1. Introduction

Landscape studies and tourism studies are two central fields of investigation defining and understanding contemporary places and mobilities. Over the last two decades, the awareness of landscape as an integrating, holistic concept has increased [

1,

2,

3]. In the perspective of sustainable development, the European Landscape Convention [

4] has strongly contributed in underlying the complexity of landscape as a concept, focusing on economic and ecological components and values in landscape as well as cultural and social ones. Landscapes are increasingly understood as a common resource, constantly changing and in need of continuous assessments on protection, management, and planning [

5,

6]. The same attention has been parallelly dedicated to the tourism phenomenon [

7,

8,

9,

10], assessed both as a relevant territorial development driver [

11,

12] and a potential negative transformative engine [

13].

The connection between the two themes is often taken for granted both in theoretical investigations and common discourses. It is precisely for this reason that there is a need to take a closer look at this complex relationship.

On a theoretical level, the fact that tourism studies are fed by multiple disciplines mostly related to social sciences and management [

14], and that the concept of landscape is analyzed in landscape studies through multidisciplinary and continually evolving approaches [

2] has mainly returned a fragmentation of contributions from which the correlation emerges. The need to place the nexus at the center of a structured, integrated, multidisciplinary reflection has been stressed several times from different scholars [

15,

16,

17]. Nevertheless, the nexus has been mostly addressed by two research perspectives only apparently in dialogue. On the one hand, from a tourism-centric position, scholars have raised issues of both valuing and impacting landscape [

18,

19,

20]. Tourism contributions, however, have not always addressed the complexity of the landscape as a concept. On the other hand, a landscape-centric viewpoint has focused mainly on landscape use and preservation with sustainable purposes [

21,

22] and, while absorbing the diatribe between “physical” and “social” scholars, this second approach has not always addressed the complexity of tourism and the multiple scalarity of its dynamics. The lack of dialogue between the two approaches has also generated consequences at the practical level.

The voices of some authors can be highlighted for their efforts in linking the two sectorial issues in a comprehensive way [

15,

17,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Although these reflections are related to different periods, disciplines, and styles, they debated the “landscape–tourism” relationship considering the physical aspect as one among multiple dimensions to be considered. Moreover, all these scholars attempted to address the issue in an innovative way moving towards multidisciplinary perspectives. In 2000, the book

Leisure and Tourism Landscapes: Social and Cultural Geographies [

23] introduced a change in the epistemological perspective, attributing a primary role to socio-cultural reflections on the nexus. In 2002, Terkenli asked for tourist–landscape theory and analysis to begin the exploration of a possible “newly-emerging cultural economy of space” [

24] (p. 228). From a distinct cultural geographic perspective, in 2007, Minca wondered, “What does the tourist landscape become when it is performed, put into practice?” [

25], (p. 440). Finally, in 2015, Stoffelen and Vanneste proposed to re-interpret the geo-tourism approach as a comprehensive way to focus on “landscape–tourism” interactions [

17].

Confirming the evident need for “an adequate organizational framework of analysis” [

10] (p. 291) of this complex interrelation, the present research started from the limited number of qualitative and quantitative bibliographic analyses on the nexus to further contribute to this research stream. In particular, results were taken from recent content [

27] and bibliometric analyses [

28] systematizing the state-of-the-art knowledge on the relationship between the two themes and defining a first theoretical background. While the rising interest in the theme has been evident from a variety of publications, it is worth examining how scholarly interest has evolved in using and selecting specific definitional terms. The conceptualization on the specific expression “tourist landscape” [

27,

29,

30] provides a comprehensive definitional framework and guides the present research in further conceptual efforts to operationalize defining aspects.

The most recent efforts in structuring definitions agree on “tourist landscape” being “the most appropriate and widely used medium of referring to landscapes, organized or transformed mainly through and for purposes of tourism development” [

29] (p. 150). According to Skowronek et al. [

27] “tourist landscape” is “a significant type of landscape, functionally related to tourists and tourism activity. It is an integrated and complementary whole meeting the needs of tourists and tourism through its operationalizing of natural and cultural elements. A tourist landscape is characterized by the dominant presence of tourists, tourist attractions and tourist facilities. It is characterized by subjective evaluation and a confrontation by tourists, in connection with their perceptions and expectations, which affect its continuous transformation” [

27] (p. 81). This conceptualization is embraced in Terkenli et al. [

30], where the definition of “tourist landscape” has been proposed to link together the three constituent elements defined in Skowronek et al. [

27] “whereby tourist attractions (real, imaginary or other) form the basis of all/any tourist interest, and which, when appropriately developed (infrastructure, services etc.), variably attract tourist interest” [

30] (pp. 82–83).

Positioning in this specific research area, the first research question addresses the “landscape–tourism” nexus through its definitional aspects, contextualizing and associating them with the main research tendencies. The second research question addresses the potentiality to further define and describe “tourist landscape”, identifying a tourist dimension of landscape. Finally, the third research question verifies the chance for structured definitional aspects framing the nexus to positively inform both theory and practice. The aim of the present investigation is, thus, to deepen the critical reflection on the different definitions of the “landscape–tourism” nexus starting from the definition of “tourist landscape”. Emergent topics, key issues, and themes are interpreted to advance with the conceptualization of this specific definition.

Considering the often-neglected complexity of the “landscape–tourism” relationship, (re)starting from the definitory level can add a theoretical piece to feed balanced strategies addressing local resource maintenance, social needs, and economic goals in an integrated way.

Following

Section 1, the implemented methodological design is presented. Subsequently, the paper provides a synthesis of the main findings for each research step followed by a descriptive analysis. From there, the discussion suggests opportunities deriving from the proposed definition of “tourist landscape” for new conceptual frames and practical issues. Conclusions provide a research agenda by underlying research gaps and possible directions for future investigations.

2. Materials and Methods

There is a great variety of publications that—knowingly or, more often, unknowingly, and directly or, more often, indirectly—addresses the “landscape–tourism” relationship using variable definitional expressions [

6,

8,

15,

17,

23,

25,

27]. From a methodological point of view, a systematic review of this literature was developed, focusing in particular on a range of frequent definitions regarding the interrelation.

To address the most important research topics and themes concerning the theme, three different methodological phases have been implemented (

Table 1).

Stage I: Collecting Literature Data

From a first general analysis of scholarly contributions about the nexus and conceptualizations of “tourist landscape”, other expressions emerged as recurrent. In particular, four specific key filters were selected: “tourist* landscape*”, “tourism landscape*”, “touristscape*”, and “tourismscape*”.

A systematic online search was then conducted using the Web of Science database using the selected definitions in the Title and Abstract fields. The WOS gives access to multiple databases referencing cross-disciplinary research thus allowing for in-depth exploration of specialized sub-fields per scientific discipline. The query of WOS returned a total of 238 publications published from 1985 to 2020 of which 66% were scientific articles, 22% conference proceedings, 10% review articles, and 2% books.

Among the different bibliometric fields provided by the WOS, chronological details, groups by research domain and source titles were examined to understand the features of the emerging corpus.

Stage II: Carrying Out Bibliometric Analysis on the Selected Data Corpus

In order to review systematic literature quantitatively, a bibliometric analysis based on term co-occurrence was implemented through VOSviewer 1.6.16. The software has been developed by Van Eck Nees Jan and Waltman Ludo from the Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS) of Leiden University in the Netherlands [

31]. VOSviewer was applied to the WOS selected database. In linguistics, co-occurrence is an above-chance frequency of occurrence of two terms from a text corpus alongside each other in a certain order. Co-occurrence in this linguistic sense can be interpreted as an indicator of semantic proximity.

The software identifies term co-occurrence in titles and abstracts using natural language processing algorithms. The original WOS data source with bibliographic information was extracted in .txt format and used in VOSviewer software. A binary counting method was used to consider only the presence or the absence of selected filters in a document. This software requires a threshold representing the minimum number of occurrences. The threshold was set at 8 for terms analysis. For each term that satisfied the selected threshold, a relevance score was calculated to exclude irrelevant terms giving very few information. Based on this score, 112 out of 5542 relevant terms were selected. The number of terms were calculated with the VOSviewer software using the normalization method of associations strength and a full counting algorithm. The default choice was to select 60% of the most relevant terms with a result of 67 relevant terms, further reduced, for display reasons, to a number of 60 mapped and clustered items.

A bibliometric map supports to improve the knowledge of the field and “makes all kinds of suggestions” confirming or contradicting our own idea on the state of this field [

32] (p. 249). With the aim to further verify first personal assumptions deriving from VOSviewer clustered items and emerging research topics, a second methodological approach was adopted based on a qualitative content analysis.

Stage III: Assessing Content Analysis on the Selected Publications

With the aim to ground previous inferences and to identify research issues and themes of the field, a content analysis was implemented on the WOS selected publications. In particular, the ATLAS.ti Software developed by ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH in Berlin, Germany was used. The software develops a hierarchy of conceptual group-codes, related codes, and quotations [

33] from a given corpus, allowing for the inductive categorization of texts in networked conceptual nodes.

Based on the VOSviewer clusters and related items obtained with the previous bibliometric analysis, a content categorization process was implemented through a top-down coding process. Group-codes corresponding to the defined research topics have been used from the beginning of the coding process. In addition, each group-code has been associated with the codes corresponding to the most significant items of clustering groups. The network view returned by ATLAS.ti software shows the relationships between codes and quotations in hierarchical form.

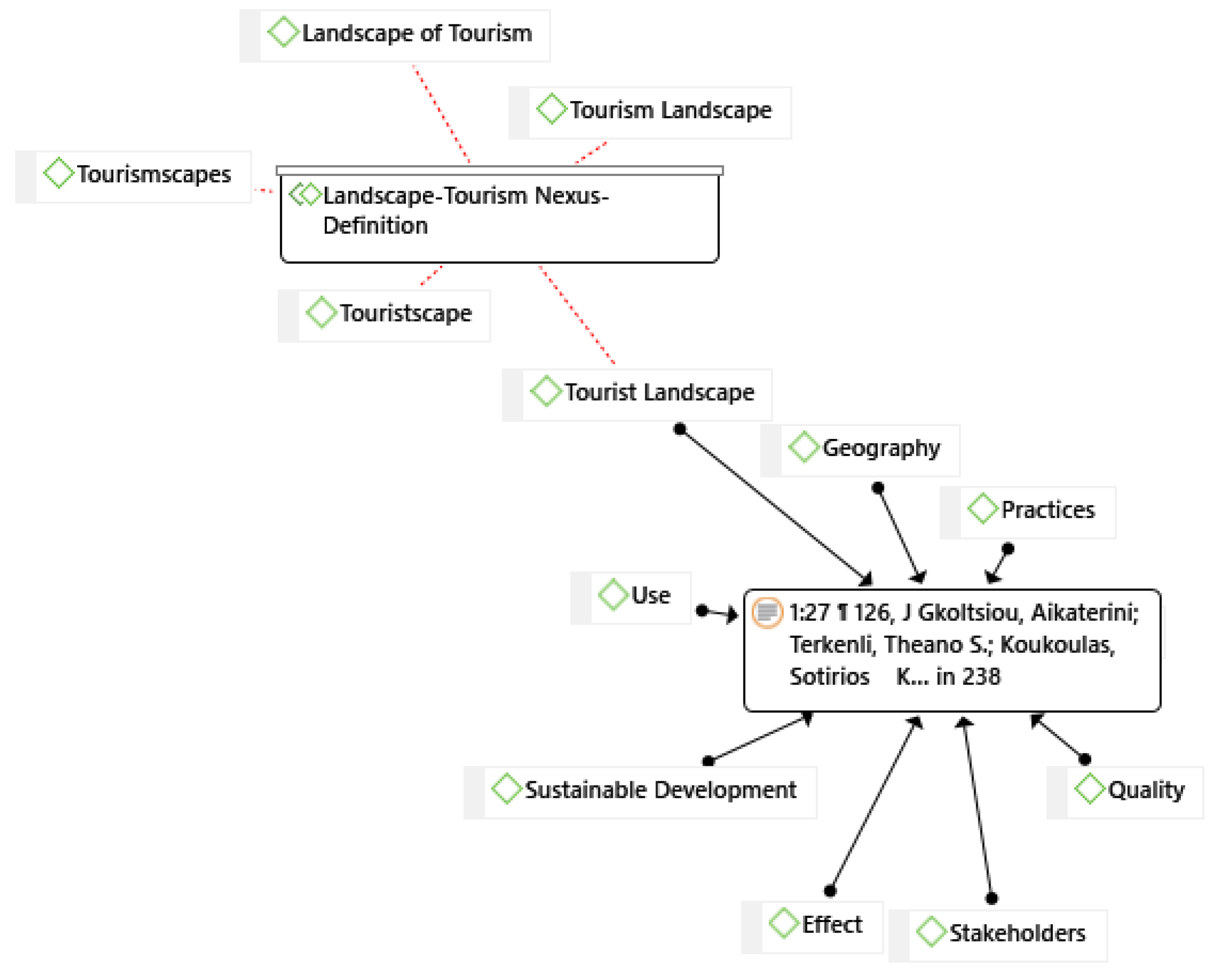

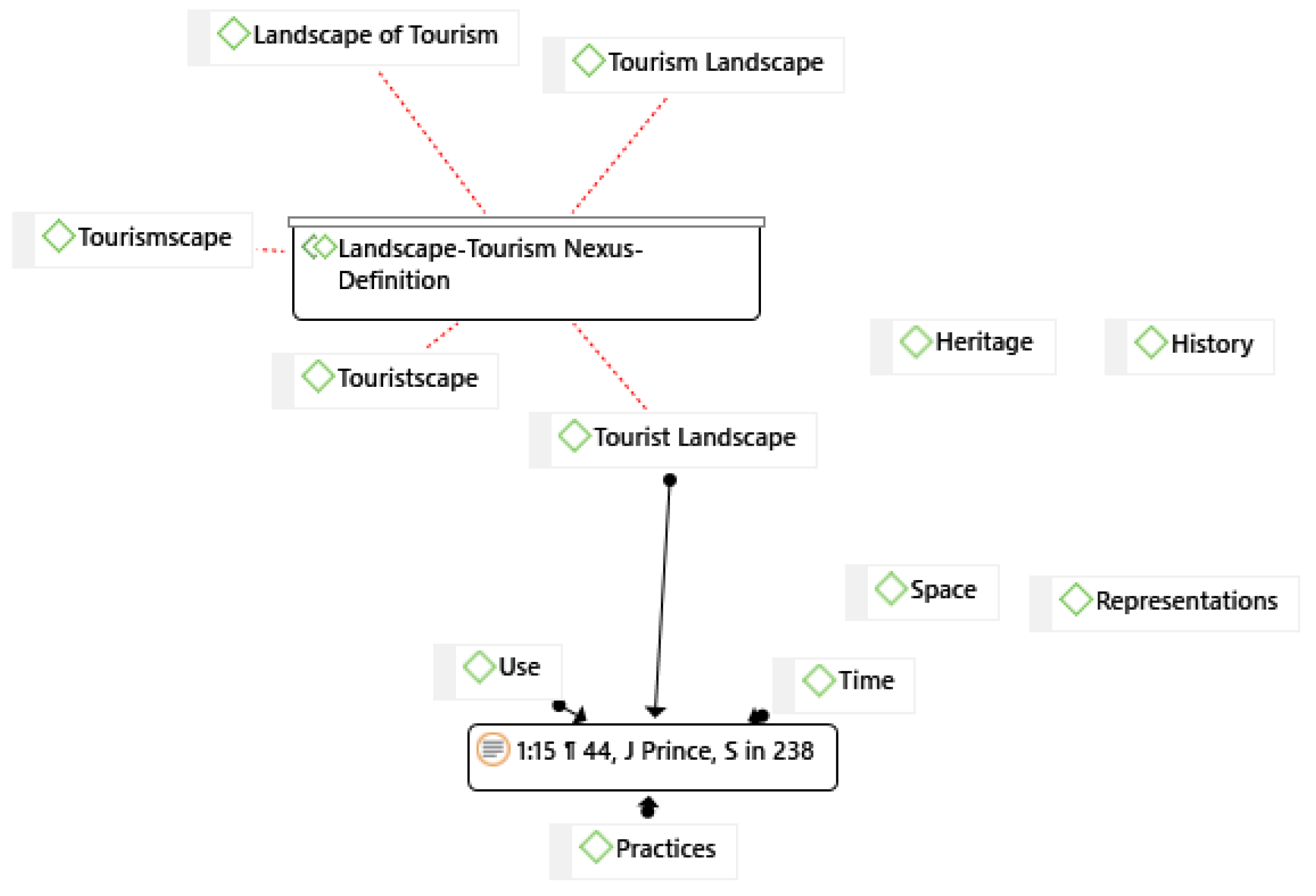

Later, a second network of codes was built using the selected definitions related to the nexus, i.e., “tourist landscape”, “tourism landscape”, “tourismscape”, and “touristscape”. Synthetic overviews have been provided to underline the specific definition positioning in relation to each group-code and code.

By integrating first quantitative outcomes, this qualitative approach favored not only the evidence of first assumptions but also the interpretation of the emerging network of key nodes as the main research issues and themes.

3. Results

3.1. Corpus Description

Web of Science allows for describing the corpus data through bibliographic fields, providing insights into research areas, journal distribution, and evolutionary information. With regard to research areas, it emerges that WOS has assigned the 238 documents to the followings research fields. One third of publications are included in the broad research category named “Hospitality, Leisure, Sport, Tourism” (32%); 21% represents, together, Environmental Studies and Environmental Sciences; 16.7% are under “Geography”; Social Sciences Interdisciplinary and Sociology areas account for the 12.8% of the corpus; Economics and Management accounts for 10.8%. Percentages under 5% represent documents broadly distributed among a variety of other specific fields (

Figure 1). Although the intrinsic difficulty to systematically conceive publications on interdisciplinary themes into specific research areas, the WOS categorization helps in inductively starting to define prevalent research topics.

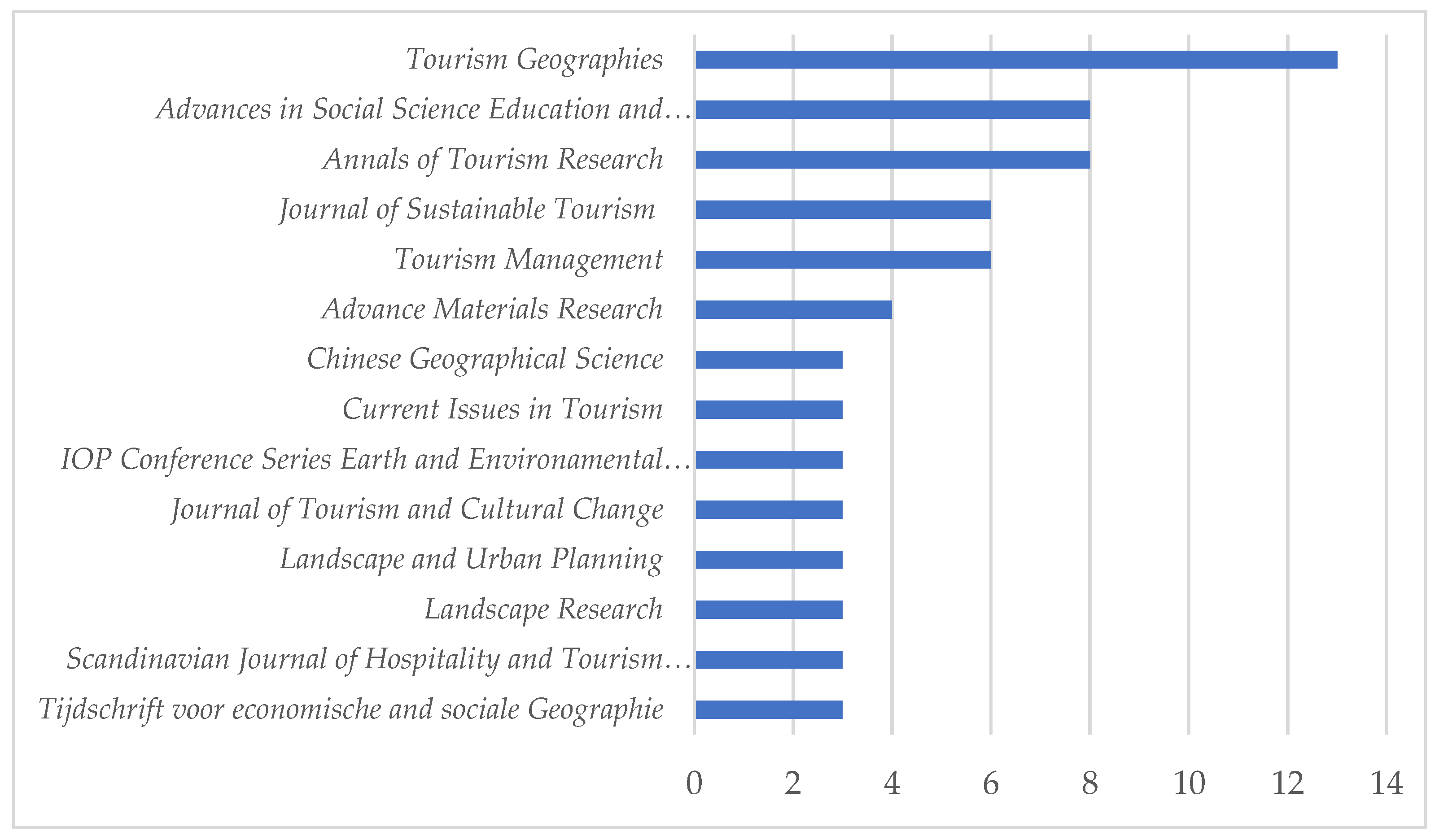

The distribution of documents in relation to journal titles confirms the previous results. There is, indeed, a prevalence of contributions deriving from tourism studies rather than landscape studies. The journals

Tourism Geographies, Annals of Tourism Research and

Tourism Management, among the most eminent journals in tourism studies, present the greatest number of contributions, while journals hosting reflections on specific landscape issues (

Landscape Research, Landscape and Urban Planning) have a lesser weight (

Figure 2).

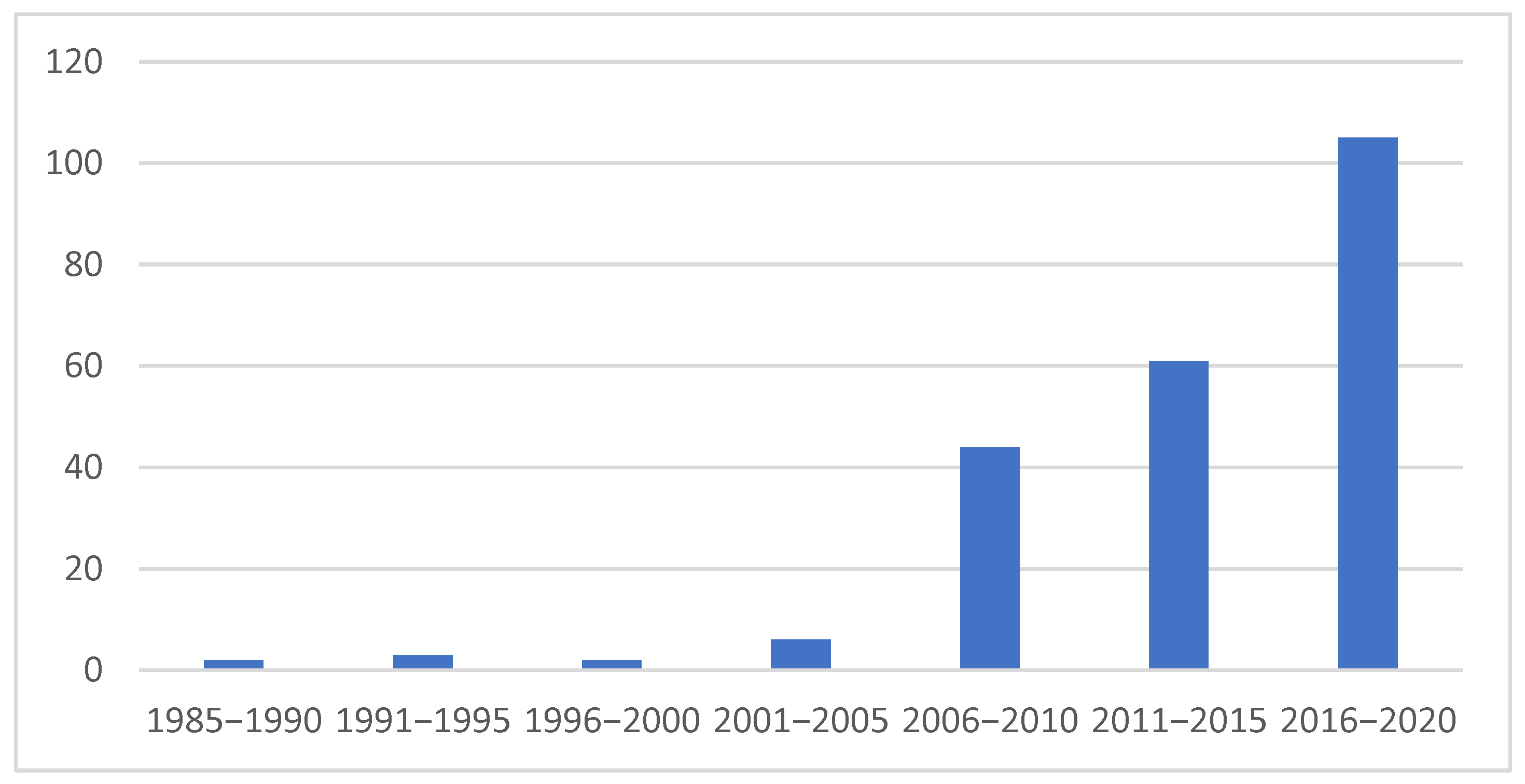

Regarding the evolutionary aspect (

Figure 3), it emerged that selected terms defining the “landscape–tourism” nexus started to appear in titles and abstracts from the mid-1980s with a publication in the

Annals of Tourism Research using the expression “tourism landscape” to present a comparative analysis about the changing scenery perceptions and evaluations by tourists and operators concerning Canadian Mountains and the European Alps [

34]. Presence and variety of definitions increased progressively around the year 2000 in coincidence with the publication of important theoretical reflections. The volume

Leisure and Tourism Landscapes: Social and Cultural Geographies [

23] was one of the most influential contributions stimulating an increasingly widespread use of the expression “tourism landscape” in subsequent studies [

35].

The year 2007 was another important year in which publications addressed the “landscape–tourism” relationship using specific definitional terms. The contribution

The tourist landscape paradox [

25] is theoretically relevant and using “tourist landscape” in the title has been able to influence the proliferation of the expression in many other contributions on the topic. From 2010–2011 began a boost that still continues to this today. As shown in

Figure 3, almost half of the publications analyzed in this survey were published between 2016 and 2020. One reason for this recent increase could be the expansion and complexification of the tourism phenomenon at the international level, and its transformative role in territorial areas that were previously unaffected by its effects. In the latter period, a few studies in the form of content and bibliometric reviews have also been established and definitional aspects have become a relevant key issue. The most recent literature overviews have assessed “tourist landscape” as the most appropriate definition of the nexus and, over the last two years, most publications, also from social sciences, have adopted this definition. Finally, in order to provide a comprehensive overview, the present investigation has sought the expressions “tourismscape” and “touristscape” as well. Although their use is not frequent, they are characterizing important theoretical reflections in specific research areas. First appearing in 2007, “tourismscape” has been defining the relationship in actor–network theories [

36]. Since 2015, the term has become a dense concept used by different perspectives [

17,

37]. Similarly, over the last 5 years the term “touristscape” has been used with increasing frequency taking often critical approaches to the geography of tourism [

38,

39].

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis

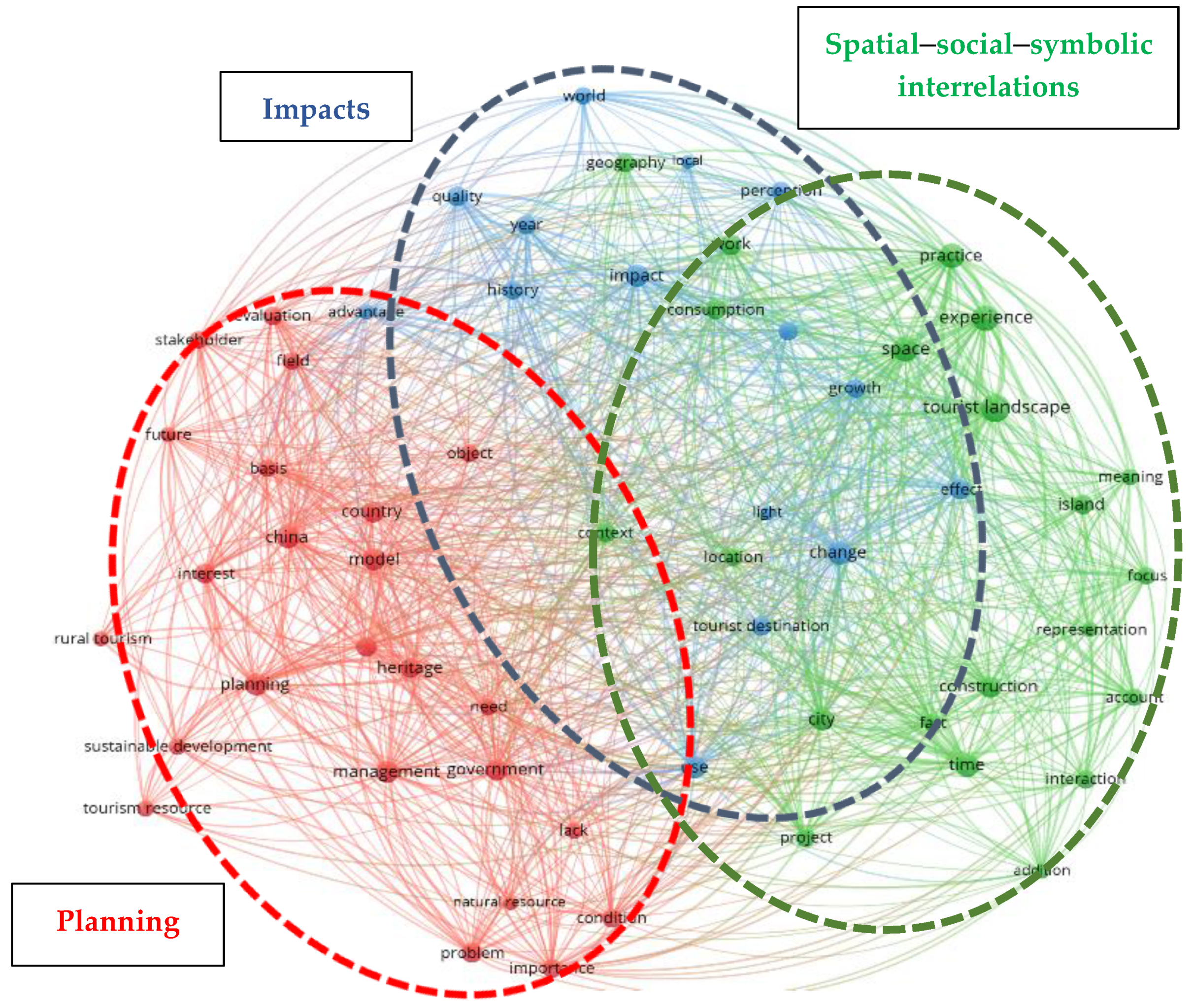

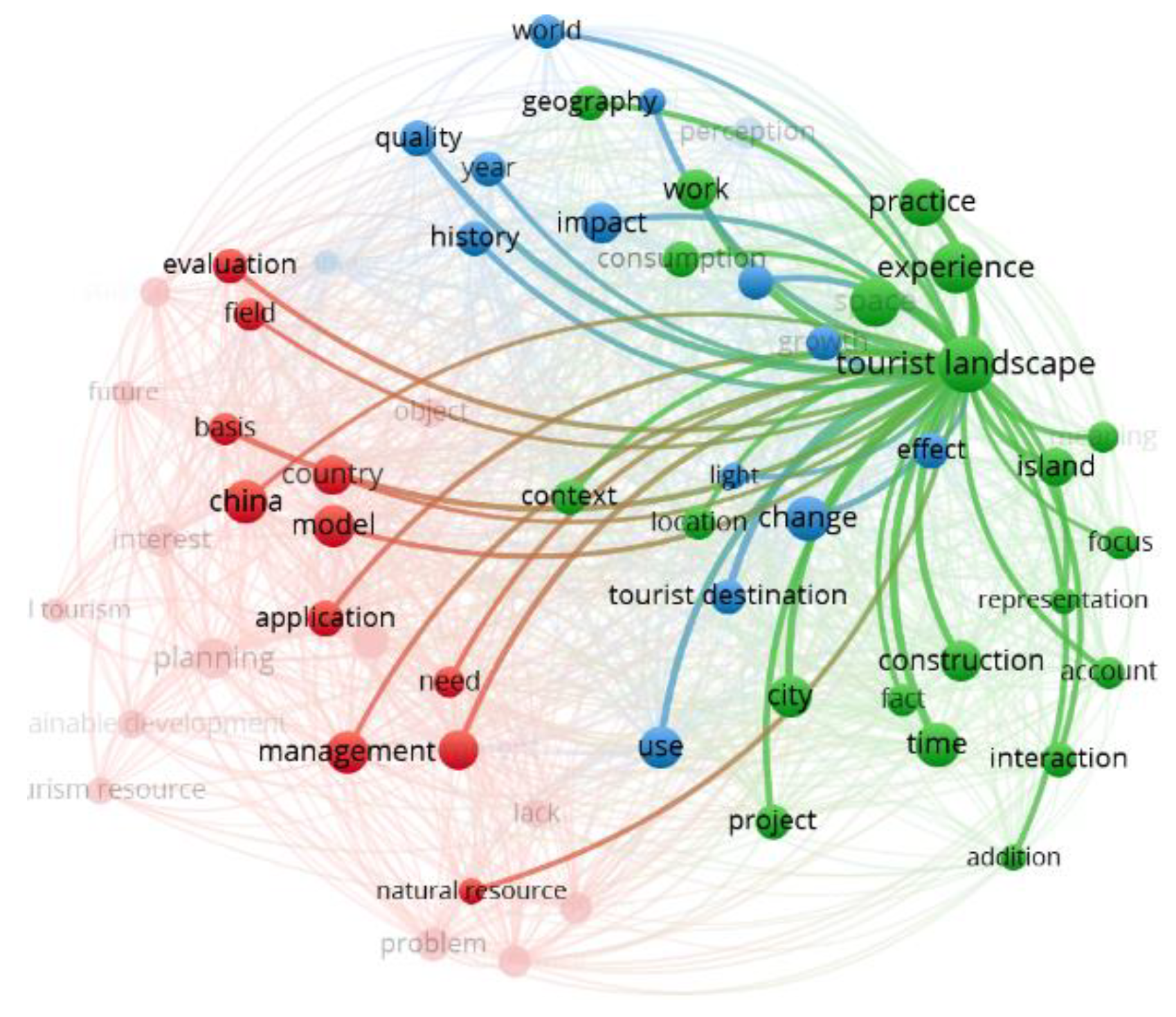

Based on the WOS corpus data made available to VOSviewer, a co-occurrence term map was returned. The network map, displayed through VOS Viewer Network Visualization, was comprised by a set of items with links between them. The obtained map presented 60 relevant terms (or phrasal terms) related by co-occurrence links. Each term in map had a color to indicate the groupings (clusters) of terms. Cluster aggregate terms tended to be more closely related. The obtained map presents three clusters.

The following table (

Table 2) lists the items with their number of occurrences and related clustering group. Clusters are numbered with 1, 2, and 3 according to the numerosity of their items.

As explained in the VOSViewer Manual, “relevant terms tend to be representative of specific topics” [

31] (p. 35). Based on this validation, the three visualized clusters (

Figure 4) have been designated with the three following names referring to possible research topics:

Cluster 1—Planning and governance (red);

Cluster 2—Spatial–social–symbolic interrelations (green);

Cluster 3—Impact evaluation (blue).

Items in the clusters are grouped by VOSviewer into different colors. Terms with the same color tend to co-occur with each other more frequently than terms with different colors. The clusters were named by the author.

Some evidence can be illustrated. The first evidence is that the expression “tourist landscape” has obtained the highest ranking (40 occurrences). Although it was expected to naturally impact the formation of clusters, its frequency and variety of use in different research areas confirms that is the most appropriate expression to describe the nexus. As argued, other expressions are more often associated with specific research areas and periods. In fact, “tourism landscape”, “tourismscape”, and “touristscape” did not exceed the threshold indicated. Another important finding is that “tourist landscape” is included in Cluster 2. The Cluster 2 has been named “Spatial–social–symbolic interrelations”, implying the centrality of the expression in reflections describing the interrelation between the phenomenon of tourism and the situated construction, reconstruction and reproduction of landscape though practices and representations.

Since the clusters were suggesting key topics related to the nexus, both general and specific inferences deriving from the observation of the map were made and successively verified through the implementation of the content analysis.

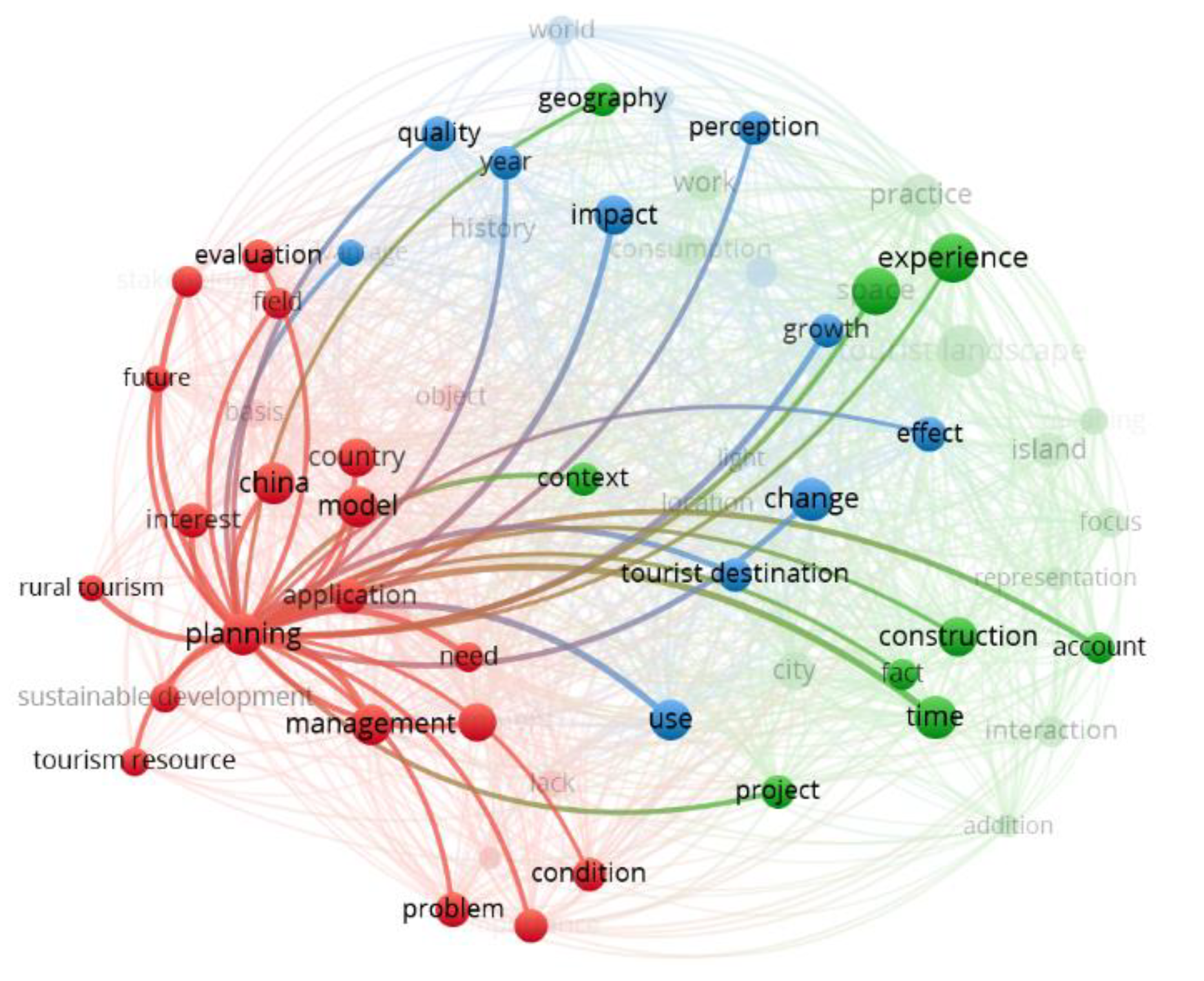

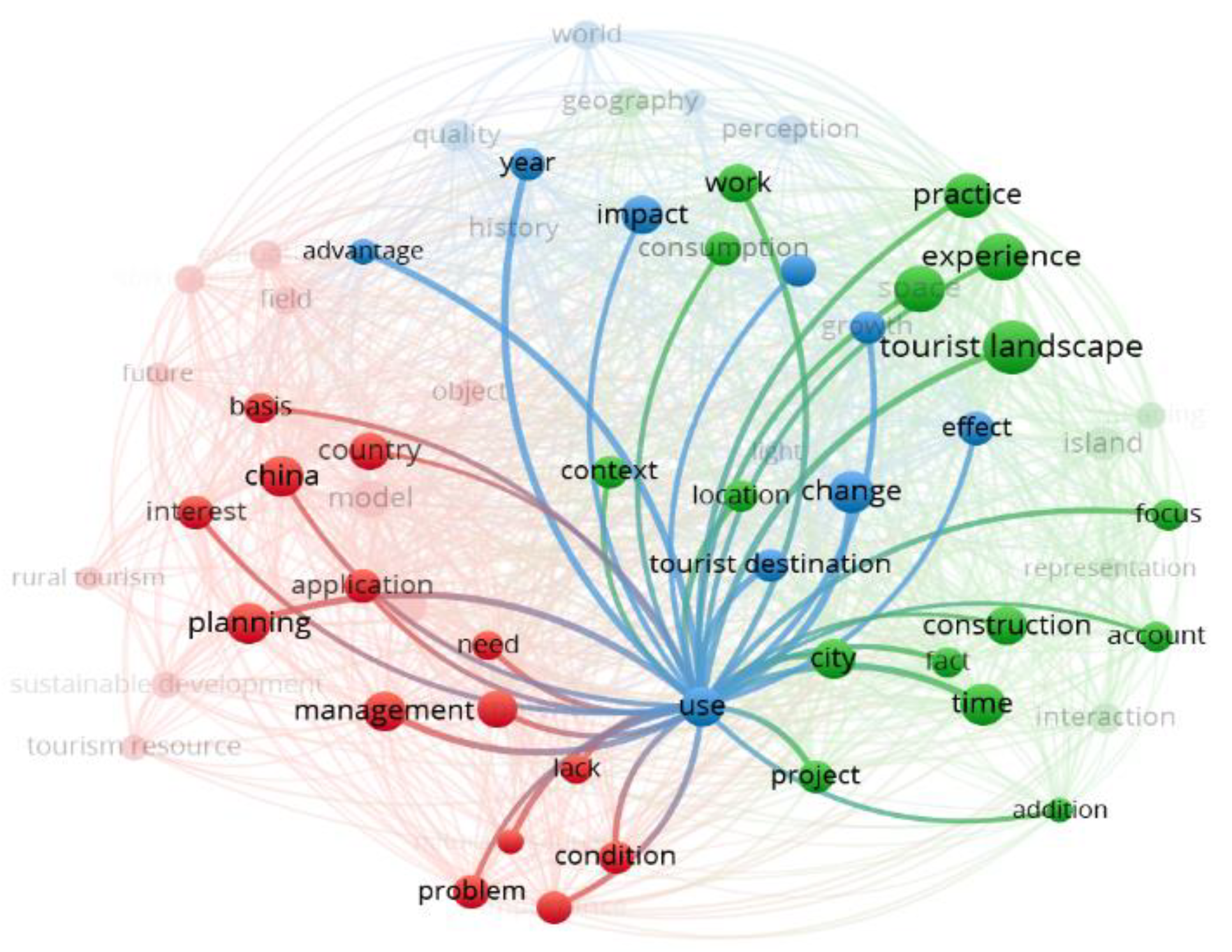

3.2.1. Planning and Governance—Key Topic 1

It can be implied that Cluster 1, named “Planning and governance”, includes terms co-occurring in publications where landscape is considered a resource with a specific value for the tourism system. In the following sub-map (

Figure 5), the co-occurrences of the second most recurrent item “Planning” of Cluster 1 are visualized (“China” is the most recurrent term. Its performance refers to the recent increasing number of Chinese publications investigating specific Chinese contexts).

It can be inferred that the most recurrent terms “Planning”, “Management”, “Governance”, and “Stakeholders” are mostly framed within “Sustainable Development” contributions, and terms “Model”, “Application”, “Problem”, “Lack”, “Need”, “Importance”, “Condition”, “Interest”, and “Future” redirect to typical vocabularies of destination planning and management processes and their implementation tools, i.e., feasibility studies and “Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats” (SWOT) analyses. Landscape is part of the tourism system (“Object”) and can be assessed in research for its physical–environmental components to be protected (“Natural Resource” and “Rural Tourism”), or for its historical–patrimonial values to be safeguarded (“Heritage”), or for its tourist dimension to be enhanced (“Tourism Resource”).

3.2.2. Spatial–Social–Symbolic Interrelations—Key Topic 2

Cluster 2 includes the co-occurrences of the terms “Tourist Landscape” (

Figure 6), “Experience”, and “Practice”, among others. They seem to refer to the spatial–social–symbolic dimensions and interrelations describing tourism experiences where the practitioner–landscape relationship is key. The recurrent terms “Space”, “Time”, “Context”, and “Interaction” demonstrate the research interest in specific lived situations. It can be implied that this cluster aggregates publications where landscape is not a mere scenic background to look at but a place to be experienced in a situated and multisensory way.

A specific research position about the “landscape–tourism” nexus can be assumed. It focuses on landscape subjectivity and an active role in tourism experiences. There is a functional, mediatory role of landscape in defining and co-creating spatial, social, and symbolic relations (“Construction”, “Consumption”). Even though these contributions tend to overlap the term “Tourist Landscape” with the term “Space” without distinction, they seem to contribute to analyzing tourism practices of landscape and their construction mechanisms. Tourism experiences can be real, virtual and even only imagined “Practices”. It can be implied that this cluster also aggregates production on the media-induced landscape as sub-topic with “meaning” and “representation” among recurrent terms.

3.2.3. Impact Evaluation—Key Topic 3

Cluster 3 seems to refer to the transformative aspects of tourism dynamics on landscapes. Therefore, it could broadly represent reflections on positive and negative impacts of tourism planning, management, and experience/representation. Besides “Use” (

Figure 7), “Impact”, and “Effect”, most recurrent terms are “Change”, “Growth”, possibly referring to the landscape evolutionary process. Other terms, for instance, “Advantage”, “Opportunity”, and “Quality”, redirect to related landscape assessment terminology.

The keywords “World”, “Local”, and “Tourist Destination” could imply both geo-political investigations of the process of globalization and investigations on the role of local entities and practices for the quality of life and well-being of communities.

Finally, Cluster 3 seems to aggregate contributions investigating tourists and residents’ perception about landscapes’ transformative process though an historical perspectives. The terms “Perception”, “Year”, and “History” could refer to this sub-topic.

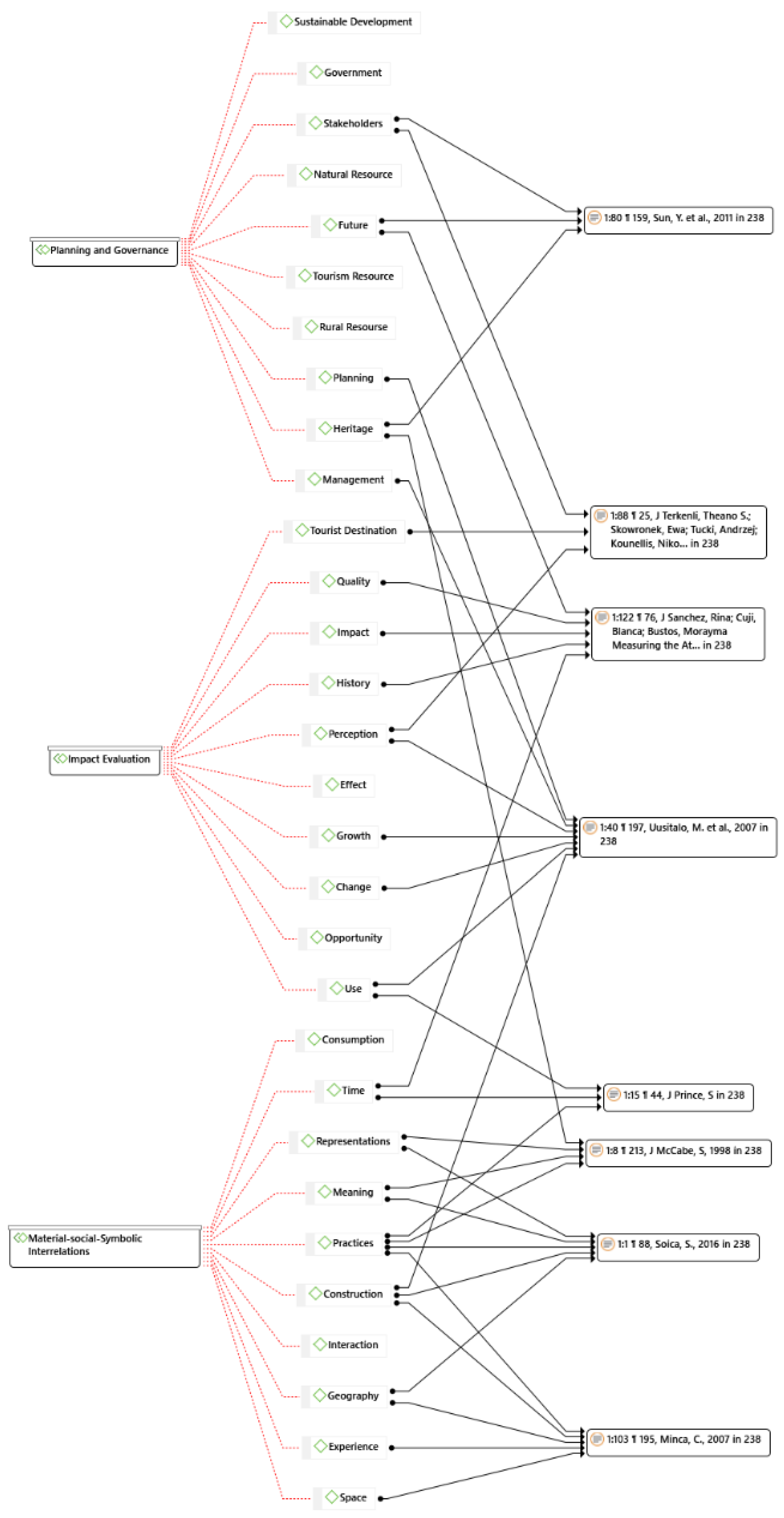

3.3. Content Analysis

To verify first inductive interpretations about the three emerging research topics, a content analysis was implemented. Content analyses allow the investigation of specific research issues and themes through a hierarchical system of group-codes and codes referring to specific conceptual categories and sub-categories in a selected corpus.

The following three group-codes, corresponding to the three previously emerged research topics, were used from the beginning of the categorization process:

Each group-code was associated with 10 codes corresponding to the most significant items in the clustering groups.

Next, the figure shows the ATLAS.ti hierarchical scheme derived from the selected publications with the three group-codes and the 10 codes assigned to each family (

Figure 8). The software assesses groundness and density as main values [

33], describing connected nodes emerging from links. Groundness refers to the number of linked quotations and density counts the number of linked codes. The higher the G-count for a node, the more grounded is it in the data set. The higher the D-count for a node, the denser the surrounding network. For example, in

Figure 8 the code “Practices” is the node with the highest G-count of its group-code: “Spatial–social–symbolic Interrelations”.

Linking literature quotations to the proposed system of conceptual code-families and codes has allowed grouping scholarly production according to the three specific key topics and proving the relationship between publication content and key topics.

In particular, it has allowed for qualitatively exploring: (i) publication content positioning according to the coding system; (ii) publication content features according to investigated issues and related methodologies; (iii) emerging key themes from linkages (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Obtained maps offer interesting insights about the conceptual broadness of different scientific contributions in their capacity to use a specific definition to address key topics.

According to the relationship between publications and research topics as well as literature positioning in the coding system, the following paragraphs provide evidence for the first “suggestions” derived from the bibliometric analysis and help to unfold emerging key themes of the field.

3.3.1. Key Research Themes from Group-Code 1—Planning and Governance

The publications with the greatest associations to this family of codes have, as their aim, indicating planning and management strategies for landscapes or tourism systems or unspecified “tourist landscapes”. Therefore, the first assumptions deriving from emerging terms in Cluster 1 are supported by evidence.

Two dichotomous research directions emerge. On the one hand, there is a prevailing approach fed mainly by scholars of landscape studies more or less conservative towards landscape management in tourism contexts. They are largely geographical studies applying a systemic approach to landscape [

18,

19,

20], sometimes considered only in its physical parts. In this perspective tourism is considered as one of the socio-economic dynamics of the whole geographical system defining and informing the analyzed landscape. Hence, tourism is studied for its being functional to the landscape system. On the other hand, there are studies of destination management and territorial marketing that highlight the attractiveness of the landscape for the positioning of tourist destinations and products [

11,

12]. Many economics and business studies investigate these topics starting from a systemic approach to the tourism sector. This perspective is totally opposite to the previous one and assesses landscape for its value as potential tourism resource or tourism attraction according to the different phase of the destination life cycle. Many studies on destination management and marketing face the role of local resources in the tourism system defining the different typologies of tourism from both the demand and the supply sides, i.e., ecotourism, cultural tourism, and thermal tourism. Landscape is, therefore, studied as a functional part of the tourism system [

40]. More specific research objectives concern the role of different destination stakeholders, institutions and businesses in the planning and governance of landscapes or tourism destinations. The perspective of sustainable development frames most of this literature.

The analyzed case studies are often on a national scale, or the scale refers to the territorial level of the specific tourist destination/landscape. They are often reflections on the physical components of landscapes/destination resources. Therefore, the results are prevalent contributions on specific tourism types, i.e., natural tourism, rural tourism, costal tourism, mountain tourism, cycle tourism.

From a methodological point of view, there is an evident effort in developing descriptive models of economic, socio-economic, and socio-ecological systems, depending on the research field. There is a large use of mixed methods to conceptually define research design, research strategies, survey design, and data collecting. Whereas quantitative surveys based on statistical analysis techniques and structuring questionnaires are frequently used to assess values and behavior of tourists, operators or host communities and similar research issues, modelling is more frequent when different territorial elements need to be mapped [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Qualitative approaches (i.e., content analyses or guided structured or unstructured interviews) are useful to investigate policy and promotional documents and to collect different point of views concerning specific research issues [

51,

52,

53,

54]. Most articles demonstrate theoretical argumentations through the analyses of case studies.

The results of the present qualitative content analysis can be found in the following table, listing prevalent emerging key themes from Group-Code 1 with the number of related publications and exemplifying publications by theme (

Table 3).

3.3.2. Spatial–Social–Symbolic Interrelations—Key Research Themes from Group-Code 2

Group-Code 2 mostly aggregates contributions from post-modern and post-structuralist literature on the two themes: landscape and tourism. Investigations on the Spatial–social–symbolic Interrelations defining the nexus is the main key issue. Descriptions of tourist contexts where landscape is the result of negotiated and unnegotiated dynamics among situated and ordinary gazes and encounters is another important key issue [

55,

56,

57]. Therefore, first considerations of Cluster 2 of the bibliometric analysis can be demonstrated.

The influence of the “new paradigm of mobilities” [

58] and the phenomenological turn towards the so-called non-representational [

59] and more-than-representational [

60,

61] approach on the interrelation between tourism phenomenon and landscape construction, reconstruction and consumption is evident in the publications aggregated by Group-Code 2.

The concept of “taskscape” [

62], describing space as a social expression of human incessant body movements in ordinary and everyday activities, emphasizes the importance of relating to places not in passive-contemplative terms but in an active-operative way as “participating” vital and involved subjects. Since 2000 this definition has been widely adopted by tourism scholars [

63,

64,

65,

66]. In tourism studies the concept of “tourism practices” intended as a mode of vital and performative “being”, i.e., intersubjective practice in tourist places [

67,

68] have provided a step beyond the pure landscape gazing [

69]. This conceptual leap has opened up a wide field of investigations. In particular, the most influencing contributions have come from human geography, sociology and semiotics. The focus has often been stressed upon the issue of social construction of meaning [

70], semiological realization of space [

71] with the application of semiotics to tourism [

72], and a combination of performative approaches to semiotics [

73]. This research field has produced a variety of recurrent expressions with the suffix “-scapes”. From the reassuring “touristscapes”, derivation of artificial codes of governance and control to more specific and unpredictable “smellscapes” and “soundscapes” [

68]. In general, the vocabulary of tourism studies from this research area has been enriched with an innovative and semantically richer language using nouns, such as “interaction”, “contextualization”, “encounter”, “engagements”, and “experience”, adjectives and adverbs, such as “sensual”, “embedded”, “entangled”, “bodily”, “unruly”, and “liminal” [

74], and verbs, such as “staging” and “performing”. Economics and business have also faced a paradigm shift influenced by the different social turns. The book

The Experience Economy [

75] introduced the vocabulary of “performance”, “experience”, and “corporeality” in business language referring to performative consumers and experiential products. These concepts absorbed then by tourism economics and business [

76] have emphasized as key issues the interactions between producer and consumer, the co-creation of tailor-made services, the personalization of tourism products, and the conceptualization of experiential typologies of tourism.

Regarding the territorial level, this broad literature refers mainly to the specificity of the context where the phenomenon of tourism interrelates the construction, reconstruction, and consumption of landscape. It is generally the geographical area of the tourist destination.

From a methodological point of view, extensive ethnographic fieldwork is largely carried out in investigated areas. Fieldwork involves observation, face-to-face interviews, questionnaires, and the collection of audio–visual material [

77]. These are preferred techniques to unfold and understand perceptive and affective mechanisms defining and influencing interactions. The researcher’s position and reflexivity in this qualitative research is a key issue of the debate [

78]. A mixed qualitative and quantitative methodology can be assessed when researching behaviors, perceptions, opinions interviewing tourists, host communities, and stakeholders, also from a psychological and/or marketing perspective. Content analyses can be used to assess and interpret messages from textual, visual, and audio materials, i.e., promotional brochures, websites, user generated content on social media. Economics and business studies have recently developed sentiment analysis to identify customer sentiment toward tourism products, brands, or services in online conversations and feedback. Most articles included in this group-code demonstrate theoretical argumentations addressing the key issues to specific geographical case studies. The following table lists the main key themes, number of related articles from group-code 2, and exemplifying publications by theme (

Table 4).

3.3.3. Impact Evaluation—Key Research Themes from Group-Code 3

Group-code 3 refers to the transformative aspects of tourism phenomenon for the landscape. The key issue is the investigation on the positive or negative impacts generating by the interrelations of the tourism phenomenon with spatial, social, and symbolic components of landscape. Most studies are framed in the perspectives of sustainable development [

89]. The first inferences deriving from the bibliometric analysis can also be confirmed for Cluster 3.

A wide group of critical research, mostly referring to urban contexts deals with the issue of globalization processes and the role of multi-scalar global entities impacting and often depowering the role of national and local entities. Large cities, global commodity chains, and technological platforms are broadly investigated for their being simultaneously local actors and part of global dynamics. Urban movements struggling to contain geo-political processes of physical and symbolic transformations of landscapes over time is also a key research issue. Other critical research areas analyze the enclavisation process on a destination scale leading to the definition of artificial “touristed landscapes”. Case studies largely refer to rural, coastal, and mountain landscapes turned to “tourist bubbles” [

90,

91,

92] and relevant key issues are investigation on land use [

93], depletion of local communities and related injustices, and power inequalities in labor relations [

94].

Impact assessments also study the positive effects of tourism as a driver of social-economic sustainable development. Publications underline the relation between tourism impacts and the quality of life of residents [

95,

96]; the role of tourism in fostering fishing, agriculture, and other economic activities [

97]; a stronger awareness of landscape and heritage values in terms of preservation and management.

The two main research fields are economics and geography. The economics and business perspective investigates economic impacts, whereas socio-geographical studies focus on environmental, social, and symbolic impacts. Interdisciplinary approaches are also evident from the intersection with historical, sociological and political disciplines.

Quantitative methods have a primary role in economics and business literature where indicator and index construction represent most contributions. Geographical studies often map the spatial dimension of landscape though modern information technology. Examples of innovative studies can be found under GIScience [

98]. Relevant contributions come also from geo-tourism, in which recent literature contributes to shifting from a restricted focus on physical elements to a broader concept of “tourist landscape” where investigation on heritage interpretation and actors’ engagement address political ecology issues [

99,

100,

101,

102]. The following table lists the main key themes, number of related articles from group-code 3, and exemplifying publications by theme (

Table 5).

3.4. Focus on Definitional Aspects of the Nexus as Emerged from Content Analysis

This paragraph intends to deepen what was anticipated in

Section 3.1 on the use of specific definitions of the “landscape–tourism” nexus. The aim here is to focus on the differences in adopted definitions according to the emerged key topics and themes.

Concerning the research topic “Planning and Governance”, it can be highlighted that, until 2010, the terms “tourism landscape” and “tourist landscape” were used indistinctly. Since 2010 the use of “tourist landscape” was prevalent in systemic landscape studies [

30]. Literature from AN Theories applied to tourism provides in 2007 [

36], the first definition of “tourismscape” as a network of actors that transcends the individual society and region and connects transport systems, accommodation, services, tourism resources, environments, tech-nologies, people and organizations [

36,

115]. In 2015, sectorial research fields, such as geo-tourism, use the term “tourismscape” to open towards innovative contributions attempting to bridge conflicts in tourism landscape research [

17].

Regarding the research topic “Spatial–social–symbolic Interrelations”, as already stated, the book

Leisure and Tourism Landscapes: Social and Cultural Geographies [

23] stimulated an increasingly widespread use of the expression “tourism landscape”. The book highlighted the primary role of socio-cultural reflections to investigate tourism practices. This volume, reviewed in 2004 in

Tourism Management by Hall [

116], contributed to shifting the reflection on the relationship between landscape and tourism towards a more radical epistemological perspective revolving around the material production, reproduction, and consumption of landscapes. In 2007, the publication

The tourist landscape paradox by Minca [

25] represented another boost in this research field. From a performative perspective [

65] and influenced by Cosgrove’s lecture [

117], Minca focused on the practices of the gaze within the framework of the “tourist landscape”. This definition is still evident in social sciences, mostly in publications where the transformation of ordinary places due to tourism’s dynamics is the focus. Non-representational approaches [

80] and reflections on the performativity of tourist practices in and out of the context of everyday life [

57] largely use the definition of “tourist landscape”.

Finally, since the 1980s, the broad field of literature investigating the research topic “Effects” inaugurated the use of specific definitions to describe interrelations between landscape and tourism. The term “tourism landscape” was used to describe the variety of territorial transformative aspects [

118]. From an epistemological point of view, this definitional phase can be described, as stated by Terkenli [

15] as “a large body of work largely apolitical, informed more by economic concern for landscape development” (p. 342). As previously described, it was from 2010 that many publications started the use of the term “tourist landscape” in social sciences. Many contributions on the specific topic have been referred to as the evaluation of aesthetic values attributed to the landscape or the landscape perception by tourists, stakeholders, and host communities. With reference to the specific thematic topic, the use of both terms “touristscape” and “tourismscape” is recent and mostly supports critical reflections on geopolitical processes of globalization and tourism consumption research [

37].

4. Discussion

4.1. Towards an Integrative Conceptual Framework Defining Tourist Landscape

The following paragraphs suggest a discussion about a tentative conceptual framework defining “tourist landscape” as result of the whole bibliographic study.

In particular, the bibliometric analysis has returned through VOSviewer three clusters indicating possible research topics addressing the “landscape–tourism” nexus. They are planning and governance, situated spatial–social–symbolic interrelations, and impact evaluation. The subsequent cluster analysis has confirmed the research topics pointing out a series of thematic categories helping to describe prevalent research fields.

Upon observing the results of the overall bibliographic analysis, the coincidence with Terkenli’s reflections on research strands about the nexus as described in her enlightening article

Tourism and landscape [

15] becomes evident. Terkenli argued that the increasing focus on the relationship of tourism with the landscape has been the result of three distinctive tendencies: an international, largely European, interest in landscape values, landscape planning and policy, and assessment/analytical methodologies; the dominant role of structuralist, post-modern, and post-structuralist perspectives on landscape in social and cultural geographies of tourism focusing on the complex interrelationships between the phenomenon of tourism and the construction, reconstruction, and consumption of landscape; finally, a more evident process of tourism development transforming different landscapes (p. 341). This coincidence has been further deepened to inform the following discussion.

The centrality of “tourist landscape” as both a relevant research item and orienting code has decisively influenced throughout the investigation the indication of key research topics, issues, and emerging themes. Both quantitative and qualitative approaches have unfolded the importance of this definition in investigating the “landscape–tourism” nexus in a comprehensive way. In particular, the bibliometric analysis assigning to the expression a primary role in investigating the “Spatial–social–symbolic Interrelations” key topic has revealed its possible function in defining tourist contexts where the positions of people (the observer/practitioner) define types of places and practices [

119]. Similarly, by assuming the role of “tourist landscape” as a possible significant group-code connecting different sub-codes, the content analysis has attributed to the definition a functional role in positioning scientific contributions on the basis of their multidisciplinary and inclusivity versus sectoriality and exclusivity.

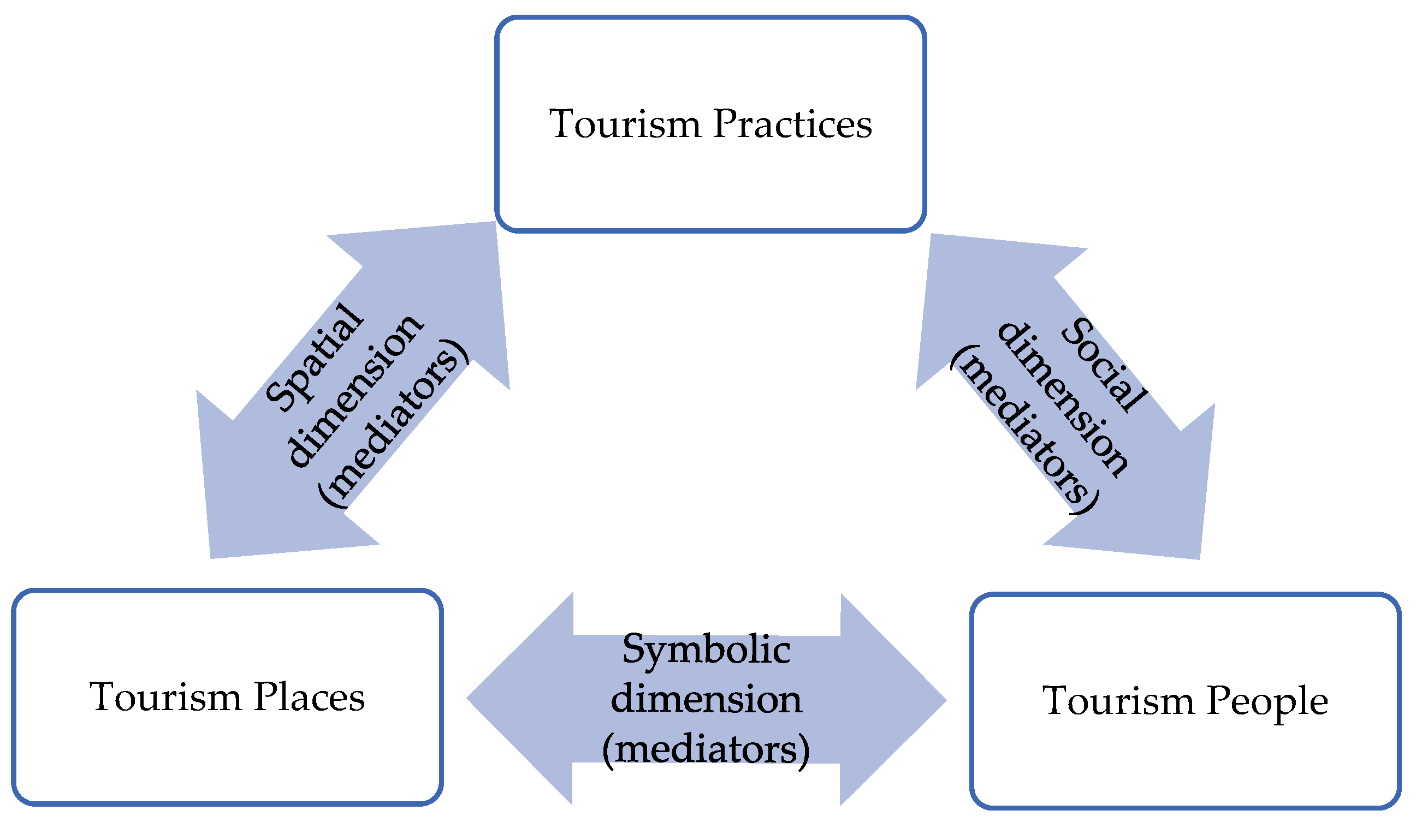

Starting from the scholarly definitions of “tourist landscape”, the overall hypothesis emerging from the described research outcomes is that “tourist landscape” can be broadly defined as the interrelations among three components of the tourism phenomenon, i.e., tourism people, places and practices where the primary role of the concept of “Practice” needs to be stressed. In more detail, this tentative definition indicates practice as situated tourism experience including services and other facilitating aspects, places as physical destinations wherever experiences occur including non-human [

86], material and immaterial resources and the way they can be encountered, and people as both internal and external human actors involved in tourism dynamics.

In particular, in tourism contexts the relation between place and practice defines a material–spatial dimension, the relation between practice and people defines a social–experiential dimension, the relation between people and place defines a cultural–symbolic dimension (

Figure 11). The present hypothesis originates from the research relevance of spatial, social, and symbolic interrelations as both a key topic and group-code. Besides, the concept of “trilogy” in Terkenli, naming the “landscape–tourism” nexus through the “interrelations between material, experiential, and symbolic properties” [

24] (p. 234) could sustain this possible definition.

The second and consequent conceptual hypothesis concerns the role of “mediators” in describing “tourist landscapes”. More specifically, three types of mediators could act in “tourist landscape”. These mediators can act on the three described dimensions. Accordingly, spatial–material mediators, social–experiential mediators, and cultural–symbolic mediators can be recognized. In particular, the relation between tourism practices and places could be facilitated by spatial mediators [

81,

120]. Second, the relation between tourism practices and actors could be facilitated by social mediators or switchers [

66]. Finally, the relation between tourism places and actors could be facilitated by symbolic-cultural representations [

73,

121]. They can have a role in structuring, shaping, strengthening, and facilitating the three dimensions. Examples of spatial mediators can be represented by specific forms of mobilities and/or multi-sensory devices (bike, app for sound itineraries) which can favorite landscape entanglements. Examples of social mediators can be represented by specific actors, such as incoming travel agencies, tour guides, artisans, and residents, which can favorite mutual interactions [

122]. Finally, example of symbolic mediators can be expressed by specific representations of real practices [

123]. In the end, mediators’ typology and

modus operandi can contribute to describing different typologies of “tourist landscapes”. The agent role of “mediators” in tourist contexts and dynamics can open a wide field of investigation embracing various research areas from sociology to management, such as agency theory and stakeholder management, among others. Being aware of this issue, it seems important, in any respect, to report this embryonal hypothesis here to stimulate further questions and discussions about mediators’ possible roles in defining and describing “tourist landscapes”.

4.2. Implications for Theory and Policy

The first implication deriving from the research outcomes for both theory and practice is that the proposed definition of “tourist landscape” as spatial–social–symbolic interrelations among tourism place, people, practice, and possible mediators can arise awareness about the complexity of the nexus and foster a more evident contamination from analyses concentrating on contextualized “tourist landscape” in their inner dynamics and components to planning and governance or evaluation insights.

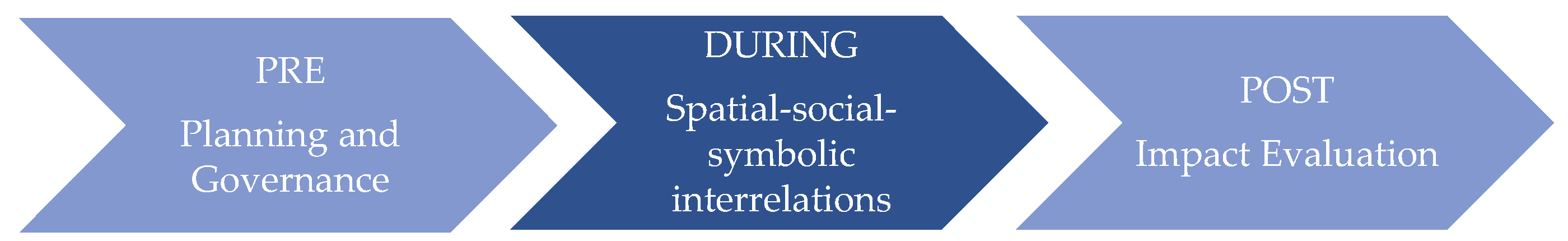

The second implication derives from the three key research topics. They have stimulated the definition of the proposed definition of “tourist landscape” as well as the following conceptual framework (

Figure 12). It is the representation of a tentative epistemological process possibly able to further support integrated theoretical and practical reflections on the nexus. In particular, it could help in circumscribing investigated objects in their processual stage, regardless the scientific field or the specific territorial questions.

In order to investigate, plan, governance, and evaluate, the individuation of the processual phase is as important as the assessment of the specific “tourist landscape”. Accordingly, the proposed framework can help in identifying also adequate methods and tools to face the specific theoretical or operational needs.

Finally, the discussion leads to possible policy implications. Ultimately, highlighting the complexity of “tourist landscapes”, overall research outcomes, proposed frameworks, and definitional aspects force landscape plans to confront tourism plans and vice versa in comparing and sharing objectives and strategies on the nexus. Whereas some of the superficialities found at the practical level could derive from both the limited dialogue between the different theoretical approaches and a broad inadequate understanding of the complexity of the nexus, the concreteness and strength of landscape as political instruments for stakeholders in orienting decisions and actions emerge. Moreover, landscape as a tool can play a primary social mediating part in educating, informing, sharing collective perceptions, and guiding on the different issues [

124,

125]. This is one of the possible ways to give substance to the indications of the European Landscape Convention.

5. Conclusions

The “landscape–tourism” nexus has been analyzed in the literature, assessing the prevailing definitions used to describe it and investigating the specific research issues.

The implemented bibliometric analysis has returned three main research topics: planning and governance, situated spatial-social-symbolic interrelations, and impact evaluation. Moreover, the defined cluster analysis has pointed out a series of thematic categories under the emerged topics helping in describing the prevalent research fields, the consistency of the production per topic, and the use of different definitions of the nexus in relation to the thematic category.

According to emerged topics and themes, the two main research fields are physical and human geography and economics and business. The prevailing approaches to the nexus highlight a diversity in perspective. Whereas geographic studies consider landscape mainly as a system of which tourism dynamics are a part, economic investigations assess tourism phenomena as a system where landscape is often considered one of its resources.

The selected literature refers mostly to Planning and Governance themes, such as landscape as a valuable resource, landscape attractivity, destination infrastructures, services and facilities, role of institutions, business and society, and destination sustainable development. This comprised 44.5% of analyzed publications, i.e., the oldest approach to the nexus dated back to the 1980s. This consistency is also explained by the intense scientific production from China that, over the last decade, has seen an increase in the number of investigations on the specific research topic. Selected contributions on impact evaluation count for the 34% and investigate largely economic, environmental, and social impacts with a focus on land use and consumption, effects of place making and transformation and image construction, patrimonialization of cultural resources, national identity, and memory, and historical changes in local and tourist perceptions. Starting from the 2000s, the scientific production on these topics has shown a steady distribution over the years. Finally, the literature on the situated spatial–social–symbolic interrelations between the tourism phenomenon and landscape included 18.9% of the corpus. The main thematic concerns were the types of practices and representations in landscape spatial definition and meaning, role of spatial, social, and symbolic interrelations in tourism experiences, function of tangible and intangible, and human and non-human mediating agents. These approaches are the most recent ones. Reflections on the relational dimension of landscape matured in tourism studies around 2010 and only in the following years have begun to consolidate and guide more frequently theoretical investigations.

Concerning the definitional aspect, a general lack of attention to the use of specific terms has emerged. Since the 1980s, the term “tourism landscape” has been mostly used in contributions of physical geography and economics, considering landscape as a potential tourism resource or attraction, whereas “tourist landscape” has mainly been dominant where scholars investigate the conceptual complexity of landscape from its relational dimension. From 2010, the prevalence of “tourist landscape” has been noted in all disciplines. Recently, thanks to a few but precise definitional efforts (2.5% of the analyzed corpus), awareness of terminological issues seems to have increased. Definitions, such as “touristed landscape” and “touristic landscape”, often contain a negative connotation that refers to the critical impact evaluations from geographical inquiries through political and sociological lenses. Finally, the research underlines the recent emergence of the terms “touristscape” and “tourismscape”, referring to interesting multidisciplinary reflections on the nexus.

The outputs of the whole bibliographic analysis stimulate the proposal of a tentative definition of “tourist landscape” as the interrelation of tourism places, people, practices, and mediators. This definition is explained by the presence of specific aspects referring to a tourist dimension of the landscape. In addition, the proposed definition considers the variety of conceptual and operational fields in which it might be used.

From the described research outcomes are derived both theoretical and practical implications. The application of specific and thoughtful definitions forces scholars and stakeholders to start inquiries considering the complexity of the nexus and the possibility to draw from a broad set of approaches according to the circumscribed research or political needs. In the end, it is necessary to describe the specific “tourist landscape” but also to position the investigated issue in order to clearly define objectives, tools and approaches.

Although the research has analyzed a selected literature corpus based on prevalent definitions of the nexus, both quantitative and qualitative methodologies have returned a variety of results and raised some hypotheses that need to be further explored. The proposed definition of “tourist landscape” needs to be additionally thought and explored by also applying it to specific research issues and case studies. In particular, the assessment of tourist practices in relation to the spatial, social, and symbolic specificities and the role of mediating agents in “tourist landscape” require both deeper and more detailed theoretical analyses.

Ultimately, the assessment of shared integrative conceptual frameworks and definitional aspects on the “landscape–tourism” nexus should definitely orient future investigations in a more evident way to animate theoretical confrontations feeding new geographies of tourism and to influence contemporary territorial debates and policies. The health emergency has led to the questioning of many interpretative schemes and operational solutions regarding both the landscape and the tourist phenomenon. The urgent need for new theoretical reflections and political agenda on the two themes could be addressed to focus more specifically on their nexus in order to hopefully find innovative and sustainable ways to interpret contemporary places, mobility and human beings in places.