Effects of Forest Thinning on Water Yield and Runoff Components in Headwater Catchments of Japanese Cypress Plantation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Catchment Treatment

2.2. Hydrological Measurements

2.3. Annual Water Yield Estimation

2.4. Flow Duration Curve

2.5. Storm Event Hydrographs and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Rainfall–Runoff Analysis

3.2. Water Yield Response to Thinning

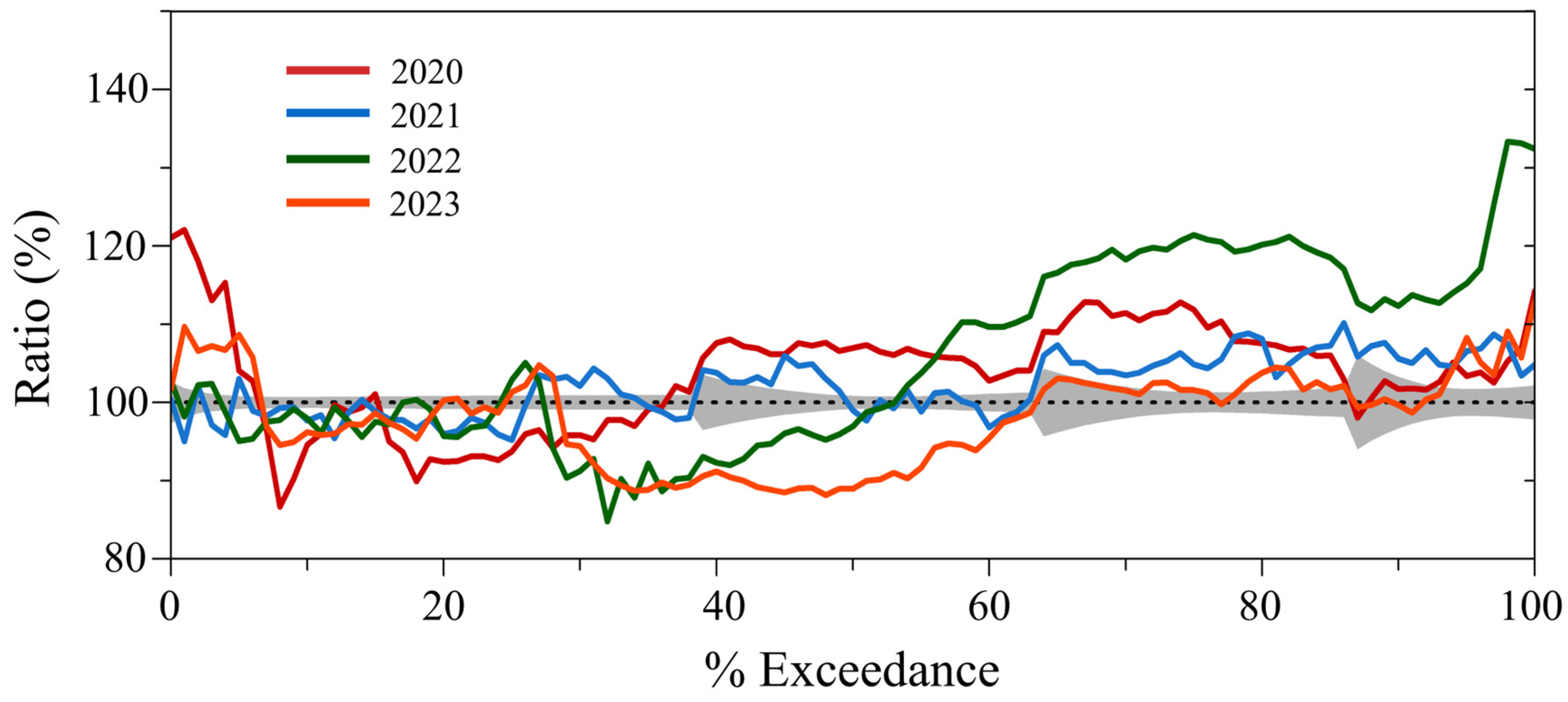

3.3. Flow Duration Curves Based on Observed/Estimated Ratios

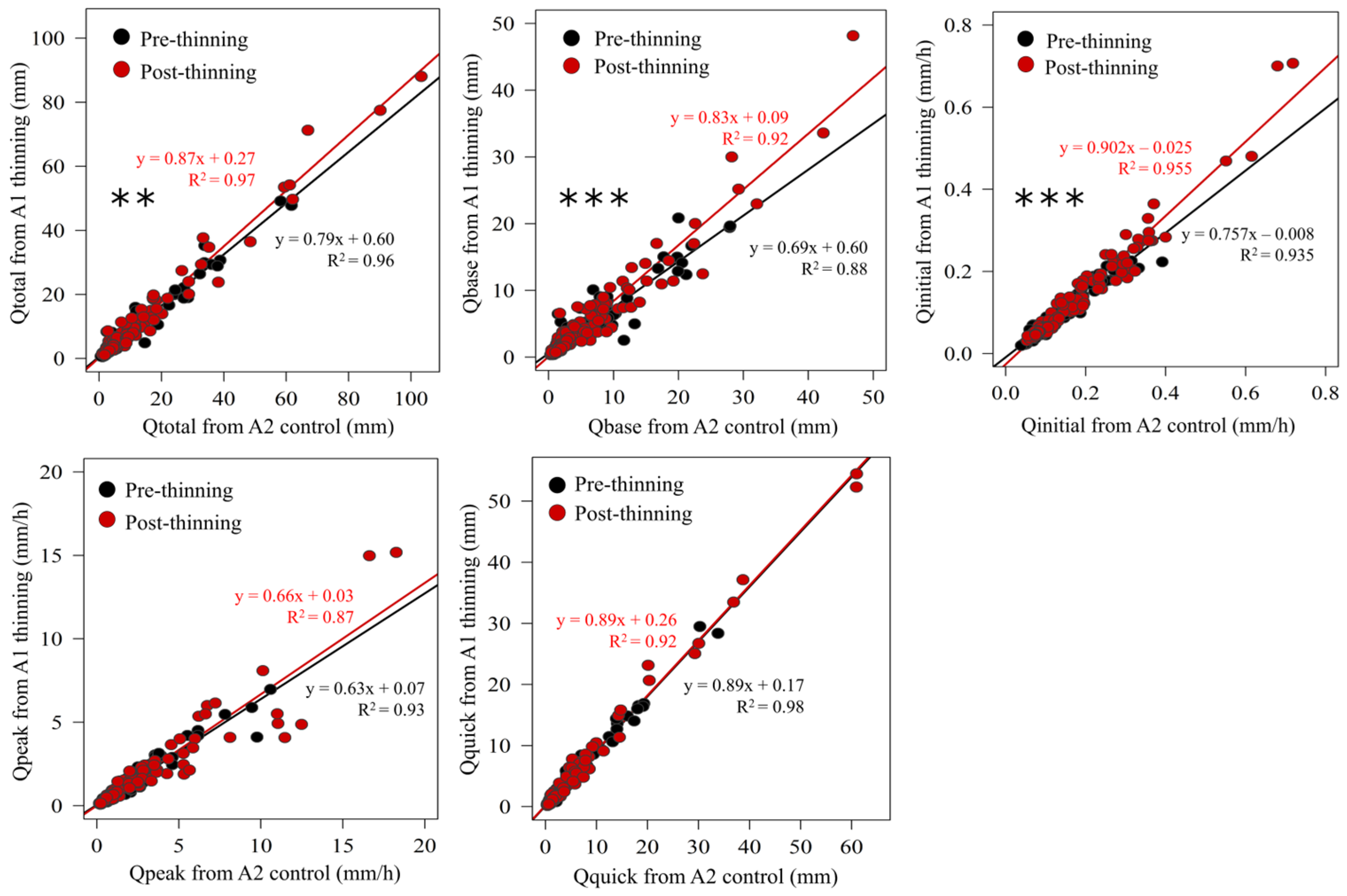

3.4. Storm Event Scale Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Runoff Response to Thinning

4.2. Flow Duration Curve and Event-Scale Runoff Dynamics

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Direction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, T.M. Forest Runoff Processes. In Forest Hydrology: Processes, Management and Assessment; Amatya, D.M., Williams, T.M., Bren, L., de Jong, C., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2016; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, H.; Jia, G.; Zhao, Y.; Tu, Z.; Deng, W.; Jia, J.; Chen, J. Effects of forest structure on hydrological processes in China. J. Hydrol. 2018, 561, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pypker, T.G.; Levia, D.F.; Staelens, J.; Van Stan, J.T. Canopy Structure in Relation to Hydrological and Biogeochemical Fluxes. In Forest Hydrology and Biogeochemistry; Levia, D., Carlyle-Moses, D., Tanaka, T., Eds.; Ecological Studies; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 216, pp. 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Jons, J.; Hou, Y.; Liu, S.; Asbjornsen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Shah, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; et al. Local considerations are the key to managing global forests for water. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Hu, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, J.; Maeda, E.E.; Ju, W.; Liu, L.; Guo, Q.; et al. Enhancing ecosystem productivity and stability with increasing canopy structural complexity in global forests. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadl1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnesoeur, V.; Locatelli, B.; Guariguata, M.R.; Ochoa-Tocachi, B.F.; Vanacker, V.; Mao, Z.; Stokes, A.; Mathez-Stiefel, S.L. Impacts of forests and forestation on hydrological services in the Andes: A systematic review. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 433, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, I.C.; Death, R.G. The science of connected ecosystems: What is the role of catchment-scale connectivity for healthy river ecology? Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1413–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, V.K.; Tailor, R.; Shanbhag, R.R.; Murthy, N.; Kushwaha, P.K.; Ranjan, M. Status and Trend Analysis of the Production, Export and Import of Wood and Wood Products in the G20 Countries from 2004 to 2021. J. For. Sci. 2025, 71, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.D. Positive Environmental Impact of Productive Forest Expansion on Mitigating Climate Change and Reducing Natural and Semi-Natural Forest Loss. Scott. For. 2022, 76, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, E.J.; Styles, D.; Healey, J.R. Temperate Forests Can Deliver Future Wood Demand and Climate-Change Mitigation Dependent on Afforestation and Circularity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.G.; Salemi, L.F.; de Paula Lima, W.; de Barros Ferraz, S.F. Hydrological Effects of Forest Plantation Clear-Cut on Water Availability: Consequences for Downstream Water Users. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2018, 19, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, P.; Versfeld, D. Managing the Hydrological Impacts of South African Plantation Forests: An Overview. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 251, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Xiang, W.; Ouyang, S.; Hu, Y.; Peng, C. Balancing Water Yield and Water Use Efficiency between Planted and Natural Forests: A Global Analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Forest Agency. Annual Report on Forest and Forestry in Japan—Fiscal Year 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/e/data/publish/attach/pdf/index-193.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Fujiwara, M. Silviculture in Japan. In Forestry and the Forest Industry in Japan; Iwai, Y., Ed.; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2002; pp. 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Paletto, A.; Sereno, C.; Furuido, H. Historical Evolution of Forest Management in Europe and in Japan. Bull. Tokyo Univ. For. 2008, 119, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, H.; Shinohara, Y.; Kume, T.; Otsuki, K. Relationship between Annual Rainfall and Interception Ratio for Forest across Japan. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 256, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, H. Modelling Evapotranspiration Changes with Managing Japanese Cedar and Cypress Plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 475, 118395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takafumi, H.; Hiura, T. Effects of Disturbance History and Environmental Factors on the Diversity and Productivity of Understory Vegetation in a Cool-Temperate Forest in Japan. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanko, K.; Hotta, N.; Suzuki, M. Assessing Raindrop Impact Energy at the Forest Floor in a Mature Japanese Cypress Plantation Using Continuous Raindrop-Sizing Instruments. J. For. Res. 2004, 9, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, T.; Sidle, R.C.; Ueno, M.; Miyata, S.; Kosugi, K.I. Characteristics of Overland Flow Generation on Steep Forested Hillslopes of Central Japan. J. Hydrol. 2008, 361, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, T. Control of Individual Tree Growth and Quality in Relation to Stand Density. In Ecological and Silvicultural Strategies for Sustainable Forest Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 139–162. [Google Scholar]

- del Campo, A.D.; Otsuki, K.; Serengil, Y.; Blanco, J.A.; Yousefpou, R.; Wei, X. A Global Synthesis on the Effects of Thinning on Hydrological Processes: Implications for Forest Management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 519, 120324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, T.; Tsuboyama, Y.; Nobuhiro, T. Effects of Thinning on Canopy Interception Loss, Evapotranspiration, and Runoff in a Small Headwater Chamaecyparis obtusa Catchment in Hitachi Ohta Experimental Watershed in Japan. Bull. For. For. Prod. Res. Inst. 2018, 17, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuraji, K.; Gomyo, M.; Nainar, A. Thinning of cypress forest increases subsurface runoff but reduces peak storm-runoff: A lysimeter observation. Hydrol. Res. Lett. 2019, 13, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, B.X.; Gomi, T.; Miyata, S.; Sidle, R.C.; Kosugi, K.; Onda, Y. Runoff responses to forest thinning at plot and catchment scales in a headwater catchment draining Japanese cypress forest. J. Hydrol. 2012, 444–445, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Choi, H.T.; Lim, H. Effects of Forest Thinning on the Long-Term Runoff Changes of Coniferous Forest Plantation. Water 2019, 11, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junsuk, K.; Kubota, T.; Shiraki, K. Long-term effects of thinning on runoff changes from coniferous forest plantations in headwater catchments. Hydrol. Res. Lett. 2025, 19, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, G.; Mitra, B.; Noormets, A.; Gavazzi, M.J.; Domec, J.C.; McNulty, S.G. Drought and thinning have limited impacts on evapotranspiration in a managed pine plantation on the southeastern United States coastal plain. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 262, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, J.M.; Hewlett, J.D. A review of catchment experiments to determine the effect of vegetation changes on water yield and evapotranspiration. J. Hydrol. 1982, 55, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.E.; Zhang, L.; McMahon, T.A.; Western, A.W.; Vertessy, R.A. A review of paired catchment studies or determining changes in water yield resulting from alterations in vegetation. J. Hydrol. 2005, 310, 28–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeking, S.A.; Tarboton, D.G. Variable Streamflow Response to Forest Disturbance in the Western US: A Large-Sample Hydrology Approach. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR031575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, K. Comparison of Discharge Duration Curves from Two Adjacent Forested Catchments—Effect of Forest Age and Dominant Tree Species. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2010, 2, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tanaka, T. Vulnerability of the Paired Watershed Method. Suiri Kagaku (Water Sci.) 2012, 56, 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Meteorological Agency. Climate of Tokai District. 2020. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/cpd/longfcst/en/tourist/file/Tokai.html (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Tobe, H.; Chigira, M.; Doshida, S. Comparison of Landslide Densities between Rock types in Weathered Granitoid in Obara Village, Aichi Prefecture. J. Jpn. Soc. Eng. Geol. 2007, 48, 66–79, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources, International Soil Classification system for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; World Soil Resources Reports; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015; Volume 106, 192p. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T.; Tanaka, N.; Nainar, A.; Kuraji, K.; Gomyo, M.; Suzuki, H. Soil erosion and overland flow in Japanese cypress plantations: Spatio-temporal variations and a sampling strategy. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2020, 65, 2322–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckenwalder, J.E. Conifers of the World: The Complete Reference; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2009; pp. 204–205. [Google Scholar]

- Karizumi, N. The Latest Illustration of Tree Roots; Seibundo Shinkosha: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, T.C. Watershed Management Field Manual: Watershed Survey and Planning; FAO Conservation Guide 13/6; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, M.; Ohte, N.; Tani, M. Effects of hillslope topography on runoff response in a small catchment in the Fudoji Experimental Watershed, central Japan. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 1874–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota City. Toyota City Forest Conservation Guidelines; Toyota City Industry Department, Agriculture and Forestry Promotion Office, Forestry Division: Toyota, Japan, 2019; Available online: https://www.city.toyota.aichi.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/035/013/r0301_honpen.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025). (In Japanese)

- Viessman, W., Jr.; Lewis, G.L. Introduction to Hydrology, 4th ed.; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, R.M.; Fennessey, N.M. Flow duration curves II: A review of applications in water resources planning. Water Resour. Bull. 1995, 31, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.E.; Western, A.W.; McMahon, T.A.; Zhang, L. Impact of forest cover changes on annual streamflow and flow duration curves. J. Hydrol. 2013, 483, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Kikuya, A.; Morisawa, M. Effects of changes in forest conditions, especially cutting on runoff (1): Effects on water-yearly, plentiful, ordinary, low and scanty runoffs. Bull. Gov. For. Exp. Stn. 1963, 156, 1–84, (In Japanese, with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett, J.D.; Hibbert, A.R. Factors affecting the response of small watersheds to precipitation in humid areas. In Forest Hydrology; Sopper, W.E., Lull, H.W., Eds.; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967; pp. 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainar, A.; Tanaka, N.; Sato, T.; Mizuuchi, Y.; Kuraji, K. A comparison of hydrological characteristics between a cypress and mixed-broadleaf forest: Implication on water resource and floods. J. Hydrol. 2021, 595, 125679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free Software Foundation. GNU Fortran Compiler, version 10.3.0; Free Software Foundation: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://gcc.gnu.org/fortran/ (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- ISO/IEC 1539-1:1997; Information Technology—Programming Languages—Fortran—Part 1: Base Language. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Iida, S.; Noguchi, S.; Levia, D.F.; Araki, M.; Nitta, K.; Wada, S.; Narita, Y.; Tamura, H.; Abe, T.; Kaneko, T. Effects of forest thinning on sap flow dynamics and transpiration in a Japanese cedar forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahnak, M.; Tanaka, N.; Sato, T.; Nainar, A.; Gomyo, M.; Kuraji, K.; Suzaki, T.; Suzuki, H.; Nakane, Y. Enhancing Overland Flow Infiltration through Sustainable Well-Managed Thinning: Contour-Aligned Felled Log Placement in a Chamaecyparis obtusa Plantation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J.M., III; Skaggs, R.W.; Chescheir, G.M. Hydrologic and water quality effects of thinning loblolly pine. Trans. ASABE 2006, 49, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.F.M.A.; Hiura, H.; Shino, K.; Takase, K. Effects of forest thinning on direct runoff and peak runoff properties in a small mountainous watershed in Kochi Prefecture, Japan. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2005, 8, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahnak, M.; Sato, T.; Tanak, N.; Nainar, A.; Mohd Ghaus, I.; Kuraji, K. Impact of Thinning and Contour-Felled Logs on Overland Flow, Soil Erosion, and Litter Erosion in a Monoculture Japanese Cypress Forest Plantation. Water 2024, 16, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momiyama, H.; Kumagai, T.; Egusa, T. Model analysis of forest thinning impacts on the water resources during hydrological drought periods. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 499, 119593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Precipitation (mm) | A2 Control Catchment | A1 Thinning Catchment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Runoff (mm) | Runoff Coefficient (%) | Runoff (mm) | Runoff Coefficient (%) | Estimated Runoff (mm) | Water Yields (mm) | ||

| Pre-thinning | |||||||

| March–December 2016 | 1975.0 | 1112.4 | 56.3 | 823.4 | 41.7 | 810.6 | 12.8 |

| 2017 | 2071.5 | 1289.5 | 62.3 | 922.7 | 44.5 | 934.7 | −12.0 |

| 2018 | 2118.5 | 1375.9 | 64.9 | 1002.8 | 47.3 | 995.3 | 7.6 |

| 2019 | 1956.0 | 1097.6 | 56.1 | 791.8 | 40.5 | 800.2 | −8.4 |

| Mean | 2030.3 | 1218.9 | 59.9 | 885.2 | 43.5 | 885.2 | 0.0 |

| Thinning | |||||||

| 2020 | 2299.0 | 1610.3 | 70.0 | 1268.2 | 55.2 | 1159.5 | 108.7 |

| Post-thinning | |||||||

| 2021 | 2587.0 | 1872.7 | 72.4 | 1443.2 | 55.8 | 1343.5 | 99.7 |

| 2022 | 2118.0 | 1466.1 | 69.2 | 1102.2 | 52.0 | 1058.5 | 43.7 |

| 2023 | 2111.0 | 1308.7 | 62.0 | 948.5 | 44.9 | 948.1 | 0.4 |

| Mean | 2272.0 | 1549.1 | 67.9 | 1164.6 | 50.9 | 1116.7 | 47.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohd Ghaus, I.; Tanaka, N.; Sato, T.; Farahnak, M.; Otani, Y.; Nainar, A.; Gomyo, M.; Kuraji, K. Effects of Forest Thinning on Water Yield and Runoff Components in Headwater Catchments of Japanese Cypress Plantation. Water 2025, 17, 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243461

Mohd Ghaus I, Tanaka N, Sato T, Farahnak M, Otani Y, Nainar A, Gomyo M, Kuraji K. Effects of Forest Thinning on Water Yield and Runoff Components in Headwater Catchments of Japanese Cypress Plantation. Water. 2025; 17(24):3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243461

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohd Ghaus, Ibtisam, Nobuaki Tanaka, Takanori Sato, Moein Farahnak, Yuya Otani, Anand Nainar, Mie Gomyo, and Koichiro Kuraji. 2025. "Effects of Forest Thinning on Water Yield and Runoff Components in Headwater Catchments of Japanese Cypress Plantation" Water 17, no. 24: 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243461

APA StyleMohd Ghaus, I., Tanaka, N., Sato, T., Farahnak, M., Otani, Y., Nainar, A., Gomyo, M., & Kuraji, K. (2025). Effects of Forest Thinning on Water Yield and Runoff Components in Headwater Catchments of Japanese Cypress Plantation. Water, 17(24), 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243461