Resource Monitoring and Heat Recovery in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: Industrial Decarbonisation of the Food and Beverage Processing Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Monitoring Campaign

2.2. Wastewater Heat Recovery Experimental Set-Up

2.3. Energy Recovery and Techno-Economic Analysis

2.4. Food and Beverage Process Market Composition

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Embedded Energy in the Wastewater from Four Food and Beverage Processing Industries

3.2. Pilot Heat Recovery Analysis in a Wastewater Sump

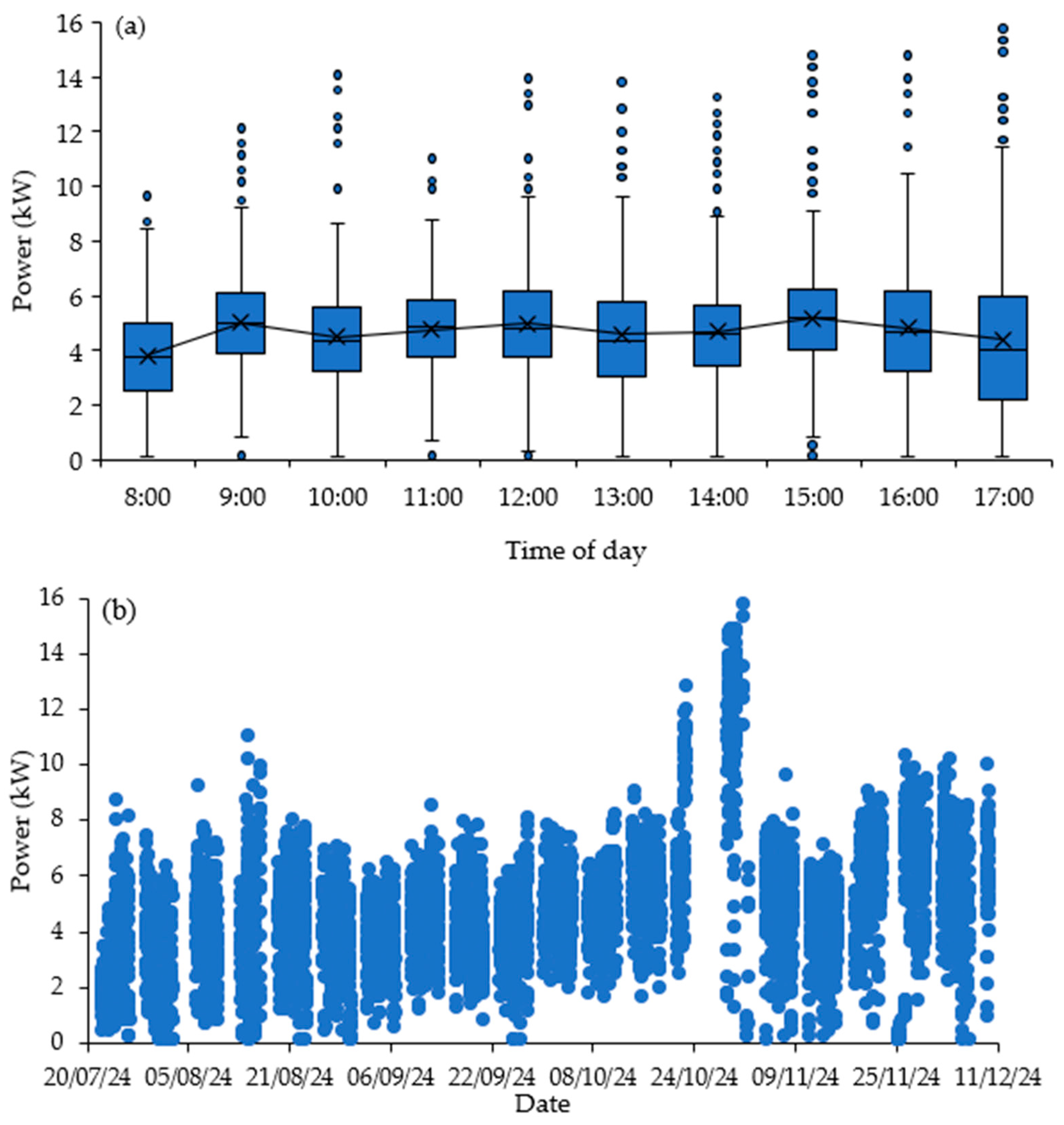

3.2.1. Direct Heat Recovery System

3.2.2. Indirect Heat Recovery System Incorporating Water-to-Water Heat Pump

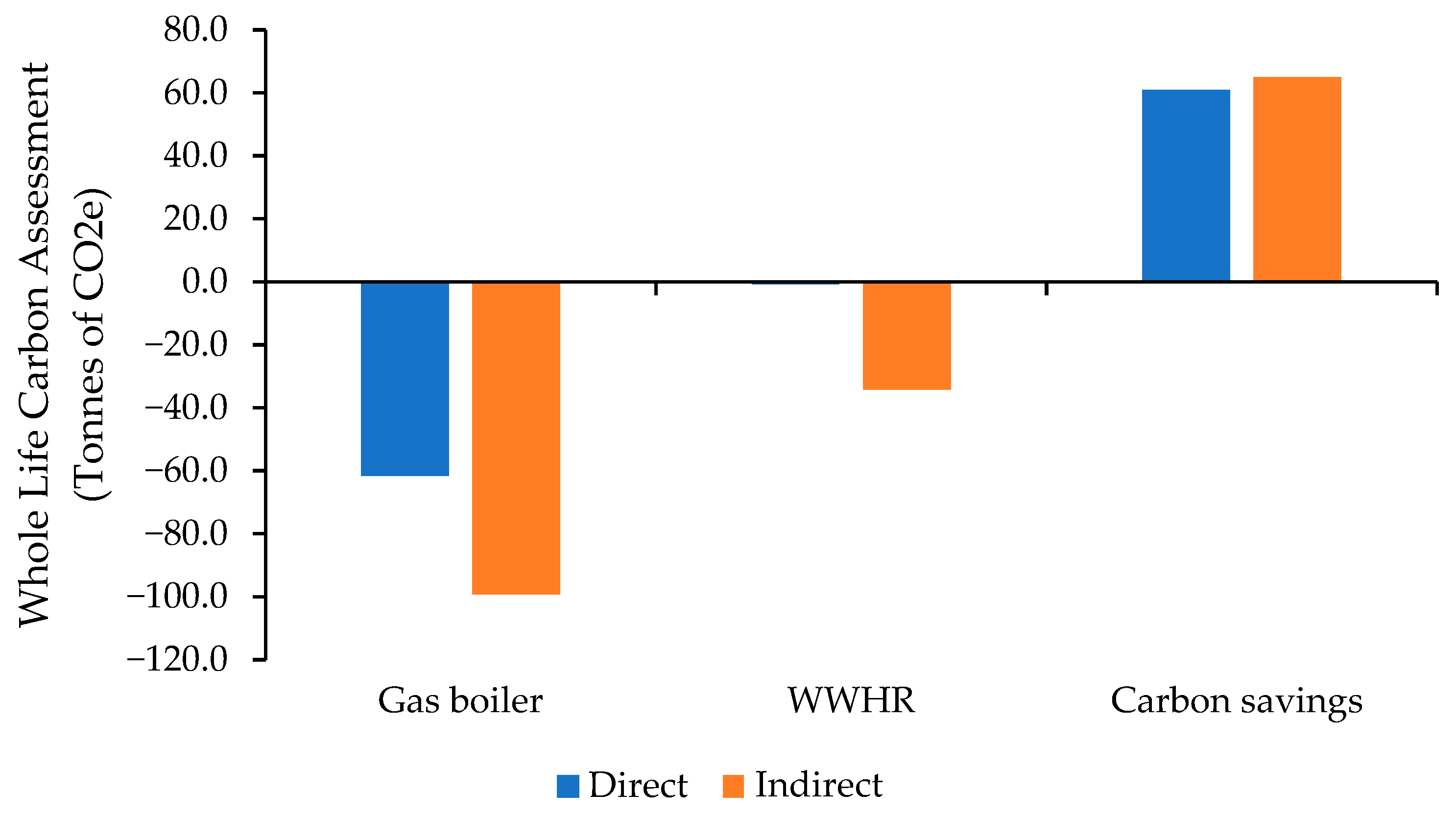

3.3. Techno-Economic Analysis and Carbon Assessment of the HX System

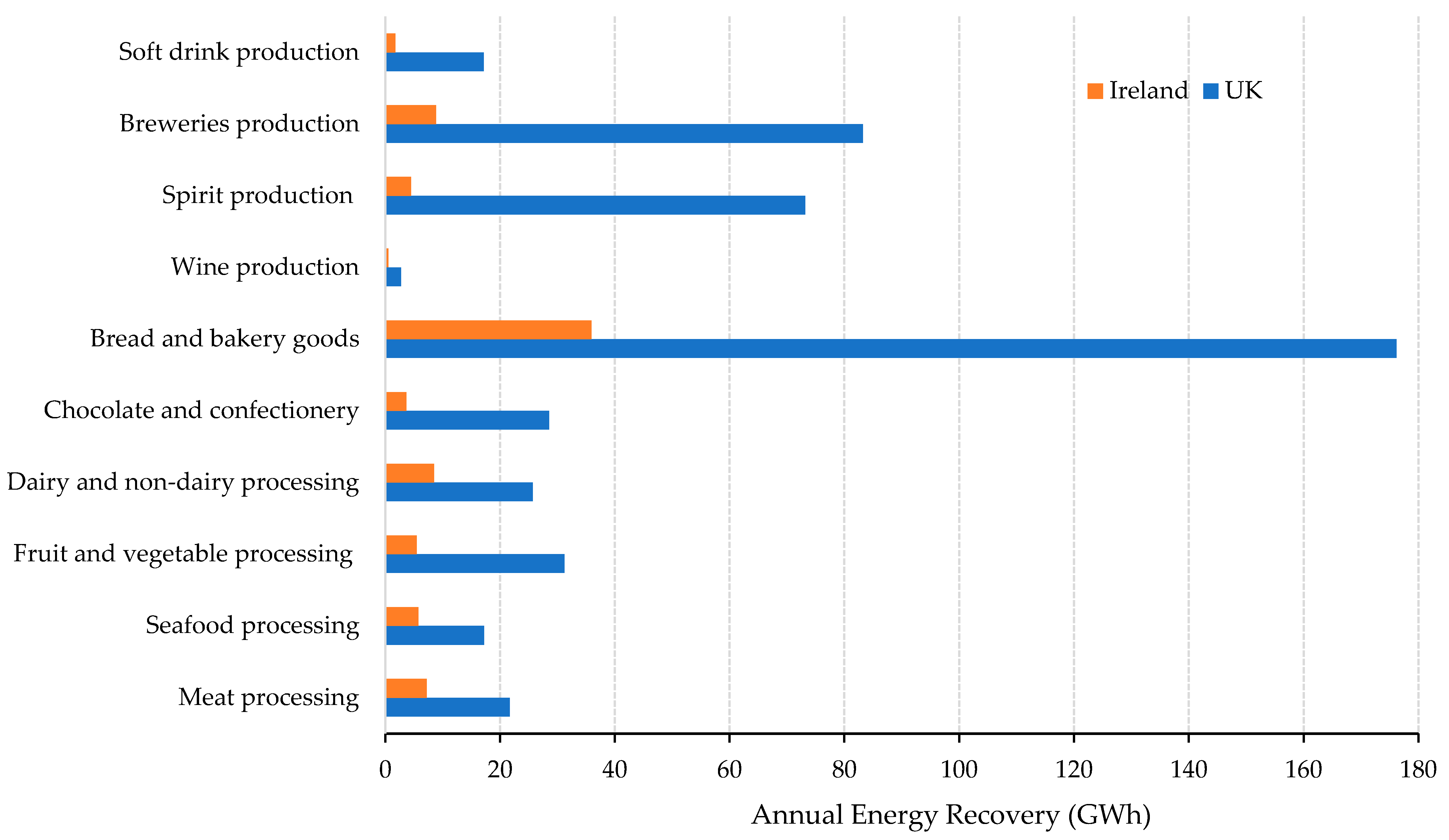

3.4. Heat Recovery at a National Scale: A Disaggregated Analysis of the Food and Beverage Processing Industry

3.5. WWTP Sump Designs

3.6. Impact of Electrical Grid on the Economic Viability of Heat Pump Integration into WWHR and Government Policy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Climate Action. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Stepping Up Europe’s 2030 Climate Ambition Investing in a Climate-Neutral Future for the Benefit of Our People. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0562 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- European Commission. Accelerate the Rollout of Renewable Energy. European Green Deal: EU Agrees Stronger Legislation to Accelerate the Rollout of Renewable Energy. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_23_2061 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Considine, B.; McNabola, A.; Kumar, P.; Gallagher, J. A Numerical Analysis of Particulate Matter Control Technology Integrated with HVAC System Inlet Design and Implications on Energy Consumption. Build. Environ. 2022, 211, 108726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Energy (European Commission); E-Think; Fraunhofer ISI; TU Wien; Viegand Maagoe; Öko-Institut e.V.; Kranzl, L.; Fallahnejad, M.; Büchele, R.; Müller, A.; et al. Renewable Space Heating Under the Revised Renewable Energy Directive: ENER/C1/2018-494: Final Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018—On the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, 61, 1–210. [Google Scholar]

- Culha, O.; Gunerhan, H.; Biyik, E.; Ekren, O.; Hepbasli, A. Heat Exchanger Applications in Wastewater Source Heat Pumps for Buildings: A Key Review. Energy Build. 2015, 104, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, H.; Spriet, J.; Murali, M.K.; McNabola, A. Heat Recovery from Wastewater—A Review of Available Resource. Water 2021, 13, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Cai, J.; Zeng, W.; Dong, H. Analytical Research on Waste Heat Recovery and Utilization of China’s Iron & Steel Industry. Energy Procedia 2012, 14, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijns, J.; Hofman, J.; Nederlof, M. The Potential of (Waste)Water as Energy Carrier. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 65, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spriet, J.; McNabola, A. Decentralized Drain Water Heat Recovery from Commercial Kitchens in the Hospitality Sector. Energy Build. 2019, 194, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Jagtap, S.; Trollman, H.; Garcia-Garcia, G. A Framework for Recovering Waste Heat Energy from Food Processing Effluent. Water 2023, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, F. Sewage Water: Interesting Heat Source for Heat Pumps and Chillers; HPT—Heat Pumping Technologies: Rapperswil, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://heatpumpingtechnologies.org/publications/sewage-water-interesting-heat-source-forheat-pumps-and-chillers/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Neugebauer, G.; Kretschmer, F.; Kollmann, R.; Narodoslawsky, M.; Ertl, T.; Stoeglehner, G. Mapping Thermal Energy Resource Potentials from Wastewater Treatment Plants. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12988–13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spriet, J.; McNabola, A.; Neugebauer, G.; Stoeglehner, G.; Ertl, T.; Kretschmer, F. Spatial and Temporal Considerations in the Performance of Wastewater Heat Recovery Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbi, Z.; Taher, R.; Faraj, J.; Lemenand, T.; Mortazavi, M.; Khaled, M. Waste Water Heat Recovery Systems Types and Applications: Comprehensive Review, Critical Analysis, and Potential Recommendations. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, J. Case Studies of Four Installed Wastewater Heat Recovery Systems in Sweden. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 26, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemele, J.; Volkova, A.; Latõšov, E.; Murauskaitė, L.; Džiuvė, V. Comparative Assessment of Heat Recovery from Treated Wastewater in the District Heating Systems of the Three Capitals of the Baltic Countries. Energy 2023, 280, 128132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.T.; Mui, K.W.; Guan, Y. Shower Water Heat Recovery in High-Rise Residential Buildings of Hong Kong. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaloum, C.; Gusdorf, J.; Parekh, A. Drainwater Heat Recovery Performance Testing at Canadian Centre for Housing Technology, 07–116, Canadian Centre for Housing Technology. 2007. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2008/cmhc-schl/nh18-22/NH18-22-107-116E.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Spriet, J.; Singh, A.P.; Considine, B.; Murali, M.K.; McNabola, A. Design and Long-Term Performance of a Pilot Wastewater Heat Recovery System in a Commercial Kitchen in the Tourism Sector. Water 2023, 15, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torras, S.; Oliet, C.; Rigola, J.; Oliva, A. Drain Water Heat Recovery Storage-Type Unit for Residential Housing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 103, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, M.K.; Spriet, J.; McNabola, A. Recycling Waste Heat from Industrial Wastewater Treatment Processes. In Proceedings of the 40th IAHR World Congress, Vienna, Austria, 21–25 August 2023; pp. 1570–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadwiszczak, P.; Niemierka, E. Thermal Effectiveness and NTU of Horizontal Plate Drain Water Heat Recovery Unit—Experimental Study. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 147, 106938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, B.; Coughlan, P.; Murali, M.K.; Nikou, N.; Gill, L.; McNabola, A. Techno-Economic Analysis of Wastewater Heat Recovery in the Hospitality Sector: A Case Study of a Commercial Kitchen’s Grease Interceptor. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J. Application of a Heat Pump System Using Untreated Urban Sewage as a Heat Source. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 62, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postrioti, L.; Baldinelli, G.; Bianchi, F.; Buitoni, G.; Maria, F.D.; Asdrubali, F. An Experimental Setup for the Analysis of an Energy Recovery System from Wastewater for Heat Pumps in Civil Buildings. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 102, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaloum, C.; Gusdorf, J.; Parekh, A. Performance Evaluation of Drain Water Heat Recovery Technology at the Canadian Centre for Housing Technology; Sustainable Buildings and Communities Natural Resources Canada Ottawa: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murali, M.K.; Mancusi-Ungaro, E.; Tembo, D.B.; Hampwaye, G.; Coughlan, P.; McNabola, A. Wastewater Heat Recovery in Industrial Food Production in Zambia: Pilot Plant Implementation, Performance Monitoring, and Wider Uptake Potential; OSF, 2024; Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/osf/5rzu8_v1 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Mikkonen, L.; Rämö, J.; Keiski, R.; Pongrácz, E. Heat Recovery from Wastewater: Assessing the Potential in Northern Areas. In Proceedings of the Water Research Conference, Oulu, Finland, 13–15 August 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzar, F.; Silveira, S. Impact of Wastewater Heat Recovery in Buildings on the Performance of Centralized Energy Recovery—A Case Study of Stockholm. Appl. Energy 2021, 297, 117141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddah, S.; Deymi-Dashtebayaz, M.; Maddah, O. 4E Analysis of Thermal Recovery Potential of Industrial Wastewater in Heat Pumps: An Invisible Energy Resource from the Iranian Casting Industry Sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spriet, J.; McNabola, A. Decentralized Drain Water Heat Recovery: A Probabilistic Method for Prediction of Wastewater and Heating System Interaction. Energy Build. 2019, 183, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D. A Life Cycle Cost Analysis of an Irish Dwelling Retrofitted to Passive House Standard: Can Passive House Become a Cost-Optimal Low-Energy Retrofit Standard? Master’s Thesis, Technological University Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Considine, B.; Liu, Y.; McNabola, A. Energy Savings Potential and Life Cycle Costs of Deep Energy Retrofits in Buildings with and without Habitable Style Loft Attic Conversions: A Case Study of Irelands Residential Sector. Energy Policy 2024, 185, 113980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.S.; Strecker, J. Commercial, Industrial, and Institutional Discount Rate Estimation for Efficiency Standards Analysis. Sector-Level Data 1998–2023. 2024. Available online: https://eta-publications.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/commercial_industrial_discount_rates_2024_0506.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Nagels, M.; Verhoeven, B.; Larché, N.; Dewil, R.; Rossi, B. Comparative Life Cycle Cost Assessment of (Lean) Duplex Stainless Steel in Wastewater Treatment Environments. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 306, 114375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Bevacqua, A.; Tembe, S.; Lal, P. Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) of Residential Ground Source Heat Pump Systems: A Comparative Analysis of Energy Efficiency in New Jersey. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unitherm. Water Source Heat Pumps: Everything You Need to Know; Unitherm Heating Systems: Newcastle, Ireland, 2024; Available online: https://unitherm.co.uk/blogs/news/water-source-heat-pumps (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- SEAI. Commercial Fuel Cost Comparison. 2024. Available online: https://www.seai.ie/publications/Commercial-Fuel-Cost-Comparison.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Bord Gáis Energy. Servicing|Boiler and Heat Pump Services. Bord Gáis Energy. 2024. Available online: https://www.bordgaisenergy.ie/services/service (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Energy Data Downloads|SEAI Statistics|SEAI. Energy Data Downloads. 2023. Available online: https://www.seai.ie/data-and-insights/seai-statistics/key-statistics/energy-data/#comp00005c0fcbea00000088e671a3 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Smith, R. Directive 2008/94/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2008; Core EU Legislation; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 2015; pp. 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibisw Inc. IBISWorld—Industry Market Research, Reports, & Statistics; IBISWorld: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://www.ibisworld.com/default.aspx (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Georgiou, E.; Raffin, M.; Colquhoun, K.; Borrion, A.; Campos, L.C. The Significance of Measuring Embodied Carbon Dioxide Equivalent in Water Sector Infrastructure. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, S.; Jones, C.; Sharples, S. The Embodied CO2e of Sustainable Energy Technologies Used in Buildings: A Review Article. Energy Build. 2018, 181, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancusi-Ungaro, E.; Murali, M.K.; Coughlan, P.; Hampwaye, G.; Tembo, D.B.; McNabola, A. Assessing wastewater heat resources in Zambian food and beverage processing: Case studies, regional assessment, and implications. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature outlet | 19.59 °C | 3.02 °C |

| COP @ 35 °C | 7.10 | 0.51 |

| COP @ 45 °C | 5.57 | 0.40 |

| COP @ 55 °C | 4.37 | 0.31 |

| Win @ 35 °C | 0.99 kW | 0.07 kW |

| Win @ 45 °C | 1.26 kW | 0.10 kW |

| Win @ 55 °C | 1.61 kW | 0.12 kW |

| Annual electrical energy use @ 35 °C | 2467 kWh | 185 kWh |

| Annual electrical energy use @ 45 °C | 3143 kWh | 300 kWh |

| Annual electrical energy use @ 55 °C | 4004 kWh | 487 kWh |

| Fuel Band | Thermal Energy | Electrical Energy | Capital Cost | O&M Cost | ETS | LCC Savings | PBP | LCC Savings | PBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUR/kWh | kWh/a | kWh/a | EUR | EUR | EUR/a | EUR | yrs | EUR | yrs |

| Direct System | Without ETS non-compliance | With ETS non-compliance | |||||||

| I1 | 10,874 | N/A | 2000 | 200 for gas boiler only | 247 | 14,819 | 2 | EUR 16,679 | 2 |

| I2 | 10,563 | 2 | EUR 12,513 | 2 | |||||

| I3 | 8357 | 3 | EUR 10,308 | 2 | |||||

| I4 | 6519 | 3 | EUR 8470 | 2 | |||||

| I5 | 3946 | 4 | EUR 5897 | 3 | |||||

| Indirect system with water-to-water heat pump (COP at 55 °C) | Without ETS non-compliance | With ETS non-compliance | |||||||

| I1–IA | 17,503 | 4004 | 9412 | 200 and 249 for gas boiler and heat pump, respectively | 266 | 6292 | 14 | EUR 9311 | 10 |

| I5–IG | −12,692 | NV | −EUR 9674 | NV | |||||

| I1–IG | 14,703 | 8 | EUR 17,721 | 7 | |||||

| Average | −3754 | NV | −EUR 735 | NV | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Considine, B.; Coughlan, P.; Murali, M.K.; Gill, L.; Moher, L.; Novakowski, L.; McNabola, A. Resource Monitoring and Heat Recovery in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: Industrial Decarbonisation of the Food and Beverage Processing Sector. Water 2025, 17, 3419. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233419

Considine B, Coughlan P, Murali MK, Gill L, Moher L, Novakowski L, McNabola A. Resource Monitoring and Heat Recovery in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: Industrial Decarbonisation of the Food and Beverage Processing Sector. Water. 2025; 17(23):3419. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233419

Chicago/Turabian StyleConsidine, Brian, Paul Coughlan, Madhu K. Murali, Laurence Gill, Lena Moher, Lucas Novakowski, and Aonghus McNabola. 2025. "Resource Monitoring and Heat Recovery in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: Industrial Decarbonisation of the Food and Beverage Processing Sector" Water 17, no. 23: 3419. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233419

APA StyleConsidine, B., Coughlan, P., Murali, M. K., Gill, L., Moher, L., Novakowski, L., & McNabola, A. (2025). Resource Monitoring and Heat Recovery in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: Industrial Decarbonisation of the Food and Beverage Processing Sector. Water, 17(23), 3419. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233419