Land Grabbing and Jatropha in India: An Analysis of ‘Hyped’ Discourse on the Subject

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Hyped Discourses around Land Grabbing and Biofuels

2.1. The Land Grabbing Discourse

2.2. The Biofuel Discourse

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

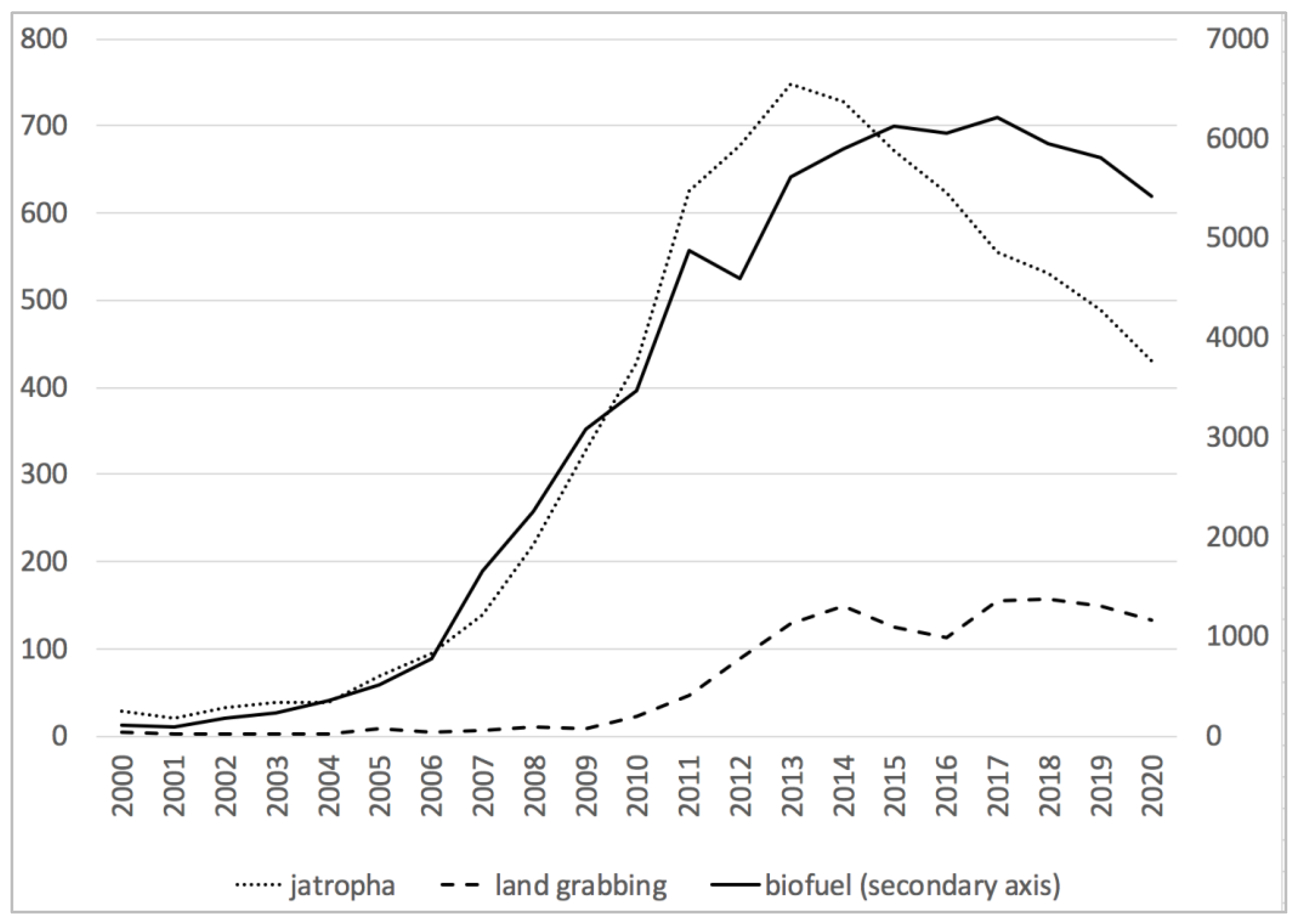

4.1. The Global Jatropha Hype and Land Grabbing

4.2. The Jatropha Hype in India and the Global Land Grabbing Discourse

4.3. Jatropha Investors in India

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Notes

- 1

- The term feedstock is being used in this paper to refer to a source of input or raw material for biofuel production.

- 2

- Note that the term ‘underdeveloped‘ in itself is contested. An alternative word to use would be ‘overexploited’. The ‘land grabbing as neo-colonialism’ narrative within the land grabbing discourse would argue that land grabbing is a new wave of ‘exploiting rich countries (with poor people)’ instead of putting it as ‘investing in poor countries’.

- 3

- This area is the so-called “intended size” of the jatropha land deals registered by the Land Matrix in 2012. The contract size of the same list of land deals is 4.3 million hectares, the actual production size is 0.2 million hectares.

- 4

- The term ‘international SME’ is used in this paper to differentiate small and medium companies with headquarters outside India from those enterprises of the same size but of Indian origin. Those are called ‘Indian SMEs’ here.

- 5

- Automobile manufacturers such as Chrysler and some airplane manufacturers looked into jatropha as a potential bio/jet fuel at the time, and held workshops to find partners for pilot projects.

- 6

- D1Oils was a leading, UK-based biofuel company that was set up in 2004 and formed a 50/50 joint venture with BP in 2007 to produce biodiesel from jatropha. BP withdrew from the JV in 2009 and in 2012 D1Oils was renamed into NEOS.

- 7

- 1 acre is equivalent to 0.4 hectares.

References

- Pedersen, R.H.; Buur, L. Beyond land grabbing. Old morals and new perspectives on contemporary investments. Geoforum 2016, 72, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; He, J. Global Land Grabbing: A Critical Review of Case Studies across the World. Land 2021, 10, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomers, A.; Gekker, A.; Schäfer, M.T. Between two hypes: Will “big data” help unravel blind spots in understanding the “global land rush?”. Geoforum 2016, 69, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sändig, J. Framing “land grabbing”: How the hype has been constructed. In Resources and Conflict; German Association for Peace and Conflict Studies (AFK): Kleve, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Borras, S.M., Jr.; Franco, J.C. Global Land Grabbing and Trajectories of Agrarian Change: A Preliminary Analysis. J. Agrar. Change 2012, 12, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.d.L.T.; McKay, B.M.; Liu, J. Beyond land grabs: New insights on land struggles and global agrarian change. Globalizations 2020, 18, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsberger, C.; German, L.; Goetz, A. “Unbundling” the biofuel promise: Querying the ability of liquid biofuels to deliver on socio-economic policy expectations. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo-Abad, C.; Althaus, H.J.; Berndes, G.; Bolwig, S.; Corbera, E.; Creutzig, F.; Garcia-Ulloa, J.; Geddes, A.; Gregg, J.S.; Haberl, H.; et al. Bioenergy production and sustainable development: Science base for policymaking remains limited. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saravanan, A.P.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Mathimani, T. A comprehensive assessment of biofuel policies in the BRICS nations: Implementation, blending target and gaps. Fuel 2020, 272, 117635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borras, S.M., Jr.; Franco, J.C.; Isakson, S.R.; Levidow, L.; Vervest, P. The rise of flex crops and commodities: Implications for research. J. Peasant. Stud. 2015, 43, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vel, J.A.C. Trading in Discursive Commodities: Biofuel Brokers’ Roles in Perpetuating the Jatropha Hype in Indonesia. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2802–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunsberger, C.; Alonso-Fradejas, A. The discursive flexibility of ‘flex crops’: Comparing oil palm and jatropha. J. Peasant. Stud. 2016, 43, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M. Peak Oil. In Companion to Environmental Studies; Castree, N., Hulme, M., Proctor, J.D., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 228–230. [Google Scholar]

- Anseeuw, W.; Alden Wily, L.; Cotula, L.; Taylor, M. Land Rights and the Rush for Land—Findings of the Global Commercial Pressures on Land Research Project; The International Land Coalition (ILC): Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Busscher, N.; Parra, C.; Vanclay, F. Environmental justice implications of land grabbing for industrial agriculture and forestry in Argentina. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 63, 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolford, W.; Borras, S.M., Jr.; Hall, R.; Scoones, I.; White, B. Governing Global Land Deals: The Role of the State in the Rush for Land. Dev. Chang. 2013, 44, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jahnavi, K.L.; Satpathy, S. Unfolding the Enigma of Dispossession in India: An Analysis of the Discourse on Land Grabbing. Sociol. Bull. 2021, 70, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levien, M. From Primitive Accumulation to Regimes of Dispossession—Six Theses on India’s Land Question. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2015, 50, 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Sud, N. Governing India’s Land. World Dev. 2014, 60, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaliganti, R.; Müller, U. Policy Discourses and Environmental Rationalities Underpinning India’s Biofuel Programme. Environ. Policy Gov. 2016, 26, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoop, E.; Arora, S. Policy Democracy: Social and Material Participation in Biodiesel Policy-Making Processes in India; SPRU Working Paper Series; University of Sussex: Sussex, UK, 2017; Volume 2017-02. [Google Scholar]

- Land Matrix. Available online: https://landmatrix.org (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Michael, A.; Baumann, M.M. India and the dialectics of domestic and international “land grabbing”. India Rev. 2016, 15, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Explore the Cambridge Dictionary. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Hajer, M.; Versteeg, W. A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2005, 7, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner Hype Cycle Gartner. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/research/methodologies/gartner-hype-cycle (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Ijabadeniyi, A.; Vanclay, F. Socially-Tolerated Practices in Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Reporting: Discourses, Displacement, and Impoverishment. Land 2020, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bailis, R.; Baka, J. Constructing Sustainable Biofuels: Governance of the Emerging Biofuel Economy. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2011, 101, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.d.L.T.; McKay, B.; Plank, C. How biofuel policies backfire: Misguided goals, inefficient mechanisms, and political-ecological blind spots. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Smalley, R.; Hall, R.; Tsikata, D. Narratives of scarcity: Framing the global land rush. Geoforum 2019, 101, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, M.E.; McKeon, N.; Borras, S.M., Jr. Land Grabbing and Global Governance: Critical Perspectives. Globalizations 2013, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edelman, M. Messy hectares: Questions about the epistemology of land grabbing data. J. Peasant. Stud. 2013, 40, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, C. Methodological reflections on ‘land grab’ databases and the ‘land grab’ literature ‘rush’. J. Peasant. Stud. 2013, 40, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Braun, J.; Meinzen-Dick, R.S. “Land Grabbing” by Foreign Investors in Developing Countries: Risks and Opportunities. In IFPRI Policy Brief; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Von Egan-Krieger, T. The “ideal market” as a normative figure of thought. Analysing the reasoning of the World Bank pro land grabbing. Real-World Econ. Rev. 2021, 95, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial, M. New Materialist Feminist Ecological Practices: La Via Campesina and Activist Environmental Work. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosset, P. Re-thinking agrarian reform, land and territory in La Via Campesina. J. Peasant. Stud. 2013, 40, 721–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomers, A.; Kaag, M. Conclusion: Beyond the global land grab hype—Ways forward in research and action. In The Global Land Grab: Beyond the Hype; Kaag, M., Zoomers, A., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, K. Doomed to fail? Why some land-based investment projects fail. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 122, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, S. From financialization to operations of capital: Historicizing and disentangling the finance–farmland-nexus. Geoforum 2016, 72, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, S. Farming as Financial Asset—Global Finance and the Making of Institutional Landscapes; Agenda Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M., Jr.; Scoones, I.; White, B.; Wolford, W. Resistance, acquiescence or incorporation? An introduction to land grabbing and political reactions ‘from below’. J. Peasant. Stud. 2015, 42, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanclay, F.; Hanna, P. Conceptualizing Company Response to Community Protest: Principles to Achieve a Social License to Operate. Land 2019, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2012; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i2801e/i2801e.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Hunsberger, C. Explaining bioenergy: Representations of jatropha in Kenya before and after disappointing results. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heinimö, J.; Junginger, M. Production and trading of biomass for energy—An overview of the global status. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, 1310–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ariza-Montobbio, P.; Lele, S.; Kallis, G.; Martinez-Alier, J. The political ecology of Jatropha plantations for biodiesel in Tamil Nadu, India. J. Peasant. Stud. 2010, 37, 875–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, I.G. Degraded forest, degraded land and the development of industrial tree plantations in Laos. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2014, 35, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, J. The Political Construction of Wasteland: Governmentality, Land Acquisition and Social Inequality in South India. Dev. Chang. 2013, 44, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner, A.; Bartels, L.E.; Windhaber, M.; Fritz, S.; See, L.; Politti, E.; Hochleithner, S. Constructing landscapes of value: Capitalist investment for the acquisition of marginal or unused land—The case of Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D. Land grabs, land control, and Southeast Asian crop booms. J. Peasant. Stud. 2011, 38, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotula, L. The international political economy of the global land rush: A critical appraisal of trends, scale, geography and drivers. J. Peasant. Stud. 2012, 39, 649–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillon, S. Flexible for whom? Flex crops, crises, fixes and the politics of exchanging use values in US corn production. J. Peasant. Stud. 2016, 43, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Reyes, J.; Sandwell, K. Flex Crops: A Primer; Transnational Institute (TNI): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Adamczewski, A.; Jamin, J.-Y.; Burnod, P.; Boutout Ly, E.H.; Tonneau, J.-P. Terre, eau et capitaux: Investissements ou accaparements fonciers à l’Office du Niger? Cah. Agric. 2013, 22, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.A.; Kuusaana, E.D.; Ahmed, A.; Campion, B.B. Land dispossessions and water appropriations: Political ecology of land and water grabs in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borras, S.M., Jr.; Fig, D.; Suárez, S.M. The politics of agrofuels and mega-land and water deals: Insights from the ProCana case, Mozambique. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 2011, 38, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachage, C.; Baha, B. Accumulation by Land Dispossession and Labour Devaluation in Tanzania, the Case of Biofuel and Forestry Investments in Kilwa and Kilolo; Land Rights Research and Resources Institute: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kirst, S. “Chiefs do not talk law, most of them talk power.” Traditional authorities in conflicts over land grabbing in Ghana. Can. J. Afr. Stud. 2020, 54, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavers, T. ‘Land grab’ as development strategy? The political economy of agricultural investment in Ethiopia. J. Peasant. Stud. 2012, 39, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCarthy, J.F.; Vel, J.A.C.; Afiff, S. Trajectories of land acquisition and enclosure: Development schemes, virtual land grabs, and green acquisitions in Indonesia’s Outer Islands. J. Peasant. Stud. 2012, 39, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcome to VOSviewer. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- GEXSI. Global Market Study on Jatropha, Final Report; GEXSI: London, UK; Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Edrisi, S.A.; Dubey, R.K.; Tripathi, V.; Bakshi, M.; Srivastava, P.; Jamil, S.; Singh, H.B.; Singh, N.; Abhilash, P.C. Jatropha curcas L.: A crucified plant waiting for resurgence. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Maltitz, G.; Gasparatos, A.; Fabricius, C. The Rise, Fall and Potential Resilience Benefits of Jatropha in Southern Africa. Sustainability 2014, 6, 3615–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Achten, W.; Sharma, N.; Muys, B.; Mathijs, E.; Vantomme, P. Opportunities and Constraints of Promoting New Tree Crops—Lessons Learned from Jatropha. Sustainability 2014, 6, 3213–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Achten, W.; Nielsen, L.R.; Aerts, R.; Lengkeek, A.G.; Kjær, E.D.; Trabucco, A.; Hansen, J.K.; Maes, W.H.; Graudal, L.; Akinnifesi, F.K.; et al. Towards domestication of Jatropha curcas. Biofuels 2010, 1, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walmsley, D.C.; Bailis, R.; Klein, A.-M. A Global Synthesis of Jatropha Cultivation: Insights into Land Use Change and Management Practices. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 8993–9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Openshaw, K. A review of Jatropha curcas: An oil plant of unfulfilled promise. Biomass Bioenergy 2000, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.; Edinger, R.; Becker, K. A concept for simultaneous wasteland reclamation, fuel production, and socio-economic development in degraded areas in India: Need, potential and perspectives of Jatropha plantations. Nat. Resour. Forum 2005, 29, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BioZio. Comprehensive Jatropha Report: A Detailed Report on the Jatropha Industry; BioZio: Chennai, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Gonzáles, N.F. International experiences with the cultivation of Jatropha curcas for biodiesel production. Energy 2016, 112, 1245–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRAIN. The Global Farmland Grab in 2016: How Big, How Bad? GRAIN: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eijck, J.; Romijn, H.; Balkema, A.; Faaij, A. Global experience with jatropha cultivation for bioenergy: An assessment of socio-economic and environmental aspects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 869–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, N.; Hildebrandt, T.; Moser, C.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Averdunk, K.; Bailis, R.; Barua, K.; Burritt, R.; Groeneveld, J.; Klein, A.-M.; et al. Insights into Jatropha Projects Worldwide; Leuphana University of Lüneburg: Lüneburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Simandjuntak, D. Riding the Hype: The Role of State-Owned Enterprise Elite Actors in the Promotion of Jatropha in Indonesia. Sustainability 2014, 6, 3780–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, F.; Raghavan, K.; De Jongh, J.; Huffman, D. Jatropha for Local Development after the Hype; Hivos: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, P.; Wu, S. The Extraordinary Collapse of Jatropha as a Global Biofuel. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 7114–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Bediako, R.; Otsuki, K.; Zoomers, A.; Amsalu, A. Global Investment Failures and Transformations: A Review of Hyped Jatropha Spaces. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IEA Data and Statistics: Explore Energy Data by Category, Indicator, Country or Region. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/?country=WORLD&fuel=CO2%20emissions&indicator=CO2BySector (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- IEA India. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/IND (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Gunatilake, H.; Roland-Holst, D.; Sugiyarto, G.; Baka, J. Energy Security and Economics of Indian Biofuel Strategy in a Global Context; Working Paper Series, No. 269; ADB Economics: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2011; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés Rodríguez, O.; Vázquez, A.; Muñoz Gamboa, C. Drivers and Consequences of the First Jatropha curcas Plantations in Mexico. Sustainability 2014, 6, 3732–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, A.; Halvorsen, K.E.; Eastmond-Spencer, A.; Sweitz, S.R. Sustainable Development for Whom and How? Exploring the Gaps between Popular Discourses and Ground Reality Using the Mexican Jatropha Biodiesel Case. Environ. Manag. 2017, 59, 912–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairless, D. The little shrub that could—Maybe. Nat. News Feature 2007, 447, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jatropha Seeds Yield Little Hope for India’s Oil Dream—Pilot Program’s Output is Below Expectations, but Coming Changes Could Make Plans Viable. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/jatropha-seeds-yield-little-hope-for-india-s-oil-dream-1.495519 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- De Hoop, E.; Arora, S. How Policy Marginalizes Diversity: Politics of Knowledge in India’s Biodiesel Promotion. Sci. Cult. 2020, 30, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GoI. Report of the Committee on the Development of Bio-Fuel; Government of India, Planning Commission: New Delhi, India, 2003.

- FAO; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020—Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy; IFAD: Rome, Italy; UNICEF: Rome, Italy; WFP: Rome, Italy; WHO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baka, J. What wastelands? A critique of biofuel policy discourse in South India. Geoforum 2014, 54, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, J. Making Space for Energy: Wasteland Development, Enclosures, and Energy Dispossessions. Antipode 2017, 49, 977–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K.S. Global resource grabs, agribusiness concentration and the smallholder: Two West African case studies. J. Peasant. Stud. 2012, 39, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Hall, R.; Borras, S.M., Jr.; White, B.; Wolford, W. The politics of evidence: Methodologies for understanding the global land rush. J. Peasant. Stud. 2013, 40, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Axelsson, L.; Franzen, M.; Ostwald, M.; Berndes, G.; Lakshmi, G.; Ravindranath, N.H. Jatropha cultivation in southern India: Assessing farmers’ experiences. Biofuels Bioprod. Bioref. 2012, 6, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, J.; Bailis, R. Wasteland energy-scapes: A comparative energy flow analysis of India’s biofuel and biomass economies. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 108, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biswas, K.P.; Pohit, S. What ails India’s biodiesel programme? Energy Policy 2013, 52, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlater, K.M.; Kandlikar, M. Land use and second-generation biofuel feedstocks: The unconsidered impacts of Jatropha biodiesel in Rajasthan, India. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 3404–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, M.C.; Sudhakaran, R. Biofuels: Opportunities and challenges in India. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.—Plant 2009, 45, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoop, E.; Arora, S. Material meanings: ‘waste’ as a performative category of land in colonial India. J. Hist. Geogr. 2017, 55, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, S. Losing the Plot—The Threats to Community Land and the Rural Poor through the Spread of the Biofuel Jatropha in India; Friends of the Earth Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Awasthi, A.; Singh, R.P.; Tewari, S. Merging the margins for beneficial biofuels: An Indian perspective. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering—Sustainable Bioresources for the Emerging Bioeconomy; Kataki, R., Pandey, A., Khanal, S.K., Pant, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Levien, M. Dispossession without Development: Land Grabs in Neoliberal India; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gmünder, S.M.; Zah, R.; Bhatacharjee, S.; Classen, M.; Mukherjee, P.; Widmer, R. Life cycle assessment of village electrification based on straight jatropha oil in Chhattisgarh, India. Biomass Bioenergy 2010, 34, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inter-/Transnational Corporations (5) | Indian Corporations (42) | |

|---|---|---|

| Larger Companies (8) | SMEs (34) | |

| ADM | Bharat Petroleum | Adi Biotech, Armaco, Bharat Renewable Energy Ltd. (BREL), Bulk Agro India, CleanStar Energy, Cosmos Green, D1 Mohan Bio Oils, D1 Williamson Magor, Dharani Sugars, Dr. MGR Jatropower Bio-trading, Labland Biodiesel, Mission Biofuels India, Mohan Breweries, Nandan Biomatrix, Naturol Bioenergy, Noble Horticulture Farm, Pandlan Estates, Purandhar Agro and Biofuels, Renulkashmi Agro-Industries, Riverway Agro Products, Shirke Energy, Shiva Distilleries, Society for Rural Initiatives for Promotion of Herbals, Southern Biofe Biofuels, Southern Online Biotechnologies, T. Shivaleeka Biotech, Tree Oils India, Upkar Biodiesel, V. Bakthavatchalam, Vatic International Business |

| Bayer CropScience | Bannari Amman Group | |

| Daimler | Hindustan Petroleum | |

| D1 Oils | Hazel Mercantile | |

| GM | Indian Oil | |

| Reliance | ||

| International SMEs (8) | Shapoorji Pallonji | |

| Agriom Energea FE Global Clean Energy JatroPower JatroSolutions JOil Mission NewEnergy SGB Biofuels | Williamson Magor | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trebbin, A. Land Grabbing and Jatropha in India: An Analysis of ‘Hyped’ Discourse on the Subject. Land 2021, 10, 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101063

Trebbin A. Land Grabbing and Jatropha in India: An Analysis of ‘Hyped’ Discourse on the Subject. Land. 2021; 10(10):1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101063

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrebbin, Anika. 2021. "Land Grabbing and Jatropha in India: An Analysis of ‘Hyped’ Discourse on the Subject" Land 10, no. 10: 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101063

APA StyleTrebbin, A. (2021). Land Grabbing and Jatropha in India: An Analysis of ‘Hyped’ Discourse on the Subject. Land, 10(10), 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101063