Abstract

While empowering the revitalization of Chinese historic districts, the rapid development of the tourism industry may also endanger local cultures and streetscapes. To achieve the goal of sustainable development and find an approach for the Chinese historic districts to develop tourism while taking into account landscape conservation, district management, and living convenience, this paper uses expert interviews (including in-depth and Modified Delphi interviews) and structural observation to explore redefining Chinese historic districts and cultural tourism attractiveness in order to provide a hierarchical framework. The research results reveal: 1. The respective redefinitions of a Chinese historic district and cultural tourism attractiveness; 2. A hierarchical framework for the cultural tourism attractiveness of Chinese historic districts, using two aspects—the physical environment and the cultural and natural environments—and five criteria including the morphology of the landscape and tourism infrastructure, along with 21 elements, including the natural and cultural landscapes. This research is expected to provide a theoretical reference for the planning and management of tourism and landscapes in Chinese historic districts.

1. Introduction

Historic districts reflect the images of a city and form an important part of its historical legacy. The cultural value of historic districts still plays a key role in the economic development of modern cities [1,2]. However, the survival spaces of historic urban landscapes and traditional culture are being compressed by the rapidly developing modern economy with many historic districts bearing memories of the city having declined or disappeared in the process of globalization, urbanization, and commercialization [2,3,4,5,6]. Landscape conservation is conducive to satisfying not only the modernization of historical areas, but also the conservation of history, memory, and the environment [5]. Therefore, tourism attractiveness in this article does not focus on tourism development. It is both necessary and imperative that landscape conservation and the revitalization of historic districts’ happen [7,8,9], whilst supporting their sustainable development [10].

Tourism is a driving force for landscape conservation and sustainable development. However, the rapid development of the tourism industry may also affect the lives of residents, destroy the landscape and environment, and impair the quality of the tourist experience, leading to excessive commercialization, the disappearance of traditional culture, and other issues [9,11,12,13]. Therefore, to enable the sustainable development of historic districts, economic development, landscape conservation, and cultural inheritance should go hand-in-hand [11,14,15]. Cultural tourism can bridge economy and culture whilst contributing to the sustainable development of heritage sites [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. At the same time, how to introduce tourism to become a driving force for cultural heritage and urban renewal has become a hot topic world-wide [24]. Chinese historic districts are no exception. They are trying to pass on a district’s culture, boost its prosperity, and promote sustainable development by integrating the landscape resources in the district to support cultural tourism [25,26,27,28,29]. It could be said that the cultural tourism industry in Chinese historic districts attracts tourists with its own landscape resources which are a combination of the hardware environment and software culture, so that they find a balance between the historic nature of the district and the modernization of life, and eventually develop into sustainable districts. However, at present, the overall development of Chinese historic districts is facing the test of three pairs of contradictions specific to the conservation of their landscapes: protection and development, the new and the old, and the past and the present [30]. The relationship between tourism development and district conservation is difficult to balance [31]. It has caused conflicts between cultural conservation, economic development, residents’ interests, and management and planning [32]. Therefore, the core of the cultural heritage attractiveness is to handle the above-mentioned conflicts to a greater extent. Only in this way can Chinese historic districts truly achieve the goals of revitalization and sustainable development.

Within the large amount of related Chinese and foreign literature, scholars have taken various research perspectives to explore a district’s problems in-depth [33,34,35,36,37]. However, current research is constrained in three areas: in terms of research scope, some research has focused on historic districts on both sides of the Taiwan Straits or overseas Chinatowns; however, researchers have not provided a broad summary of what Chinese historic districts themed with Chinese cultural characteristics are [38,39,40]; in terms of research content, some of the research content has focused on tourism development or district conservation, but researchers have not explored how the attractiveness of cultural tourism satisfies both their tourism development and landscape conservation from the perspective of sustainable historic districts, nor have they systematically summarized the criteria and hierarchical framework for this process [41,42]; in terms of research method, the frameworks were mostly established based on integrations of literature collections, while expert interviews have been infrequently used to collect information and improve the research [32,43].

In this paper, expert interviews (both in-depth and using the Modified Delphi Method) and structured observations are taken as the research method to redefine the connotations of Chinese historic districts and cultural tourism attractiveness mainly based on expert opinions and the definitions of four term: “Chinese district”, “historic urban area”, “cultural tourism”, and “tourism attractiveness”, and to establish a hierarchical framework of cultural tourism attractiveness applicable to Chinese historic districts that takes landscape conservation and economic development into parallel consideration. Finally, Dadaocheng historic district in Taiwan will be taken as an example to show how the elements of the framework correspond to the real landscape in a historic district. The results of this research aim to provide a theoretical reference for the development of tourism and the landscape conservation of historic districts whilst aiming to achieve sustainable development.

2. Literature Review

The literature review mainly includes publications related to Chinese historic districts, cultural tourism attractiveness, and a hierarchical framework for historic districts and tourism attractiveness. The term “historic district” and related concepts include literature relating to the terms “historic area/city”, “historic urban areas”, “historic towns and urban areas”, “urban conservation”, and “historic urban”.

2.1. Chinese Historic Districts

In this section, the context of the two terms “Chinese district” and “historic urban area” are explored to facilitate the understanding of “Chinese historic district”.

The term “Chinese district” appeared in Chinese in the article “Chinese Communities in the Russian Far East (1891–1900)” and the book Famous Chinese Districts in the World: Chinatown. The former refers to the Chinese settlements in the Russian Far East, while the latter refers to overseas Chinatowns [38,44]. Both terms have Chinese cultural characteristics, but neither is a description of the dominant Chinese presence on both sides of the Taiwan Straits. Therefore, the author assumes that “Chinese districts” are the places where Chinese congregate and settle and which bear distinctive Chinese cultural characteristics. The scope of “Chinese districts” should include all districts around the world where Chinese culture predominates.

With regard to the definition of “historic district”, according to UNESCO(United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and ICOMOS(International Council on Monuments and Sites) International Council on Monuments and Sites), the scope of “historic area/city” and “historic districts” should cover both cities and rural areas [5,45,46]. ICOMOS holds that “historic urban areas” should include both the natural and human-made environments [47], and “historic towns and urban areas” should include “tangible elements” and “intangible elements’’ [9,46]. In mainland China and Taiwan, there are distinct definitions of “historic district”. In mainland China, the authorities emphasize that “the cultural relics preserved are particularly diversified, the historical buildings are clustered, and the traditional patterns and historical styles can be integrally and authentically manifested” [39]; whereas in Taiwan, the Tainan municipal government emphasizes “a group of buildings worthy of conservation and revitalization” [40]. It can be seen that international organizations have outlined the relevant scope and contents from a relatively macroscopic perspective, but their expression of the values is not so lucid. Mainland China and Taiwan have described the values in more detail, but they have not defined the contents and the scope.

To summarize, the concept of “Chinese historic district” should include both “Chinese district” and “historic district”, to emphasize the macroscopic scope and characteristics of a Chinese district, as well as the territory, contents, and value of a historic district.

2.2. Cultural Tourism Attractiveness

In this section, the context of the two terms “cultural tourism” and “tourism attractiveness” are explored to facilitate the understanding of “cultural tourism attractiveness”.

With regard to the definition of “cultural tourism”, Richards and UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization) held that cultural needs link people with tourism destinations [48,49], but they ignored the attracting effects of cultural resources; ICOMOS claimed that the cultural environment is a key feature [18], yet it neglected the roles of the physical and natural environments; the EU and COE (the European Union and the Council of Europe) proposed the three resources theory, which highlighted the roles of historic space and modernized function, yet they overlooked the experience and wishes of tourists [50]. Therefore, “cultural tourism” is a “cultural behavior” developed under the stimulation of cultural needs and cultural resources.

With regard to the definition of “tourism attractiveness”, Middleton et al. held that, from a demand perspective, tourism attractiveness originated from the subjective demands or feelings of tourists [51,52], but they ignored the roles of tourism resources; Gunn et al. held that, from a supply perspective, tourism attractiveness was a pull from the tourist destination [53,54], but they ignored the role of subjective demand; Iatu et al. integrated the two perspectives and proposed that both tourists’ demand and the resources of tourism destinations were the components of tourism attractiveness [55,56], yet they failed to describe the macro environment in which that attractiveness was developed. Therefore, the contents of tourism attractiveness should include the background and components leading to its development.

In a brief, the concept of “cultural tourism attractiveness” should include both “cultural tourism” and “tourism attractiveness”, to emphasize the core role of culture, as well as the development background and components of tourism attractiveness.

2.3. Hierarchical Framework of Historic Districts, Tourism Attractiveness, and Landscape Conservation

This section reviews the relevant content based on the establishment method, research contents, or scope of research into frameworks for evaluating historic streets, tourism attractiveness, or landscape conservation.

With regard to the hierarchical framework for historic districts, Ruoming Shi et al. established frameworks based in the literature where the former assessed the status of conservation and impacts, and the latter assessed the impact of conservation efforts on the sustainable development of a district from the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) perspective [32,43]. Liu et al. leveraged the textual analysis approach to analyze public comments and established a hierarchical framework to assess public perceptions of the authenticity of urban heritage [42]. It can be seen that the establishment of hierarchical frameworks has mainly relied on consolidating the existing literature and textual analysis with insufficient regard for input from experts in related fields. In terms of the research object, research has focused directly on areas related to heritage or landscape conservation and not on a direct exploration of district conservation, landscape conservation, and sustainable development from a second perspective, such as cultural tourism. Therefore, in this research, literature consolidation and expert input will be integrated to study sustainable districts and landscape conservation from a cultural tourism perspective.

With regard to the hierarchical framework of tourism attractiveness, the academic community has established hierarchical frameworks mainly through literature consolidation. In terms of scope, some of the research was country-based or county-based whilst other investigations were city-based with some being based on several areas within a country [57,58,59]. Sorting out a hierarchical framework from the literature could easily lead to the trap of being too subjective. If opinions of an expert panel were considered in amending this process, the decision-making could be more precise [60]. Since the scope of research is relatively diversified and its geographical base relatively vast reducing the scope of research to a single district might provide data and results of greater accuracy.

With regard to the hierarchical framework for landscape conservation, Francesca Nocca et al. directly established frameworks based in the literature where the former took cities as the research scope, trying to find out the relationship between landscape variation and wellbeing variation, and the latter took natural landscape conservation areas country-wide as the research scope, evaluating the status of natural landscapes in China based on the criteria of typicality, aesthetics, authenticity, integrity, and historical and cultural values [10,61]. Vassiliki Vlami et al. established frameworks based on a combination of literature review and extensive field trials, taking an island as the research scope to diagnose a holistic landscape for the purpose of conservation instead of evaluating from the perspective of traditional visual aesthetics [62]. It can be seen that the establishment of hierarchical frameworks was mainly based on a single review of the literature reviews; meanwhile, the research scope was too large, which increases the difficulty of the research and is prone to deviations in data collection. In terms of the research content, the research was insufficiently focused or too abstract. Therefore, during this research, the methods for establishing the hierarchical framework should be enriched, the research scope should be narrowed, and the specific elements related to landscape conservation should be studied.

In short, research into the “hierarchical framework of historic districts, tourism attractiveness, and landscape conservation” may take a single district as the scope of research, the cultural tourism attractiveness as the research content, and the sustainable district in the context of cultural and landscape conservation as the ultimate goal. This allows a hierarchical framework for scientific research into the specific element of landscape in the district to be established by combining literature consolidation and expert interviews.

3. Research Design

In this paper, three research methods have been used: in-depth interviews to aid the redefinition of terms, the Modified Delphi Method for the establishment of a hierarchical framework, and structured observation for the validation of the hierarchical framework. The same expert panel of 17 people in total were invited for the first two parts.

3.1. In-Depth Interviews

First, experts were introduced to the prototype definitions of terms obtained through literature consolidation. Experts then revised these definitions one-by-one until an agreement was reached (oral agreement or no questions raised) on every revised definition, which then became the final definitions.

3.2. Modified Delphi Method

This section consists of two parts: the process and the expert panel.

a. Process

This process was divided into two rounds. In Round 1, the Delphi items extracted from the references were organized into a semi-structured questionnaire. Experts then commented on each item’s applicability and the clarity of its contents. Then, the author used this expert input to make relevant corrections. In Round 2, the necessity for each corrected item and its content was rated, and an expert consensus reached [60,63]. During the whole process, each expert’s considerations and ratings for each item are equally important [64].

b. Expert Panel

On the composition of an expert panel, some scholars suggest that a panel should be heterogeneous rather than homogenous [65], with some scholars believing that a panel composed of 10–18 members is a reasonable number [66]. Following these suggestions and, at the same time, in order to avoid the conflicts caused by the imbalance between landscape preservation and tourism development affecting the sustainable development of the district, the expert panel was composed of 17 heterogeneous experts representing cultural and historic practitioners, district delegates, tourism practitioners, and planning and operating personnel. To ensure the integrity and accuracy of the elements in the hierarchical framework, the number of experts with corresponding expertise was evenly distributed. However, because experts might have multiple attributes, one expert might be reviewing more than one category. Since the members were selected based on the principle of having rich experience and knowledge, an understanding of the Delphi method, and a willingness to continue to participate in the research [67], all 17 experts participated in the whole research with no withdrawals or replacements.

c. Statistical Approach

In this paper, a six-point Likert-type scale was used to rate the necessity of using the criteria for the final hierarchical framework of cultural tourism attractiveness for Chinese historic districts. 1 point meant “strongly disagree”, 2 points “disagree”, 3 points “disagree with reservations”, 4 points “agree with reservations”, 5 points “agree”, and 6 points “strongly agree” [68]. The level of expert consensus could be judged according to the quartile deviation (QD). A QD < 0.6 meant a high consensus, 0.6 < QD ≤ 1 meant a moderate consensus, and QD > 1 meant no consensus was reached [68,69,70].

d. Criteria Screening Approach

The average value could be referenced when making a decision on the deletion of a criterion. The average value 3.5 was the neutral point. Those below 3.5 were very unlikely to occur or unlikely to occur as options, those above 3.5 (inclusive) were likely or very likely to occur as options [64,68]. Therefore, in this paper, a criterion with an average less than 3.5 was deleted, and a criterion with an average greater than or equal to 3.5 was retained.

3.3. Structured Observation

For the structured observation task, a handy and reliable checklist with a minimum of observations was used to obtain relevant visual information [71]. In this study, the hierarchical framework for the cultural tourism attractiveness of Chinese historic districts was used as the checklist, and the landscapes corresponding to the observation objects were located and photographed within a specific historic district. This provided a concrete illustration of how the framework elements correspond to the district landscape.

3.4. Scope of Research

When the hierarchical framework for the cultural tourism attractiveness of Chinese historic districts was used, the contents with obvious cultural tourism attractiveness were selected from the 21 items according to the situation of the corresponding district. As a consequence, selections made for different districts might differ. This was because the hierarchical framework only provided the possible (instead of absolute) causes of obvious cultural tourism attractiveness. In addition, this hierarchical framework provides a complete list of elements that may generate cultural tourism attractiveness; that is, the 21 items contents in the framework can be found in any Chinese historic district. The selection of contents with obvious cultural tourism attractiveness in a specific Chinese historic district was further considered using this framework; however, this lies beyond the scope of this paper.

4. Research Results

This section is composed of term redefinitions and the hierarchical framework. The first part covers the redefinitions of two terms: Chinese historic district and cultural tourism attractiveness; the second part covers the establishment of a hierarchical framework for the cultural tourism attractiveness of Chinese historic districts.

4.1. Redefinition of a Chinese Historic District and Cultural Tourism Attractiveness

This section includes both the prototype and final definitions.

4.1.1. Prototype Definition

According to the Literature Review, the prototype definitions of Chinese Historic District and Cultural Tourism Attractiveness are as follows (refer to Table 1).

Table 1.

Prototype definition of a Chinese historic district and cultural tourism attractiveness.

4.1.2. Final Definition

Experts made relevant suggestions for amendments to the definitions (refer to Literature Review for the supplementary references). The seventeen experts reached agreement on the amended definition of the two terms. The final versions are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Final definitions of a Chinese historic district and cultural tourism attractiveness.

4.2. A Hierarchical Framework for the Cultural Tourism Attractiveness of Chinese Historic Districts

This section consists of four parts: the prototype framework, the reasons for framework amendments, the amended framework, and the modified Delphi decision-making results.

4.2.1. The Prototype Framework

Based on the implicit assumptions of culture having three levels, formal, informal, and technical [72], the preservation of a historic urban landscape should cover both the physical and the human environment [5,73]. With marketing strategy constituting an important part of cultural asset management [2], the three cultural hierarchies correspond to the three aspects of the prototype: the physical environment, human environment, and tourism marketing. The difference between the two environmental aspects is that the former emphasizes the denotation of things whilst the latter stresses connotation of things [74].

To divide the three aspects further, the physical environment is composed of nature and natural resources, the building environment, and infrastructure [75]. The human environment can be divided into tangible and intangible cultural relics subject to the classification of cultural relics, where the former consists of both movable and immovable cultural relics [76], with the latter consisting of various traditional cultural expressions as well as related physical items and places [77]; tourism marketing covers the four elements of product, price, promotion, and place [78,79]. As a result, the above criteria provide the foundation for the prototype framework as in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Integrated preliminary aspects.

Table 4.

Integrated preliminary aspects.

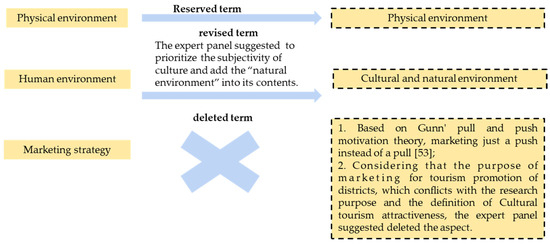

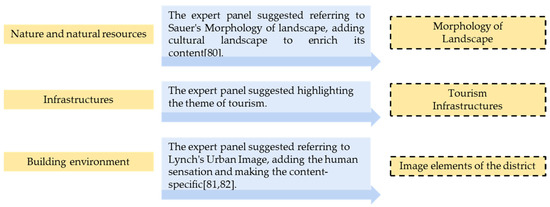

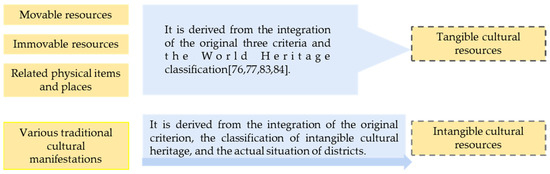

Because the prototype still had many imperfections, it was amended with the help and suggestions of the expert panel. The changes as shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3, the final descriptions of the amended framework as shown in Table 5 and Table 6.

Figure 1.

The Aspect Amendments [53].

Figure 2.

The Criteria Amendments in Physical Environment [80,81,82].

Figure 3.

The Criteria Amendments in Cultural and Natural Environment [76,77,83,84].

4.2.2. The Reasons for Amending the Framework

The hierarchical framework of cultural tourism attractiveness for Chinese historic districts was proposed based on an analysis of the literature, the experts’ input, and district circumstances. It consisted of 2 aspects, 5 criteria, and 21 content items. Considering that the research purpose of this article was not to attract more tourists, but to find a cultural tourism attractiveness that could satisfy both economic development and landscape conservation, the original aspect “marketing strategy” was deleted as a whole based on the suggestions of the expert panel. At the same time, this result also fits Gunn’s views on marketing as the push provided by tourist destinations, and tourism attractiveness as a pull from tourism [53]. For the remaining two aspects, experts suggested the following: 1. The aspects should be named in a way that could highlight their different attributes; and 2. In order to prioritize the subjectivity of culture, “cultural environment” should be substituted for “human environment”, with the term “natural environment” being added to cover both the cultural and natural domains.

Physical Environment

This aspect consisted of three criteria: morphology of landscape, tourism infrastructure, and image elements of the district.

Morphology of landscape (A1): The original criterion “nature and natural resources” could be considered as a natural landscape when the cultural connotation was not stressed. With cultural landscape added, a complete morphology of landscape was formed [80], which shaped tourists’ first impression of landscapes in a district. Tourism resources were divided into eight categories: geological landscape, water scenery, biological landscape, meteorological and climatological landscape, relics and ruins, buildings and facilities, tourism commodities, and cultural activities [85], with the first four categories being the natural landscape, and the last four the cultural landscape.

Tourism infrastructure (A2): As this paper focused on cultural tourism attractiveness, the original criterion “infrastructure” was renamed “tourism infrastructure”, which included tourist-oriented tourism facilities and resident-oriented living facilities. Sunitha held that tourism infrastructure had four aspects: attractions, accommodation, accessibility, and amenities [86]. Charles E. Gearing mentioned recreational and shopping facilities as well as infrastructure, food, and shelter [87], while Krešić and Prebežac mentioned accommodation and catering facilities [58]. Considering that the terms “recreational and shopping facilities” and “accommodation and catering facilities” were the respective supersets of attractions and accommodation, the term “recreational and shopping facilities” was used to replace “attractions infrastructure”, with “accommodation and catering facilities” replacing “accommodation infrastructure”. To maintain consistency of terminology, this paper uses “infrastructure” at the criteria level and “facility” at the content level.

Image elements of the district (A3): While the original criterion “building environment” only determined whether the various architectural spaces exist or not, “image elements of the district” pointed to the emotional attachment to the physical environment after developing a better acquaintance and understanding of the district. Urban image elements, e.g., paths, districts, nodes, landmarks, and edges, were the most interesting and impressive elements in a city [81]. Such image elements were also applicable to historic districts. As the word “district” was used as one of the urban image elements as well as in the term “historic district”, to be more specific, the word “blocks” with a smaller scope was used for this criterion. In addition, the overall presentation of any physical environment was a combination of different sensory perceptions, including visual, tactile, olfactory, and kinesthetic [82]. Cultural tourism in historic districts refers to the visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory, and olfactory perceptions of tourists. Therefore, compared to urban image elements, the image elements of a district here seem to add a human touch.

Cultural and Natural Environments

Since the cultural environment has both tangible and intangible qualities [73], cultural heritage can similarly be divided into tangible and heritage with the natural environment bearing physical characteristics (refer to the natural heritage) [18,83]. Hence, the four original criteria can be re-organized into tangible and intangible cultural resources. According to the experts’ suggestions, cultural resources in districts were divided into two types: those with legal identities related to cultural heritage conservation and those without such legal identities. The connotation referred to the corresponding values of “cultural and natural heritage” and “intangible cultural heritage” [83,88], and the forms were summarized from the three classifications of product technology innovation [89].

Tangible cultural resources (B1): Considering that there were both cultural relics and non-cultural relics in historic districts, and cultural heritage was divided into monuments, groups of buildings, and sites [84], these three types of heritage were integrated with movable cultural relics, immovable cultural relics, and related traditional artifacts and places, and their names modified or their meanings expanded [76,77]. Hence, the artifacts, buildings, and cultural and social fields can be derived. Apart from cultural heritage, world heritage also includes natural heritage, mixed cultural and natural heritage, and cultural landscapes (a special category) [83], which jointly contribute to the landscape features.

Intangible cultural resources (B2): The contents of this criterion were derived mainly by integrating the actual situation of districts and the relevant references (including the classification of intangible cultural heritage and the presentation of intangible culture). “Narratives and memories” was a combination of the UNESCO and Taiwanese definitions of oral traditions [88,90]; “ Cultural activities” was a combination of traditional performing arts, performing arts, rituals, and festive events [88,90]; “Industrial culture activities” was a combined presentation of the cultural and creative industries and the traditional industries [91,92]; “Characteristic cultural manifestations” were the combination of various traditional cultural manifestations, traditional craftsmanship, folklore, traditional knowledge and practices, oral expressions—including language as a vehicle for intangible cultural heritage, social practices, traditional craftsmanship, and knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe [77,88,90]; “Residents’ images” was a combination of resident’s participation, preservation awareness, residents’ consensus, and a manifestation of values [93,94]; “District services” was a combination of the contents related to tourism and public services [95,96].

4.2.3. The Amended Framework

Following the first round of semi-structured questionnaires and interviews, a framework as shown in Table 5 and Table 6, was proposed after consolidating the expert inputs.

Table 5.

Description of revised framework aspects.

Table 5.

Description of revised framework aspects.

| Aspects | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| A Physical environment | a. The hardware environment allows historic districts to develop attractive cultural tourism and to emphasize denotation-based attractiveness. b. This aspect includes three criteria: morphology of landscape, tourism infrastructure, and image elements of the district. | [5,72,73,74] |

| B Cultural and natural environment | a. This aspect is the software environment where historic districts develop cultural tourism attractiveness and emphasize the connotation-based attractiveness. b. It includes two criteria: tangible and intangible cultural resources shaped in the context of traditional culture and those shaped in the context of innovative culture. c. Tangible and intangible cultural resources can be divided into two types: those with legal identities related to cultural heritage conservation and those without such legal identities. Their connotation is the value in conservation, history, art, science, aesthetics, folklore, ethnography, anthropology, etc. | [5,18,72,73,74,83,88,89] |

Table 6.

Description of the revised framework criteria.

Table 6.

Description of the revised framework criteria.

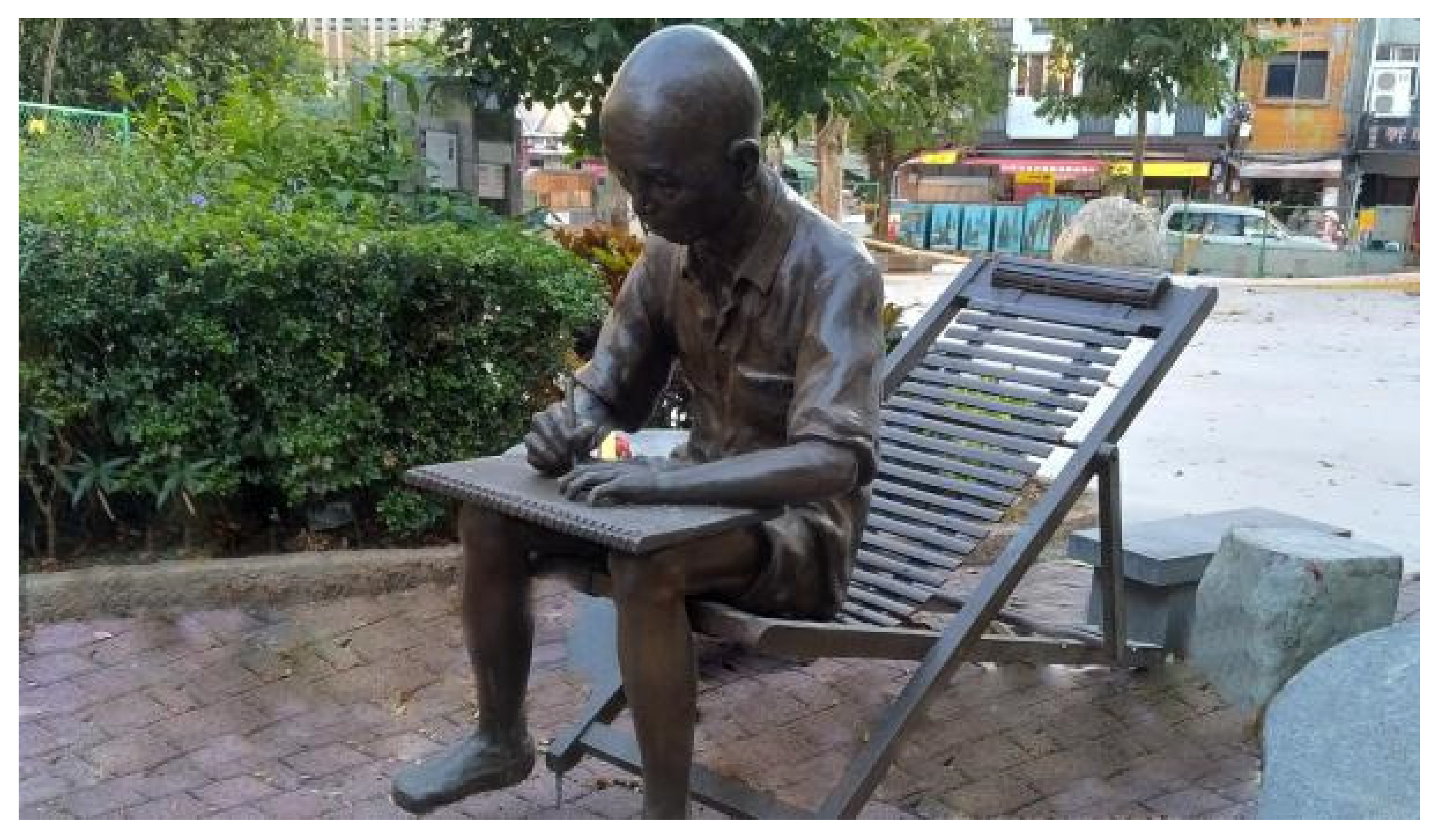

| Description of the Revised Framework Criteria | Description of the Revised Framework Criteria in the Case Study of the Dadaocheng Historic District | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Definition | Items | Landscapes | Description |

| A1 Morphology of Landscape: Landscape of the district that can be directly captured by people in or outside the district. It contains the following two items [75,80,85]. | A1-1 Natural Landscape: A landscape composed of different forms of natural features, including geological landscape, water scenery, biological landscape, and the meteorological and climatological landscape. | Trees down the street of Sec. 1, Dihua St. |  | This is a biological landscape |

| A1-2 Cultural Landscape: Scenic landscape formed under the long-term influence of human activities on the natural environment, including relics and ruins, buildings and facilities, tourism commodities, and cultural activities. | Diversified commodities in the Art Yard. |  | This is a tourist commodity landscape | |

| A2 Tourism Infrastructures: Tourism infrastructure refers not only to the material conditions created for the tourism industry, but also the public utilities and facilities of modern life shared by residents and tourists, which cover the following four segments [58,75,86,87]. | A2-1 Recreational and Shopping Facilities: the collective term for a wide range of tourism, leisure and shopping facilities, such as the scenic spot itself (including a viewing deck or viewing area), its auxiliary facilities, including sports, shopping, and entertainment facilities. | Double 8—Rock Climbing Center. |  | This is a sports facility |

| A2-2 Accommodation and Catering Facilities refer to the various facilities that provide accommodation and catering for tourists, such as hotels, inns, camps, restaurants, breakfast shops, etc. | The Carp—Specialty restaurant. |  | This is a catering facility | |

| A2-3 Accessibility Facilities are the various transportation facilities that bring tourists to the district, such as vehicles, roads, ships, etc. | Public bicycle rental system in front of the Dadaocheng Theatre. |  | This is an accessibility facility | |

| A2-4 Amenity Facilities: a series of infrastructures to support life in the neighborhood and provide convenience for tourists, such as home facilities, public facilities, communication facilities, and security facilities. | Visitor Information Center. |  | This is a public service facility | |

| A3 Image elements of the district: Image elements of the district refer to the interesting and impressive elements located in the district that can be perceived by people after becoming familiar with the environment. These elements are recognizable and constitute an important part of the district space cognition. They cover the following five segments [75,81,82]. | A3-1 Paths refer to the identifiable, continuous and directional street network in a historic district. They are usually roads with defensive, life, sacrificial, leisure, fengshui and other image features or functions; | The long main street—Dihua St. |  | This is an identifiable element |

| A3-2 Blocks: the contents in blocks establish different continuity features according to the different themes. Themes are usually related to the division of blocks, such as ancient place names, district functions, administrative management, topographical features, street nodes, architectural styles, residents’ ancestral homes, and marriage relations. | The area with most Chinese medicine shops in Dihua St. |  | This is a characteristic element of specialist product sales | |

| A3-3 Nodes refer to the junctions of traffic routes or the gathering points for district activities. A node is usually a public social or cultural space, such as the space formed by intersecting roads. It can also be a gathering point or an area enclosed by buildings and their auxiliary spaces, such as parks, rings, temples and ancestral halls as well as their auxiliary spaces, and famous ancient trees and their auxiliary spaces. | Traffic node between Dihua St. and Minsheng West Road. |  | This is a junction node of traffic routes | |

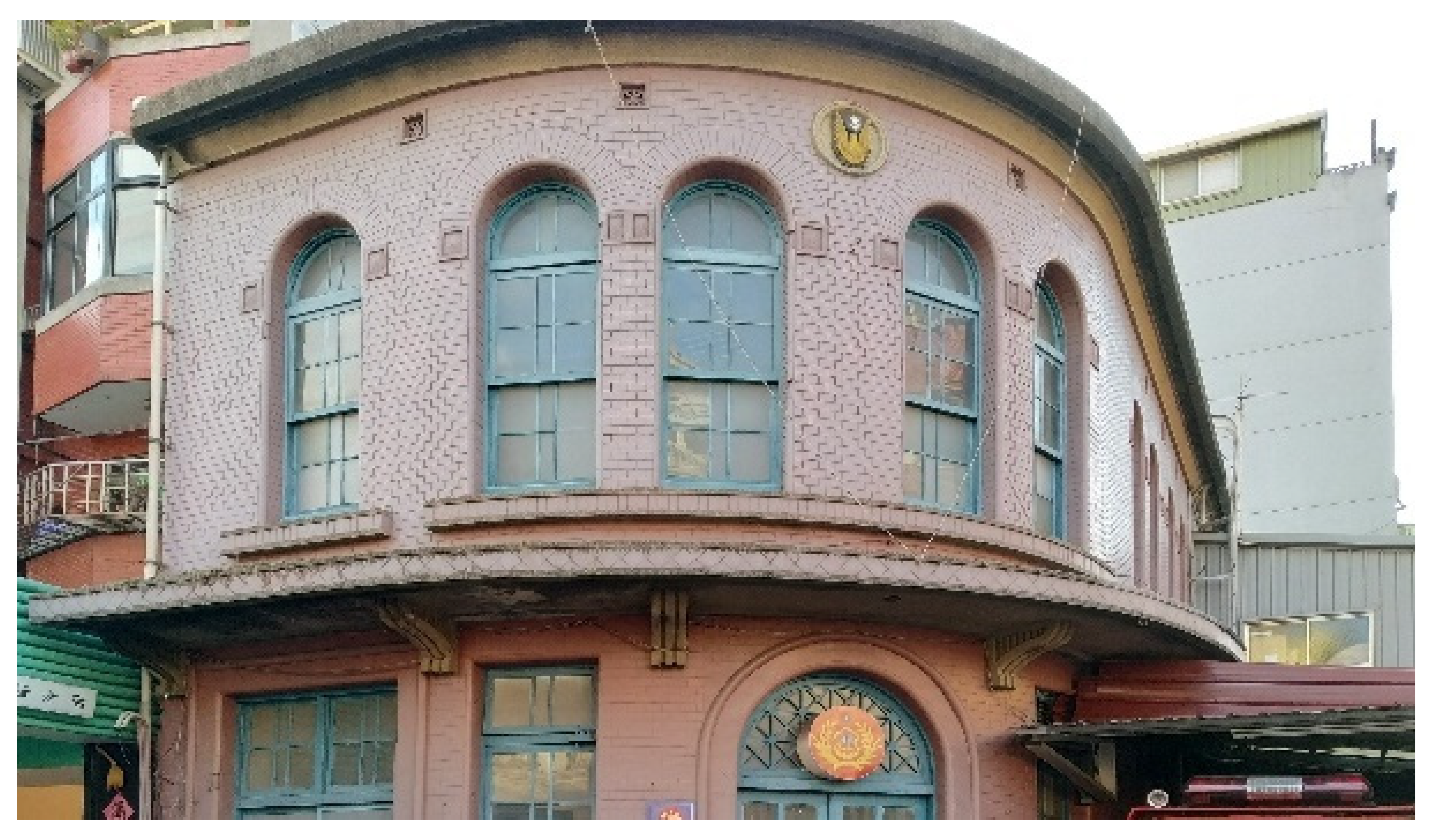

| A3-4 Landmarks are buildings or natural objects in a district with high popularity which are highly representative or commemorative, such as temples, ruins, monuments, and department stores. | Reservist Counseling Centre of the Datong District. |  | This is a representative architectural element | |

| A3-5 Edges refer to the boundary that separates the district from the surroundings. Edges are normally visible and continuous; they can be roads or boundary signs, or mountains, waters, bridges, walls, plants, archways, and temples. | Taipei Bridge. |  | It is a boundary element. | |

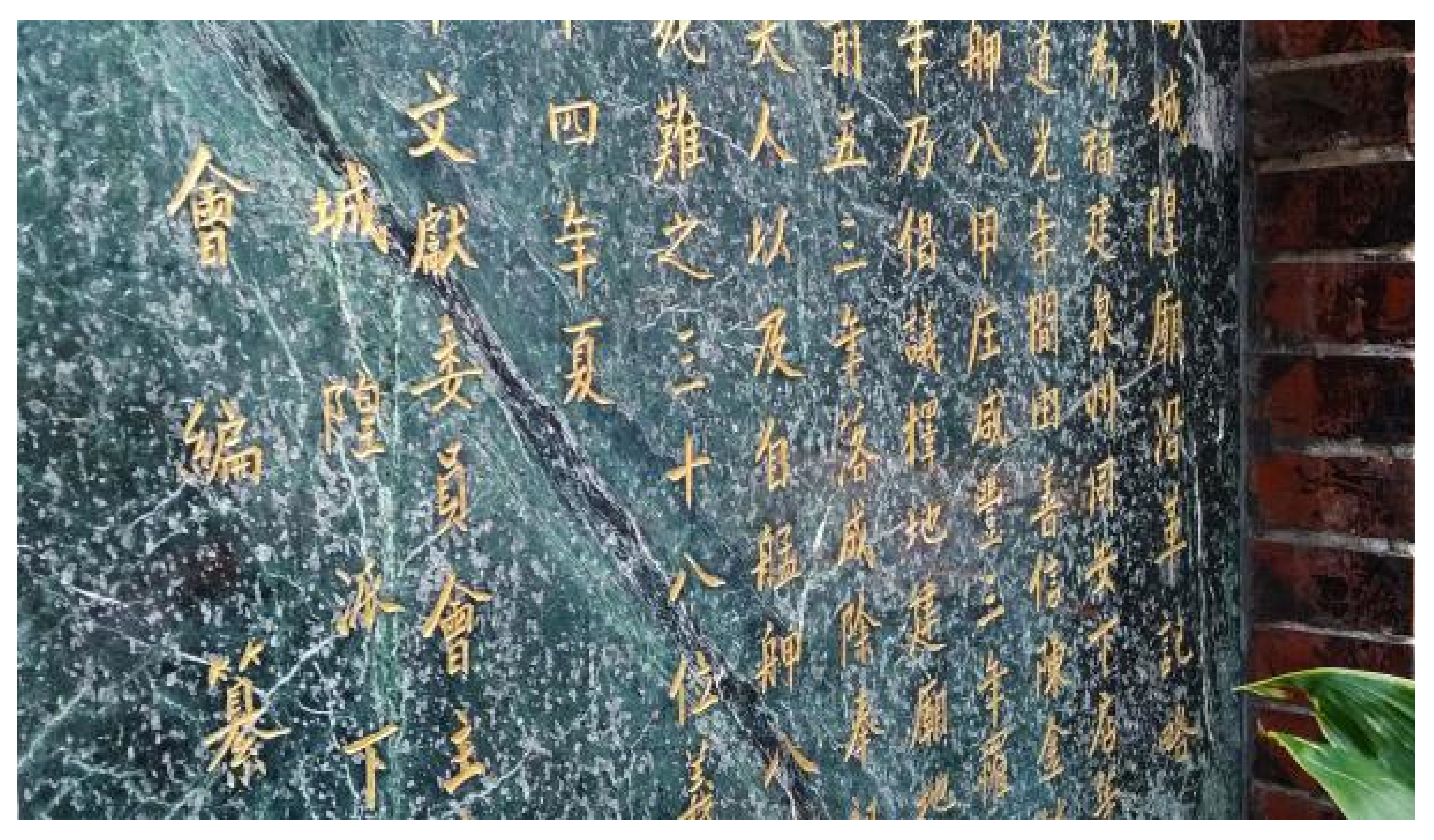

| B1 Tangible cultural resources: Tangible cultural resources: the values, characteristics or significance demonstrated by the tangible cultural resources in the district, which cover the following four segments [76,77,83,84]. | B1-1 Artifacts: human-made artifacts other than buildings and spaces, such as inscriptions, sculptures, books, calligraphy, paintings, and items that are connected to celebrities. | Inscriptions in the Xia-Hai City God Temple. |  | This is a stone inscription that demonstrates cultural connotations |

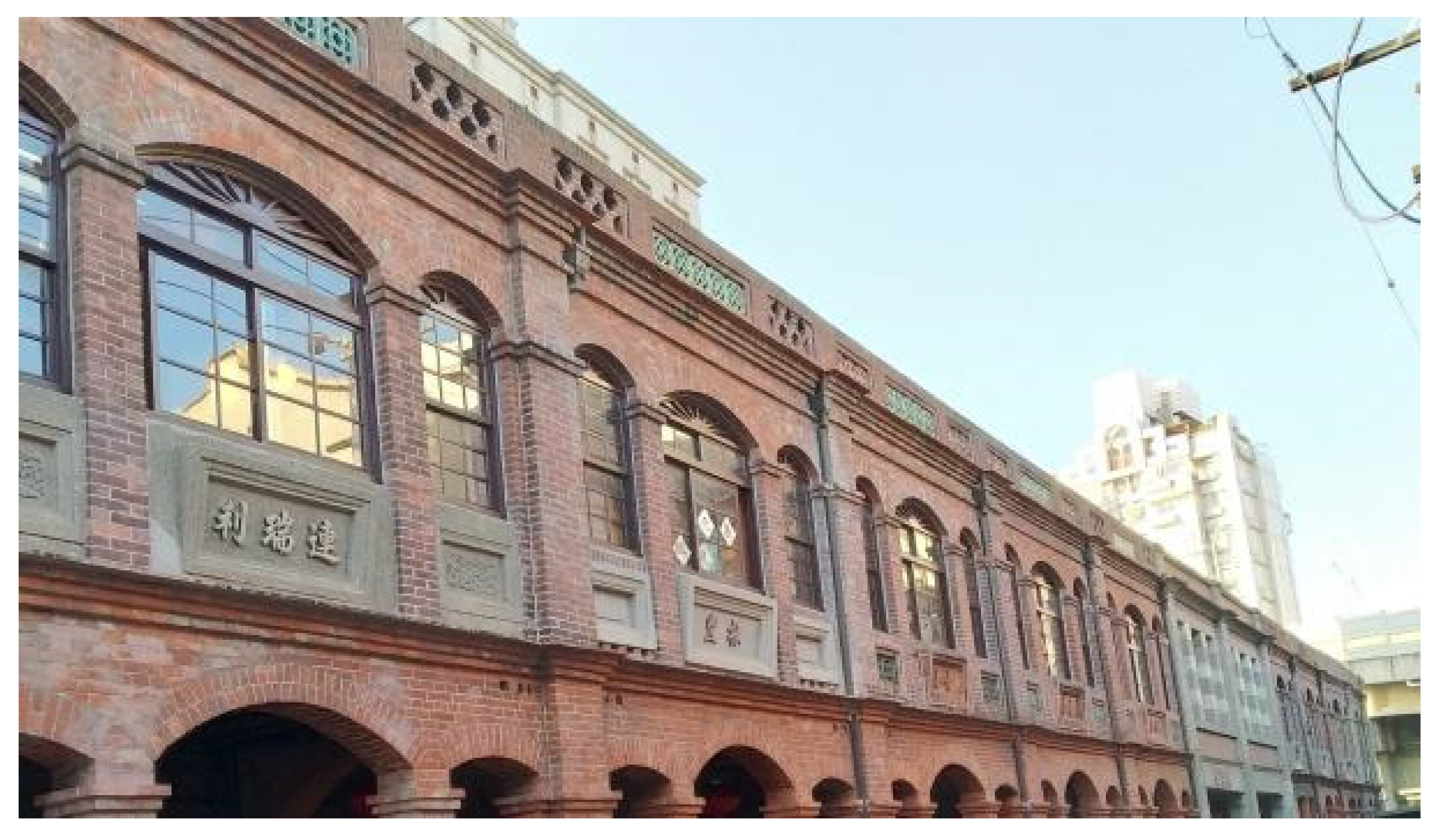

| B1-2 Buildings: a single building or a group of buildings, such as architectural patterns, styles, materials, and buildings that are connected to celebrities. | Ten Joined Townhouses. |  | This is a group of buildings that demonstrates cultural connotations. | |

| B1-3 Cultural and Social Fields are fields (including those existing in the past, those that still exist today, and those newly emerging) that provide spaces for regular or irregular cultural or social activities, such as cultural and social spaces that carry various intangible cultural resources, archaeological sites, and fields that are connected to celebrities. | The former site of Yung-le-tso the former theater. |  | This is a cultural field group that demonstrates cultural connotations. | |

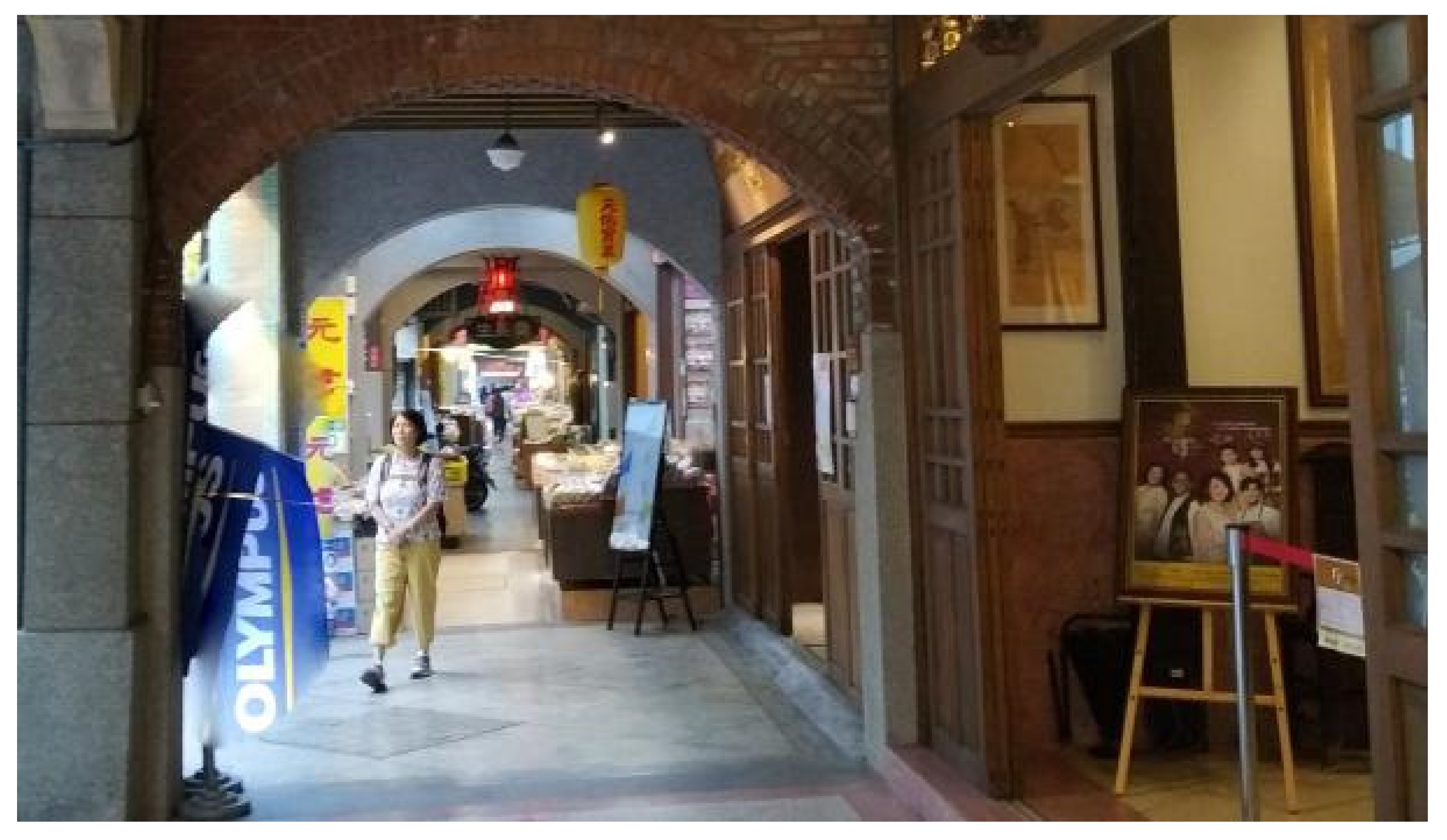

| B1-4 Landscape Features refers to connotations demonstrated by natural or cultural landscapes, such as natural areas, special topography, geological phenomena, rare minerals, plants, animals, and landscape formed under the long-term interactions between humans and nature. | Qilou passages in Dihua St. |  | This is a cultural landscape that demonstrates cultural connotations. | |

| B2 Intangible cultural resources: Intangible cultural resources refers to the values, characteristics or significance demonstrated by the intangible cultural resources in a district, which are usually behaviors or manifestations of special or important significance to the inheritance of traditional culture or the fusion of old and new cultures in the district. The activity-related content can be divided into the following types: non-governmental, governmental, and jointly run. Intangible cultural resources include six segments as follows [77,88,90,91,92,93,94,95,96]. | B2-1 Narratives and memories refer to the stories told by residents in the district. The types of stories include historic tales, historic events, myths, legends, and fables. | Stories about the musician Li Lim-Chhiu. |  | It is a historic stories that demonstrates the cultural connotations. |

| B2-2 Cultural activities reference the various performances or folklore activities held to pass on or illustrate the district culture, such as dramas, rituals, and theme performances. | God Folk Festival. |  | This is a folk activity that demonstrates cultural connotations. | |

| B2-3 Industrial culture activities reference the various industrial activities held to pass on or illustrate industries in the district, such as traditional industrial shows, traditional industry innovation competitions, industrial experience activities, and cultural and creative product activities. | Harvest Festival activities. |  | An industrial culture activity for inheritance and innovation that demonstrates cultural connotations. | |

| B2-4 Characteristic cultural manifestations refer to the various concrete or abstract cultural manifestations that have been passed on by residents from generation to generation, are generally accepted by residents, or are closely related to the life of residents, such as language, writing, food, music, dance, technology, knowledge, management, festivals, local beliefs, lifestyle, and social networks. | Traditional tailoring techniques. |  | This is traditional craftsmanship that demonstrates cultural connotations. | |

| B2-5 Residents’ images refer to the collective image of residents when participating in political, economic, and cultural activities, such as district identity, service awareness, cultural conservation awareness, environmental protection awareness, spiritual features, friendliness, social inclusiveness, residents’ consensus, social participation, and social values. | The pride of residents. |  | This demonstrates a district identity with cultural connotations. | |

| B2-6 Service refers to the various services to address the parallel needs of residents and tourists, such as a tourism information service, tourism public security service, tourism social service functions, a tourism environment service, tourism elements assurance service, tourism commercial service, and domestic services for residents. | Traditional costume experience. |  | This demonstrates the cultural connotation of a tourism commercial service | |

4.2.4. The Modified Delphi Decision-Making Results

After seventeen experts rated the hierarchical framework, the following results were obtained (refer to Table 7).

Table 7.

Necessity of Criteria Rating Statistics (Data source: organized in this research).

As can be seen, all five criteria had a QD of 0.5, which was less than 0.6, indicating that a high consensus was reached. Such a consensus was reached at the first scoring in Round 2 for two reasons: adequate communication between the author and the experts and the use of few criteria. In other words, the amended hierarchical framework of cultural tourism attractiveness for Chinese historic districts was the final one.

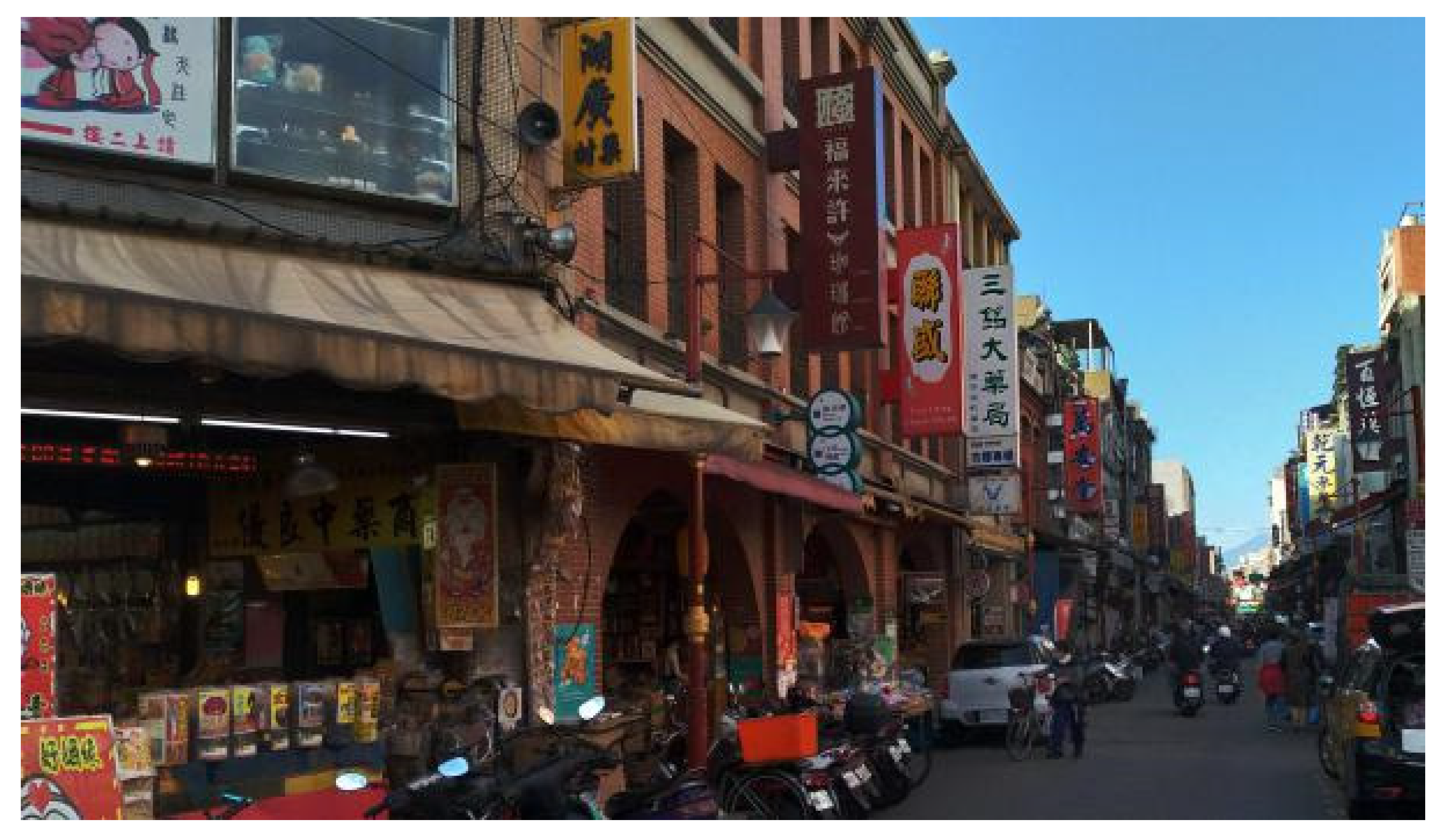

5. Case Study

Located in the old city of Taipei, the Dadaocheng Historic District is a Chinese historic district popular with tourists where the culture and landscape have been relatively well preserved, the cultural and creative industries and the district rejuvenation have been closely integrated. In particular, Dihua Street is the highlight of the district and an ideal destination for cultural tourists. Therefore, the Dadaocheng Historic District was chosen as a typical case for studying the cultural tourism attractiveness of Chinese historic districts.

The author took the contents in the hierarchical framework of tourism attractiveness for Chinese historic districts as the basis for observation in the Dadaocheng Historic District and obtained the following results (refer to Table 6).

As shown in Table 6, the landscapes in the pictures correspond to the physical environment and the cultural and natural environment of the Dadaocheng Historic District. Therefore, each picture represents a landscape and corresponds to a content of the framework. There are many specific manifestations of each landscape, and photos are just one of them. And each landscape has many specific forms of expression, and the landscape in each photo is just one of them. Take the public bicycle rental system in front of the Dadaocheng Theatre as an example. It is just one of the accessibility facilities in the Dadaocheng Historic District. The landscapes formed by the MRT (Mass Rapid Transit) system and the public bus system also belong to landscapes of accessibility facilities.

It can be seen that many landscapes are directly related to tourism. Therefore, tourism development has a significant impact on the landscape of the tourist destination [97]. In brief, through the specific case analysis of the Dadaocheng historic district, the basic method of applying the hierarchical framework has been introduced. Of course, every landscape is only one of the specific manifestations of related contents in the hierarchical framework, and districts have different actual situations, the same content in different historic streets may correspond to different landscapes.

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

This section consists of two parts: conclusions and suggestions. The former covers the origin of the research, research findings, research contributions, and the limitations of this research; the latter makes proposals for follow-up research to address the above limitations.

6.1. Conclusions

Chinese are located in almost every continent of the world. As long as it is a place where there are Chinese people, it usually forms a district with Chinese characteristics. As an important part of the Chinese cultural heritage, Chinese historic districts showcase the history and culture of the Chinese, and attract many tourists. How to balance the relationship between landscape conservation and tourism development, and how to demonstrate the value of heritage in the sustainable development perspective, is a problem worthy of much thought. This is also the reason why this paper selects Chinese historic districts as the research object.

This paper takes expert interviews and structural observation as the research method to explore the cultural tourism attractiveness of Chinese historic districts and comes up with two findings. First, the redefinition of a Chinese Historic District is made by combining the two concepts of Chinese district and historic district, and the redefinition of cultural tourism attractiveness is made by combining the two concepts of cultural tourism and tourism attractiveness. The former is a space formed by one or more main streets and subsidiary alleys and lanes, including those with legal identities related to cultural heritage conservation and those without such legal identities. The difference between Chinese historic districts and non-Chinese historic districts lies in their different geographical locations: that is, Chinese historic districts generally exist in mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan as well as overseas Chinatowns; in essence, different cultural styles contribute to the difference. Chinese historic districts are distinguished by the congregated settlement of Chinese, the numerous Chinese-style buildings, Chinese signs, and Chinese restaurants along with the strong atmosphere of Chinese folk customs and festivals, which manifest the “distinctive characteristics of Chinese culture”. The latter is different from the general tourism attractiveness. Cultural tourism attractiveness is developed under the joint action of tourists’ cultural motivation and the cultural resources in the tourist destination. Culture is the bridge that connects the two, and it is also the source and core of cultural tourism attractiveness. Second, a hierarchical framework of cultural tourism attractiveness for Chinese historic districts is produced, which takes the physical environment and the cultural and natural environments as the aspects and the morphology of landscape, tourism infrastructure, image elements of the district, and tangible and intangible cultural resources as the criteria, and 21 elements including natural landscape and cultural landscape as the contents. Reflecting on the prototype framework, the reason for the deletion for the aspect of marketing strategy is likely to be that tourism attractiveness added with an external force such as promotion and marketing is extra tourism attractiveness: that is, the cultural tourism attractiveness referred to the direct relationship between the tourism resources in the districts and the cultural needs of tourists. The biggest difference between this framework and a general tourism attractiveness framework is that it not only makes the cultural position more prominent, but more importantly, it considers issues from the perspective of tourism development whilst standing for sustainable development. Therefore, it has well balanced the relationship between tourism development and landscape conservation, and fully considered the interests of the four main participants in the development of districts, including cultural and historic practitioners, district delegates, tourism practitioners, and planning and operating personnel. At the same time, the framework provides a list of initial elements for the observation, understanding, and evaluation of the cultural tourism attractiveness of Chinese historic districts under the premise of landscape conservation.

The contributions of this research are mainly reflected in two areas. In theory, the redefinitions of “Chinese historic district” and “cultural tourism attractiveness” help to clarify the scope and meaning of the two terms, while the establishment of the hierarchical framework outlines the components of cultural tourism attractiveness for Chinese historic districts in a systematic way. In practice, this framework provides a theoretical reference for the coordinated development of the economy and culture when authorities at different levels are making plans to improve cultural tourism attractiveness and to support the landscape conservation of Chinese historic districts.

Subject to the constraints of the research approach, research method, and reference data, this research has the following two limitations: first, the interactions among the criteria of cultural tourism attractiveness as applied to the Dadaocheng Historic District and the source of the interactions are not identified; second, the importance and performance of the various criteria of the Dadaocheng Historic District have not been obtained.

6.2. Suggestions

In order to further improve the researchers on this topic and provide follow-up researches with clearer thoughts and references, this paper makes the following suggestions:

- A.

- Explore the interactions among the criteria of this hierarchical framework in specific Chinese historic districts, find out the source of the interactions, and plot a causal diagram;

- B.

- Analyze the importance and performance of each criterion of this hierarchical framework in specific Chinese historic districts, and plot an Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) diagram.

Author Contributions

H.L. conceived and designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; B.-S.C. developed the theoretical formalism, supervised the project, and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chang-Chan Huang, Cheng-Ping Wang, Cheng-Wei Lin, Chun-Ta Huang, Feng Ching, Huei-Chen Lee, Jen-Hao Chang, Jing-Shoung Hou, Jing-Yuan Chen, Kuo-Hua Yu, Lan Duo, Ellen Chang, Man-Ching Peng, Min-Chin Chiang, Ru-Hwa Chiu, Shan-Lin Huang, Shih-Chuan Huang, Spencer Pai, Sunny Sun, Wei-Kuang Liu, Wei-Ting Hsu, Xin Wen, Yanfeng He, Yi-Chung Hu, Yi-Lun Tsai for their useful comments and suggestions, which have certainly improved this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Prieto, I.; Izkara, J.L.; Béjar, R. Web-Based tool for the sustainable refurbishment in historic districts based on 3d city model. In Advances in 3D Geoinformation; Alias, A.R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Veirier, L. Historic Districts for All: A Social and Human Approach for Sustainable Revitalization; Manual for City Professionals; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 2008; pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, W.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.; Kwon, Y. Transforming Housing to Commercial Use: A Case Study on Commercial Gentrification in Yeon-nam District, Seoul. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, L. The Conservation of China’s Historical Sites under Rapid Urbanization in the Case of Xixing District. Resourceedings 2019, 2, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. 2011. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- UNESCO. The UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape Implementation by Member States. 2019. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- C.I.A.M. The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Ginting, N.; Rahman, N.V. Preserve urban heritage district based on place identity. Asian J. Environ. Behav. Stud. 2016, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Nocca, F.; Girard, L.F. Towards an integrated evaluation approach for cultural urban landscape conservation/regeneration. Region 2018, 5, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Wan, L.; Wu, B. Qualitative Analysis of Residents′ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts on Historic Districts: A Case Study of Nanluoguxiang in Beijing, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2017, 16, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Parra, I.; Jover, J. Overtourism, place alienation and the right to the city: Insights from the historic centre of Seville, Spain. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, W.; Czalczynska-Podolska, M. Assessing Architecture-and-Landscape Integration as a Basis for Evaluating the Impact of Construction Projects on the Cultural Landscape of Tourist Seaside Resorts. Land 2021, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, G.R. The Cultural Heritage-Oriented Approach to Economic Development in the Philippines: A Comparative Study of Vigan, Ilocos Sur and Escolta, Manila. In Proceedings of the 10th DLSU Arts Congress, Arts and Culture Heritage, Practices and Futures, Manila, Philippines, 16 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Y.L. Seeking Serious Tourists–Balancing Culture, Conservation and Economic Gains from Aboriginal Tourism. In Proceedings of the 2009 Ttra International Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–24 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Du Cros, H.; McKercher, B. Cultural Tourism, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt, R.A.; Rogers, P.R. Hoi an Protocols for Best Conservation Practice in Asia: Professional Guidelines for Assuring and Preserving the Authenticity of Heritage Sites in the Context of the Cultures of Asia. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000182617 (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- ICOMOS. International Cultural Tourism Charter, Managing Tourism at Places of Heritage Significance. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/tourism_e.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- ICOMOS. The Seoul Declaration on Tourism in Asia’s Historic Towns and Areas. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/xian2005/seoul-declaration.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- UNWTO and UNESCO. Siem Reap Declaration on Tourism and Culture—Building a New Partnership Model. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/abs/10.18111/unwtodeclarations.2015.24.01 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- UNWTO and UNESCO. Muscat Declaration on Tourism and Culture: Fostering Sustainable Development UNWTO Declarations. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/abs/10.18111/unwtodeclarations.2017.26.05 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- UNWTO and UNESCO. Istanbul Declaration on Tourism and Culture: For the Benefit of All. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/abs/10.18111/unwtodeclarations.2018.27.02 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- UNWTO and UNESCO. Kyoto Declaration on Tourism and Culture: Investing in Future Generations. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/abs/10.18111/unwtodeclarations.2019.28.04 (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Wise, N.; Jimura, T. Changing Spaces in Historical Places. In Tourism, Cultural Heritage and Urban Regeneration; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.W. Sustainable development of heritage conservation and tourism: A Hong Kong case study on colonial heritage. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.X.; He, W.L. The Relationship of Tourism Motivation, Perceived Value and Destination Loyalt—A Case of Macao Cultural Heritage. Stud. Hong Kong Macao 2015, 2, 20–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.M.; Xu, H.G.; Bao, J.G. Preservation and Renewal of Historical and Cultural Blocks in Cities of Foreign Countries. Mod. Urban Res. 2005, 11, 13–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Y.J.; Lee, W.; Wu, L.Y. A Study on Relationship among Tourism Image, Tourism Experience and Behavioral Intentions-A Case Study for Sinhua Old Street. J. Leis. Tour. Sport Health 2013, 3, 151–173. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.C. The Tourism Development Model of Historic and Cultural Districts in under the Urbanization Background. Soc. Sci. 2020, 5, 14–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Implementation of the UNESCO Historic Urban Landscape. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/ (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Wang, S.; Gu, K. Pingyao: The historic urban landscape and planning for heritage-led urban changes. Cities 2020, 97, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, H.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S. Conservation for sustainable development: The sustainability evaluation of the xijie historic district, Dujiangyan City, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.D. A Literature Review of Historic District Conservation in China. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Conference of China City Planning (The Conservation of Urban Cultural Heritages), Beijing, China, 24 November 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.D. A Literature Review and Enlightenments of Conservation and Exploitation for Foreign Historic Districts. China Constr. 2013, 10, 70–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. A Review of the Research on Historic Conservation Area Protection in China. Archit. Cult. 2016, 9, 78–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Miao, B.B. A Literature Review of Sustainable Development of Historic Districts in China. City House 2019, 7, 195–196. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Chen, X.J. Review and Reflection on the Research about Tourism Development of Historical Blocks in China. Tour. Hosp. Prospect. 2018, 2, 54–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.M. World-Famous Chinese Districts: Chinatowns; Jilin People’s Press: Changchun, China, 2009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Regulation on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2008-04/29/content_957280.htm (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Tainan City Government. Tainan City Self-Government Ordinance for the Revitalization of Historic Street Districts. Available online: http://law01.tainan.gov.tw/glrsnewsout/NewsContent.aspx?id=224 (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Boivin, M.; Tanguay, G.A. Analysis of the determinants of urban tourism attractiveness: The case of Québec City and Bordeaux. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Butler, R.J.; Zhang, C. Evaluation of public perceptions of authenticity of urban heritage under the conservation paradigm of Historic Urban Landscape—A case study of the Five Avenues Historic District in Tianjin, China. J. Archit. Conserv. 2019, 25, 228–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.M.; Liu, M.Z. Applying Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Model to Historical District Conservation Research. Planners 2008, 24, 72–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.T. Chinese Communities in the Far East of Russia from 1891 to 1900. Master’s Thesis, Heilongjiang University, Haerbin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas. Available online: http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.phpURL_ID=13133&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- ICOMOS. The Hoi an Declaration on Conservation of Historic Districts of Asia. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/xian2005/hoi-an-declaration.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- ICOMOS. Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas (The Washington Charter). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/towns_e.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Richards, G. Cultural Tourism in Europe; Cab International: Wallingford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Tourism and Culture. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-and-culture (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- EU and COE Cultural Tourism in the EU Macro-Regions: Cultural Routes to Increase the Attractiveness of Remote Destinations. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/routes4u-manual-attractiveness-remote-destination-cultural-tourism/16809ef75a%0A%0A (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Middleton, V.T. Marketing implications for attractions. Tour. Manag. 1989, 10, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ritchie, J.B. Measuring destination attractiveness: A contextual approach. J. Travel Res. 1993, 32, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, C.A. Tourism Planning: Basics, Concepts, Cases, 3rd ed.; Taylor and Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Lee, C.K. Push and pull relationships. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatu, C.; Bulai, M. A critical analysis on the evaluation of tourism attractiveness in Romania. Case study: The region of Moldavia. In Proceedings of the 5th WSEAS International Conference on Economy and Management Transformation, Timisoara, Romania, 23–26 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vetrova, E.A.; Kabanova, E.E.E.; Nakhratova, E.E.; Baynova, M.S.; Evstratova, T.A. Project management in the sphere of tourism (using the example of Taganrog). Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vengesayi, S.; Mavondo, F.T.; Reisinger, Y. Tourism destination attractiveness: Attractions, facilities, and people as predictors. Tour. Anal. 2009, 14, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krešić, D.; Prebežac, D. Index of destination attractiveness as a tool for destination attractiveness assessment. Turiz. Međunarodni Znan. Stručni Časopis 2011, 59, 497–517. [Google Scholar]

- Giambona, F.; Grassini, L. Tourism attractiveness in Italy: Regional empirical evidence using a pairwise comparisons modelling approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murry, J.W., Jr.; Hammons, J.O. Delphi: A versatile methodology for conducting qualitative research. Rev. High. Educ. 1995, 18, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, A.; Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Cui, T.; Song, T.; Ouyang, Z. Evaluation of prioritized natural landscape conservation areas for national park planning in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlami, V.; Zogaris, S.; Djuma, H.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Kehayias, G.; Dimopoulos, P. A field method for landscape conservation surveying: The landscape assessment protocol (LAP). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, S.L.T.; Mc Neil, B.J.; Peterson, L.E.; Palmer, R.H. Eliciting expert opinion using the Delphi technique: Identifying performance indicators for cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 1998, 10, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoff, M.; Linstone, H.A. The Delphi Method-Techniques and Applications; Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, I.; Mac Donald, A.; Wright, G.; Hamlin, I. Improving the practical application of the Delphi method in group-based judgment: A six-step prescription for a well-founded and defensible process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 147, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, C.M. The Delphi technique: A critique. J. Adv. Nurs. 1987, 12, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M.C.; Wedman, J.F. Future issues of computer-mediated communication: The results of a Delphi study. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 1993, 41, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.K.; Tsai, S.C.; Lin, P.C.; Chu, K.C.; Chen, A.N. Toward a New Real-Time Approach for Group Consensus: A Usability Analysis of Synchronous Delphi System. Group Decis. Negot. 2020, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Faherty, V. Continuing social work education: Results of a Delphi survey. J. Educ. Soc. Work 1979, 15, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydberg, A.; Ericson, B.; Lindstedt, E. Use of a structured observation to evaluate visual behavior in young children. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2004, 89, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.T. The Silent Language; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. New Life for Historic Cities: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach Explained. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/727/ (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Arnauld, A.; Nicole, P. La Logique de Port-Royal; Hachette Livre: Paris, France, 1868. [Google Scholar]

- Physical Environment. Available online: http://socialreport.msd.govt.nz/2003/physical-environment/physical-environment.shtml (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (2017 Amendment). Available online: http://www.scio.gov.cn/xwfbh/xwbfbh/wqfbh/37601/38374/xgzc38380/Document/1630060/1630060.htm (accessed on 25 August 2020). (In Chinese)

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Intangible Cultural Heritage Law of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/flfg/2011-02/25/content_1857449.htm (accessed on 9 September 2020). (In Chinese)

- Fletcher, J.; Fyall, A.; Gilbert, D.; Wanhill, S. Tourism: Principles and Practice; Pearson: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, E.J.; Shapiro, S.J.; Perreault, W.D. Basic Marketing; Irwin-Dorsey: Ontario, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C. The morphology of landscape. In the Cultural Geography Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1960; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, R.M.; Stea, D. Cognitive maps and spatial behavior: Process and products. In Image and Environment: Cognitive Mapping and Spatial Behavior; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1973; pp. 8–26. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- National Standards of the People’s Republic of China: Classification, Investigation and Evaluation of Tourism Resources. Available online: https://net.fafu.edu.cn/zgslgy/c6/70/c5616a116336/page.htm (accessed on 9 September 2020). (In Chinese).

- Kavunkil Haneef, S. A Model to Explore the Impact of Tourism Infrastructure on Destination Image for Effective Tourism Marketing; University of Salford: Salford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gearing, C.E.; Swart, W.W.; Var, T. Establishing a measure of touristic attractiveness. J. Travel Res. 1974, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000132540 (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Coombs, R.; Narandren, P.; Richards, A. A literature-based innovation output indicator. Res. Policy 1996, 25, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Executive Yuan of the Republic of China. Cultural Heritage Preservation Act. Available online: https://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=H0170001 (accessed on 9 September 2020). (In Chinese)

- Jia, X. Research on the Culturalization of Traditional Industry in Gongjing District under the Background of Industrial Transformation. Open Access Libr. J. 2020, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.L.; Jiang, N. A Study on Tourist Satisfaction with the Cultural and Creative Industry in Historic Districts. J. Yangzhou Univ. 2016, 20, 60–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Harper, R.E. The Role of Citizen Awareness in the American Historic Preservation Movement. Rad. Inst. Povij. Umjet. 1996, 20, 184–187. [Google Scholar]

- Montealegre, M.G. Solutions for the Sustainable Management of a Cultural Landscape in Danger: Mar Menor, Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Xie, L.S.; Guan, X.H. Scale Development and Validation of Tourism Public Service Quality. Tour. Trib. 2016, 31, 117–127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Gan, Q.L.; Liu, W.B. Tourism Public Services System: An Exploration of the Theoretical Framework. J. Beijing Int. Stud. Univ. 2010, 5, 8–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bal, W.; Czalczynska-Podolska, M. The Stages of the Cultural Landscape Transformation of Seaside Resorts in Poland against the Background of the Evolving Nature of Tourism. Land 2020, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).