Abstract

Within the ecosystem services framework, cultural ecosystem services (CES) have rarely been applied in state-wide surveys of protected area networks. Through a review of available data and online research, we present 22 potential proxy indicators of non-material benefits people may obtain from nature in Natura sites in Greece. Despite the limitations due to data scarcity, this first distance-based study screens a recently expanded protected area system (446 Natura sites) providing steps towards an initial CES capacity review, site prioritization and data gap screening. Results identify hot spot Natura sites for CES values and wider areas of importance for the supply of CES. Additionally, a risk analysis mapping exercise explores the potential risk of conflict in the Natura sites, due to proposed wind farm developments. Α number of sites that may suffer serious degradation of CES values due to the large number of proposed wind turbines within these protected areas is identified, with 26% of Greece’s Natura sites showing serious and high risk of degradation of their aesthetic values. Screening-level survey exercises such as these may play an important role in advancing conservation effectiveness by increasing the appreciation of the multiple benefits provided by Natura protected areas. Based on this review, we propose recommendations through an adaptive approach to CES inventory and research initiatives in the protected area network.

1. Introduction

Many Natura sites have high cultural values and these have often been overlooked and ignored within biodiversity conservation [1]. In the ecosystem services (ES) framework, the non-material benefits nature provides to humans are analyzed through cultural ecosystem services (CES) [2,3]. CES include a wide range of benefits that the natural environment provides for people; direct and indirect values pertaining to culture, heritage, education, recreation, tourism, aesthetic, religious and spiritual attributes. Various CES analyses have been utilized in many applications, including studies of landscapes and seascapes [4,5,6,7]. However, few CES applications focus on protected area networks [8,9,10], and CES indicators at these broader scales, such as regional scales, are variously defined and not consistent [11,12,13,14].

Building indicators for assessing CES has proven challenging [15,16]. Standardized CES indicators should provide aggregated information on the non-material benefits available to humans from nature to help summarize and evaluate complex human–environmental relationships [17]. Compared to other ecosystem services approaches, CES are especially difficult to quantify [18], often differentially interpreted by different beneficiaries and stakeholders [19] and sometimes hard to depict in cartography [20,21]. They are, therefore, generally poorly represented in existing ecosystem service assessments [11,22,23]. Recently, controversy was sparked with respect to a proposal to actually omit CES per se from routine ecosystem services valuations [24,25]. However, despite differing opinions and methodological challenges, the ecosystem services framework is now a widely applied standard assessment platform and it has shown to be effective in mission-orientated evaluation, communication and policy support [7,26]. There is little doubt that CES applications will continue to be developed, tested and promoted, even at the challenging broad spatial scales of geographical regions and nations (e.g., [9,27,28,29]).

Despite its growing pains, CES have recently been shown to be important and useful in protected areas, especially because cultural conditions, including local communities, local world-views and policy directives create and sustain protected areas [8,9,30]. Protecting CES in protected areas is often directly associated with maintaining human wellbeing and sustainability. The expectations placed on protected areas by a variety of stakeholders have increased beyond classical biodiversity demands, as these “sanctuaries” are becoming testing grounds for sustainability [31,32,33,34]. The Natura 2000 protected area network, the EU’s conservation centerpiece, has seen increased interest for more cultural and sustainability demands [35,36]. In this context, conservation and management plans must go beyond specific biodiversity targets.

Conservation in protected areas has been a difficult undertaking in the Mediterranean EU states [37]. Mediterranean protected areas usually have multiple functions, and conservation management is often a perpetual challenge. The Mediterranean’s landscapes have evolved as complex socio-ecological systems with a strong interdependence among past and present land-uses [38]. The ecological integrity of many Natura sites is strongly influenced by centuries-old human–nature interactions that affect landscape-scale dynamics and are driven by the life-ways and attitudes of people, especially local communities [19,39,40]. The number of designated protected areas has expanded quickly; in Greece, for example, 28% of land territory has been designated as Natura sites in less than three decades. However, Protected Area conservation management has received much “bad press” in Greece; there have been serious organizational difficulties and noticeable shortcomings [41,42]. Greece’s protected areas, in need of reform and effective conservation actions, may provide a good model to explore CES protected area network assessments.

In Greece, CES applications are new and rarely used in protected area management. Among the recently published National Mapping and Ecosystem Services Assessment (MAES) initiative [43], few indicators track a breadth of possible CES attributes. Kokkoris and colleagues in 2020 [43] emphasize that new CES indicators must be tested and developed to complement the initial proposed national indicators. Baseline knowledge gaps and data scarcity have long been known to be serious hurdles for effectively protecting the Natura sites in Greece [44]. Greece’s protected area system still shows developmental difficulties [45]. An example of this includes recent policy changes: in May 2020, a new Modernization of the Environmental Legislation bill was passed (Law 4685/2020), which drew strong resistance from many environmentalists [46]. Some of the difficulties in Greece may be related to the post-2008 economic recession, while others to long-term land-use conflicts and competition for a variety of resources and poor government coordination [47,48]. Greece has not developed an integrated national protected area monitoring system [48], and the full set of values associated with the protected sites are usually poorly acknowledged. Although some of Greece’s efforts for species or habitat preservation are commendable [42], many other aspects such as the protection of its designated Areas of Outstanding Beauty, wilderness areas and cultural landscapes are considered inadequate, and preservation measures are poorly enforced [49,50,51,52,53]. The continuing degradation of Greece’s protected areas, including its scenic and iconic landscapes, could have serious social and economic impacts.

Greece’s protected areas are of outstanding value for biodiversity, but focusing solely on biodiversity is plainly not enough for successful conservation. In Greece, a variety of CES should be inventoried and assessed as soon as possible, to enable better integration of an array of services and benefits within the national ES-based assessment framework [43]. Understanding and communicating the cultural aspects in protected areas is important for promoting a more transparent and socially sensitive science–policy interface [36,54], and one reason for socially sensitive steps in conservation is conflict risk management [55].

In this study we undertake a CES geographical survey in Greece and explore its practical use in a case study where potential conflict may exist with proposed industrial wind farm developments in the Natura 2000 protected area network. In an attempt to provide a rapid broad-scale CES application under currently data-scarce conditions, we utilize proxy indicators. Proxies provide indirect measures that approximate or may represent a phenomenon in the absence of a direct measure, and they are now widely used in the social sciences and in interdisciplinary research [56]. We evaluate the Natura 2000 network with reference to the cultural services provided by the Natura site qualities using available and accessible databases and metadata from recent screening-level surveys and online research. Approaching CES evaluation through this “low hanging fruit” procedure (i.e., rapid, easily available data-gathering) provided an initial screening of potential indicators, in an attempt to introduce the concept of CES and its practical uses in the country’s protected area system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Protected Area System

Greece’s protected area system is mainly based on areas designated under the EU Natura 2000 ecological network [57]. There are other “protected areas” such as the former no-hunting zones (now called “wildlife refuges”), many of which are not within the Natura 2000 network. Older designated natural heritage protected areas (such as the National Parks and Aesthetic Forests) are usually within the network. In practice, few management and conservation interventions are made with concern for designated natural heritage areas outside the Natura 2000 network. During the last decades, institutional biodiversity management focus has been on Natura 2000, especially since EU policies monitor the country’s progress [58]. Greece’s Natura 2000 network includes sites that are characterized for their avifauna as Special Protection Areas (SPAs) and sites that are characterized as Special Areas for Conservation (SACs) for their habitat types, flora and other fauna species under the EU Directives 2009/147 and 92/43, respectively. In combination, Greece currently maintains 446 such Natura sites (some SPAs and SACs partly overlapping) and some newly delineated areas still considered Sites of Community Interest (SCIs) or proposed SCIs. The Natura 2000 network has been expanding in Greece since the first listing of sites in 1995, after the inclusion of several new proposed SCIs in late 2017 (including many new Marine sites).

2.2. Preparatory Actions and CES Indicator Selection

The initial overview of potential CES indicators involved the following steps:

- Literature review for CES indicators in Greece: building on a potential list of CES indicators used for the site-level assessment of ES supply at mountainous Natura sites in Greece [59] and indicators proposed for the National MAES indicators [43].

- Compilation of data and GIS map layers pertaining to the Natura sites in Greece: using the Natura 2000 Standard Data Forms and monitoring results [60] and spatial data for habitat types following the European Environment Agency (EEA) guidelines [61]; a detailed ecosystem-type mapping for Greece is an ongoing procedure of the LIFE-IP 4 NATURA project [43].

- Protected-area cultural attributes data matrix and associated metadata pertaining to Natura 2000 “culturalness” developed by Vlami and colleagues in 2017 [62].

- Exploration of data availability and quality with respect to the state-wide relevance of national indicators for MAES applications based on the review by Dimopoulos and colleagues in 2017 [44] and on datasets freely available by state authorities (links provided in Kokkoris and colleagues in 2020 [43]).

- Selection and review of indicators responsive to policy and conservation management needs: using the guidance provided by Maes and colleagues [63,64] and in combination with the targets of the Greek Biodiversity Strategy [65]; each indicator was examined for policy relevance and related to the Common International Classification for Ecosystem Services (CICES) [66].

- Initial assessment of potential indicators: using a simple scaling method, based on van Oudenhoven [67], pertaining to salience, credibility, legitimacy and feasibility. Each potential CES indicator was scored by the co-authors as: 1—very low, 2—low, 3—medium, 4—high, 5—ready for use. This overview of uncertainty of use allowed the co-authors to decide on a final selection of potential indicators and to explore uncertainty and applicability issues. This screening of indicators is identical to building the national MAES indicators [43].

2.3. Database and Mapping Applications

For the identification and mapping of features within each protected area we applied the work method developed by Vlami and colleagues in 2017 [62] to create a relational database that has been linked to Natura sites’ spatial data (site polygons) using a Geographical Information System (QGIS) platform [68]. To produce gradient hotspot maps, the total value of each area (site) has been linked to the relevant Natura 2000 spatial data (protected area vector polygons). Using the QGIS platform, the protected sites of Greece were differentiated and thematically presented as hotspots in gradient maps (i.e., hot = high total attribute sum of scores; cold = low total attribute sum of scores). Heat maps were also produced by using the centroids of each Natura site. Each centroid has been assigned the total site value, and this attribute information was used as the weighting factor for each site. The active radius used for creating heat maps varied with the particular use of each map. Combined indicators’ gradient and heat maps are created by summing standardized (0–1) values of the relevant categories; gradient maps thematically represented the result to a five-rating scale (i.e., very low, low, moderate, high, very high); heat maps depict the vicinity (concentration in space) of Natura sites throughout the Greek territory.

A challenge in this application was dealing with poor data quality, data scarcity and inconsistency in data quality. In the initial survey, efforts were taken not to complicate or confound the collected data attributes through integrative techniques, since the attributes and the quality of data accuracy in the matrix is heterogeneous (i.e., with varying degrees of quality and precision). The evaluation by the authors assisted in checking the relative quality of the data used, by evaluating this through the co-authors’ expert judgment.

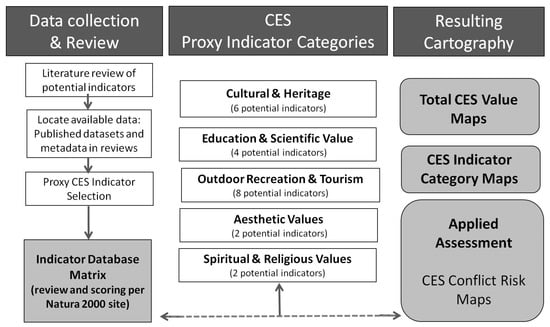

Based on the literature review, five categories of potential proxy indicators were decided upon (Figure 1, Table 1). Specific indicators were chosen and maps were developed for nearly all of them.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the cultural ecosystem services (CES) rapid assessment approach.

Table 1.

List of 22 CES proxy indicators selected in this application.

Table 1 presents the 22 initial potential indicators (proxy indicators) selected and defined in this study. We employed Nowak’s indicator definition here (Nowak 1977, in Czyż, 2017 [69]), where an indicator signals for the occurrence of another property called an indicatum. Thus, we describe the indicatum in each proxy and the rationale of selecting the potential indicators. For each potential indicator the matching Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CISES) code is also provided.

2.4. Wind Farm Conflict Risk Mapping Exercise

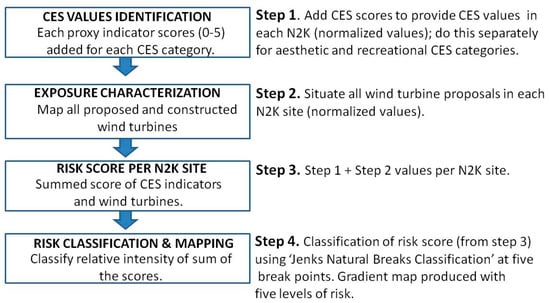

Potential conflict with wind farm development is used here as a case study of risk screening based on the premise that if a large number of wind turbines are developed in a Natura site there is increased risk of reducing CES values. An unprecedented number of wind turbines are planned in Greece, with proposals increasing especially after 2010. The Hellenic government regulatory agency [70] documents that 3045 turbines are already erected (holding operation license), 8215 turbines have been approved through a production license and another 5636 turbines are currently under evaluation. All the wind turbines were mapped in a GIS and we explore the risk of degradation to two CES categories (aesthetic and recreation categories) in relation to the numbers of wind turbines proposed in each Natura site. The simple summation of CES scores and classification of risk mapping is a straightforward process to depict the relative risk of reducing CES values by industrial wind farms (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Process of risk classification for wind turbine density per Natura site in relation to CES categories.

As a result, sites are sorted in five prescribed classes per CES category in terms of relative risk: high, serious, moderate, low, no or minimum risk. The definitions follow the application of a gradient of potential risk. This classification is based on a simple numerical taxonomic technique known as the “Jenks optimization method” or “goodness of variance fit” (GVF) [71]. This method is designed to optimize the arrangement of a set of values into so-called natural gradient classes (i.e., the most optimal class range distributed within a data set). This classification seeks to minimize the average deviation from the class while maximizing the deviation from the means of the other groups [72,73]. In the GIS cartographical application we arbitrarily chose five classes to depict a wider spread of relative risk [71] among the hundreds of Natura sites that are assessed.

3. Results

3.1. Mapping the Distribution and Intensity of Proxy Indicators

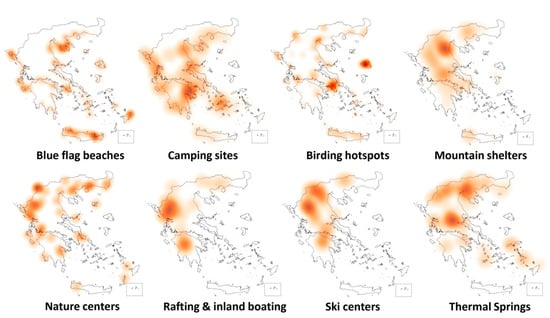

At the state-wide level, certain proxies of the non-material benefits and services ecosystems may provide to humans were reviewed for the first time. Some of these are concentrated in particular wider areas or regions. A cumulative expression of these data can be provided through heat maps in order to review the distribution patterns (Figure 3). Some of these data are dynamic, i.e., they may change through time as human interest is discovered or alters through time (bird watching hotspots, rafting courses, designated “Blue Flag” beaches, etc.), while others are static expressions of a particular supply of cultural ecosystem services provided directly by particular ecosystems (e.g., natural spa attractions at thermal springs). To an extent, this state-wide review is influenced by data availability; there is more data for particular proxies, such as outdoor athletic activities and coastal attractions (compare data gap maps below).

Figure 3.

Example of heat maps providing generalization of selected proxy indicators.

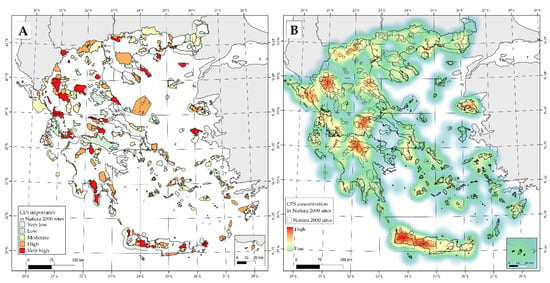

3.2. Cumulative Results at the State-Wide Natura 2000 Level

The cumulative depictions of the scores gained from each of the selected proxy indicators provide a CES total “value” for each Natura site. Utilizing five-class boundary classes, we produced gradient maps that showcase the top-scored CES-valued sites (Figure 4A). This prioritization is also expressed using a heat map to identify wider areas of outstanding importance due to a high concentration of CES-valued Natura sites. The heat maps depict highly scored sites (site clusters creating heat areas) that are distributed in close proximity. The heat map approach (Figure 4B) is important for identifying wider areas that concentrate many high-profile Natura sites; these include areas such as Crete (Samaria N.P., Ida Mountain etc.), the northern Peloponnese (Chelmos mountains etc.), eastern-central Greece’s mountains (Parnassus, Ghiona, Vardousia, Oiti mountains etc.), the Northern Pindus mountains and the Kalamas river delta and adjacent Kerkyra island, etc. The heat maps depict nearly a dozen such high-ranking wider areas. All of them are of outstanding biodiversity value (and have a high concentration of Natura sites). In contrast, some areas of relative data scarcity and geographic isolation (or distance) from neighboring Natura sites are not highlighted in this assessment (e.g., parts of inland Peloponnese, Boeotia, Thessaly and several islands and islets). Although these relatively isolated sites have relatively less CES significance in this survey, this does not mean they are generally less important in a cultural sense; they are at a distance from clusters of high-ranking sites.

Figure 4.

Cumulative CES importance gradient map (A) and heat map (B) per Natura site, including all five CES indicator categories as developed in the current inventory and assessment. The heat map uses a 40 km radius to define levels of relative concentration of CES highly-valued sites.

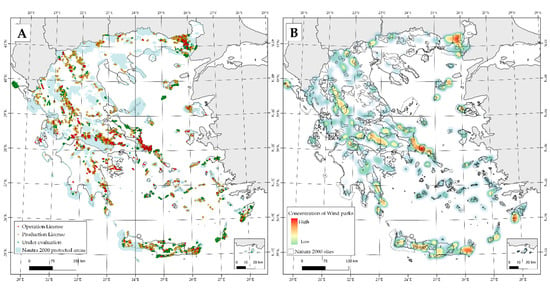

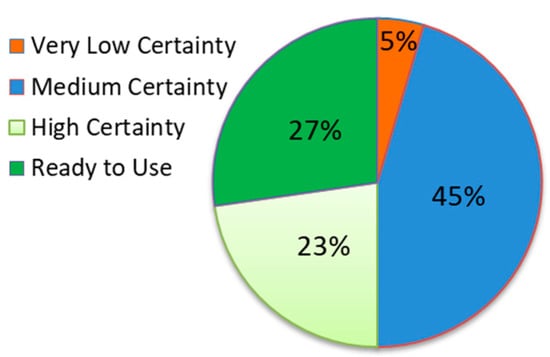

3.3. Wind Farm Conflict Risk

The Hellenic government regulatory agency (RAE 2020 [70]) documents that although currently 3045 turbines are already erected, many more are proposed (16,896 in total) (Figure 5A). The actual proposed number and proximity of wind turbines is used as a criterion that derives an initial screening of potentially increasing cumulative effects (i.e., pressures) on landscapes. This is depicted here with a heat map, based on a 15 km radius from each proposed wind turbine. The radius is based on our assumption of the potential visual impact and associated infrastructure change of a typical industrial wind farm, which usually has several wind turbines, with turbine towers usually exceeding 50 m in height. Using this arbitrary radius distance (15 km) of potential influence may also accommodate the visual perception of both wind turbines and associated supportive structures such as new roads, power lines and supportive terminals (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Concentration of wind farms showing the position of constructed wind turbines (with operation and production license) and proposed wind turbines under government evaluation; 16,896 proposed industrial wind turbines are mapped (A). The heat map produced by the concentration intensity of wind farms uses a 15 km radius (around each mapped turbine) to define levels of relative wind turbine concentration (B). Source: State-wide review from RAE [70], accessed: 29 May 2020.

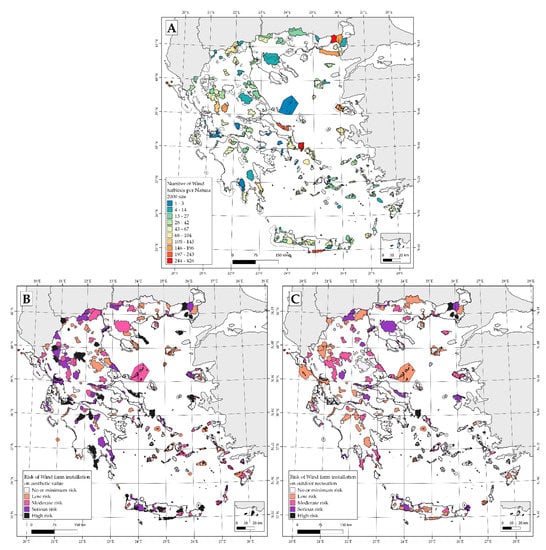

The number of wind turbines proposed for each Natura site is also depicted in a gradient map solely for each Natura site (Figure 6A). Based on the relative levels of occurrence of all proposed wind farm installations within the terrestrial Natura sites, the levels of concentration at each site are classified using the five-class Jenks optimization method application. This helps showcase where the highest potential conflicts may take place relative to the particular CES values scored at each site. In total, 115 Natura sites where shown to have a high and serious risk of conflict with planned wind farms based on their aesthetic values (Figure 6B). Furthermore, 24 sites fall into high and serious risk based on their outdoor recreation values (Figure 6C). A breakdown of the percentage of all sites is depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Wind farm risk analysis in Natura sites: total wind farms per site, both operating and proposed (A). Potential impact risk map on aesthetic values (B) and on outdoor recreation values (C). The five-point risk scale follows a simple numerical classification technique (see methods section). Marine-only Natura sites are excluded.

Figure 7.

Sites showing the risk of degradation to CES values due to proposed wind turbine developments in Greece’s Natura 2000 network. Percentage of sites with potential risk to aesthetic values (A) and recreational values (B). Specific Natura site conflict risk (color codes) are as mapped in Figure 6 B and 6 C respectively.

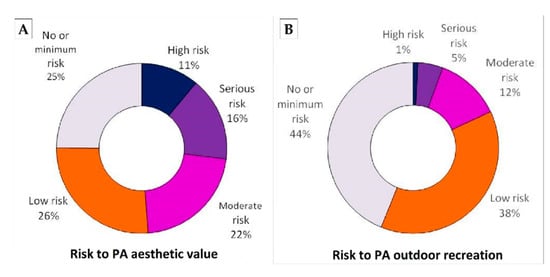

3.4. Uncertainties and Data Gaps

One of the major difficulties of testing proxy indicators at this initial stage of a state-wide screening is verifying the certainty and overall usefulness of particular indicators. In our work so far, about half of the proxy indicators seem to satisfy readiness of use with rather high certainty (based on the authors’ expert judgment). Nearly half the proxy indicators were registered as having “medium certainty” (Figure 8). Since this enterprise is very important for future progress, we urge further study for validation. One of the obstacles to validation is data scarcity concerning various complementary or equivalent indicators for comparisons and further testing.

Figure 8.

Distribution of 22 proxy indicators used in this study in terms of the level of certainty assessed by the authors’ expert judgement (from Table 1).

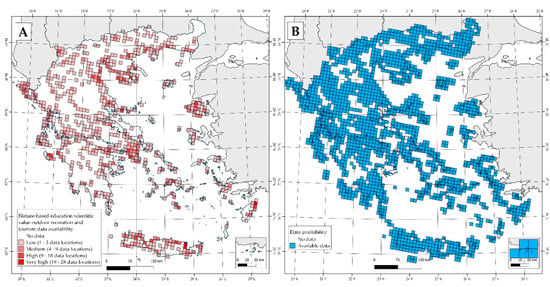

Greece is a relatively data-scarce country in terms of accessible inventories of various natural and cultural attributes concerning its protected areas. Of course, there are outstanding “honey-pot” locations famous for tourism and biodiversity interest that provide much data and produce repeated references to certain sites [62]. This is apparent when mapping the available data in this review using the European Environment Agency (EEA) 10 × 10 km reference grid. Data availability after the combination of two CES categories shows a concentration in such popular sites and along the coast (Figure 9A). The total data availability of the five CES categories assessed in the study is given (Figure 9B). The cumulative map gives the impression that most of the country is well-covered; but, one should keep in mind the large number of proxy indicators used (22) and the 10 × 10 reference grid that also gives the impression that wider areas are covered. Areas not covered by any available data are rather sparse and predominantly in inland regions.

Figure 9.

Example of gap analysis using the European Environment Agency (EEA) 10 × 10 km reference grid. (A) Data availability after the combination of two categories; i.e., nature-based education and scientific value and outdoor recreation and tourism. (B) Total data availability of the five CES categories assessed in the study.

4. Discussion

4.1. Achievements and Context

In Greece, protected areas have never been evaluated for their cultural benefits or the CES they may provide to people. There are few studies with concern for aspects relevant to CES [43,44,62,74,75]. In this rather data-scarce and understudied conservation arena a rapid assessment for CES in Natura sites is an important unmet need.

So far, this rapid survey has provided the following steps for CES application at the protected area network scale in Greece:

- Available data were compiled to build an initial CES database per Natura site, providing an initial inventory. This work is exploratory since only easily accessible proxy indicators were selected as potential indicators; these are meant to be tested and expanded within future research investments. The current fit-for-purpose review follows the methodology and complements Greece’s National Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystem Services (MAES) indicators approach [43].

- By focusing on the state’s protected area network we can identify priority sites of outstanding CES values or sites “at risk”, i.e., an initial screening for prioritization “hot spots”. The resulting cartography provides results for a continuing discourse on CES and its utilization in protected area planning and management.

- We explore data and knowledge gaps with respect for the integration of wider conservation management needs (i.e., beyond the strict biodiversity needs) for the Natura 2000 network. This review also contributes by suggesting specific recommendations for future progress in developing knowledge baselines and inventory frameworks for protected areas in general; an important unmet need in Greece (see recommendations, below).

- The wind farm case study initiates a conflict risk mapping exercise. Utilizing CES assessment to identify management problems in protected areas is an important unmet need. Aesthetic and recreational values are important non-material values provided by ecosystems and landscapes in protected areas, yet their effective protection and enforcement is severely lacking in the Natura 2000 system in Greece. Our cursory screening shows that wind energy development, if continued as planned, will create wholesale changes and severe environmental and cultural degradation in many Natura sites.

The wind farm risk mapping exercise using CES attributes is attempted for the first time at the scale of Greece’s Natura 2000 network. This review provides a rapid method to depict overlapping hotspots of selected CES values with proposed wind turbine development pressures. We calculated potential conflict risk in a conservative manner, stacking the selected CES scores with the total number of proposed wind farms within Natura sites. The cumulative number of wind turbines functions as a proxy of modern human-induced change within protected areas. Wind farms of industrial scale are known to have various negative impacts on biodiversity, landscape character and on local communities; notable discourse has developed with concern for such developments in many Mediterranean protected areas [76,77]. Over a decade now, Greek environmental NGOs and researchers have used specific criteria to propose “no-go” areas (exclusion zones) for wind energy development within parts of Natura sites [78]. Public resentment for the apparent damage to ecosystems, cultural values and aesthetic integrity caused by certain wind farm projects is now widespread in Greece. The landscape-scale changes of many new industrial wind farms are widely visible in many former wild land areas in Greece today (e.g., Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Examples of visual impacts and associated infrastructure of industrial wind farms that may compromise CES attributes. (A) Antia, Euboea Island (38.036548, 24.560521), (B) Marmari, Euboea Island (38.094239, 24.309008), (C) Kassidiaris, Epirus (39.787521, 20.540946), (D) Perganti, Acarnanian mountains-road building (38.784682, 20.998657), (E) Perganti, Acarnanian mountains—wind turbines and their platforms (38.769576, 20.992692) (Photograph credits in the acknowledgements).

Our wind farm risk exercise suggests for the first time that in many Natura sites the large number and dense concentration of industrial wind turbines may conflict with certain CES values. Our mechanistic assessment rapidly identifies dozens of Natura sites that face the risk of conflict solely based on the relative number of proposed wind turbines and the high aesthetic and recreational benefits that these sites are known to provide. Since the risk analysis exercise is limited to only two CES categories, this result is in our opinion a bare minimum of the various other negative impacts that may result if all proposed wind turbines are developed. Recent reviews agree that the full ramifications of certain industrial-scale renewable energy developments are poorly studied and social impacts may be high, especially within protected areas and wild land areas [79,80,81]. Moreover, other similarly widespread resource development problems such as touristic and urban sprawl, road-building, mining and small hydro-electric plant developments could also be used to explore conflict risk with CES attributes in protected areas, in a similar manner.

Beyond the conflict risk mapping, the approach promoted here follows the MAES procedure, which is now widely used in Europe [64]. The inventory produced (evaluation matrices and maps) is an important part of the reference data platform needed for the implementation of MAES for the Greek territory, and complements recent ES attempts at the state scale [59,82]. Regional-level screening initiatives, such as this rapid assessment, help summarize conditions and/or nature–human interactions that are not directly accessible in other kinds of survey procedures or at finer spatial scales [83]. The framework presented here provides guidance on using proxy indicators to identify areas where conservation actions and conflict risk should be focused. This geographical assessment may help effectively target critical areas for both biodiversity and ecosystem services that directly benefit people. This state-wide assessment exercise also confirms that there are still serious gaps in available cultural resource inventories [62]. Some indicators remain rather ambiguous and poorly defined; this is to be expected in categories such as sacred sites [4] or cultural heritage features in general [84]. There is much more information that can be inventoried and operationalized within a state-wide, site-based framework; for example, concerning tourism and ecotourism, this being another salient and understudied aspect in Greece’s Natura sites [74,85]. At a future stage, this inventory and assessment screening could be enhanced with mixed methods approaches, i.e., using different indicator types and different data compilation methods at the regional or site scale [27,86] or the application of qualitative, citizen-based assessments and social media tools [87].

This CES review is timely for Greece, since protected area management is currently undergoing reforms. A new protected area management agency was recently enacted under the auspices of the Ministry of Environment and Energy (Law 4685/2020). Our initial survey work and recommendations (see below), performed at a national scale, could help guide planning decisions, build new management paradigms and perhaps help avoid costly conflicts. Many recent reviews promote the need for science–policy interfaces to address the relationship between cultural values and various land-use decisions [54]. At the state-level survey scale, it has not been easy to bridge the gap among the interfaces of conservation science, policy development and protected area conservation management practices [88,89]. In this context, CES approaches seem to be productive applications for exploratory research and development and conservation planning, even in data-scarce conditions [90].

4.2. Limitations of this Review

Cartography and attempts at quantification are the main steps required in order to improve the recognition and implementation of CES in decision-making and institutional up-take [4,27]. Our rapid survey assesses a large number of varied and rather recently delineated Natura sites. Operationalizing CES indicators in a standard way is difficult at this broad spatial scale and sometimes such reviews are necessarily limited to screening-level generalizations. With this general premise in mind, we recognize the following limitations in this study:

- Distance-based archival data or metadata previously collected by a single or few reviews may be subject to inherent biases [91], and in data-scarcity conditions bibliographical and online surveys cannot possibly be exhaustive.

- Natura sites have been differentially studied and biases exist based on their size (areal extent) and exact site-boundary delineations [62]. The larger and high-profile “famous” sites host much more and detailed available data, including cultural attributes and CES values. This situation is difficult to heal: the “smaller” and newer sites (including some peri-urban sites) are less studied and may lag behind in state-wide evaluations due to data gaps or data inventory biases [43].

- This work focuses mainly on mapping CES supply using proxy indicators, but CES demand is poorly defined here, though it is also important. Exploring social preferences would be a useful way forward in order to complement this inventory. Tradeoffs and synergies between bundles of services dependent on the ecosystems providing them and on appreciating demand for CES would be important in a revised review [92].

- Minimal social media data was compiled in this survey; only one citizens’ science portal on bird watching/birding hotspots (ebird) [93] was successfully utilized (i.e., accurately identifying locations with outstanding wildlife watching opportunities [94]). Especially since in protected areas local profit-generation depends on tourism, recreation and educational interest [95], involving more actors through social media and crowd-sourcing could enable plural valuation approaches; i.e., assessing multiple values attributed to nature by stakeholders [87,96,97,98].

- Marine CES are not investigated in our review for the reasons outlined by Kokkoris and colleagues in 2020 [43]. There are still inherent difficulties and outstanding data gaps in marine areas [99]; and marine protected areas are difficult to compare to terrestrial system conditions in a state-wide scale [100]. We expect specific reviews to develop in this important segment of protected area research soon [87].

- The distance-based risk mapping on wind farms is not a complete conflict risk analysis. In our opinion, this is a conservative and transparent prioritization screening exercise. This mechanistic representation cannot depict the many and various negative impacts of industrial wind farm developments on wild lands; e.g., where a small number of turbines are placed in inappropriate locations or where off-site wind turbines and their infrastructure may impact adjacent Natura sites. The prioritization exercise focuses on the most vulnerable frontline conflict Natura sites; and it is indicative of the distribution of potential cumulative impacts.

No doubt, as in other CES reviews, conceptual and analytical difficulties are apparent in both this indicator selection and the conflict risk screening exercise. The starting point for choosing interpretation tools is to describe and review CES indicators [9]. We intentionally utilize cartography and spatial analyses that strive for transparency in their method and ease of interpretation, and we intentionally avoid more complex analyses that may misinform or generalize [101]. Finally, prioritizing exercises for protected area sites are not in themselves enough for conservation action [101,102] and it is important to show the basic limitations and where gaps exist. A degree of subjectivity in the selection of available indicators for analysis cannot be avoided, and this is frequently the case in many schemes that produce state-wide spatial protected-area prioritizations [103,104]. According to English and Lee: “The fact of defining intangible values is not itself culturally neutral... but if we do not define intangible values in some way, it will be virtually impossible for them to influence management” [105].

4.3. Recommendations

The inclusion of CES provision within European biodiversity conservation could help enhance present conservation efforts, especially through the development of a greater awareness for cultural values and non-material benefits provided directly to people in and by protected areas [106]. Yet care is needed in using ES surveys where there is data scarcity and poor inventory baselines [84]. Until recently, CES or CES-relevant reviews have been largely ignored or overlooked in planning and policy decision-making [11], but needs and requirements for sustainable protected areas in the EU Natura 2000 network are changing [35,107,108]). A more holistic valuation of protected areas, including the social, socio-economic and socio-political aspects, is now seen as an imperative for successful conservation and sustainability of protected area networks [109].

The cultural and historical idiosyncrasies of each country’s protected area network need to be appreciated in order to use CES information effectively in conservation strategies. The protected area network in Greece is evolving and significant reforms should take place. Its evolution has strong socio-political components, sometimes independent of the protected sites’ biodiversity management requirements [62,109]. Cultural values and an understanding of CES-relevant issues are thus intimately related to the effectiveness and sustainability of the protected area network. CES assessments on different spatial scales (state, regional and local) require organized information compilation and integration measures, and a common ES platform should be developed. Beyond the broad-scale survey explored here, contributions are needed directly from the public, stakeholders, experts and policymakers.

Although CES are integrated within the ES framework, they are in many ways more challenging to research, to monitor and apply in practice. Here we propose a multipronged initiative for building CES baselines for Greece’s protected areas at the national scale. A state-wide investigation should include the entire network of protected areas and proposed protected areas in Greece, beyond the confines of the Natura sites. Based on current unmet needs, this proposed research initiative should include the following:

- A national inventory of CES and cultural attributes of all protected areas. Information on cultural values and CES within protected areas must be inventoried in a national registry (i.e., all cultural features, including hiking trails and paths, archeological sites and non-material site-based distinctions). Specific investigations should further explore the role of several Natura/protected area site factors, such as the site’s size, land cover types and changes, accessibility and other parameters in relation to CES attributes.

- Adaptive CES mixed methods research initiatives. The MAES methodology as well as mixed methods approaches (i.e., both quantitative and qualitative research) should be promoted [43]. Local priorities may dictate the need for indicators specific to single sites or a set of Natura sites (e.g., at the ecoregional or state regional level). It may be useful and important to identify a greater variety of CES types and indicators, and the precise structure of the services and who the beneficiaries are [8,110]. We urge flexibility when developing indicators and other evaluation schemes as has become apparent in recent so-called “post-normal science” applications [111]. A transdisciplinary and adaptive approach should be encouraged [27]. Flexibility in using indicators (including proxy indicators) must be upheld in order to drive exploratory and innovative research at this early stage of CES development in Greece.

- A landscape approach. More attention is needed to landscape-scale research and conservation, especially targeting both highly valued cultural landscapes [3,112] and wilderness (or wild land) areas [81,113]. This ties in with EU policy requirements for high nature value farming [114] and the many modern changes and challenges to European landscapes [79,115,116]. In Greece, particular attention to the conflicts created by industrial wind farm development should be immediately reviewed at the landscape scale. Our broad-scale survey suggests that potential degradation and threats to CES by wind farms in Natura sites may have been overlooked, ignored or even intentionally sidelined within the current renewable energy boom. At the scale of landscapes (sub-areas of the protected area sites) a critical assessment should be developed to explore and respond to the potential threats and risks of degradation to protected area integrity.

- A new emphasis on aesthetic values in protected areas. Aesthetic and scenic values, which are culturally important attributes, may have been overlooked while they have outstanding importance for human wellbeing and are vital components of landscape integrity [117,118]. Specific efforts to explore and document aesthetic values are required at both the protected area site and the wider landscape scale [119,120,121]. There are many applied approaches to assess and integrate landscape conservation in protected area management [122,123,124]. Aesthetics is a critical aspect of a CES review, but it is no doubt a “wicked problem” in conservation area management [125]. Compared to other CES attributes, aesthetic indicators may be highly subjective [8] and any attempt towards quantification requires accounting for the uncertainties induced from subjectivity [126]. Despite these difficulties, aesthetics is crucial in landscape planning and conservation, and its involvement in this CES review shows a need for less reductive and more holistic assessment approaches. More particularly for Greece, all available incentives to preserve the aesthetic quality of protected areas should be promoted; one step is to apply Law 1469/50 to inventory and delineate “Sites of Outstanding Natural Beauty” [53].

- A communication initiative. A strategy for public awareness to promote and effectively enforce protected area conservation initiatives is important. Part of the problem with ineffective conservation outcomes in protected areas is that knowledge about non-material benefits and values is poorly communicated and disseminated. Without investment in publicity and media initiatives for this, the broader socio-ecological issues, especially sensitive and complex ones such as CES, may fall in the back-seat of other conflicting and pressing issues [127,128]. An investment in CES research and its promotion provides a storehouse of the important knowledge needed for conservation-relevant communication, including multi-stakeholder collaboration and participation and education at all levels (including landscape literacy).

The above initiative could help to support some of the growing pains observed in Greece’s protected area network. This initiative should support the consideration of cultural and social factors and the productive involvement of various stakeholders and local communities in protected areas. Importantly, this could help direct and promote more efficient involvement in site-scale management, particularly for safeguarding non-material services, such as aesthetic values, that are still much neglected. In fact, the greatest failure of Greece’s protected areas may be the lack of concern for spatial conservation planning with respect for the aesthetic and other landscape-scale values.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first state-wide review of CES in Greece’s Natura 2000 network. Such efforts at inventorying and assessing cultural information baselines are important in appreciating protected area attributes for planning at the national scale. This study enabled us to: a) build for the first time a preliminary list of selected CES indicators supplied by Natura sites based on available proxies; b) assess the spatial distribution of the potential CES supplied by these sites; and c) use this information to promote insights for integrated conservation management applications, in terms of a conflict risk assessment exercise. The identification of hot spots and wider areas of significance for the supply of CES could be important for protected area managers, government management agencies and the many stakeholders participating in protected area networks. This procedure may be especially useful in identifying and mitigating conflicts.

Although Natura sites and other natural protected area designations focus on conserving listed species and habitat types, they could also better help protect unique cultural attributes and the protected areas’ cultural and societal values in a holistic way. Mediterranean protected areas are special social constructs and should not be viewed solely as strict preserves for nature. The results of this study may help promote interest in CES, to urgently conduct more in-depth inventories and produce assessments at varying scales using adaptive mixed methods through an integrative research platform. Protected areas demand new multidisciplinary, transdisciplinary and inclusive approaches in order to guide management and to protect ecosystems and landscapes from inappropriate developments. Interest in CES also helps promote protected areas’ sustainability as “protected area institutions” that uphold many inherent cultural values. Protected areas are natural laboratories for implementing various types of CES assessments, and the rapid screening procedure utilized here should be applicable in other countries and protected area jurisdictions as well.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V., I.P.K., P.D. and S.Z.; Methodology, I.P.K.,V.V. and S.Z.; Software, I.P.K.; Validation, I.P.K., G.K. and P.D.; Formal Analysis, I.P.K. and V.V.; Investigation, V.V., S.Z. and I.P.K.; Resources, I.P.K. and V.V.; Data Curation, I.P.K. and V.V.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, V.V. and S.Z.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.Z., V.V., I.P.K., P.D. and G.K.; Supervision, P.D. and G.K.; Project Administration, P.D.; Funding Acquisition, P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Commission LIFE Integrated Project, LIFE-IP 4 NATURA “Integrated Actions for the Conservation and Management of Natura 2000 sites, species, habitats and ecosystems in Greece”, Grant Number: LIFE 16 IPE/GR/000002; the first author V.V. benefited from a scholarship through this project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data bases developed in this work are available upon consultation with the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Warmest thanks to Theocharis Vavalidis and Aris Vidalis for all assistance. Photos for Figure 9, are kindly supplied (with permission) by: Thanassis Biniaris, https://www.ochi.gr/; (Photos: A,B,C) and Timos Parthenis, http://katelanos.blogspot.com/ (Photos D&C). The abstract photo is courtesy of Serhat Kucukali.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Seardo, B.M. Biodiversity and landscape policies: Towards an integration? A European overview. In Nature Policies and Landscape Policies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Church, A.; Fish, R.; Haines-Young, R.; Mourato, S.; Tratalos, J.; Stapleton, L.; Willis, C.; Coates, P.; Gibbson, S.; Leyshon, C.; et al. UK National Ecosystem Assessment Follow-On: Work Package Report 5: Cultural Ecosystem Services and Indicators; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tengberg, A.; Fredholm, S.; Eliasson, I.; Knez, I.; Saltzman, K.; Wetterberg, O. Cultural ecosystem services provided by landscapes: Assessment of heritage values and identity. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 2, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, B.; Kroll, F.; Müller, F.; Windhorst, W. Landscapes′ capacities to provide ecosystem services—A concept for land—cover based assessments. Landsc. Online 2009, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobstvogt, N.; Watson, V.; Kenter, J.O. Looking below the surface: The cultural ecosystem service values of UK marine protected areas (MPAs). Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 10, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulcomb, C.; Fletcher, R.; Lewis, A.; Akoglu, E.; Robinson, L.; von Almen, A.; Hussain, S.; Glenk, K. A pathway to identifying and valuing cultural ecosystem services: An application to marine food webs. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 11, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, G.B.; Kenter, J.O.; O′Connor, S.; Daunt, F.; Young, J.C. A fulfilled human life: Eliciting sense of place and cultural identity in two UK marine environments through the Community Voice Method. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 39, 100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, R.; Irvine, K.N.; Church, A.; Fish, R.; Ranger, S.; Kenter, J.O. Subjective well-being indicators for large-scale assessment of cultural ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ament, J.M.; Moore, C.A.; Herbst, M.; Cumming, G.S. Cultural Ecosystem Services in Protected Areas: Understanding Bundles, Trade-Offs, and Synergies. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbieu, U.; Grünewald, C.; Martín-López, B.; Schleuning, M.; Böhning-Gaese, K. Mismatches between supply and demand in wildlife tourism: Insights for assessing cultural ecosystem services. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 78, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satz, D.; Gould, R.K.; Chan, K.M.; Guerry, A.; Norton, B.; Satterfield, T.; Halpern, B.S.; Levine, J.; Woodside, U.; Hannahs, N.; et al. The challenges of incorporating cultural ecosystem services into environmental assessment. AMBIO 2013, 42, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, C.; Bonn, A.; Burkhard, B.; Daube, S.; Dietrich, K.; Engels, B.; Frommer, J.; Götzl, M.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Job-Hoben, B.; et al. Towards a national set of ecosystem service indicators: Insights from Germany. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, C.; Provenzale, A.; van der Meer, J.; Wijnhoven, S.; Nolte, A.; Poursanidis, D.; Janss, G.; Jurek, M.; Andresen, M.; Poulin, B.; et al. Ecosystem services in European protected areas: Ambiguity in the views of scientists and managers? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaligot, R.; Hasler, S.; Chenal, J. National assessment of cultural ecosystem services: Participatory mapping in Switzerland. Ambio 2019, 48, 1219–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Morcillo, M.; Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C. An empirical review of cultural ecosystem service indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 29, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleasant, M.M.; Gray, S.A.; Lepczyk, C.; Fernandes, A.; Hunter, N.; Ford, D. Managing cultural ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 8, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; Burkhard, B. The indicator side of ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiagarajah, J.; Wong, S.K.M.; Richards, D.R.; Friess, D.A. Historical and contemporary cultural ecosystem service values in the rapidly urbanizing city state of Singapore. Ambio 2015, 44, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Scolozzi, R.; De Marco, C.; Tappeiner, U. Mapping beneficiaries of ecosystem services flows from Natura 2000 sites. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 9, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahuelhual, L.; Carmona, A.; Lozada, P.; Jaramillo, A.; Aguayo, M. Mapping recreation and ecotourism as a cultural ecosystem service: An application at the local level in Southern Chile. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 40, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastur, G.M.; Peri, P.L.; Lencinas, M.V.; García-Llorente, M.; Martín-López, B. Spatial patterns of cultural ecosystem services provision in Southern Patagonia. Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 31, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauerhofer, V.; Ichinose, T.; Blackwell, B.D.; Willig, M.R.; Flint, C.G.; Krause, M.; Penker, M. Underuse of social-ecological systems: A research agenda for addressing challenges to biocultural diversity. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friess, D.A.; Yando, E.S.; Wong, L.-W.; Bhatia, N. Indicators of scientific value: An under-recognised ecosystem service of coastal and marine habitats. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, T. Abandoning the concept of cultural ecosystem services, or against natural–scientific imperialism. BioScience 2019, 69, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, T. The concept of cultural ecosystem services should not be abandoned. BioScience 2019, 69, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyra, M.; Kleemann, J.; Cetin, N.I.; Navarrete, C.J.V.; Albert, C.; Palacios-Agundez, I.; Ametzaga-Arregi, I.; La Rosa, D.; Rozas-Vásquez, D.; Esmail, B.A.; et al. The ecosystem services concept: A new Esperanto to facilitate participatory planning processes? Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1715–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paracchini, M.L.; Zulian, G.; Kopperoinen, L.; Maes, J.; Schägner, J.P.; Termansen, M.; Zandersen, M.; Perez-Soba, M.; Scholefield, P.A.; Bidoglio, G. Mapping cultural ecosystem services: A framework to assess the potential for outdoor recreation across the EU. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 45, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogiatzakis, I.N.; Zotos, S.; Litskas, V.D.; Manolaki, P.; Sarris, D.; Stavrinides, M. Towards implementing Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services in Cyprus: A first set of indicators for ecosystem management. One Ecosyst. 2020, 5, e47715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.G.E.; Schuster, R.; Jacob, A.L.; Hanna, D.E.L.; Dallaire, C.O.; Raudsepp-Hearne, C.; Bennett, E.; Lehner, B.; Chan, K.M.A. Identifying key ecosystem service providing areas to inform national-scale conservation planning. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbieu, U.; Grünewald, C.; Martín-López, B.; Schleuning, M.; Böhning-Gaese, K. Large mammal diversity matters for wildlife tourism in Southern African Protected Areas: Insights for management. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blicharska, M.; Smithers, R.J.; Hedblom, M.; Hedenås, H.; Mikusiński, G.; Pedersen, E.; Sandström, P.; Svensson, J. Shades of grey challenge practical application of the cultural ecosystem services concept. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 23, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, G. Integrating Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Use: Lessons Learned from Ecological Networks; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N.; McGinlay, J.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. Improving social impact assessment of protected areas: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 64, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferranti, F.; Turnhout, E.; Beunen, R.; Behagel, J.H. Shifting nature conservation approaches in Natura 2000 and the implications for the roles of stakeholders. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 1642–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kati, V.; Hovardas, T.; Dieterich, M.; Ibisch, P.L.; Mihok, B.; Selva, N. The challenge of implementing the European network of protected areas Natura 2000. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzan, M.V.; Pinheiro, A.M.; Mascarenhas, A.; Morán-Ordóñez, A.; Ruiz-Frau, A.; Carvalho-Santos, C.; Vogiatzakis, I.N.; Arends, J.; Santana-Garcon, J.; Roces-Díaz, J.V.; et al. Improving ecosystem assessments in Mediterranean social-ecological systems: A DPSIR analysis. Ecosyst. People 2019, 15, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, J.; Aronson, J.; Bodiou, J.-Y.; Boeuf, G. The Mediterranean Region: Biological Diversity in Space and Time; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Catsadorakis, G. The conservation of natural and cultural heritage in Europe and the Mediterranean: A Gordian knot? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2007, 13, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizos, T.; Koulouri, M.; Vakoufaris, H.; Psarrou, M. Preserving characteristics of the agricultural landscape through agri-environmental policies: The case of cultivation terraces in Greece. Landsc. Res. 2010, 35, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, K.; Vogiatzakis, I.N. Nature protection in Greece: An appraisal of the factors shaping integrative conservation and policy effectiveness. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zogaris, S.; Skoulikidis, N.; Dimitriou, E. River and wetland restoration in Greece: Lessons from biodiversity conservation initiatives. In The Rivers of Greece; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 403–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkoris, I.P.; Mallinis, G.; Bekri, E.S.; Vlami, V.; Zogaris, S.; Chrysafis, I.; Mitsopoulos, I.; Dimopoulos, P. National Set of MAES Indicators in Greece: Ecosystem Services and Management Implications. Forests 2020, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, P.; Drakou, E.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Katsanevakis, S.; Kallimanis, A.; Tsiafouli, M.; Bormpoudakis, D.; Kormas, K.; Arends, J. The need for the implementation of an Ecosystem Services assessment in Greece: Drafting the national agenda. One Ecosyst. 2017, 2, e13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, E.; Adams, W.M. Neoliberal capitalism and conservation in the post-crisis era: The dialectics of “green” and “un-green” grabbing in Greece and the UK. Antipode 2015, 47, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tratsa, M. What is left on the environmental map after “the eraser of the Ministry of Environment and Energy”. To Vima 2020, 143, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Lekakis, J.N.; Kousis, M. Economic crisis, Troika and the environment in Greece. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 2013, 18, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliogiannis, C.; Cliquet, A.; Koedam, N. The impact of the economic crisis on the implementation of the EU Nature Directives in Greece: An expert-based view. J. Nat. Conserv. 2019, 48, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aperghis, G.; Gaethlich, M. The natural environment of Greece: An invaluable asset being destroyed. J. Southeast Eur. Black Sea Stud. 2006, 6, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papayannis, T. Action for Culture in Mediterranean Wetlands; Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Arthropods: Athens, Greece, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Katapidi, I. Does Greek conservatIon policy effectively protect the cultural landscapes? A critical examination of policy’s efficiency in traditional Greek settlements. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2014, 21, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tsilimigkas, G.; Derdemezi, E.-T. Spatial Planning and the Traditional Settlements Management: Evidence from Visibility Analysis of Traditional Settlements in Cyclades, Greece. Plan. Pract. Res. 2020, 35, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beriatos, E. The Stymfalia Conviction and gaps in landscape policy in Greece. Aeihoros 2014, 19, 140–157. [Google Scholar]

- Balvanera, P.; Jacobs, S.; Nagendra, H.; O’Farrell, P.; Bridgewater, P.; Crouzat, E.; Dendoncker, N.; Goodwin, S.; Gustafsson, K.M.; Kadykalo, A.N.; et al. The science-policy interface on ecosystems and people: Challenges and opportunities. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarém, F.; Saarinen, J.; Brito, J.C. Mapping and analysing cultural ecosystem services in conflict areas. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 110, 105943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, M.; Vinci, S.; Lamonica, G.R.; Salvati, L. Socio-spatial Disparities and the Crisis: Swimming Pools as a Proxy of Class Segregation in Athens. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priority Action Framework. Setting Priorities for Nature Conservation Within the Natura 2000 Network in Greece (Council Directive 92/43/EC, Directive 2009/147/EC); European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulou, I. Priority in Nature: Evaluating the Implementation of the National Biodiversity Strategy; The Green Tank: Athens, Greece, 2020. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Kokkoris, I.P.; Drakou, E.G.; Maes, J.; Dimopoulos, P. Ecosystem services supply in protected mountains of Greece: Setting the baseline for conservation management. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2018, 14, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, P.; Bergmeier, E.; Theodoropoulos, K.; Fischer, P.; Tsiafouli, M. Monitoring Guide for Habitat Types and Plant Species in the Natura 2000 Sites of Greece with Management Institutions; University of Ioannina and Hellenic Ministry of the Environment, Physical Planning & Public Works: Agrinio, Greece, 2005; p. 170. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- EEA. EEA Reference Grid. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/eea-reference-grids-2 (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Vlami, V.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Zogaris, S.; Cartalis, C.; Kehayias, G.; Dimopoulos, P. Cultural landscapes and attributes of “culturalness” in protected areas: An exploratory assessment in Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 595, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, J.; Teller, A.; Erhard, M.; Liquete, C.; Braat, L.; Berry, P.; Egoh, B.; Puydarrieux, P.; Fiorina, C.; Santos, F. Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services. Analytical Framework for Ecosystem Assessments under Action 5 of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020. 2nd Report-Final; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, J.; Teller, A.; Erhard, M.; Condé, S.; Vallecillo, S.; Barredo, J.I.; Paracchini, M.L.; Abdul Malak, D.; Trombetti, M.; Vigiak, O.; et al. Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services: An EU Ecosystem Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2020; p. 446. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Ministry of the Environment, Energy and Climate Change. National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan; Ministry of the Environment, Energy and Climate Change: Athens, Greece, 2014.

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin-Young, M.B. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) V5. 1 and Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure; Fabis Consulting Ltd.: Nottingham, UK, 2018; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oudenhoven, A.P.; Schröter, M.; Drakou, E.G.; Geijzendorffer, I.R.; Jacobs, S.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Chazee, L.; Czúcz, B.; Grunewald, K.; Lillebø, A.I. Key criteria for developing ecosystem service indicators to inform decision making. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 95, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project 2016. Available online: http://qgis.osgeo.org (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Czyż, T. Methodological problems in the design of indicators in social sciences with the focus on socio-economic geography. Studia Reg. 2017, 50, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- RAE. Wind Turbines Point Vector Shapefile 2020 by Regulatory Authority for Energy (RAE). Available online: http://www.rae.gr/geo/ (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- ESRI. FAQ: What Is The Jenkins Optimization Method? Available online: https://support.esri.com/en/technical-article/000006743 (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Jenks, G.F. The data model concept in statistical mapping. Int. Yearb. Cartogr. 1967, 7, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster, R. In Memoriam: George, F. Jenks (1916–1996). Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1997, 24, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreopoulos, D.; Damigos, D.; Comiti, F.; Fischer, C. Estimating the non-market benefits of climate change adaptation of river ecosystem services: A choice experiment application in the Aoos basin, Greece. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 45, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidou, C.; Votsi, N.-E.; Sgardelis, S.; Halley, J.; Pantis, J.; Tsiafouli, M. Ecosystem Service capacity is higher in areas of multiple designation types. One Ecosyst. 2017, 2, e13718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Montobbio, P.; Farrell, K.N. Wind farm siting and protected areas in catalonia: Planning alternatives or reproducing ′one-dimensional thinking′? Sustainability 2012, 4, 3180–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlami, V.; Danek, J.; Zogaris, S.; Gallou, E.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Kehayias, G.; Dimopoulos, P. Residents’ Views on Landscape and Ecosystem Services during a Wind Farm Proposal in an Island Protected Area. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimalexis, A.; Kastritis, T.; Manolopoulos, A.; Korbeti, M.; Fric, J.; Saravia Mullin, V.; Xirouchakis, S.; Bousbouras, D. Identification and Mapping of Sensitive Bird Areas to Wind Farm Development in Greece; Hellenic Ornithological Society: Athens, Greece, 2010; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, S. Protecting wild land from wind farms in a post-EU Scotland. Int. Environ. Agreements 2018, 18, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehbein, J.A.; Watson, J.E.; Lane, J.L.; Sonter, L.J.; Venter, O.; Atkinson, S.C.; Allan, J.R. Renewable energy development threatens many globally important biodiversity areas. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 3040–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, J.R.; Possingham, H.P.; Venter, O.; Biggs, D.; Watson, J.E. The Extraordinary Value of Wilderness Areas in the Anthropocene. In Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkoris, I.P.; Dimopoulos, P.; Xystrakis, F.; Tsiripidis, I. National scale ecosystem condition assessment with emphasis on forest types in Greece. One Ecosyst. 2018, 3, e25434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heink, U.; Kowarik, I. What are indicators? On the definition of indicators in ecology and environmental planning. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hølleland, H.; Skrede, J.; Holmgaard, S.B. Cultural heritage and ecosystem services: A literature review. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2017, 19, 210–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertzanis, Α.; Syleouni, S.; Mertzanis, K.; Zogaris, S. Ecotourism promotion in a greek national park: The development and management of farmakides trail on mt oiti. Ecol. Saf. 2016, 10, 204–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkoris, I.P.; Bekri, E.S.; Skuras, D.; Vlami, V.; Zogaris, S.; Maroulis, G.; Dimopoulos, D.; Dimopoulos, P. Integrating MAES implementation into protected area management under climate change: A fine-scale application in Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 695, 133530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Frau, A.; Ospina-Alvarez, A.; Villasante, S.; Pita, P.; Maya-Jariego, I.; de Juan, S. Using graph theory and social media data to assess cultural ecosystem services in coastal areas: Method development and application. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 45, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grêt-Regamey, A.; Sirén, E.; Brunner, S.H.; Weibel, B. Review of decision support tools to operationalize the ecosystem services concept. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevance, A.-S.; Bridgewater, P.; Louafi, S.; King, N.; Beard, T.D., Jr.; Van Jaarsveld, A.S.; Ofir, Z.; Kohsaka, R.; Jenderedijan, K.; Rosales Benites, M.; et al. The 2019 review of IPBES and future priorities: Reaching beyond assessment to enhance policy impact. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, A. Cultural ecosystem services and economic development: World Heritage and early efforts at tourism in Albania. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 10, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G.B. Designing Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-López, B.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; García-Llorente, M.; Palomo, I.; Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Del Amo, D.G.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Palacios-Agundez, I.; Willaarts, B.; et al. Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, B.L.; Aycrigg, J.L.; Barry, J.H.; Bonney, R.E.; Bruns, N.; Cooper, C.B.; Damoulas, T.; Dhondt, A.A.; Dietterich, T.; Farnsworth, A.; et al. The eBird enterprise: An integrated approach to development and application of citizen science. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 169, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolou, D.; Vlachos, C.; Kastritis, T.; Dimalexis, T. The Important Bird Areas of Greece: Priority Areas for Biodiversity Conservation; Hellenic Ornithological Society: Athens, Greece, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tenerelli, P.; Demšar, U.; Luque, S. Crowdsourcing indicators for cultural ecosystem services: A geographically weighted approach for mountain landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 64, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteros-Rozas, E.; Martín-López, B.; Fagerholm, N.; Bieling, C.; Plieninger, T. Using social media photos to explore the relation between cultural ecosystem services and landscape features across five European sites. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilonzi, F.; Ota, T. Influence of cultural contexts on the appreciation of different cultural ecosystem services based on social network analysis. One Ecosyst. 2019, 4, e33368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, D.; Guibrunet, L.; Benessaiah, K.; Berghöfer, A.; Chaves-Chaparro, J.; Díaz, S.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Lele, S.; et al. Use your power for good: Plural valuation of nature–the Oaxaca statement. Glob. Sustain. 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomidi, M.; Katsanevakis, S.; Borja, A.; Braeckman, U.; Damalas, D.; Galparsoro, I.; Mifsud, R.; Mirto, S.; Pascual, M.; Pipitone, C.; et al. Assessment of goods and services, vulnerability, and conservation status of European seabed biotopes: A stepping stone towards ecosystem-based marine spatial management. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2012, 13, 49–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.; Baulcomb, C.; Hall, C.; Hussain, S. Revealing marine cultural ecosystem services in the Black Sea. Mar. Policy 2014, 50, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Bode, M.; Venter, O.; Barnes, M.D.; McGowan, J.; Runge, C.A.; Watson, J.E.; Possingham, H.P. Effective conservation requires clear objectives and prioritizing actions, not places or species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Game, E.T.; Kareiva, P.; Possingham, H.P. Six common mistakes in conservation priority setting. Conserv. Biol. 2013, 27, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkonen, N.; Moilanen, A. Identification of top priority areas and management landscapes from a national Natura 2000 network. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 27, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collen, B. Conservation prioritization in the context of uncertainty. Anim. Conserv. 2015, 18, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, A.J.; Lee, E. Managing the Intangible; The George Wright Forum, JSTOR: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Haslett, J.R.; Berry, P.M.; Bela, G.; Jongman, R.H.; Pataki, G.; Samways, M.J.; Zobel, M. Changing conservation strategies in Europe: A framework integrating ecosystem services and dynamics. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 2963–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso, V.; Clavero, M.; Villero, D.; Brotons, L. EU’s conservation efforts need more strategic investment to meet continental commitments. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso, V.; Morán-Ordóñez, A.; Canessa, S.; Brotons, L. Dynamic strategy for EU conservation. Science 2019, 363, 592–593. [Google Scholar]

- Tsianou, M.A.; Mazaris, A.D.; Kallimanis, A.S.; Deligioridi, P.S.K.; Apostolopoulou, E.; Pantis, J.D. Identifying the criteria underlying the political decision for the prioritization of the Greek Natura 2000 conservation network. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 166, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising cultural ecosystem services: A novel framework for research and critical engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscough, J.; Wilson, M.; Kenter, J.O. Ecosystem services as a post-normal field of science. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.; Union, W.C. Management Guidelines for IUCN Category V Protected Areas: Protected Landscapes/Seascapes; IUCN—The World Conservation Union: Gland, Switzerland, 2002; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M.; Carver, S.; Kun, Z.; McMorran, R.; Arrell, K.; Mitchell, G. Review of Status and Conservation of Wild Land in Europe. Report; The Wildland Research Institute, University of Leeds: Leeds, UK, 2010; Volume 148, p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Brunbjerg, A.K.; Bladt, J.; Brink, M.; Fredshavn, J.; Mikkelsen, P.; Moeslund, J.E.; Nygaard, B.; Skov, F.; Ejrnæs, R. Development and implementation of a high nature value (HNV) farming indicator for Denmark. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, M.; Quintas-Soriano, C.; Torralba, M.; Wolpert, F.; Plieninger, T. Landscape Change in Europe. In Sustainable Land Management in a European Context; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Marine, N.; Arnaiz-Schmitz, C.; Herrero-Jáuregui, C.; de la O Cabrera, M.R.; Escudero, D.; Schmitz, M.F. Protected Landscapes in Spain: Reasons for Protection and Sustainability of Conservation Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H.; Nassauer, J.I.; Daniel, T.C.; Fry, G. The shared landscape: What does aesthetics have to do with ecology? Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Landscape of culture and culture of landscape: Does landscape ecology need culture? Lands. Ecol. 2010, 25, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.C. Measuring Landscape Esthetics: The Scenic Beauty Estimation Method; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1976; Volume 167.

- Bieling, C.; Plieninger, T. Recording manifestations of cultural ecosystem services in the landscape. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlami, V.; Zogaris, S.; Djuma, H.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Kehayias, G.; Dimopoulos, P. A Field Method for Landscape Conservation Surveying: The Landscape Assessment Protocol (LAP). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrbe, R.-U.; Walz, U. Spatial indicators for the assessment of ecosystem services: Providing, benefiting and connecting areas and landscape metrics. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 21, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I.; Martín-López, B.; Potschin, M.; Haines-Young, R.; Montes, C. National Parks, buffer zones and surrounding lands: Mapping ecosystem service flows. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 4, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungaro, F.; Häfner, K.; Zasada, I.; Piorr, A. Mapping cultural ecosystem services: Connecting visual landscape quality to cost estimations for enhanced services provision. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronova, I. Landscape beauty: A wicked problem in sustainable ecosystem management? Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 688, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manta, E.; Ioannidis, R.; Sargentis, G.-F.; Efstratiadis, A. Aesthetic Evaluation of Wind Turbines in Stochastic Setting: Case Study of Tinos Island, Greece. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Vienna, Austria, 4–8 May 2020; p. 5484. [Google Scholar]

- Piperopoulos, G.P.; Tsantopoulos, G.E. The characteristics of environmental organisations in Greece in relation to employment of a public relations officer. Environ. Polit. 2006, 15, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruguete, M.S.; Gillen, M.M.; McCutcheon, L.E.; Bernstein, M.J. Disconnection from nature and interest in mass media. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2020, 19, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).