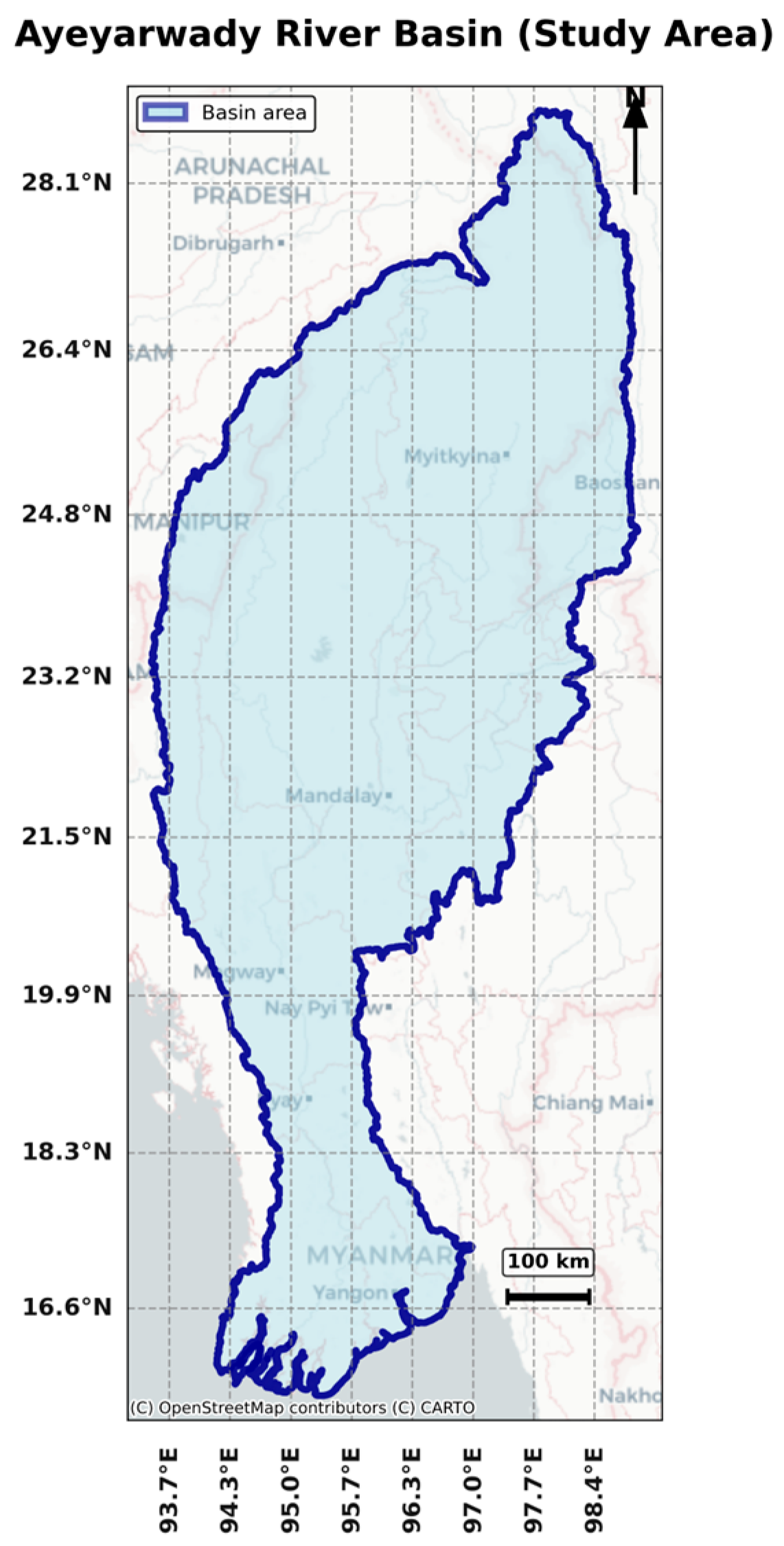

A Spatiotemporal Analysis of Heterogeneity and Non-Stationarity of Extreme Precipitation in the Ayeyarwady River Basin, Myanmar, and Their Linkages to Global Climate Variability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

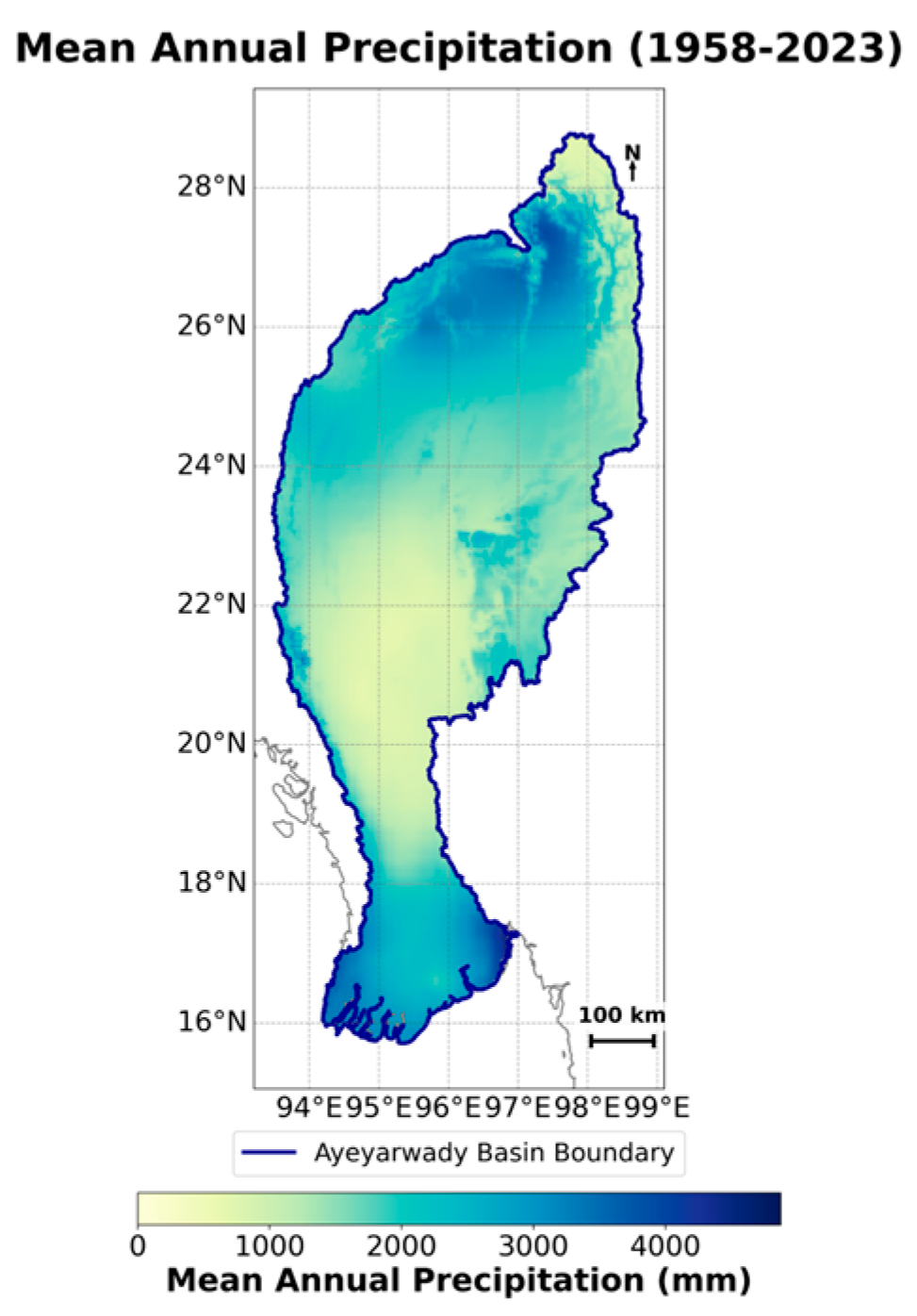

2.1. Precipitation Data: Source, Validation, and Preprocessing

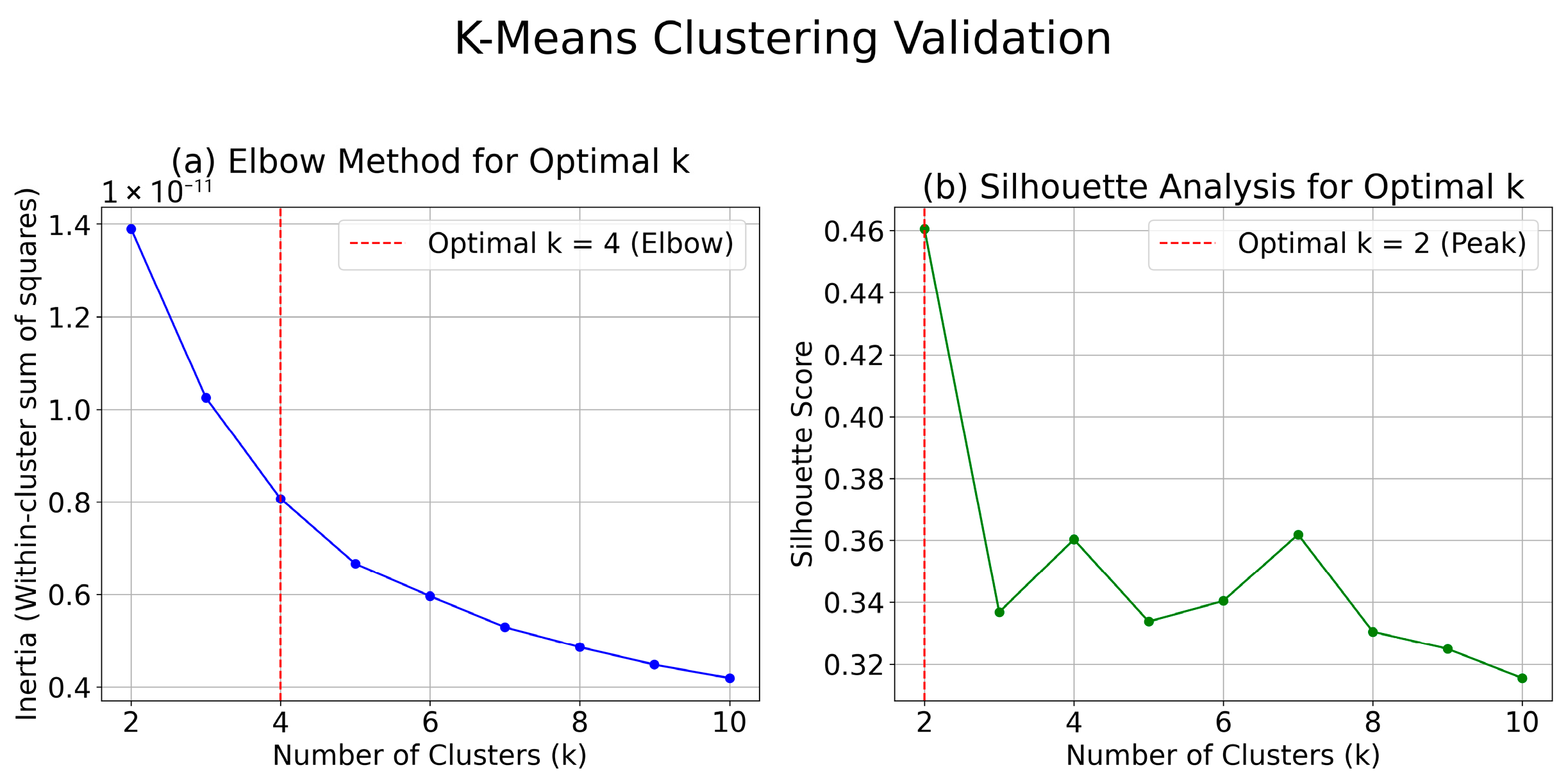

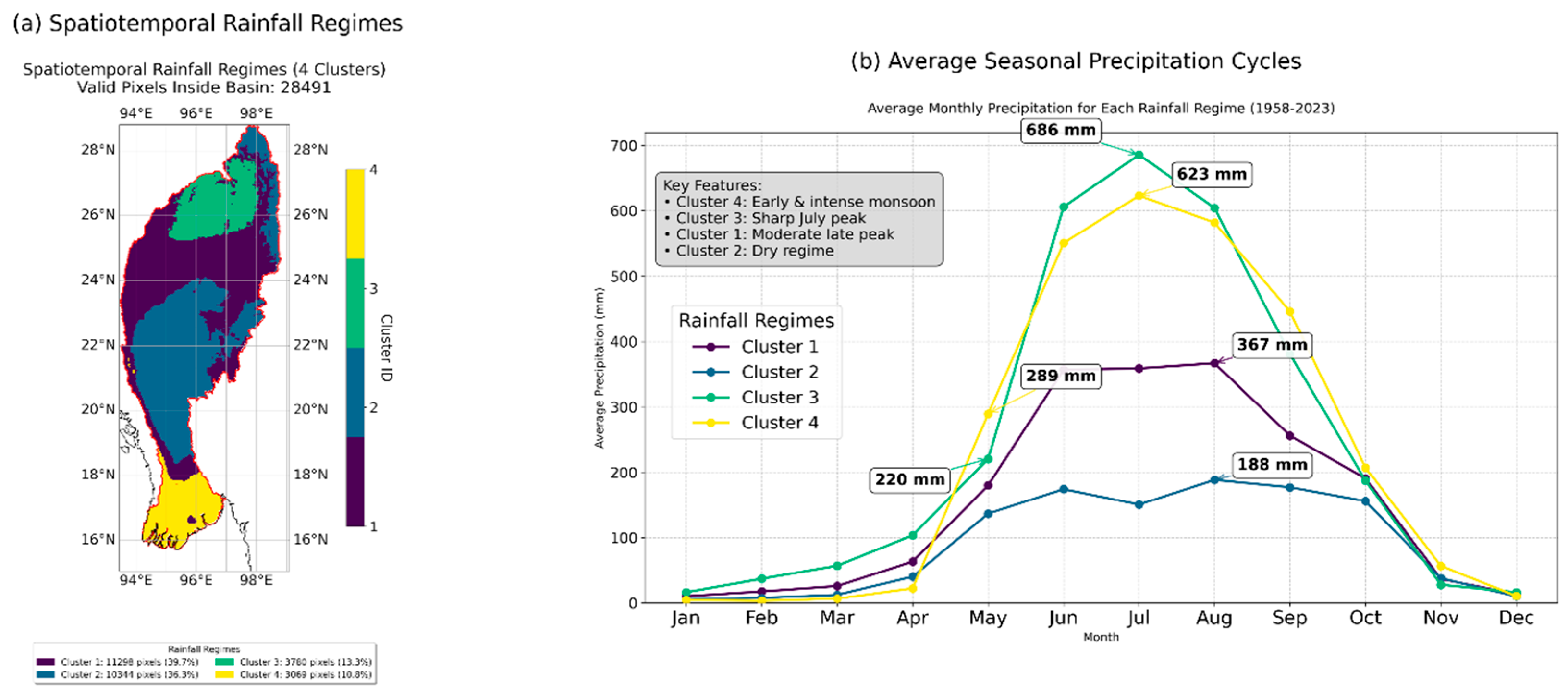

2.2. Delineation and Characterization of Distinct Spatiotemporal Rainfall Clusters (Objective 1)

2.3. Quantification of Non-Stationary Extreme Rainfall Events for Each Cluster (Objective 2)

2.4. Investigation of Teleconnections Between Regional Rainfall Extremes and Large-Scale Climate Oscillations (Objective 3)

3. Results

- Cluster 1 (Moderate-Late Peak):

- Cluster 2 (Dry-Subdued):

- Cluster 3 (Intense-Core Monsoon):

- Cluster 4 (Hyper-Intense-Early Peak):

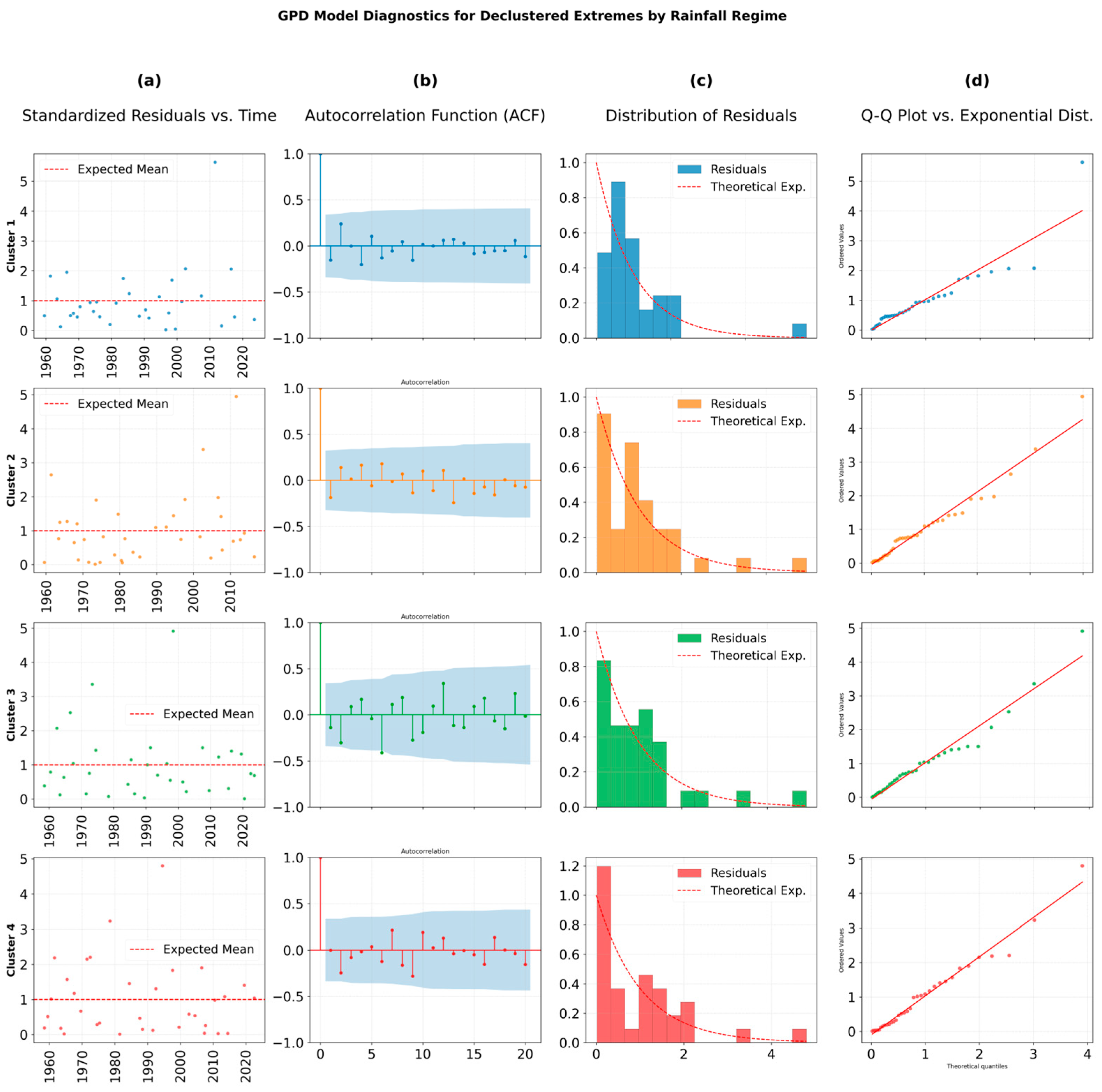

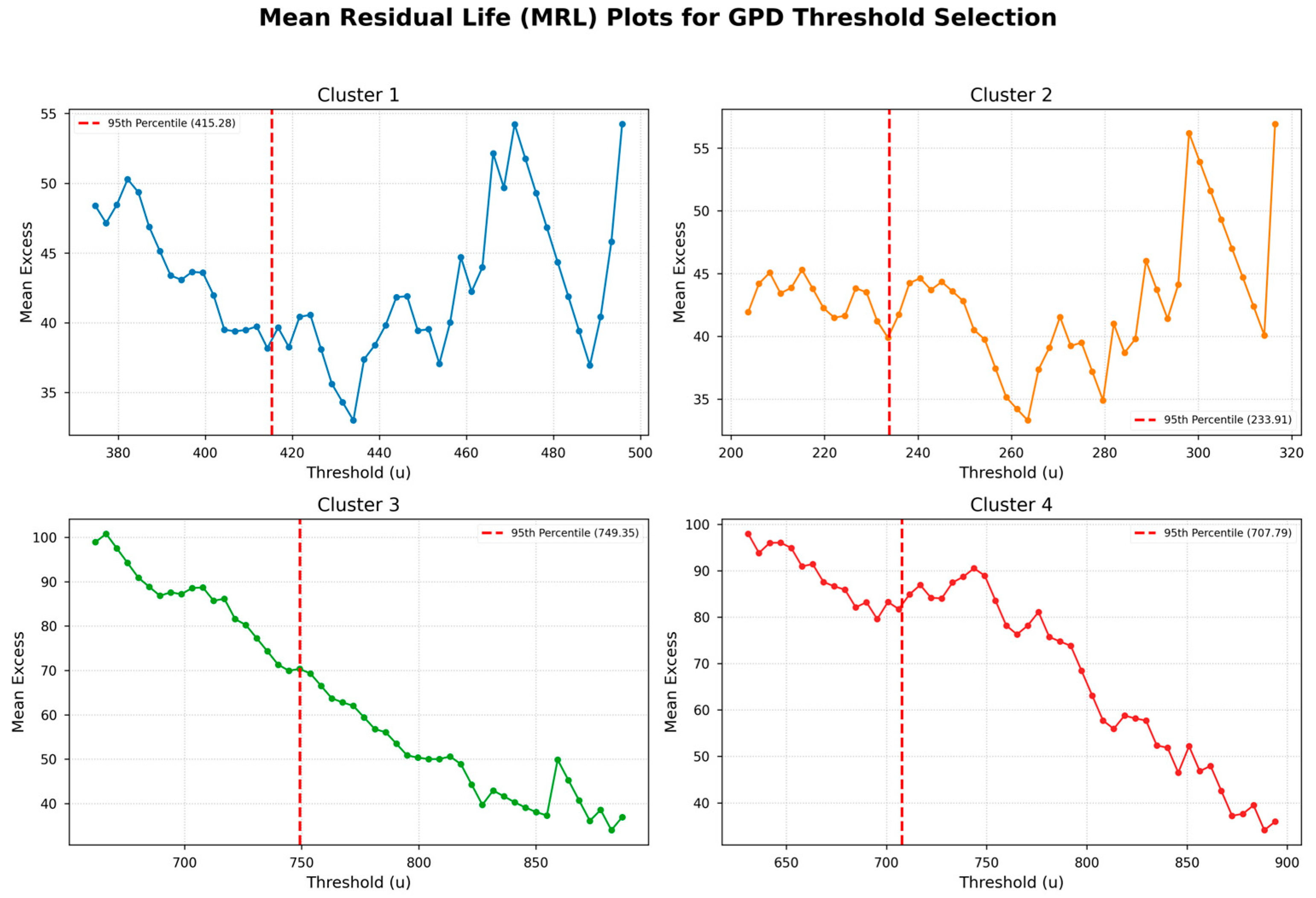

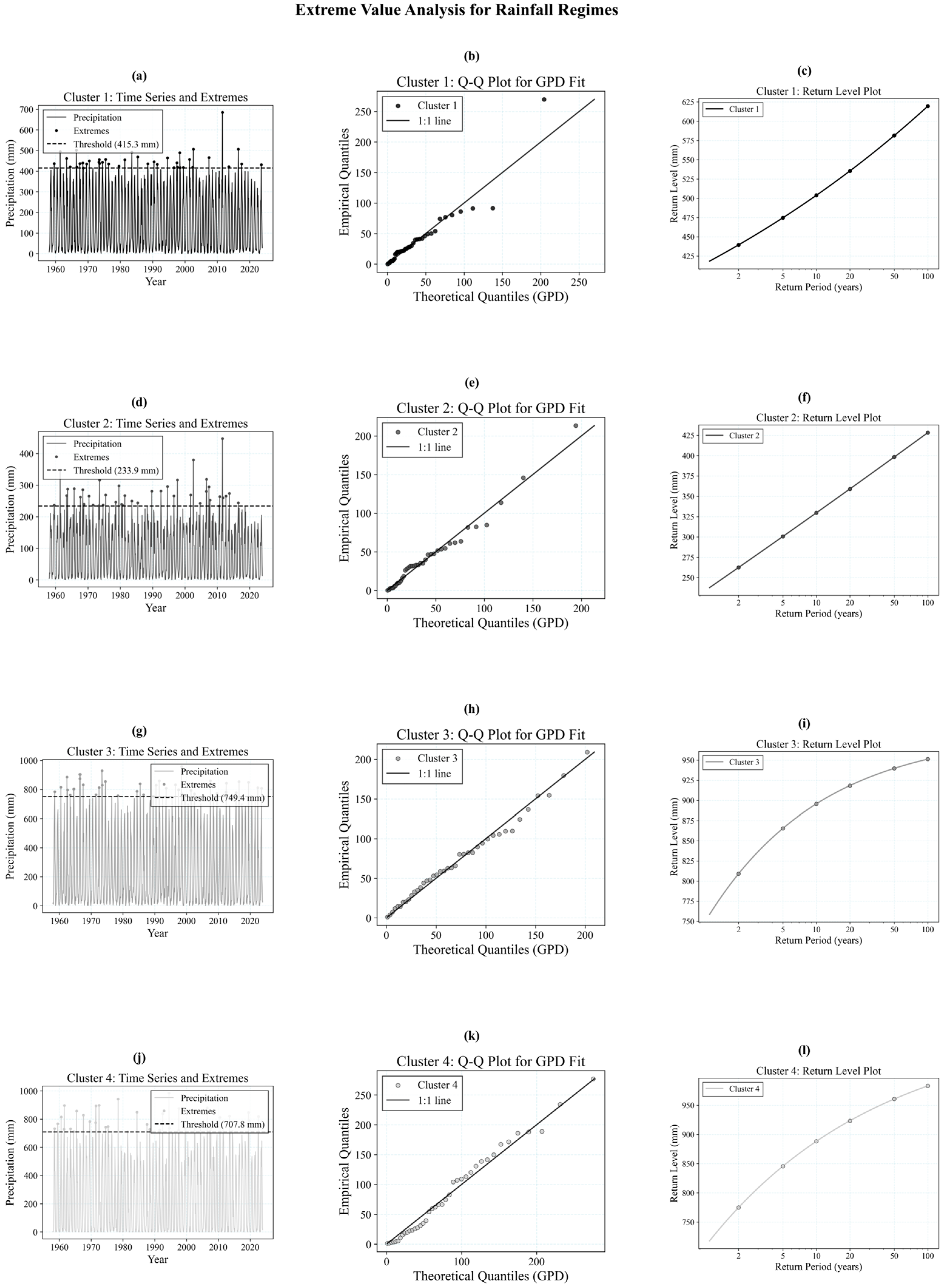

3.1. Extreme Value Analysis of Rainfall Clusters

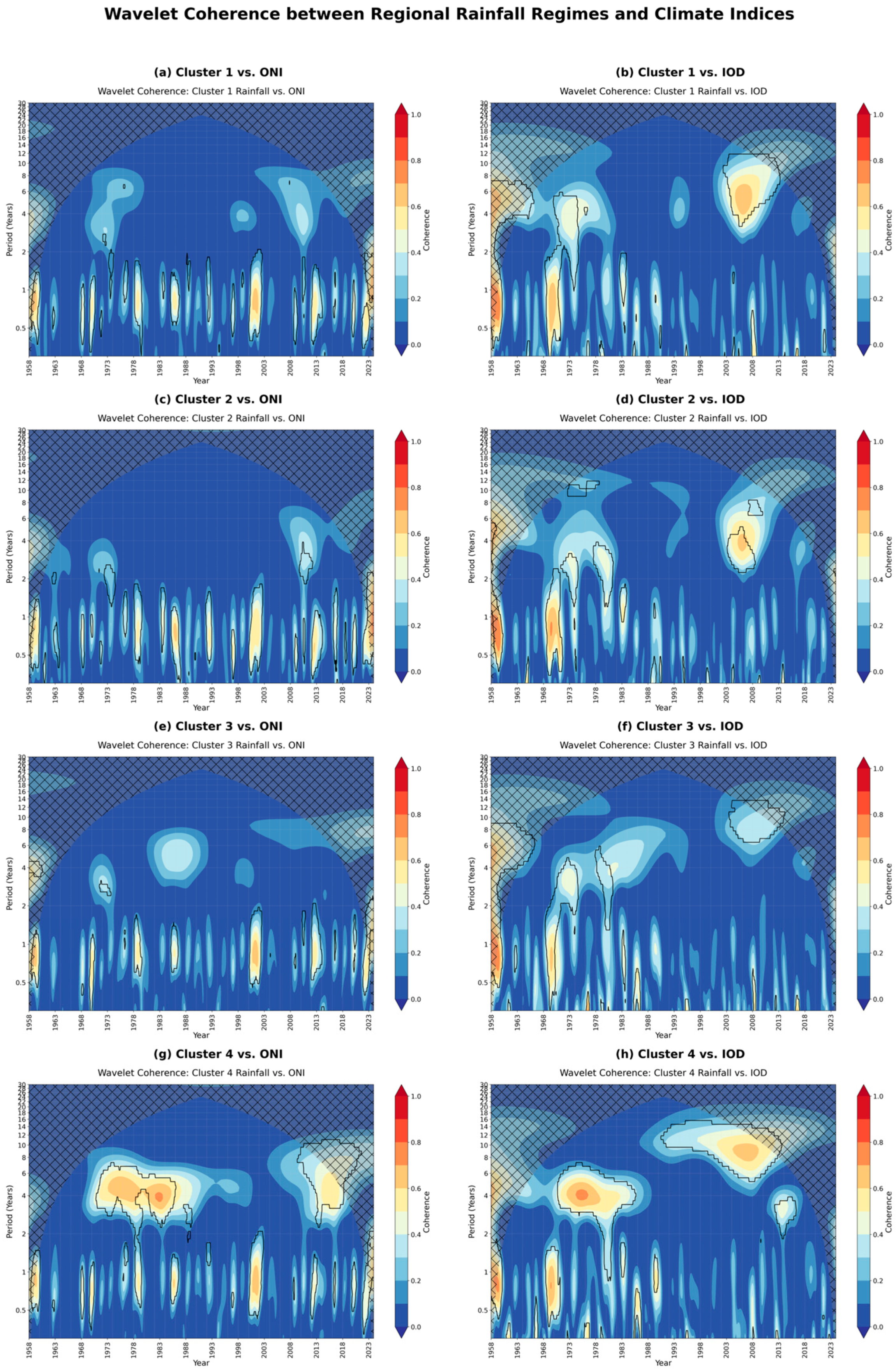

3.2. Characterization of Rainfall-Climate Teleconnections

3.3. Cluster-Specific Response Patterns

3.4. Temporal Evolution and Regime Stability

4. Discussion

Physical Mechanisms of Climate Teleconnections

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. Baseline Assessment Report: Introduction, Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Hydropower Sector in Myanmar; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Taft, L.; Evers, M. A review of current and possible future human–water dynamics in Myanmar’s river basins. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 4913–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yuan, X.; Guo, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, C.; Peng, L. Hydrological Response of the Irrawaddy River Under Climate Change Based on CV-LSTM Model. Water 2025, 17, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, U.; Babel, M.S.; Shrestha, S.; Srinivasan, G. A multi-temporal analysis of streamflow using multiple CMIP5 GCMs in the Upper Ayerawaddy Basin, Myanmar. Clim. Change 2019, 155, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, P.; Dhungana, S.; Kyaw, A.K.; Bharati, L. Hydrologic characterization of the Upper Ayeyarwaddy River Basin and the impact of climate change. J. Water Clim. Change 2022, 13, 2577–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisena, T.J.G.; Maskey, S.; Ranasinghe, R. Hydrological model calibration with streamflow and remote sensing based evapotranspiration data in a data poor basin. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, M.; Srivastav, R. Non-stationary modelling framework for regionalization of extreme precipitation using non-uniform lagged teleconnections over monsoon Asia. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 3577–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, F.; Zhi, X.; Babar, Z.A.; Tang, W.; Chen, P. Interannual variability of summer monsoon precipitation over the Indochina Peninsula in association with ENSO. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 128, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sein, Z.M.M.; Zhi, X. Interannual variability of summer monsoon rainfall over Myanmar. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaw, Z.; Fan, Z.X.; Bräuning, A.; Liu, W.; Gaire, N.P.; Than, K.Z.; Panthi, S. Monsoon precipitation variations in Myanmar since AD 1770: Linkage to tropical ocean-atmospheric circulations. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 56, 3337–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Le, D.; Matsumoto, J.; Ngo-Duc, T. Climatological onset date of summer monsoon in Vietnam. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-P.; Wang, Z.; McBride, J.; Liu, C.-H. Annual cycle of Southeast Asia—Maritime Continent rainfall and the asymmetric monsoon transition. J. Clim. 2005, 18, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mie Sein, Z.M.; Ullah, I.; Saleem, F.; Zhi, X.; Syed, S.; Azam, K. Interdecadal variability in Myanmar rainfall in the monsoon season (May–October) using eigen methods. Water 2021, 13, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sein, Z.M.M.; Ogwang, B.; Ongoma, V.; Ogou, F.K.; Batebana, K. Inter-annual variability of May-October rainfall over Myanmar in relation to IOD and ENSO. J. Environ. Agric. Sci. 2015, 4, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Aminoto, T.; Faqih, A.; Koesmaryono, Y.; Dasanto, B.D. Rainfall anomaly response to ENSO and IOD teleconnections in the CORDEX-SEA simulations. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; p. 012008. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/1359/1/012008/meta (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Mahmud, K.; Chen, C.-J. Space- and time-varying associations between Bangladesh’s seasonal rainfall and large-scale climate oscillations. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 145, 1347–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.R.; Tamagawa, I.; Harada, M. Spatiotemporal analysis on the teleconnection of ENSO and IOD to the stream flow regimes in Java, Indonesia. Water 2022, 14, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sein, K.K.; Chidthaisong, A.; Oo, K.L. Observed trends and changes in temperature and precipitation extreme indices over Myanmar. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafuerte, M.Q.; Matsumoto, J. Significant influences of global mean temperature and ENSO on extreme rainfall in Southeast Asia. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarrok, S.; Jang, C.J. Annual maximum precipitation in Indonesia and its association to climate teleconnection patterns: An extreme value analysis. SOLA 2022, 18, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.L.; Huang, Y.; Yong, S.; Lee, J.; Ali Najah Ahmed, A.-M.; Mirzaei, M. Analysing the variability of non-stationary extreme rainfall events amidst climate change in East Malaysia. AQUA-Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2024, 73, 1494–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, J.; Alexander, L.V.; Trewin, B.; Tse-Ring, K.; Sorany, L.; Vuniyayawa, V.; Keosavang, N.; Shimana, A.; Htay, M.M.; Karmacharya, J. Changes in temperature and precipitation extremes over the Indo-Pacific region from 1971 to 2005. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Wang, J.; Lv, S.; Bing, J. Spatial and temporal variability of seasonal precipitation in Poyang Lake basin and possible links with climate indices. Hydrol. Res. 2016, 47, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, H. Investigating the spatiotemporal variations of extreme rainfall and its potential driving factors with improved partial wavelet coherence. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 951468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 170191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyés, C.; Mohammed, M.A.; Szabó, N.P.; Szűcs, P. A hybrid approach to exploring the Spatiotemporal patterns of precipitation in sudan: Insights from neural network clustering and Fourier-wavelet transform analysis. Water Cycle 2025, 7, 151–163. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666445325000418 (accessed on 15 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sigauke, C.; Bere, A. Modelling non-stationary time series using a peaks over threshold distribution with time varying covariates and threshold: An application to peak electricity demand. Energy 2017, 119, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadgarai, S.; Kumar, V.; Pradhan, P.K. The connection between extreme precipitation variability over monsoon Asia and large-scale circulation patterns. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romatschke, U.; Houze, R.A., Jr. Characteristics of precipitating convective systems in the South Asian monsoon. J. Hydrometeorol. 2011, 12, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skliris, N.; Marsh, R.; Haigh, I.D.; Wood, M.; Hirschi, J.; Darby, S.; Phu Quynh, N.; Hung, N.N. Drivers of rainfall trends in and around Mainland Southeast Asia. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 926568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Eggeling, J.; Zhang, L.; He, H.; Sapkota, A.; Wang, Y.C.; Gao, C. Extreme precipitation patterns in the Asia–Pacific region and its correlation with El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Teo, F.Y.; Wong, S.Y.; Chan, A.; Weng, C.; Falconer, R.A. Monsoonal extreme rainfall in Southeast Asia: A review. Water 2024, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.M.; Bala, G.; Vemavarapu, S.V.; Boos, W.R. Opposite changes in monsoon precipitation and low pressure system frequency in response to orographic forcing. J. Clim. 2023, 36, 6309–6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, G.H. Orographic Precipitation. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2005, 33, 645–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houze, R.A. Orographic effects on precipitating clouds. Rev. Geophys. 2012, 50, 2011RG000365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shige, S.; Nakano, Y.; Yamamoto, M.K. Role of orography, diurnal cycle, and intraseasonal oscillation in summer monsoon rainfall over the Western Ghats and Myanmar Coast. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 9365–9381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxy, M.K.; Ritika, K.; Terray, P.; Murtugudde, R.; Ashok, K.; Goswami, B.N. Drying of Indian subcontinent by rapid Indian Ocean warming and a weakening land-sea thermal gradient. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.V.; Boos, W.R. A global climatology of monsoon low-pressure systems. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 141, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisena, T.; Maskey, S.; Ranasinghe, R.; Babel, M.S. Effects of different precipitation inputs on streamflow simulation in the Irrawaddy River Basin, Myanmar. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2018, 19, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, K.T.; Haishan, C.; Jonah, K. Climate Change Impact on the Trigger of Natural Disasters over South-Eastern Himalayas Foothill Region of Myanmar: Extreme Rainfall Analysis. Int. J. Geophys. 2023, 2023, 2186857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.K.; Rajagopalan, B.; Hoerling, M.; Bates, G.; Cane, M. Unraveling the Mystery of Indian Monsoon Failure During El Niño. Science 2006, 314, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, K.; Guan, Z.; Saji, N.H.; Yamagata, T. Individual and combined influences of ENSO and the Indian Ocean dipole on the Indian summer monsoon. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 3141–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, N.H.; Goswami, B.N.; Vinayachandran, P.N.; Yamagata, T. A Dipole Mode in the Tropical Indian Ocean. Nature 1999, 401, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wu, R.; Li, T. Atmosphere–Warm Ocean Interaction and Its Impacts on Asian–Australian Monsoon Variation. J. Clim. 2003, 16, 1195–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Statistics | Value (mm) |

|---|---|

| Monthly Precipitation—count | 792.00 (pixels) |

| Monthly Precipitation—mean | 80.80 |

| Monthly Precipitation—std | 76.94 |

| Monthly Precipitation—min | 0.03 |

| Monthly Precipitation—25% | 8.62 |

| Monthly Precipitation—50% | 47.27 |

| Monthly Precipitation—75% | 152.07 |

| Monthly Precipitation—max | 310.73 |

| Annual Precipitation—Mean | 969.63 |

| Annual Precipitation—Std Dev | 95.17 |

| Annual Precipitation—Wettest Year | 1973 (1171.43) |

| Annual Precipitation—Driest Year | 2014 (743.91) |

| Monthly Avg Precipitation—Wettest Month | August (188.72) |

| Monthly Avg Precipitation—Driest Month | January (4.51) |

| Cluster/Regime | Time Series Length | Threshold (mm) | Shape Parameter | Scale Parameter | 2 yr (mm) | 5 yr (mm) | 10 yr (mm) | 20 yr (mm) | 50 yr (mm) | 100 yr (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 792 | 415.282 | 0.1 | 41.892 | 445.35 | 488.43 | 523.75 | 561.6 | 615.84 | 660.31 |

| 2 | 792 | 233.91 | 0.1 | 45.696 | 266.71 | 313.70 | 352.23 | 393.52 | 452.68 | 501.18 |

| 3 | 792 | 749.354 | −0.421 | 99.339 | 809.07 | 865.46 | 895.77 | 918.41 | 939.78 | 951.27 |

| 4 | 792 | 707.791 | −0.279 | 106.316 | 774.79 | 845.60 | 888.34 | 923.55 | 960.77 | 983.23 |

| Cluster | Index | Mean Strength | Mean Period (Days) | Median Duration (Months) | Interval Count | Peak Decade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ONI | 0.501 | 10.5 | 50 | 6 | 2000 |

| IOD | 0.473 | 82.6 | 47 | 25 | 1970 | |

| 2 | ONI | 0.536 | 9.0 | 64 | 7 | 1960 |

| IOD | 0.472 | 68.3 | 25 | 25 | 2000 | |

| 3 | ONI | 0.428 | 42.0 | 22 | 14 | 1960 |

| IOD | 0.434 | 86.0 | 16 | 25 | 1970 | |

| 4 | ONI | 0.428 | 99.2 | 39 | 25 | 2010 |

| IOD | 0.479 | 124.6 | 74 | 23 | 1990 |

| Rainfall Regime | Climate Index | Time Interval Significance | Coherence Strength | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | ONI | 2000s (peak) | Moderate (0.501) | Fewest ONI intervals (6); Long median duration (50 months); Sub-annual coherence |

| IOD | 1970s (peak) | Moderate (0.473) | Most IOD intervals for Cluster 1 (25); Medium duration (47 months); Consistent sub-annual coherence | |

| Cluster 2 | ONI | 1960s (peak) | Strong (0.536) | Highest ONI strength among clusters; Long duration (64 months); Sub-annual coherence |

| IOD | 2000s (peak) | Moderate (0.472) | Balanced distribution; Shorter durations (25 months median); Sub-annual coherence | |

| Cluster 3 | ONI | 1960s (peak) | Weak (0.428) | Medium ONI count (14); Shorter durations (22 months); Weakest ONI strength |

| IOD | 1970s (peak) | Weak (0.434) | Shortest durations (16 months median); Consistent but weak coherence | |

| Cluster 4 | ONI | 2010s (peak) | Weak (0.428) | Most ONI intervals (25); Medium duration (39 months); Recent dominance |

| IOD | 1990s (peak) | Moderate (0.479) | Longest durations (74 months); Only cluster with > 1 yr periods; Strong IOD influence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nagai, M.; Bormudoi, A. A Spatiotemporal Analysis of Heterogeneity and Non-Stationarity of Extreme Precipitation in the Ayeyarwady River Basin, Myanmar, and Their Linkages to Global Climate Variability. Water 2026, 18, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020227

Nagai M, Bormudoi A. A Spatiotemporal Analysis of Heterogeneity and Non-Stationarity of Extreme Precipitation in the Ayeyarwady River Basin, Myanmar, and Their Linkages to Global Climate Variability. Water. 2026; 18(2):227. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020227

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagai, Masahiko, and Arnob Bormudoi. 2026. "A Spatiotemporal Analysis of Heterogeneity and Non-Stationarity of Extreme Precipitation in the Ayeyarwady River Basin, Myanmar, and Their Linkages to Global Climate Variability" Water 18, no. 2: 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020227

APA StyleNagai, M., & Bormudoi, A. (2026). A Spatiotemporal Analysis of Heterogeneity and Non-Stationarity of Extreme Precipitation in the Ayeyarwady River Basin, Myanmar, and Their Linkages to Global Climate Variability. Water, 18(2), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020227