GIS-Integrated Groundwater Flow Modeling for Heterogeneous Media: Application to the Calera Aquifer

Abstract

1. Introduction

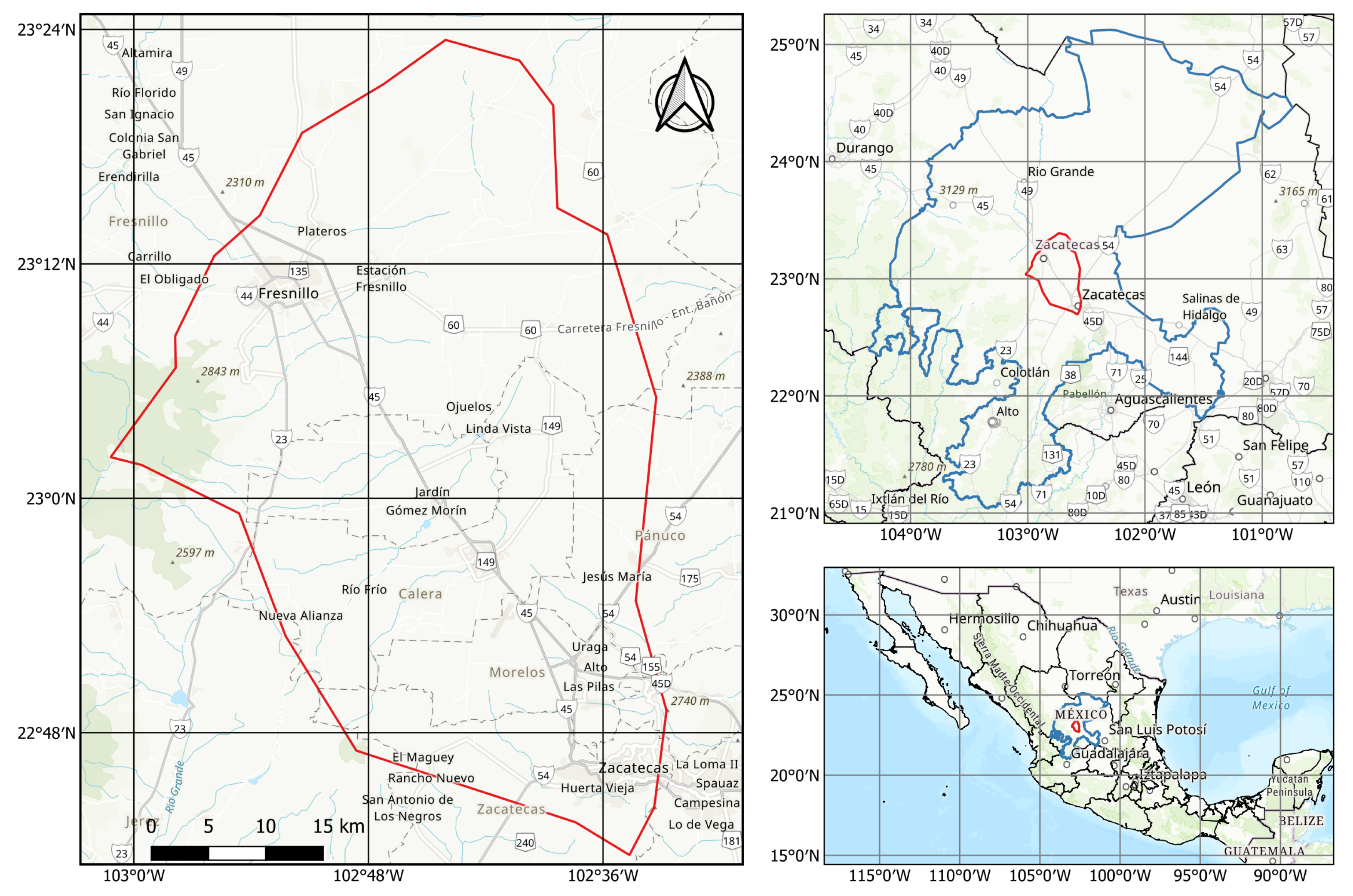

2. Study Area

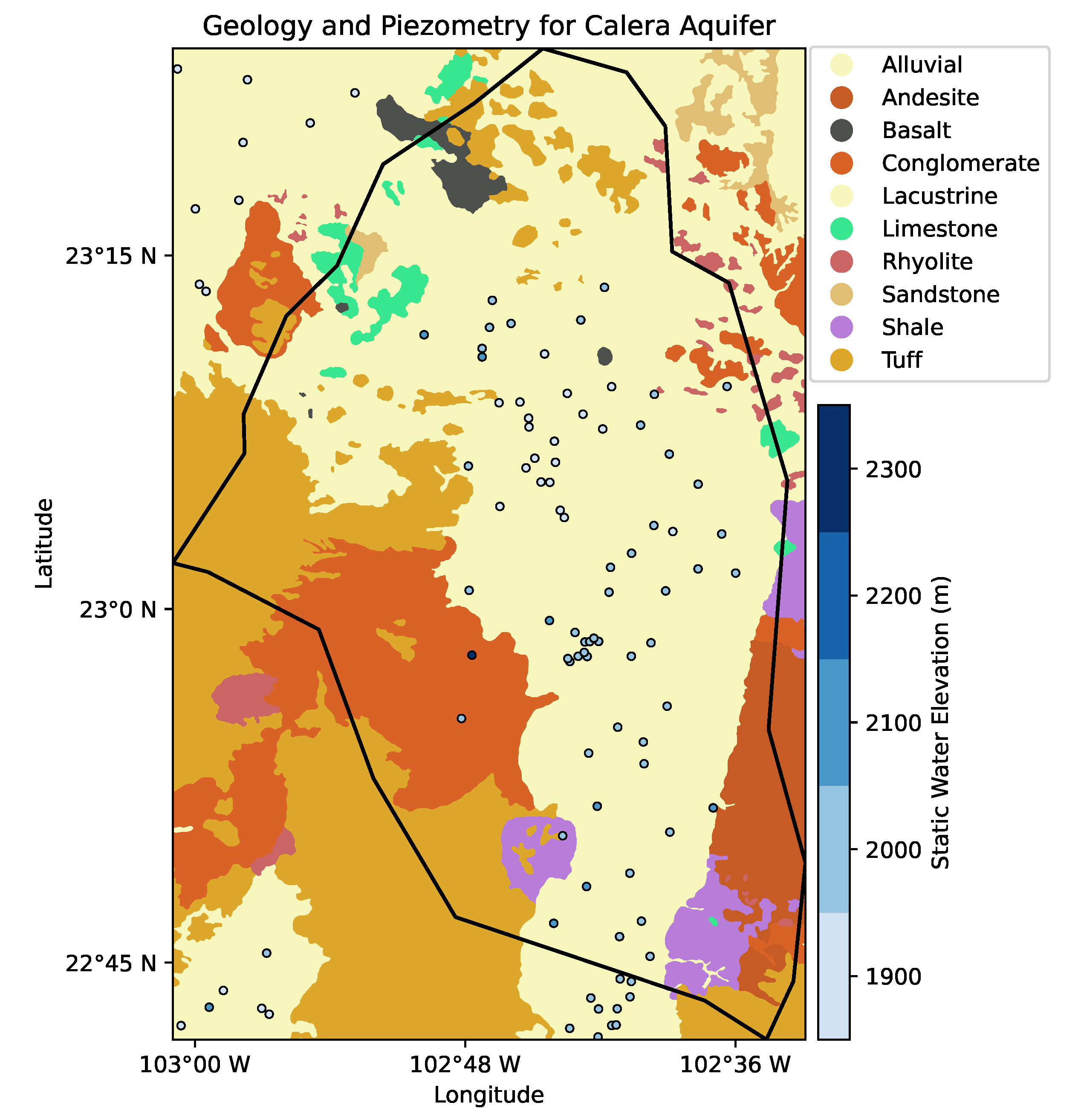

2.1. Hydrogeological Background

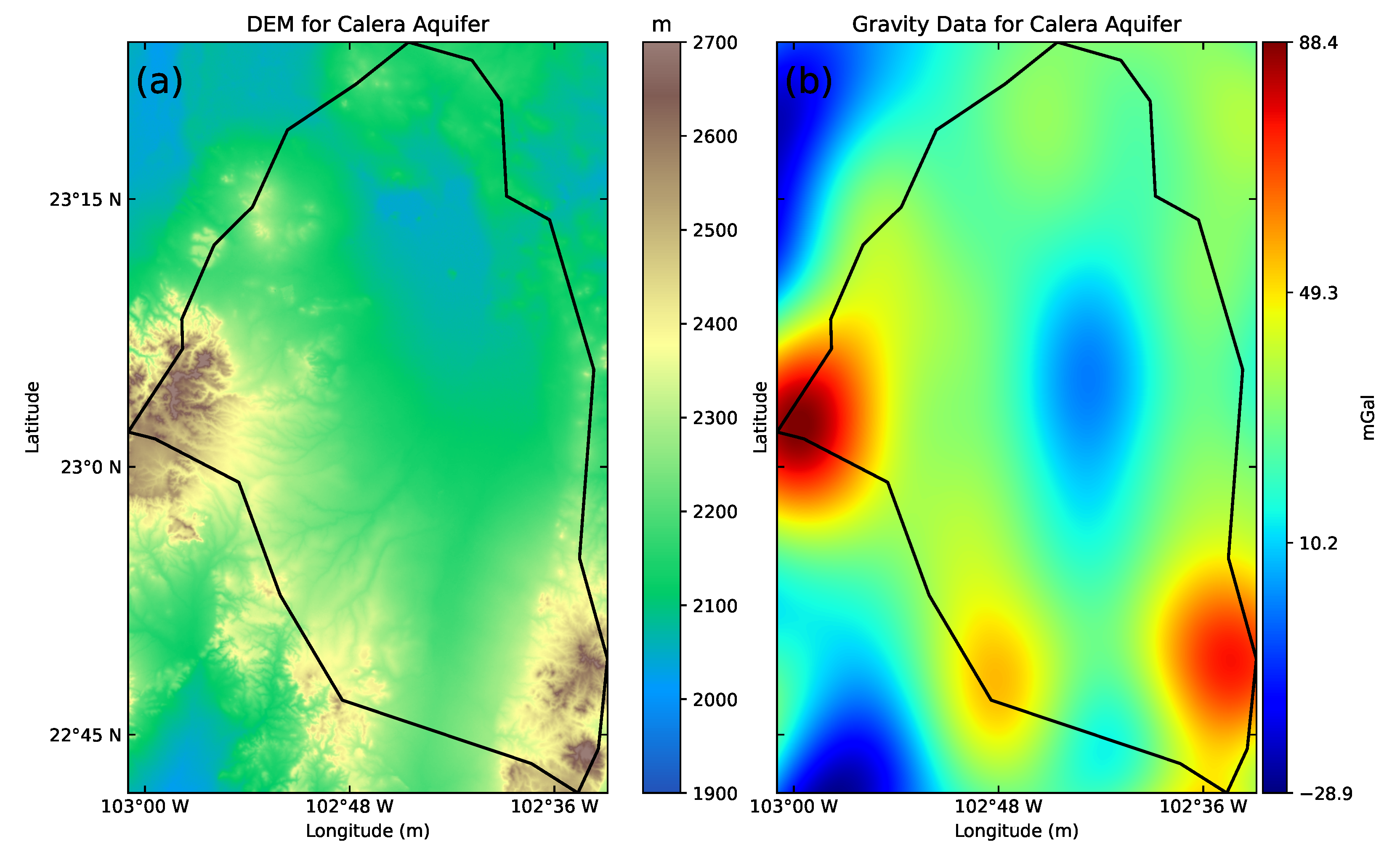

2.2. Digital Elevation Map and Gravity of Calera Aquifer

3. Methodology

3.1. Groundwater Flow Modeling

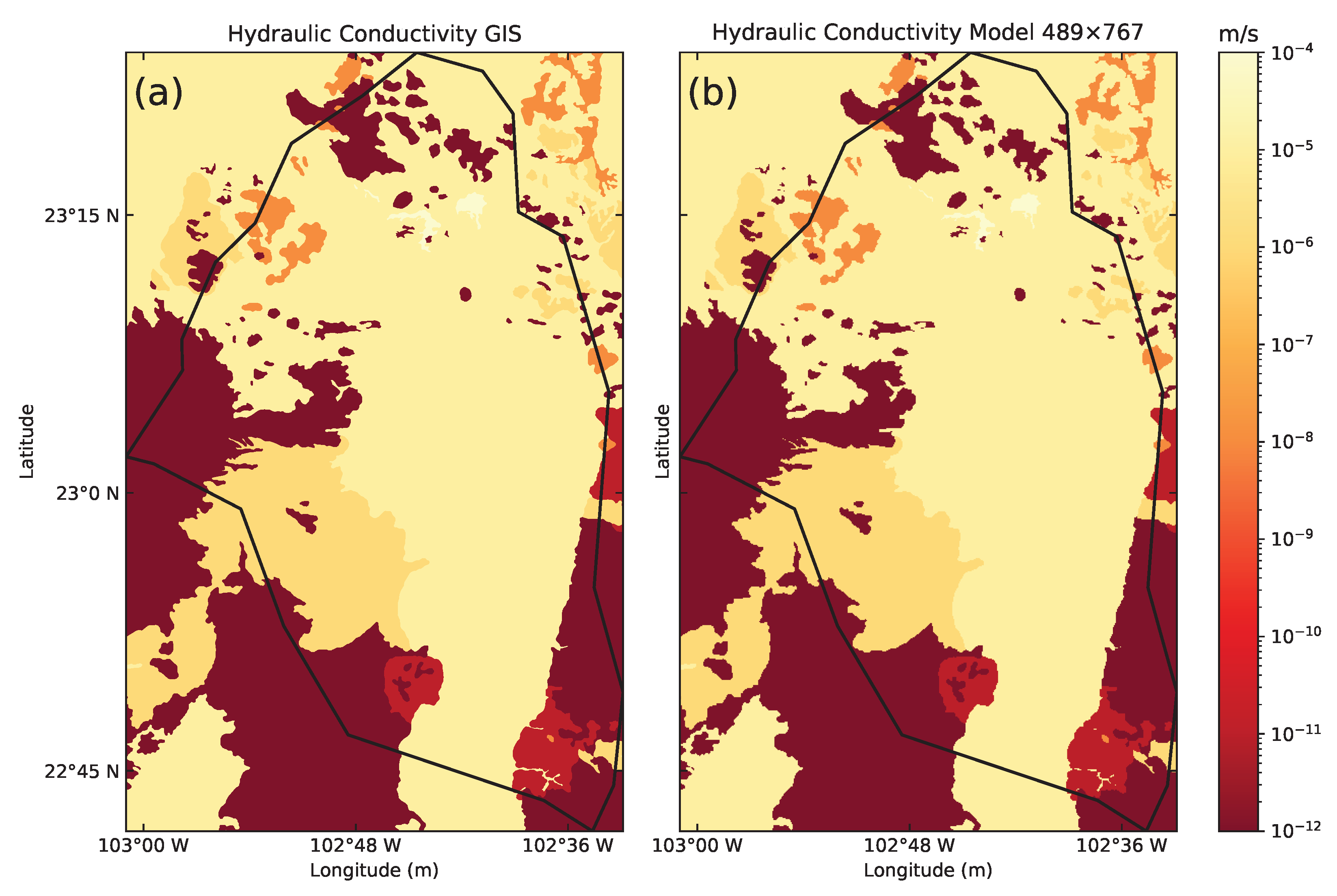

3.2. Conductivity Model Creation

4. Results and Discussion

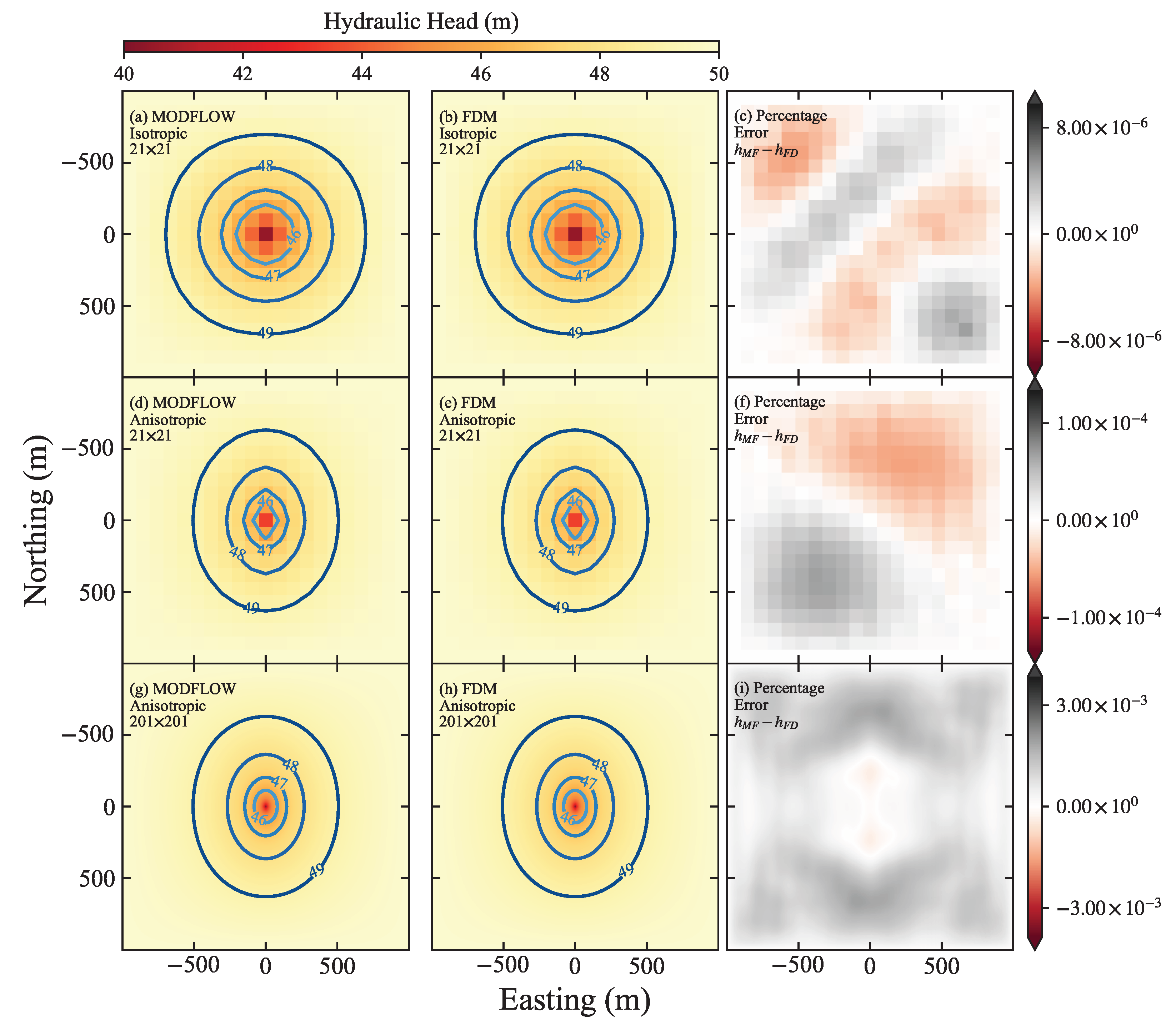

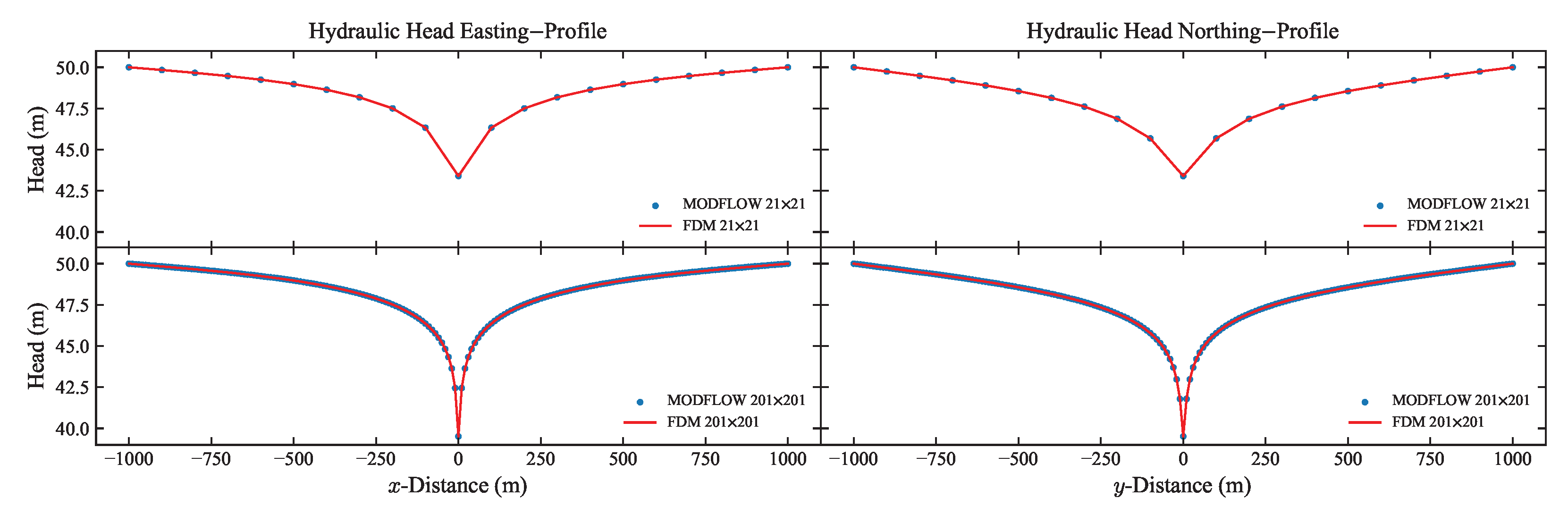

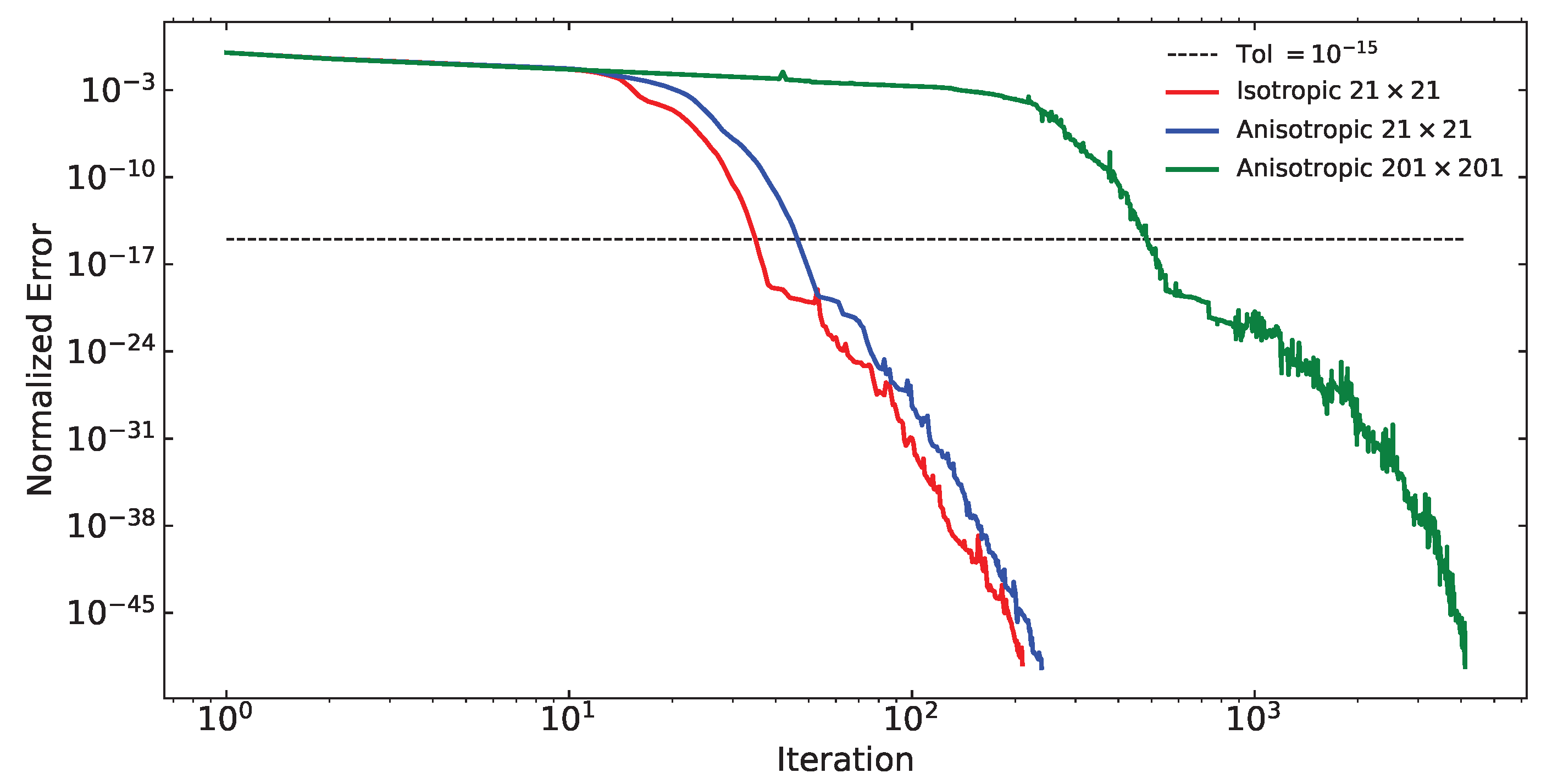

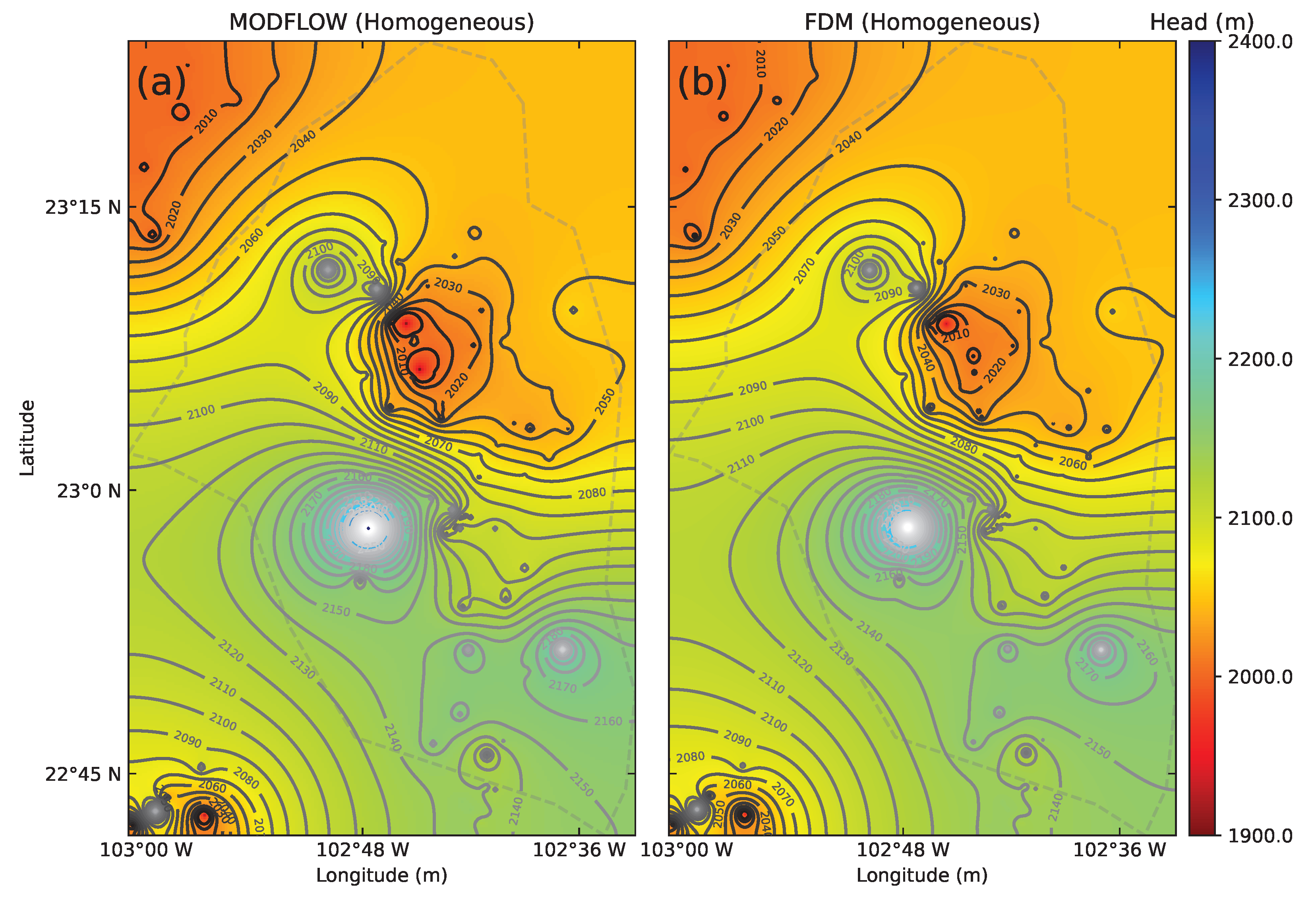

4.1. Validation of Our Scheme

4.2. Calera Aquifer Groundwater Modeling for Homogeneous Medium

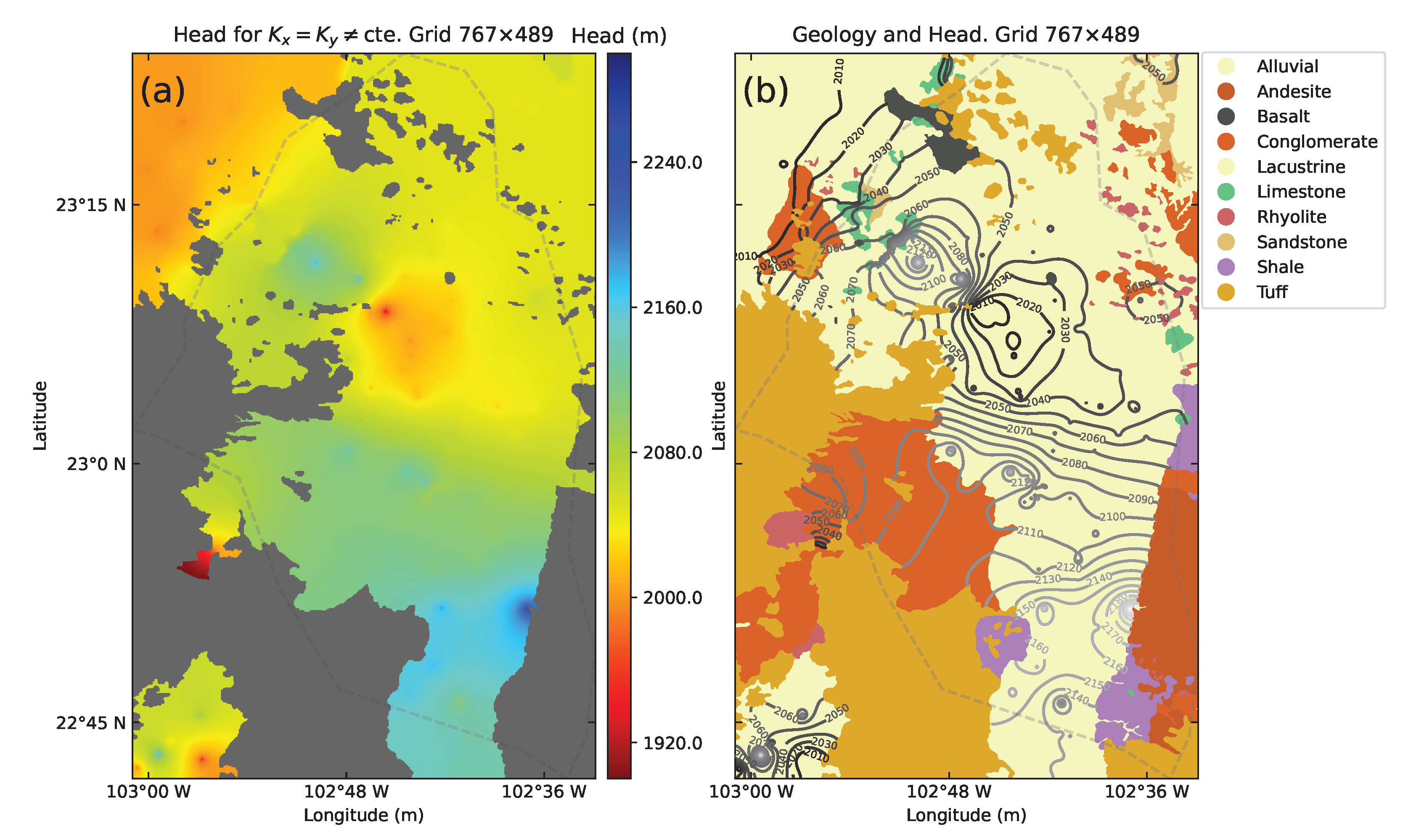

4.3. Calera Aquifer Modeling Heterogeneous Media

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MODFLOW | Modular hydrologic flow model |

| FDM | Finite Difference Method |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| CONAGUA | Mexican National Water Commission |

| SWL | Static Water Level |

| SWE | Static Water Elevation |

Appendix A. The Finite Difference Method

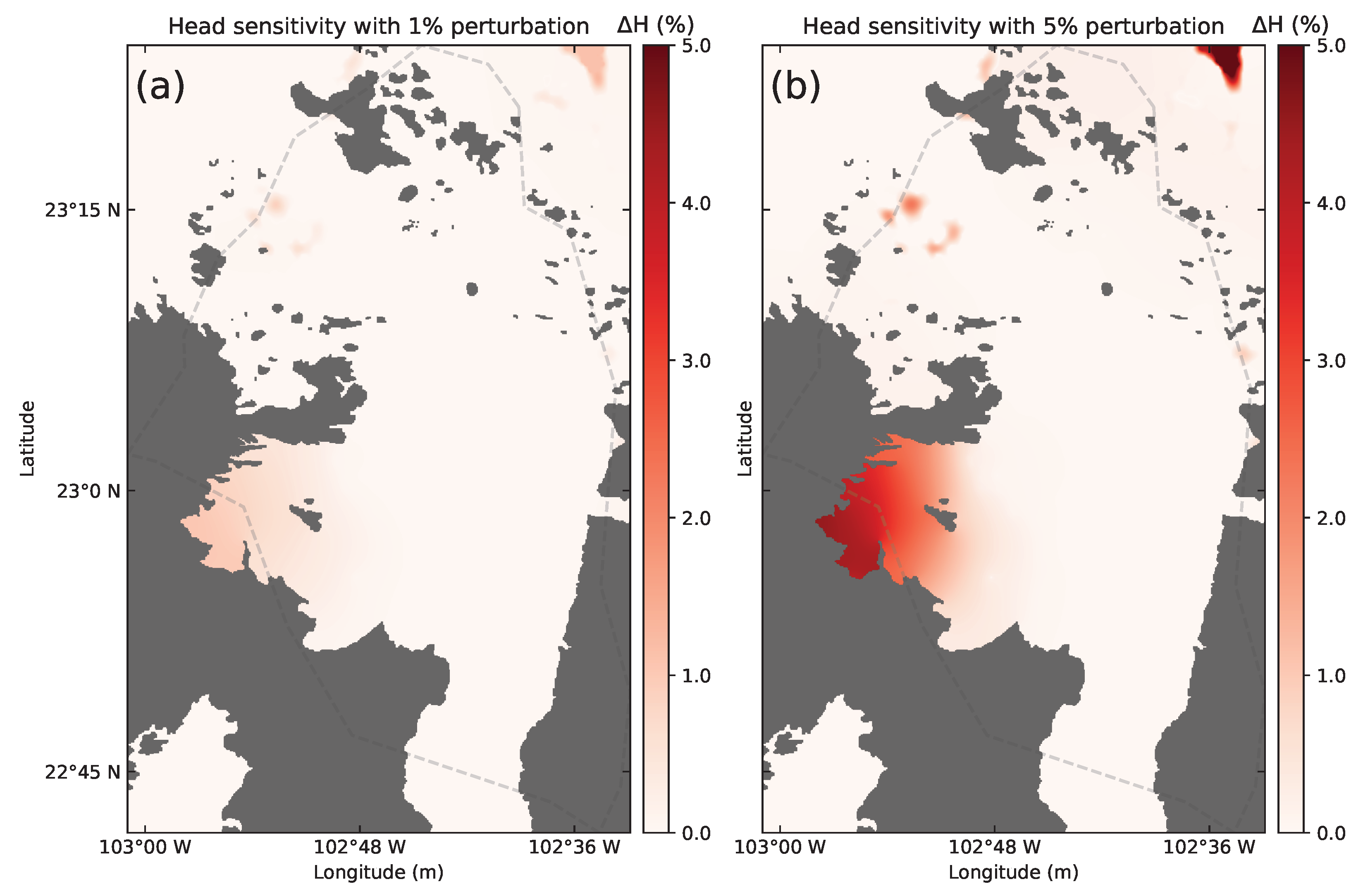

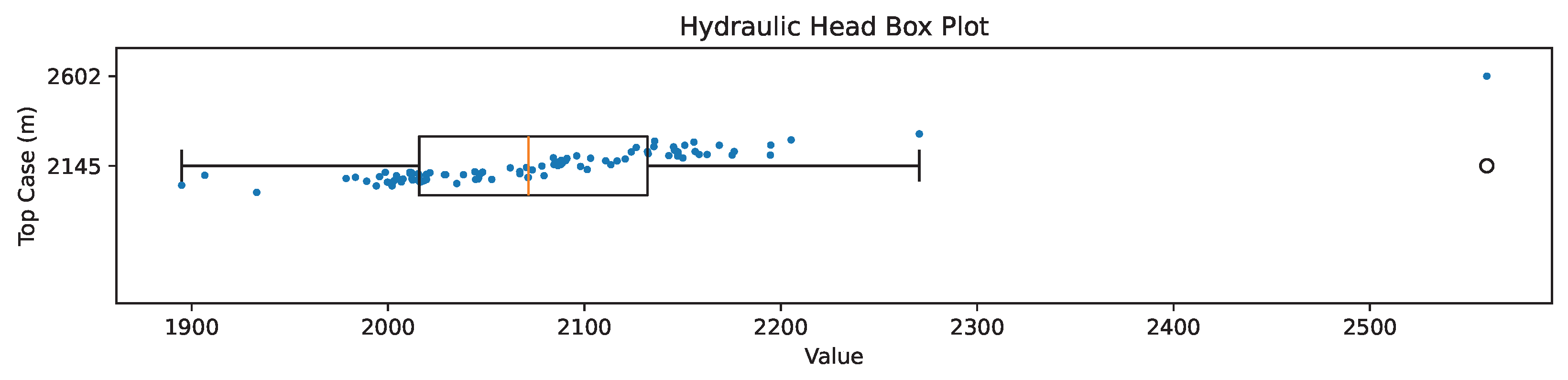

Appendix B. Sensitivity Analysis

References

- Giordano, M. Global groundwater? Issues and solutions. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igor, S. World fresh water resources. In Water in Crisis: A Guide to the World’s; Oxford University Press, Inc.: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophocleous, M. Global and regional water availability and demand: Prospects for the future. Nat. Resour. Res. 2004, 13, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzelbach, W.; Bauer, P.; Siegfried, T.; Brunner, P. Sustainable groundwater management—Problems and scientific tools. Episodes J. Int. Geosci. 2003, 26, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Solis, O.; González Trinidad, J.; Junez-Ferreira, H.; Cardona, A.; Bautista Capetillo, C. Integrative methodology for the identification of groundwater flow patterns: Application in a semi-arid region of Mexico. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2016, 14, 645–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredehoeft, J.D. The Water Budget Myth Revisited: Why Hydrogeologists Model. Groundwater 2002, 40, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis, C.V. The relation between the lowering of the Piezometric surface and the rate and duration of discharge of a well using ground-water storage. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1935, 16, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, O.; González, J.; Júnez-Ferreira, H.; Bautista, C.F.; Cardona, A. Correlation of arsenic and fluoride in the groundwater for human consumption in a semiarid region of Mexico. Procedia Eng. 2017, 186, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Martinez, C.J.; Álvarez-Fuentes, G.; Aguilar-Benitez, G.; Can-Chulím, Á.; Pinedo-Escobar, J.A. Water quality for agricultural irrigation in the Calera aquifer region in Zacatecas, Mexico. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2021, 12, 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Armendariz, C.A.; Banning, A.; Cardona Benavides, A. Geochemical evolution along regional groundwater flow in a semi-arid closed basin using a multi-tracing approach. J. Hydrol. 2024, 632, 130895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Trinidad, J.; Pacheco-Guerrero, A.; Júnez-Ferreira, H.; Bautista-Capetillo, C.; Hernández-Antonio, A. Identifying groundwater recharge sites through environmental stable isotopes in an alluvial aquifer. Water 2017, 9, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbrecht, J.; Mojarro, F.; Echavarria-Chairez, F.; Bautista-Capetillo, C.; Brauer, D.; Steiner, J. Sustainable utilization of the Calera aquifer, Zacatecas, Mexico. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2013, 29, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.E.; Gowda, P.H.; Howell, T.A.; Steiner, J.L.; Mojarro, F.; Núñez, E.P.; Avila, J.R. Modeling Groundwater levels on the Calera aquifer region in central Mexico using ModFlow. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 2012, 2, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Krienen, L.; Cardona Benavides, A.; Lopez Loera, H.; Rüde, T.R. Understanding Deep Groundwater Flow Systems to Contribute to a Sustainable Use of the Water Resource in the Mexican Altiplano; Technical report; Lehr-und Forschungsgebiet Hydrogeologie: Aachen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno-García, E.; Guerrero-Suastegui, M.; Talavera-Mendoza, O. The Guerrero Composite Terrane of Western Mexico: Collision and Subsequent Rifting in a Supra-Subduction Zone; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2008; Volume 436, pp. 279–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cserna, Z. Geology of the Fresnillo area, Zacatecas, Mexico. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1976, 87, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, C.; Lang, H.; Cantú Chapa, A.; Barboza-Gudiño, R. The Triassic Zacatecas Formation in Central Mexico: Paleotectonic, paleogeo- graphic and paleobiogeographic implications. AAPG Mem. 2001, 75, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippen, R.; Buckley, S.; Agram, P.; Belz, E.; Gurrola, E.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Lavalle, M.; Martin, J.; Neumann, M.; et al. NASADEM global elevation model: Methods and progress. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, 41, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandwell, D.T.; Müller, R.D.; Smith, W.H.; Garcia, E.; Francis, R. New global marine gravity model from CryoSat-2 and Jason-1 reveals buried tectonic structure. Science 2014, 346, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.P.; Woessner, W.W.; Hunt, R.J. Applied Groundwater Modeling: Simulation of Flow and Advective Transport; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbaugh, A.W. MODFLOW-2005, the US Geological Survey Modular Ground-Water Model: The Ground-Water Flow Process; US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2005; 6. [CrossRef]

- Diersch, H.J.G. FEFLOW: Finite Element Modeling of Flow, Mass and Heat Transport in Porous and Fractured Media; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, P.; Lee, S.; Tchelepi, H.A. Multi-scale finite-volume method for elliptic problems in subsurface flow simulation. J. Comput. Phys. 2003, 187, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, M.J.; Croke, B.F.W.; Jakeman, A.J.; Peeters, L.J.M. A review of surrogate models and their application to groundwater modeling. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 5957–5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vorst, H.A. Bi-CGSTAB: A Fast and Smoothly Converging Variant of Bi-CG for the Solution of Nonsymmetric Linear Systems. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1992, 13, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, C.; Woldt, W.; Bogardi, I.; Dahab, M. Steady state groundwater flow simulation with imprecise parameters. Water Resour. Res. 1995, 31, 2709–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordahl, K.; den Bossche, J.V.; Fleischmann, M.; Wasserman, J.; McBride, J.; Gerard, J.; Tratner, J.; Perry, M.; Badaracco, A.G.; Farmer, C.; et al. geopandas/geopandas: v0.8.1. 2020. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/3946761 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Pulla, S.T.; Yasarer, H.; Yarbrough, L.D. GRACE downscaler: A framework to develop and evaluate downscaling models for GRACE. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, J. Dynamics of Fluids in Porous Media; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeter, E.P.; Hill, M.C. Inverse models: A necessary next step in ground-water modeling. Groundwater 1997, 35, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.D.; Langevin, C.D.; Banta, E.R. Documentation for the MODFLOW 6 Framework; Technical report; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Langevin, C.D.; Hughes, J.D.; Banta, E.R.; Niswonger, R.G.; Panday, S.; Provost, A.M. Documentation for the MODFLOW 6 Groundwater Flow Model; Technical report; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Freeze, R.A.; Cherry, J.A. Groundwater; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1979; Volume 176, pp. 161–177. Available online: https://gw-project.org/books/groundwater/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Spitzer, K. A 3-D finite-difference algorithm for DC resistivity modelling using conjugate gradient methods. Geophys. J. Int. 1995, 123, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rock | K (m/s) | Rock | K (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alluvial | Limestone | ||

| Andesite Porfidic | Ryolite | ||

| Basalt | Sandstone | ||

| Conglomerate | Shale | ||

| Lacustrine | Tuff |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silva-Avalos, R.U.; Júnez-Ferreira, H.E.; González-Trinidad, J.; De Basabe, J.D.; Ortiz-Acuña, L.G. GIS-Integrated Groundwater Flow Modeling for Heterogeneous Media: Application to the Calera Aquifer. Water 2026, 18, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010059

Silva-Avalos RU, Júnez-Ferreira HE, González-Trinidad J, De Basabe JD, Ortiz-Acuña LG. GIS-Integrated Groundwater Flow Modeling for Heterogeneous Media: Application to the Calera Aquifer. Water. 2026; 18(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva-Avalos, Raúl Ulices, Hugo Enrique Júnez-Ferreira, Julián González-Trinidad, Jonas D. De Basabe, and Luis Gerardo Ortiz-Acuña. 2026. "GIS-Integrated Groundwater Flow Modeling for Heterogeneous Media: Application to the Calera Aquifer" Water 18, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010059

APA StyleSilva-Avalos, R. U., Júnez-Ferreira, H. E., González-Trinidad, J., De Basabe, J. D., & Ortiz-Acuña, L. G. (2026). GIS-Integrated Groundwater Flow Modeling for Heterogeneous Media: Application to the Calera Aquifer. Water, 18(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010059