Royal Land Use and Management in Beijing in the Qing Dynasty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data Processing and Research Methods

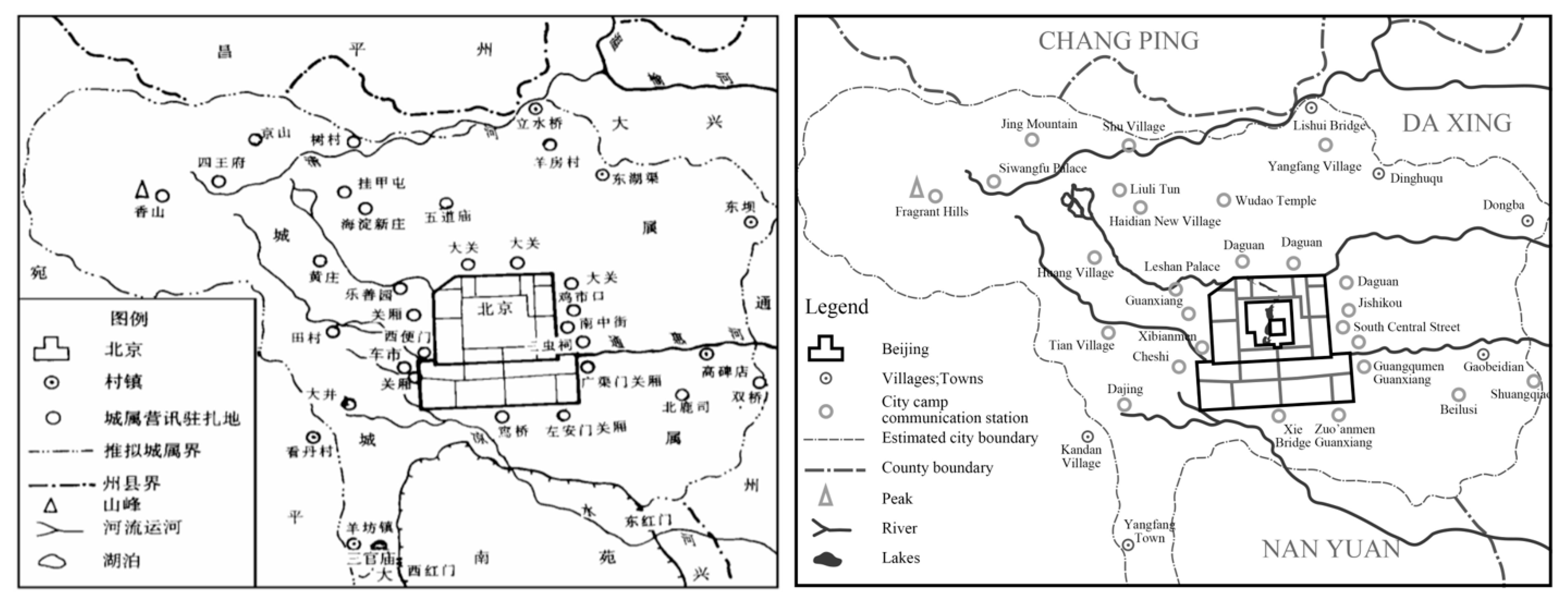

2.1. Demarcation of the Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.2.1. Map Data

2.2.2. Data of Land Management

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Semantic Analysis

2.3.2. Spatial Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Land Use

3.1.1. Analysis of the Land Use Types

3.1.2. Analysis of Land Use Types

3.1.3. Land Management Organization and Regionalization

3.2. Land Management

3.2.1. Income Analysis of Land Management

3.2.2. Expenditure Analysis of Land Management

4. Discussion

4.1. Land Planning That Balances Landscape and Economy

4.2. Spatial Distribution with the Intersection of Water and Crop

4.3. Organization Setting Focusing on Garden Management

4.4. Operation and Management Focusing on Garden Construction

4.5. Research Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Li, X.; Pei, X. Landscape Changes of the Paddy Fields in Western Beijing The Complexity and Contradiction in Its relationship with City. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 12, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Ye, M.; Shi, W.; Liu, X. Research on the social value recognition and evaluation of the Royal Garden in Beijing. Chin. Gard. 2021, 37, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Tang, Y. Mukden Gardens of the Kangxi and Qianlong Period in Qing Dynasty. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 33, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Lin, L.; Xu, Q.; Hu, C.; Zhou, M.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, K. Farmland Zoning Integrating Agricultural Multi-Functional Supply, Demand and Relationships: A Case Study of the Hangzhou Metropolitan Area, China. Land 2021, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q. Atlas of Chinese History—Volume 8—Qing Dynasty; China Map Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1987; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Qincan Picture (Qing Dynasty). Available online: http://ltfc.net/img/5d0bacf19f601784c17e5db3 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- White tower and cruise ship in Beihai Park, Beijing. Available online: https://www.vcg.com/creative/1228521408 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- The Picture of Emperor Qianlong Shooting. Available online: https://www.dpm.org.cn/collection/paint/233335.html (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Nanhaizi Country Park Phase I. Available online: http://www.bldj.com.cn/product/490.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Xiao, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhuo, K. Plant Landscape and Management System of Beijing Royal Gardens, Qing Dynasty. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 25, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, R.Z. Historical Geography of Beiping; FLTRP: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X. Study on Ancient Chinese Architectural Engineering Management and Architectural Hierarchy; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. Study on Engineering Design of West Garden and Summer Palace of Guangxu Dynasty in Tongzhi. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-de La Fuente, M.; Cabo, C.; Ordóñez, C.; Roca-Pardiñas, J. A Distance Correlation Approach for Optimum Multiscale Selection in 3D Point Cloud Classification. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G. On the administrative boundary of Beijing’s urban suburbs in the Qing Dynasty. Acta Geogr. Sin. 1999, 2, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- NLC. Ancient Atlas of Beijing; The Mapping Publishing Company: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 176–327. [Google Scholar]

- Map of Beijing and Its Environs. Available online: https://digitalatlas.asdc.sinica.edu.tw/map_detail.jsp?id=A103000148 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Yu, M. An Examination of Past News; Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2001; Volume 70, pp. 1111–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Examination of the State Organs in the Qing Dynasty (Revised Version); Xueyuan Press: Beijing, China, 2001; pp. 133–169. [Google Scholar]

- Na, L. Information Technology Support for Rural Homestay Product Innovation: Text Analysis Based on User Comments. URP 2019, 4, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yao, G. Research on tourism image perception of Huangshan Scenic Spot Based on online comments. World Reg. Stud. 2016, 25, 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- PM. Imperially Commissioned Precedents of the Imperial Household Department; Hainan Publishing House: Hainan, China, 2000; Volume 2, Fengchenyuan, pp. 147–252. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategy for Qualitative Research. Nurs. Res. 1968, 17, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- PM. Imperially Commissioned Precedents of the Imperial Household Department; Hainan Publishing House: Hainan, China, 2000; Volume 2, Jingming Garden, pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- PM. Imperially Commissioned Precedents of the Imperial Household Department; Hainan Publishing House: Hainan, China, 2000; Volume 3, Nanyuan, pp. 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- PM. Imperially Commissioned Precedents of the Imperial Household Department; Hainan Publishing House: Hainan, China, 2000; Volume 3, Qingyi Garden, pp. 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- PM. Imperially Commissioned Precedents of the Imperial Household Department; Hainan Publishing House: Hainan, China, 2000; Volume 2, Neiwufu, pp. 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wei, L.; Zhao, M. Study on the historical evolution of river landscape in Beijing. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 28, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z. Research on Qianlong Qingyi Garden and water conservancy construction in the western suburbs of Beijing. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 32, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E. Research on Beijing Traditional Urban Landscape System Based on Water Conservancy System. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, C. Dachengtian Husheng temple, Gongde temple and the evolution of Kunming Lake scenic spot (Part 2). Chin. Gard. 2015, 31, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. The evolution of marketing system and policy in the early Qing Dynasty. Hist. Res. 2000, 2, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, F. On the relationship between the finance of the interior government and the development of Tibetan Buddhist temples in the Qing Dynasty. Res. Chin. Econ. Hist. 2020, 4, 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, R. Topography, waterways and settlements near Haidian, Beijing—The geographical conditions and development process of the new cultural and educational area in the capital urban plan. Acta Geogr. Sin. 1951, Z1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Source: Yong Zheng’s “Qing Dynasty’s Hui Dian”. Volume 27. “House Department—Field and Land”. |

| 2 | Source: “Cases and Examples in Qing Dynasty’s Hui Dian”. Volume 1090 “Shuntianfu Demarcation”. |

| 3 | Source: (The Qing Dynasty) Shen, Yunlong. Guang Xu Hui Dian, Volume 89. |

| 4 | “Qing, mu, fen, li, hao, si” are units of measurement for area. (1 qing = 10 mu = 100 fen = 1000 li = 10,000 hao = 100,000 si). One mu is equal to 614 m2. |

| 5 | “Qian” is a traditional Chinese measurement of weight in East Asia. It is equal to 1⁄10 of a “Liang”. |

| Land Type I | Land Type II | Land Type III | Number | Area (%) | Area (mu) | Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-1 Farmland | II-1 Rice land | 49 | 29.4% | 7294 | 447.84 | |

| II-2 Dry land | Dry field | 25 | 1.7% | 428 | 26.29 | |

| Wheat field | 2 | 48.3% | 12,000 | 736.80 | ||

| Pasture field | 2 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| Subtotal | 79.0% | 19,722 | 1210.93 | |||

| I-2 Water land | II-3 Lotus pond | 21 | 10.8% | 2691 | 165.23 | |

| II-4 Cattail field | 3 | 2.2% | 534 | 32.76 | ||

| Subtotal | 13.0% | 3225 | 197.99 | |||

| I-3 Garden land | II-5 Vegetable land | 3 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | |

| II-6 Scenic rice land | 1 | 0.1% | 12 | 0.74 | ||

| II-7 Scenic land | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| II-8 Fruit land | 4 | 0.0% | 4 | 0.25 | ||

| II-9 Common fry land | 7 | 1.1% | 267 | 16.36 | ||

| Subtotal | 1.0% | 283 | 17.35 | |||

| I-4 Construction land | II-10 Building base land | 7 | 0.4% | 105 | 6.47 | |

| II-11 Shops | 3 | 0.6% | 146 | 8.98 | ||

| II-12 Houses | General houses | 4 | 0.4% | 94 | 5.78 | |

| Tile house | 3 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.06 | ||

| Clay house | 1 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.02 | ||

| Mud house | 1 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.05 | ||

| Uninhabited house | 1 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.01 | ||

| Subtotal | 1.0% | 348 | 21.35 | |||

| I-5 Other land | II-13 Sand land | 5 | 2.6% | 643 | 39.48 | |

| II-14 Flower field | 3 | 2.4% | 600 | 36.84 | ||

| II-15 Reed land | 1 | 0.9% | 210 | 12.90 | ||

| Subtotal | 6.0% | 1453 | 89.22 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, Y.; Liu, L. Royal Land Use and Management in Beijing in the Qing Dynasty. Land 2021, 10, 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101093

Xiao Y, Liu L. Royal Land Use and Management in Beijing in the Qing Dynasty. Land. 2021; 10(10):1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101093

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Yao, and Lian Liu. 2021. "Royal Land Use and Management in Beijing in the Qing Dynasty" Land 10, no. 10: 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101093

APA StyleXiao, Y., & Liu, L. (2021). Royal Land Use and Management in Beijing in the Qing Dynasty. Land, 10(10), 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101093