Short Global History of Fountains

Abstract

:1. Prolegomena

Nullusenim fons non sacer.(There is no spring which is not sacred),Servius Marius Honoratus, 4th century AD, Rome.

2. Minoans and Ancient Egyptians

2.1. Water Distribution Systems

- (a)

- Underground Transportation of Water: This (underground = unseen) system may have been intended for use by a restricted group of people or for a specific activity, which in turn may be indicative of ritual use of water [9].

- (b)

- Transportation of Good Quality Water. The evidence also suggests that the pipes probably fed fountains in open areas of the palaces which were not part of the domestic distribution system, according to several scholars [10].

2.2. Fountains

2.3. Non-European Ancient Civilizations (from 3000 Onwards)

“The earliest surviving carved water basin, dating from around 3000 BC, was discovered at the site of Tello, one of the cities of Mesopotamia. At Mari, another of the most important cities, a stone fountain figure dating from around 2000 BC was discovered. The figure can be considered a prototype for the kind of fountains made in gardens for thousands of years thereafter: a female goddess holding a base into which water is piped to cascade forth, symbolizing the source of all life, the ultimate creative force of the garden.”[15]

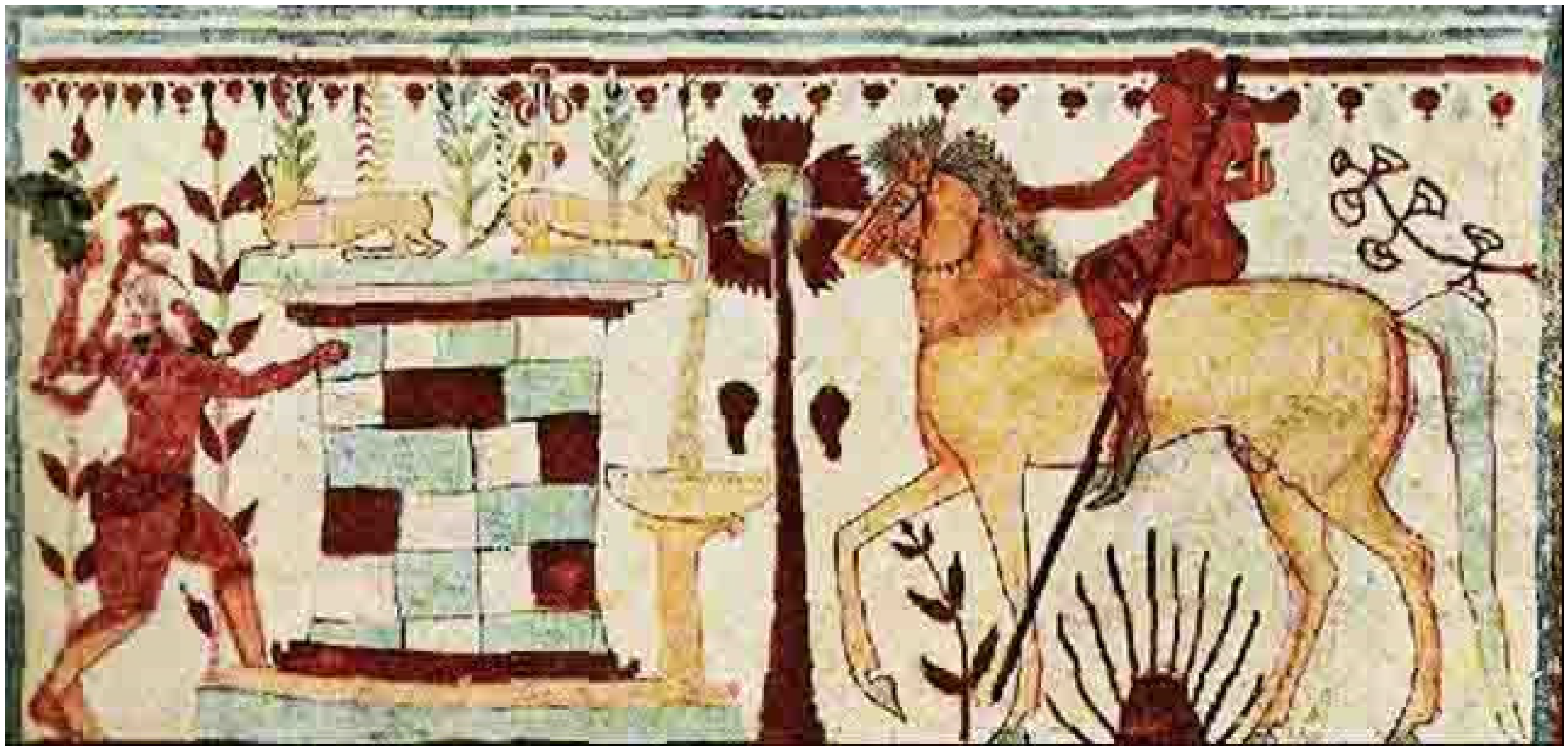

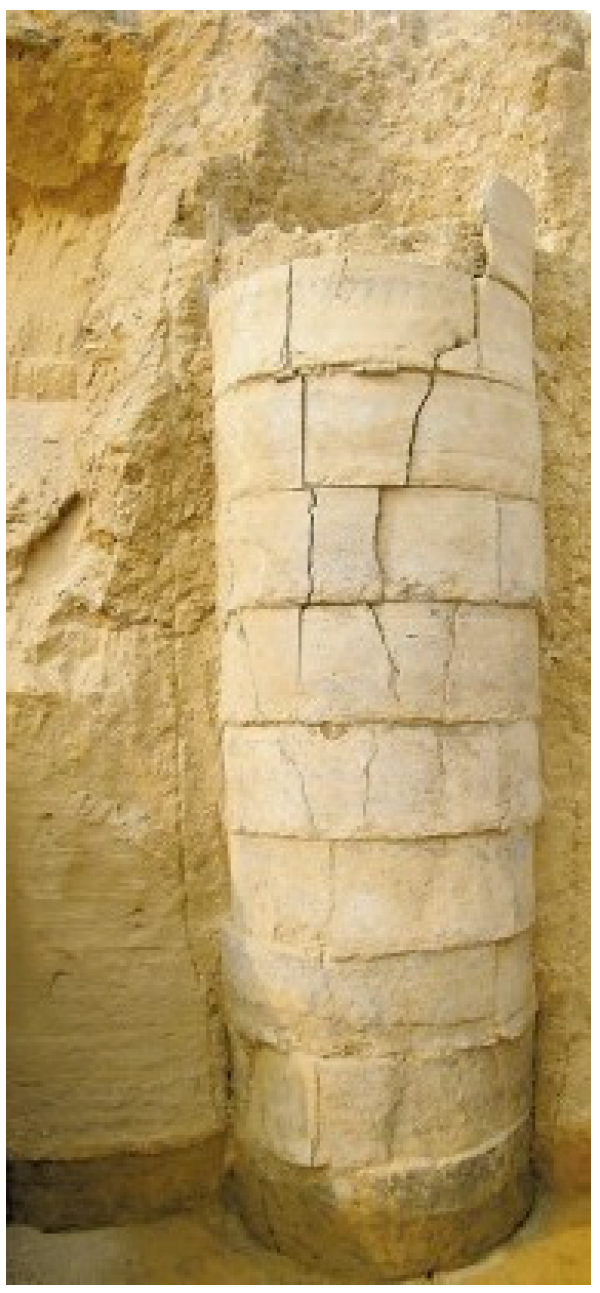

3. Etruscan Civilization (ca. 800 BC–200 AD)

4. The History of Wells and Fountains in Early Chinese Dynasties

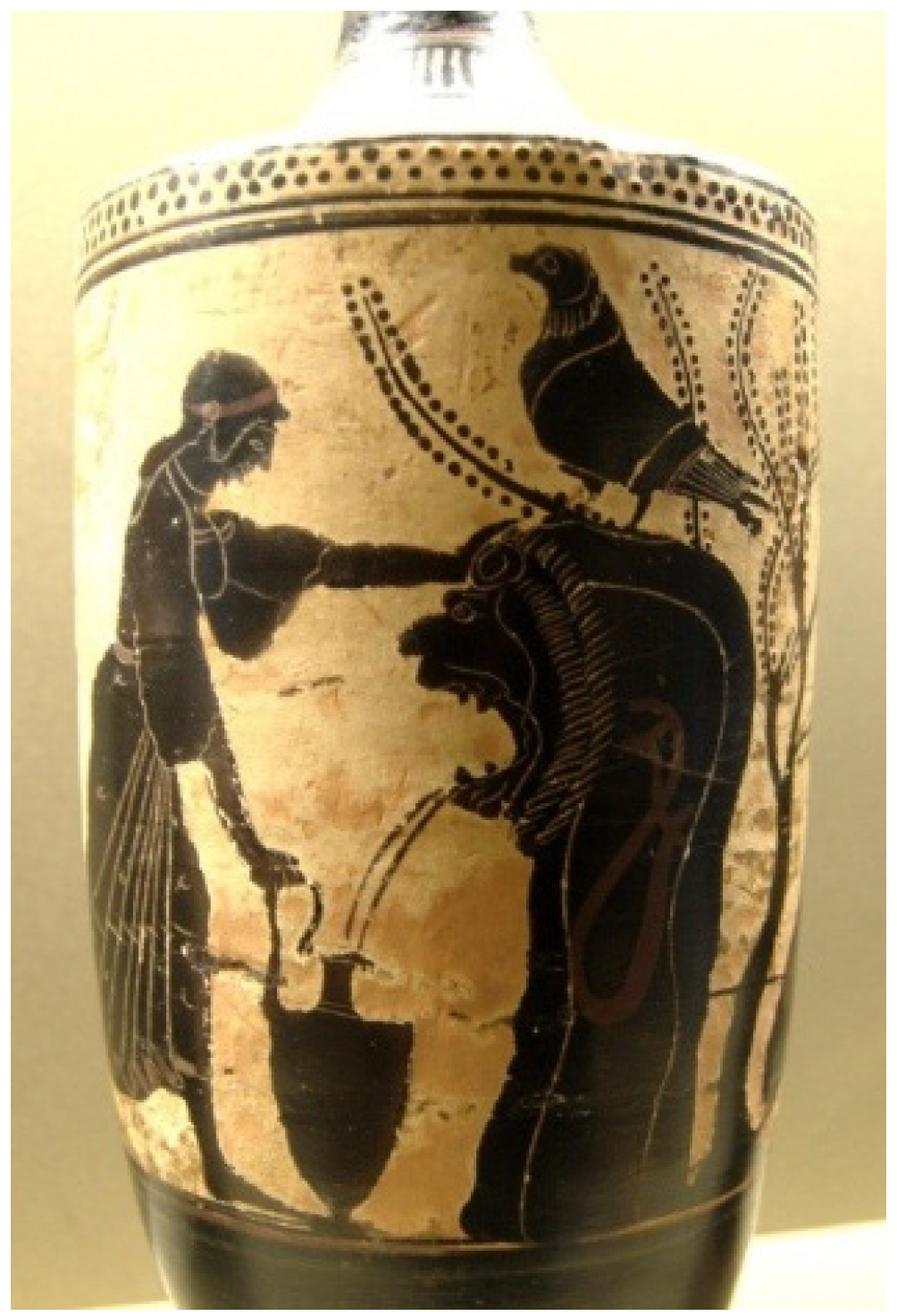

5. Greco-Roman European Classical Antiquity

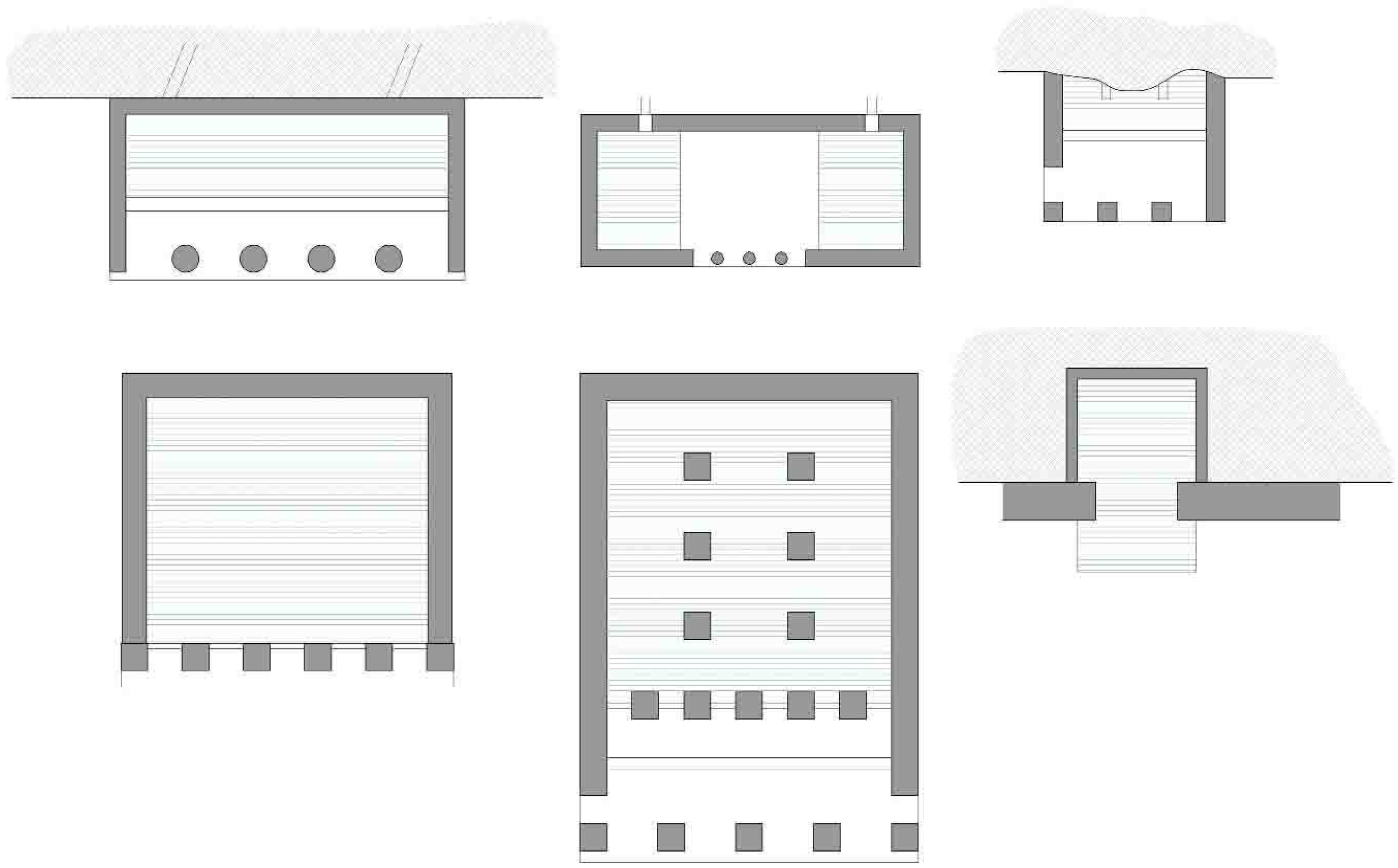

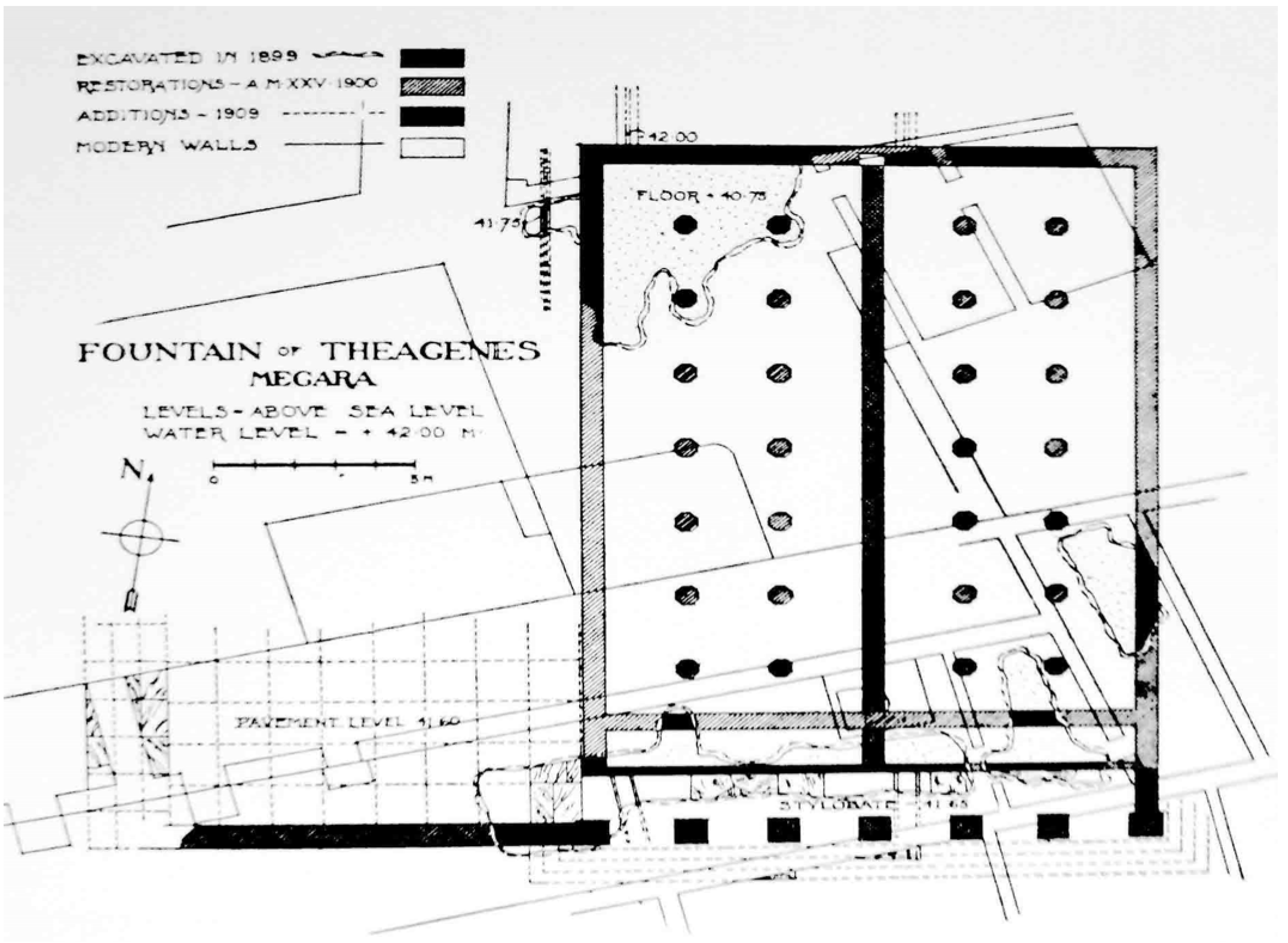

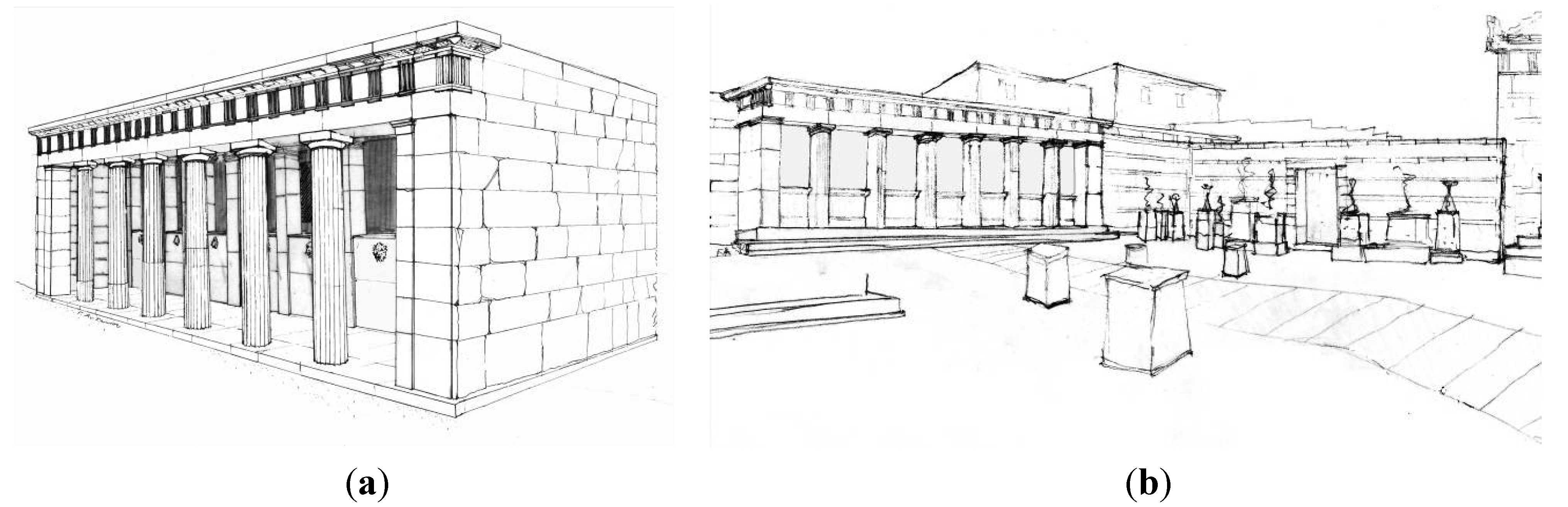

5.1. The Classical and Hellenistic periods (ca.5thc.–1stc. BC)

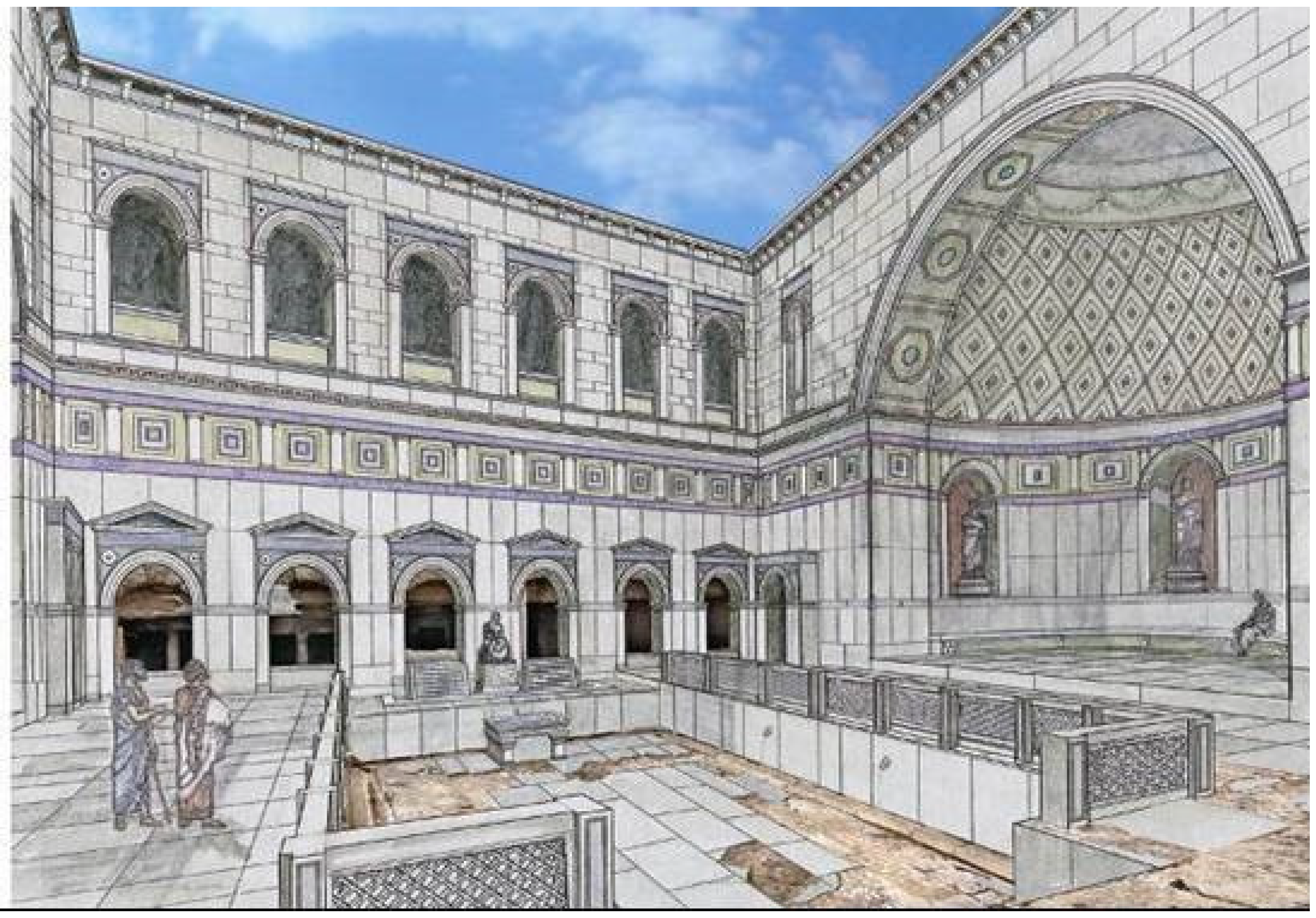

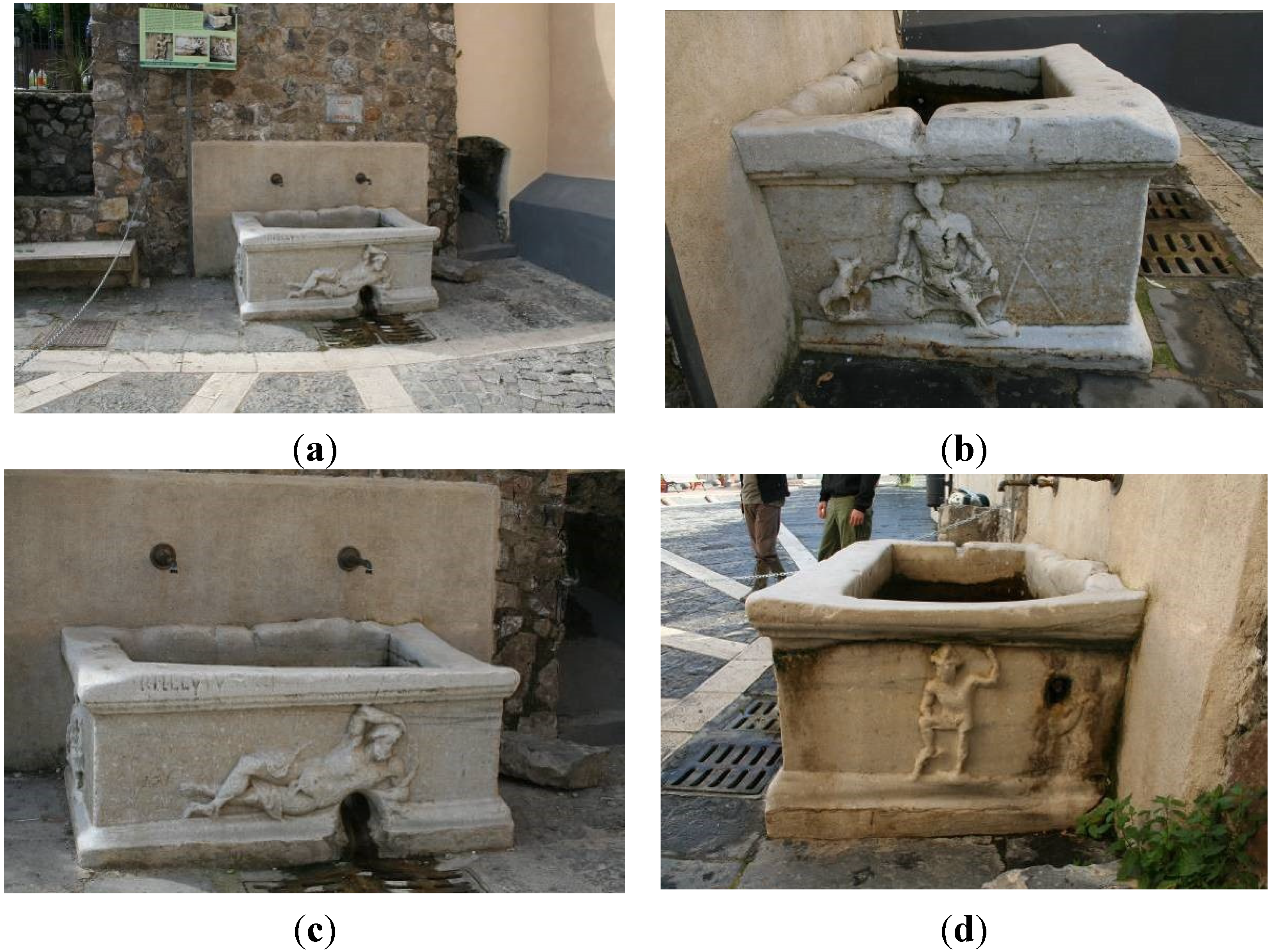

5.2. Roman Period (4th c. BC–4th c. AD)

6. Medieval Times

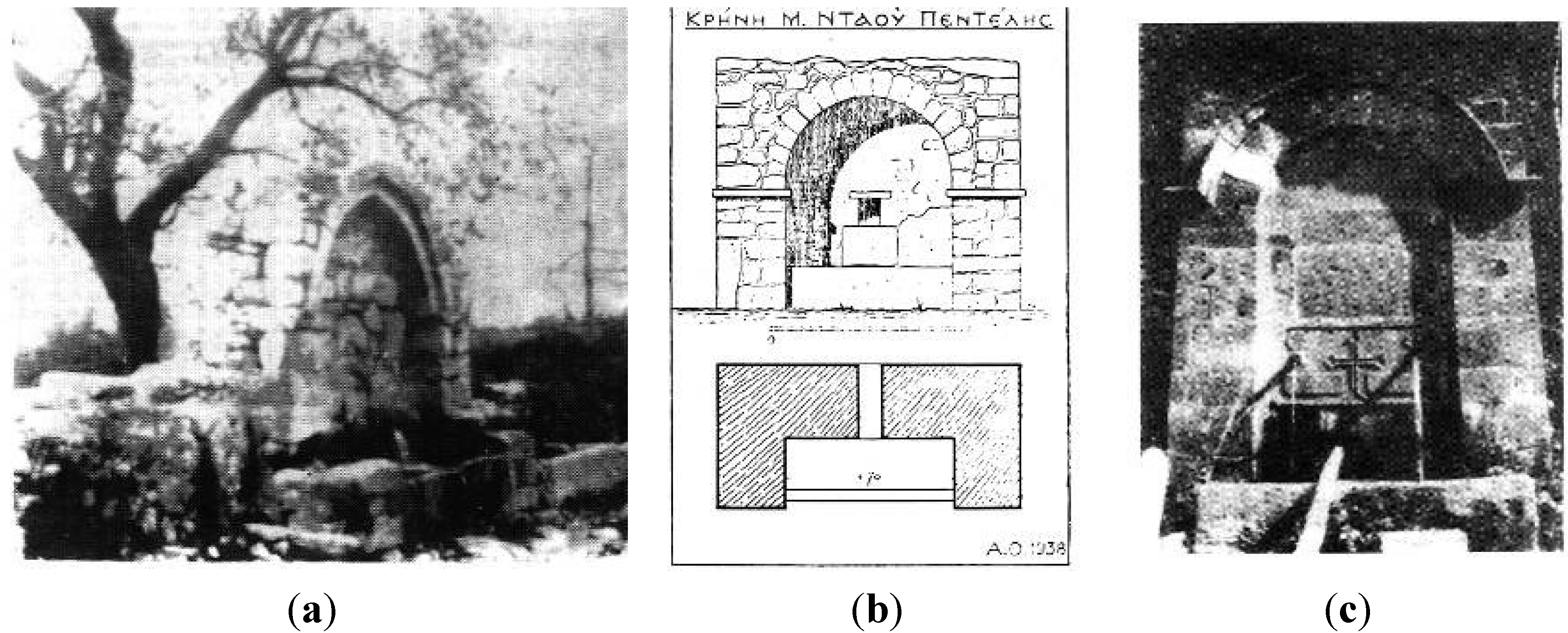

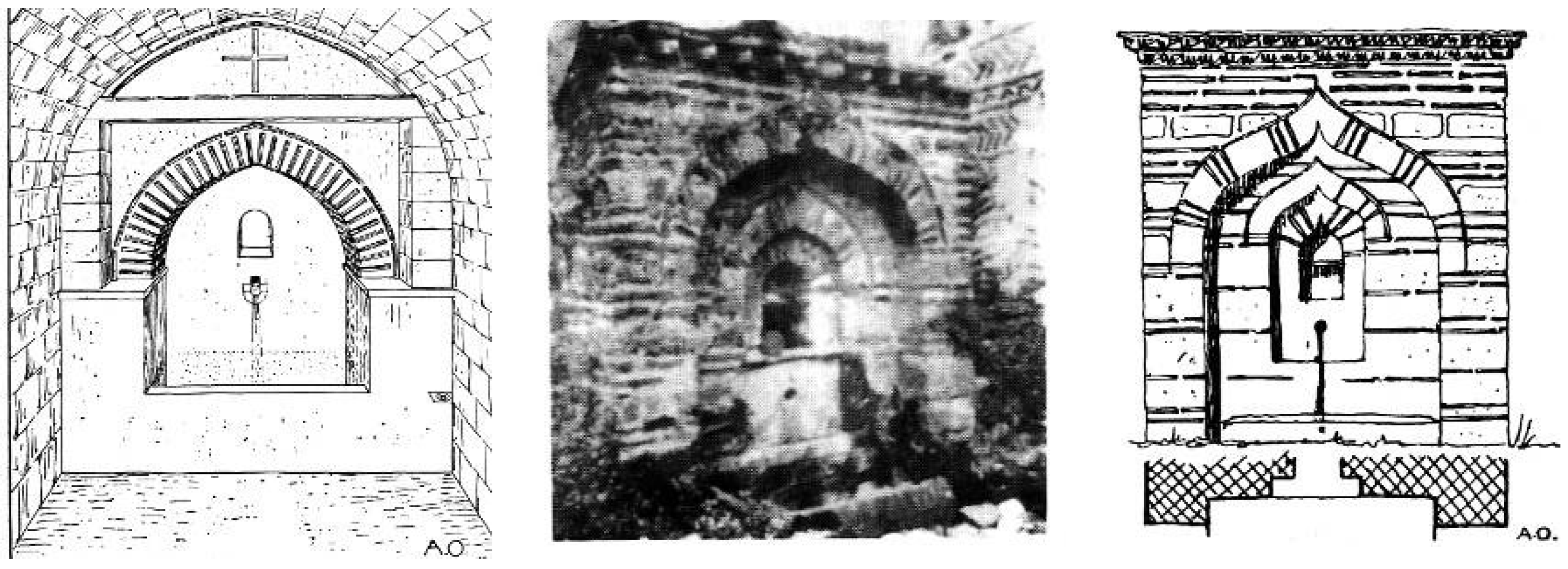

6.1. The Byzantine Period (ca. 4th c–15th c. AD)

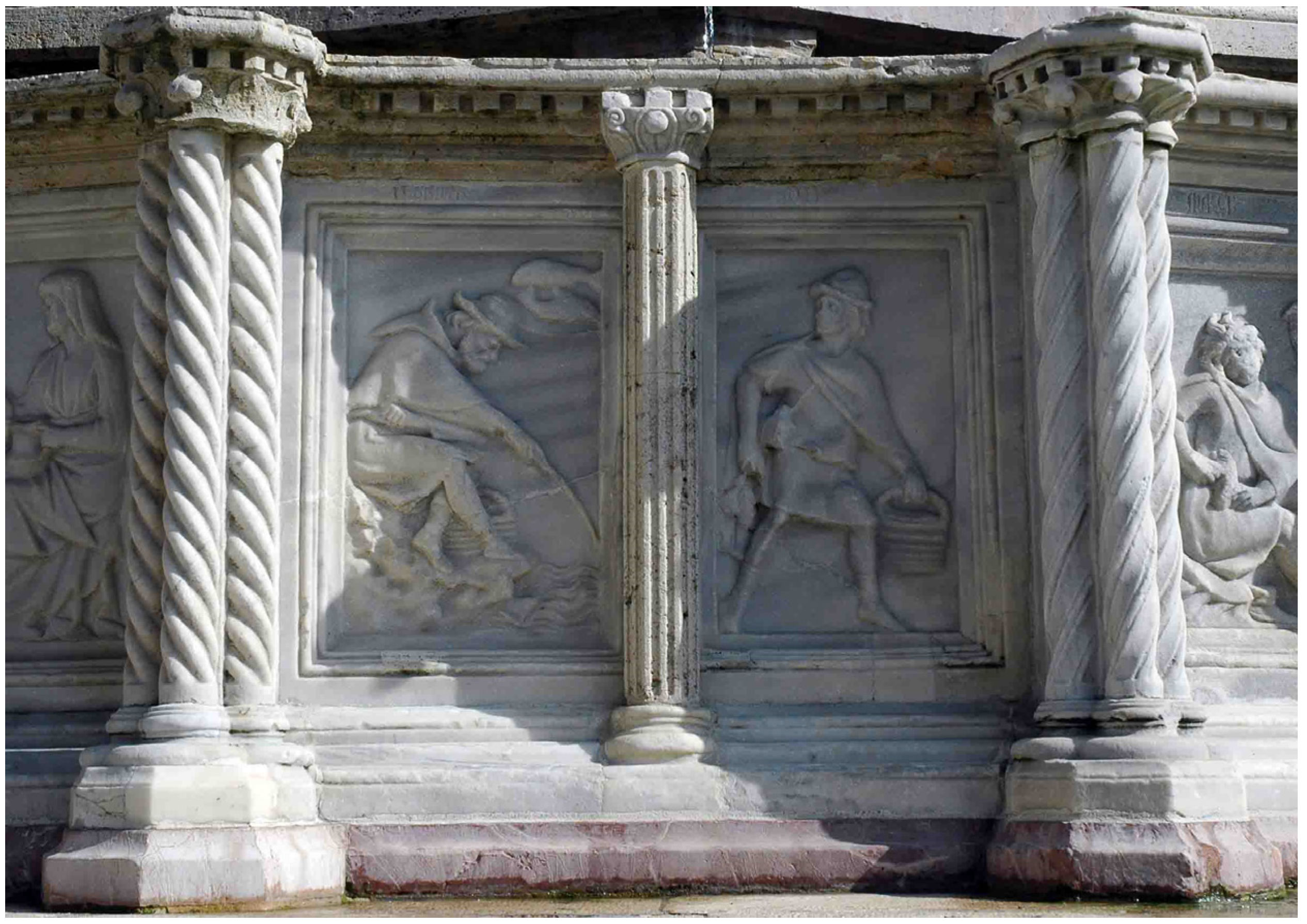

6.2. Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Times in Western Europe (ca. 450–1700)

6.3. Fountains and Islam

“We made from water every living thing.”(Qur’an 21:30)

“And it is He who created the heavens and the earth in sixth days, and his Throne was upon the water.”(Qur’an 11:7)

“He sends down saving rain for them when they have lost all hope and spreads abroad His mercy.”(Qur’an 25:48)

7. Modern Times

7.1. The Ottoman Period

7.2. Evolution of Fountains in Late Chinese Dynasties

7.3. Industrial Times

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

- (a)

- Throughout history, fountains have been an essential part of water supply that provides water resources sustainability for the survival and well-being of humans. Thus, ancient fountains should be considered, not only historical artifacts, but also potential models for sustainable water technologies now and in the future.

- (b)

- Ancient water technologies, including fountains and well- or cisterns-like fountains, were characterized by simplicity, ease of operation, and lack of complex controls, which makes them more sustainable. However, they have lost some of their importance for modern water supply purposes in the developed parts of the world, whereas they are more applicable in the developing parts of the world [8].

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mays, L.W.; Koutsoyiannis, D.; Angelakis, A.N. A brief history of urban water supply in antiquity. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2007, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Spyridakis, S.V. Major Urban Water and Wastewater Systems in Minoan Crete, Hellas. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2013, 13, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Histoire des Jardins; Ouest, S. (Ed.) PREVOT, Philippe: Bordeaux, France, 2006. (In French)

- SAMIRAD. Saudi Arabia Market Information Resource Directory. Available online: http://www.saudinf.com/index.htm (accessed on 21 March 2015).

- Hynynen, A.J.; Juuti, P.S.; Katko, T.S. Water Fountains in the World scape; Hynynen, A.J., Juuti, P.S., Katko, T.S., Eds.; International Water History Association (IWHA): Delft, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Koutsoyiannis, D.; Papanikolaou, P. On the geometry of the Minoan water conduits. In Proceedings of the 3rd IWA International Symposium on Water and Wastewater Technologies in Ancient Civilizations, Istanbul, Turkey, 22–25 March 2012; pp. 172–177.

- Evans, S.A. The Palace of Minos at Knossos: A Comparative Account of the Successive Stages of the Early Cretan civilization as Illustrated by the Discoveries, (Vol. I–IV); Macmillan and Co.: London, UK; pp. 1921–1935.

- Angelakis, A.N. The History of Fountains and Relevant Structures in Crete, Hellas. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2015. in Press. [Google Scholar]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Spyridakis, S.V. The status of water resources in Minoan times: A preliminary study. In Diachronic Climatic Impacts on Water Resources with Emphasis on Mediterranean Region; Angelakis, A.N., Issar, A.S., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Chapter 8; pp. 161–191. [Google Scholar]

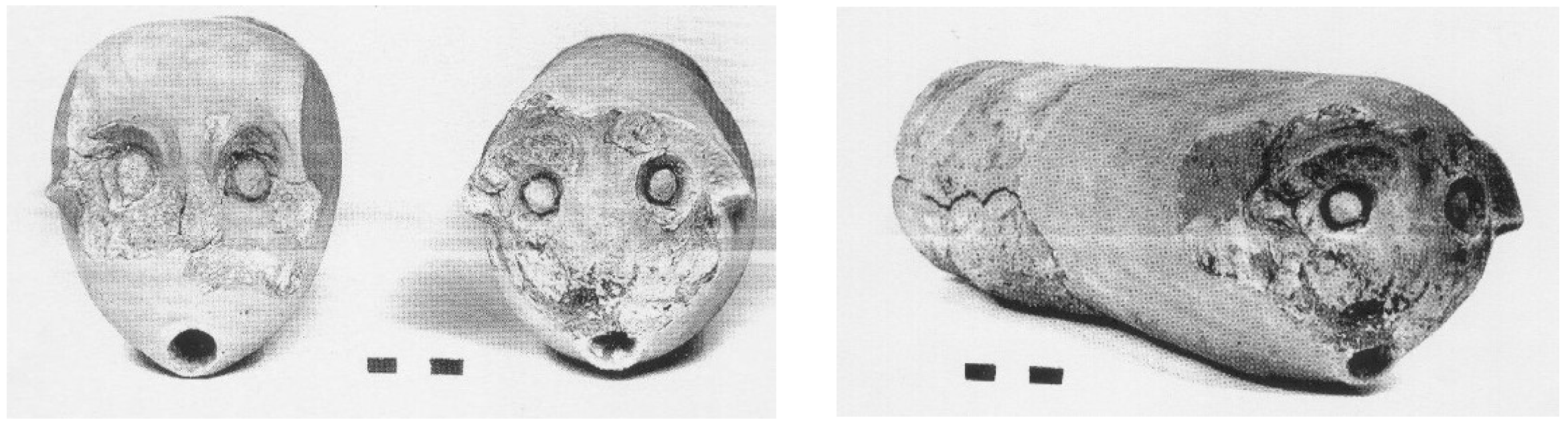

- Platon, E. Minoan terracotta water spouts. In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress of Cretan Studies, Rethymnon, Greece, 25–31 August 1991; pp. 767–775. (In Greek)

- Angelakis, A.N.; Dialynas, M.G.; Despotakis, V. Evolution of water supply technologies in Crete, Greecethrough the centuries. In Evolution of Water Supply throughout Millennia; Angelakis, A.N., Mays, L.W., Koutsoyiannis, D., Mamassis, N., Eds.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2012; Chapter 9; pp. 227–258. [Google Scholar]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Kavoulaki, E.; Dialynas, M.G. Sanitation and Stormwater and Wastewater Technologies in MinoanEra. In Evolution of Sanitation and Wastewater Management through the Centuries; Angelakis, A.N., Rose, J., Eds.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2013; Chapter 1; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Floods, J. Water Management in Neopalatial Crete and the Development of the Mediterranean climate. Master’s Thesis, The University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, P. Pseira IX: The Archaeological Survey of Pseira Island Part 2; INSTAP Academic Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst, B.R. Fountains; Kingston University: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, A.T. Roman Aqueducts & Water Supply, 2nd ed.; Gerald Duckworth: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, V.; Dragoni, W. Opere Arcaiche per il controllo del territorio: Gli emissari sotterranei artificiali dei laghi Albani. In Gli Etruschi Maestri di Idraulica; Bergamini, M., Ed.; ELECTA: Venezia, Italy, 1991; pp. 43–60. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Bersani, P.; Canalini, A.; Dragoni, W. First results of a study of the Etruscan tunnel and other hydraulic works on the “Ponte Coperto” stream (Cerveteri, Rome, Italy). Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 10, 561–569. [Google Scholar]

- Howard Hayes, S. Etruscan Cities & Rome; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1967; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiani, A. Le fontane nei santuari d'Etruria. In Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari Dell'Italia Antica; Fina, G.D., Ed.; Edizioni Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2012; Volume XIX, pp. 265–292. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Inghirami, F. Pitture di Vasi Fittili, Volume 2; Nabu Press: Fiesole, Italy, 1833. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Agguato di Achille a Troilo. Available online: http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomba_dei_Tori#mediaviewer/File:Etruscan_mural_achilles_Troilus.gif (accessed on 21 March 2015).

- Jiao, J.J. A 5600-year-old wooden well in Zhejiang Province, China. Hydrogeol. J. 2007, 15, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Old Han Well Found in the Worksite. Yeng Zhao Night Daily, 30 April 2010.

- Liu, S. A Exploring on Form of Chinese Old Well. Agric. Archaeol. 1991. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Polyxene Louvre. Available online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Polyxene_Louvre_F366.jpg (accessed on 21 August 2013).

- Elderkin, G.W. The Fountain of Glauce at Corinth. Am. J. Archaeol. 1910, 14, 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WaterHistory Home Page. Available online: http://www.waterhistory.org/ (accessed on 21 August 2013).

- Hellner, N.H. Κρήνη του Θεαγένους στa Mέγαρα; Nastou: Athens, Greece, 2009. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, G.P. Ancient Greek Lavatories: Operation with Reused Water. In Ancient Water Technologies; Mays, L.W., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, H.; Wycherley, R.E. The Athenian Agora, The Agora of Athens: The History; Shape and Uses of an Ancient City Center: Athens, Greece, 1972; pp. 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Castalian Spring. Available online: http://wikipedia.org/wiki/Castalian_Spring (accessed on 21 March 2015).

- Frontin. Les Aqueducs de la Ville de Rome, Translation and Commentary by Pierre Grimal; Société d’édition Les Belles Lettres: Paris, France, 1944. (In France) [Google Scholar]

- Pace, P. Gli Acquedotti di Roma; Art Studio S. Eligio: Roma, Italy, 1983; p. 330. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Dragoni, W. Rome’s Fountains: Beauty and Public Service from Geology, Power and Technology. In Water Fountains in the Worldscape; Hynynen, A.J., Juuti, P.S., Katko, T.S., Eds.; IWHA: Delft, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, V.; Dragoni, W. Opere Idrauliche Ipogee nel Mondo Romano: Origine, Sviluppo e Impatto nel Territorio. L’UNIVERSO 1989, LXIX, 100–137. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Pounds, N.J.G. An Historical Geography of Europe 450 B.C.—A, Parte 1330; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1973; p. 475. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, D. Water supply and wastewater disposal in Pompeii: An Overview. Anc. Hist. 2004, 34, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, G.C.M. Urban Water Transport and Distribution. In Handbook of Ancient Water Technology; Wikander, Ö., Ed.; BRILL: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2000; p. 741. [Google Scholar]

- De Feo, G.; Laureano, P.; Drusiani, R.; Angelakis, A.N. Water and wastewater management technologies through the centuries. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2010, 10, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, G.; Mays, L.W.; Angelakis, A.N. Water and Wastewater Management Technologies in the Ancient Greek and Roman Civilizations. In Treatise on Water Science; Wilderer, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; Volume 4, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- De Feo, G.; de Gisi, S.; Malvano, C.; Tortora, A.; del Prete, S.; Maurano, F.; Tropeano, E. The Roman aqueduct and the Helvius’ Fountain in Sant’Egidiodel Monte Albino, in Southern Italy: A historical and morphological approach. In Proceedings of the 2nd IWA International Symposium on Water and Wastewater Technologies in Ancient Technologies, Bari, Italy, 28–29 May 2009.

- Pompeii. Fountain outside VII.1.32 and VII.1.33. Excavated 1846. Available online: http://www.pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/Fountains/Fountain%2070132.htm (accessed on 21 March 2015).

- Jashemski, W.F. The Use of Water in Pompeian Gardens. In Proceedings of the 9th History of Water Management and Hydraulic Engineering in the Mediterranean Region, Pompeii, Italy, 1–8 October 1994; pp. 51–57.

- Prakoso, S. The Laurentine Villa and the Tuscan Villa of Pliny the Younger. Jurnal Ilmiah Arsitektur UPH 2006, 3, 130–142. (In Bahasa) [Google Scholar]

- Mari, Z.; Sgalambro, S. The Antinoeion of Hadrian’s Villa: Interpretation and Architectural Reconstruction. Am. J. Archaeol. 2007, 111, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L.; Corazza, A. L’acqua e la città in epoca antica. In “La Geologia di Roma, dal Centro Storico alla Periferia”, Part I Memorie Serv. Geol. d’Italia; S.E.L.C.A: Firenze, Italy, 2008; Volume LXXX, pp. 189–219. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, L. Camillo Agrippa’s Hydraulic Inventions on the Pincian Hill (1574–1578). Available online: http://www3.iath.virginia.edu/waters/Journal5LombardiNew.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2015).

- St. John Hope, W.H.; Fowler, C.J.T. Recent discoveries in the Cloister of Durham Abbey. Archaeologia 1903, 58, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavatorium. Available online: http://www.paradoxplace.com/Photo%20Pages/Spain/Navarre_Aragon_Catalonia/Catalonia/Poblet/Images/800/Lavatorium2-Jun06-D9807sAR900.jpg (accessed on 29 April 2015).

- Lavatorium, Gloucester Cathedral Cloisters. Available online: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lavatorium,_Gloucester_Cathedral_Cloisters_-_geograph.org.uk_-_876615.jpg#file (accessed on 29 April 2015).

- Andersen, T.B.; Jensen, P.S.; Skovsgaard, C.S. The Heavy Plough and the Agricultural Revolutionin Medieval Europe; Discussion Papers on Business and Economics, No. 6/2013; University of Southern Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Dragoni, W. Some considerations on climatic changes, water resources and water needs in the Italian region south of the 43°N. In Water, Environment and Society in Times of Climatic Change; Issar, A., Brown, N., Eds.; Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 241–271. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallucci, F. La Fontana Maggiore di Perugia: Voci e Suggestioni di Una Comunità Medievale; Quattroemme: San Giovanni, Italy, 1993; p. 237. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Soletti, A. L’acquedotto medievale di Perugia. Quaderno 5—Laboratorio di Disegno Automatico, Università di Perugia; Soletti, A., Ed.; Istituto di Disegno Architettura Urbanistica: Perugia, Italy, 1992; p. 94. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio, C. Le Fontane di Roma, con Documenti e Disegni inediti; Staderini Editore: Roma, Italy, 1962; p. 309. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Cope, F. Fontane di Roma; Rizzoli Libri Illustrati, GruppoSkira: Ginevra, Switzerland, 2004; p. 207. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Rinne, K.W. The Waters of Rome: Aqueducts, Fountains, and the Birth of the Baroque City; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2011; p. 262. [Google Scholar]

- Islamonline Homepage. Available online: www.islamonline.net (accessed on 21 March 2015).

- Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Tunis: Encyclopædia Britannica. Available online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/609220/Tunis (accessed on 21 August 2013).

- Yves-Marie, A.; Christiany, J. L’Art des Jardins en Europe; Citadelles & Mazenod: Paris, France, 2006. (In France) [Google Scholar]

- Kanetaki, E. Ottoman Baths in the Greek Territory; Technical Chamber of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2004. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- The Cretan Architecture the 18th and 19th Centuries; Chryssoula Tzobanaki: Iraklion, Greece, 2005; Volume A1. (In Greek)

- Fountains of the Islamic World. Available online: http://www.watercharm-cn.com/plus/view.php?aid=165 (accessed on 21 March 2015).

- Zheng, X.Y. Meeting Place of Chinese Culture and Water: The Case of the Nine-Dragon Fountain of Yuxi City, China. In Water Fountains in the Worldscape; IWHA: Delft, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen, A.J.; Juuti, P.S.; Katko, T.S. Water Fountains in the Cityscape; Hynynen, A.J., Juuti, P.S., Katko, T.S., Eds.; American Public Works Association: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Trafalgar Square. Available online: http://www.destination360.com/europe/uk/trafalgar-square.php (accessed on 10 April 2013).

- Handbook of Water Kiosks from the Site of Federutility. Available online: http://www.federutility.it/openAttachment.aspx?IDFILE=04a49bf6-60a4-4467-b659-fb0d7f4c2038 (accessed on 22 April 2015). (In Italian)

- Bond, T.; Roma, E.; Foxon, K.M.; Templeton, M.R.; Buckley, C.A. Ancient water and sanitation systems—Applicability for the contemporary urban developing world. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 67, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juuti, P.S.; Antoniou, G.P.; Dragoni, W.; El-Gohary, F.; De Feo, G.; Katko, T.S.; Rajala, R.P.; Zheng, X.Y.; Drusiani, R.; Angelakis, A.N. Short Global History of Fountains. Water 2015, 7, 2314-2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7052314

Juuti PS, Antoniou GP, Dragoni W, El-Gohary F, De Feo G, Katko TS, Rajala RP, Zheng XY, Drusiani R, Angelakis AN. Short Global History of Fountains. Water. 2015; 7(5):2314-2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7052314

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuuti, Petri S., Georgios P. Antoniou, Walter Dragoni, Fatma El-Gohary, Giovanni De Feo, Tapio S. Katko, Riikka P. Rajala, Xiao Yun Zheng, Renato Drusiani, and Andreas N. Angelakis. 2015. "Short Global History of Fountains" Water 7, no. 5: 2314-2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7052314

APA StyleJuuti, P. S., Antoniou, G. P., Dragoni, W., El-Gohary, F., De Feo, G., Katko, T. S., Rajala, R. P., Zheng, X. Y., Drusiani, R., & Angelakis, A. N. (2015). Short Global History of Fountains. Water, 7(5), 2314-2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/w7052314