Wind–Wave and Swell Separation and Typhoon Wave Responses on the Dafeng Shelf (Northern Jiangsu)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

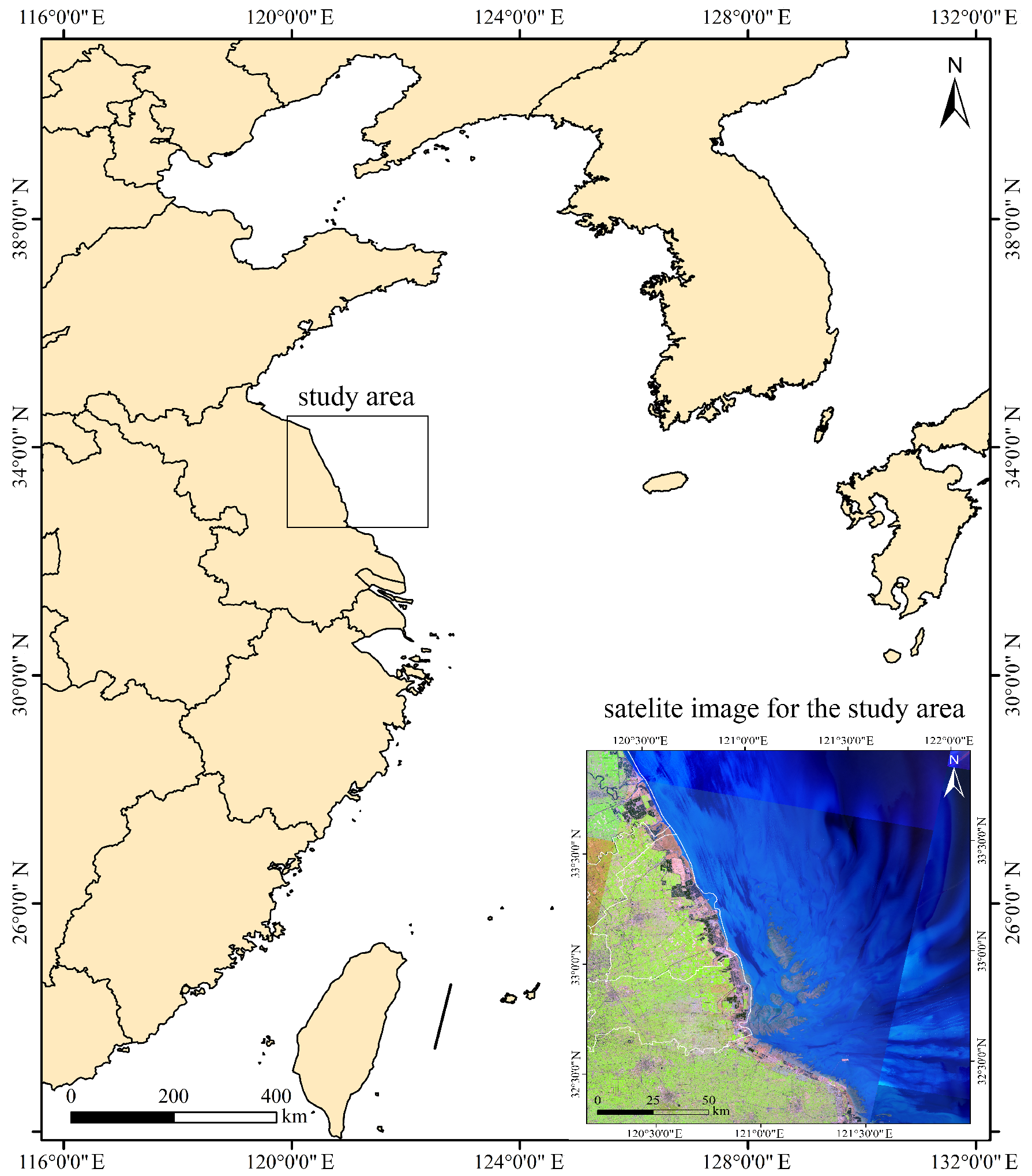

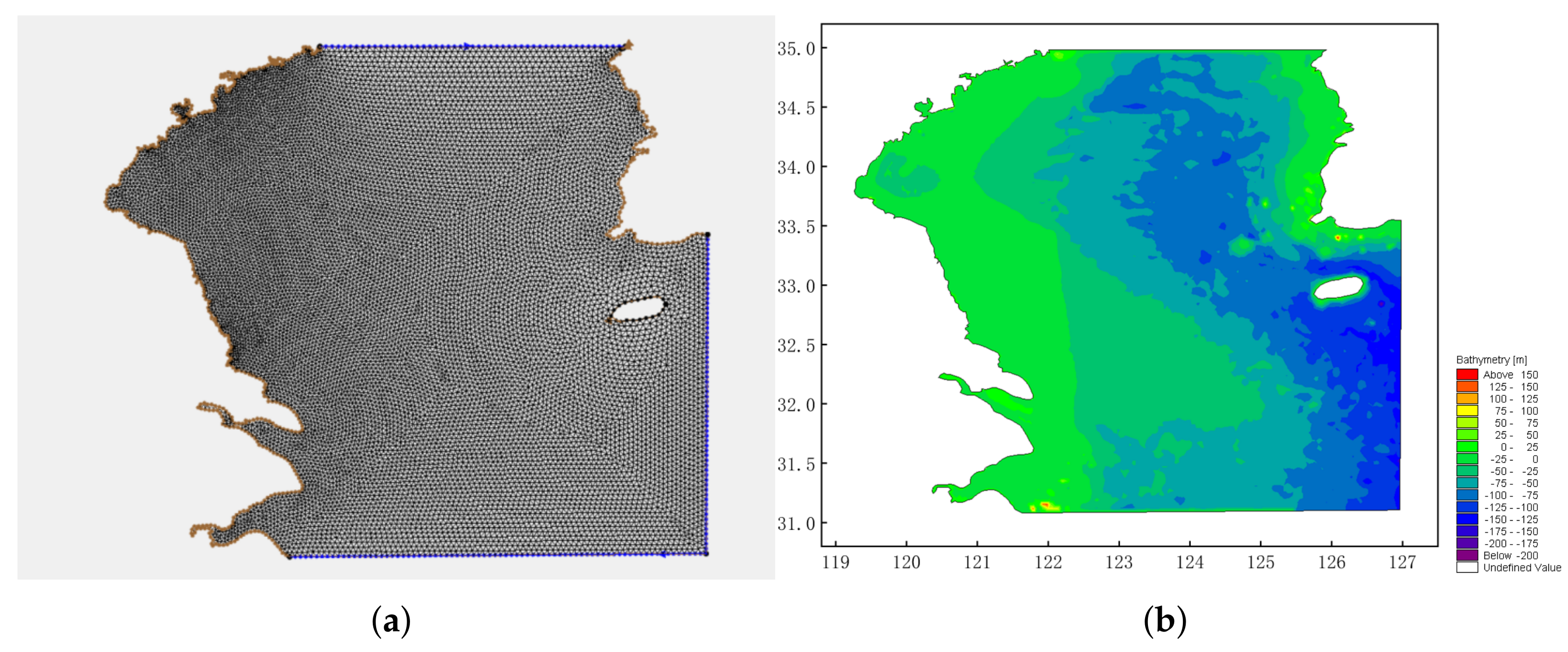

2.1. Study Area and Observations

2.2. Validation and Experiments

2.3. Wind–Wave and Swell Separation

2.4. Wave Model

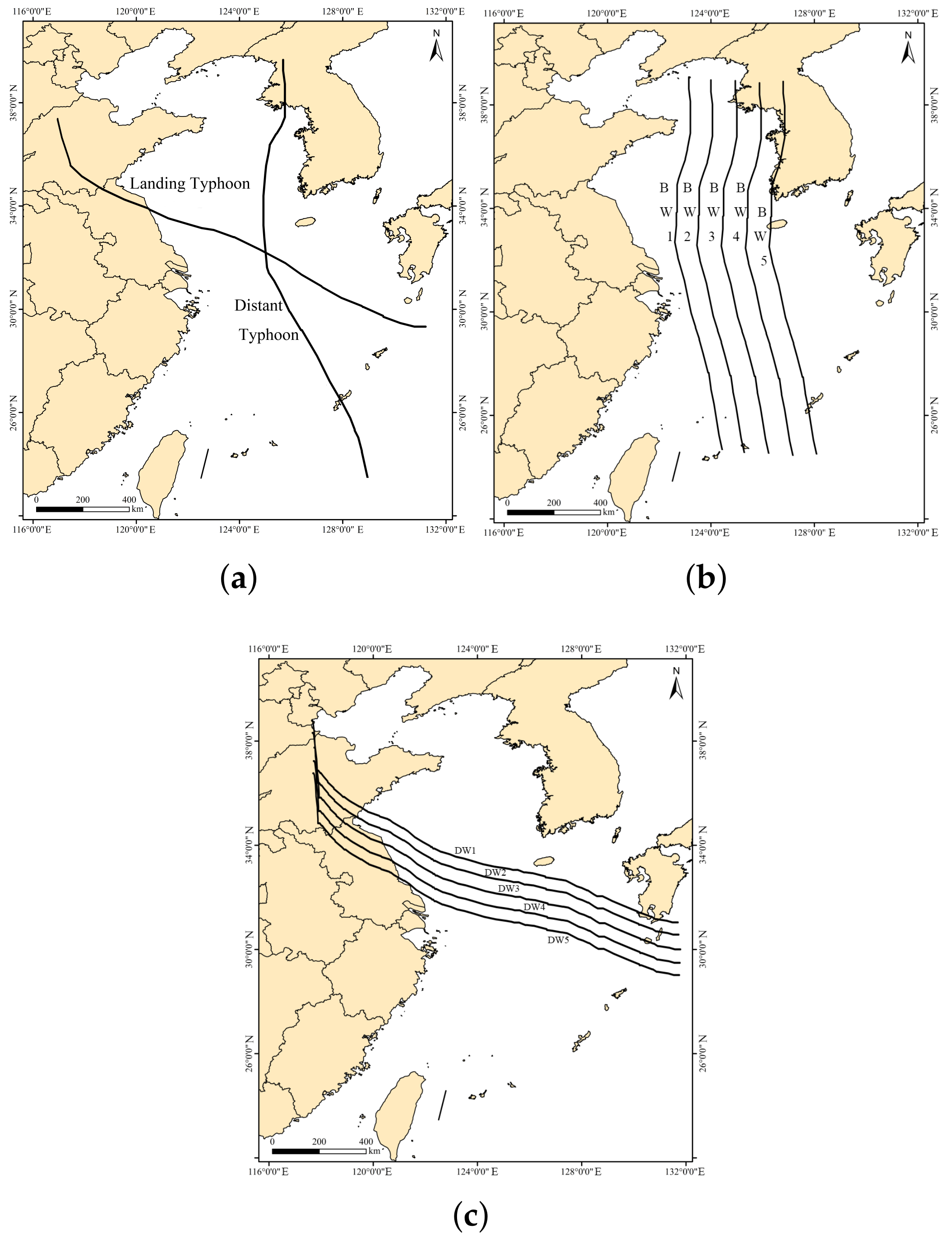

2.5. Typhoon Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

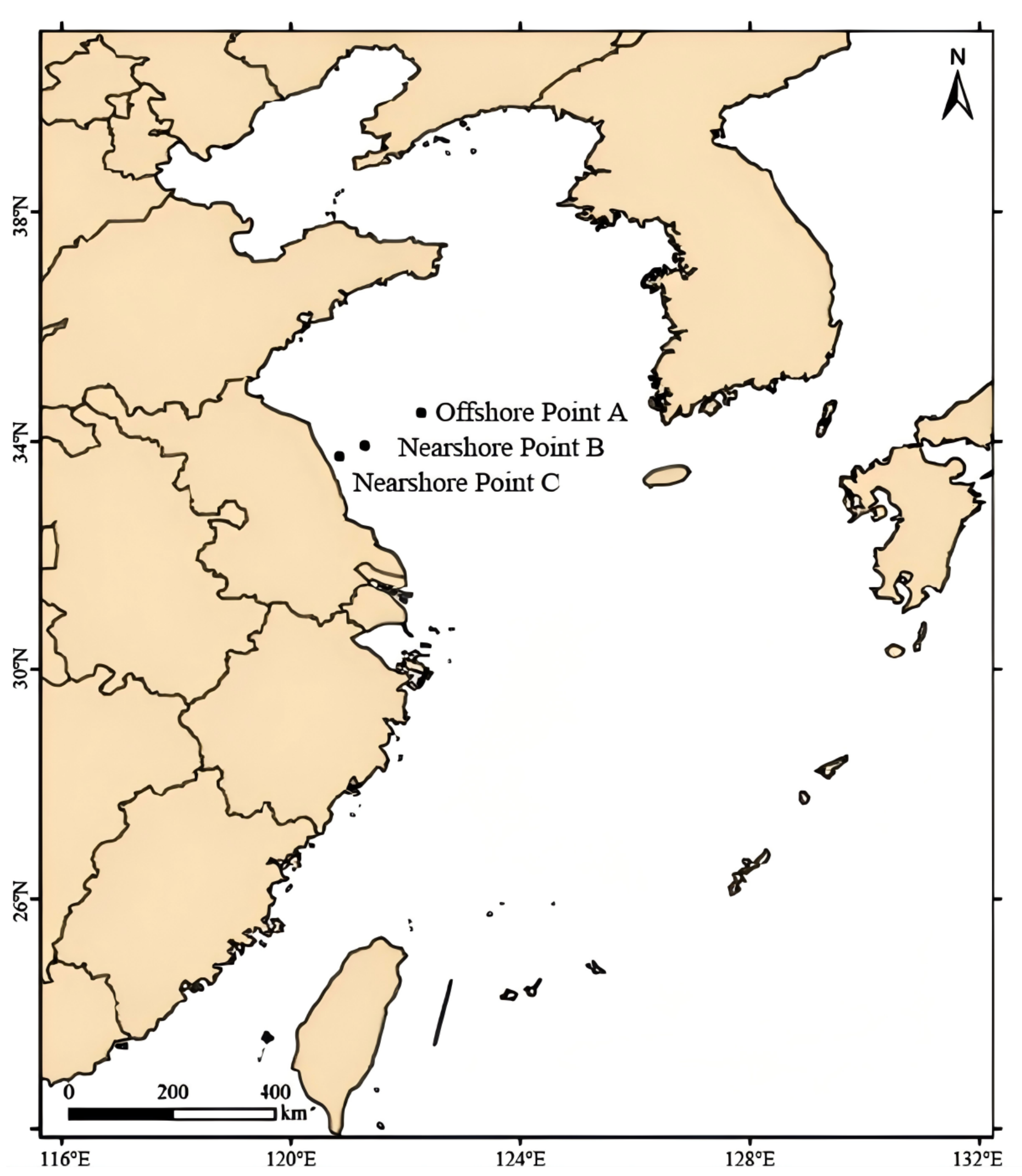

2.6. Observation Points and Locations

3. Results and Disscussion

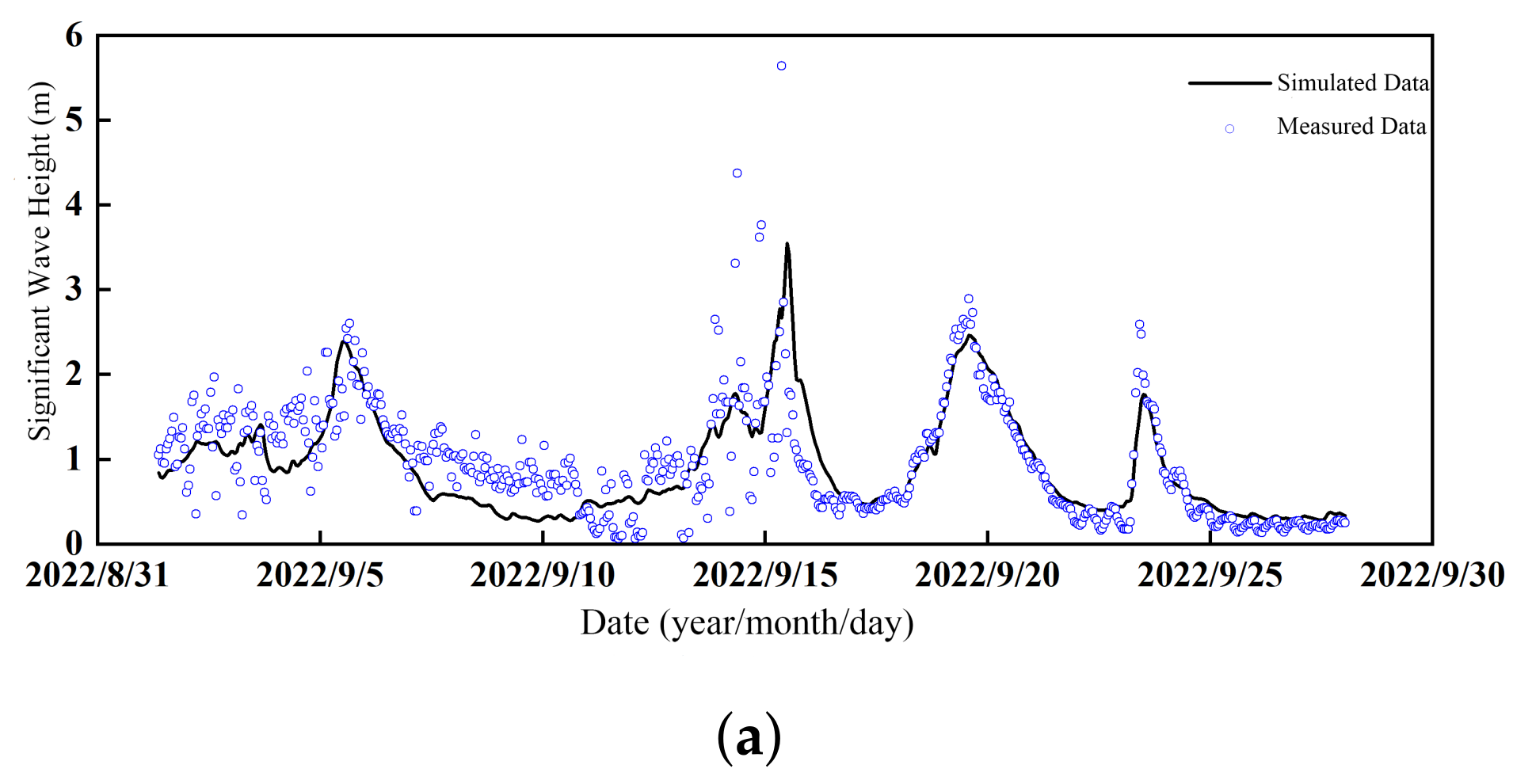

3.1. Numerical Model Validation

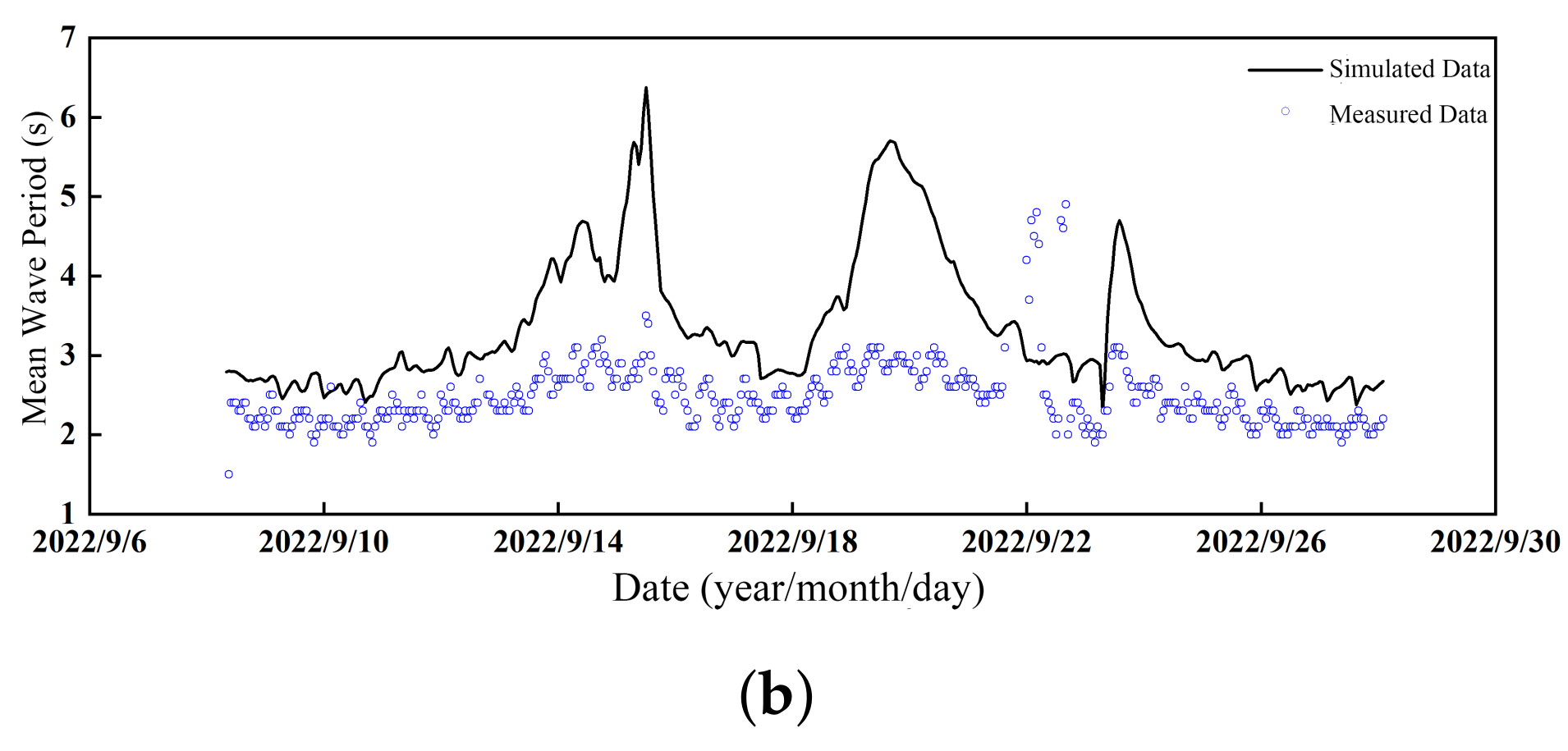

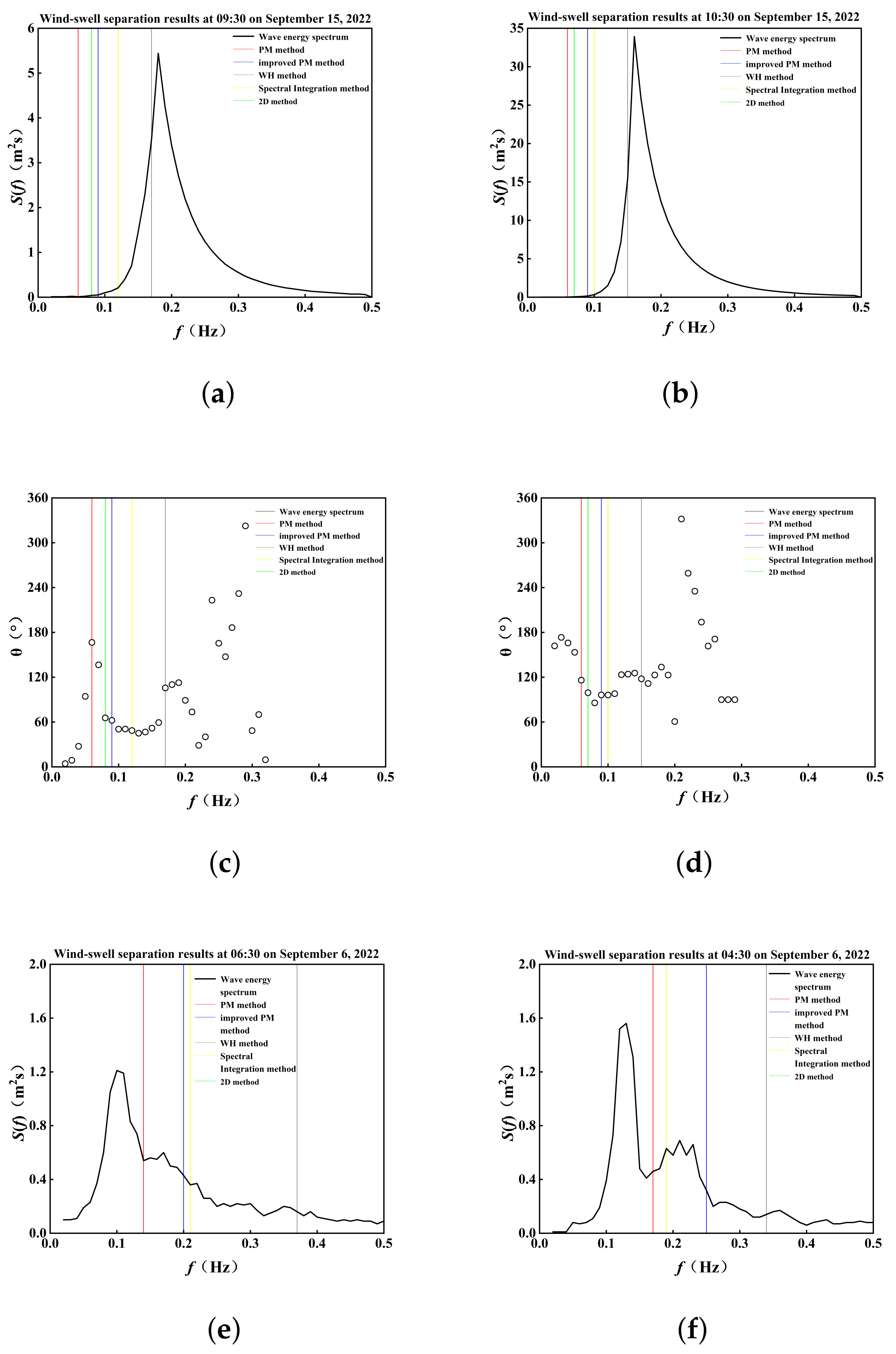

3.2. Wind–Wave and Swell Separation Results

3.3. Simulation Results of Wave Parameters Under Different Typhoon Conditions

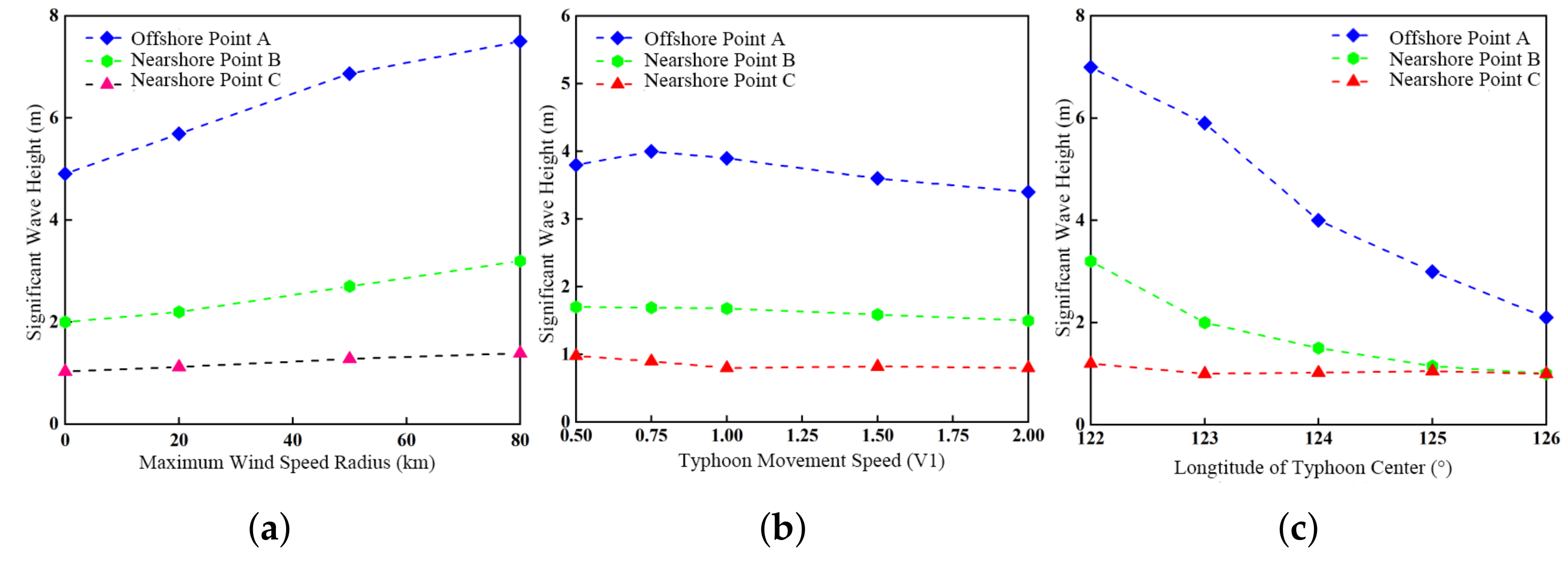

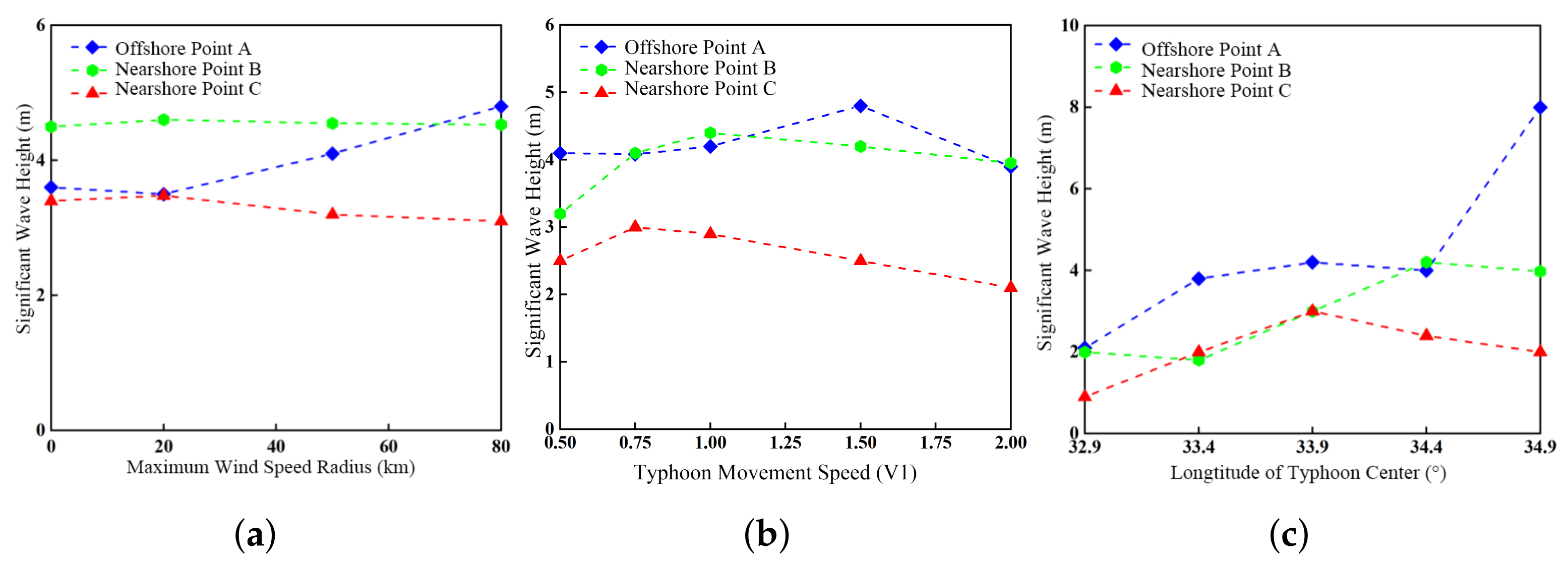

3.3.1. Significant Wave Height of Swell

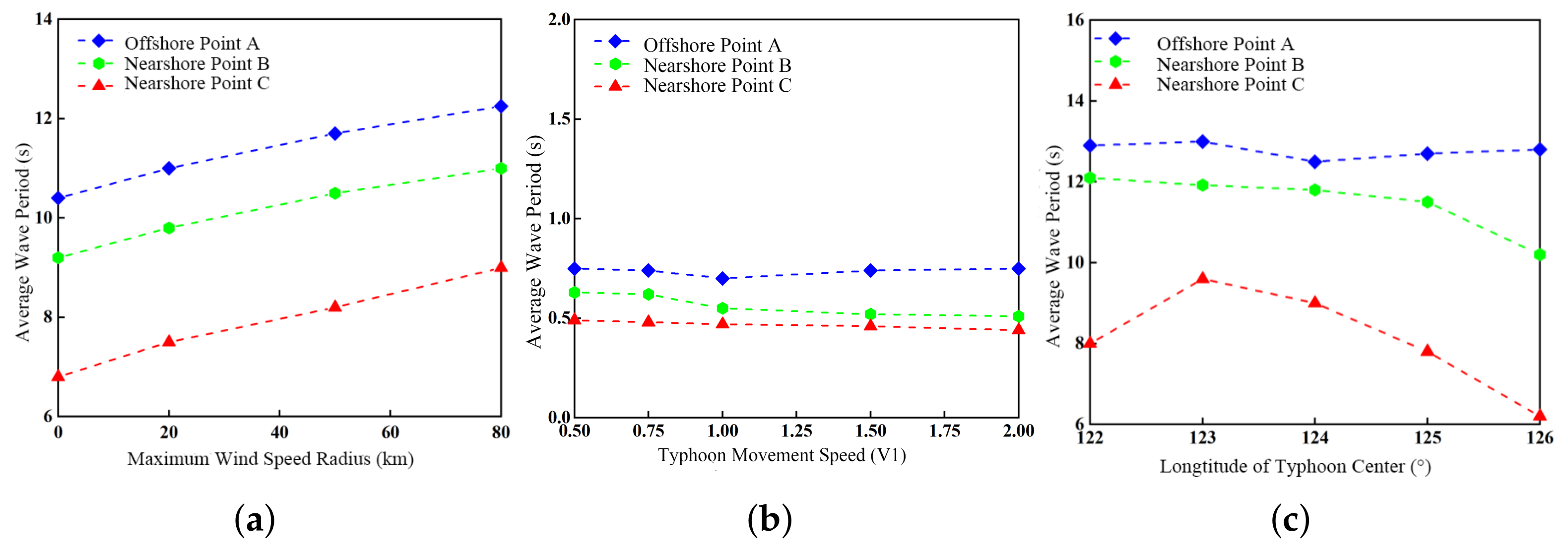

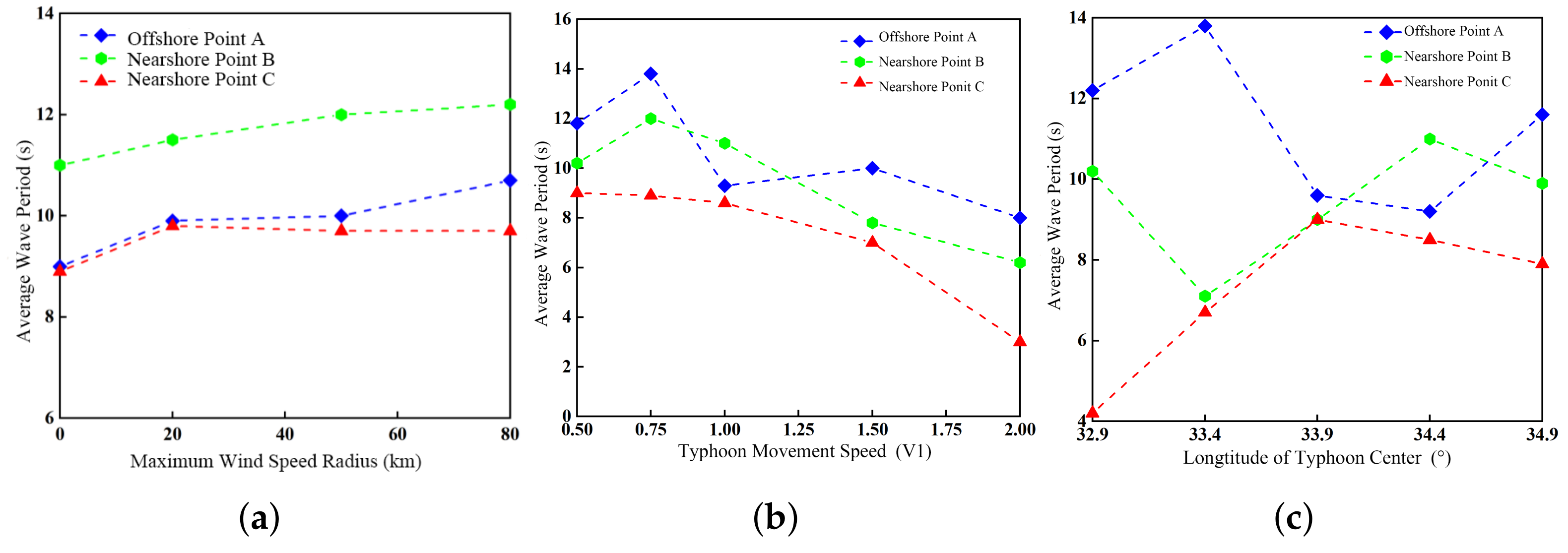

3.3.2. Average Wave Period of Swell

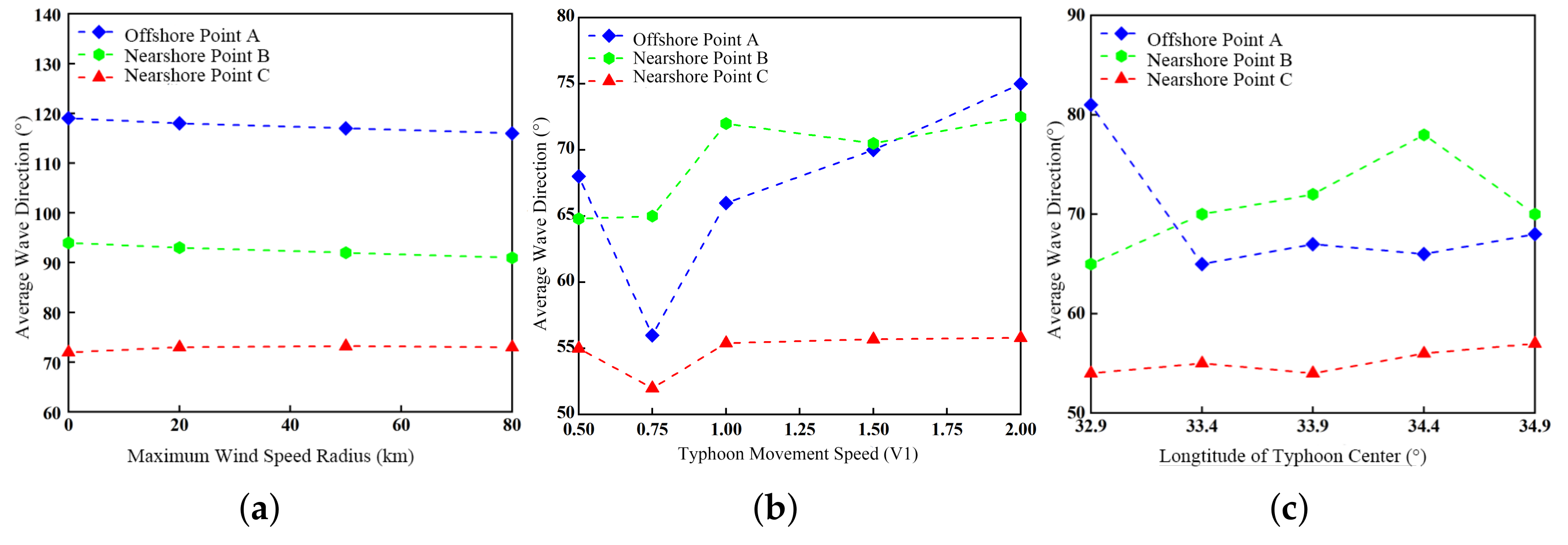

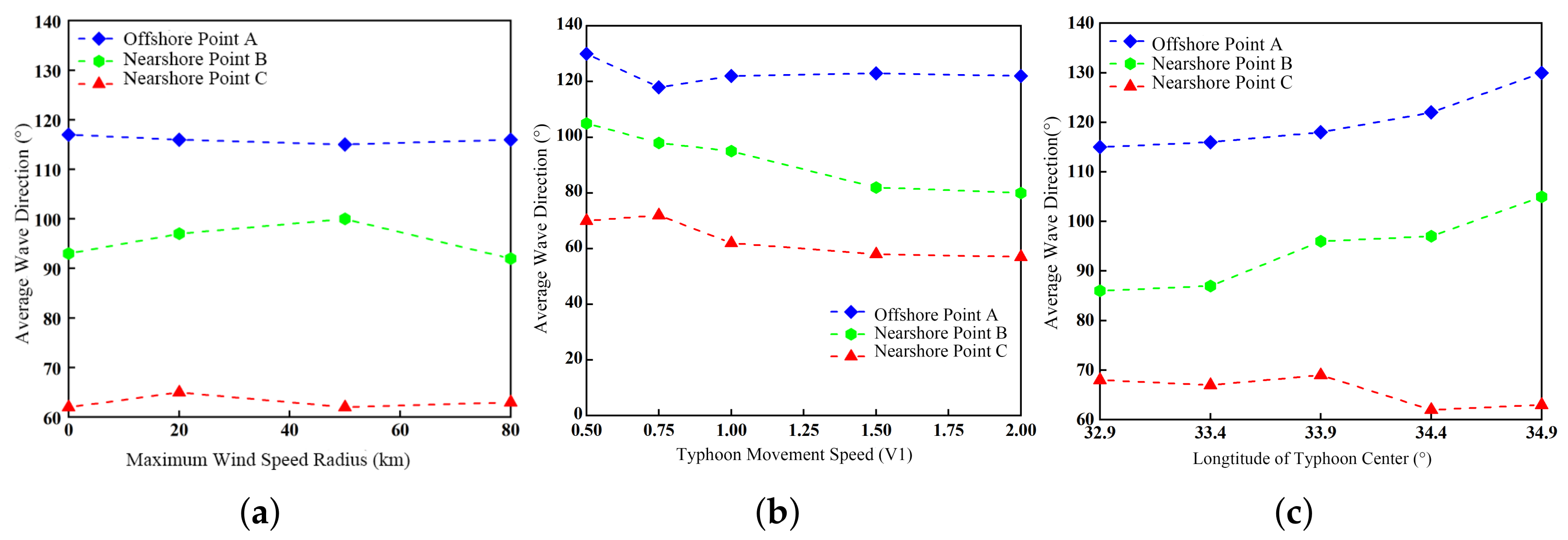

3.3.3. Average Wave Direction of Swell

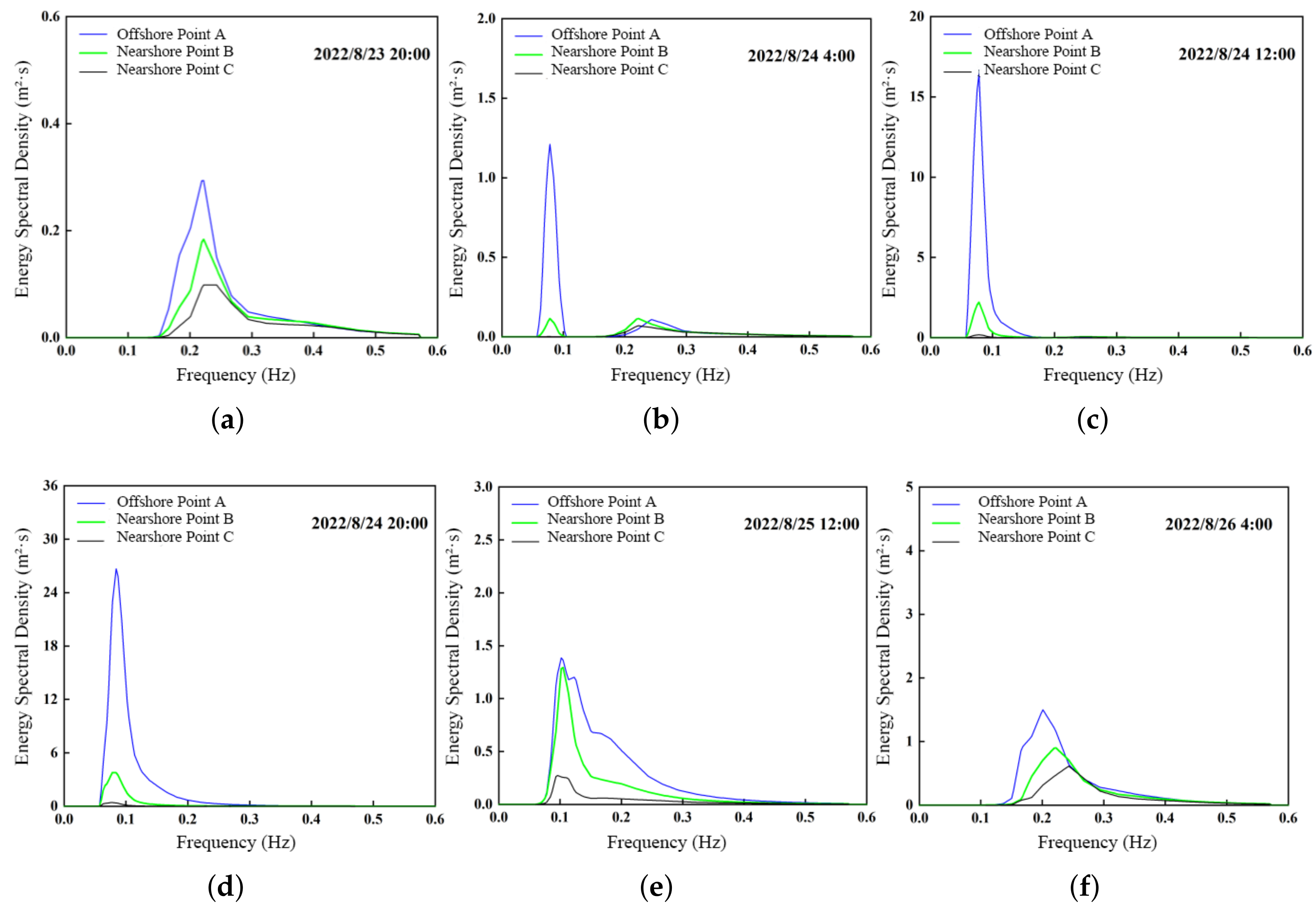

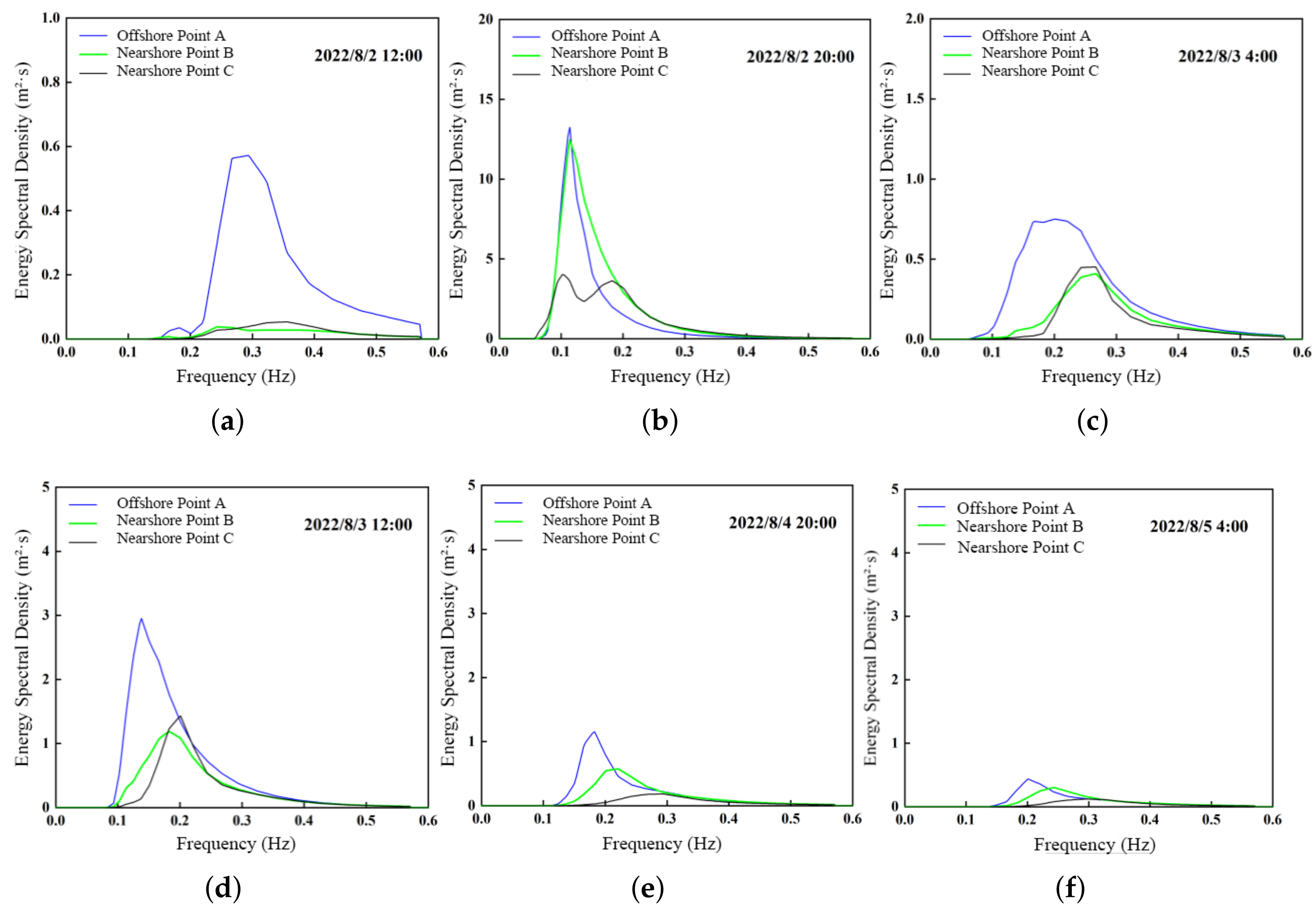

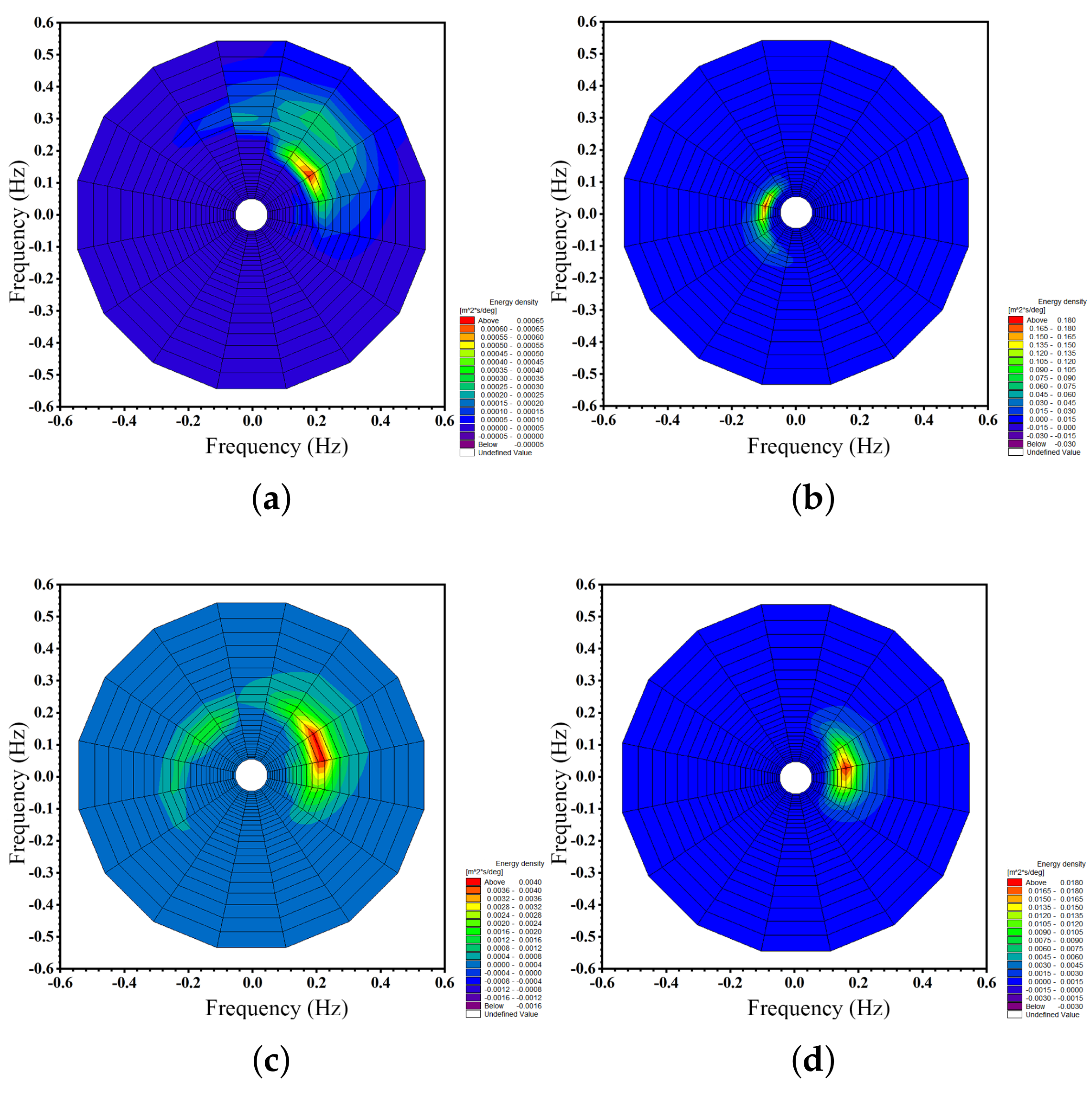

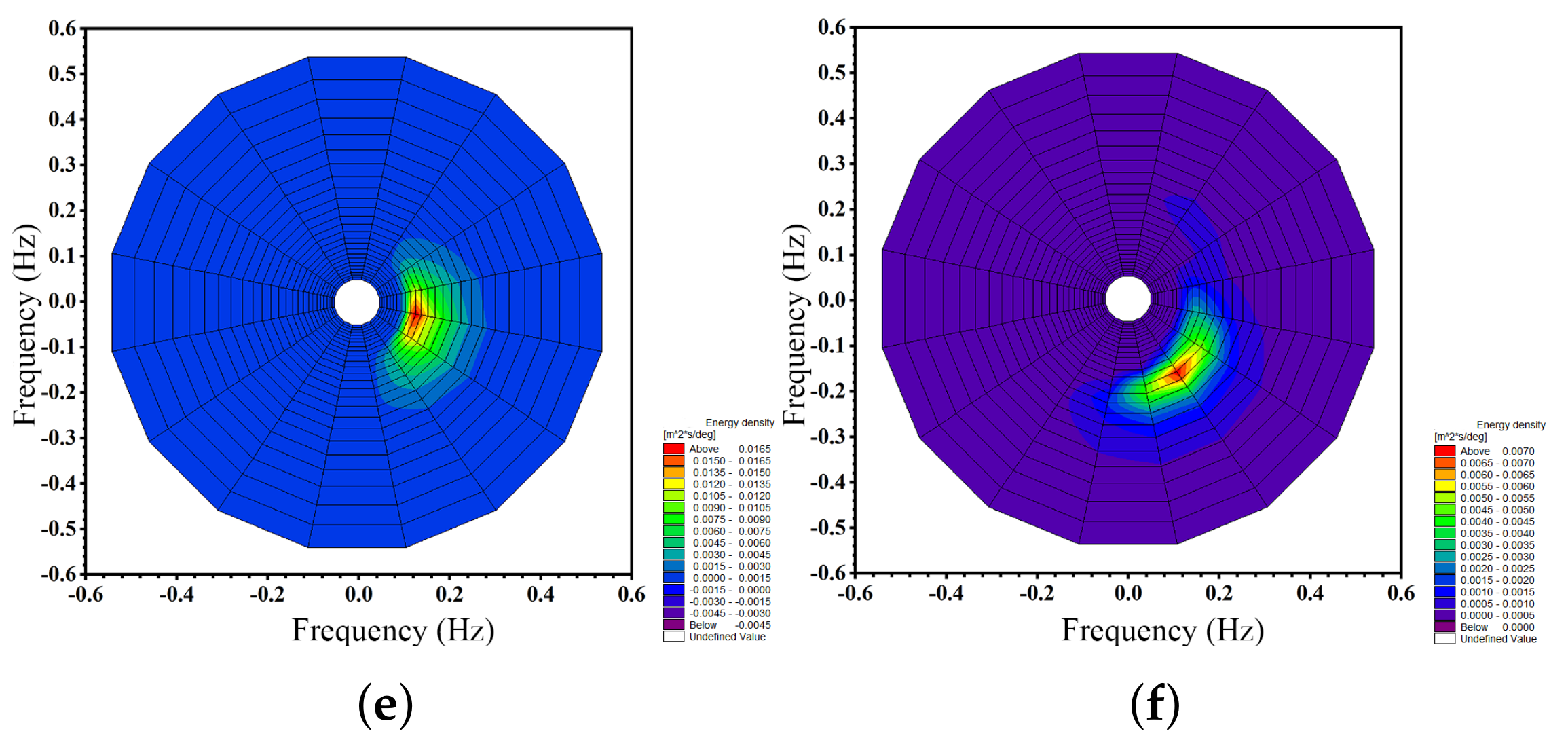

3.3.4. Characteristics of the Wave Spectrum

4. Conclusions

- The improved PM method, obtained by introducing a scaling coefficient, was compared with the standard PM method, the fixed-frequency method, and the WH method under both wind-sea-dominated and swell-dominated conditions. By combining the improved PM and WH methods, the overall separation accuracy was enhanced by 21% compared to using a single method, significantly improving applicability under complex typhoon wave conditions.

- The significant swell height is strongly influenced by the radius of maximum wind (RMW). As RMW increases from RMW0 to RMW3, the significant swell height increases from 2 m to 3.5 m, and the mean period lengthens by approximately 2 s, generating stronger and broader swells. When the typhoon translation speed is reduced to half its reference value, the significant wave height increases by about 1.2 m, and the mean period extends by 2 s. In terms of energy input, faster-moving typhoons produce concentrated but short-lived energy transfer, generating shorter-period swells; slower-moving typhoons provide more uniform and persistent forcing, producing higher-energy, longer-period swells. When the translation speed increases to 1.5 times the reference value, wave height reaches a maximum; beyond that, further acceleration results in a decrease in height. When the typhoon track passes closer to a given area, the significant swell height increases by approximately 0.8 m compared with the normal track. During distant typhoons, as the path shifts eastward (BW1 → BW5), the dominant wave direction in the directional spectrum rotates from 30° to 100°. In contrast, during landfalling typhoons (DW1 → DW5), the dominant wave direction at nearshore Point B shifts from 100° to 300°.

- The significant wave height at offshore points responds more sensitively to variations in the RMW than that at nearshore points. Moreover, the faster the typhoon moves, the smaller the difference in significant wave height between offshore and nearshore sites. Distant typhoons generate larger offshore swells (up to 7.5 m), which propagate faster and exhibit longer periods. In contrast, landfalling typhoons produce mixed wind–wave and swell systems nearshore, with maximum wave heights approximately 60% of those offshore. During distant typhoon events, the spectral peak period is generally longer than that of landfalling typhoons. Distant typhoons primarily generate swells, whereas landfalling typhoons tend to produce mixed wind–wave and swell conditions. The propagation speed of swells is faster than that of the typhoon center, reaching up to twice the typhoon’s translation speed.

- Under distant typhoon conditions, waves exhibit swell-dominated, long-period characteristics, with spectral peak periods ranging from 12 s to 14 s and dominant swell directions of N–NE. These conditions can impose sustained high loads on the wave-facing sides of offshore structures (e.g., monopile foundations), necessitating careful attention to cumulative fatigue damage in foundation components. Under landfalling typhoon conditions, waves are characterized by mixed wind–wave and swell systems with shorter periods (9 s–12 s) and highly variable dominant directions. The regional wave direction can shift abruptly by up to 90°, and the coexistence of multi-directional swells may result in sudden increases in wave height. Such multi-directional wave interactions significantly increase the complexity of the sea state and warrant focused attention in coastal disaster prevention and mitigation strategies.

- This study on surge characteristics in the Dafeng sea area during typhoons primarily focuses on landfalling and offshore-moving typhoon types, while excluding atypical tracks and interactions between multiple typhoon systems. Furthermore, research gaps remain regarding the precise mechanisms of surge generation and its interactions with other marine environmental factors during typhoon events. Future research should expand the typhoon dataset and temporal scope, investigate wave interactions during concurrent typhoons, deploy additional wave monitoring stations to analyze regional wave responses under diverse wind conditions, and enhance studies on beach evolution in response to surge dynamics. Specifically for the silt-sediment coast and active sandbar system of Dafeng Port, quantitative assessment of extreme surge impacts on estuarine bar geomorphology during typhoons warrants prioritized investigation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, B.; Chang, R.; Wang, Y. Criteria for Distinguishing Wind Waves and Swells. J. Huanghai Bohai Seas 1990, 16–24. Available online: https://navi.cnki.net/knavi/JournalDetail?pcode=CJFD&pykm=HBHH (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Guo, P.; Shi, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. A New Criterion for Distinguishing Wind Waves and Swells: Wave Components and Its Application in the South China Sea. J. Ocean. Univ. Qingdao 1997, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, T.W. Partitioning sequences and arrays of directional ocean wave spectra into component wave systems. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol. 1992, 9, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, W.M.; Graber, H.C.; Hauser, D.; Quentin, C. On the wave age dependence of wind stress over pure wind seas. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2003, 108, 8062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, M.D. Development of Algorithms for Separation of Sea and Swell; Technical Report MEC-87-1; National Data Buoy Center: Bay St. Louis, MI, USA, 1984.

- Pierson, W.J.; Moskowitz, L. A proposed spectral form for fully developed wind seas based on the similarity theory of S. A. Kitaigorodskii. J. Geophys. Res. 1964, 69, 5181–5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilla, J.; Ocampo-Torres, F.J.; Monbaliu, J. Spectral Partitioning and Identification of Wind Sea and Swell. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2009, 26, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, Y. A comparative review on the functional forms of directional wave spectrum. Coast. Eng. J. 1999, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hao, Z.; Gong, F.; Wang, T.; Chen, J. Spectral separation of wind sea and swell based on buoy observations. In Proceedings of the SPIE 9638, Remote Sensing of the Ocean, Sea Ice, Coastal Waters, and Large Water Regions 2015, Toulouse, France, 21–24 September 2015; Volume 9638, pp. 96380V–96380V–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Jeong, W.M.; Kim, S.I. Separation of Wind Sea and Swell from Nearshore Ocean Wave Spectra. Hasanuddin Univ. Press 2013, 11, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, C.; Chen, X.; Zhong, J. A Practical Method of Extracting Wind Sea and Swell from Directional Wave Spectrum. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2015, 32, 2147–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Chen, P. Numerical Simulation of Waves along the Jiangsu Coast under the Influence of Double Typhoons. Waterw. Harb. 2017, 38, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.X.; Wang, X.H.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Hemer, M.A.; Holbrook, N.J. On global wave height climatology and trends from multiplatform altimeter measurements and wave hindcast. Ocean Model. 2023, 186, 102264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.J. An Analytic Model of the Wind and Pressure Profiles in Hurricanes. Mon. Weather Rev. 1980, 108, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Oh, S.; Chang, P.; Moon, I. Optimal tropical cyclone size parameter for determining storm-induced maximum significant wave height. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1134579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Wu, Q. Relationship between size and intensity in North Atlantic tropical cyclones with steady radii of maximum wind. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL095632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mo, D.; Hou, Y.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Du, M.; Yin, B. The impact of typhoon intensity on wave height and storm surge in the northern East China Sea: A comparative case study of Typhoon Muifa and Typhoon Lekima. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.R. Parametric hurricane wave propagation model. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 1988, 114, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowyer, P.; MacAfee, A.W. The theory of trapped-fetch waves with tropical cyclones—An operational perspective. Weather Forecast. 2005, 20, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | OSB-W7 | AWAC |

|---|---|---|

| Longitude | 121.12 E | 121.26 E |

| Latitude | 33.51 N | 33.75 N |

| Parameter | Typhoon Bavi | Typhoon Damrey |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Central Pressure P (hpa) | 950 | 960 |

| Maximum Wind Speed V (m/s) | 45 | 40 |

| Radius of Maximum Wind (km) | 42–58 | 47–63 |

| Group | RMW (km) | Translation Speed (m/s) | Typhoon Track |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RMW1 RMW0 = 0.7RMW1 RMW2 = 1.3RMW1 RMW3 = 1.5RMW1 | V1 | BW1 |

| 2 | RMW1 | V1 V2 = 0.5V1 V3 = 0.75V1 V4 = 1.5V1 V5 = 2.0V1 | BW1 |

| 3 | RMW1 | V1 | BW1 BW2 BW3 BW4 BW5 |

| Group | RMW (km) | Translation Speed (m/s) | Typhoon Track |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RMW1 RMW0 = 0.7RMW1 RMW2 = 1.3RMW1 RMW3 = 1.5RMW1 | V1 | DW1 |

| 2 | RMW1 | V1 V2 = 0.5V1 V3 = 0.75V1 V4 = 1.5V1 V5 = 2.0V1 | DW1 |

| 3 | RMW1 | V1 | DW1 DW2 DW3 DW4 DW5 |

| Mixed Wave | Swell | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hs | Tm | Hs | Tm |

| RMSE | 0.386 | 1.168 | 0.317 | 1.679 |

| r | 0.800 | 0.579 | 0.601 | 0.304 |

| PM Method | Improved PM Method | WH Method | Spectral Integration Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 0.634 | 0.758 | 0.274 | 0.349 |

| r | 0.509 | 0.378 | 0.691 | 0.574 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, W.; Li, H.; Shao, Y. Wind–Wave and Swell Separation and Typhoon Wave Responses on the Dafeng Shelf (Northern Jiangsu). Water 2026, 18, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010083

Yuan Z, Zhou J, Cheng W, Li H, Shao Y. Wind–Wave and Swell Separation and Typhoon Wave Responses on the Dafeng Shelf (Northern Jiangsu). Water. 2026; 18(1):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010083

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Zhenzhou, Jingren Zhou, Wufeng Cheng, Hongfei Li, and Yuyang Shao. 2026. "Wind–Wave and Swell Separation and Typhoon Wave Responses on the Dafeng Shelf (Northern Jiangsu)" Water 18, no. 1: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010083

APA StyleYuan, Z., Zhou, J., Cheng, W., Li, H., & Shao, Y. (2026). Wind–Wave and Swell Separation and Typhoon Wave Responses on the Dafeng Shelf (Northern Jiangsu). Water, 18(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010083