The Risk Assessment for Water Conveyance Channels in the Yangtze-to-Huaihe Water Diversion Project (Henan Reach)

Abstract

1. Introduction

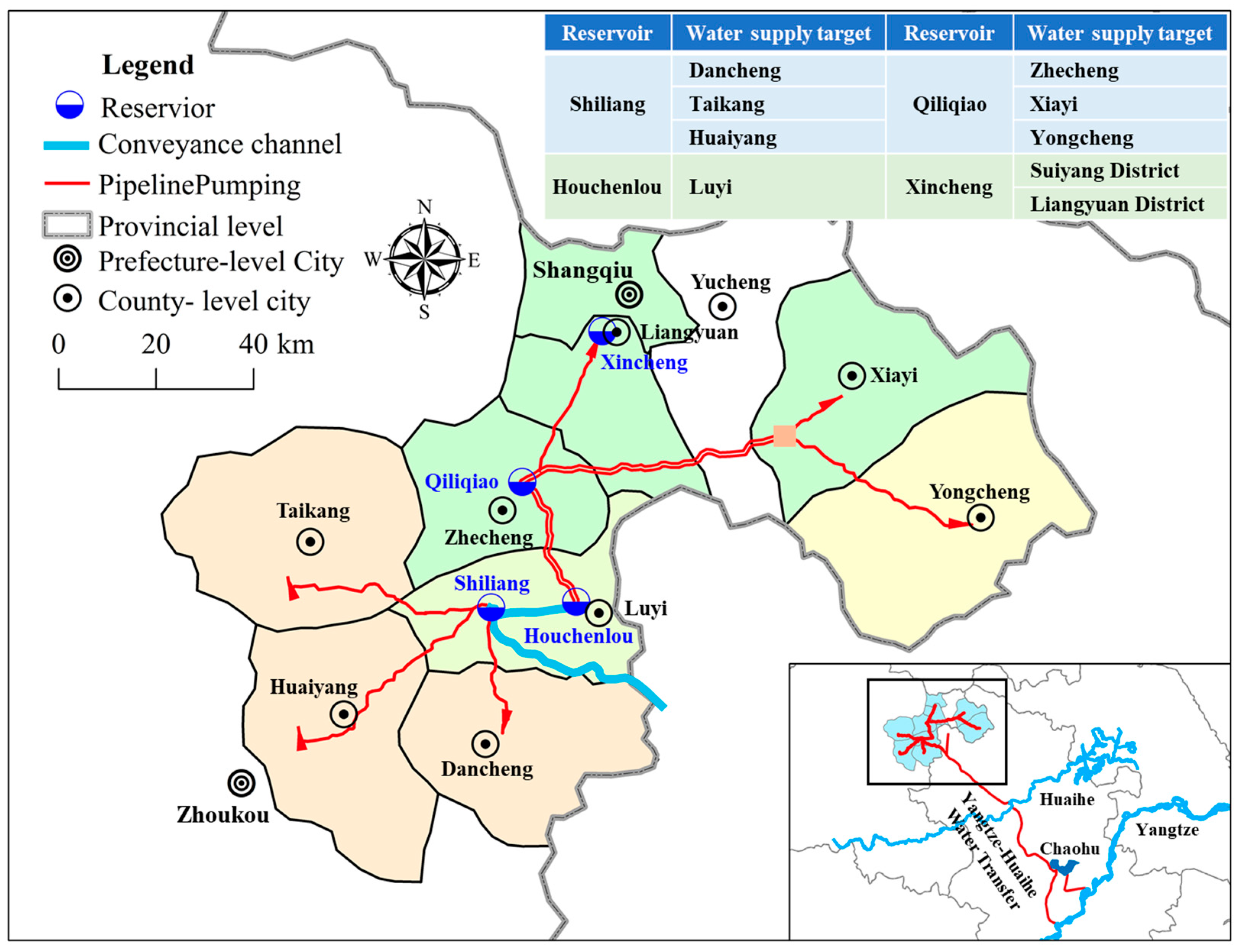

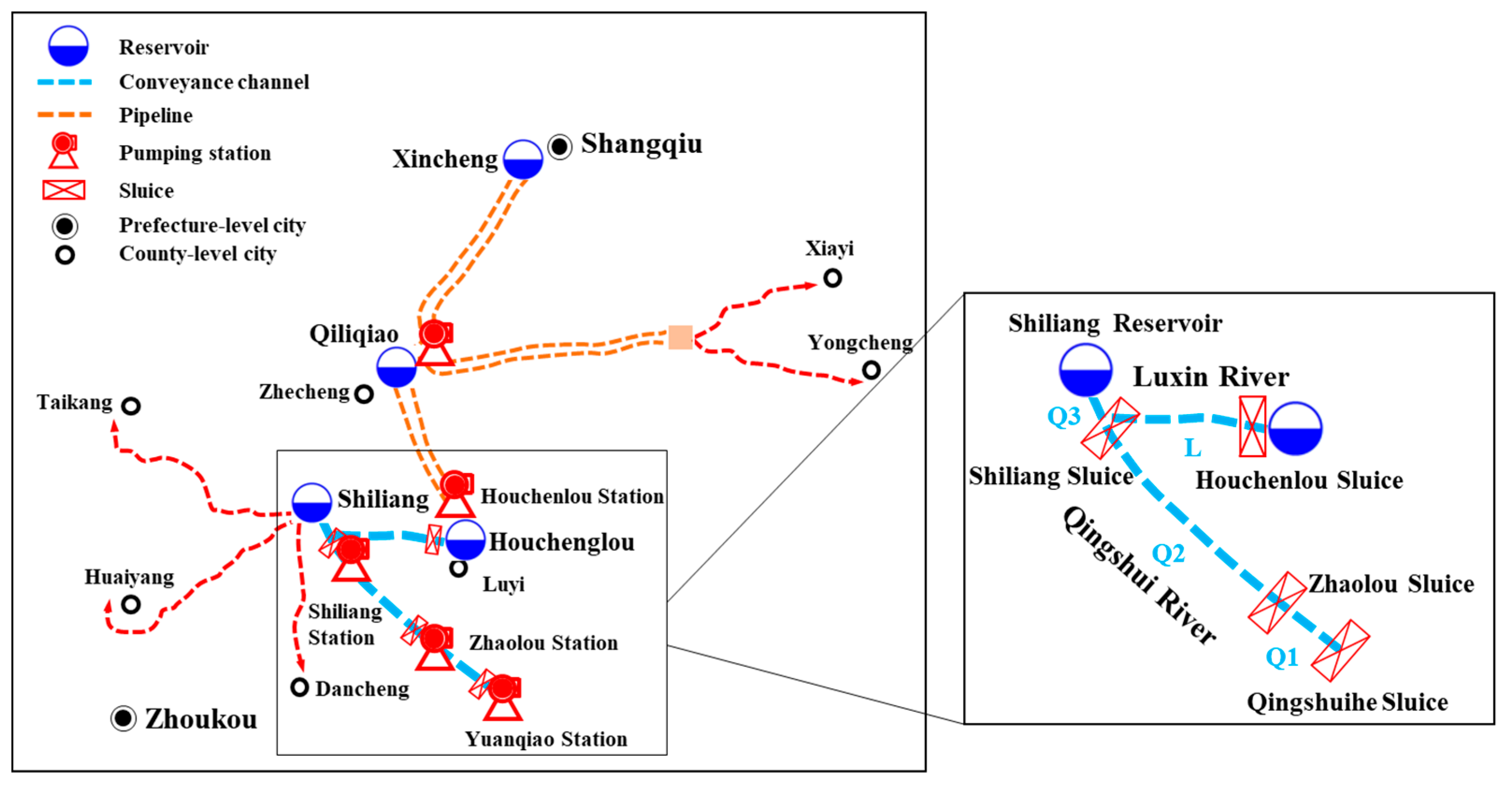

2. Study Area

3. Comprehensive Risk Assessment Framework for Water Conveyance Channels

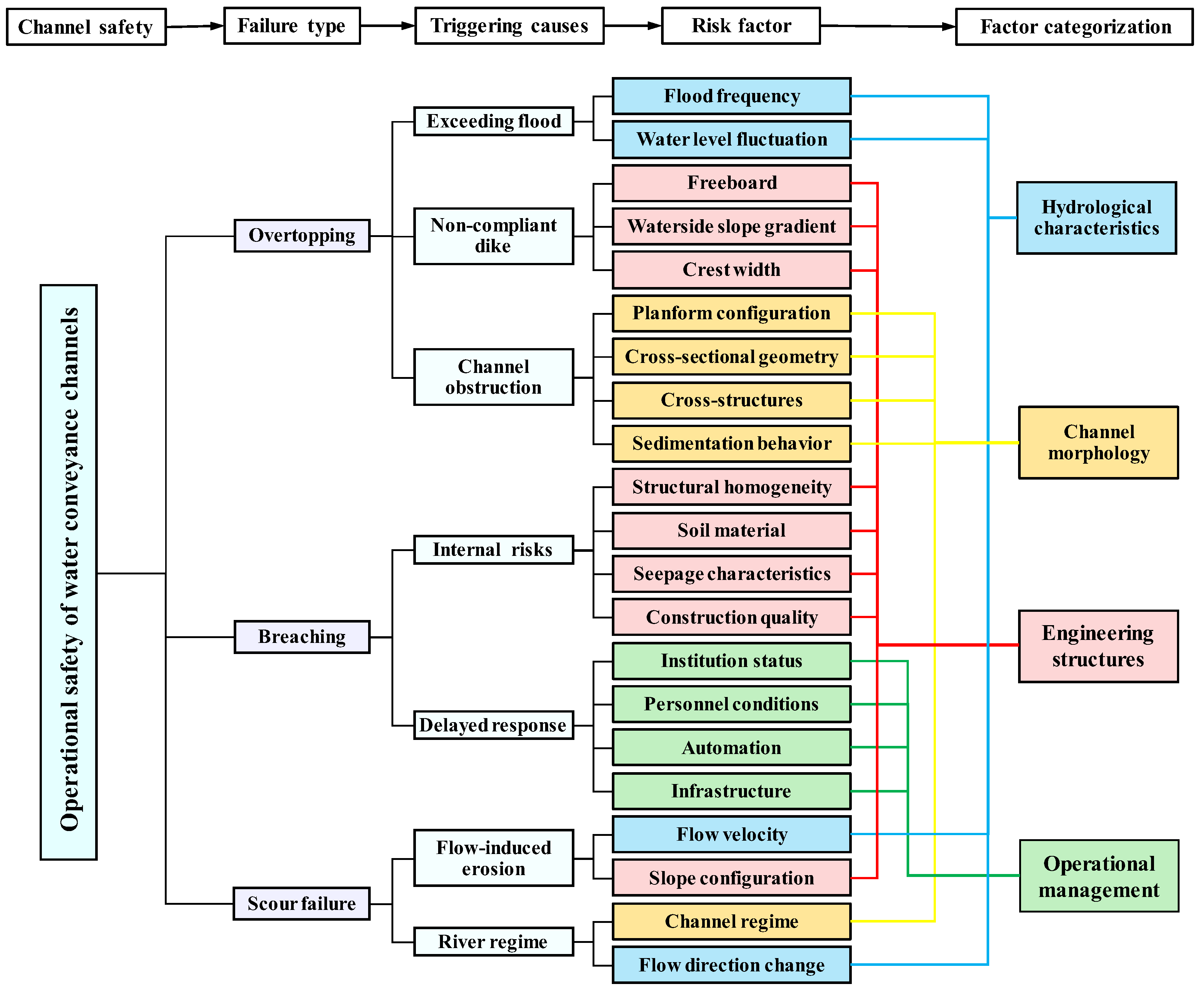

3.1. Risk Probability Assessment System for Water Conveyance Channels

3.1.1. Consequence Reverse Diffusion Method

3.1.2. Identification of Operational Safety Risk Factors

3.1.3. Construction of Risk Probability Assessment System

- (1)

- Hydrological characteristics

- (2)

- Channel morphology

- (3)

- Engineering structures

- (4)

- Operational management

3.1.4. Wight Assignment of Risk Probability Assessment System

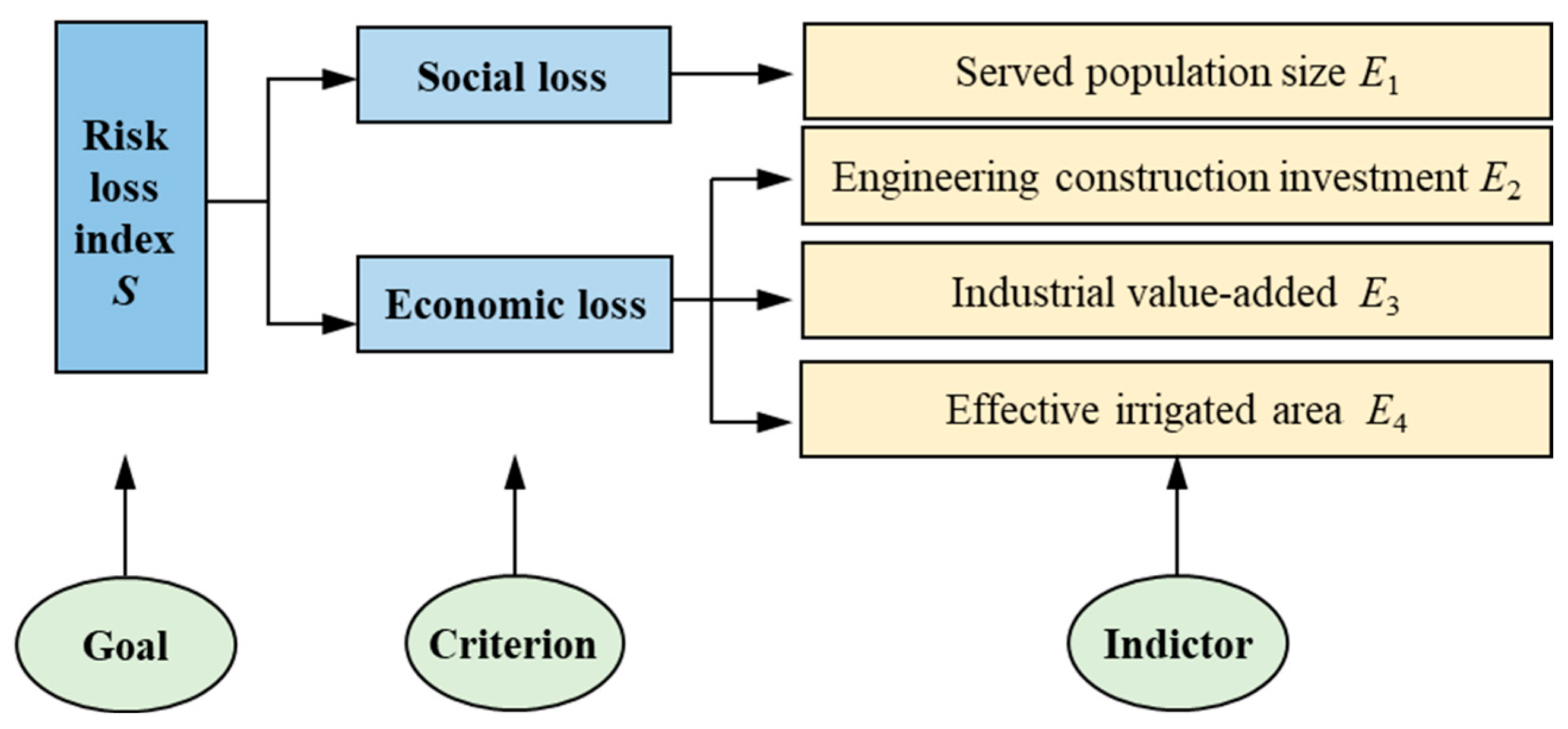

3.2. Risk Loss Index for Water Conveyance Channels

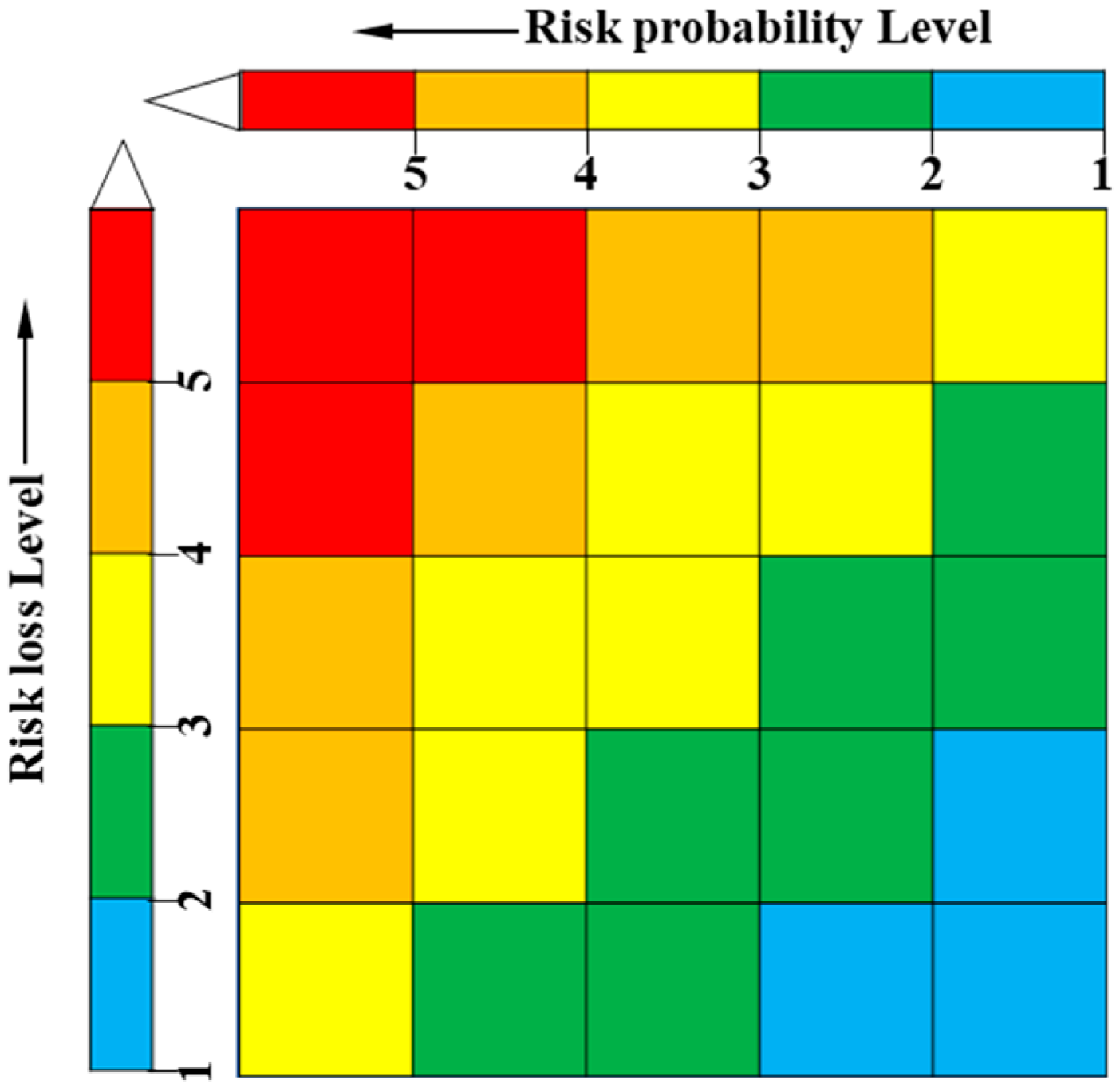

3.3. Integration of Risk Probability and Loss for Comprehensive Assessment

4. Case Application for Water Conveyance Channels in the Yangtze-to-Huaihe Water Diversion Project (Henan Reach)

4.1. Risk Probability Assessment for Water Conveyance Channels

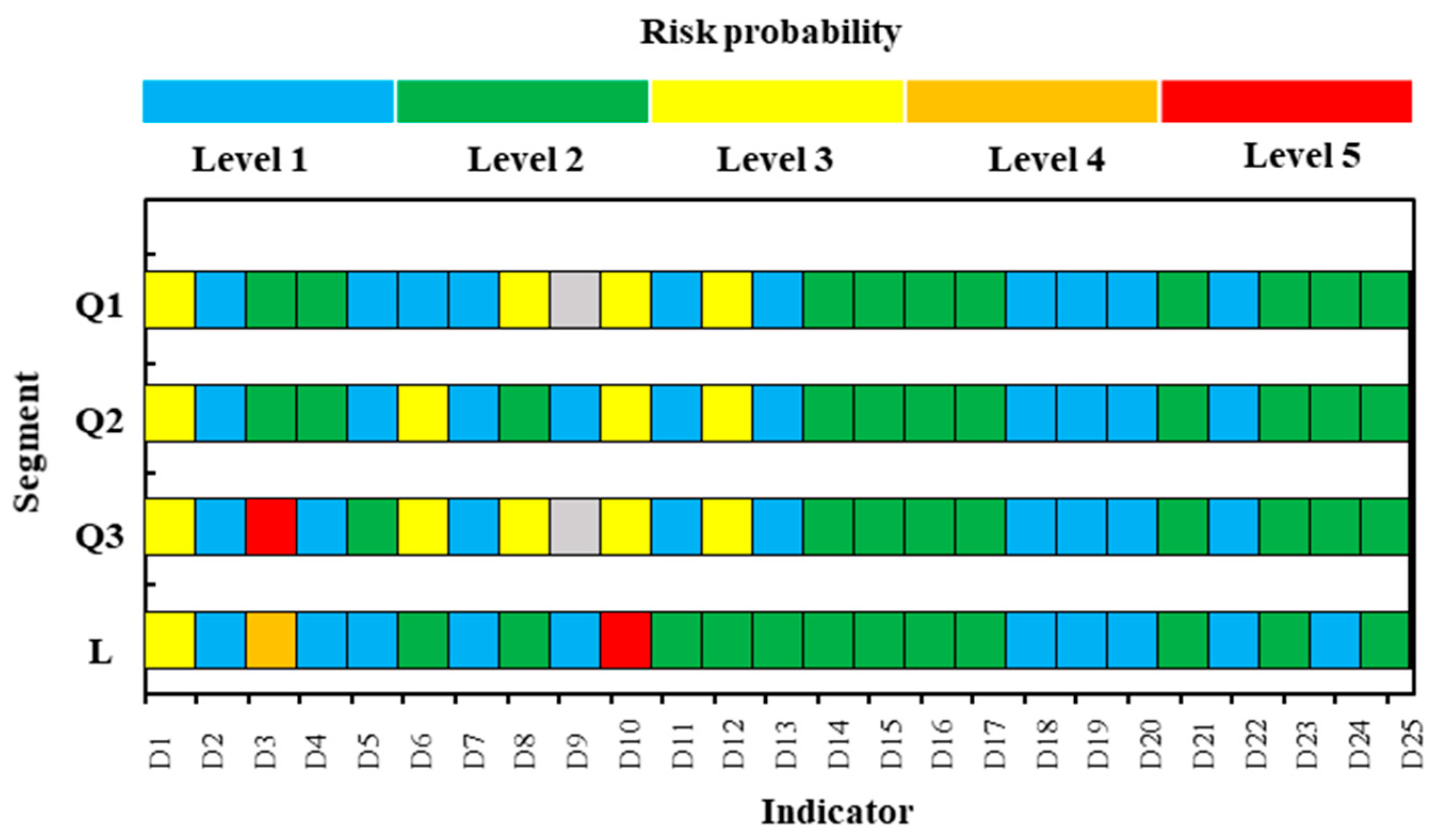

4.1.1. Individual Indicator Values

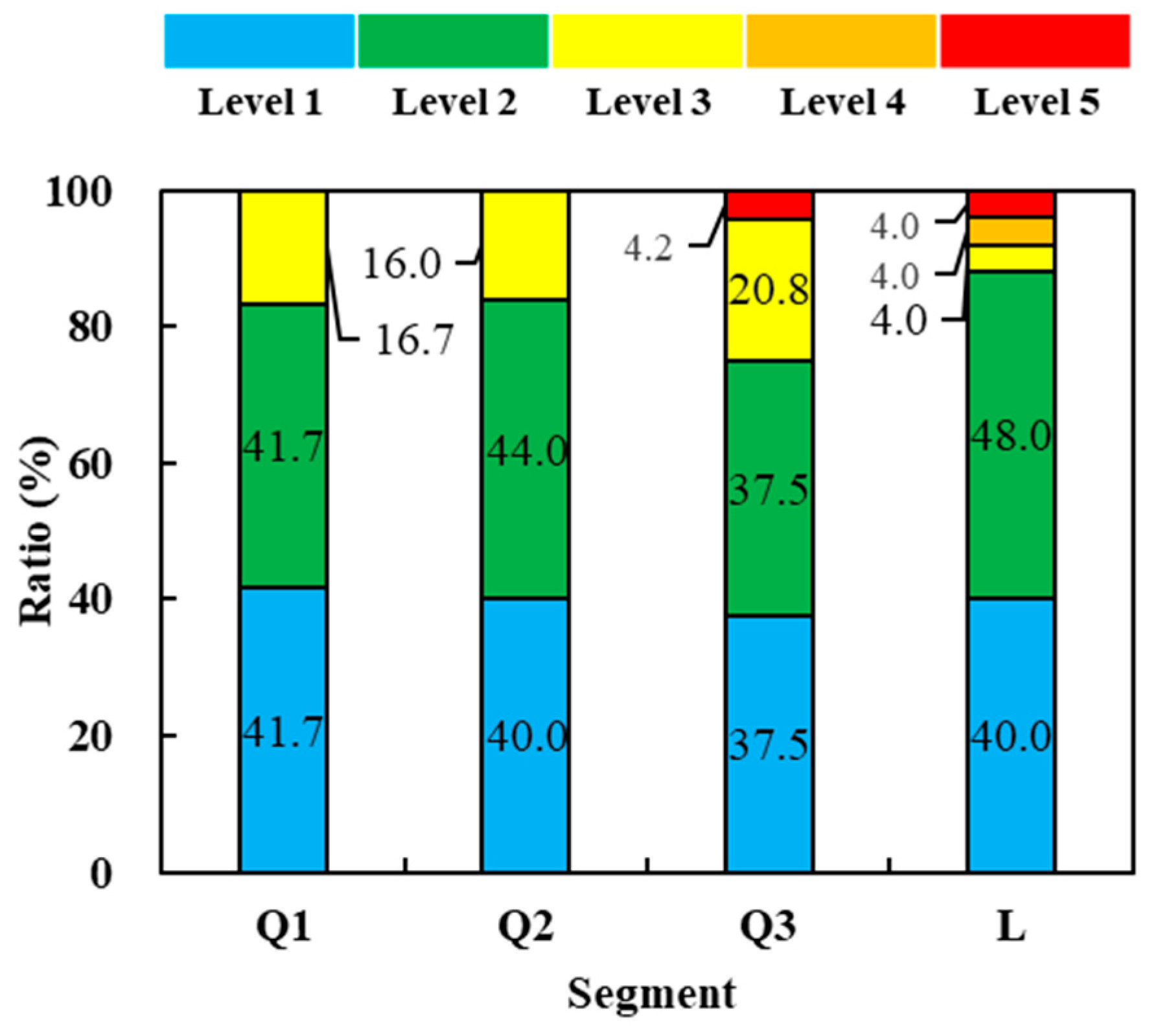

4.1.2. Criterion-Level Analysis

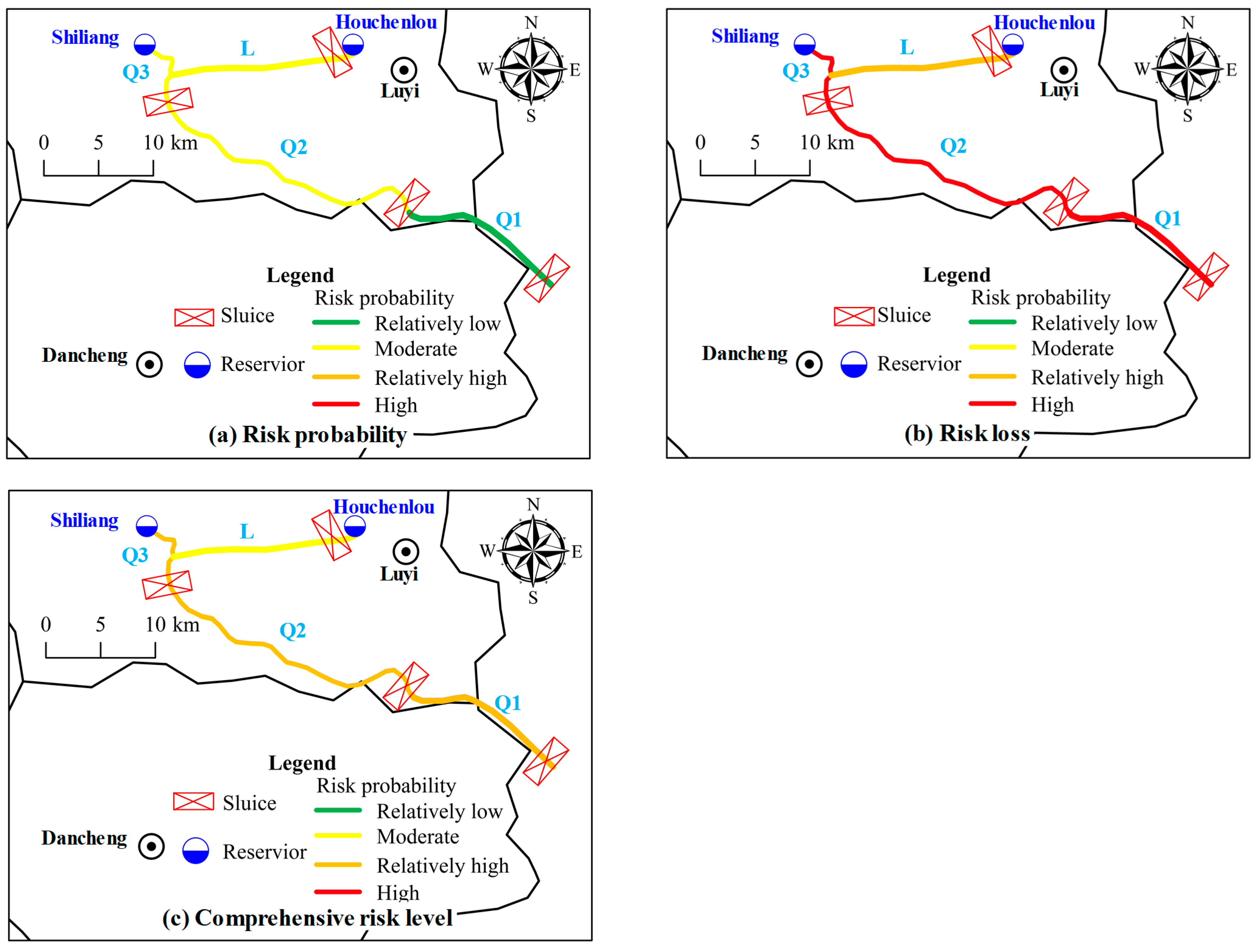

4.1.3. Comprehensive Risk Probability

4.2. Risk Loss Assessment of Water Conveyance Channels

4.3. Comprehensive Operation Safety Risk Level

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Long, Y.; Xu, L.Y.; Lei, X.H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.L.; Li, Y.X. The risk assessment model for water diversion projects based on a fuzzy Bayesian network. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 134053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, G.R.; Shang, W.; Wang, Z.; Langford, J. China’s South-to-North Water Diversion Project Empowers Sustainable Water Resources System in the North. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummu, M.; Guillaume, J.H.A.; De Moel, H.; Eisner, S.; Flörke, M.; Porkka, M.; Siebert, S.; Veldkamp, T.I.E.; Ward, P.J. The world’s road to water scarcity: Shortage and stress in the 20th century and pathways towards sustainability. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, M.; Baldassarre, G.D.; Boegh, E.; Browning, A.; Oki, T.; Tindimugaya, C.; Vairavamoorthy, K.; Vrba, J.; Zalewski, M.; Zubari, W.K. International Hydrological Programme (IHP) eighth phase: Water security: Responses to local, regional and global challenges. Strategic plan, IHP-VIII (2014–2021). In Zbornik Nije Izdan; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.Y.; Dong, F.D.; Lv, G.B.; Wang, Y.S.; Sheng, Y.G.; Cheng, F.; Wang, B. Multiple Correlation Analysis of Operational Safety of Long-Distance Water Diversion Project Based on Copula Bayesian Network. Water 2025, 17, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreide, J.P.G.; Zhu, Q. Comparison of Brazil’s cross-basin water transfer practice and inter-national cases. Water Resour. Hydropower Bull. 2011, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, S.; Haskuee, M.B.; Yazdani, S.; Hayati, B. Investigating the economic impacts of inter-basin water transfer projects with a water- embedded multi-regional computable general equilibrium approach. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 10, 3875–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlner, H. Institutional change and the political economy of water megaprojects: China’s south-north water transfer. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 38, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow-Miller, B. Discourses of deflection: The politics of framing China’s South-North Water Transfer Project. Water Altern. 2015, 8, 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Nickum, J.E. The status of the South to North Water Transfer Plans in China. In Report to United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Reports; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Jiang, B.; Huang, H.; Shen, F. Study on risk factor identification and risk control of transboundary river security. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2018, 49, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, G.; Zhu, X.; Huang, X. Risk analysis of floodwater resources utilization along water diversion project: A case study of the Eastern Route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project in China. Water Supply 2019, 19, 2464–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.D.; Wang, G.; Ren, M.L.; Ding, L.Q.; Jiang, X.M.; He, X.Y.; Zhao, L.P.; Wu, N. Flood Control Risk Identification and Quantitative Assessment of a Large-Scale Water Transfer Project. Water 2021, 13, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, G.; Chiwuikem, C.J.; Yang, Z. Flood risk cascade analysis and vulnerability assessment of watershed based on Bayesian network. J. Hydrol. 2023, 626 Pt A, 130144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.M.; Yin, K. Rainfall Threshold analysis and bayesian probability method for landslide initiation based on landslides and rainfall events in the past. Open J. Geol. 2018, 8, 674–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwu, E.J.; Odanwu, S.E.; Ezewudo, B.I.; Odo, G.E.; Nzei, J.I.; Iheanacho, S.C.; Islam, M.S. Assessment of water quality status using heavy metal pollution indices: A case from Eha-Amufu catchment area of Ebonyi River, Nigeria. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 6, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barco, M.K.D.; Furlan, E.; Pham, H.V.; Torresan, S.; Zachopoulos, K.; Kokkos, N.; Critto, A. Multi-scenario analysis in the Apulia shoreline: A multi-tiers analytical framework for the combined evaluation and management of coastal erosion and water quality risks. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 153, 103665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Xu, G.; Ma, C.; Chen, L. Emergency control system based on the analytical hierarchy process and coordinated development degree model for sudden water pollution accidents in the middle route of the south-to-north water transfer project in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 12332–12342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.H.; Jiang, B.L.; Fu, K.W.; Mao, Y.J. Risk Analysis and Assessment of the Water Conveyance System Operation in the East Route of South-to-North Water Transfer Project. Yellow River 2012, 34, 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Liu, H.D. Safety Risk Assessment of Water Conveyance Channel Operation of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project. Yellow River 2022, 44, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, H.; Wang, Y.Z.; Song, Z.H.; Wang, H.; Fang, J.; Wang, Y.Q. Long-term service risk assessment of pumping station system in the Yangtze-to-Huaihe River Water Diversion Project (Henan Reach). S. N. Water Transf. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 21, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Ye, W.; Ma, F.H. Comprehensive risks assessment of engineering safety for long-distance water transfer projects. S. N. Water Transf. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, F.; Gu, X.W.; He, H.M. Study on eco-safety evaluation index system for Yellow River embankment based on consequence-reverse-diffusion method. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2013, 44, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, F.; Ni, G.H.; He, H.M. Research on safety evaluation of Yellow River embankment based on consequence-reverse diffusion and layered-weight method. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2014, 45, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Danka, J.; Zhang, L.M. Dike Failure Mechanisms and Breaching Parameters. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2015, 141, 04015039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.B.; Yu, M.H.; Wei, H.Y.; Liang, Y.J.; Zeng, J. Non-symmetrical levee breaching processes in a channel bend due to overtopping. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2018, 33, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Kang, T.; Felix, M.L.; Lee, S. A Study to determine the location of perforated drainpipe in a levee for controlling the seepage line. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lei, X.; Long, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Hou, X.; Shi, M.; Wang, P.; Zhang, C.; et al. A novel comprehensive risk assessment method for sudden water accidents in the Middle Route of the South–North Water Transfer Project (China). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, M.; Babel, M.S. Assessment of climate change impact on water diversion strategies of Melamchi Water Supply Project in Nepal. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 128, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maihemuti, B.; Wang, E.; Hudan, T.; Xu, Q. Numerical simulation analysis of reservoir bank fractured rock-slope deformation and failure processes. Int. J. Geomech. 2016, 16, 04015058. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T.H.; Fan, J.Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, J. Risk Assessment of Water Pollution Emergencies for Water Diversion Project Based on Cloud Model: A Case Study on Henan Section of the Yangtze River to Huaihe River Diversion Project. J. Chang. River Sci. Res. Inst. 2024, 41, 48–55+62. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, L.B.; Maddock, T. The Hydraulic Geometry of Stream Channels and Some Physiographic Implications; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1953; Volume 252.

- Leopold, L.B.; Wolman, M.G. River Channel Patterns: Braided, Meandering, and Straight; U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 282-B; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1957.

- Costa, J.E. Effects of agriculture on erosion and sedimentation in the Piedmont Province, Maryland. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1975, 86, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SL/Z 679-2015; Guidelines for Levee Safety Evaluation. Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Luo, R.H.; Huang, J.L.; Zhang, J.W.; Ye, X. Dike safety evaluation based on combined weighting and cloud model. S. N. Water Transf. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 19, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, G.H.; Gao, Y.Q.; Tan, W.X.; Zheng, Z.Z.; Guo, N. Establishment of evaluation index system for modernization of water conservancy project management. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 2013, 33, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. Analytic Hierarchy Process; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.B.; Zhang, Q.; Xia, X.Z. Research progress on safety operation risk analysis of embankment projects. Yellow River 2020, 42, 25–31+35. [Google Scholar]

| Prefecture-Level City | Counties and Districts | Population (×104) | Industrial Value-Added (in Million Yuan) | Effective Irrigated Area (×103 mu) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shangqiu | Liangyuan District | 87.75 | 15,779 | 470.0 |

| Suiyang District | 83.35 | 23,826 | 104.9 | |

| Zhecheng | 86.66 | 9993 | 1090.5 | |

| Xiayi | 101.94 | 12,623 | 1298.8 | |

| Zhoukou | Dancheng | 112.02 | 9671 | 1338.2 |

| Taikang | 123.08 | 12,216 | 1403.4 | |

| Huaiyang | 121.59 | 13,069 | 1191.3 | |

| Yongcheng | 138.14 | 75,134 | 1760.2 | |

| Luyi | 101.57 | 73,775 | 1019.9 | |

| Total | 956.10 | 246,087 | 9677.2 | |

| Prefecture-Level City | Counties and Districts | Domestic Water | Industrial Water | Agricultural Water | Ecological Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shangqiu | Liangyuan District | 49.64 | 28.40 | 66.38 | 8.99 |

| Suiyang District | 47.46 | 42.89 | 14.75 | 8.54 | |

| Zhecheng | 41.44 | 17.99 | 152.56 | 8.88 | |

| Xiayi | 48.74 | 22.72 | 184.30 | 10.44 | |

| Zhoukou | Dancheng | 53.56 | 17.41 | 185.95 | 5.38 |

| Taikang | 58.85 | 21.99 | 195.02 | 5.91 | |

| Huaiyang | 58.14 | 23.52 | 165.54 | 5.84 | |

| Yongcheng | 71.09 | 135.24 | 249.77 | 14.15 | |

| Luyi | 48.57 | 132.80 | 141.73 | 4.88 | |

| Total | 477.49 | 442.96 | 1356.00 | 73.00 | |

| Segment | Discharge (m3/s) | Channel Length (km) | Range * (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 43.0 | 15.10 | 240~15,340 |

| Q2 | 42.0 | 31.61 | 15,340~46,950 |

| Q3 | 9.6 | 0.75 | 46,950~47,700 |

| L | 30.9 | 16.26 | 0~16,260 |

| n | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI | 0 | 0 | 0.52 | 0.89 | 1.12 | 1.26 | 1.36 | 1.41 | 1.46 |

| Judgment Matrices | Weight | CR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | ||

| A | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.006 |

| B2 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0 | ||

| B3 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.001 | |

| B4 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.0006 |

| Goal Layer (Ak) | Criterion Layer (Rk,m) | Weight (ωk,m) | Sub-Criterion Layer (rk,m) | Weight (ωk,m) | Indictor Layer (Rk,m,n) | Comprehensive Weight (ωk,m,n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk probability index A of water conveyance channel | Hydrological characteristics B1 | 0.32 | Hydrological characteristics C1 | 1.00 | Flood characteristics D1 | 0.21 |

| Flow condition D2 | 0.11 | |||||

| Channel morphology B2 | 0.19 | Channel spatial morphology C2 | 0.67 | Crossing structure density D3 | 0.06 | |

| Sinuosity coefficient D4 | 0.03 | |||||

| River regime coefficient D5 | 0.03 | |||||

| Sedimentation risk C3 | 0.33 | Sedimentation intensity D6 | 0.06 | |||

| Engineering structures B3 | 0.28 | Dike structures C4 | 0.28 | Flood standard compliance D7 | 0.04 | |

| Bank stability D8 | 0.02 | |||||

| Revetment integrity D9 | 0.02 | |||||

| Foundation properties C5 | 0.39 | Foundation seepage characteristics D10 | 0.07 | |||

| Foundation compaction degree D11 | 0.04 | |||||

| Construction materials C6 | 0.33 | Body seepage characteristics D12 | 0.06 | |||

| Body compaction degree D13 | 0.03 | |||||

| Operational management B4 | 0.21 | Institutional implementation C7 | 0.21 | Organization completeness D14 | 0.01 | |

| Scheme rationality D15 | 0.01 | |||||

| Operational plan implementation D16 | 0.01 | |||||

| Emergency plan completeness D17 | 0.01 | |||||

| Personnel conditions C8 | 0.29 | Personnel structure suitability D18 | 0.03 | |||

| Personnel technical proficiencyD19 | 0.03 | |||||

| Automation levels C9 | 0.25 | Monitoring automation maturity D20 | 0.02 | |||

| Control automation level D21 | 0.02 | |||||

| Office automation degree D22 | 0.02 | |||||

| Infrastructure status C10 | 0.25 | Material reserve adequacy D23 | 0.02 | |||

| Transport accessibility D24 | 0.02 | |||||

| Communication and power supply D25 | 0.02 |

| Indictor | Basic Index Expression | Scoring Criteria (Corresponding to Risk Levels 1–5) |

|---|---|---|

| Flood characteristics D1 | Excessive flood frequency | None; rare; once; twice; multiple times in recent years |

| Flow condition D2 | Flow path and water level | Smooth and stable; mostly smooth and stable; mostly smooth, with slight fluctuations; some obstructions and noticeable fluctuations; severe obstructions and major disturbances |

| Crossing structure density D3 | Number of crossing structures per kilometer | ) |

| Sinuosity coefficient D4 | Ratio of channel length to straight-line distance | (1.00, 1.05]; (1.05, 1.50]; (1.50, 2.00]; (2.00, 3.00]; (3.00, ) |

| River regime coefficient D5 | Ratio of square root of channel width to average depth | ) |

| Sedimentation intensity D6 | Degree of sediment deposition | Negligible; low; moderate; high; very high |

| Flood standard compliance D7 | Percentage of dike length meeting flood protection standards (%) | (95, 100]; (90, 95]; (85, 90]; (70, 85]; (0,70] |

| Bank stability D8 | Dike stability index (%) | (75, 100]; (50, 75]; (25,50]; (0, 25]; 0 |

| Revetment integrity D9 | Percentage of revetment with damage or uneven surface (%) | (0, 10]; (10, 25]; (25, 50]; (50, 75]; (75,100] |

| Foundation seepage characteristics D10 | Hydraulic conductivity of dike foundation (m/s) | ) |

| Foundation compaction degree D11 | Compaction condition of dike foundation | very dense; dense; moderately dense; locally porous; highly porous |

| Body seepage characteristics D12 | Hydraulic conductivity of dike body (m/s) | ) |

| Body compaction degree D13 | Compaction condition of dike body | very dense; dense; moderately dense; locally porous; highly porous |

| Organization completeness D14 | Management organization degree | Fully complete; mostly complete; partially complete; mostly incomplete; not complete |

| Scheme rationality D15 | Appropriateness and soundness of management and operational schemes | Highly reasonable; reasonable; moderately reasonable; unreasonable; highly unreasonable |

| Operational plan implementation D16 | Operational plans quality | Fully implemented; mostly implemented; partially implemented; minimally implemented; not implemented |

| Emergency plan completeness D17 | Degree to which emergency plans are comprehensive, detailed, and practical for crisis response | Fully complete; mostly complete; partially complete; minimally complete; not complete |

| Personnel structure suitability D18 | Alignment of staff composition with the required roles and responsibilities for safe operation | Very suitable; suitable; moderately suitable; unsuitable; very unsuitable |

| Personnel technical proficiencyD19 | Level of professional skills and expertise of staff in operating and managing the system | High; moderately high; moderate; moderately low; low |

| Monitoring automation maturity D20 | Degree to which monitoring systems are automated and capable of real-time data acquisition | Fully automated; highly automated; partially automated; minimally automated; not automated |

| Control automation level D21 | Extent to which channel operation and regulation are managed through automated control systems | High; moderately high; moderate; moderately low; low |

| Office automation degree D22 | Level of application of digital and automated tools in administrative and management tasks | Comprehensive automation; advanced automation; intermediate automation; basic automation; manual processes |

| Material reserve adequacy D23 | Sufficiency of reserved materials and supplies to meet operational and emergency needs | Sufficient; moderately sufficient; adequate; moderately insufficient; insufficient |

| Transport accessibility D24 | Ease of access to the channel and related facilities via transportation networks | Favorable; acceptable; basic but difficult; severely restricted; inaccessible |

| Communication and power supply D25 | Reliability of communication systems and power supply | Excellent; good; relatively good; basically adequate; unstable |

| Goal Layer (Ak) | Criterion Layer (Rk,m) | Weight (ωk,m) | Indictor Layer (Rk,m,n) | Comprehensive Weight (ωk,m,n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk loss index S of water conveyance channel | Social loss | 0.50 | Served population size E1 | 0.50 |

| Economic loss | 0.50 | Engineering construction investment E2 | 0.07 | |

| Industrial value-added E3 | 0.21 | |||

| Effective irrigated area E4 | 0.22 |

| Indictor | Basic Index Expression | Scoring Criteria (Corresponding to Risk Levels I–V) |

|---|---|---|

| Served population size E1 | Percentage of affected population (%) | (0, 20]; (20, 40]; (40, 60]; (60, 80]; (80, 100] |

| Engineering construction investment E2 | Engineering construction investment per kilometer (million yuan/km) | ) |

| Industrial value-added E3 | Industrial production loss (million yuan) | ) |

| Effective irrigated area E4 | Agricultural production loss (million yuan) | ) |

| Segment | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrological characteristics | 2.34 | 2.34 | 2.34 | 2.34 |

| Channel morphology | 1.50 | 2.16 | 3.17 | 2.34 |

| Engineering structures | 2.03 | 2.03 | 2.03 | 2.51 |

| Operational management | 1.55 | 1.55 | 1.55 | 1.47 |

| Studied Segment | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk probability A | 1.97 | 2.05 | 2.29 | 2.22 |

| No. | Indicator | Assessment Index | Equation | Parameter | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Served population size E1 | Percentage of affected population | is the number of people affected; is total population; | Engineering design information | |

| 2 | Engineering construction investment E2 | Engineering construction investment per kilometer | is engineering construction investment; is construction channel length; | Engineering design information | |

| 3 | Industrial value-added E3 | Industrial production loss | is total industrial water supply; is Water use per unit of industrial value-added; is the assumed affected ratio; | Engineering design information | |

| 4 | Effective irrigated area E4 | Agricultural production loss | is total agricultural water supply; is water use efficiency coefficient; is net irrigation quota production; is acre yield; is grain price per unit weight; is assumed affected ratio. | Engineering design information, Research materials |

| Risk Probability | (4, 5] | (3, 4] | (2, 3] | (1, 2] | (0, 1] | |

| Risk Loss | ||||||

| (4, 5] | Q2, Q3 | Q1 | ||||

| (3, 4] | L | |||||

| (2, 3] | ||||||

| (1, 2] | ||||||

| (0, 1] | ||||||

| Segment | Assessment Indictor | Index Value | Risk Loss Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | E1 | 100% | V |

| E2 | 730 | IV | |

| E3 | 34,000 | IV | |

| E4 | 5300 | IV | |

| Q2 | E1 | 100% | V |

| E2 | 730 | IV | |

| E3 | 34,000 | IV | |

| E4 | 5300 | IV | |

| Q3 | E1 | 100% | V |

| E2 | 730 | IV | |

| E3 | 34,000 | IV | |

| E4 | 5300 | IV | |

| L | E1 | 62.7% | IV |

| E2 | 128 | III | |

| E3 | 18,800 | III | |

| E4 | 2600 | III |

| Segment | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk loss index S | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 3.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jing, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, M. The Risk Assessment for Water Conveyance Channels in the Yangtze-to-Huaihe Water Diversion Project (Henan Reach). Water 2025, 17, 2992. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17202992

Jing H, Wang Y, Wang Y, Xu J, Yang M. The Risk Assessment for Water Conveyance Channels in the Yangtze-to-Huaihe Water Diversion Project (Henan Reach). Water. 2025; 17(20):2992. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17202992

Chicago/Turabian StyleJing, Huan, Yanjun Wang, Yongqiang Wang, Jijun Xu, and Mingzhi Yang. 2025. "The Risk Assessment for Water Conveyance Channels in the Yangtze-to-Huaihe Water Diversion Project (Henan Reach)" Water 17, no. 20: 2992. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17202992

APA StyleJing, H., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Xu, J., & Yang, M. (2025). The Risk Assessment for Water Conveyance Channels in the Yangtze-to-Huaihe Water Diversion Project (Henan Reach). Water, 17(20), 2992. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17202992