Scale Experiments of a Shallow Channels Impact on Spillway Flow Distribution and Discharge Capacity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

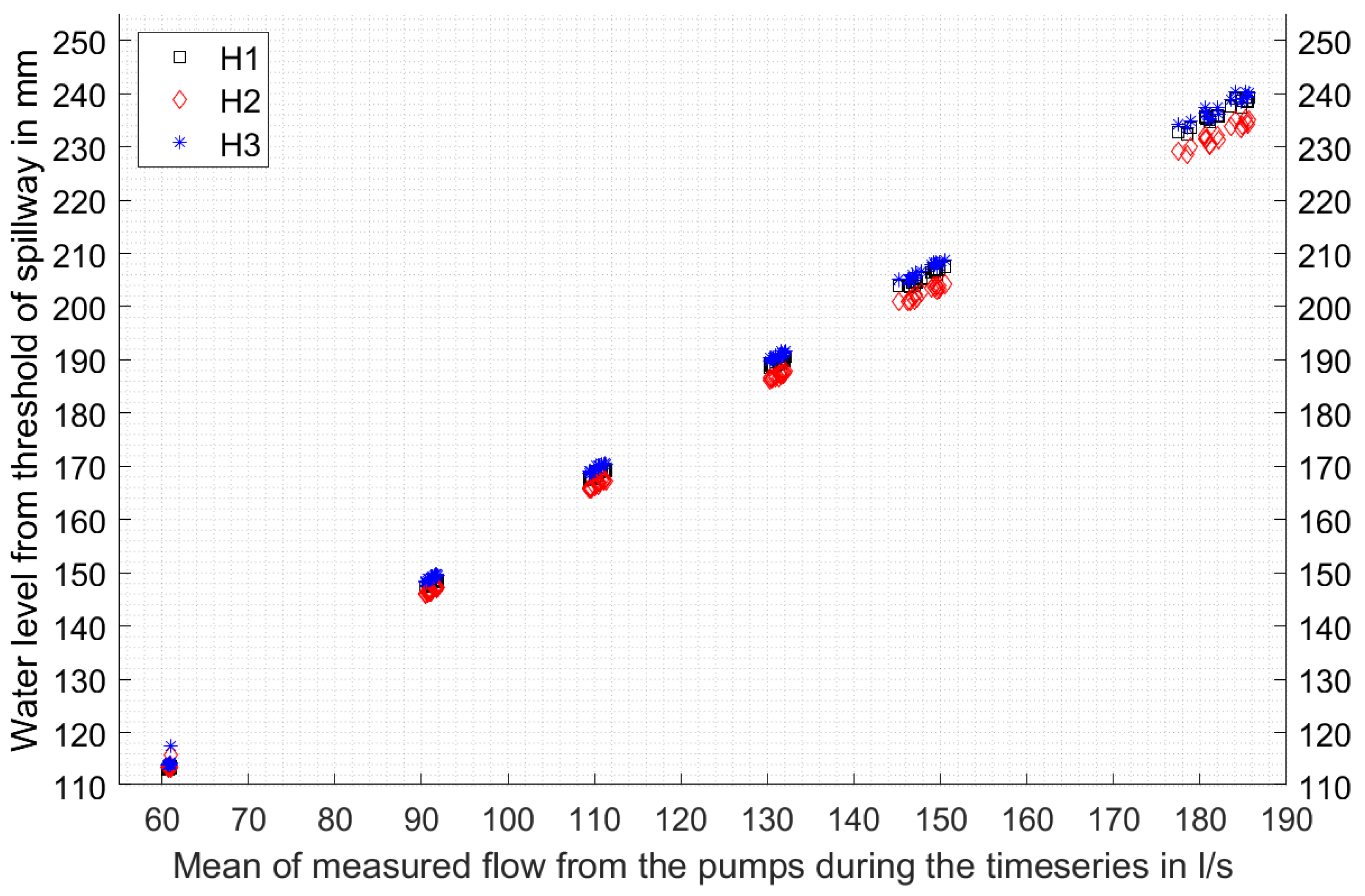

3.1. Discharge and Water Level Measurements

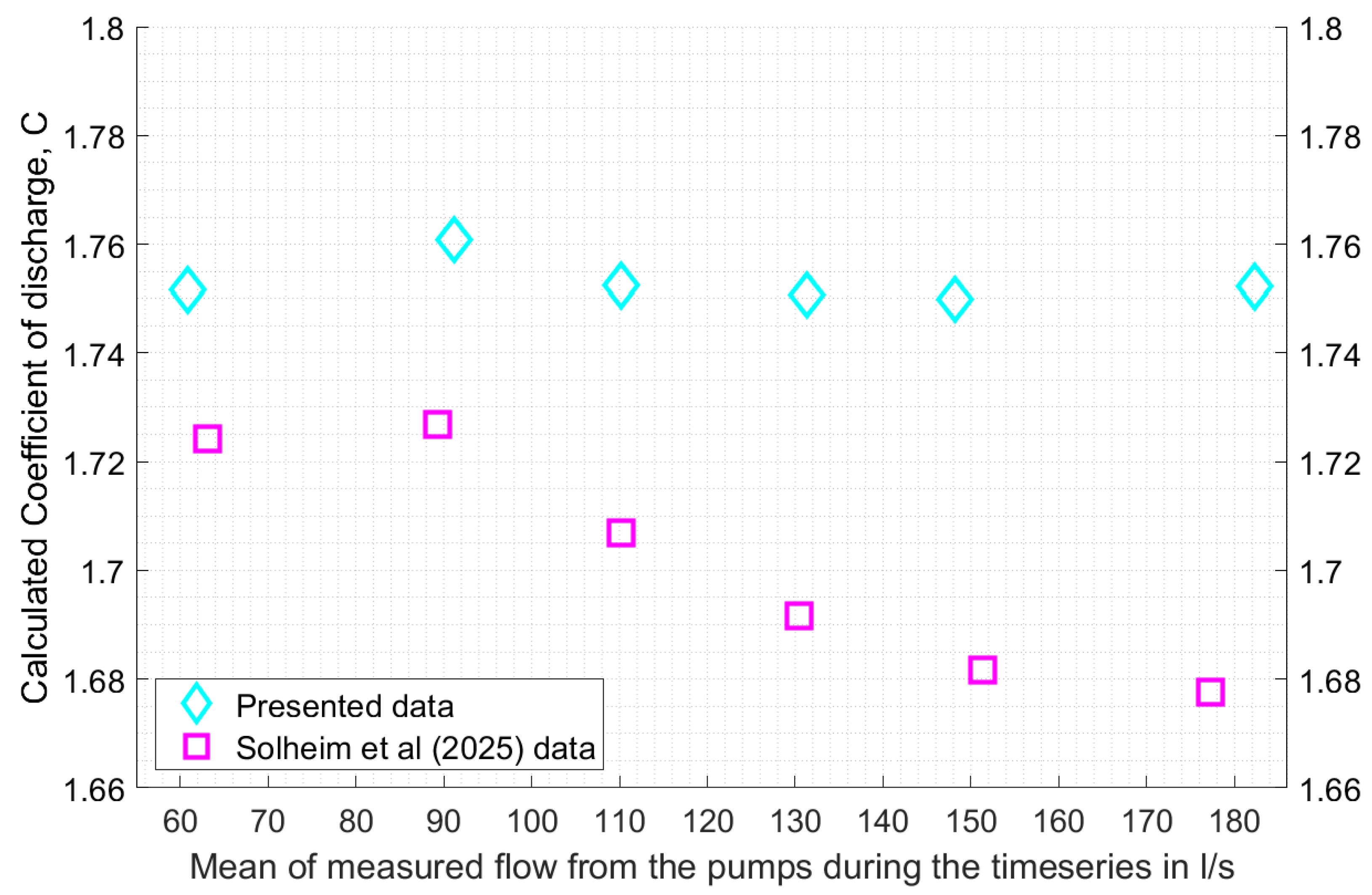

3.2. Calculated Coefficient of Discharge

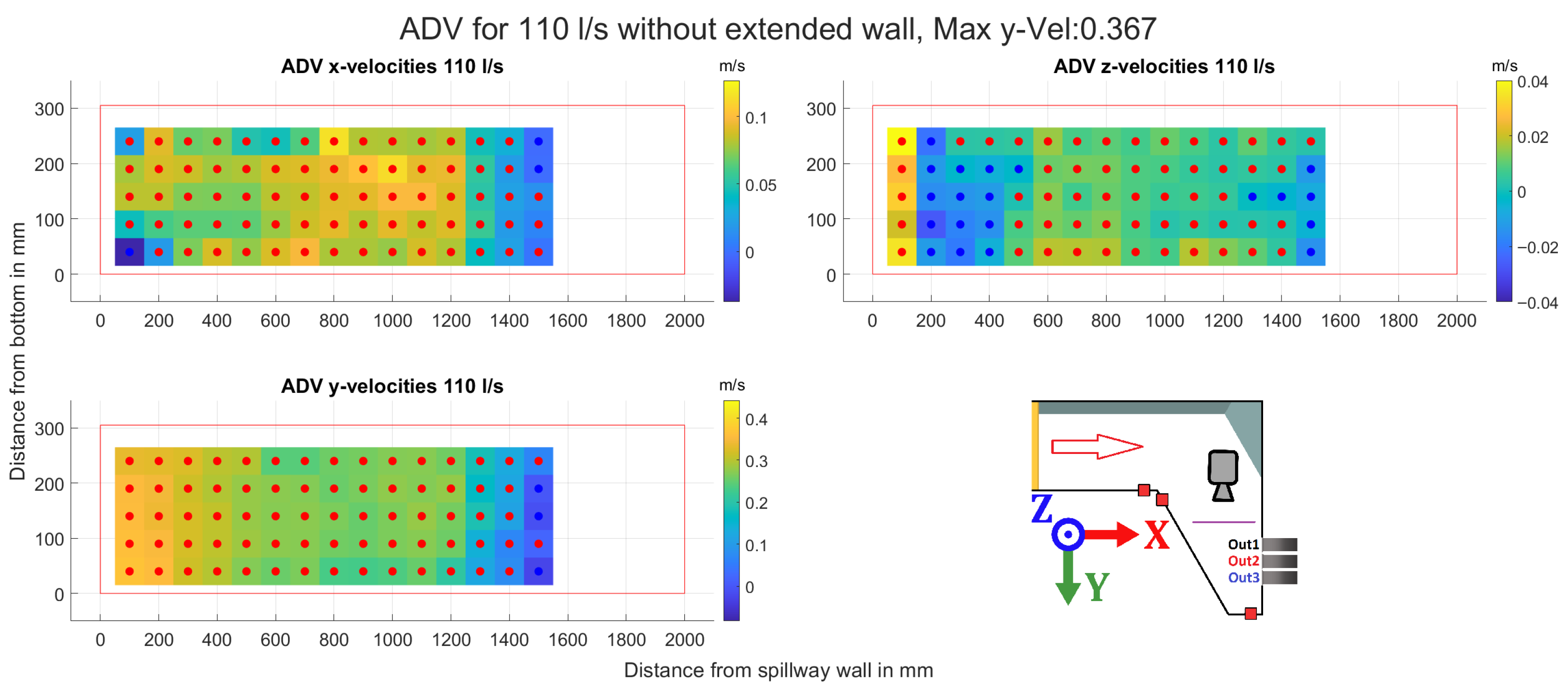

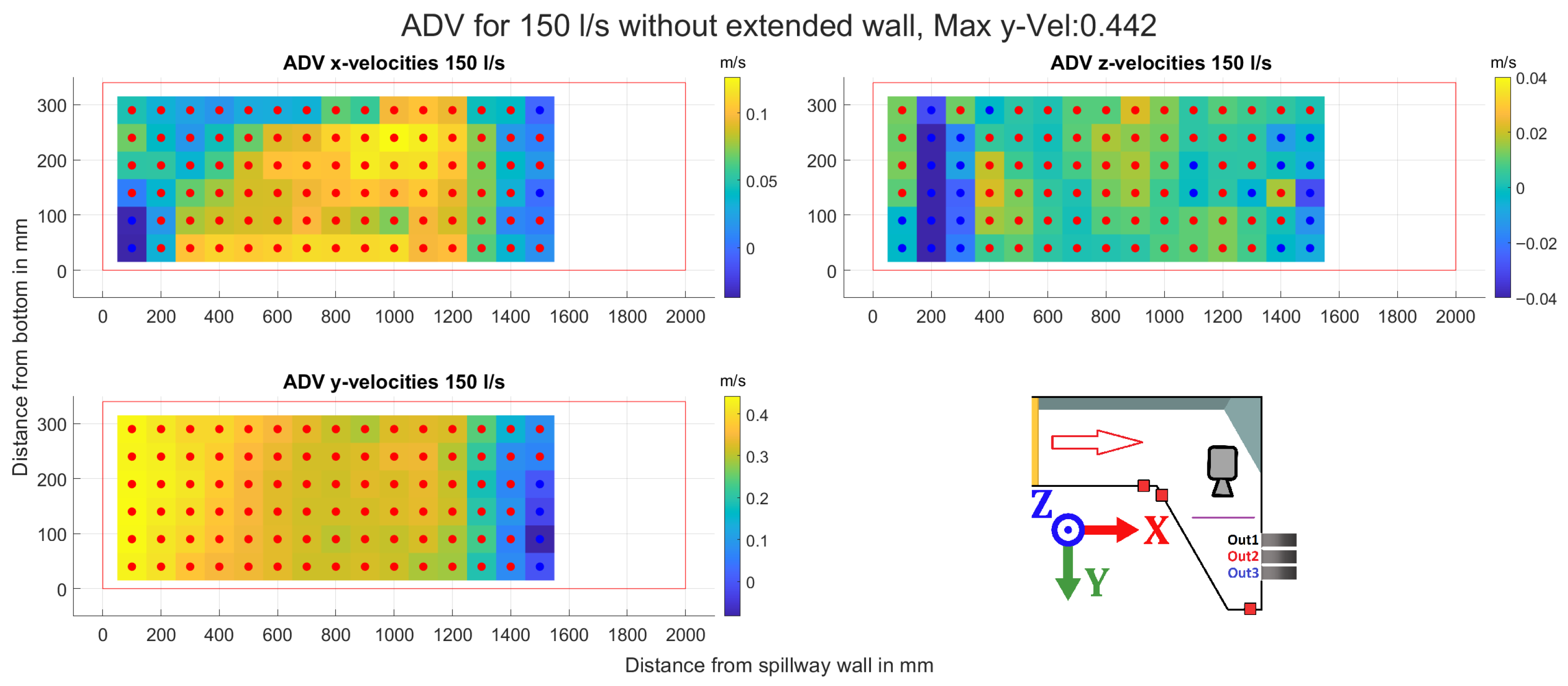

3.3. ADV Measurements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| ADV | Acoustic Doppler velocimetry |

| ICOLD | International Commission on Large Dams |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| CAD | Computer-assisted design |

References

- SwedCOLD. Book on Dams the Swedish Experience; SwedCOLD: Östersund, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Andreasson, P.; Teng, P.; Xie, Q. The Past and Present of Discharge Capacity Modeling for Spillways—A Swedish Perspective. Fluids 2019, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 1513–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.; Ahmadisharaf, E.; Villarini, G.; AghaKouchak, A. Historical changes in overtopping probability of dams in the United States. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cain, S.; Wosnik, M.; Miller, C.; Kocahan, H.; Wyckoff, R. Numerical Modeling of Probable Maximum Flood Flowing through a System of Spillways. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2011, 137, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, Y.; Dewals, B.; Archambeau, P.; Pirotton, M.; Erpicum, S. Pressure and velocity on an ogee spillway crest operating at high head ratio: Experimental measurements and validation. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2018, 19, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilmant, F.; Erpicum, S.; Peltier, Y.; Archambeau, P.; Dewals, B.; Pirotton, M. Flow at an Ogee Crest Axis for a Wide Range of Head Ratios: Theoretical Model. Water 2022, 14, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Orgaz, O.; Hager, W.H.; Guo, Y.; Erpicum, S.; Cantero-Chinchilla, F.N. Irrotational Flow over Ogee Spillway Crest: New Solution Method and Flow Geometry Analysis. Water 2024, 16, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Orgaz, O.; Hager, W.H. Comment on Stilmant et al. Flow at an Ogee Crest Axis for a Wide Range of Head Ratios: Theoretical Model. Water 2022, 14, 2337. Water 2024, 16, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, L.T.T.; Van Chien, N.; Xuan-Hien, L. Advanced hybrid techniques for predicting discharge coefficients in ogee-crested spillways: Integrating physical, numerical, and machine learning models. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 115002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaer, O.; Yarar, A. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Flow Over Ogee Spillway. Water Resour Manag. 2020, 34, 3949–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solheim, N.; Hedberg, M.; Lunde, N.H.; Pummer, E.; Lia, L. Modified Guide Walls for Incremental Increase of Spillway Capacity. In Proceedings of the 40th IAHR World Congress, Vienna, Austria, 21–25 August 2023; pp. 1978–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, B.M.; Johnson, M.C. Flow over Ogee Spillway: Physical and Numerical Model Case Study. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2001, 127, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.C.; Savage, B.M. Physical and Numerical Comparison of Flow over Ogee Spillway in the Presence of Tailwater. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2006, 132, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Mohammadian, A.; Nistor, I.; Imanian, H. Experimental and numerical study of the gated and ungated ogee spillway. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2024, 97, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.G.; Andreasson, P.; Staffan Lundström, T. CFD-Modelling and Validation of Free Surface Flow During Spilling of Reservoir in Down-Scale Model. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2013, 7, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Julien, P.Y.; Thornton, C.I. Interference of Dual Spillways Operations. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2019, 145, 04019014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, M.; Hellström, G.; Andersson, A.; Andreasson, P.; Andersson, R.; Angele, K. Numerical modelling for design of spillway refurbishing. In Proceedings of the 8th IAHR International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures ISHS2020, Santiago, Chile, 12–15 May 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, P.A.M.; Hellström, J.G.I.; Andersson, A.G.; Andreasson, P.; Andersson, R.L. Measurements and Simulations of the Flow Distribution in a Down-Scaled Multiple Outlet Spillway with Complex Channel. Water 2024, 16, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, S.; Farooq, U.; Helgesson, A. Energy Dissipation in Chute Spillway with Labyrinth Roughness Appurtenances. Water 2025, 17, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos-Villarroel, E.D.; Ojeda-Bustamante, W.; Díaz-Delgado, C.; Salinas-Tapia, H.; Bautista-Capetillo, C.F.; Flores-Velázquez, J.; Aguilar-Rodríguez, C.E. Influence of the Semicircular Cycle in a Labyrinth Weir on the Discharge Coefficient. Water 2025, 17, 3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, A.H.; Youssef, T.F.; Hamada, H.A.; M, I.M.; Samy, A. Optimizing Trapezoidal Labyrinth Weir Design for Enhanced Scour Mitigation in Straight Channels. Water 2024, 16, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megh Raj, K.C.; Crookston, B.; Flake, K.; Felder, S. Enhancing flow aeration on an embankment sloped stepped spillway using a labyrinth weir. J. Hydraul. Res. 2025, 63, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, J.P.; Sepúlveda, S.; Bombardelli, F.A.; Moreno-Casas, P.A.; Meireles, I.; Matos, J.; Blanc, A. Influence of Step Height on Turbulence Statistics in the Non-Aerated Skimming Flow in Steep-Stepped Spillways. Water 2025, 17, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleiss, A.J.; Erpicum, S.; Matos, J. Advances in Spillway Hydraulics: From Theory to Practice. Water 2023, 15, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, P.A.M.; Hellström, J.G.I.; Andersson, A.G. Shallow channel spillway flow distribution experiments. In Proceedings of the 9th IAHR International Junior Researcher and Engineer Workshop on Hydraulic Structures, Zurich, Switzerland, 20 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D.; Kang, S. Flume Experiments for Flow around Debris Accumulation at a Bridge. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Sharma, P.; Ahmad, Z.; Singh, U.; Karna, N. Three-dimensional velocity measurements around bridge piers in gravel bed. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2018, 36, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umesh K. Singh, Z.A.; Kumar, A. Turbulence characteristics of flow over the degraded cohesive bed of clay–silt–sand mixture. ISH J. Hydraul. Eng. 2017, 23, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Pandey, M.; Ahmad, Z. Flow field and sediment passing capacity of type-a piano key weirs. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2024, 39, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, G.; Kim, D.; Kim, K.; Roh, Y. Performance of a Rectangular-Shaped Surface Velocity Radar for River Velocity Measurements. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USBR. Design of Small Dams; Water resources technical publication; U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation: Washington, DC, USA, 1987.

- Solheim, N.; Hedberg, M.P.; Hellström, G.I.; Lia, L.; Andersson, A.G.; Andreasson, P.; Pummer, E. Discharge distribution in a multi-outlet spillway with varying adverse conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Phillips, M.; Crookston, B.; Diaz, Y. Comparison of Head-Discharge Relationships from an Arced High Head Submerged Labyrinth Weir, Prado Dam—A case study. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures, Zurich, Switzerland, 17–19 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inflow [l/s] | Out1 [l/s] | Ratio1 [%] | Out2 [l/s] | Ratio2 [%] | Out3 [l/s] | Ratio3 [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61.02 | 20.17 | 33.05 | 20.29 | 33.25 | 20.28 | 33.24 |

| 60.97 | 20.22 | 33.12 | 20.18 | 33.10 | 20.26 | 33.26 |

| 60.96 | 20.37 | 33.42 | 20.32 | 33.31 | 20.35 | 33.38 |

| 60.81 | 20.38 | 33.45 | 20.31 | 33.44 | 20.34 | 33.46 |

| 60.89 | 20.29 | 33.28 | 20.20 | 33.22 | 20.33 | 33.38 |

| 91.67 | 30.30 | 33.07 | 30.18 | 33.12 | 30.64 | 33.35 |

| 91.43 | 30.63 | 33.43 | 30.53 | 33.29 | 30.63 | 33.37 |

| 91.70 | 30.37 | 33.09 | 30.44 | 33.26 | 30.48 | 33.33 |

| 90.82 | 30.19 | 33.14 | 30.35 | 33.43 | 30.30 | 33.34 |

| 90.94 | 29.95 | 33.10 | 30.28 | 33.30 | 30.37 | 33.48 |

| 90.70 | 30.06 | 33.07 | 30.36 | 33.33 | 30.29 | 33.47 |

| 109.54 | 36.25 | 33.08 | 36.72 | 33.26 | 36.54 | 33.39 |

| 109.98 | 36.37 | 33.21 | 36.58 | 33.25 | 36.24 | 33.15 |

| 109.45 | 36.38 | 33.20 | 36.77 | 33.56 | 36.62 | 33.41 |

| 110.39 | 36.66 | 33.16 | 37.07 | 33.31 | 36.97 | 33.48 |

| 111.13 | 36.54 | 33.09 | 37.10 | 33.35 | 37.03 | 33.34 |

| 110.87 | 36.64 | 33.25 | 36.91 | 33.28 | 37.05 | 33.34 |

| 130.82 | 42.99 | 32.99 | 43.60 | 33.15 | 43.61 | 33.46 |

| 131.08 | 43.37 | 32.95 | 43.63 | 33.24 | 44.08 | 33.43 |

| 131.02 | 43.04 | 32.97 | 43.55 | 33.37 | 43.71 | 33.39 |

| 131.06 | 43.37 | 32.95 | 43.99 | 33.42 | 44.31 | 33.53 |

| 131.68 | 43.24 | 33.02 | 44.08 | 33.39 | 44.10 | 33.47 |

| 131.95 | 43.10 | 33.00 | 43.83 | 33.34 | 44.13 | 33.43 |

| 147.16 | 48.42 | 32.90 | 49.37 | 33.41 | 49.16 | 33.56 |

| 146.58 | 48.38 | 32.90 | 49.02 | 33.40 | 48.90 | 33.45 |

| 146.36 | 48.41 | 32.87 | 48.47 | 33.37 | 49.13 | 33.56 |

| 149.79 | 49.39 | 32.95 | 49.83 | 33.31 | 50.23 | 33.63 |

| 149.66 | 49.39 | 32.81 | 50.18 | 33.48 | 50.22 | 33.64 |

| 149.34 | 49.13 | 32.97 | 49.97 | 33.41 | 50.27 | 33.64 |

| 182.53 | 59.63 | 32.74 | 60.36 | 33.42 | 61.25 | 33.81 |

| 179.00 | 60.66 | 32.82 | 59.85 | 33.44 | 61.06 | 33.72 |

| 180.23 | 59.30 | 32.81 | 59.43 | 33.49 | 60.30 | 33.78 |

| 182.48 | 60.96 | 32.96 | 62.15 | 33.52 | 62.23 | 33.89 |

| 185.06 | 59.88 | 33.16 | 62.24 | 33.52 | 63.10 | 34.02 |

| 184.78 | 59.92 | 32.92 | 61.83 | 33.58 | 63.07 | 34.04 |

| Inflow [l/s] | H1 [mm] | H2 [mm] | H3 [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60.93 | 113.35 | 113.61 | 114.24 |

| 91.25 | 148.05 | 146.72 | 149.08 |

| 109.96 | 168.46 | 166.58 | 169.67 |

| 130.94 | 189.46 | 187.03 | 190.75 |

| 148.47 | 205.58 | 203.60 | 206.84 |

| 182.50 | 236.41 | 232.35 | 237.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hedberg, P.A.M.; Hellström, J.G.I.; Andersson, A.G.; Andreasson, P. Scale Experiments of a Shallow Channels Impact on Spillway Flow Distribution and Discharge Capacity. Water 2026, 18, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020177

Hedberg PAM, Hellström JGI, Andersson AG, Andreasson P. Scale Experiments of a Shallow Channels Impact on Spillway Flow Distribution and Discharge Capacity. Water. 2026; 18(2):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020177

Chicago/Turabian StyleHedberg, P. A. Mikael, J. Gunnar I. Hellström, Anders G. Andersson, and Patrik Andreasson. 2026. "Scale Experiments of a Shallow Channels Impact on Spillway Flow Distribution and Discharge Capacity" Water 18, no. 2: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020177

APA StyleHedberg, P. A. M., Hellström, J. G. I., Andersson, A. G., & Andreasson, P. (2026). Scale Experiments of a Shallow Channels Impact on Spillway Flow Distribution and Discharge Capacity. Water, 18(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020177