1. Introduction

Increasing climate extremes and variability are leading to an unprecedented increase in flood risk, as well as in the frequency, intensity, and cost of disasters, causing significant damage to human lives and economic assets. According to recent UN reports, occurrences of flood disasters have more than doubled in the decade since 2000 compared with the decade since 1980 and are the most frequent of all the disaster types in the decade since 2000 [

1,

2]. In the decade since 2000, the number of flood events and the number of people affected were the highest of all disasters, accounting for 44% and 41% of the total, respectively [

2].

In many countries, government agencies are leading the fight against this increasing flood risk through structural and non-structural measures. The construction, maintenance, and renovation of flood-protection infrastructure are examples of the former, while early warning systems, nature-based solutions, monitoring and sharing of flood risk information, multi-stakeholder involvement, and local community participation are examples of the latter [

3,

4]. Given the limited financial and human resources, it is essential to implement the optimal combination of structural and non-structural measures to effectively address flood risks. It is, therefore, crucial to understand the quality and benefits of each measure in order to make an informed decision. However, in contrast to the straightforward evaluation of structural measures, which can be readily quantified through engineering analysis (e.g., comparing the results of hydrological simulations of flood areas before and after infrastructure development on a map), evaluating non-structural measures is frequently challenging. Despite the efforts of numerous studies to examine the effectiveness of diverse non-structural measures (e.g., technical analysis of various devices, use of big data, distribution of questionnaires), a consensus-based evaluation methodology at the international level remains elusive [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Moreover, there are differences in previous studies regarding non-structural measures. While there are many studies on early warning, hazard maps, community participation, etc., as a lot of data are available, there are few studies on capacity development for flood-fighting corps, which is the target of this study.

1.1. Flood Fighting with Local Community

Flood fighting is widely practiced as a main non-structural measure in various flood events. During flood events, flood-fighting corps typically perform flood-fighting work to prevent flood overtopping, water infiltration, and levee erosion. Typical flood-fighting work includes the construction of temporary structures and barriers made of sandbags, rocks, and other materials to prevent infrastructure failure caused by external forces of flood water. Previous studies have shown that the majority of flood-fighting structures were sufficiently robust to serve a temporary role effectively [

12,

13,

14,

15].

With growing recognition that local community participation is crucial to disaster response [

3,

4], the local community will likely play a more significant role than the military or professional rescues in flood fighting. In Japan, for example, flood fighting has historically been conducted at the community level, and the roles and responsibilities of local communities and municipalities in flood fighting are clearly defined in the Flood Fighting Act (enacted in 1949 and most recently revised in 2023) [

16].

Mie Prefecture, the area of this study, experienced the most significant level of typhoon in history (the Ise Bay Typhoon) in 1959. The typhoon affected approximately 320,000 people and resulted in 1211 fatalities, with a total of 1.53 million affected people and 5098 fatalities across all the affected prefectures. The disaster had a significant impact on residents and became a catalyst for enhancing community disaster prevention. Since then, the area has experienced continuous floods, and the local community has shown a high level of commitment to flood fighting [

17].

1.2. How Can the Capacity for Flood Fighting Be Developed?

Flood fighting is more than just placing sandbags; the corps must be on standby, respond to orders, work together, and report to the authorities. To perform well in these activities, which are not part of their routine but are required in the rare event of a disaster, regular training is essential. Furthermore, all of these activities also require good collaboration with other organizations with whom they do not normally work. Previous studies have highlighted the challenges of collaboration among the many organizations involved in disaster response. These studies suggest that new communication technologies and systems can be utilized to address these challenges with analysis from a technical perspective. However, they seem to lack analysis from the perspective of experts who use these technologies in actual flood responses [

18,

19,

20,

21].

The development of flood-fighting corps’ abilities must be achieved through well-designed training that incorporates the aforementioned comprehensive viewpoints. Few studies have evaluated flood response training, and they have shown several limitations. These training methods were online or table-top, and their discussion was not thorough because it was difficult to obtain objective and qualitative data [

22,

23,

24]. A significant amount of field training and exercises have been performed worldwide. However, these events have often been publicized without an evaluation showing how well they work.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of field exercises in enhancing the capabilities of flood-fighting corps and other organizations. To achieve this goal, feedback from participants in a large-scale exercise conducted in Japan in 2024 was collected and analyzed. The exercise simulated the actual flood-fighting operations, showcasing the operational phases from initial standby to completion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Exercise Venue

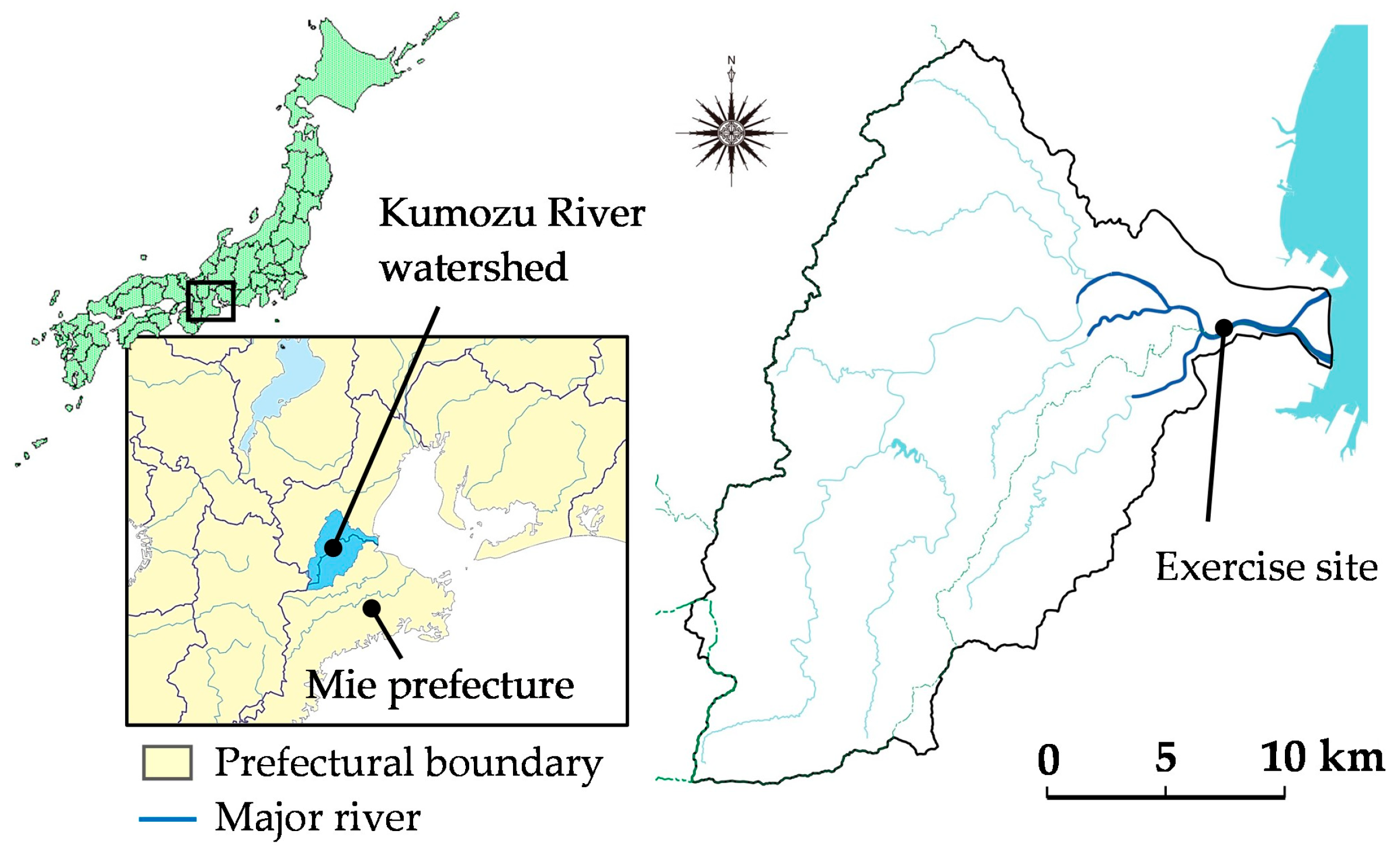

The Kumozu River is 55 km long, and its watershed covers an area of 550 km

2, with a population of approximately 90,000 people living in the watershed (

Figure 1). Land use in the watershed includes 55% mountain and forest, 34% agricultural, and 11% urban, and major transportation networks, such as national highways, national roads, and railways, pass through the watershed. The watershed has historically experienced repeated floods, with the largest recorded flood event occurring in 1959, the Ise Bay Typhoon, when 25.13 km

2 of land was inundated and 3053 houses were damaged. The most recent flood, in 2017, did not affect any houses but inundated 4.19 km

2 of land [

25]. Geographic Information System (GIS)-based flood hazard maps simulated at a 25 m resolution have been created and published for this area [

26], and many residents are aware that the area is prone to flooding.

2.2. Design of the Exercise

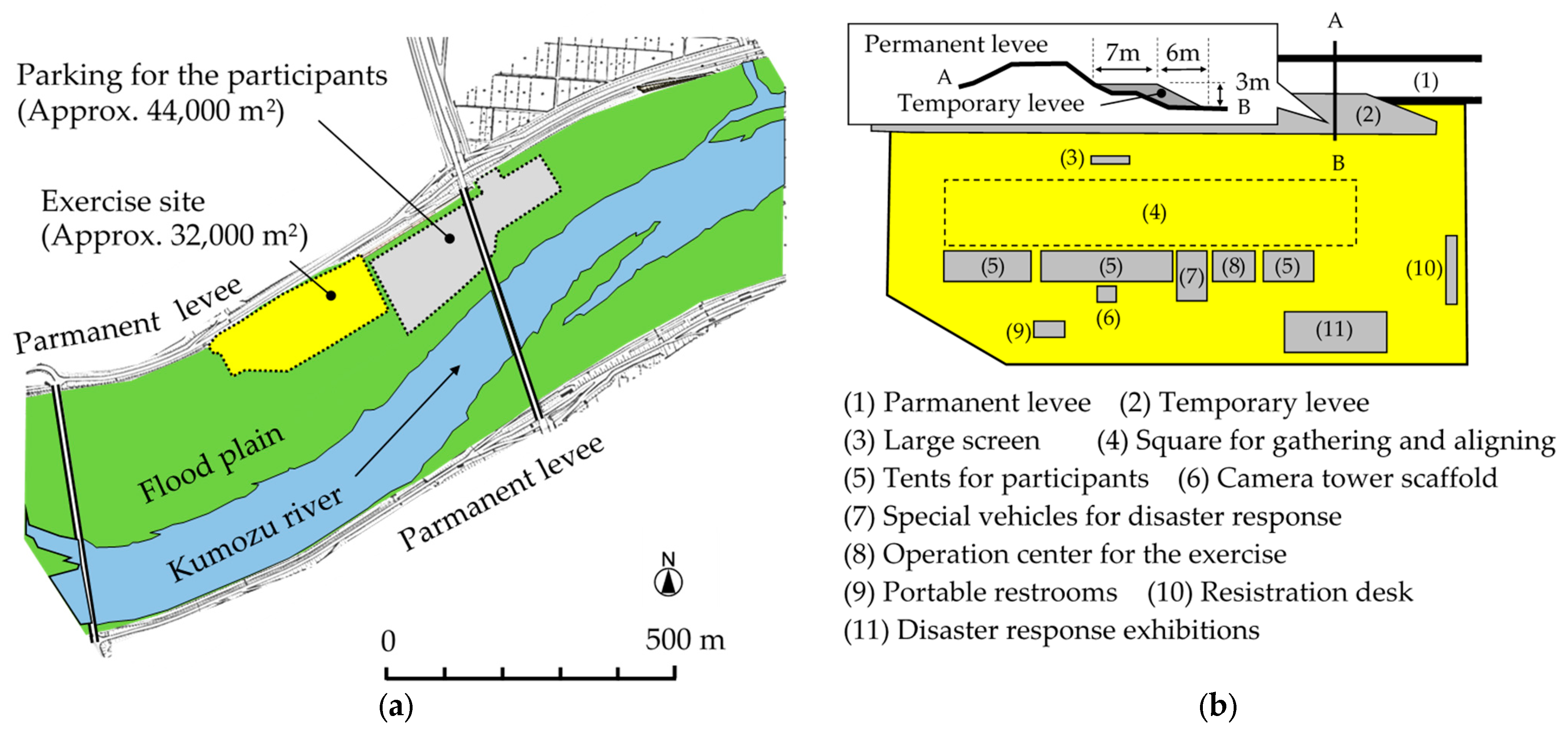

The exercise was designed based on the following protocols: demonstrating flood-fighting techniques, involving major participants from the preparatory phase of the exercises to create the exercise program, conducting the exercises before the Japanese flood season in June, and limiting the duration to two hours to reduce the burden on participants. The exercise was conducted from 9:00 am to 11:00 am on Sunday, 19 May 2024, at a 32,000 m

2 temporary set-up site on the floodplain of the Kumozu River.

Figure 2 shows the layout of the exercise site, which was set up by arranging a temporary levee made of earth for flood-fighting demonstrations alongside the permanent levee on the river with a length of 200 m and a height of 3 m, a square for gathering and aligning the participants, tents for the participants and guests, a large screen for viewing the exercise (W6400 mm × H3600 mm), and the operation center. A total of 1025 people participated in the exercise, including 485 participants from organizations that perform flood-fighting work; 240 invited guests who observed the exercise, representing key national and local stakeholders, including the Governor of Mie Prefecture and mayors, 141 local residents who observed the exercise, and 159 logistics staff who prepared the exercise site layout and supported the exercise operations. The personal information of these participants was not used or disclosed in this study.

The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, Japan (MLIT) took the lead in organizing the exercise, serving as the managing body of the river area, including the exercise site, and as the responsible authority for flood response on a national scale. The entire program of the exercise was captured by professional movie camera crews and projected live on a large screen. The movie was also broadcast live to YouTube for national viewing (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZqKEdWHDvTY (accessed on 1 April 2025)). The purpose of inviting so many guests and preparing the large screen and YouTube broadcast was to allow the guests and public, who are taxpayers and potential flood victims, to observe the exercise. This allowed them to see how flood fighting can save their lives and properties.

Table 1 lists the participants who played a key role in the exercise. Most of the members in these organizations live or work near the Kumozu River and are expected to contribute to fighting floods. The participants have shared information on the natural/social characteristics of the Kumozu River, historical flood-prevention activities, regional knowledge, and the value of the exercise at the preparatory meetings. Some organizations have worked together during small floods, but few have worked together on large flood events, like the scenario in this exercise. The organizations’ lack of experience working together created significant challenges during the months-long preparation for the exercise. It also highlighted the importance of such a large-scale exercise, as a similar lack of experience could have serious consequences in future flood events.

The principal programs of the two-hour exercise, selected by the authors, are listed in

Table 2. The flood-fighting corps and other participating organizations prepared and demonstrated six types of flood-fighting structures (see

Figure 3) and six supportive flood-fighting operations (see

Figure 4) around the temporary levee. The programs of the exercise were finalized following detailed discussions between the exercise organizers and participating organizations.

Each demonstration of the exercise was conducted concurrently, with an introductory statement provided by Prof. Jun Kawaguchi, the second author, and an MLIT official at the outset of each event.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Structured interviews were conducted with the 18 key participating organizations listed in

Table 1 to obtain their views on the effectiveness of the exercise. Many previous studies attempted to evaluate disaster preparedness and awareness [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] and collected the necessary data in the form of feedback from large groups of people using questionnaires and interviews. Therefore, it was decided that the data in this study would be collected through interviews designed with reference to the previous studies.

The criteria for the 18 interviewees were as follows:

The interviewees were selected from among all the participating organizations based on their attendance at the preparatory meeting and their actual demonstrations during the exercise.

The authors obtained their consent on the condition that the full interviews would be recorded, their feedback would only be used for anonymous analysis, and the personal information (name, age, gender, and original occupation) of individual participants from each organization would not be collected or disclosed.

Since MLIT was both a major participant and organizer of the exercise, it was not selected as a source for interviewees to avoid bias in the analysis.

The interviewees were first asked to express their concerns regarding flood fighting and then to describe how the exercises helped to alleviate these concerns. This approach enabled us to evaluate the effectiveness of the exercises by linking the concerns to the solutions that alleviated them and to address the data reliability issues associated with the anonymous nature of interview surveys, as indicated in previous research. Moreover, the evaluation encompasses not only the day of the exercise but also the preparation phase that spanned the preceding several months.

The following four questions were posed to the interviewees:

What are the technical and administrative concerns that your organization faces in responding to a large-scale flood event?

In terms of alleviating your concerns, did you find the preparation phase of the exercises beneficial? Were there any points with which you were dissatisfied?

In terms of alleviating your concerns, did you find the day of the exercises beneficial? Were there any points with which you were dissatisfied?

What was the impact on your organization of being observed by numerous guests and the public on a large screen and on YouTube during the day’s activities?

All the interviews were conducted by the first author between July and September 2024 in person. Each interview lasted between 30 and 50 min and was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim, resulting in a transcript of 42,500 Japanese characters (equivalent to 21,250 words in English).

The recorded transcript was processed and analyzed in accordance with the KJ method [

36,

37], as outlined below:

The authors divided the transcript into phrases with independent meanings and extracted key phrases from them that were relevant to the effectiveness of the exercise.

The first author created categories by aggregating similar key phrases and assigned each category a short title. Subsequently, the first author outlined the rationale behind the categories to the second author, seeking his approval. The second author did not participate in the interviews, except for one observation. The second author’s involvement in the agreement process ensured that the first author’s preconceived notions were eliminated and that the categories were created with as much objectivity as possible.

Once the categories had been created, they were reorganized as three diagrams through consultation between the first author and the second author to illustrate their interrelationships. The evaluation of the large-scale field exercise was then discussed based on the diagrams.

Potential bias may be introduced in the data collection and analysis because all the interviews and initial categorization were conducted by the first author alone. To minimize this potential bias, the second author thoroughly reviewed the audio data of the interviews and the transcript in its approval process. The researchers attempted to make the analysis as quantitative as possible by counting the number of key phrases and using categorization. However, the data from qualitative interviews limit the analysis in a quantifiable manner.

3. Results

3.1. Interview Result 1: Technical and Administrative Concerns in Flood Fighting

Table 3 provides an overview of the six categories created from the 38 key phrases extracted from the interview transcript related to technical and administrative concerns that the organizations face in responding to a large-scale flood event.

A total of 10 of the 18 organizations responded that they were apprehensive about collaborating with other organizations in a large-scale flood. Given that they frequently operate independently in normal circumstances, they have limited experience working with other organizations that have different cultural backgrounds and responsibilities. They have a list of emergency contacts, but there seems to be a psychological barrier to reaching out to organizations they do not usually work with.

Eight organizations indicated that they encountered challenges in making decisions about how to keep their members safe during a flood response. Additionally, nine organizations stated that they lacked the experience to respond to real floods. These two issues are interrelated, and when including the organizations that responded to both, a total of 11 organizations expressed concern about their ability to respond to a real flood while keeping their members safe, showcasing the skills acquired through training.

Five organizations indicated that there is a shortage of personnel in their flood-fighting corps, especially in areas with small populations and a high proportion of elderly people. In contrast, five organizations expressed confidence in their ability to respond to minor floods if they were acting alone. The police were the only organization to indicate that they had no concerns about collaborating with other organizations during major floods, as they are well-versed in responding to various emergency situations as part of their daily duties.

3.2. Interview Result 2: Benefits Gained with Exercise

Table 4 provides an overview of the four categories related to the benefit gained with the exercise created from the 35 key phrases extracted from the interview transcript.

A total of 11 of the 18 organizations were excited to see and learn the actions and equipment utilized by other organizations. This should provide them with valuable insight into the capabilities of other organizations, which would, in turn, reinforce their confidence and reflection.

In disaster response exercises, it is crucial to provide participants with a realistic environment that simulates real-world flood fighting. The fact that 11 organizations indicated that they were able to gain a realistic understanding of flood-fighting situations may underscore the benefits of this exercise in this respect. Given the number of organizations and programs involved in the exercise, the operation was also large-scale and complex. This also underscored that participants were able to gain realistic experience in flood fighting.

Seven organizations indicated that building personal relationships with other organizations was beneficial. During the preparation phase, several in-person meetings were held with the representatives of the organizations, allowing them to interact and facilitate the preparation process. This was believed to help overcome the psychological barriers to collaborating with other organizations.

Six organizations expressed satisfaction with the opportunities to clarify and address flood-fighting issues during the preparation phase prior to demonstrating them in the exercise. On the day of the exercise, participants were required to give demonstrations in front of other participants and numerous guests. Therefore, they must have conducted thorough preparations to prevent any potential failures. This preparation process undoubtedly served as an invaluable training opportunity for the participants.

3.3. Interview Result 3: Dissatisfactions with the Exercise

Table 5 provides an overview of the five categories related to the participants’ dissatisfaction with the exercise created from the 32 key phrases extracted from the interview transcript.

As a point of dissatisfaction related to the aforementioned benefit of building personal relationships, 8 of the 18 organizations were disappointed by the lack of actual collaboration opportunities to demonstrate in the exercises. Most of the demonstrations were performed independently, which many considered a missed opportunity despite working side-by-side with other organizations.

Another point of dissatisfaction related to the aforementioned benefit of seeing and learning about other organizations’ actions and the equipment was the insufficient time allowed to gain a deeper understanding of the other demonstrations, as noted by eight organizations. Some organizations reflected that they had been overly focused on their own demonstrations, while others commented that the overall schedule of the exercise was busy, and they did not have time to learn about the other organizations.

Seven organizations pointed out the absence of a realistic background setting as a prerequisite for the exercise. The anticipated damage that is expected in flood fighting has specific signs, such as water seepage and sand boiling. However, since these signs were not displayed on the exercise site, the realism of each demonstration was consequently compromised.

Four organizations indicated that it would have been beneficial if more residents had participated in the exercise and demonstrations. These respondents were aware that this exercise was designed for flood-fighting experts, but they also emphasized the importance of raising residents’ awareness to facilitate smooth flood fighting. They noted that participation in such a large-scale exercise has a significant impact on residents rather than just watching YouTube broadcasts.

The various operational errors pointed out by the five organizations should be utilized as a reference for future exercise planning.

3.4. Interview Results 4: Impacts of Being Observed During the Exercise

Table 6 provides an overview of the four categories related to the impact of being observed during the exercise created from the 32 key phrases extracted from the interview transcript.

A total of 15 of the 18 organizations responded that the exercise and their own flood-fighting contributions were effectively publicized through the observation of numerous guests and the use of YouTube broadcasts. Furthermore, five organizations responded that they recognized the importance of investing in public relations. These two categories indicated that the participating organizations recognized the importance of publicizing their contribution to flood fighting. While the individual activities of each organization may not frequently receive public or media attention, larger-scale exercises tend to attract more interest. In this respect, the majority of the organizations expressed gratitude to the organizer for the considerable investment of resources into the public relations of the exercise.

Nine organizations were delighted that the participants were so enthusiastic about the exercises, particularly given the large number of spectators. It is believed that the sense of maintaining engagement and alertness in front of a large audience fostered enthusiasm among the participants and enhanced the effectiveness of the exercise.

Three organizations regretted the low number of residents who observed the exercise in person. Poor transportation options prepared by the organizer for the residents and unfortunate weather contributed to this low turnout.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall

Previous studies that have sought to evaluate the effectiveness of exercises identified the challenges associated with data acquisition and the limitation of the analytical approach due to the anonymous nature of the surveys [

22,

23,

24]. In order to overcome these difficulties, this discussion first selected three critical concerns and then formulated potential solutions based on the positive and negative feedback provided by participants. These solutions were designed to alleviate the selected concerns. Finally, the discussion linked the solutions to an evaluation of the effectiveness of the exercise. As both the concerns and the positive and negative feedback were articulated from the participants’ professional point of view, this approach allows for consistent discussions to be held in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the exercises.

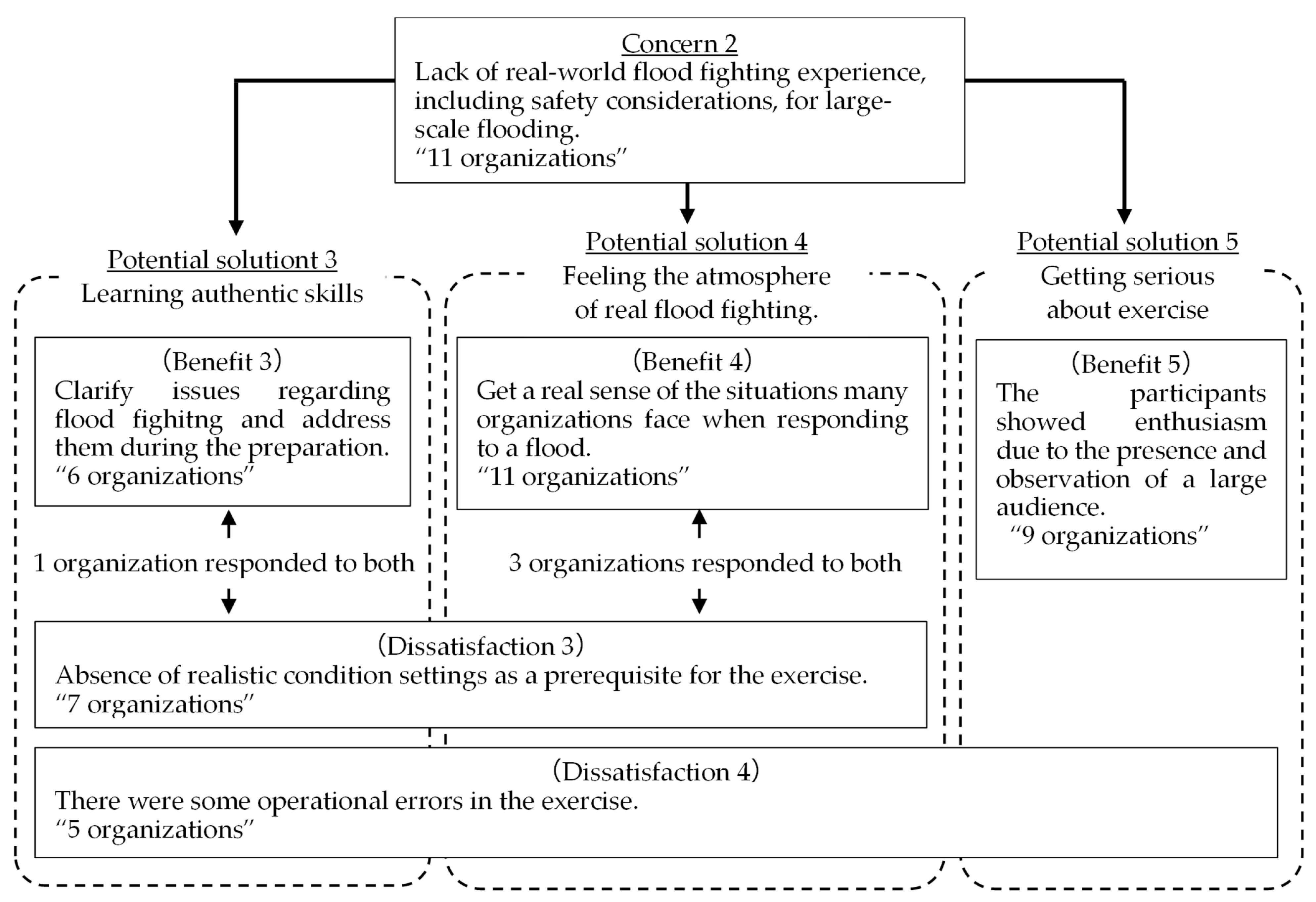

4.2. Strengthening Inter-Organizational Collaboration in Flood Fighting

This discussion revealed how the exercise helped to strengthen inter-organizational collaboration by suggesting two potential solutions to the first concerns regarding poor collaboration with other organizations. It is believed that the findings were achieved thanks to the large-scale exercise involving a large number of organizations. The specific discussion proceeded in accordance with the diagram shown in

Figure 5 and

Table 7.

Previous studies that discussed the challenge of inter-organizational collaboration found that the advancement of communication technology and the improvement in information flow structure could facilitate enhanced collaboration [

18,

19,

20,

21]. On the other hand, the results of our interview survey identified two potential solutions: “Building relationships with other organizations” and “Learning about other organizations”. Shown in

Figure 5 are Benefits 1 and 2 (the participants had the opportunity to physically contact other organizations, extracted from

Table 4) and Dissatisfaction 1 and 2 (that the amount of physical contact did not fully meet the participants’ expectations, extracted from

Table 5), that comprised the potential solution columns, as well as the number of respondents for each.

Furthermore, as shown in

Table 7, a considerable proportion of participants responded to both the benefit and the dissatisfaction of Potential Solution 1, showing a strong link between the two. This indicates that to enhance the viability of Potential Solution 1, it would be advisable to address the dissatisfaction in a manner aligned with the benefit by providing tangible collaboration opportunities. For example, additional programs that multiple flood-fighting corps could collaborate on to deliver materials, fill sandbags, and build larger structures while also fostering a stronger personal relationship with organizations can be incorporated into the exercise.

A similar discussion could be conducted regarding Potential Solution 2. However, since the proportion of participants who responded to both the benefit and the dissatisfaction and the link between the two was somewhat low, it would be advisable to enhance the visibility of Potential Solution 2 to address the dissatisfaction not only in a manner aligned with the benefit by giving participants more time to see other demonstrations and their equipment but also by introducing other types of programs. For example, as one interviewee suggested, a more extensive exhibition can be displayed at the exercise site to explain the demonstrations of the participating organizations in detail.

The potential solutions discussed in this subsection appear to be more conventional than those found in previous studies. However, this approach does not replace the solutions that focus on communication systems. Rather, it is thought that a higher level of effectiveness can be achieved by integrating both approaches if adequate data can be obtained to discuss this integration in a future study. These solutions seem feasible for building capability in flood fighting because they do not conflict with external factors such as the policies of the respective organizations and hardly increase the physical burden or cost of the participants in improving the exercise.

4.3. Designing an Exercise to Reflect Real-World Flood-Fighting Conditions

This discussion revealed how the exercise provided opportunities for learning skills and experiences by suggesting three potential solutions to the second concern regarding the lack of real-world flood-fighting experiences. Unlike the previous discussion, which reflected the scale of the exercise, the design of the exercise programs was the key factor here. The specific discussion proceeded in accordance with the diagram shown in

Figure 6 and

Table 8.

A previous study conducted a literature review to analyze the transfer of knowledge and skills acquired during training to an actual disaster response. One of the findings indicated that engaging in physical simulation of the actual situation, rather than relying on classroom-based training, is an essential component of training [

36]. The results of our interviews are in line with these findings, and they also identified three more detailed potential solutions: “Leaning authentic skills”, “Feeling the atmosphere of a real flood fighting”, and “Getting serious about exercise”.

Figure 6 shows Benefits 3, 4, and 5 (that the participants were able to seriously develop their skills in an environment that closely resembled real flood fighting, extracted from

Table 4 and

Table 6) and Dissatisfactions 3 and 4 (that the simulation of the environment was not sophisticated enough for the participants, extracted from

Table 5) formulated the potential solution columns, as well as the number of respondents for each.

In contrast to the discussions in

Table 7, the proportion of participants who responded to both the benefits and the dissatisfaction was low, showing weak links between them. This indicates that in order to address the dissatisfaction, there is no need to align with the benefits. Instead, an alternative approach is required that focuses on the dissatisfaction while leaving the benefits as they are. For example, the detailed background and conditions for each demonstration can be predetermined and presented to the participants and the guests. In addition, visible signs that could cause damage, such as a water leak from the levee, can be displayed on the exercise site to help everyone realize the threat and the need for countermeasures.

The organizers did not initially anticipate Benefit 5, and the considerable number of participants expressing interest in it came as an unexpected outcome. In the context of an exercise for capacity development, it is crucial to instill a sense of maintaining engagement and alertness in all participants, including those at the most junior levels. However, given that the exercise is merely a simulation, this can often be challenging to achieve. The fact that many participants were able to perform their demonstrations with a serious attitude while being observed, even though such a situation did not appear to be a real flood, was considered a positive outcome of the exercise.

Although not directly linked to the benefits, some operational errors pointed out by participants (Dissatisfaction 4) have been shown to negatively impact exercise quality. However, it is crucial to recognize that these errors can also occur in actual flood fighting and to address them in a composed and deliberate manner rather than simply regretting them as failures. The discrepancy between the plan and operation, or the work difficulties in confined spaces, as referenced in

Table 5, is inevitable in both exercises and real disaster responses. Rather than attempting to eliminate these discrepancies, it is essential to develop leadership capable of calmly giving the next direction when they occur.

These solutions may be influenced by external factors such as weather on the day of the exercise. In addition, feasibility should be carefully considered when improving the exercise, as it is technically and financially challenging to simulate a large-scale water leak at the exercise site.

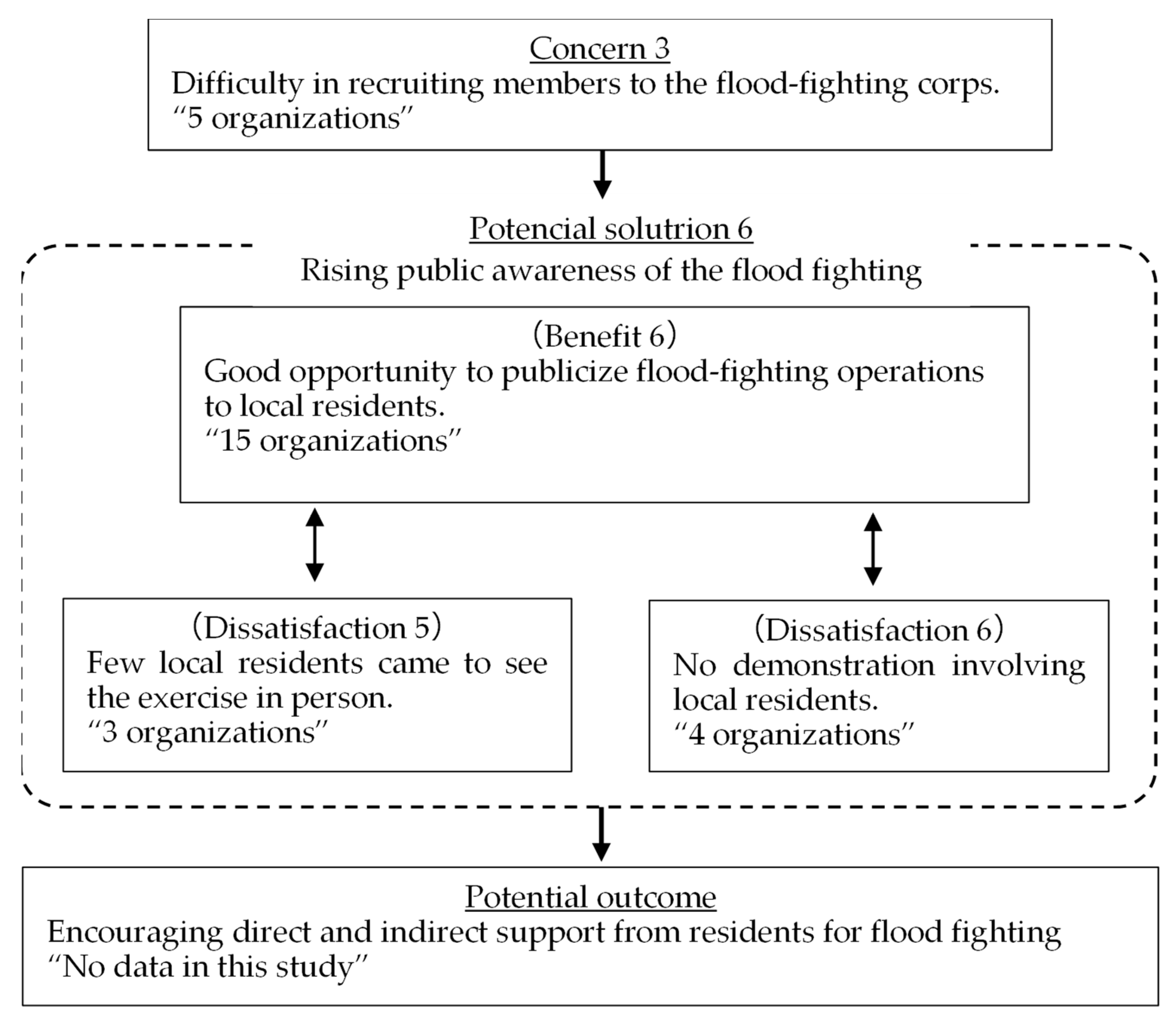

4.4. Raising Public Awareness of Flood Fighting and Encouraging Public Support

This discussion revealed how the exercise raised public awareness of flood fighting from the participants’ point of view by suggesting a potential solution to the third concern regarding the difficulty in recruiting members of the flood-fighting corps. In contrast to the previous two discussions, public observation as an external factor of the exercise was an important factor here. The specific discussion proceeds in accordance with the diagram shown in

Figure 7.

In Japan, the number of personnel engaged in flood fighting is declining annually. The national total number in 2021 dropped by 34% compared to where it was 50 years ago despite a 12% increase in the total population over the same period [

38]. In response to the third concern, which is also a nationwide issue, the results of our interview identified Potential Solution 6: “Rising public awareness of the flood fighting”.

Figure 7 shows Benefit 6 (a good opportunity for public relations extracted from

Table 6) and Dissatisfactions 5 and 6 (which reflect the reduced involvement of local residents, extracted from

Table 5 and

Table 6) and formulated the Potential Solution 6 column, as well as the number of respondents. Previous studies have evaluated the strategies used for raising public and community awareness about disaster prevention. One key area of focus is leveraging social media to reach the broader public [

39,

40,

41]. Another area of focus is engaging the public and community in the development of disaster-related policies and the implementation of countermeasures [

42,

43,

44].

Using YouTube broadcasts is an effective method for raising public awareness, as evidenced by previous studies and feedback from the participants in our exercise. Conversely, previous research has also underscored the importance of choosing appropriate topics and targets for each phase of a disaster event when sending messages to promote public awareness through social media [

39,

40,

41]. Many organizations, including this exercise organizer, have struggled with effectively managing the aforementioned media campaigns, resulting in less-than-desired success.

The lack of direct resident involvement, due to the low priority given to the preparation by the organizer, may have been a missed opportunity to further raise public awareness. In future exercises, the organizer should consider transportation and souvenirs to encourage residents to join the exercise. On the other hand, the organizer must also prioritize resident safety, including their uniforms and distance from heavy machinery during the exercise. It should be noted that the more residents who join, the higher the cost and risk, which may be a challenge in terms of feasibility.

It is noteworthy that the number of respondents indicating the benefit of the good opportunity for public relations was considerably higher than that of respondents indicating concern regarding the difficulty in recruiting members. This suggests that the participants expected the public to acknowledge their contributions to flood fighting, which would, in turn, elicit admiration for them. It was hoped that this external factor would result in direct and indirect support not only for their flood-fighting work but also for their daily business from the public. However, no reliable data were obtained in our interview, as this hypothesis was beyond the scope of this study. Further study is required to discuss this hypothesis.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study show that the large-scale exercise for flood-fighting corps and relevant organizations strengthened inter-organizational collaboration, developed authentic capabilities in a simulated real-world flood-fighting environment, and raised public awareness of flood fighting. In this exercise, the participants are believed to have developed their abilities to work smoothly with other organizations and to demonstrate high-level skills in real emergency situations. In addition, they might have a positive outlook on the human resource sustainability of their respective organizations. The scale of rivers in Japan and other regions varies, and the larger the river, the more organizations and experts are needed to respond to floods. In addition, the approach to flood fighting must be adapted to the characteristics of each river. However, the three results of this study are universally applicable to the flood fighting at any scale and can be used well in similar exercises in other regions.

On the other hand, given the limitations of our exercise, there were also some shortcomings to each achievement. However, they only affected the level of capacity development that should have been gained and did not have an independent negative impact on the exercise or capacity development. Instead, they were also recognized as concrete and valuable improvement options that will enhance the preparation and conduct of future exercises.

The majority of the achievements obtained through the exercise could only have been attained under the conditions of a large-scale exercise involving multiple organizations and extensive public relations efforts. Each participating organization would not have been capable of conducting such an exercise independently. The significance of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, which is responsible for the flood response on a national scale, integrating organizations with diverse cultural backgrounds and responsibilities, and organizing such large-scale exercises was also highlighted.

Although improving future exercises by referring to the suggestions that this study presented is not theoretically difficult, practical considerations, such as time constraints, venue limitations, and the burden on the exercise director and participants, will inevitably lead to limitations. There is no perfect exercise or other way to achieve a preferable balance of benefits and costs based on each exercise situation to achieve more effective flood-fighting capacity development for each participating organization.

In addition, evaluating the long-term effects of capacity development through pre- and post-exercise evaluation, including establishing a method for quantifying participants’ skill levels, is also a challenge. As time passes, the effects will diminish. Evaluating the long-term effects over time and maintaining or strengthening the effects will also be an issue requiring a resolution in future research.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, T.T.; Writing—review & editing, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Akeshi Okumura for his contribution to leading the preparation and conduct of the field exercise and facilitating interviews with the key participating organizations. The authors would also like to thank the interviewees, other participants, and the logistics staff for their contributions to the success of the field exercise.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Concept paper of the Interactive dialogue 3: Water for climate, resilience and environment—Source to sea, biodiversity, climate, resilience and disaster risk reduction. In Proceedings of the United Nations 2023 Water Conference, New York, NY, USA, 22–24 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED); United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). The Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years (2000–2019); UNDRR: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the United Nations Conference on the Midterm Comprehensive Review of the Implementation of the Objectives of the International Decade for Action, “Water for Sustainable Development”, 2018–2028. In Proceedings of the United Nations 2023 Water Conference, New York, NY, USA, 22–24 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Summary of the High-Level Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly on the Midterm Review of the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. In Proceedings of the High-Level Meeting of the Midterm Review of the Sendai Framework, New York, NY, USA, 18–19 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Quansah, J.E.; Engel, B.; Rochon, G.L. Early Warning Systems: A Review. J. Terr. Obs. 2010, 2, 24–44. [Google Scholar]

- Segoni, S.; Piciullo, L.; Gariano, S.L. Preface: Landslide early warning systems, monitoring systems, rainfall thresholds, warning models, performance evaluation and risk perception. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 3179–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeier-Klose, M.; Wagner, K. Evaluation of flood hazard maps in print and web mapping services as information tools in flood risk communication. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2009, 9, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xafoulis, N.; Kontos, Y.; Farsirotou, E.; Kotsopoulos, S.; Perifanos, K.; Alamanis, N.; Dedousis, D.; Katsifarakis, K. Evaluation of Various Resolution DEMs in Flood Risk Assessment and Practical Rules for Flood Mapping in Data-Scarce Geospatial Areas: A Case Study in Thessaly, Greece. Hydrology 2023, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Debele, S.E.; Sahani, J.; Rawat, N.; Marti-Cardona, B.; Alfieri, S.M.; Basu, B.; Basu, A.S.; Bowyer, P.; Charizopoulos, N.; et al. Science of. Nature-based solutions efficiency evaluation against natural hazards: Modelling methods, advantages and limitations. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.H.; Johnson, C.; Lizarralde, G.; Dikmen, N.; Sliwinski, A. Truths and myths about community participation in post-disaster housing projects. Habitat. Int. 2007, 31, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraheni, I.L.; Suyatna, A. Community Participation in Flood Disaster Mitigation Oriented on The Preparedness: A Literature Review. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1467, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, J.L.; Ward, D.L. Evaluation of temporary flood-fighting structures. E3S Web Conf. 2016, 7, 03017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkard, F.; Pratt, T.C.; Ward, D.L.; Holmes, T.L.; Kelley, J.R.; Lee, L.T.; Sills, G.L.; Smith, E.W.; Taylor, P.A.; Torres, N.; et al. Flood-Fighting Structures Demonstration and Evaluation Program: Laboratory and Field Testing in Vicksburg, Mississippi; U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center: Vicksburg, MS, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman, S.N.; Dupuits, E.J.C.; Havinga, F. The effects of flood fighting and emergency measures on the reliability of flood defences. In Comprehensive Flood Risk Management; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1583–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Zeng, W.; Gao, X.; Ren, Y. Analysis of air-inflated rubber dam for flood-fighting at the subway entrance. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2023, 16, e12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Japan. Flood Fighting Act. e-Gov Portal. Available online: https://elaws.e-gov.go.jp/document?lawid=324AC0000000193 (accessed on 26 June 2024). (In Japanese)

- The Cabinet Office of Japan. Report on 1959 Ise Bay Typhoon; The Cabinet Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2008. (In Japanese)

- Oden, R.V.N.; Militello, L.G.; Ross, K.G.; Lopez, C.E. Four Key Challenges in Disaster Response. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2012, 56, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras-Coch, A.; Navarro, J.; Sans, C.; Zaballos, A. Communication Technologies in Emergency Situations. Electronics 2022, 11, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, S.; Sutton, P.D.; Sreenan, C.J.; Brown, K.N. Cognitive radio for disaster response networks: Survey, potential, and challenges. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2014, 21, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharosa, N.; Lee, J.; Janssen, M. Challenges and obstacles in sharing and coordinating information during multi-agency disaster response: Propositions from field exercises. Inf. Syst. Front. 2010, 12, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, A.E.; Mayhew, A.; Baker, S.D.; Mayedwa, M.; Saunders, C.J. Exploring Flood Response Challenges, Training Needs, and the Impact of Online Flood Training for Lifeguards and Water Safety Professionals in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.H.; Chang, Y.L.; Kao, C.; Kang, S.C. The effectiveness of a flood protection computer game for disaster education. Vis. Eng. 2015, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y. Research on Emergency Rescue of Urban Flood Disaster Based on Wargame Simulation. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2018, 46, 1677–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan (MLIT). The River Development Plan in Kumozu River; MLIT: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. (In Japanese)

- The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan (MLIT). The Hazard Map in Kumozu River. Available online: https://www.cbr.mlit.go.jp/mie/disaster/river-disaster/inundation/kumozugawa-top.html (accessed on 1 April 2025). (In Japanese)

- Apronti, P.T.; Osamu, S.; Otsuki, K.; Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G. Education for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR): Linking Theory with Practice in Ghana’s Basic Schools. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9160–9186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.C. Exploring community risk perceptions of climate change—A case study of a flood-prone urban area of Taiwan. Cities 2018, 74, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, B. Role of organizations in preparedness and emergency response to flood disaster in Bangladesh. Geoenviron. Disasters 2020, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerens, R.J.J.; Tehler, H. Scoping the field of disaster exercise evaluation—A literature overview and analysis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolobig, A.; De Marchi, B.; Borga, M. The missing link between flood risk awareness and preparedness: Findings from case studies in an Alpine Region. Nat. Hazards 2012, 63, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antronico, L.; Coscarelli, R.; De Pascale, F.; Condino, F. Social Perception of Geo-Hydrological Risk in the Context of Urban Disaster Risk Reduction: A Comparison between Experts and Population in an Area of Southern Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, J.; Rodriguez-Llanes, J.M.; Robertson, A.; Archer, F. Current and Emerging Disaster Risks Perceptions in Oceania: Key Stakeholders Recommendations for Disaster Management and Resilience Building. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S. A case study of the educational significance of an Arctic exploration experience based on the views of participating youths and their parents/guardians one year later. Jpn. J. Phys. Educ. Hlth. Sport. Sci. 2020, 65, 893–914. [Google Scholar]

- Nazli, N.N.N.N.; Sipon, S.; Zumrah, A.R.; Abdullah, S. The factors that influence the transfer of training in disaster preparedness training: A review. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 192, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, H.; Tsujioka, A.; Kishie, T.; Takenouchi, K.; Udagawa, S.; Kawaguchi, J. Analysis of Institutional Issues of the System of Liaison Officers Dispatched by Prefectures to Local Governments in Times of Disaster. J. Soc. Saf. Sci. 2022, 41, 303–313. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, H.; Tsujioka, A.; Takenouchi, K.; Kawaguchi, J. A study on Disaster Response to Tsunami Warnings Announced Outside of Office Hours by a Gathering System Dependent on the Residential Areas of Local Government Officials: Through the Case Study of Ise City, Mie Prefecture. J. Soc. Saf. Sci. 2023, 43, 1–11. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan (MLIT). The Handbook of the Flood Fighting; MLIT: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. (In Japanese)

- Huang, Q.; Xiao, Y. Geographic Situational Awareness: Mining Tweets for Disaster Preparedness, Emergency Response, Impact, and Recovery. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2015, 4, 1549–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Shah, V.; Vaezi, R.; Bansal, A. Twitter speaks: A case of national disaster situational awareness. J. Inf. Sci. 2020, 46, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrodieva, A.V.; Rachman, O.K.; Harahap, V.B.; Shaw, R. Role of Social Media as a Soft Power Tool in Raising Public Awareness and Engagement in Addressing Climate Change. Climate 2019, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, F.S.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Howes, M.; Torabi, E. Can public awareness, knowledge and engagement improve climate change adaptation policies? Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, L.; Sapountzaki, K.; Scolobig, A.; Perko, T.; Górski, S.; Kaźmierczak, D.; Anson, S.; Carnelli, F.; Bossu, R.; Oliveira, C.S. Citizen participation and public awareness. In Science for Disaster Risk Management: Acting Today, Protecting Tomorrow; Casajus Valles, A., Marin Ferrer, M., Poljanšek, K., Clark, I., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; pp. 544–555. [Google Scholar]

- MacAskill, K. Public interest and participation in planning and infrastructure decisions for disaster risk management. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 39, 101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Location of the Kumozu River and the exercise site.

Figure 1.

Location of the Kumozu River and the exercise site.

Figure 2.

(a) Location and size of the exercise; (b) layout of the exercise site.

Figure 2.

(a) Location and size of the exercise; (b) layout of the exercise site.

Figure 3.

(a) Raising the levee by placing sandbags; (b) raising the levee by placing sandbags and plastic sheets; (c) raising the levee using a water-filled tube; (d) erosion protection on the water side of the levee using plastic sheeting; (e) impoundment of seepage water by placing sandbags (crescent shape); (f) impoundment of seepage water by placing sandbags (in a circular shape).

Figure 3.

(a) Raising the levee by placing sandbags; (b) raising the levee by placing sandbags and plastic sheets; (c) raising the levee using a water-filled tube; (d) erosion protection on the water side of the levee using plastic sheeting; (e) impoundment of seepage water by placing sandbags (crescent shape); (f) impoundment of seepage water by placing sandbags (in a circular shape).

Figure 4.

(a) Setting up communication between organizations; (b) finding and reporting of bank erosion; (c) disaster debris removal and road clearance; (d) drainage of flood water using car-mounted mobile pumps; (e) civil work for the temporary closure of a levee breach; (f) emergency medical assistance. The participants’ uniforms display the name of their organization in Japanese.

Figure 4.

(a) Setting up communication between organizations; (b) finding and reporting of bank erosion; (c) disaster debris removal and road clearance; (d) drainage of flood water using car-mounted mobile pumps; (e) civil work for the temporary closure of a levee breach; (f) emergency medical assistance. The participants’ uniforms display the name of their organization in Japanese.

Figure 5.

The link between the concern of “Poor collaboration with other organization in the large-scale disaster” and the potential solutions.

Figure 5.

The link between the concern of “Poor collaboration with other organization in the large-scale disaster” and the potential solutions.

Figure 6.

The link between the concern regarding a “Lack of real-world flood fighting experience, including safety considerations, for large-scale flooding” and the potential solutions.

Figure 6.

The link between the concern regarding a “Lack of real-world flood fighting experience, including safety considerations, for large-scale flooding” and the potential solutions.

Figure 7.

Analysis of the effectiveness of the exercise to address the issue of “Difficulty in recruiting members” and the residents’ awareness of flood fighting.

Figure 7.

Analysis of the effectiveness of the exercise to address the issue of “Difficulty in recruiting members” and the residents’ awareness of flood fighting.

Table 1.

The major organizations participating in the exercise and their roles.

Table 1.

The major organizations participating in the exercise and their roles.

| No. | Organization | Roles |

|---|

| 1 | Flood-Fighting Corps | Tsu City | Building flood-fighting structures |

| 2 | Yokkaichi City |

| 3 | Ise City |

| 4 | Matsusaka City |

| 5 | Suzuka City |

| 6 | Kameyama City |

| 7 | Taki Town |

| 8 | Meiwa Town |

| 9 | Odai Town |

| 10 | Tamaki Town |

| 11 | Watarai Town |

| 12 | Taiki Town |

| 13 | 33rd Infantry Regiment, Japan Ground Self-Defense Force | Emergency supply transport |

| 14 | Mie Prefectural Police Headquarters | Disaster debris removal and road clearance/Emergency supply transport |

| 15 | Japanese Red Cross Society | Emergency medical assistance |

| 16 | Mie Prefecture Constructors Association | Disaster debris removal and road clearance |

| 17 | Chubu Electric Power Grid Co, Inc. | Disaster debris removal and road clearance |

| 18 | AEON RETAIL Co., Ltd. | Contributing emergency supplies and parking spaces for emergency vehicles |

Table 2.

The principal programs and a timetable of the exercise.

Table 2.

The principal programs and a timetable of the exercise.

| Time | Demonstrated Events | Responsible

Organizations |

|---|

| 9:00 | Opening ceremony | - |

| 9:24 | Press conference on the warning of the approach of a large typhoon (pre-recorded video) | Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and MLIT |

| 9:26 | Set up of communication between municipalities using an online video system | MLIT and Municipalities |

| 9:35 | River patrol | MLIT |

| 9:37 | All the flood-fighting corps on standby | 1–12 |

| Kumozu River level reaches “recommended evacuation level” |

| 9:43 | Detection of inland flooding using distributed sensors | Tsu City |

| 9:45 | Finding and reporting of levee erosion with river patrol | MLIT |

| 9:46 | Start of flood fighting via erosion protection | 12 |

| 9:48 | Issuance of a special storm and tide warning | JMA |

| Kumozu River level reaches “flood danger level” |

| 9:49 | Emergency communication between MLIT and mayors regarding issuing evacuation orders to residents | MLIT and Mayors |

| 9:51 | Sending of emergency alert e-mails to residents at flood risk | MLIT |

| 9:54 | Issuance of evacuation orders | Mayors |

| 9:56 | Start of flood fighting regarding impoundment of seepage water from levee bottoms | 4, 5, 7 |

| 9:58 | Start of flood fighting regarding raising of the levee | 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11 |

| 10:01 | Issuance of a special heavy rain warning | JMA |

| 10:04 | Observation from air using helicopter and camera drone | MLIT |

| 10:10 | Contribution of emergency supplies and parking space for emergency vehicle by private company (pre-recorded video) | 18 |

| 10:13 | Inspection of the flood-fighting structures by invited guests | MLIT, and invited guests |

| 10:14 | Disaster debris removal and road clearance | MLIT, 16, 17 |

| 10:17 | Drainage of floodwater using car-mounted mobile pumps | MLIT, Mie Prefecture |

| 10:19 | Completion of report on flood fighting via erosion protection | 12 |

| 10:20 | Civil work to assist in the temporary closure of levee breach | MLIT, 16 |

| 10:23 | Emergency medical assistance, including triage, ambulance transport, and life-saving measures | 15 |

| 10:29 | Completion of report on flood fighting via impoundment of seepage water from levee bottom | 4, 5, 7 |

| 10:30 | Completion of report on flood fighting regarding raising of the levee | 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11 |

| 10:38 | Emergency supply transport | 13, 14 |

| 10:41 | Report that all the participants have successfully completed their demonstration | All |

| 10:50 | Closing ceremony | - |

Table 3.

Interview result 1: technical and administrative concerns regarding flood fighting.

Table 3.

Interview result 1: technical and administrative concerns regarding flood fighting.

Category

(Total Number) | Key Phrases | Number of

Key Phrases |

|---|

| Poor collaboration with other organizations in a large-scale disaster (10) | There is no regular work/training with other organizations. | 4 |

| There is no communication with people we do not normally conduct business with. | 3 |

| I do not know what my role is in the emergency work that many organizations are working together on. | 2 |

| During a previous disaster response, communication between many organizations was chaotic. | 1 |

| Lack of real-world flood-fighting experience (9) | We only conduct training, with no real-world disaster experience. | 5 |

| We only have a few flood-fighting skills and no comprehensive techniques for responding to large-scale disasters. | 2 |

| There is a lack of expertise in performing disaster response logistics quickly. | 1 |

| It is difficult to switch the mindset of the team that is regularly engaged in non-disaster work. | 1 |

| Concerns about the safety of the team in fighting a large-scale flood disaster (8) | It is difficult to decide when to continue flood fighting and when to evacuate the team from the flood. | 4 |

| The team cannot be dispatched when the flood has already become too large for flood fighting to handle. | 2 |

| There is a lack of skills and experience in flood fighting while protecting ourselves from flood disasters. | 1 |

| The safety of the team will be at risk due to the difficulty of obtaining information about the condition of the disaster site. | 1 |

| Difficulty in recruiting members (5) | The current flood-fighting members are aging, and recruiting young members is very difficult. | 5 |

| No concern if there is a minor flood in the local area (5) | In past disasters, the teams have made the right decisions and report properly because there are only small rivers here. | 3 |

| The teams are well trained and organized to carry out flood-fighting work in the case of minor flood disasters in the area of responsibility. | 1 |

| There is no concern that the flood fighting will be performed in our area, as the teams are very involved in their community. | 1 |

| No concerns about coordinating with others (1) | We are accustomed to working in coordination with other organizations on a regular basis. Therefore, we have no concerns about similar coordination in a disaster response. | 1 |

Table 4.

Interview result 2: the benefits gained with the exercise.

Table 4.

Interview result 2: the benefits gained with the exercise.

Category

(Total Number) | Key Phrases | Number of

Key Phrases |

|---|

| Saw and learned actions, equipment, and materials used by other organizations (11) | We found that other teams’ flood-fighting structures differed from our own and learned from their ingenuity. | 2 |

| When we saw that other teams’ actions and equipment were better than ours, we realized that we needed to update them. | 2 |

| I felt confident when I saw that our demonstration was better than those of other organizations. | 2 |

| It was informative because we rarely get the opportunity to see how other organizations respond to flood disasters. | 2 |

| Seeing the roles and capabilities of other organizations in disaster response helps us coordinate. | 2 |

| We exchanged ideas with participants from other organizations. | 1 |

| Attained a real sense of the situations many organizations face when responding to floods (11) | We found that it is necessary for so many organizations to cooperate to respond to a flood in a large river, and it has raised our morale. | 3 |

| We experienced the entire process in a realistic way, from receiving the deployment order to building the sandbag structures and the completion report. | 3 |

| Thanks to the temporary levee and roads set up in the exercise area, we were able to demonstrate in a realistic atmosphere. | 2 |

| Exercising with heavy equipment gave us a real sense of the hardship of the disaster response. | 1 |

| Failure to properly assign roles in building the sandbag structure causes delays in the exercise, which is the next issue for improving our flood fighting. | 1 |

| Demonstrating by matching the pace of the surrounding teams was a different and valuable experience from normal training. | 1 |

| Built personal relationships with other organizations (7) | We were able to communicate and coordinate face-to-face with other organizations and build personal relationships at the management level during the preparation process. | 6 |

| We unified a detailed method of sandbag replacement by consulting with other flood-fighting teams. | 1 |

| Clarified issues on flood fighting and address them during the preparation (6) | Coordination meetings were frequent, concerns were well-discussed there, and preparations were effective, with roles assigned within the teams. | 2 |

| The teams conducted training in advance to ensure the success of the demonstration during the exercise. | 2 |

| We were able to adjust the location of the work and the shape of the concrete blocks to best suit the exercise through discussion at the coordination meetings. | 1 |

| We were going to demonstrate a flood fighting structure that we had never experienced before, so we trained in advance to acquire skills. | 1 |

Table 5.

Interview result 3: issues with the exercise.

Table 5.

Interview result 3: issues with the exercise.

Category

(Total Number) | Key Phrases | Number of

Key Phrases |

|---|

| No opportunity to actually collaborate with other organizations in the exercise (8) | All of the flood response processes were demonstrated, but each element was separate, and there was no collaboration between them. | 2 |

| It was a missed opportunity that we did not really get to work with the various organizations that participated in the exercise. | 2 |

| I felt that our demonstration was insufficient. I wanted to show more of what we could complete in practice. | 2 |

| It looked like the organizations were demonstrated separately. I could not find out what each team’s role was in the flood response. | 1 |

| We regret that we were too focused on our own demonstration and were unable to perform a larger training exercise by working with others. | 1 |

| Not enough time to deeply study other organizations’ demonstrations (8) | I was able to see the flood-fighting structures next to us, but I did not have time to see other demonstrations, such as drainage pumps. | 2 |

| We were so busy completing our own demonstration that we did not have time to see and learn other demonstrations. | 2 |

| Other demonstrations were shown on the screen for busy participants, but I still wanted to be close and have a direct look. | 2 |

| We understand that the total exercise time is limited, but it would be helpful to have more time to review the other demonstrations. | 1 |

| It was a wasted opportunity that we could not review other demonstrations despite the large number of organizations that participated. | 1 |

| Absence of realistic condition settings as a prerequisite for the exercise (7) | No location and amount of water leakage was indicated, and we simply placed the sandbags with the specified shape and point. | 3 |

| Only the logistical aspects, such as where to put what, were prepared, and the operations that would actually be carried out at the disaster site were not properly simulated. | 2 |

| We needed pictures that would clearly show the connection between the flood situation and our demonstration. | 1 |

| The target completion time for the sandbag structure was not given. All the teams with different participants built the same structure size at different times, which I felt lacked unity and realism. | 1 |

| There were some operational errors in the exercise (5) | There was a discrepancy between the plan and the actual operation on the day, which confused us in demonstrating. | 2 |

| Since the rehearsal and the exercise were held on Saturday and Sunday, it was a burden for participants to take up their weekends. | 1 |

| There was a miscommunication regarding the number of participants from our flood-fighting corps in the exercise. | 1 |

| The area for placing sandbags was too small for the number of participants, and the work and the inspection tour were disrupted. | 1 |

| No demonstration involving local residents (4) | Local community training should be part of the exercise. | 1 |

| Getting residents to participate in the exercise raises their awareness of flood preparedness, which also helps us fight floods. | 1 |

| As inland flooding due to climate change is increasing, it is necessary for residents to have disaster prevention awareness. | 2 |

Table 6.

Interview results 4: the impacts of being observed during the exercise.

Table 6.

Interview results 4: the impacts of being observed during the exercise.

Category

(Total Number) | Key Phrases | Number of

Key Phrases |

|---|

| Good opportunity to publicize flood response operations to local residents (15) | It is good to show our demonstration to the members of city council. | 1 |

| The large-scale exercise had a big impact on the local residents, and it must have left a lasting impression on them. | 2 |

| By making flood fighting more accessible to local residents, it will help recruit our new members. | 4 |

| It was a valuable opportunity because it was difficult to let people know that behind the scenes of our core business we also contribute to the disaster response. | 2 |

| Flood fighting is not very photogenic, so it is good that the government organized such large-scale exercises to attract public attention. | 2 |

| We do not do any PR for our own training, so this exercise was a useful reference for our future training. | 1 |

| The YouTube broadcast provided an opportunity for residents from a wide area to watch the exercise. | 3 |

| The participants showed enthusiasm due to the presence and observation of a large audience (9) | Being visible on the screen made participants more aware of being watched by others, so they were more enthusiastic than they would have been in normal training. | 6 |

| Having local residents and invited guests watch our demonstration boosted the morale of all team members. | 3 |

| Recognizing the importance of investing in public relations (5) | Although it costs money to prepare large screens and stream videos on YouTube, I was grateful that the government prepared such large-scale publicity. | 2 |

| The government cultivated publicity on a scale that would have been impossible for us to achieve on our own, and it was very beneficial. | 2 |

| Public relations is more effective the larger it is, so I am glad the government invested in it. | 1 |

| Few local residents came to see the exercise in person (3) | We should have invited more local residents to the exercise in person, as the experience was very different from watching it on YouTube. | 2 |

| We should have attracted more families by providing transportation, food, and prizes. | 1 |

Table 7.

The number of respondents regarding benefits and dissatisfaction under Concern 1.

Table 7.

The number of respondents regarding benefits and dissatisfaction under Concern 1.

| | Potential Solution 1 | Potential Solution 2 |

|---|

| Benefit only | 2 | 7 |

| Both Benefit and Dissatisfaction | 5 | 4 |

| Dissatisfaction only | 3 | 4 |

Table 8.

The number of respondents indicating benefits and dissatisfactions regarding Concern 2.

Table 8.

The number of respondents indicating benefits and dissatisfactions regarding Concern 2.

| | Potential Solution 3 | Potential Solution 4 |

|---|

| Benefit only | 5 | 9 |

| Both Benefit and Dissatisfaction | 1 | 3 |

| Dissatisfaction only | 6 | 4 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).