1. Introduction

Among the key climate indicators, temperature and precipitation play a vital role in shaping hydrological responses and driving environmental variability. In recent decades, significant attention has been directed toward rising air temperatures and shifting precipitation regimes, as they are essential for understanding regional climate shifts and informing adaptation planning [

1,

2,

3].

The increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events, particularly droughts and floods, are strongly associated with variability in these parameters. Such events pose serious risks to water availability, agricultural productivity, and infrastructure, often resulting in substantial economic losses and social disruptions [

4]. Türkiye is considered one of the most climate-sensitive countries due to its complex topography and transitional climatic characteristics. Consequently, the country is increasingly affected by diverse climate-related challenges: some regions experience abrupt, intense rainfall events leading to floods, while others are subject to prolonged droughts and extreme heat episodes [

5].

To evaluate long-term climate trends, a wide range of statistical methods has been applied across disciplines such as hydrology, agriculture, environmental science, and water resources management [

6]. Among these, the MK test has been widely used due to its non-parametric nature and robustness against non-normality and abrupt changes in time series [

7,

8]. Due to these strengths, it has been extensively applied by researchers for detecting trends in hydro-meteorological studies [

9,

10,

11]. Other common approaches include Spearman’s Rho test and Sen’s slope estimator [

12,

13]. Despite their strengths, these classical methods have limitations in detecting trend structures within different value ranges. Specifically, they are based on rank correlation and assume monotonicity, making them less sensitive to non-linear or hidden trends, especially when data exhibit high variability or opposite behaviors in different sub-ranges.

To address these limitations, Şen (2012) proposed the ITA method, which provides a graphical, assumption-free approach capable of identifying both monotonic and non-monotonic trends across different segments of a dataset [

14]. The ITA method has gained popularity in recent years for its effectiveness in analyzing hydro-meteorological variables such as rainfall, air temperature, streamflow, evaporation, and water quality. Multi-station precipitation trend analyses conducted in different countries reveal that ITA methods provide more sensitive and detailed results at both regional and zonal scales compared to classical approaches [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Studies focusing on extreme precipitation and related events demonstrate that such changes exert pronounced temporal and spatial impacts on critical sectors such as agriculture [

20,

21,

22]. Furthermore, research on drought trends indicates that the integration of classical and innovative methods enables a more comprehensive assessment of drought dynamics, thereby providing significant contributions to water resources management [

23,

24].

This study extends previous research by conducting a comparative evaluation of temperature and precipitation trends on both annual and seasonal scales using two complementary statistical methods, MK and ITA, along with a climograph-based visualization. The novelty lies in jointly applying statistical and graphical approaches to examine how trend directions vary across different data ranges (low, medium, and high values) and how seasonal temperature–precipitation interactions evolve throughout the year. This integrative framework enables a more detailed interpretation of intra-annual variability and helps identify subtle trend structures that conventional monotonic tests may overlook.

The main objective of this study is to evaluate seasonal and annual temperature and precipitation trends based on long-term observations from seven meteorological stations located in the Upper Yeşilırmak and Çekerek sub-basins of the Yeşilırmak Basin, Türkiye. By employing both the Mann–Kendall and Innovative Trend Analysis methods, the study aims to statistically and structurally characterize climate-driven changes in hydro-meteorological variables and to offer a scientific basis for regional climate risk assessment and the formulation of adaptation strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The Yeşilırmak Basin (see

Figure 1) was selected for the study due to its wide range of climatic and topographical conditions extending from coastal to inland regions. Furthermore, given its strategic importance for agricultural production, water resource management, and regional development, identifying climatic trends within the basin will offer valuable insights for local administrations and policymakers in the context of climate adaptation and sustainable planning.

Situated within the transitional zone between the humid, rainy Black Sea climate and the arid, harsh continental climate of Central Anatolia, the basin is located in the Black Sea Region of Türkiye, approximately between 40°20′–41°50′ north latitudes and 35°00′–37°20′ east longitudes. Although the basin is generally influenced by the Black Sea climate due to its geographical location, its wide topographical range—from humid coastal areas to drier inland zones—leads to substantial spatial variations in temperature and precipitation. The coastal areas along the Black Sea are characterized by a humid, mild, and rainy climate; in contrast, the regions closer to Central Anatolia exhibit lower humidity, arid conditions, and more severe continental characteristics. In mountainous zones, cold and humid conditions prevail [

25].

Average annual temperatures range between 10 °C and 14 °C, with values decreasing as both elevation and distance from the sea increase. During summer, regional temperatures may rise to between 24 °C and 30 °C, while winter months often bring frost events, with temperatures dropping below 0 °C. In terms of precipitation, annual totals in the sub-basins typically range from 400 mm to 600 mm. Precipitation levels are generally higher along the coast, while the interior regions experience lower and more irregular rainfall [

26,

27]. The spatial distribution of the temperature and precipitation stations used in this study across the basin is presented in

Figure 1.

2.2. Data

Meteorological data obtained from the Turkish State Meteorological Service (TSMS) covering 38 years (1975–2012) were analyzed. The dataset includes records from seven distinct meteorological stations across the basin—five with temperature data and four with precipitation data, with Tokat and Dökmetepe stations providing both parameters. As shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, average annual values appear relatively uniform across all the stations.

2.3. Randomness Test

The test is a non-parametric test originally defined by McGhee (1985) [

28]. It is later adapted and applied by Adeloye and Monteseri (2002) [

29]. The steps of the test are as follows:

The median of the dataset is calculated after ordering the values in ascending order. For a sample size n, where n = 2k (even) or n = 2k + 1 (odd), with k being an integer, the sample median is denoted by

and is computed as follows:

Each data point is then evaluated to determine whether it exceeds the median value. If a data point exceeds the median, it is considered a success and denoted by S. If it does not exceed the median, it is considered a failure and denoted by F.

Let the number of successes be denoted by n1 and the number of failures by n2. In general, the total number of observations is given by excluding the values that are exactly equal to the median.

The total number of runs in the dataset is then determined. A run is defined as a sequence of consecutive S values interrupted by an F, denoted as S

s or a sequence of consecutive F values interrupted by an S, denoted as F

f. The total number of such runs observed in the sequence is represented by R.

Under the null hypothesis H0, which assumes that the sequences of Ss and Ff are random, the test statistic z follows a standard normal distribution. Therefore, for a chosen significance level (α), the critical values of the standard normal distribution are determined and denoted by ±zα/2.

If the calculated Z value falls outside the interval ±zα/2, it indicates a lack of statistical evidence supporting the randomness of the data. This result suggests that the series exhibits persistence or continuity, implying that it may be suitable for modeling using various time series approaches. The confidence interval values used for this method are presented in

Table 3.

The Randomness Test was applied as a preliminary diagnostic step to assess the statistical independence and persistence characteristics of the time series. The identification of all station series as non-random (persistent) indicates that the temperature and precipitation records exhibit systematic temporal continuity rather than purely random fluctuations. This outcome is particularly important for both the Mann–Kendall and Innovative Trend Analysis methods, as persistent series are known to yield more reliable and interpretable trend signals. Therefore, the Randomness Test was employed to confirm the suitability of the datasets for subsequent trend detection and to ensure the statistical validity of the applied trend analyses.

2.4. Mann–Kendall Test

It is a non-parametric test used to identify the presence of a trend in a time series. The MK test statistic, denoted as S, represents the difference between the number of positive and negative differences and is calculated as follows:

Here, xi and xj represent sequential data values, n denotes the total number of observations, and sign refers to the sign function, which is computed as follows:

After calculating the Mann–Kendall test statistic S the variance of S is computed to assess the significance of the trend. The variance Var (S) is given by the following formula:

t: is the number of data points in the tth tied group.

n: is the total number of data

Finally, the standardized test statistic Z, which follows the standard normal distribution, is calculated as follows [

31,

32,

33]:

The calculated Z values were interpreted based on the classification of Mann–Kendall Z values presented in

Table 4, which provides a framework for assessing the direction and significance of trends.

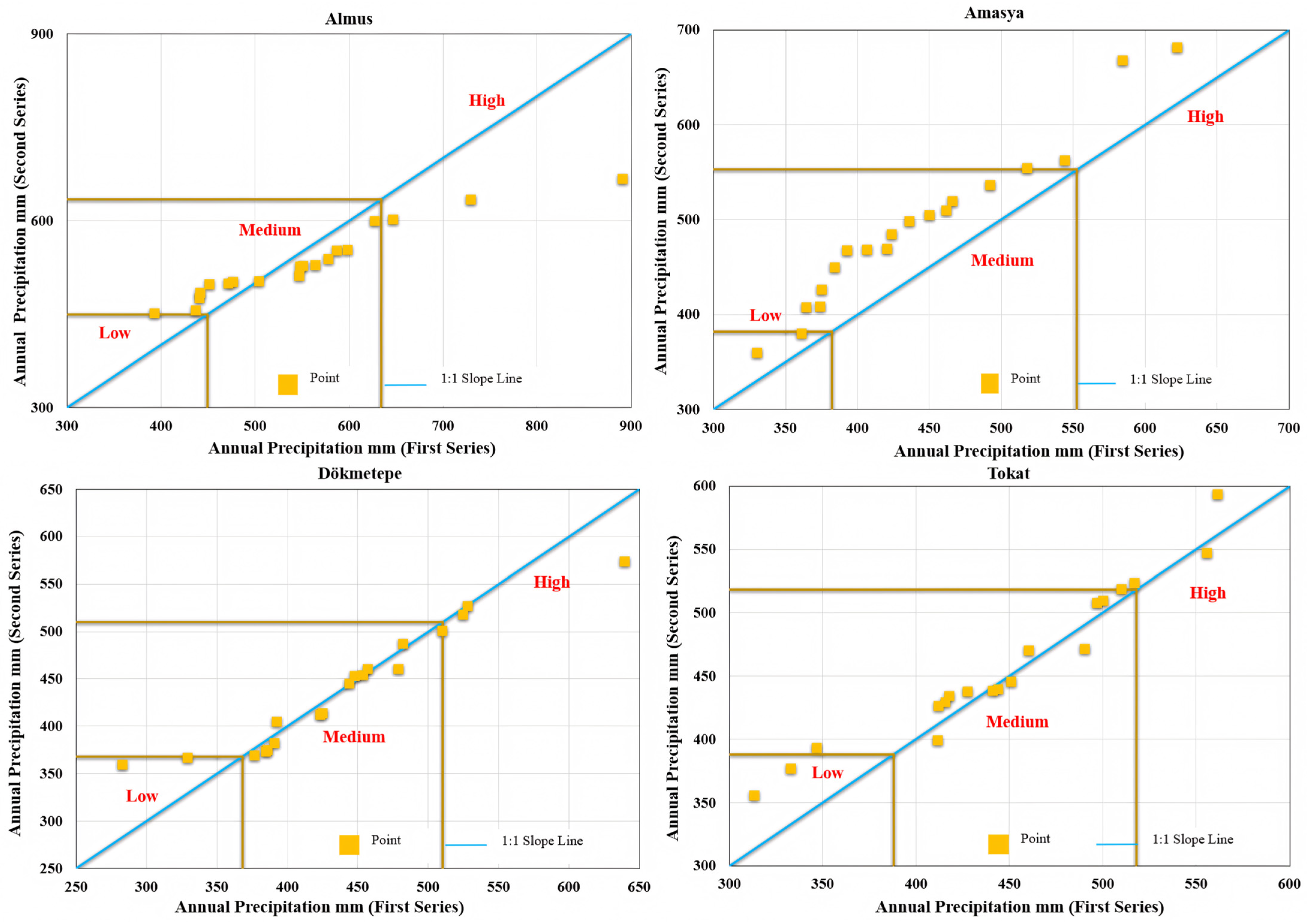

2.5. Innovative Trend Analysis

The method developed by Şen (2012) was specifically designed to identify trends in climatic data [

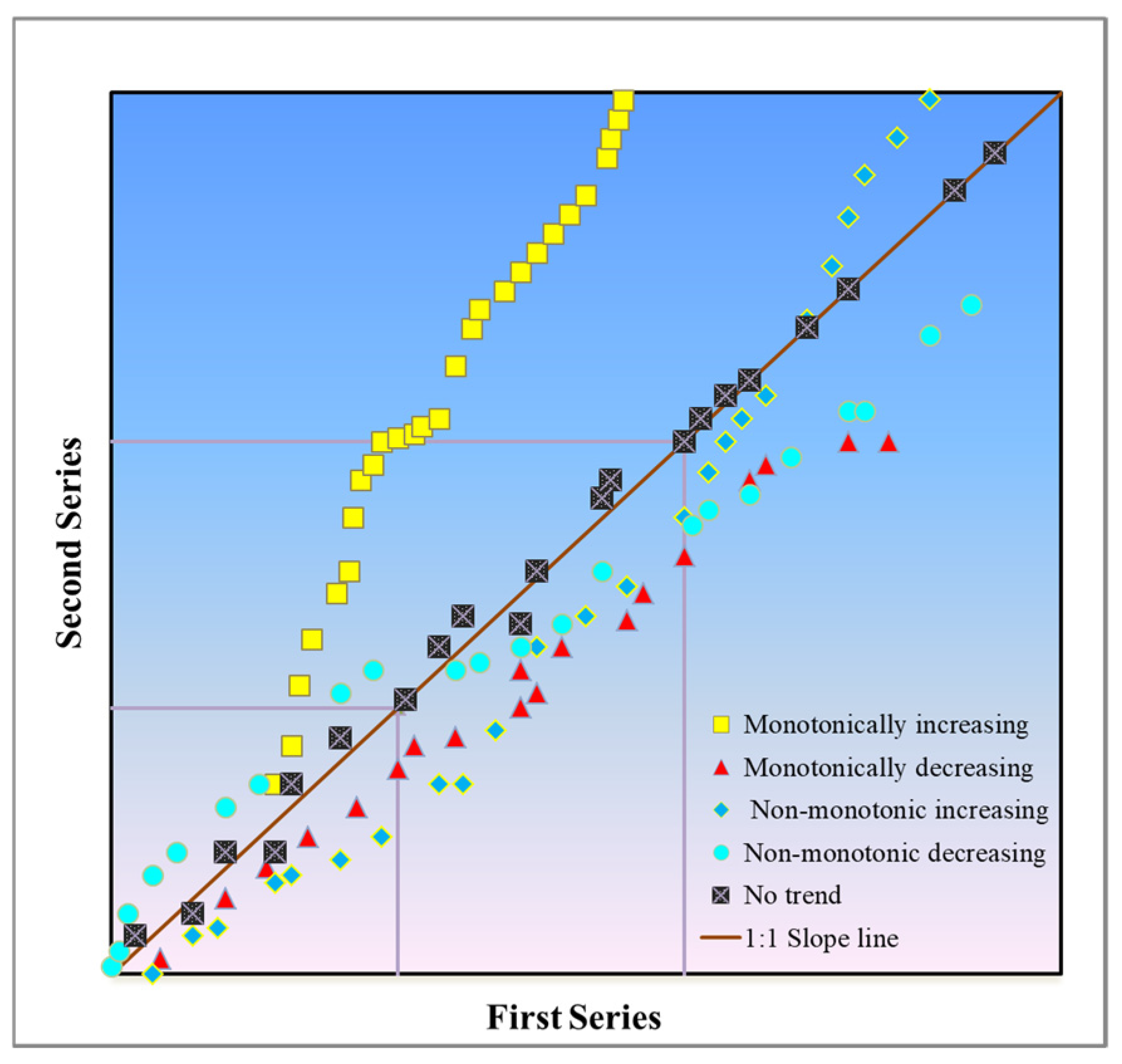

14]. It is free from restrictive statistical assumptions and recommends using a minimum of 30 years of data. The dataset is divided into two equal parts to form two series, each of which is ordered in ascending order. The first series is plotted on the horizontal axis of a Cartesian coordinate system, while the second series is plotted on the vertical axis. A 1:1 slope reference line is then drawn to visually assess the distribution of data points. This method also allows for evaluating trends separately within low, medium, and high data subsets. When the 1:1 line is drawn, the Cartesian plane is effectively divided into two regions: data points above the line indicate an increasing trend, whereas those below the line suggest a decreasing trend [

35]. An illustrative example used to determine data trends is presented in

Figure 2.

Despite its advantages, the ITA method also has certain limitations. Since the method is based on graphical interpretation, it is sensitive to outliers; extreme high or low values in the dataset may influence the visual perception of zonal trend behavior. Therefore, prior to the analysis, all datasets were carefully screened, and extreme values were evaluated in relation to physical consistency and climatological plausibility.

Moreover, the classification of low, medium, and high value ranges is an inherent consequence of the methodological structure of ITA, which relies on dividing the dataset into two equal sub-series. These zones represent the lower, central, and upper portions of the data distribution and allow for the assessment of how trends behave across different magnitude intervals. This feature enables ITA to provide a more flexible and value-range-sensitive trend evaluation compared to classical monotonic trend tests.

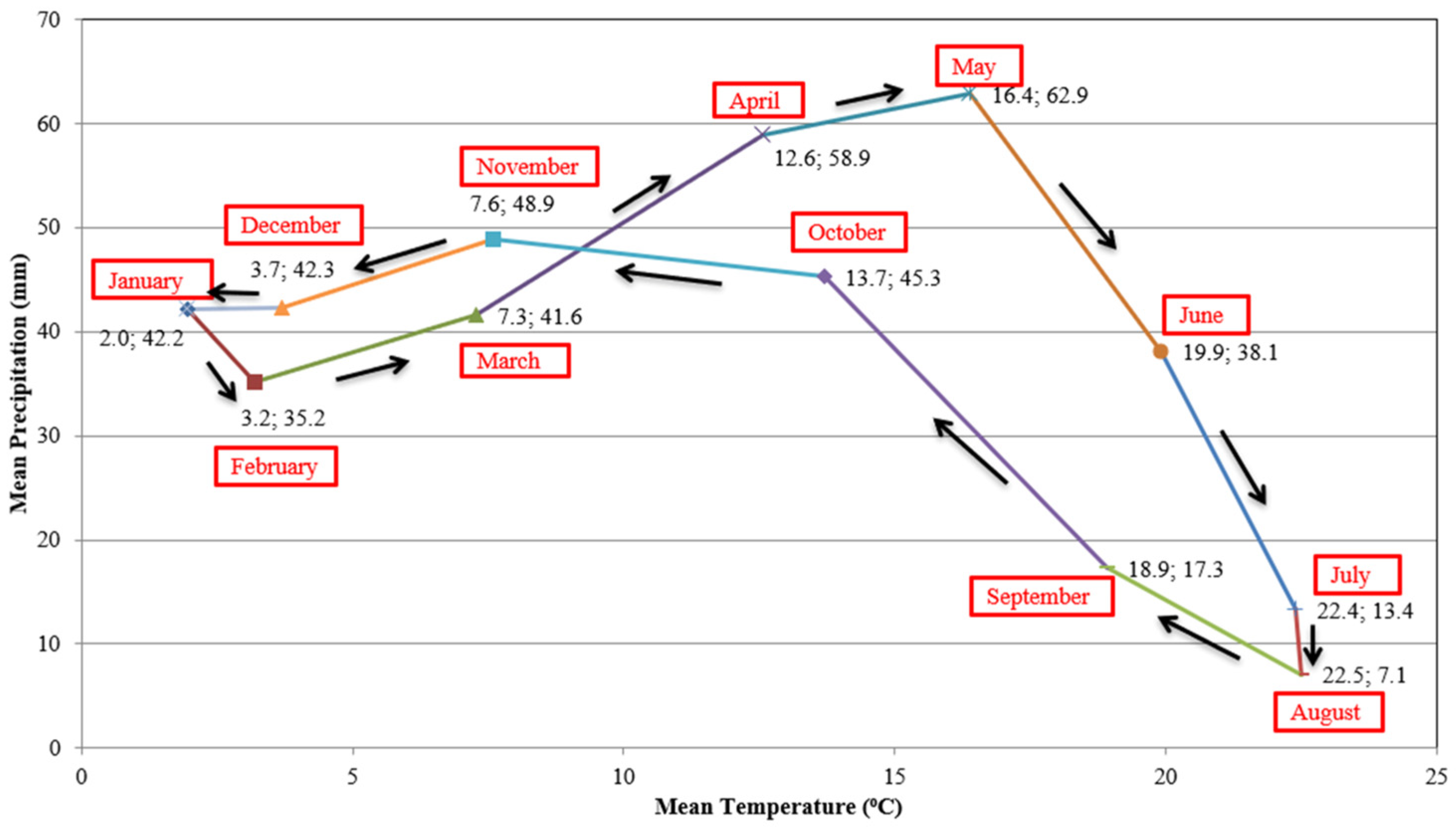

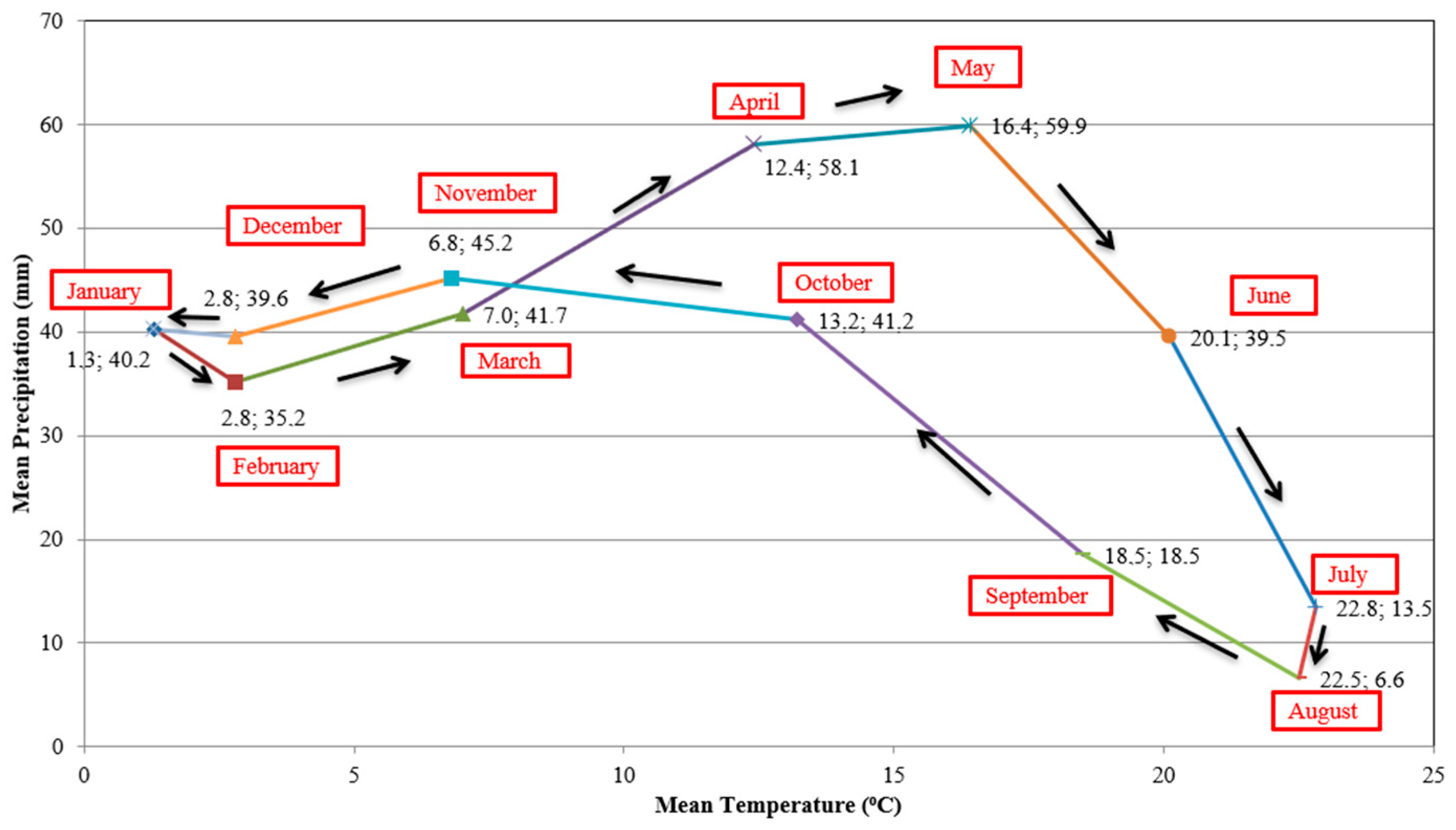

2.6. Climograph

To complement the statistical trend analyses, a climograph approach was applied to visually examine the seasonal relationship between precipitation and temperature in the Yeşilırmak Basin. This analysis was conducted for the Tokat and Dökmetepe meteorological stations, where both precipitation and temperature data were simultaneously available. These two stations were selected as they adequately represent the climatic conditions of the basin.

For each selected station, monthly mean precipitation and temperature values for the period 1975–2012 were plotted on scatter diagrams. Each point was labeled with its corresponding month, and the points were connected sequentially in calendar order, forming polygonal paths. The slope, direction, and geometry of these polygons provide insights into seasonal climatic behavior:

Slope Interpretation: A slope of approximately 45° reflects proportional variability between precipitation and temperature; steeper or flatter slopes indicate dominance of one variable over the other.

Directional Arrows: Upward-directed connections between months represent direct correlations, while downward-directed paths indicate inverse correlations.

Polygon Geometry: Narrow and elongated polygons imply a strong and consistent relationship between the variables; wide polygons indicate non-linear associations.

Point Spacing: Short distances between consecutive months suggest stable climatic conditions, while longer distances indicate higher variability.

Seasonal Diagnostics: The polygonal trajectories highlight seasonal transition patterns, enabling the identification of periods with consistent proportionality and potential anomalies.

This climograph-based assessment enhances the methodological framework by visually illustrating the seasonal dynamics of precipitation–temperature interactions at representative stations, thereby supporting and contextualizing the Mann–Kendall and Innovative Trend Analyses presented in subsequent sections.

In this study, climograph analysis could only be carried out for the Tokat and Dökmetepe stations because these are the only locations within the basin that provide long-term simultaneous temperature and precipitation records. This restriction arises from data availability constraints rather than methodological preference. However, both stations are situated within the climatic transition zone between the humid Black Sea region and the semi-arid Central Anatolia region. Therefore, they adequately represent the dominant seasonal hydro-climatic characteristics of the Yeşilırmak Basin. Although the climograph does not capture the full spatial variability of the basin, it provides a reliable diagnostic visualization of seasonal temperature–precipitation interactions under semi-arid continental conditions.

4. Discussion

The MK and ITA results based on temperature data reveal a strong consistency, particularly during the summer and autumn seasons across all stations. The MK test identified statistically significant increasing trends above the 90% confidence level in these periods (e.g., Tokat in summer: Z = 3.79; Reşadiye: Z = 3.37). These findings were further supported by ITA results, which confirmed the presence of “monotonic” or “non-monotonic” increasing trends, with data clusters concentrated in the medium- to high-temperature zones. Together, these results indicate that seasonal warming is both statistically and distribution-based.

In spring, the MK test detected significant upward trends at Zile (Z = 1.80) and Reşadiye (Z = 1.86), while Turhal and Dökmetepe exhibited negative but statistically insignificant Z-values. However, the ITA method complemented the MK results by identifying increasing trend structures in low- to medium-temperature ranges, even in stations where MK fell below the significance thresholds. In this way, ITA was able to capture emerging patterns that were not fully detected by the classical analysis.

During the winter season, the MK test suggested marginally significant positive trends only at Zile and Reşadiye (Z ≈ 1.0), while other stations showed weak and statistically insignificant tendencies. In contrast, ITA detected consistent upward trends concentrated in the low-temperature zones across all stations, indicating a decline in extreme cold events.

Regarding annual temperature trends, the MK test revealed statistically significant positive trends at all stations (e.g., Tokat: Z = 2.56; Zile: Z = 3.09). ITA corroborated these trends at the distribution-based level, showing a consistent upward pattern especially concentrated in the mid to high-temperature ranges. This indicates that annual warming in the region is progressing with a long-term and stable trajectory.

In the case of precipitation analyses, a strong agreement was observed between the MK and ITA methods during the autumn season. The MK test identified increasing trends at the 80–90% confidence level in Amasya (Z = 1.78), Tokat (Z = 1.60), Dökmetepe (Z = 1.45), and Almus (Z = 1.10). These trends were structurally confirmed by the ITA method, which revealed both monotonic and non-monotonic increasing patterns, with data points concentrated primarily in the low- to medium-precipitation zones.

In the spring season, the MK test indicated only weak positive trends at Amasya (Z = 0.96) and Tokat (Z = 0.81), while no significant trends were detected at the remaining stations. However, ITA graphically identified increasing trends across all four stations, particularly in the lower precipitation ranges, thereby capturing subtleties that the MK test was unable to detect, highlighting ITA’s greater sensitivity to trend formation at the distribution-based level.

During the summer and winter seasons, the MK test largely failed to identify statistically significant trends, reporting values such as Tokat summer (Z = 0.44) and Amasya winter (Z = 0.13). Despite this, the ITA method was able to reveal weak but persistent increasing trends, especially within the low precipitation zones, providing valuable visual evidence of ongoing shifts in seasonal precipitation behavior.

In the annual precipitation analyses, the MK test showed positive trends at Amasya (Z = 1.33), Tokat (Z = 1.06), and Dökmetepe (Z = 1.03). These trends were structurally reinforced by the ITA method, which illustrated a long-term upward tendency through the clustering of data points in the low- to medium-precipitation ranges. This consistency across methods emphasizes the presence of a subtle yet gradually intensifying change in annual precipitation patterns.

Overall, the MK and ITA methods demonstrated strong consistency in detecting pronounced trends, particularly at the seasonal peaks and annual scale. However, in cases where trends were of low intensity or near the threshold of statistical significance, the ITA method provided more nuanced insights due to its graphical sensitivity and ability to assess zonal distributions. Consequently, ITA emerged as a complementary and interpretive enhancement to the MK test, offering a more detailed understanding of subtle or evolving climatic trends.

Although the additional trend detections obtained by ITA in cases where the Mann–Kendall test was statistically inconclusive are not based on formal hypothesis testing, they provide important structural insight into the internal distribution of the time series. By separately evaluating low, medium, and high value ranges, ITA is able to reveal weak or emerging zonal patterns that may remain hidden when a single monotonic test is applied to the entire dataset. Therefore, the higher detection rate achieved by ITA should be interpreted as an indicator of its diagnostic sensitivity to subtle trend behavior rather than as a replacement for statistical significance testing. In this context, ITA functions as a complementary interpretive tool that enhances the physical and pattern-based hydro-climatic variability derived from MK-based results.

The findings of this study are largely consistent with those reported in both national and international literature on climate trend analysis. In particular, the strong agreement observed between the MK test and the ITA method during the summer and autumn seasons has been frequently documented in previous studies. For instance, Serencam (2019) applied both the MK and ITA methods to long-term temperature and precipitation data in the Yeşilırmak Basin and identified statistically significant warming trends, especially in summer and autumn months [

36]. The study also emphasized the effectiveness of ITA in capturing weak trend signals that might otherwise remain undetected.

Similarly, Şan (2025) highlighted that when applied to temperature and precipitation datasets, ITA methods provided more sensitive and visually interpretable insights into the direction and magnitude of trends, particularly in capturing seasonal and temporal variations compared to the classical MK test [

37]. These findings underscore ITA’s value as a complementary tool that enhances and refines the interpretation of climatic trend analyses.

In the Jinsha River Basin in China, Dong et al. (2020) employed the ITA method in conjunction with the MK test to examine temperature and precipitation trends over the period 1961–2016 [

38]. Their findings revealed significant increasing trends in both annual and seasonal temperatures, with ITA providing more detailed insights compared to classical methods, particularly by capturing trend behavior across low, medium, and high data zones.

Similarly, in Central Asia, Alifujiang et al. (2021) analyzed annual and seasonal streamflow data from the Issyk-Kul Lake Basin using both ITA and MK tests [

39]. The combined use of these two methods enabled a more reliable detection of weak or complex trend structures, demonstrating the effectiveness of ITA as a complementary tool in cases where traditional methods may fall short.

The detected warming trends, particularly at the annual scale and during the summer season, have important implications for water resources and agriculture in the Yeşilırmak Basin. Higher temperatures are expected to increase evapotranspiration rates and crop water demand, thereby intensifying pressure on existing irrigation schemes and reservoir operations. In combination with the observed shifts in seasonal precipitation, such as changes in spring and autumn rainfall, the timing and magnitude of surface runoff may be altered, affecting the reliability of water supply for both agricultural and domestic uses. These changes could also exacerbate drought risk, increase the frequency of low-flow conditions, and reduce the effectiveness of current water allocation and planning strategies. From a management perspective, the results highlight the need for more flexible reservoir operating rules, improved irrigation scheduling, and the integration of climate-informed indicators into drought early-warning systems.

When compared with previous studies conducted in the Yeşilırmak Basin and neighboring regions of Türkiye, the trends identified in this study are largely consistent with the documented warming signal and the spatially heterogeneous behavior of precipitation in semi-arid and transitional climatic zones. Earlier research has reported similar tendencies towards increasing temperatures, more frequent warm extremes, and regionally variable precipitation responses, especially in basins influenced by the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea circulation patterns. Furthermore, regional climate model projections for Türkiye and the Eastern Mediterranean generally indicate continued warming and an elevated likelihood of more frequent and intense drought episodes, particularly under higher emission scenarios. In this context, the trend structures revealed by MK and ITA not only corroborate these model-based expectations but also provide observational evidence that recent hydro-climatic changes in the Yeşilırmak Basin are already evolving in a direction consistent with future climate projections. This reinforces the urgency of incorporating climate-aware risk assessments into basin-scale water and agricultural planning.

The detected temperature and precipitation trends are physically consistent with the dominant regional climate dynamics of the Yeşilırmak Basin. The pronounced summer–autumn warming aligns with the IPCC-reported positive temperature anomalies over the Eastern Mediterranean and reduced snow-cover duration across northern Anatolia, which weaken thermodynamic cooling and amplify continental heat accumulation. The autumn precipitation increases correspond to enhanced sea–land thermal contrasts over the Black Sea, strengthening moisture advection toward the basin during transitional months. Mild winter warming observed in low-value clusters is consistent with the documented decline in extreme cold-air outbreaks and reduced persistence of continental high-pressure systems. Overall, the spatial and seasonal patterns detected by MK and ITA reflect mechanisms that are coherent with large-scale atmospheric circulation changes affecting northern Türkiye.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated annual and seasonal temperature and precipitation trends in the Yeşilırmak Basin using the Mann–Kendall (MK) test and the Innovative Trend Analysis (ITA) method based on a 38-year dataset (1975–2012). The main outcomes of the analyses are summarized below, followed by a brief supporting discussion. Key findings can be summarized as follows:

Statistically significant warming was detected in summer and autumn at all stations, while spring and winter exhibited weaker warming concentrated in low-value zones.

Annual temperature trends were positive and consistent across all stations, with strong agreement between MK and ITA.

No consistent decreasing trend in precipitation was observed; however, autumn showed increasing precipitation at several stations, and ITA identified weak trends missed by MK.

ITA confirmed most MK results (92% consistency) and revealed additional trend structures in 83% of cases where MK was statistically inconclusive.

Climograph analyses revealed strong seasonal contrasts with direct implications for water management and drought risk.

Statistically significant warming was detected in summer and autumn at all stations (confidence > 90%). Spring and winter exhibited weaker warming, primarily in low-value zones, suggesting a decline in cold extremes. Annual temperature trends were positive and consistent across all stations, with MK and ITA in strong agreement.

Precipitation results were more variable across seasons and locations. No consistent decreasing trend was observed; however, autumn showed increasing precipitation trends at several stations. ITA outperformed MK in identifying weak trends, particularly in low- and mid-precipitation zones during spring and winter. Annual precipitation trends were weak but displayed clearer upward patterns through ITA.

When comparing the two methods, ITA confirmed the majority of statistically significant MK results (92% consistency) and further revealed additional structural trend patterns in 83% of cases where MK was statistically inconclusive, highlighting its complementary diagnostic sensitivity rather than implying independent statistical significance. ITA was effective in revealing structural and zonal characteristics, making it a valuable complement to MK.

The climograph evaluation provided additional insight into the basin’s climatic regime. Climograph analyses showed that May precipitation was 40–50% higher than winter levels and that August precipitation was approximately 89% lower than in May, while temperatures increased by about 20 °C from January to July. The strong seasonal similarity at both stations confirms their representativeness for the Yeşilırmak Basin and highlights important implications for water management and drought risk.