Abstract

This study aimed to examine post-flood management, with a particular focus on enhancing the inclusivity of marginalised communities through stakeholder analysis. This study was based on an interpretivist mixed method approach, under which 30 semi-structured stakeholder interviews were conducted. Interest versus power versus actual engagement matrix, social network analysis, and thematic analysis techniques were employed under the stakeholder analysis tool to analyse the collected data. The findings highlight the lack of clearly defined responsibilities among key stakeholders. Marginalised communities and community-based organisations have a high level of interests but a low level of power in decision making, resulting in weak engagement and the exclusion of their perceptions. This lack of collaboration and coordination among stakeholders has made marginalised communities more vulnerable in post-flood situations, as their interests are not defended. The findings emphasise the importance of conducting stakeholder analysis in the decision-making process to enhance stakeholder engagement and interaction, as well as promote inclusivity of marginalised communities in the post-flood recovery efforts of the government. Finally, this study recommends developing strategies to improve collaboration among stakeholders, fostering inclusiveness and customising these strategies according to the different types of stakeholders identified through stakeholder analysis.

1. Introduction

Natural hazards are becoming increasingly common, unpredictable, and challenging due to rapid environmental and socio-economic changes at various levels [1]. Frequent disasters worldwide have caused enormous losses of life and property in society [2]. Sri Lanka has historically experienced various types of natural hazards; floods are one of the most common natural hazards that plague the country [3]. According to the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery [4] concerning the post-flood context, relief, rehabilitation, and recovery phases are complex and challenging, and perhaps the most critical challenge is to promptly determine humanitarian needs and provide lifesaving help to the people affected. Marginalised communities such as women, older adults, people with disabilities, and children [5,6] are seen as exposed to higher levels of risk and subsequently face the brunt of disasters harder than others [7].

According to Wickramasinghe [8], the breadth of the current community protection system is very limited, and the existing system does not adequately adapt to the real needs of marginalised communities in post-flood situations in Sri Lanka. Jovita [9] claimed that addressing the concerns of marginalised communities require actions not just on the part of the government but also on the part of other stakeholders. Local authorities in any country should consider individual communities often left out of planning discussions. It is to be anticipated that the same individuals will be less likely to participate in the disaster’s aftermath [10]. Both formal and informal networks already exist in society through charities, non-government organisations, and different forms of advocacy groups. These social institutions and networks have longstanding relationships and confidence in their participants, and, as such, can make effective and efficient decisions to reduce the risks of marginalisation after a disaster. Recovery planners can potentially benefit by collaborating with these existing networks to reach marginalised communities more effectively, a strategy that has also been implemented in other planning efforts [11]. It is critical to foster dialogue among all stakeholders to increase the involvement of marginalised communities throughout the post-flood management process.

However, the process of collaboration among stakeholders is often complicated due to different cultural, procedural, and system differences [12]; different motivations and incentives; competition for limited resources [13]; and the lack of coordination among stakeholders involved [12]. As a result, strengthening stakeholder collaboration is a crucial challenge in disaster management [14]. Recognising this challenge, priority number two of the Sendai Framework, which focuses on strengthening disaster risk governance, calls for national governments to strengthen cooperation among relevant stakeholders to manage risk effectively [15]. However, the recently published midterm review report of the implementation of the Sendai Framework emphasised that there are still gaps in effective stakeholder engagement in disaster management worldwide [16].

Abdeen et al. [14] have highlighted the need for effective and efficient stakeholder collaboration in disaster management in Sri Lanka. The flooding in 2017 resulted in the deaths of 219 people and the displacement of families of about 230,000 people, raising many concerns about the degree of collaboration among disaster management stakeholders [17]. In addition, the UNDRR [18] recognised a lack of coordination and information management among stakeholders in Sri Lanka in disaster risk reduction. This lack of coordination among stakeholders has become one of the main reasons for the exclusion of marginalised communities in the post-flood context. Mendis et al. [19] recently conducted a comprehensive analysis of the challenges faced by marginalised communities in the aftermath of floods. The study highlighted the need for stakeholder engagement at all levels in enhancing the decision-making process to promote inclusiveness and better interaction with stakeholders. Building on this, this study focuses on post-flood management and aims to examine how stakeholder analysis can be used to increase inclusivity for marginalised communities, considering Sri Lanka as a case in point. The aim of this study will directly align with the key priorities under the Sendai Framework—priority 1, understanding disaster risk; priority 2, strengthening disaster risk governance; and priority 4, “Building Back Better”—and will contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10, reduced inequalities and SDG 11, sustainable cities and communities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Post-Flood Management

The post-flood management process, as outlined by Jamali et al. and Malawani et al. [20,21], aims to restore normalcy to affected areas through various sequential phases after the occurrence of floods. These phases, namely relief, rehabilitation, and recovery, are crucial for addressing the immediate needs of communities, restoring essential resources and infrastructure, and facilitating long-term reconstruction and development efforts. The relief phase involves providing urgent assistance such as rescue operations, medical care, and restoration of basic services, and these are often coordinated by international aid agencies in large-scale flood disasters [22,23]. Subsequently, the rehabilitation phase focuses on temporary settlement and essential services like mass feeding, medical treatment, and initial infrastructure repairs, connecting the relief phase to long-term recovery [24,25]. Finally, the recovery phase entails extensive reconstruction efforts, capacity building, and addressing systemic issues to reduce the likelihood of future disasters [22]. However, the effectiveness of post-flood management initiatives can be compromised by social processes that result in inequality and marginalisation of communities [26].

2.2. Marginalised Communities and Inclusion within the Post-Flood Context

The phenomenon of marginalisation, characterised by limited opportunities and exclusion from societal choices due to factors like economic inequality and social discrimination [27,28,29], disproportionately affects vulnerable groups such as children, women, people with disabilities, and the elderly, and this is particularly evident in post-flood contexts in Sri Lanka [5,6]. These marginalised communities face heightened vulnerability during flood situations due to historical injustices and ongoing social exclusion, perpetuating socioeconomic disparities and hindering their ability to cope with and recover from disasters [30,31]. Inclusive approaches to flood management, emphasising equal rights and opportunities for all individuals and communities, are essential for building resilience and ensuring marginalised voices are heard and included in decision-making processes [32,33]. Achieving inclusion, however, remains challenging and requires concerted efforts from all relevant stakeholders to address systemic barriers and promote meaningful participation of marginalised communities throughout all stages of post-flood management [9,10,34].

Social protection is a crucial aspect of ensuring the well-being of individuals by preventing, managing, and mitigating situations that may have an adverse impact on their lives. It is deeply ingrained in the safeguarding policies of a country [8]. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka has a history of inconsistent policy engagement, particularly with changes in government, which has resulted in significant hardships for marginalised communities, particularly during disaster situations [6]. These communities have been unable to cope due to a lack of resources, support, and special attention from responsible stakeholders [35]. This highlights the need for a more comprehensive and consistent approach to social protection that accounts for the needs of all citizens, regardless of their socio-economic status.

2.3. Stakeholder Engagement in Post-Flood Management

According to Al-Nammari and Alzaghal [36], managing natural hazards has become a collective responsibility due to a global paradigm shift. This responsibility lies not only with governments at all levels but also with other stakeholders, including the community and private sectors. Stakeholders are entities with interests that are directly or indirectly affected by a system or policy, or they hold positions that require them to act as policymakers in the system. However, the involvement of various stakeholders makes the disaster governance system complex at all levels [12]. Therefore, to deliver appropriate disaster management services for the community, an effective disaster management system through proper stakeholder collaboration is required [14]. In addition, it has been recognised that during post-flood management all individuals and communities impacted by disasters should actively take part in decision making [37] to achieve more inclusivity.

In Sri Lanka, the Disaster Management Act No. 13 of 2005 established the Disaster Management Centre (DMC) as the coordinating unit for other stakeholders, along with the National Council for Disaster Management (NCDM), which consists of other national level stakeholders [38]. The stakeholders can be categorised into three levels, namely local, provincial/district, and national levels. At each level, there are three different communication and commanding lines between the stakeholders. They are top–down, bottom–up, and both ways. In the post-flood management processes, the bottom–up approach led by impacted communities has strong potential to help meet their needs [37].

The administrative structure of Sri Lanka is highly centralised and demonstrates several drawbacks. The involvement of a large number of agencies leads to a lack of “clear cut” responsibilities and the overlapping of responsibilities [39]. Moreover, as Amaratunga et al. [35] have claimed, since many disasters are local events, it is difficult to manage disasters only within a centralised system. A centralised system faces problems such as difficulties in identifying and providing solutions to localised problems. Therefore, when formulating policies, the focus of the central administrative structure is concentrated on the majority, with local needs, preferences, and opinions ignored. Ahrens and Rudolph [40] have also identified the requirement for a decentralised and efficient politico-administrative structure that supports local participation in order to be responsive to the local population, including the marginalised communities. Disaster management at present usually relies on a top–down approach. While a top–down approach has its advantages, disaster management should concentrate on establishing a bottom–up approach that uses local resources and capacities [41]. This is because a disaster is a local problem, and only the local communities can fully comprehend the challenges and opportunities associated with the disaster situation [21]. The inclusion of both the top–down and bottom–up approaches is a suitable approach to improve local disaster management, as suggested by Gaillard and Mercer [42]. Therefore, to develop an inclusive approach to disaster management that employs both top–down and bottom–up approaches, the participation of the local community in the decision-making process is crucial.

According to the mid-term review of the implementation of the Sendai Framework, there are still shortcomings in the effective engagement of stakeholders in disaster management around the world [16], which affect the management of flooding. This lack of coordination among stakeholders is one of the main reasons why marginalised communities are excluded after disasters [43]. Therefore, it is crucial to analyse stakeholder networks to improve the inclusivity of marginalised communities in the Sri Lankan post-flood context so that appropriate measures can evolve in the system to improve preparedness against future flood events. However, there is a lack of studies on the analysis of social and organisational networks in relation to disasters in Sri Lanka. Taking this as a primary impetus, the aim of this study is to carry out a stakeholder analysis to improve the inclusivity of marginalised communities in the post-disaster context, specifically considering recent flood hazards and considering Sri Lanka as a case in point.

3. Methodology

This study conducted semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders involved in flood management and marginalised community management under an interpretivist mixed method approach [44] to achieve the aim of the study. The adopted data collection and analysis process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data collection and analysis process.

Initially, the interview participants who were primarily responsible for handling the post-flood situations, handling the needs of marginalised communities, and representing the marginalised communities were chosen using purposive sampling technique. Purposive sampling involves selecting participants based on specific characteristics rather than random selection [45]. The purposive sampling technique was supplemented by the snowball sampling technique to increase the representation of relevant interviewees from national-level organisations, INGOs, and UN agencies. With snowball sampling, new participants can be recruited when current participants refer other potential participants to the study (e.g., as they are members of the same group or share similar interests that are relevant to the project at hand) [46]. The two selected participants representing the community were women community leaders who represented the marginalised communities, as they dealt with such communities from time to time as voluntary community workers. In addition, these women were personally responsible for caring for their older parents, aged 60 years and above, while raising their children. To further add, one of the two participants had a physical impairment and a disabled child, while the other participant’s husband was disabled. The profile of the respondents who participated in stakeholder interviews is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Profile of the respondents in the stakeholder interviews.

As shown in Table 1, 30 participants were recruited in the stakeholder interviews, whereby the saturation point was reached [47]. The saturation point in the data collection process can be divided into two categories: code saturation, which is achieved when no new issues are discovered, and meaning saturation, which is attained when no further insights are gained [48]. For further elaboration, researchers might reach a point of “code saturation,” where they feel they have heard everything, but they need to achieve “meaning saturation” to comprehend all the information [49]. In this study, code saturation was achieved after conducting 19 interviews, during which the range of thematic issues was identified. However, it was at the 30th interview that meaning saturation was reached, leading to the development of a richly textured understanding of the issues in this study.

The data collected through the stakeholder interviews was analysed through a stakeholder analysis (SA) technique [50,51]. The outcomes obtained from SA can provide information about (1) who will be influenced by programmes/policies, either positively or negatively [52], (2) who may have a positive or negative impact on the programme/project [53], (3) which individuals, groups, and institutions need to be involved in the programme/policy, and (4) who needs to build capacity to participate actively in it [54]. SA does not have a standard form, thus giving researchers the freedom to choose different analytical tools to analyse stakeholders [55]. As a result, interest versus power matrix, social network analysis (SNA), and thematic analysis techniques were employed under SA. In most studies, Misra et al. [56] found that thematic analysis and SNA are frequently used together. In addition, Ackermann and Eden [57] have identified power and interest as significant dimensions to identify stakeholder positions.

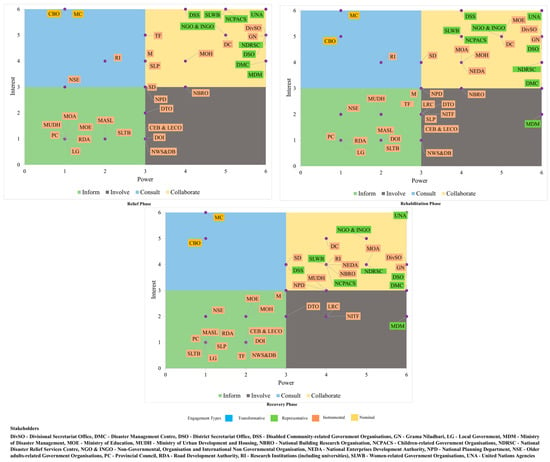

The semi-structured interview guideline was designed with open-ended questions to identify each stakeholder’s responsibilities and their engagement in handling the post-disaster needs of marginalised communities. In addition, the type of communication between each stakeholder, interest, and power in handling the needs of marginalised communities in the post-disaster context, as well as the engagement types of each stakeholder were identified via closed-ended questions. Power versus interest matrices were created (refer to Figure 2) to identify stakeholder positions on addressing the needs of marginalised communities in the post-flood context. To identify the levels of interest and the power of the stakeholders, Likert scale [58] closed-ended questions were asked (0 [no power] to 6 [very significant power], 0 [no interest] to 6 [very significant interest]). Interest and power were established through direct questions in the stakeholder interviews such as the following:

- How much power do you believe these stakeholders have to influence post-flood management efforts for marginalised communities?

- What is the interest level of these stakeholders in ensuring that marginalised communities are included in post-flood management efforts?

In addition, some indirect questions were asked to confirm the interest and power of the stakeholders.

- How influential do you believe these stakeholders are in decision making relating to post-flood management efforts for marginalised communities?

- To what extent do you feel these stakeholders’ resources and capabilities can be leveraged to support marginalised communities in post-flood management efforts?

- How important do you believe it is to consider the needs and concerns of marginalised communities in post-flood management efforts?

- What is the capacity of these stakeholders to influence post-flood management concerning marginalised communities?

- To what extent do you feel motivated to work towards ensuring that marginalised communities are included in post-flood management efforts?

The mode value of the respondents for each question was used to mark the matrix.

Under the power versus interest matrix, power refers to the ability of a stakeholder to affect the outcome of a situation or decision. Interest refers to a stakeholder’s level of concern about the issue at hand [54]. This matrix can assist in the categorisation of relevant stakeholders within its four quadrants, collaborate, consult, involve, and inform (refer to Figure 2). Stakeholders in the upper two quadrants are those with the most interest in affecting the marginalised communities in post-flood management but with varying degrees of power. Collaboration should take place with the stakeholders in the top-right corner, while the stakeholders who have high interest and low power need to be consulted. As for the two lower quadrants, they contain stakeholders with less interest in the system/project/programme. The involvement of the stakeholders in the bottom-right corner should be taken into the system/project/programme, and the stakeholders in the bottom-left corner should be informed on the management of marginalised communities in the post-disaster context [50,53,54,57].

As recognised by Reed et al. [53], the analytical power of approaches, such as the power versus interest matrix, can be improved by adding further attributes to the stakeholders. Therefore, stakeholder engagement types that include transformative engagement, involving stakeholders in all stages of decision making, from programme/policy design to maintenance; representative engagement, involving stakeholders in certain aspects of designing and implementing programmes/policies; instrumental engagement, programme managers viewing stakeholder involvement during post-flood management programmes as an efficiency measure towards an outcome, without extending their participation beyond this; and nominal engagement, where the stakeholder is visible in the decision-making process, as introduced by White [59], were incorporated in the power versus interest matrix to identify the actual engagement of the stakeholders as compared to their interest and power in managing marginalised community needs in the post-flood context (refer to Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Stakeholders’ interest versus power versus actual engagement matrix.

Social network analysis (SNA) was used to identify the networks of stakeholders who engage in post-flood management and marginalised community management (refer to Section 4.4). The SNA technique, named by John Barned, maps and measures relationships in a network of actors, formal and informal [60]. Recent disaster-related studies have been utilising SNA as a tool for evaluating the connections among different parties involved in implementing disaster management strategies [61,62,63,64]. However, there is a lack of studies concerning SNA in terms of improving the inclusion of marginalised communities in the disaster context.

In SNA, communication networks are depicted as a collection of nodes that are interconnected. In social networks, the concept of centrality is used to describe a parameter that denotes the most important, influential, and central nodes [65]. To understand the dynamics of a communication network, different centrality parameters are utilised. This study chose four centrality parameters as shown in Figure 1 (presented with justifications) to investigate the stakeholder network involved in post-flood management and marginalised community management.

In this study, the communication networks under SNA (refer to Figure 3) were developed using Gephi software, version 0.10.1 [66], which is a social network analysis open-source software. Before feeding the data into the software, an adjacency matrix was created in Microsoft Excel for all three post-flood management phases using binary units (1 = connection exists between two stakeholders; 0 = no connection between two stakeholders) [67] to identify the connection between the stakeholders. The results of the analysis discussed in Section 4.4 were classified into central parameter categories, highlighting the cooperation of key stakeholders in the network.

Figure 3.

Communication network diagrams of stakeholders involved in handling the post-disaster needs of marginalised communities.

Thematic analysis was used to examine the identification of stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities. Thematic analysis is a qualitative descriptive approach that involves identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data [68]. By extracting and analysing these themes, a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon being investigated can be gained, leading to rich and contextually grounded insights. The purpose of analysing qualitative data thematically is to provide an in-depth examination of the data, which, in turn, helps to enhance understanding and knowledge in a particular field [69]. In this study, this understanding and knowledge were achieved by identifying recurring patterns, trends of textual data, relationships, structures, and discourses [70,71,72] from the interview transcripts while providing comprehensive insights into stakeholder responsibilities.

4. Data Analysis, Research Findings, and Discussion

4.1. Thematic Analysis on Stakeholder Responsibilities in Handling the Needs of Marginalised Communities in the Post-Flood Context

In the aftermath of a disaster, marginalised communities are often the most vulnerable and in need of assistance. Effective post-flood management requires involving and coordinating various stakeholders, including governments, NGOs, local communities, and the private sector. The responsibilities of these stakeholders are crucial in ensuring that the needs of marginalised communities are met in a timely and effective manner. All the respondents believed that the success of post-flood management programmes was determined by the effectiveness of the collaboration and coordination among the many parties involved in these efforts. The different roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders engaged in post-flood management efforts in Sri Lanka are summarised in Appendix A. Except for the National Enterprises Development Authority (NEDA), the Land Reform Commission (LRC), and the National Insurance Trust Fund (NITF), all the other stakeholders are engaged throughout the post-flood context in disaster management initiatives.

Unfortunately, the Disaster Management Act of Sri Lanka does not give specific recognition to organisations representing marginalised communities as organisations responsible for post-disaster management. As commented by SI-1, the DMC has identified this issue and is working with the Ministry of Women’s Affairs to handle post-disaster-related work. There is an ongoing initiative to employ officers from organisations related to marginalised communities, such as the Women’s Bureau, to communicate disaster-related information to the relevant populace (SI-23). There are also ongoing training programmes to train officers to communicate with persons with disabilities in the context of the disaster. Since no government organisations are exclusively responsible for people with disabilities, this programme is carried out with the participation of NGOs.

In the relief phase, the information regarding the disaster situation of each district, including details on the established relief centres and the number of affected women, men, and children, are sent to the National Disaster Relief Service Centre (NDRSC) and DMC by the District Secretariate Office (DSO). Grama Niladari officers (village administrative officers) collect all relevant information in each division. DSO is responsible for coordinating all line departments, such as the electricity board, irrigation department, the water board, the road development authority, army, and police at the district level, in the conducting of post-disaster management efforts. Within the district level, the DSO, and at the division level, the Divisional Secretariate Office (DivSO) must carry a heavy burden of work throughout the post-disaster phases, as it must react at both the ground level and the national level to carry out post-disaster activities successfully.

Most people affected by disasters lose all of their means of subsistence, and they must restart their lives. Thus, the government and other aid agencies help them to return to everyday life by providing support and assistance for their livelihoods after the rehabilitation phase. They do not provide the same support and assistance for every district because the context, situation, needs, people’s skills, and abilities differ. In agreement with that, SI-21 highlighted that “we must assist them to help them recover based on what they require, what they are capable of, and what they have in their possession. For example, if we take a family from Wattala, a congested area, there is no point in giving them resources relating to the agricultural field, but they may require a sewing machine to support their sewing business”. Moreover, the aid agencies’ responsibility is to identify the community’s interests and skills, send them to vocational training as appropriate, and provide all other inputs and assistance in establishing livelihoods. In some cases, the government, with the aid of donors, NGOs, and INGOs, provides dry rations to entire families and also assists them by providing cash grants and support until they can return to work.

The “no one left behind” concept [15] is crucial in disaster management. To achieve this concept, organisations at the national level should prepare comprehensive, inclusive policies and frameworks, and, also, those at the district level should be aware of these since the implementation of these policies is undertaken by them and the impact is at the local level. Therefore, local-level information should be gathered in order to make more comprehensive decision making at the national level. Furthermore, the top levels should adhere to assigned roles and responsibilities until the community realises the full benefit of post-disaster rebuilding policies and frameworks. According to Atkinson, local governments play a crucial role in responding to disasters, especially in the relief phase [73]. However, some respondents claimed that the support from the local level officers is low in terms of implementing policies and frameworks (SI-1, SI-2, and SI-5).

Stakeholder responsibilities are considered successful when roles and responsibilities for addressing any particular issue are clearly assigned among stakeholders [74,75]. When this is achieved, post-flood management efforts are expected to show measurable improvements in the inclusion of marginalised communities. To ensure continuous improvement, benchmarks for progress should be established through measurable indicators [74] and evaluated for all projects. However, the key findings of the thematic analysis uncovered the fact that there is a lack of clearly defined roles and responsibilities among most of the key stakeholders in terms of enhancing the inclusivity of marginalised communities in post-flood situations in Sri Lanka. The Disaster Management Act of Sri Lanka does not recognise the organisations representing marginalised communities as key stakeholders in post-flood management. This lack of recognition has contributed to a lack of collaboration and coordination among the stakeholders in effectively and inclusively involving themselves with post-flood management. Therefore, the study findings illustrate that the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders need to be re-examined and clarified through the policy framework to ensure that everyone works towards the same goals. By doing so, the recovery process can be more effective, and the needs of the marginalised communities can be better identified and addressed.

4.2. Power Versus Interest Versus Actual Engagement Matrix

4.2.1. Power Versus Interest of Stakeholders in Managing the Needs of Marginalised Communities in the Post-Flood Context

After identifying the stakeholders and their roles and responsibilities, the power versus interest matrix in line with the actual engagement of stakeholders was established and is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows how the stakeholders are positioned in managing the needs of marginalised communities in the post-flood context. There are stakeholders representing all the four quadrants: collaborate (high power, high interest), consult (low power, high interest), involve (high power, low interest), and inform (low power, low interest) (refer to Section 3). It can be observed that the “collaborate” quadrant, where players are located [50], is densely populated compared to other quadrants, indicating that the majority of the stakeholders have high power and high interest in managing the needs of marginalised communities in the post-flood context. It is evident in Figure 2 that the interest and power of most of the stakeholders to improve the inclusion of marginalised communities is higher in the relief phase compared to the rehabilitation and recovery phases. However, it has been reduced in the recovery phase more than in the other phases.

Stakeholders primarily managing post-flood situations, such as the DMC and the NDRSC, have high power and interest in managing the needs of marginalised communities in the post-flood management context. The National Building Research Organisation (NBRO) primarily provides required technical support for resettlement, and they have high power and interest in managing the needs of marginalised communities in the recovery phase compared to the other two phases. Research institutions (RIs) that provide valuable data, analysis, and recommendations to inform decision making have high interest and low power during relief and rehabilitation phases, whereas they have high interest as well as high power in the recovery phase. In addition, the stakeholders who are primarily managing the needs of marginalised communities, such as the Sri Lanka Women’s Bureau (SLWB), the National Child Protection Authority and the Children’s Secretariat (NCPACS), and the Department of Social Services (DSS) also have high interest and high power in providing post-disaster needs. However, their power becomes less pronounced than their interest in the post-disaster context. Confirming this, SI-15 claimed that “there is an issue with the resilience capacities of our government women-related organisations. We do not have facilities to handle all the needs of women in post-disaster situations continuously. This kind of issue has led to a lack of resilience of the concerned community in a disaster situation”. Additionally, as a situation transitions from the relief phase to the recovery phase, it becomes apparent that those above-mentioned marginalised community-related organisations’ previous levels of power and interest significantly decreased. It appears that they are not as invested in their contribution in the recovery phase as in the relief and rehabilitation phases. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the power and interest of the National Secretariat for Elders (NSE) are low in the post-disaster context, and they are placed in the inform quadrant, although they should be in the collaborate quadrant.

The stakeholders who closely interact with the marginalised communities in day-to-day life, the GN, the DSO, and the DivSO, also have high interest and high power, as do the UN Agencies and the NGOs and INGOs. Tri Forces (TF) and the Sri Lanka Police (SLP) are also engaged in providing much of the relief effort while undertaking search and rescue for the affected community. They are also in the top-right quadrant of the matrix, denoting high power and high interest in managing the needs of marginalised communities in the post-disaster relief phase. In addition, the interest and power of the Ministry of Education (MOE) is higher in the rehabilitation phase compared to the other phases since they are especially involved in rehabilitating and continuing the education of affected children after disasters. The National Enterprises Development Authority (NEDA), which provides small- and medium-scale livelihood assistance, has high power and interest in addressing the needs of marginalised communities, especially women and people with disabilities in the post-disaster rehabilitation and recovery phases.

It can be seen in Figure 2 that the “collaborate” quadrant is occupied by the most important stakeholders in handling the post-disaster needs of marginalised communities, except for the marginalised communities (MCs) and the Community-Based Organisations (CBOs). It is important to note that the MCs and CBOs that advocate for them have minimal power to engage in decision-making processes and advocate for their own needs during the post-disaster period, despite their high level of interest. As a result, these communities, the most impacted by disaster incidents, often face difficulties in having their voices heard and their needs addressed.

After thoroughly evaluating the power dynamics and levels of interest of various stakeholders involved in the post-disaster scenario in Sri Lanka, it is evident that certain modifications need to be made to their existing positions to ensure that marginalised communities are given ample opportunities to participate and contribute.

While determining both the interest and power of different stakeholders, their actual conduct in addressing the needs of marginalised communities must be evaluated with care and attention.

4.2.2. Actual Engagement of Stakeholders in Managing the Needs of Marginalised Communities in the Post-Flood Context

Stakeholders play a crucial role in handling the needs of marginalised communities in the post-disaster context [15]. As explained by White [59] (see Section 2.1), stakeholder engagement can be categorised into different forms of behaviours, such as transformative, representative, instrumental, and nominal. Two critical factors affecting their engagement are their power and interest levels in the issue [60]. After clarifying the power and interest of stakeholders, their actual engagement in managing the needs of marginalised communities is examined (refer to Section 3).

As shown in Figure 2, it is significant that all the stakeholders have the same type of engagement in the post-flood context. The analysis of stakeholder interest, power, and their level of engagement demonstrates that despite the significance of power and interest as critical factors that affect actual engagement, most of the key stakeholders’ engagement levels do not align with these factors. For example, when power and interest are high and disaster management or managing marginalised communities is considered the primary job role of a specific stakeholder, they should engage in a transformative manner. This involves the stakeholder participating in all the decision-making steps, from design to post-disaster maintenance, with empowerment. However, there are no stakeholders represented in transformative engagement. UNAs, NGOs and INGOs maintain representative engagement throughout the post-disaster context. However, it was revealed that these stakeholders lean towards transformative engagement. The key stakeholders, such as the DMC, NDRCS, NBRO, DSO, DSS, SLWB and NCPACS, which manage post-disaster efforts and the needs of marginalised communities, are not involved in all the decision-making steps. They only maintain representative engagement, with their voices only considered in decision making. DivSO, while maintaining a close relationship with the community, has demonstrated a valuable commitment to efficient engagement in post-flood management initiatives. However, DivSO has not played an active role in the decision-making processes for addressing the needs of marginalised communities. Their understanding of the importance of inclusivity remains inadequate. According to SI-3, although there is some consideration of women, children, and persons with disabilities during the post-disaster relief phase, the rebuilding programmes at the divisional level do not prioritise inclusivity.

SI-14, representing stakeholders focused on women’s issues, reports on the presence of officers at both the DSO and DivSO levels responsible for collecting data on women and children impacted by disasters. This information is then relayed to the DMC so they can provide specialised care to those requiring additional attention, such as pregnant or breastfeeding women, in the relief phase. In cases where further support is necessary, communication with the DMC and relevant NGOs is established to address these needs. In addition, counselling services to address potential mental health concerns, law assistance, and livelihood-related support are also available. Unfortunately, no special attention is given to specific women’s categories (such as widows and older unmarried women) in addressing post-disaster needs. Additionally, disabled women are not given any special consideration when it comes to the provision of sanitary supplies. To address this issue, it would be necessary to include provisions for tailored sanitary supplies within the national plan. However, the current plan does not outline any specific actions to be taken in such cases, and there is no established protocol for supplying disabled women with specialised sanitary items. Typically, the funds allocated for such situations are designated for food supplies, relegating the decision to the managing officer to purchase additional necessary items. In addition, SI-14 formally requested the Ministry of Disaster Management (MDM) to include women in disaster management efforts at the community level and incorporate women-related CBOs in planning and other related disaster management work at the same level.

The NSE, the primary stakeholder that addresses older adults’ needs, maintains an instrumental engagement. Although their involvement in post-flood management initiatives is primarily viewed as an efficient measure to include older adults in post-flood management programmes, it is essential to note that their contribution does not extend beyond this perspective. Despite their potential to offer additional value to the programmes, their role remains limited to providing operational support to older adults, not primarily in post-disaster situations.

Figure 2 illustrates that despite their high level of interest, marginalised communities and community-based organisations have minimal power to engage in decision-making processes during the post-disaster phases. Additionally, it shows that their engagement is nominal, meaning that they are simply visible in the decision-making process without having substantial influence on the outcomes. This lack of meaningful participation can perpetuate systemic inequalities and exacerbate the challenges marginalised communities face.

Leaving aside the above-discussed stakeholders, all the other stakeholders engage in post-flood management programmes via instrumental behaviour, which is sufficient for managing marginalised community needs. However, stakeholder engagement indicates that there should be a significant change in the engagement types of all the other key stakeholders to improve the inclusivity of marginalised communities in the post-disaster phases. Significant changes in the types of engagement used by key stakeholders that result in the better inclusion of marginalised communities in post-flood situations are considered a success in stakeholder engagement. Additionally, inclusivity can be gauged by indicators like equal access to relief services for all members of the community, the chance to participate in decision making, and the satisfaction of the community with the recovery process. Nevertheless, the inclusion of marginalised communities in post-flood management is often viewed as an additional task, resulting in less priority being given to these efforts by some of the stakeholders (LG, PC, and NSE). This tendency towards placing a lower priority on inclusive practices can have detrimental effects on the overall management of post-disaster activities. It is essential for stakeholders to recognise the critical role that inclusivity plays in post-flood management and to prioritise these efforts accordingly. Failure to do so can negatively impact the affected communities and hinder the overall recovery process.

4.3. Stakeholder Network Analysis (SNA)

SNA was performed to identify the communication networks among the stakeholders that engage in post-flood management and marginalised community management. The communication networks of stakeholders involved in addressing the needs of marginalised communities during the post-disaster relief, rehabilitation, and recovery phases are illustrated in Figure 3. Figure 3 was developed using Gephi 0.10.1 software (refer to Section 3 for an explanation of the adopted methodology). The stakeholders are depicted as nodes in the visual models, with varying node sizes and colour densities indicating their Eigenvector centrality values, which determine the most influential stakeholders in the network. The thickness of the edges connecting the nodes represents the strength of the relationships among the stakeholders.

In addition, using the centrality parameters described in Figure 1, the stakeholders were ranked to identify their significance and roles in the communication networks. The top three stakeholders under each centrality parameter are shown in Table 2 for each of the three phases. Both Figure 2 and Table 2 highlight the finding that DMC, NDRC, and DSO are the key significant stakeholders in all three phases of post-disaster management.

Table 2.

Top-ranked stakeholders under centrality parameters.

Centrality measures were employed to identify the most central actors [66]. The significance of the stakeholders can be initially evaluated using the Weighted Degree Centrality parameter. Interestingly, the DSO, DMC, and NDRSC consistently emerge as prominent figures throughout all three phases. Their high Weighted Degree Centrality scores suggest that they have extensive direct connections in the network. In the relief phase, this indicates their critical roles in coordinating immediate assistance efforts. However, what stands out the most is the consistency of their centrality during the rehabilitation and recovery phases. This persistence emphasises their enduring significance in facilitating both immediate and long-term recovery for marginalised communities.

The Closeness Centrality metric sheds light on how easily stakeholders can access others in the network. The DSO and DMC demonstrate the highest scores for Closeness Centrality in the relief phase, indicating their ability to tap into information and resources quickly. The NDRSC follows closely, highlighting its effective outreach. Interestingly, this trend persists during the rehabilitation and recovery phases, indicating that these stakeholders maintain their capability to navigate the network efficiently, regardless of the phase.

Identifying stakeholders who act as intermediaries or connections between others in the network is what the Betweenness Centrality parameter does. In the relief phase, the DSO, NDRSC, and DMC again appear as key figures, highlighting their essential role in facilitating communication and resource flow among stakeholders. This intermediary role remains significant in the following phases, underscoring their continued significance in promoting collaboration and coordination.

Regarding the Eigenvector Centrality parameter, it considers both a stakeholder’s connections and the importance of those with whom they are connected. During the relief phase, the DMC, DSO, and NDRSC demonstrated the highest Eigenvector Centrality scores, implying their connections to other influential stakeholders. This same trend is evident in the rehabilitation and recovery phases, which suggests that these stakeholders are not only well connected but are also linked to influential actors within the network.

The SNA highlighted the crucial and multifaceted roles played by the DSO, DMC, and NDRSC in the disaster management of marginalised communities in Sri Lanka. Their adaptability and versatility in addressing the diverse needs of marginalised communities are evident in their consistent prominence across various centrality measures and phases. These stakeholders are key players in the network, both directly engaging with others and facilitating collaboration and information flow. Nevertheless, their engagement in post-flood management efforts is only representative (refer to Figure 2). Therefore, it is important for policymakers and authorities in charge of flood management to create and put plans into action that focus on improving the abilities of these key stakeholders and encouraging collaborative partnerships between them to render their engagement transformative.

The SNA revealed a significant decrease in coordination among stakeholders and the strength of their connections from relief to recovery. This lack of coordination has implications for the effectiveness of the recovery efforts. The connectivity and engagement of key stakeholders such as the affected community (MCs), CBOs, marginalised community-related stakeholders (SLWB, DSS, NCPACS, and NSE), NGOs, INGOs, and UNAs are weak within the network. The Betweenness Centrality parameter of the NSE is zero throughout the post-disaster context, implying that it has no authority to connect organisations. Therefore, the NSE is not able to mediate opinions or control the flow of information. This can be one of the primary factors for the neglect of elderly individuals during post-flood scenarios.

Provincial Councils (PCs), Local Government (LG) bodies, and the GN have been found to exhibit low scores in terms of Closeness Centrality and Eigenvector Centrality. This indicates that these stakeholders have a limited capacity to access information and resources swiftly and have fewer connections to other influential stakeholders. As a result, they face challenges in effectively engaging with other key players in the network and exerting their influence in decision-making processes. It has been revealed that communities are more closely associated with PCs, LGs, and the GN; hence, the involvement of the local government in the decision-making process is highly beneficial for enhancing the inclusivity of marginalised communities.

Therefore, it is crucial to identify the current network of stakeholders to pinpoint any deficiencies in the network and to suggest new approaches to enhance the involvement of marginalised communities. Success in engaging stakeholders entails accurately outlining the current network of stakeholders involved in flood response and recovery, detecting any inadequacies in collaboration, and recommending new engagement avenues that promote the inclusion of marginalised communities. Such an approach is beneficial in enhancing disaster resilience and promoting community cohesion and equitable participation in flood management and recovery efforts.

4.4. Discussion

Under this section, a comprehensive discussion is presented, focusing on the criteria for evaluation in this study, key observations gleaned from the research findings, and actionable recommendations tailored to affect stakeholder management as concerns inclusive post-flood management, while relating to the existing literature. A summary of the discussion points is depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Criteria for evaluation, key observations, and recommended actions.

Table 3 outlines the criteria for evaluation discussed throughout this study, key observations, and recommended actions derived from the research findings and literature findings. This analysis helps to identify areas for improvement and provides actionable recommendations for effective stakeholder management for inclusive post-flood management.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented an analysis of stakeholder engagement with marginalised communities in a post-flood context. To achieve this, stakeholder analysis was conducted to identify stakeholders involved in addressing the needs of communities. The analysis revealed that while several stakeholders are engaged in post-flood management efforts, there is a lack of clearly defined responsibilities among most key stakeholders. This finding suggests that the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders need to be re-examined and clarified to ensure that everyone works towards the same goal.

Subsequently, interest versus power matrices revealed that despite having high levels of interest, marginalised communities and community-based organisations have a lack of power in the decision-making process, and their actual engagement is nominal, with their engagement only visible in the decision-making process. The matrices developed confirm the marginalisation of women, people with disabilities, and older adults in post-flood situations. This is concerning, as marginalised communities are the ones most affected by disasters, and the exclusion of their perceptions in the decision-making process has made them more vulnerable. As per the research findings, the weak engagement of these communities in the stakeholder network has resulted in a lack of collaboration and coordination among the different stakeholders involved in the post-flood management process. Therefore, it is essential to highlight the importance of improving the participation of marginalised communities in the decision-making process of the governing bodies in Sri Lanka. By involving these communities, their voices and opinions can be heard, and their needs and concerns can be adequately addressed. According to the assessment, the government stakeholders under the category of “older adult” among the marginalised communities have relatively low dynamics of power and interest compared to other key stakeholders who have a high degree of power and interest in promoting inclusivity. Still, the actual engagement of these key stakeholders in handling the post-disaster needs of marginalised communities is lower than expected, which does not align with their high levels of interest and power. It has been reported that various stakeholders have made several efforts to improve the inclusivity of marginalised communities in the post-disaster context. However, the continuity of these efforts has been a persistent issue. Therefore, to improve the inclusivity of marginalised communities in post-flood contexts, this study revealed the critical need for a significant change in the collaboration and engagement of key stakeholders, including those involved in disaster management, in the management of marginalised communities, NGOs/INGOs and UN organisations (those based in Sri Lanka), and the affected community to improve the inclusivity of marginalised communities.

In essence, the stakeholder analysis conducted has opened pathways to move beyond surface-level observations of the exclusion of marginalised communities in post-flood contexts, while uncovering the existing behaviour and engagement of all the engaged stakeholders involved in post-flood management efforts. This crucial finding highlights the importance of developing and implementing targeted interventions and strategies that can prioritise the voices and needs of marginalised communities in the post-flood context. This study contributes to the literature on disaster resilience by carrying out a stakeholder analysis to support ameliorating inclusivity via effective stakeholder management. In addition, the explorations of this study align with the Sendai Framework and contribute to achieving several SDGs. The findings on stakeholder collaboration contribute to Sendai Framework priority 1—understanding disaster risk by fostering better communication and collaboration among stakeholders, which can improve flood management efforts—a key aspect of SDG 11, sustainable cities and communities. Furthermore, inclusive community engagement aligns with Sendai Framework priority 2—strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk by ensuring the affected communities should be involved in decision-making processes, leading to more effective responses. Ultimately, this study promotes inclusive and equitable post-flood management, leaving no one behind (SDG 10: reduced inequalities) and contributing to a more resilient future as outlined in Sendai Framework priority 4, “Building Back Better”.

As theoretical implications, this study emphasises the importance of analysing interest, power, and actual engagement in a single matrix in stakeholder analysis to identify the existing positions of stakeholders. In addition, the research findings can be instrumental in shaping policies and guidelines for post-disaster management efforts that promote inclusivity via effective stakeholder management. SA application can have significant practical implications for disaster management professionals, policymakers, and governments worldwide to develop inclusive strategies and improve connections among stakeholders, as well as foster inclusiveness while promoting equity and social justice in disaster management and beyond. Overall, promoting inclusivity can help build a stronger, more cohesive, and integrated society, especially in post-flood contexts in the long term.

This research plays an important role in informing some of the existing government policies related to maintaining inclusivity of community participation in post flood management. Another valuable area of research that can emerge from this could be to extend further studies into a more macro-level work, focusing on conducting comparative studies of stakeholder analysis in various regions or countries to improve the inclusivity of marginalised communities in post-flood contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M., M.T. and Y.K.; methodology, K.M. and M.T.; software, K.M.; validation, M.T., Y.K. and B.I.; formal analysis, K.M.; investigation, M.T. and Y.K.; resources, M.T., Y.K. and B.I.; data curation, K.M., M.T., Y.K. and B.I.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, M.T., Y.K. and B.I.; visualization, K.M.; supervision, M.T., Y.K. and B.I.; project administration, M.T., Y.K. and B.I.; funding acquisition, B.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research England, London South Bank University, UK—Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) for the Gender and Disability Inclusion in Post-Disaster Rebuilding project in Sri Lanka (AY 2020-21 QR GCRF-1169), research funding received from Manchester Metropolitan University, UK and UKRI/GCRF funded ‘Technology Enhanced Stakeholder Collaboration for Supporting Risk-Sensitive Sustainable Urban Development’ (TRANSCEND) [ES/T003219/1], University of Salford, UK.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted under the ethics code requirements of the University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, and was approved by the University Ethics Review Committee (UERC) with ethics declaration/clearance number ERN/2022/003 and 24 November 2022 as the date of approval.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to an author's ORCID. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in handling the needs of marginalised communities in the post-flood context.

Table A1.

Roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in handling the needs of marginalised communities in the post-flood context.

| Stakeholder | Shortened Name | Roles and Responsibilities Concerning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relief | Rehabilitation | Recovery | ||

| Ministry of Disaster Management | MDM | Functioning as the central coordinating agency with its agencies, which are the DMC, NBRO, and NDRSC. | ||

| Disaster Management Centre | DMC | Carrying out the main coordination and collaboration efforts with relevant stakeholders. | ||

| Establishing emergency shelters and providing essential relief items such as food, water, and medical supplies to affected people. Conducting rapid assessments of the extent of the damage and the needs of the affected population. | Coordinating and managing the medium-term rehabilitation efforts to restore essential services and infrastructure. Supporting the restoration of damaged infrastructure and homes. Providing financial assistance and support to those affected by the disaster to help them rebuild their lives. | Developing and implementing policies and strategies to improve disaster preparedness and response in the future. | ||

| National Building Research Organisation | NBRO | Providing technical advice and guidance to the government and other relevant stakeholders. | ||

| Conducting rapid assessments of the disaster risk in affected areas. Supporting search and rescue operations by identifying high-risk flood areas and providing recommendations on safe access routes. Identifying and assessing the risk of potential secondary hazards such as debris flows and floods triggered by aftershocks. | Conducting detailed assessments of the flood risk in affected areas. | Supporting the long-term recovery and housing reconstruction efforts in affected areas. Developing guidelines and standards for flood-resistant construction practices and providing training to the construction industry and relevant stakeholders. Monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of the flood risk reduction and management strategies implemented. | ||

| National Disaster Relief Services Centre | NDRSC | Coordinating and managing the immediate response to the disaster by mobilising and deploying emergency response teams and relief supplies to affected areas. Establishing emergency shelters and providing essential relief items such as food, water, and medical supplies to affected people. Conducting rapid assessments of the extent of the damage and the needs of the affected population. | Coordinating and managing the medium-term rehabilitation efforts to restore essential services such as water, electricity, and transportation. Supporting the restoration of damaged infrastructure and homes. | Coordinating and managing the long-term recovery efforts to help affected communities rebuild and recover. Supporting the implementation of disaster risk reduction measures to reduce the risk of future disasters. Conducting assessments and evaluations to monitor the progress of recovery efforts and identify areas for improvement. |

| Providing financial assistance and support to those affected by the disaster to help them rebuild their lives. | ||||

| Department of Treasury Operations | DTO | Facilitating the fund allocations for post-disaster management programmes. | ||

| National Planning Department | NPD | Coordinating national-level policies and facilitating planning. | ||

| Ministry of Urban Development and Housing | MUDH | Providing temporary housing for displaced persons. | Supporting the development of long-term recovery via new infrastructure and housing projects. | |

| Supporting the rehabilitation of damaged infrastructure including roads, bridges, and buildings. | ||||

| Ministry of Education | MOE | Providing immediate assistance (shelters) to affected schools in collaboration with other relevant stakeholders. | Ensuring uninterrupted services in education. | Working closely with other relevant stakeholders in building capacities in schools and also ensuring that schools are disaster resilient. |

| Ministry of Health | MOH | Coordinating and managing the immediate response to the disaster in the health sector, including the provision of emergency medical care and treatment to affected people. Establishing emergency medical facilities and field hospitals in affected areas. Providing mental health support and psychosocial services to affected populations. | Supporting the rehabilitation of damaged health facilities and medical equipment. Providing financial and technical assistance to help affected health facilities rebuild and recover. | Supporting the long-term recovery of the health sector in affected areas, including the development of new health facilities and medical services. Developing policies and strategies to improve the resilience of the health sector to future disasters. |

| Ministry of Agriculture | MOA | Assessing the damage that has occurred to farms/farmers | Support in rebuilding livelihoods within the agriculture field. | |

| Department of Irrigation | DOI | Coordinating and managing the immediate response to floods and other water-related disasters, including the management of water resources to minimise the impact on agricultural communities. Providing technical assistance to other government agencies, non-governmental organisations, and international partners involved in disaster response. | Supporting the rehabilitation of damaged irrigation infrastructure. | Supporting the long-term recovery of the irrigation sector in affected areas, including the development of structural measures and the promotion of sustainable water management practices. Developing policies and strategies to improve the resilience of the irrigation sector to future disasters. |

| Providing financial and technical assistance to help affected communities rebuild and recover. | ||||

| Road Development Authority | RDA | Coordinating and managing the immediate response to disasters, including the assessment and repair of damaged roads, bridges, and other transportation infrastructure. | Supporting the rehabilitation of damaged transportation infrastructure, including the repair of roads, bridges, and other transportation systems. | Supporting the long-term recovery of the transportation sector in affected areas, including the development of new transportation projects and the promotion of sustainable transportation practices. |

| National Water Supply and Drainage Board | NWS&DB | Supplying purified drinking water to relief centres and affected areas. | Supporting the long-term recovery of the water supply and drainage sector in affected areas, including the promotion of sustainable water management practices. | |

| Coordinating and managing the immediate response to disasters, including the assessment and repair of damaged water supplies and drainage systems. | ||||

| Ceylon Electricity Board and Lanka Electricity Company | CEB & LECO | Providing uninterrupted power supply to relief centres and affected areas. | Supporting the long-term recovery of the electricity supply of the rebuilt and rehabilitated houses in affected areas. | |

| Coordinating and managing the immediate response to disasters, including the assessment and repair of damaged electricity supply systems. | ||||

| Department of Social Services | DSSs | Coordinating and managing the immediate response to disasters, including the provision of emergency shelter, food, and other basic needs for affected individuals and communities. | Providing assistance to manage relief centres. Providing assistive devices and equipment and ensuring that relief supplies are accessible to persons with disabilities. | Supporting the long-term recovery of affected communities, including the development of policies and programmes to improve the resilience of vulnerable populations to future disasters. |

| Providing psychosocial support to affected individuals and communities, including counselling and other mental health services. | ||||

| Women-related government organisation | SLWB | Ensuring that the specific needs of women and girls are addressed in disaster response efforts. Providing support for women and children who may have been displaced or separated from their families during the disaster. Working to ensure that basic needs, including food, water, health, and shelter, are met. | Supporting the recovery of women and girls who may have been affected by the disaster. Addressing the specific needs of women and girls in the rebuilding of homes and communities. | Advocating for their rights and needs in the development of government policies and programmes. Ensuring that women’s voices are heard and their concerns addressed throughout the recovery process. |

| Providing psychosocial support for survivors, including counselling services. | ||||

| Supporting livelihoods programmes and capacity building to help women and girls rebuild their lives and regain economic stability. | ||||

| Addressing gender-based violence and other issues that may arise in the post-disaster context. | ||||

| National Child Protection Authority and Children’s Secretariat | NCPACS | Providing immediate assistance to children affected by the disaster, such as medical care, shelter, and food. Ensuring the protection and safety of children who have been separated from their families or are unaccompanied. | Supporting the reintegration of children who have been separated from their families or are unaccompanied | Monitoring the ongoing needs and welfare of children in the aftermath of the disaster |

| Advocating for the implementation of child-friendly policies and practices in the rebuilding process. | ||||

| Supporting the provision of education and vocational training for children who have been displaced or otherwise affected by the disaster. | ||||

| Providing psychosocial support and counselling to children who have experienced trauma as a result of the disaster. | ||||

| Sri Lanka Police | SLP | Providing immediate assistance in rescue and evacuation efforts during the disaster. | Assisting in the establishment of temporary shelters and camps for displaced persons. Providing assistance for affected communities in the restoration of essential services, such as electricity and water supply. Providing assistance in removing debris and clearing roads. | Assisting in the rehabilitation and resettlement of affected communities. |

| Assisting in providing emergency medical services and transportation. | ||||

| Coordinating with other agencies to ensure the safety and security of affected communities. | ||||

| Tri Forces | TFs | Conducting search and rescue operations to save lives and provide immediate assistance to affected communities. Providing transportation and logistical support for relief operations. Distributing food, water, and other essential supplies to affected communities. Providing medical assistance to the injured. | Providing security and safety to affected communities. Providing assistance in setting up temporary shelters for the displaced. Assisting in the restoration of essential services, such as electricity and water supply. Providing assistance in clearing debris and repairing damaged infrastructure. | Providing rebuilding assistance, engaging with housing and infrastructure reconstruction. |

| Non-Governmental Organisations and International Non-Governmental Organisations | NGOs & INGOs | Providing emergency relief materials, such as food, water, and medical supplies to the affected communities. | Providing assistance in setting up temporary housing and shelter for displaced persons. Assisting in the restoration of essential services, such as water, electricity, and sanitation facilities. | Developing and incorporating guidelines to strengthen inclusive rebuilding programmes. Ensuring accountability to vulnerable communities receiving humanitarian and development aid. Carrying out rebuilding projects. Providing medical treatment and counselling to persons who have suffered from traumatic experiences. Carrying out awareness programmes. |

| Providing inclusive livelihood support to help affected families rebuild their lives. | ||||

| Providing financial assistance. | ||||

| Donor Community (National and International) | DC | Providing financial assistance. | ||

| United Nations Agencies | UNAs | Providing emergency relief materials, such as food, water, and medical supplies to affected communities. | Providing assistance in setting up temporary housing and shelter for displaced persons. Assisting in the restoration of essential services, such as water, electricity, and sanitation facilities. | Developing and incorporating guidelines to strengthen inclusive rebuilding programmes. Ensuring accountability to vulnerable communities receiving humanitarian and development aid. Carrying out rebuilding projects. Providing medical treatment and counselling to persons who have suffered from traumatic experiences. Carrying out awareness programmes. |

| Providing inclusive livelihood support to help affected families rebuild their lives. | ||||

| Providing financial assistance. | ||||

| Providing technical assistance | ||||

| National Secretariat for Elders | NSE | Providing support and assistance to elderly people. | ||

| District Secretariat Office | DSO | Coordinating with relevant government agencies, non-governmental organisations, and other stakeholders to ensure that emergency relief and assistance is provided for the affected communities in a timely and efficient manner. Establishing temporary shelters and distribution centres for relief supplies. Collecting and disseminating information on the extent of damage and the needs of the affected communities to relevant stakeholders. | Assessing the damage caused by the disaster and developing a rehabilitation plan in collaboration with other relevant agencies and stakeholders. Coordinating the implementation of the rehabilitation plan and ensuring that the needs of the affected communities are met. Providing support and assistance to vulnerable groups, such as women, the elderly, the disabled, and children, to facilitate their rehabilitation and reintegration into their communities. | Monitoring and guiding the divisional level to carry out all the activities at the post-disaster stage relating to rebuilding the community. Facilitating the divisional secretariat office for the rebuilding processes. |

| Preparing daily situational reports and sending them to the DMC and NDRSC. | ||||

| Provincial Council | PC | Supporting the DSO in carrying out post-disaster management activities | ||

| Divisional Secretariat Office | DivSO | Information dissemination and technical assistance for the community. Responsible for carrying out all the post-disaster management activities. Preparing daily situation reports and sending them to the district secretariat office. | ||

| Local Government | LG | Supporting DivSO in carrying out post-disaster management activities | ||

| Grama Niladari | GN | Facilitating the entire post-disaster process at the community level and ensuring that affected individuals and households receive the support they need to recover from the disaster. | ||

| Community based Organisations | CBOs | Assisting the affected communities and GNs voluntarily to recover from the disaster. | ||

| Marginalised Community | MC | Communicating needs/requirements to the relevant stakeholders involved in executing post-disaster management programmes. | ||

| Media | M | A source of social capital to develop social constructions and social transformation. | ||

| Research Institutions (including universities) | RIs | Providing valuable data, analysis, and recommendations to inform decision making in each phase of disaster management. | ||

| National Enterprises Development Authority | NEDA | Encouraging, promoting, and facilitating small and medium enterprise development. | ||

| Land Reform Commission | LRC | Releasing statutory determination and legal obligations of lands after disasters. | ||

| Sri Lanka Transportation Board | SLTB | Transporting relief supplies, such as food, water, and medical supplies, to affected areas. | ||

| Providing assistance in evacuating people from affected areas to safer locations. | ||||

| Ensuring the smooth functioning of transportation services in a post-disaster context. | ||||

| Mahaweli Authority Sri Lanka | MASL | Coordinating and managing the immediate response to floods and other water-related disasters, including the management of water resources to minimise the impact on agricultural communities. Providing technical assistance to other government agencies, non-governmental organisations, and international partners involved in disaster response. | Supporting the rehabilitation of damaged irrigation infrastructure. | Supporting the long-term recovery of the irrigation sector in affected areas, including the development of structural measures and the promotion of sustainable water management practices. Developing policies and strategies to improve the resilience of the irrigation sector to future disasters. |

| National Insurance Trust Fund | NITF | Providing low-interest loans, grants, or other forms of financial assistance to help people rebuild their homes or businesses. | ||

| Samurdhi Department | SD | Providing financial assistance to the affected community. | ||

References

- Mitra, A.; Shaw, R. Systemic Risk from a Disaster Management Perspective: A Review of Current Research. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 140, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Wan, C.; Ye, Q.; Yan, J.; Li, W. Disaster Risk Reduction, Climate Change Adaptation and Their Linkages with Sustainable Development over the Past 30 Years: A Review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2023, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnayake, A.; Jayasinghe, L.; Nauki, T.; Weerathunga, S. Disaster Management in Sri Lanka: A Case Study of Administrative Failures; Verité Research: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery Joint Communique on Inclusion for Resilient Recovery. Available online: https://www.gfdrr.org/en/WRC4/communique (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- CORDAID. Step-by-Step Guide to Inclusive Resilience; CORDAID: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/71675_716542020marchpfrinclusiontoolkit.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Steele, P.; Knight-John, M.; Rajapakse, A.; Wickramasinghe, K.S.K. Disaster Management Policy and Practice: Lessons for Government, Civil Society, and the Private Sector in Sri Lanka; Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2007; ISBN 9789558708507. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma. Disaster Risk Management: Inclusive; INCRICD South Asia: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2014; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/actionaid_inclusion_paper_final_170614_low.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Wickramasinghe, K. Role of Social Protection in Disaster Management in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovita, H.D. Cross-Sector Collaboration in Region X Philippines’ Disaster Management; Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta: Kasihan, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]