1. Introduction

Environmental models play a fundamental role in simulating complex real-world processes and supporting ecological and geographic information systems [

1,

2]. Among these, hydrological models, which simulate the flow of water within a given region, are particularly significant for applications such as urban stormwater management [

3,

4] and flood prediction [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Real-time simulation of hydrological models is crucial in various application scenarios. For instance, real-time calibration of hydrological models requires integrating real-time observation data to enhance model accuracy [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Additionally, real-time modeling is essential for visualizing water resources, enabling dynamic management, and supporting real-time decision-making in different scenarios [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The swift progress of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies has enhanced access to real-time environmental data streams [

19]. IoT devices, with their low power consumption and continuous operation capability, provide ideal inputs (e.g., rainfall, temperature) for driving hydrological models. Integrating these real-time observations enables dynamic, observation-driven hydrological simulation [

20], a cornerstone for digital twin systems [

21]. However, the prevailing execution paradigm of most hydrological models fundamentally impedes the effective utilization of such real-time data. Most widely used hydrological modeling systems follow a batch-oriented, time-step execution workflow involving initialization, sequential simulation, and final output generation [

22,

23]. For instance, the Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) operates on a desktop-based workflow in which users provide static configuration and time-series input files before executing the model in non-interactive batch mode [

24]. During simulation, users cannot inspect internal model states, such as the water depth of a specific node at a particular time step, until the entire run is completed. Even standardized environmental modeling interfaces such as the Open Modelling Interface (OpenMI) adhere to this run-centric paradigm, emphasizing start/stop control and bulk output retrieval rather than real-time access to evolving internal states [

25].

These constraints lead to two fundamental limitations. First, fine-grained observability is not possible: the internal dynamics of the hydrological system remain opaque during execution. Second, real-time data assimilation is infeasible: newly arriving sensor observations cannot influence an ongoing simulation. This “black-box” nature significantly restricts applications that require situational awareness, continuous monitoring, and adaptive control, such as urban flood management and real-time hydrological regulation systems [

26].

Addressing these limitations requires a shift from conventional process-oriented execution to an object-oriented modeling paradigm. By representing each hydrological entity (e.g., subcatchments, nodes, conduits) as an independently addressable digital object with its own state and behavior, the internal dynamics of the simulation become fully observable and externally accessible. Such fine-grained representation enables real-time querying, state modification, and event-driven interactions—capabilities essential for integrating real-time observations into active simulations.

Achieving seamless interoperability with the IoT ecosystem further requires adopting standardized, interoperable IoT data models. The OGC SensorThings API provides a unified conceptual model for representing physical and virtual entities, sensors, observations, and metadata, along with native support for MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport) based data streaming [

27]. Mapping object-oriented hydrological model components onto SensorThings entities allows hydrological models to participate as first-class objects within IoT infrastructures, enabling real-time data exchange and paving the way for end-to-end real-time hydrological systems.

To overcome the above challenges, this study proposes an integrated, IoT-enabled, object-oriented hydrological modeling framework consisting of three components. (1) We develop generic, object-oriented information models that represent hydrological entities as stateful digital objects, enabling fine-grained access to internal modeling processes. (2) We map these hydrological entities to standardized IoT concepts defined by SensorThings API, thereby supporting real-time observation ingestion and interoperable data communication. (3) We implement a prototype system to validate the feasibility and functionality of the proposed framework, demonstrating real-time model interaction, observation-driven simulation, and result visualization.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces some background concepts and related work.

Section 3 presents the research case of this paper, aiming to introduce our research methods.

Section 4 presents the method for integrating the hydrological model service with the sensor network. In

Section 5, we introduce the design and implementation of the prototype system.

Section 6 discusses the contributions of the proposed method, including its advantages and limitations. Finally,

Section 7 provides our conclusions.

2. Related Work

Traditionally, many hydrological models, such as SWMM, have been primarily designed for desktop environments. These models are often deployed on client devices, requiring users to manually input data and run simulations. This design tends to be process-oriented, with proprietary data formats for both inputs and outputs, which limits their ability to be shared as web services and hinders their application in real-time hydrological modeling. This study reviews various related works, including research findings and open standards, to address the limitations of hydrological models in terms of shareability and real-time performance.

2.1. Related Research on Interoperable Sharing of Hydrologic Modeling

There has been some research into custom implementation-based frameworks that enable serviced sharing of hydrological models. For example, the WEB-SWMM designed by Zeng et al. is a web framework based on Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) [

28]. This framework provided fast and reliable real-time computation services for urban water management and served as a methodological reference for publishing and sharing other hydrological models as web services. Gan et al. presented a methodology for publishing hydrological models as web services and integrating an online data-sharing system [

29]. This approach allowed users to model, modify, share, and reuse hydrological models in an online environment, significantly improving their interoperability and facilitating collaboration. In addition, several model services sharing approaches based on relevant service standards achieve consistent model interoperability, further enhancing model sharing and integration. For instance, Tan et al. investigated a generalized strategy based on the OGC WPS (Web Processing Service) standard to enable the publication of the inundation analysis model as a service, facilitating its invocation in a standardized way [

30]. The above achievements have demonstrated the effectiveness of utilizing existing standards to publish models as standardized web services, unifying methods for model invocation as well as input and output structures. By adopting this approach, the heterogeneity of different models has been effectively abstracted, simplifying their integration and reuse.

In addition, component-based hydrological model encapsulation methods can further standardize model invocation and reduce the complexity of integrating hydrological model services with other software systems. For example, Peckham et al. implemented the integration of environmental models and geoprocessing systems using the CSDMS (Community Surface Dynamics Modeling System) standard framework, offering a unified approach to model interoperability that is equally applicable to hydrological models [

31]. Furthermore, Zhang et al. developed a model interoperability engine to enable seamless interaction between hydrological models across various component frameworks such as OpenMI and OpenGMS (Open Geographic Modeling and Simulation) [

32], significantly enhancing the interoperability and integration capabilities of hydrological models. Each of these hydrological model encapsulation approaches, based on standard component frameworks, provides a simpler and more flexible interoperability mechanism, facilitating the seamless integration of hydrological models into other software systems such as the Internet of Things and digital twin platforms.

Although existing research has achieved service-oriented or standard component-based encapsulation of hydrological models to enhance interoperability, limitations remain—particularly in the inability to flexibly and finely access the internal state of these models. The traditional execution of hydrological models typically follows a process-oriented paradigm, where data is input, the model is executed, and the results are output. Many custom framework-based and even component-based approaches for building hydrological modeling services adopt this paradigm, driving the model through sequential execution processes. Furthermore, service encapsulation methods based on standardized specifications such as OGC WPS adopt unified objects to describe models and data—for example, the Process object represents the hydrological model, while the Job object describes the execution process of the model. However, the invocation method of the Process object still follows a process-oriented approach, where users can only run the model online and retrieve the final results. This design makes it difficult to access the intermediate states of the model at a fine granularity—such as obtaining flow rates at specific outlets at a given time step—which limits the flexibility of model interoperability.

2.2. Related Research on Real-Time Interoperability of Hydrologic Models and Observations

Despite the progress made in enhancing the interoperability and reusability of hydrological models, previous studies remain limited in enabling real-time modeling. Integrating hydrological models with sensor networks, rather than relying on archived data, offers an effective approach to drive models in real-time. Several studies have advanced this field significantly. For instance, Shangguan et al. coupled environmental models with sensor network flow data using Apache Spark stream processing and MapReduce, validating the integration with a runoff model [

33]. This advancement has expanded the capability of hydrological models, allowing for real-time data inputs and enabling real-time hydrologic modeling.

Moreover, integrating IoT devices for real-time data acquisition and processing using publish-subscribe network protocol has proven to be another viable solution for real-time modeling. For example, Herle et al. developed GeoPipe, which combines the WPS specification with the Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) protocol to enable real-time sensor data acquisition and geoprocessing [

34]. Additionally, Stasch et al. integrated geoprocessing services with sensor networks for real-time dam monitoring based on the OGC WPS and SOS specifications [

35]. By coupling hydrological modeling or geoprocessing services with IoT sensors, these studies demonstrate real-time observation data-driven hydrological modeling or geoprocessing, significantly improving the real-time performance of the system. Although some of these studies do not directly involve hydrological models, they provide valuable references for approaches to real-time observational data-driven hydrological modeling.

The major shortcoming of these studies is the limited real-time modeling capability of hydrological models, as well as the absence of a unified mechanism for accessing real-time observational data. Most existing studies on coupling sensor networks focus on leveraging observational data for real-time geoprocessing, while relatively few have explored real-time hydrological modeling. Furthermore, although some studies have achieved the integration of hydrological models with sensor networks to enable real-time modeling, these approaches are often based on custom frameworks, without adhering to standardized IoT specifications. As a result, they lack a unified method for data access and expression, which hinders interoperability and broader adoption.

3. Study Area

To ground the methodological development in a practical setting, this study employs the Storm Water Management Model version 5 (SWMM5) as a motivating case to demonstrate and evaluate the feasibility of the proposed approach. SWMM is a widely used rainfall–runoff simulation tool capable of representing hydrologic and hydraulic processes in urban drainage systems, including subcatchment runoff, conduit flow, and water levels within hydraulic networks.

The study area used in this research is shown in

Figure 1 and corresponds to Fredericksburg, a compact urbanized region located in Virginia, USA. The model configuration includes 74 subcatchments, 156 conduits (links), and 156 junction nodes, forming a continuous rainfall–runoff simulation system [

36]. Precipitation data used for the model are obtained from the HydroShare repository, while the rainfall inputs are fed into the system through a SWMM RainGage object.

This case study provides a representative urban drainage environment in which real-time situational awareness and dynamic simulation control would be highly desirable. However, conventional SWMM workflows operate in a batch-oriented manner, preventing real-time inspection of model states or assimilation of new observations. These limitations highlight the need for a more flexible modeling framework that supports fine-grained, real-time access to hydrological components.

In this study, the SWMM-based case serves not only as an application scenario but also as a platform to demonstrate the core ideas of the proposed framework. Within the model, all hydrological components—such as subcatchments, junctions, and conduits—are represented using an object-oriented, fine-grained structure that enables real-time access to internal states during simulation. On the client side, both the ingestion of real-time observational data and the subscription to model outputs are handled through a unified SensorThings API interface. This consistent data model allows external systems to interact with the hydrological model in a standardized manner, supporting real-time monitoring, dynamic control, and seamless integration with IoT data streams.

4. Methods

In this study, we first propose a generic hydrological model representation framework based on the object-oriented paradigm, enabling the fine-grained representation of hydrological models through structured and modular design. Subsequently, the object-oriented hydrological model is mapped to the SensorThings API conceptual model, achieving standardized integration of hydrological models with IoT systems. Finally, we design a set of processes that enable observation data-driven real-time hydrological modeling, supporting real-time, fine-grained access to the hydrological modeling status and simulation results.

4.1. Object-Oriented Modeling Methods for Hydrological Model

4.1.1. Abstract Classification Framework of Hydrologic Model Based on Object-Oriented Paradigm

A hydrological model can be built and run in two parts: the system’s structural components and the data. The components make up the virtual hydrological system in the hydrological model, such as watersheds are defined as entities capable of receiving precipitation, while hydrological facilities like conduits, are responsible for directing water flow. Meanwhile, the data drives the operation of the hydrological model and as model outputs. This includes both observational data, such as precipitation and temperature inputs, and simulated process data generated by the hydrological model, such as runoff or water levels.

We construct an information model for the hydrological model based on an object-oriented paradigm, structured along two key dimensions: the simulation element components and the associated data. This design supports modular invocation and enables fine-grained interaction with the internal elements and states of the hydrological model. Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm that focuses on the use of classes and objects, which contain both fields and methods [

37]. By abstracting entities and functions through an object-oriented approach, software systems can be constructed in a more structured and modular way, facilitating easier invocation and interaction between system components. These advantages have led to the widespread adoption of object-oriented modeling in various simulation and modeling domains [

38].

Drawing on the conceptual models embedded in various commonly used hydrological models, our proposed information model also focuses on the two key perspectives of model components and data. Accordingly, we establish a set of unified abstract classes for their representation, as summarized in

Table 1.

The classification framework described above provides a universal basis for categorizing hydrological models, which can be further developed using object-oriented programming (OOP) principles. By applying OOP languages, we can define concrete classes for each hydrological component identified in the framework, allowing them to inherit from the respective abstract classes. The object-oriented approach not only simplifies the model’s use and customization but also enhances its modularity, making it more adaptable and maintainable within different software environments.

4.1.2. Supporting Real-Time Data Streams via Reactive Streams

Although the object-oriented paradigm provides a structured representation of hydrological models, traditional request-response APIs suffer from inefficiency and poor real-time performance when accessing internal model states. In scenarios involving numerous model elements and high-frequency outputs, users must repeatedly invoke the model’s library API to retrieve up-to-date simulation results—a process that is both cumbersome and latency-prone.

To address this limitation, we integrate the Reactive Streams specification into the object-oriented modeling framework. Reactive Streams is a standard for asynchronous stream processing with non-blocking backpressure, enabling consumers to subscribe to data streams rather than actively pull data [

39].

In our approach, the dynamic outputs of each hydrological object—such as runoff from a Subcatchment or water depth at a Junction—are encapsulated as independent reactive streams. Users can subscribe only to the streams of interest, and the system automatically pushes updated values after each simulation time step. For instance, a flood monitoring application may subscribe solely to the waterDepth stream of critical junctions, ignoring irrelevant model outputs.

This publish-subscribe, asynchronous data flow mechanism not only enhances real-time responsiveness and reduces client-side complexity but also aligns naturally with IoT communication paradigms. In particular, it integrates seamlessly with the MQTT protocol supported by the SensorThings API, enabling hydrological simulation results to be published directly into IoT data streams. This lays the groundwork for end-to-end real-time systems that couple observation, simulation, and actuation.

4.2. Mapping of Hydrological Models to the SensorThings API Standard

The OGC SensorThings API standard provides a unified framework for connecting and representing IoT devices, data, and applications over the web [

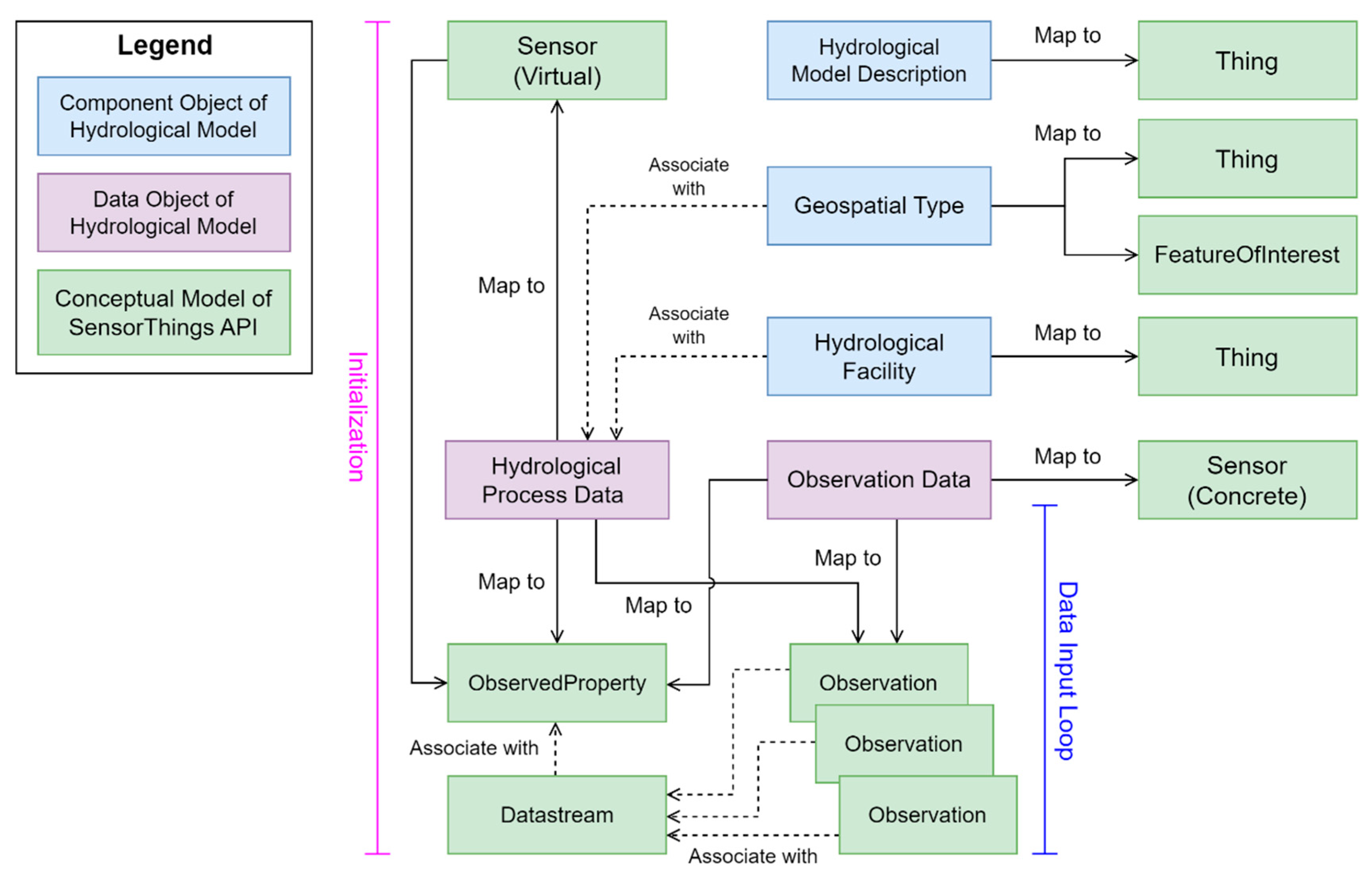

40]. It defines flexible, standardized interfaces and data models for retrieving and sharing observations from IoT sensor networks. Similarly, the conceptual models within the SensorThings API can be understood in terms of components and data. This parallel structure allows for a comprehensive mapping and transformation of hydrological models to the SensorThings API, addressing both the model components and the data aspects. Based on the above classification framework, the mapping relationship between the abstract classes of the hydrological information model and the SensorThings API conceptual model is shown in

Figure 2.

The mapping of object-oriented hydrological models to the OGC SensorThings API is not merely a technical transformation, but a strategic alignment with a widely adopted, standardized IoT data model. By conforming to the SensorThings API specification, the hydrological model becomes a natively interoperable component within any IoT ecosystem that supports this standard—enabling true “plug-and-play” integration without custom adapters or data format conversions. More importantly, this mapping unifies the semantic representation of real-world observations and virtual model outputs under a common conceptual framework. Physical sensors and simulated model entities are both expressed as Things, their measurable attributes as ObservedProperties, and their time-series values as Observations. This semantic consistency bridges the gap between the physical sensor network and the virtual hydrological simulation, laying a solid foundation for real-time, tightly coupled digital twin systems where observation-driven model updates and model-informed sensor interpretation can occur seamlessly within a single, coherent data infrastructure.

4.2.1. Mapping of Components in Hydrological System to SensorThings API

Many components in a hydrological system can be mapped to the concepts in a sensor network. Based on the abstract classes for hydrological models proposed earlier, mapping hydrological objects to the concepts in the SensorThings API offers a practical approach to integrating hydrological models into sensor networks.

In the SensorThings API specification, a Thing is an entity that can be identified and recorded by the Internet, representing either a real-world or virtual world entity. The FeatureOfInterest refers to an observed region or object of interest, often containing geographic feature information. The Sensor, in turn, is a component capable of observing certain properties of a Thing or FeatureOfInterest, and generating a data stream of observations. These conceptual models in the SensorThings API collectively define the structure of a sensor network and can be mapped to components in a hydrological system.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, based on the abstract classification framework introduced in

Section 4.1.1, the mapping of hydrological model components to SensorThings API concepts is conducted through a systematic and semantically rigorous methodology:

- (1)

The hydrological model system as a whole—including its global configuration parameters (e.g., simulation start and end times, time step)—is mapped to a Thing. This representation encapsulates the entire simulated hydrological system as a distinct and identifiable entity within the IoT ecosystem, facilitating comprehensive metadata management and lifecycle governance.

- (2)

Geospatial hydrological units—such as subcatchments or watersheds—which define spatial domains and function as primary rainfall-receiving areas, are represented as FeatureOfInterest objects. This mapping is consistent with the design principles of the SensorThings API, wherein a FeatureOfInterest refers to the geographic entity or location under observation. Given that these units inherently possess spatial attributes (e.g., polygon geometries), their modeling as FeatureOfInterest ensures seamless spatial interoperability with GIS systems and IoT platforms.

- (3)

Hydrological infrastructure elements—including conduits, junctions, pumps, and outlets—are also modeled as Thing entities. In contrast to passive spatial units, these components serve as active functional elements that regulate water flow and produce dynamic simulation outputs (e.g., water depth, flow velocity).

This classification-based mapping strategy preserves the semantic roles of hydrological entities within an IoT context. More significantly, it establishes a unified ontological framework bridging physical sensor networks and virtual hydrological models: both real-world sensors and simulated facilities are managed through the same API, utilizing standardized query patterns and real-time communication protocols. As a result, users can interact with the hydrological model not as a monolithic service, but as a set of discrete, addressable digital twins—each corresponding to a specific physical hydrological component—thereby enabling integrated data access, standardized querying, and scalable system management within IoT-enabled infrastructures.

4.2.2. Mapping of Data in Hydrological System to SensorThings API

The representation and acquisition of observation data are also critical aspects of sensor network systems. In the SensorThings API, the concept of ObservedProperty is used to represent the properties being observed from a Thing or FeatureOfInterest. Observation denotes the recorded value of an observed property at a specific time, while Datastream is a collection of observations about a particular ObservedProperty, linked to a given Sensor and Thing. These concepts form the data representation of the sensor network.

Following the abstract classification of hydrological model data introduced in

Section 4.1.1, this study distinguishes two primary data types: Observation Data (representing real-world measurements) and Hydrological Process Data (denoting model-generated outputs). Both data types are systematically mapped to the SensorThings API data model in a consistent and interoperable manner:

- (1)

Observation Data—such as rainfall and temperature—are collected from physical IoT sensors deployed in the field. Within the proposed framework, each physical sensor is represented as a Sensor entity; the environmental variable it measures (e.g., “rainfall”) is modeled as an ObservedProperty; individual measurements are stored as instances of Observation; and time-series data are organized into Datastreams associated with the corresponding sensor and the observed geographic feature (FeatureOfInterest).

- (2)

Hydrological Process Data—including runoff, water depth, and flow velocity —are dynamically generated by the hydrological model during simulation runs. These simulated outputs are also treated as observations: the modeled quantity (e.g., “waterDepth”) is defined as an ObservedProperty; each computed value at a given time step is recorded as an Observation; and the resulting sequence constitutes a Datastream. Notably, each hydrological facility (e.g., a junction or conduit) that produces such data is linked to a Sensor object, despite the absence of a physical sensing device.

This design is grounded in three key considerations:

- (1)

Behavioral Analogy: The mechanism by which a hydrological model component generates time-series outputs (e.g., water depth at a node over successive time steps) closely resembles the way a physical sensor produces sequential measurements. In both cases, the output represents a time-varying attribute of a specific geographic entity.

- (2)

Unified Interaction Paradigm: By representing simulated results as observations, users can access model outputs using identical API endpoints and communication protocols (e.g., /Datastreams({id})/Observations via HTTP or MQTT) as those used for real sensor data. This enables a uniform interface for both observed and simulated data, eliminating the need for separate data retrieval mechanisms.

- (3)

Reuse of Existing IoT Infrastructure: The introduction of Sensor objects—though non-physical—facilitates seamless integration with established IoT data systems, including MQTT brokers, data lakes, and visualization platforms. This approach prioritizes architectural consistency and operational efficiency over strict ontological equivalence.

Furthermore, a critical challenge was addressed during the mapping process: the mismatch between the temporal and spatial scales of observed data and those of model-generated outputs. To ensure compatibility with the model configuration, input observation data undergo necessary preprocessing, including unit conversion, temporal resampling, and spatial aggregation. These adjustments align the resolution of observational inputs with the simulation requirements, thereby preserving the fidelity and accuracy of the modeling process.

In summary, the proposed approach establishes a unified, standardized, and IoT-native representation for the complete data lifecycle in real-time hydrological modeling. By harmonizing both real-world observations and simulated outputs within the SensorThings API framework, it supports seamless data integration, efficient dissemination, and consistent interaction across heterogeneous data sources.

4.3. Hydrologic Model Running Control Interface Based on API-Processes Specification

In addition to offering an object-oriented description of the hydrological model with a structured IoT model mapping methodology, we introduce a model runtime control interface based on the OGC API-Processes standard. This interface allows users to pass hydrological model initialization parameters and control the model’s execution, including starting and stopping the simulation.

API-Processes is a processing service specification developed by the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC). It provides a set of RESTful APIs to facilitate the creation and execution of online services [

41]. Many of its conceptual models are inherited from the Web Processing Service (WPS) specification. Similarly to WPS, API-Processes defines a Process object to represent an invocable service, and a Job object to denote a service execution instance, and so on. However, unlike WPS, API-Processes adopts a more lightweight JSON format to represent these objects, making it more suitable for modern web-based applications.

In the system, a built-in Process object represents a hydrological model algorithm. Users can submit an Execute object containing hydrological model initialization parameters to create a Job. Once the request is processed, the server initializes the hydrological model and returns a JobID. Subsequently, users can use the JobID to control the execution of the hydrological model, including stopping the model when necessary. This mechanism ensures that the hydrological model can be dynamically managed through a standardized API, improving the flexibility of the user when interacting with the model.

4.4. Initialization Procedure for Hydrological Model Integration with Sensor Networks

Registering the components in the hydrological system with the sensor network is the first step in integrating the hydrological model. We have designed a process where, when the user starts the hydrological model initialization through the API-Processes interface, the system immediately parses the component objects in the hydrological model. These objects are then converted into the corresponding SensorThings API objects based on their types and subsequently registered to the SensorThings server.

Figure 3 illustrates the initialization process for integrating the hydrological model with the sensor network. This process is primarily initiated from two perspectives: hydrological model component objects and input observation data objects. Upon system startup, these objects are retrieved based on the model configuration, and their registration status is verified using their designated names. Only hydrological objects that have not yet been registered are transformed into corresponding SensorThings API objects and subsequently registered with the sensor network server.

For the conversion and initialization of hydrological model component objects, these objects are first mapped to Thing objects and subsequently to FeatureOfInterest objects, depending on their type. Next, the associated hydrological process information linked to these component objects is identified and transformed into corresponding virtual Sensor objects, ObservedProperty, and Datastream objects. The necessary associations between these entities are then established, and they are registered with the SensorThings API server. Similarly, for the conversion and initialization of input observation data, the data are directly mapped into concrete Sensor objects, ObservedProperty, and Datastream objects. After completing the association process, these entities are also registered with the server.

Through the initialization process we designed, we achieved a comprehensive mapping of the constituent objects in the hydrological model to the conceptual model in the SensorThings API and registered them with the sensor web server. This process also ensures that objects are not registered multiple times during subsequent launches, establishing a stable foundation for real-time modeling driven by sensor data.

4.5. Real-Time Modeling Procedure Driven by Sensor Data

The MQTT protocol is an IoT data exchange protocol that uses a publish-subscribe approach to enable real-time publishing and retrieval of data streams [

42]. In real-time hydrological modeling scenarios, the ability to receive sensor observations and input them into the hydrological model via the MQTT protocol facilitates real-time simulation of the hydrological model. This capability is also supported by the SensorThings API specification.

We designed a real-time, sensor data-driven hydrological modeling process that allows the model to receive real-time sensor data via the MQTT protocol after initialization, input this data into the hydrological model, and perform real-time simulations. In this process, two separate threads are utilized: one for real-time input into the model and the other for converting the model results into the SensorThings API Observation type. This parallel approach enhances the efficiency of real-time modeling and facilitates the mapping and conversion of simulation results.

As shown in

Figure 4, after the model is initialized, it is ready to receive real-time sensor data. When data for a given time step is received, it is immediately input into the model for simulation. Simultaneously, a separate thread continuously retrieves the real-time simulation results and the state of all hydrological objects in the model. These results are then converted to the Observation type in the SensorThings API, associated with the corresponding Datastream, and stored.

The sensor data-driven real-time hydrological modeling process we designed enables the real-time reception of sensor network data via the MQTT protocol, real-time input and simulation of the hydrological model, as well as the conversion and storage of model results as Observation objects. By processing these tasks in two separate threads, we ensure the efficient execution of real-time hydrological modeling while unifying the representation of the model results.

5. Implementation and Results

5.1. SWMM to SensorThings API Conceptual Model Mapping

In the experiment, SWMM elements were first categorized according to the classification framework proposed in this paper. The RainGage object, responsible for receiving all input precipitation data, was classified as a sensor type. The Subcatchment object, which represents an area capable of receiving precipitation, was categorized as a region or basin type. Other elements, such as Conduit, Junction, and Outfall, which influence the state of the hydrological system, were classified under hydrological facility types. Additionally, each element has attributes related to simulation computations, such as runoff for Subcatchment objects, marked as computed properties, while attributes determined during initialization were classified as intrinsic properties.

These SWMM components and data from computed properties are then mapped to the conceptual model of the SensorThings API according to the methodology of this paper to ensure that the SWMM can be integrated with the IoT system, and the mapping correspondence is shown in

Table 2 below.

5.2. Prototype Implementation

In this study, a project named SWMM-Java was developed to implement a Java encapsulation of the SWMM. SWMM provides the swmm5.dll dynamic link library (DLL), which allows the model to be called programmatically through C function calls. In SWMM-Java, we utilized the Java Native Interface (JNI) technology to implement object-oriented encapsulation and invocation of SWMM. With this integration, any Java application can incorporate the SWMM into its system and control its operation using an object-oriented approach.

Reactor is an implementation library for asynchronous reactive programming that employs a publish-subscribe pattern for processing data streams asynchronously. Its implementation fully complies with the Reactive Stream specification [

43]. In SWMM-Java, we incorporated Reactor to enable asynchronous publish and subscribe functionality for real-time simulation results from the SWMM. Users can subscribe to the simulation results for each step of the SWMM, allowing them to process the results concurrently while invoking the model for real-time simulation. This approach decouples the input and result processing tasks, enabling users to focus solely on managing data input and output, without needing to handle the scheduling of these operations.

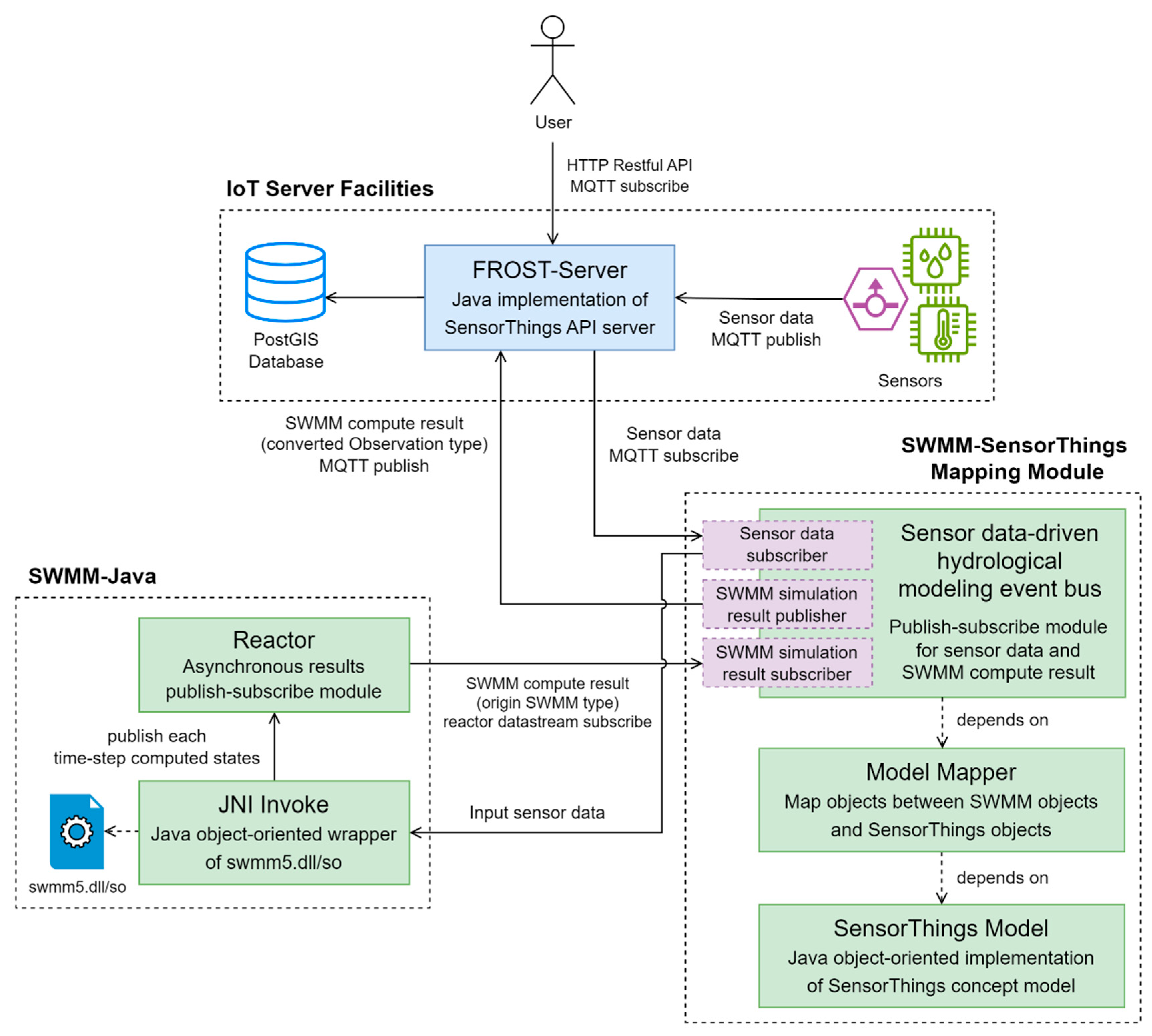

FROST-Server is an open-source implementation of the SensorThings API standard, supporting both HTTP and MQTT protocols for sensor network data exchange, and utilizing PostGIS as the data layer [

44]. In this study, we used FROST-Server to establish the SensorThings Server infrastructure and developed the SWMM-SensorThings Mapping Module to interface the SWMM with the SensorThings Server.

The SWMM-SensorThings Mapping Module consists of three components: the SensorThings Model, the Model Mapper, and the Sensor Data-Driven Hydrological Modeling Event Bus.

- (1)

SensorThings Model: This component is a Java-based implementation of the conceptual models defined in the SensorThings API.

- (2)

Model Mapper: This module handles the conversion of hydrological models and data from SWMM-Java to the corresponding conceptual models in the SensorThings API, based on the rules defined in the methodology.

- (3)

Sensor Data-Driven Hydrological Modeling Event Bus: This is a general scheduling module built on the publish-subscribe pattern for data exchange between SWMM and the sensor network. It performs several key tasks:

First, it provides a streamlined set of service interfaces that enable users to supply hydrological model configurations for initializing the model and to control its execution, including starting and stopping the model.

It subscribes to real-time sensor data from the sensor network server via the MQTT protocol and inputs this data into the SWMM.

It also subscribes to the computation results of the SWMM using Reactor, converting these results to the Observation type in the SensorThings API.

Finally, the converted computation results are published via the MQTT protocol to FROST-Server, where they are associated with the corresponding Datastream.

Users can eventually obtain model simulation results from FROST-Server entirely through the standard methods defined by the SensorThings API. The overall architecture of the prototype system is shown in

Figure 5. In this system, users can subscribe to Observation objects in the corresponding Datastream based on the computational attributes of the hydrological model of interest via the MQTT protocol, enabling real-time retrieval of simulation results for specific attributes within the hydrological system. Additionally, historical simulation results, as well as other components within the hydrological system, can be accessed via the HTTP requests.

5.2.1. Running Control of Hydrological Model

The SWMM uses an .inp file to encapsulate all initialization parameters, including the model’s constituent elements, global settings, and other configurations.

A client can initialize and start a SWMM instance using the following steps:

- (1)

Query the SWMM process ID: Send a HTTP GET request to SERVICE_BASE_URI/processes to retrieve a list of available processes, including the SWMM process ID.

- (2)

Start the SWMM: Submit a HTTP POST request with the inp file’s address to SERVICE_BASE_URI/processes/{id}/execution, the server responds with a jobId, representing the instance of this running hydrological model.

- (3)

Stop a running SWMM: Send a DELETE request to: SERVICE_BASE_URI/jobs/{jobId}, this terminates the execution of the specified jobId.

5.2.2. Observational Data-Driven Real-Time Modeling

The sensor publishes real-time observation data to the SensorThings server using the MQTT protocol. Simultaneously, the system subscribes to this data, processes it preliminarily, and inputs it into the hydrological model. The model then performs real-time step-based calculations. The results of each calculation step are also published to the SensorThings server in real time. For instance, when a sensor posts observations to the MQTT topic /v1.1/Datastream({RainGage_id})/Observations, the system feeds this data into SWMM’s rain gauge which name is RainGage, to execute step-based computations. The calculation results, such as the surface runoff at W180, are then published in real time to the MQTT topic /v1.1/Datastream({W180_runoff_id})/Observations.

5.3. Real-Time Modeling Data Retrieval Results

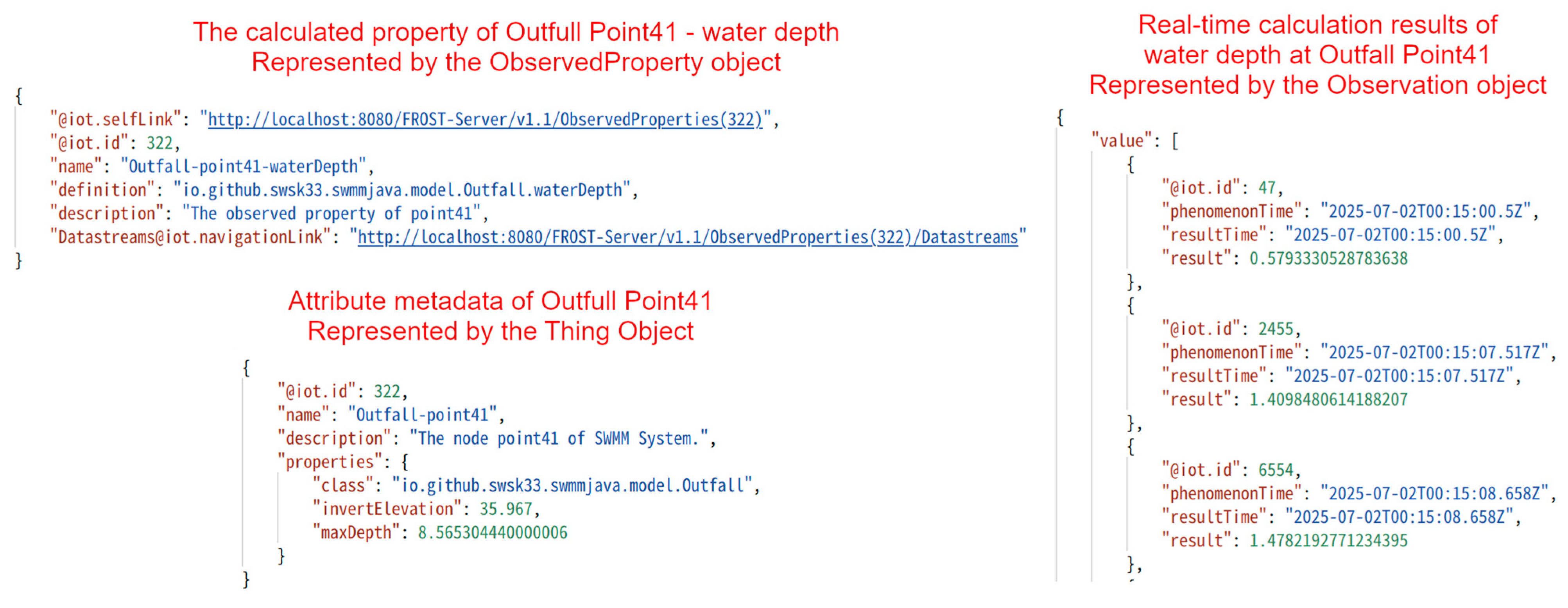

During the model’s simulation process, any client can retrieve the computed properties of simulated hydrological facilities in real time using either HTTP or MQTT network protocols. For instance, to access the simulation result of the real-time flow depth of conduit R30, clients can use the HTTP request pattern SERVICE_BASE_URI/v1.1/Datastreams({R30-currentFlowDepth_id})/Observations. Alternatively, clients can subscribe to the MQTT topic /v1.1/Datastreams({R30-currentFlowDepth_id})/Observations to receive real-time simulation results. The ID of the ObservedProperty can be queried through API SERVICE_BASE_URI/v1.1/ObservedProperty.

As illustrated in

Figure 6, whether it is to obtain the metadata of hydrological model components or the time-series simulation results, all data are uniformly represented using the standard JSON objects defined by the SensorThings API.

By leveraging the consistency of the SensorThings API specification and the publish-subscribe mechanism of MQTT, users can seamlessly access the simulation results for any attribute of any hydrological facility object in the SWMM in real time via the SensorThings server. Furthermore, the conditional query functionality provided by the SensorThings API specification allows users to filter and retrieve historical data efficiently.

Figure 7 illustrates some real-time variations during the real-time hydrological modeling experiments.

Figure 7 presents an example of the time-series visualization of four key hydrological state variables generated during the observation-driven real-time simulation. The blue curve represents the input precipitation intensity over time, while the orange curves depict the corresponding simulated responses—including inflow of outfall Point 41, flow of conduit 15, inflow of junction 11003 and surface runoff of sub-catchment S18. These results illustrate how the system dynamically reacts to real-time rainfall inputs within the IoT-integrated framework.

Crucially, the simulation outputs produced by the IoT-coupled system are numerically identical to those obtained by running the same SWMM independently with the same input data. This demonstrates that our integration approach—while enabling real-time data ingestion, fine-grained state exposure, and standardized IoT access—does not alter or interfere with the underlying hydrological computation logic. The model’s intrinsic behavior and accuracy are fully preserved.

6. Discussion

Most hydrological models are designed with inherent limitations in interoperability, real-time processing, and data sharing. To overcome these constraints, we encapsulate the hydrological model using an object-oriented approach and map it to the SensorThings conceptual model. This enables seamless integration with sensor networks, real-time modeling, as well as standardized sharing and representation of hydrological data.

By adopting this approach, hydrological modeling is no longer restricted by human, computational, and data resources confined to a single machine. Instead, it facilitates a more flexible and real-time modeling workflow, allowing for dynamic data-driven simulations and improved adaptability in hydrological analysis.

6.1. Object-Oriented Modeling and IoT Mapping of Hydrological Models: From “Black Box Services” to “Observable Hydrological Digital Twins”

This study proposes an object-oriented modeling framework for hydrological systems and systematically maps it to the OGC SensorThings API standard, aiming to fundamentally enhance the interoperability, observability, and real-time interaction capabilities of hydrological models within IoT environments.

Existing approaches to improving hydrological model interoperability can be broadly categorized into two paradigms. The first is Model-as-a-Service (MaaS) based on the OGC Web Processing Service (WPS) standard, which encapsulates models as web-accessible processes [

45,

46]. The second involves component-based encapsulation using frameworks such as OpenMI or OpenGMS, which define standardized interfaces for model coupling and data exchange [

4,

32]. While these methods have significantly advanced model accessibility and standardization, they remain fundamentally process-oriented: users submit input parameters, trigger a monolithic execution cycle, and retrieve final outputs. WPS treats the entire model as a single Process object, which focuses on the operation of Execute, Dismiss and GetResult; OpenMI, though enabling inter-model communication, still revolves around the Initialize-Run-Finalize workflow. Critically, neither approach supports fine-grained, real-time access to internal model states—such as querying the water depth at a specific junction at specific time—which severely limits their utility in digital twin, emergency response, or adaptive control scenarios that demand dynamic situational awareness.

In contrast, our object-oriented hydrological modeling paradigm deconstructs the model into semantically meaningful, independently addressable entities—namely, the overall model system (Model Description), geospatial units (Geospatial Hydrological Units), and functional infrastructure (Hydrological Facilities). Meanwhile, by mapping these entities to SensorThings API concepts—specifically, Thing and FeatureOfInterest—each component becomes a first-class citizen in the IoT ecosystem. This design not only transforms the hydrological model from a closed desktop application into a modular, composable service but, more importantly, bridges the semantic gap between physical sensors and virtual simulations. Both real-world observations and model-generated states are represented under a unified conceptual model (Thing–Sensor–Datastream–Observation), enabling seamless data fusion and bidirectional interaction within a single, standardized infrastructure. This deep integration enables real-time observability of every simulated entity and asynchronous, subscription-based interaction, marking a qualitative leap toward the vision of “Model as Digital Twin”—where the hydrological model is not just a computational tool, but an observable, controllable digital counterpart of the real-world water system.

6.2. Observation-Driven Real-Time Hydrological Modeling: A Universal Integration Paradigm Based on the SensorThings API Specification

This study presents a standardized, observation-driven framework for real-time hydrological modeling by leveraging the OGC SensorThings API as a unified data and communication backbone. Unlike ad hoc or custom-built integration pipelines, our approach embeds both physical sensors and hydrological models into a single, interoperable IoT ecosystem governed by open standards.

Existing efforts to enable real-time hydrological simulation have indeed demonstrated the feasibility of coupling models with live sensor data. For instance, Shangguan et al. (2019) [

33] employed Apache Spark’s stream processing capabilities to ingest sensor network data and drive a runoff model in near real time. Similarly, Herle et al. (2018) [

34] extended the OGC Web Processing Service (WPS) with MQTT-based messaging to support real-time geo-processing triggered by sensor observations. While these studies represent important steps toward dynamic environmental modeling, they rely on custom data pipelines and application-specific implementation. As a result, their architectures are tightly coupled, difficult to generalize across models or domains.

In contrast, our framework achieves end-to-end standardization by fully aligning with the SensorThings API specification. The hydrological model is not merely “connected” to sensors—it is natively represented within the same conceptual model: input observations (e.g., rainfall) and output simulations (e.g., water depth) are both expressed as Observations belonging to Datastreams linked to Things and ObservedProperties. Crucially, the SensorThings API’s native support for MQTT publish-subscribe messaging enables seamless real-time data flow: sensor data are published to MQTT topics, automatically ingested by the model, and simulation results are in turn published to corresponding topics for immediate consumption.

This “model once, embed anywhere” paradigm eliminates the need for bespoke integration logic. Any SensorThings-compliant client—whether a flood dashboard, a digital twin engine, or an automated control system—can discover, subscribe to, and act upon hydrological simulation results using standardized RESTful queries or MQTT subscriptions, just as they would with physical sensor data. Consequently, the deployment and maintenance costs of real-time hydrological systems are significantly reduced. This standardization is particularly transformative in operational contexts such as urban flood emergency platforms or smart water utility digital twins, where rapid integration of modeling capabilities into existing IoT infrastructure is critical.

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

While the proposed framework demonstrates significant advances in interoperability, real-time interaction, and IoT-native integration of hydrological models, it is not without limitations.

First, the object-oriented decomposition of hydrological models, though enabling fine-grained state access, increases the conceptual and operational complexity for end users. Interacting with the model now requires understanding the internal structure—e.g., identifying the correct Thing ID for a junction or the Datastream ID for a specific simulated property—rather than simply submitting a bulk input file and retrieving outputs. This may pose a barrier for non-technical stakeholders. Future work will explore semantic abstraction layers to simplify user interaction without sacrificing the underlying granularity.

Second, by representing simulated outputs as Observations generated by virtual Sensors, the framework introduces a potential risk of semantic confusion between physical measurements and model-derived values. Although this design enables unified data access, it may obscure critical differences in uncertainty structure, error sources, and scale representativeness. To mitigate this, we recommend explicitly annotating the data provenance in metadata—for instance, by adding a dataSource: Simulation or Observation property to ObservedProperty or Sensor objects—so downstream applications can differentiate and handle these data types appropriately.

Finally, this study focuses primarily on architectural feasibility and integration methodology, rather than hydrological performance validation. Due to the constraints of publicly available datasets, no co-located, high-frequency observations of runoff or water level were available for quantitative model evaluation. Therefore, at present, we are only focusing on evaluating the correctness of the integration of the model with the IoT system and have not conducted an accuracy assessment of the model simulation.

In future work, we plan to collaborate with municipal water utilities and environmental monitoring agencies to deploy this framework in instrumented urban watersheds equipped with real-time sensor networks. Such deployments will enable: (1) multi-event validation across different hydrometeorological conditions; (2) quantitative assessment of model fidelity under real-time operation; and (3) investigation of data assimilation strategies within the proposed IoT-native architecture to dynamically adjust model states and enhance predictive accuracy.

7. Conclusions

Integrating hydrological models with sensor networks is essential for real-time hydrological decision-making. This study proposes a standardized framework that bridges hydrological simulation and IoT ecosystems through three tightly coupled work.

First, we introduce an object-oriented modeling paradigm to deconstruct hydrological systems into fine-grained, independently addressable entities—providing the foundation for real-time state access and modular interaction. Building upon this, we establish a systematic mapping to the OGC SensorThings API, aligning hydrological components and simulated outputs with standardized IoT concepts. Finally, leveraging the SensorThings API’s native support for MQTT, we implement an observation-driven real-time modeling workflow, where live sensor data automatically trigger model updates and simulation results are published as observations. These three works form a coherent pipeline: the object-oriented representation enables the mapping, and the mapping enables standardized, real-time interoperability. Importantly, this approach is model-agnostic, while demonstrated with SWMM, the framework can be applied to other hydrological models by adapting the object abstraction layer.

To validate feasibility, we implemented a prototype system based on the SWMM and integrated it with a FROST-Server SensorThings backend. The system successfully demonstrated real-time ingestion of rainfall observations, fine-grained access to simulated states, and standardized publication of results via both HTTP and MQTT.

This work thus provides a practical, standards-based pathway to transform hydrological models from isolated desktop tools into observable, interoperable components of smart water infrastructure—a critical step toward operational hydrological digital twins.