Abstract

Economic values have dominated water policy discourse over the last four decades. Very little has been written on social, cultural, and ecological values and their roles in enhancing water security. The primary objective of this paper is to provide a comprehensive analysis of diverse water values with a case study of the National Capital Territory of Delhi, India. To achieve this, a review of the existing scholarship on water values was conducted to develop a set of water values. Field surveys and interviews were conducted to comprehend the water values held by various stakeholders in Delhi. This paper is an attempt to show that viewing water security through the lens of diverse water values (social, cultural, economic and ecological) provides a better understanding of water policies, and enhanced comprehension could potentially result in better policies to promote water security. In the case of Delhi, we additionally found that the claimed predominance of water values such as efficiency, equity, equality, religiosity, and purity does not mean that these values are also actualized in water practices. Another major finding is that all four sets of values are integrated with one another, and policies underpinned by the identified values would be relatively better than policies solely based on economic values.

1. Introduction

Decision-making processes are underpinned by values and so are inseparable. These values take center stage in achieving societal goals [1], and a set of values may result in a set of impacts. For example, the values of efficiency and commoditization lead to the potential to make water a commodity which can be bought and sold freely in the marketplace, restricting access to potable water to only those who can pay [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The current scholarship is full of political economy and political ecology perspectives on water [8,9,10,11,12]. The socialization of water provisioning is inclusive, which makes access to water affordable and universal [13,14]. Therefore, decisions on water management do not solely depend on science, technology, law, or finance, but also hinge on the embodied values held by the stakeholders involved in these decision processes. Such values are reflected in water discourse and are responsible for ensuring the water security of a city or community. The existing literature on water values shows that urban water management primarily focuses on technical dimensions and economic gains. Socio-cultural and ecological values are largely sidelined [15]. For example, using potable water and groundwater for the maintenance of cricket grounds exhibits economic values, as these grounds can be easily maintained by adequately treated wastewater [16]. Sole focus on economic values ignores the values of equity, equality, and precarity. Consequently, inhabitants are deprived of potable water supply because they are not as cash rich and politically powerful as sports authorities. Groenfeldt [17] also argues that every decision about water reflects certain values or a set of values held by decision makers, highlighting the relative worth of different water uses and their prospective impacts and outcomes.

The idea of incorporating values into decision making is not new to water management discourse. Bauer and Smith [18] showed that a comprehensive understanding of water values by the decision makers can improve water planning and management for any settlement. Groenfeldt [17] and Haileslassie et al. [19] (p. 2) also underlined that, after recognizing a set of values, including socio-cultural, economic, and ecological, a comprehensive discussion can lead to informed decision making in urban water management.

Valuing water for different land uses promotes certain value-laden decision-making discourse in the public sphere [17,20,21]. Valuing water means recognizing the multiple uses (values) of water by different users, broadly identified as social, cultural, economic, and ecological. It is necessary to understand the worth of water for an individual or a community [17], [19] (p. 7). Value-laden decision making is essential for stakeholders to make informed decisions [17,20,22,23].

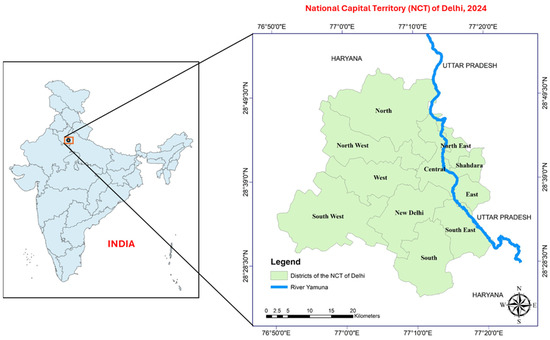

This paper uses a case study of the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, with a geographical area of 1483 sq km and population of nearly 20 million in 2021 (since Census of India 2021 has not been carried out yet, population numbers are estimates made by different authorities) (see Figure 1). Potable water is provided by the Delhi Jal Board (DJB), and the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) is responsible for carrying out planned development of the NCT in accordance with the Master Plan for Delhi. Water policies are prepared by the central government, DJB, and DDA.

Figure 1.

Map showing the study area (NCT of Delhi).

According to the Draft Master Plan for Delhi, 2041 [24], Delhi is a water-scarce city and its available water resources are highly inadequate for the supply of water to city residents. Over 90 percent of raw water procured by DJB comes from neighboring states. The balance of raw water is mainly obtained from groundwater sources in Delhi [25] (p. 240). Due to an increasing population, multiple uses of water, and the illegal extraction of ground water by middle- and higher-income groups, the city faces declining groundwater levels reaching a critical stage. Other prominent challenges include inadequate water supply to residents and high water pollution in the River Yamuna, making water insecurity eminent in the city. In Delhi, water values are reflected in the National Water Policy, 2012, Inter-States Water Sharing Agreement, 1994, Delhi Jal Board Act, 1998, Draft Water Policy for Delhi, 2016, and Draft Master Plan for Delhi, 2041.

However, water values are seldom discussed in academic publications on Delhi, which predominantly promote technical and engineering solutions to water security. Similarly, development plans and water policies do not entertain explicit discussions on water values. The field of water values thus remains largely unexplored. This paper, therefore, attempts to fill this gap by focusing on water values in their variegated forms.

This paper is based on a critical review of the literature and primary data collected through field observations, household surveys, and stakeholder interviews, including of residents, Former Commissioner, DDA, Former Chief Town Planner, Town and Country Planning Organization (TCPO), Executive Engineer, and DJB from 2021–2023. The secondary data sources include the Inter-States Water Sharing Agreement, 1994, Delhi Jal Board Act, 1998, Draft Water Policy for Delhi, 2016, Draft Master Plan for Delhi, 2041, and many more. These sources were examined to identify the underlying water values driving the water management policies and plans in Delhi.

This paper is divided into six sections. The Section 2 comprehensively explores the different water values in the literature. The Section 3 discusses the dominance of economic values over other values during decision making in water management, globally and in Delhi. The Section 4 examines the place of social, cultural, economic, and ecological values in water security in Delhi through the lens of the identified values. The Section 5 contains a discussion on the water values in Delhi. The paper ends with concluding remarks.

2. Diversity of Water Values: A Critical Exposition

We first need to understand what is meant by ‘value’. The term value is defined as relative worth, utility, or importance according to Merriam Webster (2023). Schwartz [26] defined values as a guide for social actors like policymakers and other individuals for selecting their own actions and evaluating others’ actions and events [1,27,28]. Furthermore, values are the belief systems of people or society to decide on societal priorities for various situations. For example, harmony (protect the environment, unity with nature), egalitarianism (equality, social justice, responsibility, etc.), intellectual autonomy (broadmindedness, creativity), affective autonomy (feelings and emotions), mastery (ambition, success, competence), hierarchy (social power, authority, wealth), and conservatism (respect for tradition, social order, social security, etc.) [26]. Thus, values are trans-situational [27].

Correspondingly, Rokeach [1] and Mintz [29] referred to values as standards or criteria which guide behavior, choices, judgments, and actions. Mintz [29] also explained that values specify a relationship between a person and a goal. This means that a value is the comparative worth an individual places on something, which might be developed in response to past experiences and beliefs about right or wrong. Mintz [29] also explained two types of values: intrinsic values and extrinsic values. For example, intrinsic values are honesty, kindness, and others, whereas extrinsic values are to achieve wealth, fame, and others. Thus, values are embodied foundational beliefs meant for steering actions and impacting motivations.

In our view, values are guiding cognitive principles and are influential in making choices from a given set of alternatives to achieve goals. For example, some fundamental values include honesty, trust, respect for others, responsibility, cooperation, perseverance, integrity, and many more. Such values are held by individuals, communities, and institutions. Therefore, decisions on water use and abuse would depend on our predominate values in each context.

Speaking about water values, Bauer and Smith [18] explained two types of water values: one, the tangible value of water (conventional), and two, the intangible value of water (non-conventional). The tangible value of water is measurable, and water is considered as a commodity [18]. Its intangible value is a non-conventional water value held by any individual or society based on spiritual, religious, and cultural beliefs [30]. Such non-conventional values are difficult to measure on a monetary scale [19] (p. 2), [18], [31] (p. 15). Further, Groenfeldt [17] discussed the social, cultural, environmental and economic dimensions of water values and considered them to be important to understanding water security. A summary of social, cultural, ecological, and economic values is provided below.

2.1. Social Values of Water

In 2010, the United Nations General Assembly approved the Right to Safe and Clean Drinking Water and Sanitation as a basic human right. The recognition of water as a human right can be considered as a social water value, since it applies to every human equally and is aimed at improving the general health and well-being of humanity and ecology. The social values of water imply those water values which underpin social needs (well-being) and are often held by communities. The water values that can be highlighted are accommodation (to fulfill needs), human dignity, equality, equity, respect for diversity, inclusivity, and human rights.

2.2. Cultural Values of Water

The cultural values and spiritual values of water are determined by the culture of a society [26], [32] (p. 244). Some religions like Hinduism consider a river as a living being and holy place [33]. Hindus consider water as a symbol of purity and its association is mentioned in holy books and historical texts. Water and its sources in Hinduism are ‘sacred’ and are believed to have cleansing and therapeutic powers. As mentioned in UNESCO [34], in Islam, water symbolizes wisdom, as mentioned in the holy book, the Quran. In Buddhism too, water is considered as a significant element of purity and cleansing of the body, mind, and spirit. Buddhists use water for ceremonial uses and blessings. Buddhism embodies the calmness and serenity of water by practicing water offerings at Buddhist shrines. Water in Christianity is holy and mentioned as a gift from God. A follower professes their faith by bathing in ‘holy water’. Since every religion has similar associations with water, therefore, the first and most important task of water involves washing the whole body. All mosques provide a water source, usually a fountain, for this ablution. From the cultural–spiritual perspective, important water values include religiosity and purity.

2.3. Ecological Values of Water

The ecological dimensions of water values can be assessed by analyzing the condition of water bodies, possibility of water uses from local sources, policy and plans for water bodies, groundwater situations, and the possibility of groundwater recharge options. In past decades, there has been a clear-sighted shift to recognize the ecological value of water. Concerns over environmental degradation due to human use and abuse of water have led stakeholders to realize the rights of nature and respect for nature. “A sustainable water world must reflect social and political dynamics, aspirations, beliefs, values, and their impacts on our own behavior, along with physical, chemical, and biological components of the global water system at a range of spatial and temporal scales” [35] (p. 42).

2.4. Economic Values of Water

Economic water values are based on the allocation of water resources through the marketplace to promote efficiency to achieve the maximum surplus value from the use of water as a resource [36]. For example, the private sector considers water as a commodity, while the public sector recognizes water as a (priced) social good [31] (p. 8). Also, one of the four principles of the Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development, 1992 [37], recommended water be considered as an economic good for social benefits. Therefore, important water values from an economic perspective are efficiency, and effectiveness. Though economic water value is the most studied and researched dimension, it is also, however, imperfectly addressed in decision making and field practices (see Section 3).

In our view, even within these categories, some values are explicit and can be used in explaining water management decisions, while other values are implicit interpretations and influence decisions, but are not acknowledged. So, there is no clear line for separating these sets of values. In view of the discussion above, water values could be considered as highly subjective and multi-dimensional. In other words, water is viewed differently by different people. Furthermore, valuing water is a shared responsibility, as recommended by the High-Level Panel on Water [22]. Whether public sector, private sector, civil society, communities, or individuals, all have the duty towards identifying and considering multiple values of water, as they are inter-connected.

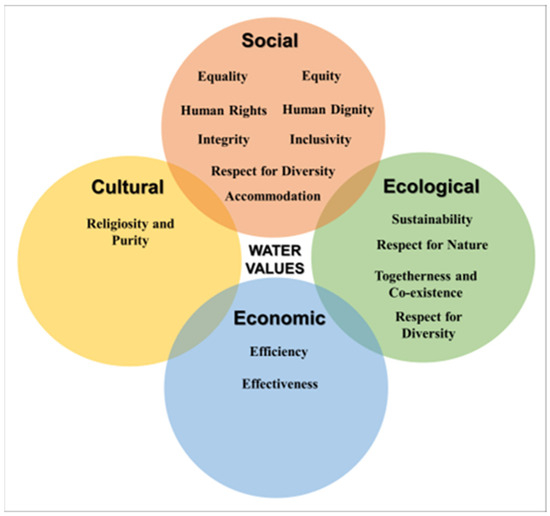

Having mapped the broad area of water values from the literature, a set of values has been identified for the study (see Figure 2), which shows that these values are overlapping, multi-dimensional, coinciding, inter-related, intertwined, complementary, and even conflicting [19] (p. 1), [32] (p. 244). The possibility of the use and integration of these water values for understanding urban water security has been attempted (see Section 4).

Figure 2.

Four sets of water values.

3. Dominance of the Economic Values Globally

Water propels all forms of economic activity, ranging from industry to irrigation and from agriculture to human settlement building and sustainability, tourism, and energy production, including hydropower, among others. The consideration of the economic value of water started in the sixteenth century with the era of the Industrial Revolution. Every commodity was quantified and measured to manage and control it scientifically. Water was reduced to a mere material composition and a resource for other scientific and industrial uses [38,39].

Traditionally, the state has taken an extraordinary interest in water provisioning, assuming that it is serving the public interest. To achieve this, the state has built huge infrastructure [40]. Karen Bakker [8] developed the State Hydraulic Paradigm, in which the State became responsible for the supply of water to people. Here, the state became involved in controlling and managing water resources, treating “water as a public good”, upholding the values of equity and equality.

But the rise of neo-liberalism brought about the concept of minimal state intervention for resource management to make the system economically efficient. It started in the 1980s in most OECD countries. The primary proposition was that the market presents the best way to manage resources for achieving economic efficiency and competence [8]. This marked the beginning of private players in the water and sanitation sector, previously left to local government for public welfare. Water managers assumed that it was only through private sector involvement that we could improve efficiency, enhance technical expertise, and bring a greater flow of financial investments for efficient urban water management [32] (p. 238), [41]. The only value that mattered was economic efficiency, efficiency for creating more and more surplus value. Relentless profitability became the desired end goal through water commoditization.

Liberalization of the water sector was actively encouraged in the Global South through the introduction of pro-private sector policies, liberal lending arrangements between agencies, technical assistance, and credit provisioning by multi-lateral development banks. It was argued that low-income people do not receive access to safe and clean drinking water because of inefficiencies of the bureaucratic state. Since state-run water utilities lack the competency (technical and managerial inefficiencies) to supply water, these should be replaced with private companies [4]. If private companies could manage drinking water, lower-income people would be served better.

Affordability-based arguments were turned on their head. Indeed, unserved low-income people were portrayed as potential beneficiaries to hide huge profits made by private companies. Hence, the social values of water were drowned in the cacophony of the neo-liberal discourse pedaled by state and private players for four decades, beginning in the 1980s. For example, in 1992, the Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development [37] stated four guiding principles, one of which was ‘water has an economic value in all its competing uses and should be recognized as an economic good’. To be fair, the Dublin statement also gave priority to access to clean water and sanitation at affordable prices as a basic human right. However, the primary focus was placed on promoting the economic sustainability of water.

Some scholars have argued that emphasis on economic values is fine if the operationalization of economic values leads to just outcomes such as “environmental improvement; distributive justice and equality; maintenance of plural value-articulating institutions; and, confronting commodification under neo-liberalism” [42], [43] (pp. 155–157). However, such outcomes have not been achieved due to a greater value being attached to economic surplus value.

In the waning year of the twentieth century and early twenty-first century, the post-neo-liberal period saw resistance to the privatization of water, which is evident from popular protests, dissatisfied investors, and regretful governments, as the private sector was unable to fulfill users’ expectations. Globally, private sector involvement in water declined from the mid-1990s due to many reasons, one of them being the unmasking of the economic risks involved in water management, including high capital costs, the constant expansion of networks, the demand for low tariffs, and less revenue generation, among others. Therefore, economic value was not achieved, nor did people receive access to safe water [4,44,45]. Surplus value, however, was surely achieved.

Neo-Liberal Water Values in India and Delhi

In India too, in the wake of liberalization in July 1991, private sector participation in Delhi’s water utility sector was promoted to relieve the government of its presumed ineffectiveness. The Delhi Water Supply and Sanitation Project (DWSSP), 2004, was formulated by the PwC, which acted as a technical consultant to be funded by the World Bank. However, the attempted privatization of clean drinking water could not succeed due to relentless opposition from various water advocates, civil society organizations, NGOs, academic institutions, and individuals, including the current Chief Minister of Delhi, who was an activist at that time [46].

The World Bank also agreed that the presumption of system improvement with the introduction of private players was overoptimistic [4]. Water is even recognized as a human right in India. However, neo-liberal water policies were introduced in the form of public–private partnerships. The private sector handpicked the most profitable urban areas, serving mostly middle-class and wealthier communities, and the majority of the public were left to struggle [41]. For instance, in Delhi, the DJB initiated its first 24 × 7 water supply project in 2013 on a public–private partnership basis in formal colonies like the Malviya Nagar and Vasant Vihar areas, where middle- or high-income populations live. Although the project started on a pilot basis, this highlights the inclination of decision makers to benefit the privileged classes. Economic values appear to take center stage in water governance in India.

As shown above, water has been commoditized globally, as well as in India. Water discourse is dominated by economic values [15]. Water charges are argued to be important for maintaining the water supply system. It is argued that, without financial investments, water systems could not be sustained.

It was not always like this. For example, all guests entering a household in India were welcomed by offering them a glass of water, a sign of welcome and care. Water used to have a social value. Those without money may not have access to clean drinking water. The focus of service providers in the case of water management is to recover infrastructural costs and managerial costs.

The important issue is that, even after infusing the technical–managerial expertise of private players and the consideration of economic values in water management, people are still facing water insecurity all over the world. This raises questions about the values adopted by decision makers in managing water. We assert that viewing water security through the lens of a diversity of water values, including economic values, provides better comprehension of urban water security.

4. Water Values in the NCT of Delhi

The present consensus is that emerging water risks such as scarcity, quality deterioration, and conflicts are the result of a misrecognition of important ecological, social, and cultural values of water, which are derived from the water values of individuals, communities, the state, and other stakeholders [47,48]. Another aspect is that some values have been over-emphasized and others are not given due consideration during decision-making processes [20]. In Delhi, the consequences of such decisions have led to inevitable dependency [18,23], distributive injustices [21,24], water inadequacies [21,24,25,26], and distressed conditions of the River Yamuna [27,28,29,30]. What values have led to this alarming water insecurity situation in Delhi? The identification of these values is the primary task of the remaining part of the paper.

4.1. Sustainability and Precarity

Four points make it clear that the value of sustainability is largely ignored by the DJB. First, the city has continued to be dependent on its neighboring states for water supply over the last three decades. For example, over 90 percent of raw water for Delhi comes from neighboring states [25]. The Draft Water Policy for Delhi, 2016 [49], also identified a high reliance on neighboring states for raw water as one of the major challenges. A high dependence for water on neighboring states is unsustainable both in peace time and during disputes. There have been many instances when the DJB claimed that Delhi was obtaining less raw water from Haryana [50]. During an interview conducted with an Executive Engineer of the DJB in August 2021, he elaborated:

“Recently what happened in 2019, DJB went to the Supreme Court of India regarding the amount of water that is required to serve Delhi. This water is required from Haryana. The SC told them to go to the Tribunal. They didn’t go. Now, when the politics changed, Haryana stopped supplies. So, the level of River Yamuna comes to 69 feet from 674 feet. When the case again reaches SC, they scold Delhi government for why they didn’t go to the Tribunal. Now Haryana has BJP government and Delhi has AAP. Both the parties don’t allow interfering in each other’s matters. People from Delhi were asking for help from officials, but we told them that the case is now in the hands of the Irrigation Minister of Haryana. Only when he allows, they can give water. In October, they shut the canal for the sake of cleaning it. We don’t have our water.”

In times of dispute, raw water supply to Delhi can be easily disrupted. However, there are mechanisms to resolve these disputes through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed in 1994 between five Indian states located in the Upper Yamuna River basin, including Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, and Delhi, for allocating water share amongst the beneficiary states [51] (the stretch of the River Yamuna from its origin in Uttarakhand to Okhla in Delhi is called the ‘Upper Yamuna’). In 1995, the Ministry of Water Resources (presently the Ministry of Jal Shakti) constituted the Upper Yamuna River Board (UYRB) to regulate the allocation of Upper Yamuna water and other functions. The MoU is slated to be reviewed after 2025, if any of the basin states demand. In that case, Delhi is bound to face less acceptable arrangements for procuring raw water (these rivers are Inter-State Rivers and, in India, water is a state subject in the Seventh Schedule as Entry number 17 in the Constitution of India under State List (List II). This means powers related to the planning and management of water are vested in the state governments and the central government becomes involved only in matters of inter-state disputes, as specified in Entry 56 under the Union List (List I)). This also creates water insecurity for the residents of Delhi.

The legalism and formal signing of the MoU may have paved the way for making water available relatively easily to Delhi residents. However, the value of precarity, not sustainability, is the hallmark of these water supply arrangements, because, at any moment, the neighboring state could pull the plug.

4.2. Efficiency and Effectiveness

Second, every summer, Delhi faces water shortages. DJB has planned to increase water production to 998 MGD through mainly groundwater sources to meet a water shortage of approximately 450 MGD [52]. However, dwindling groundwater levels in Delhi due to illegal extraction also makes sustainable water supplies untenable in the future.

According to the Central Groundwater Board (CGWB), Delhi, mainly southern Delhi, is listed in the ‘overexploited’ category, meaning there is more extraction than recharge. According to data released by the Press Information Bureau (PIB) [53], groundwater resources in 2020 highlighted that groundwater extraction was 101.40 percent in the case of Delhi. This has created an imbalance, resulting in a decline in groundwater levels. The Master Plan for Artificial Recharge of Ground Water in India [54] also shows that groundwater levels are declining in 75 percent of the area of Delhi at a daunting speed of 0.20 m per annum. Additionally, the CGWB’s annual report [55] claims that a high salinity and heavy metals such as iron, manganese, and even uranium have been traced above the permissible limits in Delhi’s groundwater. But the high demand–supply gap in the city has forced residents to rely on illegal bore wells and other groundwater sources.

It will be difficult in future to uphold the value of sustainability, since water demand in the city is ever-increasing. The projected water demand was 1380 Million Gallons per Day (MGD) for the year 2021; the DJB was able to generate 921 MGD of water, which was 459 MGD less than the water demand [25]. Delhi’s water demand was based on the water requirement norms of 60 gallons per person per day [24,25].

The Draft Master Plan for Delhi [24] estimated a water demand of 1455 MGD. However, the resource availability for supply of water is unclear. The Draft Master Plan for Delhi [24] reduced freshwater supply norms, ranging from 60 GPCD to 50 GPCD, by justifying its use only for potable purposes. It contains certain mandatory rules for the new development areas for water management (Former Commissioner, DDA, Personal Communication, 9 August 2021).

However, there are no concrete commitments for the existing developed areas suffering from poor water management. As the population increases, the demand supply gap will also rise in future. Precarity stares in the face of Delhi’s residents if 90 percent of water continues to come from neighboring states. Further, ‘over-exploited’ and sub-standard quality of groundwater sources and negligible reuse of wastewater after treatment only exacerbate the challenge of water insecurity.

Third, apart from the challenges of dependency on the neighboring states and receding groundwater levels, surface waterbodies such as lakes and ponds also present another important challenge to the sustainability of water supplies in Delhi. According to the Delhi Parks and Gardens Society (DPGS) [56], a total 969 water bodies such as lakes, ponds, wells, and traditional rainwater storage spaces are under the jurisdiction of agencies such as the DJB, DDA, Forest Department, Municipal Corporation of Delhi, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), and others. But, out of these 969 water bodies, 35.71 percent have dried up, 8.36 percent receive untreated sewage discharge, 10.11 percent are fully encroached, 7.95 percent are covered by legal built-up areas, 4.02 percent are covered by illegal built-up areas, 9.18 percent are legally converted into parks, and the rest, only 24.66 percent of water bodies, remain in their natural state. About 214 waterbodies out of the total 969 are already threatened by rampant construction and large-scale encroachments, where waterbodies are difficult to revive as per land-owning agencies. In fact, land-owning agencies have asked the Wetland Authority of Delhi to eliminate such water bodies from the official records for urban development [57] (The Wetland Authority of Delhi constituted in 2019 with the aim to prepare an action plan for water bodies’ restoration and rejuvenation to protect the wetlands from future encroachments).

The fourth threat to the value of sustainability is the construction of apartments of the Commonwealth Games (CWG) village and the construction of offices of the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC), both located on the River Yamuna floodplains in Zone-O of DDA, which was declared an ecologically sensitive zone in the Master Plan for Delhi, 2021 [58]. A public notice was issued by the DDA to re-zone around 3100 hectares of land to regularize illegal developments in the belt, which was challenged by the Convener of the Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan (YJA), who stated that this development is illegal, as no environmental clearance from government authority was taken before issuing it. Unauthorized constructions on the Yamuna floodplains have led to a decrease in groundwater recharge areas.

Further, it is a mandatory provision to install rainwater-harvesting systems on plots measuring 100 sq m and above in Delhi. First, it helps in groundwater recharge, and second, in the use of stored rainwater for non-potable uses, such as gardening, washing cars, and others. However, the full potential of Rainwater Harvesting (RWH) remains untapped, because these systems are yet to be installed in many buildings (Chief Town Planner, TCPO, Personal Communication, 2 July 2022). According to the DJB, people’s co-operation is crucial to make this initiative successful. Hence, the DJB organizes circle- and division-level workshops and awareness programs on water conservation and RWH (Executive Engineer, DJB, Personal Communication, 31 August 2021). This has been being conducted to make the public understand the ecological values of water.

A high dependency on procuring raw water from neighboring states, declining groundwater levels, dying waterbodies, and the highly polluted River Yamuna show that the values embodied in water security do not promote values such as inter-state water equity, intra-state self-sufficiency, and sustainability, etc. On the contrary, Delhi is fast approaching the value of precarity, presenting deep water insecurity in the future.

Delhi generated gross wastewater equivalent to 4540 Million Liters Per Day (MLD) in 2023, of which only one fourth was treated and the remaining three quarters went to the River Yamuna without any treatment, making it a highly polluted river in India whose water is not fit for consumption ([25], p. 241). “A potential source of water which could reduce dependency on neighbouring states has been made unusable, contributing further to the values of unsustainability and precarity. Further if treated wastewater is used at least for non-potable purposes including gardening, agriculture, etc., this would reduce illegal groundwater extraction and contribute to higher groundwater levels, a step towards achieving self-sufficiency” (Former Commissioner, DDA, Personal Communication, 9 August 2021).

4.3. Exclusion, Inequality, and Inequity

In the case of water distribution to households, section 9 (1a) of the Delhi Jal Board Act, 1998 [59], is exclusionary and discriminatory in nature and does not promote universal access to water. It clearly mentions that the DJB is not liable to supply water to settlements which are constructed in the contravention of any law. This means access to potable water is determined by the nature of settlements; spatially planned settlements receive access to water and informal settlements, as per this law, have no right to obtain access to potable water from a centralized water distribution network. Approximately 76.3 percent of Delhi residents live in informal settlements, as per the Master Plan for Delhi, 2021, which are in contravention of land use violations, land tenure, and building by laws [60]. This distributional inequality and inequity through legal instruments has left these localities water-parched, whereas some formal areas like Delhi Cantonment and the New Delhi Municipal Council continue to receive 24 h access to water within Delhi [61,62].

Historically too, water supply infrastructure in Delhi was deliberately designed to segment rather than universalize supplies. Privileged households had access to piped water in the planned new city and low-income people were left with step wells, hand pumps, and other means. Such decisions already laid the foundation of inequity in water distribution across the city [63].

Even though people living in informal areas are an integral part of Delhi’s economy and society, they remain parched, because the DJB is not legally mandated and not obliged to provide piped water to informal settlements, and people living in such areas heavily rely on temporary and uncertain sources of water such as water tankers, privately purchased water from the water mafia, illegal tube wells, and the illegal tapping of water from centralized pipelines, etc. Such temporary sources of water have given rise to new non-state actors like the ‘water mafia’ in Delhi’s water provisioning [63,64]. The water mafia bring about more inequality in water distribution, because rich and influential people receive easy access to water and the underprivileged are again left on the edges [65,66]. Additionally, water mafia supplying water through tankers illegally exploits groundwater sources.

The value of inequity is also promoted by the DJB by supplying water to informal areas through tankers. A tanker system is a water service for informal settlements, where water is supplied through private-sector- and DJB-owned tankers. It is a low-grade and unfair service, because water could be polluted in the process of transportation from DJB’s water reservoirs to households and community collection points. It is also an unfair service because the entire control remains in the hands of tanker drivers, who generally prefer certain households over others due to rent-seeking tendencies.

Another aspect of unfairness or inequity is that in high- and middle-income areas, such as Vasant Vihar and Janakpuri, respectively, people illegally exploit groundwater sources, even when they have piped water supply from the DJB (Former Commissioner, DDA, Personal Communication, 9 August 2021; Executive Engineer, DJB, Personal Communication, 31 August 2021). Such instances continue, leading to increased pressure on the groundwater in many areas of Delhi [55].

However, in 2014, the Government of the NCT of Delhi took a radical step to minimize water distributional inequalities by providing water through a water subsidy scheme, which allows 20 kiloliters of free water per month to each household who have a functional metered water connection. Under this scheme, if a household crosses the limit of 20 kiloliters per month, every such household must pay for the entire billed consumption. The subsidy is based on the principle of “use more pay more”. According to the Economic Survey of Delhi [25] (p. 239), over 600,000 households have benefitted from the free water scheme. According to our survey conducted in February 2023, we found that this scheme benefits only those households who have a piped water supply and metered connection. It should be noted that all residents in informal areas have no piped water supply or metered connection. Our survey results also showed that the number of residents per household is greater in informal areas than that of formal areas. Therefore, the residents of formal areas and informal areas might not be receiving the same quantity of water per capita under this scheme.

4.4. Inequity and Inequality of Time and Space

The average water consumption in Delhi is estimated to be 240 L per capita per day (LPCD), the highest in the country [67]. The Draft Water Policy for Delhi [49] underlines that 822 MGD was supplied by the DJB city-wide, which is 220 LPCD. But this distribution is inequitable over the city. The spatial distribution of water is highly variable, as the Delhi Cantonment and New Delhi areas receive 509 LPCD and 440 LPCD, respectively, and areas in outer Delhi like Narela and Mehrauli receive as low as 40 LPCD [49], [68] (p. 10). This means that those living in low-income areas are subsidizing New Delhi and Delhi Cantonment by more than 400 LPCD. As a result, the inhabitants of privileged areas tend to waste potable water by using it for washing cars or watering gardens. One consequence of this inequity is that, in outer Delhi, the residents continue to extract low-quality water from unlicensed bore wells and private unregistered tankers, adversely affecting groundwater levels. Second, the quality of water supplied in informal areas through water tankers could also be adversely affected in transit.

Third, most middle-class and low-income households connected with the DJB’s piped network receive water only for 2–4 h during the entire day, with uncomfortable timings from 4 am to 6 am, when most people are asleep. Since women are responsible for fetching and storing water, they are facing the most inconveniences (a survey conducted on 18 July 2022).

Fourth, the DJB claims to provide adequate, good-quality water for drinking. However, residents do not trust the quality of this water. When we asked residents about the quality of the water they received through the DJB network, approximately 50 percent of households responded that the water quality was not good, which compelled them to use water purifiers. The other 50 percent of households were dependent on bottled water procured mostly from private vendors (a survey conducted on 18 July 2022). The DJB’s official website also showed that water samples collected from 1 July 2022 to 15 November 2022 were found to be hazy, turbid, blackish, and mixed with wastewater, and were unfit for human consumption directly. Hence, merely extending the water supply system does not guarantee enhanced access to safe and clean drinking water [69].

Fifth, we observed, in the field, that women and children are mostly responsible for fetching water (see Figure 3), standing in long queues and facing local quarrels at water tanker distribution points. Inefficiency in the water management system in Delhi has forced people to face these challenges in their daily lives.

Figure 3.

Children filling water containers from a public tap installed near to their school.

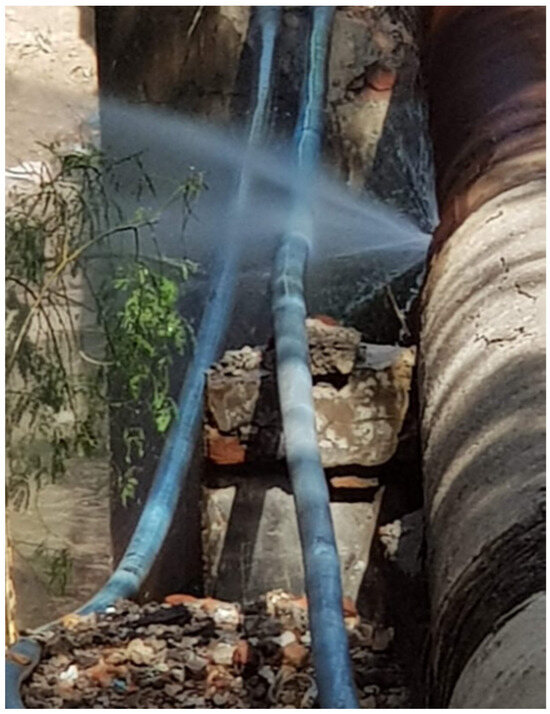

However, according to the DJB, water inadequacy and discontinuity occur due to high non-revenue water (NRW) and unaccounted-for water (UFW), which account for 40 percent of the total treated water supply (Executive Engineer, DJB, Personal Communication, 31 August 2021) (The Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation (CPHEEO) service level benchmarking recommends that NRW must be below 15 percent). The Economic Survey of Delhi [25] further shows that pipe leakages are also responsible for lower water supply (see Figure 4). The DJB claims that residents living in informal areas are responsible for water theft and illegal tapping (Executive Engineer, DJB, Personal Communication, 31 August 2021), and thus, the spatial distribution of potable water in Delhi is highly variable.

Figure 4.

Pipe leakages near a residential area in Delhi.

4.5. Purity and Religiosity: Distressed Conditions of the River Yamuna

Purity is held as an important social value in Indian society. Water is used as a source of purity before any religious and social activities in Indian society. Rivers also play an important role in rituals and religious practices, depending on people’s religious and cultural values [30,70]. Historically, elites with religious inclinations have influenced sanitation policies, believing that even the dumping of treated wastewater in rivers could pollute these water bodies, which are considered to be equivalent to gods. Great civilizations have evolved around rivers; Delhi is one such place along the River Yamuna. The river, which nurtured the city for several centuries and was considered to be a sacred source of water, a symbol of purity and life, today has become a cesspool of sewage, industrial effluents, and a dumping ground for solid wastes. The river receives sewage and solid waste from 1388 non-sewered informal areas such as unauthorized colonies, urban villages, and slums [25] (p. 261). This is the primary reason for pollution in the Yamuna River. The 22 km stretch from Wazirabad to Okhla in Delhi, which is only two percent of the Yamuna River length, contributes nearly 75 percent of its total pollution load [71].

There are over 200 drains carrying significant amounts of untreated sewage and solid waste draining into Yamuna through 22 outfalls in Delhi [71] (p. 28) (see Figure 5). This is due to a lack of adequate infrastructure, as localities of Delhi are unsewered or partially sewered and combined with stormwater drains [72]. It appears that the easiest way to get rid of wastewater is to discharge it to the River Yamuna. In its October 2022 report, the Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC) [72] stated that the total wastewater treatment is 25 percent of the wastewater generated in the city, directly falling into the Yamuna River. Further, untreated industrial effluents and wastewater flowing through the Yamuna with very little freshwater during the dry season disturb the natural ecology of the river.

Figure 5.

Solid wastes dumped near a drain which disrupt flow and pollute River Yamuna.

The River Yamuna is also being polluted due to idol immersions, which is violative of the order of the National Green Tribunal (NGT) [73]. The NGT 2015 order states that polluting the River Yamuna by throwing sacred wastes is a criminal offence and offenders will be punished under the ‘polluter pays’ principle [73] (p. 43).

Water in most cultures is deeply associated with purity and sacredness [2,33]. Hindus consider idol offerings after idol worship as sacred, depending on their religious and cultural values. Hindus also believe that sacred wastes should not be kept along with other municipal wastes, and therefore, should be disposed in rivers or other water bodies, assuming these are not polluted. Further, during most significant festivals like Durga Pooja, Chhat Pooja, and Ganesh Visarjan, ritual activities like idol immersions are performed, which cause serious damage to water bodies. Such activities, although associated with peoples’ beliefs, cause the deterioration of water quality, because people do not follow the guidelines issued by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and DPCC.

A significant step was taken by the CPCB and DPCC to regenerate water bodies and make them sustainable from a water security perspective. The CPCB Guidelines, 2020 [74] (pp. 2–3) and DPCC directions 2021 [75] recommend that idols should be made from natural materials such as clay and water-soluble non-toxic colors. Biodegradable and non-biodegradable materials should be segregated before immersion. However, due to a lack of awareness and lackluster enforcement of guidelines, segregation before immersion does not normally take place even in artificial ponds.(see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Devotees immersing Durga idols in an artificial pond constructed in a ground in Delhi in 2022.

The NGT-appointed Yamuna Pollution Monitoring Committee (YPMC), in 2018, also raised a concern over the pollution of the River Yamuna due to idol immersion and its related rituals. The YPMC asked the concerned authorities to construct artificial ponds for idol immersions (see Figure 6). Further, the GNCTD, in October 2019, took the initiative to construct artificial ponds for idol immersion in Delhi. This initiative appears to be a progressive step towards the preservation and conservation of water bodies in Delhi. After the ban on immersions of idols in the River Yamuna, for the first time, devotees in Delhi immersed clay idols of the Goddess Durga in specially created ponds instead of the river. However, more socially acceptable strategies need to be found, which could be sustained over a long time period.

5. Discussion

This study shows that diverse water values form part of public discourse. Although economic values continue to dominate water policies at the national and state level under the hegemonic neo-liberal global regime, social and cultural values are largely sidelined. Economic values have dominated public narratives and policies. It is, however, disappointing to note that the values of efficiency and effectiveness have not been successfully actualized. A rising percentage of non-revenue water, an increasing demand–supply gap, and small usage of treated wastewater are stellar examples of inefficiency.

This paper identifies a diverse set of values, including social, cultural, ecological, and economic values. The evidence presented in this paper suggests that economic values continue to predominate water policies, schemes, and development plans under the influential economic system of neo-liberalism. We have also shown that socio-cultural values such as purity and religiosity adversely influence the quality of water in the River Yamuna. However, the government is steadfast in reducing impurities and pollution in the River Yamuna.

Ecological values treat water bodies, including the river, as living organisms who have human rights. Policies and plans allude to ecological values, but do not make explicit references. Consequently, we see disappearing water bodies such as lakes and ponds. The River Yamuna is becoming a storehouse for liquid and solid waste. Reduced numbers of water bodies and the highly polluted river show the duplicity of the value of purity. Policymakers and society want to see regenerated water bodies and a clean river, but only a few actions are effectively taken to achieve these goals.

Sustainability is an important part of ecological values. However, it is strange to see in Delhi that the important value of sustainability is not even held in high regard, as most policies and actions go against this value. A high dependency on raw water from neighboring states, negligible use of wastewater, high pollution of the River Yamuna, fast-disappearing waterbodies, and equally speedily reducing groundwater levels are some of the important factors working against the value of sustainability.

However, the values of equality, equity, and religiosity are held in high regard by society and policymakers, but are largely ignored in implementation Delhi. Egalitarian values such as equity and equality have not been entirely ignored in decision-making processes, as we showed in our discussion on the free 20 kiloliters free water scheme. The informal settlements in the city account for nearly 75 percent of the total population, but the Delhi Jal Board (DJB) is not legally bound to provide citizens with piped, treated water [68,69]. The values of exclusion and discrimination have been legally sanctioned by the Delhi Jal Board Act, 1998. Informal settlements are disadvantaged by this Act relative to formal settlements, compelling low-income residents to access low-grade water-provisioning services through tankers.

Under political pressure and court orders, the DJB claims to provide treated, piped water to nearly 93 percent of households in Delhi [25]. Additionally, the DJB also provides tanker services in water-deficient areas as an alternate supply system. This exemplifies two challenges: one, that the DJB practices informality in opposition to statutory claims of pursuing formality; and two, that the DJB buckles under political pressure and provides water to residents living in informally developed areas.

6. Conclusions

This paper identified four sets of values under the broad categories of social, cultural, ecological, and economic values. It appears that these categories of values are enfolded into one another. Non-market values such as socio-cultural values and ecological values are as important as market values. Specifically, values such as equity, equality, purity, religiosity, and sustainability complement the market values of efficiency and effectiveness. For example, fair distribution of water underpinned by the values of equity and equality helps citizens to engage efficiently in productive activities. Likewise, the value of purity, if implemented successfully, has the potential to reduce investments into treating polluted water, thus also complementing the value of sustainability.

Relatively better water policies and plans could be formulated if these are based on a diverse set of values. The analysis in this paper clearly shows that sustainability and precarity have an inverse relationship, while efficiency, sustainability, equality, and equity have a positive co-relation. Decisions made on the basis of a multiplicity of values would be more relatively just than decisions made solely on the basis of economic values.

This is an era of making credible commitments to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). India, along with other nations, has made a commitment to the SDGs. However, the appropriate recognition of social, cultural, and ecological values remains to be made part of the decision-making processes in economically and demographically urban areas. Discussions of such values in the public sphere and their partial achievement are not sufficient for formulating rounded water policies and plans. For example, all four sets of values are being discussed and contested in the public sphere, but they are yet to be made an integral part of water policies and plans. Water policies and plans continue to be dominated by economic values; non-market values are sitting outside and waiting for inclusion in policy arenas.

In the case of water, the value of sustainability should be highly valued, because water is a scarce and irreplaceable resource. The United Nations General Assembly in 2010 approved the Right to Safe and Clean Drinking Water and Sanitation as a basic human right, and multiple similar declarations exist that state the value of water. However, these declarations have created a limited impact on the ground [76,77,78]. In this paper, we show that water insecurity is embedded in water values. To promote water sustainability, the water values of efficiency and equity are equally important, because one is required to promote the other. As we see in the case of Delhi, water is stolen because of low investment in water infrastructure and, at the same time, low-income residents receive less water because a significant part of the potable water does not generate revenue.

Historically, balancing supply and demand has been recognized as a classic solution to solve all water-provisioning problems, where value is calculated by market forces [32]. However, the demand–supply gap has always been increasing in Delhi. The recognition of non-market values must be included in decision-making processes to improve water accessibility, quantity, and quality. It is essential to give each value paramount importance, as they are interrelated and interconnected.

Delhi’s huge demand–supply gap, unequal spatial distribution, and 40 per cent non-revenue water have forced people to rely on illegal bores and tankers, which has led to the over-exploitation of groundwater, highlighting inequality, inefficiency, inequity, and ignorance about human dignity. Religiosity has been an important factor in decision making, but the purity of the river has been compromised. Eventually, not all values are given fair importance, leading to a lack of integrity and peacefulness in water management in Delhi. Even values like efficiency, which is given due importance in water statutes and policies, are not fiercely implemented.

Further, exclusions are promoted through the predominant water values of formality in the case of Delhi. Accordingly, high priority is given to formal settlements built conforming to planning laws and norms. Another commanding water value that affects the health of water bodies, including the River Yamuna and various lakes and ponds, is the value of religiosity. Like efficiency, the values of purity and religiosity are claimed to be prioritized, without implementation on the ground. We did not find any evidence of water policies and provisioning being greatly affected by religion and cultural beliefs. Although engineers dominate the workings of the DJB, efficiency, which is presumed to be the predominant value, is largely ignored in practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and C.B.; methodology, A.K., R.B. and R.M.; formal analysis, A.K., C.B., R.B. and R.M.; investigation, A.K. and R.M.; resources, R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., C.B. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, A.K.; visualization, R.M. and A.K.; supervision, A.K.; project administration, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Water Security and Sustainable Development Hub funded by the UK Research and Innovation’s Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), grant number: ES/S008179/1.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Newcastle University, U.K., for their sustained academic and financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Shiva, V. Water Wars: Privatization, Pollution and Profit; Sound End Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, K.J. An Uncooperative Commodity: Privatizing Water in England and Wales; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, K. Neoliberal versus Postneoliberal Water: Geographies of Privatization and Resistance. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2013, 103, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, M.; Schwartz, K. Water as a political good: Implications for investments. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2006, 6, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, K. The Financialization of Water. Rev. Radic. Political Econ. 2014, 46, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spronk, S.J. The Politics of Water Privatization in the Third World. Rev. Radic. Political Econ. 2007, 39, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, K.J. A Political Ecology of Water Privatization. Stud. Political Econ. 2003, 70, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedow, E. Social Power and the Urbanization of Water: Flows of Power; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kooy, M.; Walter, C.T. Towards A Situated Urban Political Ecology Analysis of Packaged Drinking Water Supply. Water 2019, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.; Yurchenko, Y. The Evolution of Private Provision in Urban Drinking Water: New Geographies, Institutional Ambiguity and the Need for Political Economy. New Political Econ. 2020, 25, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, C.; Schmidt, M. Political ecological perspectives on an indicator-based urban water framework. Water Int. 2023, 48, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, F.; Strang, V. Thinking Relationships Through Water. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R.; Escobar, A.; Bakker, K.; Hommes, L.; Swyngedouw, E.; Hogenboom, B.; Huijbens, E.H.; Jackson, S.; Vos, J.; Harris, L.M.; et al. Riverhood: Political ecologies of socio-nature commoning and translocal struggles for water justice. J. Peasant. Stud. 2023, 50, 1125–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, D.H.; Rojas, R. Cultural Values in Water Management and Governance: Where do we stand? Water 2022, 14, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outlook India, IPL 2021: National Green Tribunal Directs Centre to Regulate Extraction of Groundwater for Cricket Matches. 2021. Available online: https://www.outlookindia.com/sports/sports-news-ipl-2021-national-green-tribunal-directs-centre-to-regulate-extraction-of-groundwater-news-380465 (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Groenfeldt, D. Water Ethics: A Values Approach to Solving the Water Crisis, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, K.R.; Smith, A.Z. Value in water resources management: What is water worth? Water Int. 2007, 32, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haileslassie, A.; Ludi, E.; Roe, M.; Button, C. Water Values: Discourses and Perspective. In Clean Water and Sanitation; Filho, W.L., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Salvia, A.L., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Groenfeldt, D. Incorporating ethics into water decision-making. In Global Water Ethics; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Groenfeldt, D.; Schmidt, J.J. Ethics and Water Governance. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Level Panel on Water. Making Every Drop Count. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development. 2018. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/documents/making-every-drop-count-high-level-panel-water-23223 (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Pigmans, K.; Aldewereld, H.; Dignum, V.; Doorn, N. The Role of Value Deliberation to Improve Stakeholder Participation in Issues of Water Governance. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 4067–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhi Development Authority. Draft Master Plan for Delhi-2041. 2021. Available online: https://dda.gov.in/master-plan-2041-draft (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Delhi Jal Board. Economic Survey of Delhi 2022–2023. 2023. Available online: https://delhiplanning.delhi.gov.in/sites/default/files/Planning/ch._13_water_supply_and_sewerage.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Schwartz, S.H. A Theory of Cultural Values and Some Implications for Work. Appl. Psychol. Int. Review. 1999, 48, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kluckhohn, C. Values and value-orientations in the theory of action: An exploration in definition and classification. In Toward a General Theory of Action; Parsons, T., Shils, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1951; pp. 388–733. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, S. What are Values? Ethics Sage 2018. Available online: https://www.ethicssage.com/2018/08/what-are-values.html (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Ncube, S.; Beevers, L.; Momblanch, A. Towards Intangible Freshwater Cultural Ecosystem Services: Informing Sustainable Water Resources Management. Water 2021, 13, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.J.; Orr, S. The Value of Water: A Framework for Understanding Water Valuation, Risk and Stewardship. Int. Financ. Corp. 2015. Available online: https://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net/downloads/the_value_of_water_discussion_draft_final_august_2015.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Euzen, A.; Morehouse, B. Special issue introduction Water: What Values? Policy Soc. 2011, 30, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baviskar, A. What the Eye Does Not See: The Yamuna in the Imagination of Delhi. Econ. Political Wkly. 2011, 46, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Bangkok and Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific. Water Ethics and Water Resource Management; UNESCO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bogardi, J.J.; Dudgeon, D.; Lawford, R.; Flinkerbusch, E.; Mayn, A.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Vielhauer, K.; Vörösmarty, C. Water security for a planet under pressure: Interconnected challenges of a changing world call for sustainable solutions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; Ortega, J.M.; Glenk, K.; Ioris, A.A. The Value Base of Water Governance: A Multi-Disciplinary Perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development 1992, International Conference on Water and the Environment. 1992. Available online: https://www.gdrc.org/uem/water/dublin-statement.html (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Gibbons, D.C. The Economic Value of Water; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, C.F. Values and Western Water: A History of the Dominant Ideas; Natural Resources Law Center, University of Colorado School of Law: Boulder, CO, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, J. What Is Water? The History of a Modern Abstraction; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Budds, J.; McGranahan, G. Are the debates on water privatization missing the point? Experiences from Africa, Asia and Latin America. Environ. Urban. 2003, 15, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, G.; Baggethun, E.G.; Zografos, C. To value or not to value? That is not the question. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 94, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulis, B.S. The economic valuation of nature: A question of justice? Ecol. Econ. 2014, 104, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.P.; Koppen, B.V.; Houweling, E.V. The Human Right to Water: The Importance of Domestic and Productive Water Rights. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2013, 20, 849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, J.H.; Senent-De Frutos, J.A.; Molina, E.H. Murky waters: The impact of privatizing water use on environmental degradation and the exclusion of local communities in the Caribbean. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2021, 38, 152–172. [Google Scholar]

- Asthana, V. Water Policy Processes in India; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Weshah, R.A.; Saidan, M.N.; Al-Omari, A.S. Environmental Ethics as a Tool for Sustainable Water Resource Management; American Water Works Association: Portland, OR, USA, 2016; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Sara, J.J. Standing for the Value of Water. World Bank Blogs, 7 September 2017; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Delhi Jal Board, Draft Water Policy for Delhi. 2016. Available online: https://delhijalboard.delhi.gov.in/sites/default/files/Jalboard/universal-tab/water_policy_21112016_0.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- The Hindu. Delhi: A City Dependent on Its Neighbours for Water; The Hindu: New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Jal Shakti, Government of India, Memorandum of Understanding 1994. 1995. Available online: https://jalshakti-dowr.gov.in/upper-yamuna-river-board/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Hindustan Times. Summer Action Plan: DJB to Target 998MGD Peak Water Supply; Hindustan Times: New Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Press Information Bureau. Status of Groundwater; Press Information Bureau: New Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Central Ground Water Board. Master Plan for Artificial Recharge to Groundwater in India 2020; Ministry of Jal Shakti, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Central Ground Water Board (CGWB). Ground Water Year Book National Capital Territory, Delhi 2020–2021; Ministry of Jal Shakti, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Delhi Parks and Gardens Society, Department of Environment, Government of NCT of Delhi. 2018. Available online: https://dpgs.delhi.gov.in/sites/default/files/DPGS/generic_multiple_files/water_bodies_presentation.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- The Hindu. Delhi Agencies Seek to Delist 232 out of 1045 Waterbodies; The Hindu: New Delhi, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sharan, A. A river and the riverfront: Delhi’s Yamuna as an in-between space. City Cult. Soc. 2016, 7, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi, The Delhi Jal Board Act 1998. 1998. Available online: https://delhijalboard.delhi.gov.in/sites/default/files/Jalboard/generic_multiple_files/delhi_jal_board_act_1998.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Truelove, Y. Gray Zones: The Everyday Practices and Governance of Water beyond the Network. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 1758–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, Y. Negotiating states of water: Producing illegibility, bureaucratic arbitrariness, and distributive injustices in Delhi. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2018, 36, 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.; Sharma, S. Delhi–Mumbai Industrial Corridor: Economic and Environmental Consequences. Econ. Political Wkly. 2017, 52, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Truelove, Y. Who is the state? Infrastructural power and everyday water governance in Delhi. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2021, 39, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, Y. Incongruent Waterworlds: Situating the Everyday Practices and Power of Water in Delhi. South Asia Multidiscip. Acad. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, M. Mafias’ in the Waterscape: Urban Informality and Everyday Public Authority in Bangalore. Water Altern. 2014, 7, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Birkinshaw, M. Water Mafia’ politics and unruly informality in Delhi’s unauthorised colonies. In Water, Creativity and Meaning: Multidisciplinary Understandings of Human-Water Relationships; Roberts, L., Phillips, K., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, S.C. Water Management for a Megacity: National Capital Territory of Delhi. Water Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, N.; Cooper, S.; Mdee, A.; Singhal, S. Infrastructural Violence: Five Axes of Inequities in Water Supply in Delhi, India. Front. Water 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, S.; Sharma, S.; Banda, S. The Delhi Jal Board: Seeing beyond the Planned Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. 2015. p. Working Paper. Available online: https://cprindia.org/briefsreports/the-delhi-jal-board-djb-seeing-beyond-the-planned/ (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Jain, S.K.; Kumar, P. Environmental flows in India: Towards sustainable water management. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2014, 59, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamuna Monitoring Committee. 29 June 2020. Available online: https://greentribunal.gov.in/sites/default/files/news_updates/Final%20Report%20by%20Yamuna%20Monitoring%20Committee%20in%20OA%20No.%2006%20of%202012.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Delhi Pollution Control Committee. Progress in Rejuvenation of River Yamuna. October 2022. Available online: https://www.dpcc.delhigovt.nic.in//uploads/pdf/Progress-Rejuvenation%20of%20River%20Yamuna-%20Oct%202022.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Delhi Pollution Control Committee. Impact of Idol Immersion on the Water Quality of River Yamuna, Delhi; Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi: New Delhi, India, 2019.

- Central Pollution Control Board. Revised Guidelines for Idol Immersion; Central Pollution Control Board: Delhi, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Delhi Pollution Control Committee. Direction dated 13-10-2021 u/s 33 A of the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 read along with Hon’ble National Green Tribunal orders for the immersion of idols on the festive occasion of Durga Pooja etc., Delhi; Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi: New Delhi, India, 2021. Available online: https://www.dpcc.delhigovt.nic.in//uploads/pdf/Directions13-10-2021pdf-ce01e274fd785e549bf3f72363e0b2ec.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- United Nations-Water. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2021: Valuing Water; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations-Water. World Water Day 2021 Toolkit. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwater.org/news/un-world-water-development-report-2021-%E2%80%98valuing-water%E2%80%99 (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Truelove, Y. (Re-)Conceptualizing water inequality in Delhi, India through a feminist political ecology framework. Geoforum 2011, 42, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).