Physiological and Productive Characteristics of Castanea sativa Mill. Under Irrigation Regimes in Mediterranean Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Orchard

2.2. Treatments and Experimental Design

2.3. Climatic Measurements

2.4. Plant Measurements

2.5. Nut Measurements

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

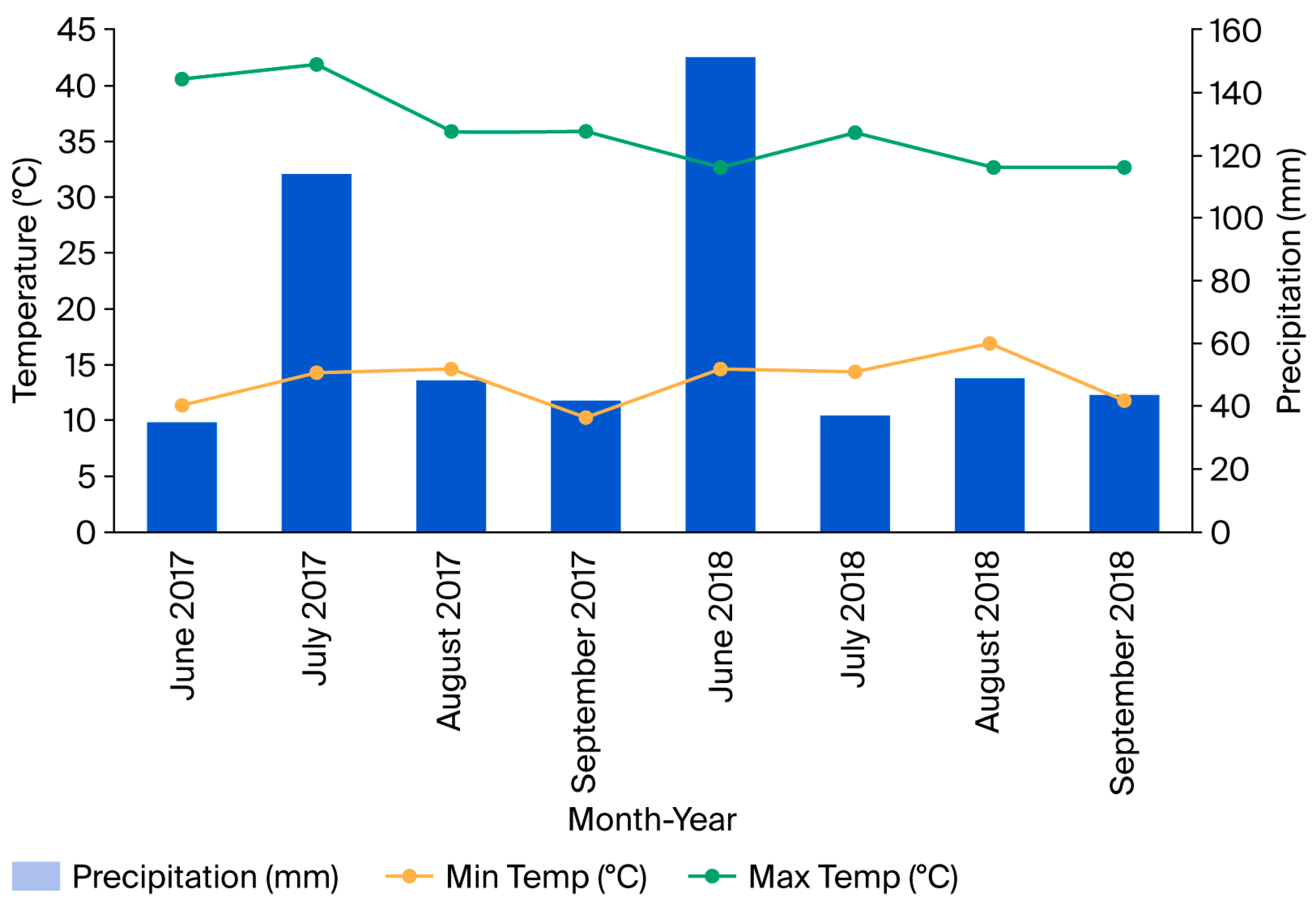

3.1. Climatic Conditions

3.2. Leaf Physiological Parameters

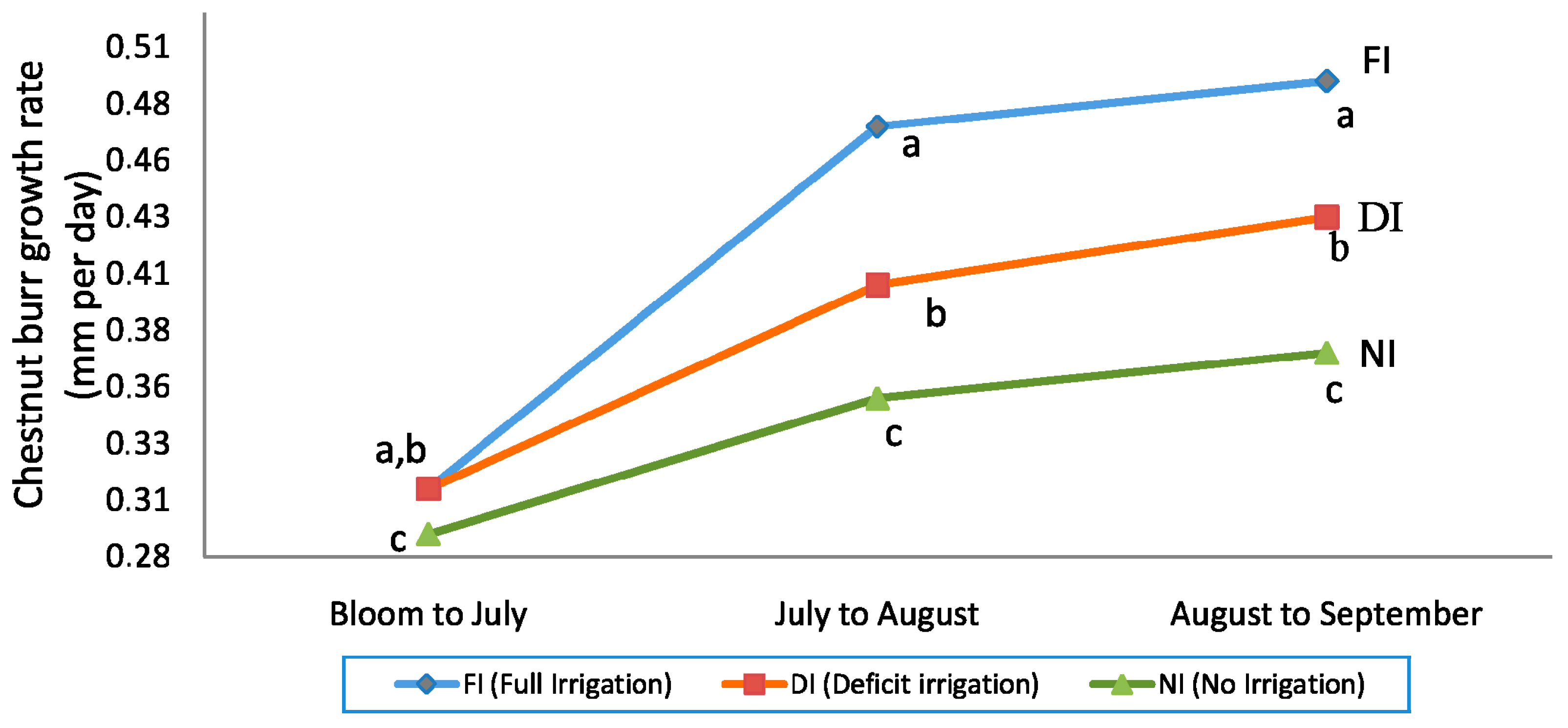

3.3. Fruit Set, Burr Growth Rate per Day, and Nut Yield

3.4. Nut Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaves, M.M.; Pereira, J.S.; Marôco, J.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Ricardo, C.P.P.; Osório, M.L.; Carvalho, I.; Faria, T.; Pinheiro, C. How Plants Cope with Water Stress in the Field. Photosynthesis and Growth. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Releases |FAO| Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Statistics. Available online: https://www.fao.org/statistics/data-releases/en (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Mota, M.; Pinto, T.; Marques, T.; Borges, A.; Caço, J.; Veiga, V.; Raimundo, F.; Gomes-Laranjo, J. Monitorizar Para Regar: O Caso Do Castanheiro (Castanea sativa). Rev. Ciências Agrárias 2017, 40, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, M.; Pinto, T.; Marques, T.; Borges, A.; Raimundo, F.; Veiga, V.; Gomes-Laranjo, J. Efeito Da Rega Na Produtividade Fotossintética Dos Castanheiros. Actas Port. Hortic. 2014, 23, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhamer, D.; Beede, R. Regulated Deficit Irrigation Effects on Yield, Nut Quality and Water-Use Efficiency of Mature Pistachio Trees. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2004, 79, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breisch, H. The Chestnut Industry in France. Acta Hortic. 2007, 784, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrot Jr, D.J.; Kilby, M.W.; Fangmeier, D.D.; Husman, S.H.; Ralowicz, A.E. Production, Growth, and Nut Quality in Pecans under Water Stress Based on the Crop Water Stress Index. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1993, 118, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengiz, O.; Ic, S.; Sarioglu, F. Physico-Chemical and Morphological Properties of Soils for Castanea sativa in the Central Black Sea Region. Int. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Marques, G.; Borges, O.; Portela, E.; Lousada, J.; Raimundo, F.; Madeira, M. Management of Chestnut Plantations for a Multifunctional Land Use under Mediterranean Conditions: Effects on Productivity and Sustainability. Agrofor. Syst. 2011, 81, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratanova-Doncheva, S.; Methy, M. Castanea sativa Mill.: Response of Water Stress. Application of the Chlorophyll Fluorescence. In Proceedings of the 2nd Congress of Ecologists of Macedonia, Ohrid, North Macedonia, 25–29 October 2003; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, A.; Zeng, N.; Yoon, J.-H.; Artale, V.; Navarra, A.; Alpert, P.; Li, L.Z. Mediterranean Water Cycle Changes: Transition to Drier 21st Century Conditions in Observations and CMIP3 Simulations. Environ. Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 044001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, P.; Coelho, F.E.S.; Tomé, A.R.; Valente, M.A.; Carvalho, A.; Pires, C.; Pires, H.O.; Pires, V.C.; Ramalho, C. 20th Century Portuguese Climate and Climate Scenarios. In Climate Change in Portugal: Scenarios, Impacts and Adaptation Measures (SIAM Project); Gradiva: Lisboa, Portugal, 2002; Volume 27, p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Peixoto, F.; Sang, H.W.W.F.; Torres-Pereira, J. Study of the Temperature Effect in Three Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Cultivars’ Behaviour. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 163, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menéndez-Miguélez, M.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P.; Majada, J.; Canga, E. Effects of Soil Nutrients and Environmental Factors on Site Productivity in Castanea sativa Mill. Coppice Stands in NW Spain. New For. 2015, 46, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretz, J.; Evans, R.G.; Proebsting, E.L. Leaf Water Potentials for Management of High Frequency Irrigation on Apples. Trans. ASAE 1984, 27, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, P.; Martins, A.; Tavares, R.M.; Lino-Neto, T. Diversity and Fruiting Pattern of Macrofungi Associated with Chestnut (Castanea Sativa) in the Trás-Os-Montes Region (Northeast Portugal). Fungal Ecol. 2010, 3, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, T.R.; Santos, J.A.; Silva, A.P.; Fraga, H. Influence of Climate Change on Chestnut Trees: A Review. Plants 2021, 10, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounous, G.; Beccaro, G. Chestnut Culture: Directions for Establishing New Orchards; e-NUCIS: Online, 2002; pp. 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vossen, P. Chestnut Culture in California; UCANR Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Perulli, G.D.; Boini, A.; Morandi, B.; Corelli Grappadelli, L.; Manfrini, L. Irrigation Improves Tree Physiological Performances and Nut Quality in Sweet Chestnut. Italus Hortus 2022, 29, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998; 97; pp. 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, J.E.; Turner, N.C. Water Potential Gradients in Field Tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1970, 46, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintermans, J.; De Mots, A. Spectrophotometric Characteristics of Chlorophylls a and b and their Phenophytins in Ethanol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biophys. Incl. Photosynth. 1965, 109, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Araújo-Alves, J.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Pimentel-Pereira, M.; Abreu, C.G.; Torres-Pereira, J. Effect of Chestnut Ink Disease on Photosynthetic Performance. J. Phytopathol. 2004, 152, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutchan, H.; Shackel, K.A. Stem-Water Potential as a Sensitive Indicator of Water Stress in Prune Trees (Prunus domestica L. Cv. French). J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1992, 117, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampinen, B.D.; Shackel, K.A.; Southwick, S.M.; Olson, W.H.; Dejong, T.M. Leaf and Canopy Level Photosynthetic Responses of French Prune (Prunus Domestica L. ‘French’) to Stem Water Potential Based Deficit Irrigation. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2004, 79, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackel, K.A.; Lampinen, B.; Southwick, S.; Olson, W.; Sibbett, S.; Krueger, W.; Yeager, J.; Goldhamer, D. Deficit Irrigation in Prunes: Maintaining Productivity with Less Water. HortScience 2000, 35, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, W.S.; Green, G.C. Plant Indicators of Wheat and Soybean Crop Water Stress. Irrig. Sci. 1981, 2, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, A.; Wample, R.L. Gas Exchange and Water Relations of Field-Grown Concord (Vitis labruscana Bailey) Grapevines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1994, 45, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellés, G.; Berger, A. Physiological indicators of plant water status as criteria for irrigation scheduling. Acta Hortic. 1990, 278, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratanova-Doncheva, S. Photosystem II activity in drought and high light conditions of Castanea sativa Mill. Saplings. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1043, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolhàr-Nordenkampf, H.R.; Öquist, G. Chlorophyll Fluorescence as a Tool in Photosynthesis Research. In Photosynthesis and Production in a Changing Environment: A Field and Laboratory Manual; Hall, D.O., Scurlock, J.M.O., Bolhàr-Nordenkampf, H.R., Leegood, R.C., Long, S.P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Epron, D.; Dreyer, E.; Bréda, N. Photosynthesis of Oak Trees [Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.] during Drought under Field Conditions: Diurnal Course of Net CO2 Assimilation and Photochemical Efficiency of Photosystem II. Plant Cell Environ. 1992, 15, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, A. The Study of Different Water Regimes on Photosynthetic Performance and Leaf Water Status of Pistachio Trees (Pistacia vera L.). J. Nuts 2019, 10, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hepaksoy, S.; Bahaulddin, A.; Kukul Kurttas, Y.S. The Effects of Irrigation on Leaf Nutrient Content in Pomegranate ‘İzmir 1513’. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1139, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzlyak, M.N.; Gitelson, A.A.; Chivkunova, O.B.; Rakitin, V.Y. Non-Destructive Optical Detection of Pigment Changes during Leaf Senescence and Fruit Ripening. Physiol. Plant. 1999, 106, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacelar, E.A.; Santos, D.L.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.M.; Gonçalves, B.C.; Ferreira, H.F.; Correia, C.M. Immediate Responses and Adaptative Strategies of Three Olive Cultivars under Contrasting Water Availability Regimes: Changes on Structure and Chemical Composition of Foliage and Oxidative Damage. Plant Sci. 2006, 170, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiouny, F.M. The Use of Municipal Treated Effluent for Peach Tree Irrigation. Proc. Fla. State Hortic. Soc. 1984, 97, 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- Javadi, T.; Arzani, K.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Study of proline, soluble sugar and chlorophyll a and b changes in nine Asian and one European pear cultivar under drought stress. Acta Hortic. 2008, 769, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, A.-D.; Abd El-Rhman, I.E.; Sahar, A.F. Effect of Some Antitranspirants and Supplementary Irrigation on Growth, Yield and Fruit Quality of Sultani Fig (Ficus carica) Grown in the Egyptian Western Coastal Zone under Rainfed Conditions. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2009, 5, 899–908. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghi, E.; Arzani, K.; Moallemi, N.; Barzegar, M. Evaluation of Chlorophyll Content and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters and Relationships between Chlorophyll a, b and Chlorophyll Content Index under Water Stress in Olea europaea Cv. Dezful. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2012, 68, 1154–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Proietti, P.; Famiani, F. Diurnal and Seasonal Changes in Photosynthetic Characteristics in Different Olive (Olea europaea L.) Cultivars. Photosynthetica 2002, 40, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Caramelo, L.; Gouveia, C.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Magalhães, M. Assessment of Weather-Related Risk on Chestnut Productivity. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11, 2729–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Almeida, P.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Peixoto, F. Ecophysiological Characterization of C. sativa Tress Growing under Different Altitudes. Acta Hortic. 2009, 844, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, T.; Pereira, M.G.; Pinto, J.G.; Caramelo, L.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Dacamara, C.C. Assessing Potential Changes of Chestnut Productivity in Europe under Future Climate Conditions. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2012, Vienna, Austria, 22–27 April 2012; p. 12312. [Google Scholar]

- Ciordia, M.; Feito, I.; Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Fernández, A.; Majada, J. Adaptive Diversity in Castanea sativa Mill. Half-Sib Progenies in Response to Drought Stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 78, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Fraga, H.; Belo-Pereira, M.; Santos, J.A. Assessment of Growing Thermal Conditions of Main Fruit Species in Portugal Based on Hourly Records from a Weather Station Network. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Response Mechanism of Plants to Drought Stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.; Dinis, L.; Coutinho, J.; Pinto, T.; Anjos, R.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Pimentel-Pereira, M.; Peixoto, F.; Gomes-Laranjo, J. Effect of Temperature and Radiation on Photosynthesis Productivity in Chestnut Populations (Castanea sativa Mill. Cv. Judia). Acta Agron. Hung. 2007, 55, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Cardoso, J.V.; Torres-Pereira, J.M.G.; Sequeira, C.A. Effect of Year and Cultivar on Chemical Composition of Chestnuts from Northeastern Portugal. Acta Hortic. 2005, 693, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernárdez, M.M.; De la Montaña Miguélez, J.; Queijeiro, J.G. HPLC Determination of Sugars in Varieties of Chestnut Fruits from Galicia (Spain). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2004, 17, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljak, I.; Idžojtić, M.; Šatović, Z.; Ježić, M.; Ćurković-Perica, M.; Simovski, B.; Acevski, J.; Liber, Z. Genetic Diversity of the Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Central Europe and the Western Part of the Balkan Peninsula and Evidence of Marron Genotype Introgression into Wild Populations. Tree Genet. Genomes 2017, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Stem Water Potential (MPa) | Quantum Efficiency of Photosystem II (Fv/Fm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| FI | −0.71 c | −0.90 c | 0.77 a | 0.80 a |

| DI | −0.92 b | −1.18 b | 0.70 b | 0.76 b |

| NI | −1.23 a | −1.41 a | 0.72 b | 0.68 c |

| Treatments | DM (%) | SLW (g DM per m−2) | TotChl (mg m−2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | ||||||

| July | September | July | September | July | September | |

| FI | 46.2 aΒ | 51.5 aA | 11.8 aA | 10.8 aA | 340.7 abA | 359.8 aA |

| DI | 43.1 bB | 49.7 abA | 10.4 abA | 11.2 aA | 318.2 bA | 342.2 abA |

| NI | 36.2 dB | 43.3 cA | 7.6 cA | 10.0 aA | 238.7 cA | 230.5 cA |

| 2018 | ||||||

| FI | 40.8 cA | 38.8 dA | 9.2 bA | 6.7 bB | 357.1 aA | 318.6 bB |

| DI | 45.6 aA | 47.8 bA | 11.3 aA | 7.5 bB | 366.1 aA | 329.0 abB |

| NI | 46.1 aA | 46.7 bA | 11.3 aA | 9.9 aA | 335.3 abA | 353.6 aA |

| Treatments | Fruit Set (%) | Yield (kg/Tree) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| FI | 42.3 a | 13.02 a | 15.07 a |

| DI | 34.4 b | 9.04 b | 10.97 b |

| NI | 33.4 b | 3.63 c | 7.36 c |

| Treatments | Nut Mass (g) | DM (%) | Perisperm (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | |||

| FI | 26.4 a | 46.9 c | 9.8 c |

| DI | 25.4 ab | 48.1 b | 10.7 b |

| NI | 19.1 c | 49.8 a | 11.8 a |

| 2018 | |||

| FI | 26.8 a | 46.7 c | 8.1 d |

| DI | 24.0 b | 48.6 b | 9.5 c |

| NI | 20.1 c | 50.1 a | 10.5 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsintsirakou, I.; Nanos, G.D. Physiological and Productive Characteristics of Castanea sativa Mill. Under Irrigation Regimes in Mediterranean Region. Water 2025, 17, 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233393

Tsintsirakou I, Nanos GD. Physiological and Productive Characteristics of Castanea sativa Mill. Under Irrigation Regimes in Mediterranean Region. Water. 2025; 17(23):3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233393

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsintsirakou, Ioanna, and George D. Nanos. 2025. "Physiological and Productive Characteristics of Castanea sativa Mill. Under Irrigation Regimes in Mediterranean Region" Water 17, no. 23: 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233393

APA StyleTsintsirakou, I., & Nanos, G. D. (2025). Physiological and Productive Characteristics of Castanea sativa Mill. Under Irrigation Regimes in Mediterranean Region. Water, 17(23), 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233393