Abstract

The Yangtze River fishing ban policy is a central measure in China’s watershed governance, and the adaptability of its policy tools and collaborative mechanisms directly influences the sustainability and effectiveness of basin management. This study systematically examines the evolution of policy themes, the characteristics of policy tool combinations, and their alignment with intergovernmental collaborative governance needs, drawing on 120 central government policy texts issued between 2002 and 2024. Using frequency analysis and policy tool coding, the findings reveal that (1) policy themes have shifted from fishery resource control to comprehensive ecological protection and, more recently, to integrated watershed management, thereby driving progressively higher demands for intergovernmental collaboration. (2) The policy tool structure has long been dominated by environmental tools, supplemented by supply-side tools, while demand-side tools remain underdeveloped. Imbalances persist, such as excessive emphasis on resource inputs over capacity building in supply-side tools, rigid constraints with limited flexibility in environmental tools, and a reliance on publicity while underutilizing market incentives in demand-side tools. (3) Tool combinations have adapted to changing collaboration needs, evolving from rigid constraints and fiscal subsidies to institutional frameworks and cross-regional cooperation, ultimately forming a governance model characterized by systemic guarantees and diversified collaboration. Based on these findings, this study recommends strengthening long-term governance mechanisms, improving cross-regional collaborative structures, authorizing local governments to design context-specific implementation details, enhancing fishermen’s livelihood security and social development, expanding public participation and oversight, and exploring market mechanisms for realizing ecological product value. These measures aim to advance collaborative governance in the Yangtze River Basin and foster a balanced integration of ecological protection and social development.

1. Introduction

As the longest river in China and the third longest in the world, the Yangtze River basin spans 19 provincial-level administrative regions. It functions as a vital ecological barrier for China and a global hotspot for freshwater biodiversity, playing an irreplaceable role in maintaining regional ecological balance and the stability of global freshwater ecosystems. However, under the combined pressures of overfishing, water pollution, and habitat fragmentation, the basin’s aquatic ecosystems have suffered severe degradation. This degradation is primarily reflected in accelerated biodiversity loss, a continuous decline in fishery resources, and the ongoing deterioration of ecosystem services [1]. For example, by 2021 the biomass of fish resources in the Yangtze River had fallen to only 27.3% of its level in the 1950s, indicating a substantial long-term decline in the assemblage [2]. Beyond the aggregate biomass ratio, species-level indicators show critical status: the Chinese paddlefish is listed Extinct and the Yangtze sturgeon Extinct in the Wild [3,4].

In response to the ecological crisis, the Chinese government introduced spring fishing moratoria on the Yangtze beginning in 2002. A ten-year comprehensive fishing ban was piloted in the Chishui River during 2017–2026; in 2020, a basin-wide ban was launched in key natural waters, with year-round prohibitions across the mainstem, major tributaries, and connected lakes from 2021. Unlike seasonal closures, this is a long-term, basin-wide regime that was elevated to a national strategy with the enactment of the Yangtze River Protection Law in 2021. The scope of governance has also expanded—from initial fishery management to include ecological restoration, fishermen’s resettlement, and cross-regional coordination. This transformation highlights the fishing ban as a complex governance initiative involving multiple levels of government, administrative regions, and functional departments. The effectiveness of the policy therefore depends not on a single tool or top-level design, but on the capacity to achieve effective intergovernmental coordination across levels, regions, and departments [5]. Policy tools serve as the primary means by which governments allocate resources, establish regulations, and influence behavior [6]. Their combination and evolution directly shape the patterns and effectiveness of intergovernmental collaboration [7]. Accordingly, analyzing the dynamic evolution of these tools and assessing their adaptability to collaborative governance needs provides a novel perspective for evaluating and optimizing the effectiveness of the fishing ban policy.

As a central instrument for promoting integrated watershed governance and ecological restoration, the Yangtze River fishing ban has increasingly attracted academic attention, reflecting its growing policy significance. Early research primarily focused on the protection of endangered species such as the Yangtze River dolphin [8], employing methods such as field surveys, catch monitoring, and statistical analysis to assess policy effectiveness [9]. These studies demonstrated the short-term benefits of seasonal bans for fishery conservation and aquatic ecosystem recovery [10]. However, factors such as illegal fishing [11] and the limited duration of seasonal bans [12] prevented these measures from fundamentally reversing the decline in fishery resources [13].

As the fishing ban evolved into a national strategy, scholarly attention shifted to policy evolution, implementation challenges, and the effectiveness of collaborative governance. Research on policy evolution generally follows two approaches. The first divides the policy into stages to analyze their characteristics and internal logic—for example, Li Lihui’s four-stage classification based on policy text analysis [14]. The second applies frameworks such as multi-stream theory [15] and policy process models [16] to explore the institutional evolution and formation logic of the decade-long fishing ban.

At the implementation level, studies reveal persistent challenges, particularly in social security for fishermen’s resettlement [17], disparities in local enforcement and unclear responsibilities [18], and the lack of effective cross-regional coordination mechanisms [19]. These challenges not only hinder implementation but also underscore the urgency of establishing a stable and efficient collaborative governance framework. Regarding governance effectiveness, research has focused on policy performance, cross-regional collaboration, and social protection outcomes. Some scholars argue that uneven enforcement among local governments and vague responsibility divisions have weakened coordination effectiveness [20]. Others emphasize that while compensation policies have improved fishermen’s livelihoods to some extent, regional disparities in protection have limited overall satisfaction [21]. Additional studies note that collaboration mechanisms remain insufficient in terms of information sharing, resource integration, and cross-departmental enforcement, pointing to the need for a more institutionalized cooperation platform [22].

Internationally, fisheries management and watershed governance are also key topics in public policy and environmental governance. Research in this field largely focuses on three dimensions: fisheries policy and transnational cooperation, integrated watershed management and social participation, and intergovernmental collaborative governance and cooperation networks. For example, the European Union’s Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) is a classic case of transnational governance. It fosters cooperation among member states through legal regulations, quotas, and subsidies to ensure sustainable resource use, though it has been widely criticized for rigidity and limited regional adaptability [23]. In the Amazon Basin, governance highlights the importance of cross-regional collaboration and community participation, with evidence showing that cooperation among states and engagement of local communities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are essential for ecological restoration and sustainable development [24]. Adaptive governance frameworks have also emphasized the role of multi-level learning and social capital [25]. In the United States, experiences from six watershed governance programs demonstrate that responsibility division, fiscal incentives, and information sharing between federal and local governments are core mechanisms for improving governance [26]. Likewise, institutional collective action theory has been applied internationally to highlight the role of norms, trust, and cooperation networks in lowering collaboration costs [27]. For instance, Huhe et al. used social network analysis to illustrate how structural features of EU cooperation networks influence policy implementation [28].

In summary, while prior research on the Yangtze River fishing ban has yielded valuable insights into its evolution, implementation challenges, and collaborative governance mechanisms, three key gaps remain. First, full-cycle tracking is lacking, with most studies focusing on individual stages or policy cycles and failing to provide quantitative evidence of changes from 2002 to 2024. Second, dynamic analyses are limited, as most studies discuss legal, administrative, or economic tools in isolation rather than examining how tool combinations dynamically respond to shifting collaboration needs. Third, international experience has not been sufficiently localized, as theories of policy tools have rarely been integrated with China’s administrative system and watershed characteristics. Building on these gaps, this paper addresses three questions: (1) How have the themes of the Yangtze River fishing ban evolved from 2002 to 2024? (2) How have intergovernmental collaborative governance needs been reflected and developed during this evolution? (3) To what extent are policy tool configurations aligned with these needs? To address these questions, this study systematically examines 120 Yangtze River fishing-ban policy documents issued by China’s central government between 2002 and 2024. Through high-frequency word analysis, it maps the evolution of policy themes and identifies the characteristics of intergovernmental collaborative-governance needs; combined with policy tool coding, it assesses the alignment of tool configurations with these needs, thereby offering policy insights and empirical evidence to strengthen watershed governance in the Chinese context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Selection

This study examines the Yangtze River fishing ban policy documents issued by the central government between 2002 and 2024. Central government policies were chosen because they define the core governance direction and minimize interference from regional heterogeneity in analyzing the policy’s evolutionary logic. To ensure both authority and comprehensiveness, the search relied on two major legal databases—Peking University Law Database (PKU Law) and Legal Star—as well as official government portals, including the State Council, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment. The databases provide comprehensive collections of central administrative regulations and departmental rules, while the government portals supplement specific documents not covered by third-party platforms.

The search was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, the keyword “Yangtze” was used to preliminarily identify policies related to the river basin, while excluding documents unrelated to ecological protection or fishery management. In the second phase, additional keywords such as “Yangtze fishing ban”, “Yangtze fishing ban and fishery resource protection”, and “aquatic organism protection” were applied to capture core governance documents. Strict screening criteria were adopted: only documents classified as laws, regulations, opinions, measures, notices, announcements, and rules were retained, while approvals, reports, and correspondence were excluded. Redundant or incomplete documents were also removed, resulting in a final dataset of 120 valid central policy texts.

2.2. Basis for Stage Division

Drawing on previous academic research on the periodization of the Yangtze River fishing ban policy [14,29,30], this study identifies key policy milestones based on the release dates of major guiding documents. Accordingly, the fishing ban policy is divided into three stages: (1) the implementation of the spring fishing moratorium system (2002–2016), (2) the implementation of the full fishing ban (2017–2019), and (3) the promotion of the ten-year full fishing ban (2020–2024). The 120 policy texts were categorized into three groups corresponding to these stages.

2.3. Quantitative Analysis of Policy Texts

Quantitative policy text analysis systematically and quantitatively examines policy documents to uncover relationships and underlying logic. This method characterizes policies, infers their antecedents and consequences, and provides quantitative evidence for evaluating implementation effectiveness. In this study, two text-mining tools were employed: the ROST Text Mining System, version 6 (ROST CM6) for high-frequency word analysis and NVivo 12 Plus for coding analysis. These tools were used to examine the thematic evolution of the Yangtze River fishing ban policies and the adaptability of policy tools.

2.3.1. High-Frequency Word Analysis

ROST CM6 is a widely used Chinese text-mining tool capable of automated word segmentation, high-frequency word analysis, and topic extraction [31]. This study used ROST CM6 to extract high-frequency words and identify key issues in the policy texts. By analyzing the most frequently occurring terms, the study inferred the core policy content and thematic evolution across different stages. The analytical process included:

- (1)

- Text Processing: The three groups of stage-based texts were imported into ROST CM6. A custom stopword list was created to exclude meaningless terms such as “this notice” and “various provinces”.

- (2)

- Word Segmentation and Frequency Statistics: The software conducted word segmentation using a Chinese word database and extracted the 15 most frequent words in each group.

2.3.2. Policy Tool Coding

NVivo 12 Plus is a qualitative data analysis software widely applied in social science research, particularly for coding policy texts [32]. This study used NVivo 12 Plus to code policy texts, reveal implementation approaches, and analyze the evolution of policy tools across stages. The process included:

- (1)

- Definition of the Coding Framework: Building on Rothwell and Zegveld’s classic classification of policy tools [33], this study categorizes tools into three types: supply-side, demand-side, and environmental. In the context of the Yangtze River fishing ban, these are defined as follows: supply-side tools refer to the government’s direct provision of resources such as talent, information, technology, and funding to expand elements related to policy objectives, thereby directly advancing their achievement. Environmental tools involve creating favorable institutional conditions for implementation through the establishment of policy goals, plans, regulations, and standards. Demand-side tools primarily function by stimulating or generating demand for policy objectives, encouraging participation and support from social actors, and promoting policy realization. Furthermore, drawing on Yang Yang’s refinement of secondary tools for the Yangtze River fishing ban [30], this study further disaggregates the three categories into a secondary tool system. The detailed classification and definitions of these secondary tools are presented in Table 1. This refinement enables a more precise analysis of each tool’s role in policy implementation and reveals their trajectories of change across different stages.

Table 1. Classification and Meaning of Policy Tools.

Table 1. Classification and Meaning of Policy Tools. - (2)

- Text Coding: The stage-based policy texts were imported into NVivo 12 Plus. Based on the classification framework, both primary and secondary coding nodes were created in the software. Each paragraph or sentence was then coded and linked to the corresponding node whenever it referred to a specific policy tool.

- (3)

- Stage Statistics: After coding, the number and proportion of secondary-tool nodes at each stage were exported to analyze their characteristics and trends of evolution.

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy Themes and Intergovernmental Collaborative Governance Needs

High-frequency keywords directly reflect the core issues and focal points of policies. Their changes over time reveal the trajectory of the Yangtze River fishing ban policy themes and highlight the dynamic adjustment logic of intergovernmental collaborative governance needs. Table 2 presents the top 15 high-frequency words from central government policy texts between 2002 and 2024. The following stage-based analysis explores the evolution of policy themes and corresponding shifts in collaborative governance needs.

Table 2.

Word Frequency Analysis of Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy Texts at the Central Level Across Different Time Periods.

3.1.1. Spring Fishing Ban System Implementation Stage (2002–2016)

During this stage, high-frequency keywords included “fisheries”, “inspection”, “water areas”, “fishing”, “law enforcement”, “fisheries administration”, and “fishing moratorium period”. Among them, “fisheries” appeared 428 times, indicating that policies in this period primarily targeted fishery resource management. The main goal was to curb overfishing through enhanced law enforcement and strict regulation of the moratorium.

In terms of intergovernmental collaboration, coordination was relatively weak. Implementation was mainly led by a single ministry—such as the Ministry of Agriculture—with collaboration limited to fishery law enforcement, including joint crackdowns on illegal fishing with the Ministry of Public Security. Cross-regional cooperation was nearly absent. Local governments mainly executed central directives and had limited institutional capacity or autonomy for proactive collaboration. The singularity of policy themes in this stage meant that intergovernmental collaboration demands were low, relying primarily on vertical management without forming cross-hierarchical or cross-regional governance structures to address basin-wide challenges.

3.1.2. Full Fishing Ban Implementation Stage (2017–2019)

In this stage, high-frequency keywords shifted to “protection”, “ecology”, “Yangtze River”, “basin”, “environment”, “aquatic organisms”, and “key”. This change reflected an expansion of policy goals from fishery management to comprehensive ecological protection of the basin. Following the introduction of the Yangtze River Ecological Protection strategy in 2016, ecological restoration became the central objective. Policy focus moved toward basin-wide coordination, water ecological restoration, and biodiversity conservation, as illustrated by efforts to establish ecological compensation mechanisms in the cross-provincial Shishui River Basin.

The shift in themes substantially increased demands for intergovernmental collaboration. Ecological protection required cross-boundary cooperation, such as the joint enforcement of fishing bans in the middle-reach lakes by Hubei, Hunan, and Jiangxi provinces. Collaboration also expanded beyond law enforcement to cover ecological protection, environmental restoration, and social security, engaging multiple ministries, including the Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. The rising frequency of terms such as “departments”, “responsibilities”, “basin”, and “regions” underscored the growing importance of responsibility-sharing. Thus, intergovernmental collaboration shifted from vertical enforcement to cross-regional, multi-sectoral cooperation, though systematic collaborative mechanisms remained underdeveloped.

3.1.3. Ten-Year Fishing Ban Full Promotion Stage (2020–2024)

In this stage, high-frequency keywords centered on “Yangtze River”, “aquatic”, “protection”, “biodiversity”, “fishermen”, “law enforcement”, “departments”, “basin”, and “system”. These terms highlight the dual goals of integrated basin-wide ecological protection and livelihood support for fishermen. Frequent appearances of “protection” and “biodiversity” signal the prioritization of biodiversity conservation, while repeated mentions of “fishermen” emphasize resettlement and social security as core concerns. The recurrence of “law enforcement” and “departments” reflects the growing need for joint enforcement and interdepartmental coordination, with information sharing emerging as a critical element. References to “basin” and “system” indicate a stronger focus on integrated watershed governance requiring coordination across upstream and downstream, as well as between riverbanks.

Collaborative governance in this period extended beyond enforcement to address deeper challenges such as cross-regional resettlement and ecological compensation. For instance, training programs for displaced fishermen in upstream provinces (e.g., Anhui, Jiangxi) needed to be linked with employment opportunities in downstream regions such as the Yangtze River Delta. The frequent mention of “local” reflected increasing attention to local governance autonomy and regional differentiation. Consequently, intergovernmental collaboration shifted from task-based cooperation to institutionalized collaboration, with both its depth and breadth significantly enhanced. Nonetheless, challenges remain in ensuring the effective implementation of collaborative mechanisms and adapting to regional differences.

In sum, from 2002 to 2024 the Yangtze River fishing ban policy evolved through three stages: resource-oriented management (2002–2016), basin-wide ecological protection (2017–2019), and integrated watershed governance (2020–2024). Correspondingly, intergovernmental collaboration progressed from limited vertical enforcement to cross-regional, multi-departmental cooperation, and finally to institutionalized, cross-sectoral coordination that incorporated ecological protection, fishermen’s livelihoods, and local governance. This evolutionary process reflects the policy’s adaptive response to the complexities of Yangtze River governance and provides a clear demand orientation for the dynamic adjustment of policy tools in the future.

3.2. Analysis of the Supportive Role of Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy Tools in Collaborative Governance

Through the classification and coding of policy tools, this study identifies the configurations adopted by the government across different stages to implement the fishing ban policy. It further explores how these tools responded to collaborative governance needs and supported different stages of governance, thereby providing an empirical basis for assessing future tool adaptability and optimizing policy design.

3.2.1. Characteristics of Policy Tool Configuration

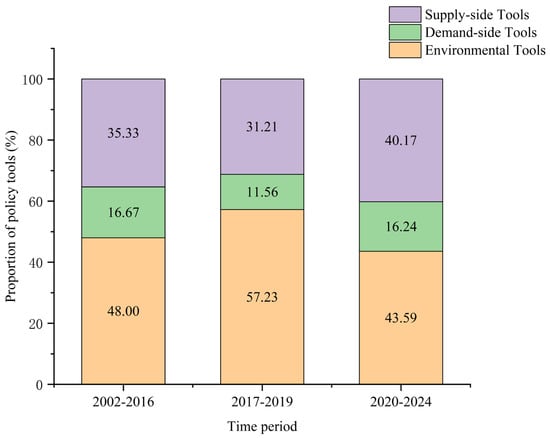

Figure 1 illustrates the proportions and trends of environmental, demand-side, and supply-side policy tools across the three stages. Table 3 presents the detailed classification, node counts, and proportions of each tool type, clearly highlighting the differences in tool combinations and the structural evolution of policy instruments.

Figure 1.

Changes in the Proportions of Policy Tools in the Central Government’s Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy (2002–2024).

Table 3.

Specific Classification and Proportions of Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy Tools at the Central Level Across Different Periods.

From 2002 to 2024, the Yangtze River fishing ban policy was characterized by a configuration dominated by environmental tools, supplemented by supply-side tools, and with limited application of demand-side tools. The relative proportions of these three types of tools shifted dynamically in accordance with governance stages, closely aligning with the evolution of policy themes and collaborative governance needs.

Environmental tools consistently formed the core, with their proportion first rising and then declining, while their functional emphasis shifted from rigid institutional construction in the early stage to flexible framework guidance in later stages. Between 2002 and 2016, environmental tools—mainly procedural norms and supervisory checks—accounted for 27.34%. Their primary role was to establish procedures and supervisory standards for enforcing the ban, thus delineating institutional boundaries for vertical coordination between central and local governments. A representative example is the Spring Fishing Ban Notice issued by the former Ministry of Agriculture in 2002. From 2017 to 2019, legal regulations and institutional guarantees increased significantly (13.87% and 11.56%, respectively). The Ten-Year Fishing Ban Plan for the Chishui River exemplified this stage by introducing horizontal ecological compensation provisions into cross-provincial bans, thereby supporting coordination among Guizhou, Sichuan, and Yunnan provinces. From 2020 to 2024, institutional guarantees further increased to 13.25%. The Yangtze River Protection Law (2020) established a basin-wide coordination mechanism and clarified intergovernmental and interdepartmental responsibilities, embedding collaborative governance into a normalized institutional framework.

Supply-side tools exhibited a trend of initial decline followed by growth, with their focus shifting from administrative promotion to resource support and capacity building. From 2002 to 2016, supply-side tools primarily included fiscal support and leadership promotion (18.00% combined). Fiscal allocations ensured procurement of enforcement equipment for local fishery departments, while high-level administrative directives temporarily coordinated interdepartmental enforcement. From 2017 to 2019, organizational collaboration rose to 13.87%, with environmental protection agencies beginning to assess watershed ecological outcomes and finance departments managing cross-provincial ecological compensation funds. A preliminary multi-department collaborative framework emerged. The proportion of technical equipment increased to 3.47%, with some provinces piloting drones for patrolling, thereby improving cross-regional enforcement efficiency. From 2020 to 2024, platform construction and employment assistance became core supply-side tools (8.97% and 6.84%, respectively). The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs advanced the Yangtze River fishing ban information platform, enabling real-time data sharing across provinces. Meanwhile, provinces such as Anhui and Jiangxi implemented employment assistance programs for fishermen, directly addressing cross-regional livelihood security needs.

Demand-side tools remained limited, mainly in the form of publicity and promotion, while market-oriented and tax incentive tools were rarely applied. From 2002 to 2016, publicity and promotion accounted for 6.00%, largely through websites and local bulletin boards disseminating ban-related information. From 2017 to 2019, market-oriented tools increased slightly, with pilot projects exploring compensation mechanisms linking ecological funds with aquaculture rights. However, these pilots were not extended basin-wide. Social participation decreased to 2.31%, with public and NGO involvement in supervision remaining underdeveloped. From 2020 to 2024, publicity and promotion rose to 8.97%, relying on public service announcements and community activities to raise awareness. Yet, market-oriented tools accounted for only 0.43%, and mechanisms for quantifiable cross-regional ecological compensation remained underdeveloped. Social participation increased modestly to 2.99%, with NGOs engaging in some ecological monitoring initiatives, though no large-scale collaborative supervision network had yet formed.

In summary, the evolution of the three tool types reflects a dynamic complementarity between environmental and supply-side tools, while demand-side tools have remained underutilized. This configuration illustrates the policy’s evolutionary logic: once the institutional framework was established through environmental tools, the focus naturally shifted toward execution support via supply-side tools. However, insufficient engagement of societal actors and market mechanisms has meant that intergovernmental coordination still relies heavily on administrative promotion, raising concerns about long-term sustainability.

3.2.2. Evaluation of the Adaptability of Policy Tools in Different Stages

Based on the characteristics of intergovernmental collaborative governance needs at different stages, this study evaluates the adaptability of policy tools in supporting collaboration across three dimensions: the degree to which they meet collaborative needs, their ability to promote cross-actor collaboration, and their flexibility.

- (1)

- Spring Fishing Ban Implementation Stage (2002–2016)

During this period, collaborative needs were limited to vertical enforcement between central and local governments.

The tool configuration was dominated by environmental and supply-side instruments, but overall adaptability was low, making it difficult to address cross-regional governance demands.

Degree of Meeting Collaborative Needs: Environmental tools focused on law enforcement norms, with procedural and supervisory instruments accounting for 27.34%. These supported central fisheries authorities in monitoring enforcement at the local level but did not address cross-provincial coordination, as illustrated by the absence of a joint mechanism for handling illegal fishing along the Hubei–Hunan border. Supply-side tools accounted for 20.66%, largely through organizational collaboration and fiscal support. However, cooperation was confined to fisheries departments, while environmental protection and public security agencies were not involved. Fiscal funds were primarily used for enforcement equipment procurement by individual departments, without resource coordination across agencies.

Promotion of Cross-Actor Collaboration: Collaboration relied mainly on administrative orders, with leadership promotion accounting for 8.67%. Special meetings between the Ministry of Agriculture and local officials temporarily coordinated enforcement but failed to establish a regular collaborative framework. Demand-side tools were minimal; social participation accounted for only 4.00%, largely limited to hotlines operated by fisheries departments. There was no standardized mechanism for public participation, and NGOs were absent, restricting external support for collaboration.

Tool Flexibility: Environmental tools were rigid, with laws and regulations representing 6.67%. For example, the 2002 Spring Fishing Ban Notice set uniform ban dates for the entire basin, disregarding ecological differences between upstream provinces (e.g., Yunnan, Sichuan) and downstream regions (e.g., Jiangsu, Shanghai). As a result, mismatches occurred between policy design and ecological realities. Supply-side tools also lacked flexibility: technical equipment accounted for only 2.00%, enforcement relied heavily on manual patrols, and information was transmitted via paper reports, making coordination inefficient.

From an effectiveness perspective, tools at this stage supported only basic vertical enforcement by a single department. The configuration was poorly aligned with the broader cross-regional and multi-sectoral governance needs of the Yangtze River Basin and failed to halt the decline of fishery resources.

- (2)

- Comprehensive Fishing Ban Implementation Stage (2017–2019)

During this stage, collaborative needs expanded to cross-regional and multi-departmental ecological protection.

Tool adaptability improved considerably, though gaps remained in social participation and regional differentiation.

Degree of Meeting Collaborative Needs: Environmental tools became stronger, with legal regulations rising to 13.87%. The Ten-Year Fishing Ban Plan for the Chishui River clarified responsibilities for Guizhou, Sichuan, and Yunnan, while creating a cross-provincial ecological compensation fund that directly addressed collaborative needs. Supply-side tools also expanded: organizational collaboration reached 13.87%, with environmental protection agencies monitoring water quality, finance departments managing compensation funds, and human resources departments piloting fisheries transition training. Technical equipment rose to 3.47%, with drones and satellite remote sensing tested to improve information flow and enforcement efficiency.

Promotion of Cross-Actor Collaboration: Platform construction increased to 4.62%, with the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs establishing a regular cooperation meeting mechanism. Multi-provincial fisheries departments began quarterly meetings to share enforcement data and cases. However, demand-side tools declined to 9.25%, with publicity and promotion only 3.47%, reflecting insufficient public awareness and weak societal involvement.

Tool Flexibility: Responsibility implementation increased to 9.83%, with local government heads identified as responsible for enforcement. However, differentiated assessment mechanisms were lacking, and no instruments addressed upstream ecological pressures versus downstream development needs, slowing progress on some collaborative tasks. Employment assistance (3.47%) provided fisheries transition training but did not link to job opportunities in labor-intensive regions such as the Yangtze River Delta, leaving some fishermen without stable employment.

Overall, the tool mix enabled basic cross-regional, multi-departmental collaboration, but weak social participation and inadequate regional adaptation hindered effectiveness.

- (3)

- Ten-Year Comprehensive Fishing Ban Promotion Stage (2020–2024)

In this stage, collaborative needs deepened into institutional and cross-sectoral collaboration. Tool adaptability reached its highest level, though limitations remained, particularly the lack of market mechanisms and incomplete legal frameworks.

Degree of Meeting Collaborative Needs: Institutional guarantees increased to 13.25%. The Yangtze River Protection Law established a coordination framework with the central government overseeing, provincial governments as primary implementers, and municipal and county governments executing. It clarified responsibilities for fishing bans, ecological restoration, and livelihood protection, thus providing a legal foundation for basin-wide collaboration. Supply-side tools also strengthened: platform construction accounted for 8.97%, with an enforcement information platform enabling real-time cross-provincial data sharing. Employment assistance (6.84%) facilitated cross-regional livelihood protection, with provinces such as Anhui and Jiangxi linking transition training to downstream employment opportunities in the Yangtze River Delta.

Promotion of Cross-Actor Collaboration: Demand-side tools rose modestly, with publicity and promotion at 8.97% through media campaigns and community programs. However, market-oriented tools accounted for only 0.43%, and ecological compensation still relied heavily on fiscal transfers, with market incentives largely absent.

Tool Flexibility: Goal planning accounted for 8.55%, enabling local governments to tailor ban measures to regional conditions, such as upstream provinces prioritizing native fish restoration and downstream provinces focusing on enforcement and habitat repair. Regional adaptability thus improved. Nonetheless, legal regulations were limited (4.27%), with gaps in cross-provincial enforcement authority and compensation standards, creating ambiguity in practice.

At this stage, tools strongly supported institutionalized collaboration, with broader and deeper cooperation achieved. Yet, the continued absence of market mechanisms left collaboration reliant on administrative orders, highlighting the need for innovation to ensure long-term sustainability and to foster a governance model integrating government, market, and society.

Overall, the configuration and adaptability of policy tools have undergone significant changes across different stages, closely aligning with collaborative governance needs and gradually shifting from single-dimensional management to diversified, institutionalized collaboration. However, the absence of robust market mechanisms and the incomplete refinement of certain legal provisions continue to constrain the long-term sustainability of the policy.

4. Discussion

This section analyzes the underlying mechanisms of policy tool evolution and, through comparative dialogue with international river basin governance experiences, highlights the limitations in the adaptability of existing tools.

4.1. Phased Mechanisms of Policy Tool Evolution

The evolution of policy tools in the Yangtze River fishing ban is not random but represents a dynamic adaptation to governance needs and policy objectives at different stages. Its core logic can be explained through the interaction between escalating governance contradictions and the functional responses of tools.

During the Spring Fishing Ban Implementation Stage (2002–2016), the main governance contradiction was the depletion of fishery resources combined with fragmented local enforcement, with policy objectives centered on establishing a basic order for the fishing ban. Environmental tools dominated (48%), as procedural norms and supervisory instruments clarified enforcement standards, addressing inconsistencies in vertical enforcement between central and local authorities. Supply-side tools (35.33%) provided fiscal subsidies and organizational collaboration to secure resources for enforcement. Demand-side tools (16.67%), largely publicity and promotion, only played an auxiliary role in mobilizing public cooperation. Overall, the approach reflected the governance logic of “first establishing rules, then executing them”.

In the Comprehensive Fishing Ban Implementation Stage (2017–2019), governance needs advanced toward strengthening upstream–downstream cooperation, shifting policy objectives to building a cross-regional collaborative framework. Environmental tools increased to 57.23%, with legal and regulatory (13.87%) and institutional guarantee (11.56%) instruments becoming central. The Ten-Year Fishing Ban Plan for the Chishui River clarified cross-provincial ecological compensation responsibilities, breaking administrative barriers. Supply-side tools (31.21%) and demand-side tools (11.56%) declined, reflecting the phase’s focus on first setting rules and then supplementing resources, with limited investment in cross-regional resources or market and societal mobilization. This prioritization aligns with Howlett’s theory of tool selection, which emphasizes that complex governance problems first require an institutional framework [34].

In the Ten-Year Comprehensive Fishing Ban Promotion Stage (2020–2024), the Yangtze River Protection Law shifted governance contradictions toward balancing ecological protection and livelihood security, with policy objectives elevated to building a long-term governance system. Environmental tools decreased to 43.59%, but institutional guarantees increased to 13.25%, moving from rigid constraints to framework guidance, thereby creating space for multi-stakeholder collaboration. Supply-side tools grew to 40.17%, with platform construction (8.97%) and employment assistance (6.84%) directly addressing cross-regional enforcement information sharing and fishermen’s livelihood transitions. Demand-side tools rose to 16.24%, with publicity (8.97%) and social participation (2.99%) strengthening co-governance.

The trajectory, in which environmental tools first increased and then declined while supply-side and demand-side tools initially decreased and later expanded, illustrates the evolutionary logic of shifting from rule-building to resource support and, ultimately, to multi-stakeholder collaboration. This reflects Folke et al.’s adaptive governance theory, which highlights the need for tools to dynamically adjust to governance stages to meet evolving demands and enhance system resilience [35].

4.2. Comparison with International River Basin Governance Experiences

Placing the Yangtze River fishing ban in the context of global river basin governance clarifies both its adaptability and its areas for optimization. The EU’s Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) emphasizes market-oriented demand-side tools, employing tradable quotas to regulate resource allocation and promote sustainable fisheries. In contrast, demand-side tools in the Yangtze River fishing ban peaked at only 16.67%, with market-oriented tools contributing less than 1% during 2020–2024. This reflects reliance on administrative leadership and limited market incentives. While the decline of demand-side tools during 2017–2019 was reasonable in a rule-prioritizing stage, their rebound after 2020 remains insufficient. Lessons from the CFP on ecological product value realization could be applied to activate market dynamics and balance interprovincial interests.

The Mississippi River Basin governance framework relies heavily on social participation tools, establishing a closed-loop supervision system through citizen litigation clauses. In comparison, social participation tools in the Yangtze River fishing ban peaked at 4% (2002–2016) and stood at only 2.99% (2020–2024), suggesting that social forces have not yet become a pillar of collaborative governance. According to Ostrom’s polycentric governance theory, effective governance depends on cultivating social capital; weak participation and insufficient accumulation of social capital undermine collaborative effectiveness [36]. Drawing on the U.S. River Basin Collaboration Committee, the Yangtze River model could integrate the public and NGOs into cross-regional collaboration as a context-dependent complement under continued government leadership, and, where appropriate, move beyond one-way publicity to targeted participation mechanisms.

4.3. Shortcomings of Current Policy Tools

Based on the evolution of tools and international comparisons, three main shortcomings remain:

- (1)

- Weak demand-side functions in later stages: Long-term reliance on publicity and promotion, coupled with underdeveloped market-oriented and resource-integration tools, leaves upstream provinces’ economic losses without market-based compensation, relying excessively on fiscal transfers.

- (2)

- Insufficient flexibility of environmental tools: Policy clauses remain dominated by uniform national rules, neglecting differences between upstream (ecological protection) and mid–downstream (law enforcement coordination) priorities. This increases coordination costs, contradicting Huitema et al.’s argument that environmental policies must balance uniformity and flexibility [37].

- (3)

- High resource dependence of supply-side tools: Heavy reliance on fiscal support and technical equipment, combined with inadequate platforms and capacity-building tools, results in strong local dependence on central resources. This hinders the development of autonomous collaborative mechanisms. As Emerson et al. note, effective collaboration requires both resources and capacities; resources without corresponding capacities risk being underutilized, weakening governance outcomes and sustainability [38].

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

This study analyzed 120 central government policy texts on the Yangtze River fishing ban issued between 2002 and 2024. It examined the evolution of policy themes within watershed governance and the adaptation of policy tools to intergovernmental collaborative governance needs. Using high-frequency word analysis and policy tool coding, the study traced the transition from the early spring fishing ban to the comprehensive ten-year fishing ban, assessing how policy tools at different stages supported intergovernmental collaboration. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Policy Themes Evolve with Governance Goals: Policy themes displayed phased characteristics that paralleled the upgrading of watershed governance goals, thereby driving the expansion of collaborative governance needs. In 2002–2016, the focus was on fishery resource control, with collaboration limited to vertical law enforcement between agricultural departments and local governments, without cross-regional coordination. In 2017–2019, themes shifted toward basin-wide ecological protection, and cross-provincial ecological compensation pilots in the Chishui River expanded collaboration to include ecological restoration and financial coordination. In 2020–2024, the theme evolved to integrated basin management, encompassing biodiversity conservation and fishermen’s livelihood transformation, with collaboration extending to joint law enforcement and livelihood security.

- (2)

- Policy Tool Structure Imbalance and Phased Adjustments: Policy tools remained imbalanced over time, marked by resource-heavy but capacity-weak features, rigid designs with limited flexibility, and strong reliance on publicity while lacking market-based mechanisms. Environmental tools consistently dominated, rising initially before declining, and shifting from rigid enforcement standards to broader institutional frameworks, though regional adaptability remained limited. Supply-side tools declined initially but rose later, transitioning from fiscal subsidies to cross-regional platform construction and employment assistance, yet fiscal dependence persisted and training programs accounted for less than 10%. Demand-side tools remained weak, relying primarily on publicity, with insufficient market incentives and social supervision.

- (3)

- Policy Theme Evolution Drives Governance Needs and Tool Adaptation: The evolution of governance needs was not an isolated adjustment but followed the staged development of policy themes. Tool combinations adapted accordingly, forming a closed-loop interaction between policy themes, governance needs, and tool responses. In 2002–2016, fishery resource control aligned with vertical enforcement needs, dominated by environmental tools and fiscal subsidies. In 2017–2019, ecological protection required cross-regional coordination, supported by institutional frameworks and interdepartmental collaboration. In 2020–2024, systematic ecological governance generated institutionalized collaborative needs, supported by environmental frameworks, cross-regional supply-side support, and social mobilization. This adaptation chain demonstrates the dynamic interplay of themes, governance needs, and tool configurations, offering empirical evidence for improving watershed governance and optimizing tools.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the findings, future optimization of the Yangtze River fishing ban policy can proceed along six dimensions:

- (1)

- Strengthen Long-Term Governance Mechanisms: Although the ten-year ban is a temporary institutional arrangement, ecological restoration and fishery recovery require longer-term guarantees. A mid-term evaluation should be conducted before the ban ends, exploring integration with ecological red-line management and fishery resource restoration planning to form a comprehensive “ban–restoration–management” mechanism.

- (2)

- Improve Cross-Regional Collaborative Governance Frameworks: Current collaboration mechanisms face overlapping responsibilities and high coordination costs. Building on the Yangtze River Protection Law, a cross-provincial governance committee or permanent coordination body should be established to oversee ecological compensation, law enforcement, and fishermen resettlement, advancing the shift from task-based to institutionalized collaboration.

- (3)

- Enhance Local Differentiated Implementation Capacity: Ecological and economic differences between upstream and downstream regions, as well as main and tributary rivers, necessitate differentiated implementation. Under a unified framework, local governments should be empowered to design context-specific rules, with mechanisms to incentivize innovation and adaptability, thereby improving flexibility and responsiveness.

- (4)

- Coordinate Livelihood Security and Social Development: Fishermen’s resettlement and livelihood transformation are critical for policy sustainability. Future policies should strengthen cross-regional employment matching mechanisms, link fishermen with downstream industries and urban labor markets, and expand social security systems to mitigate livelihood risks that could undermine the policy’s social foundation.

- (5)

- Expand Social Participation and Public Supervision: Participation by social organizations remains limited. Future strategies should enhance the role of NGOs, research institutions, and community groups in ecological monitoring, law enforcement oversight, and public education. This can be achieved through information disclosure platforms, supervision mechanisms, and funding programs, thereby strengthening multi-stakeholder co-governance as a complement to government leadership, applied where it demonstrably adds value.

- (6)

- Promote Ecological Value Realization through Market Mechanisms: Beyond fiscal compensation, diversified market mechanisms should be explored to convert ecological benefits into shared economic incentives, thereby enhancing interregional cooperation and ensuring the long-term sustainability of the policy.

In summary, future optimization should move beyond incremental improvements in policy tools and adopt a comprehensive approach that emphasizes long-term institutionalization, normalized collaboration, differentiated local implementation, broad social participation, and market-based mechanisms, ultimately achieving both ecological restoration and social development in the Yangtze River Basin.

5.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Research Directions

This study has two main limitations. First, the methodology relies on quantitative analysis of central-level policy texts. While this reveals macro-level trends in policy themes and tool configurations, it cannot capture the micro-level dynamics of intergovernmental collaboration, such as informal negotiations or the lived experiences of frontline enforcement and fishermen in transition. Second, causal analysis was not conducted. Although the study identifies patterns in tool evolution, the causal linkages between tools and governance outcomes (e.g., resource recovery, fishermen’s satisfaction) remain untested.

Future research could extend in two directions. One is to incorporate local case studies, focusing on typical provinces such as Hubei and Jiangsu, to analyze how local governments tailor tool configurations and innovate in livelihood transformation policies. Another is to adopt quantitative methods—such as difference-in-differences models combined with fishery resource monitoring and financial data—to validate causal relationships between tool configurations and policy outcomes, thereby enhancing the practical relevance of the findings and providing more robust empirical support for watershed policy optimization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.J.; writing—original draft preparation, L.J.; writing—review and editing, L.J. and T.M.; visualization, L.J.; supervision, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shanghai Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project (2024BJC017).

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dong, F.; Fang, D.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Q. Protection and Development After the Ten-Year Fishing Ban in the Yangtze River. J. Fish. Sci. 2023, 47, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shen, L.; He, Y.; Tian, H.; Gao, L.; Wu, J.; Mei, Z.; Wei, L.; Wang, L.; Zhu, T. Survey on Aquatic Biological Resources and Environmental Baseline Status in the Yangtze River (2017–2021). J. Fish. Sci. 2023, 47, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Psephurus gladius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/pdf/146104283 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- IUCN. Acipenser dabryanus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/pdf/61462199 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Liang, Y.; Huang, J.; He, J. Driving Mechanisms of Cross-Regional Environmental Collaborative Governance Networks: A Case Study of the Pan-Pearl River Delta. Geogr. Res. 2025, 44, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Qiu, J. Bibliometric and Content Analysis—Mining Implicit Information in Literature Groups. Lib. Inf. Work 2005, 49, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cai, T. Do Policy Instruments Effectively Improve the “Nine Dragons Governing Water” Dilemma?—A Study Based on Policy Texts from 1984 to 2018 on Water Pollution Control in China. Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 13, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W. Overview of Yangtze River Yangtze Finless Porpoise Relocation Protection. J. Anhui Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 34, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Gong, Y.; Tan, X.; Yang, Z.; Chang, J. Spatiotemporal patterns of the fish assemblages downstream of the Gezhouba Dam on the Yangtze River. Chinese Sci. (Life Sci.) 2012, 42, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Liu, S.; Xiong, F.; Chen, D.; Yang, R.; Chi, C.; Mu, T. Analysis of Fish Catch Composition and Biodiversity Before and After the Spring Fishing Ban in the Upper Yangtze River Mainstream. Res. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2008, 17, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Duan, X.; Chen, D.; Liao, F.; Chen, W. Study on the Status of Fishery Resources in the Middle Yangtze River. J. Aquat. Biol. 2005, 29, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y. The Historical Evolution, Theoretical Review, and Expansion of the Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy. J. Chongqing Three Gorges Univ. 2024, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W. Current Status and Protection Strategies of Fish Resources in the Yangtze River. Jiangxi Fish. Sci. Technol. 2011, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. The Change and Prospect of the Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy from the Perspective of Text Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J. Agenda Study of the Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy from the Perspective of Multi-Stream Theory. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z. Discussion on the Intermittent Transition Process of the Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy. Yangtze River Technol. Econ. 2023, 7, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Yang, Z.; Chu, J.; Mo, Y. Analysis of the Impact of Fishermen’s Transition Policy on Their Social Interactions Under the Ten-Year Fishing Ban in the Yangtze River. Rural Econ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S. Analysis on the Implementation Dilemma and Path Optimization of the County Government’s Prohibition and Exit of Fishing Policy in Yangtze River—A Case Study of Fushun County, Sichuan Province. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, Y. Improvement of the Criminal Judicial Cooperation Mechanism for Ecological Protection in the Urban Agglomeration in the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River—Taking 143 Criminal Judgments of Wuhan Jianghan District Court for Illegal Fishing of Aquatic Products as an Example. Yangtze Trib. 2018, 3, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y. Regional Differences and Optimization Paths of the Yangtze River Fishing Ban Policy. Agric. Disast. Res. 2024, 14, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Evaluation of Sustainable Livelihoods and Influencing Factors of Fishermen in the Yangtze River Basin. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B. Legislative Logic and Supporting System of the Fishing Ban System in the Yangtze River Protection Law. Res. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2021, 30, 3029–3037. [Google Scholar]

- Khalilian, S.; Froese, R.; Proelss, A.; Requate, T. Designed for failure: A critique of the Common Fisheries Policy of the European Union. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepstad, D.; McGrath, D.; Stickler, C.; Alencar, A.; Azevedo, A.; Swette, B.; Bezerra, T.; DiGiano, M.; Shimada, J.; da Motta, R.S.; et al. Slowing Amazon deforestation through public policy and interventions in beef and soy supply chains. Science 2014, 344, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environ. Change 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperial, M.T. Using collaboration as a governance strategy: Lessons from six watershed management programs. Admin. Soc. 2005, 37, 281–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Warner, M.E. Inter-municipal cooperation and costs: Expectations and evidence. Public Adm. 2015, 93, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhe, N.; Naurin, D.; Thomson, R. The evolution of political networks: Evidence from the Council of the European Union. Eur. Union Polit. 2018, 19, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y. Economic Analysis of Stakeholder Behavior in Public Policy—A Case Study of the Yangtze River Fishing Ban and Fishermen’s Transition Policy. J. Chongqing Univ. Sci. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 32, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, T. Evolutionary Logic and Practical Path of the Policy of Fishing Ban in the Yangtze River —From the Perspective of Policy Text Analysis. China Agric. Res. Reg. Plan. 2023, 44, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Pang, L. Key Issues and Solutions in the Construction of the Universal Pre-School Education Public Service System in China—An Analysis Based on the ROST Text Mining System. J. Hunan Normal Univ. Educ. Sci. Ed. 2019, 18, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsop, D.B.; Chelladurai, J.M.; Kimball, E.R.; Marks, L.D.; Hendricks, J.J. Qualitative Methods with Nvivo Software: A Practical Guide for Analyzing Qualitative Data. Psych 2022, 4, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, R.; Zegveld, W. An assessment of government innovation policies. Rev. Policy Res. 1984, 3, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M. The criteria for effective policy design: Character and context in policy instrument choice. J. Asian Public Policy 2017, 11, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Global Environ. Change-Human Policy Dimens. 2010, 20, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitema, D.; Mostert, E.; Egas, W.; Moellenkamp, S.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Yalcin, R. Adaptive water governance: Assessing the institutional prescriptions of adaptive (co-)management from a governance perspective and defining a research agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).