1. Introduction

The ongoing Nile River dispute, involving Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan, represents a critical juncture in transboundary water conflicts, having evolved over nearly 12 years to a pivotal moment with the completed filling of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) in 2023 [

1]. This event not only marks a significant breaking point surpassing previous negotiation phases but also brings to the forefront the complex interaction between geopolitical interests and regional stability in transboundary water management. The Nile River has played a major role in shaping the cultural and economic development of the eleven African countries it flows through—the Nile River spans Burundi, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda. Such transboundary waters highlight the intricate challenges and tensions that arise over shared natural resources. Navigating water resources presents a unique challenge for nations, as it deviates from the conventional rigid land boundaries often set; water, in its fluidity, serves to both link and divide states and has historically been both a source of conflict and of cooperation [

2]. Particularly in regions where water is scarce, any mismanagement of transboundary waters can rapidly escalate into national conflicts and instability.

Egypt and Sudan’s relations with Ethiopia have worsened due to complications over the use of the Nile River since 2011, when the GERD was announced [

3]. During the Arab Spring uprising, the Addis Ababa government announced its intention to construct the largest hydropower project in Africa, serving as an energy source that utilizes the natural flow of water through a dam to generate electricity [

3]. Through the GERD, Ethiopia aspires to solve its severe energy shortage and boost its economic growth by exporting electricity to the neighboring nations. Up to 6500 megawatts of electricity may be generated through the GERD, doubling the country’s annual electrical output, according to government estimates; this will provide reliable power to the 60% of Ethiopia’s population living without access to electricity [

4]. It is crucial to emphasize, however, that approximately 85% of the water flowing into the Nile River comes from the Ethiopian highlands through the Blue Nile [

5], putting Ethiopia’s national interests in conflict with those of the lower riparian states. Sudan’s stance has been ambivalent, initially showing support for the potential benefits such as electricity imports and flood control but later aligning more closely with Egypt due to geopolitical tensions and disputes over border territories [

3]. It is a matter of fact that with downstream nations’ almost exclusive reliance on the Nile for their water needs, interfering with the river’s water flow could give rise to national security issues.

Economically, the GERD holds potential benefits and risks for the Nile Basin countries. Wheeler et al. [

6], Bass et al. [

7], and Basheer et al. [

8] demonstrate the dam’s capacity to enhance power production and stabilize water levels across the Nile Basin. These improvements offer tangible benefits for Ethiopia and Sudan and can potentially safeguard Egypt against significant adverse effects through the strategic management of water flow and reservoir operations. Conversely, Ahmed [

9] highlights the economic burdens placed on downstream countries, particularly Egypt, where the GERD threatens water and food security, highlighting failed negotiations amid Ethiopia’s strategic delays in reaching a trilateral agreement.

Moreover, the environmental implications of the GERD highlight the complexity of its impact. Batisha [

10] used the Rapid Impact Assessment Matrix (RIAM) to evaluate the GERD’s impact, revealing its complex environmental effects. The assessment showed significant negative impacts on physical, chemical, biological, and ecological aspects for both upstream and downstream areas. However, it also noted positive socio-cultural and economic effects for upstream regions, with negative outcomes for those downstream. Elagib and Basheer [

11] further elaborate on the ecological challenges, noting potential adversities for fish, aquatic plants, and biodiversity resulting from alterations in water temperature, salinity, and oxygen content. Yet, El-Nashar and Elyamany [

12] suggest that through proactive management actions and policies, it may be possible to mitigate the dam’s negative environmental effects on Egypt, pointing towards solutions that conserve water resources while accommodating the dam’s operation.

Despite this extensive body of research highlighting both the advantages and the severe consequences of the GERD, negotiations have lingered without reaching practical solutions. In light of such ongoing disputes, this paper sets out to explore the complex dynamics of the GERD conflict as a prime example of the challenges in water diplomacy—a term which started emerging around the mid-1990s with the realization that transboundary water management is an intrinsically political process [

13]. In this paper, we conducted a comprehensive literature review to analyze the GERD conflict. This involved examining a wide array of resources, including academic articles, historical records, official reports, and media sources. Given the long-standing nature of this conflict, which has deep historical roots and extensive documentation, tracking its progression from inception to the present can be challenging. By synthesizing information from various perspectives, we aim to provide a thorough and balanced overview. Our objective is to amalgamate these diverse sources to put the entire conflict into perspective, highlighting key milestones, stakeholder actions, and potential pathways for resolution. This approach is particularly significant as it addresses the lack of comprehensive synthesis in the existing literature on the emergence and progression of the GERD conflict.

Our paper also advocates for a revised legal framework that moves beyond past agreements towards a more inclusive cooperative management strategy for the Nile’s waters. It proposes the development of a new treaty framework among Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan based on existing agreements and inspired by successful international dispute resolutions. The core argument is that collaboration is the most viable path forward for the GERD-impacted countries, as continued conflict or lack of cooperation could escalate tensions and potentially lead to more severe disputes. Research shows that the combined impact of demographic pressures and climate change is likely to heighten future hydro-political risks in water-stressed regions like that of the Nile basin, highlighting the urgent need for proactive cooperation strategies to mitigate potential conflicts as early as possible [

14]. Towards that end, our paper additionally suggests potential roles for neutral third-party interventions using an improved Graph Model for Conflict Resolution [

15] to facilitate unbiased negotiations, emphasizing their importance in fostering trust and ensuring equitable outcomes. The originality of our research lies in its comprehensive approach to tracing the GERD conflict, integrating historical treaty analysis, contemporary diplomatic challenges, and proposing forward-looking solutions grounded in international legal precedents. By advocating for a collaborative approach and suggesting third-party facilitation, our paper aims to contribute to the development of more adaptable and cooperative water management practices in the region.

2. Theoretical Framework

Water cooperation involves collaborative efforts by states and stakeholders to manage, use, and protect shared water resources sustainably and equitably. It emphasizes mutual benefits, trust building, and the establishment of institutional mechanisms for joint decision making and conflict resolution [

16]. Water diplomacy, on the other hand, goes beyond technical water management to address the political and social dimensions of water resources. It involves negotiation, dialogue, and strategic communication to prevent and resolve disputes over shared water bodies, aiming to promote peace, security, and regional stability [

13,

16]. Effective water cooperation is vital for managing transboundary water resources. It requires collaborative efforts to manage, utilize, and protect shared water resources to ensure sustainability and equitable access for all riparian states.

For instance, the study by Mirumachi and Allan [

17] on the role of power asymmetries in water cooperation highlights the importance of creating equitable and inclusive frameworks to mitigate conflicts and promote cooperation. Similarly, the success of Finland’s cooperative water management practices with Sweden, Norway, and Russia highlights the significance of building trust and establishing legal frameworks to support sustainable water management [

18]. Moreover, the analysis by Zeitoun and Warner [

19] on hydro-hegemony provides insights into the dynamics of power and control in transboundary water interactions, emphasizing the need for balanced power relations to achieve effective cooperation.

Diplomacy, in its broadest sense, encompasses the systematic and strategic management of international relations through negotiation, dialogue, and strategic communication. In the context of water resources, diplomacy functions as a critical mechanism for the prevention and resolution of disputes over shared water bodies. Water diplomacy, a specialized branch of this field, is centered on the negotiation, formulation, and enforcement of agreements governing the management and utilization of transboundary water resources. This approach integrates technical, legal, and political dimensions to address the complex challenges inherent in the management of shared water resources, thereby promoting sustainable and cooperative solutions. Water diplomacy seeks to balance the interests of different riparian states by promoting cooperative mechanisms that ensure equitable and sustainable water distribution [

20]. The process involves the integration of technical, legal, and political dimensions to address the complex challenges associated with transboundary water management. Successful water diplomacy relies on the establishment of trust, transparency, and mutual understanding among the involved parties [

17,

21]. The case of the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna (GBM) River Basin involving China and India illustrates the complexities and challenges of water diplomacy. The asymmetry in power relations, lack of trust, and differing national interests have hindered effective cooperation despite efforts to establish data-sharing agreements and joint mechanisms [

21]. The GBM experience highlights the need for robust institutional frameworks and continuous engagement to overcome mistrust and foster sustainable water management.

Our argument emphasizes that while collaboration is often the preferred path forward due to the increasing scarcity of water and the potential for severe conflicts, it is crucial to understand that cooperation must be framed within conditions that ensure win-win outcomes for all parties involved. Recognizing that there are scenarios where conflict may be preferable for some parties highlights the necessity of a structured approach to diplomacy that includes checks and balances and an objective assessment of each party’s preferences and strategies. This nuanced perspective necessitates a robust, scientific approach to conflict resolution, which we address using the Graph Model for Conflict Resolution (GMCR) and its revenue function [

15]. The GMCR, rooted in classical game theory, provides an objective and quantitative framework for evaluating the preferences and strategies of the involved parties in the GERD conflict. The revenue function, a key component of the GMCR, allows for the precise calculation of benefits and costs associated with each strategy. This objective evaluation is crucial for understanding the dynamic evolution of the conflict and identifying stable, mutually acceptable solutions. By simulating various scenarios and assessing the dynamic interactions between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan, the GMCR demonstrates how collaboration can lead to stable outcomes and equitable resource distribution. This scientific method, along with historical examples of resolved water conflicts, substantiates our argument that collaboration, facilitated through structured and impartial frameworks, is both feasible and beneficial for all parties involved in the GERD conflict.

The theoretical framework highlights the critical importance of collaborative and diplomatic efforts in the management of transboundary water resources. Effective water cooperation necessitates inclusive and equitable institutional mechanisms that prioritize mutual benefits, trust building, and joint decision making to sustainably manage shared resources. The success of Finland’s cooperative water management with its neighboring countries exemplifies the value of trust and robust legal frameworks in achieving sustainable outcomes. Conversely, the challenges faced in the GBM River Basin highlight the complexities inherent in water diplomacy and the necessity of ongoing engagement and strong institutional support to mitigate power asymmetries and build trust. By integrating technical, legal, and political dimensions, water diplomacy plays a pivotal role in fostering regional stability, peace, and security in transboundary water management. This theoretical framework provides a roadmap for addressing the GERD conflict, emphasizing the need for continuous dialogue, transparent data sharing, and the establishment of a joint water management institution to achieve a sustainable resolution.

3. History of Water Treaties in the Nile Basin

By examining the various water-related treaties that have shaped the relationship between upstream and downstream countries in the Nile Basin, this section explores the historical context of the Nile’s shared waters. These treaties can be traced back to colonial times between 1885 and the Second World War when the entire Nile Basin was under the rule of foreign, mainly European, powers [

22]. As such, it became necessary to regulate the water resources attached to each of the present colonial powers.

The United Kingdom, which ruled over Egypt from 1882 until 1922, proactively partook in treaties and legal agreements to regulate the use of the Nile waters. The United Kingdom and Italy signed a protocol on 15 April 1891, delineating their respective areas of influence in Eastern Africa [

22]. Article III of this protocol aimed to protect Egypt’s Nile waters contributed to by the Atbara River—parts of which were acquired by Italy in their acquisition of Eritrea—by preventing irrigation or works on the Atbara that could modify its flow into the Nile. Followingly, the United Kingdom and Ethiopia signed the Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1902 in Addis Ababa. In this agreement, Article III states that Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia “engages himself towards the Government of His Britannic Majesty not to construct, or allow to be constructed, any work across the Blue Nile, Lake Tsana, or the Sobat which would arrest the flow of their waters into the Nile, except in agreement with His Britannic Majesty’s Government and the Government of Sudan” [

23]. The treaty was signed and presented to both Houses of Parliament in the United Kingdom in December 1902, with a letter of ratification submitted to Ethiopia on 28 October 1902. However, as Robertson [

24] highlighted, Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia promised Great Britain in May 1902 not to interfere with the Blue Nile waters and upheld this promise, but he never ratified it in an official agreement, meaning the treaty was never officially ratified. The status of this treaty has become a source of contention, as Egypt and Sudan argue that Ethiopia should adhere to the treaty, while Ethiopia contends that it is not legally bound by an unratified treaty made during colonial times. It is worth highlighting that a common objective one can note in these previously delineated treaties is establishing the principle of non-interference, namely that no upper-basin country should interfere in the Nile River’s flow, especially if to the detriment of Egypt.

Following Egypt’s official independence from Great Britain in 1922, arguably the most important agreement regarding the Nile waters was reached by Great Britain and Egypt in their exchange of notes in 1929, with Britain representing its African colonies at the time. The “1929 Nile Waters Agreement” served to quantify the annual water allocation from the Nile for Egypt and Sudan (at the time, Sudan was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt), with Egypt being allocated 48 billion cubic meters and Sudan 4 billion cubic meters [

25]; more importantly, the agreement stated that

Except with the prior consent of the Egyptian Government, no irrigation works shall be undertaken nor electric generators installed along the Nile and its branches nor on the lakes from which they flow if these lakes are situated in Sudan or in countries under British administration which could jeopardize the interests of Egypt either by reducing the quantity of water flowing into Egypt or appreciably changing the date of its flow or causing its level to drop [

26] (p. 18).

As such, this treaty provided Egypt with the power to control any construction projects along the Nile River or its tributaries so as to limit any interference with the Nile River’s flow. The agreement was grounded in the acknowledgment of Egypt’s “natural and historic rights in the waters of the Nile”, as affirmed by Great Britain in the exchange of notes [

22] (p. 50). This recognition appears to be rooted in the historical reliance of Egyptian civilization, since its inception, on the resources of the Nile River.

In 1956, Sudan gained independence from Britain and Egypt, resulting in a radical transformation of the geopolitical landscape. The newly independent Sudan demanded a renegotiation of the 1929 Nile Waters Agreement [

27]. As such came the following 1959 agreement between Egypt and Sudan. The “Agreement between the United Arab Republic [Egypt] and the Republic of Sudan for the Full Utilization of the Nile Waters” granted these two countries full control over the utilization of the Nile waters. Under this agreement, the total average annual Nile flow was divided between Egypt and Sudan, with allocations of 55.5 and 18.5 billion cubic meters, respectively—any remaining water was assumed to be lost due to evaporation or swamp areas [

26,

27]. Furthermore, through this treaty, Egypt agreed to the construction of the Sudanese Roseires Dam on the Blue Nile, and Sudan agreed to the construction of the Egyptian Aswan High Dam [

28], highlighting the importance of mutual agreements of involved parties in such cases. The agreement highlights this mutual consent in two points:

In order to regulate the River waters and control their flow into the sea, the two Republics agree that the United Arab Republic constructs the Sudd el Aali at Aswan as the first link of a series of projects on the Nile for over-year storage.

In order to enable Sudan to utilize its share of the water, the two Republics agree that the Republic of Sudan shall construct the Roseires Dam on the Blue Nile and any other works which the Republic of the Sudan considers essential for the utilization of its share.

It comes as no surprise, however, that the 1929 and 1959 agreements were causes of much contention in the Nile Basin, as they primarily allocated the Nile’s water resources between Egypt and Sudan, excluding other upstream countries from any significant allocation or management role. However, Egypt’s veto power over the Nile did not particularly mean that no construction projects could take place along the river. For example, the 1952 Owen Falls Agreement allowed the construction of the Owen Falls Dam in Uganda. This agreement was reached through an exchange of notes between Egypt and the United Kingdom, which was then acting on behalf of its colony Uganda. According to the agreement, the Uganda Electricity Board was responsible for constructing and managing the dam. However, to protect Egypt’s interests in the Nile, an Egyptian resident engineer was stationed at the construction site to oversee the project and ensure that sufficient water flowed through the dam to meet Egypt’s needs [

22].

In the immediate aftermath of the 1959 Nile Agreement, Egypt and Sudan began negotiations to manage the river jointly with the upper riparian states [

29]. During this phase, it was evident that more studies were needed in order to improve existing technical information on the hydrology of the Nile River basin [

28]. The United Nations and the World Bank supported these initiatives, ultimately leading to the establishment of projects like the Hydrometeorological Survey of 1967 [

29]. This initiative, aided by the United Nations Development Program, was aimed at gathering and analyzing data to support water resources planning for the participating nations, which included Burundi, Egypt, Kenya, Sudan, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. Interestingly, Ethiopia only joined as an observer in 1971. Although this initiative did not result in a basin-wide agreement among riparian states, it served as a catalyst for building trust and enhancing information exchange among these nations [

30]. A Nile Basin Commission was also attempted by Egypt and Sudan under the umbrella of Hydromet in 1976. However, the other riparian states participating in the Hydromet refused to collaborate on anything beyond the collection and analysis of Nile data. It was not in their interest to engage in allocation negotiations, as such discussions could limit their capacity to withdraw or utilize water from the Nile [

28].

A more recent agreement in global memory is the Cairo Cooperation Framework of July 1993 between Egypt and Ethiopia, where both nations pledged not to implement water projects that would be detrimental to the interests of the other and to consult on initiatives to reduce waste and increase the Nile’s water flow [

31]. Then, in 1999, for the first time in the Nile Basin’s history, a basin-wide institution was established as the Nile Basin Initiative, in recognition of the need for a collaborative framework to address the challenges and opportunities associated with the Nile River.

To date, the primary water policy governing the allocation of water among the nations in the Nile Basin is the bilateral agreement of 1959. When placing the historical treaties of the Nile Basin into the broader context of international law, it becomes evident that these agreements were uniquely tailored to the bilateral interests of Egypt and Sudan under distinct geopolitical circumstances. Notably, the 1929 and 1959 Nile Waters Agreements focused on water allocation and management between these two countries, excluding other Nile Basin nations. This exclusion has in fact introduced significant risks for Egypt and Sudan.

The relevance of the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses [

32] is particularly pronounced in this context. The convention emphasizes equitable and reasonable utilization of transboundary waters, obligating states to ensure that their activities do not cause significant harm to other watercourse states. Historically, the absence of a comprehensive, basin-wide treaty aligned with standards similar to the UN’s has resulted in a lack of formal mechanisms to ensure that the actions of any Nile Basin country do not jeopardize others’ access to the Nile waters.

4. Recent History

The historical allocation of waters in the Nile Basin has often been frowned upon as biased towards lower riparian nations, especially Egypt. This issue is particularly contentious given that many of the Nile Basin countries were under colonial rule during the time of the water treaties discussed previously; thus, after gaining independence, many upper riparian nations no longer viewed these treaties as binding [

22]. However, with Egypt relying on the Nile for over 90% of its water needs, interfering with the river’s flow puts the country at risk of not being able to access a most basic, crucial resource [

33]. As such, when Ethiopia announced in 2011 its plan for constructing Africa’s largest hydroelectric power plant, the GERD, on the Nile, the news was not received with much enthusiasm from its downstream neighbor Egypt. Regardless of the implications for the lower riparian nations, Ethiopia proceeded with its unilateral decision to construct the dam, denying that it would have any negative effects on the downstream Nile River flow.

Disputes continued to arise over the dam’s filling and operation, with Egypt demanding guarantees for its water share and Ethiopia insisting on its right to development. The only other country downstream of the Blue Nile, Sudan, has held a varying stance over time regarding the GERD. Initially opposed to the dam, Sudan then shifted its opinion, recognizing that a well-managed GERD could contribute positively to the country with regulated water flow and increased electricity supply: under Former President Omar al-Bashir’s rule, Sudan embraced Ethiopia’s assurances regarding the dam’s potential to manage flooding and the anticipated benefits from the generated power [

34]. Nevertheless, Sudan remained wary and indicated fears over the dam’s impact on its own hydroelectric installations and national development goals [

35].

In 2012, the formation of the International Panel of Experts (IPoE) marked a critical early step in the dialogue surrounding the GERD [

36]. The IPoE is composed of ten members: two each from Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan, along with four international experts. This panel was tasked with evaluating the design documents and impact assessments of the GERD to ensure the project’s safety, environmental sustainability, and equitable water use across all riparian states [

37]. In their final report, submitted in June 2013, the IPoE made several crucial recommendations, including the need for comprehensive and detailed Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs). They emphasized the importance of these assessments in understanding the potential impacts on downstream countries and recommended additional studies on the dam’s hydrological, environmental, and social impacts during and after construction.

The Technical National Committee (TNC), comprising representatives from the three countries, was then established in 2014 to oversee the implementation of the IPoE’s recommendations [

36]. The TNC’s role was pivotal in ensuring that all development stages of the GERD adhere to scientific findings and best practices in dam safety and water management. The process stalled, however, due to disputes over the selection of the international consultants that should carry out the needed studies [

38]. Egypt argued for a halt in construction until these impact studies were complete, a stance Ethiopia did not accommodate, leading to a stalemate in the committee’s progress.

Attempts to negotiate the GERD conflict between the three nations culminated in the 2015 signature of the Declaration of Principles (DoP), which provided a framework through which Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan pledged to utilize the Nile waters fairly and reasonably. The declaration, however, was vague in nature; it seemed that there were different assumptions regarding the legality of this agreement, as while Egypt and Sudan maintain that this declaration was legally binding, Ethiopia claims that it was simply a flexible, nonbinding agreement that does not prevent the government from completing the GERD project [

39]. Egypt and Sudan subsequently sought to reach a legally binding agreement that specifies the process of filling and operating the GERD, but Ethiopia rejected exactly that, claiming that any enforceable agreement is interference in a sovereign affair. Further, Ethiopia’s position is that the guidelines of the DoP are adequate and does not support signing a binding agreement that recognizes Egypt and Sudan’s established shares of the Nile [

40]. Instead, Ethiopia has been more open to a non-binding agreement that can be reviewed as needed [

41]. While maintaining this stance, Ethiopia has not provided a detailed legal argument to justify its refusal to sign a binding agreement. The absence of such legal substantiation underscored the need for further negotiation and legal clarity.

In 2018, these three countries established the National Independent Research Study Group in an attempt to discuss the filling and operation of the GERD; this study group, however, proved ineffective in reaching a consensus, leaving the three countries in a stalemate yet again [

31]. It is also important to note Sudan’s significant shift in opinion around this time: following the ousting of al-Bashir in 2019, Sudan realigned its position more closely with Egypt’s, insisting on reaching an agreement before allowing the dam’s filling [

34]. In October 2019, the US Treasury Department and the World Bank leveraged their influence to encourage the resumption of negotiations, emphasizing the importance of finding a fair and equitable resolution that addressed the concerns of all parties involved [

42]. On 28 February 2020, US mediators expressed optimism over the increasing potential for negotiations in addressing the GERD conflict [

43]; however, the raised aspirations for a possible resolution quickly dissipated when Ethiopia abruptly withdrew from the negotiations, refusing to sign the US-drafted agreement on the GERD operation and filling. Ethiopia viewed the draft as biased towards Egypt and Sudan and aimed to secure their contentious 1959 agreement [

44]. The US-led mitigation efforts, thus, proved unsuccessful, plunging the three nations back into what seems to be a never-ending state of water disputes.

In mid-July 2020, Ethiopia announced its unilateral decision to fill the dam, regardless of whether an agreement was reached by that time. Indeed, Ethiopia proceeded with the first phase of filling the reservoir in July 2020, collecting about 5 billion cubic meters of water in a week following the start of the rainy season. This decision led to significant concern amongst Egypt and Sudan, the latter of which suffered a drought, followed by flooding which officials claimed could have been avoided if Ethiopia had followed a more gradual approach to the filling of the dam [

45]. Additionally, Ethiopia faced negative repercussions from the US, which suspended

$130 million in foreign aid due to a lack of progress over the GERD dispute—a controversial decision that Ethiopia perceived as a way to impose a biased agreement in favor of Egypt [

46].

Little progress was made in the following years, with each country holding onto its stance and refusing to settle down on any negotiations. In July 2021, Ethiopia continued with the second phase of filling the dam. During this same month, the Egyptian Foreign Minister expressed strong opposition to Ethiopia’s actions at the United Nations Security Council, describing them as a “blatant act of unilateralism” and an “attempt to impose a fait accompli in defiance of the collective will of the international community” [

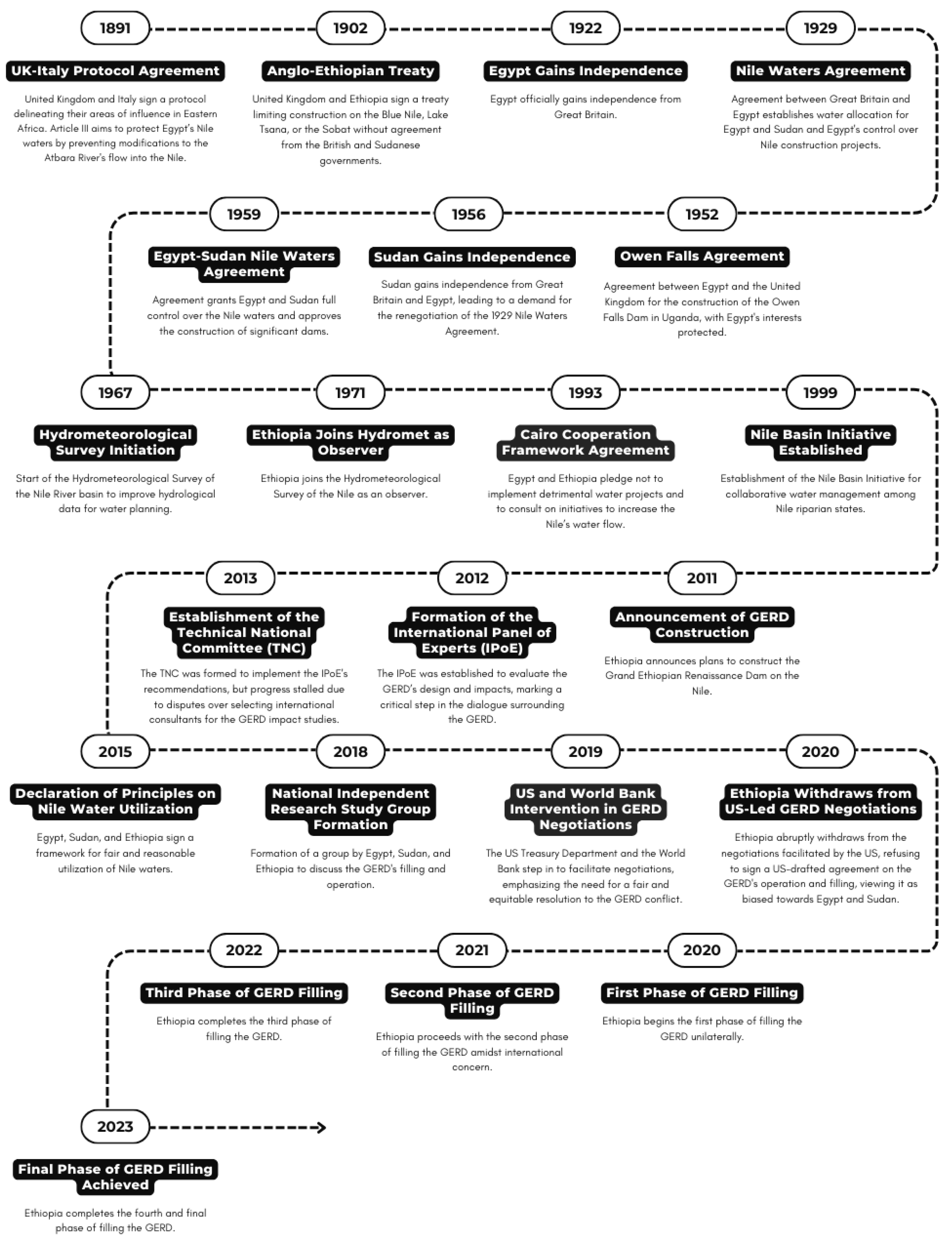

40]. The Sudanese Prime Minister also criticized Ethiopia’s actions, calling the second filling a “clear violation of international law and the Declaration of Principles.” As each of these countries exchanged criticisms without substantial progress towards a resolution, Ethiopia proceeded with its plans, completing the third phase of the filling in August 2022 and the fourth and final phase in September 2023. For a visual overview of the critical milestones in Nile Basin water politics and the GERD conflict, see (

Figure 1).

5. Current Status and Reflections

Building on the foundation laid by historical treaties, this section now turns to the contemporary dynamics surrounding the GERD. Analyzing the GERD conflict leads to a crucial conclusion: current water diplomacy measures in the Nile Basin are inadequate. An over decade-long attempt at negotiating a resolution between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan has thus far amounted to nothing. However, experts generally rule out the likelihood of military conflict over the GERD, pointing instead to the need for more refined water diplomacy measures and cooperative management of the Nile’s water resources [

4]. Proposals for data sharing agreements and joint operation of the GERD with Egypt’s Aswan High Dam have been suggested as ways of enhancing water availability and hydropower generation for both countries, emphasizing the potential for scientific collaboration to address the challenges posed by the dam [

47]. Despite these efforts, the path to consensus remains fraught with challenges. It is particularly important to highlight that the single most significant agreement reached throughout the conflict, the Declaration of Principles, ended up being a greater source of contention than of resolution. Professor of Politics and International Relations Dr. Khalil Al-Anani reflects on Egypt’s situation, noting that the signature of the Declaration of Principles was one of the strategic mistakes made by the country, as subsequently, Ethiopia refused to be bound by more concrete agreements. Ethiopia, he explains, took the Declaration of Principles as its green light to proceed with the construction of the GERD without having to clarify how it will safeguard the downstream nations’ water resources [

40]. Ethiopia’s unilateral decision to continually proceed with filling the dam reservoir over the years has been condemned by Egypt as “illegal”, exacerbating tensions and highlighting the difficulties in reconciling the developmental aspirations of upstream countries with the water security needs of downstream nations. The United Nations has noticed the urgency of the situation, warning that Egypt could face severe water scarcity by 2025, a scenario that could be further aggravated by climate change [

48]. Analysts have also expressed concerns that the dispute could escalate if no cooperative framework is established, emphasizing the need for sustained diplomatic efforts and international mediation [

49]. The increasing hydro-political risks in transboundary basins, exacerbated by climate change and population growth, underline the necessity of effective cooperative frameworks within which to manage conflicts like that faced by Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan [

14].

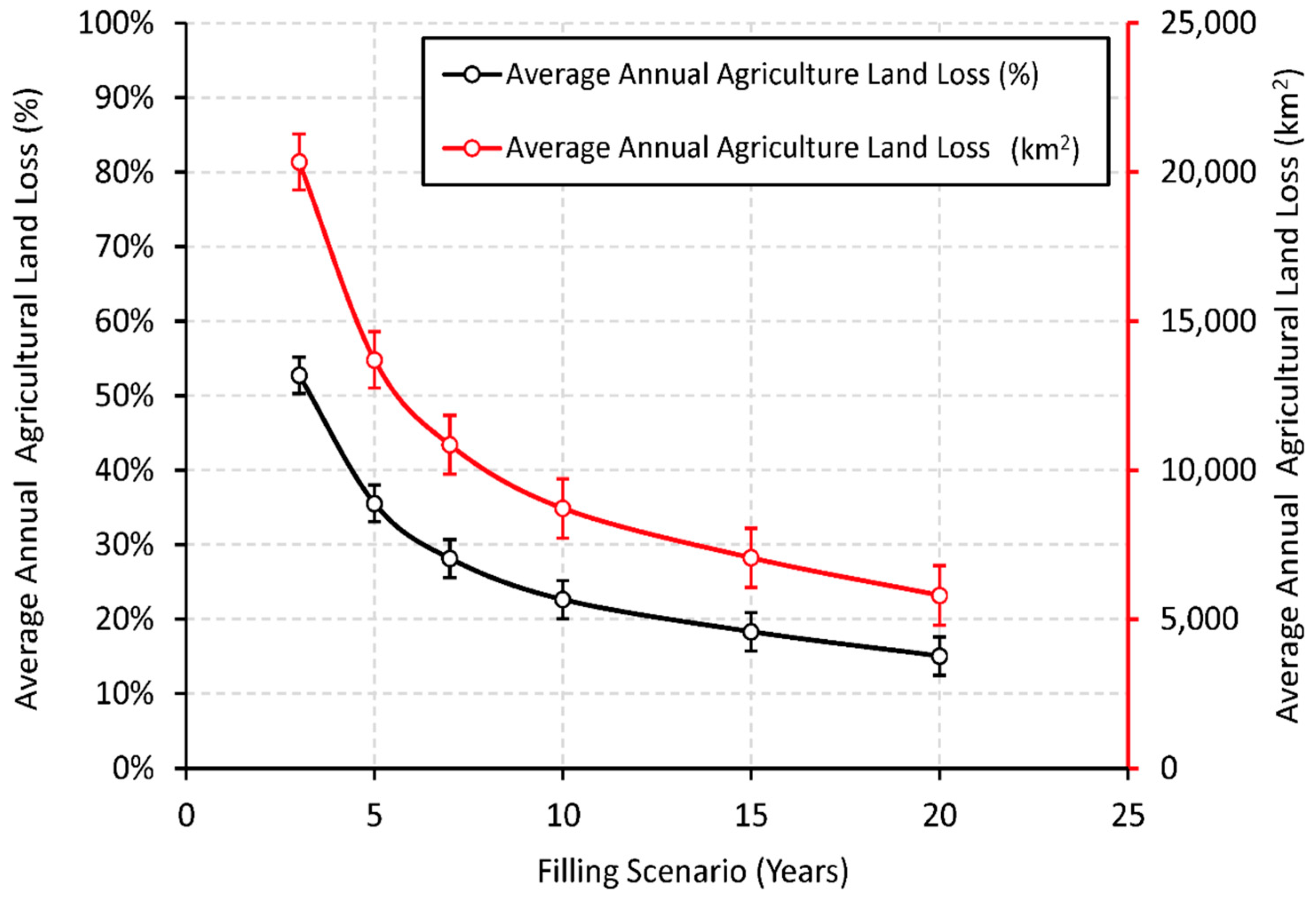

An investigation into the environmental and economic impact of the GERD was conducted by Kamara et al. [

50]. Specifically, they estimated Egypt’s projected losses from its annual Blue Nile water allocation based on three, seven, and ten-year GERD reservoir filling scenarios. Next, they analyzed Egypt’s agricultural land and macroeconomic variables in comparison with the absence of the GERD. (

Figure 2) and (

Figure 3) below demonstrate their findings in which short-term losses are more severe in terms of water loss, but less persistent than long-term losses. In comparison with longer filling periods, the expected impacts are relatively less severe; however, they are delayed for longer periods of time. As the authors point out, the graphs presented below represent the worst-case scenario in which the government does nothing to mitigate the situation. It is also clear that a similar trend was observed in Egypt’s loss of agricultural land, where it dropped sharply in the first five years and then continued to drop, but more steadily. This illustrates the severity and the consequences it will have on Egypt’s water distribution as a result of the GERD.

However, this study [

50] is part of a broader academic debate regarding the impact of the GERD on Egypt, which has sparked considerable controversy among scholars. Eladawy et al. [

51] criticize Kamara et al. for using what they consider unrealistic assumptions and data that lead to exaggerated estimates of the impact on Egypt. They argue that the projections of significant losses in Egypt’s agricultural land and economic output are based on flawed hydrological and economic models. Eladawy et al. [

51] highlight that Kamara et al.’s projections of water deficits under a three-year filling scenario, estimated to be 31 billion cubic meters per year, are based on misinterpretations of previous studies and overestimated evaporation and seepage losses. While Heggy et al. [

52] provide a critical examination of the assumptions underlying various GERD impact assessments, including those of Kamara et al., they argue that the selection of historical flow periods used in simulations significantly influences the projected downstream impacts. Heggy et al. [

52] advocate for using multiple flow sequences to accurately reflect the high interannual variability of the Nile’s flow, thereby providing a more reliable assessment of the GERD’s impact.

In fact, recent statistics on the Nile’s flow and the effects of the GERD from Egypt’s side are lacking; most data instead come from research projections like those of Kamara et al. Despite the lack of data, it has been clear that Egypt is exerting efforts to combat the consequences of the GERD filling by heavily investing in desalination [

53]. More recent research predicts that if the filling of the GERD proceeds at similar rates for another four years amid drought conditions, Egypt’s allocation of Nile water could decrease by around 35 percent. This reduction could then lead to an annual loss of agricultural land amounting to about 33 percent [

54]. The most recent official statistics, however, come from 2019, when Egypt’s annual share of Nile water decreased by 5 billion cubic meters, prompting a nationwide state of emergency, as declared by the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation [

55]. Eman el-Sayed, Head of the Planning Sector at the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation, noted in the statement that the flow of the Nile has been impacted by a reduction in annual rainfall originating from the Ethiopian Highlands (how the GERD played a role, if any, in the crisis was not explained). Egypt overall faced a water shortage of 21 billion cubic meters in 2019 [

56]. The UN even warns that Egypt could “run out of water” [

48] (p. 1) by 2025, with climate change compounding the crisis. However, more transparency and updated statistics are needed from Egypt to fully understand the severity of the situation and measure the accuracy of research predictions.

On the other hand, the GERD holds monumental significance for Ethiopia, a nation that has historically utilized less than 1% of the Nile basin’s water resources, despite the Nile constituting approximately 68% of its available water resources [

57]. To Ethiopia, the dam not only signifies a leap towards energy self-sufficiency but also embodies the nation’s sovereign right to utilize and manage its natural resources [

3]. This disparity demonstrates the complex hydro-political dynamics in which Ethiopia’s developmental gains are juxtaposed with Egypt’s water security challenges.

It is important to first reconsider the pre-established water treaties of the Nile, delineated previously. Ethiopia does not recognize the 1902, 1929, and 1959 treaties, claiming that they are non binding as they were made during colonial eras. The same kind of colonial-era treaties, however, established parts of Ethiopia’s lands, as when Great Britain granted Ethiopia the northeastern part of the Hawd Plateau, a traditional Somali region, in 1897 [

58]; these boundaries set during colonial eras are ones that the Somali government now refuses to acknowledge. Ethiopia is stressing the binding legality of colonial-era treaties against Somali claims based on self-determination. Therefore, it becomes clear that the argument surrounding “colonial-era treaties” can be adapted to fit various national narratives. This is not to say that Ethiopia needs to completely defer to the historic Nile water treaties—a reassessment of these agreements is indeed crucial for contemporary relevance and effectiveness. However, rather, opening the doors to better negotiations necessitates that Ethiopia recognizes the significance of these water treaties and why they have been established.

Water treaties surrounding the Nile Basin have historically acknowledged the fact that the importance of the Nile River and reliance on it varies significantly between an upper riparian nation and a lower riparian one. Unlike Egypt and Sudan, Ethiopia is not lacking in freshwater resources; river basins cover 94 percent of its land, with internal river systems spanning 28 percent of the country [

59]. On the other hand, over 50 percent of Sudan’s territory and 96 percent of Egypt’s land are desert [

60,

61]. Ethiopia takes pride in the fact that around 85% of the Nile waters reaching Egypt and Sudan come through its lands, but that is exactly why it should be more accommodating in negotiations surrounding the dam. Researchers are predicting that the GERD could cut Egypt’s annual water budget by around 31 billion cubic meters, over a third of Egypt’s current water budget; this could, in turn, lead to an alarming 72% decline in agricultural land and an increase in unemployment rates to 25%, as a fourth of Egypt’s workforce are in the agricultural sector [

52]. While Sudan has been assured with promises of enhanced electricity supply and improved water flow, the country is still inevitably expected to face the negative consequences of the GERD. Marc Jeuland, a Professor of Environmental Sciences and Policy at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, explains the effect of the GERD on flood recession agricultural practices in Sudan, noting that “this practice will no longer be viable once the GERD operates normally. Efforts should be made to provide alternative livelihoods for those affected” [

62]. Ahmed Al-Mofti, member of the Sudanese National Commission for the Renaissance Dam, has further highlighted that “Ethiopians did say they will provide Sudan with electricity, but they did not say it was going to be for free” [

62], putting into question the true intent behind the promises Ethiopia makes to Sudan. These potential consequences highlight the historical basis of water treaties, which have often urged upper-basin countries to avoid actions that might disrupt the flow of the Nile River. Crafting more inclusive and cooperative treaties will necessitate that Ethiopia, as an upper riparian nation, recognizes the importance of actions that ensure the continued flow of water to downstream nations.

Currently, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan need to channel more relevant efforts towards reaching an agreement over the regulation of the GERD’s operation—the question is no longer around whether or not the dam should exist. This requires the countries to demonstrate a willingness to negotiate and find mutual compromises, recognizing that there must be a viable solution to such conflicts. A key element that has been missing in the GERD conflict negotiations is the readiness of all involved parties to make concessions for the collective benefit. One of the key missing elements in the GERD conflict negotiations is the countries’ willingness to compromise for the greater benefit of all parties involved. Below, we delve into an analysis of how to potentially overcome the current deadlock.

5.1. Developing a New Treaty Framework (Based on the Declaration of Principles)

The Declaration of Principles (DoP) has faced challenges in effective implementation, largely due to its inherently vague nature. Recognized as an agreement rather than a binding treaty, the DoP has failed to adequately resolve the ongoing GERD dispute. However, it remains one of the few frameworks that has garnered mutual consent among the disputing nations. Given this rare consensus, it is strategic to develop a more robust and binding treaty that leverages the agreed-upon principles to address specific issues and operationalize commitments.

Below, we explore key principles from the Agreement on the Declaration of Principles [

63] and discuss their significance in forming a new, legally binding treaty.

5.1.1. Principle II: Development, Regional Integration, and Sustainability

According to the DoP, “The purpose of GERD is for power generation, to contribute to economic development, promotion of transboundary cooperation and regional integration through generation of sustainable and reliable clean energy supply”. This principle highlights that the core intent behind the GERD is not only energy production but also regional development and cooperation among the Nile Basin states.

This statement serves as a crucial reminder that the discourse surrounding the GERD should transcend political battles for supremacy. Instead, it should focus on a collective vision where each country’s developmental goals and sovereignty are respected and integrated into a broader regional strategy. This principle can thus act as a powerful incentive for Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan to transition from the existing DoP to a binding treaty: by framing a new treaty in terms of mutual benefits and shared goals, it reinforces that signing such an agreement is not a surrender of national rights but a commitment to cooperative regional development.

5.1.2. Principle III: Not Causing Significant Harm

This principle states that “The Three Countries shall take all appropriate measures to prevent the causing of significant harm in utilizing the Blue/Main Nile”. While it provides a foundation for cooperative water management, it suffers from a lack of specificity. In working towards a new treaty which is tailored specifically to the context of Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan, there is a unique opportunity—and indeed, a necessity—to refine and clarify this principle to avoid ambiguity:

Defining “All Appropriate Measures”

The DoP calls for “all appropriate measures” to prevent significant harm in utilizing the Blue/Main Nile, but these measures inherently differ due to the unique roles and responsibilities of each country involved with the GERD. This distinction is crucial and should be explicitly recognized and defined in a new treaty.

Ethiopia, as the host and controller of the GERD, bears the primary responsibility for its direct operational management. This could include adhering to agreed-upon water release schedules that do not adversely affect downstream nations and implementing environmental monitoring to assess any impacts caused by the dam’s operations. It would be imperative that Ethiopia’s measures are transparent and verifiable, given its exclusive control over the dam’s functionalities.

Sudan and Egypt, while not in control of the dam, have crucial roles in diplomatic engagement and adapting to the outcomes of its operation. Both countries must engage in active and constructive diplomacy to ensure their needs and concerns are addressed and align with the operational plans of the GERD.

Defining “Significant Harm”

In a new treaty, it is also equally important to clearly define what constitutes “significant harm”. The broad and subjective nature of the term can lead to differing interpretations among the three nations. To transform this principle into an effective and enforceable component of a new treaty, it is imperative to delineate specific, measurable, and agreed-upon criteria that clearly define what constitutes “significant harm”, some of which could be the following:

Quantitative Thresholds: Clear quantitative thresholds that define “significant harm” in terms of water flow reductions, pollution levels, and changes to water quality should be established. For example, a percentage decrease in water flow that triggers drought conditions in downstream countries could be classified as “significant harm”.

Ecological Benchmarks: Ecological benchmarks that must be maintained, such as minimum fish populations or specific water quality parameters essential for the health of aquatic ecosystems, should be defined. Disruption that leads to the failure to meet these benchmarks could be considered “significant harm”.

Socio-Economic Indicators: Socio-economic indicators, such as the impact on agricultural productivity, community displacement, or public health issues related to water scarcity or pollution, should be incorporated. Significant harm could be defined by thresholds in crop yield reductions, increases in waterborne diseases, or severe economic downturns linked directly to changes in the river’s management.

5.1.3. Principles V and VII: First Filling and Operation, Exchange of Information and Data

Principles V and VII from the Declaration of Principles refer to important requirements that are foundational to the operational and environmental integrity of the GERD. Principle V states that all three nations shall “implement the recommendations of the International Panel of Experts (IPOE) [and] respect the final outcomes of the Technical National Committee (TNC) Final Report on the joint studies recommended in the IPOE Final Report throughout the different phases of the project”. Additionally, Principle VII mandates that “Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan shall provide data and information needed for the conduct of the TNC joint studies in good faith and in a timely manner”.

However, the non-binding nature of the DoP has led to significant challenges in the implementation of these principles. The intent was for these principles to guide the coordinated and scientifically informed management of the dam’s construction and operation. However, significant discrepancies have emerged, particularly in Ethiopia’s adherence to the agreed processes. For instance, the failure to conduct timely transboundary Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs), as underscored by international law as well as the IPoE’s recommendations, has led to considerable contention. Ethiopia progressed with the dam’s construction ahead of comprehensive ESIAs and unilaterally continued with the dam’s filling phases, illustrating a departure from the collaborative spirit envisioned in the DoP [

64].

These challenges underline the critical need for a new, legally binding treaty that not only reiterates but also strengthens and enforces these commitments. The new treaty must, therefore, include enforceable mechanisms for data sharing that go beyond the stipulations of the DoP. This will involve the following steps:

Mandatory Data Sharing Protocols: The treaty should specify what data must be shared (including hydrological, environmental, and operational data), with whom they must be shared, and establish a timeline for regular updates.

Standardization of Data: To ensure that the data shared are uniform and comparable and to facilitate more accurate assessments of the dam’s impacts and operations, the treaty should establish standardized methods for data collection and reporting.

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms: The treaty must also establish clear and detailed processes for resolving disputes that arise from interpretations of data or scientific findings, including timelines and steps for escalation to neutral international arbitration if necessary.

5.1.4. Principle X: Peaceful Settlement of Disputes

Principle X states that “The Three countries will settle disputes arising out of the interpretation or implementation of this agreement amicably through consultation or negotiation in accordance with the principle of good faith”. While this principle sets a cooperative tone for dispute resolution, it lacks the detailed procedural guidelines. To strengthen this aspect in a new treaty, a comprehensive and clear dispute resolution framework is crucial. A new treaty should outline a specific, step-by-step arbitration process to manage disputes effectively. This process could include the following stages:

Initial Mediation: Upon the emergence of a dispute, the parties should first engage in a structured mediation process. A timeline for this phase should be established, ensuring that parties attempt to resolve their differences through dialogue within a set period (for instance, 60 days).

Escalation to Arbitration: If mediation fails, the dispute should automatically escalate to arbitration. The treaty should specify the criteria for appointing arbitrators, including their qualifications and the mechanism for their selection. Ideally, arbitrators should be chosen from an approved list maintained by a neutral international body to ensure impartiality.

Arbitration Rules: The arbitration process should be governed by predefined rules that are agreed upon by all parties. These might include procedural norms such as the venue of arbitration, the language to be used, the timeline for completion, and the method for implementing the arbitration award.

Involvement of International Bodies: In cases in which trilateral resolution efforts fail, the parties should have the option to involve international bodies such as the International Court of Justice or regional arbitration institutions. This involvement should be governed by mutual consent and adherence to international law.

Enforcement of Decisions: The treaty should clearly articulate the mechanisms for the enforcement of decisions arising from the arbitration process. It should also include provisions for appeal and review to ensure that all parties have the opportunity to contest the arbitration findings if they believe them to be unfair.

Good Faith Requirement: Reinforcing the principle of good faith, the treaty should include legal obligations for the parties to engage sincerely in each stage of the dispute resolution process, with penalties for non-compliance to discourage obstructive behaviors.

It is essential to also address some challenges that may arise in establishing a new treaty, as the process is unlikely to be simple. One of the primary challenges, as mentioned previously, is the nations’ lack of compromise due to nationalism, which even extends deeply into these nations’ general populations. Overcoming this requires a narrative shift towards highlighting the mutual benefits of cooperation and the collective gains in economic development and regional stability. Public awareness campaigns and educational programs can help to reshape national perspectives into a more collaborative mindset. These initiatives can be supported by local media, schools, and community leaders, emphasizing the shared cultural and historical connections between the Nile Basin countries and the mutual benefits of a cooperative approach. Political leaders must also play a crucial role in framing cooperation as a patriotic and strategic move rather than a concession.

Another significant challenge is the lack of accountability, which has thus far enabled unilateral actions by Ethiopia. This must be resolved through the new treaty itself by incorporating strict enforcement mechanisms and clearly defined consequences for non-compliance. Independent monitoring bodies, possibly under the auspices of international organizations such as the United Nations or the African Union, can ensure adherence to the agreed-upon terms. These bodies should have the authority to conduct regular inspections and audits, and their findings should be transparent and accessible to all parties involved. Additionally, the treaty should include provisions for sanctions or penalties for non-compliance, ensuring that there are tangible repercussions for any nation that violates the terms of the agreement.

Crafting a new treaty framework will undoubtedly be challenging, but it is essential for long-term stability and cooperation. Examining cases where water conflicts have been resolved through revising past treaties or creating new treaty frameworks offers valuable insights into the potential for successfully resolving the GERD conflict in a similar way. For instance, the Indus Waters Treaty [

65] between India and Pakistan has survived numerous conflicts and continues to function effectively due to its detailed guidelines and cooperative mechanisms. The treaty, facilitated by the World Bank, divided the Indus River system, allocating the eastern rivers to India and the western rivers to Pakistan, and established a Permanent Indus Commission for ongoing management and dispute resolution. Many disputes, such as those over the Baglihar Dam, were resolved through mechanisms provided by the treaty, including the involvement of neutral experts and structured arbitration processes [

66].

Another example is the Rhine River Treaties involving Germany, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg, particularly the 1999 Convention for the Protection of the Rhine, which built upon earlier agreements like the 1963 Bern Convention to address pollution and improve water quality. This convention established comprehensive measures for pollution control, ecosystem protection, and sustainable development, demonstrating how revising and enhancing past treaties can lead to significant environmental improvements and sustained cooperation. The collaborative efforts among the Rhine riparian states, such as through the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR), have led to significant improvements in water quality and ecological health, making it a model for transboundary water management [

67].

Similarly, the Mekong River Commission (MRC), established by the 1995 Mekong Agreement, showcases the benefits of a robust cooperative framework for sustainable management and development. The MRC has successfully fostered cooperation among Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam through joint management structures, regular data sharing, and basin-wide planning initiatives. Initially, the focus was on large-scale infrastructure projects like dams and irrigation systems, which often led to fragmented and unsustainable development. However, the MRC shifted to an emphasis on better management and preservation of existing resources, addressing contemporary issues like population growth, environmental preservation, and regional security. This shift involved revising the cooperative approach to include comprehensive management of the entire river basin, rather than isolated projects, leading to improved water quality, ecological health, and sustainable development [

68].

While the circumstances of the GERD dispute are different from these examples, these cases demonstrate that the formation or revision of treaties can lead to successful conflict resolution if the riparian states are willing to engage in such efforts. It is true that such treaties do not solve all disputes; for instance, the Indus Waters Treaty has not fully resolved issues related to India’s construction of new projects like the Kishanganga and Wullar Barrage, and the Mekong Agreement has faced challenges with dam construction and environmental impact assessments. However, these frameworks have resolved many conflicts and established mechanisms for cooperation, proving that with commitment and mutual trust, similar success could be achieved for the GERD dispute.

5.2. Mitigating Third-Party Intervention and the GMCR

The failure of third-party interventions, particularly by the US, can be attributed to perceived biases and geopolitical interests that undermine their effectiveness. Ethiopia viewed the US-drafted agreement as biased towards Egypt and Sudan, leading to their withdrawal from the negotiations and causing the talks to collapse [

44]. In terms of mitigating third-party intervention bias, recent research has put forward a novel approach to addressing these challenges. This research proposes an improved GMCR incorporating a revenue function [

15]. The GMCR is a conflict analysis method developed based on classical game theory. It simulates the dynamic evolution of decision-makers’ behaviors, offering a structured approach to understanding and resolving conflicts. The GMCR simplifies the modeling and analysis processes, requiring less input information compared to other models. It has been widely applied in various fields, including national security, climate change, air pollution, and water conflict.

Kevin Siqueira’s work on conflict and third-party intervention explores various scenarios in which third parties intervene in conflicts and the strategies they use to reduce overall conflict levels [

69]. His findings suggest that third-party interventions must consider both direct and indirect impacts of their actions on the involved factions. In the GERD conflict, a neutral and unbiased mediator can use strategies that focus on reducing the efforts and costs for all parties involved, fostering an environment conducive to cooperative negotiations. According to Lewicki and Sheppard [

70], the effectiveness of third-party intervention is significantly influenced by factors such as time pressure, expectations of future relations between disputants, and the broader impact of the settlement on future conflicts.

A key component of the improved GMCR is the revenue function, which objectively evaluates the relative preferences of different decision makers (DMs) involved in a conflict [

15]. The revenue function is designed to calculate the benefits and costs associated with each strategy adopted by the DMs, allowing for an accurate assessment of their preferences. This objective evaluation is crucial for understanding the dynamics of the conflict and identifying stable and mutually acceptable solutions. The revenue function is represented as follows:

where

Bi,j = the total benefits of DM i under strategy group j

Ii,j = the income of DM i under strategy group j

Ci,j = the cost of DM i under strategy group j

Strategy group refers to a specific combination of strategies chosen by all the DMs involved in the conflict at a given time. Each strategy group represents a unique state or scenario within the conflict model, where each DM’s chosen strategy is specified.

By calculating these values, the revenue function provides a clear picture of the economic incentives and disincentives associated with each strategic option, guiding DMs towards more informed decision making.

The GERD conflict involves multiple stakeholders, primarily Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan, each with distinct interests and concerns regarding the Nile’s water distribution. Adapting the GMCR to the GERD conflict involves several steps. The first step would be to identify the decision makers and the strategies. In this case, the decision makers are Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan, and potentially a neutral third-party mediator. Each DM has specific strategies, such as negotiation, unilateral action, seeking third-party mediation, or imposing sanctions. The second step would be to construct the revenue function. For each DM, the revenue function evaluates the benefits (e.g., water availability, agricultural productivity, hydropower generation) and costs (e.g., economic loss due to reduced water flow, environmental impact, political repercussions) associated with each strategy. Additionally, the revenue function is subjected to econometric testing to validate its accuracy and reliability. In the context of the GERD, this involves estimating the relationship between water flow variations and economic impacts, predicting future benefits and costs based on historical data, and assessing how changes in key variables affect the overall outcomes. This calculation allows for an objective assessment of each DM’s preferences, free from the biases that typically affect subjective evaluations. Using the identified strategies and calculated revenue functions, the GMCR simulates the dynamic interactions between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan. The model analyzes how changes in one DM’s strategy influence the others, mapping out potential pathways from conflict to cooperation. Consequently, the GMCR performs stability analysis to identify equilibrium states in which no DM has an incentive to unilaterally change their strategy. Various scenarios are simulated, such as different filling and operation plans for the GERD, to assess their impact on each DM’s preferences and the overall stability of the region.

To effectively apply the GMCR, it is also essential to identify conditions that favor collaboration and those that increase the risk of conflict and to establish diplomatic measures to balance these scenarios. Conditions that favor collaboration generally involve mutual economic benefits, data sharing, and joint management as well as environmental and social impact mitigation. In the context of the GERD conflict, a crucial aspect of applying the GMCR is comprehensive data collection, which heavily relies on the willingness of Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan to share data transparently. Key data points include water flow rates, seasonal variations, agricultural productivity, hydropower capacities, economic valuations, and environmental assessments. Collaboration with regional authorities, international organizations, and independent research institutions can additionally ensure data accuracy and reliability. All these elements are interlinked, as robust diplomatic efforts can facilitate collaboration, which in turn enhances the effectiveness of the GMCR in managing the GERD.

Conversely, conditions increasing the risk of conflict include unilateral actions, lack of transparency, economic disparities, and inequitable benefit distribution. As previously explained, establishing a binding agreement requiring all parties to participate in decision making processes related to the GERD can help mitigate this risk. Mediation by a neutral international body can additionally facilitate dialogue and focus on building trust through accountability mechanisms to foster a cooperative environment. Furthermore, integrating an eco-compensation mechanism into the negotiations could provide a practical solution to address benefit distribution. This mechanism would involve financial transfers or technical assistance to offset any imbalances caused by the GERD, ensuring that all involved countries benefit fairly from the project. Diplomatic negotiations should generally aim to ensure fairness and equity in terms of economic impact, which are essential for promoting stability and cooperation among the nations involved.

However, the grim reality is that there are scenarios in which the option of conflict might be more preferable for some parties. For example, if one country perceives that its vital national interests are threatened and cooperation does not offer sufficient guarantees to safeguard these interests, the country may prefer a confrontational stance. This could involve leveraging political, economic, or even military power to secure favorable terms. In such cases, the lack of viable diplomatic channels or trust-building mechanisms could make conflict a more attractive option. To balance these scenarios with diplomacy, it is essential to ensure that all parties recognize the long-term benefits of cooperation over the short-term gains of conflict. Revising the 2015 DoP and creating a legally binding agreement could potentially mitigate mistrust and maximize the efficiency of the GMCR, fostering a collaborative environment.

6. Conclusions

The GERD stands as a critical juncture in the history and future of Nile River diplomacy, embodying both the potential for regional development and the challenges of transboundary water management. This paper has traced the historical trajectory of water treaties in the Nile Basin, from colonial-era agreements to modern-day negotiations, clarifying the dynamic connection between historical legacies and current geopolitical realities. These treaties, often criticized for their exclusionary nature and inequitable provisions, have set a precedent that complicates contemporary water diplomacy efforts. Yet, they also offer valuable lessons on the importance of adaptability, fairness, and mutual respect in crafting agreements that can withstand the test of time and shifting political landscapes.

The GERD conflict represents the broader challenges of achieving equitable water distribution in a region where water is not just a resource but a lifeline. This paper has not only analyzed the conflict’s roots but has also delved into the potential pathways towards a sustainable and mutually beneficial resolution. It posits that the key to resolving the GERD dispute and advancing water diplomacy in the Nile Basin lies in transcending historical grievances and embracing a forward-looking approach that prioritizes shared benefits, ecological sustainability, and regional stability. Acknowledging the limitations of current diplomatic efforts, the paper argues for the development of a new, inclusive treaty framework or the development of already existing ones. This proposed legal structure advocates moving beyond colonial-era agreements towards a cooperative strategy for managing the Nile’s waters. Furthermore, it highlights the potential of unbiased third-party interventions to facilitate negotiations with the implementation of the GMCR, emphasizing the crucial role of equitable and sustainable water governance. In essence, the paper advocates for a collaborative resolution to the GERD conflict, proposing a shift towards agreements that balance developmental needs, environmental sustainability, and fair water sharing across Nile Basin countries. By drawing on lessons from other transboundary water disputes and adhering to established international legal principles, it outlines a strategy for more harmonious and effective water management in the region.

As this paper concludes, it becomes evident that the lessons obtained from the GERD conflict and the historical context of Nile water treaties are invaluable for navigating the complexities of transboundary water management. These insights not only illuminate the path toward resolving current disputes but also offer a blueprint for future water diplomacy endeavors. Whilst water has been a source of conflict over the course of history, it can be a source of reconciliation and harmony, as espoused by the United Nations’ theme of World Water Day 2024 being ‘Water for Peace’ [

71]. In facing the challenges ahead, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan—and indeed all Nile Basin countries—must seize the opportunity to redefine their water-sharing paradigms, ensuring that the Nile remains a source of sustenance, unity, and prosperity for generations to come.