Public Perceptions on City Landscaping during the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease: The Case of Vilnius Pop-Up Beach, Lithuania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Right to Travel and COVID-19

2.2. Right to the City and Transformation

2.3. Urban Transformation

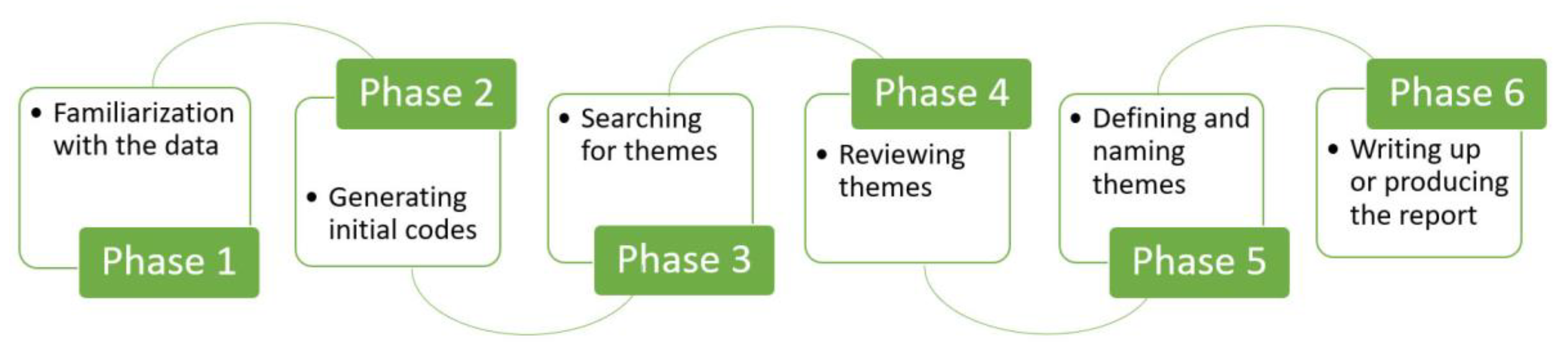

3. Materials and Methods

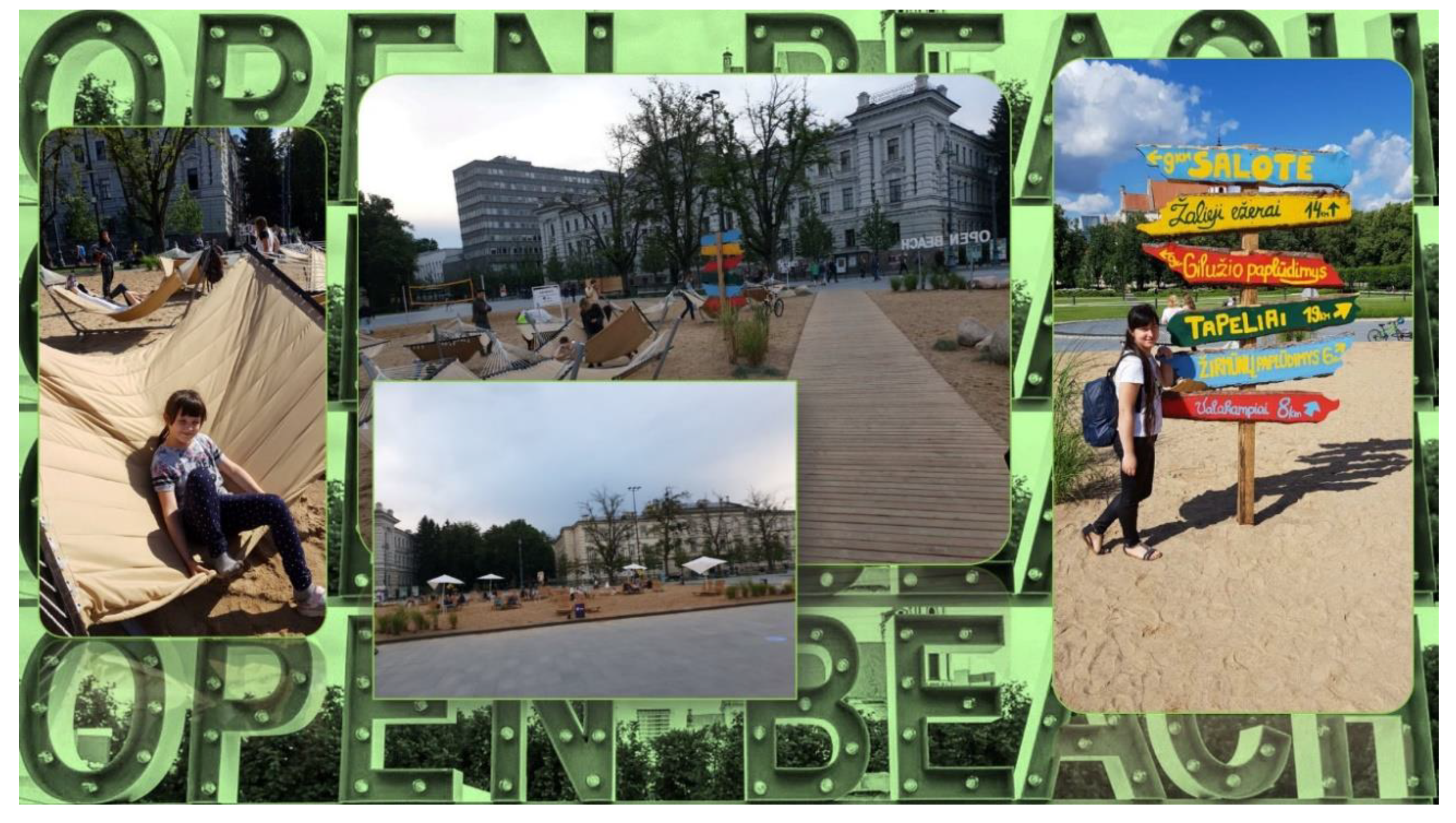

4. Research Setting

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Nostalgia for Heroic Landscape

6.2. Changing Memory Landscape

6.3. Enjoying the Landscape of Freedom

7. Concluding Insights

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wintle, T. COVID-19 and the City: How Past Pandemics Have Shaped Urban Landscapes. CGTN. 2020. Available online: https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2020-07-08/COVID-19-and-the-city-How-past-pandemics-have-shaped-urban-landscapes-QCFjZLBIxG/index.html (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Hooper, M. Pandemics and the Future of Urban Density: Michael Hooper on Hygiene, Public Perception and the “Urban Penalty”. Harvard University Graduate School of Design. 2020. Available online: https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2020/04/have-we-embraced-urban-density-to-our-own-peril-michael-hooper-on-hygiene-public-perception-and-the-urban-penalty-in-a-global-pandemic/ (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Newman Leigh, G. Reimagining the Post-Pandemic City. 2020. Available online: https://architectureau.com/articles/reimagining-the-post-pandemic-city/ (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, A. Public space or safe space—Remarks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Czas. Tech. 2020, 117, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strielkowski, W. International Tourism and COVID-19: Recovery Strategies for Tourism Organisations. Preprints 2020, 2020030445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Wang, W.; Kozak, M.; Liu, X.; Hou, H. Many brains are better than one: The importance of interdisciplinary studies on COVID-19 in and beyond tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T. Landscapes of Tourism: A Cultural Geographic Perspective. Tour. Environ. 2000, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T.S. Landscapes of Tourism. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 282–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, Landscape, towns and peri-urban and suburban areas. In Reflections and Proposals for the Implementation of the European Landscape Convention; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2012; pp. 9–48.

- Lukiškes square. Available online: https://archello.com/project/lukiskes-square. (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Honouring the Human Rights to Health and Freedom of Movement Realizing Rights. Global Policy Advisory Council Secretariat, Health Worker Migration Initiative 7 May 2009. Available online: https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/about/taskforces/migration/MigrationTaskForce_techbrief.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Fricker, M.; Steffen, R. Travel and public health. J. Infect. Public Health 2008, 1, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Toebes, B. Human rights and public health: Towards a balanced relationship. Int. J. Human Rights 2015, 19, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.M.A. Tourism and the Health Effects of Infectious Diseases: Are There Potential Risks for Tourists? Int. J. Saf. Secur. Tour. Hosp. 2014, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Compendium. Lithuania 2.9. 2019. Available online: https://www.culturalpolicies.net/country_profile/lithuania-2-9/ (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- I/A Court H.R. Matter of the Penitentiary Complex of Curado Regarding Brazil. Provisional Measures. Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of 23 November 2016. Available online: http://www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/communities/TB%20Human%20Rights%20and%20the%20Law%20Case%20Compendium%20(First%20Edition).pdf (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Page, E.M. Balancing Individual Rights and Public Health Safety during Quarantine: The U.S. and Canada. Case Western Reserve. J. Int. Law 2007, 38, 517. [Google Scholar]

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Art. 13. 1948. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the Right of Citizens of the Union and Their family Members to Move and Reside Freely within the Territory of the Member States Amending Regulation (EEC) No 1612/68 and Repealing Directives 64/221/EEC, 68/360/EEC, 72/194/EEC, 73/148/EEC, 75/34/EEC, 75/35/EEC, 90/364/EEC, 90/365/EEC and 93/96/EEC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32004L0038 (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- WHO. Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- WHO. New COVID-19 Law Lab to provide vital legal information and support for the global COVID-19 response, 22 July 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/22-07-2020-new-covid-19-law-lab-to-provide-vital-legal-information-and-support-for-the-global-covid-19-response (accessed on 26 July 2020).

- Meier, B.M.; Habibi, R.; Yang, Y.T. Travel restrictions violate international law. Science 2020, 367, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P. Article 12: Freedom of Movement of the Person. In A Commentary on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: The UN Human Rights Committee’s Monitoring of ICCPR Rights; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 325–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manville, P.B. The Origins of Citizenship in Ancient Athens; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Calabi, D. The Market and the City Square, Street and Architecture in Early Europe; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Veirier, L. Historic Districts for All: A Social and Human Approach for Sustainable Revitalization; brOchure Designed for Local Authorities. 2008. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000158331 (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Lefebvre, H. Le Droit à la Ville, Suivi de Espace et Politique. L Homme et la Société 1967, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, M. Citizenship and the right to the global city: Reimagining the capitalist world order. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 564–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, M. Excavating Lefebvre: The right to the city and its urban politics of the inhabitant. Geo J. 2002, 58, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The right to the city. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 939–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The right to the city. New Left Rev. 2008, 53, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuse, P. From critical urban theory to the right to the city. City 2010, 13, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margier, A.; Melgaço, L. Whose Right to the City? Urban Environ. 2016, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J.; Graham, M. An Informational Right to the City? Code, Content, Control, and the Urbanization of Information. Antipode 2017, 49, 907–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.G.; Chinelli, C.K.; Guedes, A.A.; Vazquez, E.G.; Hammad, A.W.; Haddad, A.N.; Soares, C.P. Smart and Sustainable Cities: The Main Guidelines of City Statute for Increasing the Intelligence of Brazilian Cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavolari, B. The Right to the City: Conceptual transformations and urban struggles. Rev. Direito Práxis 2020, 11, 470–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Helou, M.A. Towards A Post-Traumatic Urban Design That Heals Cities’ Inhabitants Suffering From PTSD. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2020, 4, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision. (ST/ESA/SER.A/366). 2015. Available online: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2014-Report.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Bertuzzi, N. Urban Regimes and the Right to the City: An Analysis of the No Expo Network and its Protest Frames. Rev. Crítica Ciências Sociais 2017, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siokas, G.; Tsakanikas, A.; Siokas, E. Implementing smart city strategies in Greece: Appetite for success. Cities 2021, 108, 102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourabi, H.; Nam, T.; Walker, S.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Mellouli, S.; Nahon, K.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J. Understanding Smart Cities: An Integrative Framework. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 2289–2297. [Google Scholar]

- Neirotti, P.; De Marco, A.; Cagliano, A.C.; Mangano, G.; Scorrano, F. Current trends in Smart City initiatives: Some stylised facts. Cities 2014, 38, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Yoo, M.; Park, K.C.; Lee, K.R.; Kim, J.H. A value of civic voices for smart city: A big data analysis of civic queries posed by Seoul citizens. Cities 2021, 108, 102941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, O.; Parker, B. Care, commoning and collectivity: From grand domestic revolution to urban transformation. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, T.; Bauder, M. Bottom-up touristification and urban transformations in Paris. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P. The Evolution, Definition and Purpose of Urban Regeneration. In Hugh Sykes and Rachel Granger; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017; pp. 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B. Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability. Technol. Soc. 2006, 28, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Commission on Population and Development addressed urbanization in its 51st session and took note of the report of the Secretary General on World Demographic Trends (E/CN.9/2018/5). The thematic report of the Secretary General on Sustainable Cities, Human Mobility and International Migration (E/CN.9/2018/2). Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/commission/sessions/2018/index.asp (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Alpopi, C.; Manole, C. Integrated Urban Regeneration—Solution for Cities Revitalize. Procedia Econ. Finance 2013, 6, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Brooks, A. Interpellation and Urban transformation: Lisbon’s sardine subjects. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2019, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofre, J.; Sánchez–Fuarros, Í.; Martins, J.C.; Pereira, P.; Soares, I.; Malet-Calvo, D.; Geraldes, M.; Díaz, A.L. Exploring Nightlife and Urban Change in Bairro Alto, Lisbon. City Community 2017, 16, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.; Benson, M.; Calafate-Faria, F. Multi-sensory ethnography and vertical urban transformation: Ascending the Peckham Skyline. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikci, E.; Koylan, D. Perceiving Urban Transformation from the Perspective of Evolutionary Economics: Renewal of Houses in Bağdat Street, Istanbul. J. Econ. Issues 2020, 54, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grübler, A.; Fisk, D. Energizing Sustainable Cities: Assessing Urban Energy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schlappa, H.; Neill, W.J.V. From Crisis Tochoice: Re-Imagining the Future in Shrinking Cities; URBACT Secretariat: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nagenborg, M. Urban robotics and responsible urban innovation. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2020, 22, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, T. The Rule of Law; Penguin: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Domaradzka, A. Urban Social Movements and the Right to the City: An Introduction to the Special Issue on Urban Mobilization. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2018, 29, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitusíková, A. Urban activism in Central and Eastern Europe: A theoretical framework. Slov. Narodop. 2015, 63, 326–338. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Dumitru, A.; Anguelovski, I.; Avelino, F.; Bach, M.; Best, B.; Binder, C.; Barnes, J.; Carrus, G.; Egermann, M.; et al. Elucidating the changing roles of civil society in urban sustainability transitions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 22, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbank, M.; Andranovich, G.; Heying, C. Olympic Dreams: The Impact of Mega Events on Local Politics; Lynne Rienner: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. The Global Street Comes to Wall Street, Possible Futures. Social Science Research Council. 2011. Available online: http://www.possible-futures.org/2011/11/22/the-global-street-comes-to-wall-street/ (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Keymolen, E.; Voorwinden, A. Can we negotiate? Trust and the rule of law in the smart city paradigm. Int. Rev. Law, Comput. Technol. 2020, 34, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T.S. Landscape and justice: The case of Greeks, space and law. Landsc. Res. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaloš, J.; Kašparová, I. Landscape memory and landscape change in relation to mining. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 43, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, C. Landscapes of Freedom; JSTOR, University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Adie, B.A.; De Bernardi, C. Oh my god what is happening? Historic second home communities and post-disaster nostalgia. J. Heritage Tour. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Boym, S. The Future of Nostalgia; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Löwenthal, D. Past Time, Present Place: Landscape and Memory. Geogr. Rev. 1975, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Cai, L.A.; Day, J.; Tang, C.-H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H. Authenticity and nostalgia—Subjective well-being of Chinese rural-urban migrants. J. Heritage Tour. 2019, 14, 506–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Weate, P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise; Smith, B., Sparkes, A.C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist 2013, 26, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Meilutis, M. Šimašius: Pliažas Lukiškių Aikštėje Įrengtas, Kad Galėtume Džiaugtis Iškovota Laisve. Delfi. 2020. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/news/daily/lithuania/simasius-pliazas-lukiskiu-aiksteje-irengtas-kad-galetume-dziaugtis-iskovota-laisve.d?id=84603629 (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Įžymybės Apie Lukiškių Aikštės Paplūdimį: Perspjovė Net Auksinio Liūto Merginas. Diena.lt. 2020. Available online: https://m.diena.lt/naujienos/laisvalaikis-ir-kultura/zvaigzdes-ir-pramogos/lukiskiu-aikstes-papludimys-sukele-izymybiu-diskusijas-974072 (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Grigaliūnaitė, V. Lukiškių aikštę iš Vilniaus ketinama atimti įstatymu, R.Šimašius tai vadina noru nubausti Vilnių. 15 min. 2020. Available online: https://www.15min.lt/naujiena/aktualu/lietuva/lukiskiu-aikste-is-vilniaus-ketinama-atimti-istatymu-registruotos-tai-lemsiancios-pataisos-56-1380388?comments&copied (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Tracevičiūtė, S. Seime svarstant Lukiškių aikštės likimą pylėsi ne tik argumentai, bet ir užuominos apie erotines fantazijas. 15 min. 2020. Available online: https://www.15min.lt/naujiena/aktualu/lietuva/seime-svarstant-klausima-del-lukiskiu-aikstes-likimo-nuskambejo-pasvarstymas-apie-r-karbauskio-erotines-fantazijas-56-1381624?copied (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Butkus, T.S. Apie Laisvę ir Urbanistiką: Keturios Pastabos dėl Lukiškių Pliažo. 2020. Available online: http://pilotas.lt/2020/06/26/architektura/apie-laisve-ir-urbanistika-keturios-pastabos-del-lukiskiu-pliazo/ (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Tiškus, G. Investigation of Representative Characteristics of Lukiškių Square in Vilnius / Lukiškių Aikštės Vilniuje reprezentacinių Savybių Tyrimas. Moksl. Liet. Ateitis 2018, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buivydas, R.; Samalavičius, A. Public Spaces in Lithuanian Cities: Legacy of Dependence and Recent Tendencies. Urban Stud. Res. 2011, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimaitė, V. Political Relationship among Monuments: Monuments as the Subject of political Debate. Politologija 2019, 96, 60–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiškus, G. Some Theoretical Essences of Lithuania Squares Formation Kai Kurios Teorinės Lietuvos Aikščių Formavimo Esmės. Moksl. Liet. Ateitis 2016, 8, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- LRT.lt. Lithuania Decides to Lift Quarantine. Available online: https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1187146/lithuania-decides-to-lift-quarantine (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Brazaitytė, E. Beach Vibes in Vilnius: Largest City Square Turns into Pop-Up Beach 17. Vilnius.lt. 2020. Available online: https://vilnius.lt/en/2020/06/25/beach-vibes-in-vilnius-largest-city-square-turns-into-pop-up-beach/ (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Linden, G. Profesorius G. Čaikauskas Apie Pliažą Lukiškių Aikštėje: Tai—Labai Netikėtas Akibrokštas, Spectrum. 2020. Available online: https://structum.lt/straipsnis/profesorius-g-caikauskas-apie-pliaza-lukiskiu-aiksteje-tai-labai-netiketas-akibrokstas/ (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- LRT.lt. Vilnius Dismantles Controversial ‘Open Beach’ on Central Square. Available online: https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1223537/vilnius-dismantles-controversial-open-beach-on-central-square (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Butkus, T.S. Miestas kaip įvykis. Miesto koncepcijos kaita ir kultūrinė miesto funkcija. Lit. ir Men. 2006, 7, 3106. [Google Scholar]

- Rubavičius, V. Miesto tapatumas ir išskirtinumas globalizacijos sąlygomis. Urban. ir Archit. 2005, 24, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lukšyte, I.; Architektas, T. Grunskis: Viešosios Erdvės Keičiasi Lėtai, Bet ne Žmonių Lūkesčiai. 2020. Available online: https://sa.lt/architektas-t-grunskis-viesosios-erdves-keiciasi-letai-bet-ne-zmoniu-lukesciai/ (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Grunskis, T. Lukiškių aikštės estetinės transformacijos problema Europos miesto aikščių tradicijos diskurse. Urban. Archit. 2000, 24, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Butkus, T.S. Potential of City’s Cultural Function and Its Forms of Expression in Urban. J. Arch. Urban. 2007, 31, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, T.D.; Bates, N.R. Recapturing a Sense of Neighbourhood Since Lost: Nostalgia and the Formation of First String, a Community Team Inc. Leis. Stud. 2006, 25, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Campbell, G. ‘Nostalgia for the future’: Memory, nostalgia and the politics of class. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2017, 23, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberger, M. Why alternative memory and place-making practices in divided cities matter. Space Polity 2019, 23, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, P. Tourism experiences as the remedy to nostalgia: Conceptualizing the nostalgia and tourism nexus. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Medappa, K. Nostalgia as Affective Landscape: Negotiating Displacement in the “World City”. Antipode 2020, 52, 1688–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreal City Council. Montreal Charter of Rights and Responsibilities. 2005. Available online: https://ville.montreal.qc.ca/pls/portal/docs/page/charte_mtl_fr/media/documents/charte_montrealaise_english.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Scott, A.J.; Storper, M. The Nature of Cities: The Scope and Limits of Urban Theory. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherington, C.; Jorgensen, A.; Walker, S. Understanding landscape change in a former brownfield site. Landsc. Res. 2017, 44, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pranskuniene, R.; Perkumiene, D. Public Perceptions on City Landscaping during the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease: The Case of Vilnius Pop-Up Beach, Lithuania. Land 2021, 10, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010032

Pranskuniene R, Perkumiene D. Public Perceptions on City Landscaping during the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease: The Case of Vilnius Pop-Up Beach, Lithuania. Land. 2021; 10(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010032

Chicago/Turabian StylePranskuniene, Rasa, and Dalia Perkumiene. 2021. "Public Perceptions on City Landscaping during the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease: The Case of Vilnius Pop-Up Beach, Lithuania" Land 10, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010032

APA StylePranskuniene, R., & Perkumiene, D. (2021). Public Perceptions on City Landscaping during the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease: The Case of Vilnius Pop-Up Beach, Lithuania. Land, 10(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010032