Assessment of Groundwater Environmental Quality and Analysis of the Sources of Hydrochemical Components in the Nansi Lake, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

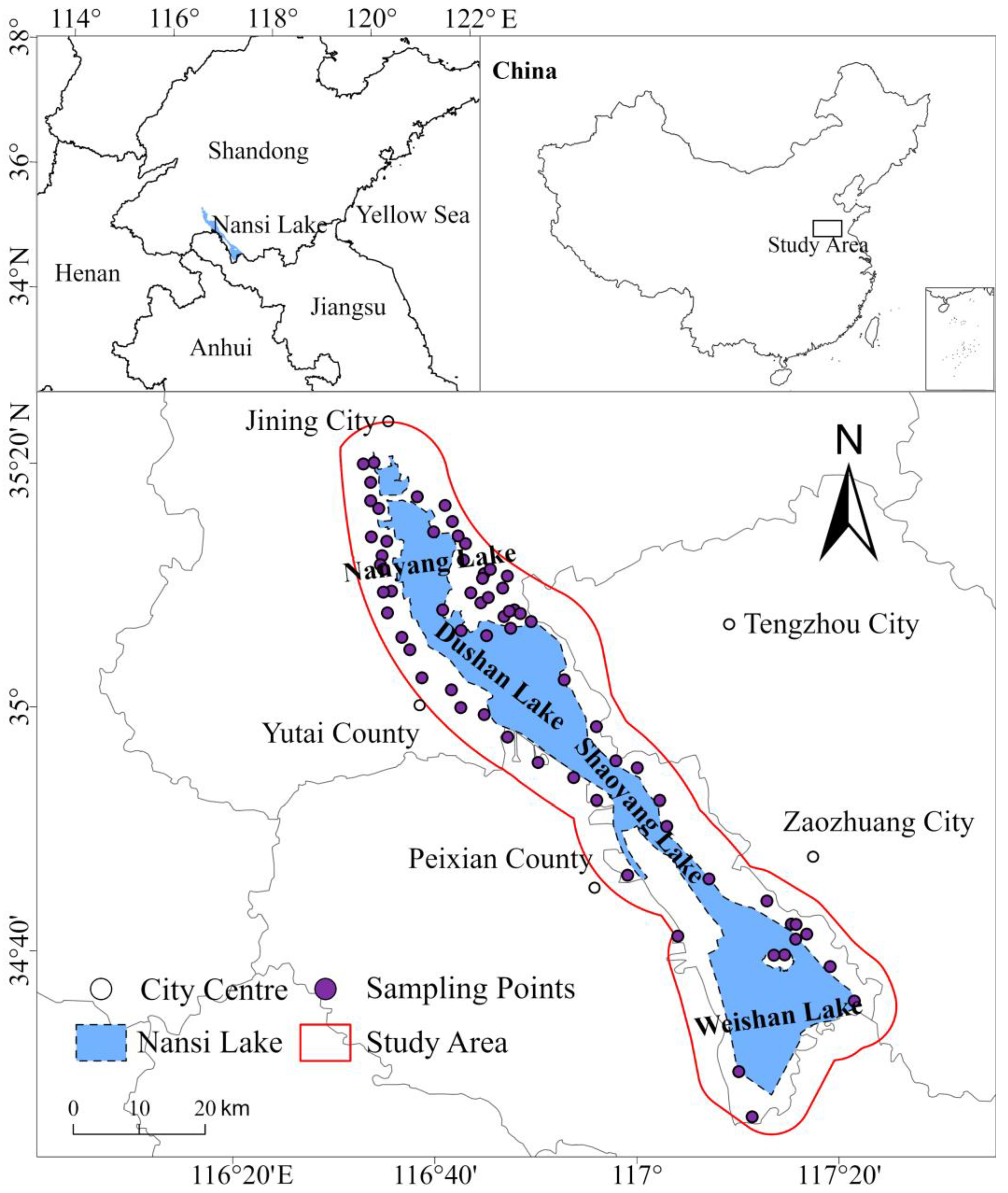

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

2.2. Geological Structure of the Study Area

2.3. Groundwater Resources in the Study Area

2.4. Schukalev Classification Method (SCM)

2.5. Entropy-Weight Quality Index (EWQI) Method

2.6. Absolute Principal Component Scores-Multiple Linear Regression (APCS-MLR) Model

3. Results and Discussion

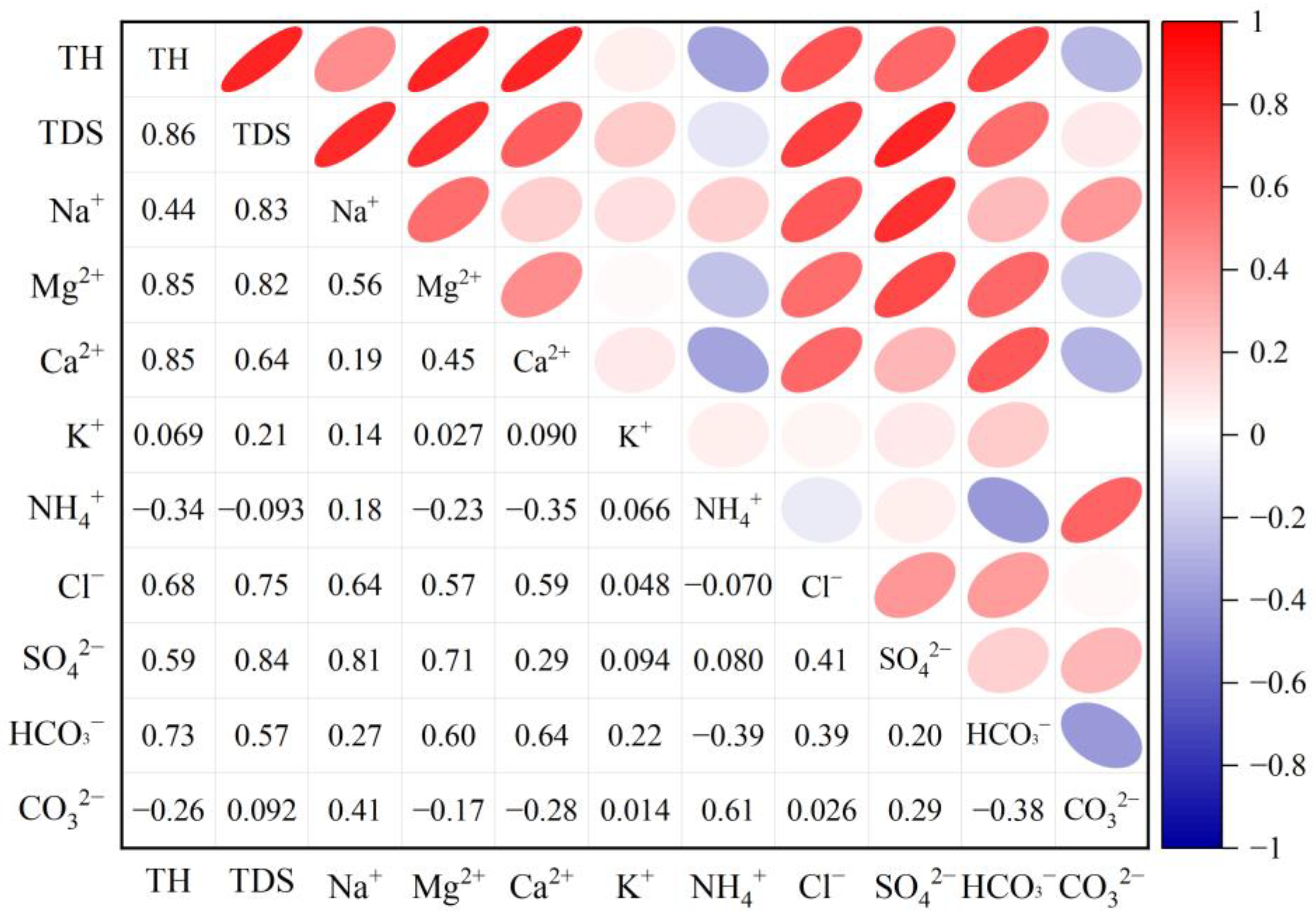

3.1. Statistical Characteristics of Groundwater Hydrochemical Parameters

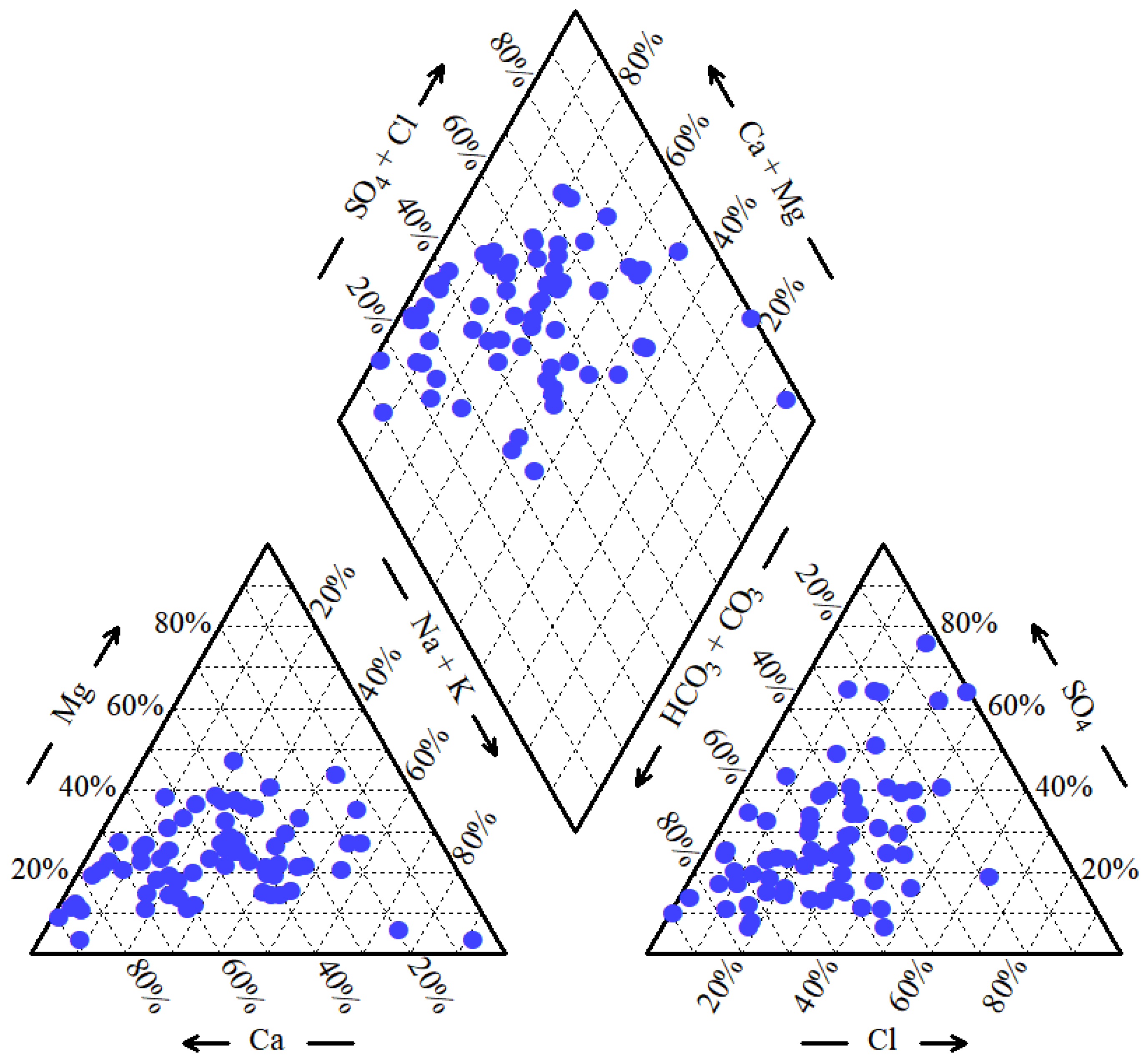

3.2. Groundwater Hydrochemical Classification

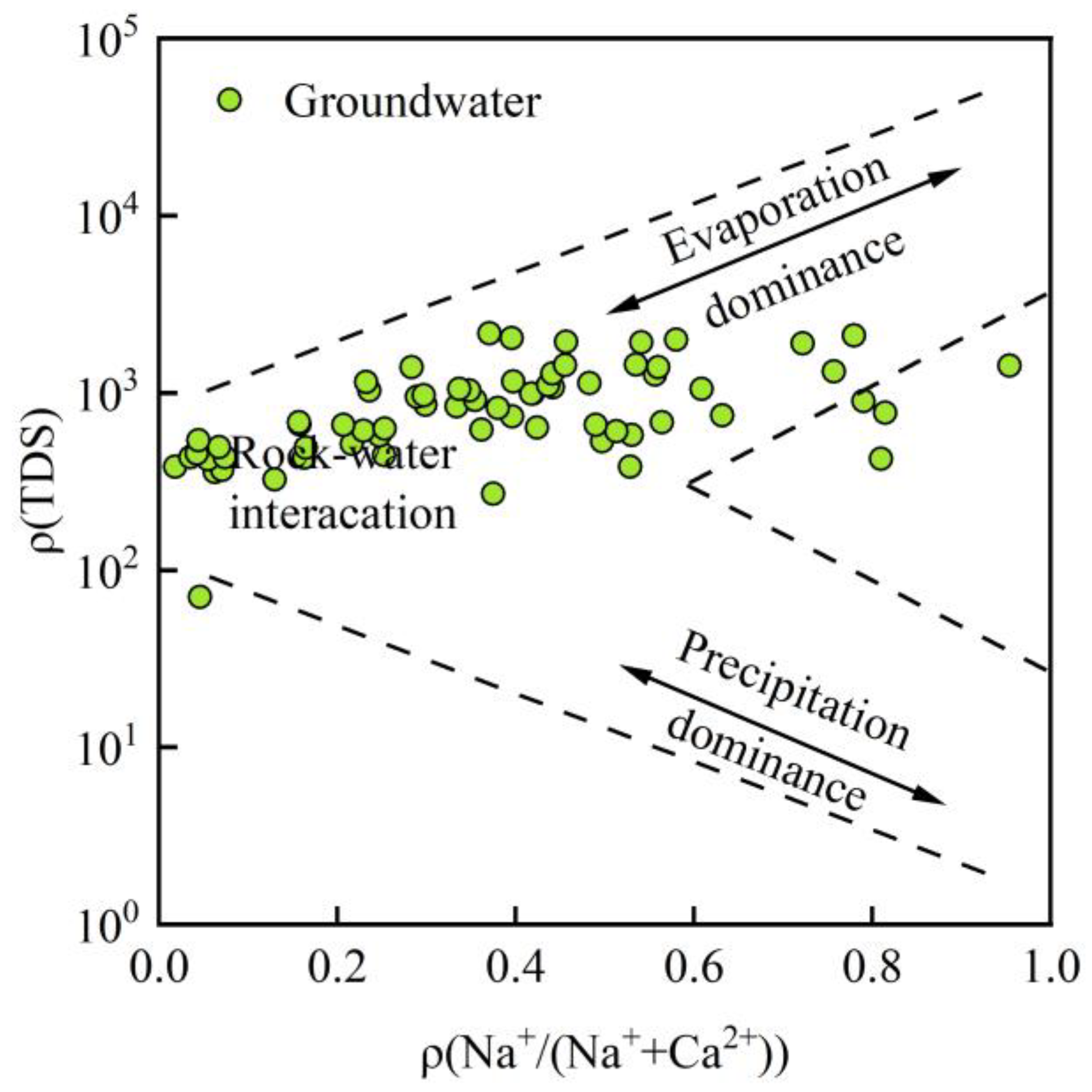

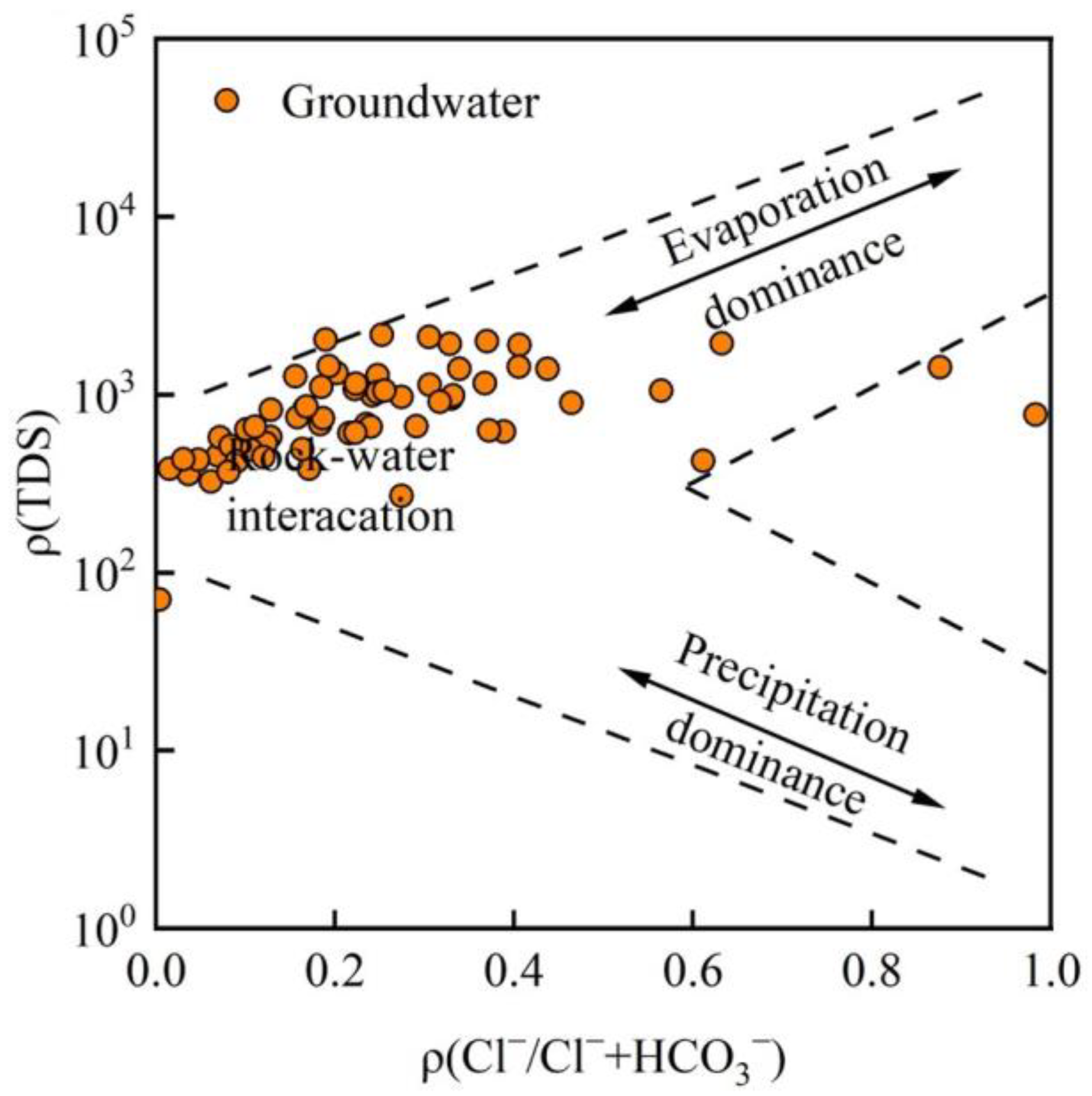

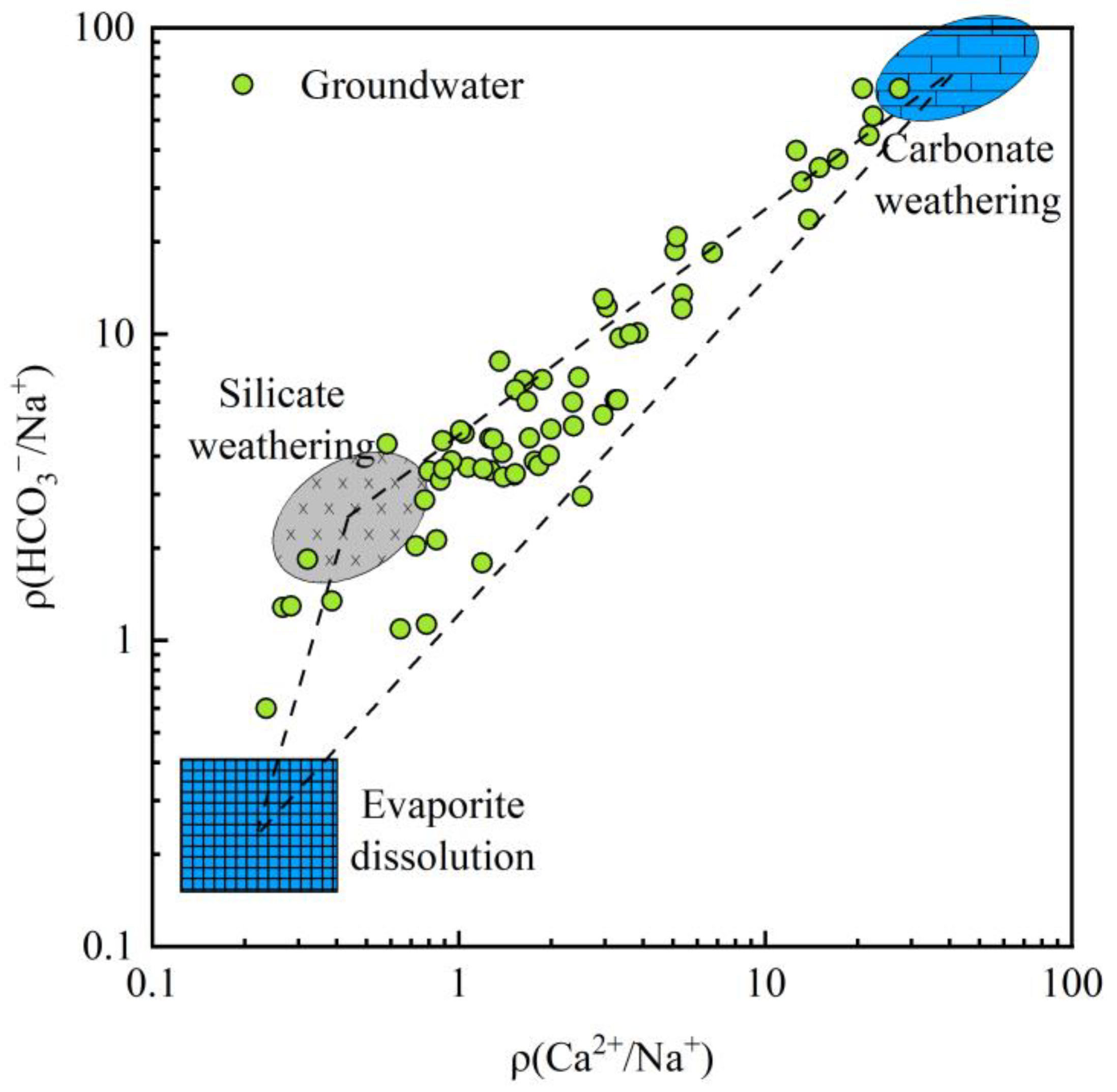

3.3. Evolutionary Processes of Groundwater Hydrochemistry

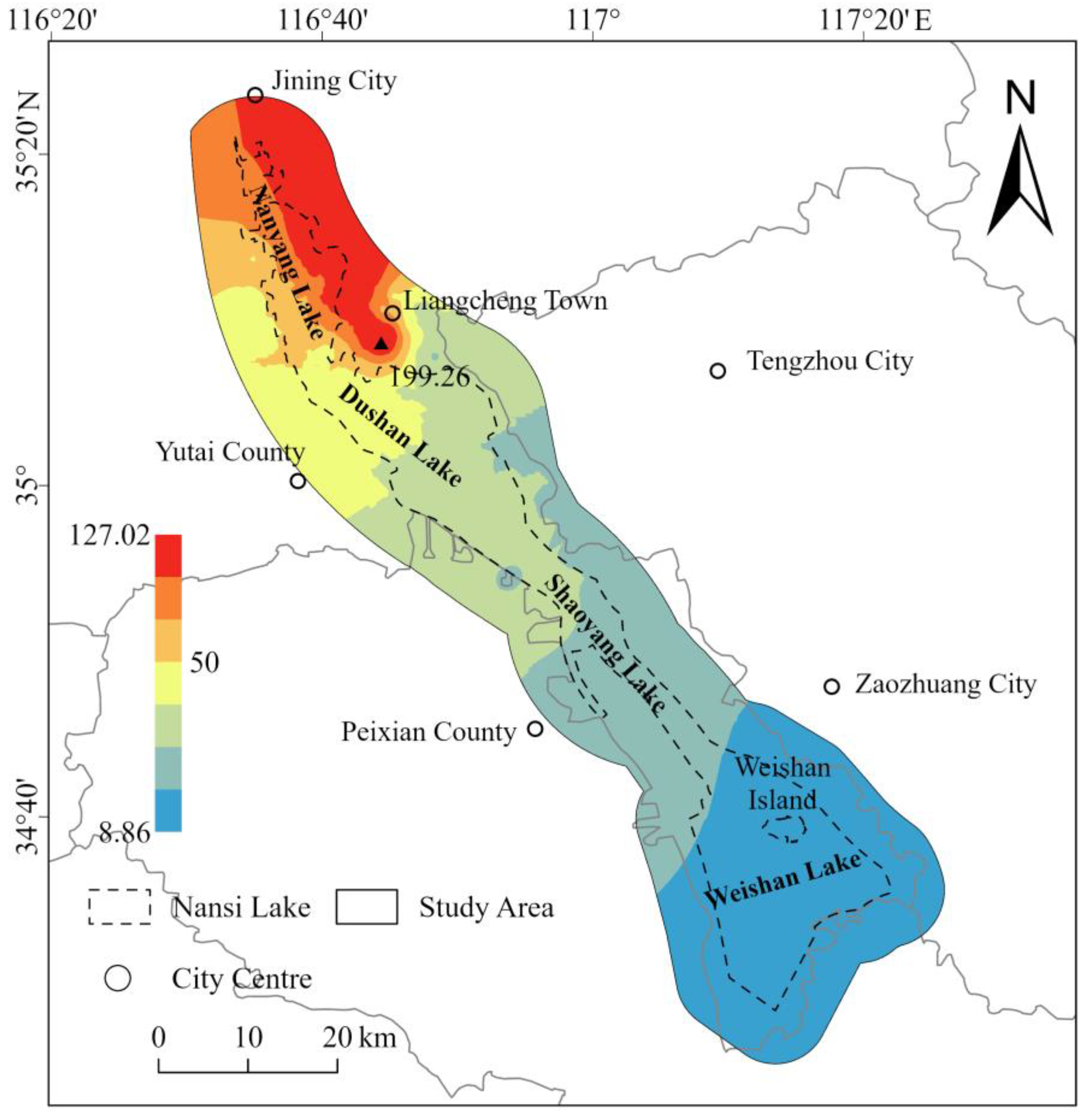

3.4. Groundwater Quality Assessment

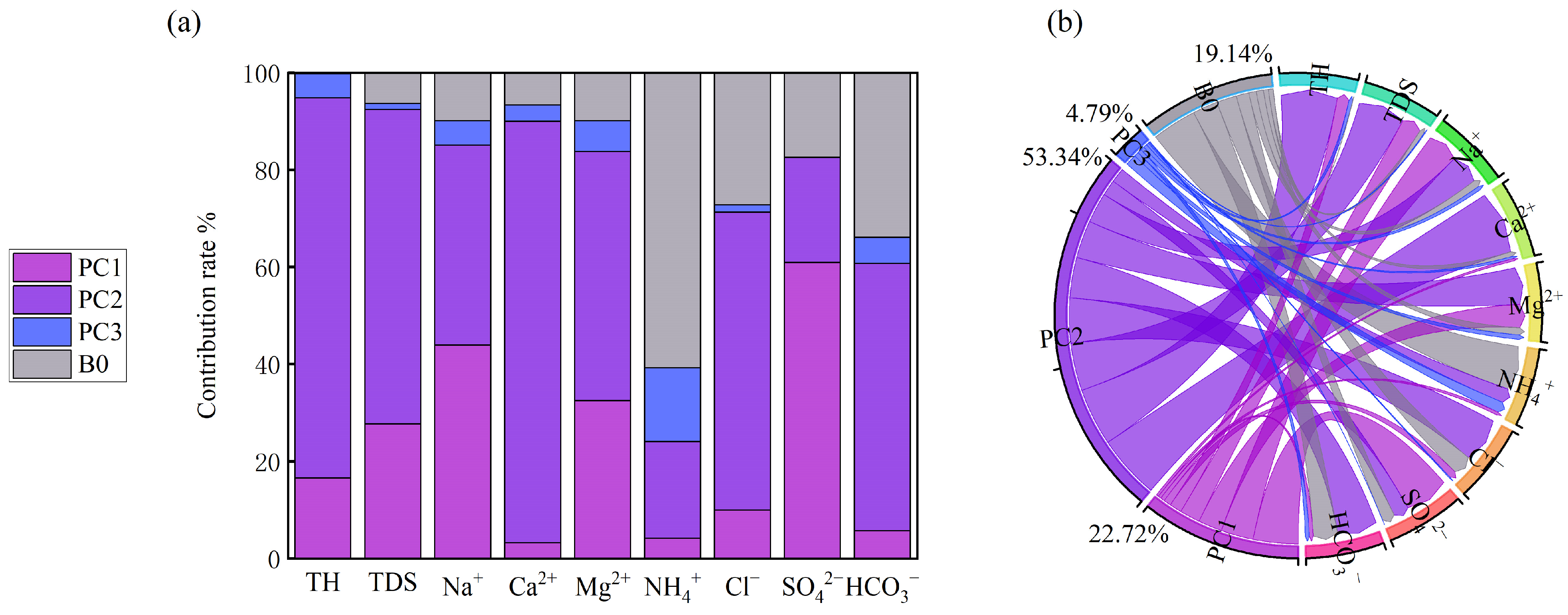

3.5. Source Apportionment by APCS-MLR

3.6. Implications for Similar Large Lake Basins and Plain Regions

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Hydrochemical characteristics and evolution. Groundwater in the study area is characterized by relatively high mineralization and hardness, with 55.22% of samples exceeding the Grade III standard limit for TH and 35.82% exceeding the limit for TDS. The dominant hydrochemical facies are HCO3–Ca, HCO3–Ca·Mg, and HCO3·Cl–Na·Ca, accounting for 13.43%, 10.45% and 7.46% of the samples, respectively. These types indicate that HCO3− and Ca2+ are the prevailing ions and that groundwater has undergone extensive ion exchange and dissolution processes involving carbonate and silicate rocks.

- (2)

- Controlling processes. Gibbs plots and key ion ratios show that rock–water interaction is the primary process controlling the present groundwater hydrochemical environment, while evaporation–concentration plays a secondary role. The mixed weathering and dissolution of carbonate and silicate minerals are the main natural mechanisms driving the evolution of groundwater chemistry in the basin.

- (3)

- Groundwater environmental quality pattern. EWQI results indicate that groundwater quality in most of the Nansi Lake Basin is good: 68.66% of samples are classified as Class I and 20.90% as Class II, which are suitable for centralized domestic supply and general household use. However, areas with poorer groundwater quality (Classes III–IV) are mainly concentrated in the northern part of the basin, particularly around Dushan Lake and the eastern shore of Nanyang Lake, where intensive agriculture and historical mining activities are likely to have degraded groundwater quality.

- (4)

- Source apportionment and management implications. APCS–MLR source apportionment identifies four major sources: natural (53.34%), agricultural (22.71%), ion-exchange (4.79%), and an unknown anthropogenic source (19.14%). These results confirm that natural geologic conditions and water–rock interaction dominate groundwater chemistry, but anthropogenic impacts from fertilizer application, sewage discharge, and legacy mining cannot be neglected—especially in the northern agricultural and mining zones. To safeguard groundwater used for domestic and ecological purposes, it is necessary to strengthen groundwater pollution early-warning systems, remediate historical agricultural and industrial problems, improve rural and small-town wastewater treatment, and promote experience sharing in groundwater protection with well-managed areas such as Weishan Lake.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao, Y.; Guo, S.; Andrews, C.B.; Zhang, F.; Lancia, M.; Kuang, X.; Zheng, C. Seeing China’s Invisible Groundwater: Advances and Challenges. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR038980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. Groundwater Quality in Western China: Challenges and Paths Forward for Groundwater Quality Research in Western China. Expo. Health 2016, 8, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnoudse, E.; Bluemling, B.; Qu, W.; Herzfeld, T. Groundwater Regulation in Case of Overdraft: National Groundwater Policy Implementation in North-West China. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2019, 35, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Jin, J.; Song, B. Water Safety Issues of China and Ensuring Roles of Groundwater. Acta Geol. Sin. 2016, 90, 2939–2947. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, S.; Yi, J.; Xu, M. Analysis of surface water hydro-chemical characteristics in the Nansihu Lake basin. Tech. Superv. Water Resour. 2023, 7, 206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Jian, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jin, P.; Gao, S.; Wang, Q.; Ding, Z.; Wang, D.; Ma, Z. Distribution of Groundwater Hydrochemistry and Quality Assessment in Hutuo River Drinking Water Source Area of Shijiazhuang (North China Plain). Water 2024, 16, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Kazemi, H.; Ehtashemi, M.; Rockaway, T.D. Assessment of Groundwater Quantity and Quality and Saltwater Intrusion in the Damghan Basin, Iran. Chem. Erde-Geochem. 2016, 76, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Zhao, Z.; Duan, L.; Sun, Y. Hydrogeochemical Behavior of Shallow Groundwater around Hancheng Mining Area, Guanzhong Basin, China. Water 2024, 16, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.; Wu, X.; Mu, W. Hydrogeochemistry, Identification of Hydrogeochemical Evolution Mechanisms, and Assessment of Groundwater Quality in the Southwestern Ordos Basin, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 901–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Fang, Y.; Qian, H.; Liu, R.; Ma, H. Hydrogeochemical Characteristics and Quality Assessment of Groundwater in an Irrigated Region, Northwest China. Water 2019, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaibu, A.; Kalin, R.M.; Phoenix, V.; Banda, L.C.; Lawal, I.M. Hydrogeochemistry and Water Quality Index for Groundwater Sustainability in the Komadugu-Yobe Basin, Sahel Region. Water 2024, 16, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Celestino, A.E.; Ramos Leal, J.A.; Martínez Cruz, D.A.; Tuxpan Vargas, J.; De Lara Bashulto, J.; Morán Ramírez, J. Identification of the Hydrogeochemical Processes and Assessment of Groundwater Quality, Using Multivariate Statistical Approaches and Water Quality Index in a Wastewater Irrigated Region. Water 2019, 11, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.J.S.; Augustine, C.M. Entropy-Weighted Water Quality Index (EWQI) Modeling of Groundwater Quality and Spatial Mapping in Uppar Odai Sub-Basin, South India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbueri, J.C.; Ezugwu, C.K.; Ameh, P.D.; Unigwe, C.O.; Ayejoto, D.A. Appraising Drinking Water Quality in Ikem Rural Area (Nigeria) Based on Chemometrics and Multiple Indexical Methods. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, M.R.; Mahanty, B.; Sahoo, S.K.; Jha, V.N.; Sahoo, N.K. Assessment of Groundwater Geochemistry Using Multivariate Water Quality Index and Potential Health Risk in Industrial Belt of Central Odisha, India. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 303, 119161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.; An, K.-G. Application of Multivariate Statistical Techniques and Water Quality Index for the Assessment of Water Quality and Apportionment of Pollution Sources in the Yeongsan River, South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cheng, S.; Li, H.; Fu, K.; Xu, Y. Groundwater Pollution Source Identification and Apportionment Using PMF and PCA-APCA-MLR Receptor Models in a Typical Mixed Land-Use Area in Southwestern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wu, J.; Zhou, C.; Nsabimana, A. Groundwater Pollution Source Identification and Apportionment Using PMF and PCA-APCS-MLR Receptor Models in Tongchuan City, China. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 81, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; You, Y.; Liu, C. Enhanced Assessment of Water Quality and Pollutant Source Apportionment Using APCS-MLR and PMF Models in the Upper Reaches of the Tarim River. Water 2024, 16, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Lv, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, H.; Yang, H.; Mei, S.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Y.; et al. Assessment of Groundwater Quality Using APCS-MLR Model: A Case Study in the Pilot Promoter Region of Yangtze River Delta Integration Demonstra-tion Zone, China. Water 2023, 15, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zuo, R.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Teng, Y.; Shi, R.; Zhai, Y. Apportionment and Evolution of Pollution Sources in a Typical Riverside Groundwater Resource Area Using PCA-APCS-MLR Model. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2018, 218, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Li, X.; Qian, J.; Wang, Z.; Hou, X.; Gui, C.; Bai, Z.; Fu, C.; Li, J.; Zuo, X. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Shallow and Deep Groundwater in the Heilongdong Spring Basin, Northern China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Ye, H.; Shi, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, R.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Jin, Z. Using PCA-APCS-MLR Model and SIAR Model Combined with Multiple Isotopes to Quantify the Nitrate Sources in Groundwater of Zhuji, East China. Appl. Geochem. 2022, 143, 105354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yue, Q.; Ni, H.; Gao, B. Fractionation and Potential Risk of Heavy Metals in Surface Sediment of Nansi Lake, China. Desalination Water Treat. 2011, 32, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ling, J.; Chang, B.; Zhao, G. Assessment of Heavy Metal Content, Distribution, and Sources in Nansi Lake Sediments, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 30929–30942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.; Xin, Y. Detection and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Upper Water of Nansi Lake, China. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Cui, Y.; Yang, C.; Wei, S.; Dong, W.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.; Ren, Z.; Wang, W. The Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation (FCE) and the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Model Simulation and Its Applications in Water Quality Assessment of Nansi Lake Basin, China. Environ. Eng. Res. 2021, 26, 200022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, W. Coupling Coordination and Spatiotemporal Dynamic Evolution between Social Economy and Water Environmental Quality—A Case Study from Nansi Lake Catchment, China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 119, 106870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Han, C.; Yuan, S.; Liu, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, C. Assessment of the Hydrochemistry, Water Quality, and Human Health Risk of Groundwater in the Northwest of Nansi Lake Catchment, North China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2022, 44, 961–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DZ/T 0064–2021; Methods for Analysis of Groundwater Quality. Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- HJ 812–2016; Water Quality-Determination of Water Soluble Cations (Li+, Na+, NH4+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) -Ion Chromatography. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- HJ 84–2016; Water Quality-Determination of Inorganic Anions (F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, PO43−, SO32−, SO42−)-Ion Chromatography. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- HJ 666–2013; Water Quality-Determination of Ammonium Nitrogen by Flow Injection Analysis (FIA) and Salicylic Acid Spectrophotometry. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Liu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xu, G. Application of the Comprehensive Identification Model in Analyzing the Source of Water Inrush. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, X.; Du, J.; Cui, Y.; Sun, F. Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of the Haiyuan-Liupanshan Seismic Belt at the Northeastern Edge of the Tibet Plateau. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 6894229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; He, P.; Wei, L.; Huang, L.; He, M. Chemical Characteristics and Water Quality Assessment of Groundwater in Wusheng Section of Jialing River. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Bi, D.; Wei, H.; Zheng, X.; Man, X. Evaluation of Groundwater Quality and Health Risk Assessment in Dawen River Basin, North China. Environ. Res. 2025, 264, 120292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 14848–2017; Standard for Groundwater Quality. Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Zheng, J.; Guo, X.; Cai, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Gao, X.; Tan, B. Source Apportionment and Health Risks of Nitrate Pollution in Shallow Groundwater in the Agricultural Northern Xiaoxing’ an Mountains Region of China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.-L.; Zhao, Z.-Q.; Tao, F.-X.; Liu, B.-J.; Tao, Z.-H.; Gao, S.; Zhang, L.-H. Characteristics of Carbonate, Evaporite and Silicate Weathering in Huanghe River Basin: A Comparison among the Upstream, Midstream and Downstream. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2014, 96, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Yang, X.; Rioual, P.; Qin, X.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, H.; Yu, J. Hydrogeochemistry of Three Watersheds (the Erlqis, Zhungarer and Yili) in Northern Xinjiang, NW China. Appl. Geochem. 2011, 26, 1535–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, S.; Yuan, D.; Li, L.; Yao, F.; Dong, H.; Zheng, J. Evaluation of groundwater quality and source analysis of hydrochemical components in the Oujiang River Basin. Environ. Chem. 2025, 44, 1877–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, J.; Qian, H. Assessment of Groundwater Quality for Irrigation Purposes and Identification of Hydrogeochemical Evolution Mechanisms in Pengyang County, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 69, 2211–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.; Liang, Y.; Ma, R. Adsorption/Desorption Behavior of NH4-N under Surface Water-Groundwater Interaction and Its Impact on N Migration and Transformation. Earth Sci. 2024, 49, 3761–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, K.; Chen, C. Hydrochemical and Multi-Isotope Analysis of Nitrogen Sources and Transformation Processes in the Wetland-Groundwater System of Honghu Lake. Earth Sci. 2024, 49, 3946–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Over 25% Ion Content | HCO3 | HCO3·SO4 | HCO3·SO4·Cl | HCO3·Cl | SO4 | SO4·Cl | Cl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | 1 | 8 | 15 | 22 | 29 | 36 | 43 |

| Ca·Mg | 2 | 9 | 16 | 23 | 30 | 37 | 44 |

| Mg | 3 | 10 | 17 | 24 | 31 | 38 | 45 |

| Na·Ca | 4 | 11 | 18 | 25 | 32 | 39 | 46 |

| Na·Ca·Mg | 5 | 12 | 19 | 26 | 33 | 40 | 47 |

| Na·Mg | 6 | 13 | 20 | 27 | 34 | 41 | 48 |

| Na | 7 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 35 | 42 | 49 |

| Classification Level | I | II | III | IV | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EWQI value | ≤50 | 50~100 | 100~150 | 150~200 | ≥200 |

| Description | Unpolluted | Low pollution | Moderate pollution | High pollution | Significant pollution |

| Parameters | Max | Min | Mean | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation | Standard Limits * | Percentage Exceeding the Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 10.66 | 6.62 | 7.4 | 0.58 | 0.07 | 6.5~8.5 | 2.98 |

| TH | 1370.89 | 53.82 | 523.38 | 272.6 | 0.52 | 450 | 55.22 |

| TDS | 2171.71 | 70.47 | 905.29 | 498.15 | 0.55 | 1000 | 35.82 |

| Na+ | 421.95 | 1 | 103.13 | 93.29 | 0.9 | 200 | 11.94 |

| Mg2+ | 192.97 | 0.44 | 45.67 | 39.03 | 0.85 | - | - |

| Ca2+ | 332.17 | 18.09 | 134.26 | 64.03 | 0.47 | - | - |

| K+ | 138.5 | 0.1 | 8.33 | 22.97 | 2.75 | - | - |

| NH4+ | 1.55 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.3 | 2.41 | 0.64 | 7.46 |

| Cl− | 743.38 | 0.22 | 132.07 | 118.36 | 0.89 | 250 | 11.94 |

| SO42− | 1028.71 | 3.81 | 216.57 | 221.85 | 1.02 | 250 | 28.35 |

| HCO3− | 892.43 | 2.43 | 380.57 | 162.84 | 0.42 | - | - |

| CO32− | 19.13 | 0 | 0.46 | 2.71 | 5.85 | - | - |

| Hydrochemistry Type | Anion Type | Cation Type | Quantity | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HCO3 | Ca | 9 | 13.43 |

| 2 | HCO3 | Ca·Mg | 7 | 10.45 |

| 25 | HCO3·Cl | Na·Ca | 5 | 7.46 |

| 4 | HCO3 | Na·Ca | 4 | 5.97 |

| 8 | HCO3·SO4 | Ca | 4 | 5.97 |

| 22 | HCO3·Cl | Ca | 4 | 5.97 |

| 26 | HCO3·Cl | Na·Ca·Mg | 4 | 5.97 |

| 11 | HCO3·SO4 | Na·Ca | 3 | 4.48 |

| 12 | HCO3·SO4 | Na·Ca·Mg | 3 | 4.48 |

| 18 | HCO3·SO4·Cl | Na·Ca | 3 | 4.48 |

| 23 | HCO3·Cl | Ca·Mg | 3 | 4.48 |

| 9 | HCO3·SO4 | Ca·Mg | 2 | 2.99 |

| 15 | HCO3·SO4·Cl | Ca | 2 | 2.99 |

| 19 | HCO3·SO4·Cl | Na·Ca·Mg | 2 | 2.99 |

| 5 | HCO3 | Na·Ca·Mg | 1 | 1.49 |

| 13 | HCO3·SO4 | Na·Mg | 1 | 1.49 |

| 16 | HCO3·SO4·Cl | Ca·Mg | 1 | 1.49 |

| 20 | HCO3·SO4·Cl | Na·Mg | 1 | 1.49 |

| 21 | HCO3·SO4·Cl | Na | 1 | 1.49 |

| 32 | SO4 | Na·Ca | 1 | 1.49 |

| 34 | SO4 | Na·Mg | 1 | 1.49 |

| 35 | SO4 | Na | 1 | 1.49 |

| 39 | SO4·Cl | Na·Ca | 1 | 1.49 |

| 41 | SO4·Cl | Na·Mg | 1 | 1.49 |

| 42 | SO4·Cl | Na | 1 | 1.49 |

| 46 | Cl | Na·Ca | 1 | 1.49 |

| Quality Level | Quantity | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| I | 46 | 68.66 |

| II | 14 | 20.9 |

| III | 6 | 8.96 |

| IV | 1 | 1.49 |

| V | 0 | 0 |

| Parameters | P1 | P2 | P3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| TH | 0.177 | −0.148 | 0.037 |

| Na+ | 0.135 | 0.343 | −0.037 |

| Ca2+ | 0.137 | −0.268 | 0.501 |

| Mg2+ | 0.164 | 0.015 | −0.435 |

| TDS | 0.183 | 0.112 | −0.008 |

| Cl− | 0.146 | 0.048 | 0.635 |

| SO42− | 0.141 | 0.292 | −0.451 |

| HCO3− | 0.129 | −0.277 | −0.002 |

| NH4+ | −0.044 | 0.431 | 0.603 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.312 | 1.743 | 0.707 |

| Cumulative Variance Explained (%) | 59.02 | 78.38 | 86.24 |

| Sources | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | B0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TH | 16.55 | 78.27 | 4.99 | 0.18 |

| TDS | 27.69 | 64.72 | 1.19 | 6.38 |

| Na+ | 43.92 | 41.12 | 5.02 | 9.92 |

| Ca2+ | 3.2 | 86.75 | 3.38 | 6.65 |

| Mg2+ | 32.47 | 51.27 | 6.32 | 9.91 |

| NH4+ | 4.11 | 19.94 | 15.19 | 60.74 |

| Cl− | 9.95 | 61.32 | 1.5 | 27.21 |

| SO42− | 60.9 | 21.61 | 0.08 | 17.39 |

| HCO3− | 5.64 | 55.05 | 5.38 | 33.91 |

| Percentage of the total | 22.71 | 53.34 | 4.79 | 19.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, B.; Lv, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, M.; Zhang, R.; Song, C.; Shen, X.; Zhao, H. Assessment of Groundwater Environmental Quality and Analysis of the Sources of Hydrochemical Components in the Nansi Lake, China. Water 2025, 17, 3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233398

Yan B, Lv X, Wang T, Wang M, Zhang R, Song C, Shen X, Zhao H. Assessment of Groundwater Environmental Quality and Analysis of the Sources of Hydrochemical Components in the Nansi Lake, China. Water. 2025; 17(23):3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233398

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Beibei, Xiaofang Lv, Tao Wang, Min Wang, Ruilin Zhang, Chengyuan Song, Xinyi Shen, and Hengyi Zhao. 2025. "Assessment of Groundwater Environmental Quality and Analysis of the Sources of Hydrochemical Components in the Nansi Lake, China" Water 17, no. 23: 3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233398

APA StyleYan, B., Lv, X., Wang, T., Wang, M., Zhang, R., Song, C., Shen, X., & Zhao, H. (2025). Assessment of Groundwater Environmental Quality and Analysis of the Sources of Hydrochemical Components in the Nansi Lake, China. Water, 17(23), 3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233398