Assessing Erosion-Triggering Rainfall Patterns in Central Italy: Frequency, Trends, and Implications for Soil Protection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Rainfall Data

2.2. Thresholds of Rainfall Characteristics Associated with Erosive Events

2.3. Spatiotemporal Characterization of Rainfall Events Above the Established Thresholds

3. Results

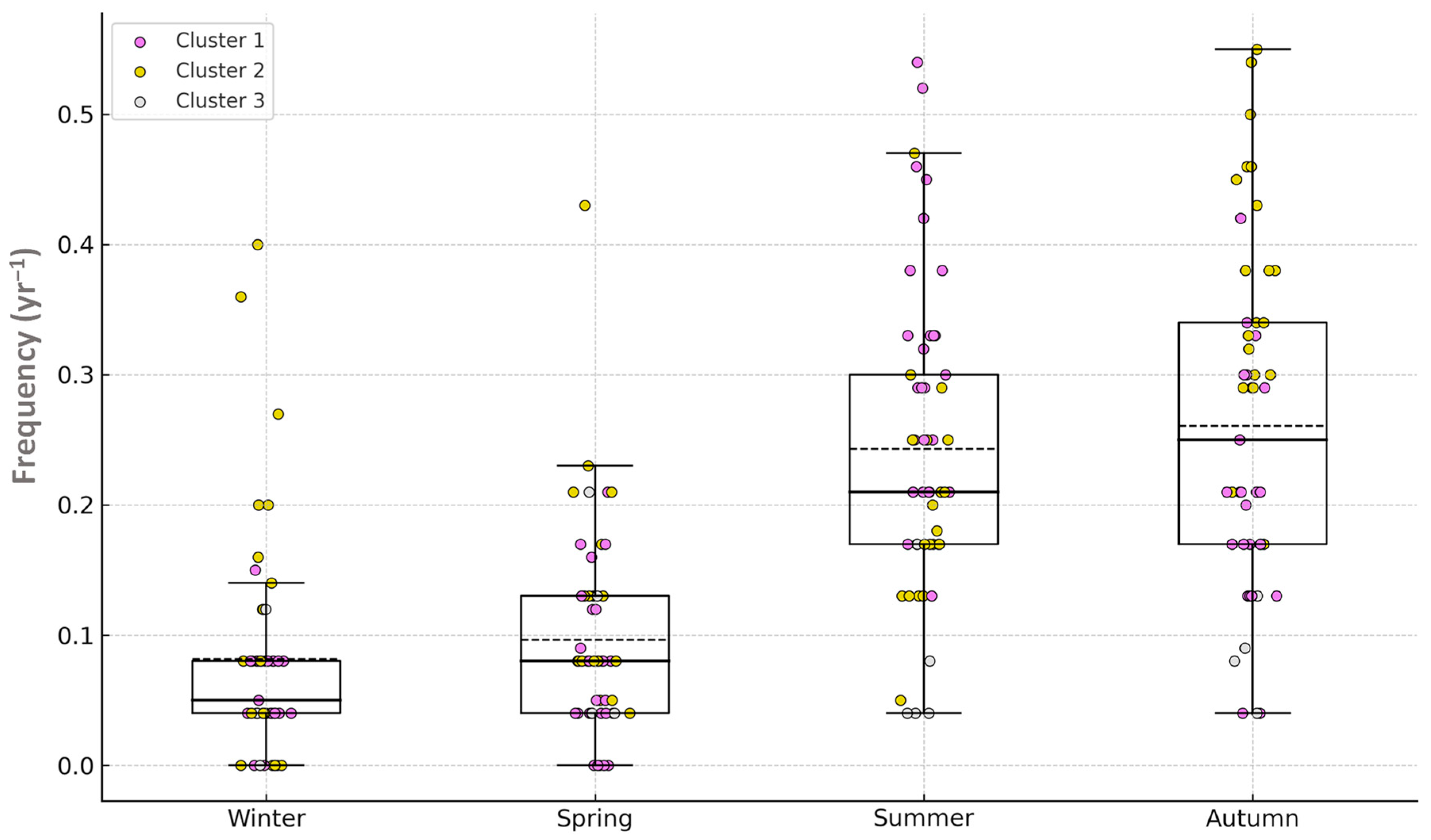

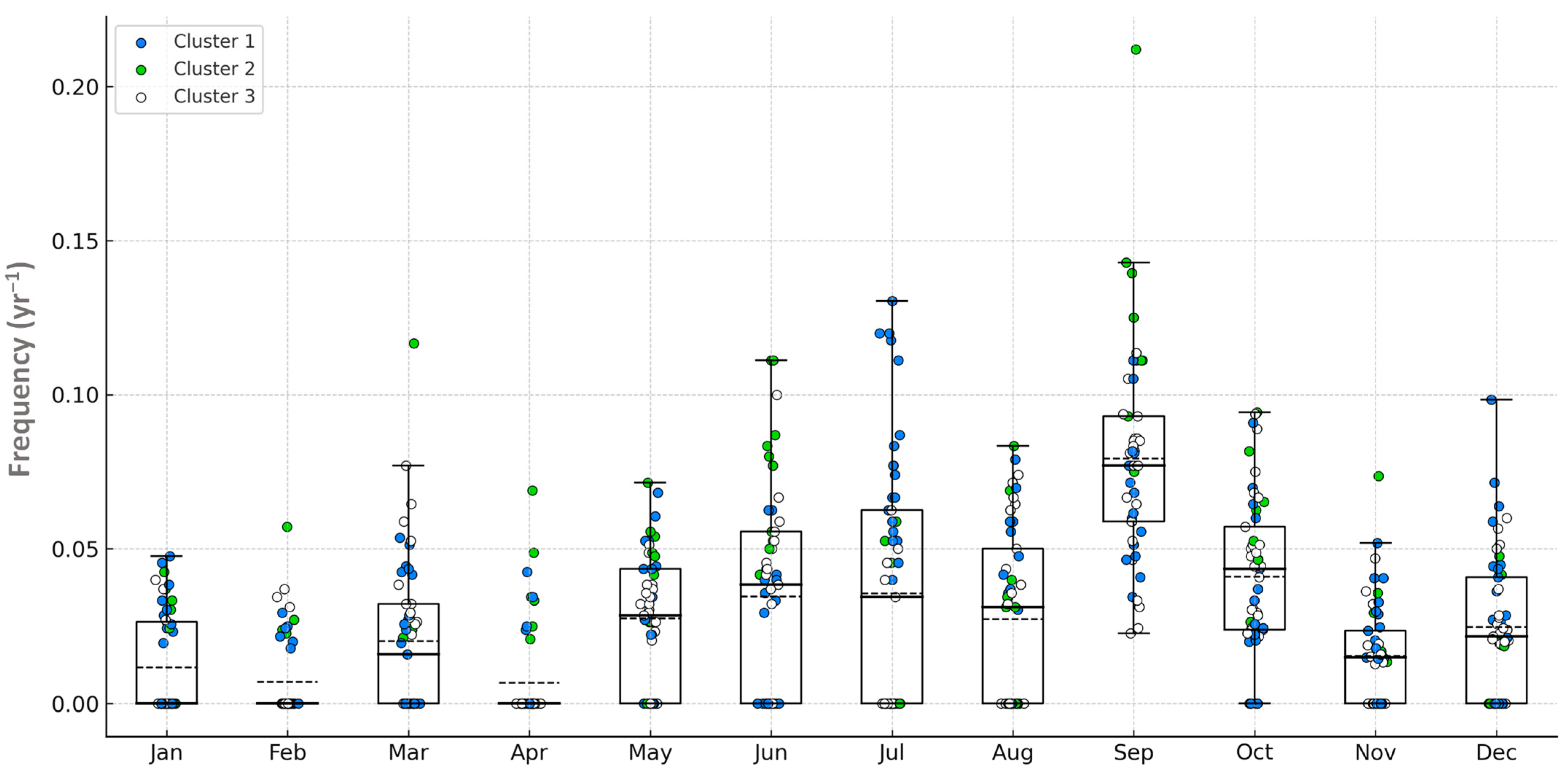

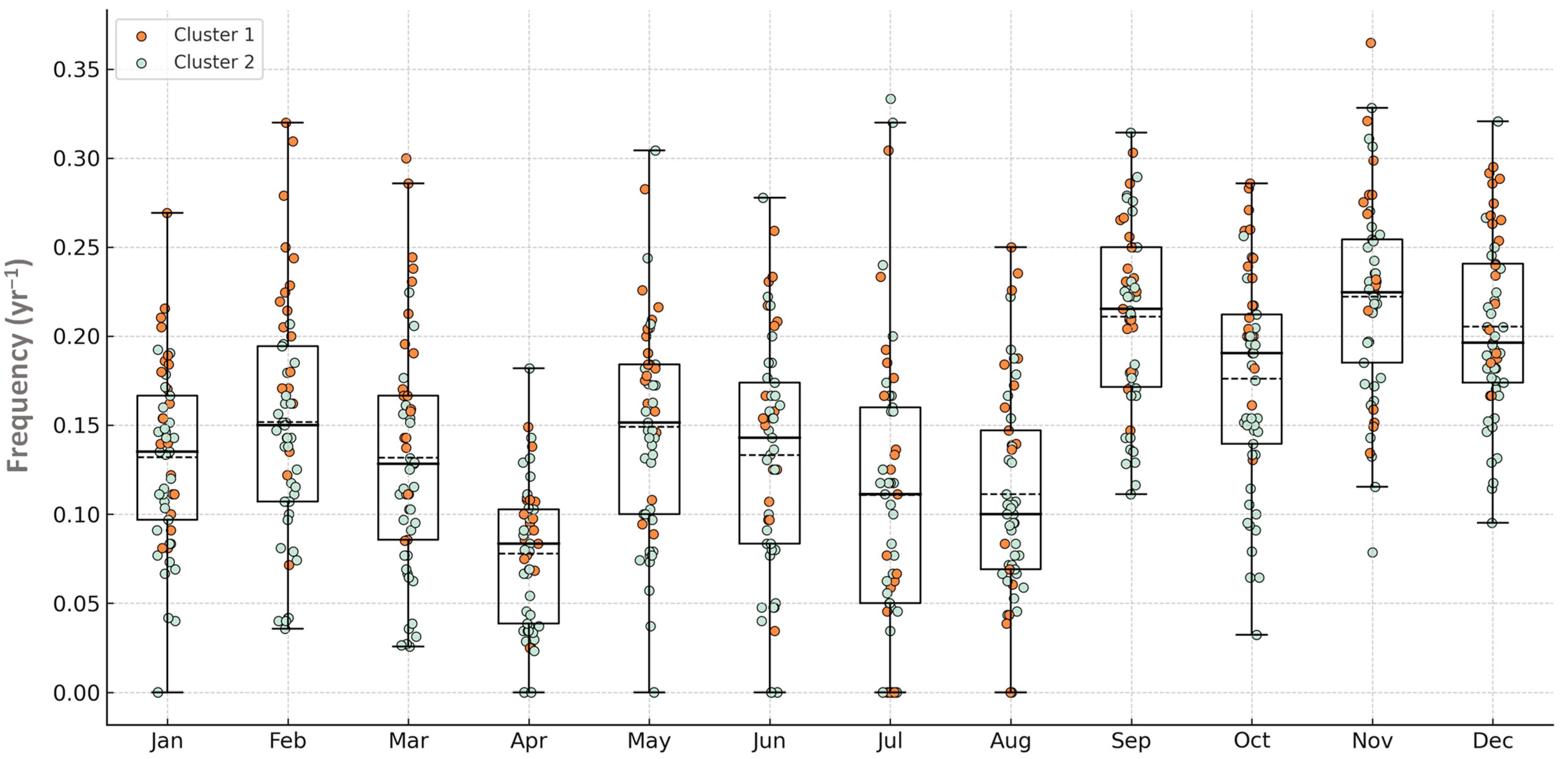

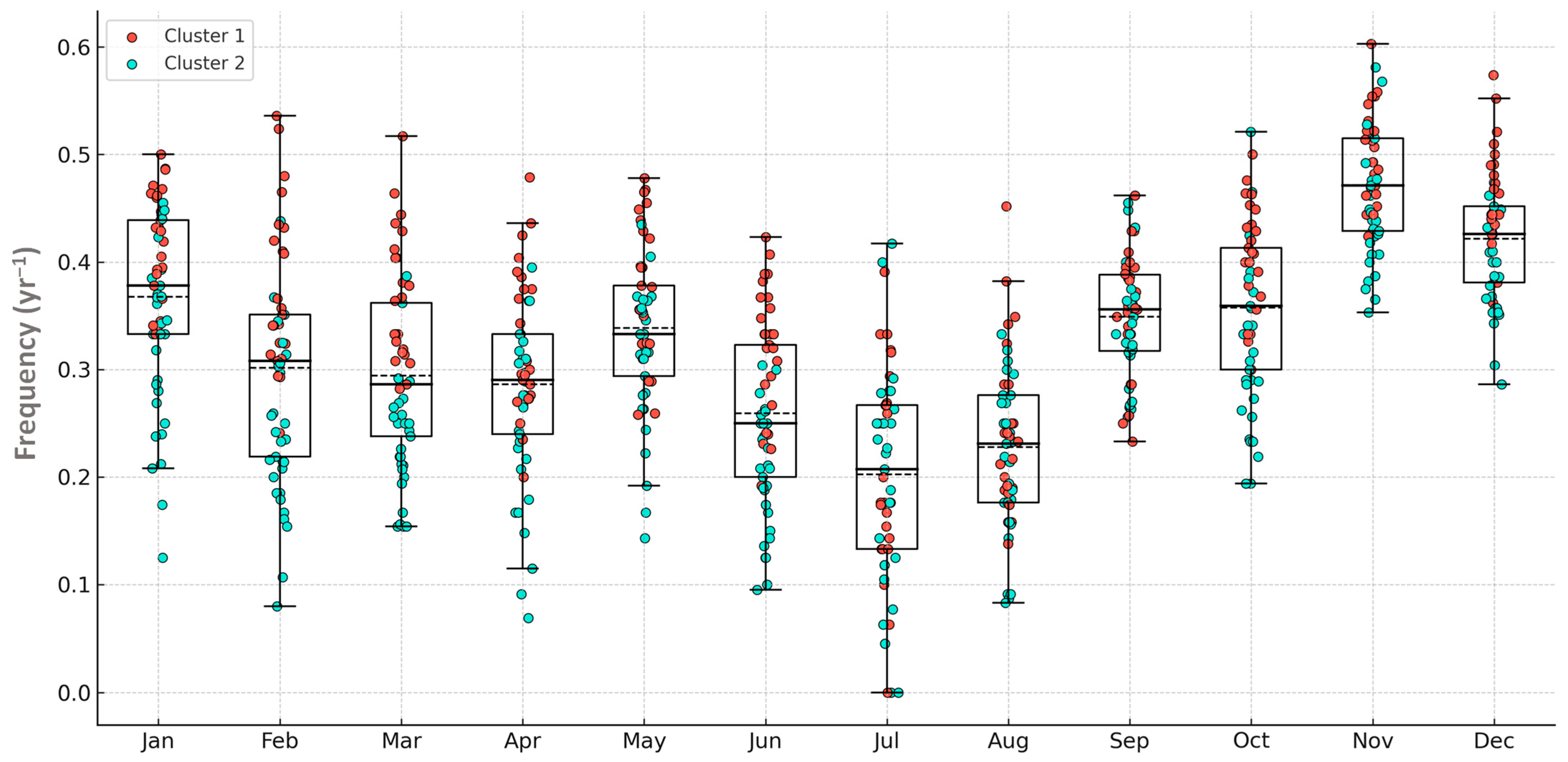

Spatiotemporal Variability of EEs and REs Occurrence Frequency in the Region

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EE | Erosive Event |

| NE | Non-Erosive Event |

| RE | Rill Event |

Appendix A

References

- Cerdan, O.; Govers, G.; Le Bissonnais, Y.; Van Oost, K.; Poesen, J.; Saby, N.; Gobin, A.; Vacca, A.; Quinton, J.; Auerswald, K.; et al. Rates and Spatial Variations of Soil Erosion in Europe: A Study Based on Erosion Plot Data. Geomorphology 2010, 122, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.S.S.; Seifollahi-Aghmiuni, S.; Destouni, G.; Ghajarnia, N.; Kalantari, Z. Soil Degradation in the European Mediterranean Region: Processes, Status and Consequences. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piacentini, T.; Galli, A.; Marsala, V.; Miccadei, E. Analysis of Soil Erosion Induced by Heavy Rainfall: A Case Study from the NE Abruzzo Hills Area in Central Italy. Water 2018, 10, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufalini, M.; Materazzi, M.; Martinello, C.; Rotigliano, E.; Pambianchi, G.; Tromboni, M.; Paniccià, M. Soil Erosion and Deposition Rate Inside an Artificial Reservoir in Central Italy: Bathymetry versus RUSLE and Morphometry. Land 2022, 11, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, E.A.C.; Lorenzetti, R. Soil Degradation Processes in the Italian Agricultural and Forest Ecosystems. Ital. J. Agron. 2013, 8, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Ballabio, C.; Himics, M.; Scarpa, S.; Matthews, F.; Bogonos, M.; Poesen, J.; Borrelli, P. Projections of Soil Loss by Water Erosion in Europe by 2050. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 124, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Ballabio, C.; Borrelli, P.; Meusburger, K. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Rainfall Erosivity and Erosivity Density in Greece. CATENA 2016, 137, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, C.; Klik, A.; Stumpp, C.; Laaha, G.; Strauss, P.; Özcelik, N.B.; Pistotnik, G.; Yin, S.; Dostal, T.; Gaona, G.; et al. Rainfall Erosivity across Austria’s Main Agricultural Areas: Identification of Rainfall Characteristics and Spatiotemporal Patterns. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todisco, F.; Massimi Alunno, A.; Vergni, L. Spatial Distribution, Temporal Behaviour, and Trends of Rainfall Erosivity in Central Italy Using Coarse Data. Water 2025, 17, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Martínez, M.; Beguería, S. Trends in Rainfall Erosivity in NE Spain at Annual, Seasonal and Daily Scales, 1955–2006. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 3551–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uber, M.; Haller, M.; Brendel, C.; Hillebrand, G.; Hoffmann, T. Past, Present and Future Rainfall Erosivity in Central Europe Based on Convection-Permitting Climate Simulations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldegebrael, S.M.; Romano, N.; Pumo, D.; Deidda, R.; Ippolito, M.; Cannarozzo, M.; Langousis, A.; Serafeim, A.V.; Manfreda, S.; Nasta, P. Empirical Approaches to Estimate Rainfall Erosivity from Coarse Temporal Resolution Precipitation Data in the Mediterranean Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 996, 180122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallan, E.; Bagarello, V.; Ferro, V.; Pampalone, V.; Borga, M. Evaluation and Projected Changes in Rainfall Erosivity: Topography Dependence Revealed by Convection-Permitting Climate Projections for the Mediterranean Island of Sicily. CATENA 2025, 254, 108975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulano, R.; Santini, M.; Mancini, M.; Stojiljkovic, M.; Rianna, G. Monthly to Seasonal Rainfall Erosivity over Italy: Current Assessment by Empirical Model and Future Projections by EURO-CORDEX Ensemble. CATENA 2023, 223, 106943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischmeier, W.H.; Smith, D.D. Predicting Rainfall-Erosion Losses: A Guide to Conservation Farming; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Science and Education Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1978.

- Di Lena, B.; Curci, G.; Vergni, L. Analysis of Rainfall Erosivity Trends 1980–2018 in a Complex Terrain Region (Abruzzo, Central Italy) from Rain Gauges and Gridded Datasets. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulano, R.; Rianna, G.; Santini, M. Datasets and Approaches for the Estimation of Rainfall Erosivity over Italy: A Comprehensive Comparison Study and a New Method. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 34, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Peng, X.; Fu, Y.; Gu, Z.; Liang, G.; Miao, C.; Dai, Q. Reveal of Contributing Rainfalls to Annual Soil Erosion and the Response of Runoff Sediment Output: A Case of Zonal Yellow Soil Area. J. Hydrol. 2025, 652, 132666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diodato, N.; Gómara, I.; Baronetti, A.; Fratianni, S.; Bellocchi, G. Reconstruction of Erosivity Density in Northwest Italy since 1701. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2021, 66, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avino, A.; Cimorelli, L.; Furcolo, P.; Noto, L.V.; Pelosi, A.; Pianese, D.; Villani, P.; Manfreda, S. Are Rainfall Extremes Increasing in Southern Italy? J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, D.L.; Ridolfi, E.; Russo, F.; Moccia, B.; Napolitano, F. Climate Change Effects on Rainfall Extreme Value Distribution: The Role of Skewness. J. Hydrol. 2024, 634, 130958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, S.; Seeger, M.; Ries, J.B. Field Experiments for Understanding and Quantification of Rill Erosion Processes. CATENA 2012, 91, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J. Roles of Raindrop Impact in Detachment and Transport Processes of Interrill Soil Erosion. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2023, 11, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.P.C.; Quinton, J.N.; Smith, R.E.; Govers, G.; Poesen, J.W.A.; Auerswald, K.; Chisci, G.; Torri, D.; Styczen, M.E. The European Soil Erosion Model (EUROSEM): A Dynamic Approach for Predicting Sediment Transport from Fields and Small Catchments. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 1998, 23, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, D.C.; Nearing, M.A. USDA Water Erosion Prediction Project: Hillslope Profile and Watershed Model Documentation; NSERL Report No. 10 1995; USDA-ARS National Soil Erosion Research Laboratory: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1995.

- Pampalone, V.; Nicosia, A.; Palmeri, V.; Serio, M.A.; Ferro, V. Rill and Interrill Soil Loss Estimations Using the USLE-MB Equation at the Sparacia Experimental Site (South Italy). Water 2023, 15, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.; Schulze, M.; Rieke-Zapp, D.; Schlunegger, F. Rill Development and Soil Erosion: A Laboratory Study of Slope and Rainfall Intensity. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2010, 35, 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zheng, F.; Wen, L.; Han, Y.; Hu, W. Impacts of Rainfall Intensity and Slope Gradient on Rill Erosion Processes at Loessial Hillslope. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 155, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tu, N.; Cen, L.; Gan, F.; Dai, Q.; Mei, L. Characteristics and Dynamic Mechanism of Rill Erosion Driven by Extreme Rainfall on Karst Plateau Slopes, SW China. CATENA 2024, 238, 107890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Li, P.; Xu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ren, Z.; Zhou, S.; Lu, K. The Response of Slope Hydrodynamics and Rill Development to Erosion in the Water-Wind Erosion Crisscross Region of the Loess Plateau, China. CATENA 2025, 261, 109590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, B.; Nearing, M.A. Practical Thresholds for Separating Erosive and Nonerosive Storms. Trans. ASAE 2002, 45, 1843–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todisco, F.; Vergni, L.; Vinci, A.; Pampalone, V. Practical Thresholds to Distinguish Erosive and Rill Rainfall Events. J. Hydrol. 2019, 579, 124173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, O.M.M.; Ricci, G.F.; Gentile, F.; De Girolamo, A.M. Modelling the Impact of Climate Change on Runoff and Sediment Yield in Mediterranean Basins: The Carapelle Case Study (Apulia, Italy). Front. Water 2025, 7, 1486644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Vicente, M.; Gómez, J.A.; Guzmán, G.; Calero, J.; García-Ruiz, R. The Role of Cover Crops in the Loss of Protected and Non-Protected Soil Organic Carbon Fractions Due to Water Erosion in a Mediterranean Olive Grove. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 213, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliaume, F.; Rossing, W.A.H.; Tittonell, P.; Jorge, G.; Dogliotti, S. Reduced Tillage and Cover Crops Improve Water Capture and Reduce Erosion of Fine Textured Soils in Raised Bed Tomato Systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 183, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Rejesus, R.M.; Aglasan, S.; Hagen, S.C.; Salas, W. The Impact of Cover Crops on Soil Erosion in the US Midwest. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 324, 116168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendrich, A.N.; Matthews, F.; Van Eynde, E.; Carozzi, M.; Li, Z.; d’Andrimont, R.; Lugato, E.; Martin, P.; Ciais, P.; Panagos, P. From Regional to Parcel Scale: A High-Resolution Map of Cover Crops across Europe Combining Satellite Data with Statistical Surveys. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiwal, D.; Kumar, S.; Islam, A.; Kumar, S.; Jat, S.R.; Vaishnav, M.; Dayal, D. Evaluating Effect of Cover Crops on Runoff, Soil Loss and Soil Nutrients in an Indian Arid Region. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2021, 52, 1669–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, J.P.; Quemada, M. Using Cover Crops to Mitigate and Adapt to Climate Change. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergni, L.; Pasquini, N.; Todisco, F. Best Siting for Small Hill Reservoirs and the Challenge of Sedimentation: A Case Study in the Umbria Region (Central Italy). Land 2025, 14, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarquini, S.; Isola, I.; Favalli, M.; Battistini, A.; Dotta, G. TINITALY, a Digital Elevation Model of Italy with a 10 Meters Cell Size, Version 1.1; Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, C.; Pampalone, V.; Todisco, F.; Vergni, L.; Ferro, V. Testing the Universal Soil Loss Equation-MB Equation in Plots in Central and South Italy. Hydrol. Process. 2019, 33, 2422–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todisco, F. The Internal Structure of Erosive and Non-Erosive Storm Events for Interpretation of Erosive Processes and Rainfall Simulation. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 3651–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Borrelli, P.; Spinoni, J.; Ballabio, C.; Meusburger, K.; Beguería, S.; Klik, A.; Michaelides, S.; Petan, S.; Hrabalíková, M.; et al. Monthly Rainfall Erosivity: Conversion Factors for Different Time Resolutions and Regional Assessments. Water 2016, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergni, L.; Vinci, A.; Todisco, F. Influence of the Rainfall Time Step on the Thresholds for Separating Erosive and Non-Erosive Events. In AIIA 2022: Biosystems Engineering Towards the Green Deal; Ferro, V., Giordano, G., Orlando, S., Vallone, M., Cascone, G., Porto, S.M.C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 337, pp. 211–219. ISBN 978-3-031-30328-9. [Google Scholar]

- Piccarreta, M.; Lazzari, M.; Bentivenga, M. The Influence in Rainfall Erosivity Calculation by Using Different Temporal Resolution in Mediterranean Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, K.H. Trend Detection in Hydrologic Data: The Mann–Kendall Trend Test under the Scaling Hypothesis. J. Hydrol. 2008, 349, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Wang, C. The Mann-Kendall Test Modified by Effective Sample Size to Detect Trend in Serially Correlated Hydrological Series. Water Resour. Manag. 2004, 18, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maechler, M.; Rousseeuw, P.; Struyf, A.; Hubert, M. cluster: “Finding Groups in Data”: Cluster Analysis Extended Rousseeuw et al. 1999, Version 2.1.8.1.; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlert, T. trend: Non-Parametric Trend Tests and Change-Point Detection 2015, Version 1.1.6; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, M.; Galli, M.; Guzzetti, F.; Ardizzone, F.; Reichenbach, P.; Bartoccini, P. Rainfall Induced Landslides in December 2004 in South-Western Umbria, Central Italy: Types, Extent, Damage and Risk Assessment. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2006, 6, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, G.H. OROGRAPHIC PRECIPITATION. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2005, 33, 645–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, M.; Barsanti, M.; Raco, B.; Giannecchini, R. Investigating a Century of Rainfall: The Impact of Elevation on Precipitation Changes (Northern Tuscany, Italy). Water 2024, 16, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, G.; Francipane, A.; Noto, L.V. Classification of Extreme Rainfall for a Mediterranean Region by Means of Atmospheric Circulation Patterns and Reanalysis Data. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 3219–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergni, L.; Todisco, F. Bivariate Analysis of Rainfall Characteristics for Identifying Soil Loss Return Periods at the Event Scale. J. Hydrol. 2026, 664, 134605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, A.; Todisco, F.; Vergni, L.; Torri, D. A Comparative Evaluation of Random Roughness Indices by Rainfall Simulator and Photogrammetry. CATENA 2020, 188, 104468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todisco, F.; Vergni, L.; Iovino, M.; Bagarello, V. Changes in Soil Hydrodynamic Parameters during Intermittent Rainfall Following Tillage. CATENA 2023, 226, 107066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zema, D.A. Understanding, Measuring, Mitigating and Modeling Rill Erosion: A Short Review. Earth Environ. Sustain. 2025, 1, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, G.; Poesen, J. Assessment of the Interrill and Rill Contributions to Total Soil Loss from an Upland Field Plot. Geomorphology 1988, 1, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Zheng, F. Understanding Erosion Processes Using Rare Earth Element Tracers in a Preformed Interrill-Rill System. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezak, N.; Ballabio, C.; Mikoš, M.; Petan, S.; Borrelli, P.; Panagos, P. Reconstruction of Past Rainfall Erosivity and Trend Detection Based on the REDES Database and Reanalysis Rainfall. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, V.; Rocco, A.; Annella, C.; Cretella, V.; Fusco, G.; Budillon, G. Signals of Change in the Campania Region Rainfall Regime: An Analysis of Extreme Precipitation Indices (2002–2021). Meteorol. Appl. 2023, 30, e2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppichini, M.; Bini, M. Evolution of Rainfall in Italy over the Last 200 Years: Interactions between Climate Indices and Global Warming. Atmospheric Res. 2025, 326, 108276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Tramblay, Y.; Reig, F.; González-Hidalgo, J.C.; Beguería, S.; Brunetti, M.; Kalin, K.C.; Patalen, L.; Kržič, A.; Lionello, P.; et al. High Temporal Variability Not Trend Dominates Mediterranean Precipitation. Nature 2025, 639, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | PT (mm) | I30 (mm h−1) | D (h) | R (MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1) | Pmax_burst (mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event Type | Mean | CV | Mean | CV | Mean | CV | Mean | CV | Mean | CV | |

| NE | 137,329 | 3.0 | 120% | 2.6 | 122% | 4.2 | 118% | 0.4 | 135% | 2.4 | 124% |

| EE | 23,708 | 28.1 | 53% | 14.5 | 60% | 18.0 | 66% | 4.1 | 63% | 20.2 | 58% |

| RE | 875 | 75.5 | 32% | 30.1 | 43% | 23.3 | 54% | 13.0 | 35% | 64.5 | 25% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vergni, L.; Todisco, F. Assessing Erosion-Triggering Rainfall Patterns in Central Italy: Frequency, Trends, and Implications for Soil Protection. Water 2026, 18, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010044

Vergni L, Todisco F. Assessing Erosion-Triggering Rainfall Patterns in Central Italy: Frequency, Trends, and Implications for Soil Protection. Water. 2026; 18(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleVergni, Lorenzo, and Francesca Todisco. 2026. "Assessing Erosion-Triggering Rainfall Patterns in Central Italy: Frequency, Trends, and Implications for Soil Protection" Water 18, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010044

APA StyleVergni, L., & Todisco, F. (2026). Assessing Erosion-Triggering Rainfall Patterns in Central Italy: Frequency, Trends, and Implications for Soil Protection. Water, 18(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010044