Protection and Revealing of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool for Sustainable Development: The Case of Kythera Island in Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. Cultural Heritage Protection: Traditional Settlements

2.2. Sustainable Development and Management of Cultural Heritage

2.3. Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage in Relation to Circular Economy and Sustainability

3. Methodology

4. Analysis of Study Area

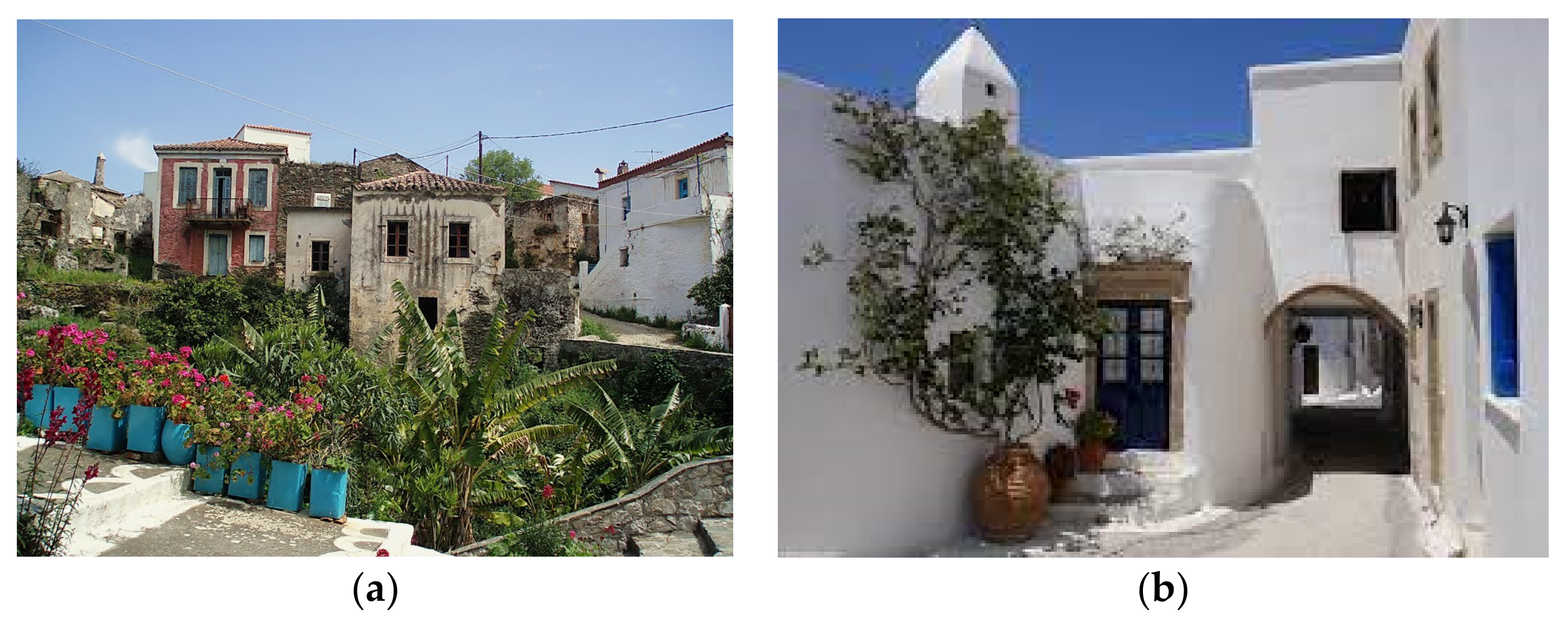

4.1. The Case Study of Kythera Island

4.2. Investigation of the Opinions of Kythera’s Residents and Visitors about the Island’s Development Prospects

5. Assessment of Findings—Issues to Be Addressed and Potentials for the Sustainable Development of Kythera

6. Proposal Schemes

6.1. Adaptive Reuse of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool of Sustainable Development of Kythera

- The revealing of the lesser known cultural assets of Kythera

- The management of the large abandoned housing stock

- The enhancement of the less developed northern settlements of the island

6.2. Proposal Scheme 1: Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Assets of Special Ownership (Eghorios Periousia—English Schools)

6.3. Proposal Scheme 2: Adaptive Reuse of Abandoned Buildings in the Core of Traditional Settlements

6.4. Proposal Scheme 3: Adaptive reuse of Mavrogiorgiannika, an Abandoned Neighborhood

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mallouhou-Tuffano, F. Protection & Management of Monuments—Historical and Theoretical Approaches; Association of Greek Academic Libraries: Athens, Greece, 2015; pp. 12–23. ISBN 978-960-603-377-3. [Google Scholar]

- Yiannakou, A.; Eppas, D.; Zeka, D. Spatial Interactions between the Settlement Network, Natural Landscape and Zones of Economic Activities: A Case Study in a Greek Region. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wijesuriya, G. Annex 1: Living Heritage: A Summary. Rome: ICCROM. 2015. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/wpcontent/uploads/PCA_Annexe-1.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: Living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. Sustainable Development and Rural Tourism in Depopulated Areas. Land 2021, 10, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, R. World Heritage on the Move: Abandoning the Assessment of Authenticity to Meet the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century. Heritage 2021, 4, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, P.; Roders, A.P.; Colenbrander, B. Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: An overview of global monitoring tools. Cities 2017, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravanguolo, A.; De Angelis, R.; Iodice, S. Circular Economy Strategies in the Historic Built Environment: Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual STS Conference Graz 2019. Critical Issues in Science, Technology and Society Studies, Graz, Austria, 6–7 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPON. In The Development of the Islands—European Islands and Cohesion Policy (EUROISLANDS); Final Report; European Comission: Luxemburg, 2013; Available online: https://www.espon.eu/programme/espon/espon-2020-cooperation-programme (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Sustainable and Resilient Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) in Remote Mediterranean Islands: A Methodological Framework. Heritage 2021, 4, 3469–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratification of Agreement for the Protection of Architectural Heritage (Law 2039/1992, Official Gazette of the Greek Government No 61/13.04.1992). Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-arxaiotites/nomos-2039-1992-phek-61a-13-4-1992.html (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Protection of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage (Law 3028/2002, Official Gazette of the Greek Government No 153/28.06.2003). Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-arxaiotites/n-3028-2002.html (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Vyzantiadou, M.M.; Selevista, M. Protection of Cultural Heritage in Thessaloniki: A Review of Designation Actions. Heritage 2019, 2, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Y.-F.; Chen, C.-P.; Chou, R.-J. The Key Factors Influencing Safety Analysis for Traditional Settlement Landscape. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention, European Treaty Series—No. 176, Strasbourg, France, 20 October 2000. p. 7. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680080621 (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- COE. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society in Faro; Council of Europe Treaty Series—No. 199, Faro, Portugal, 27 October 2005. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-convention (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- UCLG. xecutive Bureau. Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development, in Draft Proposal for Approval of the UCLG Executive Bureau; World Summit of Local and Regional Leaders—3rd World Congress of UCLG, Mexico, 17 November 2010. Available online: https://www.agenda21culture.net/sites/default/files/files/documents/en/zz_culture4pillarsd_eng.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Potts, A. Climate Heritage Network, European Cultural Heritage Green Paper; The Hague & Brussels 2021. Available online: https://issuu.com/europanostra/docs/20210322-european_cultural_heritage_green_paper_fu (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Pickard, R. Funding the Architectural Heritage: A Guide to Policies and Examples; Council of Europe Publications: Strasbourg, France, 2009; pp. 12–20. ISBN 9287164983. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J.; Gordon, I.J. Adaptive Heritage: Is This Creative Thinking or Abandoning Our Values? Climate 2021, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S.; Ciuffo, B.; Nijkamp, P. A systemic framework for sustainability assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moropoulou, A.; Delegou, E.T. Innovative technologies and strategic planning methodology for assessing and decision making concerning preservation and management of historic cities. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium of the Organization of World Heritage Cities, Rhodes, Greece, 23–26 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roszczynska-Kurasinska, M.; Domaradzka, A.; Wnuk, A.; Oleksy, T. Intrinsic Value and Perceived Essentialism of Culture Heritage Sites as Tools for Planning Interventions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomopoulou, E.; Delegou, E.; Sayas, J.; Moropoulou, A. An innovative approach to the protection of cultural heritage: The case of cultural routes in Chios Island, Greece. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 14, 742–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G. Circular economy strategies for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage buildings to reduce environmental impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLIC Project. Available online: https://www.clicproject.eu/ (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Baker, H.; Moncaster, A.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Decision-making for the demolition or adaptation of buildings. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Forensic Eng. 2017, 170, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Micheletti, S.; Bosone, M. A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-470-65574-0. [Google Scholar]

- Radoine, H. Urban conservation of Fez-Medina. Global Urban Dev. 2008, 4. Available online: https://www.globalurban.org/GUDMag08Vol4Iss1/Radoine.htm (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- MedINA INCREAte Project Website. Available online: https://increate.med-ina.org/el/page/published-project/5 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Georgiadis, N.M.; Melissourgos, Y.; Dodouras, S.; Lyratzaki, I.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Foutri, A.; Mordechai, L.; Zafeiriou, R.; Papayannis, T. Reconnecting Nature and Culture—The INCREAte Approach and Its Practical Implementation in the Island of Kythera. Heritage 2019, 2, 1630–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodouras, S.; Liratzaki, E. Recording and Evaluation of the Cultural Characteristics of Kythera and Antikythera; MedINA: Athens, Greece, 2017; pp. 9–14, 72–76. Available online: https://med-ina.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Kythera-Cultural-Rapid-Assessment.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Bury, J.B.; Meiggs, R. A History of Greece, Greek Translation; Kardamitsa Publications: Athens, Greece, 2011; pp. 84, 420–423, 436, 441. ISBN 0333154932. [Google Scholar]

- Koukkou, E. History of the Ionian Islands from 1797 until the British Occupation; Papadima Publications: Athens, Greece, 1983; pp. 16, 32–40. ISBN 9789602064504. [Google Scholar]

- Filippidis, D. Greek Traditional Architecture—Kythera; Melissa Publicalions: Athens, Greece, 1983; pp. 3–24. ISBN 9602041366. [Google Scholar]

- Eghorios Periousia Website. Available online: https://www.eghorios.gr/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Municipality of Kythera. Strategic Planning of the Municipality of Kythira. 2011, pp. 50–54. Available online: http://kythira.gr/oldsite/downloads/Strat_sxed.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Sougiannis, C.H. Principles of protection of modern monuments—The example of the traditional settlement Mavrogiorgiannika in Karavas, Kythera. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference Myth & Reality, Kythera, Greece, 20–24 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Caradimas, C.A. Analysing and Understanding the Construction of Vernacular Buildings at the National Technical University of Athens. Arch. Urban Plan. 2013, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimatis, G. The Institution of Domestic Wealth Board. In The Union of the Ionian Islands with Greece; Greek Parliament Publications: Athens, Greece, 2005; pp. 300–324. ISBN 978-960-560-082-2. [Google Scholar]

- Leontsini, E. Domestic Wealth Board of Kythera and Antikythera-History and Politics. In Kythera: Myths and Reallity; Free Open University of Kythera Publications: Athens, Greece, 2003; pp. 241–252. ISBN 9789608774223. [Google Scholar]

- Municipality of Kythera. Sustainable Energy Action Plan; Municipality of Kythera: Kythera, Greece, 2016; pp. 25–30. Available online: https://mycovenant.eumayors.eu/docs/seap/22050_1490862892.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Kythera Trails Website. Available online: https://kytheratrails.gr/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Kythera Institution of Culture and Development Homepage (KIPA). Available online: Kipa-foundation.org (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Leader/CLLD Website. Available online: https://ead.gr/information/leader-clld/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe Programme. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Karavasili, M.; Mikelakis, E. Cultural Routes, towards an interpretation of the “cultural landscape” with de a development potential. Archeol. Arts 1999, 71, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomopoulou, E.; Delegou, E.T.; Vesic, N.; Moropoulou, A. Innovative Cross-Cultural Approach for the Emergence of Common Cultural Heritage in Greece and Serbia a Comparative Study of the 13th–14th Century Orthodox Monasteries, Scienza e Beni Culturali XXVII; Arcadia Ricerche Editore: Padova, Italy, 2011; pp. 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Moropoulou, A.; Lampropoulos, K.; Vythoulka, A. The Riverside Roads of Culture as a Tool for the Development of Aitoloakarnania. Heritage 2021, 4, 3823–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastakis, C.; Buhalis, D.; Butler, R. The perception of small and medium sized tourism accommodation providers on the impacts of the tour operators’ power in Eastern Mediterranean. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vehbi, B.O.; Hoşkara, Ş.Ö. A Model for Measuring the Sustainability Level of Historic Urban Quarters. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2009, 17, 715–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Unburying Hidden Land and Maritime Cultural Potential of Small Islands in the Mediterranean for Tracking Heritage-Led Local Development Paths. Heritage 2019, 2, 938–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrouni, K. Sustainable urban conservation of historical cities come back to thirty five years of observation in Medina Fez, Marocco. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 19th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium “Heritage and Democracy”, New Delhi, India, 13–14 December 2017; Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/1946/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Labadi, S.; Giliberto, F.; Rosetti, I.; Shetabi, L.; Yildirim, E. Heritage and the Sustainable Development Goals: Policy Guidance for Heritage and Development Actors; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 22–25. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Secretariat/2021/SDG/ICOMOS_SDGs_Policy_Guidance_2021.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Aldeia da Pedralva Webpage. Available online: https://www.aldeiadapedralva.com/en/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Agapito, D.; Mendes, J.; Valle, P.O. The rural village as an open door to nature-based tourism in Portugal: The Aldeia da Pedralva case. Tourism Rev. 2012, 60, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Redock Project Webpage. Available online: https://www.redock.org/projects/project-spain/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Henche, B.; Salvaj, E.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. A Sustainable Management Model for Cultural Creative Tourism Ecosystems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikić, H. Sustainable cultural heritage management in creative economy: Guidelines for local decision makers and stakeholders. In Cultural Heritage & Creative Industries; Rypkema, D., Mikić, H., Eds.; Creative Economy Group Foundation: Belgrad, Serbia, 2015; pp. 9–24. ISBN 978-86-88981-06-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nižić, M.; Ivanović, S.; Drpić, D. Challenges to Sustainable Development in Island Tourism. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2010, 5, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, M. Merging Culture and Tourism in Greece: An Unholy Alliance or an Opportunity to Update the Country’s Cultural Policy? J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2012, 42, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuttari, A.; Della Lucia, M.; Martini, U. Integrated planning for sustainable tourism and mobility. A tourism traffic analysis in Italy’s South Tyrol region. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 614–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Buhalis, D. A model of perceived image, memorable tourism experiences and revisit intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, A.S.; Smriti, D.; Sanjay, N.; Schuett, M.A.; Dahal, S.; Nepal, S. Local perspectives on benefits of an integrated conservation and development project: The Annapurna conservation area in Nepal. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2016, 8, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuceer, H.; Vehbi, B.O. Adaptive Reuse of Carob Warehouses in Northern Cyprus. Open House Int. 2014, 39, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifi, Y. Role of universities in preserving cultural heritage in areas of conflict. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsouris, A. Social learning and sustainable tourism development; local quality conventions in tourism: A Greek case study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsartas, P. Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R.; Adamov, T.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Lile, R.; Rujescu, C.; Marin, D. Agritourism—A Sustainable Development Factor for Improving the ‘Health’ of Rural Settlements. Case Study Apuseni Mountains Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Elements | Observations |

|---|---|

| History and monuments | Diverse cultural reserve, unexploited assets |

| Spatial organization | Large number of settlements, less promoted northern settlements |

| Traditional architecture | Diverse architectural elements |

| Social organization | Inter-communal management tradition (Eghorios Periousia) |

| Demography | Decreasing, aging population |

| Elements | Evaluation | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural reserve | positive | Residents and visitors |

| Natural environment | positive | Residents and visitors |

| Mild tourism development | positive | Residents and visitors |

| Local transportation | negative | Residents and visitors |

| Accessibility | negative | Residents and visitors |

| Decrease of permanent residents | negative | Residents |

| Duration of touristic season | negative | Residents |

| Sufficient involvement with organic farming | negative | Residents |

| Updating and cooperation | negative | Residents |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vythoulka, A.; Delegou, E.T.; Caradimas, C.; Moropoulou, A. Protection and Revealing of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool for Sustainable Development: The Case of Kythera Island in Greece. Land 2021, 10, 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121324

Vythoulka A, Delegou ET, Caradimas C, Moropoulou A. Protection and Revealing of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool for Sustainable Development: The Case of Kythera Island in Greece. Land. 2021; 10(12):1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121324

Chicago/Turabian StyleVythoulka, Anastasia, Ekaterini T. Delegou, Costas Caradimas, and Antonia Moropoulou. 2021. "Protection and Revealing of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool for Sustainable Development: The Case of Kythera Island in Greece" Land 10, no. 12: 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121324

APA StyleVythoulka, A., Delegou, E. T., Caradimas, C., & Moropoulou, A. (2021). Protection and Revealing of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool for Sustainable Development: The Case of Kythera Island in Greece. Land, 10(12), 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121324