Abstract

Protected areas (PAs) are designated to safeguard specific areas with natural and cultural values. Importantly, appropriate management is vital for PAs to achieve their conservation goals. Therefore, the management staff is essential for guaranteeing the successful management of PAs and delivering outstanding organizational performance. In China, staff faces many difficulties when conducting conservation activities because of an inefficient management system, and the lack of relevant laws and regulations. Recently, the Chinese government has been attempting institutional reforms and developing a pilot national park system to address these problems. We reviewed international and Chinese literature to examine how various aspects of these proposed changes can impact management staff’s activities. Furthermore, we analyzed the aspects of current institutional reforms related to management staff. The results revealed that the National Park Administration’s establishment is a potential solution to China’s cross-sectional management. We suggest that the country should formulate relevant laws and funding systems that are fundamental for the success of both management staff’s conservation activities and PAs.

1. Introduction

Protected areas (PAs) have been widely considered as the first line of defense and a cornerstone in the effort to protect global biodiversity [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. PAs require active protection of specific areas with ecological, natural, or even cultural values [8,9], and deliver benefits locally and globally [10]. Globally, PAs have proved to be among the most successful tools to protect natural ecosystems [11,12,13,14,15], despite some failures [16]. If appropriately designed and effectively managed, PAs can be a powerful tool to halt biodiversity loss, mitigate the effects of climate change on the human community, and sustain valuable and critical ecosystem services [17,18].

As crucial instruments needed by all global conservation strategies [19], PAs have dramatically increased from less than 1 million km² in 1970 [20] to 20,749,121 km², that is, approximately 15.4% of the earth’s land surface [21]. However, the rate of increase in the coverage area and the development speed does not guarantee that all aspects required for the success and effectiveness of PAs are achieved. Human-induced global losses of ecosystem services, habitat, and biodiversity have the most negative impacts on PAs [22,23,24,25]. Therefore, PA management is crucial for various conservation ambitions and providing tangible and intangible benefits [26]. Thus, PA management staff face challenges in achieving various management objectives, such as incompatible management objectives, uncertain influencing factors of nature and society, conflicts among stakeholders, and shortage of funding and human resources [27]. Management problems have been identified and documented worldwide, such as deficiencies in management effectiveness [28,29,30,31], law/regulation enforcement challenges [32,33,34,35], underfunding [36,37,38], and stakeholder collaboration/conflicts [39,40,41].

PA systems rely on people, that is, PA management staff [42], to fulfill their conservation objectives. Staff are important in many sectors and deliver outstanding organizational performance [43]. The world’s PAs are typically managed by dedicated staff with unparalleled passion and commitment [42], and they are essential in guaranteeing successful management; hence, the success of PAs [44]. Staff cannot plan, manage, and monitor without proper knowledge, attitudes, skills, capabilities, and tools [45]. Traditionally, staff used to primarily protect the environment. However, their roles have transformed because of pressure from human activities. Today, staff must provide benefits to stakeholders and prevent potential threats to PAs caused by humans [27], which creates complex and difficult problems for management staff.

PAs management functions must be realized by staff. Various functions require specific management staff; however, an individual staff member typically manages multiple roles. Large responsibilities and difficult tasks are placed upon staff’s shoulders [46] because of their contributions to in situ nature conservation. They are responsible for the protection of land, natural resources, and ecological biodiversity within legislated PAs [47]; additionally, they must handle technical and managerial factors, as well as human relations [48]. PA management staff’s importance and value are indicated by the increasing global awareness of their jobs, and the advocacy for building staff capacity and professional training [37,42,49].

PA management agencies are important standing bodies for resource conservation, scientific research, and routine management activities [50]. Unfortunately, despite their crucial roles [48], PA management staff have received insufficient attention in the literature, especially in China. Despite large differences in the mean number of management staff in PAs worldwide, the number of staff has proven to be correlated with good performance in good biodiversity conditions and management effectiveness [51]. Staffing is not an uncommon challenge in the planning and management of PAs [52] and can be a problem for any developing or developed country. However, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have been conducted directly on management staff in China’s PAs.

We believe that China’s PA management faces the aforementioned problems related to staff work performance and conservation outcomes. Since the first PA was established in 1956, China has gradually developed its PA system with various types, layouts, and functions [53,54], resulting in 13 different categories of PA systems [55]. However, official statistics are unavailable to distinguish the number of each type of PA [10]. Management agencies with a certain number of staff members have been reportedly established at all national-level PAs, with most being equipped with management stations [56]. The development and management of PAs are of extreme significance for China and the world because the country harbors many ecosystems of global importance [23], and is one of the wealthiest countries in terms of biodiversity [57].

However, despite numerous efforts to establish and develop PAs, the management of conventional PAs (CPAs) in China has been widely criticized. Wang [58] explored and analyzed the cross-departmental management of a PA. The author also discussed the issues of multi-designation, which means that a single PA can have multiple classifications. Cross-departmental management and multi-designation occur in national programs, including global ones. The author [58] indicated that these features could cause confusion and complexity, which management staff can feel instantly and directly. In mainland China, CPAs are managed by 10 government departments. Staff can be affected by this as multiple departments manage their daily jobs, and convey instructions and requirements for conservation [59]. Furthermore, different structural and management issues have contributed to the restrictions on management staff’s conservation efforts [60].

The lack of involvement of local communities in the management process and ignorance of their interests have ignited conflicts between CPAs and residents [61]. This can inevitably lead to local communities’ disagreement with CPA establishment and operation, which hinders management staff’s performance and overall efficiency.

Underfunding is another issue facing many CPAs in China. This has caused other problems due to increased revenue-generating activities (commercialization) in CPAs and disturbance to wildlife [10,62,63]. Incomplete legislation has been identified by Jim and Xu [64], and Li and Han [65] as another fundamental problem in China.

As of 2018, Chinese PAs full-time management staff comprised 45,000 personnel (including 13,000 technical staff). The mean input ratio of management staff was 19.2 per 1000 km², which is significantly lower than that of the global mean of 27 per 1000 km², an estimation made more than 20 years ago [66]. In China, national-level management agencies (such as the State Forestry Administration and the Ministry of Ecological Environment) create general conservation plans for CPAs. These plans are received, studied, and implemented by the management staff [60]. However, some CPAs in China are surprisingly devoid of regular and full-time management staff [62].

In 2013, China’s central government proposed a pilot national park (PNP) system to play a vital role as a top-down method for solving the persisting management issues of CPAs. The PNP system is expected to enhance management practices for PAs in China [67,68]. In 2017, China published the General Plan for the Establishment of the National Park System to formally enact the PNP system and establish 10 PNPs by 2020 [67,69].

Here, we aim to present the reasons for and drawbacks of CPA management in China which cause dilemmas for management staff when conducting conservation activities. This study considered the significance of management staff in various conservation strategies and objectives in China’s PAs, and their burden due to pressures facing PAs and from nearby residents [52]. Additionally, we explored the solutions provided by the PNP systems to solve these issues. We also examined the PNP systems’ limitations by comparing them with the CPA system, and consequently, outlined some countermeasures. Notably, many publications are written in Chinese, which hinders international attention and access. Thus, our review is significant as it addresses this global academic incoherence.

2. Materials and Methods

We reviewed international and Chinese peer-reviewed literature on mainland China’s PA management and management staff. We also validated documents from government departments and official media. The online search engine Web of Science was used because China’s new PNP system has attracted insufficient international attention. The latest publications are in Chinese; therefore, the China Integrated Knowledge (CNKI) Resources Database was selected as an additional source.

In Web of Science, we checked the fields of title, topic, and research area. From the CNKI Resource Database, we checked the fields of title, abstract, topic, and keywords of “China”, “protected areas”, “national parks”, “pilot national parks”, “management”, “management staff”, “law and regulation”, “funding”, “community”, or “community co-management area”. Selected papers were from 1994 to 2021, and contained content and analysis related to management staff or factors influencing their daily management activities. Most Chinese publications had English titles and abstracts. Those without an English title were carefully read and understood to guarantee satisfactory information extraction and translation. For the definition of “management staff”, we could not analyze each position, such as rangers, patrolmen, managers, and technicians, in detail because of the absence of literature on each title.

Furthermore, the same position can have distinct titles in different PAs and countries. As this research aims to examine existing problems, we selected papers that focused on problem exposures and analyses according to the whole reviewing scheme. We carefully analyzed the major ideas presented in papers with different or even conflicting viewpoints.

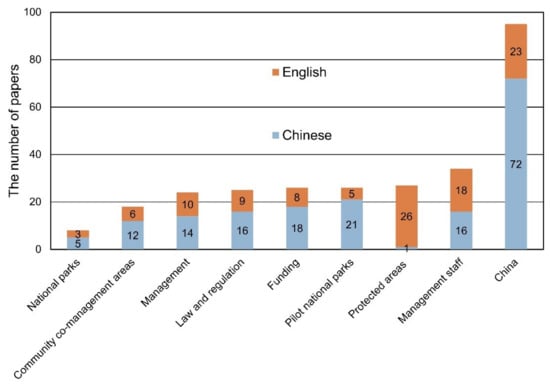

In total, 137 publications were identified; 72 were in Chinese, including four institutional documents. Chinese papers were from CNKI, and the rest were from the Web of Science. Figure 1 shows the number of papers analyzed by term. “China” was used in most papers (94); followed by “management staff” (34); then “management”, “law and regulation”, “funding”, “pilot national parks”, and “protected areas” in approximate numbers (24 to 27); “community co-management areas” in 18, and “national parks” with the least at 8.

Figure 1.

The number of papers analyzed for different keywords.

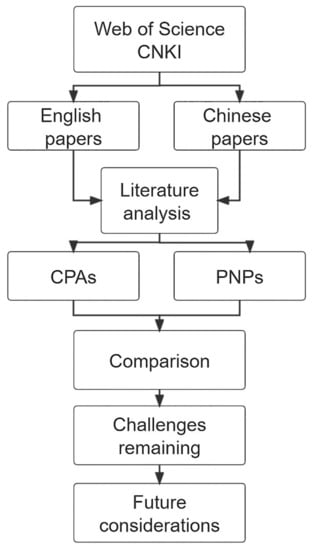

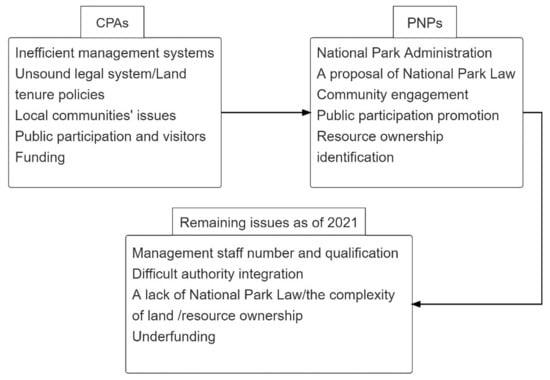

For the content analysis, we first reviewed and explored the problems of CPAs in terms of their management and institutional aspects, including a lack of clear and definite management objectives, cross-sectional management systems, confusion between administration and business operations, and their negative impact on staff. We explored other issues that can negatively impact management staff, including unsound legal systems, issues with local communities, public participation and visitors, underfunding, and an unclear land tenure system. Later, the recently proposed PNP system was analyzed and compared with the CPA system. Thereby, we identified the issues that can and cannot be solved using the PNP system (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Methods and methodological flow. CNKI: China Integrated Knowledge, CPAs: Conventional protected areas, PNPs: Pilot National Parks.

3. Results

3.1. Inefficient Management Systems

3.1.1. A Lack of Clear and Definite Management Objectives

China’s CPAs have been established indiscriminately without considering the top-level design, and have been classified based on their conservation targets rather than clear and defined management objectives [69,70]. The Lushan Geopark is also included in the World Heritage Sites’ network (cultural categories); this leads to confusion among management staff simply because these two types of PAs have different targets for conservation and management. The types of CPAs are related to their governing departments in China. Each CPA has an independent functional system and is disconnected from the other CPAs. In a single CPA, problems of unclear concepts, inappropriate operations, and artificial arbitrariness exist [55,71,72,73]. This can hinder management staff from understanding and prioritizing goals, including satisfactory performance and conservation outcomes.

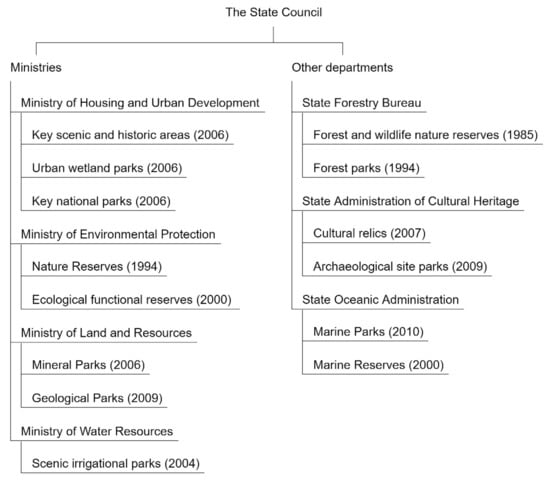

3.1.2. Cross-Sectional Management System

Cross-sectional management and unclear powers and responsibilities are other major issues in the CPA management system [69,74,75]. Along with the rapid development of CPAs, the overlapping of natural ecological areas separated from sectoral factors has led to several problems, such as imbalanced development, under-protection, or over-protection [76,77] (Figure 3). A single CPA may be managed by multiple management systems. For instance, water bodies (managed by the Ministry of Water Resources), and aquatic animals and plants (managed by the State Forestry Bureau) are organic wetland ecosystems within a CPA. Thus, they are separately managed by different departments with various standards and conservation priorities for China’s PAs [78,79]. Unclear tenures lead to the cross-sectional management of PAs lands and resources [67].

Figure 3.

The management system of China’s CPAs. Year denotes the year of establishment.

Furthermore, a single CPA can be designated with several titles. For instance, the Jiuzhaigou National Park in Sichuan Province was designated in 2004. Previously, it was defined as the Jiuzhaigou National Nature Reserve in 1978. In 1982, it was designated as part of the Huanglong Temple, and Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic and Historic Interest Area. Finally, it was also designated as Jiuzhaigou National Forest Park in 1995 [58].

3.1.3. Confusion among Administration and Business Operations

PA management agencies are a mixture of administrative bodies and business enterprises because of a lack of relevant regulations. They are responsible for conservation, law and regulation enforcement, management, development, and business operations [80]. This feature leads to a focus on profit-making rather than conservation [81]. The mixture of management bodies and business operations makes it difficult for staff to fulfill conservation activities [71] because conservation receives less priority.

3.2. Unsound Legal Systems

Law enforcement is weak and unavailable in many of China’s CPAs because of inaction under PA legislation [82] and the substitution of department laws for state laws [83]. Usually, the CPAs management departments do not have the legal authority to implement punishment, making it difficult for staff to perform their duties in management [84] and conservation. There is a lack of long-term and effective management and supervision mechanisms. Various departments can exercise administrative supervision and law enforcement, which results in overlapping functions leading to sectional conflicts and low efficiency. In contrast, unbalanced supervision and low enforcement power emerge due to disconnections among departments [85].

Furthermore, historical issues related to the complex land tenure system, and ambiguities in-laws and regulations have restricted CPA development in China [86]. Ambiguous land tenure and land-use rights resulted in multiple ownership of the same CPA and complex purposes, leading to potential conflicts [84]. To a great degree, China depends on administrative authorities to construct CPAs rather than legal procedures and foundations. Of the 65 PAs constructed between 1979 and 1990, 20 lacked land use rights. Under such circumstances, management agencies and staff find themselves in disputes with other owners [71].

Another common phenomenon is the existence of collectively-owned forests [59]. The delay in-laws and regulations is a crucial factor restricting reforms to collectively-owned forests [87,88,89]. Reforming collectively-owned forests can pose challenges and threaten the construction of CPAs in China [59,87].

3.3. Local Communities’ Issues

Most of China’s CPAs are in remote, resource-rich, but impoverished areas that are home to many aboriginals [90]. For example, 1,227,935 residents in 85 CPAs were identified by Hone et al. [71]; two of these CPAs, the National Reserves of East Dongtinghu and Qilianshan, have 200,000 residents. Moreover, there were 5,019,063 residents in neighboring areas of the 85 CPAs. The conservation of natural resources inevitably triggered conflicts between CPAs and the aboriginal communities, whose access to resources was restricted, and lifestyle changes were forced; this resulted in the recurrence of illegal activities, including poaching and logging [85,91].

Management staff faces a dilemma when dealing with these cases because there are illegal activities that must be addressed. In contrast, punishments inevitably lead to hostility from residents and more persistent conflicts [92]. High population pressure requires a stronger management capacity [93,94]. However, residents’ rights are not stated in relevant regulations [95], and their benefits are ignored and excluded from economic activities in PAs [86,95]. Despite ecological compensation schemes, the lack of clarity over detailed implementation procedures has resulted in uncertainties [68].

3.4. Visitor Behaviors

Visitors’ ecological awareness and behavior is another factor that influences management staff’s activities and outcomes. Chinese visitors are criticized in many aspects as they usually feed wild animals, tread on vegetation, and damage the environment [96]. This uncivilized behavior brings pressure and danger to management staff, as they must employ extra effort to erase the negative impact [97]. Qingdao News (an official local media outlet) [98] reported that 12 management staff had to clean 360 tons of rubbish produced by visitors during the Chinese Spring Festival National Holiday in 2015. The rubbish was hung or stuck on the cliffs; therefore, staff had to use hanging ropes during the clean-up, which was a difficult and life-threatening job [98]. Xue [99] stated that a study found that over 90% of visitors had engaged in bad behavior, including littering, vandalism, and graffiti, in the Maiji Mountain Scenic Area, China. These types of behaviors are most likely observed among Chinese visitors, although there is no study showing international visitors’ misbehavior in China’s PAs.

3.5. Underfunding

The situation of China’s funding for CPAs remains unclear [54,100]. Researchers have indicated that underfunding is an essential reason for poor management performance and outcomes of CPAs in China [101,102]. Local governments provide funding for the construction and management of PAs, which places a burden on them. Zhe and Jian [9] systematically examined CPA management costs and found that it was 8591 million yuan (1319.56 million US dollars) for all CPAs in China in 2014. However, the funding in the previous year was even less at 2195 million yuan (337.15 million US dollars).

Uneven funding investment and allocation among various levels of CPAs is a noteworthy problem in China [54]. Generally, non-national level CPAs are underfunded [103]. Unsound and inappropriate funding mechanisms lead to underdeveloped management agencies and a shortage of management staff. Hence, there is a lack of effective management, and consequently, failure in conservation objectives [104].

In contrast, national-level CPAs have adequate funding. However, this does not mean that national-level CPAs do not face problems with the funding system. Wang et al. [105] concluded that approximately 69,580 thousand Yuan (10,690 thousand US dollars) was invested in the Qinling National Nature Reserve Group each year; this was twice as much of what was needed, as calculated by Yang and Wu at 30,620 thousand Yuan (4704 thousand US dollars) [9].

4. Discussion

4.1. Current Institutional Reform

Worldwide, the management staff is of great significance to PAs. They are the unswerving performers of sophisticated conservation schemes, and practitioners of ecological protection and restoration efforts. However, many factors hinder the routine work of staff. China’s CPA management staff suffer from the cross-sectional management system, absence of a sound legislation system, ambiguity in land tenure policy, conflicts with local communities, a lack of rapport with the public and visitors, and underfunding/inappropriate budgeting. Together, these aspects have imposed challenges on management staff and their effectiveness. The Chinese central government has realized and recognized these problems [68] and attempted to implement institutional reforms [8] to address these issues.

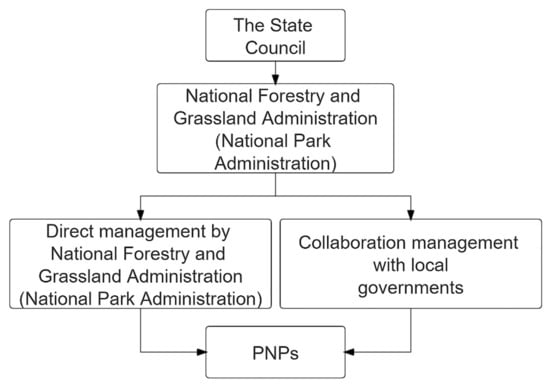

In 2018, a critical reform integrated various CPAs, managed separately by different departments, into the newly established National Forestry and Grassland Administration (also called the National Park Administration, or NPA) [106], as shown in Figure 4. The NPA manages PNPs directly or in collaboration with local governments.

Figure 4.

Newly proposed management (PNP) system (Modified from [68]).

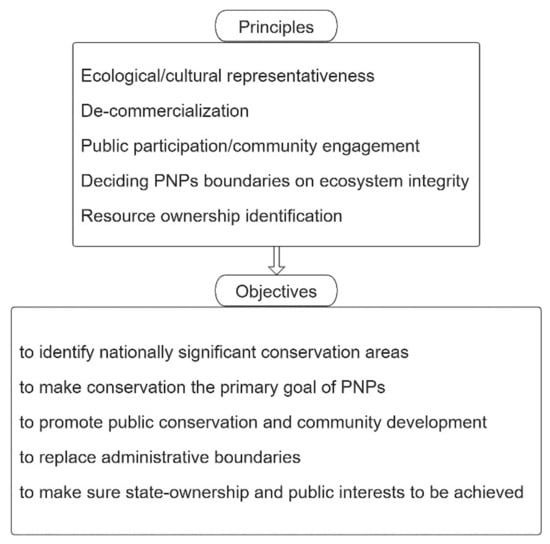

This reform is expected to be a dose of elixir to the thorny problem of cross-sectional and overlapping management [8]. China’s new PA system (National Park at its core) and the initiatives of PNPs have received extensive attention [104], and have made significant progress [107]. China’s new PNP system has set fundamental guiding principles [108,109,110,111] for CPAs to follow based on the experience and lessons from the old CPA system (Figure 5). These principles aim to solve the issues and pain points of CPA systems. This reform is expected to lay a solid foundation for more unified and effective management in which PA management staff can conduct their conservation activities effectively. Importantly, China may expect a more fruitful conservation outcome in the future.

Figure 5.

Principles and objectives of the PNP system.

4.2. Remaining Issues in the PNP System

China’s current efforts in the PNP system have brought new insights and solutions to the existing issues of CPAs by constructing a unified state-level management agency—the National Forestry and Grassland Administration (or NPA). However, it faces challenges, such as an unsound management system, unclear resource background information, and weak law enforcement [104,112,113]. Neither the current issues of CPAs nor the difficulties experienced by the management staff can be completely solved with the new system (Figure 5). Figure 6 summarizes the deficiencies of the CPAs and solutions produced by the PNPs. A careful examination and comparison between the two systems show the remaining issues that could exert a negative impact on management staff.

Figure 6.

Issues of CPAs, countermeasures of PNPs, and remaining issues as of 2021.

4.2.1. Shortage of Management Staff Numbers and Qualifications

Yang and Wu [9] calculated that China’s PAs should be equipped with 108,048 management staff in 2014; however, the actual number was 44,565 (41.25%). There should have been 2729 management agencies, but the actual number was 1854. Nearly one-third of PAs did not have management agencies and much less management staff. The shortage of human resources places a heavy burden on management staff, leading to less satisfactory job performance.

Additionally, the lack of a detailed human resource scheme, clear work aims, and appropriate job descriptions create certain barriers to the management outcomes of staff [114]. The lack of professional training for staff makes them conduct management activities incompetently [115,116]. Moreover, a system of motivation for management staff is missing, which hinders their willingness and ambition to develop professional skills [91].

4.2.2. Difficulty in Authority Integration

At the national level, the current reform involves several departments, such as the State Forestry Bureau, Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, Ministry of Land and Resources, and State Administration of Cultural Heritage (Figure 3). Complex property rights and interests, and departmental conflicts make it difficult to integrate [79]. Moreover, merging two or more departments is complicated because of diverse goals and rules [8]. Local governments are expected to handle their responsibilities and roles as they are the operators of economic development within the parks; they have to manage local communities, provide public services, prevent natural disasters, and supervise market activities [117]. However, during the reform process, local governments may have a different understanding of the central government’s policies [54], and use national parks as revenue generators by constructing high-volume scenic attractions and other hospitality infrastructures. This is especially noteworthy, as China’s PNP system is being developed. Appropriate supervision is necessary to avoid these issues. Remote sensing technology has identified an expanding trend in development and construction activities in some pilot parks [113].

4.2.3. Lack of National Park Law

Many legal impediments hinder current efforts in institutional reform [113]. China has neither issued high-level laws and regulations for parks at the national or local levels. Furthermore, the legal rank of the current laws and regulations is ineffective and lacks the power to guarantee the status and personnel allocation for the NPA [118]. The proposed PA law failed previously because of the discrepancies among different departments related to PAs [8]. In the Qilianshan Pilot National Park, illegal mining exploration activities and hydropower projects have caused significant environmental issues owing to unsound laws and enforcement regulations [119,120]. In addition, the park’s designation created an emerging conflict with livestock grazing (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Livestock grazing is practiced along the valley bottom near the proposed Qilianshan Pilot National Park. They graze their livestock on the mountain slopes in the proposed national park area (background) in summer, which resulted in a conflict with the park administration. (Photo: T.W., September 2017).

4.2.4. Complexity of Land Tenure and Resource Ownership

Due to the unclear ownership of land in some PNPs, management staff are unable to effectively manage their resources and lack the power, or right to prevent resource extraction or construction activities within the PNPs [121]. Table 1 shows the proportion of land ownership in PNP areas in China. In Qianjianyuan and Wuyi Mountain National Park, collectively owned land accounts for more than 70%. This makes it difficult to conduct land and resource management [122].

Table 1.

China’s PNPs’ proportion of land ownership (Modified from [113]).

4.2.5. Underfunding

The local government funds PAs in China; however, this often leads to the issue of underfunding. Consequently, the financial requirements for management staff’s daily jobs cannot be met [7]. This is a significant problem because insufficient resources can lead to unfavorable environmental impacts, such as habitat loss [122].

Moreover, monitoring mechanisms for funding are lacking. This means that rules to regulate how and where funding should be used are not available [80]. Although social organizations and individuals currently have a fervent desire to invest in PAs, it remains uncertain due to the lack of relevant laws and regulations in nongovernmental investment [123]. However, one of the greatest problems that PAs face because of inadequate resources is habitat loss and degradation [123]; this threat affects all species of fauna and flora.

5. Future Considerations

China has identified its problems in nature conservation and adopted countermeasures, that is, the ongoing institutional reform and the PNP system. However, the persisting problems discussed above should be studied, and adopted for a better outcome from the current effort and ambitions. These efforts and ambitions cannot be conducted without the management staff’s commitment and contribution. Hereby, we recommend the following suggestions related to the management staff and their performance.

5.1. Management Staff

A leading group should be established to organize personnel, relevant experts, and scholars [124]. Regular training should be provided to management staff to improve their understanding of PAs and their capabilities. Further, a talent incentive should be developed to attract more personnel as management staff [107,124,125].

5.2. Unified Management System

The central government should promote cooperation between various departments at national and local levels to achieve high efficiency of PA management [126], and establish a favorable working environment for staff performance. Additionally, it is recommended that PA management staff are not involved in business operations so that they can concentrate on efficiently managing the PAs [127]. Moreover, China should establish a diversified, sustainable community development and management mechanism to directly, or indirectly, involve residents in PA construction and management activities [116,128].

5.3. Law and Regulation System for Management Staff

A stable legal system is an important guarantee for China’s PAs and new national parks. This is crucial for management staff because they need a strong legal base and references to conduct their daily management work. The National Park Law (NPL) should be formulated immediately to clarify the status of the NPA as the main management body to ensure its effectiveness. The legal rank of NPL should be higher than economic laws, such as the Forest Law and Grassland Law [129]. First, the NPL should be formulated by the National People’s Congress (NPC). It does not require too many clauses and aims to determine its principles. Furthermore, China should formulate specific regulations on the management of each national park according to its characteristics to realize the country’s goal of “one park, one law or one regulation” [116,130,131].

5.4. Public Engagement

The public and stakeholders should be encouraged to participate in the PA management process. Encouraging local communities to participate in the development and management of PAs can generate opportunities to bring certain economic benefits to the residents. Additionally, this will connect them to conscious activities in the protection of the ecological environment, effectively resolving conflicts between local communities and PAs [132]. We suggest formulating policies for profit sharing to ensure that residents have a stable and reasonable income. This should encourage active public participation, which can benefit management staff as a positive complementary force in conservation and governing activities.

Regarding non-economic aspects, many PAs have a concentration of scenic resources, and are preferable locations for people to visit and enjoy; they can also perform recreational, scientific, and cultural activities [132]. Thus, we recommend that policymakers consider finding feasible compromises between conservation and community needs. Management choices should consider both local livelihoods and conservation to ensure a win-win solution [133,134,135].

5.5. Funding and Supervision System

The central government should provide stable budgets for PAs as a major financial resource [107] to relieve the burden on local governments. Funding is the basis for management staff’s conservation activities. They require financial support to conduct a series of relevant activities, such as training, equipment purchase, welfare provision, and conducting research. Innovative fund-raising mechanisms can be an important method for obtaining a stable source of funding for PAs in China, including appropriate absorption of social investment and establishment of a steady franchise mechanism [95,121,136,137,138,139]. Others suggest that 0.065–0.2% of China’s GDP should be allocated for guaranteeing the basic financial requirements for PAs [130], and half of the operational and management budget should be allocated to staff costs [52,140].

6. Conclusions

We explored the significance of management staff and identified the problems they faced under the current system of managing PAs in China. We also examined the reasons China’s PA management staff are often caught in a dilemma when conducting their activities. The major problems staff face includes inefficient management systems, unsound legal systems, local communities’ issues, visitors’ behavior, and underfunding. The newly proposed PNP system aims to introduce a new dimension and device for China’s conservation objectives. However, our analysis showed that many aspects could be enhanced or modified in the future. Conservation of China’s biodiversity is critical not only for the country but also for the world. Our study is inspired by the analyses of problems arising in many PAs globally. The problems faced by Chinese PA management staff can also be felt and met by staff from many other parts of the world. Therefore, this study can also guide the PA management staff in these regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and T.W.; methodology, L.C.; software, L.C.; validation, L.C. and T.W.; formal analysis, L.C. and T.W.; investigation, L.C. and T.W.; resources, L.C. and T.W.; data curation, L.C. and T.W.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, L.C. and T.W.; visualization, L.C. and T.W.; supervision, T.W.; project administration, T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research) Grant Number JP16H05641 (T.W.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Meng Yu, Yu Tao, Zuo Shan, and Su Yixun for their kind assistance in collecting Chinese publications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Akçakaya, H.R.; Andelman, S.J.; Bakarr, M.I.; Boitani, L.; Brooks, T.M.; Chanson, J.S.; Fishpool, L.D.C.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Gaston, K.J.; et al. Global Gap Analysis: Priority Regions for Expanding the Global Protected-Area Network. BioScience 2004, 54, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chape, S.; Harrison, J.; Spalding, M.; Lysenko, I. Measuring the extent and effectiveness of protected areas as an indicator for meeting global biodiversity targets. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-WCMC. State of the World’s Protected Areas: An Annual Review of Global Conservation Progress; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Loucks, C.; Ricketts, T.H.; Naidoo, R.; Lamoreux, J.; Hoekstra, J. Explaining the global pattern of protected area coverage: Relative importance of vertebrate biodiversity, human activities and agricultural suitability. J. Biogeogr. 2008, 35, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craigie, I.D.; Baillie, J.E.M.; Balmford, A.; Carbone, C.; Collen, B.; Green, R.E.; Hutton, J.M. Large mammal population declines in Africa’s protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 2221–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, O.; Fuller, R.A.; Segan, D.B.; Carwardine, J.; Brooks, T.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Di Marco, M.; Iwamura, T.; Joseph, L.; O’Grady, D.; et al. Targeting Global Protected Area Expansion for Imperiled Biodiversity. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, R.; Dhakal, M.; Polyakov, M. Valuing access to protected areas in Nepal: The case of Chitwan National Park. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, B. Research Progress in Chinese National Parks. J. Sichuan Tour. Coll. 2019, 1, 83–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Wu, J. Conservation cost of China’s nature reserves and its regional distribution. J. Nat. Resouces 2019, 34, 83–852. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Cliquet, A. Challenges for protected areas management in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andam, K.S.; Ferraro, P.J.; Pfaff, A.; Sanchez-Azofeifa, G.A.; Robalino, J.A. Measuring the effectiveness of protected area networks in reducing deforestation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16089–16094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, K.J.; Jackson, S.F.; Cantú-Salazar, L.; Cruz-Piñón, G. The ecological performance of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppa, L.N.; Loarie, S.R.; Pimm, S.L. On the protection of “protected areas”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6673–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H. Do Parks Work? Impact of Protected Areas on Land Cover Clearing. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2008, 37, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.; Chomitz, K.M. Effectiveness of strict vs. multiple use protected areas in reducing tropical forest fires: A global analysis using matching methods. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rands, M.R.W.; Adams, W.M.; Bennun, L.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Clements, A.; Coomes, D.; Entwistle, A.; Hodge, I.; Kapos, V.; Scharlemann, J.P.W.; et al. Biodiversity conservation: Challenges beyond 2010. Science 2010, 329, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopoukhine, N.; Crawhall, N.; Dudley, N.; Figgis, P.; Karibuhoye, C.; Laffoley, D.; Miranda Londoño, J.; MacKinnon, K.; Sandwith, T. Protected areas: Providing natural solutions to 21st Century challenges. Sapiens 2012, 5, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.F.; Spenceley, A.; Hvenegaard, G.; Buckley, R. Tourism and Visitor Management in Protected Areas Guidelines for Sustainability; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 27, ISBN 9782831718989. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerer, K.S.; Galt, R.E.; Buck, M.V. Globalization and Multi-spatial Trends in the Coverage of Protected-Area Conservation (1980–2000). AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2004, 33, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WDPA. February 2021 Update for the WDPA. Available online: https://livereport.protectedplanet.net/chapter-2 (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Zhang, Y.-B.; Liu, Y.-L.; Fu, J.-X.; Phillips, N.; Zhang, M.-G.; Zhang, F. Bridging the “gap” in systematic conservation planning. J. Nat. Conserv. 2016, 31, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; Hull, V.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Liu, J.; Polasky, S.; et al. Strengthening protected areas for biodiversity and ecosystem services in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skripnuk, D.F.; Samylovskaya, E.A. Human Activity and the Global Temperature of the Planet. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 180, 12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgwardt, F.; Robinson, L.; Trauner, D.; Teixeira, H.; Nogueira, A.J.A.; Lillebø, A.I.; Piet, G.; Kuemmerlen, M.; O’Higgins, T.; McDonald, H.; et al. Exploring variability in environmental impact risk from human activities across aquatic ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 1396–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, J.A. Protected areas for the 21st century: Working to provide benefits to society. Biodivers. Conserv. 1994, 3, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato, T.; Fagre, D.B. Protected Area Management. In Landscape and Land Capacity; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahi, M.; Sakai, T.; Moriya, K.; Makhdoum, M.F.; Koyama, L. Assessment of the effectiveness of protected areas management in Iran: Case study in khojir national park. Environ. Manag. 2013, 52, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverington, F.; Costa, K.L.; Pavese, H.; Lisle, A.; Hockings, M. A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coad, L.; Watson, J.E.M.; Geldmann, J.; Burgess, N.D.; Leverington, F.; Hockings, M.; Knights, K.; Di Marco, M. Widespread shortfalls in protected area resourcing undermine efforts to conserve biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.F.; Islam, K. Effectiveness of protected areas in reducing deforestation and forest fragmentation in Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilborn, R.; Arcese, P.; Borner, M.; Hando, J.; Hopcraft, G.; Loibooki, M.; Mduma, S.; Sinclair, A.R.E. Effective enforcement in a conservation area. Science 2006, 314, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beunen, R.; van Assche, K. Contested delineations: Planning, law, and the governance of protected areas. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 1285–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, C. Identifying challenges to enforcement in protected areas: Empirical insights from 15 Colombian parks. Oryx 2016, 50, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.J.; Nicoll, M.E.; Birkinshaw, C.; Harris, A.; Lewis, R.E.; Rakotomalala, D.; Ratsifandrihamanana, A.N. The rapid expansion of Madagascar’s protected area system. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 220, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, D.A.; Mascia, M.B.; Ahmadia, G.N.; Glew, L.; Lester, S.E.; Barnes, M.; Craigie, I.; Darling, E.S.; Free, C.M.; Geldmann, J.; et al. Capacity shortfalls hinder the performance of marine protected areas globally. Nature 2017, 543, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmann, J.; Coad, L.; Barnes, M.D.; Craigie, I.D.; Woodley, S.; Balmford, A.; Brooks, T.M.; Hockings, M.; Knights, K.; Mascia, M.B.; et al. A global analysis of management capacity and ecological outcomes in terrestrial protected areas. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikau, A. The evolution of the natural protected areas system in Belarus: From communism to authoritarianism. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.J.; Coleman, K.J. The Multidimensionality of Trust: Applications in Collaborative Natural Resource Management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 28, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, E.J.; Boyd, S.; Boluk, K. Stakeholder collaboration: A means to the success of rural tourism destinations? A critical evaluation of the existence of stakeholder collaboration within the Mournes, Northern Ireland. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Ruhanen, L. Power in tourism stakeholder collaborations: Power types and power holders. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopylova, S.L.; Danilina, N.R. Protected Area Staff Training: Guidelines for Planning and Management; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M.; Park, K.; Hwang, H. How managers’ job crafting reduces turnover intention: The mediating roles of role ambiguity and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A. Parks for Life: Action for Protected Areas in Europe. Georg. Wright Forum 1994, 11, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, M. A Global Register of Competences for Protected Area Practitioners; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 9782831717999. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorn, D.; Kirik, M.; Eagles, P.F.J. Evaluating Management Effectiveness of Parks and Park Systems: A Proposed Methodology. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Science and Management of Protected Areas, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 14–19 May 2000; pp. 414–430. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. Available online: https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?241530/Salonga-National-Park-Manager (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Ramer, H.; Nelson, K.C. Applying’ action situation’ concepts to public land managers’ perceptions of flowering bee lawns in urban parks. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2020, 53, 126711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, L. Are protected areas working? Wilderness 2004, 269, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Hou, M.; Wang, Z. Analysis of the Construction and Management of the Forest Nature Reserves. For. Econ. 2012, 8, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolton, S.; Burgess, N.; Hockings, M.; Higgins-Zogib, L.; Belokurov, A.; Dudley, N. Tracking Progress in Managing Protected Areas around the World; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaldi, G. Staffing Protected Areas: Defining Criteria Based on a Case Study of Eight Protected Areas in the Philippines. Suhay 2000, 4, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.Q.; Edward Grumbine, R. National parks in China: Experiments with protecting nature and human livelihoods in Yunnan province, Peoples’ Republic of China (PRC). Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, J. The Level of Financial Input in Nature Reserves of China. Environ. Conserv. 2017, 11, 53–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z. Three Principles of the Establishment of National Park System and Their Implications for China’s Practice. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 4, 401–407. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reserve Platform (In Chinese). Available online: http://www.zrbhq.cn/web/manage-archive.html (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Liu, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Pimm, S.L.; Raven, P.H.; Wang, X.; Miao, H.; Han, N. Protecting China’s biodiversity. Science 2003, 300, 1240–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Multi-designated geoparks face challenges in China’s heritage conservation. J. Geogr. Sci. 2007, 17, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Melick, D.R. Rethinking the effectiveness of public protected areas in southwestern China. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, Z.; Mallon, D.; Li, C.; Jiang, Z. Biodiversity conservation status in China’s growing protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foggin, J.M. Managing Shared Natural Heritages: Towards More Participatory Models of Protected Area Management in Western China. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2014, 17, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Miao, H.; Ouyang, Z.; Xu, W.; Zheng, H. Analyzing the effectiveness of community management in Chinese nature reserves. Biodivers. Sci. 2008, 16, 389. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Buesching, C.D.; Newman, C.; Kaneko, Y.; Xie, Z.; Macdonald, D.W. Balancing the benefits of ecotourism and development: The effects of visitor trail-use on mammals in a Protected Area in rapidly developing China. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 165, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Xu, S.S.W. Recent protected-area designation in China: An evaluation of administrative and statutory procedures. Geogr. J. 2004, 170, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Han, N. Ecotourism management in China’s nature reserves. AMBIO 2001, 30, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.N.; Green, M.J.B.B.; Paine, J.R. A Global Review of Protected Area Budgets and Staff; WCMC-World Conservation Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; Volume 39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Xiao, L. Chinese national park system pilot: Establishing path and research issues. Resour. Sci. 2017, 39, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, G.; Chen, H.; Ferretti-Gallon, K.; Innes, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G. Moving toward a greener China: Is China’s national park pilot program a solution? Land 2020, 9, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F. The practice and exploration on the establishment of national park system in China. Int. J. Geoherit. Park. 2018, 6, 1–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Guo, W. Features of geological heritage and development value in Qinling Zhongnanshan World Geopark. Int. J. Simul. Syst. Sci. Technol. 2016, 17, 12.1–12.11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Ouyang, Z.; Wang, X.; Song, M. Management of Communities in Natural Reserves: Challenge and Solution. In Proceedings of the Biodiversity Conservation and Regional Sustainable Development-Proceedings of the 4th National Workshop on Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, Wuhan, China, 21 November 2000. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Peng, L.; Yang, R. Reconstruction of Protected Area System in the Context of the Establishment of National Park System in China. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 7, 11–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Luan, X. Developing a Nature Protected Area System Composed Mainly of National Parks. For. Resour. Manag. 2017, 6, 1–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Z.; Wang, X.; Miao, H.; Han, N. Problem of Management System of China’s Nature Preservation Zones and Their Solutions. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2002, 1, 49–52. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C. Perspective on development of national park system in China. Biodivers. Sci. 2014, 22, 418. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingkang, J.; Zhi, W.; Guangqing, Z.; Siming, T.; Haili, Z. Chinese nature reserves classification standard based on IUCN protected area categories. Rural Eco-Environ. 2004, 20, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Deng, Y.; Chen, T.; Tian, C. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2016, 31, 126–133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for Assessment of Nature Reserve Management. 2017. Available online:https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/stzl/201712/t20171229_428915.shtml (accessed on 21 October 2021). (In Chinese)

- Yang, S. Why so hard to integrate and establish China’s National Parks? China Dev. Obs. 2017, 4, 49–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Haifeng, L.; Ruliang, Z. Problems and Suggestions in the Construction and Management of Yunnan Province Natural Reserve. For. Invent. Plan. 2013, 6, 64–67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Zhong, L.; Zhou, R.; Yu, H. Review of international research on national parks as an evolving knowledge domain in recent 30 years. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 244–255. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, L.; Dong, C.; Su, X.; Pang, L. Centennial Management and Planning System of National Park System in the United States of America and Its Enlightenment. World For. Res. 2019, 32, 84–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. Sticking to the Fundamental Mission of Protecting National Resources-And Commenting on the Argument that China Should Not Copy the US National Park System. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2006, 4, 1–5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mei, F. The effective management of nature reserves needs to improve the system. Environ. Prot. 2006, 52–54, 6–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Gao, F.; Wang, B.; Wang, P.; Wang, Q.; Song, H.; Yin, C. Status and suggestions on ecological protection and restoration of Qilian Mountains. Plateau Meteorol. 2017, 39, 229–234. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, S.; Zhao, X.; He, Y.; Yan, Y.; Duan, Y. Financing Mechanism for National Park Management in China. World For. Res. 2020, 33, 107–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Wen, Y. The Status Quo and Development Trend of Land Ownership Management in Nature Reserves in China. Environ. Prot. 2006, 11A, 60–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, X. Current legal system on nature reserves land tenure and use and its main problems. J. For. Econ. 2006, 26, 307–311. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L. Legal Obstacles and Solutions of the Innovation of Collective Forest Ownership in Our Country. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. 2010, 4, 26–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Shang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Research on community participation mechanism in national parks management in China. World For. Res. 2018, 31, 76–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. The Construction and management of China’s Nature Reserves in the Past forty years of reform and Opening-up: Achievements, Challenges and Prospects. China Rural Econ. 2018, 10, 1–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Farmers’ household attitude torwards ecological conservation:new findings and policy implications. Manag. World 2014, 11, 70–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. Comparison and reference of nature reserves in China and IUCN protected area management categories. World Environ. 2016, 5, 53–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, C. Research on Legal System of Right Protection of Residents of Nature Reserves in China. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2012, 33, 122–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. The public welfare building inspiration on the China’s National Park from the management experience in the U.S. National Park. Issues For. Econ. 2009, 29, 260–264. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H. Research on Chinese Tourists Uncivilized Behavior Classification and Attribution. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 30, 116–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ke, L. Discussion about the Legal Regulation of Uncivilized Travel Behavior. J. Tour. Coll. Zhejiang 2015, 11, 36–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qingdao News. Available online: https://news.qingdaonews.com/qingdao/2014-10/05/co (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Xue, X. Study on Visitors’ Behavior in Maiji Mountain Scenic Area. Tour. Manag. 2020, 11, 34–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Rushing, A.J.; Primack, R.B.; Ma, K.; Zhou, Z.Q. A Chinese approach to protected areas: A case study comparison with the United States. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Han, W.; Michael, B.; Qiu, H. Study on Eco-compensation Policy Design for Wetland-A Choice Experiment Approach. J. Nat. Resources 2016, 31, 241–251. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Wu, P.; Ge, Q.; Ning, Z. Ticket prices and revenue levels of tourist attractions in China: Spatial differentiation between prefectural units. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104214. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Guo, C.; Wu, R.; Liang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Pan, Z.; Pan, H.; Gao, J.; Jiang, M. Characteristics of and Problems in Economic Investment in Nature Reserves of China. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2016, 32, 35–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shi, J.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, T. Research on the Positioning of National Parks in China and Its Implications Based on International Experience. World For. Res. 2016, 29, 52–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wen, Y.; Li, Q.; Si, K.; Hu, C. Measurement of Conservation Costs in Qinling Nature Reserve Group. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 22, 130–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Sun, H. Primary research on establishing Protected Area System dominated by National Park. For. Constr. 2018, 3, 1–5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F.; Yan, Y.; Liu, W. Construction progress of national park system in China. Biodivers. Sci. 2019, 27, 123–127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, D.; Yan, S. Discussions on Public Welfare, State Dominance and Scientificity of National Park. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2014, 34, 257–264. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T. A Review of the Research on National Parks in China. J. Beijing For. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2018, 17, 17–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, F.; Weaver, D.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, M.F.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y. Toward an ecological civilization: Mass comprehensive ecotourism indications among domestic visitors to a Chinese wetland protected area. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 59–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Yang, S. Discussion on ecotourism management of Giant Panda National Park in China. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 143, 02036. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Xu, T.; Shi, W. Analysis of the Hot Discourse and Difficult Problems in the National Park. Environ. Prot. 2017, 45, 16–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wang, Y.; Su, L.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, D.; Sun, J.; He, S. Pilot Programs for National Park System in China: Progress, Problems and Recommendations. Policy Manag. Res. 2018, 33, 76–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fang, S. Evaluation of National Park Management Effectiveness Based on SE-DEA: A Case Study of Ten National Parks System. Mount. Res. 2020, 38, 93–104. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, S.; Schei, P. China’s Protected Areas; 1st printed; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2004; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z. Research on The National Park Management Legal System. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University, Baoding, China, 2 June 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Tang, X. Research on the establishment of national parks protection system in China. J. Beijing For. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2020, 19, 1–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Min, Q.; Jiao, W.; Liu, M.; He, S.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.S.; Li, H. Comparative study between Three-River-Source National Park of China and Jiri National Park of Korea. Acta Ecol. Sunica 2019, 39, 8271–8285. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, Q.; Hu, D. The Application and Improvement of the Party and Government. Environ. Prot. 2018, 46, 46–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Feifeng, W.; Xuefu, W. Exploring the path of Qilian Mountain National Park System Pilot Construction. Gansu Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 94–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Mei, F. Research on the land ownership of nature reserves in China. Sichuan Environ. 2007, 26, 60–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.; Zhong, L.; Liu, J.; Tang, C.; Sun, L. Establishing a national park category system in China. Resour. Sci. 2016, 38, 577–587. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.R.; Venter, O.; Fuller, R.A.; Allan, J.R.; Maxwell, S.L.; Negret, P.J.; Watson, J.E.M. Supplementary Materials for One-third of global protected land is under intense human pressure. Science 2018, 360, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tian, M.; Wang, L. Geodiversity, geoconservation and geotourism in Hong Kong Global Geopark of China. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2015, 126, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaobo, M. Ecological problems and environmental protection measures in Jiuzhaigou Scenic Area. Resour. Econ. Environ. Prot. 2016, 12, 151–162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-B.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Phillips, N.; Ma, K.-P.; Li, J.-S.; Wang, W. Integrated maps of biodiversity in the Qinling Mountains of China for expanding protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 64–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosillo, I.; Zaccarelli, N.; Semeraro, T.; Zurlini, G. The effectiveness of different conservation policies on the security of natural capital. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2009, 89, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, P.; Sun, Y. Research on Resource Protection for National Parks in China based on Goal Orientation and Value Perception. Int. J. Geoherit. Park. 2018, 6, 72–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Yu, L.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Huang, K.; Tang, S.; Feng, L.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Li, B. Article 611914 (2021) Genetic Structure and Evolutionary History of Rhinopithecus roxellana in Qinling Mountains. Cent. China. Front. Genet. 2021, 11, 611914. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K. The Study on the Legal Regulation of Ecotourism Resouces. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. A brief Analysis on the legal problems of National Parks in China. Leg. Syst. Soc. 2018, 24, 211–212. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoddousi, S.; Pintassilgo, P.; Mendes, J.; Ghoddousi, A.; Sequeira, B. Tourism and nature conservation: A case study in Golestan National Park, Iran. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, K.A.; Thornton, P.K.; De Pinho, J.R.; Sunderland, J.; Boone, R.B. Integrated modeling and its potential for resolving conflicts between conservation and people in the rangelands of East Africa. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 155–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.S.; Nkedianye, D.; Said, M.Y.; Kaelo, D.; Neselle, M.; Makui, O.; Onetu, L.; Kiruswa, S.; Kamuaro, N.O.; Kristjanson, P.; et al. Evolution of models to support community and policy action with science: Balancing pastoral livelihoods and wildlife conservation in savannas of East Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4579–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fu, B.J.; Wei, Y.P. Ecosystem services management: An integrated approach. Curr. Opin. Env. Sustain. 2015, 5, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Xu, F.; Zhang, J. Comparison of Natural Tourism Planning Administration Modes between Chinese Famous Scenic Sites and British National Parks-taking Chinese Jiuzhaigou Valley famous scenic sites and British New Forest National Park as examples. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2009, 25, 43–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T. Comparison Study of Management Model of National Park among America, Japan and Germany. Master’s Thesis, Hua Dong Normal University, Shanghai, China, 1 April 2011. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, J. Management Reform by Foreign National Parks Under the Background of New Public Management Movement: Experiences and Inspiration on China. World For. Res. 2014, 27, 44–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.; Deng, W.; Shu, C. Study on the Ways of establishing the NationaI Park System of China. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 31, 8–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Quan, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Xu, W.; Miao, H. Management effectiveness of China nature reserves Status quo assessment and countermeasures. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 20, 1739–1746. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).