1. Introduction

Embankment erosion is a critical concern in hydraulic engineering, particularly in auxiliary spillways, where high water velocities and discharge rates can cause rapid and extensive surface damage, threatening the structural integrity of dams. With the escalating impacts of climate change and the increasing frequency of extreme flood events, rising reservoir water levels pose significant risks to dam safety, as demonstrated by the catastrophic failures of the Edenville and Sanford Dams in Michigan [

1]. These events underscore the urgent need for reliable and efficient methods to predict embankment erosion potential for earthen dam and spillway design and risk management.

Erosion prediction techniques are often time-consuming, costly, and limited in scalability, requiring extensive site-specific field and laboratory testing [

2,

3,

4,

5]. To address these limitations, Ghimire and Schulenberg [

6] developed the Windows Dam Analysis Modules (WinDAM) C screening model, which enables the identification of multiple at-risk spillways within a single simulation. Their study revealed that approximately 75 percent of the analyzed dams were at severe risk of erosion, primarily linked to narrower spillway widths. However, several other factors influence the embankment breach, such as embankment material, slope, dam height, and reservoir stage [

7]. Among the parameters previously examined, spillway width and stream power have emerged as the most dominant predictors of erosion [

8], surpassing other indicators such as the headcut erodibility index, representative soil diameter, and spillway channel slope ratio. Our goal in this paper is to evaluate whether these two parameters aid the prediction of spillway erosion using a machine learning framework.

Spillway width represents a geometric design parameter, whereas stream power is a hydraulic parameter that quantifies the energy per unit time and area exerted by flowing water on the spillway channel, a process closely tied to extreme flood dynamics. Stream power, expressed as the rate of energy dissipation, acts as a hydraulic stressor that initiates and accelerates erosion [

9]. Given their interdependence, variations in spillway width and stream power jointly influence overall spillway performance and erosion susceptibility. Yet, despite their importance, the combined predictive role of these parameters remains under-researched in the literature, and our paper fills this gap by using an existing dataset and employing various machine learning methods.

Methodologically, the application of machine learning in civil engineering and infrastructure has expanded rapidly in recent years [

10,

11,

12]. However, studies on dams and spillway performance, particularly auxiliary spillways, have primarily relied on traditional statistical methods, such as linear regression models, deterministic threshold-based criteria, and parametric reliability analyses, without emphasizing model-building and inherent non-linearities. This study contributes to the growing body of literature on machine learning techniques by employing and extending beyond a logistic regression framework, a widely used statistical approach for predicting dam erosion and other engineering events [

9,

13] to identify key parameters influencing spillway erosion. While earlier studies focused primarily on the physical mechanisms of spillway erosion and hydraulic loading [

9,

13], more recent work emphasizes that dam failures arise from interactions among technical, organizational, and human factors [

14].

In this context, the present study adopts a machine learning approach to model and predict the erosion potential of auxiliary spillways using the two most sensitive variables identified in prior research: spillway width and stream power. This is a more focused approach compared to prior studies that emphasize spillway erosion and embankment performance as a broad set of geotechnical, hydraulic, and operational factors, including soil type and material properties, degree of compaction, spillway geometry and slope, duration and intensity of overtopping events, and maintenance and operational history [

15,

16,

17]. While our study primarily targets auxiliary spillway erosion, the model applies broadly to earthen dams, embankments, and spillways. Accordingly, these terms are used interchangeably throughout the remainder of the paper.

To address the research question, we focus on a categorical variable with a binary outcome. Based on the sample of available dams and the information collected, a value of 1 is assigned to spillways with erosion and 0 to those without erosion (additional details are provided in the data description section). Accordingly, logistic regression is an appropriate statistical model for predicting the likelihood of occurrence between two mutually exclusive events, namely, whether erosion will occur, based on the given parameters. This methodological choice is consistent with existing literature on related applications. For example, a general linear model combined with a novel machine learning approach has been applied to model the gully erosion susceptibility of Golestan Dam in Iran using training and test samples [

18]. Similarly, piping erosion in the Zarandieh watershed of Markazi Province, Iran, has been evaluated using Bayesian generalized linear models with machine learning applications [

19].

Three supervised learning algorithms are applied to classify spillways as eroded or non-eroded cases: logistic regression, Support Vector Machine, and Random Forest. Model performance is evaluated using accuracy and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) metrics, and the best-fit model is further assessed through Bayesian probability analysis to quantify post-prediction reliability. By integrating data-driven algorithms with probabilistic reasoning, this study aims to improve the predictive accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability of erosion risk assessment under elevated stream power conditions, which serves as a proxy associated with extreme hydrologic events. The findings contribute to improved dam safety management by offering a scalable and evidence-based framework for spillway design and operation. As such, this paper advances spillway erosion prediction by demonstrating the application of machine learning and Bayesian probability within a decision science framework, offering a practical data-driven approach for assessing erosion potential when detailed site-specific information is limited, particularly under elevated hydraulic loading conditions. To the best of our knowledge, existing studies have not applied the specific machine learning framework adopted in this paper to evaluate whether readily available, pre-existing data on stream power and spillway width can be used to predict spillway erosion in the absence of detailed field observations.

2. Theoretical Framework

Existing studies have identified multiple factors contributing to dam and spillway erosion, including hydraulic forces, soil erodibility, and geometric design parameters. The logistic regression model has traditionally been employed to estimate the probability of spillway failure and to serve as a screening tool for erosion risk assessment [

9,

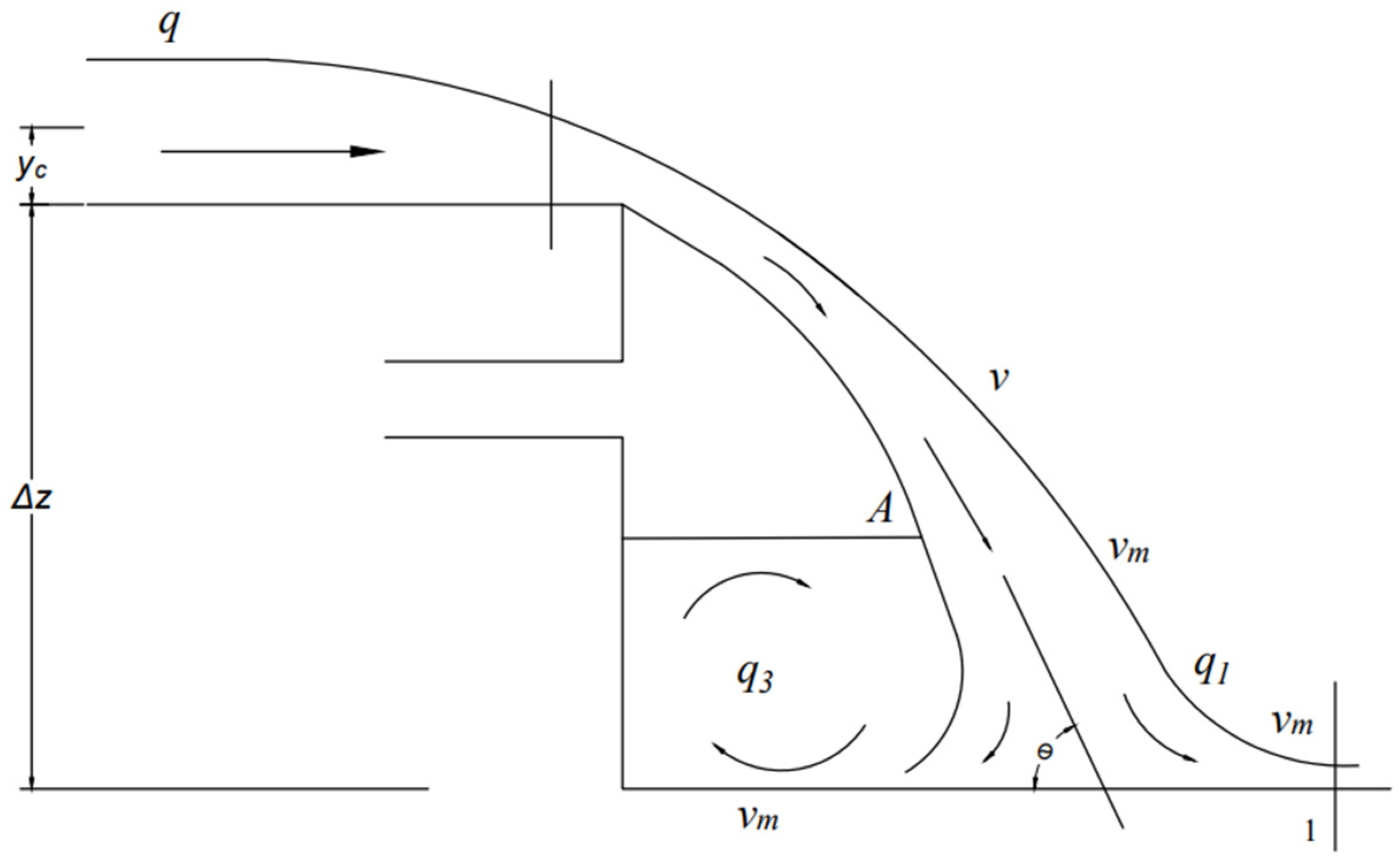

13]. In these studies, a threshold line was applied between stream power (y-axis) and one or more of the spillway features identified above, as illustrated in

Figure 1. This threshold line visually separates spillways with a higher likelihood of erosion (above the line) from those considered non-erodible (below the line).

The threshold line in this paper is defined using an approach similar to that of Wibowo et al. [

9]. In their study, the threshold is established based on stream power and an erodibility index (a measure of spillway “feature”), where a higher erodibility index indicates greater resistance to erosion. By analogy, in our model, a larger spillway width serves as the corresponding feature that provides greater resistance to erosion for a given level of stream power.

Two main approaches have been used in the literature to define this erosion threshold: the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) threshold line and Annandale’s threshold line [

20]. The USDA method, derived from empirical field observations, associates allowable stress limits with soil type and vegetative cover, providing a qualitative guideline for erosion potential [

21,

22]. In contrast, Annandale’s approach offers a more quantitative, physically based criterion, incorporating parameters such as stream power, erodibility index, and energy dissipation within a mathematical framework.

While both approaches are valuable for identifying critical thresholds, they rely on empirical or semi-analytical formulations that can be data-intensive and site-specific, limiting their generalizability. In the context of climate-induced extreme events, where hydrologic and hydraulic parameters can change rapidly, such static threshold methods may not fully capture nonlinear or interacting effects. This limitation motivates the adoption of a machine learning framework that can learn complex relationships between variables, such as spillway width and stream power, directly from data. Building on Annandale’s energy-based rationale, this study extends the theoretical framework toward a data-driven, machine-learning approach that can dynamically predict erosion potential and enhance dam safety assessment under extreme conditions.

2.1. Stream Power Based on Annandale’s Threshold Model

Stream power is the rate of energy dissipation per unit width of flow, which is calculated as:

where

P is the stream power per unit width,

γ is the unit weight of water (9.81 kN/m

3),

q is the unit discharge, which means the discharge per unit width, and is derived as

q =

Q/

b, and its unit is =

= m

2/s.

ΔE is the energy loss per unit weight of water, and is further calculated by using the following formula:

where,

Δz = dam height (m);

yc = critical flow depth (m), used here to represent energy conditions at control points in steep or transitional flow regions;

y1 = downstream flow depth/tailwater depth (m),

vm = flow velocity of jet downstream of a drop after entrainment of water (m/s);

g = acceleration due to gravity (m/s

2). Critical depth is used instead of normal depth because it better characterizes energy conditions at spillway chutes and hydraulic drop structures, where supercritical flow is expected. This modeling approach follows Annandale’s model [

20], who emphasized the use of critical depth in his formulation for evaluating erosion potential.

Figure 2 shows the discharge at the drop structure, along with the parameters explained.

2.2. Unit Discharge (q)

The amount of fluid passing a section of a stream in a unit of time is called unit discharge. Unit discharge in an open channel rectangular flow is computed as follows:

where,

2.3. Critical Flow Depth (yc)

As shown in

Figure 2,

yc denotes the critical flow depth, and it is calculated as:

where,

2.4. Flow Velocity of Jet in Downstream (vm)

Annandale provides the value of

vm as:

where,

vm = flow velocity of jet in the downstream in m/s

v = velocity of jet downstream of a drop just before entrainment of water, which is:

Overall, Equation (6) gives the velocity at a critical flow, and Equation (7) relates the slope geometry to the critical depth.

We use the above parameters to calculate stream power using Annandale’s approach. Other parameters included in

Figure 2,

(downstream unit discharge),

(trapped unit discharge due to recirculation), and A (point of velocity change) are not directly used in our analysis but are included in the figure for completeness, as originally presented in Annandale [

20].

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Description

To achieve the objective of this study, a comprehensive dataset was constructed by collecting information on dams that experienced erosion-related failures, as well as those that did not. The erosion information (our binary outcome variable, coded 1 for erosion cases and 0 for no erosion cases) was obtained from the Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) Dam Failures and Incidents Database. The remaining information needed for further analysis (spillway width, dam height, and maximum discharge) was obtained from the National Inventory of Dams (NID). Based on these measures, we calculated the following parameters: Unit discharge (

q) as shown in Equation (3); Critical depth (

yc) as shown in Equation (4); Flow velocity of jet in the downstream (

vm) as shown in Equation (5); Velocity of jet downstream of a drop just before entrainment of water (

v) as shown in Equation (6); and

cosθ as shown in Equation (7). All these parameters were used to calculate Energy Loss (

ΔE) as shown in Equation (2), and

ΔE was then substituted into Equation (1) to calculate Stream Power (

P) =

γ q ΔE.

Table 1 summarizes the key variables included in the analysis.

Although the NID enlists over 91,000 dams across the United States, it does not provide the spillway failure information. Therefore, the ASDSO database served as the source for a sample of dams that failed due to erosion-induced processes, such as spillway headcutting or surface degradation. As of May 2020, the ASDSO database documented approximately 1074 dam failure cases, from which a sample of 100 dams was selected, based on data availability. The selected cases specifically included failures attributed to spillway erosion, headcutting, spillway chute failure, or inadequate spillway capacity, aligning with the study’s emphasis on embankment erosion mechanisms. These erosion cases were intentionally chosen to represent a range of failure types associated with hydraulic stress during extreme flood events.

For comparison, a control sample of 400 dams was drawn to represent non-eroded spillways. While the selection was not randomized, efforts were made to include a diverse set of dams varying in size, type, and geographic distribution, thereby ensuring heterogeneity within the non-eroded group. The 1:4 ratio of eroded to non-eroded samples (100:400) was selected to balance statistical power with the relatively limited availability of well-documented erosion cases. The resulting dataset of 500 samples provided a balanced and representative basis for predictive modeling.

3.2. Supervised Machine Learning Models

To predict the likelihood of spillway erosion under extreme hydrologic conditions, this study applies supervised machine learning algorithms that classify samples as eroded or non-eroded based on physical and hydraulic characteristics. The 500 datasets were split into training (70%) and test (30%) subsets for model training, validation, and comparison. The training set was used to develop the predictive models, while the test set was used to evaluate each model’s generalization performance on unseen data.

Three machine learning algorithms were implemented: Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF). We implemented these models in R using the ‘caret’ package. Specifically, we used createDataPartition() for the train–test split. Model training and tuning were conducted using repeated k-fold cross-validation via trainControl (method = “repeatedcv”, number = 10, repeats = 5), and we enabled class probabilities (classProbs = TRUE) and saved cross-validated predictions (savePredictions = “final”). Following standard practice for binary classification, we optimized model performance using the area under the ROC curve (AUC) by specifying summaryFunction = twoClassSummary and metric = “ROC”. We estimated (i) a baseline logistic regression using train (…, method = “glm”, family = binomial), (ii) a random forest using train (…, method = “rf”, tuneLength = 5), and (iii) an SVM with radial kernel using train (…, method = “svmRadial”, preProcess = c (“center”, “scale”), tuneLength = 5), where SVM predictors were centered and scaled before model fitting.

3.2.1. Logistic Regression

The logistic regression model provides a probabilistic framework for classifying the binary outcome of erosion. It is particularly effective when the dependent variable is categorical, as in this study, where the outcome is either 1 (eroded) or 0 (non-eroded). The model estimates the probability

that a spillway will erode based on predictor variables—spillway width (

b) and stream power

—and is expressed as:

The linear form of logistic regression occurs in the natural log of odds of the event and is expressed as:

In the above expression,

b = spillway width and

P = stream power, with corresponding coefficients

,

and the regression intercept

. The left-hand side is the natural log of the odds, also known as logit. It is defined as the ratio of the probability of an occurrence

. An odds ratio represents the probability of a spillway being stable and is expressed as follows:

In this case, the probability of the event is calculated as:

where,

This framework allows for direct interpretation of the relationship between spillway width, stream power, and erosion probability, where negative coefficients indicate that an increase in width or a reduction in hydraulic energy reduces erosion risk.

3.2.2. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

The SVM algorithm constructs an optimal decision boundary (hyperplane) that separates eroded and non-eroded spillways in a multidimensional space defined by the predictor variables [

23]. Using a radial basis function (RBF) kernel, SVM captures nonlinear relationships between spillway width and stream power—relationships that often emerge during extreme flood events when flow conditions deviate from normal operating regimes. Model tuning was performed through repeated 10-fold cross-validation, optimizing the penalty parameter

and

to maximize classification accuracy and the area under the ROC curve (AUC).

3.2.3. Random Forest (RF)

The Random Forest model is a combination of tree predictors such that each tree depends on the values of a random vector sampled independently and with the same distribution for all trees in the forest [

24]. Each tree is trained on a random subset of data and predictor variables, and the final classification is determined by majority voting across trees. This nonparametric method is particularly advantageous for erosion modeling because it can capture complex, nonlinear, and interacting effects between spillway width and stream power without assuming a specific functional form. Variable importance was computed based on the Mean Decrease in Gini impurity, which quantifies each predictor’s contribution to reducing model uncertainty.

Following model training, predictions were generated for the 30% test sample to evaluate classification performance. Accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC were used as evaluation metrics. Among the three models, the Random Forest algorithm achieved the highest predictive accuracy (82.7%) and the most balanced performance across evaluation metrics. To further assess model reliability beyond standard classification metrics, a Bayesian probability analysis was applied to estimate the posterior probability of actual erosion given a predicted erosion outcome. This integrated approach enhances technical rigor and its applicability to dam safety decision-making under extreme hydrologic stress.

3.2.4. Bayesian Probability Method for Decision Making

The Bayesian probability method provides a probabilistic framework for evaluating the reliability of model predictions [

25]. Rooted in Bayes’ theorem, it allows the probability of an event to be updated based on new evidence—an approach particularly useful when assessing dam safety under uncertainty. In this study, Bayesian inference is used to estimate the probability that an embankment will actually experience erosion, given that the machine learning model predicts erosion. This post-prediction analysis complements the accuracy measures by incorporating prior and conditional probabilities to evaluate model reliability.

Mathematically, Bayes’ theorem is expressed as:

where,

represents the samples that actually eroded,

represents the event that the samples are predicted to erode,

is the prior probability of erosion in the dataset,

is the sensitivity, or the probability that the model predicts erosion given that erosion occurred, and

is the overall probability that the model predicts erosion.

This formulation provides a posterior probability , representing the chance that a spillway truly eroded, given its predicted classification. The Bayesian framework is particularly valuable for identifying false positives, cases where erosion is predicted but does not occur, and for quantifying the likelihood that these predictions correspond to actual erosion events. By integrating probabilistic reasoning with machine learning models, the study provides a more robust assessment of model reliability, prediction confidence, and the real-world risk of spillway erosion under extreme hydrologic events.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Model Comparison and Performance Evaluation

Three supervised machine learning algorithms—Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF)—were applied to classify spillways as eroded or non-eroded based on their geometric and hydraulic properties, that is, spillway width and stream power.

As shown in

Table 2, the Random Forest model demonstrates the strongest predictive performance among the evaluated approaches, achieving an accuracy of 82.7% and the most balanced classification outcomes, with a sensitivity of 92.5%, specificity of 43.3%, and an AUC of 0.82. The SVM model exhibits moderate discriminative ability (accuracy = 78.7%; AUC = 0.72), whereas the logistic regression model shows relatively low predictive power (accuracy = 75.3%; AUC = 0.54). The comparatively lower AUC values for logistic regression and SVM suggest limitations in capturing nonlinear and interaction effects between spillway width and stream power. In contrast, the Random Forest model more effectively represents these complex relationships, resulting in superior overall performance and justifying its use for subsequent analysis.

4.2. Random Forest Model Assessment Using Confusion Matrix

The confusion matrix for the Random Forest model on the test dataset is presented in

Table 3.

The model correctly classified 111 true non-eroded (

TN, non-eroded cases predicted as non-eroded) and 13 true eroded (

TP, eroded cases predicted as eroded) spillways, with 17 false negatives (

FN, eroded cases predicted as non-eroded) and 9 false positives (

FP, non-eroded cases predicted as eroded). We can use information from the confusion to calculate the following model performance measures:

While the model demonstrated a high ability to identify non-eroded cases, as reflected in its specificity of 0.925, its sensitivity of 0.433 indicates limited success in detecting eroded spillways. This imbalance in classification performance is consistent with the relatively small number of erosion cases in the dataset.

This outcome highlights a common challenge in dam safety prediction: predicting a non-eroded spillway as eroded (FP) affects operational efficiency, whereas predicting an eroded spillway as non-eroded (FN) poses substantial safety risks. Given the model’s high specificity (92.5%) and lower sensitivity (43.3%), accepting some false positives is a reasonable trade-off because it allows the model to be more cautious. In practical terms, this means the model may occasionally flag a spillway as eroded when it is not, but it is less likely to miss a truly eroded spillway. In dam safety management, this cautious approach is important because identifying a potential erosion problem early is far better than overlooking a dangerous condition.

4.3. Bayesian Probability Analysis

To further interpret the Random Forest model’s predictive performance, Bayesian inference was used to estimate the probability that an embankment will actually experience erosion given that the model predicts erosion. This provides a probabilistic interpretation of model reliability that goes beyond traditional classification accuracy. Although this same information can be calculated from the confusion matrix as precision (TP/(TP + FP)), we present it within a Bayesian probability framework, integrating traditional statistical reasoning with modern machine learning evaluation.

Using Bayes’ Theorem, we define: p(y) as the prior probability of erosion in the test sample (30 out of 150 samples = 0.20), p(1 − y) as the prior probability of no erosion (120 out of 150 samples = 0.80), p(|y) as the probability that the model predicts erosion when it has actually occurred (13 out of 30 = 0.43, representing sensitivity), and p(|1 − y) as the probability that the model incorrectly predicts erosion when erosion did not occur (9 out of 120 = 0.075, representing the false positives).

Using these values, the overall probability that the model predicts erosion is calculated as:

Substituting these values into Equation (13), we obtain:

Therefore, when the Random Forest model predicts erosion, there is approximately a 59 percent probability that the spillway will actually experience erosion. This posterior probability, derived from the 30% test sample, provides an out-of-sample measure of the model’s reliability and demonstrates how Bayesian analysis can complement machine learning classification metrics to better inform erosion risk assessments for dam professionals and practitioners.

4.4. Variable Importance and Physical Interpretation

To evaluate the relative contribution of the predictor variables, variable importance was assessed using the Mean Decrease in Gini index in the Random Forest model. As shown in

Figure 3, spillway width had a higher importance score (73.07) than stream power (38.38), indicating that geometric characteristics play a more dominant role in predicting spillway erosion than hydraulic intensity alone.

This finding aligns with hydraulic engineering theory, where narrower spillways tend to concentrate flow, increase velocity, and elevate shear stress on spillway surfaces, conditions that accelerate embankment erosion during extreme flood events. The Random Forest model thus confirms that spillway width is the most influential predictor of erosion risk, consistent with the physical mechanisms observed in previous studies [

8,

9].

4.5. Regression Validation and Direction of Effects

To further verify the direction and statistical significance of the predictors, we rely on the results from the logistic regression (although this is not the best model, we want to analyze the coefficients to evaluate the direction of the impact) based on log-transformed variables for width and stream power.

Table 4 shows a negative, statistically significant coefficient for spillway width (β = −0.459,

p < 0.001, controlling for stream power), indicating that erosion probability decreases with increasing spillway width. The coefficient for stream power (β = −0.06,

p = 0.06) is not statistically significant at the 5% significance level, suggesting a weaker relationship after controlling for width, consistent with the feature importance analysis presented above. Hence, we highlight the impact of the spillway width in the following sections.

Focusing on the coefficient for spillway width from the full model, the odds ratio for spillway width (e−0.459 = 0.63) implies that a 1-unit increase in the natural log of width, or approximately a 2.7-fold increase in physical width (since e1 = 2.718), reduces the odds of erosion by 37% (that is, 1 − 0.63 = 0.37), holding stream power constant. This result empirically supports the conclusion that narrower spillways are more susceptible to erosion because they constrain flow and amplify energy concentration during high-discharge events.

4.6. Decrease in Erosion Rates by Spillway Width

A descriptive analysis of observed erosion rates further validates the model results. When spillways were grouped into quartiles based on width, erosion rates decreased systematically from 30.4% in the smallest (narrowest spillway width) quartile to 6.4% in the largest (widest spillway width) quartile, as shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 4. This monotonic decline demonstrates a clear geometric control on erosion susceptibility and corroborates the negative relationship between spillway width and erosion probability derived from the machine learning models.

4.7. Discussion

In sum, the results demonstrate that machine learning methods, particularly the Random Forest algorithm, can effectively predict spillway erosion potential using minimal yet physically meaningful parameters: spillway width and stream power. Compared with traditional deterministic or threshold-based models [

20,

22], machine learning approaches offer improved flexibility in handling nonlinear relationships and complex variable interactions.

The integration of Bayesian inference further strengthens model interpretability by translating classification outcomes into conditional probabilities that convey real-world predictive confidence [

25]. From a dam safety perspective, the ability to quantify both prediction accuracy and posterior reliability is critical for early warning systems and for prioritizing maintenance resources under climate-driven extreme storm and flood scenarios.

While machine learning models provide accurate classification of erosion events, they primarily describe how well the model distinguishes eroded from non-eroded cases. In contrast, Bayesian probability analysis offers a complementary perspective by quantifying the posterior likelihood that a spillway truly erodes given its predicted classification. This probabilistic measure enhances interpretability, enabling engineers to evaluate the reliability of model predictions under real-world uncertainty. For instance, although the Random Forest model achieved 82.7% accuracy, Bayesian inference indicated a 59% posterior probability of actual erosion when erosion was predicted, offering a more nuanced assessment of prediction confidence for dam safety decision-making.

Ultimately, this study demonstrates that combining data-driven machine learning with probabilistic reasoning can enhance the predictive accuracy and operational relevance of erosion risk assessment, contributing to the broader goal of resilient dam and spillway design in an era of increasing hydrologic extremes.

4.8. Limitations and Future Work

Although this study focuses on hydraulic and geometric predictors, that is, spillway width and stream power, spillway erosion is fundamentally driven by the magnitude and duration of hydraulic events, and erosion may be continuous and progressive and not readily observable. Flood hydrology is, therefore, strongly influenced by rainfall intensity, storm duration, antecedent soil moisture, and catchment characteristics [

26,

27]. Likewise, rainfall–runoff processes directly control the hydrographs that produce erosive shear stresses on spillway surfaces [

14,

28]. Incorporating explicit flood and rainfall–runoff information could further enhance erosion prediction and improve linkage to climate-driven hydrologic processes.

A comprehensive erosion assessment, therefore, requires detailed, site-specific data from extensive field investigations, including information on soil type, compaction, spillway slope, duration of overtopping, maintenance history, etc. [

15,

16,

17]. Such data are not available for inclusion in our study, and collecting them is costly and time-consuming. For this reason, the present study focuses on erosion in earthen auxiliary spillways using stream power and spillway width, two variables consistently available across large datasets and found to be most influential among the erosion-related factors in previous studies, such as Ghimire et al. [

8].

In the absence of more comprehensive data, the screening approach developed in this paper is intended to support agency-level decision-making by identifying auxiliary spillways that may warrant further investigation. Once potentially high-risk spillways are flagged, agencies can then conduct detailed, site-specific hydraulic and geotechnical analyses. In this context, the contribution of this study lies in demonstrating how machine learning methods can be applied for large-scale screening and in providing a foundation for future research that incorporates additional variables and more detailed site information.

Additionally, the predictive performance of the machine learning models is inherently dependent on the size, diversity, and representativeness of the available erosion dataset. If the dataset is biased toward specific dam types, climatic conditions, or geographic regions, the models’ generalizability to other spillways under different conditions may be limited. Therefore, model selection and evaluation should be data-driven and context-specific, rather than assuming that the Random Forest model identified in this study will be the best-performing approach in all cases. Moreover, the black-box nature of Random Forest models limits direct physical interpretability of variable effects, reinforcing the need to use such models as complementary screening tools alongside physically based engineering analyses rather than as standalone decision instruments.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to evaluate the likelihood of earthen auxiliary spillway erosion during extreme events, such as floods, by examining the influence of spillway width and stream power through multiple machine learning techniques, including logistic regression, Random Forest, and Support Vector Machine (SVM). Among these models, the Random Forest algorithm achieved the best predictive performance, demonstrating superior accuracy and balanced classification. The Random Forest analysis identified both spillway width and stream power as significant predictors of erosion occurrence, with spillway width exerting a stronger influence. To further assess the model’s predictive reliability, a Bayesian analysis was conducted to estimate the likelihood that the predicted spillways would actually erode.

The Random Forest model achieved an overall accuracy of 82.7%, correctly classifying the majority of spillways in the test sample as either eroded or non-eroded. This performance measure alone, however, reflects an incomplete predictive power of the model. In particular, the model demonstrated strong capability in identifying non-eroded spillways, as evidenced by a high specificity of 92.5%, indicating that most stable spillways were correctly classified. By contrast, the sensitivity of 43.3% suggests more limited success in detecting eroded spillways, with a substantial proportion of erosion cases remaining undetected. This imbalance is largely attributable to the relatively small number of observed erosion events in the dataset, which constrains the model’s ability to learn distinctive erosion patterns. Bayesian inference further refined this analysis by indicating a 59% probability that a spillway predicted to erode would actually experience erosion, based on the model’s confusion matrix and conditional probability framework. Consequently, while the model is well-suited for screening and ruling out low-risk spillways, its performance in detecting erosion should be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, these results underscore the usefulness of combining machine learning algorithms with probabilistic reasoning, showing that the integration of physical parameters, specifically spillway width and stream power, with Bayesian post-prediction analysis can support erosion risk assessments. Overall, this research offers practical insights for dam designers and engineers by aiding agency-level decision-making by identifying auxiliary spillways that may require further evaluation, rather than relying on it as a standalone decision instrument. Once potentially high-risk spillways are identified, agencies can then undertake detailed, site-specific hydraulic and geotechnical analyses.