A Cyber-Physical All-Hazard Risk Management Approach: The Case of the Wastewater Treatment Plant of Copenhagen

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- Attacks against infrastructure (e.g., Denial of Service (DoS) attack).

- -

- Attacks on IoT sensors (e.g., sensors being impersonated to send misleading values to the backend server, or credentials of sensors being used to gain access to a private network, thus extending the attack surface).

- -

- Attacks on ML/AI (e.g., specially crafted input to mislead the underlaying algorithm). These attacks can be chained after the attacks on IoT sensors to control the input.

- -

- Attacks on applications (e.g., web, mobile, etc.).

- -

- Human errors/failures (e.g., a user is given more access to an application than required, exposing sensitive data).

- -

- Social engineering (e.g., attackers may trick operators into performing harmful actions).

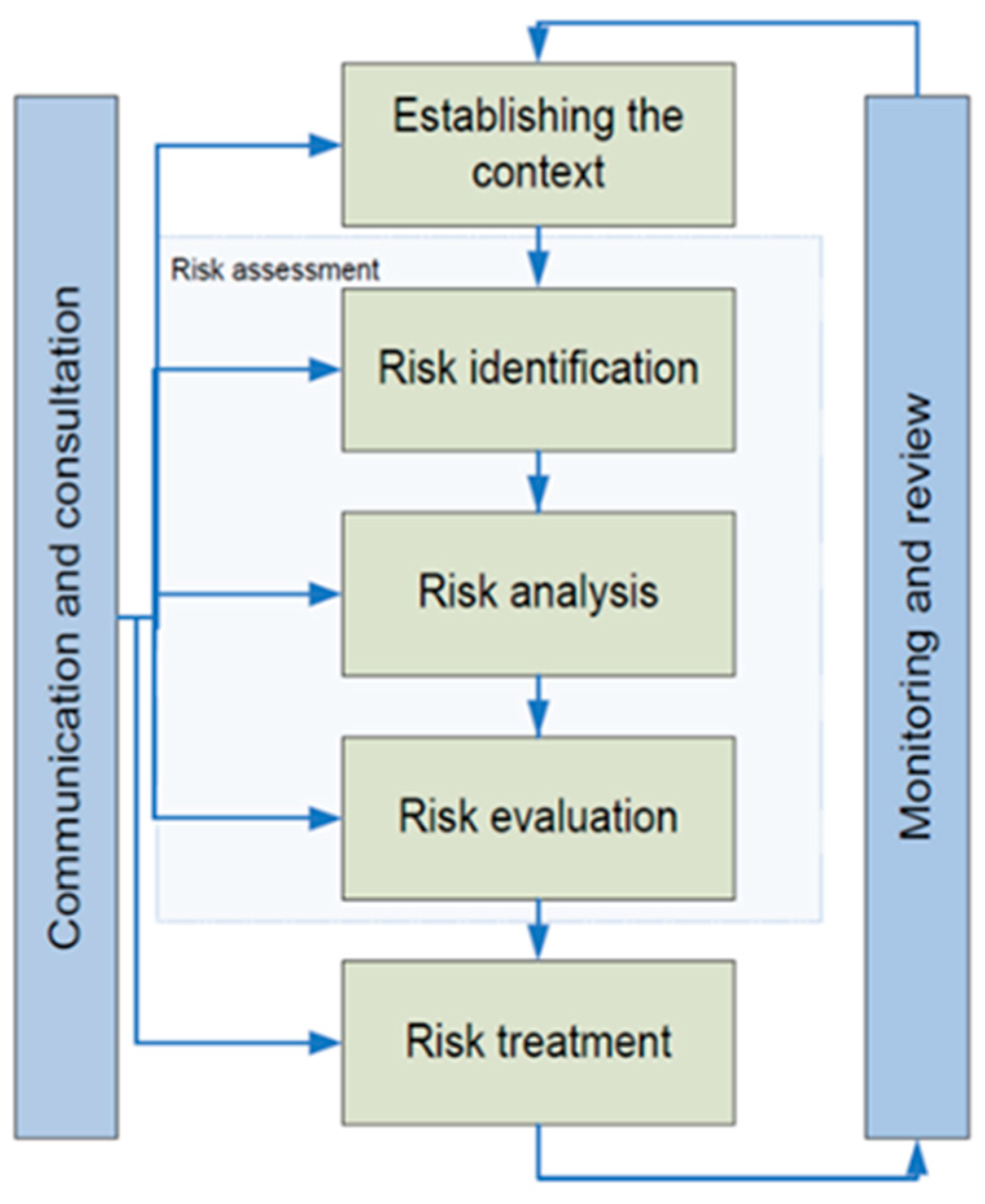

2. Materials and Methods

- Defining the context.

- Risk identification.

- Risk analysis.

- Risk evaluation.

- Risk treatment.

2.1. Defining the Context

2.1.1. Defining the Scope and Criteria within ISO Framework

- -

- Very unlikely (VU): less than once per 100 year (p < 0.01).

- -

- Remote (R): once per 10–100 year (0.01 ≤ p < 0.1).

- -

- Occasional (O): once per 1–10 year (0.1 ≤ p < 1).

- -

- Probable (P): once to 12 times a year (1 ≤ p < 12).

- -

- Frequent (F): more than once a month (p > 12).

- -

- Very low (VL): KPI < 1.

- -

- Low (L): 1 ≤ KPI < 3.

- -

- Medium (M): 3 ≤ KPI < 10.

- -

- High (H): 10 ≤ KPI < 30.

- -

- Very high (VH): KPI ≥ 30.

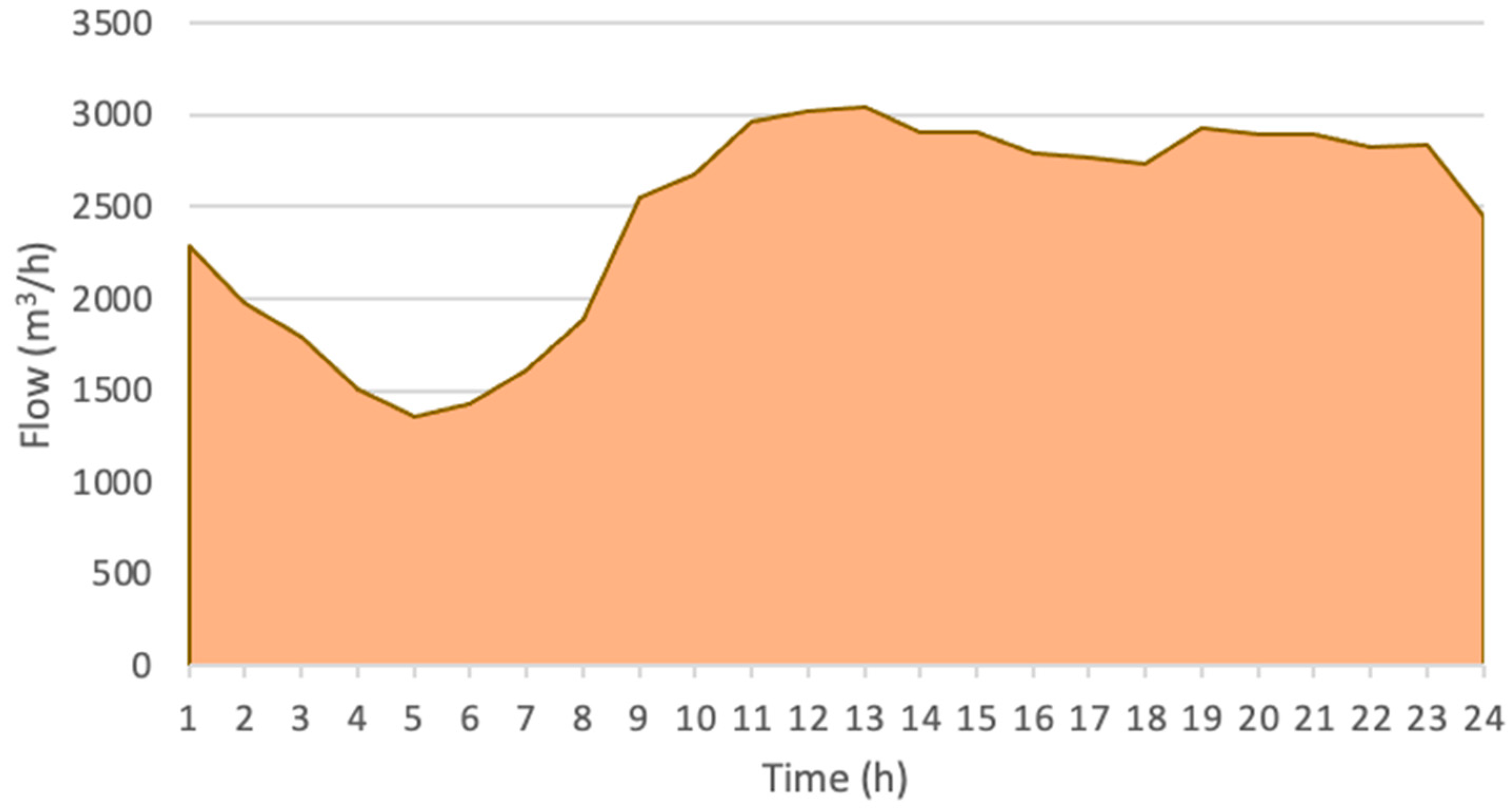

2.1.2. The Context of the Considered Case Study

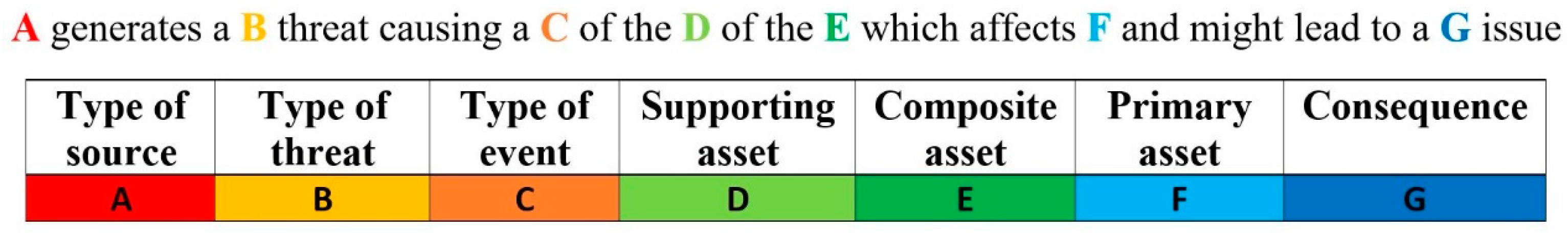

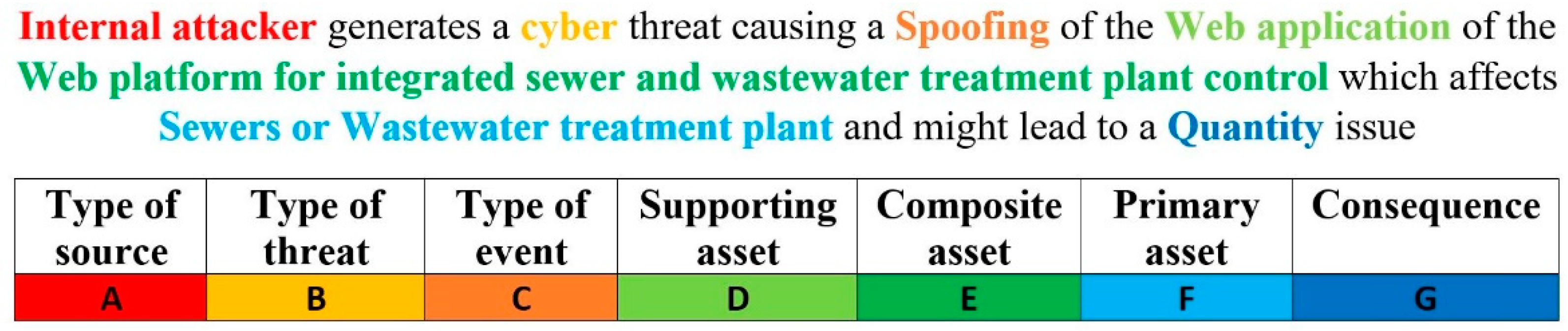

2.2. Risk Identification

2.2.1. Risk Identification within ISO Framework

2.2.2. Adopted Approach for the Identification of the Considered Risk

2.3. Risk Analysis

2.3.1. Risk Analysis within the ISO Framework

2.3.2. Adopted Approach to Estimate Consequences for the Identified Risk

2.3.3. Adopted Approach to Estimate Probabilities for the Identified Risk

- To find the frequency and the probability of success of an attack attempt (sometimes referred to as the likelihood of threat happening), a set of questions is provided.

- For each question, there is a predefined list of answers, where each answer is associated with a score.

- The scores are aggregated according to the formulas described in the InfraRisk-CP manual [34] to provide a total score for the frequency of an attempt and a total score for the probability of success.

- To transform the score to a frequency or probability number, a low value fL or pL and a high value fH or pH are defined. fL represents the frequency of an attack attempt if all scores for the attack attempt questions have the lowest possible values, and fH represents the frequency of an attack attempt if all scores have the highest possible values. pL represents the probability of a successful attack attempt if all scores have the lowest possible values, and pH represents the probability if all scores have the highest possible values.

- To find the frequency of a successful attack attempt, the frequency of an attack attempt is multiplied with the probability of success.

2.4. Risk Evaluation

2.4.1. Risk Evaluation within ISO Framework

- -

- do nothing further;

- -

- consider risk treatment options;

- -

- undertake further analysis to better understand the risk;

- -

- maintain existing controls;

- -

- reconsider objectives.

2.4.2. Adopted Approach to Evaluate the Identified Risk

2.5. Risk Treatment

2.5.1. Adopted Approach to Evaluate the Identified Risk

- -

- formulating and selecting risk treatment options;

- -

- planning and implementing risk treatment;

- -

- assessing the effectiveness of that treatment;

- -

- deciding whether the remaining risk is acceptable;

- -

- if not acceptable, taking further treatment.

2.5.2. Adopted Approach to Treat the Identified Risk

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Defining the Context

The Risk Criteria for the Considered Case Study

3.2. Risk Identification

Identified Risk for the Case Study

3.3. Risk Analysis

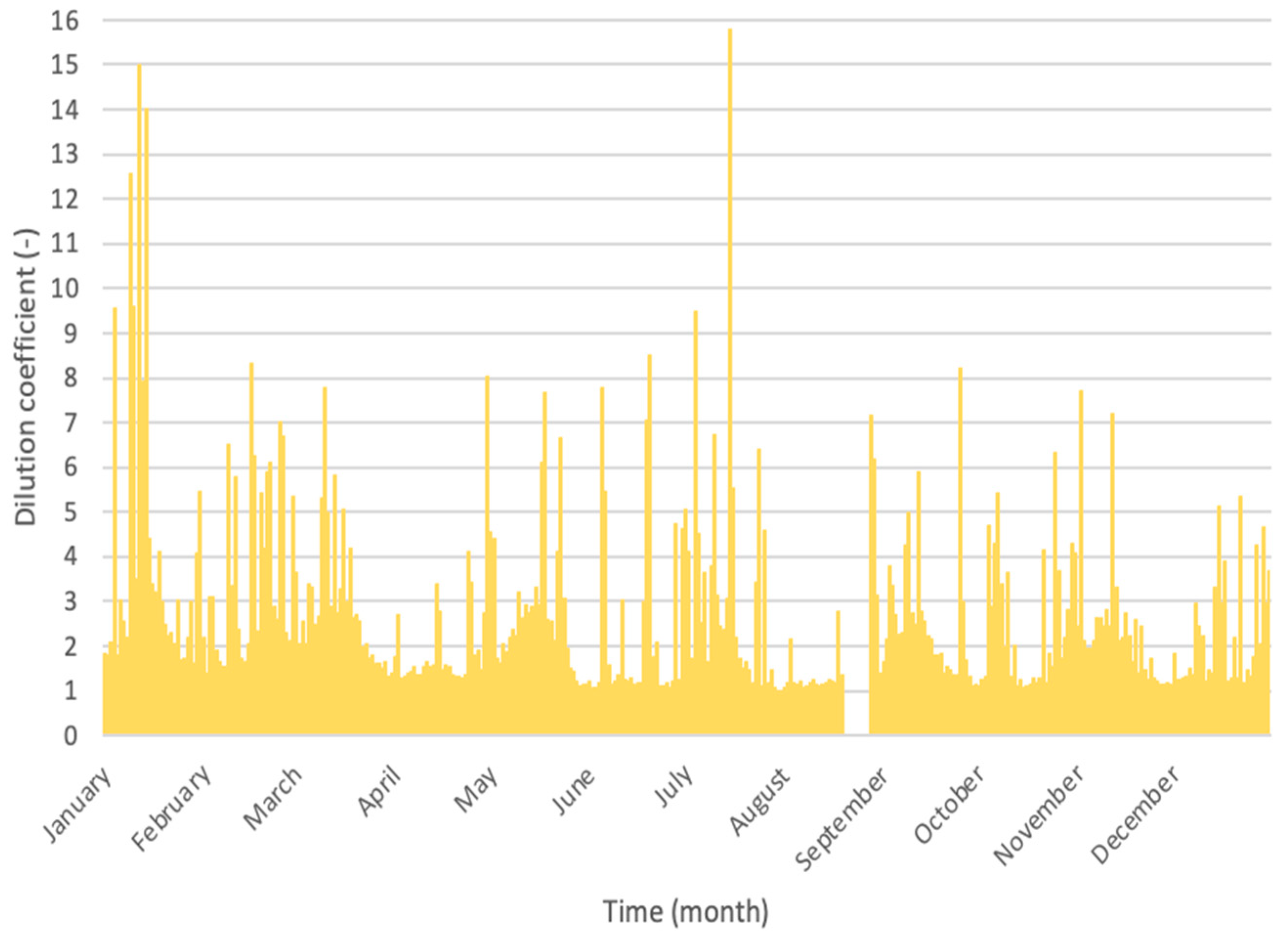

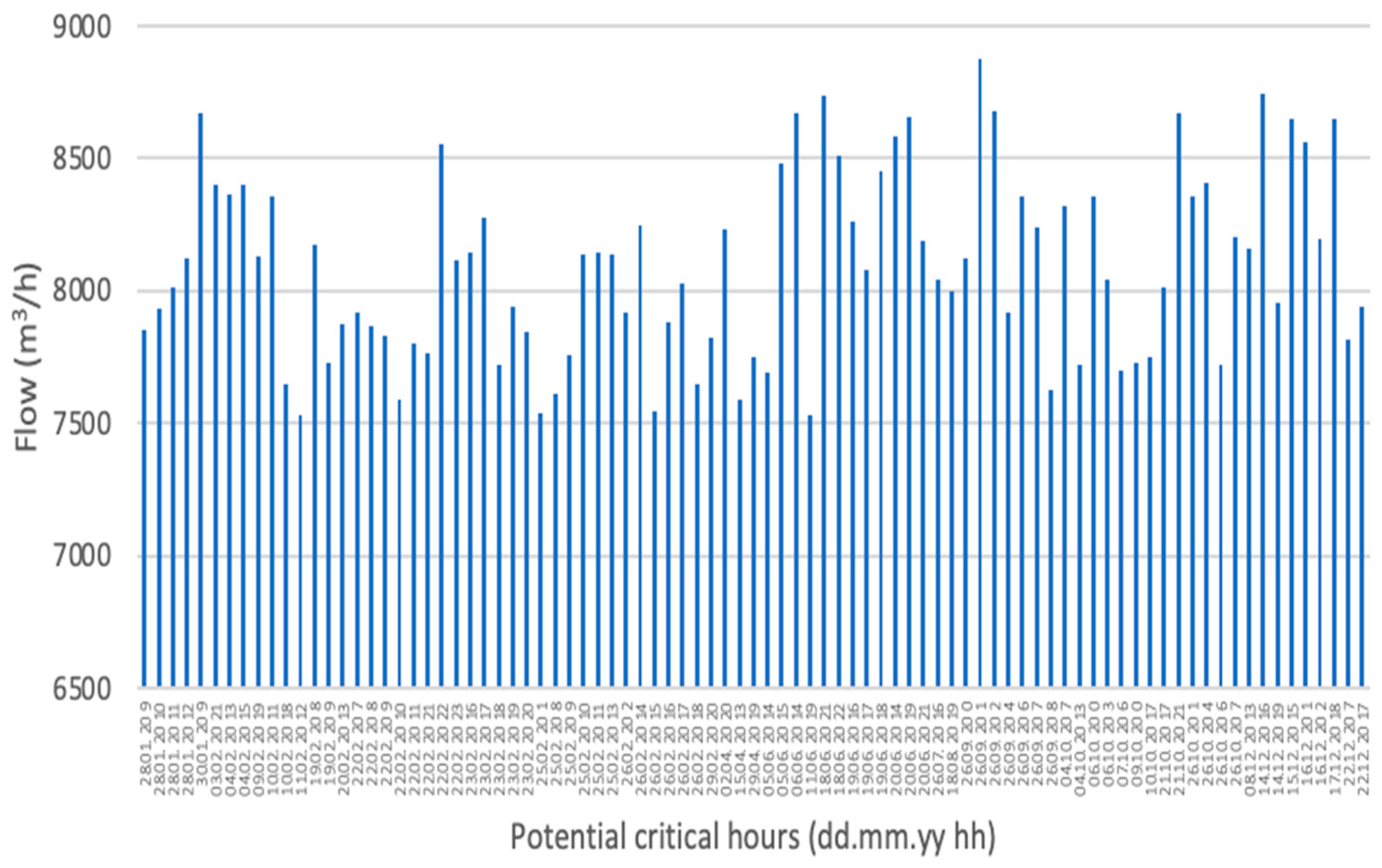

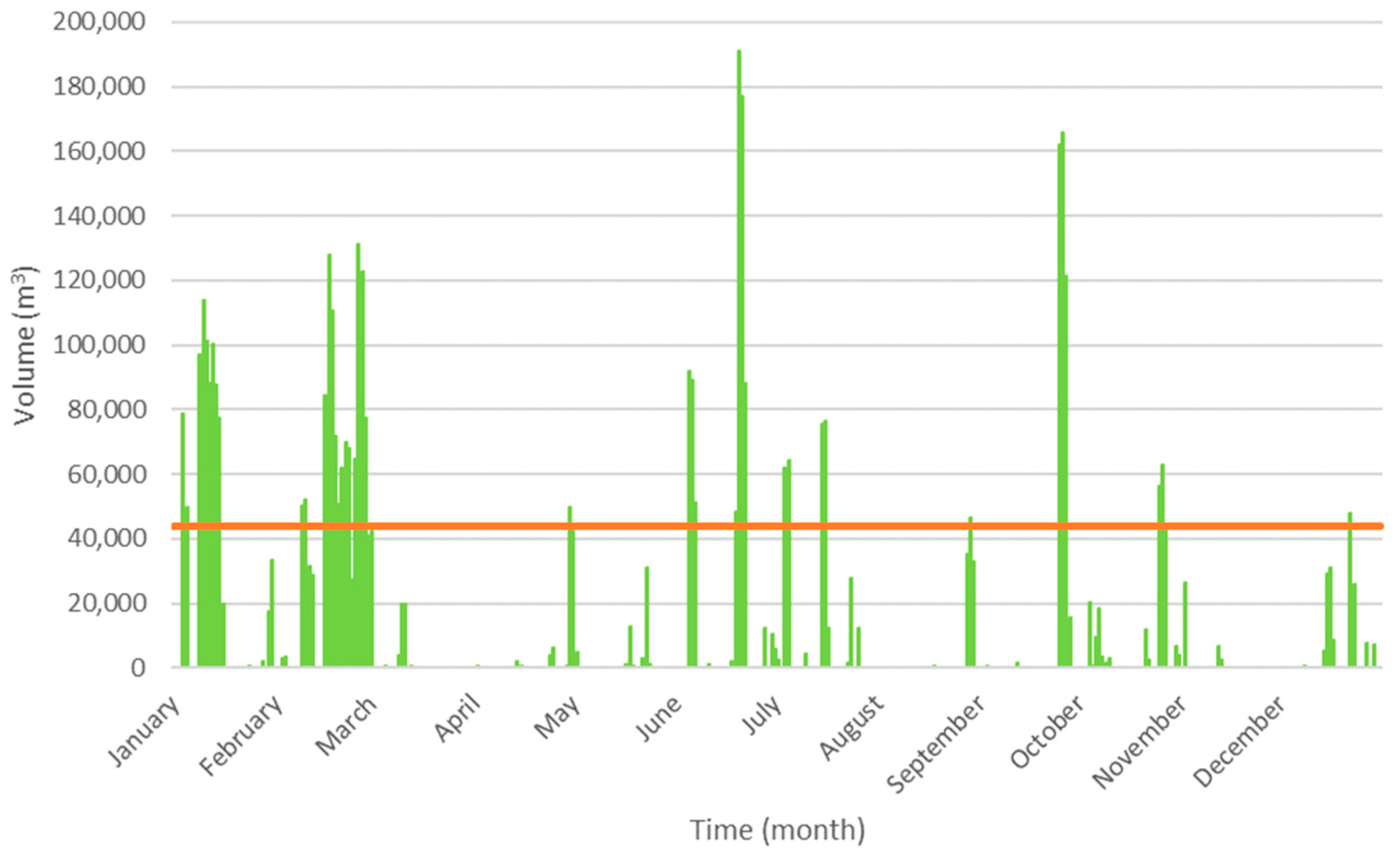

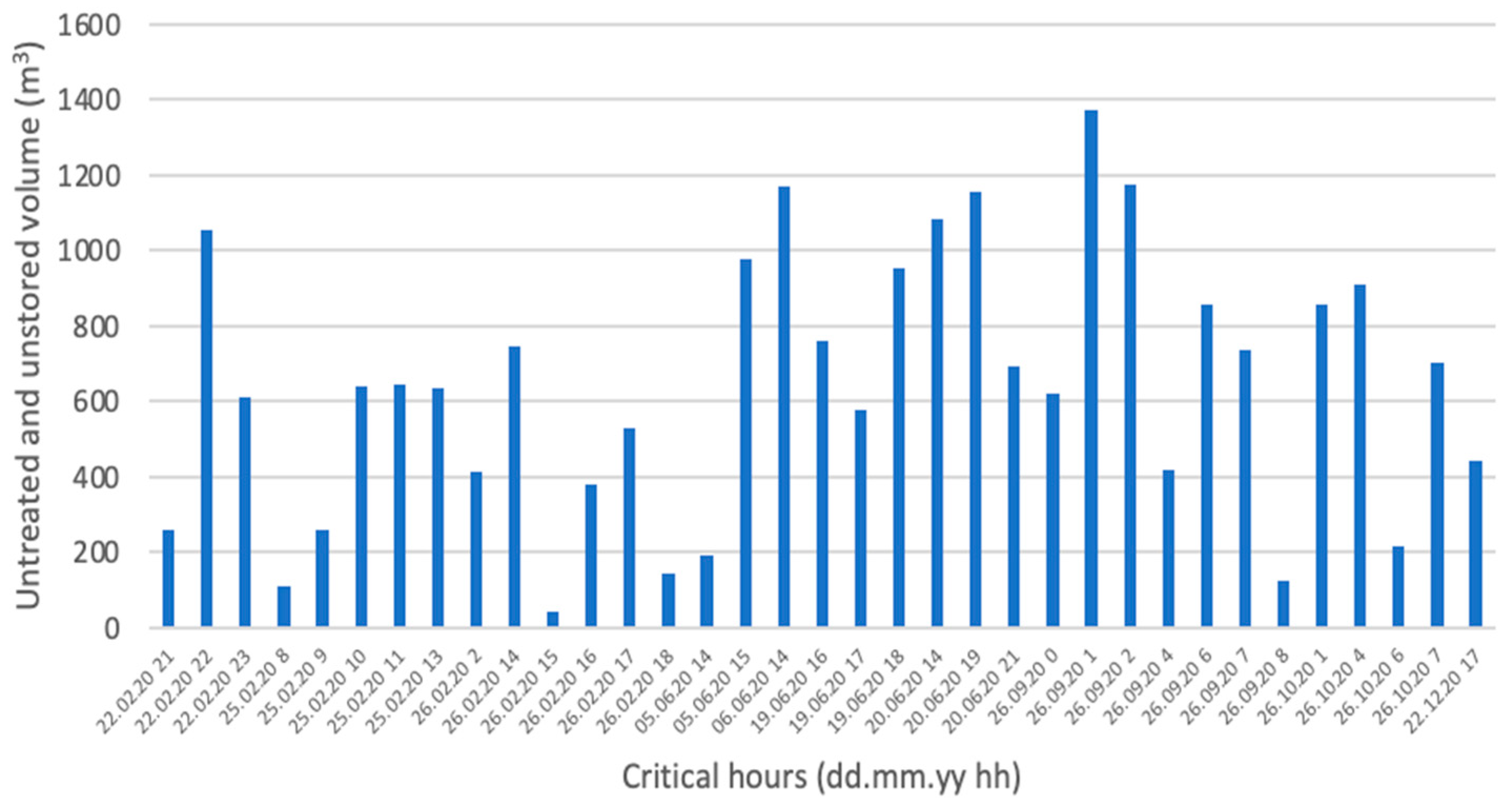

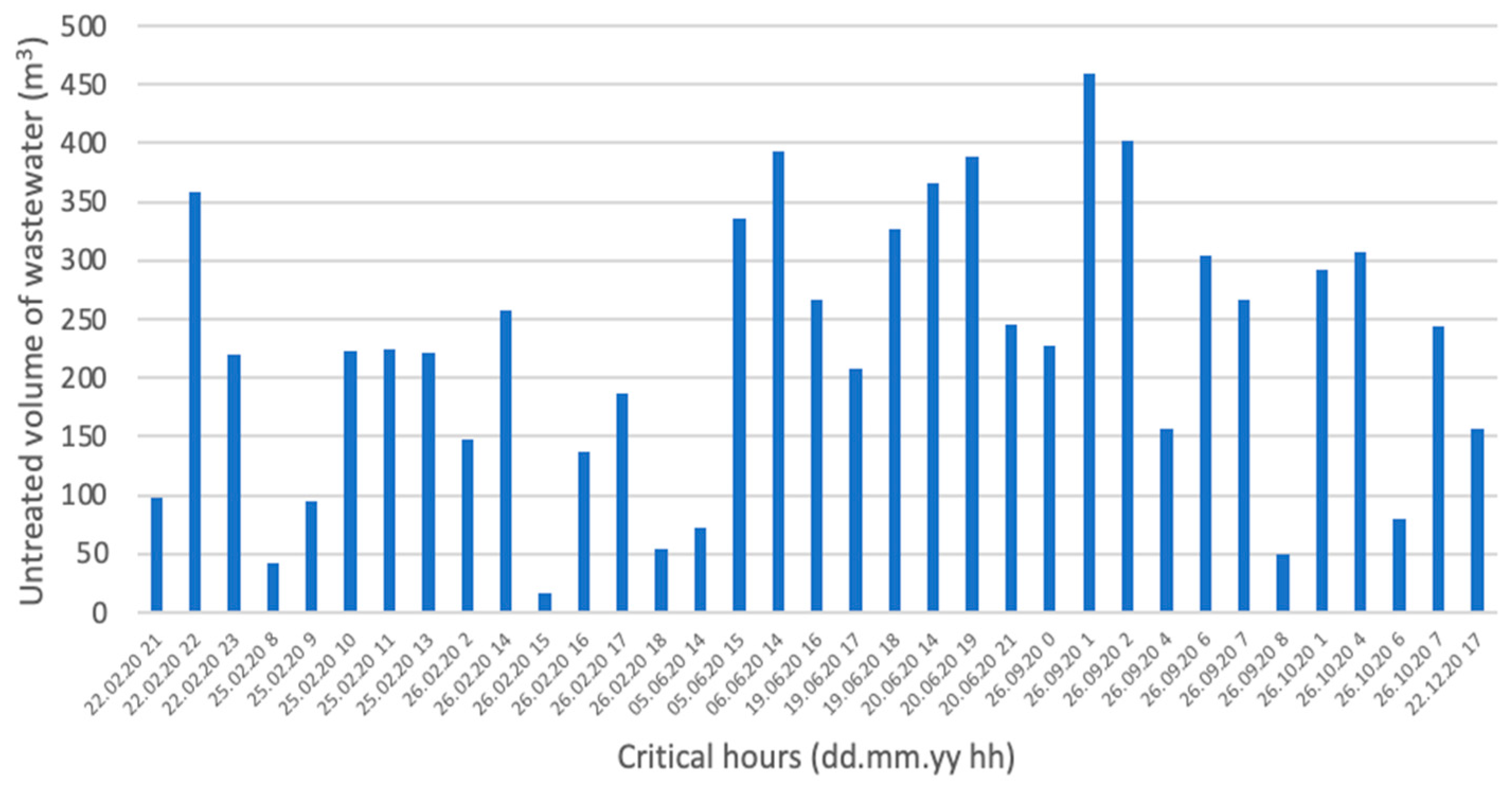

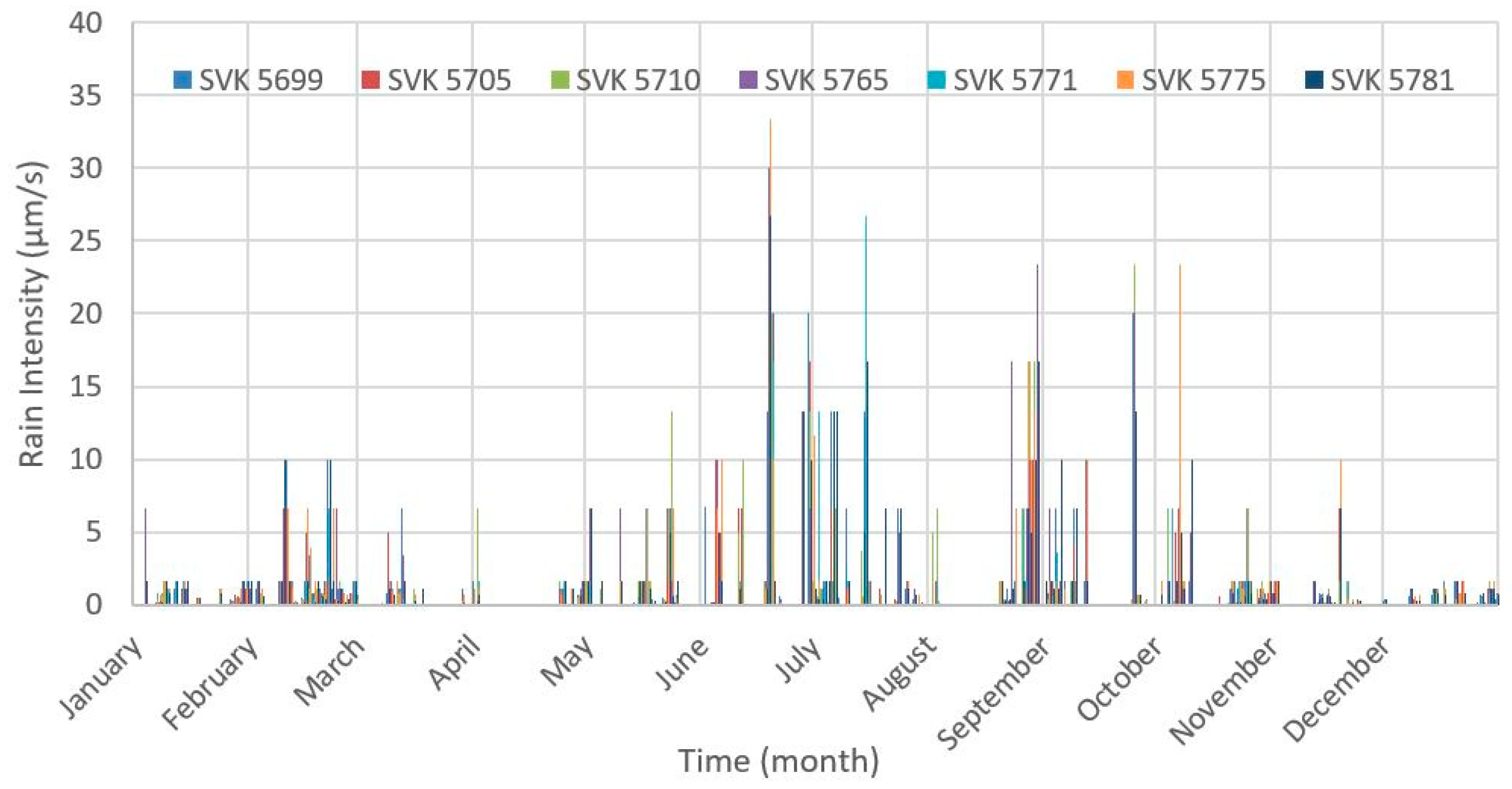

3.3.1. Consequences Evaluation for the Case Study

3.3.2. Probability Evaluation for the Case Study

- -

- fL (lowest attack frequency) = 0.1/year.

- -

- fH (highest attack frequency) = 2/year.

- -

- pL (lowest attack success probability) = 1%.

- -

- pH (highest attack success probability) = 100%.

3.4. Risk Evaluation

Evaluation of Risk for the Case Study

3.5. Risk Treatment

Mitigation Strategies for the Case Study

- Implementation of IT security systems.

- Implementation of the training procedure of the employees.

- Increase in the volume of the equalization tank.

4. Conclusions

- -

- Defining the context.

- -

- Risk identification (RIDB).

- -

- Risk analysis (Stress-testing procedure and Infrarisk-CP).

- -

- Risk evaluation.

- -

- Risk treatment (RRMD).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (1)

- How attractive it is to make an attempt to attack the water system, in terms of the following:

- -

- Recognisability?Answer: S1 = 2 (low). Due to the fact that there is no recognisability in affecting the wastewater treatment plants, power plants and distribution system are at a much higher risk.

- -

- Symbolism?Answer: S2 = 1 (very low). This will likely not affect the citizens, but “only” the environment, and drinking water and distribution systems are at a much higher risk than the wastewater treatment plants.

- -

- Potential for economic profit (e.g., ransom)?Answer: S3 = 3 (medium). Organized crime does not specifically target wastewater treatment plants, but there is a medium risk.

- -

- Potential for political profit?Answer: S4 = 1 (very low). Other utility sectors are at a much higher risk, such as electricity/power and drinking water utilities.

- (2)

- Level of Organizational issues, specifically regarding the following:

- -

- Measures implemented towards insiders?Answer: S5 = 4 (low). Low employee education regarding the implemented IT security can cause issues. Although user accounts for system access are in place, but no internal system to catch unsuccessful login/or hacking attempts is implemented.

- -

- Quality of internal surveillance and intelligence systems?Answer: S6 = 4 (low). No central system is implemented.

- -

- Systematic preparedness exercises, investigation, and learning?Answer: S7 = 5 (very low). An exercise on the IT systems and infrastructure is never completed.

- -

- Security focus in agreements with vendors and contractors?Answer: S8 = 4 (low). Vendors and contractors are required to sign a confidentiality agreement regarding GDPR and information obtained during work/interaction with BIOFOS.

- (3)

- Influencing conditions when an attacker will make an attack attempt on a specific component:

- -

- How vulnerable the component seems from the attacker’s point of view?Answer: S9 = 2 (low). Technical systems are behind the company firewall and a technical firewall that covers all the technical IT-systems. No administrative IT system user has direct access to the technical systems. A different technical username is required.

- -

- Visible protective measures by the utility manager for a specific component.Answer: S10 = 2 (high). The physical access to buildings and components is restricted. Alarm systems are installed in the buildings.

- -

- How critical the component seems from the attacker’s point of view?Answer: S11 = 2 (low). Normal attackers do not have specific knowledge regarding the operations, equipment, and control used at the wastewater treatment plant.

- -

- Accessibility of a particular component.Answer: S12 = 2 (low). All technical computer terminals are locked when not in use. Components (motors and gates) at the treatment plant cannot be operated locally when in the automatic control mode.

- -

- Attacker’s capability vs. required capability to make an attempt.Answer: S13 = 3 (medium). An attacker needs some skills to make an attempt, but it is possible.

- -

- Attacker’s available resources vs. required resources.Answer: S14 = 3 (medium). An attacker needs good resources to make an attempt, but it is possible.

- (4)

- Evidence with respect to possible attacks:

- -

- How is the actual cyber security situation evaluated by the security authorities (police, intelligence, etc.)?Answer: S15 = 3 (medium). Wastewater treatment plants are not the first in line for an attack, and a higher risk is evident at power plants and power distribution and drinking water production and distribution plants.

- -

- Evidence from the internal surveillance of a specific attack (computerized monitoring tools).This quantity is measured in terms of the number of attack attempts per time unit, typically per year.Answer: S16 is not available. Main users cannot be currently detected, and normal users would use workstations that are recognized; however, currently, there are no evidence regarding this inference.

- (5)

- Likelihood of succeeding in an attempt:

- -

- Attacker’s capability vs. required capability to succeed in an attemptAnswer: S17 = 4 (high). The attacker is an internal attacker, but normally, an attacker must overcome several firewalls and login to specific systems to succeed.

- -

- Attacker’s available resources vs. required resources to succeed in an attemptAnswer: S18 = 4 (high). The attacker is an internal attacker, but normally, only highly trained attackers can access and penetrate the implemented security measures to gain access to technical systems.

- -

- Explicit protective measuresAnswer: S19 = 2 (high). Even if the attacker is an internal attacker, he uses a VPN access; thus, an encryption is used. Moreover, only VPN access from Danish IP addresses is allowed, a two-step user verification for VPN access is adopted, and an administrative IT user must login to VPN. To access the technical systems, a technical user is allowed to access the server only via a VMware remote desktop, and no direct server access is provided. Finally, there are regular software updates for the firewall, antivirus tools, clients, and servers for both administrative and technical systems.

References

- Chen, H. Applications of cyber-physical system: A literature review. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2017, 2, 1750012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Moraitis, G.; Bouziotas, D.; Lykou, A.; Karavokiros, G.; Makropoulos, C. Cyber-physical stress-testing platform for water distribution networks. J. Environ. Eng. 2020, 146, 04020061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, C.W. Managing the risks of cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Long Island Systems, Applications and Technology Conference (LISAT), Farmingdale, NY, USA, 3 May 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 31000:2018; Risk Management. Risk Assessment Techniques. International Standards Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Bour, G.; Bosco, C.; Ugarelli, R.; Jaatun, M.G. Water-Tight IoT–Just Add Security. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2023, 3, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, A.; Rasekh, A.; Galelli, S.; Aghashahi, M.; Taormina, R.; Ostfeld, A.; Banks, M.K. A review of cybersecurity incidents in the water sector. J. Environ. Eng. 2020, 146, 03120003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bour, G.; Selseth, I.; Jaatun, M.; Ugarelli, R. D4.2: Risk Identification Database & Risk Reduction Measures Database. November 2021. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/6497050 (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Ostfeld, A.; Salomons, E.; Smeets, P.; Makropoulos, C.; Bonet, E.; Meseguer, J.; Mälzer, H.-J.; Vollmer, F.; Ugarelli, R. D3.2 Risk Identification Database. Supporting Document for RIDB. 2018. Available online: https://stop-it-project.eu/download/ridb-supporting-document-d3-2/ (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Mälzer, H.-J.; Vollmer, F.; Corchero, A. Risk Reduction Measures Database (RRMD). D4.3—Supporting Document. 2019. Available online: https://stop-it-project.eu/download/rrmd-supporting-document-d4-3/ (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Raspati, G.S.; Bruaset, S.; Bosco, C.; Mushom, L.; Johannessen, B.; Ugarelli, R. A Risk-Based Approach in Rehabilitation of Water Distribution Networks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannina, G.; Viviani, G. Separate and combined sewer systems: A long-term modelling approach. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freni, G.; Mannina, G.; Viviani, G. Identifiability analysis for receiving water body quality modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 2009, 24, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisano, A.P.; Creaco, E.; Modica, C. Improving combined sewer overflow and treatment plant performance by real-time control operation. In Enhancing Urban Environment by Environmental Upgrading and Restoration; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Makropolous, C.; Moraitis, G.; Nikolopoulos, D.; Karavokiros, G.; Lykou, A.; Tsoukalas, I.; Morley, M.; Castro Gama, M.; Okstad, E.; Vatn, J. Deliverable 4.2: Risk Analysis and Evaluation Toolkit. 2019. Available online: https://stop-it-project.eu/download/risk-analysis-and-evaluation-toolkit/ (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Giannopoulos, G.; Filippini, R.; Schimmer, M. Risk assessment methodologies for Critical Infrastructure Protection. Part I: A state of the art. JRC Tech. Notes 2012, 1, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renuka, S.M.; Umarani, C.; Kamal, S. A Review on Critical Risk Factors in the Life Cycle of Construction Projects. J. Civ. Eng. Res. 2014, 4, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, M.J.E.; Yamada, A.P.L.; Domingos, E.G.N.; Leite, L.R.; Pereira, C.R. Exploring organizational resilience through key performance indicators. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2021, 38, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Moraitis, G.; Bouziotas, D.; Lykou, A.; Karavokiros, G.; Makropoulos, C. RISKNOUGHT: A cyber-physical stress-testing platform for water distribution networks. In Proceedings of the 11th World Congress on Water Resources and Environment (EWRA 2019) “Managing Water Resources for a Sustainable Future”, Madrid, Spain, 2–6 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.H.; Han, C. Semi-quantitative cybersecurity risk assessment by blockade and defense level analysis. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 155, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, C.; Raspati, G.S.; Tefera, K.; Rishovd, H.; Ugarelli, R. Protection of Water Distribution Networks against Cyber and Physical Threats: The STOP-IT Approach Demonstrated in a Case Study. Water 2022, 14, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, M.; Virolainen, K. A comparative analysis of macro stress-testing methodologies with application to Finland. J. Financ. Stab. 2006, 2, 113–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, S.; Martinez-Jaramillo, S. Financial networks and stress testing: Challenges and new research avenues for systemic risk analysis and financial stability implications. J. Financ. Stab. 2018, 35, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Stojadinovic, B.; Babič, A.; Dolšek, M.; Iqbal, S.; Selva, J.; Giardini, D. Engineering risk-based methodology for stress testing of critical non-nuclear infrastructures (STREST Project). In Proceedings of the 16th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Santiago, Chile, 9–13 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, S.; Stojadinović, B.; Babič, A.; Dolšek, M.; Iqbal, S.; Selva, J.; Broccardo, M.; Mignan, A.; Giardini, D. Risk-based multilevel methodology to stress test critical infrastructure systems. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2020, 26, 04019035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyroudis, S.A.; Fotopoulou, S.; Karafagka, S.; Pitilakis, K.; Selva, J.; Salzano, E.; Basco, A.; Crowley, H.; Rodrigues, D.; Matos, J.P.; et al. A risk-based multi-level stress test methodology: Application to six critical non-nuclear infrastructures in Europe. Nat. Hazards 2020, 100, 595–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Trump, B.D.; Trump, J.; Pescaroli, G.; Hynes, W.; Mavrodieva, A.; Panda, A. Resilience stress testing for critical infrastructure. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 82, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojjati, S.N.; Noudehi, N.R. The use of Monte Carlo simulation in quantitative risk assessment of IT projects. Int. J. Adv. Netw. Appl. 2015, 7, 2616. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, N.; Fayek, A.R.; Pedrycz, W. Fuzzy Monte Carlo Simulation and Risk Assessment in Construction. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2010, 25, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, U.; Yildiz, Ö. Economic risk analysis of decentralized renewable energy infrastructures—A Monte Carlo Simulation approach. Renew. Energy 2015, 77, 227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, J. Modeling Risk: Applying Monte Carlo Simulation, Real Options Analysis, Forecasting, and Optimization Techniques; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 347. [Google Scholar]

- Koc, K.; Işık, Z. Assessment of Urban Flood Risk Factors Using Monte Carlo Analytical Hierarchy Process. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2021, 22, 04021048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabawy, M.; Khodeir, L.M. A systematic review of quantitative risk analysis in construction of mega projects. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2020, 11, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroese, D.P.; Brereton, T.; Taimre, T.; Botev, Z.I. Why the Monte Carlo method is so important today. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2014, 6, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STOP-IT. InfraRisk CP—User’s Guide. 2020. Available online: https://stop-it-project.eu/download/infrarisk-cp-user-guide/ (accessed on 17 August 2023).

| Probability (p) | F | M | H | H | VH | VH |

| P | L | M | M | H | VH | |

| O | L | L | M | M | H | |

| R | VL | L | L | M | H | |

| VU | VL | VL | L | L | M | |

| VL | L | M | H | VH | ||

| Consequence (c) | ||||||

| Parameter | COD | Nitrogen | Phosphorus | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inlet concentrations | 680 | 53 | 7.1 | mg/L |

| Plant loading per day | 47,000 | 3700 | 500 | kg/d |

| Effluent required concentrations | 75 | 8.0 | 1.5 | mg/L |

| Effluent concentrations | 32 | 6.1 | 0.6 | mg/L |

| Effluent discharge per day | 2169 | 416 | 42 | kg/d |

| Percentage of pollutants removal | 95 | 89 | 92 | % |

| Low Risk | Medium Risk | High Risk |

|---|---|---|

| KPI ≤ 120 | 120 < KPI ≤ 1200 | KPI > 1200 |

| Low Risk | Medium Risk | High Risk |

|---|---|---|

| KPI ≤ 120 No Low Risk: 233 > 120 | 120 < KPI ≤ 1200 Medium Risk: 120 < 233 ≤ 1200 | KPI > 1200 No High Risk: 233 < 1200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bosco, C.; Thirsing, C.; Jaatun, M.G.; Ugarelli, R. A Cyber-Physical All-Hazard Risk Management Approach: The Case of the Wastewater Treatment Plant of Copenhagen. Water 2023, 15, 3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15223964

Bosco C, Thirsing C, Jaatun MG, Ugarelli R. A Cyber-Physical All-Hazard Risk Management Approach: The Case of the Wastewater Treatment Plant of Copenhagen. Water. 2023; 15(22):3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15223964

Chicago/Turabian StyleBosco, Camillo, Carsten Thirsing, Martin Gilje Jaatun, and Rita Ugarelli. 2023. "A Cyber-Physical All-Hazard Risk Management Approach: The Case of the Wastewater Treatment Plant of Copenhagen" Water 15, no. 22: 3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15223964

APA StyleBosco, C., Thirsing, C., Jaatun, M. G., & Ugarelli, R. (2023). A Cyber-Physical All-Hazard Risk Management Approach: The Case of the Wastewater Treatment Plant of Copenhagen. Water, 15(22), 3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15223964