Reconstruction of Daily Runoff Series in Data-Scarce Areas Based on Physically Enhanced Seq-to-Seq-Attention-LSTM Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Research Status of Remote Sensing Runoff Monitoring

1.2. The Current Situation of Daily Scale Runoff Data Reconstruction

1.3. This Study

- (1)

- Building on historical runoff data, this study addresses the pathway and mechanism challenges in daily streamflow reconstruction by integrating hydrologically meaningful meteorological features—precipitation, air temperature, wind speed, sunshine duration, and relative humidity—into a deep learning framework.

- (2)

- A physics-enhanced PSAL model was developed by integrating Physics-enhanced principles, the S2S-LSTM [28], and a multi-dimensional attention mechanism (temporal- and feature-level attention). The model aims to improve streamflow prediction under sparse and incomplete remote sensing data conditions. By combining data structures derived from physical mechanisms with data-driven approaches, it enhances the generalizability and transferability of data-driven models.

- (3)

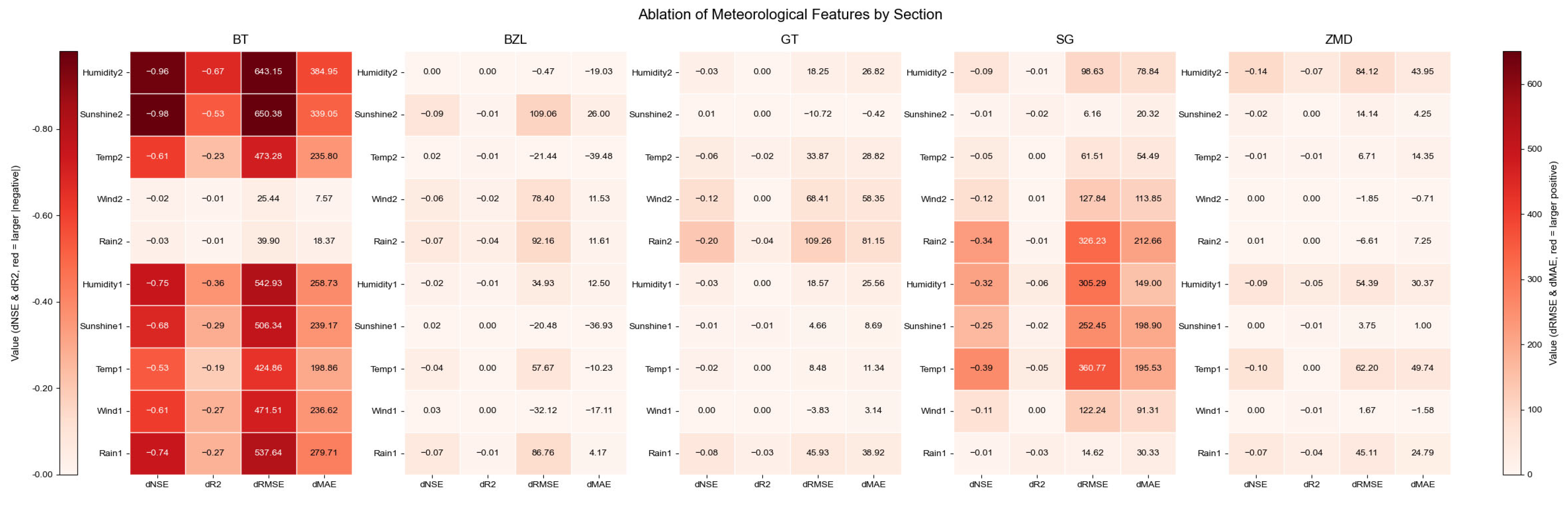

- Daily-scale reconstruction experiments demonstrate strong applicability and performance superior to conventional deep learning baselines. While retaining the flexibility of data-driven modeling, the framework embeds hydrophysical mechanism features, offering a new route for RS-dominated reconstruction of sparse daily discharge data. Feature ablation shows that precipitation, as the dominant driver, strengthens reconstruction skill (ΔNSE = 0.32), whereas temperature, humidity, wind speed, and sunshine exhibit pronounced spatially heterogeneous contributions, indicating good interpretability and consistent variable responses.

2. Case Study

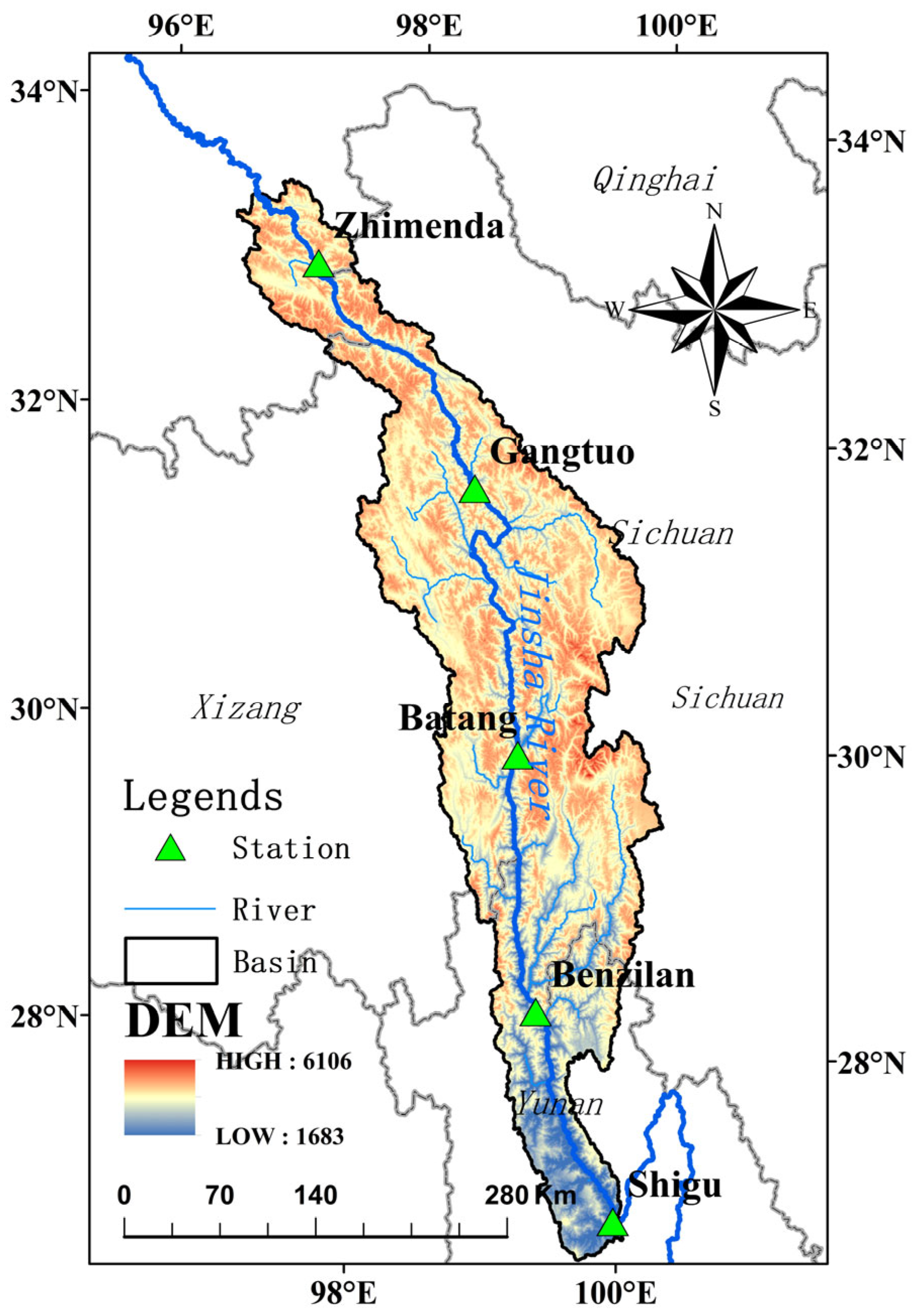

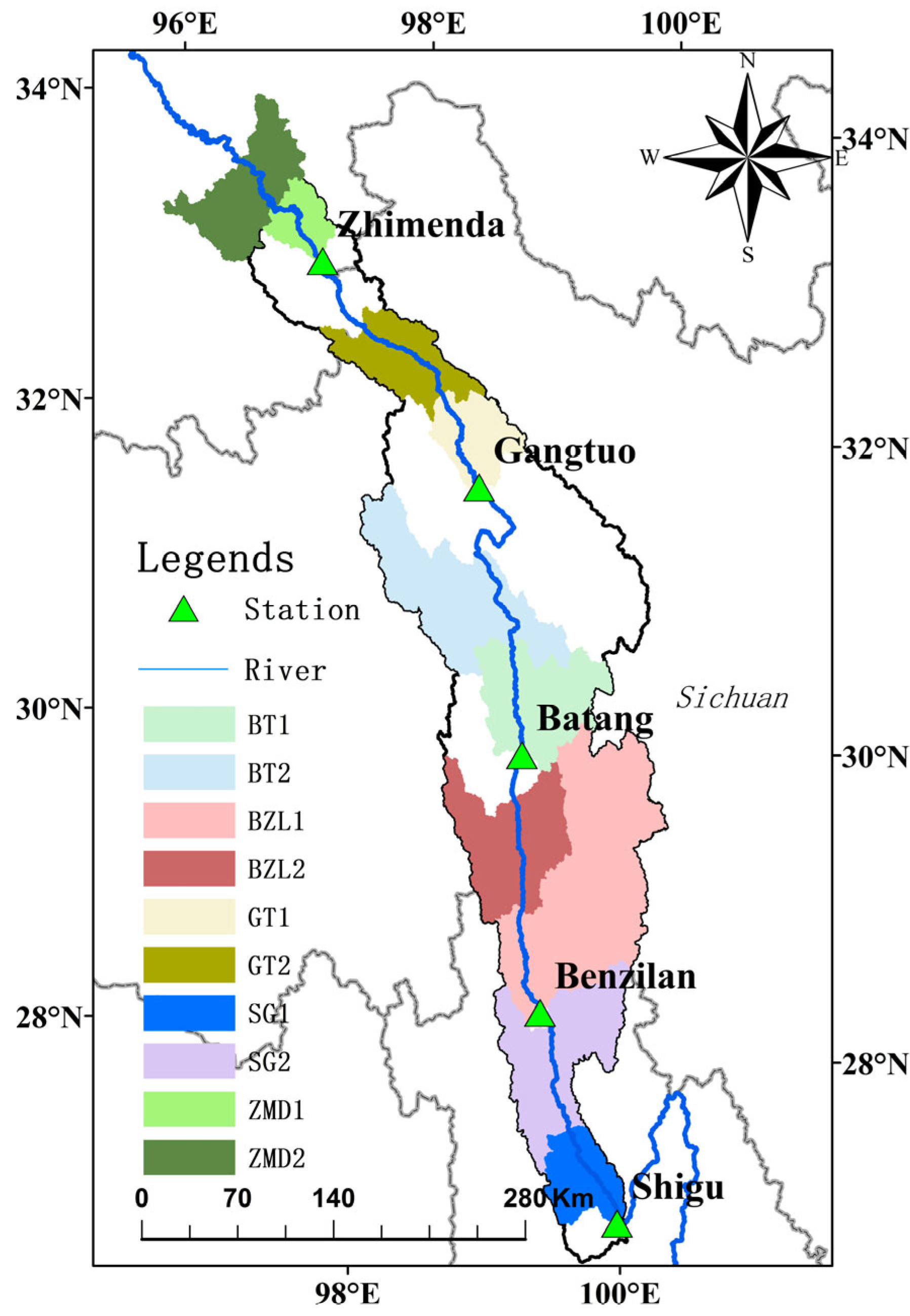

2.1. Overview of the Research Area

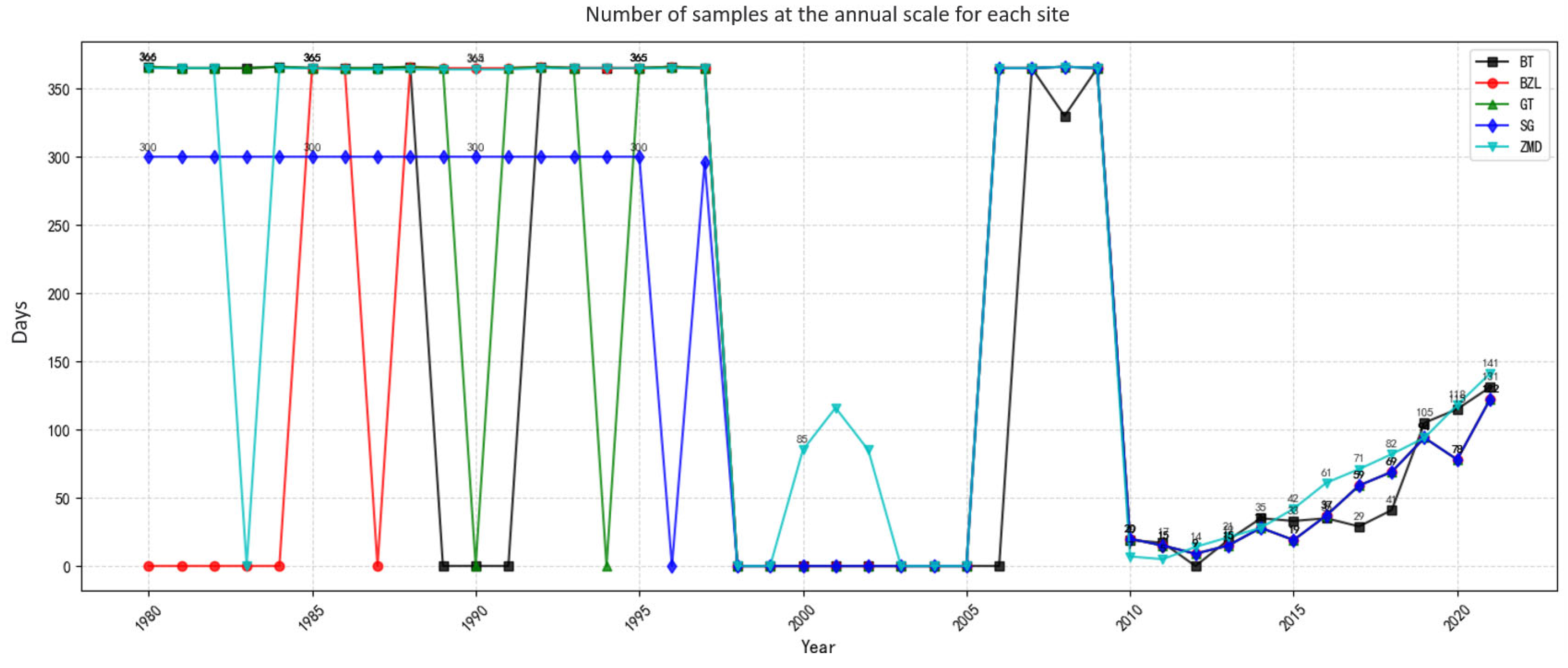

2.2. Research Data Source

- (1)

- Hydrologic Data

- (2)

- Meteorological and Other Environmental Element Data

- (3)

- Topographic Data

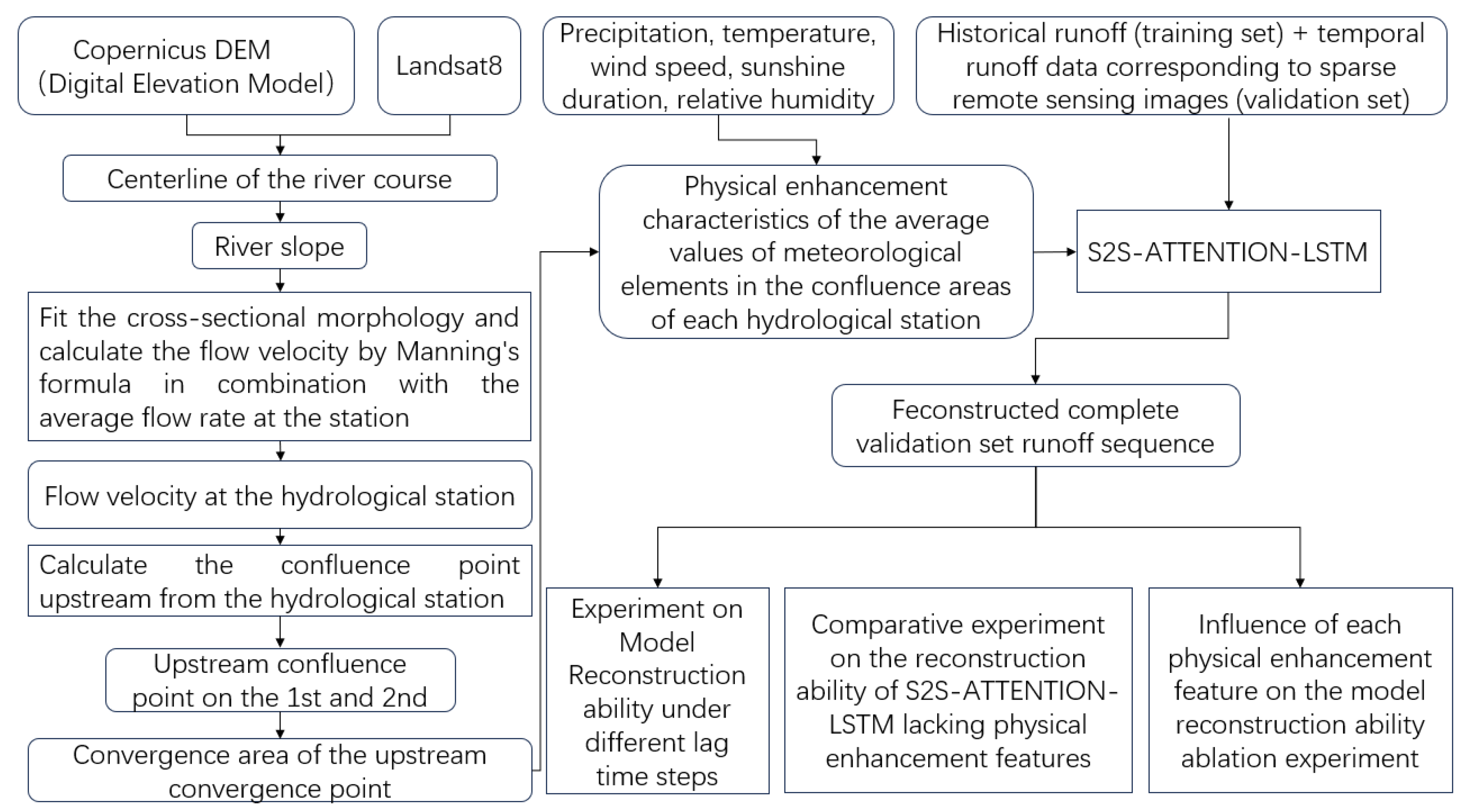

3. Methodology

3.1. Principles of the Model

3.2. Method

3.3. Model Structure

3.3.1. Physics-Enhanced

3.3.2. S2S-Attention-LSTM

3.4. Evaluation Index

4. Results and Evaluation

4.1. Data and Model Feature Analysis

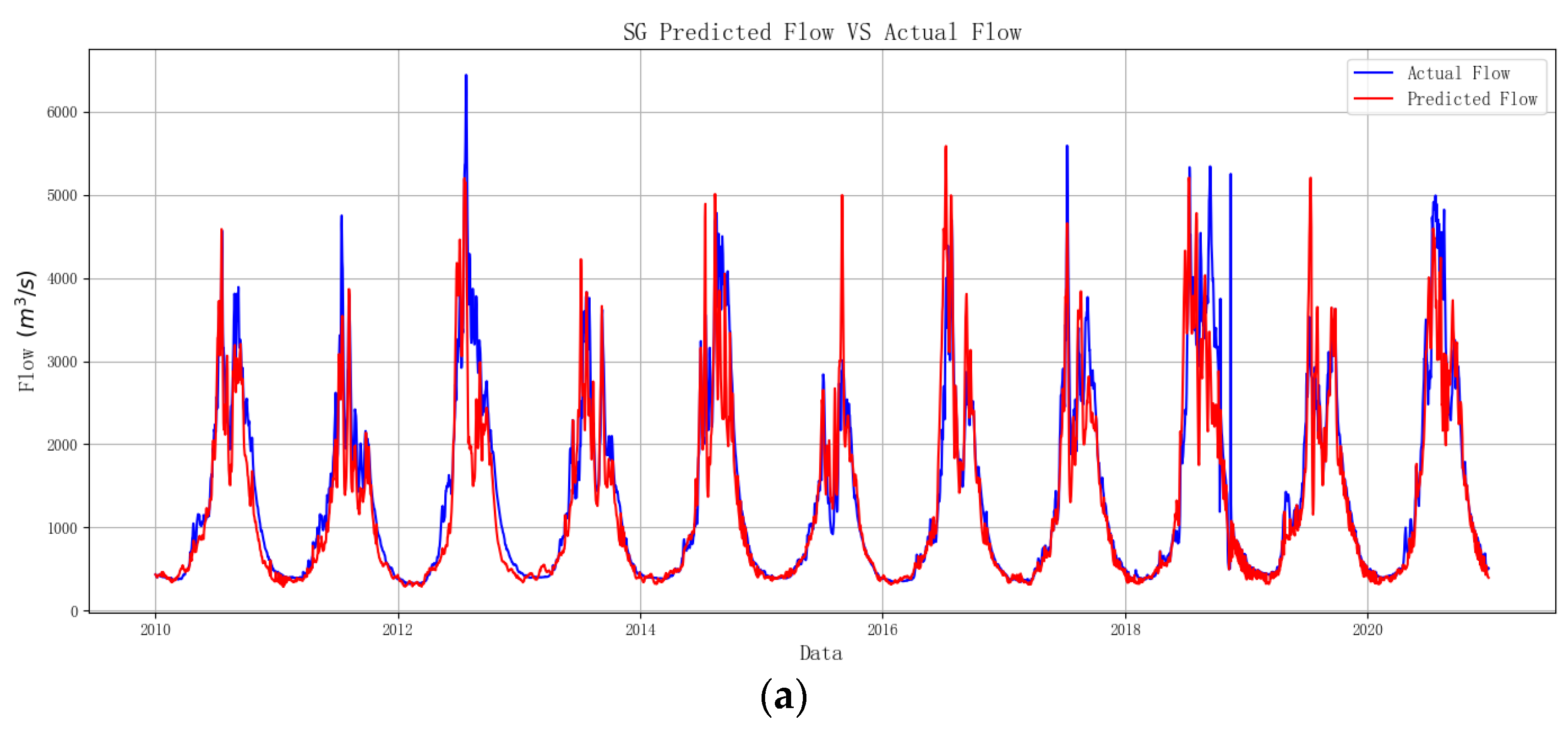

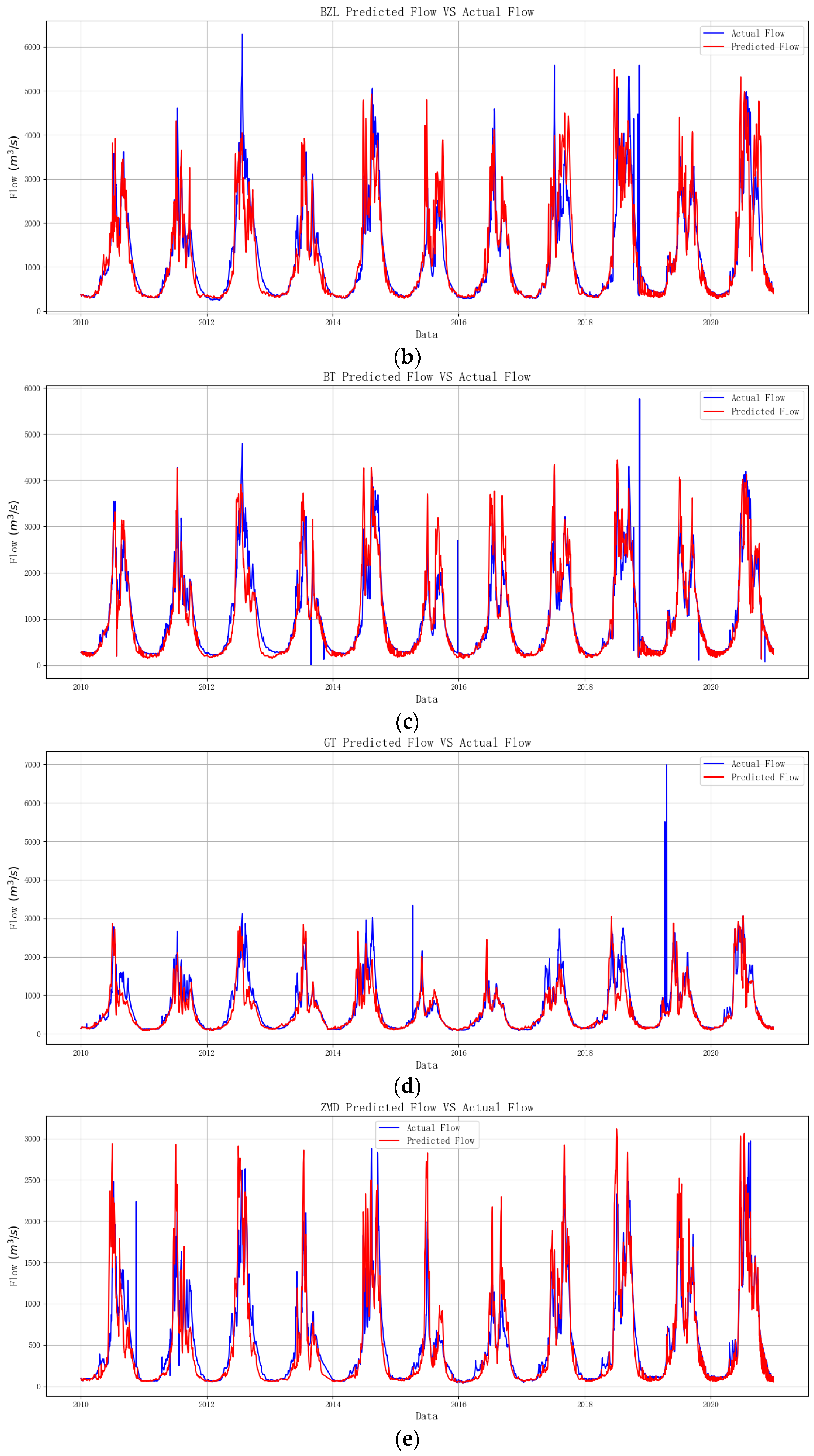

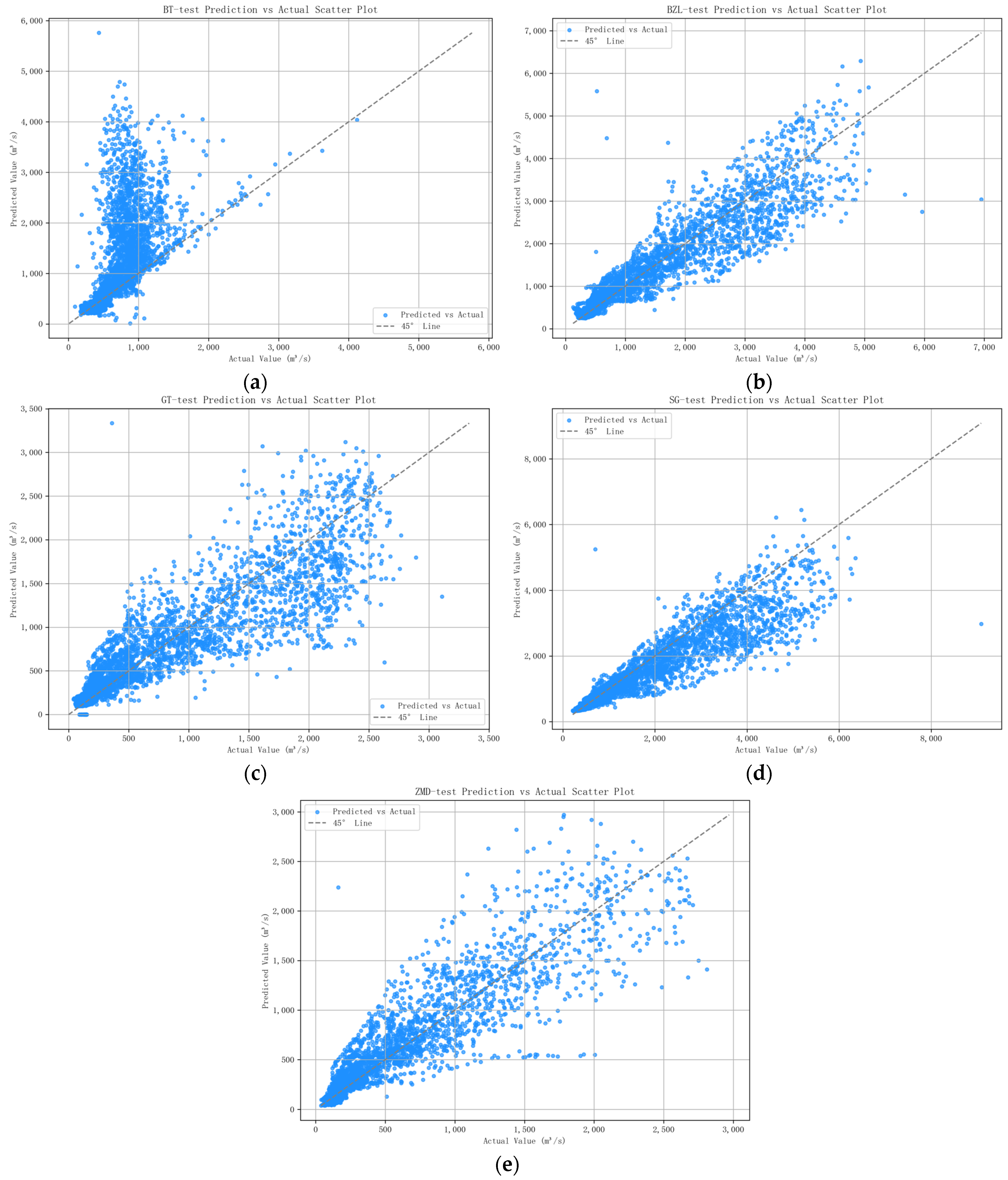

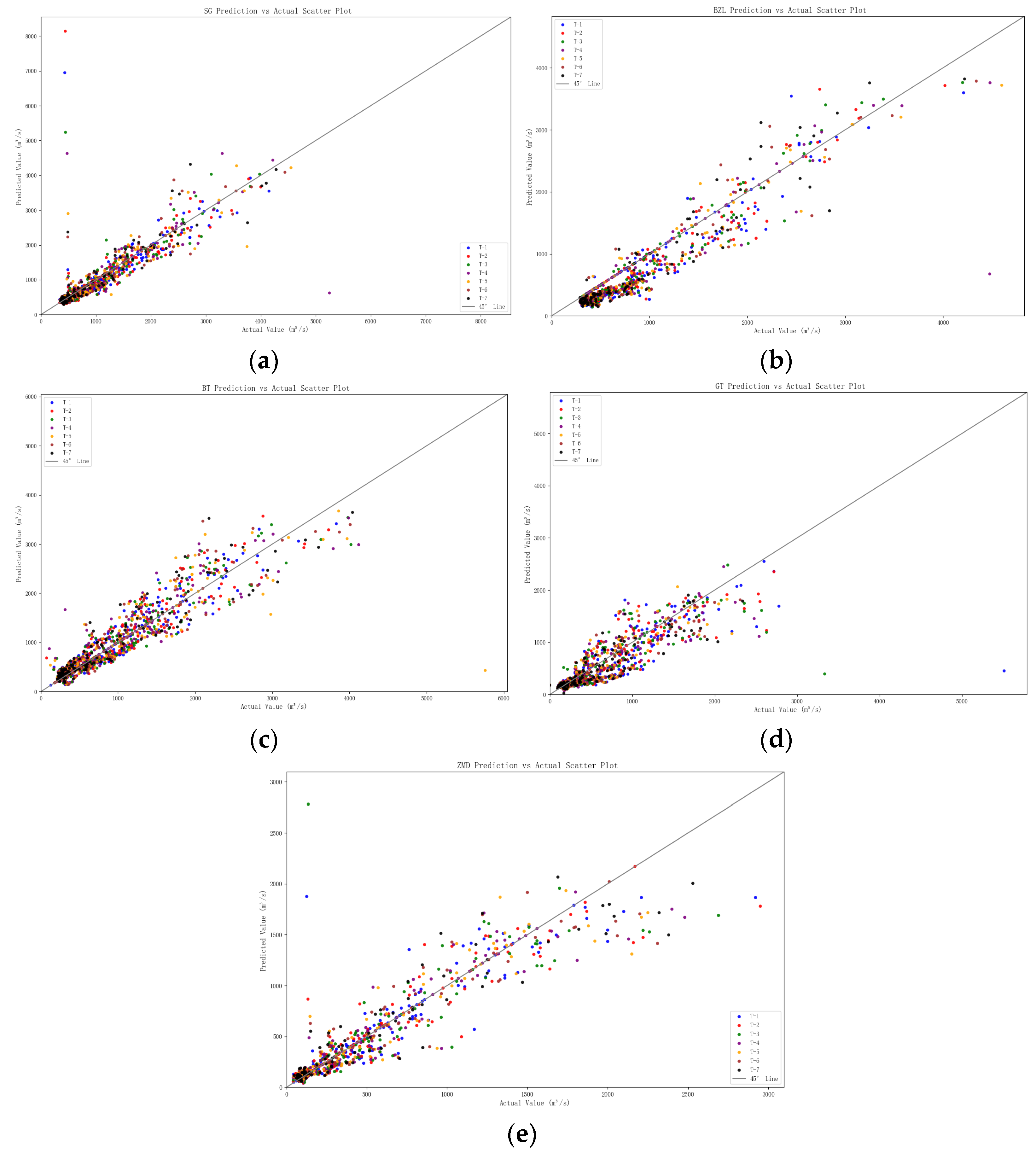

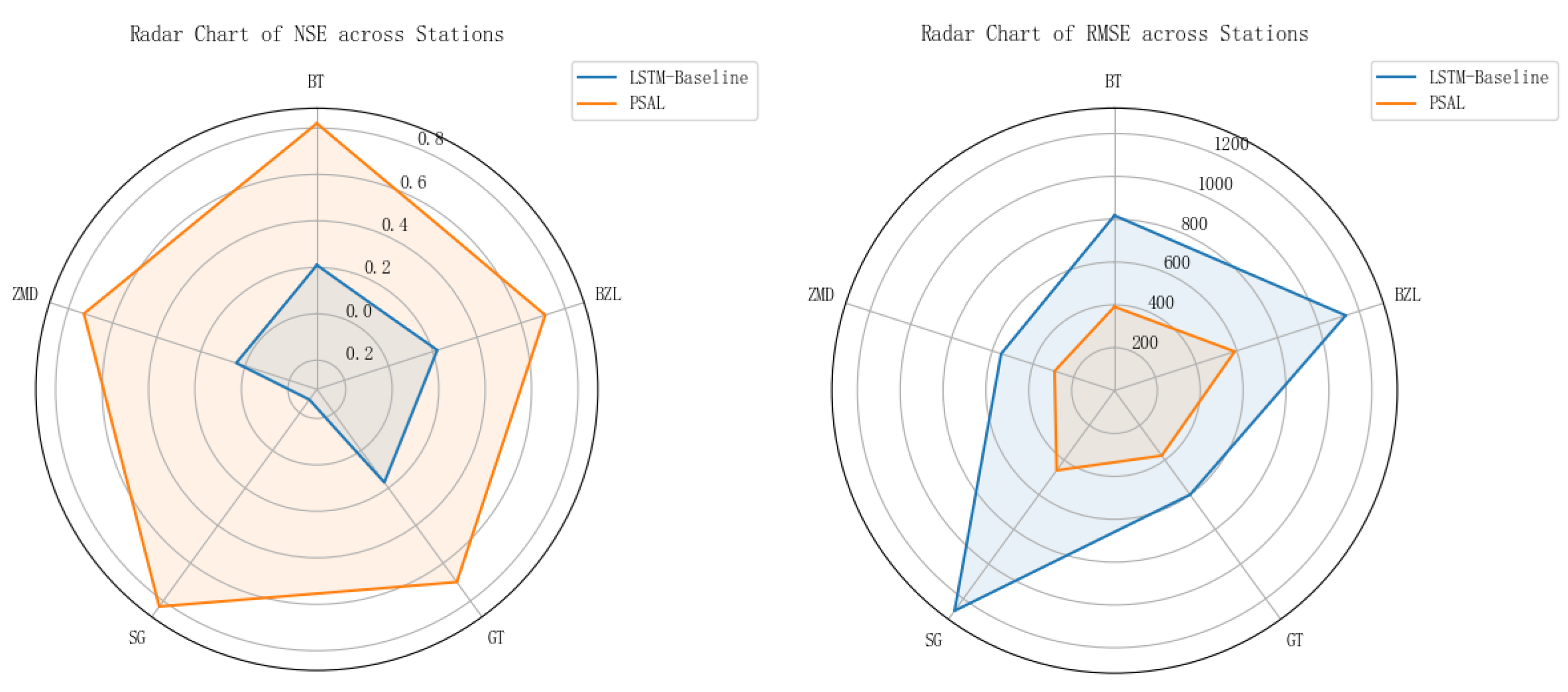

4.2. Evaluation of Model Simulation Results

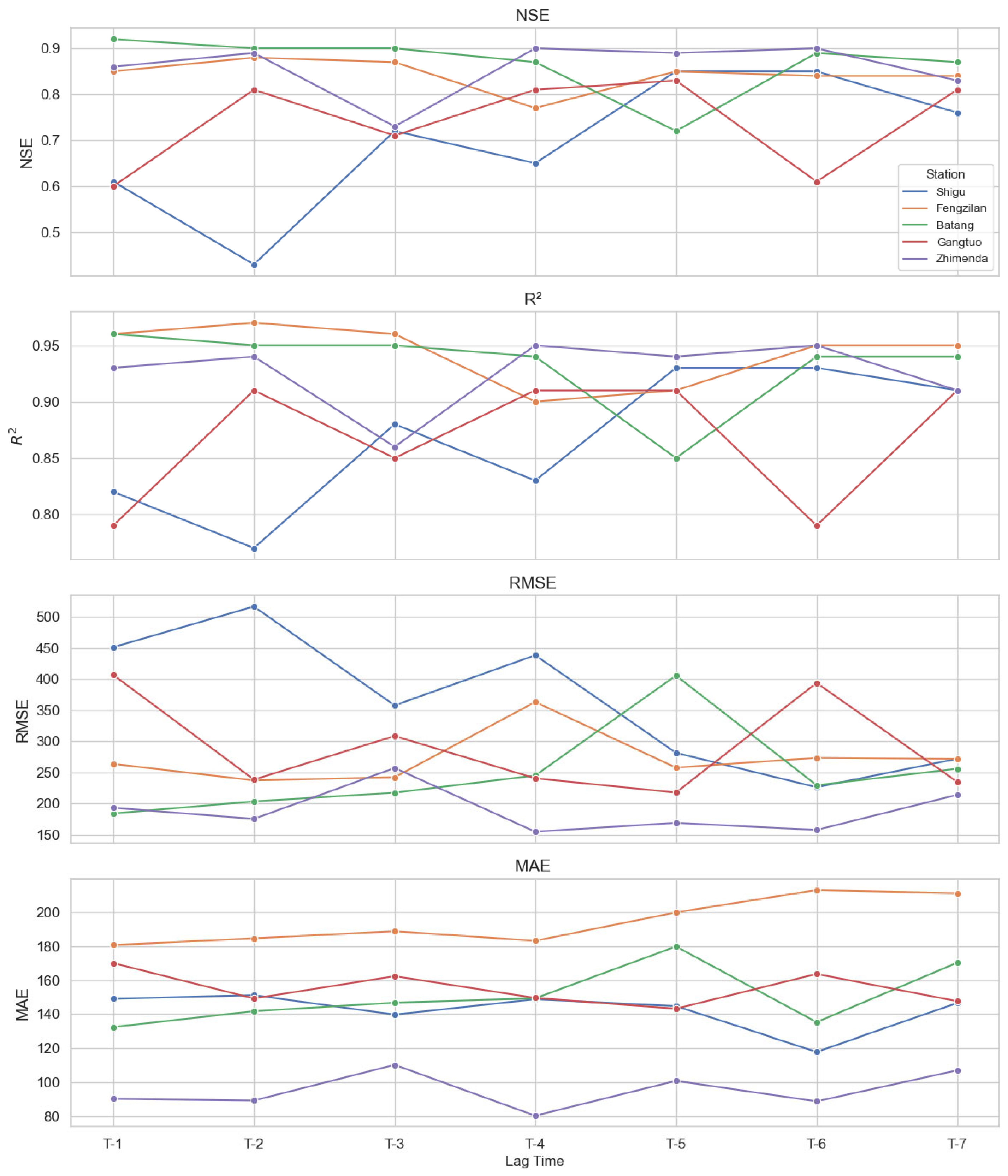

4.3. The Influence of Lag Time Step Size on Refactoring Capability

4.4. Ablation Experiment: Results and Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Relationship Between Model Performance and Hydrologic Response Mechanisms

5.2. Importance and Contribution of Physics-Enhanced Inputs

5.3. Comparison with Existing Studies and Innovations

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The model demonstrated strong overall performance, with an average NSE of 0.81 and R2 of 0.91 on the test set, significantly outperforming the baseline LSTM model without physical features. It also showed good accuracy in capturing extreme flow events, confirming the critical role of the physics-enhanced mechanism in improving prediction accuracy. Precipitation was identified as the most important driving factor, while other meteorological variables—such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and sunshine duration—showed station-specific impacts on model performance, reflecting the spatial heterogeneity of regional hydrological responses.

- (2)

- The contributing-area meteorological averaging not only boosts performance but also, in physical terms, approximates the “subbasin delineation + runoff–routing” mechanism of traditional hydrologic models, enabling data-driven modeling to retain high physical consistency and generalization even without a full physical structure.

- (3)

- Lag-step experiments indicate better performance at the T-7 setting. Differences in the optimal lag across stations reveal complex influences of underlying-surface heterogeneity on runoff generation and travel times.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, Q.; Gao, H.; Lu, H.; Lettenmaier, D.P. Remote Sensing: Hydrology. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2009, 33, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yaari, A.; Juszczak, R. Challenges and Limitations of Remote Sensing Applications in Northern Peatlands: Present and Future Prospects. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, A.M.; Mao, F.; Mendes, T.S.G.; Simões, S.J.C.; Balestieri, J.A.P.; Hannah, D.M. Estimation of River Flow Using CubeSats Remote Sensing. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 788, 147762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettenmaier, D.P.; Alsdorf, D.; Dozier, J.; Huffman, G.J.; Pan, M.; Wood, E.F. Inroads of Remote Sensing into Hydrologic Science during the WRR Era. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 7309–7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.R. China’s High-Resolution Earth Observation System (CHEOS): Advances and Perspectives. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 3, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notti, D.; Giordan, D.; Caló, F.; Pepe, A.; Zucca, F.; Galve, J.P. Potential and Limitations of Open Satellite Data for Flood Mapping. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adıyaman, H.; Varul, Y.E.; Bakırman, T. Stripe Error Correction for Landsat-7 Using Deep Learning. PFG–J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Geoinf. Sci. 2025, 93, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojević, B.; Mihailović, V.; Bogojević, A.; Plavšić, J. Detecting Annual and Seasonal Hydrological Change Using Marginal Distributions of Daily Flows. Water 2023, 15, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Zhang, G.; Hou, J.; Xie, J.; Lv, M.; Liu, F. Hybrid Forecasting Model for Non-Stationary Daily Runoff Series: A Case Study in the Han River Basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2019, 577, 123915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ri, T.; Jiang, J.; Sivakumar, B.; Pang, T. A Statistical–Distributed Model of Average Annual Runoff for Water Resources Assessment in DPR Korea. Water 2019, 11, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swagatika, S.; Paula, J.C.; Sahoo, B.B.; Gupta, S.K.; Singh, P.K. Improving the Forecasting Accuracy of Monthly Runoff Time Series of the Brahmani River in India Using a Hybrid Deep Learning Model. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Fu, C.; Yang, M. Integrating Hourly Scale Hydrological Modeling and Remote Sensing Data for Flood Simulation and Hydrological Analysis in a Coastal Watershed. Water 2023, 13, 10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, H.S.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, L. Prospects for Reconstructing Daily Runoff from Individual Upstream Remotely-Sensed Climatic Variables. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoko, G.; Le, T.H.; Gomi, T.; Kato, T. A Review of SWAT Model Application in Africa. Water 2021, 13, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zeng, S.; Liu, J.; Tang, Z.; Hua, X.; Li, Z.; Song, J.; Xia, J. Mid- to Long-Term Runoff Prediction Based on Deep Learning at Different Time Scales in the Upper Yangtze River Basin. Water 2022, 14, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.-M.; Hu, X.-X.; Wang, W.-C.; Chau, K.-W.; Zang, H.-F.; Wang, J. A New Hybrid Model for Monthly Runoff Prediction Using ELMAN Neural Network Based on Decomposition-Integration Structure with Local Error Correction Method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzert, F.; Klotz, D.; Brenner, C.; Schulz, K.; Herrnegger, M. Rainfall–Runoff Modelling Using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 6005–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Shao, H.; Hu, D.; Dai, X.; Wu, S. Runoff Simulation Modeling Method Integrating Spatial Element Dynamics and Neural Network for Remote Sensing Precipitation Data. J. Hydrol. 2024, 642, 131875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, H.M.V.V.; Chadalawada, J.; Babovic, V. Hydrologically Informed Machine Learning for Rainfall–Runoff Modelling: Towards Distributed Modelling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 4373–4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baste, S.; Klotz, D.; Acuña Espinoza, E.; Bardossy, A.; Loritz, R. Unveiling the Limits of Deep Learning Models in Hydrological Extrapolation Tasks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 29, 5871–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Dong, G.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Jia, D. Runoff Estimation in the Upper Reaches of the Heihe River Using an LSTM Model with Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbrand, K.; Taormina, R.; ten Veldhuis, M.-C.; Visser, M.; Hrachowitz, M.; Nuttall, J.; Dahm, R. Predicting Streamflow with LSTM Networks Using Global Datasets. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1166124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-Informed Machine Learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zwart, J.A.; Sadler, J.M.; Appling, A.; Oliver, S.K.; Markstrom, S.; Willard, J.; Read, J.S.; Karpatne, A.; Kumar, V. Physics-Guided Recurrent Graph Model for Predicting Flow and Temperature in River Networks. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2022, 44, C612–C620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawsar, P.; Vagadiya, J.; Bhatia, U. Enhancing predictive skills in physically-consistent way: Physics informed machine learning for hydrological processes. J. Hydrol. 2022, 614, 128618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Beck, H.; Lawson, K.; Shen, C. The suitability of differentiable, physics-informed machine learning hydrologic models for ungauged regions and climate change impact assessment. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 2357–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindas, T.; Tsai, W.-P.; Liu, J.; Rahmani, F.; Feng, D.; Bian, Y.; Lawson, K.; Shen, C. Improving river routing using a differentiable Muskingum-Cunge model and physics-informed machine learning. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, R.; Jin, J. Rainfall-Runoff Modeling Using LSTM-Based Multi-State-Vector Sequence-to-Sequence Model. J. Hydrol. 2021, 602, 126378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafian, B.; Julien, P.Y.; Rajaie, H. Runoff Hydrograph Simulation Based on Time Variable Isochrone Technique. J. Hydrol. 2002, 261, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J.; Han, D.; Wang, G.; Shen, C. Physics-Guided Deep Learning for Rainfall-Runoff Modeling by Considering Extreme Events and Monotonic Relationships. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeghalmy, S.; Fazekas, A. A Comparative Study of the Use of Stratified Cross-Validation and Distribution-Balanced Stratified Cross-Validation in Imbalanced Learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, A.; Xu, S.; Li, X.; Jia, X.; Stienbach, M.; Duffy, C.; Nieber, J.; Kumar, V. Physics Guided Machine Learning Methods for Hydrology. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.02854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Shi, Y.; Bamber, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Chen, G. Physics-Aware Machine Learning Revolutionizes Scientific Paradigm for Machine Learning and Process-Based Hydrology. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.05227. [Google Scholar]

- Autodesk Inc. AutoCAD 2022, version S.51.0.0. [Computer Software]. Autodesk Inc.: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.autodesk.com/products/autocad/overview (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Song, S.; Schmalz, B.; Zhang, J.X.; Li, G.; Fohrer, N. Application of modified Manning formula in the determination of vertical profile velocity in natural rivers. Hydrol. Res. 2017, 48, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigon, R.; Bertoldi, G.; Over, T.M. GEOtop: A Distributed Hydrological Model with Coupled Water and Energy Budgets. J. Hydrometeorol. 2006, 7, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, R.; Fortin, J.-P.; Rousseau, A.N.; Massicotte, S.; Villeneuve, J.-P. Determination of the Drainage Structure of a Watershed Using a Digital Elevation Model and a Digital River and Lake Network. J. Hydrol. 2001, 240, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, X. Urban water demand prediction based on attention mechanism graph convolutional network-long short-term memory. Water 2024, 16, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Zou, Q.; Ye, L.; Zhu, S.; Li, X.; Yang, H. Study on Optimization and Combination Strategy of Multiple Daily Runoff Prediction Models Coupled with Physical Mechanism and LSTM. J. Hydrol. 2023, 624, 129969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Han, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M.; Lin, Q. Short-Term Runoff Prediction with GRU and LSTM Networks without Requiring Time Step Optimization during Sample Generation. J. Hydrol. 2020, 589, 125188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siami-Namini, S.; Tavakoli, N.; Namin, A.S. A Comparison of ARIMA and LSTM in Forecasting Time Series. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Orlando, FL, USA, 17–20 December 2018; pp. 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Guo, J. Bidirectional LSTM with Attention Mechanism and Convolutional Layer for Text Classification. Neurocomputing 2019, 337, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Kong, D.; Han, H.; Zhao, Y. EA-LSTM: Evolutionary Attention-Based LSTM for Time Series Prediction. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2019, 181, 104785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Xu, F.; Lin, F.; Wang, F. A Hydrological Data Prediction Model Based on LSTM with Attention Mechanism. Water 2023, 15, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wei, J.; Xie, B.; Shi, Z.; Wang, H.; Tian, X.; He, B.; Peng, Q. Experimental and numerical investigation on H2-fueled thermophotovoltaic micro tube with multi-cavity. Energy 2023, 274, 127325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A Review of Recurrent Neural Networks: LSTM Cells and Network Architectures. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefenon, S.F.; Seman, L.O.; Aquino, L.S.; dos Santos Coelho, L. Wavelet-Seq2Seq-LSTM with attention for time series forecasting of level of dams in hydroelectric power plants. Energy 2023, 274, 127350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input Data | Streamflow Data | Precipitation | Temperature | Wind Speed | Sunshine Duration | Relative Humidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Input Days | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of Output Streamflow Days | 1 | \ | ||||

| Modeling Approach | Multistep Forecasting | |||||

| Simulation Lag Time | Changes in dates with missing remote sensing data | |||||

| Hyperparameters in Stefenon et al., 2023 [47] | Hyperparameters in This Study | |

|---|---|---|

| Input Length | 24 h | 7 day |

| Loss Function | MSE | MSE |

| Optimized | ADAM | ADAM |

| Learning Rate | 0.001 | 0.0005 |

| Epochs | 100 | 10 |

| Batch Size | / | 32 |

| Cross-Section | Dataset | NSE | R2 | NRMSE | RelMAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | Training set | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Testing set | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.07 | 0.20 | |

| BZL | Training set | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Testing set | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 0.20 | |

| BT | Training set | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Testing set | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.21 | 0.72 | |

| GT | Training set | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Testing set | 0.71 | 0.85 | 0.13 | 0.28 | |

| ZMD | Training set | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Testing set | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.08 | 0.26 |

| LSTM-BASELINE | NSE | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT | 0.21 | 0.67 | 817.32 | 431.07 |

| BZL | 0.22 | 0.57 | 1134.12 | 778.44 |

| GT | 0.17 | 0.62 | 599.73 | 359.91 |

| SG | −0.27 | 0.46 | 1270.08 | 763.11 |

| ZMD | 0.04 | 0.56 | 555.95 | 386.51 |

| Cross-Section | Removed Feature | NSE | ΔNSE | R2 | ΔR2 | RMSE | ΔRMSE | MAE | ΔMAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT | / | 0.89 | 0 | 0.94 | 0 | 308.76 | 0 | 192.12 | 0 |

| Precipitation_1 | 0.15 | −0.74 | 0.67 | −0.27 | 846.4 | 537.64 | 471.83 | 279.71 | |

| Wind_1 | 0.28 | −0.61 | 0.67 | −0.27 | 780.27 | 471.51 | 428.74 | 236.62 | |

| Temperature_1 | 0.36 | −0.53 | 0.75 | −0.19 | 733.62 | 424.86 | 390.98 | 198.86 | |

| Sunshine_1 | 0.21 | −0.68 | 0.65 | −0.29 | 815.1 | 506.34 | 431.29 | 239.17 | |

| Humidity_1 | 0.14 | −0.75 | 0.58 | −0.36 | 851.69 | 542.93 | 450.85 | 258.73 | |

| Precipitation_2 | 0.86 | −0.03 | 0.93 | −0.01 | 348.66 | 39.9 | 210.49 | 18.37 | |

| Wind_2 | 0.87 | −0.02 | 0.93 | −0.01 | 334.2 | 25.44 | 199.69 | 7.57 | |

| Temperature_2 | 0.28 | −0.61 | 0.71 | −0.23 | 782.04 | 473.28 | 427.92 | 235.8 | |

| Sunshine_2 | −0.09 | −0.98 | 0.41 | −0.53 | 959.14 | 650.38 | 531.17 | 339.05 | |

| Humidity_2 | −0.07 | −0.96 | 0.27 | −0.67 | 951.91 | 643.15 | 577.07 | 384.95 | |

| BZL | / | 0.83 | 0 | 0.93 | 0 | 443.24 | 0 | 288.44 | 0 |

| Precipitation_1 | 0.76 | −0.07 | 0.92 | −0.01 | 530 | 86.76 | 292.61 | 4.17 | |

| Wind_1 | 0.86 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0 | 411.12 | −32.12 | 271.33 | −17.11 | |

| Temperature_1 | 0.79 | −0.04 | 0.93 | 0 | 500.91 | 57.67 | 278.21 | −10.23 | |

| Sunshine_1 | 0.85 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0 | 422.76 | −20.48 | 251.51 | −36.93 | |

| Humidity_1 | 0.81 | −0.02 | 0.92 | −0.01 | 478.17 | 34.93 | 300.94 | 12.5 | |

| Precipitation_2 | 0.76 | −0.07 | 0.89 | −0.04 | 535.4 | 92.16 | 300.05 | 11.61 | |

| Wind_2 | 0.77 | −0.06 | 0.91 | −0.02 | 521.64 | 78.4 | 299.97 | 11.53 | |

| Temperature_2 | 0.85 | 0.02 | 0.92 | −0.01 | 421.8 | −21.44 | 248.96 | −39.48 | |

| Sunshine_2 | 0.74 | −0.09 | 0.92 | −0.01 | 552.3 | 109.06 | 314.44 | 26 | |

| Humidity_2 | 0.83 | 0 | 0.93 | 0 | 442.77 | −0.47 | 269.41 | −19.03 | |

| GT | / | 0.71 | 0 | 0.85 | 0 | 371.17 | 0 | 185.22 | 0 |

| Precipitation_1 | 0.63 | −0.08 | 0.82 | −0.03 | 417.1 | 45.93 | 224.14 | 38.92 | |

| Wind_1 | 0.71 | 0 | 0.85 | 0 | 367.34 | −3.83 | 188.36 | 3.14 | |

| Temperature_1 | 0.69 | −0.02 | 0.85 | 0 | 379.65 | 8.48 | 196.56 | 11.34 | |

| Sunshine_1 | 0.7 | −0.01 | 0.84 | −0.01 | 375.83 | 4.66 | 193.91 | 8.69 | |

| Humidity_1 | 0.68 | −0.03 | 0.85 | 0 | 389.74 | 18.57 | 210.78 | 25.56 | |

| Precipitation_2 | 0.51 | −0.2 | 0.81 | −0.04 | 480.43 | 109.26 | 266.37 | 81.15 | |

| Wind_2 | 0.59 | −0.12 | 0.85 | 0 | 439.58 | 68.41 | 243.57 | 58.35 | |

| Temperature_2 | 0.65 | −0.06 | 0.83 | −0.02 | 405.04 | 33.87 | 214.04 | 28.82 | |

| Sunshine_2 | 0.72 | 0.01 | 0.85 | 0 | 360.45 | −10.72 | 184.8 | −0.42 | |

| Humidity_2 | 0.68 | −0.03 | 0.85 | 0 | 389.42 | 18.25 | 212.04 | 26.82 | |

| SG | / | 0.8 | 0 | 0.92 | 0 | 506.32 | 0 | 267.83 | 0 |

| Precipitation_1 | 0.79 | −0.01 | 0.89 | −0.03 | 520.94 | 14.62 | 298.16 | 30.33 | |

| Wind_1 | 0.69 | −0.11 | 0.92 | 0 | 628.56 | 122.24 | 359.14 | 91.31 | |

| Temperature_1 | 0.41 | −0.39 | 0.87 | −0.05 | 867.09 | 360.77 | 463.36 | 195.53 | |

| Sunshine_1 | 0.55 | −0.25 | 0.9 | −0.02 | 758.77 | 252.45 | 466.73 | 198.9 | |

| Humidity_1 | 0.48 | −0.32 | 0.86 | −0.06 | 811.61 | 305.29 | 416.83 | 149 | |

| Precipitation_2 | 0.46 | −0.34 | 0.91 | −0.01 | 832.55 | 326.23 | 480.49 | 212.66 | |

| Wind_2 | 0.68 | −0.12 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 634.16 | 127.84 | 381.68 | 113.85 | |

| Temperature_2 | 0.75 | −0.05 | 0.92 | 0 | 567.83 | 61.51 | 322.32 | 54.49 | |

| Sunshine_2 | 0.79 | −0.01 | 0.9 | −0.02 | 512.48 | 6.16 | 288.15 | 20.32 | |

| Humidity_2 | 0.71 | −0.09 | 0.91 | −0.01 | 604.95 | 98.63 | 346.67 | 78.84 | |

| ZMD | / | 0.83 | 0 | 0.92 | 0 | 232.69 | 0 | 132.59 | 0 |

| Precipitation_1 | 0.76 | −0.07 | 0.88 | −0.04 | 277.8 | 45.11 | 157.38 | 24.79 | |

| Wind_1 | 0.83 | 0 | 0.91 | −0.01 | 234.36 | 1.67 | 131.01 | −1.58 | |

| Temperature_1 | 0.73 | −0.1 | 0.92 | 0 | 294.89 | 62.2 | 182.33 | 49.74 | |

| Sunshine_1 | 0.83 | 0 | 0.91 | −0.01 | 236.44 | 3.75 | 133.59 | 1 | |

| Humidity_1 | 0.74 | −0.09 | 0.87 | −0.05 | 287.08 | 54.39 | 162.96 | 30.37 | |

| Precipitation_2 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0 | 226.08 | −6.61 | 139.84 | 7.25 | |

| Wind_2 | 0.83 | 0 | 0.92 | 0 | 230.84 | −1.85 | 131.88 | −0.71 | |

| Temperature_2 | 0.82 | −0.01 | 0.91 | −0.01 | 239.4 | 6.71 | 146.94 | 14.35 | |

| Sunshine_2 | 0.81 | −0.02 | 0.92 | 0 | 246.83 | 14.14 | 136.84 | 4.25 | |

| Humidity_2 | 0.69 | −0.14 | 0.85 | −0.07 | 316.81 | 84.12 | 176.54 | 43.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, Z.; Xu, T.; Ye, H.; Wang, L.; Liang, L. Reconstruction of Daily Runoff Series in Data-Scarce Areas Based on Physically Enhanced Seq-to-Seq-Attention-LSTM Model. Water 2025, 17, 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233396

Yin Z, Xu T, Ye H, Wang L, Liang L. Reconstruction of Daily Runoff Series in Data-Scarce Areas Based on Physically Enhanced Seq-to-Seq-Attention-LSTM Model. Water. 2025; 17(23):3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233396

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Zhaokai, Tao Xu, Huiqiang Ye, Lin Wang, and Lili Liang. 2025. "Reconstruction of Daily Runoff Series in Data-Scarce Areas Based on Physically Enhanced Seq-to-Seq-Attention-LSTM Model" Water 17, no. 23: 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233396

APA StyleYin, Z., Xu, T., Ye, H., Wang, L., & Liang, L. (2025). Reconstruction of Daily Runoff Series in Data-Scarce Areas Based on Physically Enhanced Seq-to-Seq-Attention-LSTM Model. Water, 17(23), 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233396