Impact of Floods on Livelihoods and Vulnerability of Natural Resource Dependent Communities in Northern Ghana

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Aims and Objectives

1.2. Some Terminologies

- Vulnerability is the state of susceptibility to harm from exposure to stresses associated with environmental and social change and from the absence of capacity to adapt [5]. Vulnerability consistently focuses on socio-ecological systems. The concept of a social-ecological system reflects the idea that human action and social structures are integral to nature and hence any distinction between social and natural systems is arbitrary. It is the multi-level interactions between system components (livelihoods, social structures and agricultural policy) that determine system vulnerability. In all formulations, the key parameters of vulnerability are the stress to which a system is exposed, its sensitivity, and its adaptive capacity. Algebraically, we could define vulnerability to be a function of the character, magnitude, and rate of climate variation:OrVulnerability = Exposure + susceptibility - resilience

- The IPCC report of 2001 defines sensitivity as ‘the degree to which a system is affected, either adversely or beneficially, by climate-related stimuli. The effect may be direct (e.g., a change in crop yield in response to a change in the mean, range, or variability of temperature) or indirect (e.g., damages caused by an increase in the frequency of flooding)

- Adaptive capacity is the ability to plan, prepare for and implement adaptation measures. Factors that determine adaptive capacity of human systems include economic wealth, technology and infrastructure, information, knowledge and skills, institutions, equity and social capital. Adaptive capacity cannot be measured. Adaptive capacity is often represented by social capital and other assets [6]

- Coping strategies refer to people’s agency, ingenuity and abilities to help one another individually and collectively from time to time in order to meet their hierarchical needs [7]. They grow out of a recognition of the risk of an event occurring and of established patterns of response. They seek not just survival, but also the maintenance of other human needs such as the receiving of respect, dignity and the maintenance of family, household and community cohesion.

- Social capital refers to connections within and between social networks as well as connections among individuals. It is usually meant to boost the adaptive capacity of individuals and communities. A social network is a social structure made of nodes (which are generally individuals or organizations) that are tied by one or more specific types of interdependency, such as values, visions, ideas, financial exchange, friendship, sexual relationships, kinship, dislike, conflict or trade. Nodes are the individual actors within the networks, and ties are the relationships between the actors.

- Entitlement is a term for the access that people have to food from the sale of their labour, their own food producing activity, or via social networks, or some political claim on state resources including moral claims on international food aid [7].

- Livelihoods comprise the assets (natural, physical, human, financial and social capital), the activities, and the access to these (mediated by institutions and social relations) that together determine the living gained by the individual or household [8].

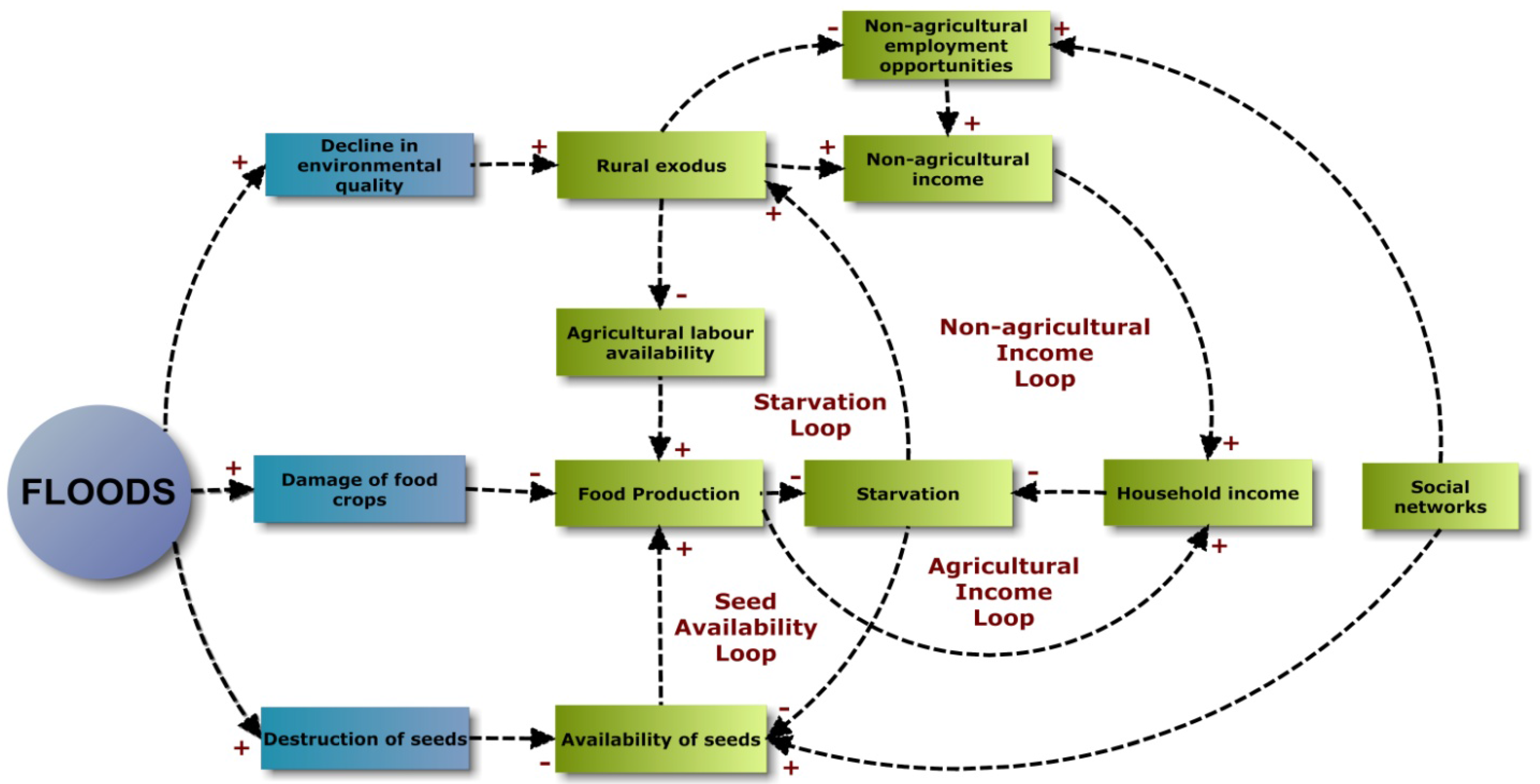

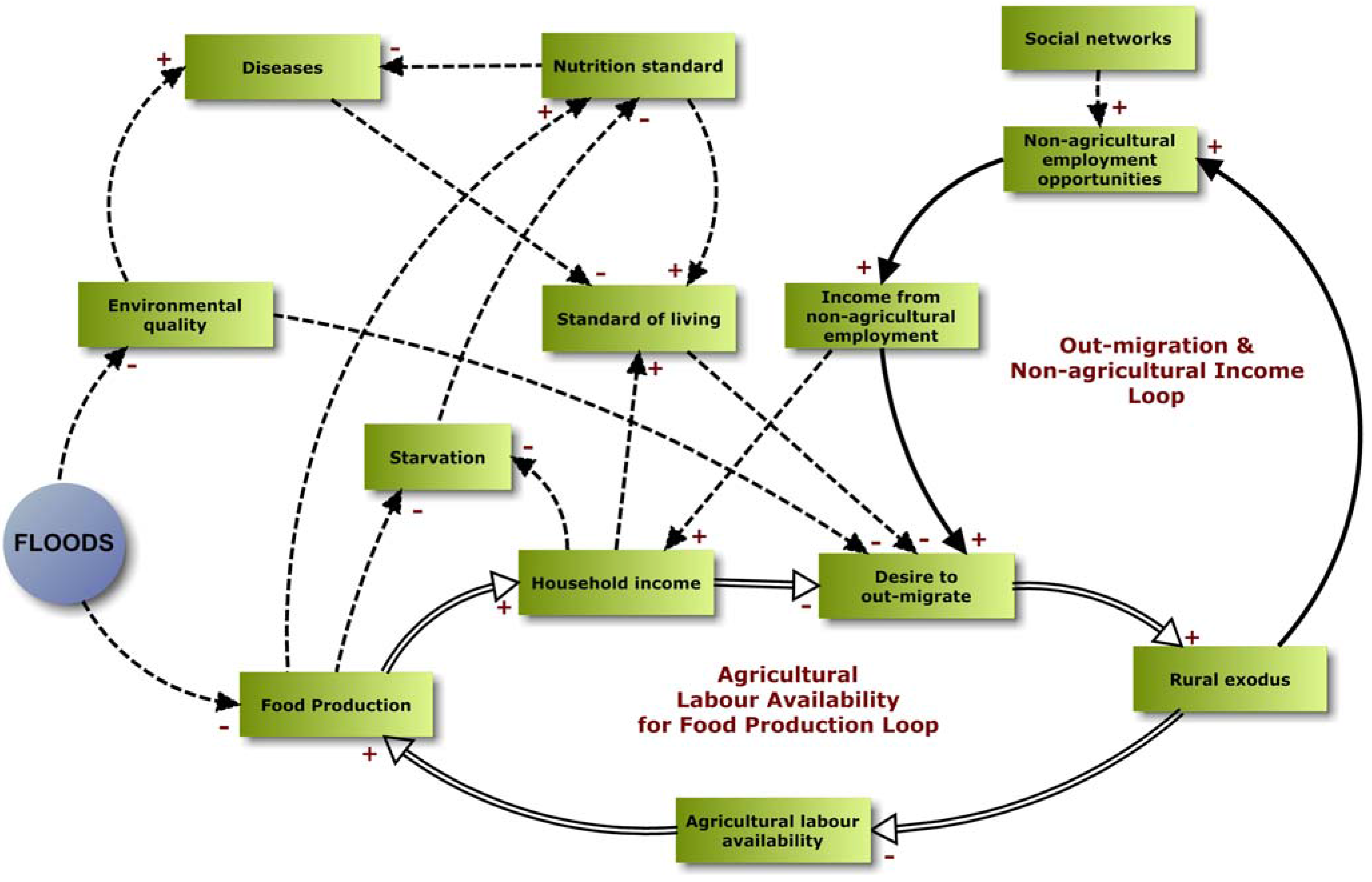

1.3. Conceptual Framework: General systems structure of the effects of floods on natural resource-dependent communities in northern Ghana

- 1-

- The existence of swamps which become breeding grounds for water-borne diseases;

- 2-

- Destruction of homes, grain stores, social and economic infrastructures by flood waters;

- 3-

- Destruction of farmlands together with crops and farm animals;

- 4-

- Accumulation of massive quantities of silt on key community structures like water supply, sewage treatment, and others which paralyzes crucial life-support and ecosystem services.

2. Materials and Methods

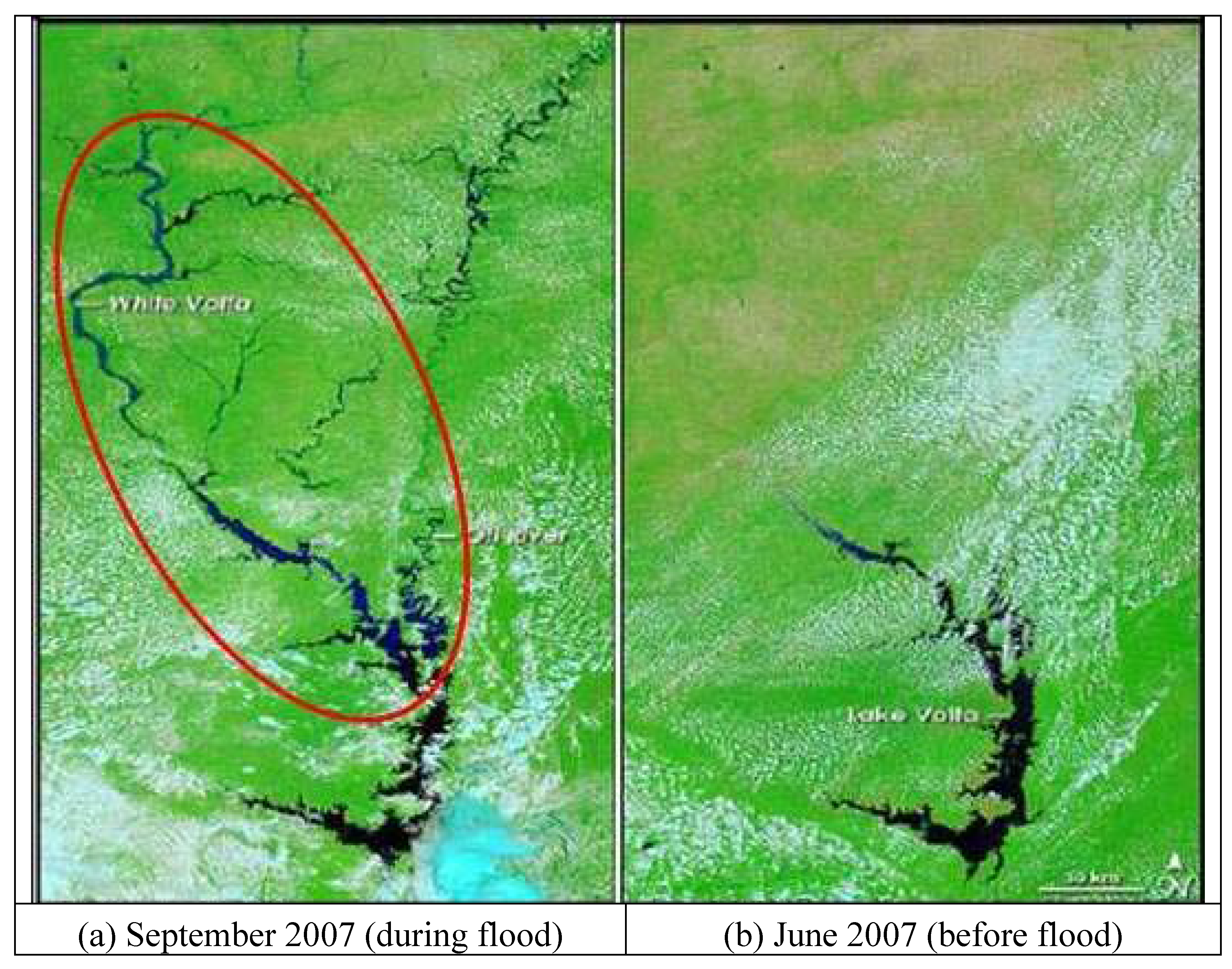

2.1. Area of Investigation

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Community Demographics

3.2. Reliance on weather information for agricultural activities and flood preparedness

| Year | Number of Respondents affectedby floods (N=220) |

| 1985 | 8 |

| 1988 | 148 |

| 1993 | 4 |

| 1998 | 6 |

| 1999 | 54 |

| 2007 | 220 |

3.3. Impact of flooding on the two communities

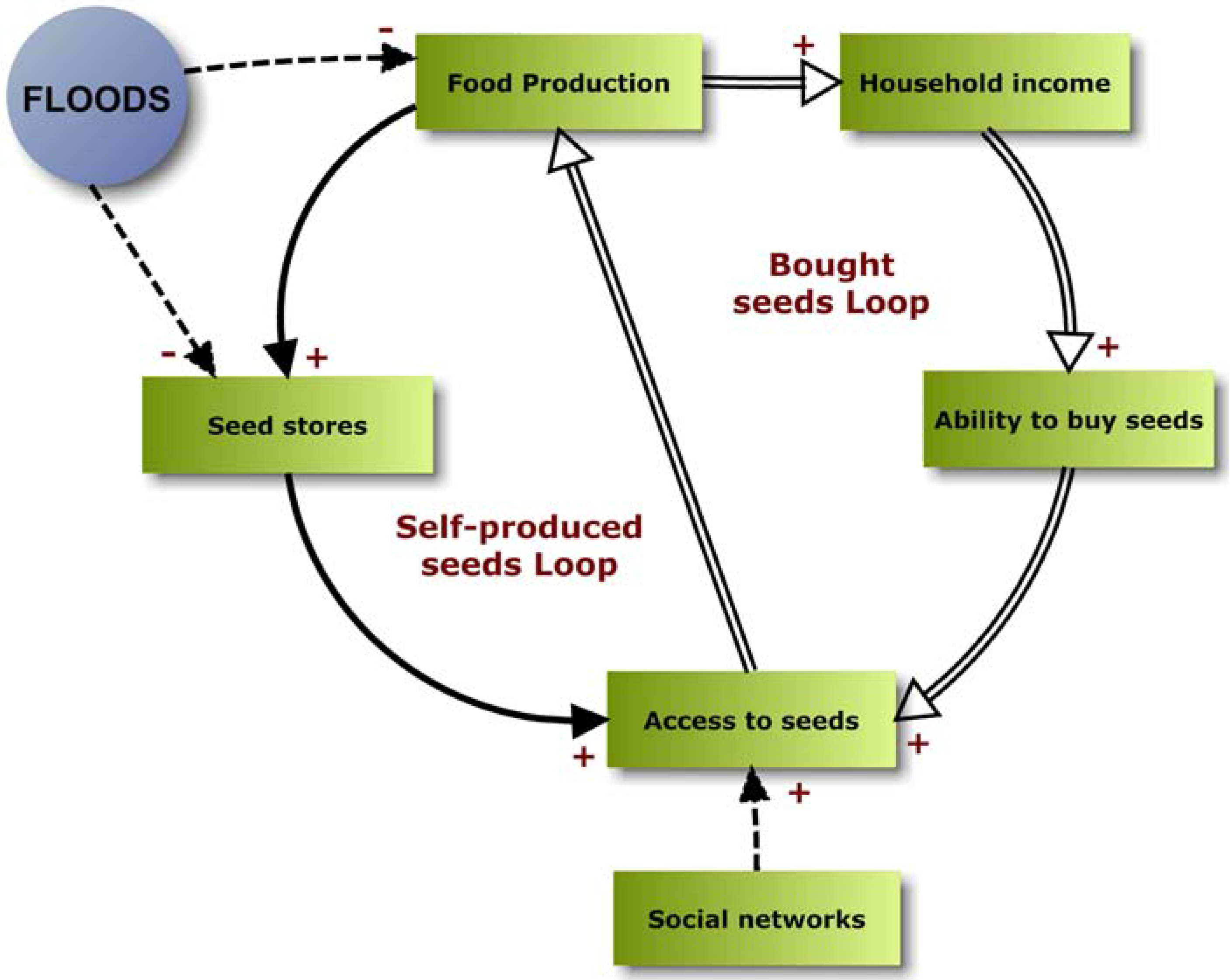

3.3.1. Floods and access to seeds

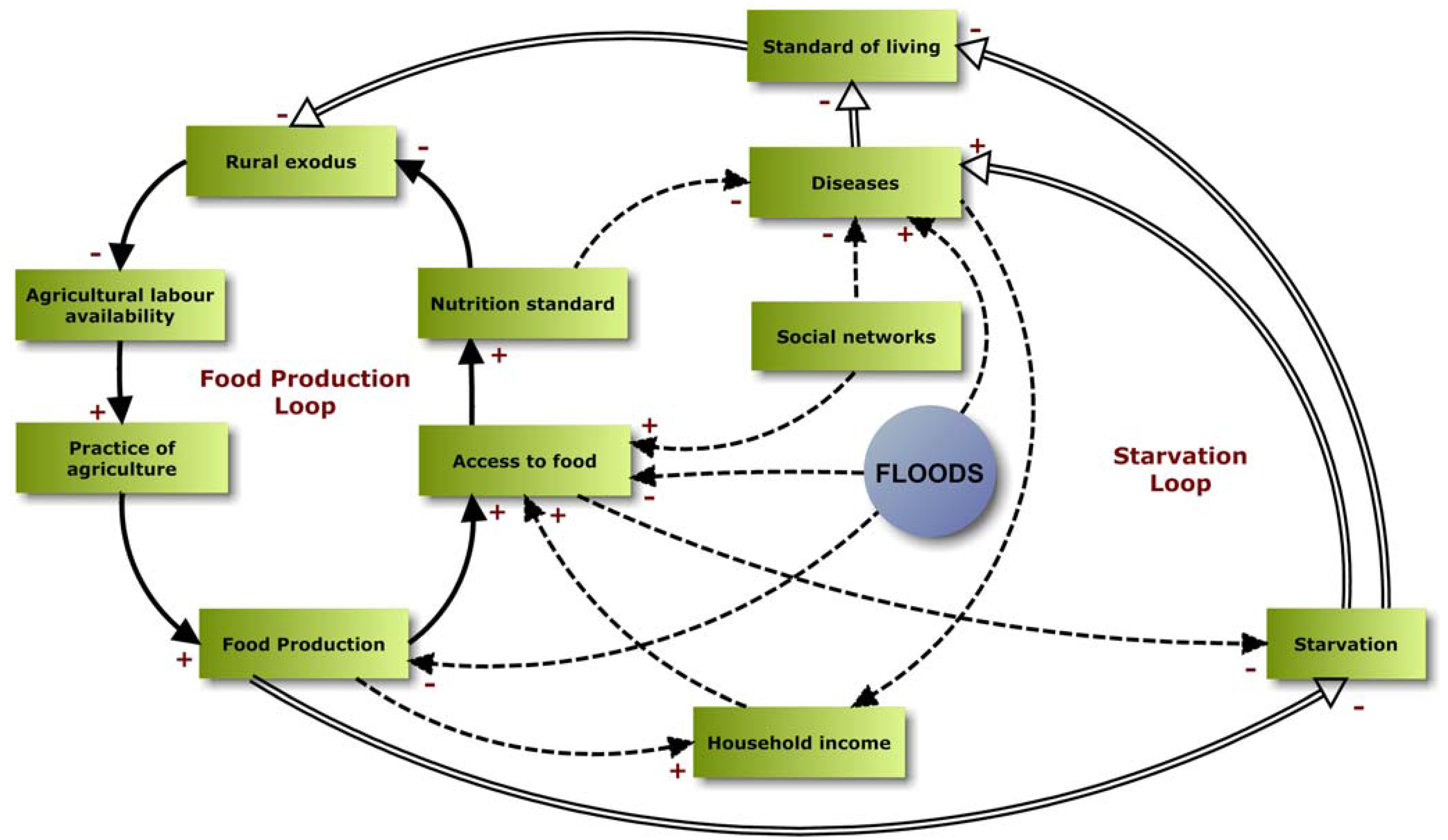

3.3.2. Flood induced starvation through the limitation of food production and reduced access to food

3.3.3. Floods and the desire to out-migrate

| Factor | Pre-flood (April-June 2007) | Post-flood (November 2007-November 2008 |

| Food production | 0.75 {high} | 0.30{low} |

| Household income | 0.50{average} | 0.25{low} |

| Agriculture labour | 0.78{high} | 0.35{low} |

| Rural exodus | 0.42{average} | 0.76{high} |

| Standard of living | 0.40{average} | 0.25{low} |

| Disease | 0.35{low} | 0.70{high} |

| Environmental quality | 0.76{high} | 0.35{low} |

| Nutrition standard | 0.68{average} | 0.28{low} |

| Non-agric income | 0.60{average} | 0.45{average} |

| Access to food | 0.77{high} | 0.35{low} |

| Seed stores | 0.78{high} | 0.20{low} |

| Social network | 0.65{average} | 0.55{average} |

3.4. Flood-induced Coping Strategies

| Responsibility | Goals | Immediate | Short-term | Long-term | Comments |

| Individualsand Households | Access to food and other emergency aid |  | During floods, the immediate concern is that of survival - people make efforts to access food , water and other aid that may be available | ||

| Rebuilding a base for subsistence food production |  | Immediately after the floods, residents (mainly farmers) first try to be able to feed themselves through subsistence food production | |||

| Income generation through agriculture |  | After being able to feed themselves, they begin looking for opportunity to sell surpluses | |||

| Non-agricultural income generation |  | Non-agricultural income generating activities come second place to food production in predominantly agricultural communities | |||

| Out-migration to zones of less risk & better opportunities |  | People eventually think of leaving the area in favour of zones with less risk and more economic and social opportunity | |||

| Rebuilding damaged houses |  | After living in temporary shelters for the duration of the floods, people struggle to rebuild what is left of their permanent homes immediately after the floods | |||

| Governmentand NGOs | Rebuilding public services |  | Immediately after floods, public services like water treatment, sewage disposal and others are up for repairs | ||

| Distribution of food aid |  | Food aid distribution is an immediate concern and task for governmental and non-governmental organization during floods | |||

| Coping with the disease burden |  | The disease burden (cholera, diarrhea, and other water-borne diseases) are all part of flood associated to which officials have to provide immediate | |||

| Education & sensitization |  | Education and sensitization on preparedness, mitigation, coping with floods is the long-term goal of government - aimed at reducing vulnerabilities to this disaster | |||

| Demarcating risk zones |  | Government through its town planning policies will demarcate risk zones where habitation is not allowed in a bid to reduce exposure of the populace to risk |

3.5. Social Support and Networks

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

- McCusker, B.; Carr, E.R. The co-production of livelihoods and land use change : Case studies from South Africa and Ghana. GeoForum 2006, 37, 790–804. [Google Scholar]

- Yaro, J.A. Theorizing Food Insecurity: building a livelihood framework for researching food insecurity. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2004, 58, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- UNOCHA. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Ghana Floods Flash Appeals 2007. http://www.reliefweb.int/fts (accessed on 30 December 2007).

- Hesselberg, J.; Yaro, J.A. An assessment of the extent and causes of food insecurity in Northern Ghana using a Livelihood Vulnerability Framework. GeoJournal 2006, 67, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar]

- Pelling, M.; High, C. Understanding Adaptation: What can Social Capital offer assessments of Adaptive Capacity? Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner, B.; Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I. At Risk: natural hazards,people’s vulnerability and disasters., 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 15–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F.; Allison, E.H. Livelihoods Approach and Management of small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2001, 25, 377–388. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana Living Standards Survey Report of the Fourth Round; Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, Ghana, 2005; pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2000 Population and Housing Census; Summary Report of Final Results, Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, Ghana, 2002; pp. 10–75. [Google Scholar]

- Awudu, A.; Wallace, H. Structural adjustment and economic efficiency of rice farmers in northern Ghana. Econ. Dev Cult. Herit. 2007, 48, 503–520. [Google Scholar]

- Grothmann, T.; Patt, A. Adaptive Capacity and Human Cognition: The process of individual adaptation to climate change. Glob. Environ. Change. 2005, 5, 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Osbahr, H.; Twyman, C.; Adger, N.W.; Thomas, D.S.G. Effective livelihood adaptation to climate change disturbance: Scale dimensions of practice in Mozambique. Geoforum 2008, 39, 1951–1964. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, A. Tracking Livelihood Change: Theoretical, Methodological and Empirical Perspectives from North-East Ghana. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2002, 28, 575–598. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.M.; Bertelsen, M.; Cisse, S.; Kodio, A. Conflict and agro-pastoral development. In Conflict, social captial and managing natural resources: a West African case study; Moore, K.M., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2005; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J.; Buck, L. Social capital and social learning in the process of natural resource management. In Natural Resources Management in African Agriculture; Barrett, C.B., Place, F., Aboud, A.A., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2002; pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Armah, F.A.; Yawson, D.O.; Yengoh, G.T.; Odoi, J.O.; Afrifa, E.K.A. Impact of Floods on Livelihoods and Vulnerability of Natural Resource Dependent Communities in Northern Ghana. Water 2010, 2, 120-139. https://doi.org/10.3390/w2020120

Armah FA, Yawson DO, Yengoh GT, Odoi JO, Afrifa EKA. Impact of Floods on Livelihoods and Vulnerability of Natural Resource Dependent Communities in Northern Ghana. Water. 2010; 2(2):120-139. https://doi.org/10.3390/w2020120

Chicago/Turabian StyleArmah, Frederick A., David O. Yawson, Genesis T. Yengoh, Justice O. Odoi, and Ernest K. A. Afrifa. 2010. "Impact of Floods on Livelihoods and Vulnerability of Natural Resource Dependent Communities in Northern Ghana" Water 2, no. 2: 120-139. https://doi.org/10.3390/w2020120

APA StyleArmah, F. A., Yawson, D. O., Yengoh, G. T., Odoi, J. O., & Afrifa, E. K. A. (2010). Impact of Floods on Livelihoods and Vulnerability of Natural Resource Dependent Communities in Northern Ghana. Water, 2(2), 120-139. https://doi.org/10.3390/w2020120