1. Introduction

Phosphonates or organophosphonates are organic compounds characterized by at least one phosphonic acid group. The aminophosphonates ((poly)amino(poly)methylenephosphonates) form a group of phosphonates that typically contain one or more C-P bonds, and all available N-H functions are saturated with methylenephosphonate moieties. Most synthetic aminophosphonates are produced for their complexing and anti-scaling properties and therefore contain more than one C-P bond. An exception is the herbicide glyphosate, which contains only one C-P bond. They are widely used in agriculture and in industrial and domestic applications.

During the last decades, aminophosphonates have gained substantial economic importance as ingredients in cleaning detergents, anti-scaling and anti-corrosion agents, fire retardants, and dispersants in ceramics and cement industries. In household applications, they are frequently used as sequestrants in toilet cleaners, laundry detergents, or dishwashing detergents. It is assumed that, due to their poor degradability, phosphonates are almost completely discharged into wastewater. Rott et al. [

1] calculated that about 85% of the phosphonate content in municipal wastewater originates from household applications.

The discharge of phosphate and organic phosphorus compounds from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) into the aquatic environment causes eutrophication as a serious environmental problem [

2,

3]. In wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), phosphonates contribute to the total P load as particulate P (PP) and the dissolved unreactive P fraction (DUP), respectively [

4]. They are difficult to eliminate by conventional chemical elimination processes in WWTPs. In two German WWTPs, phosphonate P was found to account for 10–40% of the dissolved, poorly precipitable P fraction [

4]. The increasing presence of phosphonates in the effluent of WWTPs makes consistent compliance with discharge standards for total phosphorus in wastewater increasingly difficult. [

5].

In this study, three different aminophosphonates from household applications, aminotrimethylene phosphonic acid (ATMP), ethylenediaminetetra(methylene phosphonic acid) (EDTMP), and diethylenetriaminepenta(methylene phosphonic acid) (DTPMP), were evaluated for their ability to adsorb to activated sludge during the wastewater treatment process. Glyphosate (N-(phosphonomethyl)glycin), which has also been studied, is primarily known as an herbicide in agriculture. Nevertheless, considerable concentrations have recently been identified in domestic wastewater too [

6,

7]. The origin of these increased concentrations is still not completely understood.

For more than three decades, it was assumed that industrially and commercially available phosphonates such as HEDP, ATMP, EDTMP, and, especially, DTPMP were not readily biodegradable [

1]. Conventional biodegradation tests according to OECD test methods showed no or only slight degradation. Nevertheless, recent studies have demonstrated that microbial biodegradation is a viable option in cases of P deficiency [

8,

9]. As long as a more suitable P source such as o-PO

43− is available, bacteria will consume the inorganic phosphate, which is more easily available [

10]. Consequently, biodegradation of phosphonates in WWTPs is negligible due to the relatively high o-PO

43− concentrations. Nevertheless, several studies have reported significant elimination, at between 40% and >90%, due to sludge adsorption [

1,

11]. For glyphosate, overall removal efficiencies were in the range of 71% to 96% [

6]. Activated sludge has been widely identified as the most important adsorbent in wastewater treatment plants [

12,

13]. The strong adsorption leads to substantial enrichment of phosphonates in the sludge. Due to this enrichment and the long residence time of activated sludge (several days, compared to hours for wastewater itself), concentrations in treated wastewater show comparatively little variation, whereas concentrations in raw wastewater may fluctuate considerably.

The large discrepancies between different adsorption measurements may be caused by differences in the sludge composition. The activated sludge is a complex mixture of different components that vary with time, location, and the applied wastewater treatment methods. Therefore, the adsorption affinity of phosphonates on the sludge as a whole cannot be investigated in a meaningful way without identifying the role of individual constituents. The main component in activated sludge is organic matter, with a portion of 50% to 70%. The organic matter includes a heterogeneous biomass consisting of out of bacterial and eukaryotic microorganisms, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) such as sugar polymers and proteins, as well as organic compounds that are the result of or subject to biodegradation, such as humic acids [

14], cellulose, and lignin [

15]. Activated sludge flocs also contain a number of inorganic substances, including inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus compounds, silicates, and different metals [

15]. The main metals are ferrous and aluminum hydroxides, which are added for chemical phosphorus elimination.

The adsorption of phosphonates on various surfaces has been investigated in several studies before. Nowack and Stone [

16] studied the adsorption of eight phosphonates, including IDMP (iminodi(methylene phosphonic acid), HEDP (hydroxyethylidene diphosphonic acid), EDTMP, and DTPMP, on natural ferric hydroxide, known as goethite, as a function of pH, ionic strength, and phosphonate concentration, using experimental data and a surface complexation model (the 2-pK constant capacitance model). In this study, a strong pH dependence was detected with the highest adsorption rates at an acidic pH, while no adsorption was observed beyond pH 12. The authors also found a correlation between phosphonate adsorption and the number of phosphonic acid groups. At pH 7.2, the maximum extent of adsorption decreased as the number of phosphonate groups increased. Reinhard et al. [

17] confirmed these results for adsorption on granular ferrous hydroxide. This study also supported previous findings that reported a decrease in phosphonate adsorption on ferric hydroxides with an increasing number of C-P bonds [

18]. In contrast, Liu et al. [

19] found no significant impact of pH on the adsorption of HEDP, whereas the presence of HCO

3−/CO

32− markedly suppressed the removal of HEDP and PO

43− onto Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles.

Both ferric hydroxides [

17,

18,

20] and aluminum hydroxides [

18] have been shown to be potential adsorbents for phosphonates. Therefore, ferric iron (Fe

3+) or aluminum (Al

3+) might also enhance or dominate the adsorption process on activated sludge.

During the last years, most studies focused on the efficient removal of inorganic phosphate from wastewater [

21,

22]. The hydroxyl groups and iron ions formed on the surface of the adsorbent by iron elements have been identified as the key active sites for phosphorus adsorption. These sites can react with phosphate ions through complexation or precipitation, thereby achieving highly efficient phosphorus removal [

21]. Some other studies focused on the adsorption mechanism using pure adsorbents [

5,

19,

20]. However, results from adsorption experiments with pure metal hydroxides are not transferable to the activated sludge treatment process because the metal hydroxides are located within the sludge flocs and may be surrounded by extracellular polymers. Moreover, according to our knowledge, previous studies have not taken into account the dissolution of the adsorbent by the phosphonates. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the interaction of ferric or aluminum hydroxides and organic components in activated sludge during the adsorption of phosphonates from wastewater, taking into account the interaction of adsorption and dissolution of the adsorbent by the substrates to be adsorbed. ATMP, EDTMP, and DTPMP have been used as model substances with common household applications. As the importance of WWTPs for glyphosate releases to surface water has recently been intensively discussed, we also looked at the interaction between phosphonates from home use and glyphosate releases from WWTPs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

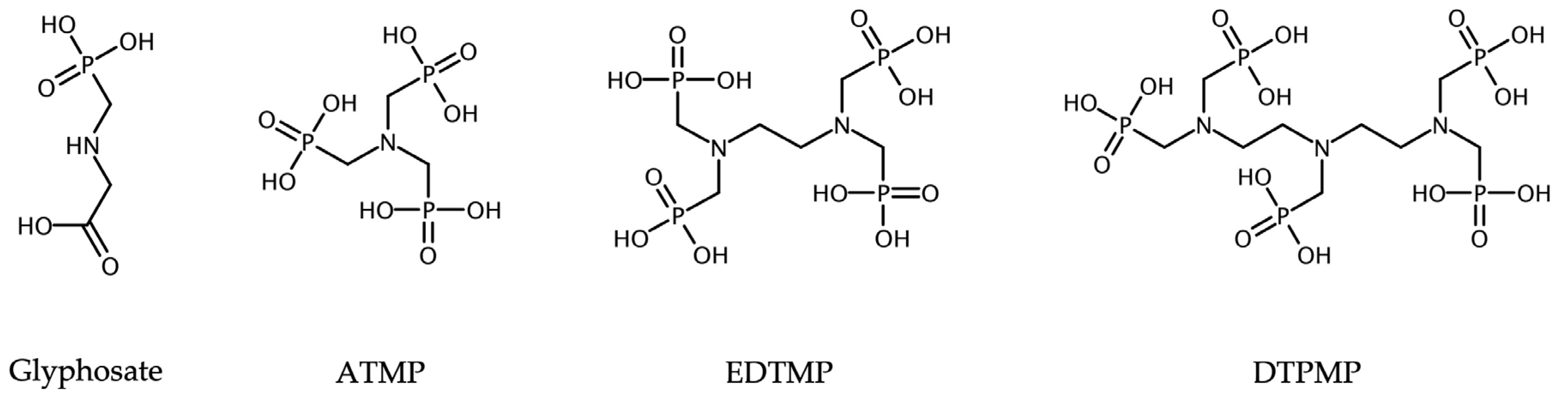

The phosphonates ATMP, EDTMP, and DTPMP were provided by Zschimmer & Schwarz Mohsdorf (Burgstädt, Germany). The selected phosphonates are representative for complexing agents containing either three (ATMP), four (EDTMP), or five phosphonate groups (DTPMP). They are commonly used in different household applications. Glyphosate was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). It contains only one phosphonate group. The exact source of glyphosate in wastewater treatment plants is still under investigation; it is not yet fully understood where it comes from. The structure of the substances is shown in

Figure 1.

Acetonitrile, which was used for preparation of the HPLC mobile phase, was LC/MS-grade (Merck Co., Darmstadt, Germany). All other chemicals and reagents were of reagent grade or a higher purity.

For all adsorption experiments, local tap water (TW) was used. The composition—90 mg L−1 Ca2+, 20 mg L−1 Mg2+, 15 mg L−1 Na+, 2.5 mg L−1 K+, 32 mg L−1 Cl−, ≤0.1 mg L−1 PO43−, and 115 mg L−1 SO42−—was representative of local wastewater.

Buffer solution was prepared by dissolving 12.4 g citric acid 1-hydrate (AppliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) in 840 mL of TW and adjusted with 160 mL of 1M NaOH to pH 6.2. NaOH and HCl were used for pH adjustment if necessary.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

The adsorption of the phosphonates ATMP, EDTMP, and DTPMP was studied at different concentrations and on three different sorbents. Beside activated sludge, ferric hydroxide and aluminum hydroxide were investigated as separated sorbents. For the experiments, activated sludge (AS) from three different origins was used. This was necessary because the sludge composition differed according to the different treatment conditions. The first sludge (AS1) originated from a large-scale local municipal WWTP in Cottbus, which practices chemical P elimination with Fe and Al salts. Therefore, this sludge contained high iron and aluminum contents. The second sludge (AS2) came from a small decentral WWTP without any chemical P elimination and thus should not have contained iron or aluminum salts in the sludge flocs. Finally, AS3 came from a local medium-sized municipal WWTP without chemical P elimination. AS1 contained 205.0 mg L−1 Fe and 130.8 mg L−1 Al. AS2 and AS3 did not contain significant amounts of Fe or Al.

As no sludge was available that contained Al but no Fe, AS2 was artificially enriched with Al. This was achieved by dissolving aluminum sulfate 18-hydrate in the supernatant of the sludge after sedimentation for 30 min. The pH of the supernatant was then set to 7.0 ± 0.5, leading the dissolved Al3+ to precipitate as amorphous aluminum hydrate. Thereafter, the supernatant and the sediment were mixed again. The same procedure was used to enrich portions of AS3 artificially with Fe(OH)3. The Fe-enriched sludge was prepared by precipitation of amorphous iron hydroxide from dissolved ferric sulfate as described above for Al. For the experiments, two different iron concentrations were prepared, 103.3 mg L−1 Fe (adsorbent Fe100) and 69.9 mg L−1 Fe (adsorbent Fe70).

To remove dissolved o-PO

43−, the sludge was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was discharged and the pellet was resuspended with TW. This process was repeated three times. The composition of the sludge types and experimental setups is summarized in

Table 1.

The phosphonate stock solutions were prepared at 2.5 g L−1 in TW and adjusted to pH 7.0 ± 0.5. Adsorption test solutions contained eight to nine different phosphonate concentrations in TW and constant amounts of adsorbent in a total volume of 25 mL. With AS1 and AS2, phosphonate concentrations were 50, 75, 100, 150, 200, 250, 500, and 750 mg L−1. For EDTMP and DTPMP, an additional concentration of 300 mg L−1 was prepared as well. With AS3, concentrations of 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 200, and 400 mg L−1 were prepared for ATMP. For EDTMP and DTPMP, the concentration of 400 mg L−1 was omitted and an additional concentration of 150 mg L−1 was prepared instead.

All adsorption tests were performed at room temperature. The samples (150 mL each) were adjusted to pH 7.0 and incubated in a rotary shaker at 150 rpm for a period of 48 h. Preliminary tests indicated that equilibrium was reached after this time. All tests were carried out in triplicate. Two controls, one without sorbent medium and one without phosphonate, were also prepared.

2.3. Analytical Methods

PO

43− was measured as phosphomolybdate with a Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrophotometer (Tokyo, Japan) at a wavelength of 880 nm according to the European standard procedure EN ISO 6878:2004 [

23]. For the determination of total phosphorus (TP), the samples were digested in a microwave digester (MARS 5, CEM, Kamp-Lintfort, Germany) with 200 mg of Oxisolv. The diluted samples were heated for 5 min to a temperature of 170 °C, which was maintained for 4.5 min. After cooling, TP in the form of o-PO

43− was measured as described above. The concentrations of Fe and Al were determined using a 4100 MP-AES system (Agilent, Mulgrave, Australia). We mixed 10 mL of the sample with 0.2 mL CsCl solution (50 g L

−1). Fe was measured at 302.064 nm and 371.993 nm. The emission of Al was measured at 394.401 nm and 396.152 nm. To dissolve Fe and Al from sorbents, the samples were mixed with concentrated hydrochloric acid (32%) at a ratio of 4:1. The concentration of suspended solids (TSS) of the AS was measured according to DIN EN 12880 [

24]. The sample was rinsed under low pressure with deionized water on a 0.45 µm cellulose acetate filter (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) to remove dissolved ions. The samples were dried at 105 °C with a drying balance DAB 100-3 (Kern & Sohn, Balingen-Frommern, Germany) until weight stability was reached.

The phosphonates EDTMP, ATMP, DTPMP, and glyphosate were determined by LC-ESI-MS using a Finnigan MAT LC/MS (LC spectral system P4000, LCQ MS Detector, autosampler AS 3000, Thermo Finnigan MAT GmbH, Bremen, Germany). The separation of the samples was carried out on a SeQuant ZIC-Hilic column (150 × 2.1 mm, 3.5 μm/100 Å; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The column temperature was 35 °C and the flow was 0.2 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of a gradient mixture of 25 mM ammonium acetate in water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). The gradient started with 10% solvent A and was held isocratic for 5 min. The percentage of solvent A was increased linearly to 60% for 10 min and was held for 5 min. Afterwards, solvent A was linearly increased to 90% within 3 min and held for another 5 min. The settings for the detector were negative ionization with 3.3 kV and a spray capillary temperature of 220 °C. The substances were quantified in SIM mode with the following mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios: EDTMP 435, ATMP 298, DTPMP 572, and glyphosate 168.

The location and concentrations of iron and phosphorus within the sludge flocs were measured by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and EDX analysis (Zeiss DSM 962/e-point electronics with Oxford Instruments; X-Max 50 and INCA EDX analysis software V 7.4.7; Zeiss Oberkochen, Germany). The scattering samples were sputtered with gold and analyzed at 20 keV and 75 µA. Before starting the analyses, all samples were dried at 105 °C.

2.4. Adsorption Isotherm Calculations

The equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) of the adsorbent and the corresponding equilibrium concentration (Ceq) in solutions with varying concentrations were determined and subsequently modeled using the Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption isotherms, as outlined below.

qe—equilibrium adsorption (mmol phosphonate g−1 adsorbent);

KF—Freundlich coefficient;

Ceq—equilibrium dissolved phosphonate concentration (mmol L−1);

n—Freundlich exponent.

qe—equilibrium adsorption (mmol phosphonate g−1 adsorbent);

qmax—maximum equilibrium adsorption (mmol phosphonate g−1 adsorbent);

K—Langmuir sorption coefficient;

Ceq—equilibrium dissolved phosphonate concentration (mmol L−1).

All calculations were conducted with consideration of the loss of metal hydroxides resulting from complex formation. We used an unweighted non-linear regression using the least-squares method to obtain an optimal set of parameters.

3. Results

Before starting individual adsorption experiments, different adsorption models were tested for their suitability to describe the adsorption of phosphonates on activated sludge. A detailed model description has been provided before [

25]. It was found that the data fitted well to the conventional Langmuir and Freundlich models.

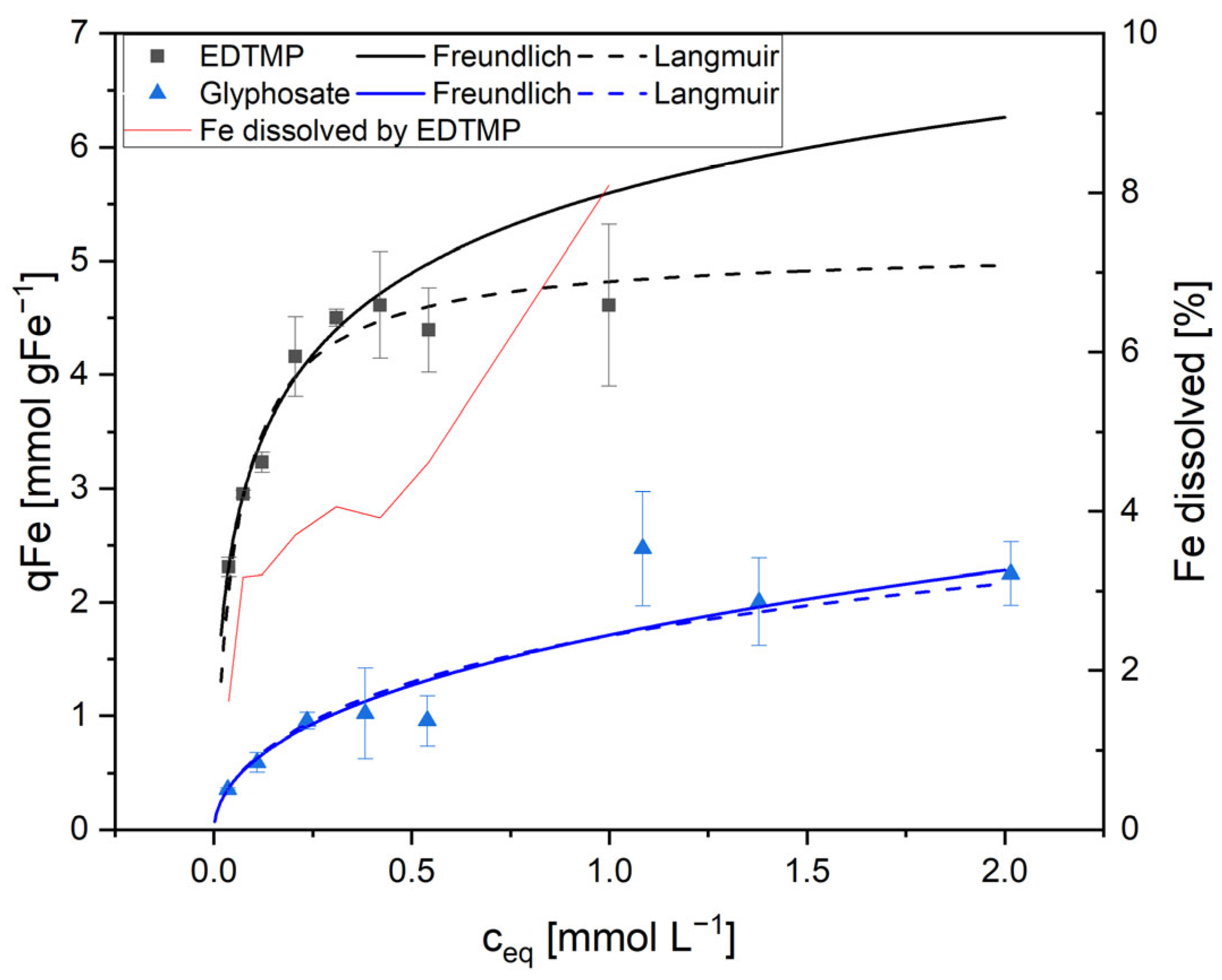

Figure 2 shows this for the adsorption of EDTMP and glyphosate on AS1.

For complexing phosphonates as EDTMP, it was observed that the standard deviation increased with increasing equivalent concentrations (

Ceq). This was true for all adsorption experiments with sludge containing ferric hydroxide or with pure Fe(OH)

3 as adsorbents. In contrast, glyphosate isotherms remained stable and reproducible also at higher concentrations.

Figure 2 illustrates the reason. EDTMP, ATMP, and DTPMP are strong complexing agents. As a result, these phosphonates are on the one hand adsorbed on the surfaces of the ferric hydroxide flocs. On the other hand, the solid iron hydroxide species were dissolved with an increasing phosphonate concentration by forming soluble Fe-phosphonate complexes, resulting in the release of Fe

3+ into the liquid. The interaction between adsorption and complexation of adsorbing metals thus modifies the available metal surface. Therefore, the Freundlich model fitted better at low phosphonate concentrations but was not suitable at higher phosphonate concentrations when complexing was the dominant process (

Figure 2,

Table 2). At higher concentrations of complexing phosphonates, an apparent maximum loading was observed, which consequently resulted in the Langmuir model providing a superior fit in comparison to the Freundlich model. However, it should be noted that the Langmuir fit was only an apparent one, resulting from two factor: firstly, the adsorption of phosphonates, and secondly, the dissolution of the adsorbent due to the complexing effects of the phosphonates. In contrast, glyphosate lacks complexing properties and did not dissolve the adsorbing agent. Consequently, this compound showed a strong correlation with the Freundlich model even at higher concentrations up to 2 mmol L

−1. This interaction between adsorption and dissolution of the adsorbent needs to be considered in the calculation of adsorption in all technical applications.

To evaluate the individual contributions of organic matter and metal components to the adsorption of phosphonates on activated sludge, sludge samples with different metal contents were studied. AS3 did not contain any metal flocculants and was used to measure the adsorption on the organic components in activated sludge. To study the effect of Fe-flocculants in the sludge, portions of AS3 were artificially enriched with Fe(OH)

3 by simulated flocculation. The Fe-enriched sludge was prepared by precipitation of amorphous iron hydroxide from dissolved ferric sulfate as described above for Al (

Section 2.2). For the experiments, two different iron concentrations were prepared, 103.3 mg L

−1 Fe (Fe100) and 69.9 mg L

−1 Fe (Fe70). AS1 originally contained Fe and Al flocculants. As no sludge containing only aluminum was available, AS2 was artificially enriched with Al(OH)

3 as described in

Section 2.2. To verify the results of the sludge adsorption experiments, an additional experiment with only amorphous Fe(OH)

3 was performed. In total, six different adsorbents were prepared.

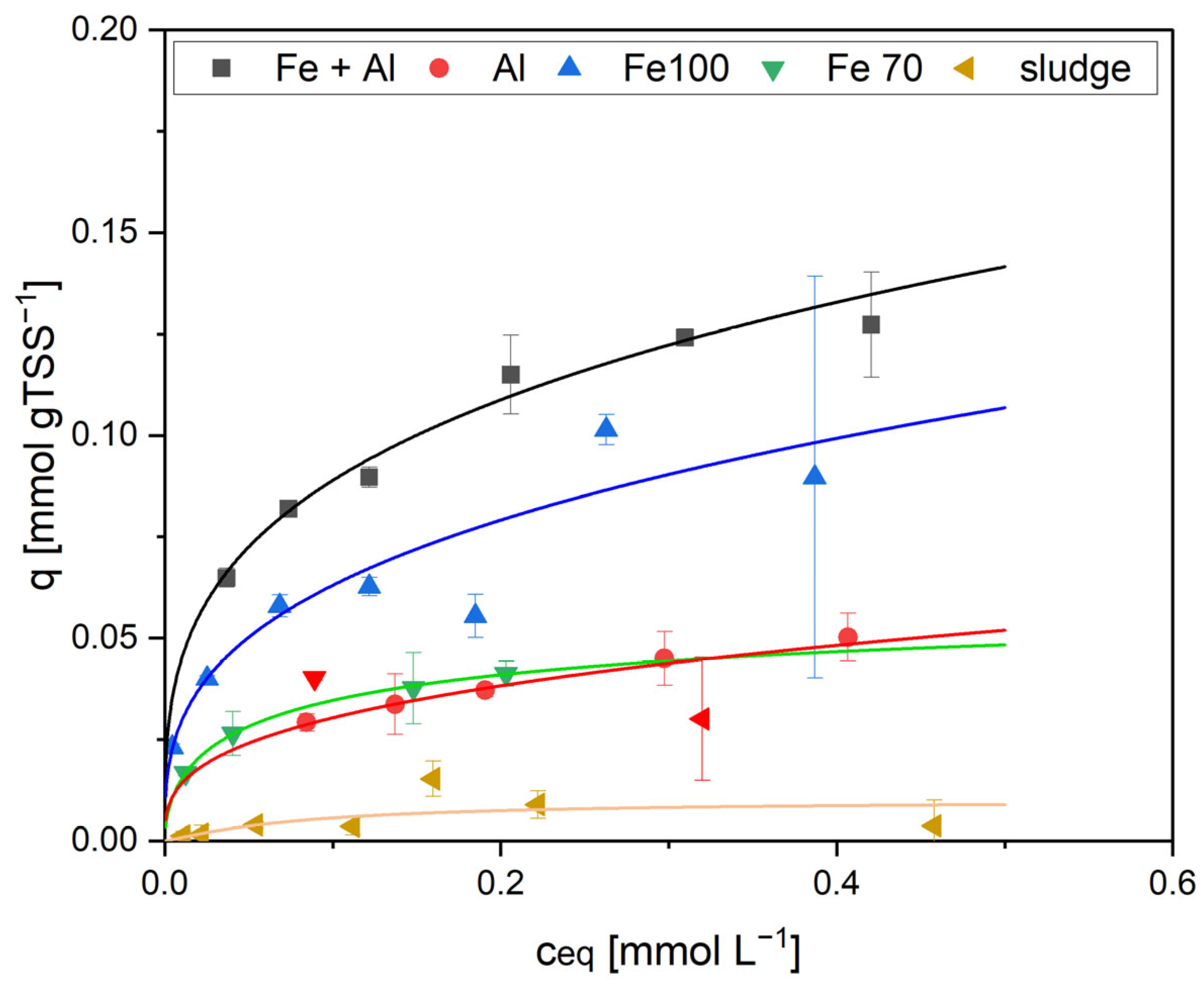

In the static adsorption test, the highest adsorption was measured with sorbent 1, which contained the highest iron content. According to the Langmuir model, the maximum loading for EDTMP was 0.14 mmol gTSS

−1 at

Ceq above 0.42 mmol L

−1 (

Figure 3 and

Table 2). The reduced iron contents of the adsorbents Fe100 and Fe70 resulted in significantly lower adsorption capacities (0.10 mmol gTSS

−1 with Fe100 and 0.05 mmol gTSS

−1 with Fe70).

As the sludge in sorbent 1 also contained Al(OH)

3, an additional test was performed with a sludge containing only Al(OH)

3 (sorbent 2) to distinguish between Fe and Al adsorption. If the sludge contained aluminum only, there was only a slight adsorption (maximum EDTMP loading 0.06 mmol gTSS

−1,

Figure 3). AS 3, which contained no metal hydroxides, had a very low adsorption capacity, and no adsorption isotherm could be calculated (

Figure 3 and

Table 2). This was expected as bacteria in activated sludge are net negatively charged and the phosphonates have the same charge. Therefore, the sludge flocs themselves should not be very suitable as an adsorbent for phosphonates.

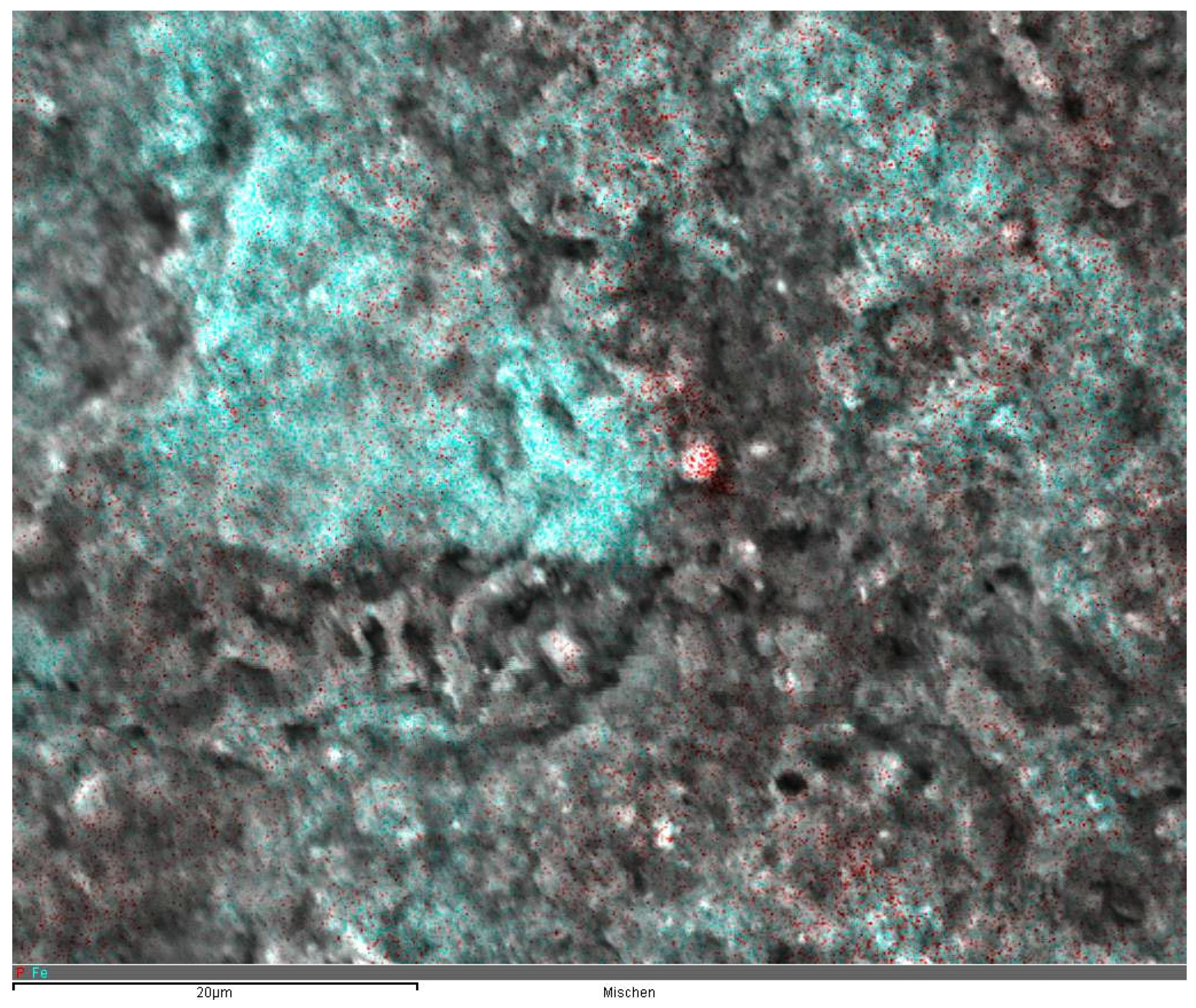

From the first results, it was assumed that the adsorption of phosphonates on activated sludge was mainly caused by the presence of Fe and Al salts. This assumption was supported by the results of the EDX analyses. In the scanning electron microscope, we analyzed different sites of individual sludge flocs for their Fe and P contents. As shown in

Figure 4, the sites of iron and phosphorus accumulation were almost identical. Moreover, the P content at a given site inside the flocs was significantly correlated with the percentage of Fe at the same site (

Figure 5,

Figure S1 and

Table S1 in Supplement). The intercept of 0.21% P (sites with no iron) describes the P content of the organic matter in the flocs, mainly the P content of the bacterial membranes.

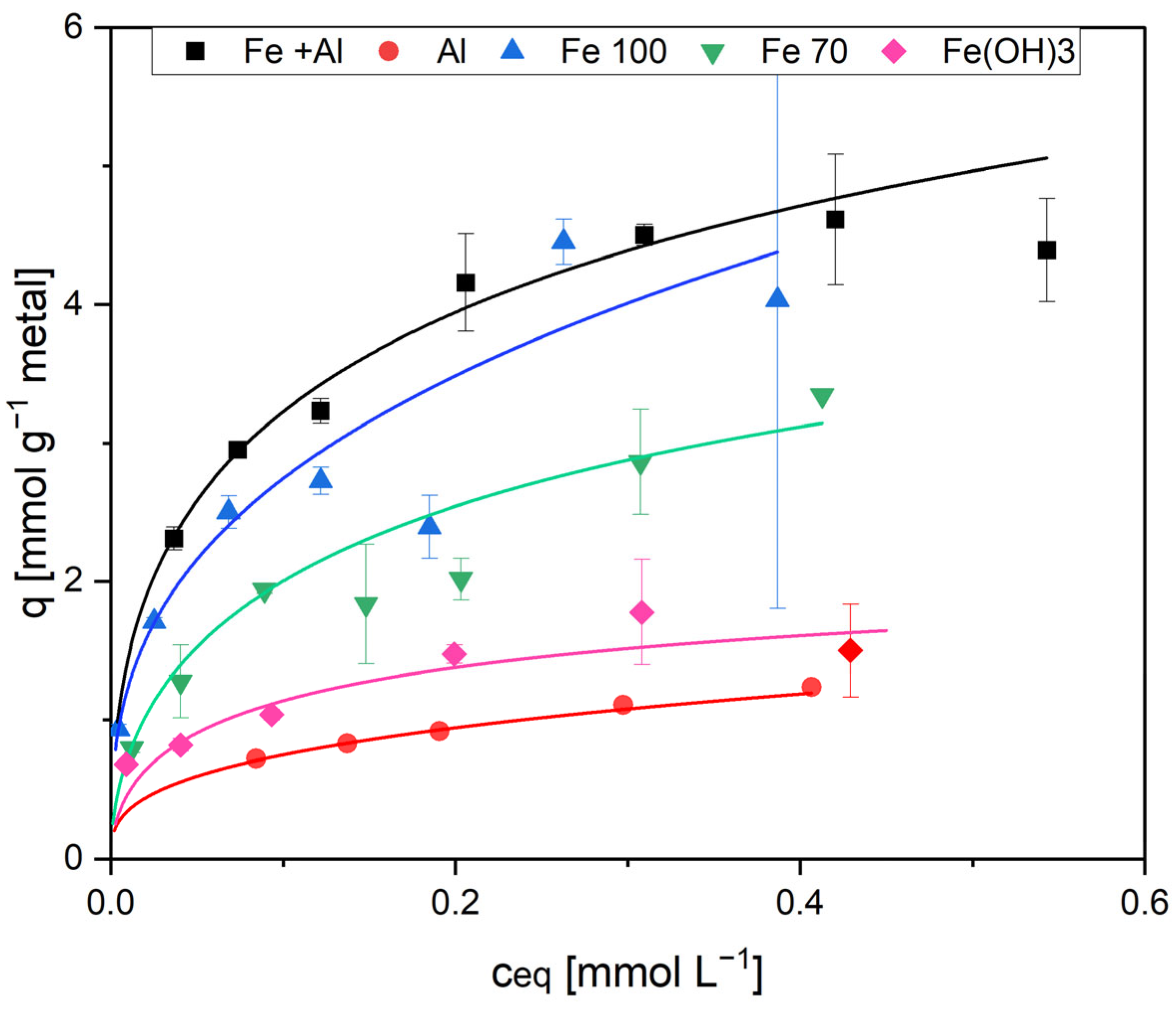

Assuming that only the Fe and Al hydroxides are responsible for the phosphonate adsorption, the adsorption to the metal hydroxides should be comparable, independent from the ratio between metal and organic sludge components. In view of this, the adsorption was calculated on the basis of the dominant adsorbents, Fe and Al. The results for ETDMP are shown in

Figure 6 and

Table 2.

Surprisingly, this was true only for the highest Fe concentrations in the natural Fe- and Al-containing sludge and in the Fe-enriched sludge Fe100. The Fe70 sludge with a lower Fe content showed a significantly reduced loading when calculated on a per-gram Fe basis. The lowest adsorption capacity was measured with pure Fe(OH)3. It is concluded that these differences are the result of different availabilities of the iron surfaces. The available surface area of large ferric hydroxide flocs is comparable small. The same is true when the Fe adsorbent is surrounded by organic sludge components. The latter becomes increasingly important as the Fe content in the sludge decreases.

When comparing Fe and Al hydroxides as adsorbents, the Al was significantly less efficient. Related to the metals as adsorbents, ferric hydroxide was four times more efficient than aluminum hydroxide (

Figure 6). Considering the different molecular weights of the two adsorbents, ferric hydroxide adsorbed six times more phosphonate per mol compared to aluminum hydroxide (0.28 mol EDTMP per mol Fe compared to only 0.045 mol EDTMP per mol Al).

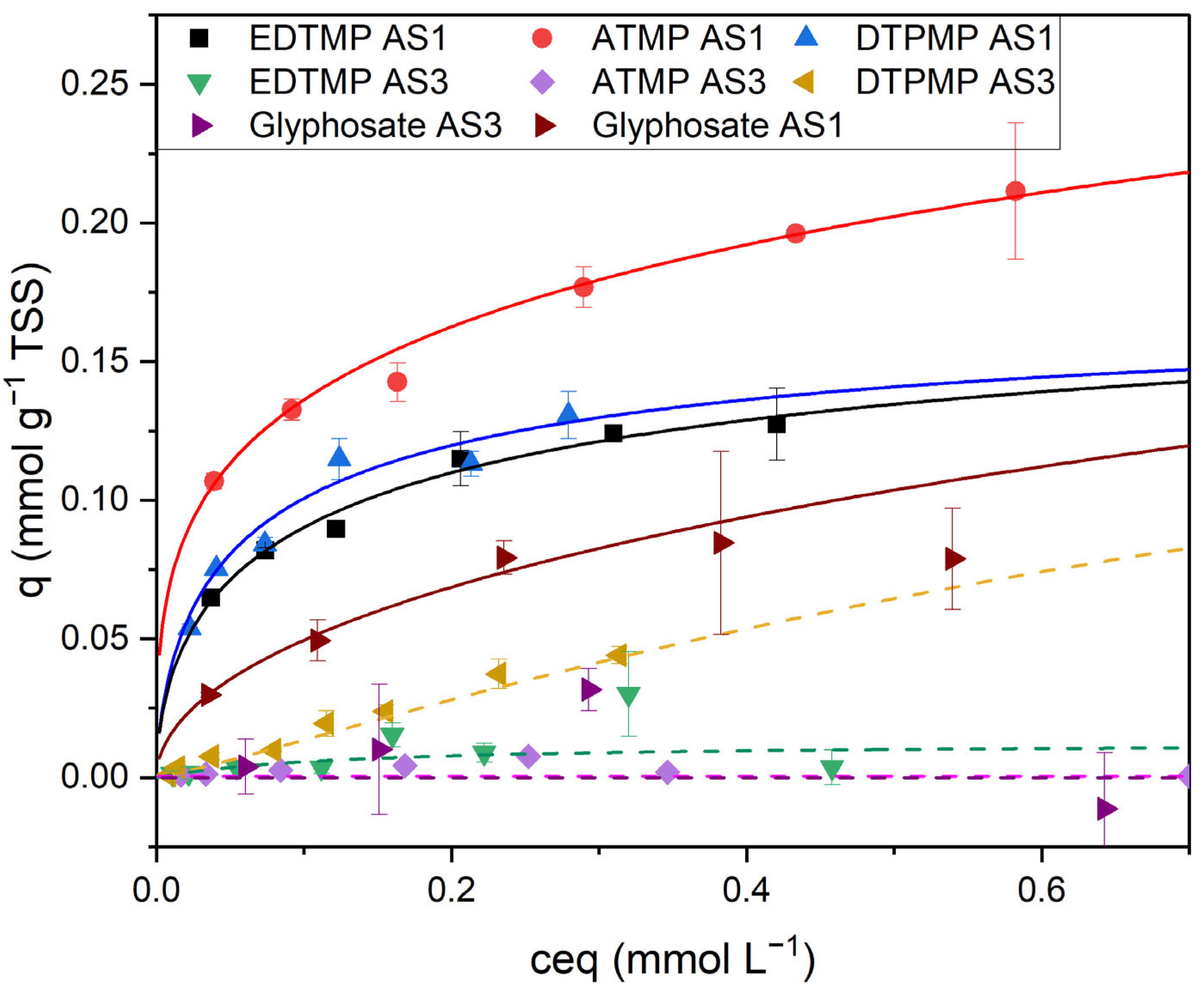

The adsorption characteristics for ATMP, DTPMP, and glyphosate were comparable to EDTMP (

Figure 7). The adsorption of ATMP, EDTMP, and glyphosate on activated sludge without flocculant additives (AS3) was negligible (0.01 mmol gTSS

−1 for ATMP; with glyphosate, no adsorption could be calculated). DTPMP showed a slight adsorption (0.04 mmol gTSS

−1). The adsorption capacity of the sludge was much higher when the sludge contained ferric hydroxides. The highest adsorption was measured for ATMP and AS1 containing ferric and aluminum hydroxides (q max. 0.24 mmol gTSS

−1). The maximum adsorption of EDTMP and DTPMP seemed to be slightly lower. The adsorption of glyphosate followed the Freundlich model. Therefore, no maximum loading could be calculated. In the investigated range between 0 and 340 mg/L glyphosate, the measured maximum load was 0.22 mg gTSS

−1.

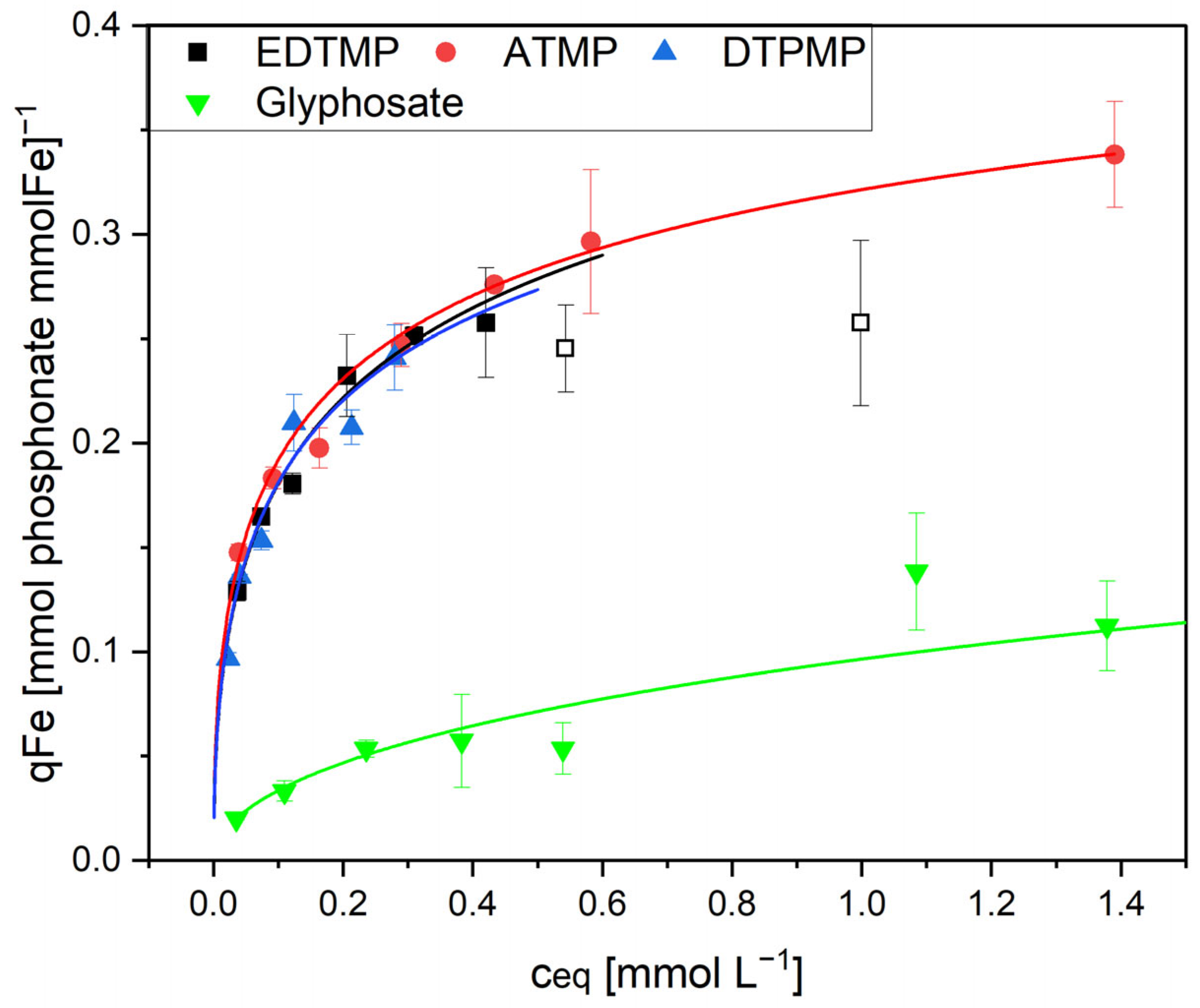

Taking into account the different molecular weights of the phosphonates, the three complexing phosphonates EDTMP, ATMP, and DTPMP showed almost the same adsorption behavior below 0.5 mmol L

−1 dissolved phosphonate (

Figure 8). At higher phosphonate concentrations, the loadings decreased due to an increasing dissolution of the adsorbing metal hydroxides. As a result, adsorption of EDTMP and DTPMP became increasingly unstable. This is reflected, e.g., in increasing confidence intervals in

Figure 9. Under these conditions, no equilibrium concentration was achieved (

Figure 9). The strongest dissolution occurred with DTPMP. At a DTPMP/Fe ratio of 0.25, about 3% of the total iron was released from the sludge flocs. This percentage increased to 5.6% at a DTPMP/Fe ratio of 1.2. At higher ratios, the ferric hydroxide flocs were completely dissolved due to the complexing action of the phosphonate. EDTMP dissolved about 4% Fe at an EDTMP/Fe ratio of 0.25. The portion of dissolved Fe increased to 8.6% at an EDTMP/Fe ratio of 2.4. Complete dissolution occurred at EDTMP/Fe ratios above 3.6. The same was true for ATMP, but the portion of dissolved iron was much lower (1.6% at ATMP/Fe ratio 0.25 and 5.7% Fe dissolution at ATMP/Fe ratio 2.4).

The adsorption of glyphosate was much lower at all concentrations. Moreover, glyphosate did not form metal complexes, and the adsorbent was, therefore, not dissolved (

Figure 8). This indicates different adsorption mechanisms for the complex-forming phosphonates on the one hand and glyphosate on the other.

4. Discussion

This paper describes the adsorption of four phosphonates with different numbers of phosphonate groups on activated sludge. Since the pH in domestic wastewater is normally in the neutral range of pH 7.0 to pH 7.5, this study focused on the adsorption at a neutral pH value. Under these conditions, Nowack and Stone [

26] found a strong correlation between adsorption and the number of phosphonate groups in the molecule. At pH 7.2, the maximum extent of adsorption of different phosphonates on goethite (α-FeOOH) decreased with an increasing number of phosphonate groups from one to five. The highest maximum loading was measured for ATMP (

qmax 30 µmol g

−1), followed by EDTMP (

qmax 26 µmol g

−1) and DTPMP (

qmax 24 µmol g

−1). This relationship between phosphonate groups and the extent of adsorption was later confirmed by Rott et al. [

18]. At a pH of 7.5, the adsorption affinity of polyphosphonates on iron hydroxides and aluminum hydroxides decreased significantly with an increasing number of C-P bonds (HEDP > ATMP > EDTMP > DTPMP). If the adsorption was calculated on the basis of TSS or the iron hydroxide content in the sludge, the results of this study confirm these previous results. Based on the Langmuir model, we calculated maximum loading rates of 5.94 mmol g

Fe−1 for ATMP, followed by EDTMP (4.94 mmol g

Fe−1) and DTPMP (4.74 mmol g

Fe−1). To eliminate 80% of phosphonates, ferric hydroxide was needed in excess (6.8 mmol Fe per mmol ATMP, 7.8 mmol per mmol EDTMP, and 10.3 per mmol DTPMP). These adsorbent requirements were significantly lower than those reported by Rott et al. [

18]. To adsorb 80% of the phosphonates on pure ferric hydroxide flocs, Fe/phosphonate ratios above 20 were required. The adsorbate concentration alone clearly does not sufficiently describe the adsorption of phosphonates in real WWTPs. Adsorption on iron or even aluminum hydroxides in activated sludge may also be affected by surface availability and surface geometry [

17]. In our study, the adsorption capacities of pure ferric hydroxide flocs were significantly lower compared to the same adsorbent concentration within sludge flocs. Compared to real activated sludge from a domestic WWTP (AS1), the adsorption of EDTMP on pure ferric hydroxide was between 3.0-fold (at the highest phosphonate concentration) and 3.4-fold (at phosphonate concentrations below 0.1 mmol L

−1) lower. The scanning electron microscopic images show that ferric hydroxide flocs inside of the activated sludge are smaller and more dislocated compared to the large hydroxide flocs in separated chemical precipitation processes, thus providing a larger available surface for phosphonate adsorption (

Figure 4). This is also supported by the EDX measurements shown in

Figure 4. The assumption also corresponds with results from Reinhardt et al. [

17]. They calculated the maximum adsorption of ATMP onto granular ferric hydroxide to be 16.9 mg per g of sorbent. This was in fact also about four times less than the measured value in this study with iron-containing activated sludge, and it was comparable to the measured adsorption on pure ferric hydride flocs in this study. However, further investigations are required to calculate the effect of the activated sludge on the surface availability of ferric hydroxide.

This study shows that the dominant adsorbing agent in activated sludge is definitely the ferric hydroxide present in the sludge flocs. To a lesser extent, aluminum hydroxide can also provide adsorbing surfaces. The contribution of the organic matter in activated sludge was negligible. Therefore, it could be concluded that phosphonate adsorption can be expected mainly in WWTPs using simultaneous precipitation/flocculation for phosphorus elimination. Considering that the adsorption to the hydroxides in activated sludge is much more efficient compared to hydroxide flocs alone, simultaneous chemical phosphorus elimination should be more efficient than separated precipitation/flocculation. Our findings support the results of Rott et al. [

4], who measured phosphonate removal in a large domestic wastewater treatment plant. The removal of total dissolved phosphonate by secondary clarification ranged from 69.7% to 92.4%. However, this conclusion from lab-scale experiments and some WWTPs needs to be further verified in technical applications. At the same time, further investigations are needed to describe and quantify the modifying effects of different phosphonates on the available metal surfaces in activated sludge flocs. This may help to optimize the elimination of phosphonates in WWTPs and to meet the discharge requirements for total phosphate.

When the best fitting models for calculating adsorption were compared, the Freundlich model described the adsorption better than the Langmuir model at concentrations below 0.4 mmol L

−1 (

Table 2). The homogeneous distribution of adsorption sites proposed by Langmuir does not accurately reflect the adsorbent in activated sludge flocs with its diffuse surface area and composition. The heterogeneous distribution of hydroxide flocs of different sizes embedded in the sludge flocs may represent a spatially uneven distribution of adsorbed phosphonate. Additionally, it must be considered that the surface of the adsorbent itself is modified due to the interaction of adsorption and complexation of metals from the adsorbent. This process can modify the available surface and create new available surfaces during the adsorption process. On the other hand, the sorbent concentration is significantly reduced by the increased dissolution of ferric hydroxide with increasing phosphonate concentrations. To our knowledge, this dissolution process was not taken into account in the earlier studies, e.g., by Chen et al. [

20], Altaf et al. [

12], and Liu et al. [

19]. But it has been already discussed in the study by Rott at al. [

18] for ferric hydroxide. As a result, several investigators preferred an adsorption according to the Langmuir model, suggesting a monolayer mechanism [

12,

16]. In contrast, other studies using lower phosphonate concentrations found the Freundlich model to be more suitable [

17,

20]. In our study, all complexing phosphonates showed the maximum adsorption. This allowed us to fit a Langmuir model. However, we conclude that the adsorption of phosphonates, as recently described by Liu et al. [

19], is more adequately described by the Freundlich model. While the Langmuir model also appears to fit the data, this is likely due to the interaction between the adsorption and dissolution of the adsorbent. This interaction merits further investigation. The interaction of adsorption and dissolution of ferric hydroxides from activated sludge also may explain the comparable uniform releases of glyphosate from WWTPs. At high concentrations, glyphosate may be adsorbed on the sludge flocs and released at low inflow concentrations. Additionally, inflow peak concentrations of complexing phosphonates may displace others from the sludge or may also completely dissolve the adsorbent, thus releasing adsorbed substances like glyphosate.

.png)