in academic contexts today, in certain parts of the development sector—and certainly in numerous projects, initiatives and interventions implemented in Turkana over the past few decades—the institutions, mechanisms and knowledge reservoirs that are variously drawn on in the present continue to be construed as fixed within some kind of mysterious, undefined, permanent socio-cultural framework, rather than as skillsets that are continually generated, changed and re-learned by means of the very act of pursuing a livelihood amidst the shifting constraints and possibilities of the world see [58,59]. This is perhaps part and parcel of what Krätli et al. [43] (p. 3) describe as an outdated ‘methodological infrastructure of analytical tools and practices’ that is yet to fully catch up with the fast pace of theoretical change. In any case, we would suggest that there is scope for further academic scrutiny of the changing ways in which pastoralist knowledge is accumulated and deployed across multiple generations, and how such trajectories of intellectual change feed into and shape responses to various contemporary issues (cf. [45]).

The second theme is the question of boundaries and limitations; more specifically, the question of whether various recent forces of particularly heightened socio-economic and environmental change should be envisaged as constituting unsurpassable stumbling blocks for Turkana pastoralism and African pastoralism more generally. Various works focused on pastoralism in northern Kenya have examined long-term social change to draw out nuanced accounts of how communities have negotiated significant political, ecological and economic processes over the recent past. Lesorogol’s [60] Contesting the Commons, for example, tracks the emergence of new ambitions and shifting conceptualisations of prosperity amidst the transition from customary tenure to group ranching in Samburu see also [61]. Similarly, Pas’ [62] recent work on shifting patterns of mobility in Sesia, Samburu East, in relation to changing conflict dynamics, boundary formations and environmental changes, provides new insights into the dynamics of institutional change in the sphere of pasture management there, emphasising its propensity for continual reconfiguration in line with shifting constraints and possibilities. Meanwhile, Bollig’s explorations of the 20th-century historical transition within Pokot society have offered multiple examples of livelihood reshaping and reformation in line with changing local circumstances e.g., [63,64,65]. All of this work, and much more besides, has emphasised pastoralism’s enduring capacity for radical alteration on multiple temporal and spatial scales by means of a wide array of approaches to reckoning time and change, interpreting history, constructing identities and imagining the future. On one level, such work also perhaps defies any lingering suppositions about a limit to pastoralism’s ability to endure the turbulence of current or future times—the more detailed the historical account the harder it is to identify any kind of fixed or stable socio-economic form.

Taking heed of these various historical discussions of pastoralist economies and institutions, our recent research has nevertheless focused on the general theme of how best to interpret more recent radical, and probably long-lasting, ecological and socio-economic changes in Turkana. Whilst pastoralism might broadly be considered as resilient amidst diverse forms of turbulence, it is perhaps less clear whether the same characterisation can or should be applied to responses to permanently transformed landscapes, total political overhaul or the spread of wage labour and market-driven production, amongst other phenomena (cf. [66]).

The menace of disjuncture, rupture and the erosion of longstanding ways of life is by now long absent in most academic discussions, across multiple disciplines, but it arguably remains influential in much media coverage, and we would thus suggest that it continues to warrant critique. In seeking alternative explanations, ample scope for a less pessimistic outlook can be found in recent scholarly efforts to define pastoralism, which have tended to centre its ambiguity and flexibility. Watson et al. [9] (p. 702), for example, recently characterised pastoralists as people who ‘derive (or aspire to derive) some or all of their livelihoods from livestock’ (cf. [67]). Meanwhile, Krätli and Schareika [19] (p. 606) have suggested that ‘the term “pastoralism” represents a large spectrum of realities’. Far from reflecting a shortfall in existing research, this plasticity and vagueness—pastoralism is as much an aspiration, or a memory, as it is a particular set of activities—arguably indicates a level of sophistication in contemporary thought that bodes well for future research. We have already noted above that pastoralism on the whole, when considered across the full range of archaeological, historical and anthropological data available to us, is so diverse as to defy unitary classification. It would thus seem to make sense that contemporary definitions are kept loose enough to encompass a broad continuum of possibilities.

Indeed, our own past research in Turkana has examined the ways in which the regional economy has been transformed, reshaped and remade proactively by those participating in it throughout the last century and beyond on a continual basis, in relation to a broad and ever-changing variety of challenges and opportunities [5]. The idea that the economic or ecological conditions of pastoralism in Turkana would be capable of dictating an end to its endurance is at odds with this history. Much as the academy has done, communities there have consistently found new ways of imagining what pastoralism is, how it works and what it means for both the individual and society at large. We hasten to add that this is not to suggest that livelihoods in Turkana have been anything other than inextricably entangled in, and crafted by, their respective landscapes and ecological niches. Rather, that these conditions have not predetermined particular structures, relationships and arrangements within the grounded daily practices pursued amidst them.

In June 2020, our convictions about the two broad themes we engage with in this article—the limits of pastoralism amidst heightened processes of socio-economic and environmental change and the nature of pastoralist knowledge—were briefly confounded by Lokorijem’s appeals for people to return to wearing skins and milking their camels with elepit containers. By our own premature and ill-considered reading, the situation seemed like a caricature of the lackadaisical conceptualisations of ‘indigenous knowledge’ that still find their way into certain discussions of resilience across various development-related contexts. It was, at its core, a turn back to seemingly static traditions and culturally entrenched know-how in the face of an unpredictable natural phenomenon, was it not? What could the future hold for a socio-ecological system oriented around such conventions, if not rupture and disintegration?

While dry season took hold, news of Lokorijem’s exploits continued to blow over to our camp on a regular basis. As we considered the situation a little more carefully, we came to realise that we, to deploy an appropriately landscape- and ecology-oriented idiom, were not seeing the wood for the trees. Lokorijem’s rise, regardless of the inflexibility of his daily appeals and demands, was part of a much bigger picture in which the relationships between ngimurok, authority and rain have endured not through their implication in seemingly unchanging practices or beliefs but rather through their ability to gain traction and make sense within the very substance of a transforming set of ecological and material pressures (cf. [68,69]). Of course, the role of divinatory events, institutions and abilities as sites for both the creative re-imagining of long-standing social norms and the domestication of emerging material and political possibilities is well discussed in pastoralist contexts across Africa e.g., [70,71,72]. Anderson and Johnson’s [73] guest-edited special issue of Africa, on the subject of diviners, seers and prophets in eastern Africa, is a rich source of examples and ideas on these themes. Perhaps of particular significance to our case study though, is Hodgson’s [74] exploration of spirit possession across decades of religious and economic transformation in Tanzanian Maasai communities, in which she characterises orpeko (spirit possession) as a gendered mediation of modernity and an embodiment of its many contradictions. Orpeko, through its very ambiguity, has over the years at once served as the means for new collectives and forms of relation to emerge whilst at the same time re-enforcing broader, more deeply entrenched gender-related power dynamics see also [75,76].

In a comparable sense, the story of Lokorjem’s recent return, much like the story of Turkana pastoralism more broadly, is not one of people responding to the uncertainty of their circumstances by drawing on an immutable reservoir of inherited knowledge, but rather of people finding new ways to make sense of past experiences and pre-existing institutions and practices and redefining them in the process. The sense of continuity is not in deeply rooted traditions and underlying knowledge, but rather in a fluid, collaboratively shaped epistemological framework encompassing constantly transforming knowledge sets and socio-ecological engagements. It should perhaps also be pointed out that while we would suggest that the advice set out by Lokorijem in June 2020 might best be understood (particularly in the context of this article) as part and parcel of a broader institution finding expression in a changing arena of social action, its substance is far from arbitrary. The heightened tendency for plastic containers to retain and transmit disease, for example, is a clear illustration of the practical utility of opting to use wooden containers, which are routinely sterilised and fumigated with embers of edung—a type of caper bush (Boscia coriacea) with well recorded and diverse medicinal properties [77].

We return to Lokorijem’s story throughout the following two sections, as we draw on examples from our ongoing fieldwork to further explore the two themes outlined above. The chronological interpretation of these examples will be aided by Table 1, which is a timeline of regionally specific past events commonly deployed to structure historical narratives in Turkana in the contemporary world. This timeline, collated over several years of research, should not be conceptualised as all-encompassing; it grows and is further refined on a constant basis as our work continues. It reflects the historical experiences of a small cluster of communities across southern Turkana rather than the entire region, and many key years are no doubt omitted. We include it here to reflect both the format of our many historical discussions with research participants and to link with several references in the interview extracts we consider.

Table 1.

Table showing some key years in the recent history of communities in southern Turkana, roughly correlated with years in the Gregorian calendar. Where a date range is given, the Turkana year fell at some point within the range rather than spanning it entirely.

3. Relief Food and Sedentism

We set out in the introduction how many of our research participants have reported experiencing substantial changes in weather patterns over recent decades, describing a general trend of far less pronounced periods of precipitation. Alongside this significant change, the fairly recent discovery of oil reserves in the Lokichar Basin, southern Turkana, has only served to galvanise the sense of urgency and impending socio-economic revolution [78]. Enns and Bersaglio [79] (p. 160) have gone as far as outlining what they perceive to be ‘disjunctures in the livelihood desires and strategies of youth from pastoralist contexts’. It has now been almost a decade since Turkana’s oil discovery was first announced and the question of how the extraction of this resource will impact local livelihoods and economic dynamics has perhaps at last begun to move beyond initial aggrandisement and catastrophising (that is, if it is to be extracted at all). Nevertheless, the sense of far-reaching upheaval with which Turkana’s oil is connected, metaphorically if not substantively, is very real. For those participating in Turkana’s pastoral economy, the experience of increased climatic volatility over recent decades has coincided with that of the growth of settlements around nodal market centres (which we explore in further detail in the following section), the systematisation of relief food distribution, the expansion of the telecommunications network, an increase in opportunities for wage labour, business and education and a general closer connection to and integration with regional town centres. All of these factors are interwreathed to the extent that it does not make much analytical sense to consider them separately, certainly not when it comes to trying to understand the manner in which change has been pursued and made real within herding populations over the recent past.

The question nevertheless remains as to whether the lens of disjuncture, as self-evident as it may perhaps seem to many, is the only way in which to understand this process of change. In an immediate sense, a large proportion of the interviews we have conducted over the course of the last few years with herders from southern Turkana have indeed acquiesced with a view of the recent past as comprising radical discontinuity. For example, during an interview with a herder known as Epaya Rayo from Kayapat, Nakaalei, we were told that the vast majority of herders in the surrounding area (that is, a cluster of homesteads around Kayapat) had recently made substantial changes to their regimes of movement. Ecological dynamics had led most to shift from undertaking regular migrations with large mixed livestock herds (usually numbering in the hundreds) to a form of sedentism oriented around much smaller herds (usually numbering in the tens) and comprising variation only within grazing routes:

‘During Ekaru a Ariboken [‘The Year of the Solar Eclipse’, roughly 1974] I started to see serious changes, in fact people left this place and moved far away. By the time of Ekaru a Akalakal [‘The Year of White Sacks’, roughly 1992] it had got even worse. We had terrible hunger. If we had not been given relief food, we would have died […] Before the increase in uncertainty with rain, herds were generally much more numerous. An individual might move up to four times in a year seeking better grass. For a while, people started moving much more than this, because it was very dry, and grass was very difficult to come by. However, in the last twenty or thirty years, people have radically reduced the amount they move. There was no need to move as far because herd size was reduced so much. Food can be acquired at market centres nowadays. The distribution of relief food, though, had the most significant impact on us sticking to one place. Staying in a group, in one place, guarantees access to relief food during times of hardship’.(Interview with Epaya Rayo, 7 February 2021)

It is important to point out that the shift that Rayo describes here is by no means the only way in which herders in Turkana have dealt with environmental changes in the last few decades. On the contrary, there has been a wide range of responses deployed by different groups in different parts of the region including, for example, the splitting of large mixed herds into smaller ones, and their scattering into several different locations (a very longstanding strategy). Equally, largescale movement into neighbouring regions, such as Uganda, in search of pasture remains relatively common in western Turkana. The decisions made by the community at Kayapat represent one strategy among many in an extremely diverse mixture of responses. Needless to say, it seems difficult to imagine a shift from flexible mobility to a sedentary utilisation of relief food as anything other than a rupture. Yet, conceptualising this important adjustment within its historical context arguably uncovers grounds upon which to make just such an interpretation, that is, grounds upon which to understand it as a continuity.

A comparison might even be drawn to a similar process of sedentarisation that took place in the early 1980s, following a severe famine. During this time, drought led to the loss of ‘over 90% of cattle herds, nearly 80% of small stock flocks and 40% of camels’ [1] (p. 164). It was in response to this famine that various so-called ‘famine camps’ were set up across Turkana, as part of the Turkana Rehabilitation Project (TRP)—a collaboration between the Kenyan government and the European Economic Community (for detailed explanation and analysis see [1,4,5,8,80,81,82]). Significantly, a large proportion of those who took up the offer to settle in these famine camps only stayed long enough to replenish their herds and return to a flexible, semi-nomadic existence. In other words, the second of the TRP’s two objectives—the five-year ‘land rehabilitation’ plan, which involved encouraging herders to adopt agriculture on a permanent basis—was entirely unsuccessful (the first objective was providing relief for the famine on an emergency basis). Relief food, and the sedentism associated with it, were incorporated into daily life by herders who had lost stock only as part of a broader strategy that involved the utilisation of diverse and ever-changing resources in a context of equally complex socio-political, economic and environmental volatility. When the rains returned, and the horizon of possibilities once more shifted, it became clear that the most fruitful strategy (socially, economically and politically, that is) would be to return to the flexible maintenance of large herds of livestock (see [5]).

The shift away from regular migration described by Epaya Rayo may well prove to be more permanent than that experienced during the TRP. Nevertheless, we would argue that it is fundamentally similar. What we mean by this is that if Turkana pastoralism is best understood as a system specifically geared towards making the most of the uncertainty of its broader context, then a population settling in one location to adapt to new contextualising factors cannot be seen to represent any kind of systemic discontinuity or breakdown. It is a livelihood reconfiguration equally as dynamic and innovative as any other that has taken place in the past. Remaining in one location with smaller herds and exploiting a new resource—relief food—is an interpretation of pastoralism that simply works best for the situation at hand. Moreover, there is arguably no evidence to suggest that the longstanding flexibility that has engendered this very change will not endure for generations to come—no reason to believe that recent years represent any form of rigidification. Should the combination of opportunities and pressures that present themselves on a daily basis once more shift in any substantial way, it would seem reasonable to assume that a commensurate livelihood shift would also ensue. This may well be a more profound intimacy and integration with regional markets and town centres; however, it is not impossible that it would be an increase in herd sizes and an intensification of seasonal mobility.

Either way, perhaps the salient point is that debate is unlikely to find coherence if the literal mobility of herding populations is conceptually merged with the flexibility of the socio-economic and ecological relationships that allow pastoralist systems on the whole to embody the different uncertainties that contextualise them (and, by extension, endure by means of these uncertainties (cf. [44,83])). We return to this theme in the following section. Suffice to say at this stage that the binary seems, at least in relation to the question of African pastoralism in the popular imagination, to articulate with various other persistent binaries—rural/urban, traditional/modern, authenticity/loss and so on—that doggedly structure conceptualisations of social change in similar contexts. These all seem to be substantiated via a kind of metaphorical role played by the material and technological ramifications of globalisation (cf. [84,85,86,87]). In the same way that sedentism in the context of pastoralism seems to elicit an instinctive supposition of rupture, technologies such as mobile phones and other mass-produced commodities and consumables are seemingly impossible to imagine as anything other than representative of radical, unmitigated change.

This point of connection—the link between the theorisation of sedentism as a loss of past lifeways, and the broader imaginaries that structure thinking about social change in pastoralist contexts across Africa—became increasingly conspicuous to us as we learned more of Lokorijem’s return. Throughout June and July 2020, we documented many circulating stories of his ongoing contestations with other powerful diviners in the region. The fact that such competition for authority would take place was, in itself, no surprise. Turkana has a long history of similar power struggles between rival ngimurok stretching back to the mid-19th century when the leader known as Lokerio resolved a dispute with a rival emuron by, so the story goes, parting the waters of Lake Turkana in order for raiders to cross over and take cattle from communities on the other side [5,23,88]. Nevertheless, the particular methods deployed by the newly returned Lokorijem in 2020 did grab our attention and provoke questions—his leading approach to demonstrating his capabilities was via the medium of the mobile phone. This new technology (most of southern Turkana outside of major towns did not have mobile phone signal until quite recently) had become quite inseparably entangled with the performance of critical aspects of an extremely long-standing institution.

We were told of a meeting of elders at Nakaalei, for example, which had recently been interrupted by a phone call from Lokorijem. As the phone was passed around the gathering, he proceeded to tell attendees what specific objects they carried in the folds of their robes or the pockets of their shorts—for some, he even stated the exact amount of money they had brought with them. On other occasions, it was said that he listed the precise location of various personal possessions that attendees had left at home. Such displays left an unmistakable impression on those who witnessed or heard about them, the sense, palpable in our interactions, was that Lokorijem’s sight was boundless, his powers uncharted. Yet, to us, the most compelling aspect of these stories was the role the mobile phone had played.

This is not because we imagined the situation to comprise any sense of hybridity—it was not an example of an inert anterior form of interaction simply finding expression within a new arena for social action (cf. [89]). On the contrary, we knew from previous research that over the last century the role of ngimurok in Turkana has endured precisely by means of its continual radical reconfiguration amidst diverse socio-political, material, economic and ecological transformations emanating from processes such as colonialism, infrastructural growth and the spread of automatic weapons, among many others. The activities of ngimurok have been, by necessity, completely immersed in all of these influential processes. The use of mobile phone technology to redefine how supernatural capabilities are demonstrated and performed, as we witnessed in 2020, recalled in our minds, stories about colonial-era chiefs articulating their new authority by surrounding themselves with conclaves of ngimurok advisors in the 1920s–30s; it harkened back to the radically new ways in which ngimurok became involved in intergroup conflict during the spread of automatic weapons in the 1970s–80s. In other words, it illustrated the point that the institution of divinership, including attendant patterns of competition and contestation, has never been unequivocally delineated. It has always been in the process of becoming.

Our understanding of this nebulous durability in Lokorijem’s social position, and its continual re-emergence amidst superficial fractures (literally, to those who believe his claim), draws parallels with our broader questioning of what the limits of pastoralism in Turkana are, in the face of profound ecological change. In both instances, the challenge levelled is against the notion that certain all-encompassing boundaries (whether they be socio-cultural or socio-ecological) have been shattered somehow, by new forms of activity and interaction. In Lokorijem’s case, a situation involving seemingly new materials and technologies can be interpreted not as a rupture but as an articulation of a much longer, more complex history; one can identify a temporality in its performance that is not contingent on material duration (cf. [90,91,92]). In the case of Turkana pastoralism more generally, a situation such as that inhabited by the newly sedentary, relief-food oriented community at Kayapat can be understood as a manifestation of a longstanding habitude of change and opportunism central within lives and livelihoods across Turkana for many generations, regardless of the apparent disjuncture it might seem to represent on the surface.

Intriguingly, to Thomas Widlok [93] it is precisely by thinking in terms of situations (albeit in his case in relation to hunter-gatherer societies rather than pastoralist ones) that new theoretical potential might be unlocked beyond the eliminativist agenda to dispense with subsistence procurement categories altogether. He has argued that in order to jettison abiding problematic conceptions of hunting and gathering as an innate attribute (either personal or collective) characterising forms of interaction with particular locations, we might conceive of hunter-gatherer properties, which different situations can acquire. To illustrate this idea, he sets out an example from a conference in Windhoek—‘an urban setting devoid of anything that one would typically associate with hunting and gathering.’ [93] (p. 7), during which two San attendees manifested

‘A textbook version of Hai//om demand sharing, practiced dozens of times every day, a silent demand initially, a gesture, underlined with a remark which at the surface only requests information about the contents of my rucksack, or the state of tobacco in the world, if you will. The anticipation of an act of giving or provisioning initiated by the receiver but only after prompting the interlocutor to acknowledge one’s presence’[93] (p. 7).

Such thinking is clearly germane far beyond the specific theme of hunting and gathering in the 21st century. It may perhaps even allow us to unveil alternative, less lugubrious conclusions about the future of pastoralist systems amidst increasingly volatile conditions. We set out in Part 1 that, much like hunting and gathering, pastoralism has emerged and persisted amidst an innumerable diversity of environments across both time and space. In light of this point, it would seem reasonable to adopt Widlok’s perspective and insist that just as it would be inaccurate to label particular material conditions as somehow exemplary of pastoralist life, it would be inaccurate to view particular landscapes or environments as specifically pastoralist in nature. Nevertheless, in doing so—that is, in conceptualising pastoralist situations, emerging amidst diverse ecological, economic and political contexts—the question remains as to how the ‘properties’ that shape these situations might be constituted. In other words, it is not clear how we should make sense of the various practices, performances, relationships and activities that shape such situations. The obvious danger is falling back into an essentialist perspective of culturally entrenched knowledge, which passively underlies engagements with the contemporary world and makes them ‘pastoralist’. We discuss this issue in the following section.

4. Ecological Change and the Herding-Cultivating Relationship

In the previous section, we outlined how environmental changes experienced in Turkana over the past few years have taken place alongside a mixture of other, equally profound, processes of socio-economic transformation. So far, we have suggested that in making sense of this tidal wave of change in northern Kenya it is necessary to find alternatives to accounts, primarily in the popular media, that pessimistically predict social disintegration and loss. The example we have discussed—the opportunistic exploitation of relief food distribution—is a particularly ominous one, which emphasises the extent of food insecurity in the region today. We should point out that our aim in using this example is not to suggest that such contemporary issues are unworthy of the attention they are afforded, nor is it to set out cynical narratives of self-reliance and ingenuity in the face of extreme hardship caused by historical socio-economic marginalisation (cf. [94,95]). Our point has rather been that it is necessary, in analyses such as this one, to move beyond the language of crisis, not for the sake of ignoring contemporary issues but rather to ground them in a temporally richer perspective and uncover longer-term socio-economic dynamics that might inform the way we understand and address both present and future challenges. Such a shift in perspective is also important for the capacity it might grant to dispense with the obstinate melancholia that still tends to permeate perceptions of globalisation in Africa [84,85]. It is well known that one-dimensional, un-historically situated accounts of changes impacting remote, marginalised regions have played no small role in feeding into ‘development myth-making’ over the years [96] (p. 178) (see also [97,98]). Turkana is no stranger to the kind of catastrophic developmental failure that can ensue [8,99]. However, finding less restrictive ways of envisioning the future of pastoralism in Africa is also clearly something upon which the diverse and increasingly rich bodies of relevant literature insist, on their own terms. In other words, it is a necessary task even in a purely theoretical, unapplied sense. Perceptions of ongoing and future adaptations, as radical and tumultuous as these may be, must be made to articulate with the picture of pastoralism so far rendered by many years of cross-disciplinary research (cf. [30,34]).

The possibility that pastoralist institutions and relationships may be understood as phenomena capable of finding expression amidst infrastructural and ecological conditions radically dissimilar to those in which they have previously existed might clearly be a critical component of this opening up. As we noted in the previous section, the task of identifying patterns of continuity-in-change is contingent on a finer-grained understanding of the very epistemological frameworks that shape such patterns. That is, if we are to avoid falling back on perfunctory characterisations of ‘indigenous knowledge’, it is necessary to appreciate more carefully the particular ways in which knowledge is learned, accumulated and embodied in pastoralist contexts over long-term interactions with particular places and resources. In navigating this task, insight may of course be mined from corresponding ideas prominent in much of the literature that has emerged from the world of historical ecology e.g., [100,101,102,103,104,105]. We may also look back to practice theory for guidance, and ensuing views of history as ‘long-term patterns of activity’ [106,107,108,109] Or indeed, to an Ingoldian conceptualisation of livelihoods as unstable, perpetually unfinished indivisible totalities i.e., [58].

Either way, it was with this general ambition in mind that, between 2014 and 2017, we sought to document and analyse specific case studies in which histories of ecological engagement have shaped contemporary practices and forms of interaction. In doing so, our research led us to a series of communities located along Turkana’s two major rivers; the Kerio and the Turkwel (See Figure 2) [5]. While decidedly entangled with the broader herding sector, these riverside populations have also historically been involved in flood recession cultivation. Our interviews and discussion sessions with them unveiled a complex story in which they had clearly drawn on their familiarity with riverine resources to reconfigure and restate a relationship to the more specialised herding sector that had become untenable as a result of ecological deterioration.

Figure 2.

Map showing the lower courses of the Kerio and the Turkwel. Note, both rivers have numerous trading centres along them, this map shows only those centres on the Kerio that were regularly visited during the course of our research.

We were told how, in the deeper past, those engaged in cultivation along both rivers had provided grain to herders who were either family members (with family networks thus facilitating the equitable consumption of grain and livestock products) or non-relations who brought their livestock to the river during times of hardship to exchange for goatskins (ngichweei) full of sorghum. By means of this seasonal relationship, riverine cultivators had been performing a vitally significant role within the local economy, nutritionally supplementing diets that otherwise primarily consisted of meat and dairy. Emeri Lowasa, the head of a family engaged in cultivation along the Kerio for many generations, recalled her memories of this time to us in April 2015:

‘I was here when cultivators were trading sorghum to herders for animals […] before Ekaru a Atchaka Ekipul [‘The Year of the Lost Padlock’, c. 1965–1970]. During that time there were no kiosks, no markets, no roads. The first road was not like this one. There is a story of two local men. One built a kiosk in Nakurio and the other built his in Kerio and they began to do business, this is when the markets started […] This was when ngichweei [large goatskin bags] began to be replaced by sugar and cement sacks for storing grains, and instead of ngileui [smoothed goatskins] people began to use amkeka [palm mats] for threshing’.(Interview with Emeri Lowasa, 6 April 2015; Derbyshire 2020: 121)

In the latter decades of the 20th century, the seasonal reliability of flood recession cultivation along the Kerio began to break down (although it does still take place when possible). This breakdown was most probably the result of a mixture of factors, including increasingly erratic rainfall associated with climate change [20,110,111,112], increased irrigation activities further upstream in the Kerio Valley and the introduction of the invasive species Prosopis juliflora. In any case, as cultivation became increasingly untenable, or at least unreliable, as a result of this breakdown, populations in riverside settlements found new ways of engaging with and shaping the processes of infrastructural development taking place around them. They did this by deploying the very skills and experiences they had accumulated over the course of their lives by the river. For example, utilising palm, a resource unique to riverine forests throughout Turkana, they began producing mats to sell in burgeoning markets (the first mats produced in Turkana were made in the early 1980s). Similarly, cultivation plots, lying fallow for lack of an inundation, were used to burn charcoal, which in turn came to be sold in sacks to traders frequenting local market centres in lorries.

Perhaps most importantly though, the riverside communities harnessed their familiarity with the infrastructural and economic growth described by Lowasa to begin trading and exchanging grain from external agricultural zones to visiting herders (the seasonal movement of herders into riverside settlements during times of hardship was, and in many cases remains, a key response to scarcity). Where previously herders had come to acquire sorghum grown in cultivation plots, they now came to attain a wider variety of grains brought into Turkana via Lodwar (the regional capital) by many of the same people. The relationship between families engaged in cultivation and the broader herding sector thus came to be rearticulated by means of new infrastructural and commercial possibilities, in response to novel ecological constraints. A situation, to return to Widlok’s terminology, comprising a seemingly extreme disintegration of past practices (the degradation of seasonal cultivation and exchange) can be understood as one that has been equally crafted by the very experiential histories of these practices. Even the locations of newly solidifying market centres across southern Turkana (with associated business centres, connecting roads and settlements) attest to the historical significance of the relationship between those who orient their livelihoods around the river and those who do so around the plains. The vast majority of these centres are located at nodal points along the major rivers—places known for regular historical exchanges, near to meander scars where crops of sorghum can be raised following floods.

In January 2021, during more recent fieldwork, we once again picked up the threads of this story, seeking to understand how the changing cultivation-herding relationship in Turkana has been experienced by those more firmly rooted in the herding sector. During an interview that unravelled over the course of three days, we documented the experiences of Esuruon Lomosia, an elderly herder from the Ngisonyoka section. Lomosia’s perspective on general ecological change correlated closely with many others we had documented:

‘In the past, seasonality was more predictable. A year would contain a dry season and a wet season. Each year would have its wet months and its dry months, and it would go round and start again. The wet season—six months. The dry season—six months […] Now it is much drier throughout the year and the rain is much more sporadic during the rainy season. During rainy seasons in the past, milk was more abundant, and thick with fat and oil. Not like today’.(Interview with Esuruon Lomosia, 29 January 2021)

As our discussion progressed, we delved into the question of how herders had engaged with the range of new commodities and foodstuffs that became available with the establishment of commercial markets, the solidification of infrastructure surrounding them and the general advent of the monetary economy. We knew that in previous times, when seasons tended to be at least more clearly divided (if perhaps not quite as predictable on a yearly basis as Lomosia suggests, considering how often, he conceded, there have been serious droughts), herders had deployed a range of preparatory food-storage solutions, which allowed them to endure many months of dry weather. Most of these had relied on a level of abundance no longer commonly experienced in rainy months (they involved the storage of fat, meat, grain and, most prominently, milk). Responding to our questions, Lomosia emphasised, like many other interviewees had done, how engagements with riverside markets now take place on a year-round basis, and that this situation is starkly dissimilar to the rhythmical seasonal sorghum-livestock exchanges that had taken place in the past. Dry, harsh months are, today, not dealt with solely through the long-term storage of foods (at least amidst many of the communities in southern Turkana). This is not only because the wet season is rarely abundant enough to facilitate such preparations on a large enough scale, but also because livestock can be sold for cash whenever necessary, and a much wider range of commodities and foods can be purchased from market centres all year round.

Hearing about these changes in food storage and consumption reiterated in our minds the extent to which recent ecological shifts have been weathered via an equally radical reconfiguration of livelihood strategies. Not only have many herding groups come to remain sedentary for prolonged periods of time, as described by Epaya Rayo in the previous section, but the very dynamics of interdependence structuring human-livestock relations have, in many instances, been fundamentally reformed. This is not to suggest that herders no longer rely on their livestock for sustenance during the dry months, but rather that they now do so primarily via the mechanism of selling livestock for cash to purchase grains and other foods at the market. Once again, this clearly represents a substantial diversion from the past (commercial livestock markets have only emerged outside of Lodwar in the last 20 years or so and can now be found in a number of smaller settlements throughout southern Turkana), but nevertheless, a move that is arguably generally in tune with the long history of adaptive transformation that has shaped the pastoral economy in Turkana over the generations. The pertinent question, as far as this section is concerned, is surely whether and how this new intimacy with food products purchased at market centres has been given shape by past experiences of food preparation and storage in the herding sector.

In relation to this question, Lomosia’s description of his own experiences of various newly available food products is particularly enlightening. His consideration of powdered milk, a commodity popular across southern Turkana and sold in great quantities at all weekly markets, led him to explain that the reason for this product’s popularity today is its resemblance to a substance called edodo, which had previously been regularly produced locally (by drying milk in the sun), and which had been critical to survival during the dry months:

‘We would put milk in the etio [a gourd milk container] until it would become sour milk and then from the etio into the atubwa [a wooden four-cornered bowl] to dry in the sun, it becomes “edodo”—it is dried and it looks like white clay. From there we would store it in the echwee [goatskin bag] that way. In the dry season it can be mixed with water, and then eaten with whatever else. It tastes like sour milk; it doesn’t lose its taste. You can mix it with soup made from flour from doum palm nuts, and flour made from fruits of several other trees’.(Interview with Esuruon Lomosia, 29 January 2021)

Powdered milk, sold in tins, bags and plastic containers in centres that have expanded and solidified during the course of the last few decades of infrastructural growth, has clearly come to be experienced and apprehended by means of a widely remembered history of edodo production and consumption. It has imbibed a habitual familiarity extant across most herding families and, in the process of doing so, has accumulated a suite of affordances specifically entangled with the resources (i.e., flour made from the fruit of particular trees) and patterns of storage and consumption that structure domestic life. Its utility and wider social meaning in today’s world are, in a certain sense, impossible to disentangle from this familiarity—the relationships, skills and experiences in which it has come to be immersed. This is not to say that new powdered milk products have simply come to inhabit a food category (edodo) that is, in recent times, less common. On the contrary, new forms of long-lasting powdered milk have also come to be consumed in ways that were previously not common at all—the product has most certainly brought with it a range of new possibilities. The point is that powdered milk, like many other newly available commodities in the region, has neither exerted change on its own terms nor been subsumed into pre-existing rhythms passively. It has come to gain traction and make sense amidst historical experiences of similar substances, yet in doing so it has also figured into a longstanding habitude of change, whereby new activities, relationships and practices are forged via the unique possibilities it encompasses.

In this respect, we would suggest that Lomosia’s example of powdered milk is paradigmatic of how unpredictable, rapidly transforming conditions have been grappled with in a more general sense in Turkana over recent years. That is to say, it illuminates an orientation toward change, prevalent across numerous livelihoods in the region, which in many cases has engendered not only iterative amendments to daily practices but also the reshaping of entire economic relationships such as that historically connecting cultivation with herding. Underlying all of this is a distinctly human capacity for assimilating the unknown and the unpredictable by means of familiar habits, rhythms, concepts, relationships and vocabularies to determine pathways forward into prosperous personal and collective futures—a disposition for building an ordered world out of the very texture of chaos.

Over many generations of far-reaching transformation, ngimurok like the newly returned Lokorijem have acted out this archetypal propensity in a literal sense, epitomising it and giving it appreciable form in myths and stories by parting the waters of Lake Turkana, seeing across space and time and, perhaps most importantly, by bringing rain. It thus did not surprise us to hear an interpretation proffered by Lomosia on our third day of discussions that connected the recent breakdown in rainfall patterns with an increase in competition between rival ngimurok:

‘Maybe it is related to the increase in ngimurok. Further back in time, there were far fewer, and their work was all about rain. These days, there are many more, to the extent that they mess up each other’s work. If one begins to bring rain somewhere, another will ruin it—they compete with each other […] There are more ngimurok because Lodip [a prominent emuron in the mid-20th century] had so many children, and many of them became ngimurok, all competing with each other as ngimurok do. I can see a correlation’.(Interview with Esuruon Lomosia, 31 January 2021)

5. Conclusions

In surveying some examples of how ecological and economic shifts have been negotiated in northern Kenya over the last few decades, this article has sought to engage with two general questions. Firstly, how we might conceive of the future of a livelihood system that is as open-ended and unsettled as that which is characteristic of life in the Turkana region. Secondly, and parallel to this first question, how knowledge accumulated in Turkana by means of long-term engagements with particular places and resources is implicated in the reconfiguration of grounded daily practices and, much more broadly, the forms of interaction and interdependence that structure relationships between different livelihoods pursued within the regional pastoral economy.

On one level, the historical events and processes we have discussed in this article simply further support prevailing arguments that pastoralists in dryland contexts tend to succeed by embracing and exploiting ecological variability rather than working against it [19,20,33]. Situating some of the strategies that communities in Turkana have deployed in the face of recent environmental shifts within longer-term livelihood histories of similar adaptation perhaps makes it easier to apprehend how longstanding this economic orientation to uncertainty is and how fundamentally fluid and dynamic livelihoods in Turkana, on the whole, have remained over living memory. The argument that approaches to drylands development today, both in Kenya and more widely, must articulate with this orientation toward uncertainty (i.e., work with uncertainty, not seek to eliminate it) clearly makes a lot of sense in the context of Turkana’s recent history of managing unpredictability. As does Scoones’ [45] (p. iv) suggestion that embracing uncertainty in this manner means ‘a radically different approach to governance; one that rejects control-oriented, technocratic approaches in favour of more tentative, adaptive, helpful and caring responses.’

In the years ahead, it seems clear that far-reaching ecological and economic transformations will continue unravelling at pace, not only in northern Kenya but across numerous other African pastoralist contexts. Considering the breadth and depth of research that has explored pastoralist social and institutional change to date, some of which we have mentioned in this article, scholars from across multiple disciplines are perhaps better placed than ever to take up the challenge of understanding how these future transformations come to be enfolded within and co-opted by means of the habits, rhythms and skills that emanate from contemporary livelihoods and economic relationships. We would argue that, in the current context of heightened transition, it is particularly important that attention continues to be placed on what Bollig and Lesorogol [69] (p. 667) refer to as ‘the emergent character of institutions’ (in their case specifically in relation to the theme of the reassertion of the commons across diverse circumstances in the 21st century). In our view, doing so means grappling with the question of how various forms of knowledge are deployed amidst contemporary transitional phenomena not as unchanging guiding principles but as patterns of thought and action that come to be intimately and irrevocably entangled with the transformative processes themselves.

The examples from Turkana that we have considered in this article suggest that understanding how the unpredictable circumstances of the future come to be domesticated will require us to pay attention to how prevailing institutions and abilities are reimagined, not simply resurrected and applied to new challenges straightforwardly. Of particular value to this task are works that have examined longstanding pastoralist practices and relationships not as fixed elements underlying a flexible set of responses, but rather as things that are themselves perpetually under construction—always open to redefinition in the face of a changing world (e.g., [34,60,61,62]). Ultimately, this article has not sought to repudiate the very existence of radical transformation in lives and livelihoods—to argue that there is only the perpetual reconstitution of basic, immutable principles and components—but rather to contribute to the ongoing work of contextualising such transformations, in an analytical sense, within local histories and epistemologies.

These inferences conjure in our minds a final recent fieldwork experience—a closing chapter, if you will, in the vignette to which we have returned throughout this article. Towards the end of a recent stretch of research, we happened to pass through the area in which the original Lokorijem was said to have been buried. One of our passengers, who had heard us discussing the diviner’s apparent return, told us he could show us where the burial site was located. We duly stopped the car and went out in search of the grave. As we drew close, a sense of amazement reverberated through our small group, this was perhaps also laced with a modicum of fear, taking into account Lokorijem’s reputed powers. Our wonder, and the subject of our subsequent discussion throughout the rest of our journey that day, was related to the fact that the grave marker consisted entirely of branches, twigs and brush piled up into a mound. This practice—covering burial places with brush as a sign of respect, or ‘putting shade on them’—is common throughout Turkana, but we found it particularly remarkable to see a mound that had been maintained for so many years. The original Lokorijem, after all, is said to have died as far back as the middle of the 20th century.

The grave was both longstanding and entirely constituted by recent material and action—a felicitous analogy indeed, encapsulating some of our fundamental thoughts about how pastoralism in Turkana has endured over the years. Like the ship of Theseus, the grave’s permanence was facilitated not by core stability or strength (in the sense of being robust), but rather by constant, iterative acts of remaking. Its continuity was not the work of a single person—a single set of memories—but of many disparate people and generations working together, very few of them, these days, with any direct recollections of the diviner’s life. The very act of remaking the grave was also an act of remaking the man himself, in collective memory; a process of enshrining his deeds in contemporary knowledge, celebrating them in circulating stories and perhaps even inventing new stories, cooperatively. Contemplating that unassuming yet nevertheless enigmatic burial marker, it is somewhat unsurprising that Lokorijem returned in 2020. He had clearly always been here, waiting beneath the surface in speculation and conversation, looking to find expression at the right moment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.F.D., J.E.N. and L.L.; methodology, S.F.D.; fieldwork, S.F.D., J.E.N. and L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F.D.; writing—review and editing, S.F.D., J.E.N. and G.A.; funding acquisition, S.F.D. and G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a post-PhD grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation (Gr. 9943) and an Early Career Grant from the National Geographic Society (EC-58154R-19). We would also like to acknowledge support in the form of a large grant (EMKP2019LG02) from the Endangered Material Knowledge Programme, which, although not directly behind the research undertaken for this article, has provided us with extensive time in the field, greatly enriching our understanding of various key themes.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography, University of Oxford, UK (SAME_C1A_19_012, 07/03/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the British Institute in Eastern Africa and the Turkana Basin Institute for administrative and technical support. We would also like to thank St John’s College, University of Oxford. We are very grateful to the editors of this special issue for the invitation to contribute. We are also grateful to two anonymous reviewers who have greatly improved our discussion of evidence from Turkana through their reviews, and who have enriched our understanding of relevant research and theory. Thanks to Loura, Nakiru and Lorot Ekaale for hosting our research camp in Moru Sipo and the Lowasa family of Nakurio for their longstanding support of our work. Our thanks also to Chief Vincent Kamais, MCA for Kerio Delta Ward Peter Eregae Ikaru, Ass. Chief of Nakurio sub-location Jonathan Epakan, Longoria Moses, Petro Echulukum Ima and Petro Apetet Maria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hogg, R. Destitution and development: The Turkana of north-west Kenya. Disasters 1982, 6, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, R. Development in Kenya: Drought, desertification and food scarcity. Afr. Aff. 1987, 86, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Galvin, K.; McCabe, T.; Swift, D. Pastoralism and Drought in Turkana District, Kenya. Final Report to the Norwegian Agency for International Development; NORAD: Oslo, Norway, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, T. Cattle Bring Us to Our Enemies: Turkana Ecology, Politics, and Raiding in a Disequilibrium System; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire, S. Remembering Turkana: Material Histories and Contemporary Livelihoods in North-Western Kenya, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi, E.; Swallow, B. Invasion of Prosopis Juliflora and Local Livelihoods: Case Study from the Lake Baringo Area of Kenya; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Choge, S.; Pasiecznik, N.; Harvey, M.; Wright, J.; Awan, S.; Harris, P. Prosopis pods as human food, with special reference to Kenya. Water SA 2007, 33, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, S. Trade, development and destitution: A material culture history of fishing on the western shore of Lake Turkana, northern Kenya. Afr. Stud. 2019, 78, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.; Kochore, H.; Dabasso, B. Camels and climate resilience: Adaptation in northern Kenya. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 44, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabasso, B.H.; Okomoli, M.O. Changing pattern of local rainfall: Analysis of a 50-year record in central Marsabit, northern Kenya. Weather 2015, 70, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Opiyo, F.; Wasonga, O.; Nyangito, M.; Schilling, J.; Munang, R. Drought adaptation and coping strategies among the Turkana pastoralists of northern Kenya. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2015, 6, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, G. The Science of Climate Change in Africa: IMPACTS and Adaptation; Discussion Paper 1; Grantham Institute for Climate Change, Imperial College: Grantham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ndiritu, S.W. Beef value change analysis and climate change adaptation and investment options in the semi-arid lands of northern Kenya. J. Arid Environ. 2020, 181, 104216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabine, E.; Simonet, C. Value Chain Analysis for Resilience in Drylands (VC-ARID): Identification of Adaptation Options in Key Sectors; VC-ARID Step 1 Synthesis Report; Oversees Development Institute: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ericksen, P.; Leeuw, J.; Thornton, P.; Said, M.; Herrero, M.; Notenbaert, A. Climate change in sub-Saharan Africa: What consequences for pastoralism. In Pastoralism and Development in Africa: Dynamic Change at the Margins, 1st ed.; Catley, A., Lind, J., Scoones, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Assan, N. Possible impact and adaptation to climate change in livestock production in Southern Africa. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2014, 8, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Proceedings of the Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS). 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census, Volume 1: Population by County and Sub-County; KNBS: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019.

- Krätli, S.; Schareika, N. Living off uncertainty: The intelligent animal production of dryland pastoralists. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2010, 22, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krätli, S. Valuing Variability: New Perspectives on Climate Resilient Drylands Development; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lamphear, J. Aspects of Turkana leadership during the era of primary resistance. J. Afr. Hist. 1976, 17, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamphear, J. The people of the grey bull: The origin and expansion of the Turkana. J. Afr. Hist. 1988, 29, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lamphear, J. The Scattering Time: Turkana Responses to Colonial Rule; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J.; Swift, D. Stability of African pastoral ecosystems: Alternate paradigms and implications for development. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 1988, 41, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westoby, M.; Walker, B.; Noy-Meir, I. Opportunistic management of rangelands not at equilibrium. J. Range Manag. 1989, 42, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, R.; Scoones, I.; Kerven, C. (Eds.) Range Ecology at Disequilibrium: New Models of Natural Variability and Pastoral Adaptation in Africa Savannahs; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. The biology of pastoral man as a factor in conservation. Biol. Conserv. 1971, 3, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprey, H. Pastoralism yesterday and today: The overgrazing problem. In Ecosystems of the World, Vol. 13, Tropical Savannahs, 1st ed.; Bourliere, F., Ed.; Elsevier Scientific: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983; pp. 644–666. [Google Scholar]

- Galaty, J.; Bonte, P. (Eds.) Herders, Warriors, and Traders: Pastoralism in Africa; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bollig, M. Power and trade in precolonial and early colonial northern Kaokoland. In Namibia under South African Rule: Mobility and Containment, 1915–1946; Hayes, P., Silvester, J., Wallace, M., Hartmann, W., Eds.; James Currey: London, UK, 1998; pp. 175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Bollig, M. The colonial encapsulation of the north-western Namibian pastoral economy. Africa 1998, 68, 506–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catley, A.; Lind, J.; Scoones, I. (Eds.) Pastoralism and Development in Africa: Dynamic Change at the Margins; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Galaty, J. The indigenisation of pastoral modernity: Territoriality, mobility and poverty in Dryland Africa. In Pastoralism in Africa: Past Present and Future; Bollig, M., Schnegg, M., Wotzka, H., Eds.; Berghahn: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 473–510. [Google Scholar]

- Meerpohl, M. Pastoralism and trans-Saharan trade: The transformation of a historical trade route between eastern Chad and Libya. In Pastoralism in Africa: Past Present and Future; Bollig, M., Schnegg, M., Wotzka, H., Eds.; Berghahn: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 412–439. [Google Scholar]

- Fratkin, E. Stability and resilience in East African pastoralism: The Rendille and the Ariaal of northern Kenya. Hum. Ecol. 1986, 14, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Berkes, F. Applying resilience thinking to questions of policy for pastoralist systems: Lessons from the Gabra of northern Kenya. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]