Effects of Priestia megaterium A20 on the Aggregation Behavior and Growth Characteristics of Microcystis aeruginosa FACHB-912

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algal Culture Conditions

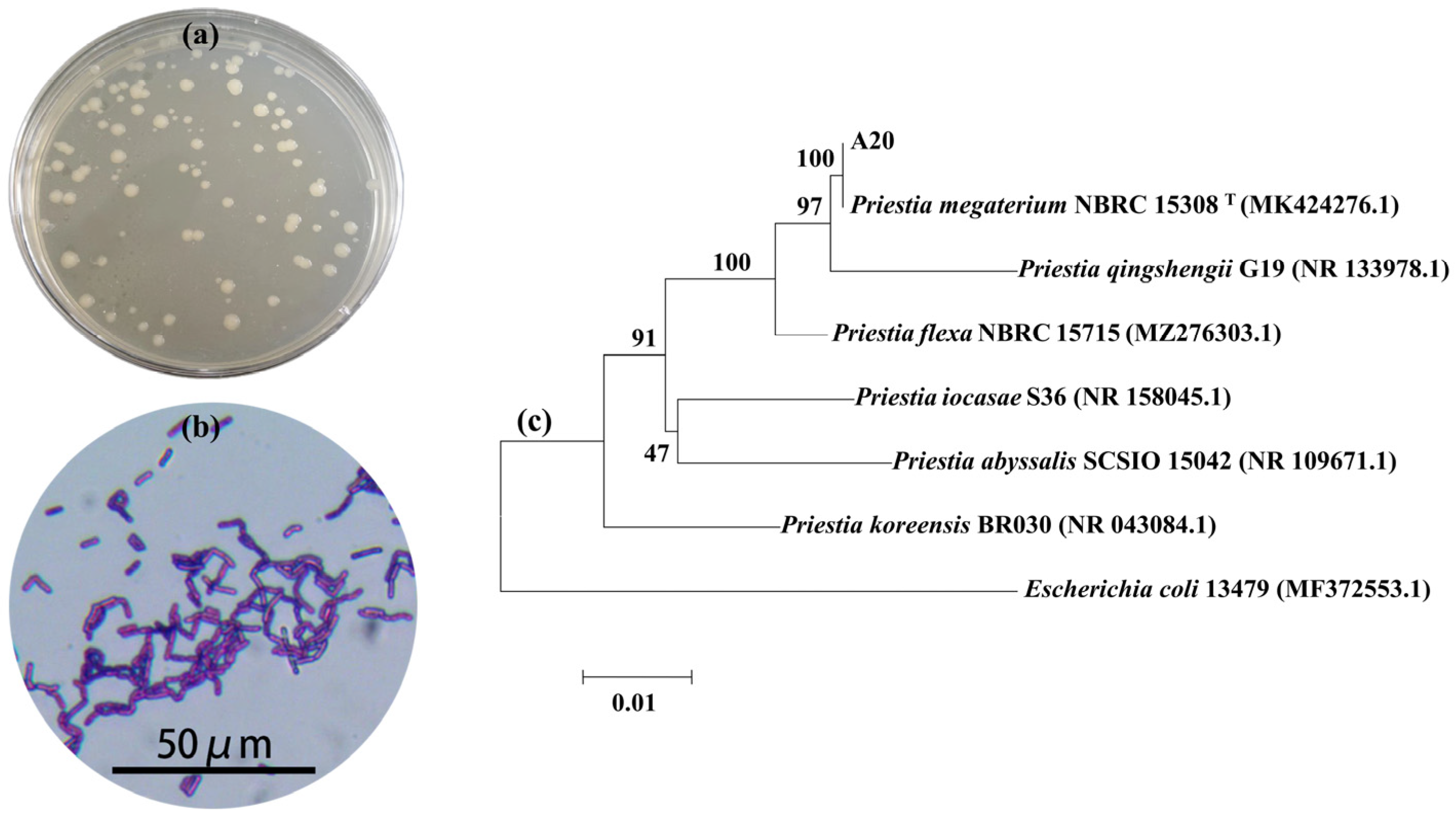

2.2. Screening Symbiotic Bacteria

2.2.1. Isolation and Purification of Bacteria Coexisting with Microcystis aeruginosa

2.2.2. Co-Culture and Screening of Bacteria

2.2.3. Molecular Biological Identification

2.3. Detection Indicators

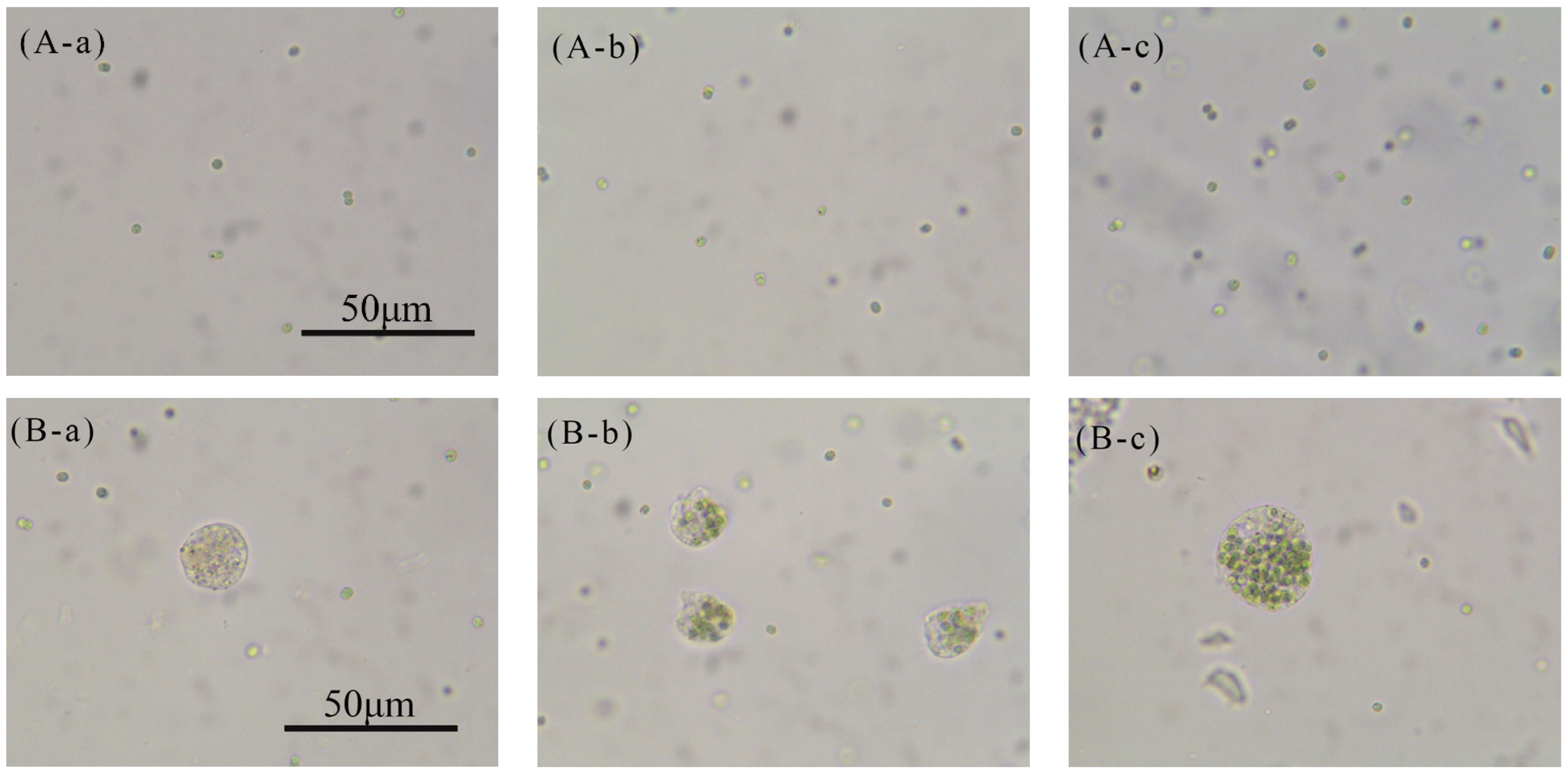

2.3.1. Cell Morphology

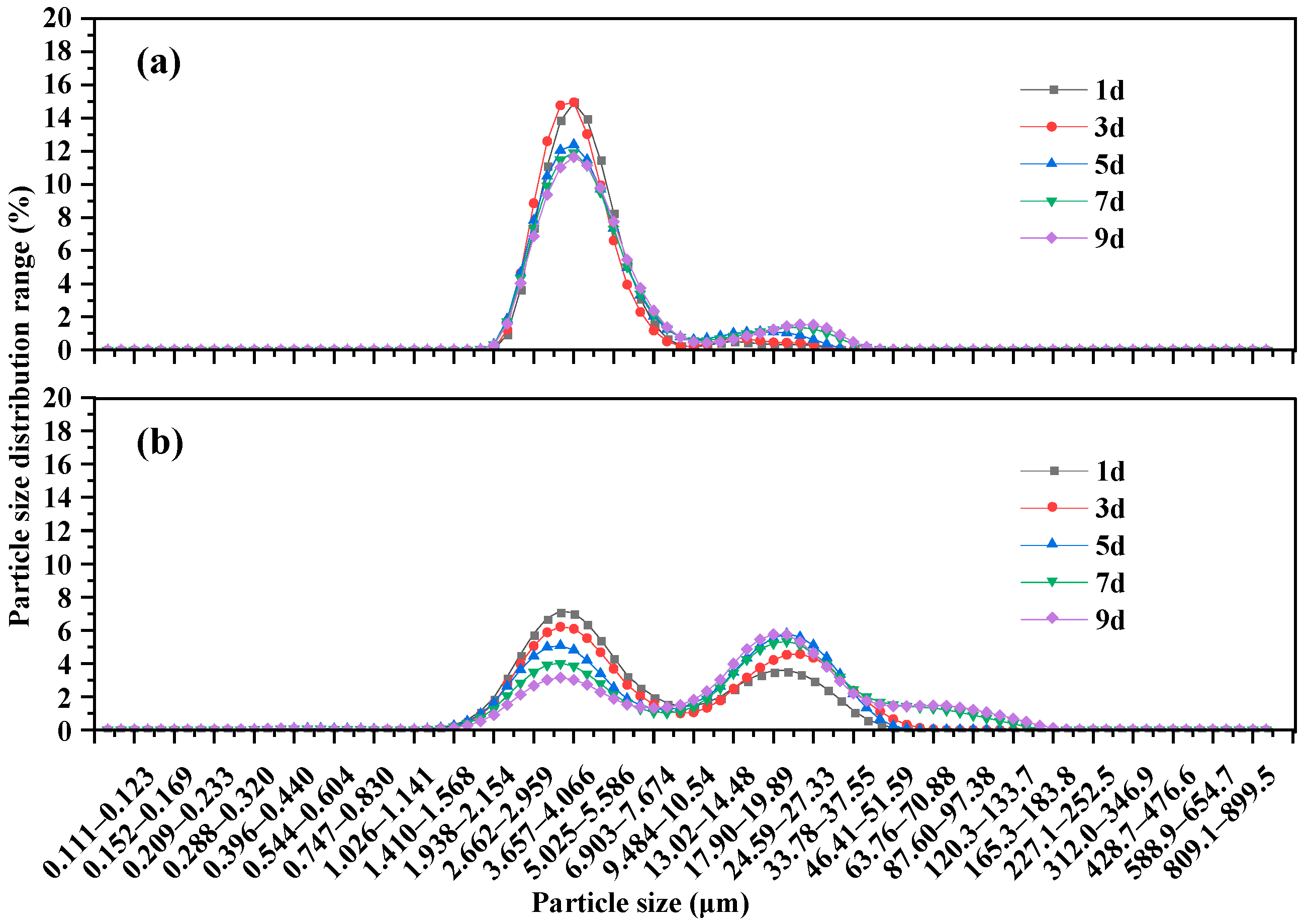

2.3.2. Particle Size Distribution

2.3.3. Chlorophyll-a

2.3.4. Photochemical Efficiency (Fv/Fm)

2.3.5. Dissolved Organic Carbon

2.3.6. UV254

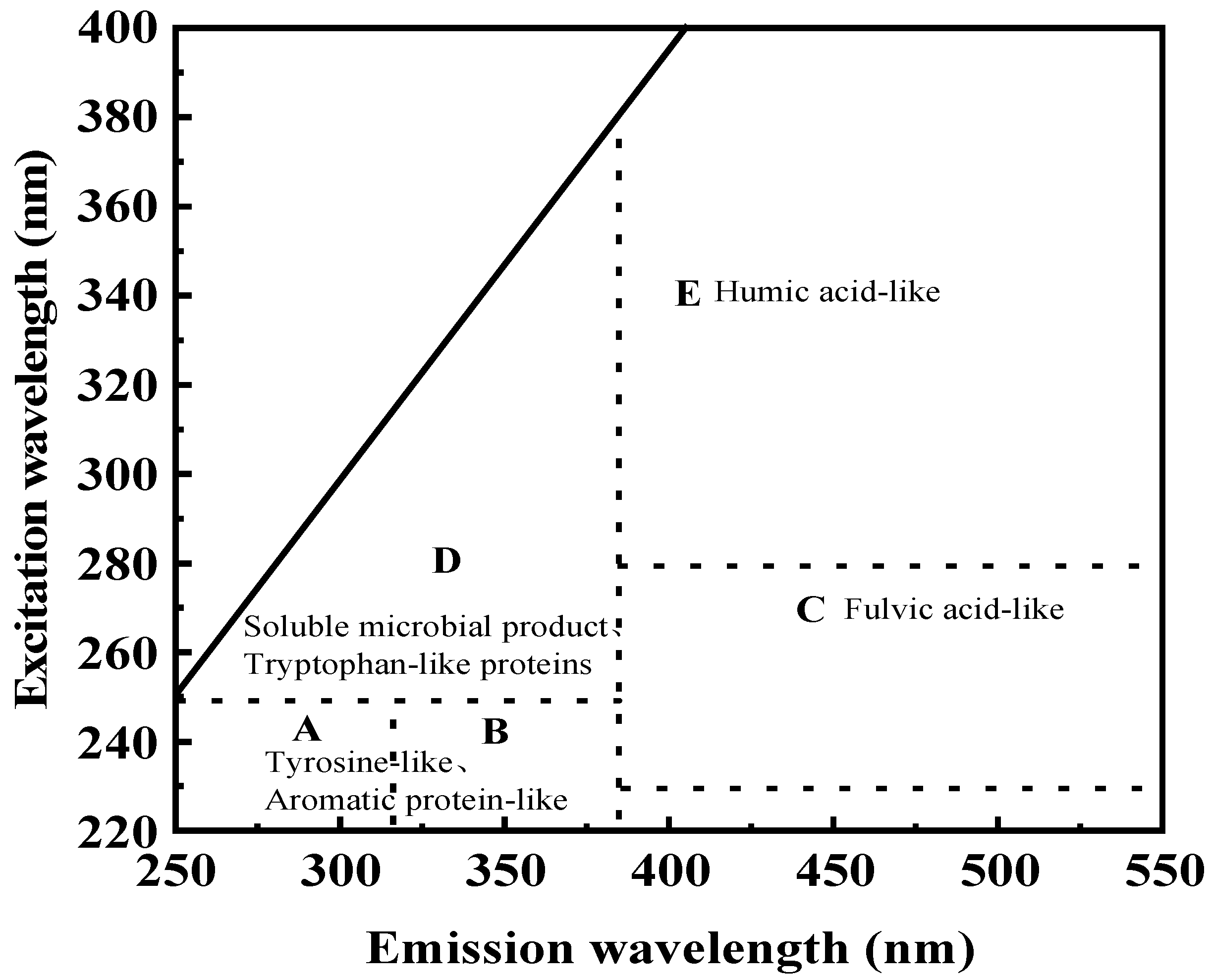

2.3.7. Fluorescence Spectroscopy Analysis of Component Structural Characteristics

2.4. Data Analysis and Visualization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Bacterial Strain Causing Aggregation Behavior of Microcystis aeruginosa

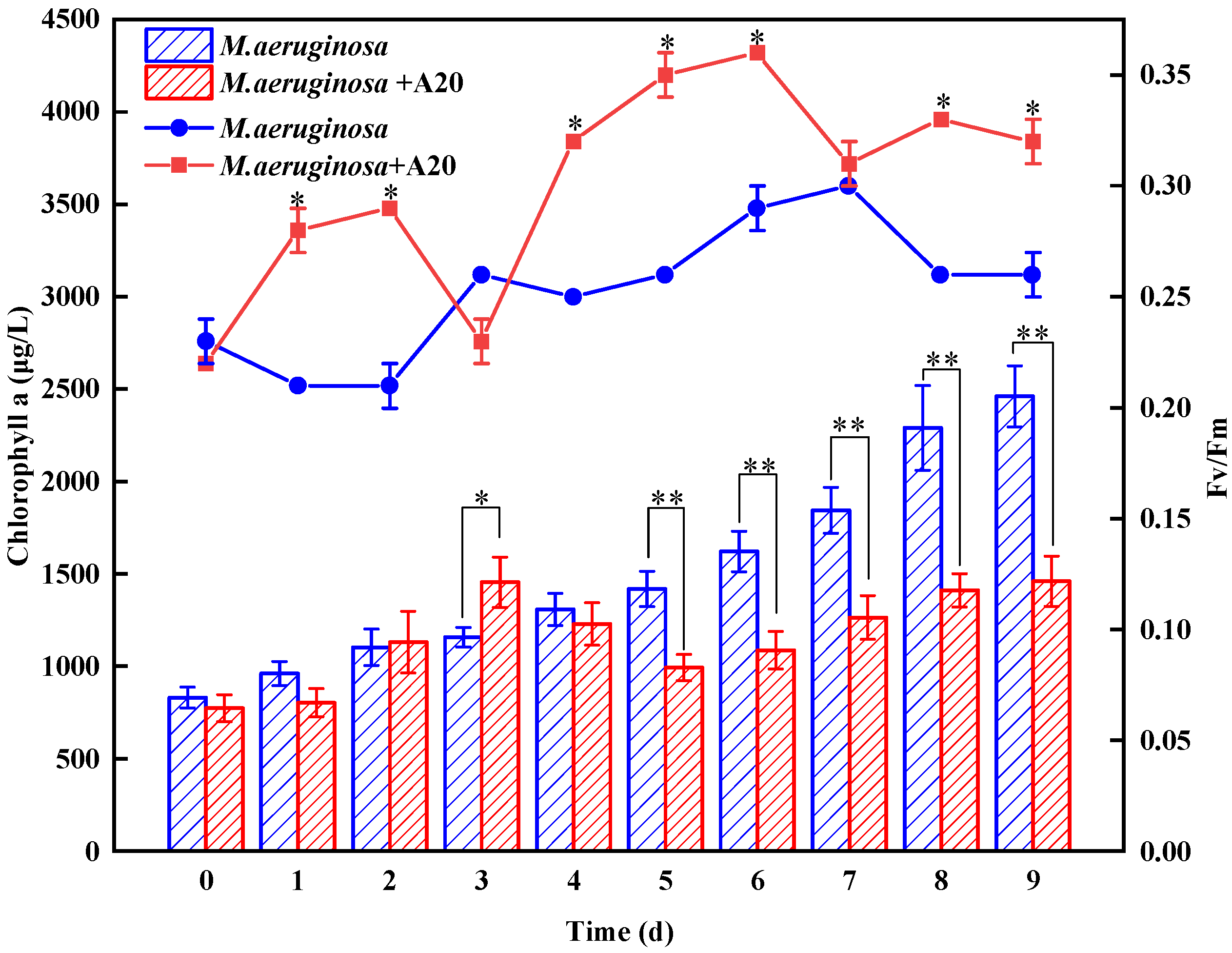

3.2. Effect of A20 on the Growth Trends of Microcystis aeruginosa

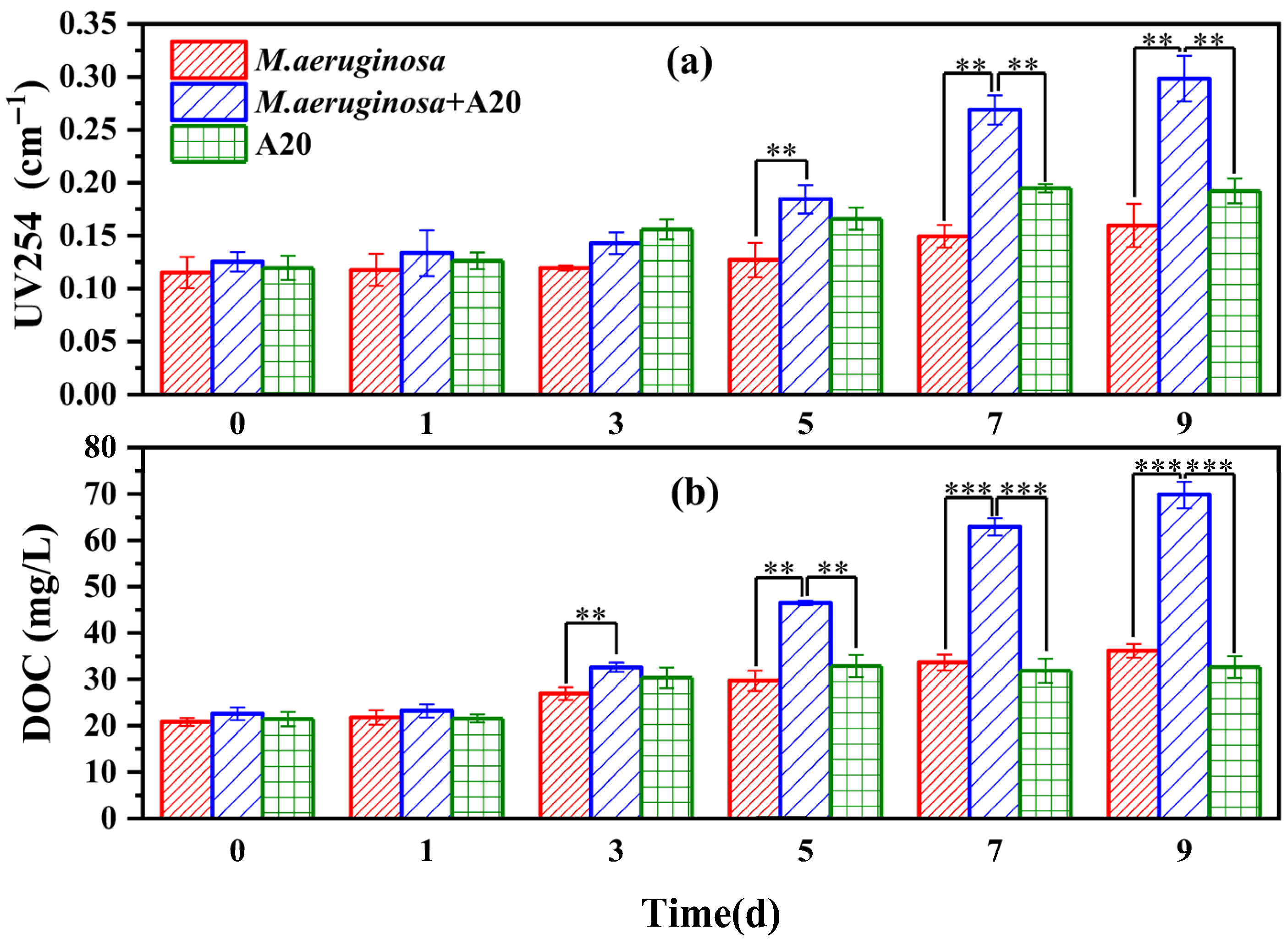

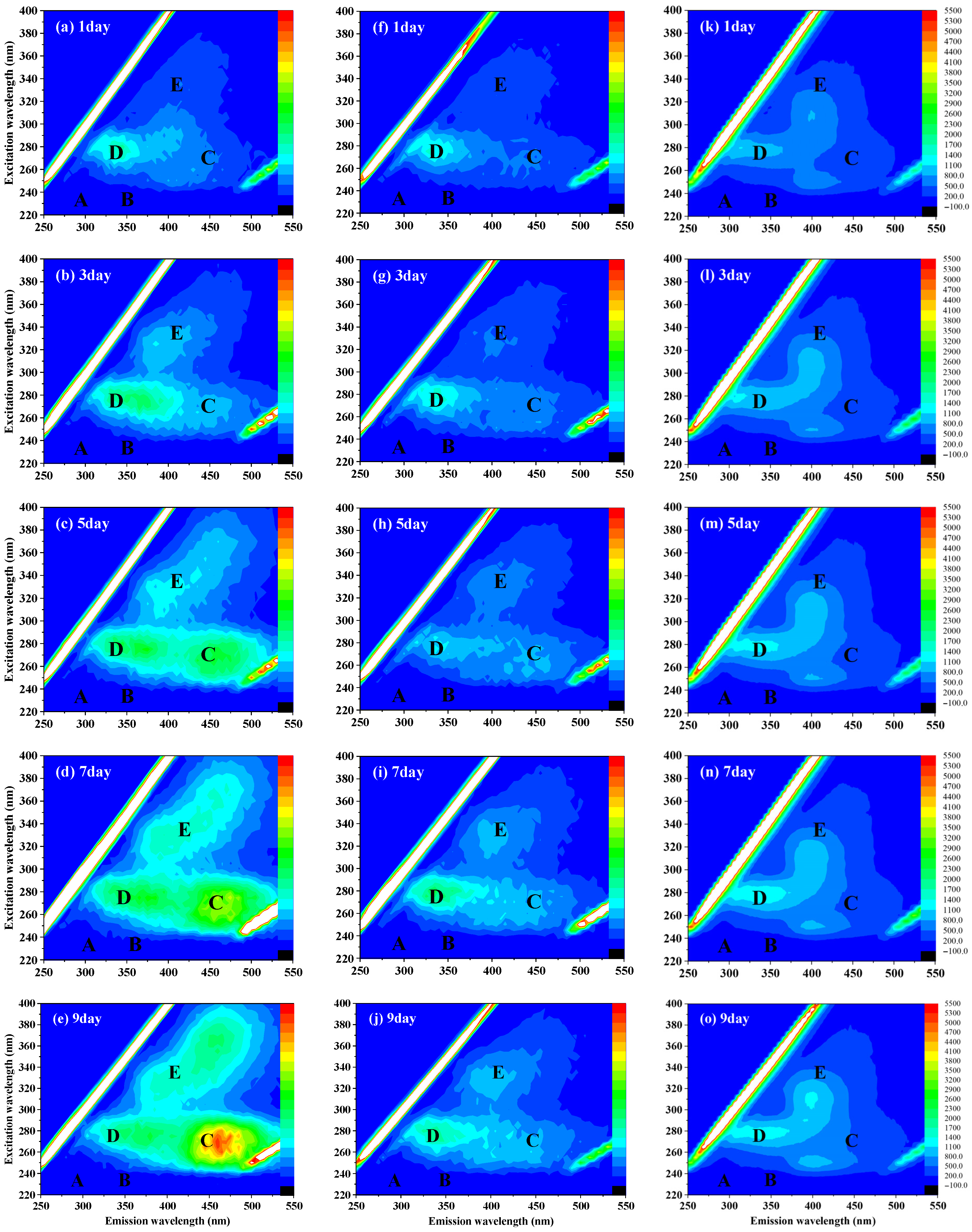

3.3. Effect of A20 on the Metabolic Release Capacity of Microcystis aeruginosa

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abu-Ali, L.; Albert, R.J.; Davis, A.B.; Gonsenhauser, R.; Foreman, K. From Bloom to Tap: Connecting Harmful Algal Bloom Indicators in Source Water to Cyanotoxin Presence in Treated Drinking Water. Harmful Algae 2025, 145, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J. Biogeochemical Cycling Processes Associated with Cyanobacterial Aggregates. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 2020, 60, 1922–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Kong, F.; Shi, X.; Zhang, M.; Xing, P.; Cao, H. Changes in the Morphology and Polysaccharide Content of Microcystis aeruginosa (Cyanobacteria) During Flagellate Grazing. J. Phycol. 2008, 44, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huang, Q.; Qin, B. Characteristics and Roles of Microcystis Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) in Cyanobacterial Blooms: A Short Review. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2018, 33, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, R.; Deng, J. Transcriptional Responses to Oxygen Gradients in Cyanobacterial Aggregates. Harmful Algae 2025, 148, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, C.; Guan, R.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, W.; Shi, J.; Sheng, Y.; Zhu, B.; Tu, J.; Ge, Q.; et al. Microbial Profiles of a Drinking Water Resource Based on Different 16S rRNA V Regions During a Heavy Cyanobacterial Bloom in Lake Taihu, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 12796–12808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wu, Z.; Song, L. Phenotype and Temperature Affect the Affinity for Dissolved Inorganic Carbon in a Cyanobacterium Microcystis. Hydrobiologia 2011, 675, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhu, W.; Guo, L.; Hu, J.; Chen, H.; Xiao, M. To Increase Size or Decrease Density? Different Microcystis Species Has Different Choice to Form Blooms. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L. The Mechanism of Buoyancy Regulation in the Process of Cyanobacterial Bloom. J. Lake Sci. 2023, 35, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, Z. Advances in Biological Function and Molecular Regulation of Cyanobacterial Surface Coats in Freshwaters. J. Lake Sci. 2021, 33, 1018–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Hou, X.; Qin, B.; Kutser, T.; Qu, F.; Chen, N.; Paerl, H.W.; Zheng, C. Harmful Algal Blooms in Inland Waters. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Deng, J. Determinants of Total and Active Microbial Communities Associated with Cyanobacterial Aggregates in a Eutrophic Lake. MSystems 2023, 8, e00992-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.K.; Baker, A.; Parsons, S.A.; Jefferson, B. Characterisation of Algogenic Organic Matter Extracted from Cyanobacteria, Green Algae and Diatoms. Water Res. 2008, 42, 3435–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Zhang, H.; Qian, A.; Yu, H.; Xu, C.; Pan, R.; Shi, Y. The Influence of Extracellular Polymeric Substances on the Coagulation Process of Cyanobacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Wang, F.; Jiang, H.; Huang, Q.; Xu, C.; Yu, P.; Cong, H. Analysis on the Flocculation Characteristics of Algal Organic Matters. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Shao, Y.; Gao, N.; Deng, Y.; Li, L.; Deng, J.; Tan, C. Characterization of Algal Organic Matters of Microcystis aeruginosa: Biodegradability, DBP Formation and Membrane Fouling Potential. Water Res. 2014, 52, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Li, A.; Shi, C.; Li, W. Research Progress on Relationship Between Algal Organic Matter Characteristics and Disinfection Byproducts Formation. China Environ. Sci. 2021, 41, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, J.; Guan, R.; Hale, L.; Chen, N.; Li, M.; Lu, Z.; Ge, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; et al. Alternate Succession of Aggregate-Forming Cyanobacterial Genera Correlated with Their Attached Bacteria by Co-Pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 688, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunberg, A. Contribution of Bacteria in the Mucilage of Microcystis spp. (Cyanobacteria) to Benthic and Pelagic Bacterial Production in a Hypereutrophic Lake. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1999, 29, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louati, I.; Pascault, N.; Debroas, D.; Bernard, C.; Humbert, J.; Leloup, J. Structural Diversity of Bacterial Communities Associated with Bloom-Forming Freshwater Cyanobacteria Differs According to the Cyanobacterial Genus. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Ren, M.; Yang, C.; Yi, H.; Li, Z.; Li, T.; Zhao, J. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals Symbiotic Relationship Among Bacteria in Microcystis-Dominated Community. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lin, F.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Shen, M.; Park, M.S.; Li, T.; Zhao, J. A Large-Scale Comparative Metagenomic Study Reveals the Functional Interactions in Six Bloom-Forming Microcystis-Epibiont Communities. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Kong, H.; Li, C.; Ding, W.; Wang, Y. The Effect on Algae Decay by Aeration under Light-shading Condition. Environ. Pollut. Control 2008, 30, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial Board of Water and Wastewater Monitoring and Analysis Method of State Environmental Protection Administration. Water and Wastewater Monitoring and Analysis Method, 4th ed.; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, S.; Zeng, J.; Song, W.; Yu, X. Comparing the Effects of Chlorination on Membrane Integrity and Toxin Fate of High- and Low-Viability Cyanobacteria. Water Res. 2020, 177, 115769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Huang, T.; Ning, C.; Sun, T.; Tao, P.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q. Changes of DOM and Its Correlation with Internal Nutrient Release during Cyanobacterial Growth and Decline in Lake Chaohu, China. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, A. Measuring UV-absorbing Organics: A Standard Method. J. AWWA 1995, 87, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Westerhoff, P.; Leenheer, J.A.; Booksh, K. Fluorescence Excitation−emission Matrix Regional Integration to Quantify Spectra for Dissolved Organic Matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5701–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, X. Distribution Characterization and Source Analysis of Dissolved Organic Matters in Taihu Lake Using Three Dimensional Fluorescence Excitation-Emission Matrix. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2010, 30, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, N.; Li, L.; Zhu, M.; Yang, J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y. Disinfection By-Product Formation during Chlor(Am)Ination of Algal Organic Matters (AOM) Extracted from Microcystis aeruginosa: Effect of Growth Phases, AOM and Bromide Concentration. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 8469–8478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, U.; Chakraborty, B.; Basnet, M. Plant Growth Promotion and Induction of Resistance in Camellia Sinensis by Bacillus Megaterium. J. Basic Microbiol. 2006, 46, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedendieck, R.; Knuuti, T.; Moore, S.J.; Jahn, D. The “Beauty in the Beast”—The Multiple Uses of Priestia megaterium in Biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 5719–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Liu, Z.; Jin, W. Biosynthesis, Catabolism and Related Signal Regulations of Plant Chlorophyll. Hereditas 2009, 31, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lin, L.-Z.; Zeng, Y.; Teng, W.-K.; Chen, M.-Y.; Brand, J.J.; Zheng, L.-L.; Gan, N.-Q.; Gong, Y.-H.; Li, X.-Y.; et al. The Facilitating Role of Phycospheric Heterotrophic Bacteria in Cyanobacterial Phosphonate Availability and Microcystis Bloom Maintenance. Microbiome 2023, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, R.; Zou, L.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gao, W.; Wang, R. Roles of Attached Bacteria on the Growth and Metabolism of Microcystis aeruginosa with Limited Soluble Phosphorus. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.D.; Ito, Y.; Homann, V.V.; Haygood, M.G.; Butler, A. Structure and Membrane Affinity of New Amphiphilic Siderophores Produced by Ochrobactrum Sp. SP18. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 11, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrede, T.; Tranvik, L.J. Iron Constraints on Planktonic Primary Production in Oligotrophic Lakes. Ecosystems 2006, 9, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Wei, Z.; Shao, Z.; Friman, V.-P.; Cao, K.; Yang, T.; Kramer, J.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Mei, X.; et al. Competition for Iron Drives Phytopathogen Control by Natural Rhizosphere Microbiomes. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, M.M.; Weisz, D.A.; Cheng, M.; Pakrasi, H.B.; Blankenship, R.E. Structure of Cyanobacterial Phycobilisome Core Revealed by Structural Modeling and Chemical Cross-Linking. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eaba5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, N.; Pal Singh, D.; Singh Khattar, J. Optimization, Characterization, and Flow Properties of Exopolysaccharides Produced by the Cyanobacterium Lyngbya Stagnina. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013, 53, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.N.; Cresswell-Maynard, T.; Thomas, D.N.; Underwood, G.J.C. Production and Characterization of the Intra- and Extracellular Carbohydrates and Polymeric Substances (EPS) of Three Sea-Ice Diatom Species, and Evidence for a Cryoprotective Role for EPS. J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 1494–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, Y. Enhanced Extracellular Polymeric Substances Production Defending Microalgal Cells Against the Stress of Tetrabromobisphenol A. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 2945–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casamatta, D.A.; Wickstrom, C.E. Sensitivity of Two Disjunct Bacterioplankton Communities to Exudates from the Cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa Kützing. Microb. Ecol. 2000, 40, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhu, W.; Gao, L.; Lu, L. Changes in Extracellular Polysaccharide Content and Morphology of Microcystis aeruginosa at Different Specific Growth Rates. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, M.T.; Lawrence, A.D.; Raux-Deery, E.; Warren, M.J.; Smith, A.G. Algae Acquire Vitamin B12 Through a Symbiotic Relationship with Bacteria. Nature 2005, 438, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazamia, E.; Sutak, R.; Paz-Yepes, J.; Dorrell, R.G.; Vieira, F.R.J.; Mach, J.; Morrissey, J.; Leon, S.; Lam, F.; Pelletier, E.; et al. Endocytosis-Mediated Siderophore Uptake as a Strategy for Fe Acquisition in Diatoms. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; de-Bashan, L.E.; Bashan, Y.; Higgins, B.T. Indole-3-Acetic Acid from Azosprillum brasilense Promotes Growth in Green Algae at the Expense of Energy Storage Products. Algal Res. 2020, 47, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Zhao, H.; Shen, H.; Kao, S.-J.; Jiao, N.; Zhang, Y. Inherent Tendency of Synechococcus and Heterotrophic Bacteria for Mutualism on Long-Term Coexistence Despite Environmental Interference. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabf4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, F.; Deng, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, T. Effects of Priestia megaterium A20 on the Aggregation Behavior and Growth Characteristics of Microcystis aeruginosa FACHB-912. Water 2025, 17, 3434. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233434

Sun F, Deng X, Wu L, Zhang C, Wang T. Effects of Priestia megaterium A20 on the Aggregation Behavior and Growth Characteristics of Microcystis aeruginosa FACHB-912. Water. 2025; 17(23):3434. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233434

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Feng, Xin Deng, Lei Wu, Chaoyang Zhang, and Tong Wang. 2025. "Effects of Priestia megaterium A20 on the Aggregation Behavior and Growth Characteristics of Microcystis aeruginosa FACHB-912" Water 17, no. 23: 3434. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233434

APA StyleSun, F., Deng, X., Wu, L., Zhang, C., & Wang, T. (2025). Effects of Priestia megaterium A20 on the Aggregation Behavior and Growth Characteristics of Microcystis aeruginosa FACHB-912. Water, 17(23), 3434. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233434