3.1. A Scarce Resource for Traditional Agrarian Structures

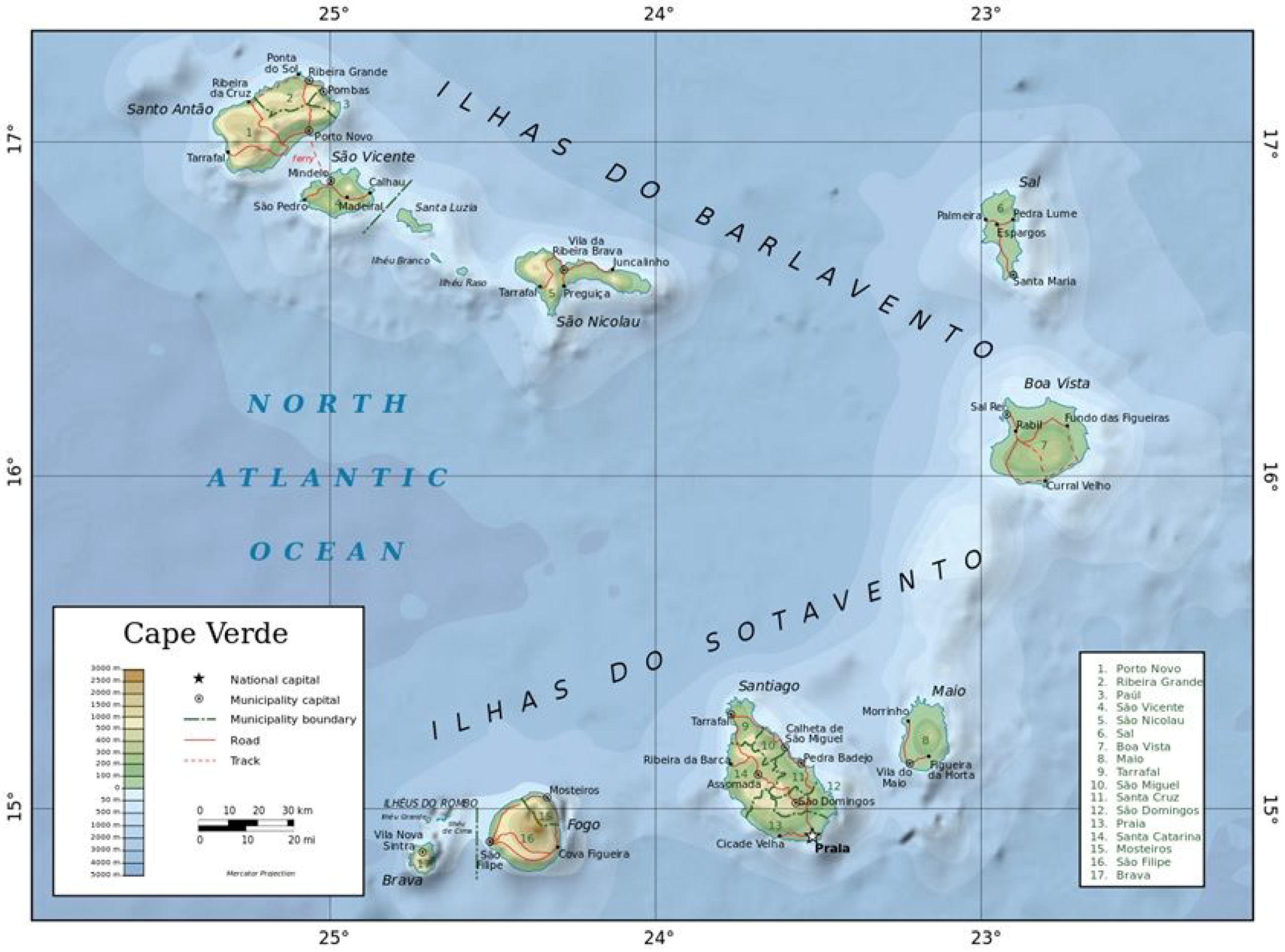

There are hardly any permanent watercourses in Cape Verde, with the exception of Santo Antäo, where springs provide an appreciable flow all year round. Weather and geo-morphological conditions mean that most of the watercourses in the valleys only run with water during the rainy season. Rainfall varies, depending on the topography and latitude of each island (see

Figure 1), so rainfall is very uneven, varying from the 475.40 mm·year

−1 that falls in Fogo to the 46.90 mm·year

−1 that falls on the island of Sal (data from the National Meteorological and Geo-physics Institute). Furthermore, the rains are highly irregular in both space and time;

i.e., from one year to the next and from one time of year to another, and they come in the form of downpours, such that some towns have all their rainfall in 2 or 3 episodes of torrential rain that cause significant damage to infrastructure and farming.

Figure 1.

Situation of the Cape Verde Archipelago. Source: Adapted from Wikimedia Commons [

19].

Figure 1.

Situation of the Cape Verde Archipelago. Source: Adapted from Wikimedia Commons [

19].

It has to be remembered that droughts are frequent in Cape Verde (

Table 1 and

Table 2). The severest of the most recent episodes was the drought of 1970, which is considered the year the current cycle started. Rigorous studies indicate that there is a decline in rainfall of about 3% [

20]. So this is a country that is vulnerable to both natural phenomena, particularly droughts, and the activities of Man, which leads to a modification of microclimates, desertification, torrential rains and volcanic eruptions like the one recorded this year (2015) on the island of Fogo.

Table 1.

Physical characteristics and rainfall in Cape Verde (averages).

Table 1.

Physical characteristics and rainfall in Cape Verde (averages).

| Island | Area (km2) | Altitude (m) | Rainfall (mm/year) (Average 1990–1998) | Rainfall (mm/year) (2004) | Average (1990–1998) | Arable land (Ha) |

|---|

| Santo Antäo | 785 | 1,979 | 263 | 36,760 | 237 | 8,800 |

| San Vicente | 230 | 750 | 79 | 82.79 | 93 | 450 |

| San Nicolau | 347 | 1,312 | 164 | 199.40 | 142 | 2,000 |

| Sal | 221 | 406 | -- | 46.90 | 60 | 220 |

| Boa Vista | 628 | 387 | 77 | 57.06 | 68 | 500 |

| Maio | 275 | 437 | 84 | 139.00 | 150 | 660 |

| Santiago | 1,007 | 1,394 | 234 | 297.50 | 321 | 21,500 |

| Fogo | 460 | 2,829 | 344 | 475.40 | 495 | 5,900 |

| Brava | 63 | 776 | 191 | 201.20 | 268 | 1,060 |

Table 2.

Estimated Surface and subterranean waters (in millions of m3/year).

Table 2.

Estimated Surface and subterranean waters (in millions of m3/year).

| Island | Surface Waters | Subterranean Waters |

|---|

| PNUD [14] | BURGEAP [13] | UNDP [14] | Master Plan |

|---|

| Santo Antäo | 97.0 | 29.2 | 54.0 | 28.6 |

| San Vicente | 2.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| San Nicolau | 14.0 | 4.3 | 9.0 | 4.2 |

| Sal | 2.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| Boa Vista | 6.0 | 0.4 | 5.0 | 1.6 |

| Maio | 4.0 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 2.1 |

| Santiago | 108.0 | 21.9 | 55.0 | 42.4 |

| Fogo | 87.0 | 21.9 | 42.0 | 42.0 |

| Brava | 8.0 | 1.64 | 5.0 | 1.9 |

| Total | 328.0 | 80.84 | 173.0 | 124.0 |

The use of surface waters on these islands is constrained by the high run-off, between 20% and 53% of the rainfall is lost, more than the loss from evaporation [

18], so there is little catchment or storing. Most of the water used in Cape Verde agriculture comes from subterranean waters. Much of the 99,409 m

3·day

−1 flow tapped comes from nearly 2304 springs, including galleries. Somewhat less comes from the 1173 wells or the 238 “

furos”, larger-sized wells, going down to a depth of between 50 and 120 m and with a diameter of 30 cm [

14].

The practice of using modern techniques to store water is a recent one in Cape Verde. Dams are concentrated on the islands of Santiago and Santo Antäo, with 15 and 64, respectively, while there are 1605 storage tanks. The public authorities have promoted and adapted traditional techniques for transporting and distributing water, and for storing it in

reservorios (tanks or ponds), such as

levadas (channels built on top of, or excavated into the rock, which direct water using artesian methods), which has made it possible to increase the area of irrigated land [

1,

16]. New infrastructure has been constructed in recent years, including the Poiläo reservoir. Strong pressure on water resources is the root cause of the proliferation of wells, causing over exploitation and placing constraints on the development of irrigated areas, especially in the coastal areas, with considerable potential for irrigation availability, by the following sources.

In a services-oriented economy (86% of GDP in 2007), the agricultural sector contributes between 6.3% in 2004 and 5% in 2007, according to the National Statistics Institute. However, the sector generates around 45% of employment [

18]. Agricultural structures vary enormously. There is direct production (independent farmers) and indirect production (in different forms such as share-croppers, lease,

etc.), irrigated land, non-irrigated land and mixed systems. The latter are perhaps the most characteristic of Cape Verde agriculture and they are to be found on most farms, especially the large ones.

Despite its small size (

sequeiro, or non-irrigated land, account for 93% of the arable land), consumption by the farming sector accounts for around 50% of the waters under management; although the differences between islands and districts are considerable. The irrigated land has always been, and remains concentrated in the hands of a few. For example, on the island of Santiago, before independence, 48% of the irrigated land (which includes ownership of the water) was in the hands of 4% of the population. After Independence, however, some properties were distributed [

1,

21] and water was nationalized in the agrarian reform, although the process was reversed in later years.

Farms relying on rainfall (sequeiro) traditionally grow mainly maize as the preferred food crop and cultural symbol of the people of Cape Verde. This crop is often combined with pulses (beans) and tubers, forming a typical multi-crop holding with many possible combinations such as tubers-maize, maize-beans, etc. These dry-land farms usually keep some domestic animals, too, such as pigs, goats or cows, to supplement the farmer’s diet.

Crops grown on irrigated land (regadío) are normally only irrigated irregularly. In this case, the predominant crops are, first and foremost, sugar cane, the oldest and most predominant crop. However, it is grown more for cultural reasons than financial ones, as it is the raw material for making grogue, the national drink; although it is true that it tolerates water shortages very well. On its own, or grown in combination with other crops, it occupies 76% of the irrigated land, but it is not exported. In second place are the tubers (potatoes, sweet potatoes and manioc), which are fundamental to the family diet in Cape Verde. Banana plantations, developed in the 20th century, are widespread and bananas can be found either on their own or grown in combination with other crops such as manioc or sugar cane. Pulses, generally grown in combination with one of the other crops mentioned, are essential for local consumption to supplement vegetables, such as carrots, cabbage, potatoes, onions, tomatoes, etc.

The Government has promoted the use of new technologies, subsidizing innovative methods (by paying for one-third the costs) in the use of water in agriculture, such as spray irrigation or drip irrigation; for all this it is often advised by international organizations like the PNUD [

14]. However, in many cases they meet with opposition from peasants who prefer traditional techniques.

As far as drinking water supply is concerned, governments have made sterling efforts to provide the population with a good water supply. The cover is 93% in cities and 74% in rural areas, enabling the country to approach the Millennium Development Goals. The water supply may be in the form of the public water network (the most widespread in cities), tanks or cisterns (widespread in the countryside). In both cases, the origin of the water can be subterranean or industrial, with desalinated water produced on practically all the islands.

There are currently five operators who provide desalinated water for the population and industry. In the main towns and cities, the water is produced and distributed by ELECTRA (National Electricity Company, Praia, Cape Verde, with a production of around 14.850 m

3 a day) [

18], a private-public partnership that also generates and supplies electricity. Elsewhere, water production and distribution is mainly guaranteed by autonomous municipal services. There are also small, private operators that run seawater desalination systems and some wells, which supply and supplement the water distribution network.

Several studies suggest that the domestic water supply is largely the responsibility of women. In isolated rural areas, especially, women are responsible for carrying water from the source to the home, often involving a journey of four or five kilometers. These are the

apanhadeiras, who carry 20 liters or more of water on their heads at a time, causing them health problems. The Government is trying to solve this situation [

22].

3.2. The Role of the State in Water Management

The way water resources are controlled and valued in Cape Verde is part of a long tradition. Productive resources are governed by a network of superimposed private and public institutions. The daily management of irrigation networks is done directly by the farmers, official bodies or by way of mutual-help arrangements or informal institutions, through which families can exchange favors with neighbors, as happens with all other farm work. This intersection of different institutional levels can be complementary.

Since Independence (1975), successive Cape Verde governments have promulgated a raft of laws on water management. Portuguese colonial legislation, although it was repealed, has had a profound impact on later legislation. The old colonial Water Code, the principles of which were derived from Roman Law and the Civil Code [

23], consecrated private ownership of water. Later on, although the intention of the Cape Verde government was to break away from the colonial view and individualist principles to facilitate access to ownership for small farmers and share-croppers, first of all as “

pos útil” and later as “

pos plena”, private individuals were also allowed to drill wells in special, duly justified cases, where the water was to be used for farming.

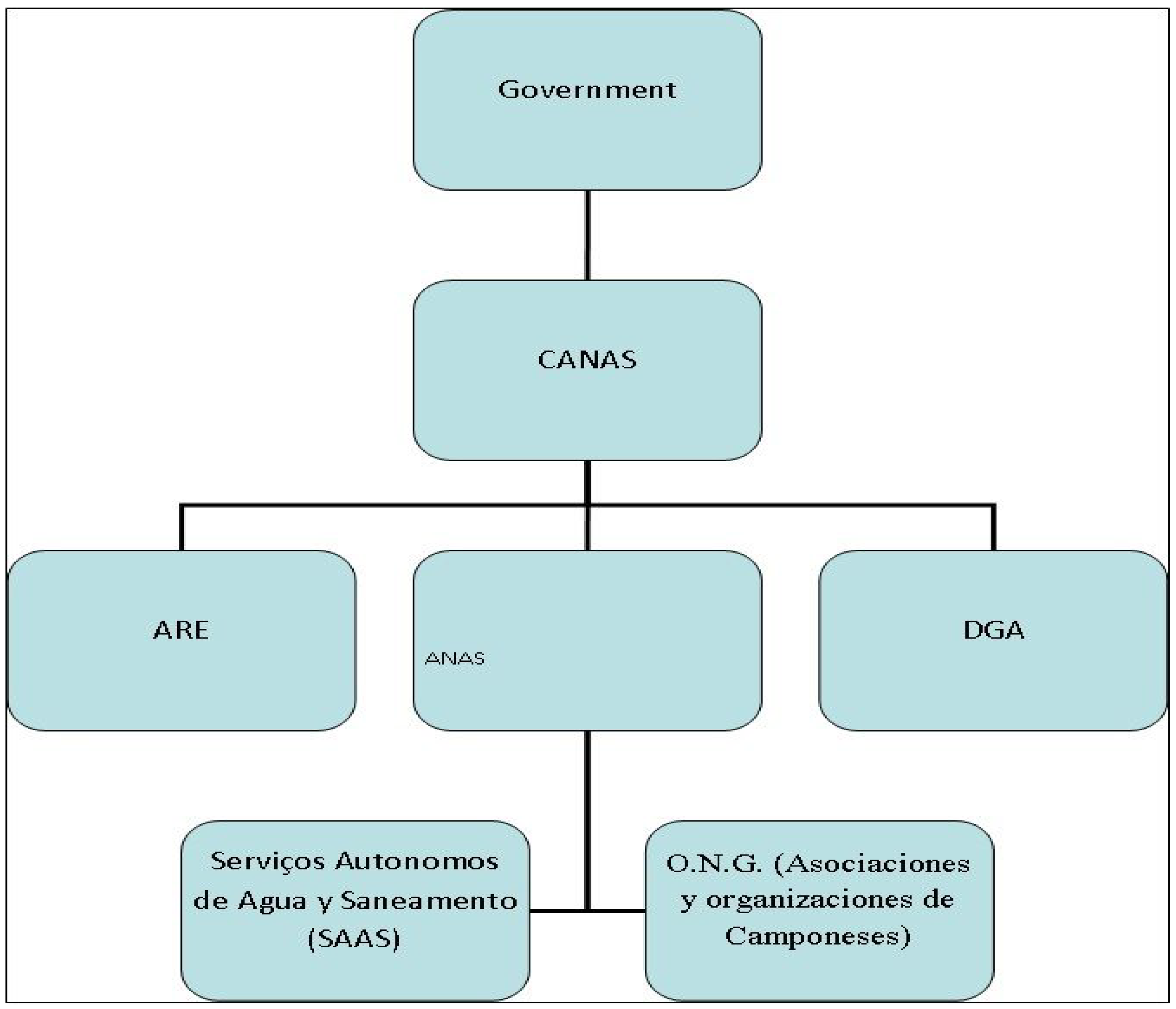

The institutional model has gradually consolidated since independence (1975). The first

Código de Agua (1984) gave water management to the

Junta dos Recursos Hídricos (JRC); it was founded by the

Instituto Nacional de Gestión de Recursos Hídricos (National Water Resource Management Institute) (1992) (INGRH, as it is known in Portuguese), whose plan, develop and protect water resources. The new Water Code contemplates the principle of the public domain of water resources and water-related works, although a later review (1999) gave rise to private initiative. The most significant bodies that have been set up in the process are the Conselho Nacional de Aguas (National Water Council) (CNAG); while the

Agencia de Regulaçao Económica (Economic Regulation Agency) (ARE) (2003) is an administrative institution with regulatory, oversight and sanctioning powers that promotes social cohesion and protects consumer interests and rights; the

Direçao Nacional do Ambiente (National Environment Directorate, DGA) has environmental regulation functions. Finally, since 2013, the INGRH has given way to the

Agência Nacional da Água e do Saneamiento (National Water and Sanitation Agency) (ANAS), answerable to the

Conselho Nacional da Água e do Saneamento (National Water and Sanitation Council) (CANAS). (See

Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Institutionalization of water administration in Cape Verde. Source: Adapted from Borges [

24]. Made on the premises.

Scheme 1.

Institutionalization of water administration in Cape Verde. Source: Adapted from Borges [

24]. Made on the premises.

Non-governmental organizations and community associations, on the other hand, make up what is known as the N.G.O. Platform, which participates in development programs, along with the “

organizaçones de camponeses”—farmers’ organizations—particularly where there is traditional irrigation farming, taking part on a different scale in all stages of the water supply and sanitation projects [

18].

The Municipal Water and Sanitation Services (SAAS in Cape Verde) manage water production. They normally operate supply systems made up of a “furo”, or large wells, with an electric pump or diesel generator, linked to a tank or pool (reservorio), from where the water is distributed to the population through distribution points (chafariz) or small home networks. These bodies face several problems arising from a confusing pricing policy and lack of co-ordination, as the tariffs are approved by the Câmaras Municipais and other similar entities, but the criteria they use are far from clear. What is true, is that as an incentive for introducing technology, water is supplied at subsidized prices, which seems to be a good decision. This policy benefits farms that use water-saving technology, such as drip irrigation. On the other hand, water from gravitational systems (nascentes, galleries and others) or from private wells do not pay any tariff at all.

Thus, the State has been and remains the “

maitre d’oeuvre” in handling water resources in Cape Verde [

1]. Although the water catchment infrastructures are run by private individuals or producer associations, the legal owners of the

furos and most of the pumping equipment is the State. In these cases, the government has left the management in the hands of the “

Comissoes de Água” (Water Committees), with a government delegate on them from the

Ministério de Desenvolvimiento Rural (Rural Development Ministry). Then the “

Comissoes de Moradores” (Neighborhood Committees) have been given the authority to regulate the operation of the streams and springs. It has fostered the participation of farmers and social groups, perhaps in a ritual nod to their African heritage, giving the leading role to local and community agencies, some of which are run by the local councils and others are not. Reality, however, reveals that water management in the hands of these bodies has not always been conducted in line with a system of granting licenses to run a concession [

18], with clear cases of lack of control coming to light.

In short, the Cape Verde state takes measures to decentralize irrigation management and governance. This policy has given greater responsibility to municipal authorities and it has also stimulated the participation of the local population through communities. So the trend is as follows: (a) to affirm the municipal services as managers of water services; (b) partial privatization; and (c) and in rural areas, the development of community-type management structures.

3.3. Formal and Informal Institutions: Associations

As we have already said, water management in some countryside areas of Cape Verde has much in common with other territories with an arid climate, be they island or mainland territories. It is true that the difficulties of access and storage place constraints on water stakeholders, although the uncertainty is tempered by technological developments. It is hardly surprising that communal solidarity in the use of water is similar to what can be seen in some areas of the semi-arid mainland Sahel, showing that the form of management is clearly influenced, not only by the availability of water, but also by the socio-cultural context in question (embeddedness). In the case in question, solidarity arises from the extensive family relations and neighborliness.

But, in Cape Verde, water distribution varies depending on whether it is obtained naturally from

nascentes or tapped by opening wells or galleries. Even if the State intended to centralize the management and administration of water resources, the owners of the

nacentes still consider the water as private property, and they look after its management themselves, by means of informal arrangements with private individuals. This water, generally used in farming, is tied to ownership of the land, in accordance with the system inherited from colonial times, without any substantial modification since independence. Hence, it is controlled and managed within a scheme of private ownership, and distribution is made through agreements and arrangements between the farmers who own it. However, these have been unable to organize efficient institutions, such as those in the Canary Islands, to quote a nearby [

4,

5,

25].

In this case, the farmers manage the waters through an individualist system of sharing out the resources. Users’ Associations scarcely exist, or have only recently been set up, ignoring to a large extent the recommendations of the co-operations programs, such as, for instance, the one rolled out by a U.S. mission in the Paul Valley [

16]. The comparison with other territories is unfavorable: in the Canary Islands, for example, the system of Heredades and Communities is more efficient. They are private institutions that are nowadays admitted by the Administration [

25]. In the Canary Islands, the systems of

Heredades o Comunidades de Agua are in the origin of the associations of owner of water for agriculture. Due to a management that represents the community of proprietors, they are capable of having a structure in order to implement projects, to arbitrate and to negotiate. On the contrary, in Cape Verde, there is no real organization of water management. The State has come across the resistance of the former owners and, although it has made a dedicated effort to promote programs to modify the way water resources are managed and how domestic water is controlled, few people pay it much respect.

Thus, individualism is the norm, especially in Santa Antäo and the other windward islands, as farmers are very reluctant to give up their water easily, even if they have more than they need, they would rather flood their lands, following the principle of “

quanto mais agua, melhor” (the more water the better), as is frequently heard in the Cape Verde countryside, leading to clearly adverse effects for the community and squandering of water [

26].

The situation is different in the

furos and wells. Most of this water is administered by local communities or farmers’ associations. It must be pointed out that the State has been more successful in this case: it has fostered community action, promoted the activity of communities and associations of

camponeses and local bodies. Although informal practices persist, the result of the cultural influence of their African roots, such as

djunta-mó [

27,

28], a form of helping one another in Cape Verde, an African legacy that literally means to get together and join hands in a common effort to achieve major objectives.

In customary management, growers re-interpret and adapt communal uses and the customs of helping one another, combining the irrigation calendário with the practice of djunta-mo, especially in Santiago and other leeward islands, where the Africa influence is greater. This custom of helping one another is also a response to the difficulties represented by the omnipresent physical environment, appearing in the form of downpours or cycles of drought that systematically destroy vital resources, frequently causing widespread destruction and major famine; hence, it is natural to encourage defensive strategies to preserve resources. To some extent, they adapt to the principles of water ethics with the community-management system, which, albeit somewhat idealized, does involve non-passive populations who are aware of both their rights and duties and of the lasting importance of water. Making local communities responsible in rural areas is a primordial issue for all poor countries with few resources, like Cape Verde.

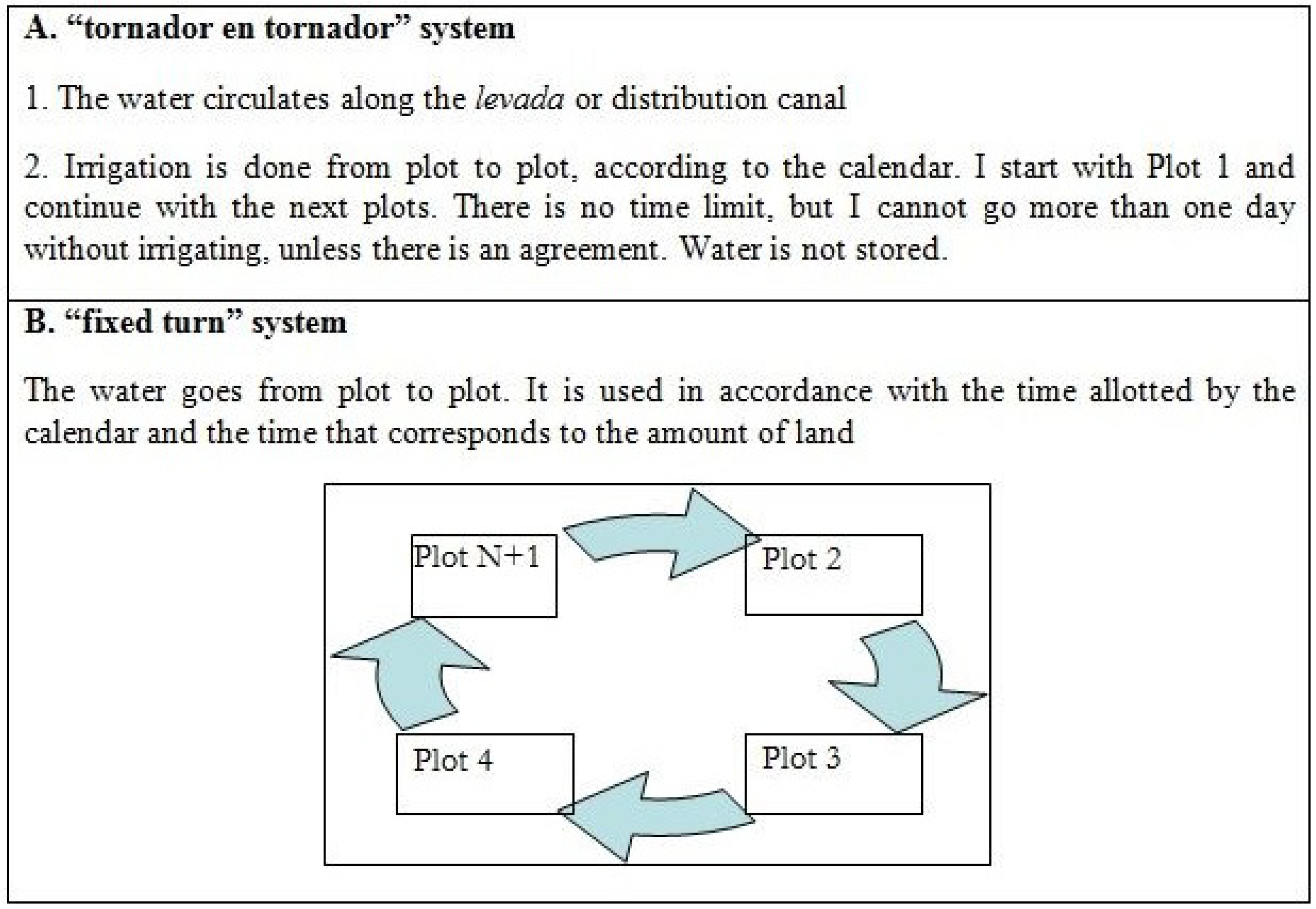

3.4. Water Distribution Systems: The Calendar

In both kinds of practices,

i.e., whether the water comes from

furos or from

nascentes, irrigation water is distributed in accordance with the amount of land, albeit with slight variations depending on the tradition and the place in question. To organize this, a calendar is drawn up, whereby water is provided for a time, either by fixed rotations, with each neighbor receiving a specific number of hours, or each neighbor can use the water until he, or she, has flooded his/her land. It is a system that is similar to the

dulas, or irrigation shifts, used in several places on the Spanish and Portuguese mainland, in the Canary Islands, in North Africa and in San Antonio, Texas, in this case as a legacy of the Canary Island emigrants that have settled there since the end of the 18th century, or in Mexico [

6]. There are two sytems: (a) “

tornador en tornador”, irrigation is done from plot to plot, there is no time limit; and (b) “

fixe turs”, the water is used with the time allotted (See

Scheme 2).

Once established, the number of days is maintained as “use and custom”, passed down from one generation to another, hence establishing the amount of water there is in the hands of a given property. The calendar system is characterized by providing the water at times with a long interval between them: only 6% of the distribution has an interval of seven days or less. Fourteen percent on the other hand, have an interval of 8 to 15 days, 71% from 15 to 30 days and 10% have an interval of over 30 days [

14,

27].

Scheme 2.

Kind of calendar used for water distribution in Cape Verde. Source: Information provided by Paulina Costa Fortes and Manuel Baptista, Representative and Engineer from MRD/IHGRH, respectively in Porto Novo (Santo Antäo) and the interview occurred in Porto Novo on 4 December 2013.

Scheme 2.

Kind of calendar used for water distribution in Cape Verde. Source: Information provided by Paulina Costa Fortes and Manuel Baptista, Representative and Engineer from MRD/IHGRH, respectively in Porto Novo (Santo Antäo) and the interview occurred in Porto Novo on 4 December 2013.

Traditionally, the “

meirinho” is responsible for distributing the water in accordance with the “

Código de Posturas” (as in Portugal, the documents that brought together a set of municipal by-laws throughout the public sector were originally known as a “

Código de Postura”). In other words, in accordance with the number of hours each owner is entitled to. He or she is also responsible for levying sanctions and for enforcing the rulings of the Municipal Corporation or Local Board. The possibility of levying sanctions on transgressors is one of the necessary, but not sufficient, conditions for the community system to work properly and prevent the problem of “scroungers” [

2].

When water is privately owned, the most frequent option chosen is to flood the “

tajos” that the plot is divided into. This way, the water can be used on the land for a very long period of time [

27]. There are obviously several problems with this method, particularly squandering resources. The most frequent crop grown is the one that best adapts to this system. This explains why they continue to grow sugar cane, although it requires a lot of water, according to interviewees, e.g., José Manuel Pires Ferreira, Chairman of the AmiPaul Association (interview the 6 December 2013), opinion corroborated in other interviews.

The water from most of the “

furos” is distributed by the pump-man, or the civil servant who distributes the water according to the calendar. In this case, the most commonly-used way of distributing the water is access once a month for enough hours, depending on the land that the farmer has in cultivation, but if his rightful share is more than he needs at that time, he can store it in a pond, or give it to someone else [

16,

26,

27].

This water is often provided as a loan, or “troca de agua”, a system of helping each other that is similar to the Djunta-mó system. This is an agreement between owners, who consider that they are donating part of their right by giving their turn to someone else, which leads to sharing the water. One owner gives the surplus water that he owns to a neighbor and waters the neighbor’s lands on the days when it is the former’s turn to irrigate his, for instance, when the flow of water (mae d’água) is abundant, allowing the land to be irrigated in less time. Exchanges are frequent within the (extended) family, between brothers, uncles and nephews, etc., and it is a practice that allows for a moderation or modulation of the calendar system.