Basic Principles, Approaches, and Instruments for Studying, Characterizing, and Applying Natural and Artificial Fogs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Approaches and Methods for Detection and Characterization of Fogs

2.1. General Classification. In Situ Methods

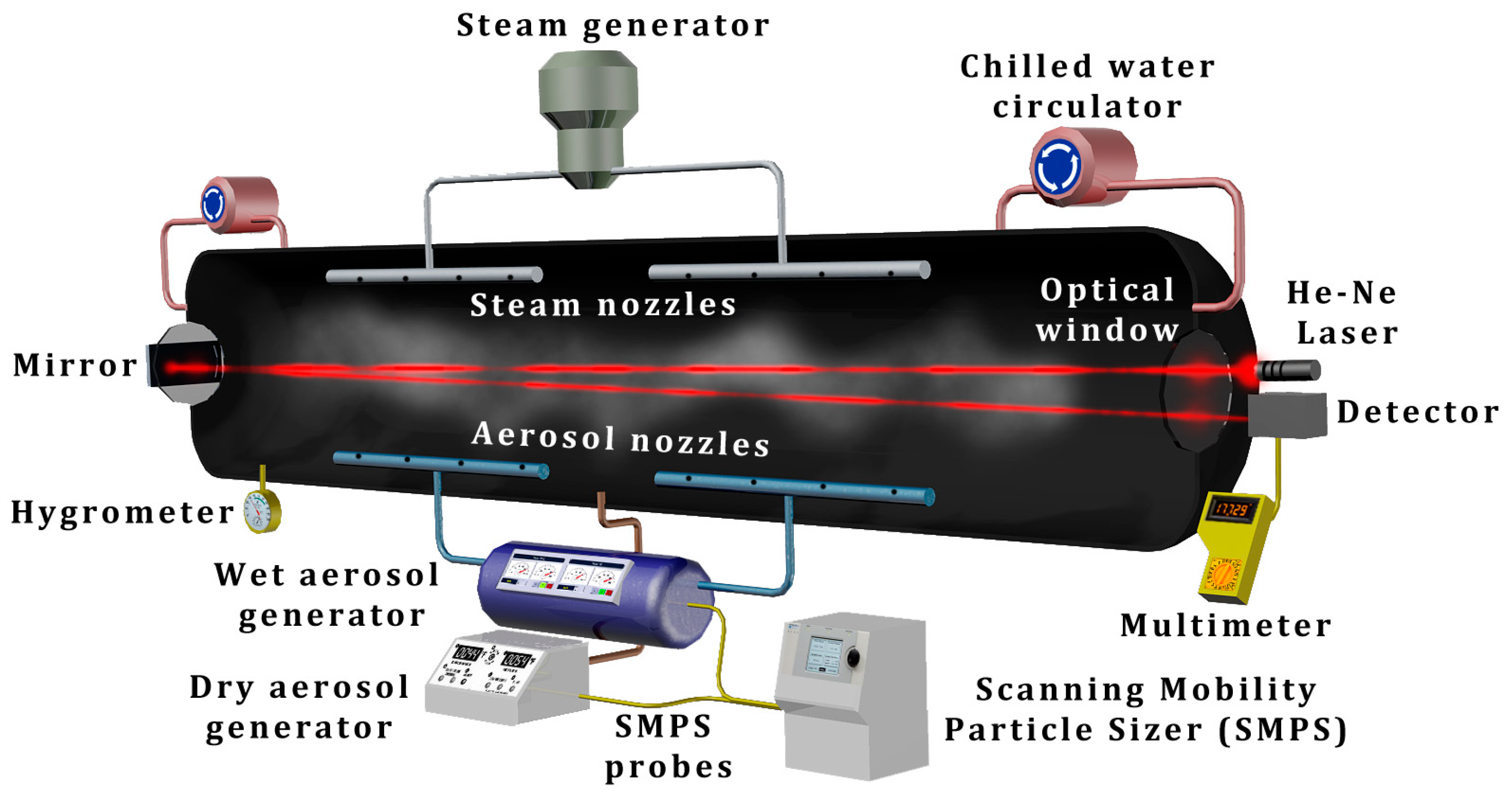

2.2. Generating and Studying Fogs Using Fog Chambers and Field-Deployed Apparatuses

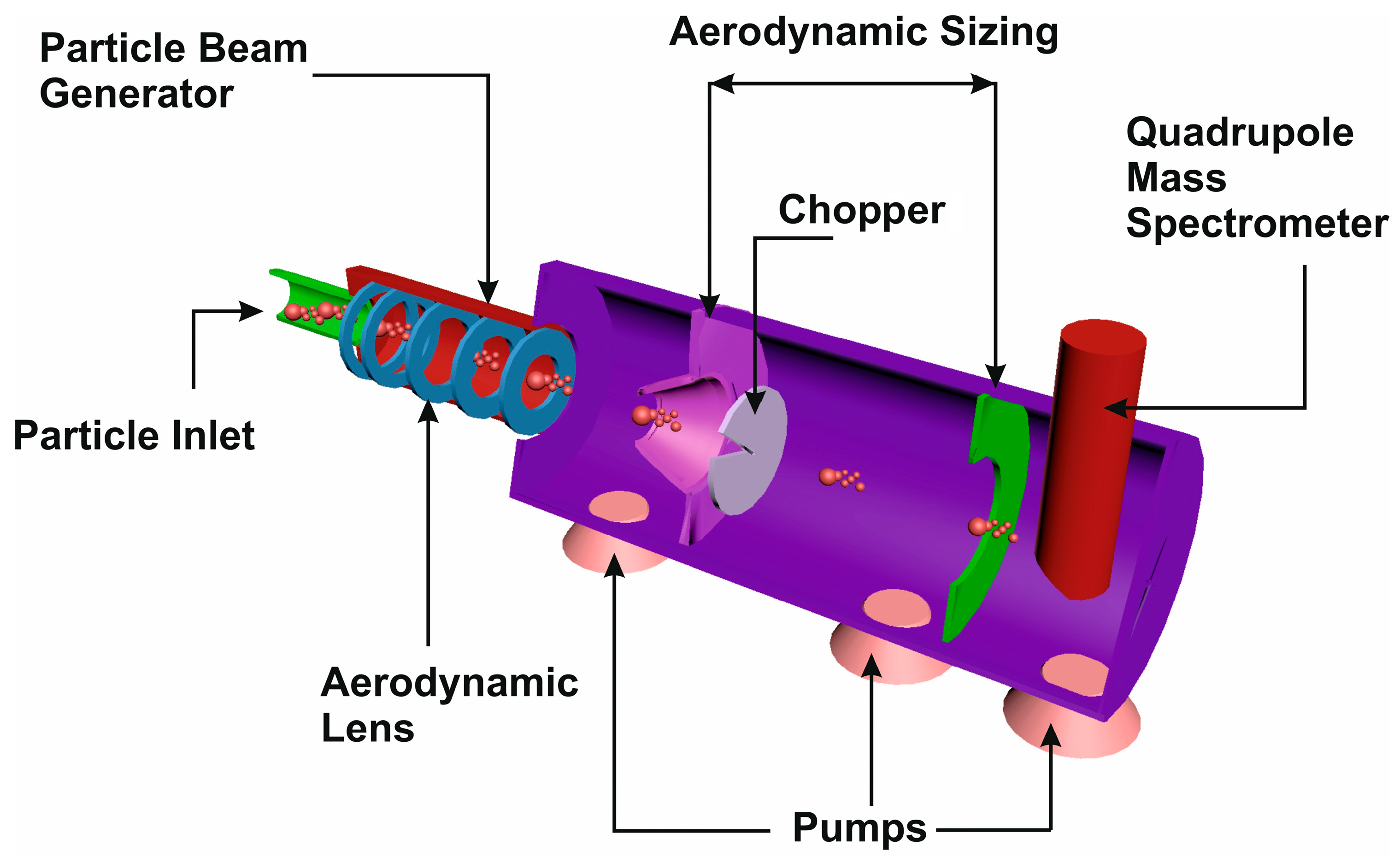

2.3. Mass Spectrometry

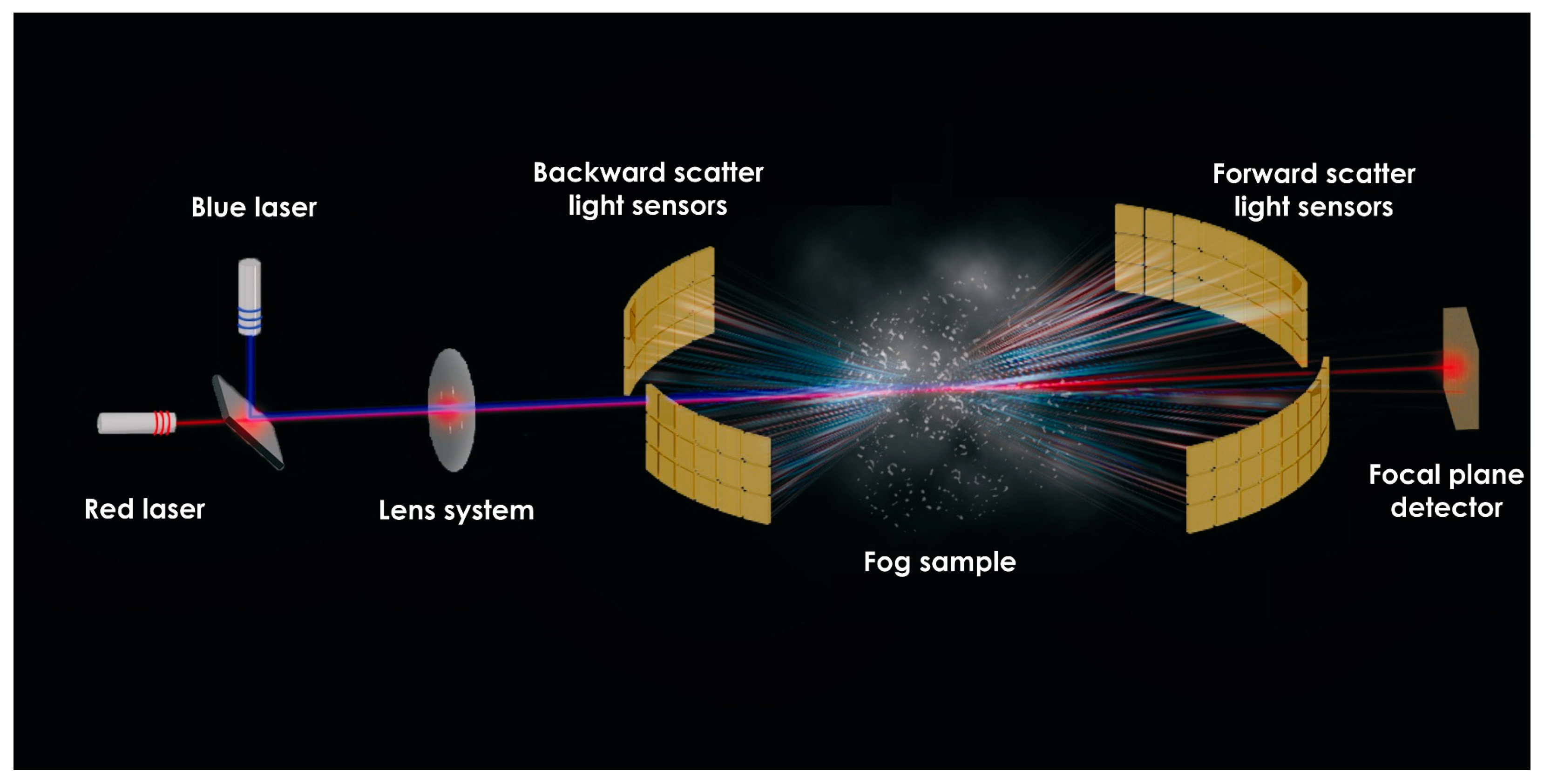

2.4. Fog Characterization Using Light Scattering and Diffraction

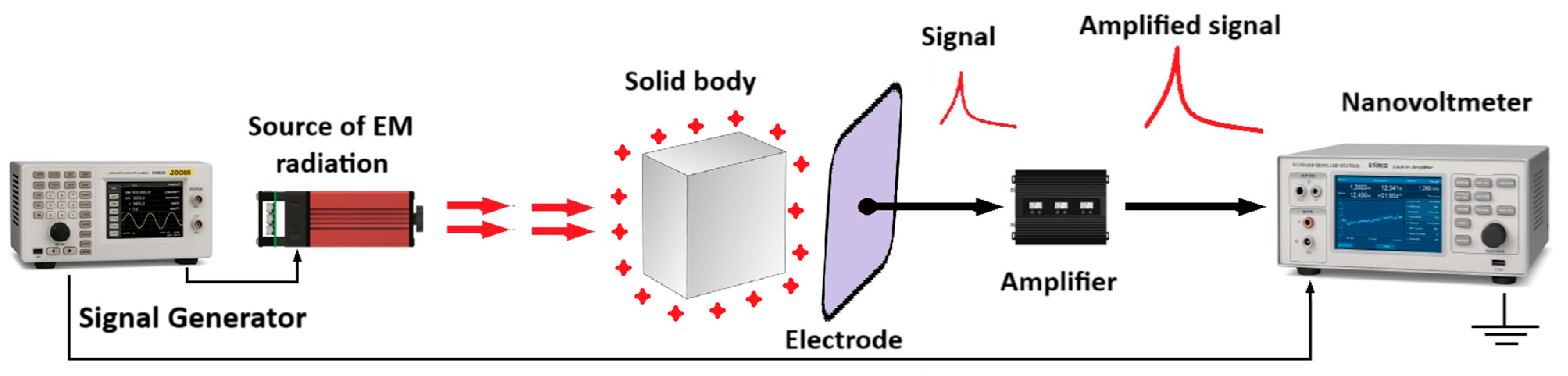

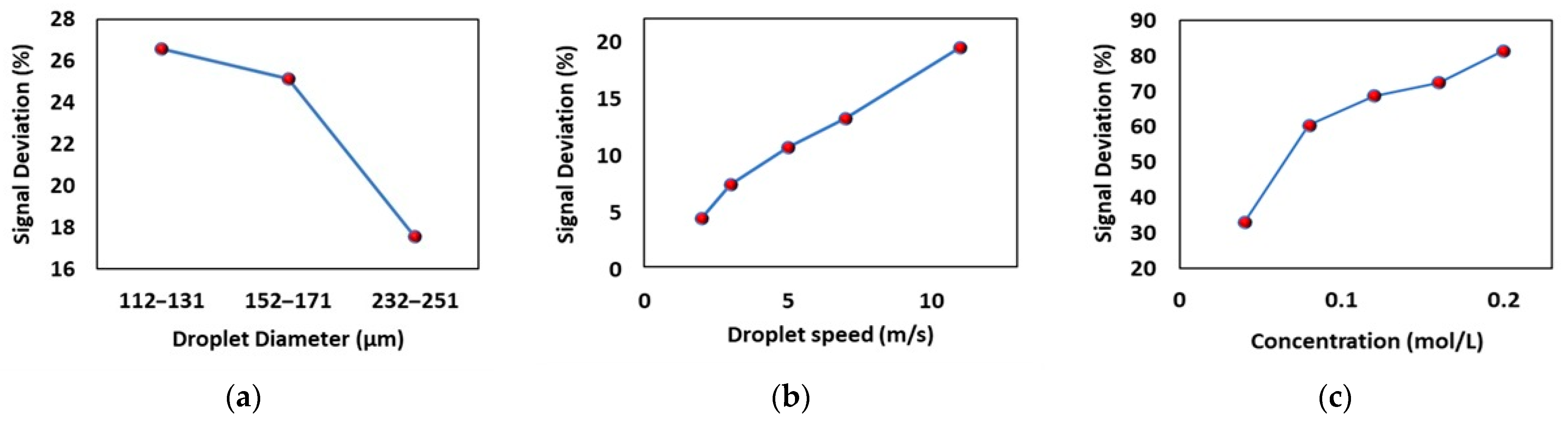

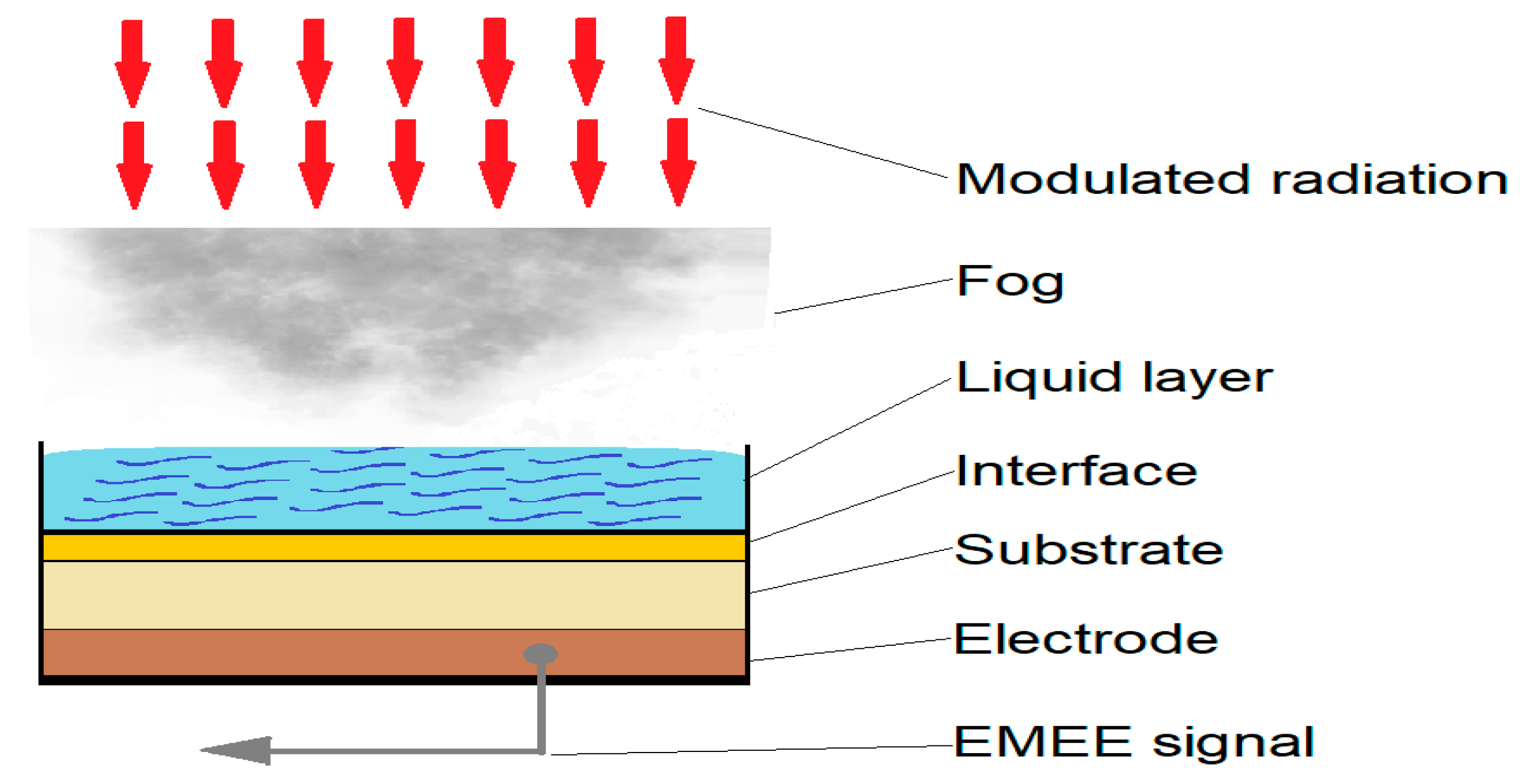

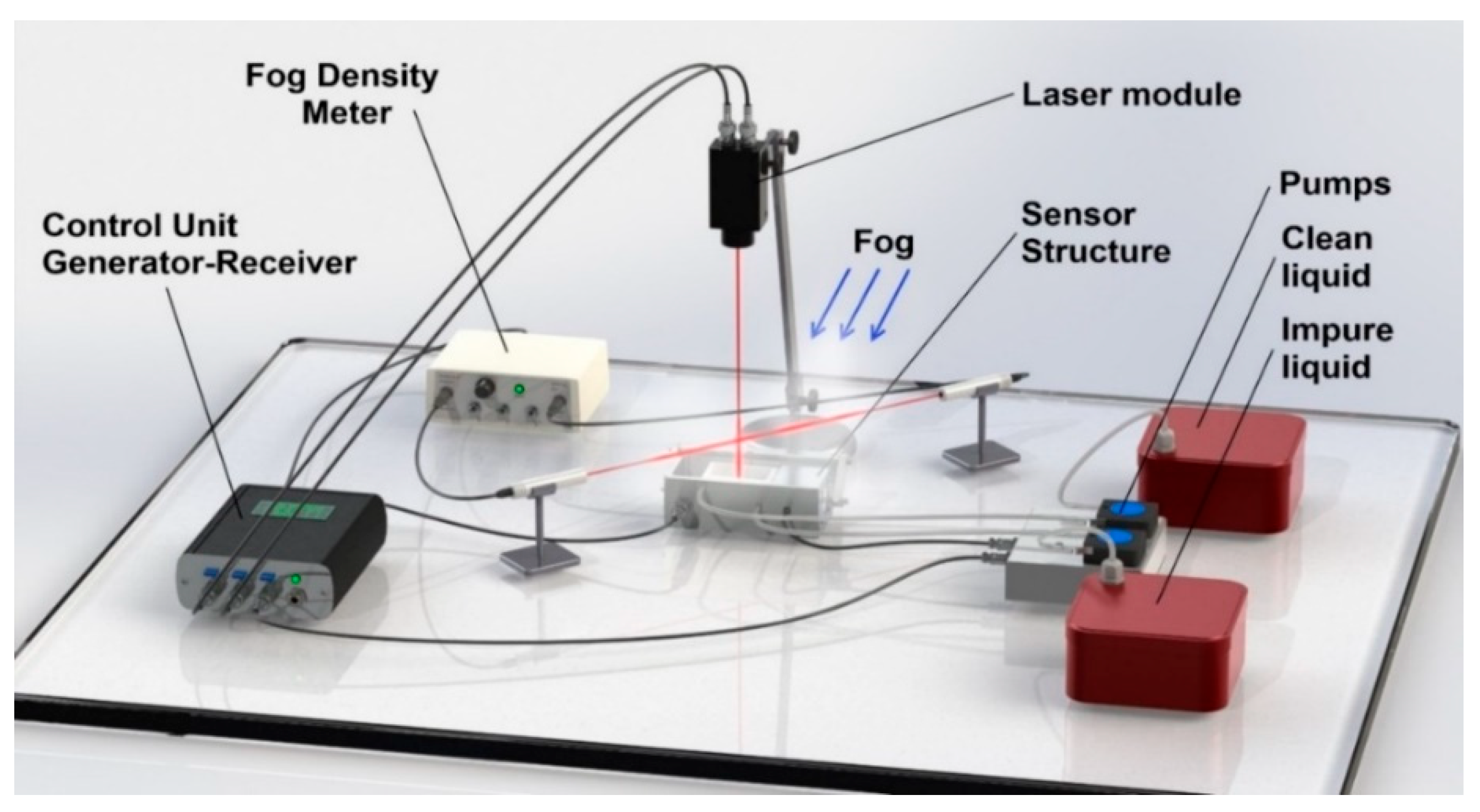

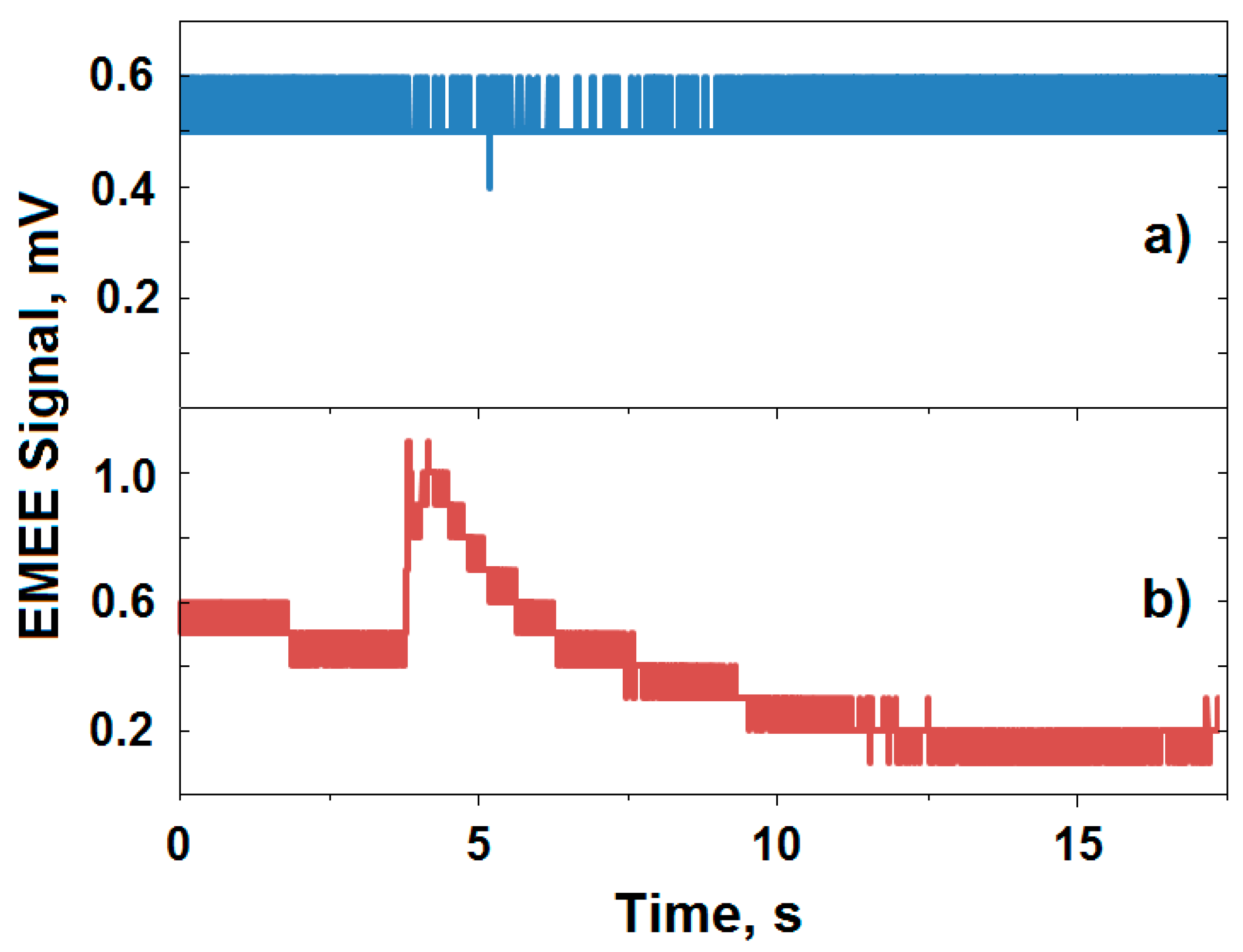

2.5. Applying the Electromagnetic Echo Effect

2.6. Remote Sensing Methods

3. Artificial Fogs: Apparatus for Fog Generation and Characterization

3.1. Fog Machines and Fog Laboratory Systems

3.2. Nebulizers

4. Fog Applications

4.1. Applications of Natural Fogs

4.2. Applications of Artificial Fogs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WMO. International Meteorological Vocabulary; Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Diaz, J.L.; Ivanov, O.; Peshev, Z.; Alvarez-Valenzuela, M.; Valiente-Blanco, I.; Evgenieva, T.; Dreischuh, T.; Gueorguiev, O.; Todorov, P.; Vaseashta, A. Fogs: Physical basis, characteristic properties, and impacts on the environment and human health. Water 2017, 9, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakra, K.; Avishek, K. A Review on Factors Influencing Fog Formation, Classification, Forecasting, Detection and Impacts. Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche Naturali 2022, 33, 319–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, G.; Guo, S.; Zamora, M.L.; Ying, Q.; Lin, Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, M.; Wang, Y. Formation of urban fine particulate matter. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3803–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Y.; Cui, J.; Jiang, P. An observational study of atmospheric ice nuclei number concentration during three fog-haze weather periods in Shenyang, Northeastern China. Atmos. Res. 2017, 188, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, A.K.; Liu, X.; Zhu, T.; Hu, D.L. Fog spontaneously folds mosquito wings. Phys. Fluids 2015, 27, 021901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, R.A.; Cracknell, A.P. (Eds.) Remote Sensing and Global Climate Change; NATO ASI Series, Series I: Global Environmental Change; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, R.; Dios, F. Wireless optical communications through the turbulent atmosphere: A review. In Optical Communications Systems; Das, N., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Kahn, J.M. Free-space optical communication through atmospheric turbulence channels. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2002, 50, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, J.D.; Rea, M.S. Impacts of fog characteristics, forward illumination, and warning beacon intensity distribution on roadway hazard visibility. Sci. World J. 2016, 2016, 4687816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, G.; Gultepe, I.; Milbrandt, J.; Hansen, B.; Pearson, G.; Fogarty, C.; Burrows, W. The Environment Canada Handbook on Fog and Fog Forecasting; Environment Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gultepe, I.; Tardif, R.; Michaelides, S.C.; Cermak, J.; Bott, A.; Bendix, J.; Muller, M.D.; Pagowski, M.; Hansen, B.; Ellrod, G.; et al. Fog research: A review of past achievements and future perspectives. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2007, 164, 1121–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. Aerodrome Reports and Forecasts: A User’s Handbook to the Codes, WMO-No. 782; Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- WMO. Compendium of Lecture Notes for Training Class IV Meteorological Personnel: Meteorology, WMO-No. 266; Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kniveton, D. Encyclopedia of World Climatology—Edited by John E. Oliver. Geogr. J. 2007, 173, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook of Aviation Meteorology; H.M. Stationery Office: London, UK, 1994.

- Li, Y.; Zheng, C.; Ma, Z.; Quan, W. Acute and cumulative effects of haze fine particles on mortality and the seasonal characteristics in Beijing, China, 2005–2013: A time-stratified case-crossover study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. Guide to Meteorological Instruments and Methods of Observations, WMO-No. 8; Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanakumar, K. Stratosphere–Troposphere Interactions: An Introduction; Doe, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Quantitative assessment of traffic accident risk under fog conditions using multi-source data fusion. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 193, 107245. [Google Scholar]

- Costabile, F.; Gilardoni, S.; Barnaba, F.; Di Ianni, A.; Di Liberto, L.; Dionisi, D.; Manigrasso, M.; Paglione, M.; Paluzzi, V.; Rinaldi, M.; et al. Characteristics of brown carbon in the urban Po Valley atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, C.; Duan, J.; Xu, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Kong, L.; Tao, J.; Zhang, R.; et al. Insights into a historic severe haze event in Shanghai: Synoptic situation, boundary layer and pollutants. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 9221–9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, R.; Gomez, M.E.; Yang, L.; Levy Zamora, M.; Hu, M.; Lin, Y.; Peng, J.; Guo, S.; Meng, J.; et al. Persistent sulfate formation from London fog to Chinese haze. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13630–13635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Chen, J. Formation, features and controlling strategies of severe haze-fog pollutions in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 578, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, W.; Nietosvaara, V.; Bott, A.; Bendix, J.; Cermak, J.; Michaelides, S.; Gultepe, I. (Eds.) Short Range Forecasting Methods of Fog, Visibility and Low Clouds, ESSEM COST Action 722 Final Report; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Policarpo, C.; Salgado, R.; Costa, M.J. Numerical simulations of fog events in Southern Portugal. Adv. Meteorol. 2017, 2017, 1276784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultepe, I.; Zhou, B.; Milbrandt, J.; Bott, A.; Li, Y.; Heymsfield, A.J.; Ferrier, B.; Ware, R.; Pavolonis, M.; Kuhn, T.; et al. A review on ice fog measurements and modeling. Atmos. Res. 2015, 151, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultepe, I.; Milbrandt, J.A.; Zhou, B. Marine fog: A review on microphysics and visibility prediction. In Marine Fog: Challenges and Advancements in Observations, Modeling, and Forecasting; Koracin, D., Dorman, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 345–394. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Z.; Chachere, C.N.; Hoch, S.W.; Pardyjak, E.; Gultepe, I. Numerical prediction of cold season fog events over complex terrain: The performance of the WRF model during MATERHORN-fog and early evaluation. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2016, 173, 3165–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, A.; Anurose, T.J.; Bhati, S.; Hendry, M.A.; Hayman, G.; Gordon, H.; Field, P.; Mohandas, S.; Rumbold, H.; Yadav, P.; et al. Development of an integrated modeling framework for visibility and air quality forecasting in Delhi. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, 106, E261–E274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cater, J.; Dunker, C.; MacDonald, M. Direct numerical simulation of fog formation with turbulence and longwave radiation. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2025, 191, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergot, T.; Lestringant, R. On the predictability of radiation fog formation in a mesoscale model: A case study in heterogeneous terrain. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankit, G.; Ajay, B.; Kumar, K.M.; Neetu, K. Tablet coating techniques: Concepts and recent trends. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2012, 3, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Kim, A.K. A review of water mist fire suppression systems: Fundamental studies. J. Fire Prot. Eng. 2000, 10, 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dolovich, M.; Ahrens, R.; Hess, D.; Anderson, P.; Dhand, R.; Rau, J.; Smaldone, G.; Guyatt, G. Device selection and outcomes of aerosol therapy: Evidence-based guidelines. Chest 2005, 127, 335–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikh, S.; Mushtaque, M.; Das, S. A study on the understanding of chemical compositions of deposited fog water over Central Indo-Gangetic Plain in India. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2023, 23, 230098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boris, A.; Napolitano, D.; Herckes, P.; Clements, A.; Collett, J. Fogs and air quality on the Southern California coast. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, J.; Jacob, D.; Munger, J.; Hoffmann, M. Pollutant deposition in radiation fog. In Aerosols and Acid Rain; Lindberg, S.E., Page, A.L., Norton, S.A., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; pp. 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- Du, P.; Nie, X.; Liu, H.; Hou, Z.; Pan, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y. Design and evaluation of ACFC—An automatic cloud/fog collector. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, P.; Ivanov, O.; Gultepe, I.; Agelin-Chaab, M.; Pérez-Díaz, J.; Dreischuh, T.; Kostadinov, K. Optimization of the air cleaning properties of fog. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2024, 8, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, A.; Decesari, S.; Aktypis, A.; Andersen, H.; Baumgardner, D.; Bianchi, F.; Busetto, M.; Cai, J.; Cermak, J.; Dipu, S.; et al. From molecules to droplets: The Fog and Aerosol InteRAction Research Italy (FAIRARI) 2021/22 campaign. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2024, 105, E23–E50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultepe, I.; Fernando, H.J.S.; Pardyjak, E.R.; Hoch, S.W.; Silver, Z.; Creegan, E.; Leo, L.S.; Pu, Z.; De Wekker, S.F.J.; Hang, C. An overview of the MATERHORN fog project: Observations and predictability. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2016, 173, 2983–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.; Gultepe, I. Ice fog and light snow measurements using a high-resolution camera system. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2016, 173, 3049–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, R.C.; Le, T.; Madsen, M.J.; Brown, J. Cloud chamber. Wabash J. Phys. 2015, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Gupta, T.; Tripathi, S.; Jariwala, C.; Das, U. Experimental Study of the Effects of Environmental and Fog Condensation Nuclei Parameters on Rate of Fog Formation and Dissipation Using a New Laboratory Scale Fog Generation Facility. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2011, 11, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, A.; Davidov, V.; Ivanov, V.; Palei, A.; Pisanko, Y. Warm fog artificial dispersion: Preliminary results. J. Atmos. Sci. Res. 2025, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, G.C.; Woo, B.L.; Sanchez, A.L.; Knapp, H. Image quality, meteorological optical range, and fog particulate number evaluation using the Sandia National Laboratories fog chamber. Opt. Eng. 2017, 56, 085104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Shen, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, B.; Ma, Q.; Han, L.; Xu, H.; Hu, X.; Lu, J.; et al. Characterization of fog microphysics and their relationships with visibility at a mountain site in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 3253–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Ralev, Y.; Todorov, P.; Popov, I.; Angelov, K.; Perez-Diaz, J.L.; Kuneva, M. Laboratory system for artificial fog generation with controlled number and size distribution of droplets. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 50, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O.; Ralev, Y.; Todorov, P.; Popov, I.; Perez-Diaz, J.L.; Kuneva, M. System for generation of fogs with controlled impurities. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 50, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Larochelle, V.; Bonnier, D.; Roy, G.; Simard, J.-R.; Mathieu, P. Performance assessment of various imaging sensors in fog. In Enhanced and Synthetic Vision 1998; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1998; Volume 3364, pp. 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Colomb, M.; Hirech, K.; Andre, P.; Boreux, J.J.; Lacote, P.; Dufour, J. An innovative artificial fog production device improved in the European project “FOG”. Atmos. Res. 2008, 87, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viijiiiac, S.N.; Filip, V.; Stefan, S.; Boscornea, A. Assessing the size distribution of droplets in a cloud chamber from light extinction data during a transient regime. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2014, 109, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, H. Direct measurement of suspended particulate volume concentration and far-infrared extinction coefficient with a laser-diffraction instrument. Appl. Opt. 1991, 30, 4824–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, B.G.; Kos, G.P.A.; Wobrock, W.; Schell, D.; Noone, K.J.; Fuzzi, S.; Pahl, S. Comparison of techniques for measurements of fog liquid water content. Tellus B 1992, 44, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallant, R.K.A.M. Poor man’s optical fog detector. Ann. Meteorol. 1988, 25, 333–334. [Google Scholar]

- Collett, J.L.; Daube, B.C.; Hoffmann, M.R. The chemical composition of intercepted cloudwater in the Sierra Nevada. Atmos. Environ. 1990, 24, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuzzi, S.; Cesari, G.; Evangelisti, F.; Facchini, M.C.; Orsi, G. An automatic station for fog water collection. Atmos. Environ. 1990, 24A, 2609–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.H.; Emert, S.E.; Sherman, D.E.; Herckes, P.; Collett, J.L., Jr. An economical optical cloud/fog detector. Atmos. Res. 2008, 87, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canagaratna, M.R.; Jimenez, J.L.; Kroll, J.H.; Chen, Q.; Kessler, S.H.; Massoli, P.; Hildebrandt Ruiz, L.; Fortner, E.; Williams, L.R.; Wilson, K.R.; et al. Elemental ratio measurements of organic compounds using aerosol mass spectrometry: Characterization, improved calibration, and implications. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renbaum-Wolff, L.; Song, M.; Marcolli, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.F.; Grayson, J.W.; Geiger, F.M.; Martin, S.T.; Bertram, A.K. Observations and implications of liquid–liquid phase separation at high relative humidities in secondary organic material produced by α-pinene ozonolysis without inorganic salts. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 7969–7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarikoski, S.; Reyes, F.; Vázquez, Y.; Tagle, M.; Timonen, H.; Aurela, M.; Carbone, S.; Worsnop, D.R.; Hillamo, R.; Oyola, P. Characterization of submicron aerosol chemical composition and sources in the coastal area of Central Chile. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 199, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perraud, V.; Bruns, E.A.; Ezell, M.J.; Johnson, S.N.; Yu, Y.; Alexander, M.L.; Zelenyuk, A.; Imre, D.; Chang, W.L.; Dabdub, D.; et al. Nonequilibrium atmospheric secondary organic aerosol formation and growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2836–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehbein, P.J.G.; Jeong, C.-H.; McGuire, M.L.; Yao, X.; Corbin, J.C.; Evans, G.J. Cloud and fog processing enhanced gas-to-particle partitioning of trimethylamine. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 4346–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Anastasio, C. Free and combined amino (PM2.5) compounds in atmospheric fine particles and fog waters from Northern California. Atmos. Environ. 2003, 37, 2247–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ito, A.; Wang, G.; Zhi, M.; Xu, L.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Wu, F.; Laskin, A. Aqueous-phase secondary organic aerosol formation on mineral dust. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.M. The design of single particle laser mass spectrometers. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2007, 26, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, C.A.; Prather, K.A. Real-time single particle mass spectrometry: A historical review of a quarter century of the chemical analysis of aerosols. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2000, 19, 248–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Miao, R.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Cheng, X.; Liao, K.; Koenig, T.K.; Ge, Y.; Tang, L.; Shang, D.; et al. Secondary formation of submicron and supermicron organic and inorganic aerosols in a highly polluted urban area. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2022JD037865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarikoski, S.; Williams, L.R.; Spielman, S.R.; Lewis, G.S.; Eiguren-Fernandez, A.; Aurela, M.; Hering, S.V.; Teinilä, K.; Croteau, P.; Jayne, J.T.; et al. Laboratory and field evaluation of the Aerosol Dynamics Inc. concentrator (ADIc) for aerosol mass spectrometry. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 3907–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Xie, Q.; Huang, Q.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Hou, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, Z.; et al. Development and characterization of a high-performance single-particle aerosol mass spectrometer (HP-SPAMS). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Ramisetty, R.; Mohr, C.; Huang, W.; Leisner, T.; Saathoff, H. Laser ablation aerosol particle time-of-flight mass spectrometer (LAAPTOF): Performance, reference spectra and classification of atmospheric samples. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 2325–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Hu, Q.; Liu, H.; Tan, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Liu, J. A new method to determine the aerosol optical properties from multiple-wavelength O4 absorptions by MAX-DOAS observation. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 3289–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, M.; He, K.; Zhang, Y. Comparative analysis of aerosol chemical composition using ToF-ACSM and HR-ToF-AMS in a suburban region of China. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 320, 121015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Kuang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, B.; Zhang, X.; Tao, J.; Qiao, H.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y. Hygroscopic growth and activation changed submicron aerosol composition and properties in the North China Plain. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 9387–9399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkatzelis, G.I.; Tillmann, R.; Hohaus, T.; Müller, M.; Eichler, P.; Xu, K.M.; Schlag, P.; Schmitt, S.H.; Wegener, R.; Kaminski, M.; et al. Comparison of three aerosol chemical characterization techniques utilizing PTR-ToF-MS: A study on freshly formed and aged biogenic SOA. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 1481–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidhammer, I.; Flikka, K.; Mikalsen, S.-O.; Martens, L. Computational Methods for Mass Spectrometry Proteomics; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Osto, M.; Harrison, R.M.; Coe, H.; Williams, P. Real-time secondary aerosol formation during a fog event in London. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 2459–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Bi, X.; Chan, L.Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Sheng, G.; Fu, J.; Li, M.; Zhou, Z. Enhanced trimethylamine-containing particles during fog events detected by single particle aerosol mass spectrometry in urban Guangzhou, China. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 55, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubaki, K. Measurements of fine particle size using image processing of a laser diffraction image. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 55, 08RE08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Mihailov, V.; Pustovoit, V.; Abbate, A.; Das, P. Surface photo-charge effect in solids. Opt. Commun. 1995, 113, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustovoit, V.I.; Borissov, M.; Ivanov, O. Surface photo-charge effect in conductors. Solid State Commun. 1989, 72, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Kuneva, M. Quality Control Methods Based on Electromagnetic Field-Matter Interactions. In Application and Experience of Quality Control; Ivanov, O., Ed.; IntechOpen: Vienna, Austria, 2011; pp. 509–536. ISBN 978-953-307-236-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O.; Petrov, M.; Naradikian, H.; Perez-Diaz, J.L. Phase Transition Detection by Surface Photo Charge Effect in Liquid Crystals. Phase Transit. 2018, 91, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Naradikian, H.; Pérez-Díaz, J.L. Contactless Detection of Phase Transition in Liquid Crystal State by Means of Laser Induced Surface Photo-Charge Effect through Measurement of Electrical Signal. Bulgarian Patent Office Application No. 112488, 13 April 2017. (approved 7 October 2020), Registration No. 67179. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O. Level Meter for Liquids Based on the Surface Photo-Charge Effect. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2001, 75, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Todorov, P.; Simeonov, K.; Vaseashta, A.; Kostadinov, K.; Manga, Y. Experimental Control of a Reaction Occurring During the Interaction Between Chicken Anemia Virus (CAV) and Its Corresponding Antibodies Using Electromagnetic Echo Effect. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Manipulation, Manufacturing and Measurement on the Nanoscale (3M-NANO), Changchun, China, 28 July–1 August 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O.; Konstantinov, L. Investigations of liquids by photo-induced charge effect at solid–liquid interfaces. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2002, 86, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Mihailov, V.; Ivanov, O.; Georgiev, V.; Andreev, S.; Pustovoit, V. Contactless characterization of semiconductor devices using surface photocharge effect. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 1992, 13, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Konstantinov, L. Application of the photo-induced charge effect to study liquids and gases. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2000, 7, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Mutafchieva, Y.; Vaseashta, A. Applications of an effect based on electromagnetic field–matter interactions for investigations of water. In Advanced Sensors for Safety and Security; Vaseashta, A., Khudaverdyan, S., Eds.; NATO Science for Peace and Security Series B; Physics and Biophysics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O.; Radanski, S. Application of surface photo charge effect for milk quality control. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, R79–R83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelli, N.; Francis, D.; Abida, R.; Fonseca, R.; Masson, O.; Bosc, E. In-situ measurements of fog microphysics: Visibility parameterization and estimation of fog droplet sedimentation velocity. Atmos. Res. 2024, 309, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Mitova, I.; Pérez-Díaz, J.L.; Yordanova, A. Measurements of speed and diameters of droplets of fogs with devices operating on the basis of the surface photo-charge effect. Secur. Future 2017, 4, 154–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O.; Pérez-Díaz, J.L. Detecting the Presence of Impurities in the Composition of Fogs and Aerosols through Measuring the Electrical Signal Induced by Surface Photo-Charge Effect. Bulgarian Patent Office Application No. 112588, 29 September 2017. (approved 15 October 2020), Registration No. 67186. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O.; Todorov, P.; Pérez-Díaz, J.L. Optimization of the Cleaning Properties of Fog by Means of a Sensor Operating on the Basis of Laser-Induced Photo-Charge Effect by Measuring Electrical Signals. Bulgarian Patent Office Application No. 112601, 20 October 2017. (approved 18 February 2021), Registration No. 67262 B1. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O.; Todorov, P.; Pérez-Díaz, J.L. Contactless Evaluation of the Number and Diameter of Fog Droplets by Gravitational Separation and Measurement of Electrical Signals. Bulgarian Patent Office Application No. 112602, 20 October 2017. (approved 8 October 2020), Registration No. 67164 B1. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O.; Karatodorov, S.; Pérez-Díaz, J.L. Novel electromagnetic sensor for contaminations in fog based on the laser-induced charge effect. In Proceedings of the IEEE SENSORS 2017, Glasgow, UK, 29 October–1 November 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1509–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, O.; Todorov, P.; Nikolova, N. Application of Electromagnetic Charge Effect for Development of Optical Sensors. Acta Mater. Turc. 2020, 4, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu, A.; Hashiguchi, H.; Yamamoto, M.K.; Dhaka, S.K.; Fukao, S. Influence of gravity waves on fog structure revealed by a millimeter-wave scanning Doppler radar. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D07207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendix, J.; Thies, B.; Naufs, T.; Cermak, J. A feasibility study of daytime fog and low stratus detection with TERRA/AQUA-MODIS over land. Meteorol. Appl. 2006, 13, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, J.; Bendix, J. Detecting ground fog from space—A microphysics-based approach. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 3345–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, X.; Xia, Z. Monitoring fog using FY-1D meteorological satellite. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2008, 11, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, J.C.; Haeffelin, M.; Wærsted, E.; Delanoe, J.; Renard, J.B.; Preissler, J.; O’Dowd, C. Evaluation of fog and low stratus cloud microphysical properties derived from in situ sensor, cloud radar and SYRSOC algorithm. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, J.-U.; Cho, J.; Baek, J.; Kim, H.W. A characteristic analysis of fog using CPS-derived integrated water vapour. Meteorol. Appl. 2010, 17, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani, B.; Karalus, S.; Fuchs, J.; Zech, T.; Zara, M.; Cermak, J. Algorithm for continual monitoring of fog based on geostationary satellite imagery. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2025, 18, 1927–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, J.; Bendix, J. Advances in satellite-based fog detection: A review of techniques and applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 298, 113890. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Zhao, D.; Ali, M.A.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, K. Automatic detection of daytime sea fog based on supervised classification techniques for FY-3D satellite. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguedas Chaverri, A.G.; Toppa, R.H.; Tonello, K.C. From climate to cloud: Advancing fog detection through satellite imagery. Climate 2025, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultepe, I.; Pearson, G.; Milbrandt, J.A.; Hansen, B.; Platnick, S.; Taylor, P.; Gordon, M.; Oakley, J.P.; Cober, S.G. The fog remote sensing and modeling field project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2009, 90, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, S.J.; Hansen, C. Investigating urban clear islands in fog and low stratus clouds in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Phys. Geogr. 2008, 29, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshev, Z.Y.; Deleva, A.D.; Dreischuh, T.N.; Stoyanov, D.V. Dynamical characteristics of atmospheric layers over complex terrain probed by two-wavelength lidar. In Proceedings of the 16th International School on Quantum Electronics: Laser Physics and Applications, Nessebar, Bulgaria, 20–24 September 2010; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2011; Volume 7747, p. 77470U. [Google Scholar]

- Peshev, Z.Y.; Dreischuh, T.N.; Toncheva, E.N.; Stoyanov, D.V. Two-wavelength lidar characterization of atmospheric aerosol fields at low altitudes over heterogeneous terrain. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2012, 6, 063581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, D.V.; Grigorov, I.; Kolarov, G.V.; Peshev, Z.Y.; Dreischuh, T.N. LIDAR atmospheric sensing by metal vapor and Nd:YAG lasers. In Advanced Photonic Sciences; Fadhali, M., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 345–374. [Google Scholar]

- Khlystov, A.; Kos, G.P.A.; ten Brink, H.M. A high-flow turbulent cloud chamber. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 1996, 24, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhanivel, D.B.; Velu, A.N.; Palaniappan, B.S. Design and enhancement of a fog-enabled air quality monitoring and prediction system. Sensors 2024, 24, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.A.; Chen, S.; Freer, M.; Korolev, A.; Krueger, S.K.; Murakami, M.; Niedermeier, D.; Ovchinnikov, M.; Schmalfuß, S.; Tian, P.; et al. Scientific directions for cloud chamber research: Instrumentation, modeling, new chambers, and emerging chamber concepts. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, 106, E770–E781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Towards design and development of isothermal cloud chamber for seeding experiments in tropics and testing of pyrotechnic cartridge. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2018, 181, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, O.; Todorov, P.; Gultepe, I. Investigations on the influence of chemical compounds on fog microphysical parameters. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.R. Nebulizers: Principles and performance. Respir. Care 2000, 45, 609–622. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, J.; Todolí, J.L.; Sempere, F.J.; Canals, A.; Hernandis, V. Determination of metals in lubricating oils by flame atomic absorption spectrometry using a single-bore high-pressure pneumatic nebulizer. Analyst 2000, 125, 2344–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.; Maestre, S.; Hernandis, V.; Todolí, J.L. Liquid-sample introduction in plasma spectrometry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2003, 22, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, J.M.; Todolí, J.L.; Hernandis, V.; Mora, J. The role of the nebulizer on the sodium interferent effects in inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2002, 17, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.; Todolí, J.L.; Rico, I.; Canals, A. Aerosol desolvation studies with a thermospray nebulizer coupled to inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry. Analyst 1998, 123, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordera, L.; Todolí, J.L.; Mora, J.; Canals, A.; Hernandis, V. A microwave-powered thermospray nebulizer for liquid sample introduction in inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1997, 69, 3578–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaker, M.; Meher-Homji, C.B.; Mee, T., III. Inlet fogging of gas turbine engines—Part C: Fog behavior in inlet ducts, CFD analysis and wind tunnel experiments. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2002: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Volume 4: Turbo Expo 2002, Parts A and B, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 3–6 June 2002; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 443–455, Paper No. GT2002-30564. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.R. Medical aerosol inhalers: Past, present, and future. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 1995, 22, 374–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhand, R. Nebulizers that use a vibrating mesh or plate with multiple apertures to generate aerosol. Respir. Care 2002, 47, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Di Bitonto, M.G.; Rodriguez Torres, N.M.; Liu, B.; Zanelli, A. Sustainable textile-based building envelopes: Enhancing water and energy efficiency through fog harvesting. In Sustainable Built Environment for People and Society; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Huo, X.; Yan, T.; Wang, P.; Bai, Z.; Chao, J.; Yang, R.; Wang, R.; Li, T. All-in-one hybrid atmospheric water harvesting for all-day water production by natural sunlight and radiative cooling. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 4988–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, O.; Schemenauer, R.S.; Lummerich, A.; Cereceda, P.; Marzol, V.; Corell, D.; van Heerden, J.; Reinhard, D.; Gherezghiher, T.; Olivier, J.; et al. Fog as a fresh-water resource: Overview and perspectives. Ambio 2012, 41, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessehaye, F.; Abdul-Wahab, S.A.; Savage, M.; Kohler, T.; Gherezghiher, T.; Hurni, H. Fog-water collection for community use. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrain, H.; Velasquez, F.; Cereceda, P.; Espejo, R.; Pinto, R.; Osses, P.; Schemenauer, R.S. Fog measurements at the site “Falda Verde” north of Chañaral compared with other fog stations of Chile. Atmos. Res. 2002, 64, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salbitano, F.; Calamini, G.; Certini, G.; Ortega, A.; Pieguidi, A.; Villasante, L.; Caceres, R.; Coaguila, D.; Delgado, M. Dynamics and evolution of tree populations and soil–vegetation relationships in fogscapes: Observations over a period of 14 years at the experimental sites of Mejia (Peru). In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Fog, Fog Collection and Dew, Münster, Germany, 25–30 July 2010; p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Schemenauer, R.S.; Zanetta, N.; Rosato, M.; Carter, V. The Tojquia, Guatemala fog collection project 2006 to 2016. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Fog, Fog Collection and Dew, Wrocław, Poland, 24–29 July 2016; pp. 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- Shanyengana, E.S.; Henschel, J.R.; Seely, M.K.; Sanderson, R.D. Exploring fog as a supplementary water source in Namibia. Atmos. Res. 2002, 64, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, T.A.; Omar, M.E.D.M.; El Gammal, H.A.A. Evaluation of fog and rain water collected at Delta Barrage, Egypt as a new resource for irrigated agriculture. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2017, 135, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, J.; de Rautenbach, C.J. The implementation of fog water collection systems in South Africa. Atmos. Res. 2002, 64, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Wahab, S.A.; Lea, V. Reviewing fog water collection worldwide and in Oman. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2008, 65, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Wahab, S.A.; Al-Damkhi, A.M.; Al-Hinai, H.; Al-Najar, K.A.; Al-Kalbani, M.S. Total fog and rainwater collection in the Dhofar region of the Sultanate of Oman during the monsoon season. Water Int. 2010, 35, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemenauer, R.S.; Bignell, B.; Makepeace, T. Fog collection projects in Nepal: 1997 to 2016. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Fog, Fog Collection and Dew, Wrocław, Poland, 24–29 July 2016; pp. 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Estrela, M.J.; Valiente, J.A.; Corell, D.; Millán, M. Fog collection in the western Mediterranean basin (Valencia region, Spain). Atmos. Res. 2008, 87, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemenauer, R.S.; Osses, P.; Lara, F.; Zywina, C.; Cereceda, P. Fog collection in the Dominican Republic. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Fog and Fog Collection, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 15–20 July 2001; pp. 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, A.; Regalado, C.M.; Guerra, J.C. Quantification of fog water collection in three locations of Tenerife (Canary Islands). Water 2015, 7, 3306–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, A. Fog collection in the natural park of Serra Malagueta: An alternative source of water for the communities. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Fog, Fog Collection and Dew, La Serena, Chile, 22–27 July 2007; pp. 425–428. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, V.; Verbrugghe, N.; Lobos-Roco, F.; del Río, C.; Albornoz, F.; Khan, A.Z. Unlocking the fog: Assessing fog collection potential and need as a complementary water resource in arid urban lands—The Alto Hospicio, Chile case. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1537058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banakar, H.; Sheikhzadeh, M.; Ghane, M.; Hejazi, S.M.; Hajrasouliha, J. Investigating the efficiency of textile fog-collectors on the basis of fiber parameters. J. Text. Inst. 2014, 105, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michna, P.; Schenk, J.; Werner, R.A.; Eugster, W. MiniCASCC—A battery driven fog collector for ecosystem research. Atmos. Res. 2013, 128, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemenauer, R.S.; Cereceda, P. A proposed standard fog collector for use in high-elevation regions. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1994, 33, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemenauer, R.S.; Joe, P.I. The collection efficiency of a massive fog collector. Atmos. Res. 1989, 24, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martikainen, A.L. Fog removal with a fog mesh—Mist eliminators and multiple mesh systems. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2007, 21, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorur, R.S.; Cherney, E.A.; Hackman, R.; Orbeck, T. The electrical performance of polymeric insulating materials under accelerated aging in a fog chamber. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1988, 3, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorur, R.S.; Chang, J.W.; Amburgey, O.G. Surface hydrophobicity of polymers used for outdoor insulation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1990, 5, 1923–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebo, S.A.; Zhao, T. Utilization of fog chambers for non-ceramic outdoor insulator evaluation. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 1999, 6, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hag, A.; Meyer, L.H.; Naderian, A. Experience with salt-fog and inclined-plane tests for aging polymeric insulators and materials. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 2010, 26, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, I.; Hartings, R.; Matsuoka, R.; Kondo, K. Experience with IEC 1109 1000 h salt fog ageing test for composite insulators. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 1997, 13, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. Practical Course in Atmospheric Physics: Continuous Cloud Chamber; Swiss Federal Institute of Technology: Zurich, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhold, P.R. Water Vapor Measurement: Methods and Instrumentation; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 0824793196. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Diaz, J.L.; Alvarez-Valenzuela, M.A.; Garcia-Prada, J.C. The effect of the partial pressure of water vapor on the surface tension of the liquid water–air interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 381, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Diaz, J.L.; Alvarez-Valenzuela, M.A.; Valiente-Blanco, I.; Jimenez-Lopez, S.; Palacios-Cuesta, M.; Garcia, O.; Diez-Jimenez, E.; Sanchez-Garcia-Casarrubios, J.; Cristache, C. On the influence of relative humidity on the contact angle of a water droplet on a silicon wafer. In Proceedings of the ASME 2013 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition (IMECE2013), Volume 7A: Fluids Engineering Systems and Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 15–21 November 2013; Paper No. IMECE2013-63781. p. V07AT08A027. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Diaz, J.L.; Alvarez-Valenzuela, M.A.; Sanchez-Garcia-Casarrubias, J.; Jimenez-Lopez, S. Ice surface entropy induction by humidity or how humidity prompts freezing. J. Multidiscip. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2016, 3, 3825–3828. [Google Scholar]

- Batcha, M.M.; Hussin, A.; Raghavan, V. Engine cylinder head cooling enhancement by mist cooling—A simulation study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mechanical & Manufacturing Engineering (ICME2008), Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 21–23 May 2008; ISBN 97-98-2963-59-2. [Google Scholar]

- Arbel, A.; Yekutieli, O.; Barak, M. Performance of a fog system for cooling greenhouses. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1999, 72, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.N.; Ayyaswamy, P.S. Laminar condensation heat and mass transfer to a moving drop. AIChE J. 1981, 27, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ayyaswamy, P.S. Heat transfer of a nuclear reactor containment spray drop. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1987, 101, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, P.; Porcheron, E. Study of heat and mass transfers in a spray for containment application: Analysis of the influence of the spray mass flow rate. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2009, 239, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, P.; Tartarini, P. Fire control and suppression by water-mist systems. Open Thermodyn. J. 2010, 4, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P.; Bergman, T.L.; Lavine, A.S. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 0471457280. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, D. An Introduction to Fire Dynamics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Naldi, L.; D’Ercole, M. Effects of a water-mist fire protection system on integrity and operation of heavy-duty gas turbine. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fifth Turbomachinery Symposium, Houston, TX, USA, 25–28 September 2006; pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN 615; Fire Protection—Fire Extinguishing Media—Specifications for Powders (Other than Class D Powders). DIN: Berlin, Germany, 2009.

- Ingram, J.M.; Averill, A.F.; Battersby, P.; Holborn, P.G.; Nolan, P.F. Suppression of hydrogen/oxygen/nitrogen explosions by fine water mist containing sodium hydroxide additive. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 8002–8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattaway, A.; Gall, R.; Spring, D.J. Dry chemical extinguishing systems. In Proceedings of the 1997 Halon Options Technical Working Conference, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 6–8 May 1997; pp. 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Lene, M. Nebulized medications in respiratory disease management: Current trends and future directions. J. Clin. Respir. Med. 2024, 8, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, R.; Zou, C.; Yang, X.; Zhuang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Hu, J.; Liao, L.; Yao, Y.; Sun, X.; et al. Nebulized inhalation drug delivery: Clinical applications and advancements in research. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 3, 821–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, M.M.; Pavia, D.; Newman, S.P.; Clarke, S.W. Factors influencing the size distribution of aerosols from jet nebulisers. Thorax 1983, 38, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, G.D.; Dufour, N.F.; Hummerick, M.E.; Spencer, L.E.; Smith, T.M.; Romeyn, M.W.; Morrow, R.C.; Wheeler, R.M.; Khodadad, C.L.; Gooden, J.L.; et al. eXposed Root On-Orbit Test System (XROOTS): Demonstrating aeroponic crop production aboard the International Space Station. Acta Hortic. 2025, 1382, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Diaz, J.L.; Qin, Y.; Ivanov, O.; Quinones, J.; Stengl, V.; Nylander, K.; Hornig, W.; Álvarez, J.; Ruiz Navas, E.M.; Manzanec, K. Fast response CBRN high-scale decontamination system: COUNTERFOG—Science as the first countermeasure for CBRNE and cyber threats. In Enhancing CBRNE Safety & Security; Malizia, A., D’Arienzo, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 61–69. [Google Scholar]

| Particle Size | Visibility (MOR) | Relative Humidity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fog | 5–50 µm [12] | <1 km [13] | Generally near 100% [14] |

| Mist | ~10 µm [15] | 1~5 km [13] | >95%, generally <100% [13,16] |

| Haze | ≤2.5 µm [17] | ≤5 km [13] | <80% [18] |

| Smoke | 0.01–1 µm [19] | <5 km <1 km if RH < 90% [13] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Todorov, P.; Ivanov, O.; Peshev, Z.; Pérez-Díaz, J.L.; Dreischuh, T.; Sánchez García Casarrubios, J.; Vaseashta, A. Basic Principles, Approaches, and Instruments for Studying, Characterizing, and Applying Natural and Artificial Fogs. Water 2026, 18, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010029

Todorov P, Ivanov O, Peshev Z, Pérez-Díaz JL, Dreischuh T, Sánchez García Casarrubios J, Vaseashta A. Basic Principles, Approaches, and Instruments for Studying, Characterizing, and Applying Natural and Artificial Fogs. Water. 2026; 18(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleTodorov, Petar, Ognyan Ivanov, Zahary Peshev, José Luis Pérez-Díaz, Tanja Dreischuh, Juan Sánchez García Casarrubios, and Ashok Vaseashta. 2026. "Basic Principles, Approaches, and Instruments for Studying, Characterizing, and Applying Natural and Artificial Fogs" Water 18, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010029

APA StyleTodorov, P., Ivanov, O., Peshev, Z., Pérez-Díaz, J. L., Dreischuh, T., Sánchez García Casarrubios, J., & Vaseashta, A. (2026). Basic Principles, Approaches, and Instruments for Studying, Characterizing, and Applying Natural and Artificial Fogs. Water, 18(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010029