1. Introduction

Coastal erosion represents one of the most critical challenges to global infrastructure and land resources. Coastal zones host a significant concentration of the world’s major cities and essential economic assets, including ports, energy infrastructure, and agricultural land. On a global scale, between 1984 and 2015, the loss of permanent land in coastal areas amounts to almost 28,000 km

2 [

1]. Twenty-four percent of the world’s sandy beaches are eroding at rates exceeding 0.5 m/y, and about 7% of the beaches experience erosion rates that can be classified as severe with rates up to 5 m/y. Furthermore, erosion rates exceed 5 m/y along 4% of the sandy shoreline and are greater than 10 m/y for 2% of the global sandy shoreline [

2]. This degradation is propelled by the interplay of anthropogenic pressures, such as inadequate land use and disruptive coastal engineering, and natural factors, including climate-change-driven hydrometeorological shifts and inherent geological susceptibility.

Due to climate change, coastal process is most active in arctic regions, especially because of the sea ice decrease. There, a documented decline in sea ice extent and thickness [

3,

4,

5] has lengthened the open-water season [

6], a change hypothesized to increase the physical vulnerability of Arctic coasts by intensifying wave action and storm surges, thereby enhancing erosion, flooding, and infrastructure damage. The coastal response to declining sea ice is non-linear and spatially variable [

7]. An analysis of Arctic Coastal Dynamics data covering 25% of the Arctic coastline found that a clear increase in erosion rates linked to a lengthening ice-free period was evident at only one site in the eastern Laptev Sea [

8]. In contrast, other key sites, such as Marre-Sale in the Kara Sea, the Bykovsky Peninsula in the Laptev Sea, and locations in Alaska and the Beaufort Sea, exhibit significant spatial variability driven by local storm climate, lithology, and geomorphology [

9].

The implications of this complex framework extend beyond the Arctic. Changes in ice conditions also play a great role, comparable with that of changes in storminess, in the intensity of coastal processes in the Baltic Sea area. Ice-free conditions increased significant wave heights on the order of about 0.3 m for both mean values and 99th percentile values [

10]. Research at the eastern Gulf of Finland [

11] showed that the most extreme erosion events are controlled by a specific simultaneous combination of hydrometeorological factors: (i) long-lasting western or south-western storms, (ii) high water level (more than 2 m above the mean level), and, most importantly, (iii) absence of stable sea ice during such events. The decrease in sea ice in the Baltic Sea leads to reduced resilience of sandy beaches, as ice barriers formed during winters used to protect them from many winter storms [

12].

The shallow, seasonally freezing Sea of Azov is highly susceptible to hazardous exogenous processes, primarily coastal erosion and landslides [

13]. Its shores are inherently vulnerable due to easily erodible strata, such as clays and loams, a deficit of beach-forming material, and often steep cliffs with narrow or absent beaches. These inherent risks are exacerbated by frequent severe storms, high-magnitude storm surges, and the dynamic action of mobile ice. Crucially, the Sea of Azov is undergoing a well-documented hydrometeorological regime shift characterized by rising winter temperatures, rapidly diminishing ice cover, and an increase in storm and surge activity during the extended ice-free season.

Despite this clear vulnerability and ongoing environmental change, a comprehensive, process-based understanding of erosion drivers in the Sea of Azov is lacking. Field observation programs have been historically sporadic, conducted irregularly since 1950th, and, consequently, analyses often generalize across large areas, masking critical local drivers. As a result of previous studies [

14,

15], a relationship was established between the intensity of erosion of the shores of the Sea of Azov and extreme storm surges. But sea ice as a factor in coastal erosion has not been studied.

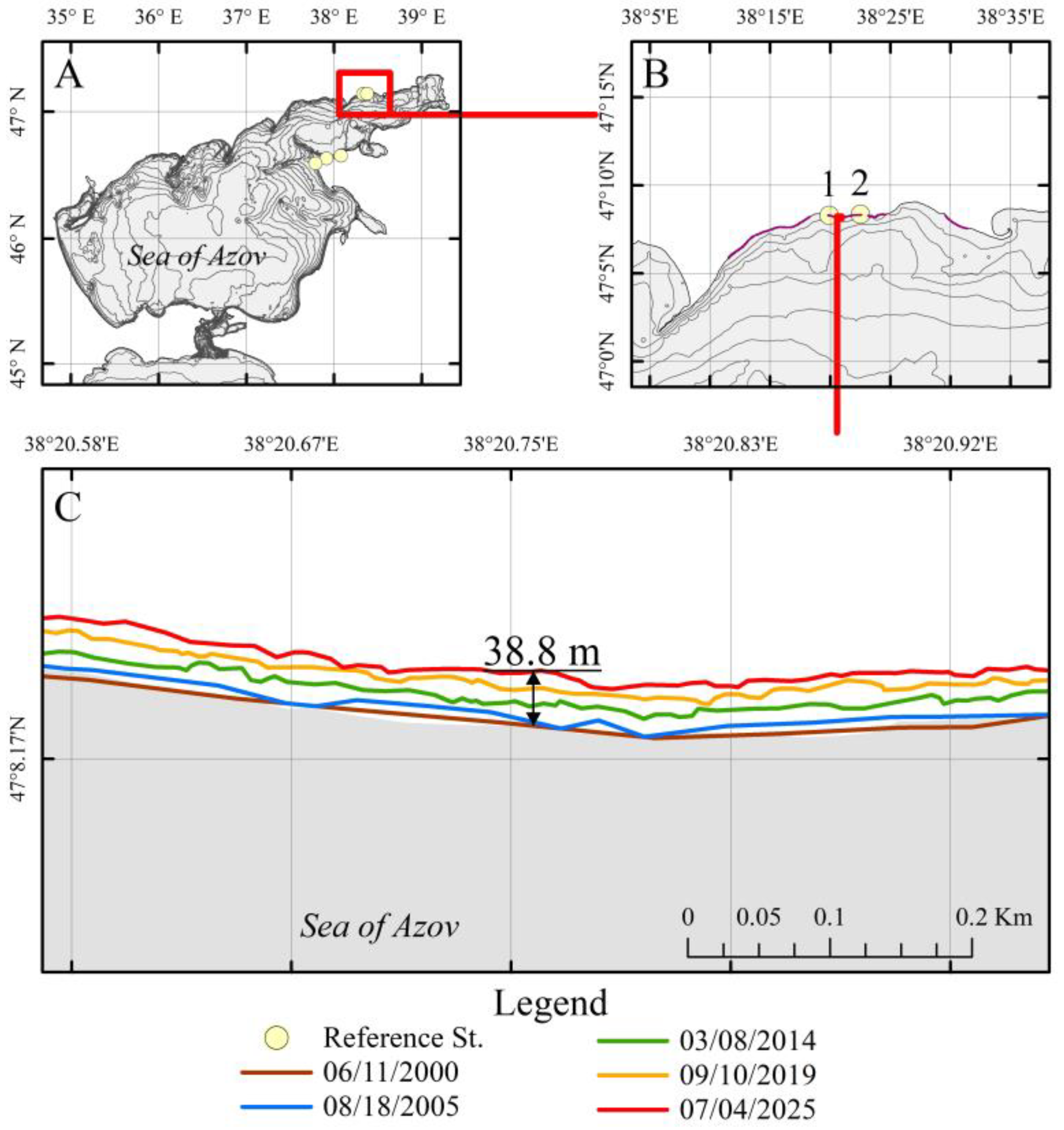

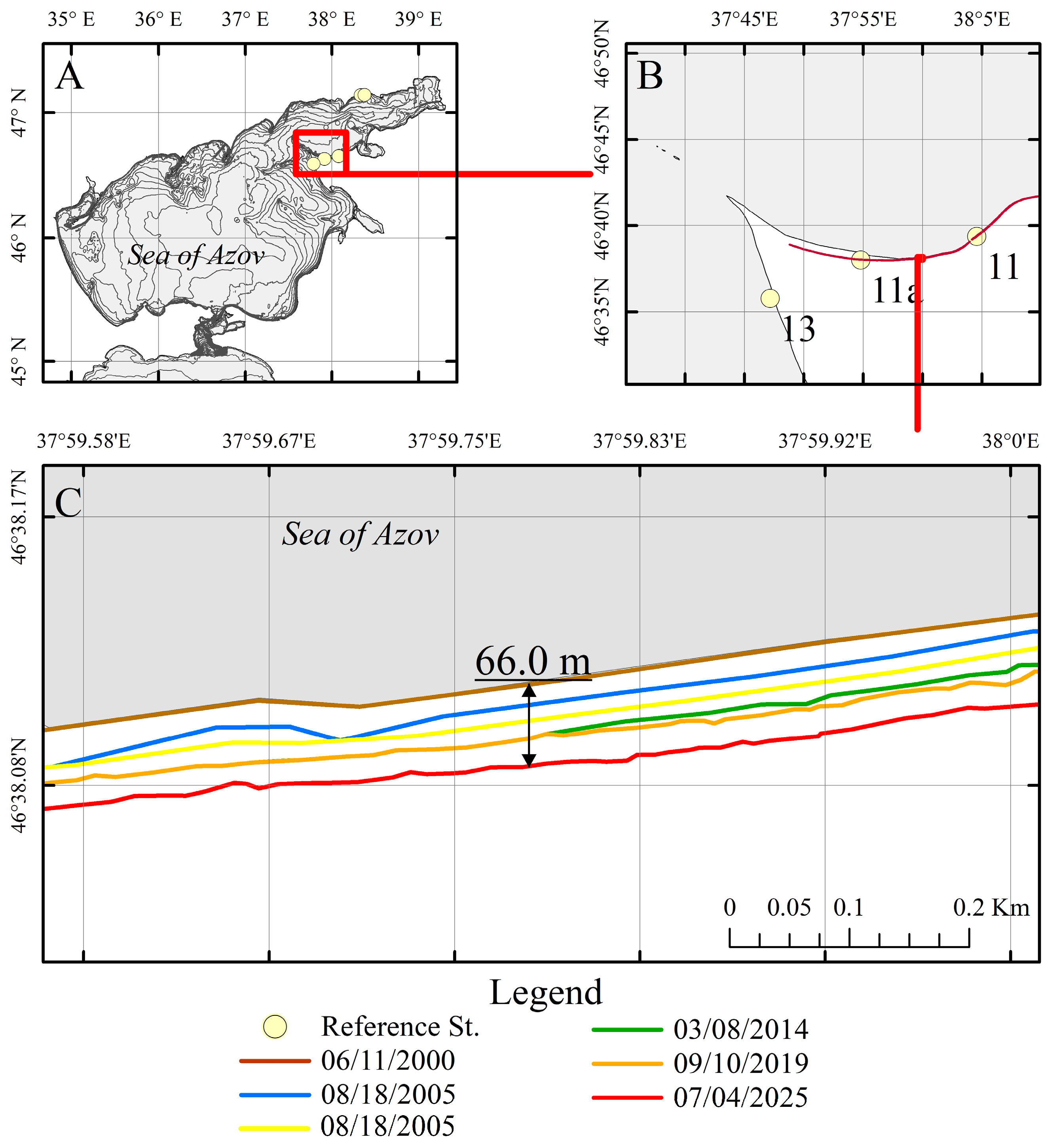

To address this gap, we focus on two key sites with the fastest recorded erosion rates: a Northern Site in the Taganrog Bay and a Southern Site at the boundary between the bay and the open sea (

Figure 1). Abrasive bedrock coastal cliffs are considered, which are eroded during waves and surging sea levels. During the action of these phenomena, the base of the cliff is eroded, forming wave-cut niches, as a result of which the upper layers slump under the influence of waves and gravity. It was the combination of loose, low-stability Neogene-Quaternary sediments in the coastal cliffs and the effects of hydrodynamic factors that predetermined the high rates of erosion.

The concept of coast erosion has received wide coverage in the scientific literature devoted to the study of erosion processes on the coast of the Sea of Azov. Specialized publications [

16,

17] analyze in detail the mechanisms and dynamics of erosion, which makes it possible to apply the knowledge gained to this study.

Also, these two sites were selected because they possess the most complete observational record, derived from both expeditionary research and satellite imagery. While both share an abrasive cliff structure, they differ fundamentally in their shoreline configuration relative to dominant storm waves and surge, as well as in their exposure to ice cover. This comparative approach allows us to isolate the influence of specific hydrometeorological factors, including wind waves, dynamic shore load, ice conditions, and storm surges, on erosion intensity using data spanning 2000 to 2025.

Thus, the central aim of this study is to move beyond regional description and identify the definitive local and event-scale factors that govern coastal retreat in the Sea of Azov. This focused investigation is necessitated by the need to pinpoint key drivers that are obscured in broader-scale analyses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Erosion

Most of the coastal zone of the Sea of Azov, excluding the accumulative formations of spit, deltas of small watercourses and the Kuban River, as well as the accumulative territories adjacent to them, is a steep and rectilinear coast. The height of the bedrock shore varies from several meters, typical for small river valleys, to 25–30 m, and on the coast of the Kerch Peninsula it reaches 40–50 m. The angle of inclination of the slopes, as a rule, ranges from 60 to 90 degrees, which significantly increases their susceptibility to erosion processes caused by wave and gravitational effects. The cliff is usually accompanied by a narrow strip of beach 2–10 m wide, and in some cases there may be no beach at all. In areas adjacent to accumulative formations, spits, and river valley outlets, beaches expand to 20–60 m.

The geological structure of the bedrock coast cliffs of the Sea of Azov is characterized by the extensive development of Neogene-Quaternary deposits, which form the basis of the geological structure of the shores. Friable sedimentary rocks are predominant, among which loess-like loams belonging to the Lower-Upper Pleistocene age are the most common. These deposits often form a significant part of the high-altitude profile of the cliff, extending from 3 to 5 to 20–30 m. At the base of the geological section, more ancient formations are often exposed, such as Scythian clays, alluvial sands and Middle Sarmatian limestones, which, as a rule, are confined to the most elevated areas of the coast, reaching heights from 25 to 40 m.

Tectonic movements affect coastal processes, topography, sediment distribution, and slope processes. The degree of influence depends on the direction, intensity and contrast of the movements. However, the authors did not consider the processes of interaction between tectonic plates, since the average rate of coastal sinking is only 2–2.5 mm per year. In a short period of time (in a geological context) this effect is insignificant compared to active effects, such as storm surges, the height of which reaches 3 m. These phenomena play a more significant role in the rate of retreat of the bedrock shores.

An analysis of previous studies has revealed that abrasive processes are a significant source of detrital material entering the coastal zone. However, due to the dominance of fine-grained sedimentary rocks in coastal sediments, a significant part of this material undergoes sedimentation in deep-water zones. As a result, coastal streams receive a relatively small amount of coarse-grained material, which significantly affects the morphology and dynamics of coastal systems [

12].

In this study, abrasive bedrock coastal cliffs are considered, which are eroded during waves and surging sea levels. During the action of these phenomena, the base of the cliff is eroded, forming wave-surf niches, as a result of which the upper layers slump under the influence of waves and gravity. It was the combination of loose, low-stability Neogene-Quaternary sediments in the coastal cliffs and the effects of hydrodynamic factors that predetermined the high rates of erosion.

Coastal erosion rates were quantified using a multi-source dataset that integrated field measurements, archival data, and remote sensing.

Archival data from previous studies, notably those reported by Bespalova et al. (2023) [

13] from 1980 to 2020.

Systematic monitoring of coastal erosion in the Sea of Azov, which was conducted by the authors from 2020 to 2025, with observations usually carried out annually or every two years with some interruptions. It is worth noting that, like archival data, our field observations consisted of long-term surveys of the coastal zone and included instrumental measurements of distances and rates of retreat of the edge of the bedrock coastal cliff at reference stationary points established on the coast.

The data of satellite remote sensing, optical range in panchromatic mode from Corona satellite programs with a resolution of 8 m, Spot 1–5 (5–10 m), Resource-P (1 m), Sentinel 2 (10 m) were used. The data covered the period from 1979 to 2025 and underwent radiometric and geometric correction procedures, with geographic reference based on reference points. Then, in each image, the position of the edge of the coastal cliff was digitized on a scale 1:500, 1:000, 1:2000 and all the errors introduced during the binding and digitization of the edge lines have been calculated. Considering that the study used the line of the edge of the bedrock coast cliff, which is located at altitudes from 3 to 45 m, unlike monitoring the coastline, this made it possible to ignore the data binding to the time of high tide or low tide. At the next stage, using the tool “Digital Shoreline analysis system (DSAS)” v.5.0 [

18,

19] to calculate the change in the coastline (or its position in time), a spatio-temporal dynamics analysis was performed with a 10 m pitch plan.

Our field campaigns from 2024 to 2025 significantly enhanced in situ measurements by establishing the first regular, intra-annual measurement program, which included critical winter surveys along the sea’s northern and eastern coasts.

Generally, the study includes data time series from 1980 to 2025. In the present work we used the most augmented and validated data time series from 2000 to 2025, which combines in situ measurements and data from satellite images, enabling comprehensive coverage of hard-to-reach areas and filling temporal gaps in the field measurements.

2.2. Wind Wave Modeling

For a retrospective analysis of wind waves in the Sea of Azov, the Simulating Waves Nearshore (SWAN) mathematical model, version 41.51, was used to obtain realistic parameters for a given wind, bathymetry, and current conditions in shallow waters, such as those found in coastal regions, lakes, and estuaries. The model was developed at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Earth Sciences of Delft Technical University, the Netherlands. The model has been described in [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. This model has been used to calculate waves occurring among the seas, and it has been widely used with reliable results for both deep-water and shallow, closed-water areas.

The model bathymetry was defined by a proprietary high-precision digital elevation model with spatial resolution of 0.01 × 0.01 degree [

25]. As previously demonstrated, this setup reliably reproduces wave parameters for the shallow Sea of Azov [

25,

26].

The model was forced with wind fields from the ERA5 global reanalysis produced by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) [

27]. The zonal and meridional wind components from ERA5, which have a temporal resolution of 1 h and a spatial resolution of 0.25°, were used directly without preliminary interpolation to the computational grid in order to avoid the accumulation of errors during recalculations.

The simulation covered the period from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2024 with a 30 min time step. The model domain encompassed the entire Sea of Azov and the northern part of the Black Sea to ensure a stable liquid boundary condition in the Kerch Strait and to minimize potential errors in wave propagation. The model performs calculations independently and is not linked to hydrodynamic models.

The following key physical processes were activated in the SWAN configuration. The shape of the spectra (both in frequency and direction) at the boundary of the computational grid was defined by the Jonswap spectrum. SWAN ran in third-generation mode for wind input, quadruplet interactions and whitecapping with linear growth based on Cavaleri and Malanotte-Rizzoli (1981) [

28]. Whitecapping according to Komen et al. (1984) [

29] was applied. Quadruplets based on Hasselmann et al. (1985) [

30]. Dissipation by bottom friction based on the semi-empirical expression derived from the JONSWAP results for bottom friction dissipation [

31] was activated. The triad wave-wave interactions, turbulent viscosity and diffraction are included in the wave computation.

The SWAN model output provided the essential wave parameters for analysis, including significant wave height, mean wave period (derived from the zeroth and first negative moments of the variance density spectrum), mean wave direction and length, and swell parameters.

2.3. Dynamic Load on the Shoreline

The dynamic wave load on the shoreline, expressed as an impulse pressure in tonne-force per square meter (tf/m

2) from storm waves and surges, was calculated based on the methodology of [

32,

33] and the empirical relations given in [

34,

35], that take into account the change in the wave profile and its collapse on gentle slopes. The cited literature presents the basic sequences for calculating the dynamic load on the shore. Upon entering shallow water, nonlinear effects begin to arise in the wave due to bottom friction, leading to a transformation of the wave profile and direction. The wave steepness increases and reaches a maximum value at a critical depth, where wave breaking and energy release occur, accompanied by a large impact load on the shore. The depth at which instability begins to occur and the wave parameters at this depth are determined from the law of conservation of energy and empirical relationships accounting for the transformation of the wave profile on a gentle slope.

The governing equation is:

where

is the wave period at breaking;

is the wave height at critical depth;

is the wavelength at critical depth.

Critical depth—the depth at which a wave breaks.

The input parameters for Equation (1) were derived from two primary sources. The undeformed wave characteristics (significant wave height, mean period, and mean wavelength) were sourced from the nearest node to the shoreline in the SWAN model output, selected along the direction normal to the coast. High-resolution digital bathymetric models were used to define the nearshore profile, providing the bottom slopes, precise shoreline coordinates, and the directional normals to the coast required for the calculation.

2.4. Ice and Ice Pile-Up

Sea ice conditions were analyzed using operational ice charts for the Sea of Azov, obtained from the International Data Center—Sea Ice (IDC-SI) [

36]. These charts, provided in the standardized SIGRID vector format (an archival standard for georeferenced sea ice data), consist of shapefiles containing polygons that delineate areas of water and ice cover. The associated geospatial attributes specify key parameters, including ice concentration, age (a proxy for thickness), and form of floating ice.

From this dataset, we derived seasonal statistics, including the average, maximum, and minimum areal extent of total sea ice and fast ice, as well as the duration of the ice season. Data on ice thrusts and onshore ice pile-ups (ice shoves) were compiled from a synthesis of published literature, open-access online repositories, and satellite imagery [

26].

2.5. Wind Speed and Direction

To characterize the wind forcing on the coastal cliffs, wind speed and direction data for the period 2000–2024 were generated using the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model [

37]. The model was configured for the Azov-Black Sea region with a 10 km spatial resolution in a Lambert conformal conic projection [

38]. This data source was chosen because, compared to the ERA5 global reanalysis wind, it has a higher spatial resolution and quality [

38].

The model physics were represented by the following parameterization schemes: the Thompson scheme for microphysics [

39]; the Betts-Miller-Janjic scheme for cumulus convection [

40]; the RRTMG scheme for longwave and shortwave radiation [

41]; the Mellor-Yamada-Janjic (MYJ) scheme for the planetary boundary layer [

42]; the Unified Noah model for the land surface [

43]; and the Kain-Fritsch scheme for precipitation [

44]. The underlying surface was defined using MODIS data with a 5 min spatial resolution. The model time step was 60 s.

Initial and boundary conditions were derived from the ERA5 global reanalysis [

45]. The simulation was conducted in a continuous cycle, with each 30 h segment comprising a 6 h spin-up period (discarded) followed by a 24 h analysis period. Atmospheric data from the analysis periods were output hourly and concatenated to form a continuous, final dataset for analysis.

2.6. Data Processing Methods

For a detailed analysis, this study focuses on two specific areas, the Northern and Southern sites, which exhibit the fastest coastal erosion rates in the Sea of Azov. Because the initial data for the study were spatially heterogeneous, it was necessary to standardize them to a single spatial scale, taking into account the geomorphological characteristics of the coast. The analysis was conducted within a structured geospatial framework established in our previous research [

26,

46], which subdivided the sea into a grid of 442 cells, each 10 × 10 km. The cell resolution was selected after a series of experiments with averaging of values. Analysis showed that within a 10 × 10 km cell, the wave and dynamic impact on the coast in these areas has the smallest spread of values and is virtually uniform. Wind speed and direction were calculated using a 10 km grid, meaning no recalculation was required and no parameter averaging was performed. The area of ice floes in the Sea of Azov allows for the selection of a 10 km grid cell, or even larger ones if necessary.

From this grid, we selected a subset of cells encompassing the coastal zones of the two study areas, specifically 2 cells for the Northern site and 7 for the Southern site. For each of these coastal cells, a comprehensive dataset was compiled into a daily time-series matrix spanning the period 2000 to 2024. This matrix integrates key hydrometeorological variables, including coastal erosion rates, wind speed and direction, wave height and length, dynamic wave load, and the presence and characteristics of ice and ridged ice formations.

3. Results and Discussion

Our previous research [

47] has documented a significant regime shift in the Sea of Azov’s hydrometeorological system, which is confirmed in this work. A continuous rise in winter air temperatures since 1975 has increased the frequency of mild winters. This warming has driven a pronounced decline in sea ice extent since the early 1990s, accompanied by a shift in ice phenology, with formation occurring later and break-up earlier by 5 to 7 days per decade since the 1980s. Fast ice, which serves as a protective barrier against storms and surges [

48], has undergone a severe decline in both spatial extent and seasonal duration, with complete absence observed in recent years. The role of ice pile-up events on coast is dual in nature. While they can inflict damage by scouring and eroding the cliff base during thaw or through the direct force of ice surges, they can also provide a temporary buffer, protecting the coast from wave action in late winter and early spring.

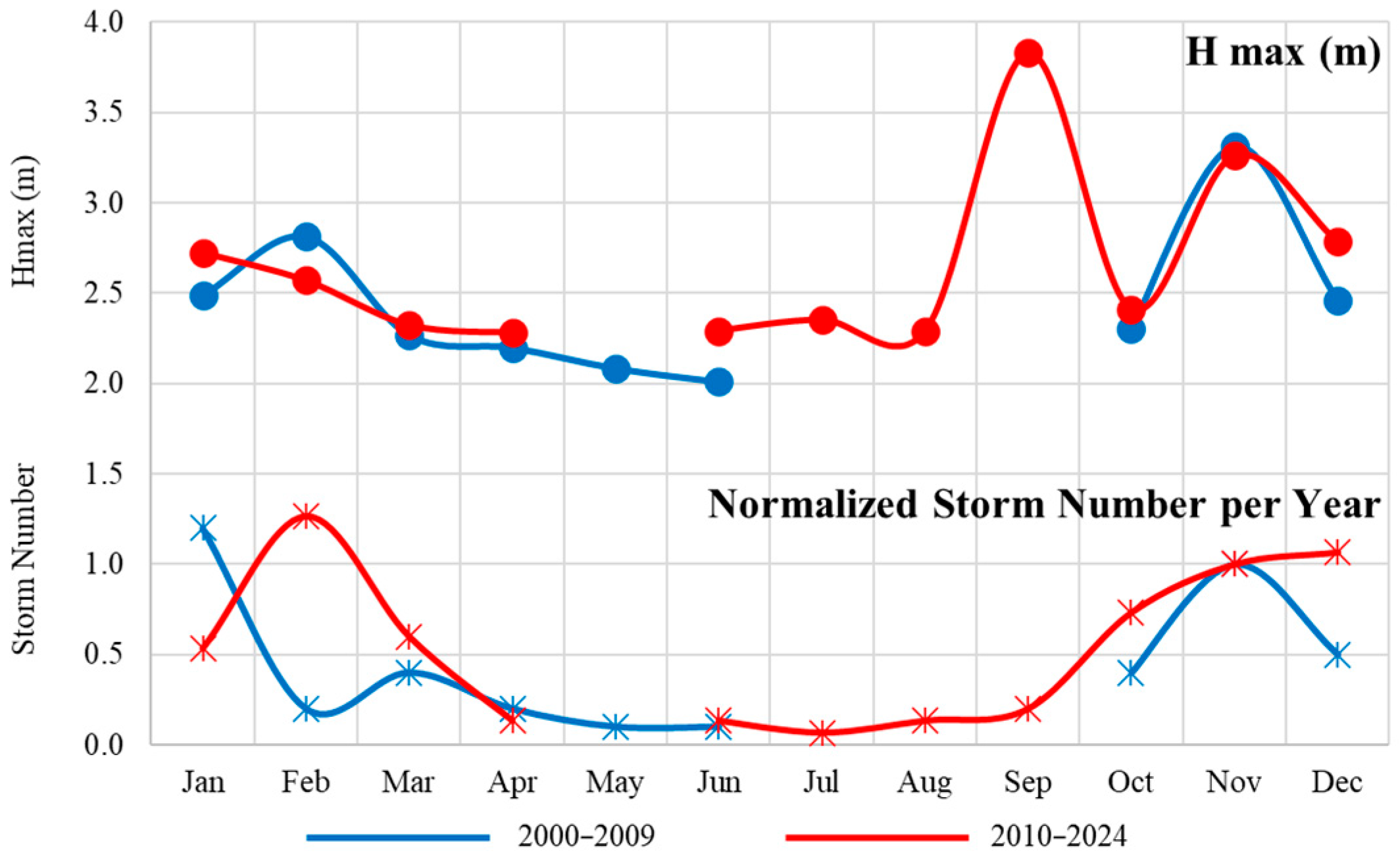

Furthermore, the wave and storm climate has been transformed: since 2000, significant wave height has increased even as storm frequency and duration have decreased, while the occurrence of storm surges has risen. Notably, although the traditional storm season spans November to March, a marked increase in extreme surge-producing storms during the warm, ice-free period has been observed since the 2010s [

25]. The ongoing transformation of the Sea of Azov’s hydrometeorological regime is fundamentally reshaping the dynamic forces acting on its coastal zone.

Analysis of the entire study period reveals distinct long-term erosion rates for the two sites. The average annual for the period 2000–2025 erosion rate at the Northern Site ranged from 1.1 to 1.6 m/year. In contrast, the Southern Site exhibited slightly higher, yet still comparable, long-term rates, ranging from 1.5 to 1.8 m/year. The most significant erosion event for both sites occurred in 2014, with annual retreat rates peaking at 6 m. This extreme erosion was driven by a major storm on 24–25 September, one of the most severe in the last century. The event featured westerly winds reaching speeds of 30 m/s, generating waves up to 3.8 m high in the open sea (1.0 m in the Taganrog Bay). The associated maximum wavelength and period were 54.4 m and 7.3 s, respectively. The total duration of this storm, defined by a significant wave height exceeding 2.0 m, was 30 h. The geomorphic impact was substantial: the northern coast retreated by 5.6 to 6.2 m, while the southern coast retreated by 4.0 to 5.2 m in that single year. Outside of this exceptional event, the inter-annual erosion patterns at the two sites are largely asynchronous.

A central finding of our study is the absence of a direct correlation between coastal erosion rates and large-scale hydrometeorological parameters in the Sea of Azov. This result aligns with observations from the Arctic region, where similarly complex and non-linear coastal dynamics are documented [

9]. The paper [

49] shows that there is no relationship between wave climate and coastal erosion on the south-eastern coast of Sicily, and concludes that the main cause of coastal erosion is land use change. The interaction between the coastal zone and forcing factors, such as wave energy, storm surges, and ice dynamics, constitutes a complex, often metachronous process where cause and effect can be separated by a considerable temporal lag. This underscores the critical importance of identifying the key, site-specific geomorphic and hydrodynamic controls that govern the development of hazardous processes at a local scale. Based on the analysis of hydrometeorological information and long-term observation data on the dynamics of the coastal zone, in this work the study period 2000–2025 is divided into two sub-periods—2000–2009 and 2010–2025. We suppose that, depending on changes in the hydrometeorological regime, key natural factors that have the greatest impact on coastal erosion processes may change. This assumption is based on the intensity of erosion processes and the accompanying hydrometeorological situations. Natural factors primarily influence the degradation of the Azov Sea coast, followed by anthropogenic factors. The main process of slope erosion occurs at the base of the cliff, where geological, morphological, hydrological, and meteorological factors combine. Anthropogenic factors—plowing along the cliff, river regulation, the placement of capital construction projects within coastal protective zones, localized concrete hydraulic structures, and the uncontrolled removal of beach material for domestic and industrial purposes—may influence the overall stability of the slope, but their contribution has not been quantified.

3.1. Northern Site

For the Northern Site, our previous research indicates that storm waves rarely generate maximum dynamic loads on the shore [

26]. This is because most storms with wave heights exceeding 2 m, driven by south-westerly and south-easterly winds, produce waves that approach the coastline at a near-parallel angle. Consequently, a significant portion of the wave energy is dissipated alongshore rather than being transformed into a direct, high-magnitude shock load. The highest recorded dynamic load values for this site are approximately 2.5 tf/m

2, which align with the sea-wide average but exhibit a positive long-term trend (

Figure 2).

Over the past 25 years, the maximum concentration of fast ice in the coastal area has plummeted, declining from 90 to 100% to a mere 10–20%. While the overall ice extent in the area has not undergone a substantial reduction, with the water area still experiencing up to 100% ice cover annually, a significant shortening of the ice season duration is clearly evident. This site is also subject to ice pile-up, with our winter 2024/2025 observations recording it up to 1.6 m. Despite the relative attenuation of direct wave load, this area exhibits some of the highest erosion rates on the entire coast. Consequently, we conclude that the primary drivers of coastal destruction along the northern Taganrog Bay are its susceptible geomorphological structure, storm surge phenomena, and extreme storm events.

During the initial sub-period (2000–2009), the coastal zone was consistently protected by extensive fast ice, which covered 70% or more of the adjacent waters annually with the exception of 2004, when fast ice was not observed in the water area. Here, fast ice extent is the percentage of the coastal water area occupied. The total ice cover of the site reached 90%. Concurrently, storm activity was moderate; the annual number of storms with wave heights greater than 2 m, a hazardous threshold for this sea, ranged from 1 to 7, averaging 3–4 events per year. The most significant storm of this period occurred in November 2007, prior to ice formation, generating waves up to 3.3 m high, though corresponding shoreline displacement data are unavailable. Furthermore, literary sources indicate an absence of major storm surges during these years. This combination of extensive winter ice buffering and modest storm forcing resulted in conditional hydro-meteorological stability. Consequently, maximum annual erosion rates at the Northern Site were limited to 1.7–1.8 m (

Table 1). We therefore conclude that pre-2009 coastal dynamics were primarily governed by the inherent geological structure and background wave activity, with the annual fast ice formation serving as an additional protective factor that significantly attenuated winter wave energy.

The latter sub-period (2010–2024) was marked by a pronounced regime shift. The fast ice cover underwent a drastic reduction, disappearing entirely in the coastal waters during the winters of 2018, 2020, and 2024. While the total winter ice extent remained relatively high (averaging ~70%), its shortened duration and the loss of the stable coastal fringe fundamentally altered the exposure of the shoreline. Concurrently, storm patterns transformed. A normalization of storm frequency revealed a significant temporal shift: activity previously concentrated in January, March, and November (2000–2009), substantially increased from 2010 onward in February, July–October, and December, averaging 6–7 events (H > 2.0 m) per year. This expansion of the storm season into the summer and autumn was driven by enhanced wind activity and a concurrent, abrupt increase in hazardous surge events. These more frequent and seasonally extended storms also grew in intensity, with the maximum significant wave height rising to 3.8 m (September 2014;

Figure 3) and the peak dynamic shore load reaching 2.46 tf/m

2. The synergistic impact of sea ice decrease and intensified hydrodynamic forcing led to a sharp increase in the maximum annual erosion rate, which rose to 5.6–8.5 m/year (

Figure 4). This evidence indicates that the key driver of coastal destruction at the Northern Site post-2010 was the cumulative impact of increased storm and surge activity, particularly its new prominence during the ice-free summer-autumn season.

3.2. Southern Site

In contrast to the Northern Site, the Southern Site experiences significantly higher hydrodynamic forcing, with maximum dynamic load values reaching 10.0 tf/m2. These peak loads exhibit substantial interannual variability but generally increase with time, similar to the northern coast. The ice regime is notably different; while ice forms annually, its maximum extent rarely exceeds 80% of the site’s area. Fast ice was historically intermittent, covering an average of 20–30% of the area in years when it formed, but it has been completely absent since 2017. A further characteristic of this site is the periodic occurrence of short-duration ice pile-up events onto the shore.

During the 2000–2009 sub-period, the Southern Site was characterized by annual ice formation, with fast ice averaging 23% coverage and total ice cover reaching 52%. Its key differentiating factor from the Northern Site was a high exposure to south-western winds, which drive powerful storm surges. This direct exposure resulted in substantially higher hydrodynamic forcing, with a maximum dynamic load of 9.39 tf/m2 recorded. Under this regime, the site experienced elevated but variable average maximum erosion rates of 2.1 to 4.3 m/year.

The latter sub-period (2010–2024) marks a significant shift in the coastal dynamics of the Southern Site (

Figure 2 and

Figure 5). It is characterized by a drastic reduction in fast ice, culminating in its complete absence from the coastal waters after 2018. Paradoxically, this occurred alongside a notable decrease in average maximum erosion rates, which fell to a range of 0.74–1.90 m/year, even as maximum wave heights continued to increase. A key observation is that the peak dynamic load on the shore remained virtually unchanged. Consequently, since 2016, the maximum erosion rates at the Southern Site have not only declined but have also fallen below those recorded at the Northern Site. Meanwhile, average speeds in these areas remain stable. The increase in maximum wave height and dynamic load is due to an increase in maximum wind speeds on the southern coast of Taganrog Bay.

Analysis confirms that storm activity and extreme surges were the dominant drivers of erosion intensification at the Southern Site throughout the study period. The most significant episodes of shoreline retreat consistently coincided with years featuring the highest dynamic loads and prolonged storm durations, typically associated with wave heights of 2.5–2.6 m. This indicates that while the long-term maximum erosion rate has decreased in the recent sub-period, the site remains highly sensitive to short-term, high-energy storm and surge events.

The year 2014 represents a benchmark extreme event, distinguished by the highest recorded values of wave height, storm duration, and surge level across the study period (

Table 1 and

Table 2). The geomorphic response was immediate and severe, with annual erosion rates peaking at 8.5 m in the Northern Site and 5.2 m in the Southern Site. In the subsequent years (2015–2017), erosion rates decreased markedly in both areas, with the Southern Site subsequently exhibiting lower retreat rates than the Northern Site. We hypothesize that the 2014 event effectively reset the coastal profile, potentially creating a transient, stable geometry that was less susceptible to erosion under average conditions. However, this state is likely metastable; continued undercutting of the cliff base, combined with intensifying storm activity, is expected to destabilize this profile, leading to a future phase of accelerated shoreline retreat. Initially, based on our own observations and findings published in the literature, we assumed that the shore would experience maximum load as a result of the impact of such waves. However, research has shown that the maximum dynamic load does not coincide with the years when absolute maximum waves were observed. We attribute this to several factors: (1) the duration of waves with a wave height greater than 3.0 m is often short; (2) the wave direction can be parallel to the shore (especially in the northern coast), and wave energy is not released in the coastal zone. Therefore, we believe that shore load can be used as an indirect indicator of wave impact on the shore, and the shore erosion process itself is nonlinear and cumulative, requiring consideration of multiple factors.

Projected future climate change, characterized by increasing extreme wind speeds and a continued decline in ice cover, is anticipated to intensify hazardous coastal processes in the Sea of Azov. According to [

50] in the Baltic Sea drastic decrease in sea-ice cover is expected, increasing exposure to hydrodynamic forces in winter. Also, Nielsen et al. (2022) [

51] project that Arctic coastal erosion rates will increase from 0.9 ± 0.4 m/year during the historical period (1850–1950) to 1.6 ± 0.5, 2.0 ± 0.7, and 2.6 ± 0.8 m/year by the end of the 21st century under the SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5 scenarios, respectively. The trends documented in our study for the Sea of Azov, namely diminishing protective ice and increasing storm potency, suggest it is undergoing a similar trajectory. This parallel underscores the accelerating vulnerability of mid-latitude, seasonally ice-covered coastlines worldwide, highlighting an urgent need for proactive coastal management strategies.

Several methodological constraints warrant consideration in the interpretation of our results. While our atmospheric and wave models (WRF at 10 km, SWAN with 1 h) provide robust regional analysis, the 10 × 10 km analytical grid inherently averages hydrodynamic forcing, potentially smoothing critical micro-scale variations in wave run-up. Furthermore, the absence of a direct, instantaneous correlation between annual erosion and hydrometeorological parameters underscores the significance of metachronous processes. The erosion of cohesive cliffs involves complex preparatory stages, including material saturation, freeze–thaw weathering, and cumulative fatigue, which can introduce a substantial time lag between a storm event and subsequent slope failure. While geological and geomorphologycal structure was identified as a key control, the quantitative influence of specific lithological heterogeneities and localized anthropogenic impacts was not explicitly resolved.

4. Conclusions

This study analyzed the coastal erosion dynamics of the Sea of Azov from 2000 to 2025 using a comprehensive approach that integrated numerical modeling, satellite remote sensing, and long-term field measurements. Our investigation focused on two distinct coastal sites exhibiting the highest erosion rates in the region. An analysis of storm waves, dynamic loading, and spatiotemporal sea ice dynamics was conducted for two areas with the highest erosion rates. These areas were identified through analysis of accumulated data and field observations. The study areas—northern and southern—differ in ice extent and coastline configuration relative to storm waves and surge. However, they have similar geomorphological structures, and both coastlines are classified as abrasive. The analysis of such small coastal areas is driven by the need to identify key factors, as these factors cannot be accurately determined when generalized to larger areas.

Our previous studies [

26] revealed a shift in the hydrometeorological season of the Sea of Azov since the early 2000s: rising air temperatures, an increase in the frequency of mild winters, a shift in the timing of ice formation and destruction to later and earlier, respectively, a steady decrease in sea ice cover and fast ice, and an increase in wind speed from November to March, which leads to a high storm dynamic load on the coast. After 2000, an increase in the height of significant waves was noted against the background of a decrease in the number and duration of storms, and an increase in the number of storm surges. According to long-term observations, the stormiest months in the region are November through March. However, since the 2010s, the number of extreme storm events accompanied by surges has increased during the warm ice-free period. It is assumed that fast ice acts as a protective barrier for the coastal zone during storms and storm surges. Ice accumulations on the coast can have a negative impact when melting, contributing to the erosion of the base of coastal cliffs, or create an additional impact during ice surges, or a positive impact, protecting the coast from storms in late winter and early spring.

Based on the analysis of hydrometeorological information and long-term observation data on the dynamics of the coastal zone, in this paper the study period 2000–2025 is divided into two sub-periods—2000–2009 and 2010–2025. We believe that, depending on changes in the hydrometeorological regime, key natural factors that have the greatest impact on coastal erosion processes may change.

Based on our hypothesis, a shorter ice season, resulting in an increased duration of open water, even with a constant number of winter storms and surges, should lead to increased dynamic impacts on the coast during the winter. This, in turn, may lead to more intense erosion processes on the coast of the Sea of Azov. An analysis of two coastal areas with the highest erosion rates showed that the presence of sea ice reduces the dynamic load by an average of 1.5 times, limiting storm impacts on the coast.

The results revealed that prior to 2009, the key factors in coastal erosion in the northern region were geological structure and wave activity, with the annual formation of fast ice acting as an additional limiting factor in winter, providing protection from wave activity. Since 2010, the number of storms in February, July–October, and December has increased significantly, exacerbated by a sharp increase in the number of dangerous surges per year. Since 2010, the key factor in coastal erosion in the northern region has become the cumulative effect of a gradual increase in storm and surge activity, including in the summer-fall season.

For the southern region, the main factor in the intensification of abrasive processes throughout the study period has been storm activity and extreme surges.

Despite the fact that ice is observed annually in the study areas for an average of approximately two months, the protective function of sea ice, including fast ice, has not been identified based on the available data for the two areas. Maximum coastal erosion rates in the Sea of Azov were recorded in years with extreme hydrological events—surges, storms, or a combination of storms and surges—occurring before or after the ice season. The obtained results can be approximated for the shores of other seas with similar geomorphological structures and periodic ice cover. The interaction between the coastal zone and hydrometeorological factors, such as hydrodynamic impacts, storm surges, and ice cover, is a complex process, the effects of which can manifest themselves over a long period of time.