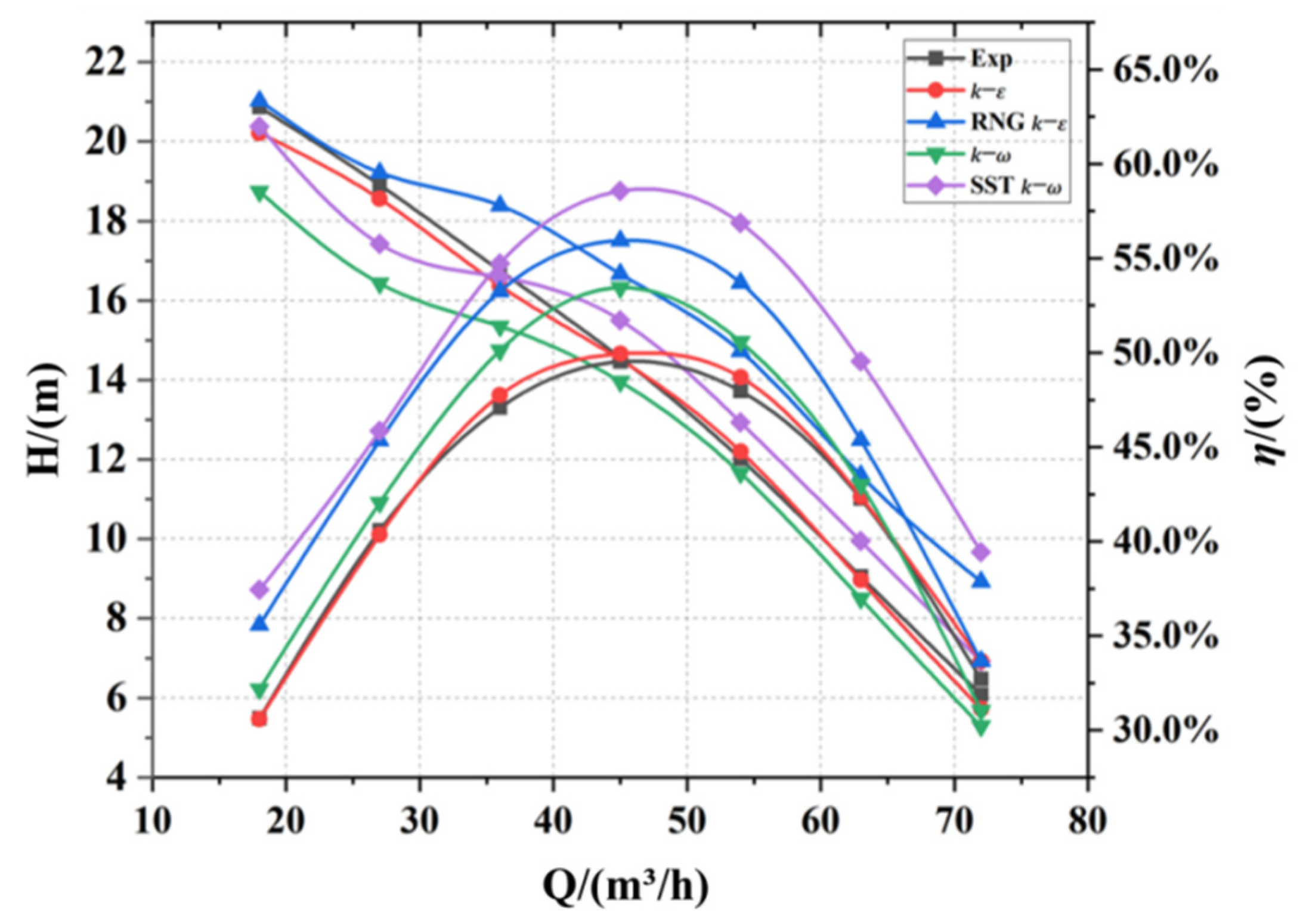

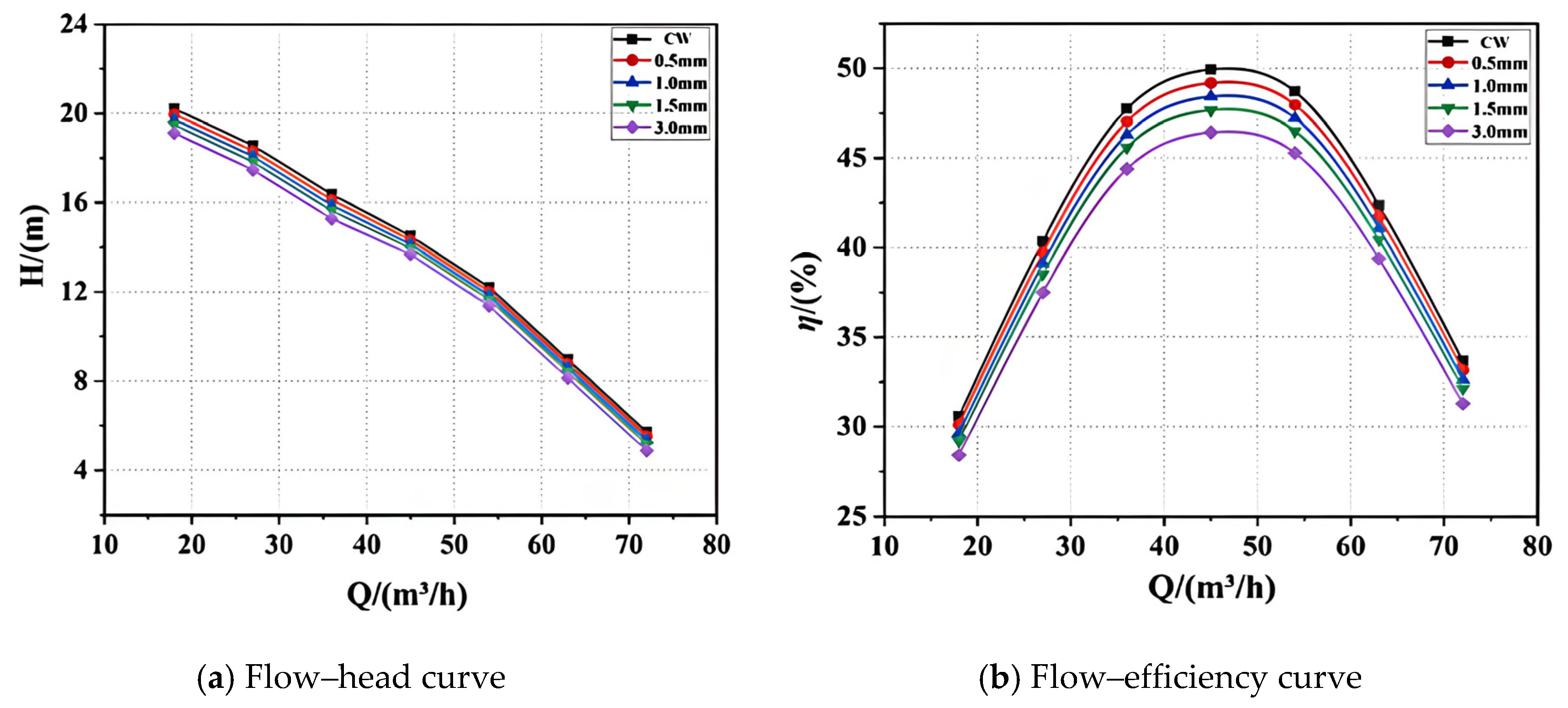

In solid–liquid two-phase flow conditions, the key factors affecting the external characteristics of the water pump are the particle size and volume fraction of solid particles. The following section presents a comparative analysis of the external characteristic data from numerical simulations of the sewage pump under different particle sizes and volume fractions. Particle sizes of 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm, and 3.0 mm, along with volume fractions of 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20%, were selected for the numerical simulations and research analysis.

4.4. Flow Field in the Pump Under Different Flow Conditions

To analyze the influence of solid particles on internal flow in a semi-open impeller sewage pump, simulations were performed at 0.6

Qd, 1.0

Qd, and 1.4

Qd with a particle diameter of 1 mm, particle density of 2300 kg/m

3, and a solid phase volume fraction of 10%.

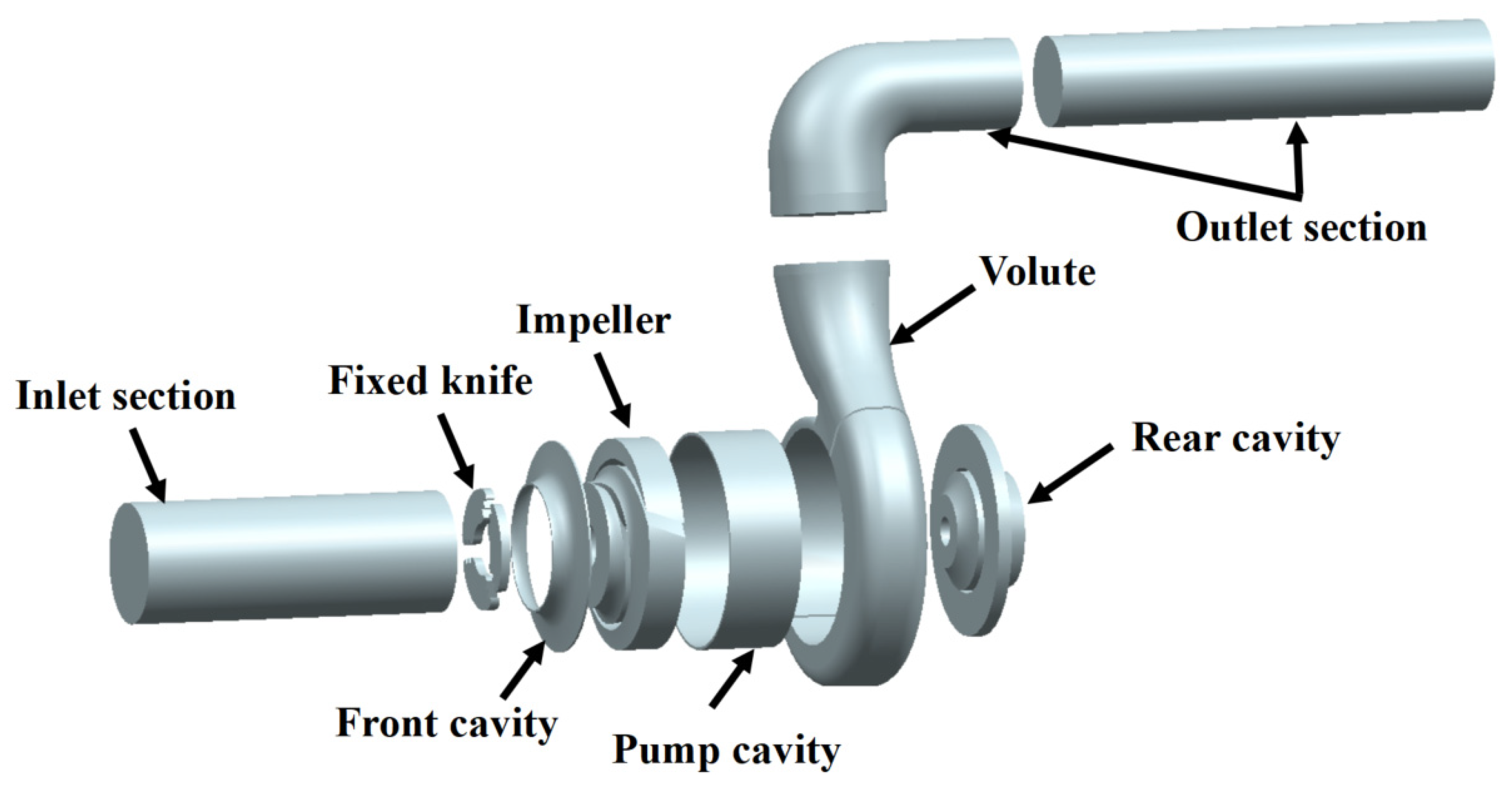

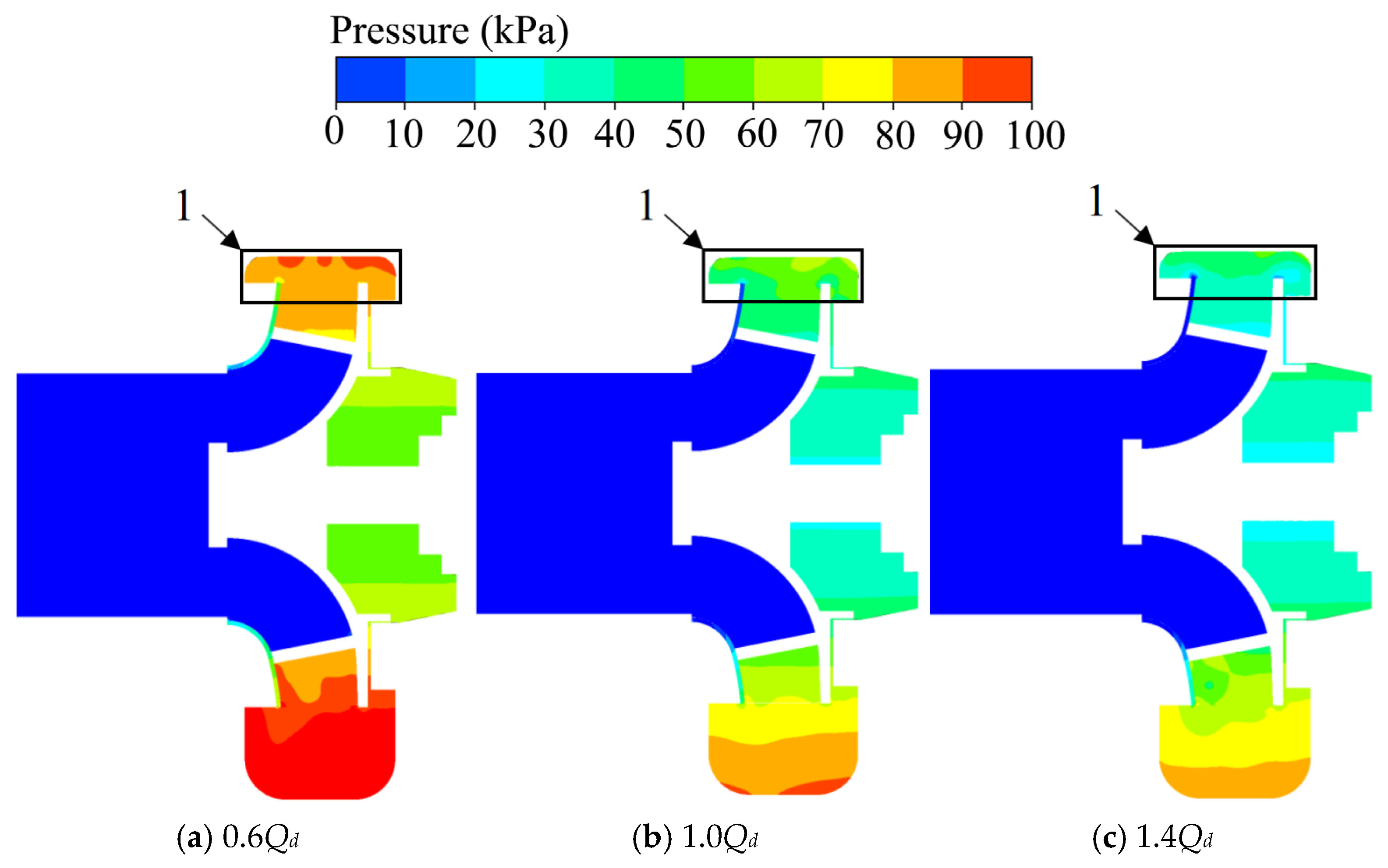

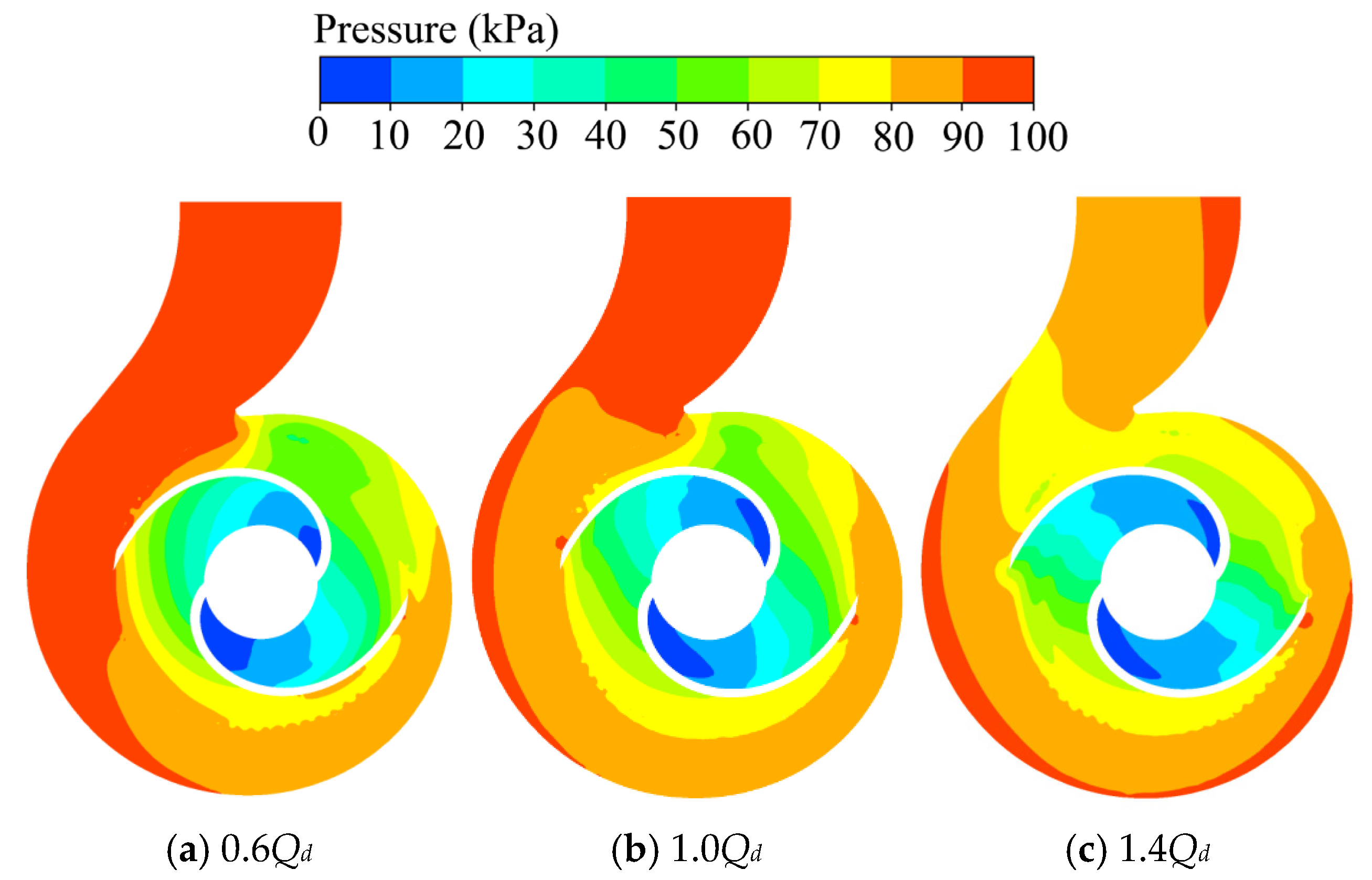

Figure 11 illustrates the pressure distribution in the radial mid-section. The fluid enters through the fixed cutter, passes through the impeller, and is discharged into the volute, with pressure gradually increasing from the inlet to the outlet, peaking in the volute. This pressure rise is primarily due to the work performed by the rotating impeller, which converts mechanical energy into hydraulic pressure energy through centrifugal force. Additionally, the pressure in the rear cavity exceeds that in the front cavity, which is a result of the asymmetric structure of the semi-open impeller.

At the small volute cross-section (Zone 1), a distinct local high-pressure zone forms under rated and low flow conditions, with the intensity more pronounced at lower flow rates. This is caused by the local geometry of the volute and the strong rotor-stator interaction, which creates a pressure buildup in the volute region. As the flow rate increases, the pressure rise in this region weakens. This weakening is attributed to the increasing flow velocity, which mitigates the pressure buildup and reduces the intensity of the rotor-stator interaction, allowing for a more uniform distribution of pressure across the volute. The presence of solid particles, especially at higher concentrations, can further exacerbate these pressure variations due to increased particle-fluid interactions, which affect both flow stability and the efficiency of pressure conversion within the pump.

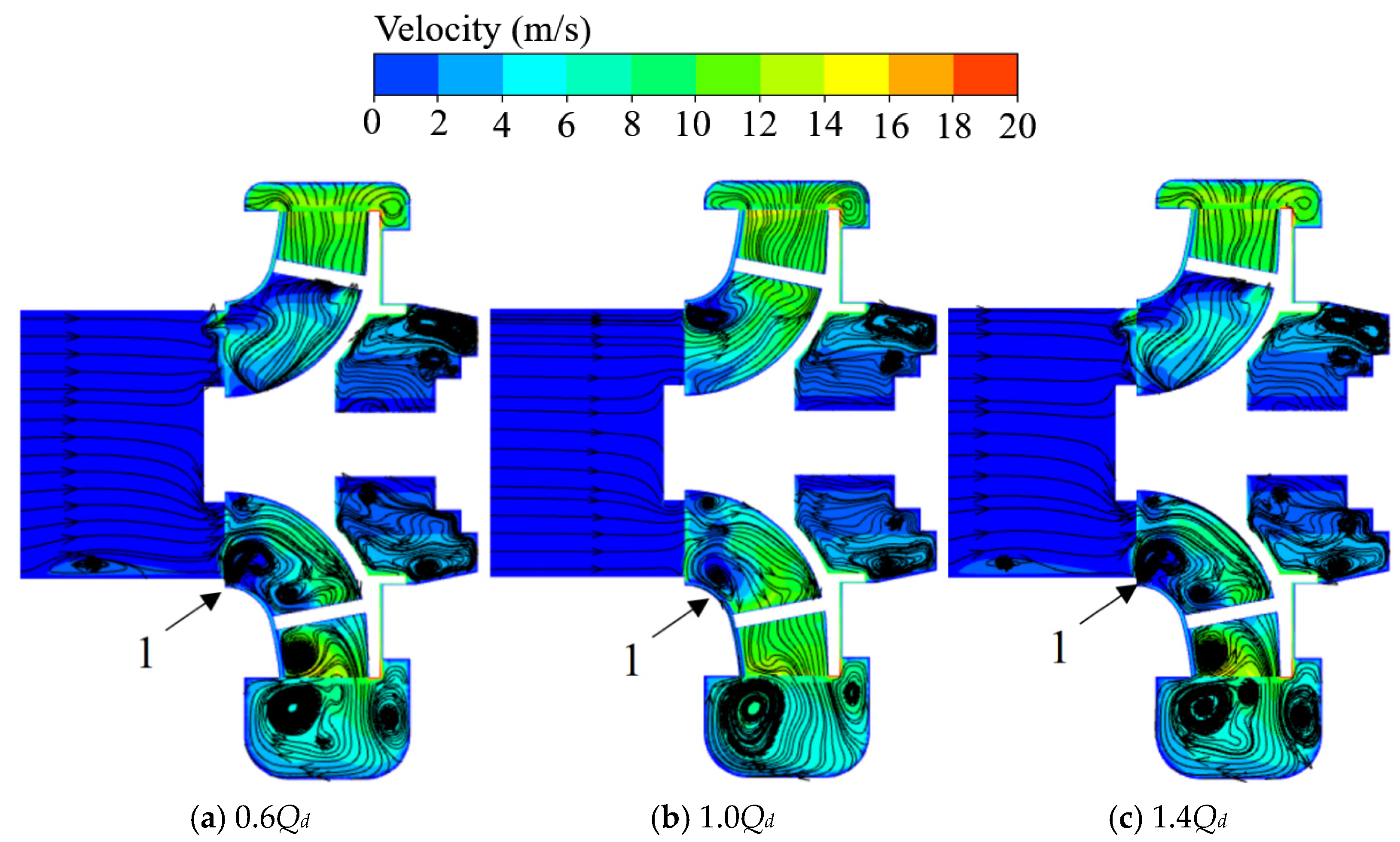

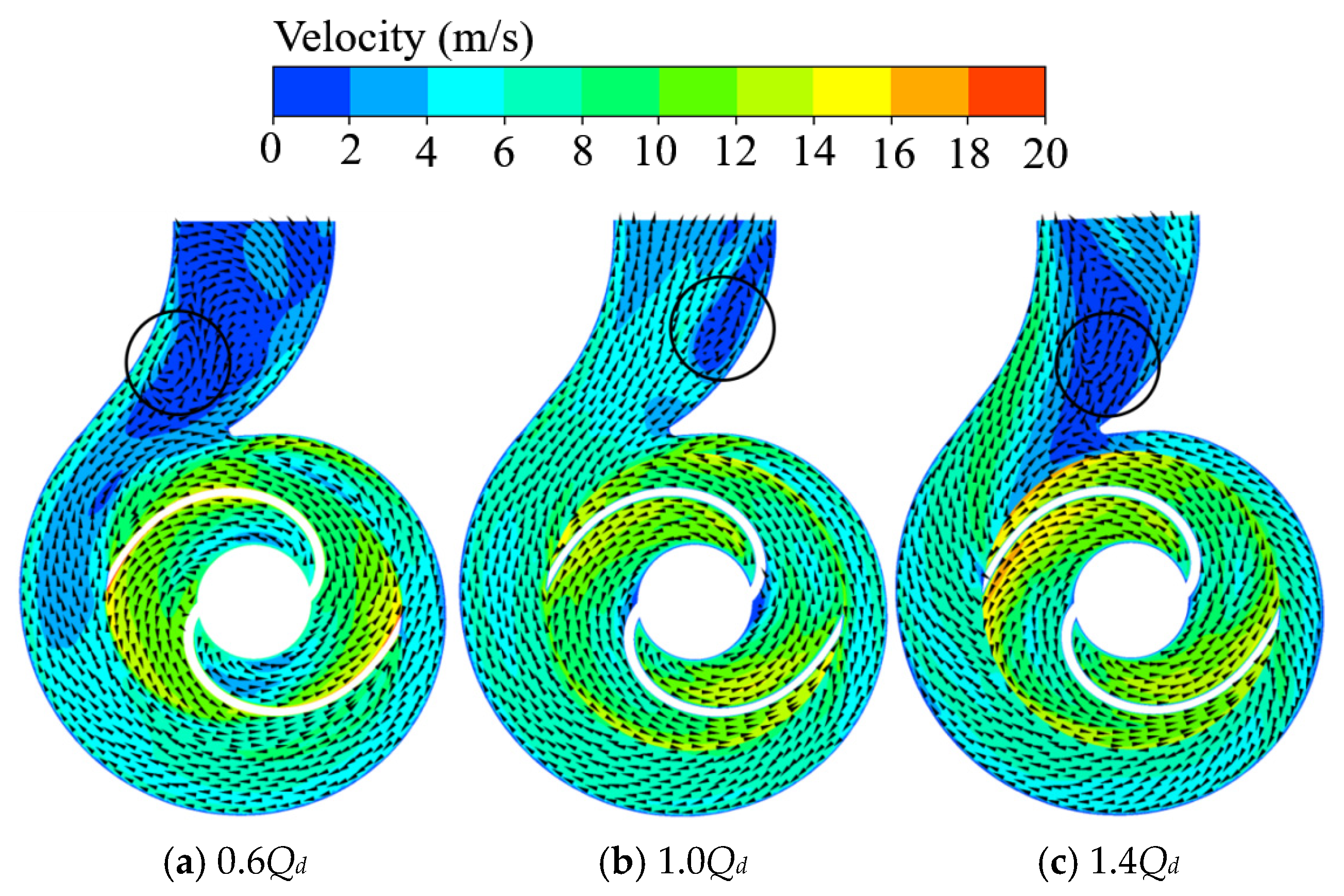

Figure 12 shows the velocity distribution in the radial mid-section of the sewage pump under flow conditions of 0.6

Qd, 1.0

Qd, and 1.4

Qd. As shown in the figure, the fluid enters the impeller through the fixed cutter from the pump inlet and then flows into the volute channel. Inside the impeller, the fluid gradually accelerates from the impeller inlet and reaches its maximum velocity at the impeller outlet. This increase in velocity is primarily driven by the transfer of kinetic energy from the rotating impeller blades to the fluid. A notable feature observed in the figure is the occurrence of backflow phenomena of varying degrees in both the impeller and rear cavity regions. This backflow is primarily due to the geometry of the fixed cutter at the front section of the impeller inlet, which disrupts the fluid flow near the impeller inlet. The altered flow path induces flow separation, creating low-pressure zones that lead to backflow at the impeller inlet. The intensity of the backflow varies with the flow rate, being more pronounced at lower flow rates (Zone 1).

Figure 13 illustrates the solid-phase distribution in the radial mid-section of the sewage pump under flow conditions of 0.6

Qd, 1.0

Qd, and 1.4

Qd. As depicted in the figure, solid particles predominantly accumulate within the flow channels of both the impeller and volute. Under low-flow conditions, the solid phase receives less kinetic energy, resulting in a relatively concentrated and uneven distribution, particularly in the volute (Zone 1). This is due to the insufficient kinetic energy imparted to the particles, which hinders their ability to overcome local resistance, causing them to accumulate in regions of lower flow velocity. As the flow rate increases, the solid particles acquire more kinetic energy, enabling them to overcome local resistance more effectively. Consequently, the distribution of the solid phase becomes progressively more uniform, with particles spreading toward the periphery of the flow channels, both in the impeller and volute. This behavior is governed by a complex interaction between fluid dynamics and particle inertia. As the flow rate increases, the solid particles gain sufficient energy to mix more thoroughly with the liquid phase, leading to a more homogeneous particle distribution. However, due to their larger inertia, larger particles continue to lag behind the main flow direction, resulting in a higher concentration of particles in certain localized regions, particularly in areas with lower flow velocities, such as the volute.

Figure 14 shows the pressure distribution in the volute mid-section under various flow conditions. As shown in the figure, the pressure increases progressively from the impeller inlet to the outlet region, with the radial pressure gradient being primarily driven by the centrifugal work performed by the rotating impeller. The pressure reaches its maximum value near the volute outlet. However, as the flow rate increases, the high-pressure zone near the volute outlet gradually diminishes, while the pressure within the flow channel increases slightly. This phenomenon occurs because the increase in flow rate enhances the fluid’s kinetic energy, which in turn exerts a greater impact on the volute flow channel. As a result, there is a slight increase in pressure in certain areas within the volute flow channel. This leads to an increase in hydraulic losses along the flow path, contributing to a decrease in the outlet pressure. The interaction between the increased flow rate and the geometry of the volute results in more complex pressure dynamics, ultimately influencing the pump’s overall efficiency and performance.

Figure 15 illustrates the velocity distribution in the volute mid-section. As shown in the figure, as the fluid passes through the impeller, its velocity increases progressively from the inlet to the outlet. Notably, the flow velocity on the suction side of the blade is higher than that on the pressure side, with the maximum velocity occurring near the trailing edge of the outlet. Upon entering the volute channel, the flow velocity decreases rapidly due to the sudden expansion of the cross-sectional area, a phenomenon observed across all operating conditions. However, in the lower wall region of the volute diffuser, flow separation occurs, resulting in relatively low flow velocities near the wall around the tongue. This is accompanied by backflow phenomena of varying intensities.

Figure 16 shows the solid-phase distribution in the volute mid-section under flow conditions of 0.6

Qd, 1.0

Qd, and 1.4

Qd. As indicated in the figure, solid particles are mainly distributed in the impeller flow channels, while in the volute, they are mainly attached to the inner wall of the volute. It can be clearly observed that the volume fraction of particles on the pressure side of the impeller is higher than that on the suction side. This is primarily because the solid particles, having higher density and inertia than water, cannot strictly follow the curved streamlines and tend to accumulate on the blade’s pressure surface. As the flow rate increases, the high-concentration particle area on the impeller (Zone 1) gradually shrinks. Under the large flow condition, the number of particles on the inner wall of the volute decreases, while the particle distribution at the volute outlet increases. At a larger flow rate, the higher fluid velocity provides a stronger carrying capacity, allowing particles to follow the flow more easily and pass through the pump.

4.5. Analysis of Internal Flow Field Under Different Particle Size Conditions

To investigate the influence of particle size on the internal flow performance of a semi-open impeller sewage pump, numerical simulations were conducted under the design flow rate of 1.0Qd and a volume fraction of Cv = 10%, with particle diameters (ds) of 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm, and 3.0 mm, respectively. The simulation results were analyzed accordingly.

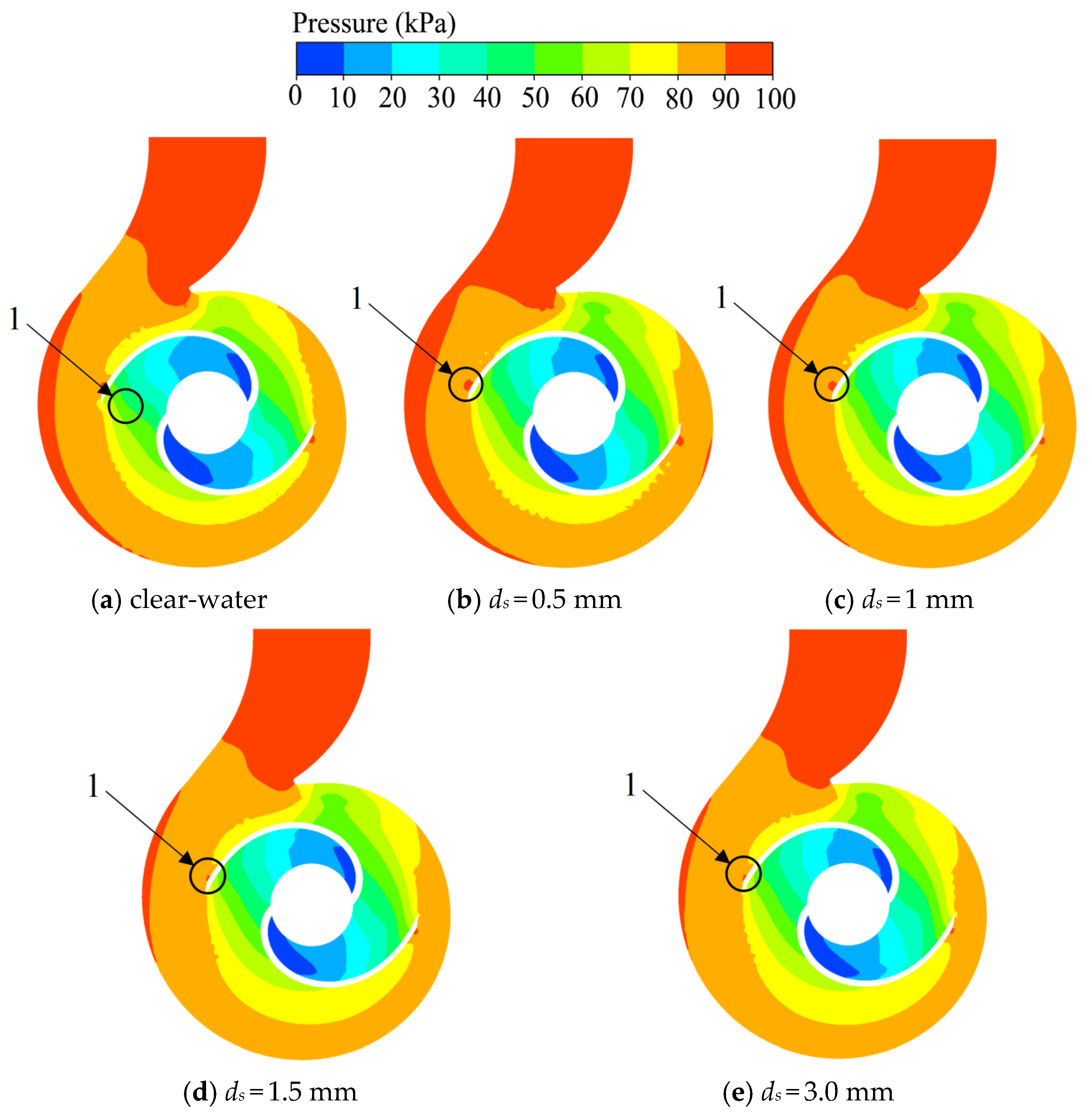

Figure 17 shows the pressure contour plots of the radial mid-section of the sewage pump under the 1.0

Qd flow rate for the clear water condition and the conditions with particle diameters (

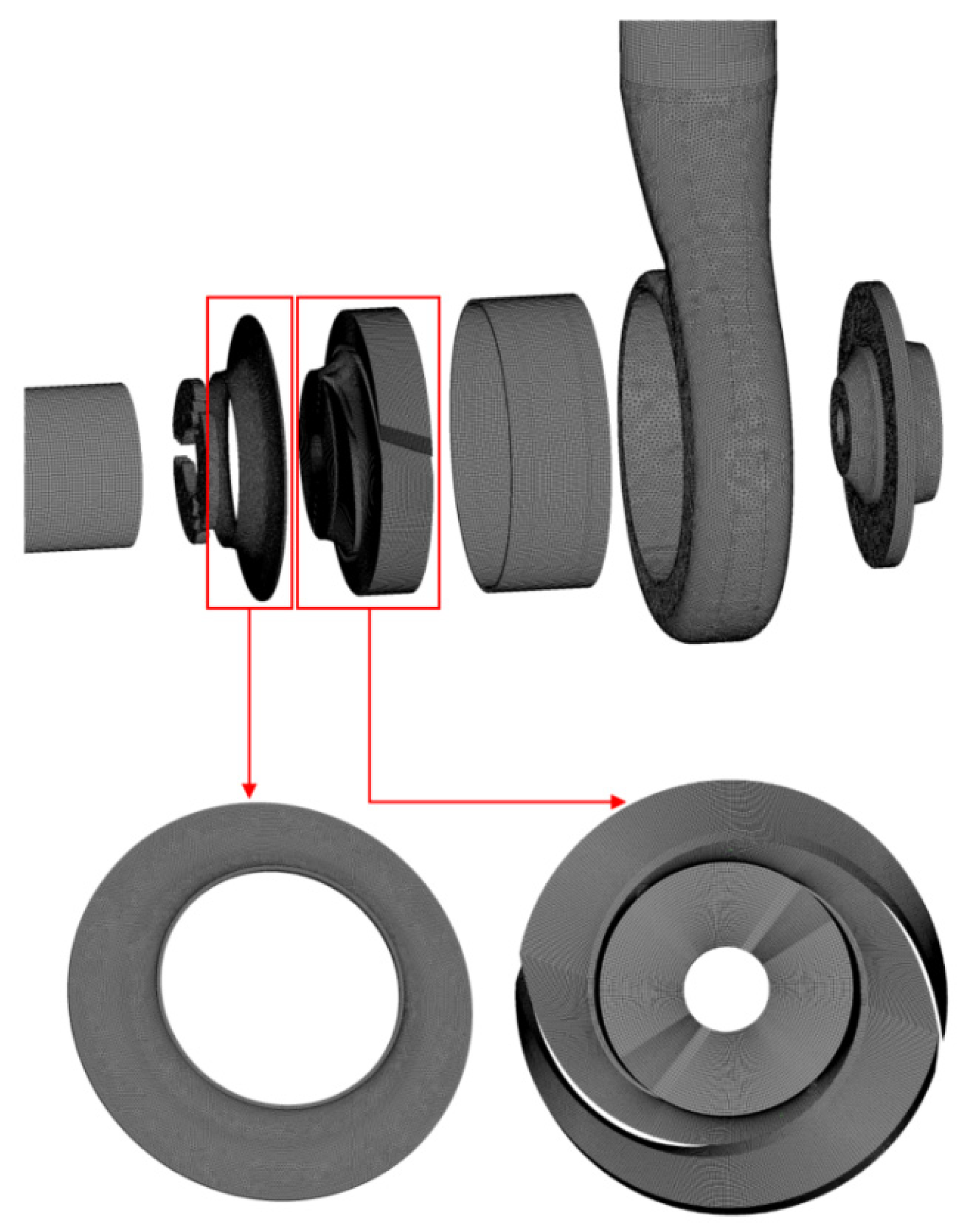

ds) of 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm, and 3.0 mm. As indicated in the figure, compared with the single clear water condition, after adding solid particles into the fluid, the pressure distribution gradient in the section increases significantly. This is primarily attributed to the increased energy consumption caused by the solid–liquid interaction. The fluid transfers pressure energy to the solid particles to accelerate them, resulting in a steeper pressure gradient. Under the rated flow rate, the overall pressure distribution pattern inside the pump is similar. When the particle diameter increases from 1 mm to 3 mm, the pressure in the rear cavity gradually decreases, while the pressure in the volute channel changes slightly. The presence of solid particles increases the pressure difference between the rear cavity (Zone 1) and the volute channel (Zone 2). The increase in this pressure difference will directly enhance the axial force on the impeller, which may exacerbate the bearing load and the risk of wear.

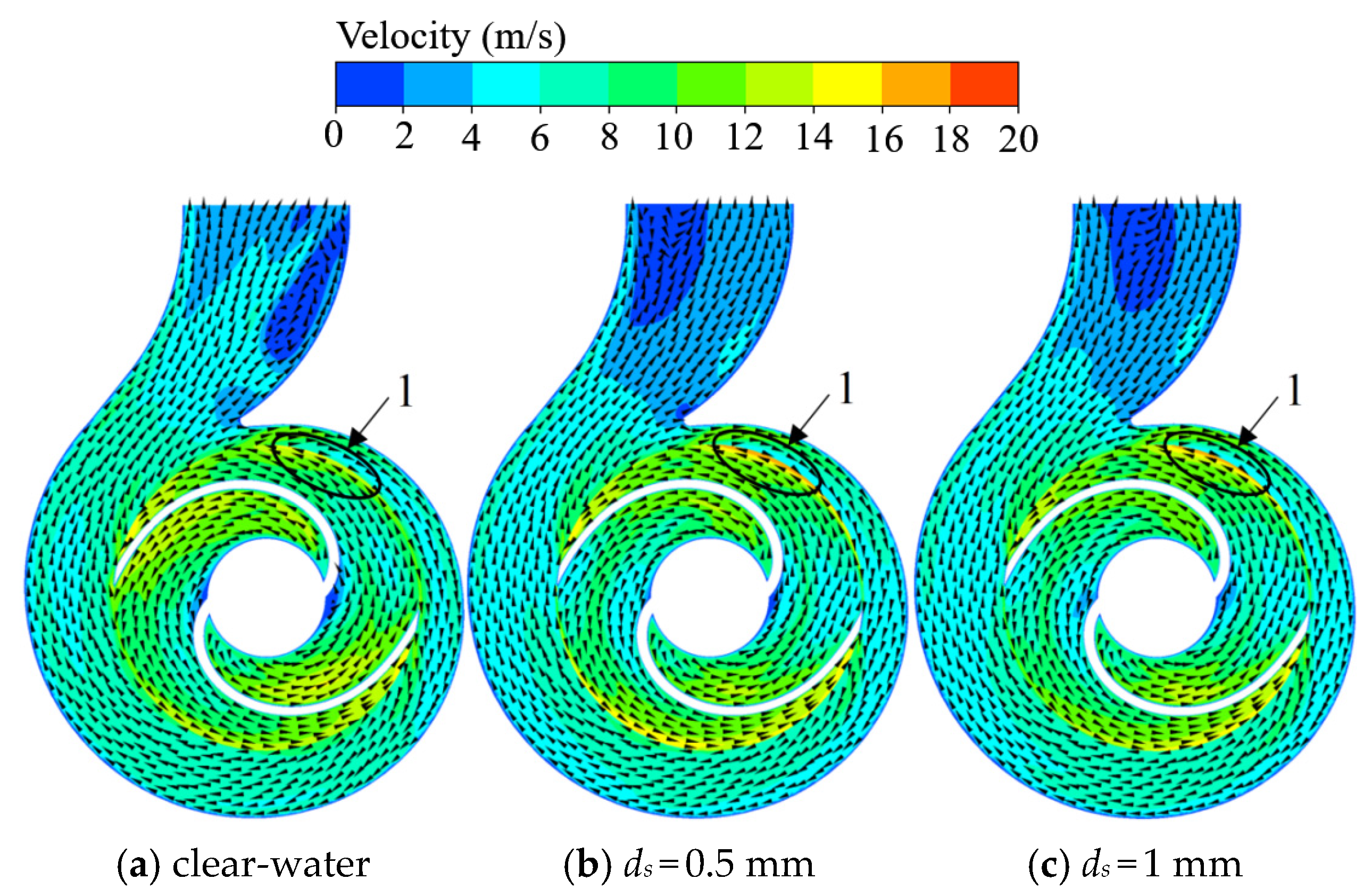

Figure 18 presents the velocity contour plots of the radial mid-section of the sewage pump under a 1.0

Qd flow rate for both the clear water condition and conditions with particle diameters (

ds) of 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm, and 3.0 mm. As shown in the figure, backflow is observed to varying degrees in both the impeller and pump cavity regions (Zone 1, Zone 2). Clear flow separation and stall wake zones are evident at the impeller inlet and within the volute channel, suggesting that these regions experience significant dynamic-static interference. Moreover, more pronounced backflow is observed in the rear cavity region, indicating that additional hydraulic losses occur here.

As the diameter of the solid particles increases, their ability to follow the liquid phase diminishes, resulting in a reduction in the overall flow velocity in the rear cavity of the sewage pump. This reduced flow velocity means that the impeller must exert additional work on the particles, which leads to a decline in the pump’s transmission efficiency. This phenomenon is reflected in the trend that both the pump head and efficiency decrease as the particle size increases. The weakening of the particles’ ability to align with the flow dynamics contributes to increased energy dissipation and reduced pump performance, particularly in the regions of flow separation and backflow.

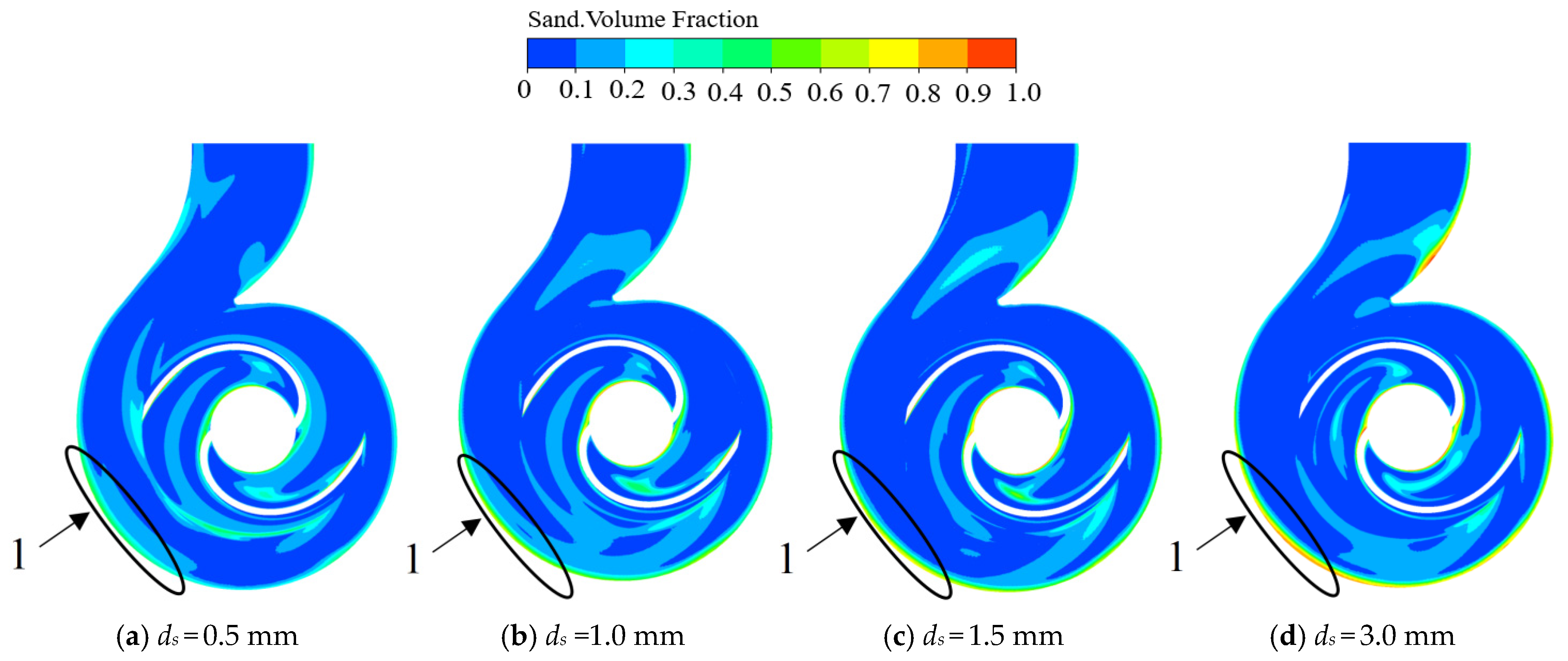

Figure 19 shows the solid-phase distribution plots in the radial mid-section of the sewage pump under a 1.0

Qd flow rate for both the clear water condition and conditions with particle diameters (

ds) of 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm, and 3.0 mm. As indicated in the figure, solid particles are primarily concentrated within the impeller and volute flow channels. As the particle diameter increases, there is a significant increase in the concentration of solid particles along the inner wall of the volute (Zone 1). This is because larger particles require more kinetic energy to maintain the same motion, resulting in a higher volume fraction of larger particles in the volute. In contrast, the distribution of solid particles in the impeller flow channels tends to become more uniform as particle size increases. This uniformity occurs because, at higher flow rates and larger particle sizes, the particles are more evenly dispersed in the impeller due to increased mixing, although their movement is still influenced by their larger inertia. The accumulation of larger particles along the volute wall further emphasizes the influence of particle size on the flow dynamics, as the larger particles are less able to follow the flow, leading to their concentration in regions of lower velocity.

Figure 20 shows the pressure distribution in the volute mid-section of the sewage pump under the 1.0

Qd flow rate for the clear water condition and the conditions with particle diameters (

ds) of 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm, and 3.0 mm. As indicated in the figure, from the impeller inlet to the outlet, the pressure gradually increases along the radial direction, reaching a peak at the volute outlet. This pressure build-up is generated by the rotating impeller converting mechanical energy into hydraulic energy. Meanwhile, a local high-pressure zone is formed at the junction of the impeller outlet and the pump cavity (Zone 1). Notably, as the solid particle diameter increases, the range of this local high-pressure zone gradually shrinks. This is fundamentally because larger particles possess higher inertia and drag. The fluid must consume more pressure energy to accelerate and transport these coarser particles, leading to a reduction in the local static pressure.

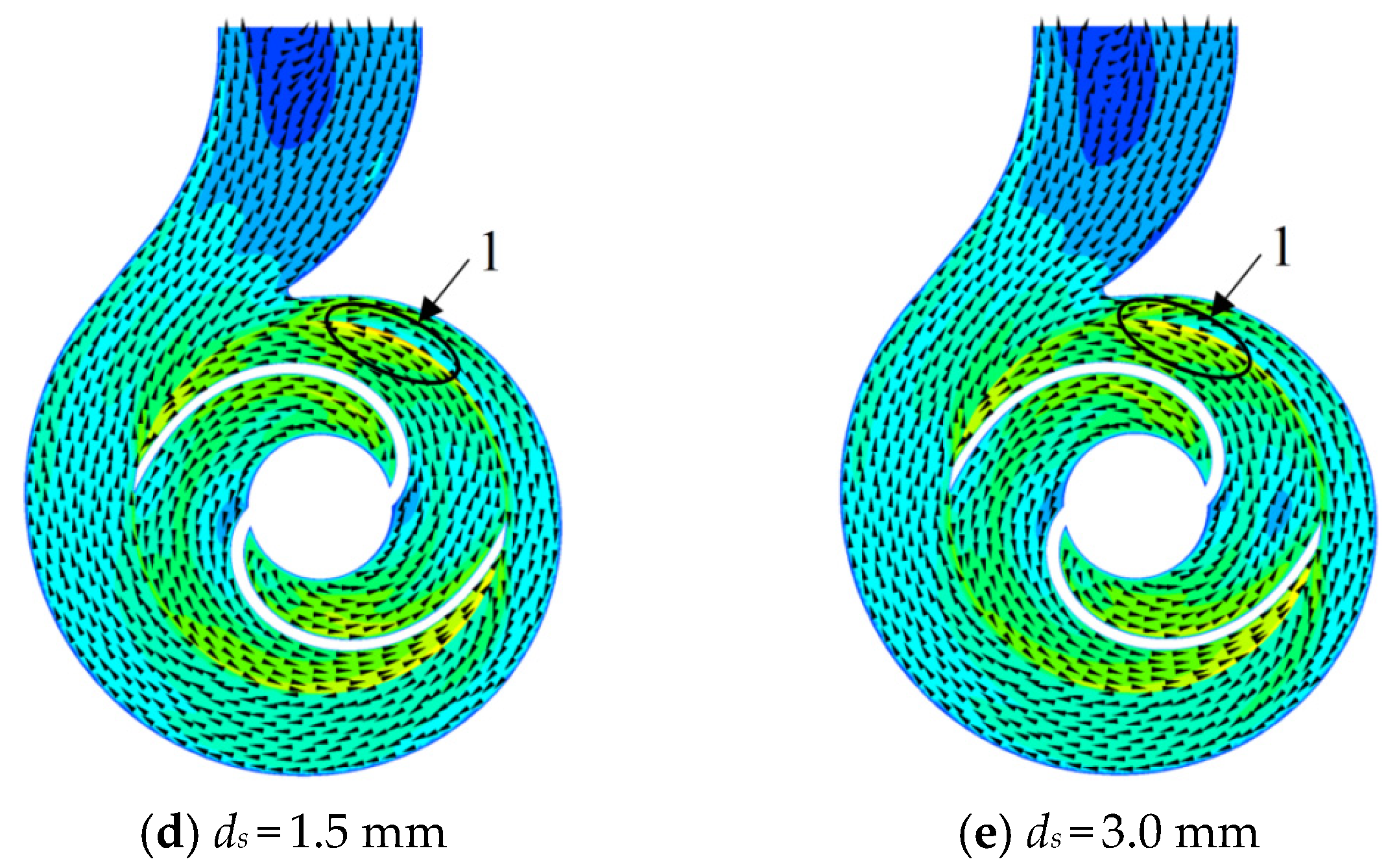

Figure 21 presents the velocity distribution in the volute mid-section of the sewage pump under the 1.0

Qd flow rate, encompassing both the clear water condition and scenarios with solid particles of diameters (

ds) 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm, and 3.0 mm. As illustrated in the figure, when the sewage pump conveys particle-laden fluid, the inherent high-velocity zone at the impeller outlet (Zone 1) undergoes a gradual contraction with increasing particle size, accompanied by a corresponding reduction in flow velocity. Large particles, due to their substantial inertia, struggle to fully synchronize with the water flow, thereby inducing a velocity differential relative to the liquid phase. This phenomenon intensifies inter-particle collisions and escalates the dissipation of fluid energy. Concurrently, the movement of large particles tends to generate localized flow retardation effects, culminating in a decrease in the overall kinetic energy of the fluid. Such dynamics may potentially exacerbate the wear risk in the impeller outlet region during practical operation.

Figure 22 illustrates the solid-phase distribution in the volute mid-section of the sewage pump under the clear-water condition and under particle diameter (

ds) conditions of 0.5 mm, 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm, and 3.0 mm at a flow rate of 1.0

Qd. It can be observed that solid particles are primarily concentrated within the impeller flow passages, whereas in the volute they are predominantly deposited along the inner wall. As the particle diameter increases, the high-concentration particle region in Zone 1 becomes increasingly prominent. This trend implies that coarser particles, possessing higher inertia, are less responsive to the fluid drag force. Consequently, they are more strongly subjected to centrifugal separation and tend to accumulate along the wall. Moreover, the particle volume fraction in the vicinity of the volute tongue near the outlet shows a noticeable increase. This local accumulation is largely attributed to the direct impingement of high-inertia particles on the tongue structure, as they fail to follow the sharp curvature of the streamlines in this region.

4.6. Internal Flow Field Analysis Under Different Solid-Phase Volume Fractions

To investigate the effect of varying solid-phase volume fractions on the internal flow performance of a semi-open impeller sewage pump, numerical simulations were conducted at the design flow rate of 1.0Qd with a particle diameter of ds = 1.0 mm. The simulations were performed for solid-phase volume fractions (Cv) of 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20%, and the results were analyzed accordingly.

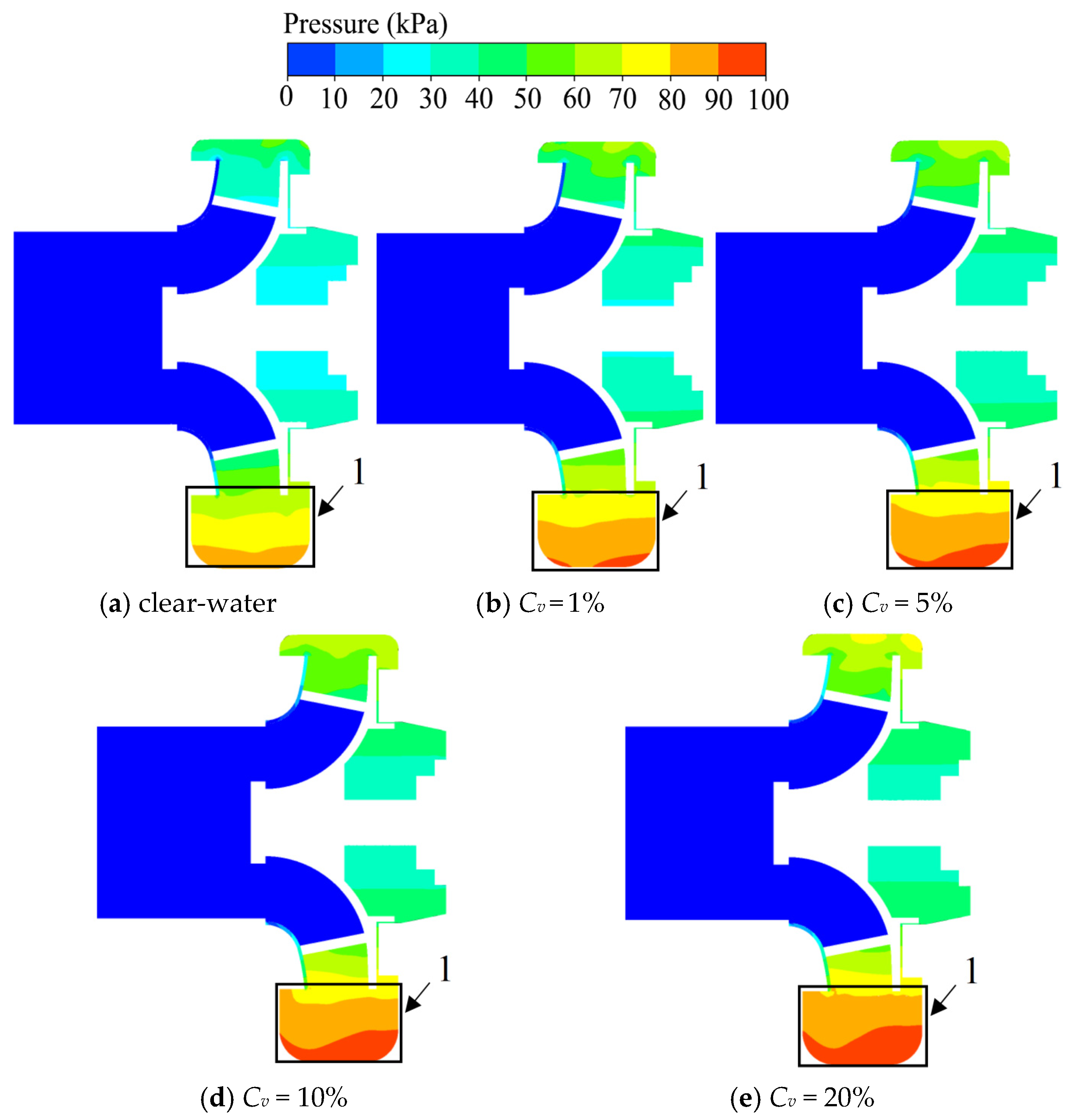

Figure 23 presents the pressure contour plots of the radial mid-section of the sewage pump under both the clear-water condition and with solid-phase volume fractions (

Cv) of 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% at a flow rate of 1.0

Qd. As depicted in the figure, the fluid enters the rotating impeller acceleration zone through the inlet (Zone 1), where pressure data indicate the formation of a dynamic pressure gradient, which increases along the impeller’s rotational direction due to the mechanical work performed by the impeller. A global pressure peak is observed in the volute diffuser section, and the pressure level in the rear cavity is generally higher than that in the front cavity, which is a result of the asymmetric structure of the semi-open impeller. As shown in

Figure 23d,e, the pressure gradient becomes more pronounced at higher solid-phase volume fractions. This intensification can be attributed to increased flow resistance and momentum transfer losses. With a higher concentration of solids, the continuous phase must expend more pressure energy to accelerate and transport the discrete particles, resulting in a steeper pressure distribution. Furthermore, as seen in

Figure 23a–e, under solid–liquid two-phase flow conditions, the static pressure gradient within the volute flow passage intensifies with increasing solid-phase concentration. This indicates that as the solid-phase volume fraction increases, the energy gradient difference between the impeller’s rotating domain and the stationary domain of the pump chamber becomes more pronounced.

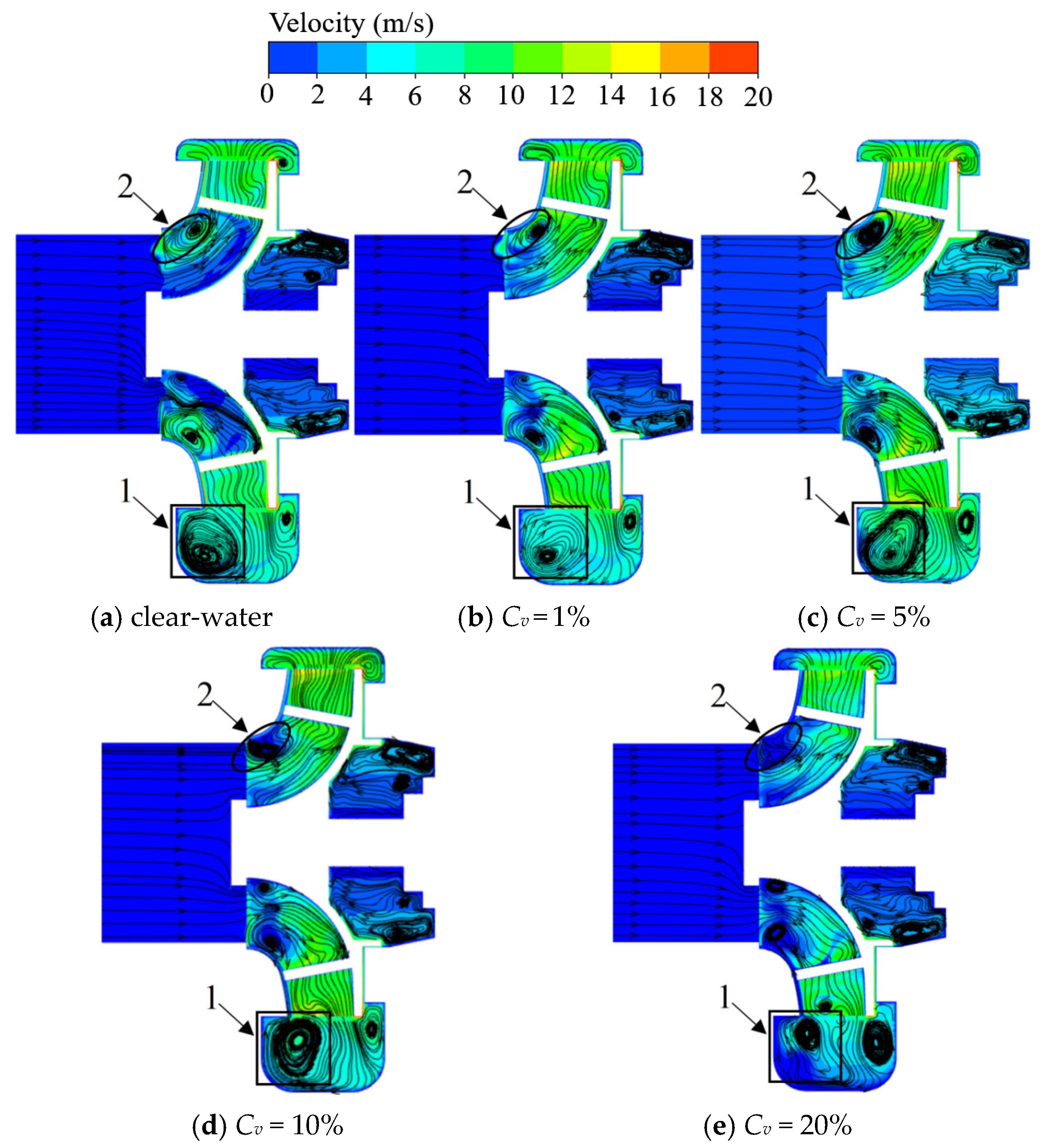

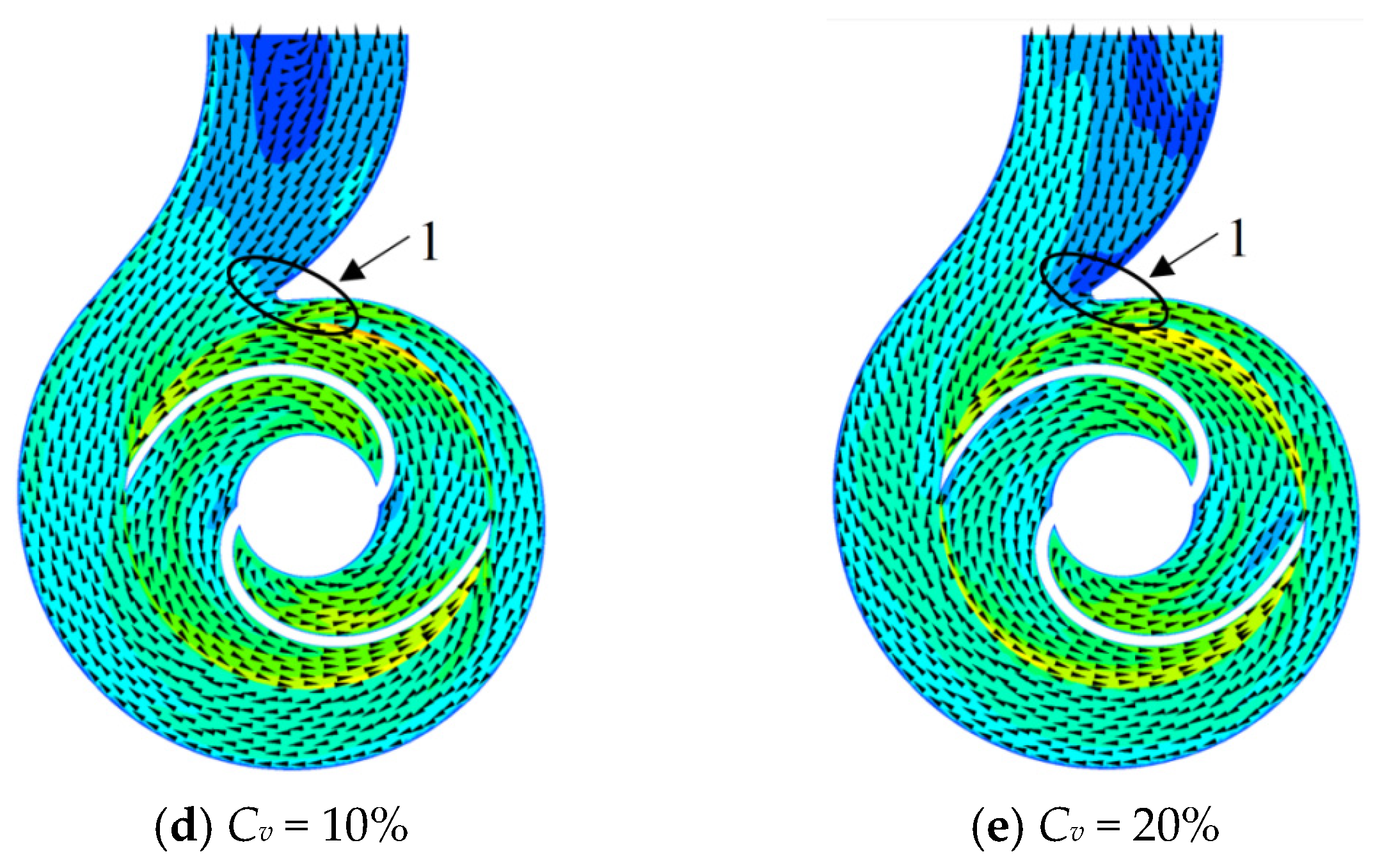

Figure 24 shows the velocity contour plots of the radial mid-section of the sewage pump under the clear-water condition and under solid-phase volume fractions (

Cv) of 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% at a flow rate of 1.0

Qd. As illustrated in the figure, backflow phenomena of varying degrees occur in the impeller inlet, volute flow passage, and rear cavity regions. Among these, the volute flow passage exhibits the most pronounced backflow, influenced by the high-velocity flow at the impeller outlet, with a relatively large vortex region (Zone 1) being generated. As shown in

Figure 24b–e, the increase in solid-phase volume fraction leads to a rise in the viscosity of the fluid medium, a reduction in the efficiency of mechanical energy conversion by the impeller, and an intensification of dynamic-static interference effects. Physically, the high concentration of particles consumes a significant amount of fluid kinetic energy through drag work. This momentum loss makes the fluid more susceptible to flow separation, thereby enlarging the vortex regions. Notably, under low-concentration conditions (1% and 5%), the overall velocity gradient distribution is relatively smooth; however, in the impeller shroud region (Zone 2), a greater degree of backflow is observed.

Figure 25 presents the solid-phase distribution in the radial mid-section of the sewage pump under the clear-water condition and under solid-phase volume fractions (

Cv) of 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% at a flow rate of 1.0

Qd. As shown in

Figure 25b, when the volume fraction is 5%, the solid phase is mainly concentrated at the impeller inlet (Zone 1) and along the inner wall of the volute (Zone 2). The particle distribution characteristics indicate that, at relatively low solid-phase volume fractions, solids tend to accumulate in certain critical regions of the flow field. A further examination of

Figure 25b–d reveals that, with a gradual increase in solid-phase volume fraction, the frequency of inter-particle collisions and interphase momentum exchange intensifies, directly resulting in a reduction in fluid kinetic energy. This is manifested as an incremental increase in the distribution of solids within both the impeller and the volute. Notably, in the volute (Zone 2), this increasing trend is more pronounced. This is primarily attributed to the strong centrifugal force which drives the high-inertia particles towards the wall, combined with the crowding effect caused by the high local concentration, leading to significant accumulation near the boundaries.

Figure 26 shows the pressure distribution in the volute mid-section of the sewage pump under the clear-water condition and under solid-phase volume fractions (

Cv) of 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% at a flow rate of 1.0

Qd. As illustrated in the figure, the overall pressure distribution trend within the volute flow passage is similar under both clear-water and solid–liquid two-phase flow conditions. However, with increasing particle volume fraction, the pressure within the flow passage exhibits a gradual upward trend. This variation is primarily attributed to the increase in the effective density of the solid–liquid mixture and the intensified inter-particle collisions. As the particle volume fraction increases, the frequent collisions among particles and the interphase drag significantly enhance the flow resistance. Physically, the fluid transfers more pressure energy to the particles to overcome the inertia of the dense solid phase. Consequently, the static pressure distribution is readjusted to balance the increased momentum exchange, resulting in a gradual increase in the overall pressure level.

Figure 27 illustrates the velocity distribution in the volute mid-section of the sewage pump under the clear-water condition and at solid-phase volume fractions (

Cv) of 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% at a flow rate of 1.0

Qd. As shown in the figure, during the impeller’s rotation, the radial velocity of the fluid increases, and the velocity field distribution across different solid-phase volume fractions follows a similar evolutionary trend. In

Figure 27a, the velocity distribution shows that, under the clear-water condition, a “low-velocity zone” has already formed in the volute tongue region (Zone 1). As the solid-phase volume fraction increases, the extent of this low-velocity zone expands significantly. This phenomenon can be attributed to two main factors: first, the increase in fluid medium viscosity caused by higher solid-phase concentrations intensifies the flow separation effect at the volute tongue; second, the higher particle content increases frictional interactions between the solid phase and the volute wall, resulting in greater dissipation of fluid energy. The combined effect of these two factors leads to the observed enlargement of the low-velocity zone in the tongue region. This behavior highlights the impact of solid-phase concentration on the flow dynamics within the volute, which contributes to reduced flow efficiency and potentially increased wear and erosion in these regions.

Figure 28 presents the solid-phase distribution in the volute mid-section of the sewage pump under the clear-water condition and under solid-phase volume fractions (

Cv) of 1%, 5%, 10%, and 20% at a flow rate of 1.0

Qd. As shown in the figure, solid particles are predominantly concentrated within the volute flow passage. From

Figure 28a–d, it can be observed that the solid particle concentration near the volute outlet increases with the rise in volume fraction. This is attributed to the relatively lower flow velocity at the volute outlet. Due to their higher inertia, particles cannot follow the fluid streamlines and are driven towards the outer wall by centrifugal force, leading to accumulation. Furthermore, under high-volume-fraction conditions, as illustrated in

Figure 28d, the solid-phase distribution within the impeller flow passages increases noticeably. This is primarily because the high concentration leads to increased particle-particle interaction. These interactions, combined with the momentum transfer to the fluid, hinder the effective transport of particles, resulting in a more pronounced accumulation within the impeller passages.

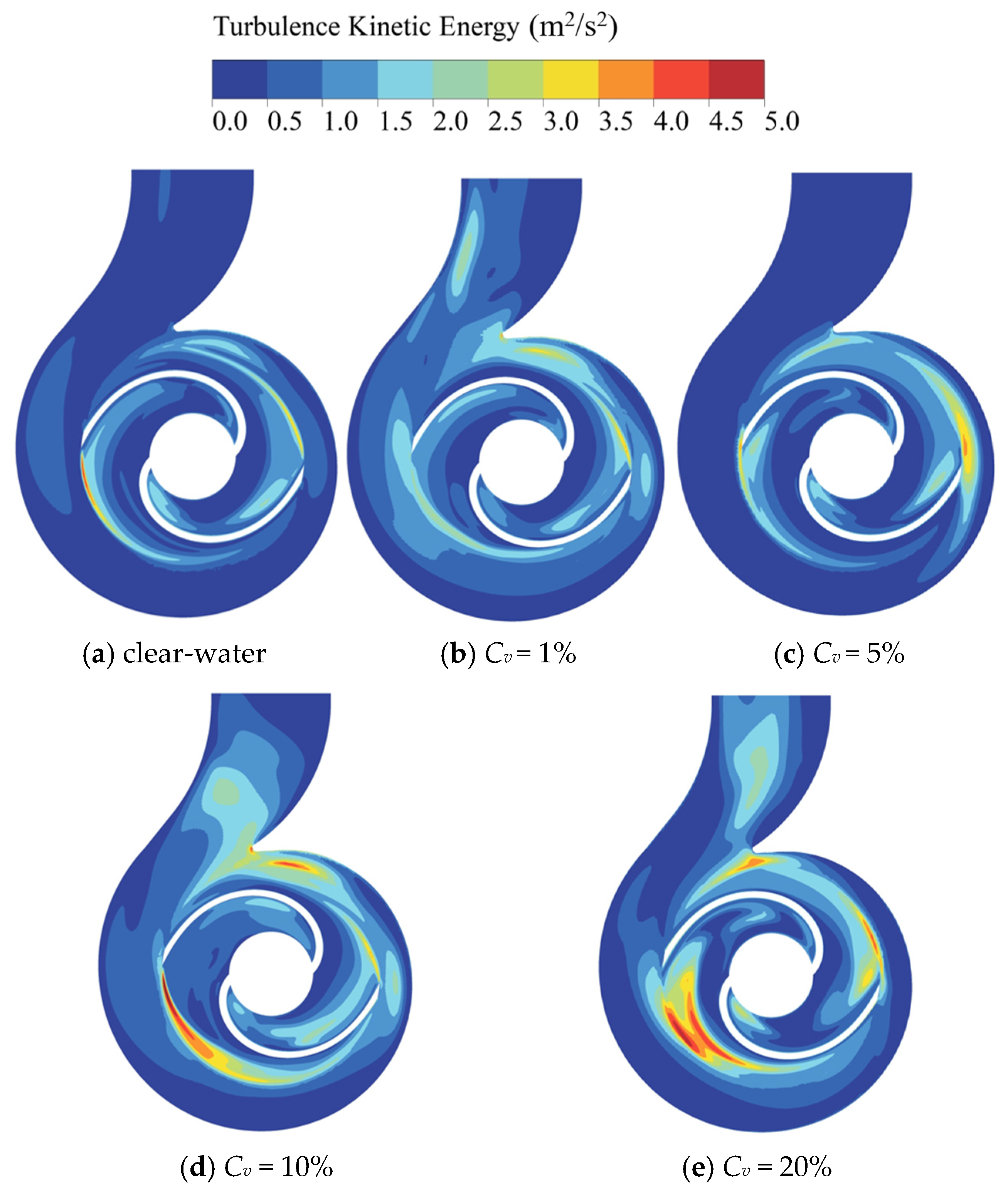

Figure 29 displays the turbulence kinetic energy (TKE) distribution contours in the volute at the design flow rate under clear-water conditions and varying solid volume fractions (

Cv ranging from 1% to 20%). It is evident that under clear-water and low-concentration conditions, the overall flow field is predominantly characterized by blue regions, indicating low turbulence intensity. High TKE regions are confined to small areas near the blade trailing edges and the tip of the volute tongue, suggesting a relatively stable flow state.

However, as the solid volume fraction increases, the flow field structure undergoes significant changes. Particularly when the volume fraction rises to 10% and 20%, TKE intensity at the impeller outlet and the volute tongue region shows explosive growth, with red high-value zones expanding significantly towards the volute diffuser section. This increase in turbulence is primarily due to the fact that, as the concentration of particles rises, the 1.0 mm particles passing through the narrow volute tongue region struggle to follow the fluid streamlines due to their inertia. This results in a higher frequency of particle-wall collisions, leading to localized flow separation. The intense turbulence generated by the solid phase causes a substantial amount of fluid kinetic energy to be dissipated, rather than being converted into pressure energy. This explains, on a microscopic level, the significant decline in macroscopic hydraulic efficiency as solid concentration increases.

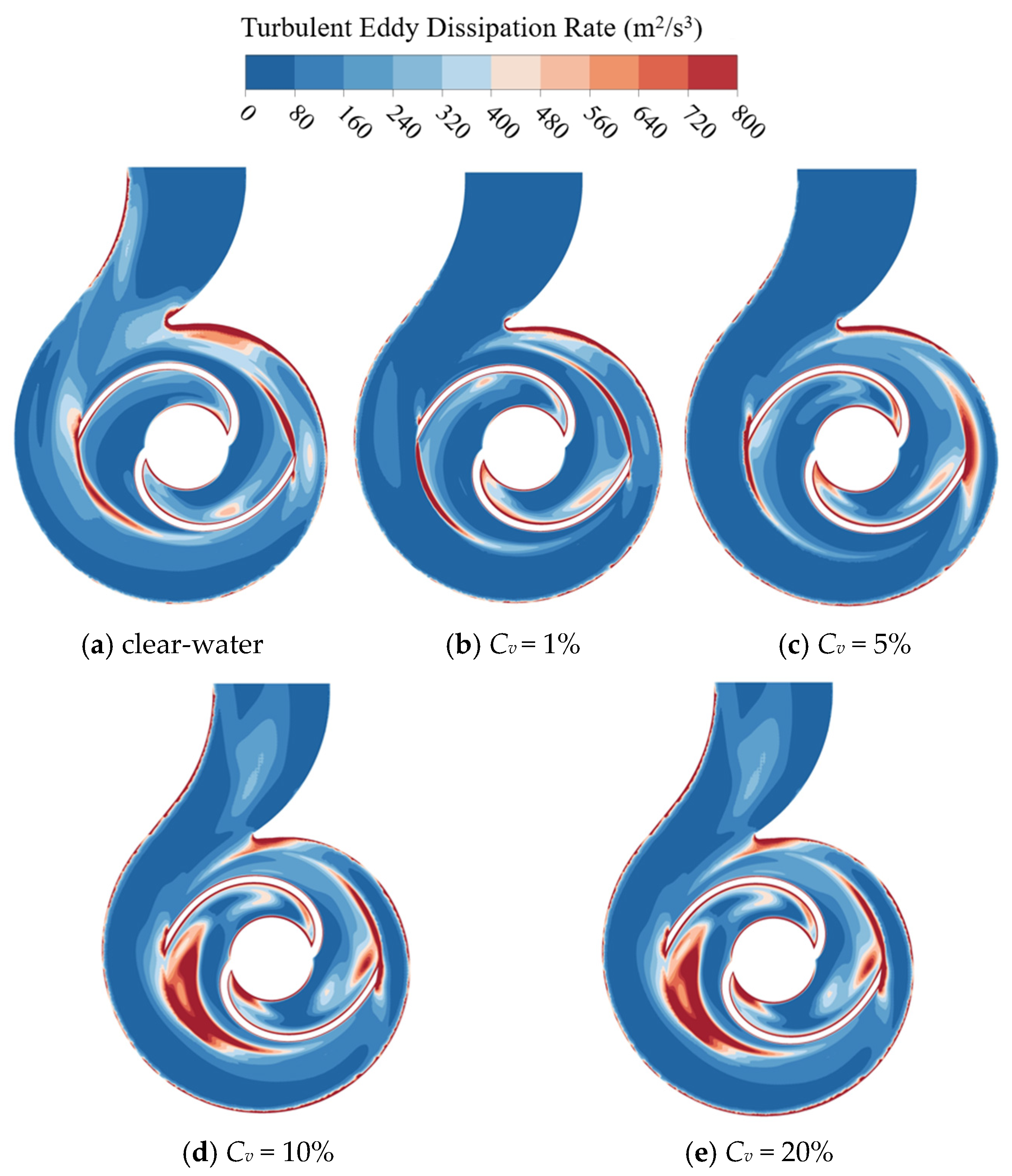

Figure 30 presents the distribution of the Turbulent Eddy Dissipation Rate in the volute under clear water and different solid concentrations. This indicator intuitively reflects the rate of fluid energy loss. By observing the contours, it is evident that under clear water and low-concentration conditions (1% and 5%), the red regions representing high energy consumption are relatively small and strictly confined to the blade trailing edges and the tip of the volute tongue. However, when the concentration rises to 10% and 20%, the high-dissipation regions near the impeller outlet and the volute tongue expand significantly towards the surroundings, accompanied by a marked increase in numerical values. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the disturbance effect of particles on the fluid. As the concentration increases, dense particle clusters flowing out of the impeller possess high inertia and cannot pass through the volute tongue as smoothly as the liquid phase. Instead, they frequently impact the walls and agitate the surrounding fluid. Such continuous collisions and intense friction dissipate a substantial amount of kinetic energy, causing energy that should have been converted into pressure to be ineffectively consumed. This directly leads to the degradation of fluid transport efficiency under high-concentration conditions.