Analysis of the First Flush Effect of Rainfall Runoff Pollution in Typical Livestock and Poultry Breeding Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

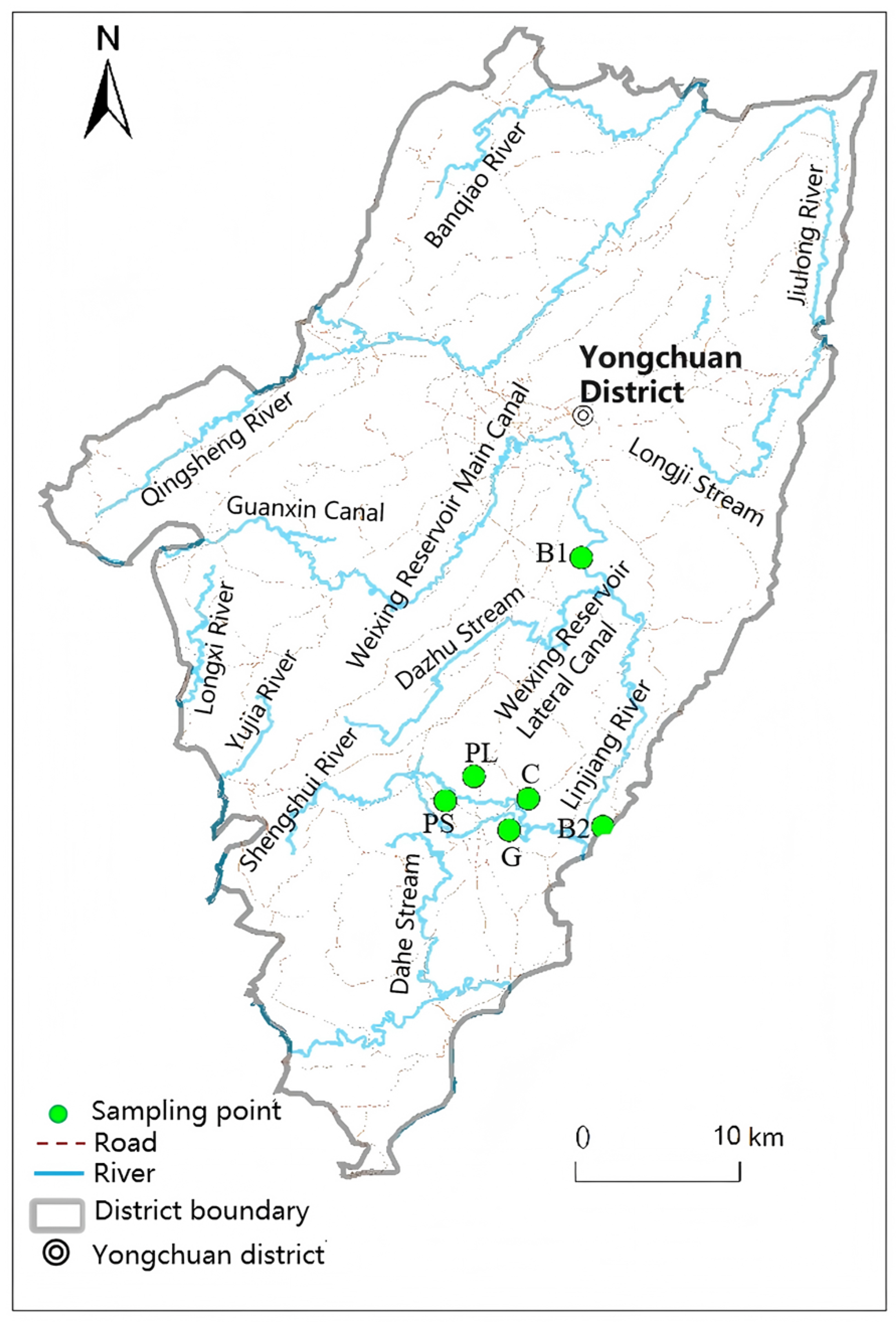

2.1. Sampling Site Selection

2.2. Apparatus and Sample Collection

2.3. Sample Analysis

2.4. Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

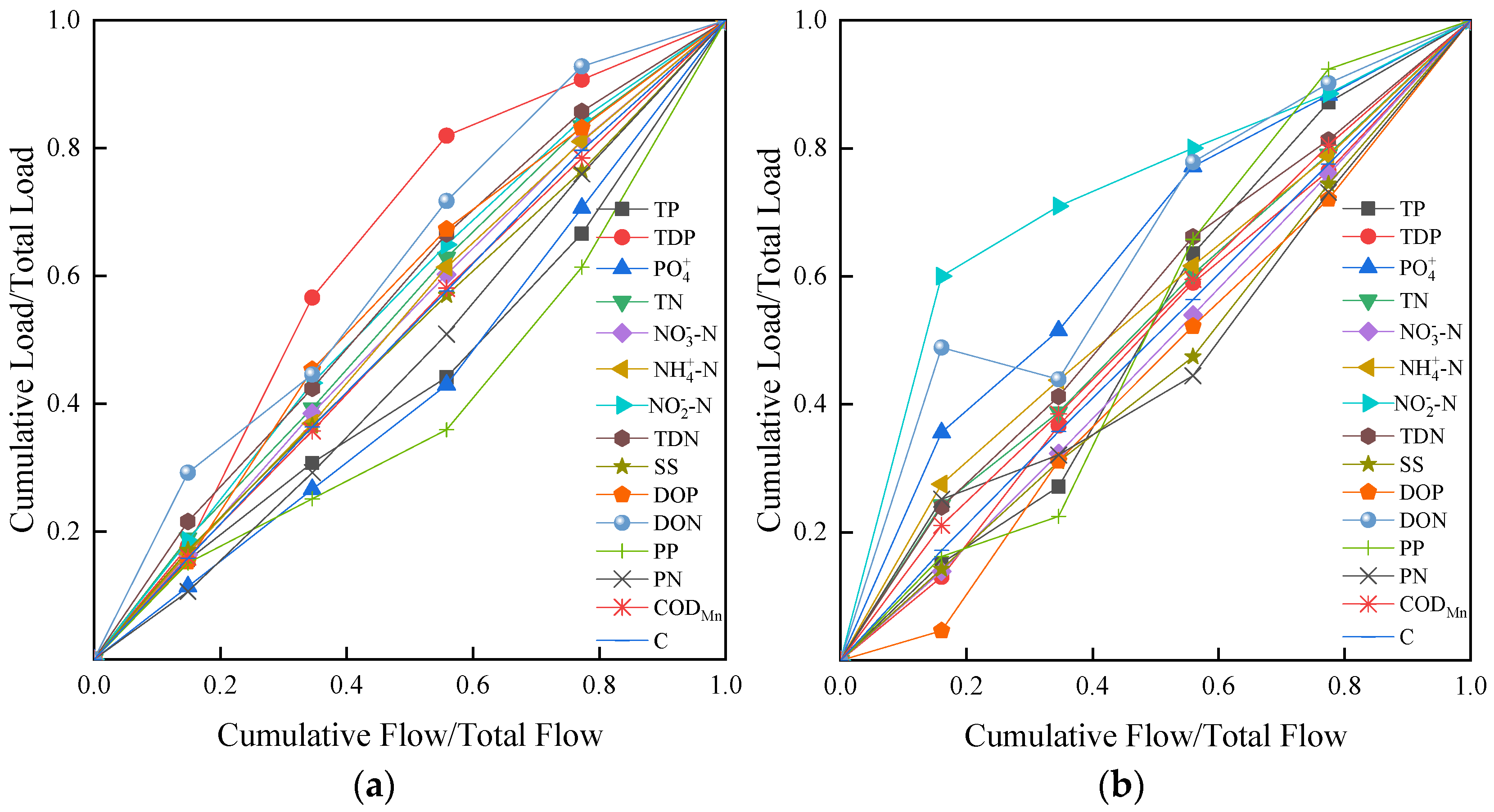

3.1. Screening of Indicators for the First Flush Effect in Rainfall Runoff

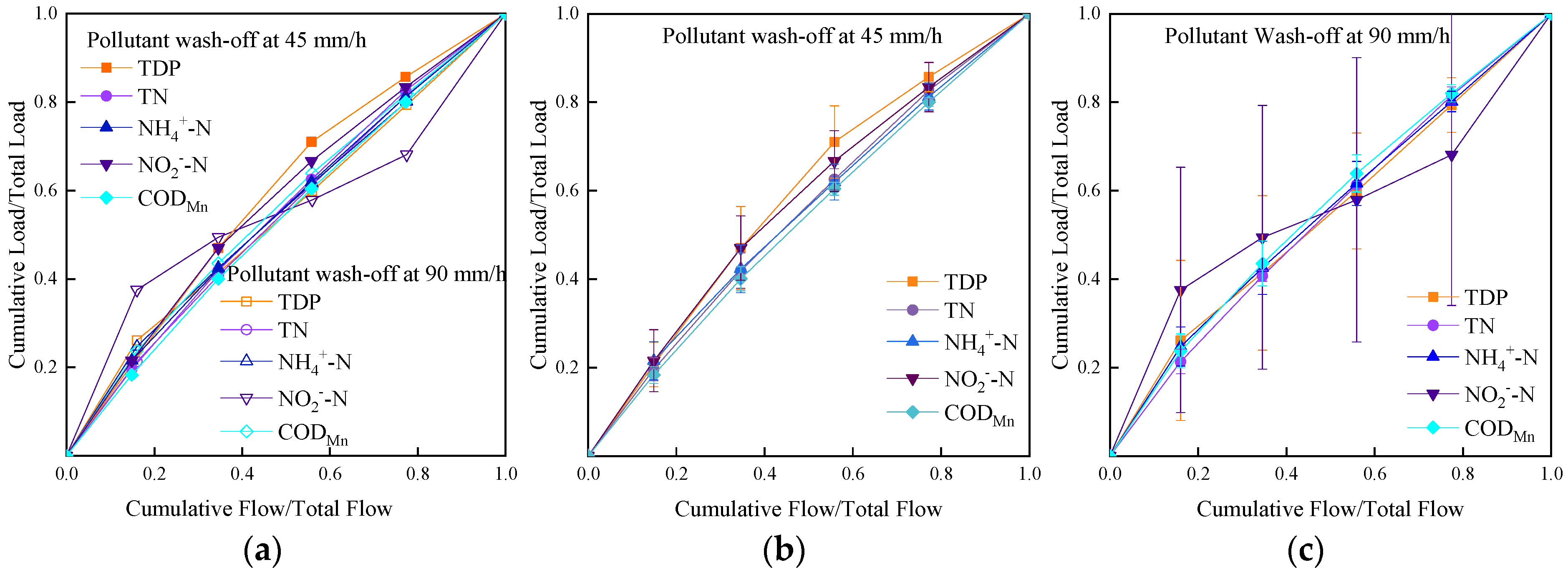

3.2. The Influence of Rainfall Intensity on the First Flush Effect from Livestock and Poultry Breeding Areas

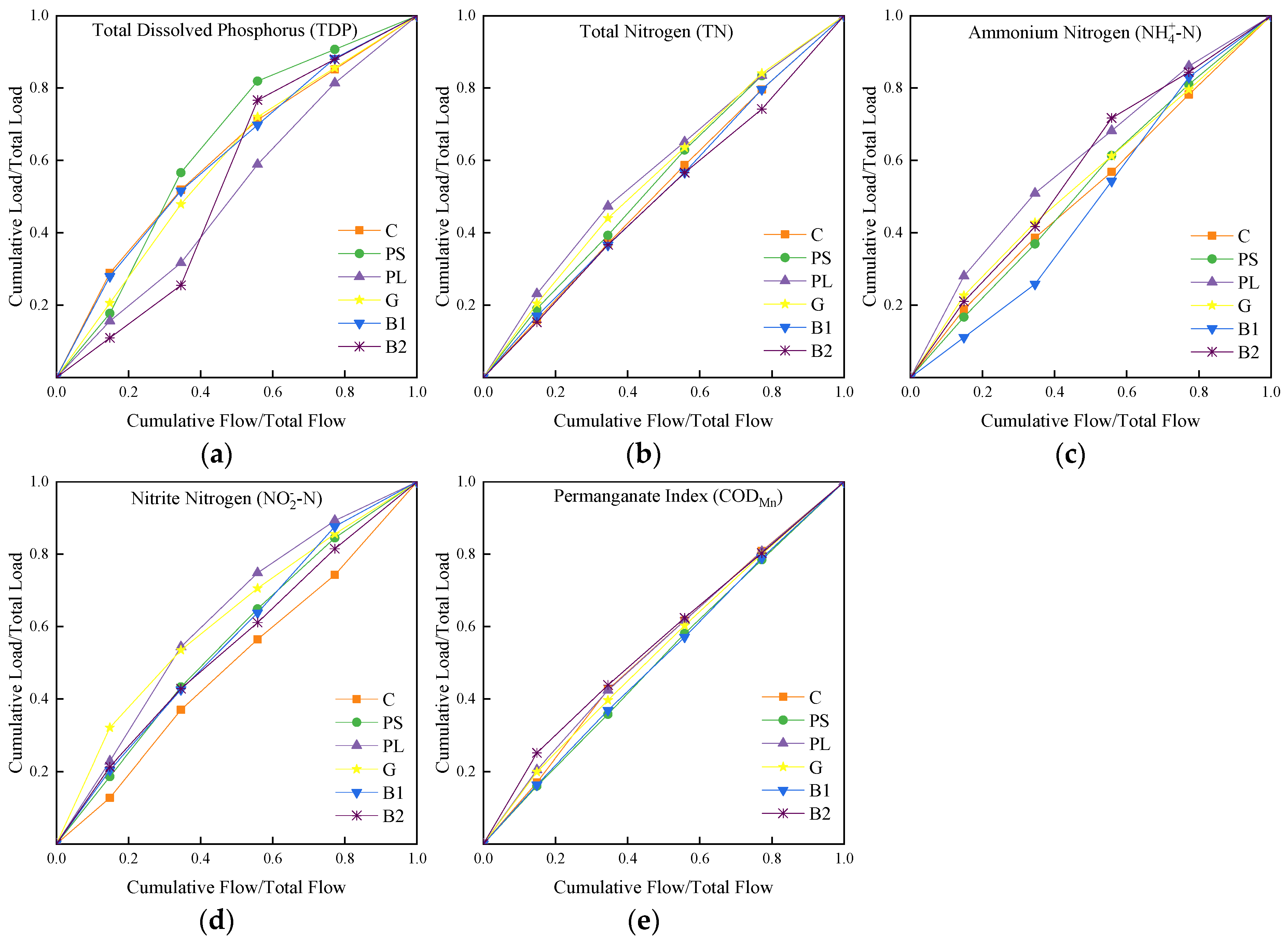

3.3. The First Flush Effect of Runoff Pollutants from Different Livestock and Poultry Breeding Areas

3.4. Determination of the Initial Stormwater Interception Time

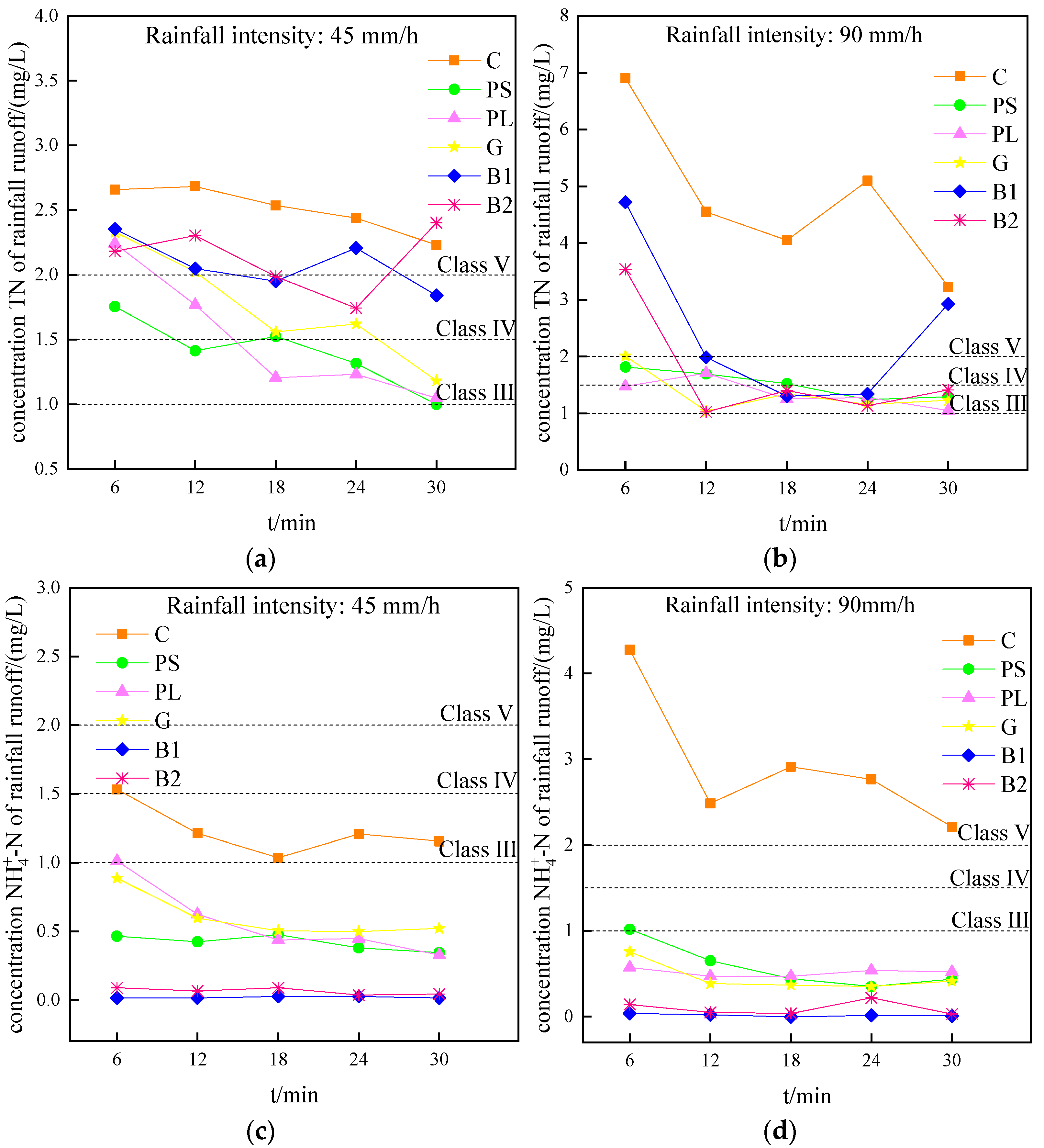

3.4.1. Analysis of TN and N-N Rainfall Interception Time Under Different Rainfall Intensities

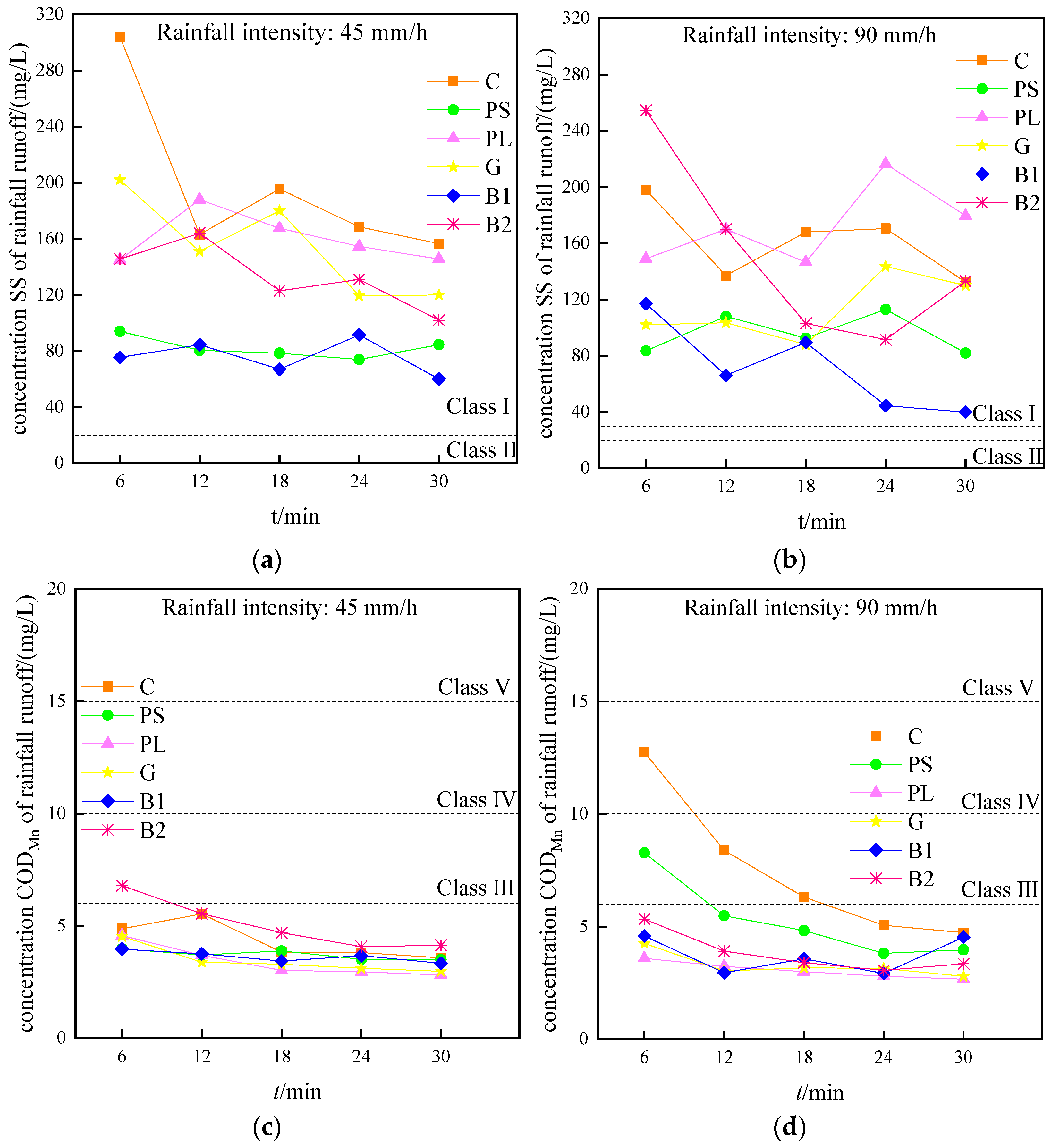

3.4.2. Analysis of SS and CODMn Rainfall Interception Time Under Different Rainfall Intensities

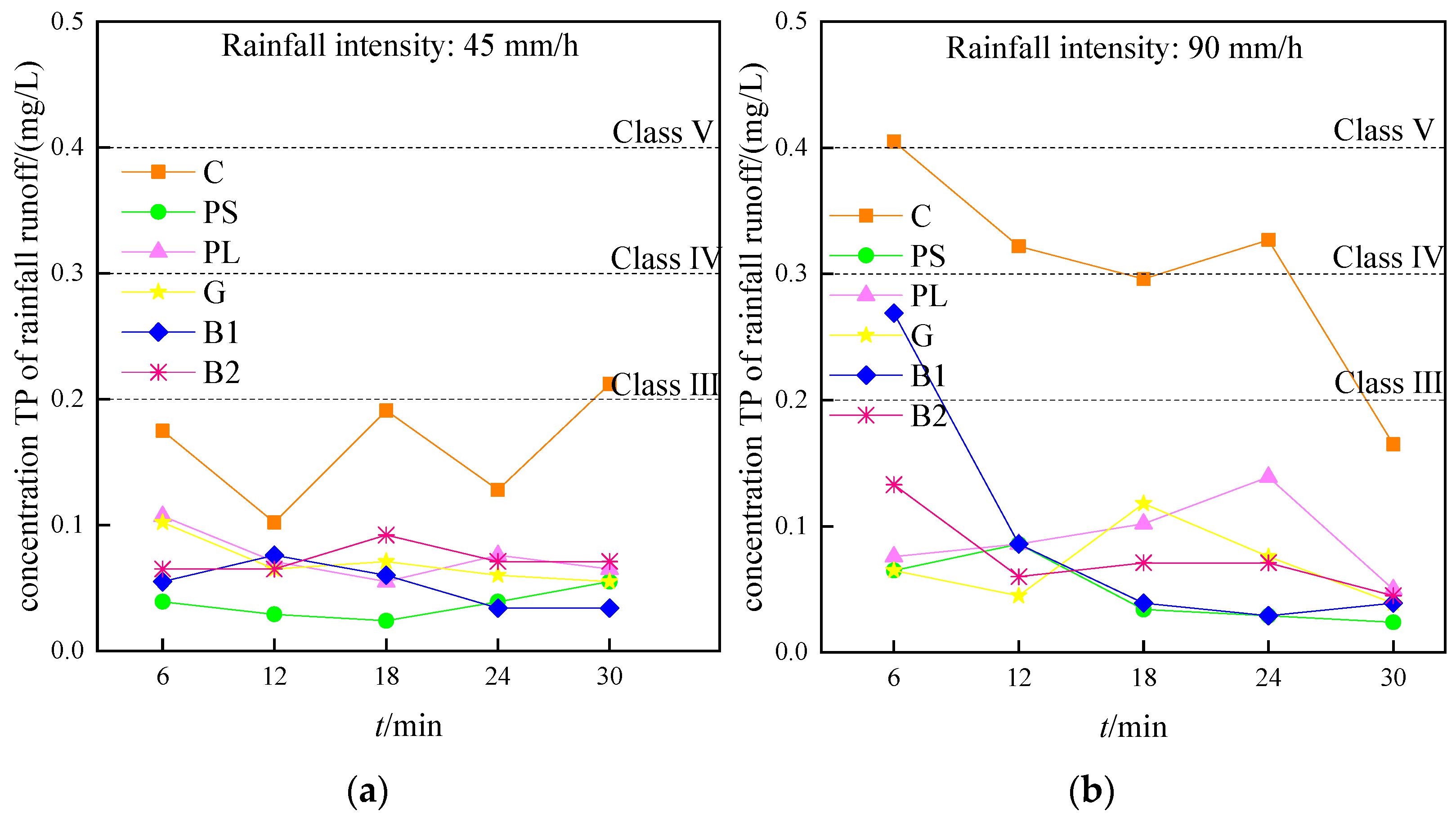

3.4.3. Analysis of TP Rainfall Interception Time Under Different Rainfall Intensities

4. Conclusions

- (a)

- In Chongqing, Distinct, first flush effects were identified for TDP and -N in the road runoff of research areas, as evidenced by their cumulative loads accounting for 85.71% and 83.41% of the total loads, respectively, within the first 24 min of rainfall.

- (b)

- Although the first flush effect was generally more pronounced at 45 mm/h than at 90 mm/h, the dominant pollutants differed: TDP and -N showed stronger effects at 45 mm/h, whereas -N and CODMn were more dominant at 90 mm/h. Furthermore, the first flush of CODMn intensified with increasing rainfall intensity.

- (c)

- At 45 mm/h, the first flush effect was most pronounced in the large-scale piggery and goosery. The total pollutant load was the highest in the hen farm, where the main types of pollutants were TN, -N, TP, and SS. In the small-scale piggery (approximately 800 heads) and goosery, the dominant pollutants were -N and -N, while the large-scale piggery (over 3000 heads) primarily released TDP, -N, and SS.

- (d)

- The pollutant concentrations of rainfall runoff at 90 mm/h were higher than those under 45 mm/h. SSs (suspended solids) exhibited the highest concentration, which continued to exceed the Class II limit of the “Integrated Wastewater Discharge Standard” (GB 8978-1996) [37] even 30 min after rainfall began, followed by TN (total nitrogen). It is recommended that rainfall higher than 45 mm/h for these areas be set between 18 and 24 min after runoff initiation. This measure can effectively intercept 52.68 to 82.63% of pollutants.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Dai, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, B. Simulation Study on the Effect of Non-Point Source Pollution on Water Quality in the Upper Reaches of the Lijiang River. Water 2022, 14, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X. Assessment and analysis of agricultural non-point source pollution loads in China: 1978–2017. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 263, 110400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.X.; Wang, H.W.; Dai, X.H. A review of characteristics and control technologies of urban non-point source pollution. Environ. Eng. 2023, 41, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.F.; Wang, X.K.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Hou, P.Q. Analysis of first flush effect of typical underlying surface runoff in Beijing urban city. Environ. Sci. 2013, 34, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, C.; Hu, Q.; Qi, F.; Sun, D.Z. Review of urban non-point source pollution control technologies and optimization strategies. Environ. Eng. 2023, 41, 11–20+75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. National Water Quality Inventory, Report to Congress Executive Summary; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; p. 497.

- Wang, B.S.; Huang, T.L.; Nie, X.B.; Chai, B.B. Study on rainwater pollutant washoff rate in impervious surface. Chin. J. Environ. Eng. 2010, 4, 1950–1954. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.L.; Liu, M.; Hu, Y.M.; Xu, Y.Y.; Sun, F.Y.; Chen, T. Analysis of first flush in rainfall runoff in Shenyang urban city. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2013, 33, 5952–5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenstrom, M.; Kayhanian, M. First Flush Phenomenon Characterization; Caltrans: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2005.

- Ma, Y. Research on Transportation Simulation of Urban Rainfall-Runoff Non-Point Source Pollution and the First Flush Effects; South China University of Technology: Guangzhou, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Che, W.; Ou, L.; Wang, H.Z.; Li, J.Q. The quality and major influential factors of runoff in Beijing urban area. Tech. Equip. Environ. Pollut. Control. 2002, 3, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Liu, M.; Xu, S.Y.; Hou, L.J.; Wang, H.Y.; Ballo, S. Temporal-spatial distribution and first flush effect of urban stormwater runoff pollution in Shanghai city. Geogr. Res. 2006, 25, 994–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Brezonik, L.P.; Stadelmann, H.T. Analysis and predictive models of stormwater runoff volumes, loads, and pollutant concentrations from watersheds in the Twin Cities metropolitan area, Minnesota, USA. Water Res. 2002, 36, 1743–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnecco, I.; Berretta, C.; Lanza, L.G.; La Barbera, P. Storm water pollution in the urban environment of Genoa, Italy. Atmos. Res. 2004, 77, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Saul, A.J. Specific relationships for the first flush load in combined sewer flows. Water Res. 1996, 30, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.S.; Khan, S.; Li, Y.X.; Kim, L.H.; Ha, S.; Lau, S.L.; Kayhanian, M.; Stenstrom, M.K. First Flush Phenomena for Highways: How It Can Be Meaningfully Defined. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Urban Drainage, Portland, OR, USA, 8–13 October 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Liu, D.; Huang, B.S.; Liu, M.T.; Luo, Z.F. Initial rainwater interception standard for central urban area of megacities based on river in welling capacity. Water Resour. Power 2024, 42, 125–128+196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.J.; Hu, Z.H. Analysis on initial rainwater pollution characteristics and cut-off volume. Ind. Water Wastewater 2023, 54, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Fang, P.N.; Lan, X.C. Comment on rainfall runoff pollution. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2009, 25, 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.A.; Cheng, H.F.; Tao, S. Environmental and human health challenges of industrial livestock and poultry farming in China and their mitigation. Environ. Int. 2017, 107, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Song, K.H.; Hu, T.; Ying, T.Y. Environmental status of livestock and poultry sectors in China under current transformation stage. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622–623, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Z.; Liu, S.; Wu, S.X.; Jin, S.Q.; Reis, S.; Liu, H.B.; Gu, B.J. Rebuilding the linkage between livestock and cropland to mitigate agricultural pollution in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andretta, I.; Hickmann, F.M.; Remus, A.; Franceschi, C.H.; Mariani, A.B.; Orso, C.; Kipper, M.; Létourneau-Montminy, M.P.; Pomar, C. Environmental impacts of pig and poultry prodcution: Insights from a systematic review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 750733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Wang, S.; Reis, S.; Li, Y.; Gu, B. Integrated livestock sector nitrogen pollution abatement measures could generate net benefits for human and ecosystem health in China. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xie, Z.J.; Li, C.H.; Ye, C.; Miao, K.X.; Wei, W.W.; Zheng, Y. Non-point source pollutions in typical river basins in hilly and mountainous areas and plain river network area in China. Environ. Eng. 2024, 42, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ye, C.; Miao, K.X.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.H.; Xu, Y.B.; Shi, J.L. Analysis of the First Flush Effect in Rainfall Runoff Pollution from Urban and Non-Urban Areas. Res. Environ. Sci. 2025, 38, 1783–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.G.; Zhu, X. Preliminary analysis of interception measures on initial rainwater runoff. South-North Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 11, 215–217. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.L. Initial analysis on preliminary rainwater quality and abandon water. Shanxi Archit. 2011, 37, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, C.H.; Ye, C.; Miao, J.X.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J.W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Parameter calibration for the effect of simulated rainfall on the non-point source pollution. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2024, 14, 1686–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ 636—2012; Water Quality—Determination of Total Nitrogen—Alkaline Potassium Persulfate Digestion UV Spectrophotometric Method. Ministry of Ecological Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB 11893—1989; Water Quality—Determination of Total Phosphorus-Ammonium Molybdate Spectrophotometric Method. National Environmental Protection Agency: Beijing, China, 1989.

- GB 11901—1989; Water Quality—Determination of Suspended Substance-Gravimetric Method. National Environmental Protection Agency: Beijing, China, 1989.

- GB 7493—1987; Water Quality—Determination of Nitrogen (Nitrite)-Spectrophotometric Method. National Environmental Protection Agency: Beijing, China, 1987.

- HJ 535—2009; Water Quality—Determination of Ammonia Nitrogen—Nessler’s Reagent Spectrophotometry. Ministry of Ecological Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- GB/T 15456—2019; Determination of the Chemical Oxygen Demand in Industrial Circulating Cooling Water—Permanganate Index Method. State Administration of Market Supervision and Administration. China National Standardization Management Committee: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Geiger, W. Flushing effects in combined sewer systems. Urban Storm Drain. 1987, 4, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- GB 8978—1996; Integrated Wastewater Discharge Standard. National Environmental Protection Agency: Beijing, China, 1996.

- GB 3838—2002; Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water. State Environmental Protection Administration, the State Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Li, Q.; Zhang, N.; Luo, Y.J.; Wang, X.; Jing, Y.C. The first flush effect of urban rainfall runoff based on MFF30 method. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2019, 36, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.D.; Li, H.X.; Liu, Y.; Liang, S.; Wang, L.F. First flush and initial split-flow time in the initial rainfall: A case study of urban roads in Xuzhou city. Ecol. Environ. Monit. Three Gorges 2024, 9, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.T.; Liu, R.L.; Shan, H. Nutrient contents in main animal manures in China. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2009, 28, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

| Point Number | Geographical Location | Average Slope/(°) | Rainfall Intensity/(mm/h) | Early Sunny Days Time/d | Duration of Rainfall/min | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 29°09′01″ N, 105°53′36″ E | 5.87 | 45 | 6 | 30 | highway adjacent to hen farm (1300 birds) |

| 5.28 | 90 | |||||

| PS | 29°08′57″ N, 105°50′53″ E | 2.78 | 45 | 6 | 30 | highway adjacent to small-scale piggery (800 heads) |

| 2.58 | 90 | |||||

| PL | 29°09′45″ N, 105°51′49″ E | 5.14 | 45 | 6 | 30 | highway adjacent to large-scale piggery (800 heads) |

| 4.44 | 90 | |||||

| G | 29°07′59″ N, 105°52′59″ E | 4.52 | 45 | 6 | 30 | highway adjacent to goosery (500 birds) |

| 4.25 | 90 | |||||

| B1 | 29°16′55″ N, 105°55′21″ E | 3.19 | 45 | 9 | 30 | highway adjacent to gas station park |

| 4.91 | 90 | |||||

| B2 | 29°08′06″ N, 105°57′03″ E | 4.23 | 45 | 9 | 30 | highway adjacent to Shisun Mountain park |

| 6.90 | 90 |

| Point Number | Total Pollution Load/[mg/(30 min)] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | TDP | TN | -N | -N | SS | CODMn | |

| C | 13.796 | 1.719 | 211.641 | 102.580 | 2.755 | 16,178.075 | 362.277 |

| PS | 3.186 | 0.567 | 116.527 | 35.151 | 2.350 | 6927.850 | 314.242 |

| PL | 6.178 | 1.914 | 122.275 | 45.597 | 2.523 | 13,618.192 | 282.378 |

| G | 5.820 | 1.769 | 143.713 | 49.455 | 4.000 | 12,814.208 | 287.795 |

| B1 | 4.332 | 1.304 | 174.854 | 1.630 | 3.076 | 6398.533 | 306.580 |

| B2 | 6.229 | 2.122 | 180.067 | 5.316 | 2.222 | 11,152.108 | 565.364 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Ye, C. Analysis of the First Flush Effect of Rainfall Runoff Pollution in Typical Livestock and Poultry Breeding Areas. Water 2025, 17, 3487. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243487

Wang J, Wang Y, Li C, Ye C. Analysis of the First Flush Effect of Rainfall Runoff Pollution in Typical Livestock and Poultry Breeding Areas. Water. 2025; 17(24):3487. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243487

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jie, Yan Wang, Chunhua Li, and Chun Ye. 2025. "Analysis of the First Flush Effect of Rainfall Runoff Pollution in Typical Livestock and Poultry Breeding Areas" Water 17, no. 24: 3487. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243487

APA StyleWang, J., Wang, Y., Li, C., & Ye, C. (2025). Analysis of the First Flush Effect of Rainfall Runoff Pollution in Typical Livestock and Poultry Breeding Areas. Water, 17(24), 3487. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243487