Comparative Study on Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Water Consumption Pattern

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

- –

- Extending water protection to all water categories;

- –

- Water management in hydrographic basins;

- –

- Combining emission limit values with environmental quality standards;

- –

- Ensuring that water prices provide adequate incentives to use water resources efficiently;

- –

- The closer involvement of citizens;

- –

- Simplifying water legislation.

1.2. Bottled Water Versus Filtered Water

1.3. Description of Research

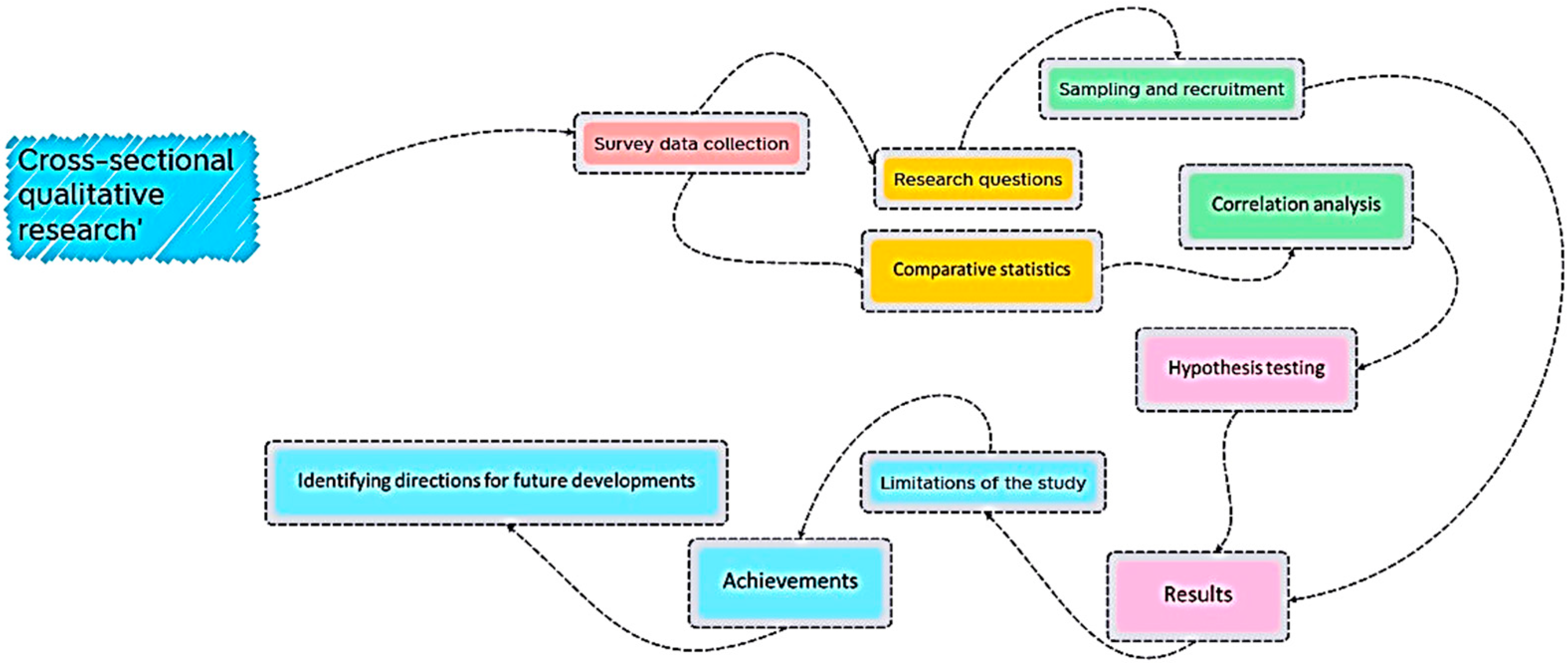

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions and Hypotheses

2.2. Sampling and Recruitment

2.3. Research Methods

3. Results

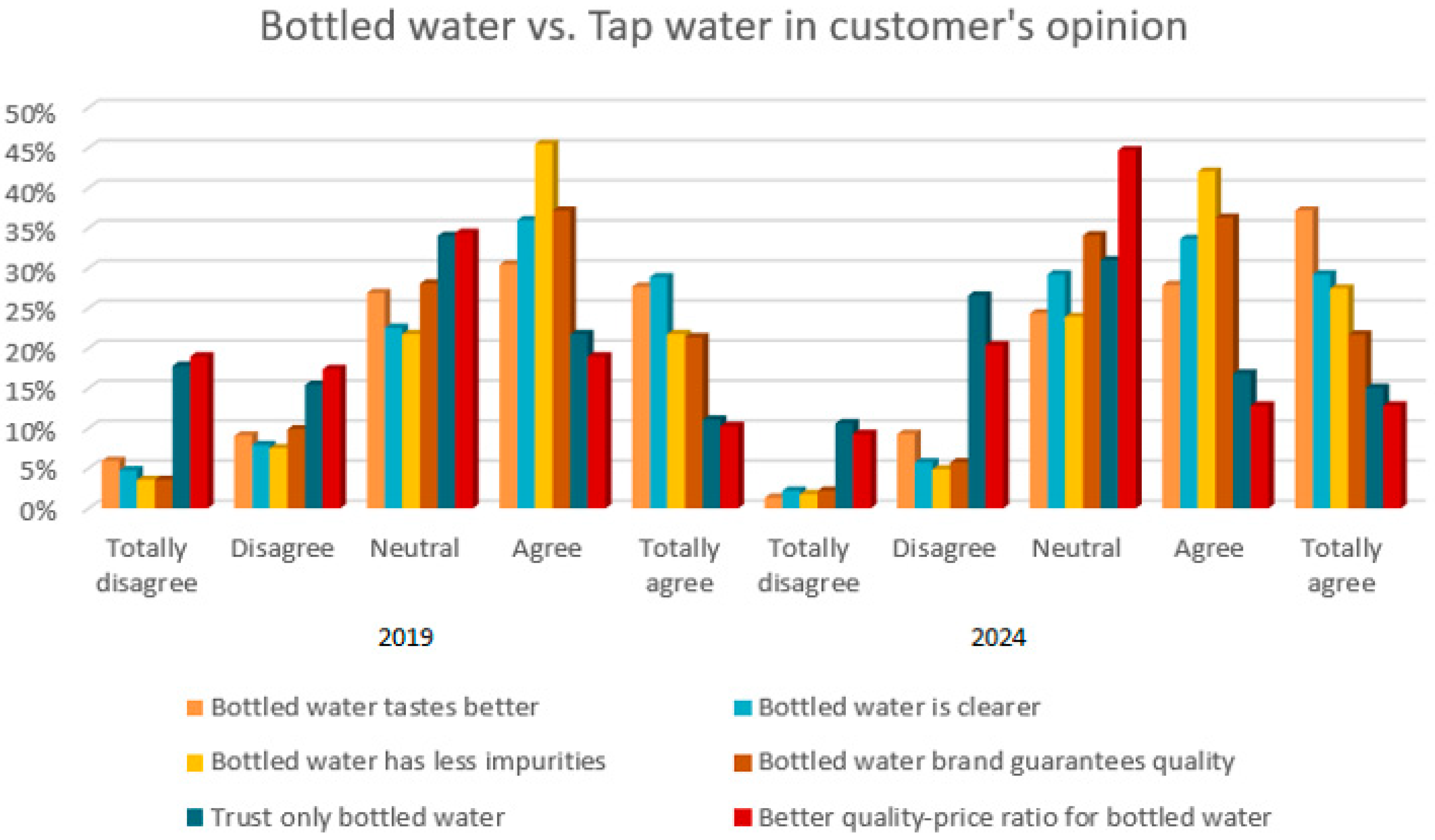

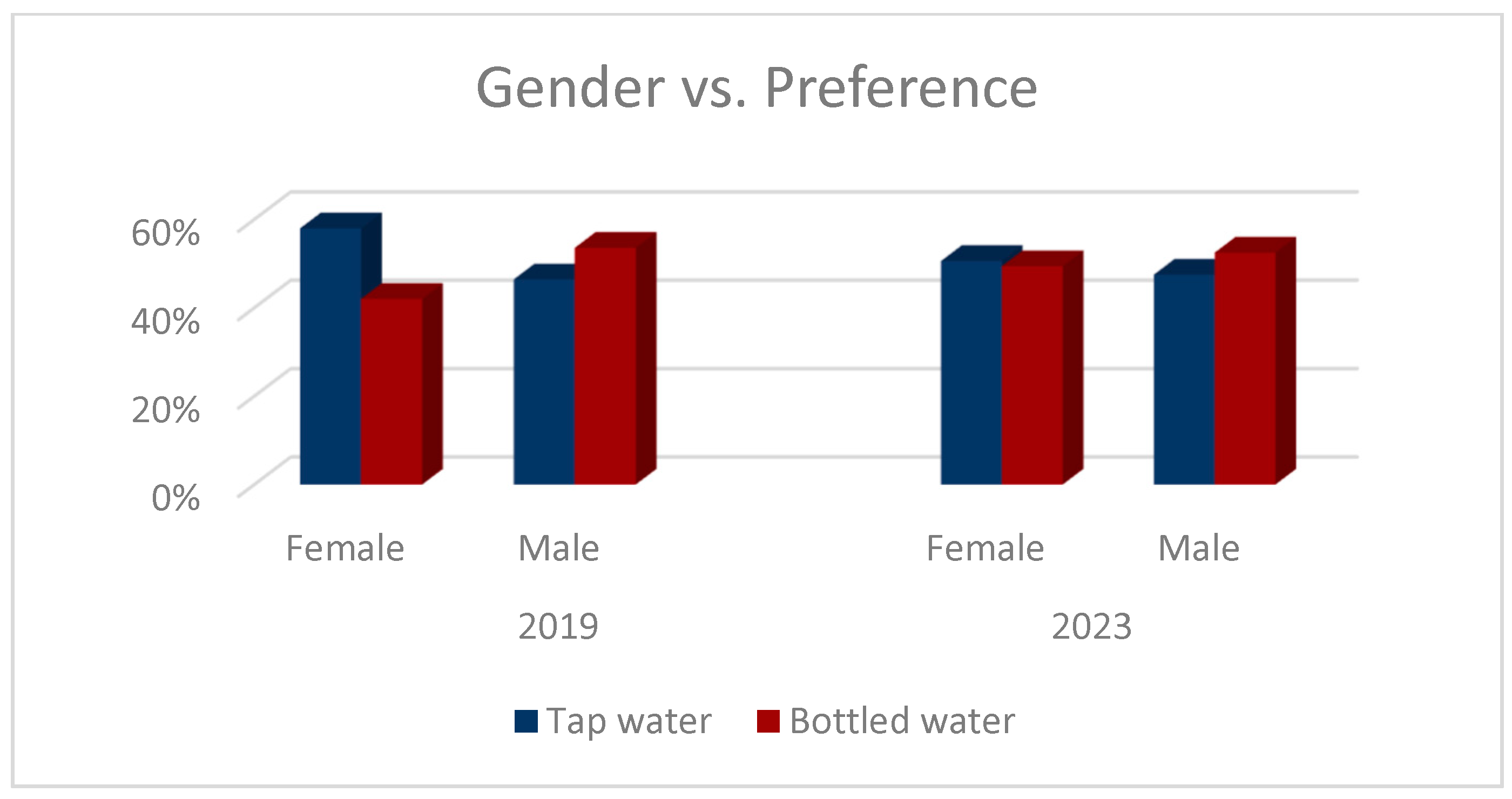

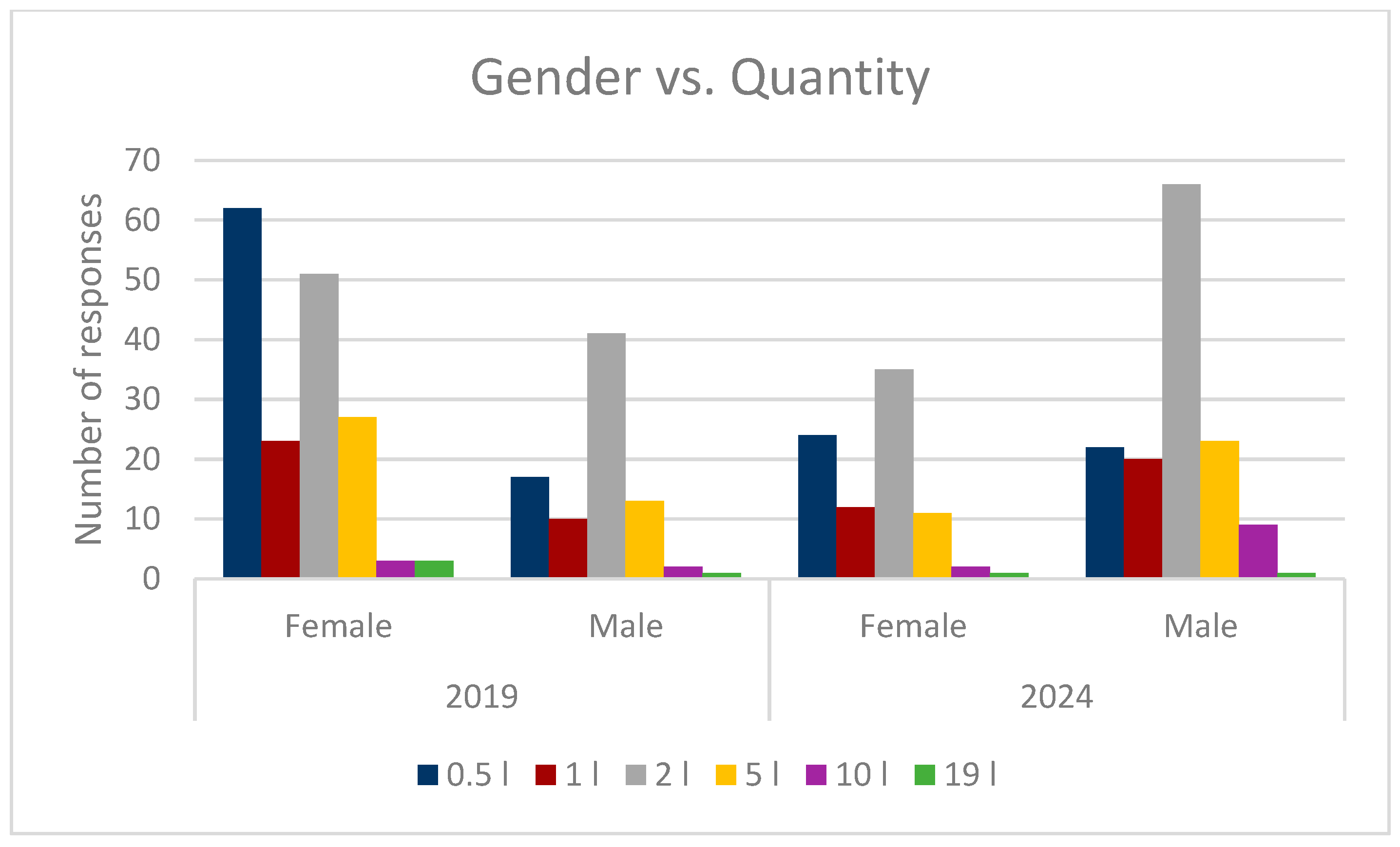

3.1. Comparative Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions, Limitations of Study, and Future Directions for Development

- –

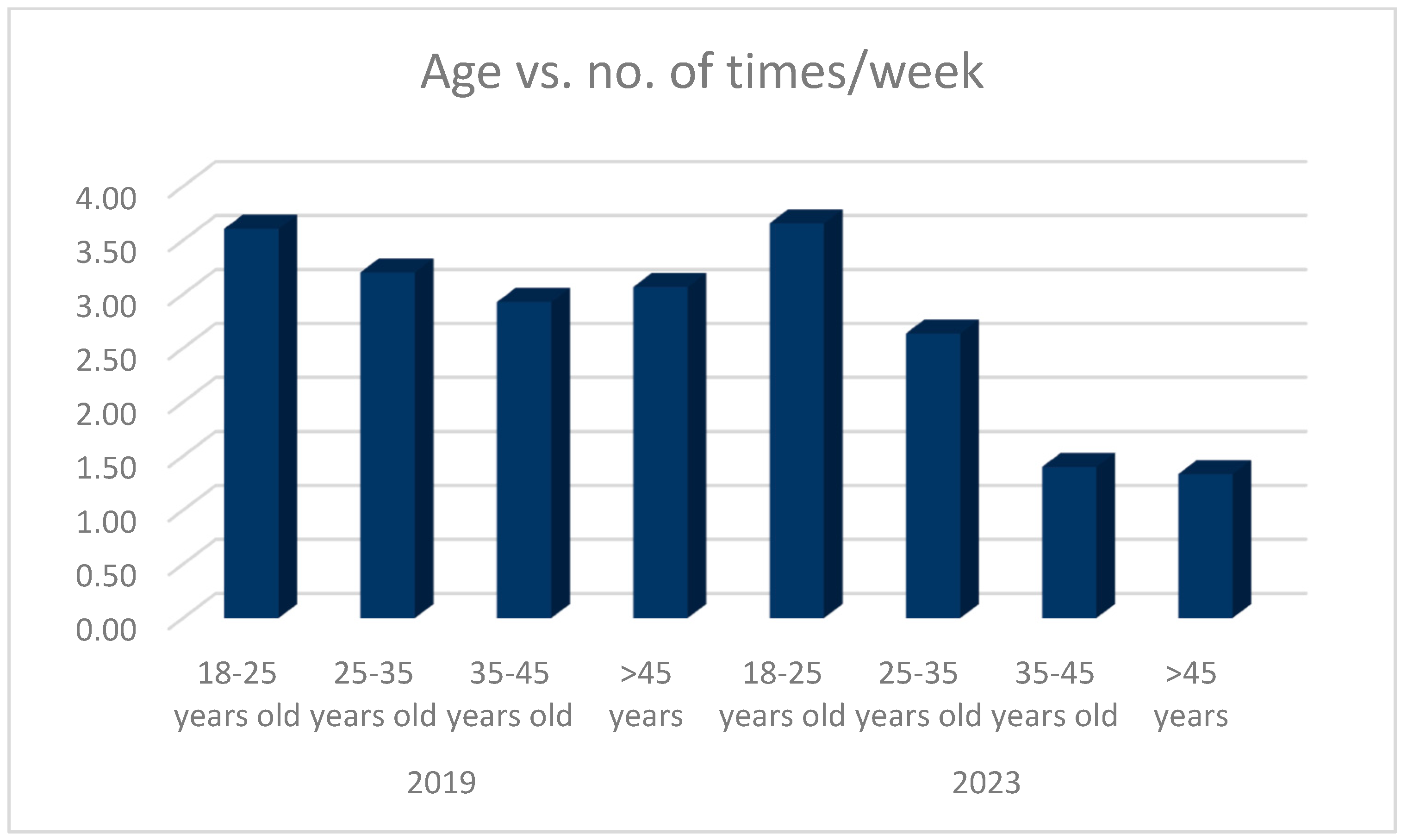

- The average purchase volume per trip rose by 10.4%, and the weekly buying frequency rose by 12.1%;

- –

- The growth was concentrated among women and younger respondents;

- –

- The preference for PET bottles increased by 4%, while the stated tap water use fell by 5%, paralleling a 4.2% drop in the perceived tap water quality;

- –

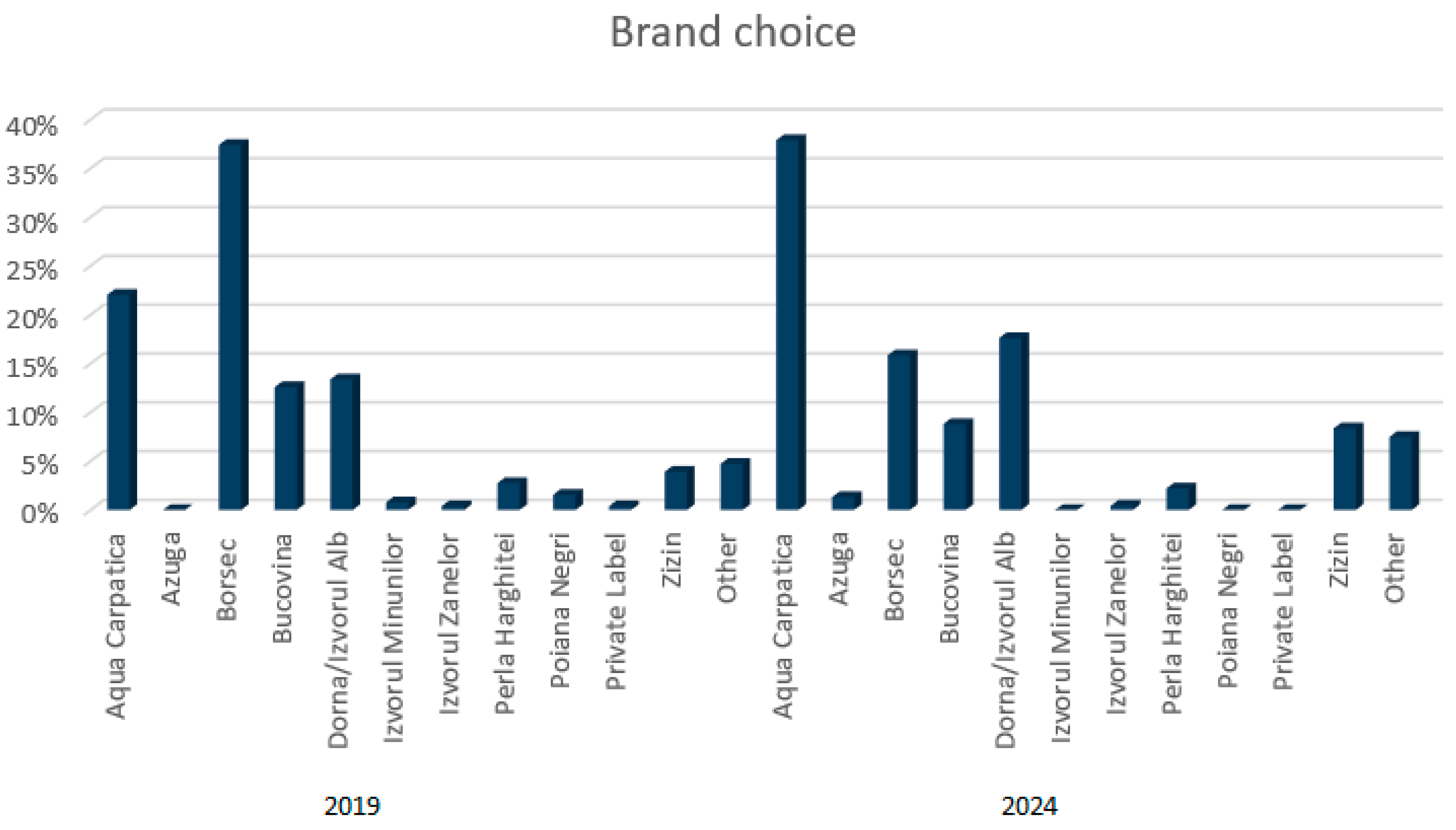

- The brand share shifted: the share for Aqua Carpatica rose to 38%, whereas the share for Borsec fell from 37% to 16%, suggesting that purity-based marketing influences choices across income levels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Consumer Attitudes Regarding Interest in Purchasing Drinking Water Filters Versus Bottled Water in PET Packaging

- I

- Data on respondents.

- E-mail address (optional for those who want to know the results of the study).

- Specify the geographical area from which you come:

Bucharest-Ilfov;

Center;

Northeast;

Northwest;

South Muntenia;

Southeast Dobrogea;

Southwest Oltenia;

West.

- The city where you live:__________________________________.

- Age:

18–25 years old;

25–35 years old;

35–45 years old;

Over 45 years old.

- Status:

Employee;

Unemployed;

Student/Master’s student/Ph.D. student;

Retired;

Household;

Other—please specify:_______________.

- Professional level:

8 classes;

High school;

University studies;

Postgraduate studies;

- Level of net income (in RON):

0–1500;

1500–3000;

3000–4000;

4000–6000;

6000–10,000;

Peste 10,000.

- Marital status:

Married;

Unmarried;;

Married with children;

Unmarried with children.

- Gender:

Female;

Male.

- II

- Data on drinking water preferences and consumption.

- 10.

- What is your water consumption preference?

I prefer to drink water from home (from the public network);

I prefer to drink bottled water.

- 11.

- How many times per week do you consume still bottled water?

not at all;

once a week;

between 1–3 times/week;

between 3–5 times/week;

more than 5 times/week.

- 12.

- What is the amount of still bottled water you consume most frequently?

0.5 L;

1 L;

2 L;

5 L;

10 L;

19 L;

- 13.

- What is the type of packaging in which you buy still bottled water?

still bottled water in glass packaging;

still bottled water in polyethylene terephthalate packaging (PET)

- 14.

- What is the brand of drinking water you purchase most often?

Borsec;

Aqua Carpactica;

Izvorul Alb;

Bucovina;

Dorna;

Perla Harghitei;

Poiana Negri;

Izvorul Minunilor;

Private Label;

Zizin;

Azuga;

Izvorul Zânelor;

Other—please specify:_______________.

- 15.

- To what extent do you agree with the following statements regarding the comparison between still bottled water and the water distributed at home from the public network?

Bottled Water Totally Agree Agree Neutral Disagreement Total Disagreement It tastes much better It has a much clearer appearance It is free of possible impurities The brand I buy from gives me the guarantee of quality I only trust the quality of bottled water The value for money is much better - 16.

- On a scale from 1 to 10 (where 1 represents the worst score and 10 is the best score), how do you rate drinking water quality at your home?

- 1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

.

- 17.

- Consider that it should be improved in terms of its quality?

Yes, it needs significant improvements;

Yes, it needs some improvements;

May need improvement;

I don’t think it needs improvement;

It doesn’t need any improvement.

- III

- Information about the existence of alternatives to the consumption of bottled drinking water.

- 18.

- Do you know some possible alternatives for bottled water other than the one at home?

Yes;

I don’t know, but I want to find out;

I don’t know.

- 19.

- Drinking water filters are a new alternative solution for water consumption and have the role of improving water quality at the level of the domestic user, and thus, consumers’ health. Starting from this basic information, please evaluate the most important features a water filter should contain:

Very Important Important Neutral Important Enough Unimportant Price Durability Efficiency (high degree of filtration and impurities) Possibility of reuse Possibility of recycling Increased degree of innovation (eg: the possibility of ozonation of water, improvement of taste, elimination of watercolor) The material from which it is made Minimizing the impact on the environment - IV

- Raising awareness of water waste and water’s impact on health and determining the intention of users to purchase water filters.

- 20.

- What do you think are the effects of the relationship between the consumption of bottled water in PET packaging and the environment and one’s health?

There is no particular relationship;

It is a relationship without direct consequences on the environment because once the PET packaging become waste, they are thrown in specially designed-places;

There are no negative effects in the short and medium term on consumers’ health;

There are numerous negative effects on the environment and consumers’ health caused by the permanent consumption of PET packaging.

- 21.

- Every year, 400 billion liters of bottled water are consumed, and to bottle it in PET (polyethylene terephthalate) packing, 30 million barrels of oil and 7 times more water are consumed annually to produce a single bottle versus the one being bottled. Based on these aspects, how do you assess the amount of resources used for this process?

I think the amount of resources used is normal;

Resources exist in nature in abundance, so the quantity itself is not a problem;

I can’t properly estimate the amount of resources used;

In the context of sustainable development and circular economy, it is imperative to reduce the amount of resources we use for this process;

Other:________________________________

- 22.

- What is your opinion on purchasing flat water filters? (multiple answers)

It’s just another marketing strategy;

They will only partially solve drinking water quality and health problems;

It represents a viable alternative in the context of the circular economy;

They will significantly improve water quality and, implicitly consumers’ health;

Contributes to stopping water wastage;

It represents a much better alternative to PET packaging from sustainability and health persepctive;

In the context of sustainable consumption, it is necessary to turn our attention to them;

They are important for improving the quality of life.

- 23.

- What would be your choice if you had to decide between buying plain bottled water or purchasing water filters for home water consumption? (multiple answers)

I don’t plan to buy water filters;

I don’t understand why I should buy water filters;

I don’t find it necessary to buy water filters;

If I could find water filters for home consumers on sale, I would buy them;

Yes, I would buy them because I want to stop drinking bottled water in PET bottles, so I can protect the environment and my health;

Yes, I would buy, but in parallel, I would continue to buy bottled water;

I have already switched to this way of consumption, but I still consume bottled water;

I have already switched to this way of consumption and no longer buy bottled water.

References

- Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Allan, R. Water sustainability and the implementation of the Water Framework Directive—A European perspective. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2012, 12, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuijts, S.; Van Rijswick, H.F.; Driessen, P.P.; Runhaar, H.A. Moving forward to achieve the ambitions of the European Water Framework Directive: Lessons learned from the Netherlands. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 333, 117424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, R.J.; Hiscock, K.M. Two decades of the EU Water Framework Directive: Evidence of success and failure from a lowland arable catchment (River Wensum, UK). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geerts, R.; Vandermoere, F.; Van Winckel, T.; Halet, D.; Joos, P.; Steen, K.V.D.; Van Meenen, E.; Blust, R.; Borregán-Ochando, E.; Vlaeminck, S.E. Bottle or tap? Toward an integrated approach to water type consumption. Water Res. 2020, 173, 115578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acarer, S. Abundance and characteristics of microplastics in drinking water treatment plants, distribution systems, water from refill kiosks, tap waters and bottled waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 884, 163866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Z.; Liu, T.; Men, Y.; Li, S.; Graham, N.; Yu, W. Understanding point-of-use tap water quality: From instrument measurement to intelligent analysis using sample filtration. Water Res. 2022, 225, 119205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhib, I.; Uddin, K.; Rahman, M.; Malafaia, G. Occurrence of microplastics in tap and bottled water, and food packaging: A narrative review on current knowledge. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 865, 161274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorigoni, A.; Bonini, N. Water bottles or tap water? A descriptive-social-norm based intervention to increase a pro-environmental behavior in a restaurant. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 86, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveena, S.M.; Ariffin, N.I.S.; Nafisyah, A.L. Microplastics in Malaysian bottled water brands: Occurrence and potential human exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umoafia, N.; Joseph, A.; Edet, U.; Nwaokorie, F.; Henshaw, O.; Edet, B.; Asanga, E.; Mbim, E.; Chikwado, C.; Obeten, H. Deterioration of the quality of packaged potable water (bottled water) exposed to sunlight for a prolonged period: An implication for public health. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 175, 113728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Guan, B. Separation and Identification of Nanoplastics in Tap Water. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 112134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, R.O. Impact of Polyethylene Terephthalate in Different Temperatures and Storage Duration on Some Physicochemical Properties of Drinking Bottled Water. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2022, 43, 3977–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045064 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Zvěřinová, I.; Ščasný, M.; Otáhal, J. Bottled or Tap Water? Factors Explaining Consumption and Measures to Promote Tap Water. Water 2024, 16, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, H.; Garcia, X.; Domene, E.; Sauri, D. Tap Water, Bottled Water or In-Home Water Treatment Systems: Insights on Household Perceptions and Choices. Water 2020, 12, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survey Taken in 2019. Available online: https://forms.gle/oyinVJ7Dxud2zVhb8 (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Surbey Taken in 2024. Available online: https://forms.gle/1AetskBRwpgyVzqo8 (accessed on 15 June 2024).

| Quantity in Liters/Purchase | No. of Times/Week | Water Quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2024 | 2019 | 2024 | 2019 | 2024 | |

| Mean | 2.30 | 2.54 | 3.07 | 3.44 | 6.88 | 6.59 |

| Standard Error | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

| Mode | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| Standard Deviation | 2.83 | 2.71 | 2.31 | 2.34 | 2.37 | 2.41 |

| Sample Variance | 8.03 | 7.36 | 5.34 | 5.49 | 5.63 | 5.83 |

| Kurtosis | 17.86 | 12.36 | −1.59 | −1.65 | −0.02 | −0.42 |

| Skewness | 3.72 | 3.02 | 0.18 | −0.07 | −0.79 | −0.62 |

| Range | 18.5 | 18.5 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 9 |

| Minimum | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum | 19 | 19 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 10 |

| Sum | 582.5 | 575 | 777 | 778 | 1741 | 1489 |

| Count | 253 | 226 | 253 | 226 | 253 | 226 |

| Year | Age | Education Level | Income | Marital Status | Gender | Preference | No. of Times | Quantity | PET | Brand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 2019 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2024 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Education level | 2019 | 0.0877 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2024 | 0.1544 | 1 | |||||||||

| Income | 2019 | 0.4483 | 0.4305 | 1 | |||||||

| 2024 | 0.3832 | 0.1368 | 1 | ||||||||

| Marital status | 2019 | 0.5779 | 0.1184 | 0.4410 | 1 | ||||||

| 2024 | 0.3781 | 0.0960 | 0.2281 | 1 | |||||||

| Gender | 2019 | −0.2660 | −0.1519 | −0.1012 | −0.2546 | 1 | |||||

| 2024 | −0.0749 | −0.0865 | 0.0767 | −0.0791 | 1 | ||||||

| Preference | 2019 | −0.0687 | 0.0367 | 0.0508 | −0.0512 | 0.1093 | 1 | ||||

| 2024 | −0.1526 | 0.0323 | 0.0064 | −0.1500 | 0.0298 | 1 | |||||

| No. of times | 2019 | −0.1392 | 0.0447 | 0.0483 | −0.1428 | 0.1358 | 0.7291 | 1 | |||

| 2024 | −0.2945 | 0.0109 | 0.0096 | −0.1253 | 0.0934 | 0.6623 | 1 | ||||

| Quantity | 2019 | −0.0512 | 0.0333 | 0.1164 | 0.0049 | 0.1291 | 0.5128 | 0.5435 | 1 | ||

| 2024 | −0.0472 | −0.0560 | 0.0768 | −0.1617 | 0.1494 | 0.3086 | 0.4420 | 1 | |||

| PET | 2019 | 0.0593 | −0.0909 | −0.0051 | 0.0230 | 0.0529 | 0.0305 | 0.0779 | 0.0030 | 1 | |

| 2024 | 0.1081 | −0.0183 | 0.0541 | 0.0135 | −0.0556 | 0.0092 | −0.0925 | 0.0538 | 1 | ||

| Brand | 2019 | −0.0790 | 0.0398 | 0.0394 | −0.0031 | 0.0050 | −0.0486 | −0.0081 | 0.1100 | −0.0147 | 1 |

| 2024 | 0.0752 | 0.0262 | 0.0833 | 0.0805 | −0.0279 | −0.0092 | −0.1277 | −0.1127 | 0.0240 | 1 |

| 2019 | 2024 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| Mean | 3.15 | 3.57 | 3.35 | 3.63 |

| Standard Error | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| Median | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Mode | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.48 | 1.35 | 1.46 | 1.43 |

| Sample Variance | 2.2 | 1.81 | 2.14 | 2.05 |

| Kurtosis | −1.43 | −1.18 | −1.28 | −1.2 |

| Skewness | −0.01 | −0.38 | −0.26 | −0.48 |

| Range | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Sum | 533 | 300 | 285 | 512 |

| Count | 169 | 84 | 85 | 141 |

| Two-Sample t-Test Assuming Equal Variances | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2024 | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Mean | 3.57 | 3.15 | 3.63 | 3.35 |

| Variance | 1.81 | 2.20 | 2.05 | 2.14 |

| Observations | 84 | 169 | 141 | 85 |

| Pooled Variance | 2.07 | 2.08 | ||

| Hypothesized Mean Difference | 0 | 0 | ||

| df | 251 | 224 | ||

| t Stat | 2.17 | 1.40 | ||

| P (T<=t), One-Tailed | 0.02 | 0.08 | ||

| t Critical, One-Tailed | 1.65 | 1.65 | ||

| P (T<=t), Two-Tailed | 0.03 | 0.16 | ||

| t Critical, Two-Tailed | 1.97 | 1.97 | ||

| Hypothesis | t | tcrit | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ha2 | t2019 = 1.77 t2024 = 1.40 | tcrit2019 = 1.65 tcrit2024 = 1.66 | p2019 = 0.04 p2024 = 0.08 |

| Ha3 | t2019 = 2.04 t2024 = 10.81 | tcrit2019 = 1.66 tcrit2024 = 1.80 | p2019 = 0.02 p2024 = 1.69 × 10−7 |

| Ha4 | t2019 = 2.29 t2024 = 1.75 | tcrit2019 = 1.65 tcrit2024 = 1.80 | p2019 = 0.01 p2024 = 0.05 |

| Ha5 | t2019 = 2.06 t2024 = 2.26 | tcrit2019 = 1.65 tcrit2024 = 1.65 | p2019 = 0.02 p2024 = 0.01 |

| Ha6 | t2019 = 0.56 t2024 = 1.48 | tcrit2019 = 1.65 tcrit2024 = 1.72 | p2019 = 0.29 p2024 = 0.08 |

| Ha7 | t2019 = −0.08 t2024 = 2.45 | tcrit2019 = 1.65 tcrit2024 = 1.65 | p2019 = 0.46 p2024 = 0.01 |

| Ha8 | t2019 = 0.53 t2024 = 1.68 | tcrit2019 = 1.65 tcrit2024 = 1.65 | p2019 = 0.30 p2024 = 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crișan, H.-G.; Crișan, O.-A.; Șerdean, F.; Bîrleanu, C.; Pustan, M. Comparative Study on Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Water Consumption Pattern. Water 2025, 17, 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17121755

Crișan H-G, Crișan O-A, Șerdean F, Bîrleanu C, Pustan M. Comparative Study on Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Water Consumption Pattern. Water. 2025; 17(12):1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17121755

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrișan, Horea-George, Oana-Adriana Crișan, Florina Șerdean, Corina Bîrleanu, and Marius Pustan. 2025. "Comparative Study on Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Water Consumption Pattern" Water 17, no. 12: 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17121755

APA StyleCrișan, H.-G., Crișan, O.-A., Șerdean, F., Bîrleanu, C., & Pustan, M. (2025). Comparative Study on Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Water Consumption Pattern. Water, 17(12), 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17121755