Identification of Groundwater Recharge Potential Zones in Islamabad and Rawalpindi for Sustainable Water Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Preparation of Thematic Maps

2.2.1. Drainage Density

2.2.2. Slope

2.2.3. Elevation

2.2.4. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

2.2.5. Land Use Land Cover

2.2.6. Soil Classification

2.2.7. Water Table Depth

2.2.8. Moisture Stress Index

2.2.9. Topographic Wetness Index

2.2.10. Land Surface Temperature (LST)

2.2.11. Rainfall

2.3. Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)

2.3.1. Criteria Weights Assignment

2.3.2. Comparison Matrix for Paired Criteria

2.3.3. Assessing Matrix Consistency

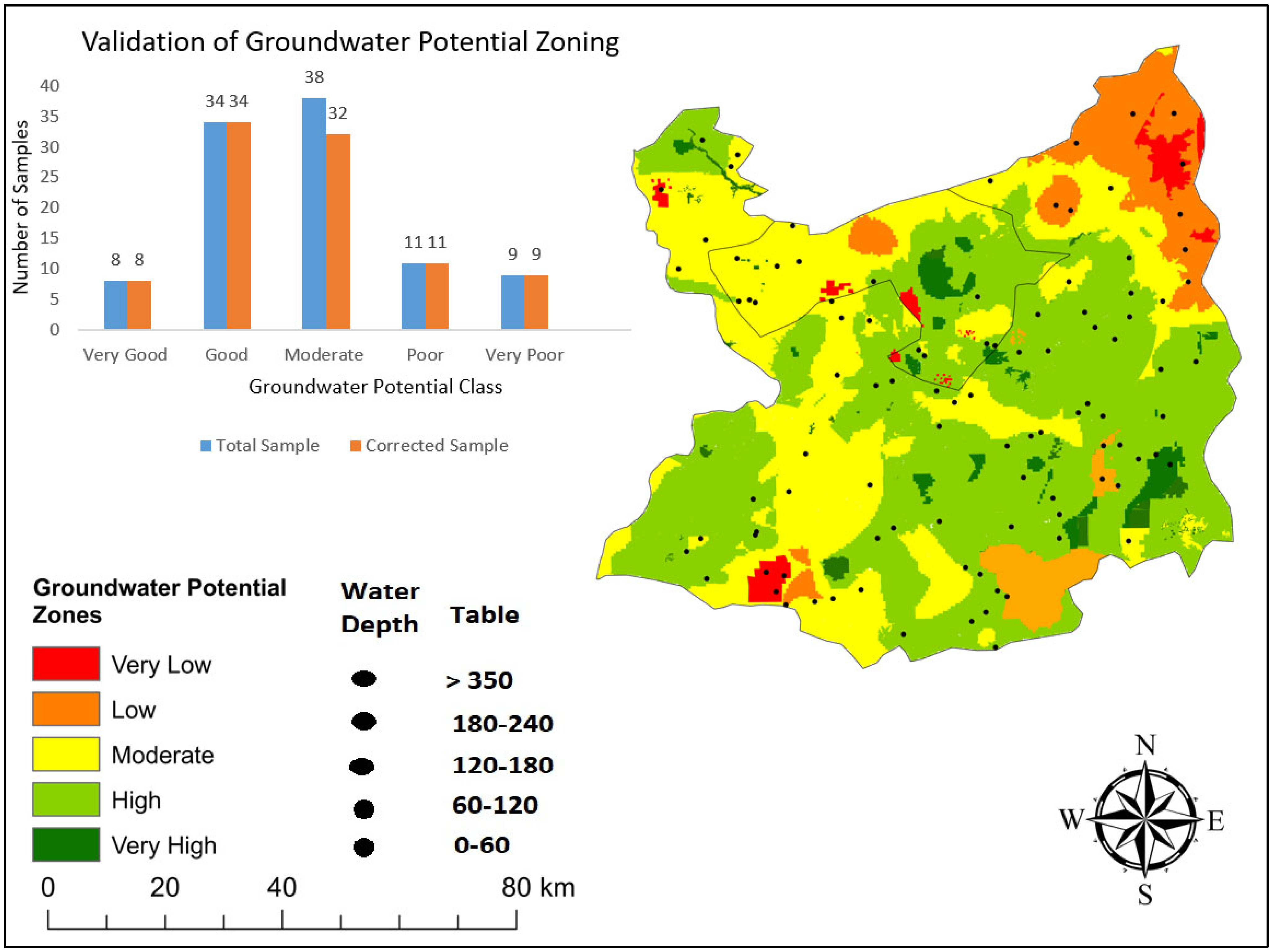

2.4. Assessment and Validation of Groundwater Potential Areas

- Very Good Potential: 0–60 m

- Good Potential: 60–120 m

- Moderate Potential: 120–180 m

- Low Potential: 180–240 m

- Very Low Potential: greater than 350 m

2.5. Kappa (K) Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Analysis of Parameters

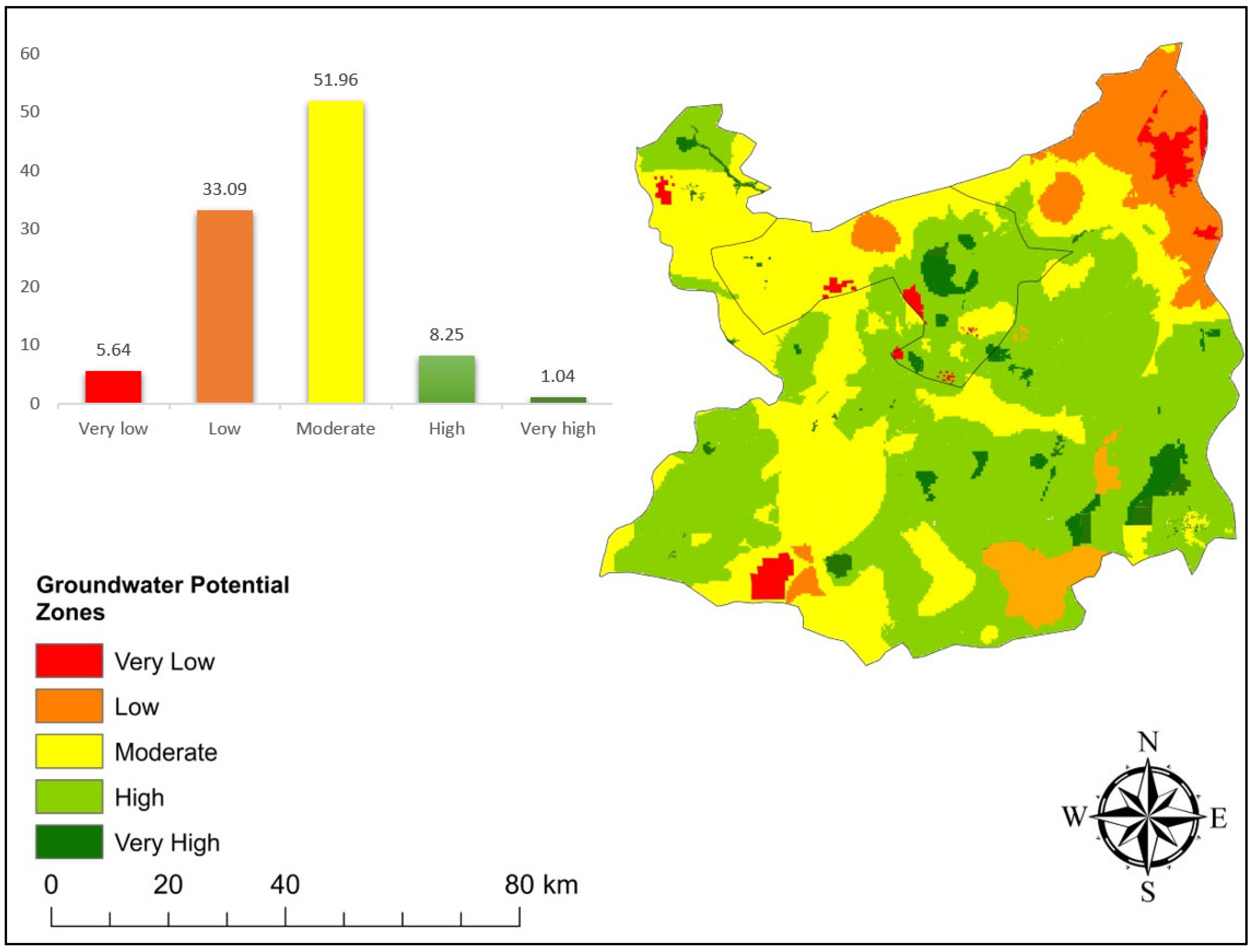

3.2. Development of Groundwater Potential Zoning

3.3. Comparative Analysis with Relevant Studies

3.4. Groundwater Potential Zones Model Consistency Check and Accuracy Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Lu, C.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, C.; Liu, B.; Shu, L. Determining the Groundwater Level in Hilly and Plain Areas From Multisource Observation Data Combined With a Machine Learning Approach. Hydrol. Process. 2025, 39, e70088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Singh, S.; Kumar, A. Groundwater Prospect Zone Mapping: A Geospatial Investigation with Decision Making in Mahendergarh District, Haryana. Asian J. Water Environ. Pollut. 2024, 21, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Piczak, M.L.; Nyboer, E.A.; Michalski, F.; Bennett, A.; Koning, A.A.; Hughes, K.A.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Cowx, I.G. Managing exploitation of freshwater species and aggregates to protect and restore freshwater biodiversity. Environ. Rev. 2023, 32, 414–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, M.; Rex, W.; Yu, W.; Uhlenbrook, S.; Von Gnechten, R. Change in Global Freshwater Storage; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2022; Volume 202. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Bao, S.; Yan, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R. Enhancing Sea Surface Salinity Short-Term Prediction Using Physically Informed Deep Learning. Appl. Ocean Res. 2025, 165, 104832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratoglu, A.; Wassar, F. Water at the intersection of human rights and conflict: A case study of Palestine. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1470201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, A.; Sajjad, A.; Sajid, G.H.; Ahmad, M.; Iqbal, M.; Khan, A.H.A. Assessing Recharge Zones for Groundwater Potential in Dera Ismail Khan (Pakistan): A GIS-Based Analytical Hierarchy Process Approach. Water 2025, 17, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, C.; Budak, M.; Yağmur, N.; Balçık, F. Comparison between random forest and support vector machine algorithms for LULC classification. Int. J. Eng. Geosci. 2023, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, M.; Malekmohammadi, B. Effects of excessive water extraction on groundwater ecosystem services: Vulnerability assessments using biophysical approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Laghari, Y.; Wei, Y.-C.; Wu, L.; He, A.-L.; Liu, G.-Y.; Yang, H.-H.; Guo, Z.-Y.; Leghari, S.J. Groundwater depletion and degradation in the North China Plain: Challenges and mitigation options. Water 2024, 16, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pandey, A.C. Geoinformatics based groundwater potential assessment in hard rock terrain of Ranchi urban environment, Jharkhand state (India) using MCDM–AHP techniques. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 2, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Roy, M.B.; Roy, P.K. Analysis of groundwater level trend and groundwater drought using Standard Groundwater Level Index: A case study of an eastern river basin of West Bengal, India. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, V.; Manzione, R.L.; Abiye, T.A.; Mukherji, A.; MacDonald, A. Introduction: Groundwater, sustainable livelihoods and equitable growth. In Groundwater for Sustainable Livelihoods and Equitable Growth; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. xvii–xxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Chinnasamy, P. Trends in groundwater research development in the South and Southeast Asian Countries: A 50-year bibliometric analysis (1970–2020). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 75271–75292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikka, A.K.; Alam, M.F.; Pavelic, P. Managing groundwater for building resilience for sustainable agriculture in South Asia. Irrig. Drain. 2021, 70, 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kafy, A.; Al Rakib, A.; Akter, K.S.; Rahaman, Z.A.; Jahir, D.M.A.; Subramanyam, G.; Bhatt, A. The operational role of remote sensing in assessing and predicting land use/land cover and seasonal land surface temperature using machine learning algorithms in Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Appl. Geomat. 2021, 13, 793–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paria, B.; Pani, A.; Mishra, P.; Behera, B. Irrigation-based agricultural intensification and future groundwater potentiality: Experience of Indian states. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Zahra, J.; Ali, M.; Ali, S.; Iqbal, S.; Kamal, S.; Tahir, M.; Aborode, A.T. Impact of water insecurity amidst endemic and pandemic in Pakistan: Two tales unsolved. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 81, 104350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Miao, C.; Gentine, P.; Mudryk, L.; Thackeray, C.W.; Berghuijs, W.R.; Zwiers, F. Constrained Earth System Models Show a Stronger Reduction in Future Northern Hemisphere Snowmelt Water. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Jabeen, M.; Ditta, S.A.; Ahmad, Z. Examining groundwater sustainability through influential floods in the Indus Plain, Pakistan. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, B.; Javid, K.; Mahmood, S.; Habib, W.; Hussain, S. Delineating groundwater potential zones using integrated remote sensing and GIS in Lahore, Pakistan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Xu, W.; Deng, J.; Guo, Y. Self-Aeration Development and Fully Cross-Sectional Air Diffusion in High-Speed Open Channel Flows. J. Hydraul. Res. 2022, 60, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Samara, F.; Alzaatreh, A.; Knuteson, S.L. Statistical analysis for water quality assessment: A case study of Al Wasit Nature Reserve. Water 2022, 14, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.; Ahmad, I.; Arshad, A.; Liu, J.; Rehman, Z.U.; Shafeeque, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Saifullah, M.; Iqbal, U. Numerical modeling of groundwater dynamics and management strategies for the sustainable groundwater development in water-scarce agricultural region of Punjab, Pakistan. Water 2023, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiq, M.M.; Rehman, H.U.; Khan, N.M. Impact of large diameter recharge wells for reducing groundwater depletion rates in an urban area of Lahore, Pakistan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.; Kumar, M.; Dashora, M.; Kumar, R.; Singh, A.; Kumar, A. Delineating Potential Groundwater Recharge Zones in the Semi—Arid Eastern Plains of Rajasthan, India. CLEAN–Soil Air Water 2025, 53, e202400013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, A.A.; Al-Areeq, A.M.; Benaafi, M.; Al-Suwaiyan, M.S.; Aghbari, A.A.A.; Alyami, M. Mapping groundwater potential zones in the Habawnah Basin of Southern Saudi Arabia: An AHP-and GIS-based approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdekareem, M.; Al-Arifi, N.; Abdalla, F.; Mansour, A.; El-Baz, F. Fusion of remote sensing data using GIS-based AHP-weighted overlay techniques for groundwater sustainability in arid regions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GoP. District Census Report, Islamaabad 2025. Available online: https://www.pbs.gov.pk/census-2023-district-wise/results/003 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Khan, N.; Gaire, N.P.; Rahmonov, O.; Ullah, R. Multi-century (635-year) spring season precipitation reconstruction from northern Pakistan revealed increasing extremes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.U.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, K.; Azmat, M.; Dahri, Z.H.; Khan, M.W.; Iqbal, Z. Hydro-Climatic variability in the Potohar Plateau of Indus River Basin under CMIP6 climate projections. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 156, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullateef, L.; Tijani, M.N.; Nuru, N.A.; John, S.; Mustapha, A. Assessment of groundwater recharge potential in a typical geological transition zone in Bauchi, NE-Nigeria using remote sensing/GIS and MCDA approaches. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, G.; Lu, S.; Chen, L.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, Y. Regional Differences in the Effects of Atmospheric Moisture Residence Time on Precipitation Isotopes over Eurasia. Atmos. Res. 2025, 314, 107813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.-Y.; Ni, B.-Y.; Wu, Q.-G.; Xue, Y.-Z.; Han, D.-F. Ice Breaking by a High-Speed Water Jet Impact. J. Fluid Mech. 2022, 934, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.N.; Chen, J.H.; Gao, C.Ø.; Zhou, Z.H.; Li, M.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.H. Peridynamics Simulation of Hydraulic Fracturing in Three-Dimensional Fractured Rock Mass. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 073628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lu, H.; Wang, G.; Qiu, J. Long-Term Capturability of Atmospheric Water on a Global Scale. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR034757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upwanshi, M.; Damry, K.; Pathak, D.; Tikle, S.; Das, S. Delineation of potential groundwater recharge zones using remote sensing, GIS, and AHP approaches. Urban Clim. 2023, 48, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Singh, A. Delineation of groundwater potential zone using analytical hierarchy process. J. Geol. Soc. India 2021, 97, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Qin, J.; Pervez, A.; Khan, M.S.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, K.; Rehman, N.U. Land-use/land cover changes contribute to land surface temperature: A case study of the Upper Indus Basin of Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Islam, F.; Tariq, A.; Ul Islam, I.; Brian, J.D.; Bibi, T.; Ahmad, W.; Ali Waseem, L.; Karuppannan, S.; Al-Ahmadi, S. Groundwater potential zone mapping using GIS and Remote Sensing based models for sustainable groundwater management. Geocarto Int. 2024, 39, 2306275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Miao, C.; Slater, L.; Ciais, P.; Berghuijs, W.R.; Chen, T.; Huntingford, C. Underestimating Global Land Greening: Future Vegetation Changes and Their Impacts on Terrestrial Water Loss. One Earth 2025, 8, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegeja, D.; Nedaw, D. Identification of groundwater potential zones using geospatial technologies in Meki Catchment, Ethiopia. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2025, 9, 1160–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, T.D.; Chang, S.W.; Kim, I.-H.; Kim, M.-G.; Chung, I.-M. Determination of potential aquifer recharge zones using geospatial techniques for proxy data of Gilgel Gibe Catchment, Ethiopia. Water 2022, 14, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahran, H.; Ali, M.Z.; Jadoon, K.Z.; Yousafzai, H.U.K.; Rahman, K.U.; Sheikh, N.A. Impact of urbanization on groundwater and surface temperature changes: A case study of Lahore city. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, S.R.; Vahedifard, F. Full-Scale Testing of Lateral Pressures in an Expansive Clay upon Infiltration. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2025, 37, 04024491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achu, A.; Reghunath, R.; Thomas, J. Mapping of groundwater recharge potential zones and identification of suitable site-specific recharge mechanisms in a tropical river basin. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 4, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Kou, J.; Miao, L.; Hu, F.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Meng, L. Exploring Diurnal Variation in Soil Moisture via Sub-Daily Estimates Reconstruction. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 134005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Dong, J.; Liu, X.; Kang, S.; Sun, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhang, X. Lithium Isotope Fractionation in Weinan Loess and Implications for Pedogenic Processes and Groundwater Impact. Glob. Planet. Change 2025, 252, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, M.O.; Gleeson, T.; Bierkens, M.; Ferguson, G.; Taylor, R. Defining renewable groundwater use and its relevance to sustainable groundwater management. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR032831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. An enhanced dual IDW method for high-quality geospatial interpolation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Bisht, D.S. Soil moisture–vegetation stress–based agricultural drought index integrating remote sensing–derived soil moisture and vegetation indices. In Integrated Drought Management, Volume 2; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 445–462. [Google Scholar]

- Vohra, R.; Kumar, A.; Jain, R.; Hemanth, D.J. Analysis and prediction of land surface temperature with increasing urbanisation using satellite imagery. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, S.; Tripathi, M.; Khalkho, D.; Al-Ansari, N.; Kumar, A.; Elbeltagi, A. Delineation of suitable sites for groundwater recharge based on groundwater potential with RS, GIS, and AHP approach for Mand catchment of Mahanadi Basin. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.; Umamaheswari, R.; Subashree, P.; Rajakumar, S.; Mukesh, P.; Priya, V.; Sampathkumar, V.; Logesh, N.; Ganesh Prabhu, G. Study on groundwater pollution and its human impact analysis using geospatial techniques in semi-urban of south India. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117532. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Chauhan, P.; Thakural, L.N.; Malviya, D.; Ahmad, R.; Sajid, M. Identification of groundwater recharge potential zone using geospatial approaches and multi criteria decision models in Udham Singh Nagar district, Uttarakhand, India. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 75, 1931–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chanda, K.; Pasupuleti, S. Spatiotemporal analysis of extreme indices derived from daily precipitation and temperature for climate change detection over India. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2020, 140, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, M. Introduction to the Analytic Hierarchy Process; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, G.; Kalyan, T.P.; Sudheer, B.; Kumar, K.M. Precipitation Disparity’s Impact on Groundwater Fluctuation Using Geospatial Techniques in the Ranipet District of Southern India. Asian J. Water Environ. Pollut. 2024, 21, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Huq, M.E.; Cai, B.; Altan, O.; Li, Y. Integrated remote sensing and GIS approach using Fuzzy-AHP to delineate and identify groundwater potential zones in semi-arid Shanxi Province, China. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 134, 104868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, X.; Luo, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xu, B. Risk Assessment and Classification of Reusability of Backwash Water from Drinking Water Treatment Plants. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2025, 1, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Park, J.-S. Modeling climate extremes using the four-parameter kappa distribution for r-largest order statistics. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2023, 39, 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, A.; Tariq, M.A.U.R.; Hashmi, M.Z.U.R.; Waseem, M.; Sarwar, M.K.; Ali, W.; Farooq, R.; Almazroui, M.; Ng, A.W. An overview of groundwater monitoring through point-to satellite-based techniques. Water 2022, 14, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, P.A.; Shu, L.; Amoako-Nimako, G.K. Assessment of groundwater potential zones by integrating hydrogeological data, geographic information systems, remote sensing, and analytical hierarchical process techniques in the Jinan Karst Spring Basin of China. Water 2024, 16, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.G.; Mohite, N.M. Identification of groundwater recharge potential zones for a watershed using remote sensing and GIS. Int. J. Geomat. Geosci. 2014, 4, 485–498. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.F.; Farooq, R.; Waseem, M.; Kohnova, S. How do land use changes affect temperature and groundwater in urban areas? An integrated remote sensing and machine learning approach. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 76, 3963–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Sarma, K. Evaluation of groundwater quality and depth with respect to different land covers in Delhi, India. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Res. 2013, 2, 630–643. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, N.P.; Waterhouse, H.; Dahlke, H.E. Influence of agricultural managed aquifer recharge on nitrate transport: The role of soil texture and flooding frequency. Vadose Zone J. 2021, 20, e20150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K. Land cover change and its impact on groundwater resources: Findings and recommendations. In Groundwater-New Advances and Challenges; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Influence Parameters | Values | Unit | Potentiality | Rating | Weight Assigned (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | 1242.80–1299.39 1186.20–1242.80 1129.61–1186.20 1073.01–1129.61 1016.42–1073.01 | mm | Very High High Moderate Low Very Low | 5 4 3 2 1 | 20 |

| LST | −0.1524–20.6631 20.6631–30.3900 30.3900–34.4753 34.4753–37.1988 37.1988–42.4548 | level | Very Low Low Moderate High Very High | 5 4 3 2 1 | 2 |

| NDVI | 9569–14,446 14,446–16,102 16,102–17,356 17,356–18,671 18,671–29,422 | level | Very Low Low Moderate High Very High | 1 2 3 4 5 | 2 |

| Soil Type Classification | Loam Clay Clay loam Sandy loam | level | Very High High Moderate Low | 5 4 2 1 | 15 |

| Land Use/Land Cover | Water Forest Range land Built Up Barren | level | Very High High Moderate Low Very Low | 5 4 3 2 1 | 3 |

| Elevation | 316–497 497–705 705–1059 1059–1504 1504–2268 | level | Very High High Moderate Low Very Low | 5 4 3 2 1 | 4 |

| Slope | 0–3.1337 3.1337–8.5057 8.5057–15.444 15.444–22.83 22.831–57.0781 | level | Very High High Moderate Low Very Low | 5 4 3 2 1 | 6 |

| MSI | 9568–14,445 14,445–16,101 16,101–17,355 17,355–18,670 18,670–29,422 | level | Very Low Low Moderate High Very High | 1 2 3 4 5 | 2 |

| TWI | 3.5253–12.655 −0.016–3.5253 −2.378–−0.016 −4.188–−2.378 −7.415–−4.188 | level | Very High High Moderate Low Very Low | 5 4 3 2 1 | 8 |

| Drainage Density | 57.104–71.380 42.828–57.104 28.552–42.828 14.276–28.552 0–14.276 | level | Very Low Low Moderate High Very High | 1 2 3 4 5 | 11 |

| Ground Water Depth | >320 240–300 120–240 60–120 0–60 | meter | Very Low Low Moderate High Very High | 1 2 3 4 5 | 28 |

| Score | Importance Intensity | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equal Importance | Both elements contribute equally. |

| 3 | Moderate Importance | One element ranks moderately higher than the other. |

| 5 | Strong importance | One element has substantial importance over the other. |

| 7 | Very Strong Importance | One element demonstrates a strong preference over the other. |

| 9 | Extreme Importance | One element demonstrates extreme preference over the other. |

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | Intermediate Values | Values when importance lies between two intensities. |

| Factors | Precipitation | GWL | Slope | Soil | Drainage Density | LULC | TWI | Elevation | NDVI | MSI | LST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Groundwater level | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Slope | 1/3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Soil | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Drainage density | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| LULC | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| TWI | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Elevation | 1/6 | 0 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| NDVI | 1/6 | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| MSI | 1/7 | 1/6 | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 |

| LST | 1/8 | 1/7 | 1/6 | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 |

| Sum | 3.42 | 5.54 | 8.53 | 10.62 | 14.17 | 18.92 | 20.67 | 27.33 | 30.00 | 37.50 | 45.00 |

| Factors | Rainfall | GW lvl | Slope | Soil | Drainage | LULC | TWI | Elevation | NDVI | MSI | LST | Sum | Criteria Weights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 2.86 | 0.26 |

| GW lvl | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 2.03 | 0.18 |

| Slope | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1.48 | 0.13 |

| Soil | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.1 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 1.11 | 0.10 |

| Drainage | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.1 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.91 | 0.08 |

| LULC | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.71 | 0.06 |

| TWI | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.58 | 0.05 |

| Elevation | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.44 | 0.04 |

| NDVI | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.03 |

| MSI | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.02 |

| LST | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.01 |

| Factor | Rainfall | Water Depth | Slope | Soil | Drainage Density | LULC | TWI | Elevation | NDVI | MSI | LST | SUM | Consistency Vector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 3.03 | 11.66 |

| Water Depth | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 2.16 | 11.71 |

| Slope | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 1.57 | 11.65 |

| Soil | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 1.16 | 11.55 |

| Drainage Density | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.96 | 11.53 |

| LULC | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.73 | 11.33 |

| TWI | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 11.27 |

| Elevation | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.44 | 11.14 |

| NDVI | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 11.16 |

| MSI | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 11.18 |

| LST | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 11.31 |

| Average | 11.41 | ||||||||||||

| n | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| RI | 0 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.9 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.45 | 1.49 | 1.51 |

| GWPZ | Area (km2) | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Very High | 6.9642 | 5.64 |

| High | 55.113 | 33.09 |

| Moderate | 221.05 | 51.96 |

| Low | 347.09 | 8.25 |

| Very Low | 37.706 | 1.04 |

| Class | Very Good | Good | Moderate | Poor | Very Poor | Total | Correct Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Good | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| Good | 0 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 34 |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 | 32 | 6 | 0 | 38 | 32 |

| Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| Very Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Total | 8 | 34 | 32 | 11 | 9 | 100 | 94 |

| Class | Total | Proportion | Correct Sample | Expected Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Good | 8 | 8/100 = 0.08 | 8 | 0.08 × 0.08 |

| Good | 34 | 34/100 = 0.34 | 34 | 0.34 × 0.34 |

| Moderate | 38 | 38/100 = 0.38 | 32 | 0.32 × 0.32 |

| Poor | 11 | 11/100 = 0.11 | 11 | 0.11 × 0.11 |

| Very Poor | 9 | 9/100 = 0.09 | 9 | 0.09 × 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zahra, H.; Sajjad, A.; Sajid, G.H.; Iqbal, M.; Khan, A.H.A. Identification of Groundwater Recharge Potential Zones in Islamabad and Rawalpindi for Sustainable Water Management. Water 2025, 17, 3392. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233392

Zahra H, Sajjad A, Sajid GH, Iqbal M, Khan AHA. Identification of Groundwater Recharge Potential Zones in Islamabad and Rawalpindi for Sustainable Water Management. Water. 2025; 17(23):3392. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233392

Chicago/Turabian StyleZahra, Hijab, Asif Sajjad, Ghayas Haider Sajid, Mazhar Iqbal, and Aqib Hassan Ali Khan. 2025. "Identification of Groundwater Recharge Potential Zones in Islamabad and Rawalpindi for Sustainable Water Management" Water 17, no. 23: 3392. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233392

APA StyleZahra, H., Sajjad, A., Sajid, G. H., Iqbal, M., & Khan, A. H. A. (2025). Identification of Groundwater Recharge Potential Zones in Islamabad and Rawalpindi for Sustainable Water Management. Water, 17(23), 3392. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233392