3.1. Economic Modeling

The number of independent variables used varied by mode of access (i.e., charter boat and private boat). Differences in variables relevant to each model were noted and differences in levels for different attributes (i.e., price) were detailed. Socioeconomic variables such as income, age, race/ethnicity or gender were not included in the estimated models. The choice attributes were described first, followed by additional variables tested in the logistic regressions.

For the private boat mode, bag limit/size limit did not yield usable results since in the private boat model anglers had higher value for the existing regulation, which is not sustainable. This will be discussed in the model results section. MRIP data from 2004 to 2016 were used to determine the success rates; i.e., the percentage of anglers that achieved the bag limit/size limit. The MRIP data were weighted by geographic area (e.g., northwest, NW, and southwest, SW) since the existing bag limits were different for each zone. The success rates by mode and geographical zone were variable across years. For 2004–2016, the average success rates for the charter boat—full-day were 18.21% in the NW and 9.66% in the SW, 5.83% in the NW and 1.4% in the SW for charter boat—half-day, and 2.3% in the NW and 1.42% for the SW for private/rental boats. For 2012–2016 (a five-year annual average often recommended for use in policy/management analysis of regulations), the success rates were 14.2% in the NW and 2.58% in the SW for charter—full-day, 5.78% in the NW and 1.33% in the SW for charter—half-day, and 1.48% in the NW and 0.77% in the SW for private/rental boats. Private/rental boat anglers generally have the lowest success rate and their success rates significantly declined from 2004 to 2016 (

Table 3).

It is possible that for private/rental boat anglers, the success rate was so low that the perception of achieving the higher bag limit/size limit combination would be low and the movement to the new regulation would be undervalued. Therefore, a variable was created to account for the low probability of achieving the bag limit/size limit. A dummy variable to differentiate those who targeted spotted seatrout was also created where 1 = targeted spotted seatrout and 0 = did not target spotted seatrout.

Since the researchers were unable to link the MRIP intercept survey where the catch was recorded to the data collected in this effort, the success in achieving the bag limit/size limit combination of each sampled angler was not available. To construct a variable on the probability of achieving the bag limit/size limit combination, the MRIP intercept survey data from 2004 to 2016 were used to run a logistic regression equation to predict the probability of achieving the bag limit/size limit combination for private/rental boat anglers.

Model for predicting success rate by private/rental boat anglers

where P = predicted probability of a private/rental boat angler achieving the bag limit/size limit combination in the current regulation.

Local_res = region of residence 1 = west coast of Florida resident, 2 = east coast of Florida resident and 3 = non-resident of Florida. A dummy variable was then constructed, where 1 = west coast of Florida resident and 0 = not a resident of west coast of Florida.

Year = year of survey.

It was hypothesized that the predicted probabilities would vary by place of residence, fishing intensity, and year. Place of residence was a proxy for knowledge assuming that those who lived on the west coast of Florida would have the most knowledge of the area, holding other factors constant. The intensity of fishing served as a proxy for experience as measured by the number of annual days spent saltwater fishing in Florida. Finally, the year was included to adjust for stock effects due to environmental or other factors. Equations were run with unweighted and weighted data using PROC Logistic in SAS Version 9.4 and NLOGIT Version 5 for checking SAS results and obtaining additional statistics on model performance such as pseudo R-square.

The results for the model found similar results for weighted and unweighted data (

Table 4). Those with more experience (fishdays_12_mo) had a higher probability of achieving the bag limit/size limit combination. An unexpected result was obtained for those who were residents of the west coast of Florida. Researchers hypothesized that west coast residents would have more knowledge of the west coast fishery and therefore a higher probability of catching the bag limit, but results found this not to be true with local residents having a lower probability of achieving the bag limit/size limit. Year gave the expected negative sign as the probability of success declined over time.

As will be shown below in the private boat analysis of economic value, the predicted probabilities for private/rental boats were used in the valuation analysis. To predict the probabilities of achieving the bag limit/size limit for those who accessed the fishery from private/rental boats, a separate model was estimated using geographic weights.

Weighted private/rental boat success rate equation

where LN (

p/1 −

p) is the natural logarithm of the odds ratio.

Solving the equation for P:

P = 1/(1 + ex), where x = log of the odds ratio.

All the explanatory variables were statistically significant for the weighted equation. The percentage of correct predictions was 65%. Pseudo R-square was 0.03, which is relatively low for time series data.

3.2. Protest Bids

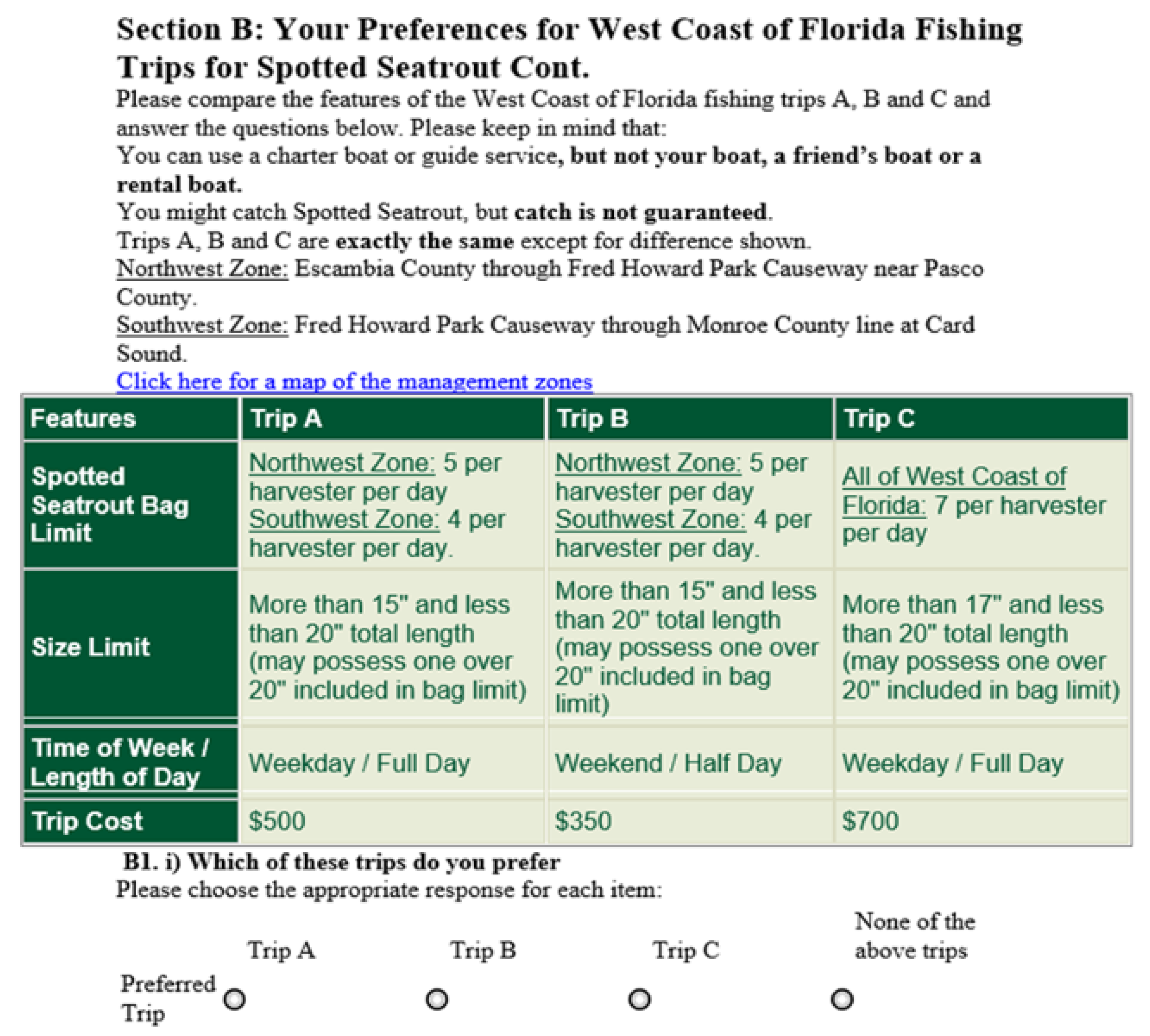

A protest bid analysis was also conducted for the charter and private rental boat samples. The first step was to identify how many respondents answered ‘none’ to which of the trips they preferred. In the charter sample, 12 respondents answered none to all the choice questions, and 124 respondents answered none to all the choice questions they responded to in the private/rental sample.

Secondly, those who had selected none to all the chosen questions they answered may have had either a true selection in that they preferred none of the options presented or they may have been protesting the questions. To identify true protest bids, several follow-up questions were asked about why they did not choose a trip. The reasons included:

Costs too high;

Do not think fishery managers will use results from this study;

Do not believe the bag limit/size limit combinations are sustainable for spotted seatrout;

Against all government regulations of the fisheries;

Other.

If a respondent selected 2, 3, or 4 from the above list, then the respondent was identified as a protestor. Based upon this analysis, there were no protestors in the charter sample and 11 protesters in the private/rental boat sample. (Many of the ‘other’ responses included people giving alternative options they would have preferred to have seen or indicated that they engaged in catch and release activities. Neither of these would qualify as a protestor).

3.3. Charter Boat Analysis

For this analysis, two models were run, the conditional logit model and random parameters model using STATA SE Version 14. The random parameters model was estimated to account for the Hausman–McFadden Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) to test for the assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives [

13]. However, when the conditional logit does not pass the IIA assumption, it should not be of much concern, as the alternatives “can plausibly be assumed to be distinct and weighted independently in the eyes of each decision maker” [

14].

As the survey was developed to present respondents with distinct scenarios to choose from, it is reasonable to accept the conditional logit specification. When considering other model specification, one of the benefits of the random parameters model is it allows for heterogeneity and addresses the independence of identically distributed random variables violation of constant variance for the observed portion of the variance [

9]. For the random parameters model, the normal error structure was assumed. Price was a fixed factor while all other variables were random. Only three variables for the charter boat model (baglim, weekday, and full-day) that were treated as random had a significant coefficient on their standard deviations (SDs). This means that for these variables there was significant heterogeneity among charter boat anglers for these attributes.

Applied work like the analysis used here for the conditional logit model can be found in several previous papers [

15,

16,

17] and for the RP model [

16,

17,

18]. The math behind each of the model specifications may be found in Louviere, Hensher, and Swait (2000) [

9]. STATA Version 14 was used to estimate all three models [

19]. However, the basic premise behind the models is below.

where

αji is a fixed or random alternative-specific constant associated with j = 1, … J alternatives and i = 1, …, I individuals and αj = 0;

φj is a vector of non-random parameters;

βji is a parameter vector that is randomly distributed across individuals; µi is a component of the βji vector (see below);

zi is a vector of individual-specific characteristics (e.g., personal income);

fji is a vector of individual-specific and alterative specific attributes;

xji is a vector of individual-specific and alterative specific attributes;

µi is the individual-specific random disturbance of unobserved heterogeneity.

A subset or all of α

ji alternative-specific constants and the parameters in the

βji vector can be randomly distributed across individuals, such that for each random parameter, a new parameter, call it

ρki, can be defined as a function of characteristics of individuals and other attributes which are choice invariant ([

9], p. 199).

In both models, price was negative and significant. Additionally, in both models all of the bag limit/size, weekday, and full-day variables were positive. However, only the full-day variable was statistically significant in both models. The bag limit/size and weekday were only significant in the conditional logit model (

Table 5). The random parameters model for charter boat anglers did not produce a statistically significant coefficient on the bag limit/size limit. Two explanations are plausible for the random parameters results: first, the endowment effect, and second, the low success rate in achieving the bag limits/size limit combinations on Florida’s west coast for spotted seatrout, both of which are discussed in further detail in the private/rental boat section.

The positive relationship for the bag limit/size limit means that respondents were willing to pay more for the new regulation; a bag limit of 7 fish per day between 17 and 20 inches long. Respondents were also willing to pay more for a weekday charter trip as opposed to a weekend charter trip and they were also willing to pay more for a full-day trip versus a half-day trip. In the conditional logit model, where all variable estimates were significant, the most influential variable to affect their decision to choose an option was whether the trip was a weekday, followed by whether the trip was a full or half day.

Another possible behavioral response to a change in the bag limit/size limit combinations is a change in the number of days fishing. The survey choice questions were followed by a question asking the respondent for the choice they made, would they have changed the number of days they fished during the past 12 months on Florida’s west coast. Theoretically, it is possible that willingness to pay per day could increase but days of fishing (effort) could decline, remain the same or increase. The analysis on change of days was conducted using a negative binomial count data model, but the model produced no statistically significant results; consequently, there would be no change in days of fishing in response to the new bag limit/size limit combination.

3.4. Private Boat Analysis

The initial models estimated (conditional logit and random parameters) for private/rental boat anglers produced a negative coefficient on the bag limit/size limit, which suggests that private/rental boat anglers value the existing bag limit/size limit higher than the proposed alternative. This suggests that a more restrictive policy would decrease the user’s utility, resulting in an economic loss to anglers. One explanation for this result is there may be an ‘endowment effect’ caused by an individual’s attachment to a good [

20,

21,

22]. Experimental work by these authors and others (e.g., List, 2003; 2004) using everyday goods such as coffee mugs, chocolate bars, and sports cards do indeed find evidence of an endowment effect. Milon (2005) found this for reducing the bag limits for spiny lobster in the Florida Keys [

23].

A second possible explanation is the low success rate in achieving the bag limits/size limit combinations on Florida’s west coast for spotted seatrout. One hypothesis is that accounting for this low probability of achieving the current bag limit/size limit would result in a positive increase in the willingness to pay for the new sustainable levels of the bag limit/size limit. This hypothesis was tested by interacting the predicted probabilities of achieving the bag limit/size limit combination and with a dummy variable for whether private/rental boat anglers targeted spotted seatrout. The results supported this hypothesis (

Table 6). Given the random parameters model failed to yield a statistically significant coefficient on the price variable, the conditional logit model was used to estimate marginal willingness to pay.

As with the charter boat mode, the researchers also tested whether there would be a change in the number of fishing days for the choices made and found no statistically significant results. Therefore, there were no expected changes in days of fishing from the change in bag limits/size limits.

3.5. Marginal Willingness to Pay

For the estimated models, the marginal willingness to pay (MWTP) can be calculated for each attribute to assess relative importance. MWTP here is the change in value at movement from the ‘zero’ level of the condition to the ‘one’ level of the condition. The formula for MWTP is the attribute’s coefficient divided by the negative of the price coefficient [

9,

24]. The results for the conditional logit model are in

Table 7 below.

In this research, willingness to pay is a useful metric that quantifies the change in utility for a change in the quality of an attribute. This estimate can be used to both quantify the change in benefit and the change in net benefits when the cost of a proposed management action is known. Further, understanding the value that various user groups have for the same resource helps to inform discussions and to understand how benefits (or costs if activity is restricted) accrue to various users as the result of a policy change or management action.

Charter boat anglers were willing to pay about USD 61 using the conditional logit for the new regulation. Charter boat anglers also placed a premium on fishing during the weekday versus the weekend. Based upon the conditional logit estimates, they were willing to pay about USD 120 more for a weekday versus the weekend and USD 114 more for a full-day trip versus a half-day trip.

Private/rental boat anglers were willing to pay about USD 81 using the conditional logit for the new regulation. Private/rental boat anglers were willing to pay less for weekdays versus weekend days (

Table 8). These results contrast with those for charter boat anglers. The results might be explained by the opportunity cost of time for private/rental boat anglers. Fishing on a weekday may require taking a day off from work and either giving up pay or using a vacation day.

For charter boat anglers, the estimated change in value was USD 60.72 per trip. Since the variable used was the price of chartering a boat for the day, the estimate must be converted to a value per person per day to aggregate this to a total annual value. The average party size was three for charter boats, so the estimated marginal value was USD 20.24 per person per day. For private/rental boat anglers, the estimated value per trip for the new bag limit/size limit was USD 81.34 per trip. The average party size for private/rental boats was 2.5, so that yields a value per person per day of USD 32.54.

To estimate the annual increase in value, a five-year average (2012–2016) of days of fishing by mode of access for those who caught or targeted spotted seatrout on Florida’s west coast (MRIP 2012–2016) was used and we multiplied the average annual days by the marginal values. Charter boat anglers recorded 167,240 person-days of fishing, while private boat anglers spent 4,440,919 days fishing for spotted seatrout. This translates into a change in total value, for the change in bag limit/size limits from the old to the new regulation, of almost USD 148 million. Charter boat anglers accounted for 3.63% of fishing days and 2.29% of the change in annual value, while private boat anglers accounted for 96.37% of fishing days and 97.71% of the change in annual value (

Table 9).

The estimated values for changes in the bag limit/size limit combinations for charter boat anglers relative to private/rental boat anglers would seem counter to the usual relationships since most studies find the value of charter boat trips are more valuable than private/rental boat trips. However, the total value of the trip was not being estimated. Instead, it was the change in value for a change in the bag limit/size limit that was estimated. Charter boat anglers targeting or catching spotted seatrout on Florida’s west coast have been much more successful in achieving the bag limit/size limit than private/rental boat anglers. Therefore, private/rental boat anglers would be experiencing a much larger change with the new bag limit/size limit than charter boat anglers would.

A review of the literature reveals no one else has modeled the biological constraint on the bag limit/size limit combination and treated it as a composite good. The literature available estimates the marginal value of bag limits and size limits as if they were independent attributes [

8,

25]. For species in which the biological model determines that bag limits and size limits jointly determine stock levels that are sustainable, economic valuation must treat the bag limit/size limit as a composite good in which the separate utilities/values cannot be estimated for each component.